Text

The High Cost of Charity

In a recent column, gossipist James Revson of Newsday, who is gay, attacked writers in OutWeek and the Village Voice for criticizing Mrs. William F. Buckley, Jr. Mrs. Buckley is the wife of one of the nation's chief homophobes, a man who has publicly called for the tattooing and incarceration of PWAs and who rants and rails in the press about AIDS being a "self-inflicted" disease. Mrs. Buckley refuses to disagree with her husband's position, responding with a regal "no comment" to questions about tattooing people with AIDS. In a breathtaking display of hypocrisy, she then lends her efforts and her famous Republican name to AIDS charity events.

Revson argued that this is all right, that AIDS charities need the money, and that in such a situation a wife is not responsible for distancing herself from her husband's deadly positions. We disagree.

The supreme enemies of gays and lesbians are those rightwing forces who enforce homophobia in our culture. Always a depressing reality, they became a deadly nightmare when AIDS struck, and there is no price tag on the misery they have caused.

It may be hard to remember, but there was a time in the recent past when the majority of us were not infected, when timely education could have prevented most of the AIDS nightmare. Instead, the Buckleys of the world avidly enforced a media blackout of AIDS. Then, after that had succeeded, they began floating proposals like concentration camps and tattooing.

These people are venal. They are to our community as the Nazis were to the Jews. The idea that we're so desperate for money that we should accept it from anyone, even our executioners, is ghoulish indeed.

Revson's comment that Mrs. Buckley somehow can't publicly disagree with her husband is nonsense. If she really wished to do something about AIDS she most certainly would disagree with him, often and loudly. In so doing she could take a lesson from her friend Barbara Bush, who publicly disagrees with her husband the president on gun control. Wives are autonomous and have a right to disagree with their spouses, even Republican wives, and they often do. The fact that Mrs. Buckley imperiously refuses indicates that she probably agrees with her husband's ugly views. Such complicity in extreme homophobia disqualifies her from using AIDS charity work to boost her social standing.

It's extremely sad when AIDS or gay organizations feel they must accept money from our avowed enemies, be they Coors Beer, the Roman Catholic Church or Pat Buckley. We should not allow homophobes who are killing us to confuse the issue by buying us off. We have enough genuine friends that we don't need to cringe for blood money.

— Editorial, OutWeek Magazine No. 21, November 12, 1989, p. 4.

#outweek#issue 21#lgbt history#outspoken#editorial#hiv aids#william f. buckley#pat buckley#james revson#homophobia

6 notes

·

View notes

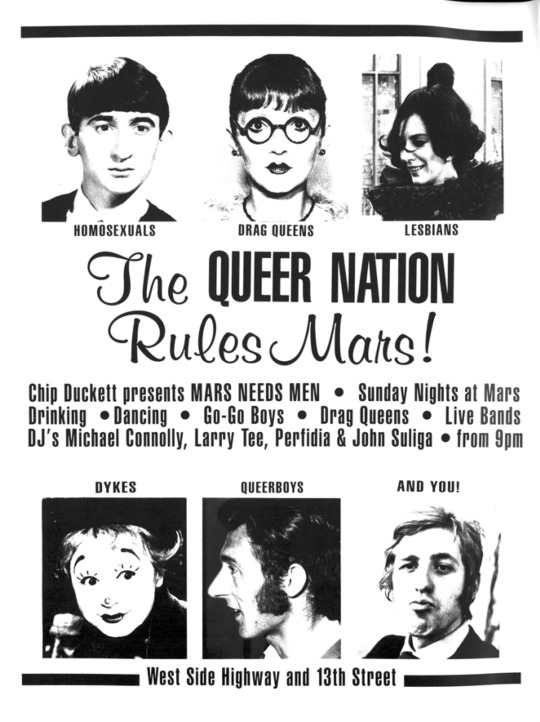

Photo

Full-page ad for Chip Duckett’s MARS NEEDS MEN party, OutWeek Magazine No. 21, November 12, 1989, p. 2.

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

MICHAEL MUSTO, columnist, critic, author, movie star and visually stunning fixture of New York's "in," has just released his first novel. Manhattan On The Rocks is a 298 page romp through the dark side of the scene, a testicular triumph of gossip and yeast Infection. Musto, whose column La Dolce Musto appears weekly in the Village Voice, has become the late night survival guide for the wanna be's, the gonna be's and the I am's of New York's other side of midnight. He spends most of his time "stewing in bitterness" and says he "regrets everything," which we know is just another dirty little lie. He told us he's become an avid fan of Martika and of Delta Burke, "who's fighting a career battle with food. I feel for her. I wish I were a bon-bon and she could devour me." With the faint sound of "Summer Breeze" blaring in the background and with Shake and Bake in one hand and drink tickets in the other, one can visualize Musto glamourously propped up against the "latest," crooning a favorite line from role-model Martika: "...won't you come out and play with me..."

We have no choice, dear.

— Erich Conrad, "Hot Shot," OutWeek Magazine No. 20, November 5, 1989, p. 88. Photo by Lizzerd Souffle.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

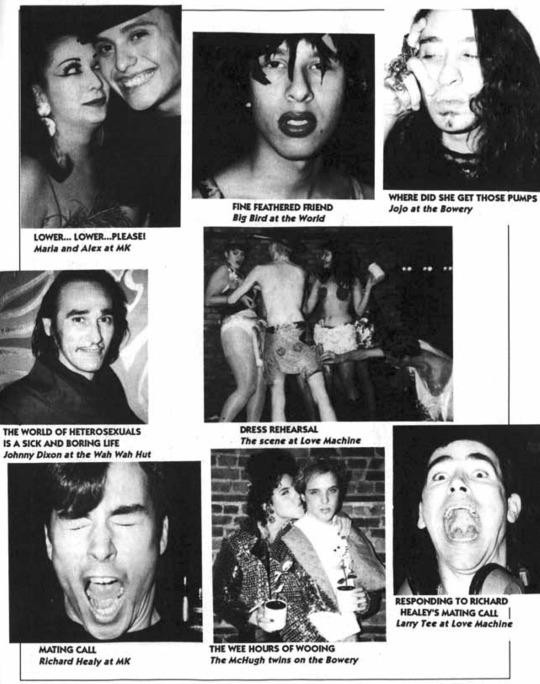

Social Terrorism by Erich Conrad, OutWeek Magazine No. 20, November 5, 1989, pp. 50–51.

#outweek#issue 20#lgbt history#nightlife#social terrorism#erich conrad#photo#love machine#sue nicely#kevin mchugh#tom eubanks#haoul montaug#michael schmidt#myra field#mk#big bird#the world#the bowery#johnny dixon#wah wah hut#richard healy#larry tee

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cover of OutWeek Magazine No. 21, November 12, 1989, 30 years ago today.

On the cover: Monika Treut photographed by Mark Golebiowski

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Once performed in a garage on Avenue D on a budget of $32.50, Charles Busch's Vampire Lesbians of Sodom celebrates its 1,786th performance on November 7th [1989] (at the Provincetown Playhouse, 133 Macdougal St.) becoming Off-Broadway's longest running play (non-musical). And to mark the occasion, in addition to a party at MK that night, the price of all seats for the 1,786th performance will drop from $24 to — what else? — $17.86.

Here, Vampire star David Drake holds up the the trademark vampire lips and fangs along with Busch himself who has now gone east to the Orpheum Theater where he stars in his latest romp The Lady In Question.

— Michelangelo Signorile, "Lookout," OutWeek Magazine No. 20, November 5, 1989, p. 46.

#outweek#issue 20#lgbt history#vampire lesbians of sodom#theater#charles busch#mk#david drake#michelangelo signorile#look out#photo#culture

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

What happens when a gay and lesbian community spends years asking for regular television coverage of its issues instead of occasional "special documentaries" which tend to anthropologize or mock the subject matter? If you are asking this question in the United States, you might just have to start protesting, elect a mayor, create a coalition (call it NYCCRM), raise money for an alternative network, or program your queer media on public access and other cable channels. If you are asking this question in Britain, look no further, just get those beers or sodas out of the fridge, settle back in your comfy living room chair and tune into Channel Four on Tuesday nights at 11 pm. Then you will see Out On Tuesday, Britain's first regular lesbian and gay television series.

The series is co-produced by Clare Beaven and Susan Ardill[, who] named their production company "Abseil" in recognition of the women who had lowered themselves with ropes (the word abseil is a verb used in England to mean "lowering oneself on a rope") into the House of Lords to protest Clause 28. (Clause 28 bans any federal funding of educational materials that "promote homosexuality." [...]) The image of a woman descending on a rope accompanies the closing credits in every show of the series. [...]

Although it is programmed late at night, the series was immediately attacked by right wing bigots who called on the government to revise the Obscene Publications Act. British TV operates independently of that Act, but the whole system of regulation within commercial parameters could be overthrown by the government in the next few years. Clause 28, which governs local government and education authorities against presenting gay men and lesbians in anything but the most brutally degrading light, could ultimately have an effect on TV and broadcasting.

While it is still possible, Clause 28 is a featured topic on the very first show of Out On Tuesday. The producers decided to see if one could actually "promote homosexuality," and thus approached the world-renowned, if detestable, Saatchi and Saatchi advertising agency: Since agencies love to display their wares and benefit from mock campaigns as teaching exercises, S & S agreed to script a number of "homo-promo" newspapers ads as well as one for TV. Abseil's directors kept their distance during the "creative process." What emerged was a hilarious, but somewhat ignorant and negative, commercial with, as Merck says, "the naffest looking actresses in the world." Beaven thinks she would have modelled the show around how and why, "they came up with this garbage when they come up with great homoerotic ads for perfume, and so on."

— Catherine Saalfield, "Queervision: In England, Finding Gay and Lesbian. TV is as Easy as Pushing a Button on Your Remote Control," OutWeek Magazine No. 20, November 5, 1989, p. 42.

#outweek#issue 20#lgbt history#feature#uk#tv#gay tv#clause 28#homophobia#out on tuesday#clare beaven#susan ardill#catherine saalfield#photo#lesbian

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Extending Leases and Lives

On Sunday, October 15th [1989], AIDS activist and long-term survivor John Bohne died. His death was sudden, and came as a shock to those who had seen him at a meeting of ACT UP's Treatment and Data Committee that Wednesday, and to those who had seen him Friday, when we went to an appointment at Gay Men's Health Crisis.

Something else happened to him that Friday: he received a "Notice to Quit," the first step in an eviction action, on his apartment. A good friend of his, Mike Frisch, who took John to the hospital on Saturday night, says John was very troubled by the threat of eviction and thinks that it just might have been what broke John's spirit.

John had lived in the Manhattan Valley apartment for more than three years with his lover, Bill McCann, until Bill died in May, 1988. The lease to the apartment was in Bill's name.

How the hell is someone who is fighting a virus inside his body in order to stay alive, and fighting the FDA bureaucracy for access to drugs in order to fight the virus, supposed to muster the energy to fight his landlord in housing court?

In July we all celebrated the Braschi decision, in which the New York State Court of Appeals said gay couples could legally be considered families. Specifically, the case involved a couple who had been living together in an apartment for ten years. The man in whose name the lease was held died of AIDS, and the landlord attempted to evict the survivor. The court decision granted him succession rights to the lease, and stated that "the term family...should not be rigidly restricted to those people who have formalized their relationship by obtaining, for instance, a marriage certificate or an adoption order."

Then why was John Bohne's landlord able to refuse to renew his lease and try to evict him?

One reason is that the Braschi decision has yet to be translated into specific enforceable regulations. Nearly four months after the decision, it has not been implemented. What's happening?

It depends on who you ask. Tom Viola, a spokesperson for the state's Division of Housing and Community Renewal (DHCR), says "We are seeking a legislative solution. If that is thwarted, then we'll go administratively." The problem with that is that the Republican-controlled State Senate has for years refused to extend lease protections to non-married partners, and has refused any protection for lesbians and gays, even in the context of bias-related violence. So it really is a foregone conclusion that legislative efforts to bring the law into accor- dance with the Braschi decision will be thwarted.

Our advocates seem somewhat more hopeful. Lesbian and gay and tenant groups have been lobbying DHCR to issue administrative regulations. According to attorney William Rubinstein of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), who won the Braschi case, that victory "gave us great impetus and power at the bargaining table.II Another attorney involved in the talks, Evan Wolfson of the lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund, reports that "They [DHCR] have agreed in principle to protect the family in a comprehensive and realistic way, including lesbian and gay families." But, says Rubinstein, "We would have liked to have seen something happen by now."

Time is of the essence. It is AIDS which made the whole issue of succession rights so pressingly important to our community, and AIDS which makes so many of the very people who stand to be protected by these regulations so vulnerable. The last thing anyone living with AIDS needs is a legal battle to keep his or her home.

As the people fighting for housing for homeless PWAs have been stressing, a home is a precondition for survival: what use is medical care without a stable and nurturing living environment?

This week it was John Bohne, and presumably others in similar straits, who received eviction threats. John Bohne was dead less than 48 hours later. Who will it be next week?

Will it take four more months for the principle affirmed by Braschi to be given force in state regulations?

— Sandor Katz, OutWeek Magazine No. 20, November 5, 1989, p. 34.

#outweek#issue 20#lgbt history#hiv aids#act up#john bohne#family#housing#braschi v. stahl associates#lambda legal#evan wolfson#william rubenstein#aclu#dhcr#bill mccann#homophobia#sandor katz#commentary

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Stonewall for a New Generation

When I arrived at the stark gray Federal Building for ACT UP San Francisco's contribution to the national day of AIDS protest on October 6 [1989], I anticipated nothing more than a predictable late afternoon rally and a routine march across town. Instead, by the end of the evening, I had joined hundreds of demonstrators and bystanders in defying a two-hour long police riot and military-style occupation in the largely gay Castro St. neighborhood.

Mixed with calls of "Cops out of the Castro" and "This is our street," chants of protest made the historical precedents clear that Friday night. "Stonewall was a riot," we shouted, drawing courage from the example of the defiant street queens in Sheridan Square in 1969. "Dan White was a cop," we raged, recalling a judicial slap on the wrist for a homophobic assassin and the resulting White Night Riots in San Francisco in 1979.

The events of October 6 [1989] started out mildly enough. After speeches, street theater and the burning of miniature flags, demonstrators wrapped the granite columns of the Federal Building in yards of red plastic tape to symbolize governmental stalling on the AIDS crisis. Federal marshalls protecting the structure made a half-hearted effort to remove the tape, but I saw no attempt to restrain the protestors.

Around 5 p.m. we moved onto the sidewalk for a march to the Castro via City Hall and the U.S. Mint. Within minutes, the San Francisco Police Department (SFPD) had mounted a show of force unprecedented for an ACT UP demonstration: Officers in vehicles and on foot lined up to prevent us from claiming a lane in the street; when traffic lights turned red, motorcycle cops charged the crowd to force a halt until the light changed.

Less than two blocks from the Federal Building, the first arrest took place: Moving to the curb, I watched two officers strong-arm an already shackled marcher into a paddy wagon. (I later learned that this was Bill Haskell, ACT UP's police liaison, who had approached the officers on the street to identify himself and ask about the crowd control tactics we were witnessing; they had thrown him face down on the pavement and handcuffed him).

The harassment continued along the 30-block route, yet the crowd remained orderly. To. SFPD announcements of "Obey the traffic laws," protestors responded with chants of "First Amendment under attack! What do we do? ACT UP! Fight Back!" Half way to Castro St., organizers briefly halted the march; an ACT UP representative restated the AIDS related goals of the event and urged us to focus our anger and press on despite the actions of the police.

Around 7 pm, as we approached the end of the march, word passed through the crowd that we would take over the intersection of Market and Castro Streets. A traditional finale for ACT UP San Francisco marches, this act of non-violent civil disobedience usually includes short speeches and chants, after which the crowd disperses without incident. The standard SFPO response: a few officers on foot diverting traffIC to protect public safety at minimum effort and expense.

A quarter-block back from the head of the march, I could see the flashing lights of massed SFPD vehicles on Market St. Arriving at Castro St., I found that several dozen officers on foot and In vehicles had turned the marchers away from Market. Instead, we were surging left onto the Castro strip, filling the street for several yards and preventing the police from moving into the area.

As one group of approximately 50 protestors sat down and linked arms on Castro near Market, 20 others took advantage of the blockade to stage a die-in on the open lane in front of chi-chi stores and eateries. Adding stencilled slogans and spray paint in neon colors over the chalked outlines of bodies, the participants created a "permanent AIDS quilt" on the street — less than two blocks from the headquarters of the Names Project.

While approximately 500 people chanted and jeered from both sides of Castro St., the police moved in to arrest the protestors sitting on the asphalt. Finished with this activity, the officers turned their attention on the crowd, which was growing In numbers as Friday night passersby stopped to observe — and protest — the massive police presence in the heart of the gay community.

After a loudhailer order to clear the street, motorcycle and riot police advanced down the center of Castro St. Lines of tactical unit officers pushed forward with batons held across their chests, attempting to force people onto the sidewalks. Standing at the front of the crowd on the west side of Castro, I could see no escape route; people behind me packed the sidewalk to the shopfronts or were penned in by further police lines at the rear.

The police soon charged in earnest. I saw one officer advance with his baton in a jabbing position, a technique that the San Francisco Police Commission banned after an officer using it nearly killed Farmworkers Union co-founder Delores Heurta last year. Others pushed with the sides of their batons, knocking the front of the crowd off balance. I fell against the person to my left, scraping my ear, then regained my footing.

After a partial withdrawal and a second effort to clear the area, the police announced that the entire block of Castro from Market to 18th St., Including the sidewalks, had been declared an illegal assembly area. The crowd held its ground, milling into the street and repeatedly chanting "Cops go home" and "Racist, sexist, anti-gay, SFPD go away." A group of officers reacted driving their motorcycles through the center of the crowd.

In the confusion, I lost sight of the friends I had been standing with and made my way to the opposite side of Castro St. From that vantage, I watched an officer break ranks, approach a man standing peacefully in the street and beat him over the shoulder. Shortly thereafter, I saw a second officer pin a bystander against a news box, then club him to the pavement. Other cops joined in, one of them so eager to land a blow that he carelessly clubbed a fellow officer.

Minutes later, I heard someone calling out my name and spotted Alex Chee, one of the friends I had marched with, leaning from an ambulance moving slowly through the police lines. "I'm going to the hospital with Mike," he shouted. With a sinking feeling, I pushed to the back window: inside, I could see another friend, Michael Barnette — a 19-year-old who was attending his first ACT UP demonstration — strapped motionless on a stretcher.

(Michael received several stitches to close a gash across his eyebrow. According to witnesses, an officer identified as a captain in the SFPD Tactical Unit and an event commander for the October 6 protest clubbed Michael on the head as he stood on the sidewalk on the west side of Castro St. From the opposite corner, I had heard protestors chanting the officer's helmet number — 1942 — but had not seen the beating).

Around 9 p.m., the police reformed into disciplined lines and commenced sweeping most of the crowd down Castro St. Left behind the lines, I move onto 17th St., where riot cops routed me from the doorway of an all night diner. The entire neighborhood, they informed me, was now an illegal assembly; everyone in the area was subject to arrest. Clutching a notebook in which I had scrawled the helmet numbers of offending officers, I finally retreated homeward.

(According to witnesses, the police left the Castro around 10 p.m., after it became clear that the crowds would not abandon their neighborhood to a military occupation by the Tactical Unit. Once, the police had withdrawn, protesters ringed the intersection of Castro and 18th, cheered and dispersed peacefully).

Even before I reached my flat, the symbolism of this night of defiance was becoming dear. Like Stonewall and White Night, we had been put to the test and had stood our ground. In the face of violence, we had responded with tenacity, ingenuity and non-violence. A new generation of lesbian, gay and bisexual peopl'e — the activists in their teens and twenties who comprise much of ACT UP's membership — had experienced its own historic turning point.

— Gerard Koskvich, OutWeek Magazine No. 20, November 5, 1989, p. 32.

#outweek#issue 20#lgbt history#hiv aids#act up#san francisco#san francisco journal#castro#sfpd#police#bill haskell#news#gerard koskovich#violence#photo#marc geller#protest

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Back alleys = dumpsters

CHICAGO [November 5, 1989] — Responding to a national day of actions called for by ACT NOW, a nationwide AIDS activist network, ACT UP/Chicago and the Emergency Clinic Defense Coalition (ECDC) sponsored a demonstration held Friday, October 6 [1989], 1989 in downtown Chicago to support gay and lesbian rights and reproductive freedom.

Using street theater as the centerpiece of the action, the demonstrators reportedly chanted "back alleys are for dumpsters, closets are for clothes!" They then paraded a "freedom bed" containing lesbian, gay and straight couples making love as they lampooned the reactions of Senator Jesse Helms, "ardent anti-choice, anti-gay" state legislator Penny Pullen, Pro-Life Action League head Joseph Scheidler, the Pope and the Supreme Court.

The purpose of the dramatic display was to decry the interference of right-wing legislators in the lives of all people, and to connect issues of reproduction, sexuality and AIDS, according to ACT UP/Chicago members. "There are legal parallels between AIDS and abortion rights, particularly with the Hardwick and Webster Supreme Court decisions which affect sexual and reproductive privacy," said Carol Jonas, a spokeswoman for both ACT UP and ECDC, in a telephone conversation with OutWeek. "And our other parallel demands include free and universal health care and an end to racism and sexism."

After the performance, participants marched downtown handing out condoms with messages attached such as "put this on the penis of your choice" and "a fashion accessory that goes great with nothing."

— Keith Miller, OutWeek Magazine No. 20, November 5, 1989, p. 28.

#outweek#issue 20#lgbt history#hiv aids#protest#women's health#act up#chicago#reproductive health#abortion#jesse helms#penny pullen#act now#keith miller#emergency clinic defense coalition#news#out takes#photo#steve dalber

1 note

·

View note

Text

Burroughs bashing

CHICAGO [November 5, 1989] — Ten members of ACT UP/Chicago attacked the Burroughs Wellcome Company's large exhibit at the American Public Health Association's (APHA) 117th annual meeting Oct. 24 [1989] in Chicago, tossing vials of "blood" on the panels, brochures and TV monitors and plastering the display with stickers reading "AIDS PROFITEER."

Wellcome has exclusive U.S. rights to produce the drug AZT, which is the only approved substance for fighting HIV[.] Despite a recent 20 percent price reduction, AZT still costs each recipient about $6,500 per year, making it the most expensive pharmaceutical in history.

In a hand-out distributed during the rowdy "zap," ACT UP called upon the APHA "to pass a resolution condemning AIDS profiteering by pharmaceutical companies, in particular Burroughs Wellcome...and Lyphomed." Chicago-based Lyphomed produces the anti-pneumonia AIDS drug pentamidine and, armed with a government monopoly, has raised its price 400 percent since the mid-80s. LyphoMed did not have a booth at the APHA gathering.

Convention-goers who observed the ten-minute zap were overwhelmingly supportive of ACT UP's actions, cheering the group on and commenting to each other that the protesters' allegations were true.

A lone exception was E.J. Daigle, production manager for Helena Laboratories in Beaumont, Texas, who, mistaking this reporter for one of the protesters said: "Are you a part of this? This is disgusting. You know what AIDS stands for? AIDS-Infected Dick-Suckers."

Daigle's partner, Helena's Bruce Coryell, added that if activists "really want to take the profit away from Burroughs Wellcome, they should practice a lot of celibacy."

Bailus Walker, Jr., past president and spokesperson for the APHA, said his group was "not in agreement with the form of [ACT UP's] protest," but felt the zap was "consistent with APHA policy. Medical services, drugs, surgical procedures," Walker said, "should be available at a price that everyone can afford."

According to Walker, the APHA's 10,000 delegates would "seriously consider any resolution to condemn profiteering. That's what the APHA is all about," he said.

Burroughs Wellcome officials at the site had no comment on the zap. The 20 percent reduction in the price of AZT on Sept. 18 [1989] was widely believed to be a response to protests by ACT UP/New York at the New York Stock Exchange and at Wellcome corporate headquarters in Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, although company officials denied the connection.

— Rex Wockner, OutWeek Magazine No. 20, November 5, 1989, p. 27.

#outweek#issue 20#lgbt history#hiv aids#act up#chicago#news#rex wockner#out takes#protest#burroughs wellcome#drug pricing#azt#american public health association#homophobia

0 notes

Text

Quake Kills Chicana Lesbian

SANTA CRUZ [November 5, 1989] — Robin Ortiz, a 22-year-old Chicana lesbian, was killed when the store she worked in collapsed in the devastating earthquake October 17 [1989]. Shawn McCormick, 21, another store employee, was also killed.

For 40 desperate hours, over 25 friends kept a vigil outside the store, hoping that Ortiz was still alive. On Wednesday, several people were arrested by police for protesting what they said was a lackadaisical search effort. According to Anne Gfeller, a co-worker and close friend, the search was halted on two separate occasions for many hours with no adequate explanation.

Ortiz was active in the lesbian and gay community in this progressive college town on the coast about 100 miles south of San Francisco. She worked with the Santa Cruz AIDS Project, and managed the Santa Cruz Coffee Roasting Company, a community landmark on the downtown Pacific Garden Mall, most of which now lies in ruins.

New York City's Daily News first reported her death, offering a bold subhead reading "Lesbian Activist." But when describing the anguish of Ruth Rabinowitz, Ortiz' lover, it described her only as a woman who "had moved here with Ortiz from Los Angeles five years ago."

According to Gfeller, Rabinowitz struggled with authorities throughout the ordeal to gain recognition as Ortiz' next of kin, and was finally successful. Gfeller called this victory a fitting and hopeful symbol for the work "which goes beyond our own lives."

— Rachel Lurie, OutWeek Magazine No. 20, November 5, 1989, p. 21.

#outweek#issue 20#lgbt history#lesbian#california#loma prieta#robin ortiz#ruth rabinowitz#news#rachel lurie

0 notes

Text

Political (in)justice

Justice Department Annual Statistics for 1985 state that the average sentence for those convicted on charges of weapons and firearms possession was 43 months. Sentencing Guidelines, established November 1988, set 22-44 months as the recommended time in prison for weapons possession. The recommended sentence for making false statements to purchase weapons is two years. Defendants convicted of weapons possession that is not politically motivated almost always receive sentences within the range specified by the Guidelines. See below for sentences regarding the convictions of politically motivated defendants:

Don Black — Ku Klux Klan member. Arrested with boatload of illegal automatic weapons, on his way to set up a drug ring on a Caribbean island. Not held in preventive detention. Sentence: three years. Time served: 24 months.

Michael Donald Bray — Ku Klux Klan member. Convicted of bombing ten abortion clinics, three of which were occupied when explosions occurred. Not held in preventive detention. Sentence: ten years. Time served: 46 months.

Robert Louis White — Grand Dragon of Maryland Ku Klux Klan. Convicted of assaulting a Black man during racial brawl, and of conspiracy in bombing a synagogue. Pleaded guilty to owning arsenal including rifles, shotguns, handguns and live hand grenades. Not held in preventive detention. Sentence: 36 months. Time served: now in prison.

Oliver North — Former Security Council aide. Admitted having helped engineer the illegal drug and gun sales that killed thousands of Central Americans. Not held in preventive detention. Convicted on three counts of conspiracy in defrauding the government. Sentence: community service and suspended fine. Time served: none.

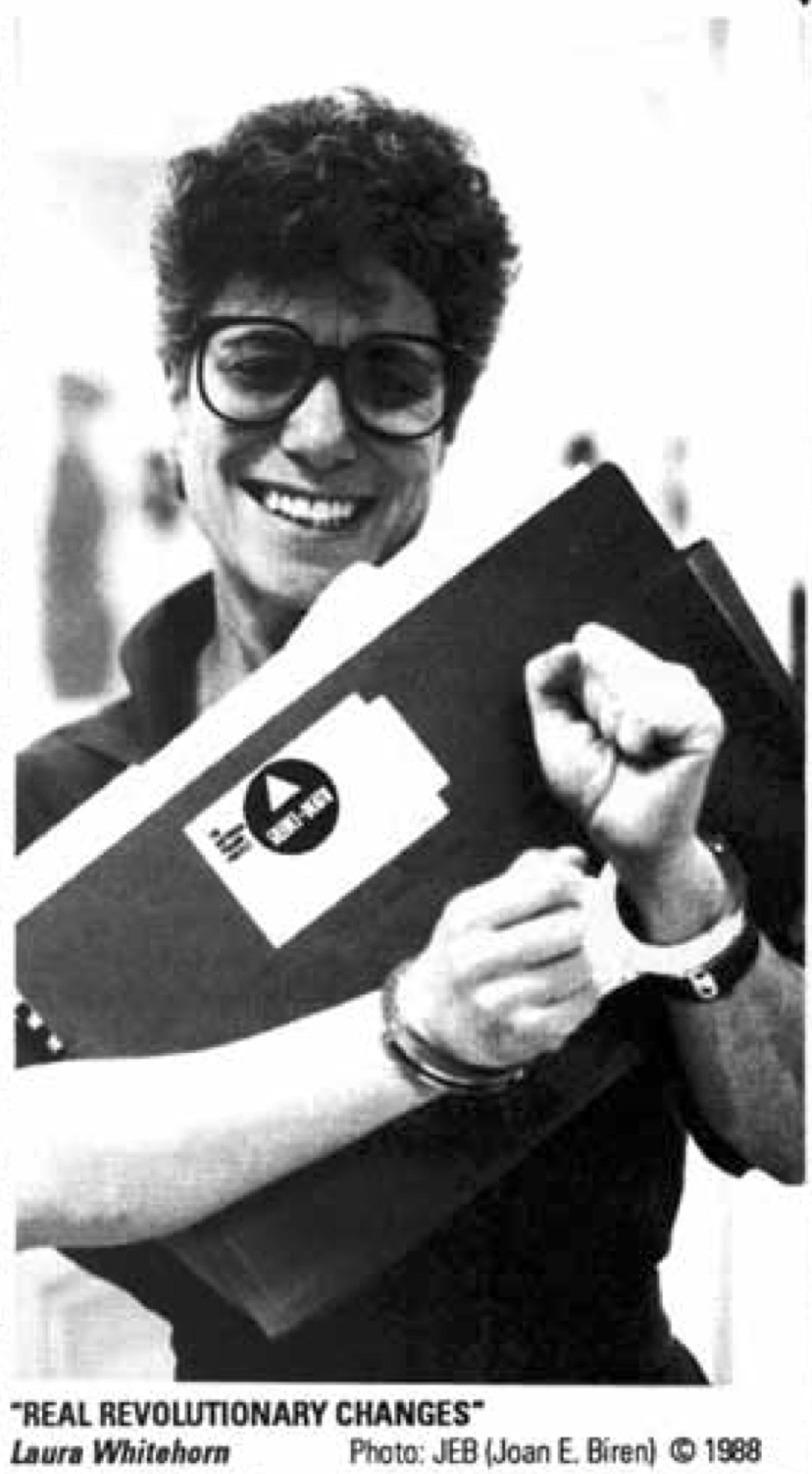

Laura Whitehorn — Arrested on weapons possession in 1985. Unconvicted. Remains in preventive detention for four and a half years after arrest. Faces 45 years on conspiracy charges.

Linda Evans — Arrested on weapons possession. Convicted for making false statements to purchase four legal handguns. Sentence: 40 years. Faces 45 more years on conspiracy charges. Time served: now in prison.

— Susie Day, OutWeek Magazine No. 20, November 5, 1989, p. 19.

#outweek#issue 20#lgbt history#political prisoners#incarceration#prison#laura whitehorn#linda evans#kkk#oliver north#don black#michael donald bray#robert louis white#white supremacy#racism#susie day

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"Yes. I'm a lesbian. It's part of what motivates me to be a revolutionary."

Lesbian Political Prisoners

"Gay people have no stake in a system that is racist and sexist and that impoverishes some sectors of this society in order to enrich others ... I don't think that we will ever be liberated under this system. We may have a few more rights, but we'll never win our liberation as human beings without some kind of real revolutionary changes."

Shortly after she began to make these realizations in the late 60s, Laura Whitehorn was a Chicago housewife. She came out as a lesbian at about the same time that the Black liberation struggle and the anti-Vietnam War movement had convinced her that nothing short of revolution would guarantee human equality. And, for over 20 years, Whitehorn was an activist in women's communities and Black and Puerto Rican movements. In 1985 she was arrested for weapons possession.

In her statement to the court, Whitehorn declared that she lived by "revolutionary and human principles." Those words, said the judge, were reason enough to hold her indefinitely in preventive detention, under the Bail Reform Act of 1984. Four and a half years later, Whitehorn, at 44, remains in prison without bail. She has yet to be tried on the charges for which she was arrested. During her years of incarceration, she has been placed in 11 different jails and prisons, allegedly for security reasons. After she was moved to the Federal Correctional Institute in Pleasanton, California, Whitehorn was reunited with her friend, Linda Evans.

Evans, the daughter of an industrial contractor and a schoolteacher, had lived all her life in the Midwest, and had come to Chicago in the late 60s to enter college. She met Laura Whitehorn in the SDS, and has been a lesbian activist ever since. Twenty years later, she smiles and declares: "Yes. I'm a lesbian. I'm proud of it. ... It's part of what motivates me to be a revolutionary."

Linda Evans has spent her life as a community organizer. She organized so well against racism in lesbian, Chicano and Black communities, in fact, that the Ku Klux Klan put her on its death list. Evans bought four handguns to protect herself. She was arrested in 1985 for weapons possession, and sentenced by the state of Louisiana to 40 years in prison for making false statements to purchase these guns. At the age of 42, Linda Evans is serving a reduced sentence of 35 years. "The thing that's interesting about the Louisiana case," she says, "is that it's the same jurisdiction where the Ku Klux Klan tried to mount an invasion of Dominica, a Black island in the Caribbean in 1981. Don Black had ten other men with him; he had almost a million dollars in cash; they had a boat full of illegal weapons, machine guns and stuff. ... And he received a total sentence of three years and was out in 24 months."

Laura Whitehorn and Linda Evans are two of an estimated 200 progressive and leftist political prisoners in the United States. Held indefinitely without bail, convicted on exaggerated, if not false, charges, sentenced to many more years in prison than right-wing defendants, these prisoners are invisible to the general public. Their numbers include a range of activists, from New Afrikan and Puerto Rican nationalists who identify as "prisoners of war" and support armed struggle, to sanctuary workers and anti-nuclear protestors, who have received as many as 18 years in prison for their nonviolent opposition to government policies. The gay and lesbian movement, increasingly radicalized by government indifference to the AIDS crisis, is becoming more aware of these prisoners. In doing so, lesbians and gay men have begun to ask: What makes these people so threatening to our government? What does it mean to us and our movement that these prisoners exist?

Whitehorn and Evans are now in the Detention Facility in Washington, D.C They await trial there with four other political prisoners — Susan Rosenberg, Marilyn Buck, Alan Berkman and Tim Blunk — for the 1983 bombing of the U.S. Capitol Building and three other government sites in the D.C. area. The bombings, protesting the invasion of Grenada and other acts of U.S. foreign aggression, damaged property but injured no one. The defendants — who face up to 45 years in prison, if convicted — express support for the bombings, but maintain that they did not carry them out. The government, moreover, admits that it does not know who committed the bombings and that it has neither evidence or witnesses to prove that any of the accused were directly involved.

Yet the Resistance Conspiracy trial, as the defendants call it, promises to be one of the most politically vindictive events in decades. Although the trial will probably not take place until early 1990, the government has already installed a bulletproof plexiglass wall to separate defendants from the rest of the courtroom. Special video monitors have also been positioned to observe spectators and the defense table, but not the prosecution. These courtroom security measures — which legal experts say will intimidate spectators and make an impartial jury trial impossible — are virtually unprecedented in U.S. judicial history. They were noticeably absent when Oliver North was tried last spring, in the same courthouse.

North, who admitted having helped engineer the illegal drug and weapons sales that killed thousands of Central Americans, was never held in any form of preventive detention, and was not sentenced to any term in prison. "So the whole case is political," concludes Nkechi Taifa, attorney for Laura Whitehorn, adding "The whole pre-trial detention is political. And the government should not be allowed to use the criminal justice system to suppress political opposition."

The indictment, if successful against these defendants, may help set precedents in suppressing political activism. Because the government has no direct evidence to convict the six, it has charged them with aiding and abetting, and with conspiracy to "influence, change and protest policies and practices of the U.S. government...through the use of violent and illegal means." These are ingeniously broad charges, which could, in the future, be brought against an increasing number of protestors, whose dissent is labelled "violent" or "illegal" by the government. And though it may not be used immediately against actions like sit-ins and blockades, it could well discourage them from happening. "They want to make sure that they can determine the boundaries of our activity at every point," says Linda Evans.

Conspiracy and aiding and abetting charges are traditionally easy to prove. Once a jury is convinced that defendants hold the same political sympathies, convictions can be obtained through mere circumstantial evidence. The prosecution in this case will use the defendants' own political writings and personal letters — exempt here from First Amendment protection — to establish that the six have all known each other and oppose government policies. A jury might, therefore, have no trouble finding a "conspiracy," given such evidence as Evans' and Whitehorn's lifelong friendship and the fact that both were underground at the time of their arrests. "Linda and I have known each other longer than anyone else in this case," Laura Whitehorn says. "I'm proud of that. And so, some of our proudest history is what they're going to bring against us."

Going underground, leaving friends and lovers perhaps forever, was a difficult decision for Whitehorn and Evans. But as their activism grew, including Whitehorn's support work for the Black Panther Party, so did FBI surveillance. When Panther leader Fred Hampton was murdered, Whitehorn thought very hard about what Malcolm X had said before he was killed. "I'll never forget the picture of the Chicago police carrying [Hampton's] body out on a stretcher and grinning. ... And it was proven that not a single shot had been fired from inside the apartment. It was a complete assassination of this man. ... We all pretend that it doesn't happen here. But they do things that actually torture and kill people. And I just feel like it's the height of self-deception to think that we can draw lines about what we will and will not do to stop that kind of thing."

Their years of support not only for the rights of lesbians and gays, but also for Black and Puerto Rican nationalist groups, made them phenomenally threatening to the government. Eventually, Whitehorn and Evans decided, they could be freer to do their political work if they dropped out of the public movement. Observes Linda Evans, "If we really want to change the power structure, I think there's going to have to be a revolutionary movement in this country. But, in order to build it, we have to build the capability that's not completely infiltrated and controlled by the government, the FBI. ... That applies not only to the AIDS movement, but to all the solidarity movements. ... It's just not enough to believe that we're going to be able to win change through the legislatures."

Although they have lived in different parts of the country, Evans and Whitehorn always remained close, always supported one another in a variety of political work. So, while Linda Evans was living in a women's commune in Arkansas, fighting developers who were clearing the land with Agent Orange, Laura Whitehorn was in Boston, taking over the Harvard Building with a group of anti-imperialist women — an action that led to the founding of the Boston/Cambridge Women's School. And while Whitehorn was helping to defend Black homes during the anti-busing violence in Boston in the mid-70s, Evans was teaching women to print in a press collective in Texas. While Evans was struggling against the Texas Neo-Nazis and the Klan, Whitehorn was organizing the Madame Binh Graphics Collective in New York City.

"We come out of a sector of the anti-imperialist movement that was dominated by women and lesbians," says Laura Whitehorn, "and I think the government is very well aware of that. And that's why one of the things that we've seen in the last few years was he development of the Lexington High Security Unit, to deal with women political prisoners."

The Lexington High Security Unit was opened in 1986 and within months became infamous for its isolation and sensory deprivation measures used to subdue women whom the Bureau of Prisons deemed "assaultive" or "escape prone." Yet the women assigned to the Unit — political prisoners Susan Rosenberg, Silvia Baraldini and Puerto Rican "prisoner of war" Alejandrina Torres — had never been convicted of injuring or assaulting another person. Nor had any of them presented behavioral problems while in prison. Finally, in 1988, after an international campaign that included the efforts of Puerto Rican groups, women's communities, church organizations and Amnesty International, the Lexington HSU was closed by court decree as a violation of the prisoners' First Amendment right to political freedom.

The closing of Lexington is known to many activists. What is not yet known is the fact that the government appealed the closing, and on September 8, 1989, won its appeal. Implications for every political prisoner in this country are devastating. "Now," says Linda Evans, "the Bureau of Prisons has absolute license to put us in any conditions it wants to, based solely on our past political affiliations and beliefs."

Although the government may not reopen the Lexington HSU, it has begun to create conditions in the Shawnee Unit for women in Marianna, Florida, that duplicate if not intensify, those of Lexington. Already, continues Evans, "They have installed television sets in the cells, which means they can lock us down and say that we're having social interaction via television, instead of via human beings."

"Lock down" is a form of solitary confinement familiar to political prisoners. People in lock down are caged in tiny, often parasite-infested cells for 23 hours each day. They are allowed out, in handcuffs and leg shackles, for one hour to shower and make phone calls. If Evans, Whitehorn, Susan Rosenberg and Marilyn Buck are convicted of the D.C. bombings, say defense attorneys, they will undoubtedly be sent to Marianna. Their codefendants Alan Berkman and Tim Blunk will be sent to the Marion Prison for men in Illinois, which is under permanent lock down.

Tough new "anti-crime" campaigns are making an open secret of the fact that U.S. prisons are used to dispose of unwanted sectors of society. In April 1989, the Justice Department reported that there was a total of 627,402 men and women in U.S. prisons. This is the largest prison population of any country in the world and, in less than five years, it is expected to rise to well over one million. Most U.S. prisoners are people of color, who, outside prison, represent "minority" populations. The rate of Black imprisonment alone is twice that of South Africa. "What I see in this jail," says Laura Whitehorn, "and in every jail I've been in, is genocide against Black people, and I think it's worse than it ever was."

Given our society's dependence on prisons, it is in the interest of the social "order" to strip prisoners of any form of self-respect. Women are continually under threat of sexual attack by male guards, and frequently raped with speculums or hands by prison officials in search of "contraband." Male prisoners are often beaten when they refuse to obey an order. Prisoners of both sexes are routinely subjected to humiliating — and unnecessary — strip searches. "Sexuality is not possible in prison," says Laura Whitehorn. "Sex is, but sexuality as a creative form of human expression — forget it. Certainly not under these conditions."

Yet in filthy, overcrowded U.S. prisons, lesbian and gay prisoners still attempt to love each other. They must literally risk their lives to have sexual relationships, since prisons have categorically refused to give out condoms or materials on safer sex. "They can bust you at any point," says Linda Evans. "Because sex is illegal in prison. And so you can be punished for having loving relationships, even though that clearly is one of the most rehabilitative things that can happen to someone."

Obviously, the primary purpose of U.S. prisons is not rehabilitation. While heterosexual prisoners in the general population may at times receive conjugal visits from their spouses, gay prisoners cannot even afford to acknowledge that they have lovers on the outside. Recently, report Whitehorn and Evans, a male prisoner's lover of three and a half years was stricken from the visiting list after authorities discovered that the prisoner was gay. Suspected of being gay or of IV drug use, prisoners in some states are tested against their will for HIV, the virus associated with AIDS, although treatment is rarely available. Once discovered to carry it, they are subjected to enormous abuse and contempt.

Whitehorn and Evans knew that they were taking a great risk in coming out as lesbians in prison. They realized they would open themselves up to the same kind of danger and humiliation that gay people face daily on the street; only in prison, the danger would be constant and inescapable. But coming out, they decided, was something they could do to continue to resist. And being open about their sexuality at times connects them solidly with the women around them. "I'm not saying this is Sisterhood City," remarks Laura Whitehorn, "but I find that there's something about talking to women about why I'm a lesbian, which has a lot to do with my own feelings of love for women and affirming that love, that come back positively."

Their defense attorneys see the "conspiracy" as the government's, not their clients'. If everything goes according to government plans, they say, Laura Whitehorn, Linda Evans and their codefendants will die in prison. They will be known, if they are known at all by the general public, as "terrorists," with a bizarre taste for violence. And those on the outside will judiciously avoid any semblance of extremes in their political speech or activity.

But all this may not prove to be so easy for the government. Already, activists have begun to learn about the case and respond. And 80 percent of this response, say Evans and Whitehorn, comes from lesbians and gay men. An open letter asking the government to drop the charges against the Resistance Conspiracy six has appeared in several gay and progressive publications; so far, 12 ACT UP chapters across the country have signed it, as well as hundreds of individual lesbians and gays. People in the community have also begun writing to these prisoners. Linda Evans speculates on the reason for this involvement:

"I think some of that is because the gay and lesbian movement is extremely under attack, because of the problems that our community has with AIDS and because of the rise in violence. ... and of the increasing sexism in our society in general. And I think that that means lesbians and gay people have recognized that, being under attack, we have to fight back."

— Susie Day, OutWeek Magazine No. 20, November 5, 1989, p. 16.

#outweek#issue 20#lgbt history#hiv aids#act up#politics#protest#prison#political prisoners#incarceration#lesbian#laura whitehorn#linda evans#racism#resistance conspirancy#news#susie day#fighting invisibility#photo#jeb#joan e. biren

1 note

·

View note

Photo

ACT UP Alleges Assault by Top Giuliani Aide

DA Stymies Attempt to File Charges

NEW YORK [November 5, 1989] — Members of ACT UP ran into some legal snags this week in their attempt to file criminal charges against Republican/Liberal mayoral candidate Rudolph Giuliani's infamous right-wing media advisor Roger Ailes.

The assault and harassment charges stem from a violent incident which took place at last Monday's Liberal Party Dinner, where a group of six ACT UP protesters were reportedly set upon by "an angry mob of Giuliani supporters."

On Thursday, accompanied by ACT UP lawyer Stuart Weinstein, three members of ACT UP appeared before a criminal court judge, requesting a summons forcing Ailes to appear in court to answer the charges.

The judge, however, declined to issue the summons, referring the matter to the District Attorney's office.

[...]

The tumult began soon after ACT UPers snuck into the main ballroom of the Sheraton Center Hotel and began the chant "Racist, sexist, anti-gay...Rudy for mayor...no way."

During the ensuing scuffle, eyewitnesses and news accounts allege, Mr. Ailes grabbed ACT UP member Kevin Otterson from behind, gripping him in a tight stranglehold. Otterson further alleges that Ailes used his free hand to choke off his air supply and that he was only able to breath freely when Ailes let go five or ten seconds later.

Examined Tuesday by a doctor at St. Vincent's hospital, he was diagnosed with "post concussive syndrome and muscle trauma to the neck. Although Otterson has yet to undergo recommended neurological tests, he told OutWeek that his doctor expects him to fully recover.

The intention to file the criminal charges was announced at a press conference Wednesday, where ACT UP members demanded that Giuliani publicly apologize for the violence and name-calling and force his campaign workers who were involved to come forward.

Contradicting ACT UPers' claims and an account in last Tuesday's Daily News, Carl Grillo, the Executive Director of the New York State liberal Party, vehemently denied that the scene was a violent one and that Mr. Ailes was prominently involved.

[...]

But Kevin Otterson and his ACT UP compatriots tell a wholly different story.

According to them, as soon as their chant went up, at least 30 Giuliani supporters descended upon them yelling anti-gay epithets and pushing and shoving them from the ballroom.

Ira Manhoff recalls hearing one angry man yell "You filthy faggots," as he was shoved abruptly from the packed room of Liberal Party regulars and Giuliani supporters.

As soon as the group had been corralled into the hallway outside the ballroom, one eyewitness claims, Ailes appeared and began shouting "No Cameras, No Cameras," as it became evident that the violence was escalating.

Meanwhile, Otterson, who had previously been ejected, was making his way back towards the doors to the ballroom. It was then, according to several witnesses, that Ailes ran up behind him, snatched him around the neck, and began moving him towards the top of the long staircase at the end of the hall.

"He choked me just long enough for me to realize I couldn't breathe," Otterson says.

Asked if the man who grabbed him said anything to him, Otterson responded that Ailes said into his ear, "You little motherfucker."

Manhoff says he saw Ailes pushing Otterson towards the top of the staircase "as if he was going to push him down the stairs." "That's when I got frightened and started to grab on his [Ailes's] arm," he said.

Otterson says he has no doubts the man who attacked him was Ailes. He identified Ailes a day later from a photograph in Newsday.

— Ben Currie, OutWeek Magazine No. 20, November 5, 1989, p. 14.

#outweek#issue 20#lgbt history#hiv aids#act up#violence#rudy giuliani#roger ailes#protest#kevin otterson#ira manhoff#stuart weinstein#news#ben currie#photo#bill bytsura

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Comic by Jennifer Camper, OutWeek Magazine No. 20, November 5, 1989, p. 10.

4 notes

·

View notes

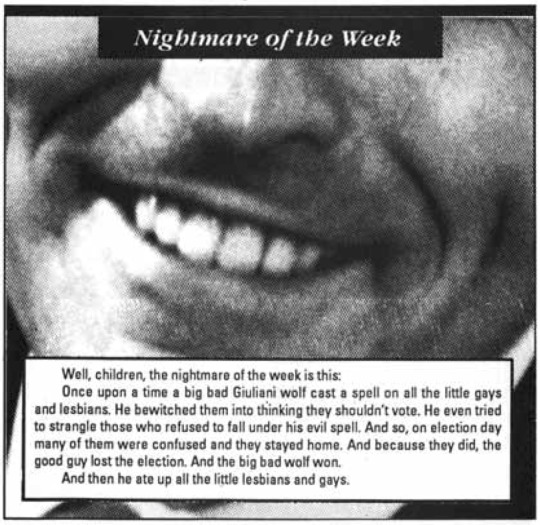

Photo

Well, children, the nightmare of the week is this:

Once upon a time a big bad Giuliani wolf cast a spell on all the little gays and lesbians. He bewitched them into thinking they shouldn't vote. He even tried to strangle those who refused to fall under his evil spell. And so, on election day many of them were confused and they stayed home. And because they did, the good guy lost the election. And the big bad wolf won.

And then he ate up all the little lesbians and gays.

— "Nightmare of the Week," OutWeek Magazine No. 20, November 5, 1989, p. 9.

2 notes

·

View notes