Photo

1 note

·

View note

Photo

“If I had my life to live over, I would do it all again, but this time I would be nastier.” -Jeannette Rankin, the first woman elected to Congress, took her seat in 1917, two years before the passage of the 19th Amendment.

#nastywomen#womensmarch#whywemarch#nastywoman#history quotes#congress#congresswoman#JeannetteRankin#history#american history#women's rights#awomansplaceisintherevolution

0 notes

Photo

#inauguration 2017#president#u.s. president#theodore roosevelt#history#history quotes#u.s history#american history#quotes

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

There Will Be Blood

By Scott Lipkowitz

Aboard the Drommedaris en route to Table Bay on the southwestern tip of Africa, Dutch Commander Jan Van Riebeeck had ample time to consider the orders handed to him by his employers, the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC) or Dutch United East India Company. These instructions, drafted and agreed upon by the VOC's Council of 17 some nine months before Riebeeck set sail from The Netherlands on December 24, 1651, tasked him and his men with the establishment of an outpost on the Cape Peninsula. This base, constructed near the slopes of Table Mountain, would provide a port where company ships "may safely touch...and obtain meat vegetables water and other necessities."

The Cape Peninsula, or the Cape of Good Hope as it was named in the late 1400's by Portuguese navigator Bartolomeu Dias, was an important strategic way-station for European trading vessels and warships. As naval and navigational technology improved throughout the 16th and 17th century, so too did the reach of European trading networks; placing a premium on the creation of strategic bases of operation at which vessels could shelter, refit, and resupply. In the 1650's the journey from Holland to the Cape took the better part of four months, and that was only a fraction of the distance Dutch merchant vessels would have to travel before reaching trading ports in India and making the return journey to Europe. Long voyages at sea meant limited access to fresh water and the produce necessary to stave off disease, most notably scurvy. And if the sailors needed to keep the ships moving were unable to do so because of ill-health, the goods necessary to keep the money moving would fail to reach their final destinations. The Cape, with its Mediterranean climate and freedom from tropical diseases, was a supremely desirable location.

However, as in all human migrations, the European commercial expansion ran into a significant problem: other humans. The Cape Peninsula was not devoid of indigenous occupants - the San and Khoikhoi had occupied the region for millennia - and the directors of the VOC were well aware of this fact. Immediately following their instructions to Riebeeck for the creation of a shipping station, the Council of 17 presented him with their appraisal of the local population and what he should do about them: "go ashore with a portion of your men, taking with you as much material as you require for a temporary defense against the natives, who are a very rough lot." Riebeeck was inclined to agree, stating in a letter sent to the VOC as an offer of his services, "they [the local population] are not to be trusted, being a brutal gang, living without any conscience." Riebeeck argued for the construction of a stronger, highly defensive fortification commanding the ascent of the neighboring Lion's Head hill, warning his potential VOC employers that he had "heard from many who had been there and were trustworthy, that our people have been killed without any cause."

This sentiment put Riebeeck in direct opposition to that espoused by two VOC employees, Proot and Jansen, who had spent more than a year residing in the Cape. In their 1649 report to the Council of 17, they urged the creation of an outpost on the Cape, propounding upon its benefits, and seeking to sooth the fears of those who believed the natives to be "brutal and cannibals, from whom no good could be expected." While they could not "deny that [the Khoikhoi] live without laws or police...nor that some boatsmen and soldiers had been killed by them," Proot and Jansen nevertheless believed that "the cause [for such behavior] is generally not stated by our people in order to excuse themselves." In other words, if you knew what we had done to them, you would not find their behavior at all surprising or alarming. Where Riebeeck believed the Dutch to be wholly without sin, Proot and Jansen were unconvinced.

The Khoikhoi with whom the Dutch initially interacted were pastoralists, driving their cattle herds between seasonal areas of forage. In the decades before Riebeeck's arrival, the Khoikhoi regularly traded with passing European vessels, but such commercial ventures were not always fairly entered into. Cattle were regularly taken without recompense, leading to often violent retaliation. All of this seemed reasonable to Proot and Jansen. "We are quite convinced" they stated, "that the peasants of this country [Holland], in case their cattle are shot down or taken away without payment, would not be a hair better than these natives if they had not to fear the law." Without the specter of big brother, in this case the monarch and his legal apparatus, the people of Holland would also be engaged in an endless revenge cycle against those who wronged them or stole their property. At the core, the Dutch and the Khoikhoi were essentially the same: they both would not be too keen on someone else taking their possessions and their resources without receiving something in return.

This is not to suggest however that Proot and Jansen viewed the Khoikhoi as equals - the Dutch after all had 'civilization.' Instead their assertion merely implies that if stripped of the supposed civilizing influence of the law, the Dutch would be prone to the same levels of savagery as the Khoikhoi. What Proot and Jansen were arguing, was that by using this understanding - that violent attacks were merely reprisals for unfair dealings - the Khoikhoi could be kept at bay. The methodology used to counter the Khoikhoi was where the difference of opinion could be found. While Riebeeck wanted to use the stick, Proot and Jansen saw that carrots could be as effective, if not more so, in achieving the company's objective.

That objective was nothing less than the maintenance of the literal bone and sinew which moved the vast machinery that made the VOC's profits. In relation to this, all else, including the Khoikhoi, were merely obstacles to be overcome, no matter what the cost. In the same breath that he condemned the character of the Khoikhoi, Riebeeck also reminded his employers that strong fortifications would also protect the vital station from "the English, French, Danes and especially the Portugese, who are jealous of the enlargement and prosperity of the Company, and let no opportunity pass to hinder it as much as possible." The Khoikhoi were just one more opposing tribe whom the Dutch must out-compete.

A Sea Anchor

On April 5, 1652 the Drommedaris sighted Table Mountain. Shots were fired to signal her sister ships, their echoing cannonade marking the beginning of the tense history of Dutch - African relations.

Riebeeck wasted no time putting his instructions into action. He and his men constructed a fort, set out the arrangements for a Company garden, erected a hospital, and constructed a shelter for cattle and sheep. Vegetables, milk, fresh water, and medical care was provided for passing Company ships. Meat from Company livestock filled their larders, but it was not enough to satisfy demand. Khoikhoi herds made up for the shortfall, and Reibeeck attempted to take the stance of Proot and Jansen in his dealings with them. Older histories insist on an almost extreme benevolence towards the Khoikhoi, no doubt to set up a fictitious European blamelessness for what would eventually transpire; but, at least in the initial years of the Cape settlement's existence, a perhaps tense peace seemed to exist between the two groups.

All of that would take a turn for the worse as the settlement's financial burden began to outweigh its benefit. Despite offering a much needed respite for weary merchant crews, the Cape settlement was a monetary sea-anchor on the VOC. Five years into the enterprise, Riebeeck's outpost was yet to achieve self-sufficiency. In an attempt to cut their losses and increase production the VOC acquiesced to Riebeeck's request to expand the limits of the station. According to historian Martin Meredith, writing in The Fortunes of Africa, the VOC, in 1657 released "thirty-nine of its employees from their contracts and [placed] them on thirty-acre landholdings...six miles from the fort." Over the next two years further company employees were settled in the adjoining area as "free-burghers" or boers (farmers), who despite their designation, were subject to company authority. By 1659, what had started as a small enclave beneath the western slopes of Table Mountain had grown into a proto-colony, usurping the ancestral grazing lands of the neighboring Khoikhoi.

Conflict, as Proot and Jansen had correctly observed, was now inevitable. Pushing back against the continued encroachment, the Khoikhoi retook farmland on the eastern slopes stating, according to a history produced by an English clerk in the 1880's, that their aim was "to 'dishearten the colonists by taking away their cattle, and if that did not produce the effect, then to burn their houses and corn until they were forced to go away.'" Whether or not this was actually expressed as such - and once again this comes from a British colonial official writing for an audience predisposed to viewing the Khoikhoi as savages worthy of contempt, so take it with a grain of salt- the Khoikhoi nonetheless carried it out. Months of subsequent conflict resulted only in stalemate. Riebeeck decided to meet at the negotiating table.

If We Go To Holland

The ensuing exchange between Riebeeck and the leaders of the Khoikhoi tribes was recorded in the Dutch commander's journal. He, and the rest of Europe, may have believed the indigenous populations of the continents they subdued were mindless brutes and savages, devoid of civilization; but the arguments with which the Khoikhoi confronted him were anything but mindless or uncivilized. The Khoikhoi grasped the gravity of their situation, and presented logical counterarguments to the unjust actions of their would-be neighbors.

"They dwelt long on our taking every day for our own use more of the land," Riebeeck records, "which had belonged to them from all ages and on which they were accustomed to depasture their cattle." The Khoikhoi pointed out that the settlement of company boers on their land had been done without so much as a consultation. Happy to trade with the Dutch when they remained within the confines of the Cape settlement, the Khoikhoi were now expected to simply abandon the best pasture land. What were they supposed to do when confronted with such blatant disregard? Access to the land had to be restored they asserted, to which Riebeeck retorted "that there was not grass enough for [Khoikhoi] cattle, and for [Dutch] also." While Riebeeck may have assumed such an argument would throw the Khoikhoi leadership for a loop, they would not be so easily assailed. " 'Have we then no cause to prevent you from procuring any cattle?," the Khoikhoi replied, "'For if you get many cattle, you come and occupy our pasture with them, and then say the land is not wide enough for us both. Who then can be required, with the greatest degree of justice, to give way, the natural owner or the foreign invaders?'" Perhaps most pointedly the Khoikhoi desired to know of Riebeeck "whether, if they were to come into Holland, they would be permitted to act in a similar manner [?]"

Such penetrating questions make plain the Khoikhoi's sober and pragmatic assessment of what had caused the conflict and their realization of the simple truth that if the tables were turned, the Dutch would not act any differently. Riebeek's inability or refusal to straightforwardly answer this last remark speaks volumes about its truth. Ultimately he fell back upon a weak defense of Dutch actions, informing the Khoikhoi leaders that "they had now lost the land in war and therefore could only expect to be henceforth entirely deprived of it." Riebeeck invited them to try and expel the Dutch, commandeer the fort, and return things to the way they were, "if they had the courage." If such an attempt were made however, the Khoikhoi "would become, by virtue of the same right [conquest] owners of the Fort...for as long as they could hold it," but if the Khoikhoi "were disposed to try that, we [the Dutch] should consider of what we must do." For the Khoikhoi leadership who so soberly and logically argued their case, such a veiled threat of further violence would not be overlooked. Riebeeck's might-makes-right answer to their rational appeals for justice, while appalling to us, only reinforced what the Khoikhoi already understood. While they still fought with bow and arrow, the Dutch had cannon and light firearms; against such a threat their options were severely limited.

Peace between the two parties was reinstated in 1660. The Khoikhoi retained possession of the cattle they had taken from Dutch boers and were absolved of any war time reparations. Yet, despite the Khoikhoi's reasoned and nuanced argumentation, their eventual flattening by the steam-roller of colonial expansion was now all but guaranteed. The Khoikhoi recognized VOC sovereignty over the land settled by the Boers, opening up the door to further conquest "by the sword." Though certainly well aware of the precedent they were setting, without comparable arms and numbers, all the Khoikhoi could do was resist until their strength had been exhausted.

Carrots and Sticks

Riebeeck's description of his negotiations with the Khoikhoi seems to betray a sense of incredulity at their insistence of their rights to the land which had been the home of their ancestors. Deftly parrying every straw-man argument Riebeeck threw at them, the Khoikhoi attempted to appeal to some higher moral code or sense of justice. However, Riebeeck's own words demonstrate that such appeals, though well grounded, would have never swayed his actions or decisions. Having taken the land from the Khoikhoi, Riebeeck wrote, "it was our intention to retain it."

In those few words the whole of human land conflict is succinctly summed up. Having tried the carrots of Proot and Jansen, and employing the stick of land appropriation and eventual violence, Riebeeck was determined that his tribe, the Dutch, and more specifically the VOC, would come out on top. Nothing would dissuade him from that goal. If the Khoikhoi are guilty of anything in this exchange, it is perhaps attempting too high-minded an appeal against the base irrationality of profit and commercialism. Furthermore, the record of this meeting unequivocally demonstrates the consistency of the human spirit; the "essential essence of water" as historian Victor Davis Hansen put it. The same forces which over-ran the Khoikhoi are still in operation today, from the Amazon to the badlands of North Dakota. If the ghosts of the Khoikhoi, and the message their words yell out to us from across the centuries tells us anything, it is perhaps this: that when resources are the object of humanity's contention, it may be too much to hope that there will not be blood.

_____________________________________________________________________

Notes:

Meredith, Martin. The Fortunes of Africa: A 5,000 -Year History of Wealth, Greed, and Endeavor. Public Affairs. 2014.

"Instructions for the Officers of the Expedition Fitted Out for the Cape of Good Hope to found a Fort and Garden There." Precis of the Archives of the Cape of Good Hope, Volume 5. W.A. Richards & Sons. 1896. https://archive.org/details/precisarchivesc03riebgoog

Jansen and Proot. "A Short Exposition of the Advantages to be Derived by the Company from a Fort and Garden at the Cape of Good Hope." Precis of the Archives of the Cape of Good Hope, Volume 5. W.A. Richards & Sons. 1896. https://archive.org/details/precisarchivesc03riebgoog

van Riebeeck, Jan Anthony. "Report of Van Riebeeck on the Above 'Remonstrance' Addressed to the Directors of the General Company." Precis of the Archives of the Cape of Good Hope, Volume 5. W.A. Richards & Sons. 1896. https://archive.org/details/precisarchivesc03riebgoog

Noble, John. Official Handbook: History, Productions and Resources of the Cape of Good Hope. Colonial and Indian Exhibition Committee. 1886. https://books.google.com/booksid=mpOqZVuCrlIC&dq=they+alsOfficial%20Handbook:%20History,%20Productions%20and%20Resources%20of%20the%20Cape%20of%20Good%20Hopeo+asked+whether,+if+they+were+to+come+to+holland,+they+would+be+permitted+to+act+in+a+similar+manner&source=gbs_navlinks_s

van Riebeeck, Jan Anthony. Translated by H.B. Thom. Journal of Jan van Riebeeck Volume III 1659 - 1662. A.A. Balkema, publisher. 1958.

#history#south africa#south african history#cape town#cape of good hope#dutch east india company#khoikhoi#colonialism#therewillbeblood

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Theodore Roosevelt read 2-3 books a day, authored 45 during his lifetime, and had this to say on the virtue of reading. From his 1916 publication “A Book-lover’s Holidays In the Open”

0 notes

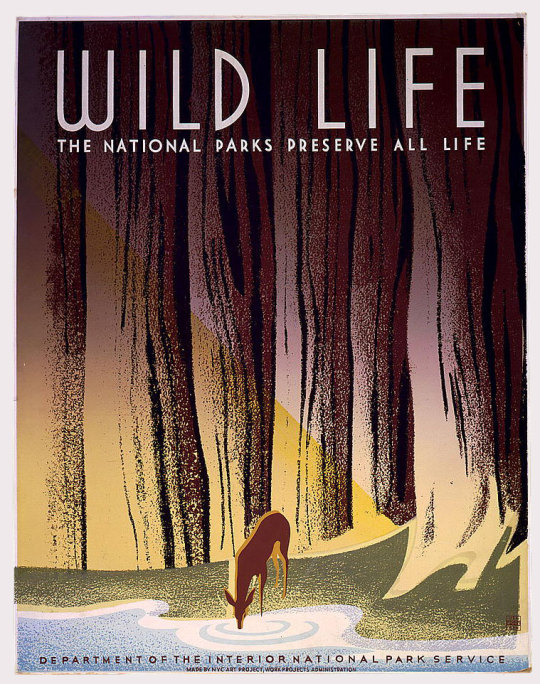

Photo

The Wildlife Division

By Scott Lipkowitz

The National Parks present a singular challenge, one expressed by naturalist and Park Service employee George Melendez Wright in his 1932 publication Fauna No I. "The unique feature of the case," Wright asserted, "is that the perpetuation of natural conditions will have to be forever reconciled with the presence of large numbers of people on the scene, a seeming anomaly. A situation of parallel circumstances has never existed before. Therefore, the solution can not be sought in precedent."

For the entirety of human existence, nature had merely been something to conquer, to utilize for human benefit, or to overcome. When human groups occupied a new territory they simply adapted and modified it according to their wants and needs - the thought of preserving landscape and wildlife was not one that commonly occurred. All of this changed however in the mid-19th century with the setting aside of the Yosemite Valley in 1864, and the establishment of Yellowstone National Park in 1872. For the first time an area was designated, not for economic development or profit, but as a protected zone, off-limits to the usual activities of human enterprise.

Yet this did not mean that these wilderness areas were safe. Cattle grazing, hunting, trapping, logging, mining, and exploitative tourism all continued in the newly created park system. Even as the ink dried on the 1916 Organic Act, establishing the National Park Service "to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same"; the parks which the Service inherited were subjugated to the economic and political needs of the nation. With one stroke of the pen President Wilson committed a federal agency to safe-guarding America's natural and historical treasures in perpetuity; with another, he bowed to the demands of the United States' involvement in the First World War, halving the size of Mount Olympus National Monument (now Olympic National Park in Washington) to open it up for timber production. There was even talk of slaughtering park bison and elk to provide canned meat for the troops. This reality presented Stephen Mather, the Park Service's first director, with an existential problem. If the Parks and their natural resources were to be made off-limits to the economic interests of the nation, then some other justification for their existence had to be made.

The Park Service's charter listed "enjoyment" as the primary public benefit of the National Parks; and in order to convince Congress to support and protect the park system from external threats, Mather and other Park Service officials had to show that the public was enjoying them. This meant putting people in the parks, by whatever means necessary. It also meant that increased human activity in the parks would bring Wright's assessment of the precarious balance between preserving the natural world and conceding to human demands, sharply into focus.

Never Too Many Tourists

Stephen Mather was an advertising prodigy. Marketing and selling "20 Mule Team Borax" (a type of soap still available today) to the housewives of late 19th and early 20th century America had made him a wealthy man; and he approached the problem of attracting people to the National Parks as one of marketing and publicity. Mather partnered with the railroads to promote a "See America First" campaign, wined and dined influential businessmen and politicians, brought his wealthy acquaintances on hiking and camping trips, hired the editor of the New York Herald, Robert Sterling Yard, to publish articles promoting the parks, and made a passionate embrace of the newest harbinger of individual freedom - the automobile.

Cars had the power to put the citizenry right in the heart of America's scenic places. In 1918 Yosemite saw a seven to one difference between those who visited by car and those who arrived via the rails. As car ownership increased in the early 20's, and "auto camping" became a popular past time, the National Parks received over one million visitors. Mather engaged with national and local automobile clubs, lobbied for more and better roads, and advocated for a "National Parks Highway" connecting the western parks. The more citizens who came, the safer the parks would be. Horace Albright, Mather's assistant recalled "There could never be too many tourists for Stephen Mather." The automobile was the Park Service's ticket to success.

By 1928 Park attendance had topped 3 million and Congress had taken notice, doubling the Park Service's annual appropriation with an emphasis on spending capital for road construction. Mather envisioned a major scenic roadway running through each of the Parks, but in order to ensure the preservation of the scenery, insisted that landscape architects be put in control so that the routes would conform to, and highlight, the natural vistas. Yet, while much attention was paid to the preservation of mountain passes and alluvial valleys, little if any thought was paid to the welfare of the living organisms who called those scenic highlights home.

In the 1922 Superintendents Resolution on Overdevelopment, park superintendents stated unanimously "that over-development of any national park, or any portion of a national park, is undesirable and should be avoided. Certain areas should be reserved in each park, with a minimum amount of development, in order that animals, forest, flowers and all native life shall be preserved under natural conditions." The resolution continued, at length, with barely a further mention of the impact of Park development on "animals, forest flowers and all native life." The superintendents intent was "to make the chief scenic features of each park accessible to the average visitor, but to set aside certain regions of each park, which will not be traversed by automobile roads, and will have only such trails or other development as will be necessary for their protection." Simply setting aside portions of the parks as road-free zones however, is not the same as making them human free zones. Citizens and wildlife would inevitably come into contact; and for the park's wild inhabitants, such interactions were often a zero-sum game. One of the key deficiencies in early Park Service thinking was the failure to perceive the parks as wild habitat for living organisms. This oversight, coupled with an emphasis on drawing in crowds, offered only two possible human attitudes towards their wild cousins: pest or spectacle.

Attitudes Towards Nature

These options formed the dual faces of an abysmal coin. On the one side, golf courses and grazing lands - condoned by Mather - pushed aside those species that competed for access to the land and its resources. On the flip side, Bison herds were stampeded by Crow Indians and cowboys for the benefit of onlookers, or corralled in pens in Service sanctioned zoos. In Untold Stories From America's National Parks, Susan Shumaker sums up the Park Service's position in regards to wildlife: the "Service had done little to protect the animal and birdlife in the system...The policies of the Service focused on natural resource manipulation, aimed not so much at preserving wildlife as at preserving and presenting to the public idealized versions of nature." When George Melendez Wright joined the Park Service in 1927 as an assistant Park Naturalist at Yellowstone, he determined that such an attitude had to be altered.

The son of a wealthy El Salvadoran mother and an American merchant mariner, Wright studied biology with the widely influential Joseph Grinnell at the University of California, Berkley. Grinnell emphasized his now cornerstone theory of the "ecological niche," which intimately tied species to their environments, and imparted upon Wright the need for the scientific management and understanding of the National Parks. Wright assisted Grinnell in the field, undertook scientific surveys of flora and fauna; and absorbed Grinnell's belief that ecological processes should be free from human interference.

Wright began his Park Service career just as the parks were receiving record numbers of visitors. In order to document their impact and ultimately reverse the pest or spectacle mentality, he would have to implement a scientific understanding of the parks as habitat. To do that, he would have to conduct surveys in the field and convince Park Service leadership to support them. In 1929 Wright proposed to his superiors that surveys be carried out, and by generously offering to fund the research with a portion of his own inheritance, was able to convince Horace Albright, Mather's assistant and eventual successor, to endorse the venture. One year later, Wright and two colleagues outfitted the first biological survey of the western parks.

Wild-life Problems

Over the course of three seasons in the field, Wright and his team made annual circuits covering over 11,000 miles of western park habitat. What they saw was not encouraging. Ben Thompson, Wright's colleague, summed up what they faced: "predatory animal control and corralling the ungulates so the public could see some of them, like the buffalo, and feeding the elk so they would concentrate for viewing, and feeding the bears at feeding stations, and making a big show of it." Rangers told them of the dynamiting of badger holes, extermination of coyotes and predatory birds, and the hunting of elk to free up pasture land for sheep and cattle. In Yellowstone, Wright documented the destruction of American White Pelicans, carried out because they "interfered" with the catches of recreational fisherman, resulting in the "reduction of the colony from about 600 to 250." Over the course of 8 years, beginning in 1923, eggs and adolescent pelicans had been systematically exterminated by park staff, with an estimated "175 killed each year." Wright saw to it that the practice was quietly ended.

Bears, perhaps more than any other species, came to embody the pest or spectacle view of nature. In Yellowstone, Wright observed "two grizzly cubs [who became] tame and were fed by hand around Old Faithful." In an effort to provide an entertaining version of nature, Park Service employees encouraged the feeding of bears, both black and grizzly, either at garbage dumps near developed areas, or by the tourists themselves. However, when the bears eventually raided campsites and vehicles, or simply would not desist in their search for free meals, visitors and rangers alike grew frustrated with them; assuming that the fault rested with the bears, and not with their actions. Wright commented on the situation in 1936:

It takes time to teach the visitors to our national parks that they are the ones who are short- sighted in feeding candy to a bear. After all, the average citizen expects more intelligence for a bear than he, as an educated person, has any right to expect. He goes on the assumption that if he feeds a bear two sticks of candy and does not want to give it a third, he is the one to say, "No, no." And he believes that the bear is to be accused of an unforgivable breach of etiquette and lack of appreciation for this piece of candy if it takes all the candy out of his hand and takes the hand with it, perhaps.

"Recognition that there are wild-life problems is admission that unnatural, man made conditions exist," Wright would state. And those unnatural conditions demanded that action be taken.

Remedies

Wright published his team's findings, his diagnosis of the problems, and his suggested course of action for returning the parks to a natural state of wild habitation in two works, Fauna No I and Fauna No 2. Putting an end to predator destruction, to the feeding of wild animals, the practice of corralling bison and other ungulates, and actively removing invasive foreign species from park habitats were just a few of the many actions Wright sought to have implemented. Ironically, the key to reversing the negative impacts of human intervention was further intervention; and Wright recognized that this too had the potential to lead to further trouble. "Due care must be taken," Wright emphasized, "that management does not create an even more artificial condition in place of the one it would correct." Unless an area was to be designated as true wilderness, an area completely off limits to humans - and the National Parks were never designed as such - active, rather than passive, scientifically grounded management and control would be required.

Horace Albright, and his successor Arno Cammerer, were the first two Park Service directors to become converts to Wright's plan. The Wildlife Division, headed by Wright and eventually employing 27 field biologists, was officially established by Albright on July 1, 1933 - no longer would Wright have to fund the activities of the Division out of his own pocket. Albright even went so far as to publish a memorandum calling for the complete end to predator destruction. Cammerer, in 1934, adopted Fauna No. I and its prescriptions for park management as official Park Service policy, and engaged Wright in a survey of potential "recreation areas" geared towards the leisure needs of the public. Such areas might, Cammerer hoped, help to relieve some of the pressure on wild-life.

Wright's policies were the beginnings of a paradigm shift. Susan Shumaker, writing in Untold Stories From The National Parks, summed up the effect: "For the first time, the preservation and restoration of resources was adopted by a government bureau and applied to an entire system of public lands. The recommendations of Fauna No. I, in their scope and their widespread impact, were almost immediate, and were unprecedented in the history of American public land management."

The shift, however, would prove to be short lived. Less than three years after the Wildlife Division's creation, Wright was killed on U.S. Highway 80 near Deming, New Mexico. He was 31 years old.

Without Wright's leadership, the influence of the Wildlife Division began to wain, and the old ways of catering solely to the needs and desires of park patrons returned. In 1939, 400 landscape architects were added to the Park Service's staff. That same year the number of biologists employed by the Division dropped to only nine. New Deal works projects such as the Civilian Conservation Corps broke ground on increased park development, and soldiers on leave from the Second World War were brought into the parks in ever increasing numbers as a way to help them deal with the traumatic experiences of battle. Wright's division tirelessly labored on, but its efforts were met with little consideration - putting people in the parks was once again the primary concern.

The Unique Feature

Today, one hundred years after the Park Service's founding, Wright's scientific approach to park management is at the forefront of Park Service policy; forming the cornerstone principle around which all else is built. However, the struggle to come to terms with the "unique feature" continues unabated. We may imagine that over the past century Wright's ideas have become firmly entrenched in the public's mind, or that the pest or spectacle outlook no longer exists; but such thinking is folly. Animals are regularly snatched or grabbed for the benefit of 'selfies', or taken into personal vehicles during cold winter days - the result of human ignorance. Subjugating the natural world for human enjoyment or self-aggrandizement, and the woeful misunderstanding of natural processes poses an ever-present threat to the preservation of the National Parks.

"Among the more important national resources," Wright stated, "perhaps none is more susceptible to the destructive influences of civilization than wildlife." The National Parks are unique, not because they are areas of natural beauty or the habitat for the flora and fauna of the United States. The parks are unique because they are the one area in which humanity strives to balance with, and not merely over-run, that which is wild. It is a balancing act with which we still struggle to find equilibrium. The desire to carve out a position for the parks as areas which are not true wilderness, yet not demolished by civilization, has been hard to fulfill. Historically we have not been exceedingly successful at it, and our reach often extends farther than we perceive. On this day, the centennial of the National Parks Service's creation, we must take pause to reflect upon this unique relationship, and upon the work of George Melendez Wright, who fought to bring it to the forefront of our consciousness.

______________________________________________________________________

Notes:

Shumaker, Susan. Untold Stories From America's National Parks: George Melendez Wright. http://www-tc.pbs.org/nationalparks/media/pdfs/tnp-abi-untold-stories-pt-09-wright.pdf

Burns, Ken. The National Parks: America's Best Idea. Online resources. http://www.pbs.org/nationalparks/history/

America's National Park System: The Critical Documents. Superintendent's Resolution on Overdevelopment, 1922. https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/anps/anps_2b.htm

America's National Park System: The Critical Documents. National Park Service Predator Policy, 1931. https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/anps/anps_2g.htm

#nps100#findyourpark#george melendez wright#joseph grinnell#national park#wildlife division#nps#nps2016#nps centennial#organic act#history#american history#1916

1 note

·

View note

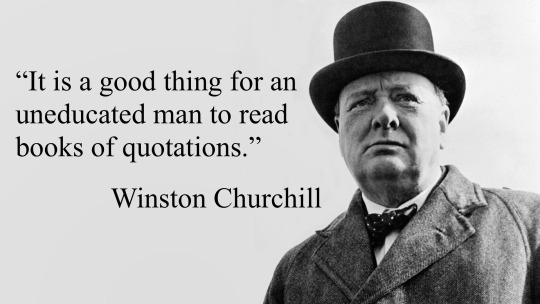

Photo

In a world conditioned to only think in 140 characters, it matters what those 140 characters say. In that vain, and to get you some more frequent history content, we'll be posting quotes from history for your thinking pleasure. To kick it off here's one from the maestro of quotes himself, Winston Churchill.

1 note

·

View note

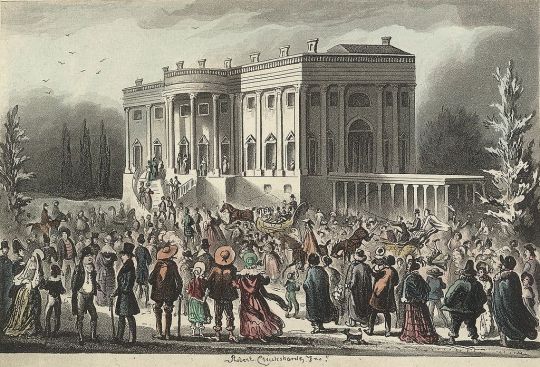

Photo

Smashing the Glass Ceiling

By Scott Lipkowitz

1848 was a year of revolution. In France, republicans deposed King Louis Philippe and declared the Second Republic. Nationalist tri-colors flew freely in Sicily and Prussia; and in Austria, new constitutions were promised to the many nationalities subject to its rule. In almost every European nation, democratic fervor took hold, with varying degrees of success. Though divided by language, culture, and nationality, one demand was held in common: universal male suffrage, and an end to the authoritarian rule of monarchs. Suffrage was also one of the issues on the minds of revolutionaries in the United States that year. These American revolutionaries however, did not bear colorful flags, or have princes at the head of their cause; nor did they call for the overthrow of the government of the United States. Instead, these American revolutionaries were demanding the overthrow of something much larger; a world order that had existed for almost 10,000 years. Their demand: the equality of rights for women.

On July 14th, the 59th anniversary of the storming of the Bastille in France, an American cry for liberty and equality appeared in the Seneca County Courier. It announced a "Women's Rights Convention - A convention to discuss the social, civil, and religious rights of women," and encouraged all women able to attend to gather at the Wesleyan Chapel in Seneca Falls, New York on the 19th and 20th of July. Among all those who would address the convention, only Lucretia Mott was prominently advertised. Mott was the daughter of a New England whaler, born on Nantucket island in 1793. A Quaker in her religious persuasions, Mott became a teacher on the mainland, eventually meeting and marrying James Mott while employed at the Nine Partners Boarding School in New York. The Motts eventually resettled in Philadelphia where, at the age of twenty-eight, Lucretia was ordained a minister by her fellow Quakers, providing her with a public outlet for her oratory. Both Lucretia and James became fervent abolitionists, operating a station on the Underground Railroad from their home, while Lucretia played a prominent role in the founding of the first Female Anti-Slavery Society. Though described as gentle and soft, her moral fortitude, ministry, and activity within the abolitionist movement elevated her into the public eye.

As a result of her status as a public figure, Mott found herself in the summer of 1840 in London; part of an American delegation to the World Anti-Slavery Convention. While the theme of the Convention may have been an end to the bondage of one man to another, the notion that the bondage of woman to man should also be abolished was anathema: female delegates were barred from being seated. As Stanton would later recount, "after going three thousand miles to attend a World's Convention, it was discovered that women formed no part of the constituent elements of the moral world." The American delegation objected, but to no avail: Mott and her fellow female abolitionists would be relegated to the spectator's gallery. There, as a passive observer of a movement she had done so much to advocate for, Mott was introduced to fellow American Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Stanton was born in 1815 in Johnstown, New York, the daughter of a judge, in whose office she learned of the plight of American women. Many of those who came before her father's court were the wives and daughters of rural farmers seeking restitution for lost funds, property, or progeny. However, granted no rights under common law as a result of their sex, almost all of these female petitioners were sent away without any hope of justice. It was a lesson Stanton would not forget as she pursued an education at the Troy Female Seminary outside of Albany. In London, Stanton would watch as her husband, Henry Brewster Stanton, a prominent leader of the abolitionist movement, participated on the convention floor.

The hypocrisy of a convention dedicated to ending enslavement, discriminating against another portion of the population on account of their sex was blatantly apparent to both Mott and Stanton. They soon began to commiserate, and, returning to the States, continued their correspondence. Working together they helped to shepherd the Married Woman's Property Bill through the New York State Assembly, seeing it become law in early 1848; a small victory in the struggle to establish universal legal rights for women. The high of victory, however, would be dampened by Stanton's personal struggles. When her growing family relocated to Seneca Falls, New York, the rigors of domesticity shook Stanton to despair. "The general discontent I felt with woman's portion as wife, mother, house keeper, and spiritual guide," she stated, "...and the wearied, anxious look of the majority of women, impressed me with the strong feeling that some active measures should be taken to remedy the wrongs of society in general, and of women in particular." A woman of intellect and action, Stanton felt stifled by the limited role offered to her as a housewife and mother. "All I had read of the legal status of women, and the oppression I saw everywhere, together swept across my soul, intensified now by many personal experiences."

Stanton would have the opportunity to vent her frustrations when, at the beginning of July, 1848 Lucretia Mott and her husband visited the nearby town of Waterloo, New York. There, in the home of Jane Hunt, Stanton, Mott, and women's rights activists Martha Wright and Mary McClintock, resolved to call a meeting to discuss the legal and moral plight of American women, posting the notice of their intent in the Courier. Taking the Declaration of Independence as their blue print, the five women restructured the nation's ideological foundation paragraph by paragraph, denouncing not the dominion of a foreign monarch and his many trespasses, but rather the dominion and trespasses of American men over their sisters, mothers, wives, and daughters, stating:

We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights: that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness...

The history of mankind is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations on the part of man toward woman, having in direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over her.

Chief among those injuries and usurpations was the denial by man of a woman's "inalienable right to the elective franchise." In no state were women allowed to vote, yet they were forced "to submit to laws, in the formation of which [they] had no voice." And those laws, drafted by and voted upon by men "in all cases, going upon a false supposition of the supremacy of man...[gave] all power into his hands." Fourteen years earlier, when petitions were submitted to Congress by the Female Anti-Slavery Societies, their very right to be heard at all was called into question by Congressman Howard of Maryland, who felt that women could best influence politics, morality, and the national character through their duty to their fathers, husbands, and sons. Laws at both the state and federal level were construed to deny married women the ability to own property, to obtain custody of their children in the event of divorce, or to obtain admittance to the halls of higher education. As industrialization spread throughout the United States in the early 19th century, many women were employed as laborers, and as teachers for an ever expanding population; but for their work they received "but a scanty remuneration." Everywhere that Stanton, Mott, and others looked they saw, and rightly so, a world founded upon "a false public sentiment" which gave "to the world a different code of morals for men and women, by which moral delinquencies which exclude women from society, are not only tolerated, but deemed of little account in man." Stanton and Mott's Declaration of Principles would be a battle cry against a society which aimed to "destroy [a woman's] confidence in her own powers, to lessen her self-respect, and to make her willing to lead a dependent and abject life." Their Declaration called for universal suffrage, and vowed to use the power of the press, of protest, of the pulpit, and of petition, to obtain the "immediate admission to all rights and privileges which belong to [women] as citizens of the United States."

Stanton was tasked with creating the final draft of the Declaration in the days before the convention. Henry Stanton, however, was less than enthusiastic; threatening to abandon his home if the clause calling for votes for women was presented to the convention - a threat he made good on. Yet, despite Henry Stanton's hostility, and a worry by Mott that turnout would be low, the convention opened on July 19th to a packed church sanctuary. In total more than 300 women and men crowded into the pews; among them Frederick Douglas, former slave and abolitionist, who lent his considerable weight to the equal rights cause; "Right is of no sex, truth is of no color," being one of his most firmly held beliefs. Although Mott would be the convention's keynote speaker, it was Stanton, delivering her first public address and playing a prominent role in leading the convention, who would emerge as one of the movement's national figures. The clause calling for women's suffrage was passed, though not unanimously as had every other; and in the end the Declaration of Sentiment was adopted and signed by 68 women and 32 men.

The convention's proceedings and aims were publicized by Douglas, who used his printing press at the office of his paper, the North Star, to issue a report on the meeting. News of the Declaration's adoption would be derided in the popular press; but its force and implications began to galvanize a growing women's equality movement. Over the following years Stanton began a partnership with Susan B. Anthony, organized subsequent conventions across the northeast, and wrote articles on temperance, divorce, and the legal obstacles to women's rights and equality. During the Civil War, in 1863, Mott, Stanton and others petitioned for the immediate passage of the 13th Amendment which abolished slavery, and suspended the annual meetings of their convention in deference to the war effort. When the battlefields had cleared and the war ended, Stanton, Anthony, and others created the first national women's rights organization the American Equal Rights Association; hoping that in the new political climate of racial equality, rights and suffrage would also be extended to women. The passage of the 15th Amendment in 1865 dashed any such hopes, eliminating voting restrictions due to race, but not sex. Undeterred, Stanton and her organization pushed for voting rights on the national level, and when, in 1878 an Amendment was put before Congress, Stanton was there to testify on its behalf. Again she was met with opposition. The Declaration of Principles, it seemed, was destined to fight a longer war than the Declaration of Independence.

On the state level, the Equal Rights Association appeared to have equality only in their inability to amend state constitutions. 480 campaigns were launched between 1870 and 1910 in 33 states; the results of which were a mere 17 referendums put before voters. Only two, Idaho and Colorado, achieved their objective. Colorado's adoption was a significant victory. There male voters, for the first time in the nation's history, voted in favor of enfranchising women. Slowly but surely, the cause was achieving victories, no matter how small they may have been. Further ballot initiatives achieved success, while the new states of Wyoming and Utah were admitted to the Union with universal suffrage as part of their constitutions. The goal of a Constitutional Amendment, and the attainment of one of the Declaration of Principle's core objectives, however, remained elusive. The Women's Suffrage Amendment was proposed every year following 1878; but for more than a decade following 1893 it failed to receive a favorable report in Congressional committee. Year after year Stanton and other Equal Right's leaders would testify before the House and the Senate, pushing and campaigning for the Amendment's adoption. Victory would finally be achieved on August 18, 1920 with the ratification of the 19th Amendment, which stated that the "right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex." It was a victory that only one of the signers of the Declaration of Principles would live to see. Stanton died in 1902 in New York City, Mott 22 years earlier in 1880; but one woman, Charlotte Woodward, who had heard the revolutionary call of 1848 and had, as a nineteen year old, attended the very first Women's Rights Convention, cast her vote in the presidential election of 1920.

Suffrage however, was only a part of the Declaration's list of goals. Struggle to attain full equality under the law, of compensation, and of access to education and resources continues even to this day. It is tempting to view the nomination of Hillary Clinton for the presidential office by a major political party as the penultimate crack in the "glass ceiling", and certainly Stanton and Mott would have been proud to see a world in which women had no say in the government which presided over them transformed into a world in which a woman's voice lead the way, but the true promise of their vision has yet to be fully realized. Unlike the European revolutionaries of 1848 who were eventually subdued by a return to monarchy and arbitrary rule, Stanton, Mott, and the other leaders of the Equal Rights movement did not abandon the fight; making good on their battle cry's final impetus to carry the struggle to every corner of the nation. Their unyielding fight for equality reminds us that progress is not demarcated by a single accomplishment, beyond which vigilance may be relinquished. Rather, only through constant pressure, toil, and dedication, can progress be achieved and maintained.

______________________________________________________________________

Notes:

The Revolutions of 1848. Encyclopedia Britannica Online. https://www.britannica.com/event/Revolutions-of-1848

Flexner, Eleanor. Century of Struggle: The Women's Rights Movement in the United States. Atheneum. New York. 1973.

Declaration of Sentiments. 1848. https://www.nwhm.org/online-exhibits/rightsforwomen/DeclarationofSentiments.html

Women's Rights National Historical Park. Essays on the Convention, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott, Frederick Douglas. https://www.nps.gov/wori/index.htm

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Matilda Joselyn Gage, eds., History of Woman Suffrage, Vol. 1 (New York: Fowler and Wells, 1881), 53-54, 61-62.

#history#american history#seneca falls#1848#elizabeth cady stanton#1848 revolution#lucretia mott#glass ceiling#hillary clinton#women's suffrage#suffragette#declaration of principles#voting rights#voting#19th amendment#votes for women#women's rights

0 notes

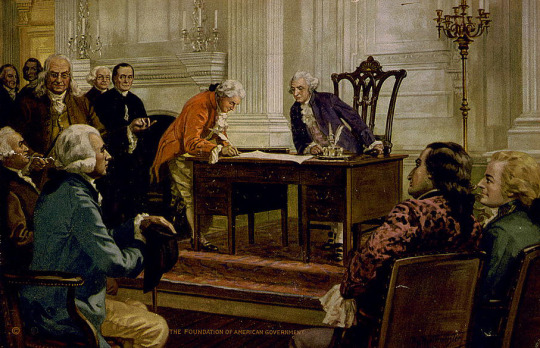

Photo

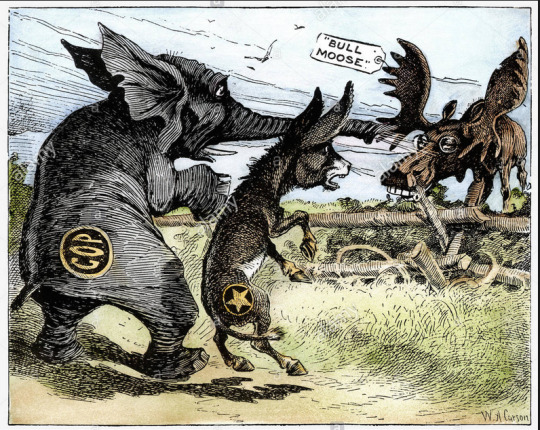

The Man of the People: Part VI - Trust Busting

By Scott Lipkowitz

History is usually considered to have two main purposes: to teach us how stuff works, and to teach us where we've come from. Over the past five posts I have attempted, through the use of snapshots of key moments in United States presidential history, to explain how the presidency was conceived, how election to the office was detailed, and how, in response to the different electoral crises these first two conditions created, national parties, conventions, primaries, and super-delegates came into being. Those first five posts have succeeded - I hope - in answering, however incompletely, the how and the where. Yet, there are several other purposes behind the study of history which are of equal relevance to the how and the where; one of the most important being history as natural experiment.

Now of course before we can apply any hypothesis or draw any conclusion from the preceding natural experiments, the limitations of what I have presented to you must be acknowledged. The political, economic, social, and cultural contexts are far more complex and nuanced, and the characters more interesting, more multi-dimensional, than any brief, blog-length description can do them credit. However, there are important observations which we can draw; and which might prove beneficial if we ever want to get off the merry-go-round we seem to be trapped on. Here then, heavily seasoned with my own opinions, are some questions we should be asking, and some outcomes we should be seeking.

First and foremost is the question of whether or not the President truly is, as John Dickinson wanted he or she to be, a "man of the people." I would argue that it is hard to answer that in the affirmative. Even from the start -whether it was for cynical reasons, or considerations of the technologically and geographically induced ignorance of the body politic - the average citizen's ability to sway the selection of the President was considerably small. Not only was the option of having their voices heard left up to the states to decide; but much of the original intent of the electoral college was to remove the burden of choice from the citizenry almost entirely. Even where the citizenry could vote for electors, it was assumed that they were voting for knowledgeable men who could, from their better vantage point, make a well informed decision about who was fit to serve as chief executive on the behalf of the general population. The average citizen was expected to bow to the wisdom of more learned men.

Ultimately the founders opted for this seemingly convoluted system because, unlike our history textbooks make them out to be, they were humans, faced with real world problems. Ideology may have eventually underpinned the Revolution; but pragmatism, and a sober reflection of both the internal and external situation drove the creation of the federal government, and shaped the presidency and its selection process. Article II and the Electoral College were part of a plan that was born out of the political climate of the late 18th century; but, as World War I German general Helmut von Moltke once said, "no plan survives first contact with the enemy." The enemy in this case was the actual implementation of Article II and its provisions. As we have discussed at length, everything that followed was the result of political problem solving by humans bent on maintaining, securing, or acquiring the power of the presidential office; all because the original plan did not stand up to political, and human realities.

What then does this tell us about humans seeking power in a republic? One conclusion to draw is that those seeking power will try to find whatever means necessary to obtain it; highlighting the rule of the people or discarding it as the current political moment necessitates. As we have seen, popular movements for increased citizen participation in the selection of presidential candidates were driven by the needs of individual politicians, or parties, to maintain or obtain the presidency; not out of some zeal for democratic values - despite what Theodore Roosevelt and others might have proclaimed in public. This does not mean, however, that there is some vast political conspiracy to tell the public one thing while doing the complete opposite. All of us look out for our own interests, and take actions, whether consciously or not, to further those interests; it makes no difference if we are a farmer, baker, operative of a political party, or presidential candidate.

Once we begin to take on board the fact that the problems of our presidential nominating process - like all of our problems really - are the result of the way in which humans respond to varying situations and problems, we might be able to tailor our institutions to control for the more negative consequences. The founders were intimately concerned with this fact, the entire Constitution is a compromise aimed at maintaining stability in the face of human foibles and conflicts of interest; and while they tried to build a system to contain the influences of factions, collusion, and patronage, they were realistic in their acknowledgment that they probably would not be able to predict every possible dire consequence of their actions. This why, in Article V of the Constitution, a system for making changes to, or amending, the Constitution was built in.

Aside from explicitly prohibiting any Amendment from removing the equality of Senatorial representation from any state, Article V does not limit what Amendments or changes may be made. In the aftermath of the first real presidential election crisis of 1800, the Twelfth Amendment was adopted in an attempt to remedy the unforeseen problem resulting from an unclear delineation between presidential and vice-presidential candidates. A total of 27 Amendments have been implemented - the most recent in 1992 - of which several deal with the presidency. None, however, deal with the mode of presidential nomination. If we, the public, so desired, we could push for changes to the Constitution that would, unlike internal party rules, be legally binding, and which might place the presidential nominating process once and for all in the hands of the general public. Of course there is one extreme speed break on constitutional reform: the two major political parties.

Founders such as Madison and Hamilton may have been kept awake at night by the destructive potential and horrific inevitability of factions, but it seemed that only Eldridge Gerry, out of all the assembled delegates to the Constitutional Convention, was able to foresee the terrible potential for national political organizations to game, and then control, the system. As we have seen, the major parties became the political equivalent of the late 19th and early 20th century monopolies which the progressive era tried to unravel. What Gerry correctly saw as their ultimate insidious advantage was their ability to create a broad loyalty that transcended the common good while at the same time positioning themselves as the ultimate protectors of the common welfare. The fact that today, when asked about voting for a third party, most voters will either say that they can not because it is not legal (false) or, more likely, that they would be "throwing their vote away," is evidence of just how thorough the two political parties have ingrained the aforementioned idea into our minds. While the parties are not the government, in that they are not required by its founding documents, they have managed to place a stranglehold on its levers and institutions; including at the state level, where any hope of reforming the presidential primary system would have to gain traction.

This is why any notion that holding open primaries - where all eligible voters, and not just those affiliated with a political party, may vote in a primary - is not a viable solution. Democrats and Republicans control the state legislatures who help craft primary election laws, and like any good monopoly, they're not interested in relinquishing their control of the market. Every step they have taken has been out of political necessity, not ideology, and even if every state held an open primary, tools such as super delegates would continue to be implemented in novel ways in order to ensure that the party's prime objective, winning, is not overshadowed by the "will of the people." Again, not a conspiracy, simply they way in which humans react to obstacles in their path.

A potential beneficial lesson we might draw then, would be to support a diversity of political parties and opinions so that no one or two parties could monopolize the system. Just as Standard Oil and U.S. Steel were broken up, and occasional monopoly suits are brought against the likes of Apple or Microsoft, so too do the political parties need to be exposed to the competition of the free-market. After all, what is more American than that? We would riot if we only had a choice of two breakfast cereals, why then are we content with only two choices for president? Voting for the 3rd, 4th, 5th parties, etc. will not end the problem of machine politics - every party will inevitably have a centralized machine structure - but it would force them to compete on the open market of political ideas; and if one of those ideas was the adoption of a Constitutional amendment to overhaul the primary and convention systems so that no party machinery could outweigh the voice of the individual citizen, then it might stand a decent chance of sneaking past the gatekeepers.

Finally, there is one last issue with our presidential nominating system that has less to do with the political parties, primaries, or super delegates, and more to do with the fact that the way in which we view the presidency and its role has dramatically changed since George Washington first took the oath of office in 1789. Initially intended to simply be the long arm of Congressional will, the modern presidency looks more like an elected monarch with a parliament waiting to give or deny its consent. We now look to the President, and not, as the framers initially intended, to Congress for domestic and international leadership. Of course this may be the legacy of thousands of years of monarchical rule, that members of complex human societies inevitably drift towards the guiding hand of a single powerful individual; but it might also be symptomatic of a deeper problem. Life is complex and the issues which face us are no less complicated that they were thousands of years ago. It may be no wonder then that we yearn for a strong man or woman who will remove from us the burden of having to grapple with these issues. Modern Americans seem prone to this sort of thinking - from weight loss pills to solving every economic hardship through tax cuts - and perhaps the growth of the elected monarch that is the presidency is to be expected. Certainly some founders, Benjamin Franklin being one of them, believed it would be the nation's ultimate destiny. Allowing this sort of thinking to continue however, is to abdicate our responsibilities as citizens living under a participatory government.

The preamble of the Constitution describes its intent as the formation of a "more perfect union." This is what, as a nation, we have been striving for since inception, and must continue to do so now. Humans have achieved a dominance on this planet because we are generalists, adapting whatever tools we have at hand to serve whatever problem or situation we find ourselves in. The Constitution is merely a political tool, and while some of its adaptations and offshoot inventions have not always worked for the common benefit, that does not mean that it can not be made to do so in the future. Baron de Montesquieu, the French philosopher of the 18th century, whose work The Spirit of the Laws heavily influenced the framers of the Constitution, believed that there was no "right" answer to government, that each form of government and its laws should be "adapted 'to the people for whom they are framed.'" The current presidential primary and election cycle has brought this issue to the fore. Our institutions may no longer be adapted to the people over which they rule. Armed with the knowledge of the history of their creation, perhaps it is time to actively alter and change them. Perhaps it is time for the innovations of political machines to be undone by the innovations of the citizens of this republic.

_______________________________________________________________________

Notes:

The United States Constitution.1787. https://www.billofrightsinstitute.org/founding-documents/constitution/

Berkin, Carol. A Brilliant Solution (Inventing the American Constitution). Mariner Books. 2002.

Bok, Hilary, "Baron de Montesquieu, Charles-Louis de Secondat", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2014 Edition), Edward N. Zalta

#history#american history#2016 United States Presidential Election#montesquieu#republic#presidential primaries#U.S. Constitution#amendments#u.s. president

0 notes

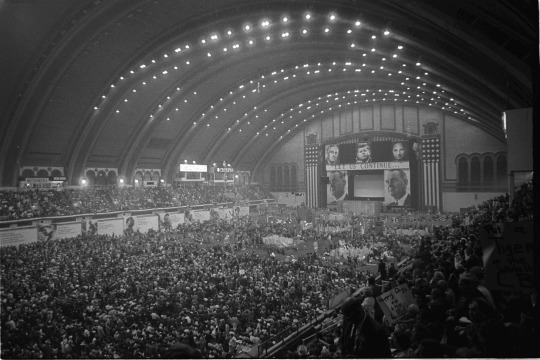

Photo

The Man of the People: Part V - Super Delegates

by Scott Lipkowitz

In his book Collapse, Jared Diamond points out that for every beneficial advance in technology there are accompanying negative side effects, many of which are unanticipated. Cars are a great example. So is the internet. Blow-back from novel inventions is not limited to the realm of technology, however. Cultural, economic, and political innovations also carry the same potential for negative consequences as do Toyotas and Facebook. This fact is writ large across the entire history of presidential creation, selection, and election.

Right from the start, the founders attempted to anticipate every pitfall, every problematic avenue that could arise from the establishment of an independent executive. They came up with a solution, and that solution, given time and the inconsistencies and ambitions of human beings, created further problems. Those problems - of Congressional deal-making, bickering, and animosity - lead to further solutions - the national party system and party conventions - which in turn created new problems - the control of candidate selection by party bosses, to the exclusion of the average citizen. Beginning in 1900 the pendulum would once again swing toward a solution to this newest of problems: the preferential primary. However, zeal for the preferential primary began to wane in the aftermath of Theodore Roosevelt's defeat in 1912. The Great Depression and the U.S. involvement in two world wars helped to further draw attention away from the preferential primary; and thus, by mid-century, the tally of states allowing party voters to directly influence the selection of delegates to the presidential nominating conventions was barely into double digits: a mere 17 out of 50 by 1968.

That year, it would be the turn of the Democrats to experience major internal convulsions. Lyndon Johnson, after assuming the presidency in the aftermath of John F. Kennedy's assassination in 1963, won re-election the following year by the largest popular vote margin in United States history; eclipsing Franklin Delano Roosevelt's previous landslide record in the election of 1936. That popularity would prove short-lived however. Johnson had barely been sworn in, and his successful Civil Rights package enacted, when race riots that began in Los Angeles spread to other major cities. Compounding that volatility was Johnson's decision to double-down on a stalled military effort in Vietnam which had begun under Kennedy. Public disillusion with the ruling party, rancor over a deteriorating domestic security situation, resistance to military involvement in Vietnam, and the desire for a sweeping change to the entire system would ferment into outright opposition to Johnson and the Democrats by 1968.

Johnson appeared weak and out of touch with popular sentiment; and many of his Democratic colleagues smelled blood. Chief among them was Senator Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota. McCarthy declared his intent to challenge Johnson for the Democratic presidential nomination in November 1967; citing the administration's "evident intention to intensify the war in Vietnam" as his main reason for doing so. McCarthy's anti-war position was a popular one, and while he was narrowly defeated by Johnson in the New Hampshire primary, Johnson saw the writing on the wall. In the aftermath of Johnson's close shave, Robert F. Kennedy threw his hat into the ring, and the President, despairing of his ability to secure the nomination, announced that he would not seek re-election shortly thereafter. Yet, New Hampshire didn't have to be Johnson's death knell. The vast majority of the states still held closed door party caucuses and were controlled by Democratic party officials. Had he not contested any primary, the Democratic establishment would have returned to Johnson the nomination; despite McCarthy and Kennedy's popular support.

It was this exact strategy which Hubert Humphrey, Johnson's Vice President, now sought to implement. Humphrey differed very little from Johnson in terms of policy, but he was a party insider, and familiar with the operations of the national machine. A portion of the Democratic base may have been united in opposition to his policies; but Democratic bosses certainly were not. While McCarthy fought it out in the few preferential primaries with Robert F. Kennedy, Humphrey chose not to enter a single one; opting instead to hunt for delegates in the overwhelming majority of states where the rank and file were not given a say. Before the Democratic National Convention even convened, Humphrey had secured a majority of the delegates needed to win the nomination; and not a single Democratic rank and file vote had been cast for him. Numerous groups planned to protest outside the Convention and to contest its proceedings from within. Clashes between protestors - angry at the possibility of continuing the status quo with a Humphrey nomination - and police were broadcast on live television. Inside the hall, a bitter debate over Vietnam policy raged. Everywhere, the image of a Democratic Party hopelessly battling itself, divided, and confused, contrasted with the relative ease with which the Republicans had solidified their support for Richard Nixon.

Blood, sweat, and brick-bats, however, would not be enough to deter the party establishment. Just as in 1912, the operation of the machine proved hard to overcome. Nixon began to position himself as a "law and order" candidate; one who could both quell the domestic unrest and deliver results in Vietnam. No matter what a bunch of "peaceniks" may have desired, Eugene McCarthy, in the eyes of the party establishment, did not seem capable of returning the Democrats to power against such an adversary. Winning, and not popular will, was, again, the prime objective. In the end the Democrats endorsed a platform of continued military operations in Vietnam and Hubert Humphrey as their standard bearer. For Haynes Johnson, political commentator and author, the 1968 Democratic Convention was a "lacerating event...[eclipsing] any other such convention in American history, destroying faith in politicians, in the political system, in the country and in its institutions. No one who was there, or who watched it on television, could escape the memory of what took place before their eyes."

Had any of those who were watching been even somewhat familiar with the history of presidential nominations from 1832 on, they might not have been so shocked by the 1968 Democratic Convention results. Party bosses had once again succeeded in thwarting the perceived will of the people, as they had been doing for well over a century. Yet, that sense of dire hopelessness so evident in Haynes Johnson's description of what happened did cause some of the political elite to sit up and take notice; especially once Humphrey had been defeated by Nixon. Nixon had not defeated Humphrey by a large margin, at least in the popular vote; but to Democratic leadership the lesson was clear: blatantly ignoring the popular will, small as it may have been, might have been an underlying cause of Humphrey's defeat. The long floor fight and televised violence on the Chicago streets certainly added to public dissatisfaction with the Democrats, and so, responding to the political pendulum swing, new party rules were adopted for the election cycle of 1972.

Following rule changes implemented by the McGovern/Fraser committee, two-thirds of the delegates to the Democratic National Convention were chosen through preferential primaries held in 23 states. This time, a popularly selected nominee, George McGovern - the same McGovern who chaired the rule changing committee - would run against Nixon; but, despite the increase in rank and file input into his selection, McGovern too would come up short in the November election. Yet, this did not slow the pace of primary adoption. During the following election, in 1976, more than thirty states held primaries, and Jimmy Carter, another popularly supported candidate received the Democratic nomination. The power of party bosses seemed to have been negated; but looks may be deceiving. The McGovern/Fraser committee had changed the Democratic Party Rules; but that does not mean that they changed any laws. This is because, where internal party decisions are concerned, for all intents and purposes, there are no federal laws or statues governing what they can or cannot do. If we return to our corporate structure analogy from the previous post, changing the rules to allow for more delegate selection through primaries is essentially Apple asking consumers to take a survey on what features the new iPhone should have, and then implementing the most popular choices. Apple doesn't need to hold such a survey, but they can if they want to, and they can just ask quickly go back to the non-survey mode of iPhone creation whenever they so choose. The parties can change their internal rules whenever they like, and to suit whatever purpose the party functionaries so desire. Just take the decision of Colorado Republicans to not hold a primary this year, as further evidence of this fact.

The McGovern/Fraser reforms were the response to a political problem, and they created, as one would expect, yet another political problem: McGovern and Carter didn't win in the general elections. Yes, Carter defeated Gerald Ford in 1976; but Ford was tarnished by Nixon's criminal activity, and was never perceived as a strong President. When the Republican's fired back in the 1980 election with Ronald Reagan, Carter - who, for various complex reasons we won't get into here, was painted as being soft and un-American - suffered a crushing defeat, both popularly and electorally. Reducing the influence of party bosses clearly did not work for the Democrats; and like any good corporation facing a loss in market share, they decided that a new rule change was needed to allow them to, in the words of Governor James B. Hunt Jr. of North Carolina, get back to "the business of winning again." Thus, the Hunt Commission - chaired by the very frank Governor Hunt - convened in the aftermath of the 1980 Democratic electoral flop, to rewrite the McGovern/Fraser reforms, and place the interests of the party back on top.

Enter the much despised super-delegates. Testifying before the Hunt Commission, Congressman Gillis Long, chairman of the House Democratic Caucus, asked that 2/3 of the House Democratic membership be sent as unpledged delegates to the 1984 nominating convention, because, as Gillis put it, the Democratic leadership were the "last vestige of of Democratic Control at the national level." Gillis believed that as party officials, the House members had a "special responsibility to develop new innovative approaches to respond to our Party's constituencies." In other words, the party bosses had a responsibility to ensure the party had as a good a chance as possible of winning. The party's "constituencies" he refers to are not "we the people"; but rather party members eager to maintain their positions of power and the legions of outside interests dependent upon that continuation of power. Governor Hunt was inclined to agree with Gillis' assessment, stating, "We must also give our convention more flexibility to respond to changing circumstances and, in cases where the voters’ mandate is less than clear, to make a reasoned choice ... [an] important step would be to permit a substantial number of party leader and elected official delegates to be selected without requiring a prior declaration of preference. We would then return a measure of decision-making power and discretion to the organized party and increase the incentive it has to offer elected officials for serious involvement.” "Without requiring a prior declaration of preference" means a delegate who can declare for any candidate without being bound by the will of party voters - a "super-delegate."

One of those outside interests keen to see a continuation of Democratic power was the AFL-CIO, which joined with Hunt and the Democratic State Chairs' Association, to call for 30% of the 1984 convention delegates to be composed of these super delegates, chosen from the party's establishment members. Though this proposal had wide support initially, objections were made - but not out of any appeal to democratic principles one might expect - and ultimately, under the Ferraro Proposal, put forth by Congresswoman Geraldine Ferraro, the total number of super delegates selected by the party was set at 14%; where it still roughly rests today.

This years' primaries, especially the Democratic contests between Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders, brought the issue of super-delegates to national attention; creating a deep sense of outrage among the voting public; especially when it seemed as though unelected delegates would decide the nomination in favor of a party stalwart over a popularly supported opposition candidate. However, those paying attention to history, and viewing the parties as what they really are - corporations whose product is the running of government - were not so shocked by this apparently sudden revelation. Super delegates are nothing more than a pendulum swing back toward the rule of party bosses that dominated the nomination process from 1832 until the 1970's. They are not new; nor are they some violation of the law, because, as we have repeated over and over again, the party's are not the government and thus are not bound by the Constitution or its amendments. Everything the parties have done, from their very institution as national organizations to their implementation of super-delegates as a means of reasserting their control has been done to solve political problems, some of them arising directly from the vacillating opinions and allegiances of the general voting public. Yet, no matter what the underlying cause of these novel political inventions, their end goal is always the same: to win, to maintain the hold on power.

In an article from 2008, entitled A Brief History of Super Delegates, the Daily Kos argues that in reality super delegates are beneficial to the nominating process, in that they actually serve to uphold democracy, while at the same time protecting the interests of the party. This may be so; but only when upholding democracy and the interests of the party happen to dovetail perfectly. As we have seen, whenever these two competing needs have come into conflict, the parties will change whatever rules they have to in order to ensure that the latter concern is always secured; even if it means jettisoning the former. Public anger at the super delegate revelation may provoke a change in direction, in much the same way that 1968 and 1980 produced procedural shifts; but whatever solution the parties employ will undoubtedly spawn unforeseen political problems at some point in the future, which, in turn, will lead to more novel solutions, and on, and on. Of course understanding this reality and its quintessentially human causes is only helpful if we learn from it; if we take the lessons of history and try to apply them to the here and now. We'll attempt to do just that in the sixth and final part of The Man of the People.

_______________________________________________________________________

Notes:

Diamond, Jared. 2011. Collapse. Revised Edition. Penguin Books.