#wilhelm wichtendahl

Text

Courtyard of the Gartner House (1961) in Gundelfingen, Germany, by Wilhelm Wichtendahl

#1960s#house#bungalow#architecture#germany#nachkriegsarchitektur#nachkriegsmoderne#architektur#wilhelm wichtendahl

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

Office and Commercial Building of Nürnberger Lebensversicherung (1959-60) in Ausgburg, Germany, by Wilhelm Wichtendahl

#1950s#office building#concrete#architecture#germany#nachkriegsarchitektur#nachkriegsmoderne#architektur#ausgburg#wilhelm wichtendahl

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

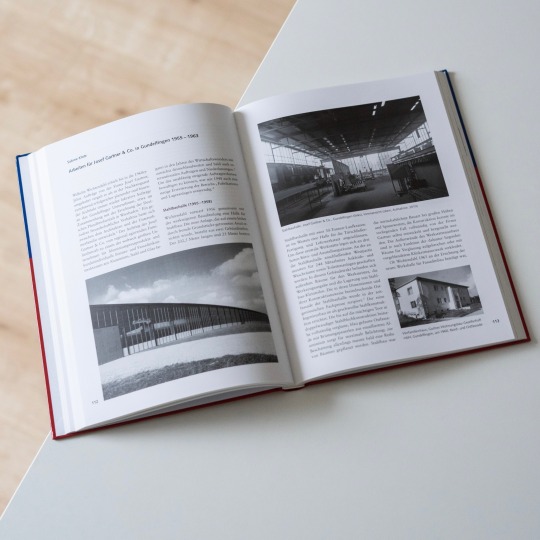

The biography of German architect Wilhelm Wichtendahl (1902-92) reads like many of his contemporaries’: Wichtendahl studied at TH München, after graduating worked in Robert Vorhoelzer’s progressive Postbauschule and during the Nazi era served as company architect for M.A.N. and Messerschmitt. His career is paradigmatic insofar as he spent the Nazi years in the alleged refuge of industrial architecture, a niche in which the authorities accepted modern architecture. After the war and with the excuse of having built for corporations rather than Nazi institutions Wichtendahl was seamlessly able to continue his career and significantly contributed to the reconstruction of the city of Augsburg. From 1952 onwards he also rose in the ranks of the Bund Deutscher Architekten (BDA), the leading association of German architects, and between 1959 and 1965 served as its president. In these capacities Wichtendahl also played a part in spreading the myth of industrial architecture as a refuge where progressive architects met and I deology played a minor role. Of course this was merely a maneuver to exculpate himself and his colleagues.

As keeper of the architect’s archive the now closed Architekturmuseum Schwaben in 2011 dedicated an exhibition and a catalogue to Wichtendahl’s conflicting work and biography: „Wilhelm Wichtendahl 1902–1992. Architekt der Post, der Rüstung und des Wiederaufbaus“, edited by Winfried Nerdinger and published by Reimer Verlag, critically evaluates and contextualizes the architect and his architecture, also beyond his role within the Third Reich and his association’s activities. Wichtendahl undoubtedely was a successful architect, especially in the fields of hospital and school architecture, whose plannings grew in size alongside the postwar economy. From the work catalogue nonetheless emerges the picture of an architect who, as Winfried Nerdinger notes in his foreword, never quite developed an individual handwriting.

The present volume is an important contribution to the exploration of German postwar architecture, the continuities between the latter and the Third Reich as well as their manifestation in individual biographies. Highly recommended!

#wilhelm wichtendahl#monograph#architecture#germany#nachkriegsmoderne#nachkriegsarchitektur#architecture book#german architecture#book#reimer verlag

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Deutsche Pfandbriefanstalt (1954-56) in Wiesbaden, Germany, by Wilhelm Wichtendahl & Alexander von Branca

#1950s#administration#concrete#relief#architecture#germany#nachkriegsmoderne#nachkriegsarchitektur#architektur#wiesbaden#wilhelm wichtendahl#alexander von branca

67 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Any discussion of German postwar modern architecture would be incomplete without mentioning Bernhard Hermkes, architect of the audimax of Hamburg University, planner of the Ernst-Reuter-Platz in Berlin and, as the present monograph reveals, designer of a number of lesser-known but equally interesting projects: with "Bernhard Hermkes - Die Konstruktion der Form", published in 2018 by Dölling und Galitz Verlag, Giacomo Calandra di Roccolino provided the first all-encompassing analysis of Hermkes' work, from his student years in Hamburg, Munich and Stuttgart to his late work again in Hamburg. This chronological work analysis also includes Hermkes’s work during the Third Reich: following a number of unsuccessful competition participations Hermkes in 1935 gave up his independent practice in order to work as employed architect and later on worked under Herbert Rimpl and Wilhelm Wichtendahl on industrial complexes for the national socialist industry. After the war and alongside the revitalized German economy Hermkes saw his again independent practice flourish: besides the previously mentioned landmark projects the architect, as the book’s author reveals, also worked on a number of smaller projects that Roccolino presents with deservedly equal attention, e.g. Hermkes’s own house in Hamburg that he designed with almost obsessive attention to every detail. This attention to detail also is what characterizes the book: together with the huge amount of archival material included Roccolino provides an all-encompassing account of Bernhard Hermkes‘s life and career that despite in-depth analyses leaves room for the reader‘s own reflections and opinion making. Well done!

#bernhard hermkes#monograph#architecture#germany#german architecture#architecture book#book#nachkriegsarchitektur#nachkriegsmoderne#art history

32 notes

·

View notes