#which only ties it further to the contemporary imagination and makes it an even more interesting record of our ideas about the world

Text

The only mildly unfunny thing about the Button House Archives is that I'm too much of a nerd to see the humour in some of the jokes. When I read Fanny's menu I'm not sniggering at all the weird dishes, I instead get really excited and bring up Firefox to search which ones are historical and which are made up, while imagining what people might have found appealing about those tastes and textures. People used to do things weirdly in the past; isn't this so antiquated and funny-haha? No actually, I'm very busy enjoying thinking about how those things would construct an alternative cultural and societal context in which these wacky things actually make total sense and how our own rules nowadays are equally arbitrary, but because we get to experience them for ourselves and see how they all fit together and support each other this feels like the only "natural" way to do things, the only way that "makes sense" (same as their own ways seemed for the people in the past), which unfortunately limits all of our understandings of what it means to be human.

I very much do still enjoy reading those bits though, only in a more absorbed than amused way. Popular humour is such a window into the mental landscape of a society, and this book is a treasure trove of ideas. I love it!

#with obvious caveats that this book is based on pop-history tropes rather than factual historical representations#which only ties it further to the contemporary imagination and makes it an even more interesting record of our ideas about the world#who's writing the cultural analysis paper on this? I'm eager to read it#bbc ghosts#the button house archives#button house archives#maddie's ghosts tag

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

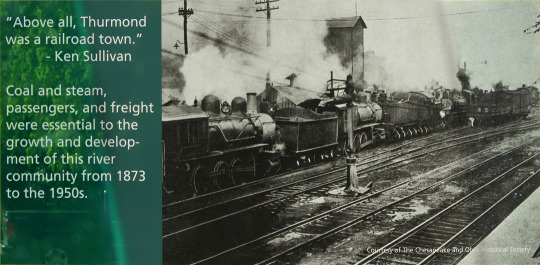

Thurmond, West Virginia: a Rail Road Town that the World Passed By, Then Found Again (sorta’) - Updated.

As I explained recently over a dinner with friends in town (for the first time in how long?!), Thurmond, West Virginia was south and west of Pittsburgh, so it seemed like a good option for a kind-of side trip on the way home from Pennsylvania. Little did I know how long the trip south would be, but glad I was to have done it.

A CSX coal car drag passing the Thurmond Depot, as seen through the window of the yardmaster’s office. [1]

The town was founded by one Capt. W.D. Thurmond in 1873, the same year the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway completed main line track building through the New River Valley. The New River Valley was scene to intensive coal mining in the latter half of the 1800s and first half of the 1900s, and Thurmond was literally and figuratively at the heart of it all.

I believe the tall structure visible through the coal smoke and vented steam is the coaling tower. [2]

Thurmond in 1988. Conspicuously absent now are all the structures on the left side of the tracks -- as well as the tracks to the left. [3]

The New River Valley was also the scene of some of the worst of the “coal field wars:” the operators paid by weight, ran company towns and stores, and lured unsuspecting laborers into the valley with promises of good wages -- promises that never materialized. Instead, coal weight was shorted, company rents and store fees were exorbitant, and rules were enforced with extra-judicial posses, bought-off law enforcement officers, and state militia at times. Miners were repeatedly denied recognition of their unionizing efforts, scabs were thrown in between the simmering, or boiling, antagonists, and strikes devolved into shooting matches.

Thurmond in 1988. [3] Two generations of water towers (near center) holding hundreds of thousands of gallons of water for the thirsty steam-powered engines, and the post office building (at right) CSX removed the water towers in the 1990s.

Concrete footings for the water towers seen in the 1988 photo above. The post office building still stands (at far right), and is still U.S.P.S. property, though it is no longer in operation. [1]

Thurmond was the vital hub for the C&O and for all the various people who moved through the Valley throughout the coal mining years; in 1910, Thurmond moved more freight and passengers than any other town the rail road serviced. It’s hard to imagine today, but from its founding until the early 1920s, Thurmond could only be reached by rail, and thousands of people moved through or lived in the town, going to work in a mine, working for the C&O, or providing goods and services.

The Marilyn Brown house, with the roofline of the Fatty Lipscomb house beyond. [1]

At one time, Thurmond boasted many commercial structures, scores of houses (like those above), and was also a service hub for the C&O’s engines and rolling stock. Steam-powered rail road engines require daily maintenance, work that was effected in a large engine house that was perched above the river.

Thurmond in 1988. [3] The engine house is right of center in the mid-ground, behind the trees. Some of the remaining private houses can be seen uphill behind the commercial buildings, as well as the one “street” that wound across the face of the hill.

Like so many towns built around 19th century industries, Thurmond’s importance declined dramatically as the 20th century proceeded. The use of diesel rail road engines left steam engine mechanics unemployed; many of the mines played out, and those that remained (and remain still) employed far fewer miners to pull the coal from the seams -- or blast it from hill tops; and people who would have been passengers on the trains began driving automobiles. The world, if you will, moved on, and Thurmond dried up.

Two views of the Fatty Lipscomb house. [1]

As coal mining declined, though, tourism increased, and in the 1960s and 1970s, enthusiasts of outdoor sports found the U.S. Congress receptive to the idea of setting aside some of West Virginia’s landscapes for boating, hiking and camping. In 1978, a substantial swath of West Virginia was designated as the New River Gorge National River, and later, lands along the Gauley and Bluestone Rivers were conserved, designated as National Recreation Areas in 1988.

Another house, here perched on the hillside above the commercial district, and a stretch of the local roadway, looking downhill. [1]

Once the land along the rivers became national reserves, Thurmond basically passed into federal control, though up until the early 1990s, up to 50 people still resided there. The Chesapeake & Ohio had also declined, and became a foundational holding of today’s CSX Transportation rail road company. CSX still moves coal through Thurmond in long drags of hopper cars, either full and destined for power plants, or empty and heading back to the mines.

In 1988 (above) [3] and in 2021 (below). [1] The view below is perhaps the best known angle of the old commercial buildings. From right, these are: the Mankin-Cox Building, the oldest of the three, which housed a druggist and a bank; the Goodman-Kincaid Building, which housed a dry goods store as well as offices and apartments; and the National Bank of Thurmond Building; all held a variety of business concerns before business fled. To the upper right is the Erskine Pugh house. The track in the foreground has been removed.

Circa 1900 [2] The engine house is right of center, with the commercial buildings to the left. The large building at far left was a hotel, but it burned down and was replaced by an Armour meat company building -- which also burned, in 1963 . The depot (seen following photo) is at the far right, with the rail road trestle just in view.

The 1904 passenger depot, now the NPS visitors center (as of 1995), and yes, Amtrak does have Thurmond as a stop! [1]

The NPS owns most of the remaining buildings, and efforts began in the early 2000s to keep them from deteriorating further, with roof repairs and seals to keep out the weather. There are still 5 residents in Thurmond, all are on the town council, and in addition to being active within the park, they are also seeking ways to keep the town alive.

The red house at left is new construction, but on an old foundation, and where possible, older building materials have been recycled in its build-out. A project of Thurmond’s residents, the hope is to have it available for seasonal leases; my guess is it’ll wind up with a long wait-list -- and my name will be on it! [1]

Old rail road ties in the dirt: now an access road, the C&O service track that led to the coaling tower were once mounted here; the engine house would have been to the extreme right and partially out of view; the depot is dead ahead, and my road-weary car is parked near the trees. [1]

Maybe I was taken-in by the town because of the setting, nestled as it is among the hills and above the river; maybe it’s because the old buildings have that “certain something” that makes history buffs like me snap more photos than is reasonable; maybe it’s the potential that I can see in them (provided anyone ever coughed up the money to really rehabilitate them); if I was to get metaphysical about it, maybe it’s because of all the lives and history that occurred in the area and the energy left behind calls out still (y’know if I got metaphysical about it -- past lives anyone?); perhaps it’s all of those. What-ever the reason, I’ve been thinking of making a trip back in mid-Autumn, take a long weekend as the leaves are turning and it’s got chilly -- and shoot yet more photos than is reasonable.

The 1922 coaling tower (above), built by Fairbanks Morse (as noted on the sign below). [1]

The reason for the coaling tower: a pair of the last steam engines in Thurmond: 1953. [2]

I briefly stopped at the New River Gorge visitors center where I got directions, and figured I could at least find out where I was going before getting off the highway for the night. I arrived in Thurmond just before 5 PM, but even that later afternoon hour left plenty of daylight to walk about and take photos. My thought had been to simply find Thurmond, then make my stop-over somewhere nearby (Beckley, WV is less than 10 miles away) then return in the morning. That thinking quickly became “Oh! I can come back for more in the morning!”

Up the hill: the old church. [1] The church grounds now host the local triathlon and reunion events for those who once lived in Thurmond.

What I realized as I strolled around in the afternoon, was that the light would be dramatically different if I arrived early the next day (yeah: a “well duh!” moment if ever there was one), an effect of the changed daylight hours mixed with the topography that proved itself quite wonderfully -- and is why the images here show both the golden glow of evening and the cool white of morning.

Amtrak’s Cardinal route-train, on-time (or nearly) on a Friday morning. [1]

Standing by my car, having a sip of coffee, looking around as other visitors arrived or departed, I just, well -- “sighed with contentment” is an apt description.

A view of the ticket agent’s office. [1]

For more information on Thurmond:

The National Park Service’s web page for Thurmond, WV.

Thurmond, WV on Clio, a history and culture website.

Both of these share some of the same information, and each has additional images, both historical and contemporary.

A view of the New River Valley from the west side, across from Thurmond (note the houses and rail road cars on the far bank below the hill). [4]

The historical narrative written here was gleaned from the NPS hand-out for Thurmond, as well as from the Summer 2021 issue of National Parks magazine, published by the National Parks Conservation Association (“Miner’s Angel” concerning Mother Jones and the coal field wars of West Virginia, by Nicolas Brulliard). Identification of the Marilyn Brown house made possible by access to a PDF of the NPS’ structural assessment report of buildings in Thurmond, revised edition, published in 2002.

A view of the yardmaster’s office [1]

Atlas Obscura’s “22 of America’s Best Preserved Ghost Towns” Sorry, Mental Floss, you were forgot.

Looking south toward the depot past the three old commercial blocks. [1]

[1] Photographs by R. Jake Wood, 2021.

[2] Historic photographs displayed on-site by National Park Service, photographed on-site and edited for this posting by Jake Wood.

[3] Photographs by Jet Lowe, 1988, for the Library of Congress’ Historic American Building Survey/Historic American Engineering Record; retrieved from the Library of Congress’ Prints & Photographs Online Catalog, with minor editing by Jake Wood.

[4] Photograph by the Detroit Publishing Co., circa 1910; from the Library of Congress’ Prints & Photographs Online Catalog, with minor editing by Jake Wood.

The depot, alongside CSX trackage. [1]

CSX coal drag outbound with hoppers full of coal. The post office building is visible just beyond the engine. [1]

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

this is like a month old but i thought i would post my final for my social sciences class bc i was rly proud of it! the full cover letter is under the read more but it’s really long so to summarize: it’s about how Mad Men used advertising as a shorthand for societal ideals of the family, and how Don Draper is consumed by those ideals over the course of the show

The original concept for this project was a triptych collage. I wanted a visual element because the ads on this show are so visual, and because I thought that it was the quickest way to connect three distinct moments together. There are three general columns, each with pictures from a different episode of Mad Men. First, from S1:E13: “The Wheel”, then S6E12: “In Care Of”, and finally S7E14: “Person to Person”. I wanted to pull out these three episodes as particularly memorable moments when the advertisement shown on the show is tied directly to the personal life of the main character, Don Draper. Then, within each column, there are three general rows. The top row shows three separate ads that are featured in the respective episodes. I highlighted the brand names in gold and obscured any faces shown in these pictures to highlight the power these brands have over the people creating or consuming them. Then, the second row is trying to highlight the general social fantasy that each ad is trying to sell. Finally, the bottom row shows the dissonance between that fantasy and Don’s actual reality. From left to right, there is Don sitting alone in his house, Don explaining how this product was “the only sweet thing in [his] life” because he had no paternal affection, and Don admitting that the façade he projects is not actually his true self. There are several quotes from Simone de Beauvoir’s Second Sex and from Karl Marx’s Capital that informed my thinking written in the blank spaces.

Marx said that “as soon as [an object] emerges as a commodity, it changes into a thing which transcends sensuousness” (Marx 163). Its monetary value was not tied to its physical form anymore, but represents an abstract buying power in the economy. He posited that this value’s power came from the labor expended by the producers of the product. In this project, I am trying to show that commodities and brands also gain an outsized importance by adopting societal fantasies and becoming myths. These myths act as translators for societal ideals to our own lives. Just like how Greek heroes taught the Greeks lessons about how they should and should not act, the American myth—advertisements—translate our social ideals to the people and help them integrate the general fantasy into their reality.

Viewing advertisements through this lens makes Mad Men’s general structure of showing how Don Draper and co. solves their personal problems by creating ads very transparent. Their ads are powerful because of this connection to their personal lives, because the connection to social reality is what makes advertising effective. Brands like Coca-Cola and Hershey’s are not synonymous with the perfect American life by chance. By focusing on the creators of ads rather than consumers, it is clear how their symbolism in the American consciousness was “elaborated like language, by the human reality” (Beauvoir 57). The meaning of these brands is created by someone’s reality, not an inherent fact of the universe. This is made explicit in Mad Men by focusing on the creators of these ads. Beauvoir said that “any myth implies a Subject who projects its hopes and fears” into the creation of the myth (Beauvoir 162). The creators of these ads have to buy into the American fantasy just as much as the consumer for an ad to be truly effective. Both creator and consumer are using these ads to bridge the gap between their own reality and the ideal they are told to emulate. Don Draper lives every day articulating these myths, and struggles with how his own reality consistently diverges from his ideal. Thus, he copes by utilizing pouring elements from his own life into his ads, and thus is able to live in the delusion that they are one and the same.

This coping mechanism is first shown explicitly in the left-most column, taken from S1E13: “The Wheel”. Don is literally projecting images of his family to sell this product. By using his family as the quintessential American family in this myth, he is able to trick himself that they are this way in reality. However, this is not a real solution to any of his problems. This is a film projector, not a time machine. The final image of the episode shows Don’s reality: that he is alone, estranged from his family, unable to connect. In mythologizing his own life, he does not solve any problems, but rather uses them as one of his “countless ruses rather than confront real-life obstacles that he fears may be insurmountable” (Beauvoir 53). It is important to note that Don, in his role as both creator and consumer of these ads, is not simply responding to the power that this product has over him. He is imbuing it with power as well. The Kodak carousel is a film projector, not a “time machine”, not a way to reconnect with family. But by giving the product such an outsized importance in his own life, Don has given it power, while simultaneously removing some of his own.

In the second set of images, from S6E12: “In Care Of”, I wanted to show how Don is not merely projecting images of his life onto these fantasies, but actively pouring real information into them, as a sort of offering. Don has shared his real past and identity with almost no one, and yet tells the Hershey’s executives a deeply personal memory, almost compulsively. He is not creating a myth for his reality, but describing his reality through myths that already existed. “Hershey’s is the currency of affection” is not an arbitrary slogan, but a reflection of Don’s own need for affection from his nonexistent mother. Even when he was a child, he already had the association of Hershey’s with the ideal family that he never had. This societal ideal is already attached to the brand and the product, which is why Don believes that Hershey’s has no need to advertise at all, since there is no need to tie the product further into fantasies. Just like in the Kodak pitch, Don is using his real life to define this ad. However, the bottom picture shows Don breaking down and the executives being unimpressed. In this case, the gap between his reality and social ideals is too great to be bridged by an ad, and so the ad is unsuccessful.

The final set of images, from S7E14: “Person to Person”, shows Don as he is finally separated from his life completely. The reason why he articulates his life through ads, and the reason why he runs to California, the representation of counter-culture, is because he is compelled to “search for himself in things, which is a way to flee from himself” (Beauvoir 57). Don makes sense of his reality by alienating himself from it. In the final scenes of the series, he is completely alone, however, listening to someone extoll the promise of “a new day, new ideas, a new you.” Again, the self is equated to a collection of ideas that can just change, rather than a continuous experience grounded in reality. The iconic 1971 Coke commercial then plays, in full. Regardless of whether Don the character created this ad, the tagline “It’s the Real Thing” combined with the counter-culture aesthetic of the ad clearly represents the new ideal that Don is striving for. To the viewer, this final image shows us that this seeming enlightenment is nothing more than a mirage. While Don continues to filter his life through myths, and to “prefer a foreign image to a spontaneous movement of one’s own existence, ... to play at being” (Beauvoir 60). He is not able to create a new self, because his current self is nothing more than a collection of “new ideas”. Don believes that he is able to create a new self by creating his environment or aesthetic because he has continually tied his life to images, rather than accepting his reality for what it is.

Of course, the ultimate commentary Mad Men offers is on the viewer. One has to ask why audiences continued to flock to a show that focused entirely on one man’s quest to escape reality into some mid-century fantasy of American life. The 1950s and 60s hold an incredible grip on the American imagination, as some bygone era when the United States was unquestionably on top. Mad Men seems to offer a refutation of that image, in even showing the fracturing to the American family and myriad of other social problems faced during that time. However, it may be “not the opposite” of that fantasy, “but rather [its] most recent and noble manifestation” (Nietzsche 112). Mad Men, showing how its characters fail to live up to these fantasies, actually reinforces them by constantly showing them as desirable, if unattainable. Contemporary America has projected its hopes and fears onto Mad Men in the same way its characters project onto their ads. We face a similar period of political and social upheaval. The information revolution of the television finds its counterpart in the internet, where advertising is absolutely unavoidable. Don Draper is not the protagonist of a nostalgia-fueled recap of America’s greatest hits, but a cautionary tale in what happens when one ignores reality in favor of adherence to social fantasies.

#lmao the cover letter is kind of a mess but! i really liked working on this project#studyblr#studyspo#mad men#don draper#study motivation#original

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Devotion Without Religion

Devotion to God has been at the figurative heart of man's religious and spiritual quest for millennia. Saints and texts alike have spoken of man's love for God, God's love for man, and the ecstasy that comes from realizing that love within oneself. But we live in a rational and secular age, and the path of devotion has been de-emphasized. When we admit to having spiritual urges at all, we often speak of the search for peace, with its main route being through meditation. When the emotions are engaged in the spiritual search, they are directed towards aims like self-actualization and healing. Actual devotion—the practice of love, worship, and prayer—is viewed as misguided at best, and dangerous at worst.

It is not at all clear how to reconcile the path of devotion with the independent spiritual path. This is because the way of devotion is associated with the worst aspects of religion, such as irrationalism and fanaticism. The argument goes that only a force like religious devotion is able to lead otherwise intelligent people to embrace the irrational aspects of religion, such as beliefs that contradict mainstream science, or partisanship that rejects or persecutes those who hold differing religious opinions. Therefore, for the modern reformer of spiritual seeking, devotion with its irrational emotional intensity is the force that must be excised when we go to recover what is good about spirituality.

But it's unfair to blame religious devotion for all the problems that the emotions bring to man. On one hand, emotional attachments can lead to fanaticism even without a religious component, as we see in the case of nationalist passion. And on the other hand, as we learn more about man's psychology, we see increasingly that emotional attachments are a key factor that keeps human life and society running. In his treatise The Origins of Political Order, Francis Fukuyama points to research that shows that man was always involved in social and political groupings held together by emotional ties and was never in a solitary state of nature. Modern psychology emphasizes the fact that human relationships are essential for mental health. Even in the hard-nosed field of business management, ever since the publication of In Search of Excellence by Thomas Peters and Robert Waterman, it has been acknowledged that emotional factors like pride in one's work and the joy of serving the customer, as opposed to the rational pursuit of wealth alone, are crucial for success in business.

Therefore, we can't rule out the engagement of the emotions in spirituality solely on the basis of the negative aspects of religion. And while it may seem easier to leave the emotions to the adjacent fields of mental health or business success coaching, the essential connection between engaging the emotions and the search for the Divine cannot be neglected indefinitely. Most people would never be able to undertake an endeavor as difficult as the search for the Divine, not even on the austere path of formless meditation, without a strong emotional connection to the path. And once we admit the possibility of engaging the emotions, we must also admit that deepening that emotional connection to God is one of the most accessible and powerful paths to God.

Devotion to Forms, Abstract and Concrete

The contemporary understanding of God does not allow us to easily see how to do this. Because of the aversion to the religious approach to God, which is caricatured as propitiating a stern old man in the sky, the contemporary tendencies are to either view God as a pure abstraction, a powerful deity but one who is ultimately unknowable in a human way, or otherwise to deny that there is a God in the sense of a conscious being, imagining only an abstract energy. If those two conceptions of God exhausted the reality of God, that still wouldn't necessarily mean that the path of devotion is impossible—after all, such abstractions as a flag, nation, or business organization are all able to command sustained emotional commitment and sacrifice. But it remains true that devotion to tangible forms is a powerful practice—the practice which gives religious devotion its power and which makes the modern spiritual reformer wary.

One interesting thing to note is that just because we find the approach of devotion to concrete forms problematic doesn't make those forms of God any less real. The modern reformer takes God to be an abstract energy because it would be distasteful to worship God in the specific form of Krishna or Christ; but if God really does take the form of Krishna or Christ, the opinions of the modern reformer wouldn't matter. Of course, the modern reformer would hold that there is no specific evidence for God having the form of Krishna or Christ either. Still, if we are open to the idea of devotion at all, we must hold out the possibility of the validity of the recognized forms of God; after all, any argument that discounts the God of specific religious forms could easily be modified to discount the formless and abstract God as well.

But whether we admit traditional forms of God or only abstract forms, the problem for those on the independent spiritual path remains as to how we are to pursue a path of devotion that avoids the trap of the religious approach of exclusivity, irrationalism, and fanaticism. It's hard to see what the options are, but if we are clear eyed we can see that there are only so many possibilities. One is to preserve the old gods of the religions, but to try our best not to get stuck in the religious traps. This approach would acknowledge that there is an unknowable mystique around the forms of God that have been handed down, and that it is not possibly to synthetically come up with a new form or abstraction which can command the same reverence or devotion. In this approach, the heart would be devoted to Christ or Krishna without participating in the other social and institutional structures of organized religion. The danger of this option is that it will slide too far to the faults of the old religious mentality. After all, if the revered forms of God are worth preserving because of their irreplaceable essence, why shouldn't the associated religious practices and social forms be viewed as similarly meritorious? It may not be clear how to extract devotion to these forms of God from concrete religious practice.

A second approach would be to channel devotion to human gurus. There are obvious problems are here as well, and they may even seem to be worse than the problems with the previous option. Namely, this option could lead to personality cults, which are regarded as the worse and more extreme than even religious institutions. If an individual human is loved and regarded as God, they may feel as though they are granted absolute power, which no human being should have. Further, it is not clear whether anyone currently existing on earth is worthy of being placed in this position. What makes this opportunity worth considering, though, is that the human guru provides a target for the devotional impulse that is tangible without relying only on the classical forms of the religions. And in an ideal world, there might be enough spiritual masters and gurus that would make this a legitimate outlet for the devotional impulses of the spiritual seekers.

A third approach would be to reserve the devotional impulse for the forms and institutions of human life as they are: the family, the nation, various secular and religious institutions. This approach would powerfully ground spiritual seeking in the structures of everyday life. The problem with this approach is that even though the human affections can work effectively through these human organizations, it is not clear if the highest form of religious devotion could flow through these mundane channels. A fourth option would be not to try to send the religious devotional impulse towards any forms or structures at all, and instead to focus on revering the abstract forms of God instead. This approach would seem to at least avoid the problems of the earlier methods in principle, though in practice one may wonder if the human heart could really love an abstraction. The modern reformer or critic may hold that any effectiveness of the concrete forms for devotion is still too big of a risk, and that man will have to learn to love the abstract. But it must be noted that even movements with aniconic policies or tendencies have had trouble with fanaticism.

It may seem like there are no good options for how to safely direct the devotional impulse: either there is the option of a cold abstraction that doesn't inspire devotion, or otherwise the problems that come with emotional attachments to people, forms, or institutions that are not fit to bear the pressure of being loved as God. But there is a subtle shift of framing we can use to open another option. In options one through four, we assumed that we were disconnected from God and needed to find the right way to connect with him; if we didn't find it, we might be disconnected forever. In this way of thinking, the old religions may have had a channel through their various forms, and if we can't use their channel as it was initially set up, we could lose access to God completely.

But we don't need to make that assumption. We can assume instead that we already have a relationship with God, and from there assume that we will be guided to the right devotional channels when the time is right. This is a fifth, all-encompassing option that gives us not a simple answer for how we should direct our devotional impulse but rather a way of living that will dynamically channel our devotion. The specific devotional forms may be different at different times; and they may include some of the options from above that may seem "dangerous" for their proximity to religious methods, such as the use of older religious forms of God, devotion to human spiritual teachers or institutions, or the sanctification of human relationships like the family, romantic love, or friendship. But as long as we keep in mind that our relationship with God is prior to any given form of him that we are devoted to, we will be relatively safe as we negotiate the shifting tendencies of devotional spiritual practice.

A Devotional Relationship to God

The possibility of a devotional practice in the contemporary era requires that we have a relationship with God that is prior to any specific form of God, and use that as a basis for devotional relationship to various forms of God. But what is this relationship with God? This may seem like an impossible query. How can a human have a relationship with God, the creator of the entire universe? We are used to relationships with our fellow humans; these relationships are characterized by mutual support, or antagonism, or indifference. Assuming God is a real being, we have a relationship with Him, just as we have relationships with our fellow humans on Earth; if it doesn't seem like we have a relationship with Him, that just means that our relationship is characterized by ignorance, or perhaps worse, indifference, just as so many of our relationships with humans are.

The first step to improving this relationship is to acknowledge that God exists and try to be more open to Him. The first step in improving a human relationship is to listen more, to be more attentive; so it is with God. We do this by being quiet and listening for what God has to say to us. But what if God says nothing? In that case, we might feel that our relationship with Him is characterized by abandonment—as with a child whose father or mother has left. In an adult relationship with God, though, there can be no question of abandonment; we must realize that the issue is not with us or with God but with the limits of our human finitude, our ability to hear. So if God seems quiet, we must trust and wait for His voice to be heard more clearly, whether that takes a day, or a week, or even many years. A relationship with God must take into account the type of being that God is, which means understanding God as a being that works on timescales that are vaster than ours are; we cannot be upset if he doesn't immediately answer us as we might expect a human relationship partner to return our texts and calls on the same day. The relationship with God is not a relationship between humans but rather a relationship between a human and the all-powerful, all-knowing, and all-loving creator of the universe. We must trust his timing, and we must trust that the circumstances he arranges for us are the best ones for us to be in.

We must be present in our relationship with God just as we stay present in a relationship with a human, being open and listening and staying connected; only then does the possibility of insight and trust open up. We don't need to start with trust—we simply need to start with staying connected. As we communicate and listen, the forms that we need to interact with God will be suggested, whether these are human relationships in our life that are symbols of the Divine, or are ancient forms of the Divine that have been revered through the ages and find a renewed relevance for us, or are the beloved forms of spiritual teachers that come into our lives. By following the path that opens up, we find the forms that are needed to practice the path of devotion. Even in this modern era that has identified the problems with religion without providing a replacement, if we trust the spiritual path that unfolds, the heart will still be able to fulfill its desire for the Love of the Divine.

1 note

·

View note

Text

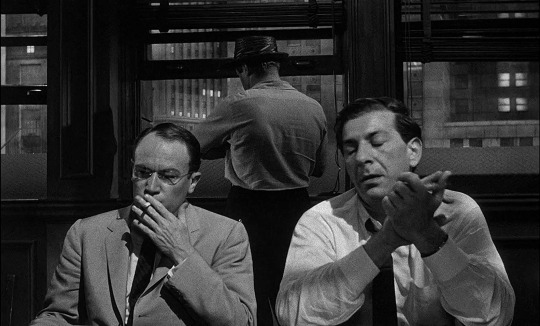

12 Angry Men: Facets of Film

Once a movie gets a great cast, good characters, a well-written script and a good production team, there’s only one thing left to do before it’s ready for the big screen.

Or more specifically, there’s a whole lot of things left to do before it’s ready for the big screen, all encapsulated in a not-so-simple process: moviemaking.

Turns out, there’s a lot to making a movie. There’s cameras, music, sets, special effects, costumes, and a whole lot of other stuff that has to go into piecing together the parts of a coherent narrative in a way that makes sense to an audience, as well as looking appealing. These are the elements that can sometimes catch the attention of an audience, taking a film from good to great based on the ‘movie magic’ elements of the movie in question.

These are typically most easily seen with big budget, special-effect heavy films like Star Wars or Independence Day, but of course, the tips and tricks of Hollywood are used in even the smallest of the small. It’s inescapable: if it’s filmed, there has to be even the barest minimum of these aspects to making a movie.

At first, this can sound like I’m talking out of both sides of my mouth here. After all, as I’ve pointed out in previous articles, the most important thing in any movie is the characters and story, as without them, the ‘movie magic’ seems like so much sound and fury.

And that’s true. Without a substantial story or characters the audience cares about, no amount of special effects or pretty cinematography is going to save it. However, that does not mean that the ‘trimming’ isn’t important.

The purpose of all of these elements of movie-making (facets of film, if you will) is not to replace the story, or distract from it. They are used to structure it, to enhance it, to assist the story and make it easier to subtly get across things to the audience.

For example, in 12 Angry Men, Juror #8 is the only character in a white suit, emphasizing the idea that he is our hero, one of the ‘good guys’. The fan in the room, invaluable on the hottest day of the year, only begins to work once the tide of the votes have begun to change. Neither of these things is coincidence. They are put in the film for a purpose: to tell you things about the characters and the story that the movie itself doesn’t have to in words.

See, the production of a film is directly tied to the story it’s trying to tell. It serves as a vehicle, the method by which the story is told.

With that in mind, it makes a lot of sense that the production of a movie be as important as it is.

All of these ‘movie making tricks’, camerawork, music, set design, etc., are all factors involved in what I call ‘visual shorthand’, or ‘storytelling shorthand’. The point of these elements is very simple: to tell the story in ways that the audience can understand immediately, without having to be told in dialogue. The skillful application of these methods makes the film easier to understand, as well as more impressive and enjoyable. It is the use of these elements that mark the difference between a competent director (or an incompetent one) and a great one.

This leads us to today’s question.

Did 12 Angry Men happen to use its ‘facets of film’ wisely?

At first, it might seem like the film is already in trouble. Sidney Lumet was untested in the movie directing business, having only worked on television shows before, and it seemed unlikely that this low-budget piece set largely in one room would be the show-stopper as other epics of the time such as Ben-Hur or Bridge on the River Kwai.

Frankly, that’s true.

12 Angry Men is by no means a big-budget extravaganza, but that does not negate it’s uses of movie magic. Indeed, as a matter of fact, this film turned out to be an excellent study in the subtle uses of ‘storytelling shorthand’. Let’s take a look, starting with one of the more easily overlooked elements of a film: cinematography.

On the surface, it can seem like 12 Angry Men is shot in a rather dull manner. The camera switches between shots of the whole room and table to shots of the individual or grouped jurors who are speaking. And to be fair, there isn’t a whole lot else to be done with the camera in a film that relies on dialogue, and never leaves the jury room.

But the production team was smarter than that.

While both the cinematography and the sets are simplistic, that does not mean they are simple.

Even the casual viewer can pick up on the rising tension as the film progresses, and while the aforementioned viewer might attribute this to writing and performances, there’s a little more to it than that, aided by the subtle use of camerawork.

While it’s true that the excellent writing and masterful performances do the bulk of the tension rising, the camera operators had something to do with it as well. The careful movie-watcher will notice a subtle change with the camerawork between the beginning of the film and the end.

In the beginning of the film, the shots are wider. There are very few closeups, and the ones that do exist are there to establish characters. The camera is a respectable distance away, across the table from each juror. As the film goes on, however, the frequency of these shots changes.

As time passes, more and more close up shots are used, emphasizing more emotion as we learn more about the jurors as people. This furthers not only our personal connection with the jurors, but the intensity of the situation, letting the audience feel the urgency without having to be more obviously cued. Director Sidney Lumet put cinematographer Boris Kaufman (Oscar-Winner cinematographer for On the Waterfront in 1954) on the task, saying this: “I shot the first third of the movie above eye level, shot the second third at eye level, and the last third from below eye level. In that way, toward the end, the ceiling began to appear. Not only were the walls closing in, the ceiling was as well. The sense of increasing claustrophobia did a lot to raise the tension of the last part of the movie.”

And it really works. Very simple, but effective, much like the movie in general.

The film being shot in black and white serves it well, with stark contrasts and even more attention drawn to Juror #8’s white suit, the only real piece of ‘costuming’ involved. After all, all the ‘costumes’ needed to consist of was very simply suits, normal dress for the time. Even the set was very simple. It’s a jury room, again, nothing special. The only other settings in the film is the outside of the courthouse, during which an excellent use of the camera takes the audience around the interior of the building before settling on the room in which the trial is taking place. It’s an excellent mood-setter, giving the audience a taste of what to expect in tone before the film gets going with its story.

But there’s more to the production of a film than sets, cameras, and costumes. Let’s talk about the music.

Again, the observant viewer may have picked up on the fact that there isn’t much of a score to 12 Angry Men. The music is there, but there are a lot of quiet moments in the film without music playing. There are two notable instances, however, where the music does quite a bit with mood-setting:

The first instance is in the beginning, as the jury retires to the jury room to deliberate on a verdict. The music is slow and sad as the camera focuses on the defendant, heightening audience sympathy for the character, a wise choice as it increases the audience’s interest in hearing the verdict, and increasing the reaction when the vote comes down so heavily in the ‘guilty’ favor.

At the end, however, there is a noticeable, if subtle, change.

The same style of music is played as Juror #8 heads down the steps out of the courthouse, but done as more of a triumphant fanfare. The day is won, justice has been served (hopefully). The music really only plays during scenes with little to no dialogue, with the rest of the film’s background being mostly silent, emphasizing the dialogue and performances going on.

How about those performances, huh?

All twelve main parts in this film are played to perfection, even more impressively as each character is thoroughly human. There are no knights, no cops, no ‘heroes’ to be found here as typically thought of in the realm of film, these are all, plain and simply, men. They are people that we can easily imagine running into or even being ourselves. Each character is played believably, in genuine, unpolished humanity, and in a way, it is this element that sets this movie apart.

The costuming isn’t anything special, and the sets, while well constructed and believable, is very simply a jury room. They are both contemporary, and aren’t the point. This film isn’t about flashy visuals, sweeping landscapes, or incredibly powerful musical scores: it’s about the performances.

Any film, no matter how good the script, cinematography or effects are, is nothing without decent, believable performances from its main cast, and it is here that 12 Angry Men truly shows its merits.

Every line of dialogue in the script is spoken with raw realness. The characters sometimes pause and stutter, all shown as individuals (even those with smaller parts) with lives and opinions of their own. Every juror is perfectly realized, from the earnest, organized Juror #1 to wishy-washy fast-talker Juror #12. Every part, notably Jurors #8 and #3, feels real, as though they are people, not characters, and it is there that the movie shows its strength. The acting perfectly matches the gravitas and realism of the rest of the film, with each character clear enough that the audience establishes a connection with them, and after all, that’s the point.

There isn’t a single piece of this film that feels out of place, or unbalanced. While the film’s production can seem unremarkable at first, a deeper look shows that every aspect of this film fits in exactly where it’s supposed to for the film to hit home. Nothing overshadows the script or the actors, with each ‘storytelling device’ used to heighten and accentuate, remaining subtle and in the background, allowing the audience to focus on the story and characters. Although it can seem like there’s not much to look at with this low-budget, single-set piece, Sidney Lumet’s Hollywood debut proves that you don’t need a budget to effectively use the tools at your disposal.

It all fits together, blending to become a quiet, subtle masterpiece that more than deserves its title as one of the greatest movies ever made.

But as I mentioned, none of this was an accident. We looked at the moviemaking magic, it’s time to look at the magicians themselves. Join us next time while we take a look at the facets of filmmaking: the behind the scenes of 12 Angry Men. Hope to see you there.

#12 Angry Men#12 Angry Men 1957#1957#50s#Film#Drama#Crime#PG#Henry Fonda#Lee J. Cobb#Ed Begley#E.G. Marshall#Jack Warden#Jack Klugman#Joseph Sweeney#George Voskovec#John Fiedler#Robert Webber#Edward Binns#Martin Balsam#Sidney Lumet

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Realism

In this lecture, as always we covered various subtopic such as the new consideration of reality and how realism corresponds to the arrival of Modernism. The emphasis on realism which is connected to the breakdown of the academic system and what is actually classed as realism. The way artists began to paint real life and the variety of social classes, painting the reality of the streets due to being ‘flaneurs’ and being socially concerned.

Lets begin!

Baudelaire, was a French poet in the 1850′s and was very important in the rise of modernism, which of course paved the way for many art movements, expressionism, the Dada and abstraction only being a few. He claimed that we should “snatch its epic quality from the life of today and make use see and understand how great and poetic we are in our cravats and leather boots”. In other words, we should look at the now and the world we are living in instead of focusing on the past. As spoken about in many of our lectures the academies produced very rigid drawings and paintings (in the way that there was a set of rules which YES produced great works but meant artists couldn’t experiment).Thus many artist took the root of realism, a way to paint something different, something relating to the contemporary world which of course wasn’t taken well by the academy.

Gustave Courbet ‘Burial at Ornans’ (1850) was painted with the real people from in Courbet’s village and thus all the figures were recognisable. There is a sense of realism, as he hasn’t idealised the figures, but has left with the correct features, the size of it and attention to detail would suggest the same importance as a history painting (even though its not a depiction of anyone important). It’s not to say that there wasn’t painting of rural civilians at the time such as Jean-Francois Millet ‘The Sower’. However they are not portrayed in importance were as part of the seasonal change. In the ‘Sower’ there isn’t anything to express a self-identity to the individual, his eyes are covered, and his face has too much shade thought it to be able to recognise who it is. In contrast to Courbet’s work we can see most of not all the faces of the figures and are able to find distinguished features matching each person.

Courbet ‘The Artist’s Studio: A real Allegory’ (1855) was painted to go with his realistic manifesto, around this time many different artists were creating groups of like-minded artists which didn’t want to follow the tradition of the academy. As he was refused by the academy, the painting was exhibited on the gates outside, as a message against him. The painting is of a daily scene however is again in a very large scale, which shocked the public as they couldn’t understand why he would draw such a scene with such importance. A complex painting discussed in in sheep’s skin. Of course, realism varied in different regions, for example the realism presented by Courbet is not the same as William Holman Hunt's ‘Scapegoat’, he focuses on the details of every single aspect. The technique Hunt used was much more realistic, with every single hair of the goat being defined, were as Courbet followed realism through political and social changes.

This was also showed by Manet ‘Le Déjeuner sur I’Herbe’ which broke many traditional rules. We can see two men which seem to be academics with a naked women. It would be alright to have a nude painted as that could be Venus, were as in this painting she is a real women naked with the men, WHY? Her gaze is directly at us, her smirk makes it, so she isn’t the usual shyness were as she is judging us. In contrast, to Alexandre Cabanel Venus, were the women is covering her face and is in an unnatural setting. In Manet’s painting there is a challenging gaze, she is a strong women and not ‘decoration’ for a scene.

This was followed with Manet’s ‘Olympia’ were again we are presented by a prostitute (we know due to the black ribbon on her neck) in this he used a black outline which was the opposite of what the academic schools would teach, we know he had the ability to create the correct shading but decided not to. The use of a prostitute created a message due to the increase in France at the time, it was known for many men (even married) to pay visits often. Such themes can be further seen in the ‘Bar at the Folies Bergere’ where he presents a bar maiden in a complex painting with incredible reflection of the bar. Through this we have an insight of what this world looked like, there is almost a feminist message though the legs presented in the top corner, as men only look at women as parts and not a holistic presence. The reflection could be a suggestion of how women are reflected in the real world.

The last painting I wish to talk about is by Edgar Degas ‘Women Ironing’ (1890/1892). The face is anonymous and like Manet there is a black line around the figure, creating an artificiality. Perhaps a link that she isn’t just an ironer, but is probably a prostitute as well. This painting can be found in the Walker Art Gallery, which is why I insist for people to go and see it, entrance is free! This painting is a personal favourite, as well as my lecturers. The way Degas has placed the figure allows the viewer to feel the labour this women has to go through to earn some type of living, we can only imagine the pain she would feel on her back due to the posture she has to maintain.

In conclusion, I did thoroughly enjoy this lecture. I find it so fascinating that artworks which are now considered masterpieces back then were questioned and criticized for being unusual and perhaps unrefined due to the standard of painting they desired. During this time I was struggling ti find a painting to do my presentation at the Tate but after a brief mention of Camille Pissarro, I was immediately intrigued. The presentation is now over and I think it went quite well, maybe I’ll post it as a blog since I was quite happy with the ending result. Thus lecture was indeed very helpful.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Without the I Word, Beware B and P

As Nancy Pelosi struggles to contain increasing demands for the Congress to impeach President Trump, his Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo ratchets up tensions in the Gulf of Oman, as it has done in countless other historical circumstances, making war with Iran look imminent. Now more than ever, Americans need to know that beyond oil, the Middle East, like the rest of the world, is divided between right and left. Iran is the leader of the left-oriented Shia version of Islam, while Saudi Arabia leads the right oriented Arab world. Meanwhile, Israel, as it continues to occupy Palestinian territory for over seventy years, has gone from being a left-oriented society in which the kibbutz played a central role, so far to the right that it often agrees with fascists. Across the Middle East as elsewhere,“Follow the money”, corresponds to the left-right divide.

Unlike American ignorance of current foreign affairs, few people across the world have a false idea of the French Revolution of 1789: driven by popular hardship, the sans culottes got rid of a monarch, opening the way for an organized left that carried out the Russian Revolution of 1917, followed, in due course, by the Chinese Revolution of 1949. These three revolutions duly claimed their place in history and in the popular imagination, however, after the defeat of Nazi Germany, the US installed ‘liberal’ parties in Western Europe, Eastern Europe modernized under a Soviet controlled authoritarian form of social democracy, while Iran was still a relatively poor country whose population was in need of everything from health care to education and housing. In 1953, when Iranians elected a lawyer named Mohammed Mossadegh to lead the country, the nationalization of their oil bonanza was a no-brainer. Alas, this coincided with the growing realization by the US of the crucial role of ‘black gold’, as American automobile ownership tripled, and petroleum became the magic fluid that generated prodigious development in the West. In what was to become a pattern, the CIA and M16 worked in tandem to overthrow the Iranian popular government and put the exiled Shah back in power.

Twenty-six years later, in 1979, popular forces carried out a revolution against the Shah’s iron rule that has never been understood by the West, which saw the new leaders exclusively as religious fanatics. In reality, when Ayatollah Khomeini returned from exile in France, he was accompanied by a socialist theoretician. Ali Shariati had been in and out of jail while teaching high school and campaigning for change. Eventually, he was allowed to accept a scholarship to France, where he studied with Islamic scholars, earning a PhD in sociology and the history of religions in 1964, while discovering the third world political theologist Frantz Fanon, collaborating with the Algerian National Liberation Front and campaigning alongside Jean-Paul Sartre for an end to French colonialism. Returning to Iran, Shariati founded the Freedom Movement of Iran, gathering followers throughout \society.

His sin was to have revived Shiism’s revolutionary claim that a good society would embrace religious values. He taught that the role of a government under a learned clergy, was to guide society according to Islamic values rather than managing it, allowing human beings to reach their highest potential rather than encouraging the West’s hedonistic individualism. Believing that Shia Muslims should not await the return of a mysterious 12th Imam, (as the Jews await ‘the Messiah’) but hasten it by fighting for social justice, even to the point of martyrdom, Shariati criticized the Shah’s clerics and translated the claims of Iranian Marxists that revolution would bring about a just, classless society into religious symbols that ordinary people could relate to. Seeing a direct link between liberal democracy and the plundering of pre-modern societies based on spirituality, unlike Fanon, he believed that people could only fight imperialism by recovering their cultural identity, including their religious beliefs, which he called ‘returning to ourselves’. (Like a growing number of contemporary leaders — such as Vladimir Putin — Shariati called religious government ‘commitment democracy’, as opposed to Western demagogy based on advertising and money.

The panic that gripped the West in 1979 when 52 American diplomats were locked-into the Embassy for 444 days, was heightened by Israel’s victory in the Six Day War a few years earlier. Since that time, while continuing to deny the Palestinians a state of their own, Israel has moved closer to the most powerful Sunni (i.e., conservative) Arab nation, Saudi Arabia, which supports ISIS and its offshoot terrorist organizations worldwide, and wages an unrelenting campaign against the tiny country of Yemen, whose revolutionary Houthis are also supported by Iran, in the millennial battle between Sunni and Shia.

Few Americans know that these two are strongly correlated to the left-right divide. Western media correctly attributes the conflict to attitudes toward Ali, the Prophet’s designated successor, but it features Shiites lashing themselves with chains in solidarity, without mentioning that the reason for Ali’s murder was his defense of the lower classes. In turn, that attitude was based on a disagreement over whether God had attributes, such as ‘justice’ and hence could demand that humans treat each other with respect and dignity.

Arising after the Prophet’s death, the argument centered around whether the Quran was an emanation of God, or had always existed. In turn, the answer to that question depended on whether God simply ‘is’ or whether, like humans, he has attributes, one of which would be ‘justice’, or solidarity, which would imply the existence of free will. At one point, a free will defender who got up and left the discussion was labelled a Mutazilla, or ‘one who has left’. During the following centuries, and mainly under the Abbasid rulers centered in Persia, the Mutazilla movement lead to the development of Shia Islam, with a different set of laws from those of the Sunnis, who still believe that individual lives are foreordained by a God who is neither ‘good’ nor ‘evil’, but simply ‘is’, and that men must obey Him without question. Under the cleric Wahhab, that conviction led to the extreme of Sunni Islam, in whose name terrorism is carried out to this day.

The notion of a ‘Shia arc’ suggests an equally threatening military entity, when in reality it is an ideological one. Although nothing could be further from the minds of those who hold Trump’s foreign policy in their hands, Ali Shariati and the Iranian revolution revived Shia Islam’s original message that men must treat each other with dignity and respect. The original seat of the Mutazilla movement was the city of Basra, located on the Persian Gulf Shat al Arab waterway, and the Shiite learning center of Najaf, near the southern Iraq/Iran border, was the headquarters of Iran’s exiled revolutionary leader, Imam Khomeini. After spreading from Iran to Iraq, Shia Islam reached Syria and Lebanon on the strength of its commitment to justice.

In Syria, the life values of Islam had already led to the creation of the Baaʿth Party, which in 1953 merged with the Syrian Socialist Party to form the Saddam Hussein’s Arab Socialist Baaʿth (Renaissance) Party. Although both countries belonged to the non-aligned, anti-imperialist and anti-colonialist movement, the merger failed. (The US suffered the Baath being the party of Saddam Hussein as long as he was waging an eight-year war against socialist Iran.) Syrian Shiism continues to be represented by the small Alawite sect headed by the Assad family. Reaching back to the ninth century, the Alawites, who pray sitting rather than prostrate, and celebrate some Christian holidays, had been rejected by the Shiite hierarchy until Assad’s father, Hafez al Assad, came to power in 1964. Though accused by the US of “killing its own citizens”, Assad’s son, Bashar, heads the only secular government in the Middle East (including Israel), and retains the educational system and Western social customs that prevailed under the French mandate (1923-1964).

In neighboring Lebanon, the Shiite militia known as Hezbollah represents a powerful political force in a tiny nation whose population is divided among half a dozen religions and sects, including the Christian Druze and Maronites. The picture painted for Westerners is of a rabble acting on orders from Iran, while Hezbollah is allied with the Shia militia Hamas in the struggle for an independent Palestine, making Syria ‘the frontline state’. (Alastair Crooke’s book Resistance: The Essence of the Islamist Revolution, attributes Hezbollah’s victories over the Israeli army to ‘horizontal’ organization, which encourages a high level of individual initiative, and is part of the surprisingly sophisticated knowledge of Western political thought by its leader Hassan Nasrallah.)

This makes the fact that the Second Amendment to the US Constitution, which reads: “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed,” all the more ironic. America is the only modern nation whose citizens have almost automatic access to guns, resulting in thousands of murders every year, while its leaders insist that foreign national militias must be punished by a so-called ‘rules-based’ international community.

Last but not least, in this saga, like the cherry on the cake, the American public is oblivious to the decades-long ties between Iran and its neighbor, Russia, based on both a shared revolutionary commitment to ‘dignity and respect’, and to religious values. It is disquieting, to say the last, that when the two B’s threaten Iran, they are threatening Russia outside the narrative familiar to American voters.

1 note

·

View note

Text

something that impacted me in reading about the Futurists, thinking about both the potential that kineticism as a representative concept, the means by which motion and kinetic escalation is represented through aesthetic means, is paired with the aesthetics of war, militarism, industrialization, and in fact that there was socialist and anarchist involvement in Futurist art in addition to the obvious (and in many ways definitive) fascist character of the movement invites a great deal of questioning about the political nature of the aesthetic, the purpose of art, exactly that which is meant by art, the way that art takes on certain character, including class consciousness, or of course reversal thereof.

the corporate appropriation of art is often interesting even as an affect: the deconstruction of fashion present in Virgil Abloh’s work for Off White’s collaborations with Nike is effectively acting toward a kind of self-aware dual return to the process of creating the shoe: it is a creation of creation, the process by which work is generated itself part of the completed work, a kind of act of presenting the evidence of the process for evaluation. The way that this alludes to sample sales, works in progress, the way that one has a sense of pre-fashion, a kind of unready-for-wear in Off White’s clothing, is thusly drawn out by the way in which it mimics something akin to industrial pre-production, the process of industrialization behind custom clothing such as this made obvious through that very process itself.

in turn, we are at a moment akin to those which propelled many of the Futurists in relation to war: akin to the aimless and disaffected veterans which became the first fascists, the Vietnam Vets who started the militia movement and formed a reactionary backbone to the 90s resurgence in militias which itself made space for current white supremacist movements of various sorts, there is a way in which the “future” is being reappropriated by fascist ideology. the way in which a proliferation of a kind of hyperreal, futuristic post-postmodernity aesthetics have used the shock of violence, the distance that ironic reference to the abjection of fascism and its violence affords, the way that a humorous and satirical character that coupled itself with a great deal of early Vaporwave was appropriated by those who interpret Cyberpunk as a parable about how great it is to be a fucking rich parasite, how incredible it is to not only accept the violence of poverty but to in fact revel in it, use it as a means of obtaining targets, the endless remove of renaming and resignification found by an ever-changing lineup of memes and references that go far beyond the racial coding in the use of “Monday” as a racial slur and pushing believability even further, relying on a process of ironic distance and development of further second-order acts of signification to build up an entire vocabulary of violence around their various symbols and signals, there has been a kind of reproduction of the notion of process-as-work as well as a process-of-work-as-process such that in addition to classic signs of white supremacy and fascism (which can be deployed when the desire is to outwardly and obviously signal white supremacist affinities) there is an entire constellation, a wide assemblage of weighted and doubled words that stands in contrast to the obvious, such that it can be easily denied.

Fascination with the aesthetics of death, of violence and militarism, are not by any means inherently fascist. In fact, the militarism of the aesthetics at hand makes it such that looking at the real-world embodiment tied to it, the way in which images of either training for or exerting colonial violence figure heavily in these fascist aesthetics (militiamen, soldiers, special forces, police) leaves a great deal of room both for the same approach to leftist forces (as well as the questioning of imperialist hegemony through the introduction of nations considered anti-imperialist or at least making hegemony less stable, less totalizing, although in the case of nations such as Russia this is already employed by some fascists) and a kind of double resignification of the hegemonic forces such that the eye is on them as that of an insurgent, stealing the CIA’s copy of Mao’s guerilla tactics, a recognition of fascist creep and a kind of turnaround upon it.

Indeed, there are induced bodies and processes that one can find in certain contemporary flows of musical and aesthetic generation. The well-armed Springfield XD toting war machines found in gangster rap with lean and LSD floating through their veins and AK-47s on the hip, organs of desire generated and deflated all at once by the eightball of executive-quality cocaine liberated from the pocket of a kidnapped businessman with his mouth duct taped shut, the ecstasy and agony of meth and ecstasy purchased at gay nightclubs once owned by the Mafia, the bleeding-edge of tumblrs with self-hating yandere anime girls surrounded by alprazolam and ketamine, how all of these aesthetics inform(ed) the vulture culture of vaporwave as well as its own self-reflective inquiry upon itself, the recognition of assholes proved to be as much by James Ferraro questioning what exactly vaporwave “is”, a strike upside the head to the NazBol irony posters who made one good mixtape exactly under the microgenre of Hardvapour before confusing themselves with Krokodil references when selling real heroin makes far more sense, a necessary bit of actual embryonic and transformative (as opposed to the fascist affected-obscurantist) psychedelica, so that one may substitute Terence McKenna for the Joe Rogan they currently entertain themselves mocking, one might move toward new means of militia-making, the recruitment for new war machines. Black and Lavender and White and Teal and Red Panthers collaborating against the police, anarchist banners flying from tanks and acting as unit emblems, circles of self-criticism with Maoists and Post-Leftists able to spend an entire half-hour talking without accusing the other of being a plant or liberal, a kind of combined-arms approach that acknowledges the opposite in the enemy, the embracing of supposedly degenerate cultural movements in their fascist forms, the roles of gay men and trans women and lesbian tradwives and cringeposting solipsistic subjectivities that excuse their own violence with the personal gain they see from it in the movements of nationalist, fascist, reactionary, and generally contemptible politics, one can indeed interpret movements in relation to study of shock, of development, of how the contemporary is informed by imagination of the past.

Questions regarding the place of Soviet Realism are best asked in a form of representation, the use of a wider act of questioning to gesture toward a kind of unsureness regarding exactly what the purpose of such art (or artlessness) functions as, a record for the ideal, of ideation in the present and realized through the reading of such artwork, the inclusion of certain events and bodies into a process of deep and concerted rectonition through this realist lens a reflection of their material consequence, one that affirms certain questions of what kind of memory “matters” when the subjective and immediate is seen as the basis of experience, the way in which the opposite, the abstract, holds a kind of power such that the ever-disappearing “present”, the disappearing “Real”, is best represented through paintings such as Guernica, the horror of fascist violence rendered as literal cat-and-mouse by Art Spiegelman, the means by which Eli Valley has taken on Spiegelman’s consciousness of fascist violence in the time of Trump (the sort of mainstream figure that the fascists adore) and represents it through a kind of grotesqueness that is at once genuinely revulsive and allegorical like the work of Junji Ito, the many means of representing provide experiences-of-experience of new orders.

One must envision a militant Spring Breakers, the sort of unreality crafted toward a deeper “Real”, the horror of realizing exactly what is represented by that which one draws from coupled with a kind of earnest return only possible after ironic distancing, such that one confuses all senses of assessment until it is too late, the moment of revolution now at hand.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Jewish Magical Creatures/Beings (with recs)

So @biperchik was looking for some resources on Jewish magical creatures and I was going to make a short list and message them but then...this happened. Anyway, I’ve been planning on making some info posts since I just finished my Jewish Magic class. So I guess we’re starting here! I’ll be posting detail posts for different categories soon.

From what I have read I would say there are three major categories of “creature,” all anthropomorphic: golems, dybbuks, and demons. There are others that don’t fit into these, which I’ll list further down, but as far as I can tell these three categories are the main ones.

Golems:

· Schwartz has a section in Tree of Souls from pages 278 to 286 which covers pretty much all the main golem narratives. There are also a few passages in other sections which deal with golems, including in his creation of man section (some narratives say that Adam was a golem, which is a really interesting intersection of the two creation narratives in Genesis and I will blab about that later on my magic blog 😝)

· Goldsmith, Arnold L. The Golem Remembered: 1909-1980: Variations of a Jewish Legend

· Schäfer, Peter. “The Magic of the Golem: The Early Development of the Golem Legend.” Journal of Jewish Studies, vol. 46, no. 1-2, 1995, pp. 249–261., doi:10.18647/1802/jjs-1995 (This one is a journal article, I don’t know how accessible it is or what level of info you’re looking for)

· Golem! Danger, Deliverance, and Art by Emily D. Bilski. Haven’t looked at this one much but it has some cool art as well as the text which I have not read at all and it looks like it talks a lot about different portrayals (probably mostly modern/contemporary)

· Scholem, Gershom Gerhard. On the Kabbalah and Its Symbolism. This is a book about Kabbalah generally; I know it talks somewhat about golems specifically and I think a number of other books on Kabbalah do as well since its tied in tightly with Jewish mysticism (because golems use name and letter magic and are almost always made by rabbis…I have words to say about “acceptable” acts of magic and elitism and patriarchy, but that’s a whole other rant)

· Golem by Moche Idol (haven’t looked at this but my prof recced it)

Dybbuks:

Other than Schwartz, I only have one rec for this: Between Worlds: Dybbuks, Exorcists, and Early Modern Judaism by J.H. Chajes. It gets pretty technical in some places (apparently, our professor had us skip them) but it’s pretty good and has a lot of information and narratives surrounding the exorcism of dybbuks in Early Modern Europe.

Oh, also Trachtenburg’s Jewish Magic and Superstition has a number of chapters on spirits.

Demons:

Okay so this category is really wide. I’m gonna give you some recs but mostly just subcategories to look into. Also infodumping because demons are my jam right now.

Jewish demonology goes back to at least the adoption of the Zoroastrian mythology into Jewish belief, since that is where a lot of this comes from. A lot of Jewish (and non-Jewish) demonology also comes from the gods of other surrounding societies.

Later Jewish demonology kind of faded into the background and Medieval/early modern European Jewish demonology is a lot less intricate and varied probably, but is also probably what most resources are going to be pulling from.

Joshua Trachtenburg’s Jewish Magic and Superstition is great and has a couple chapters dealing specifically with demons. It’s pretty old so it might be available for cheap/free, idk. My prof just posted literally the whole book in our resources for the class. It’ll also give you a lot of terms which might make finding stuff easier.

Schwartz has a big section on demons (and also Gehenna). It has a lot of older and more specific stuff too.

Different things to look for:

Lilith and the lilim are a big deal; Lilith is one of the very few specific demons that has survived into the medieval and early modern era.

Ashmadai is the king of demons (originally Zoroastrian). There are some stories about him and King Solomon from pretty early in the integration of his mythology into Judaism.

Another word describing demons in general is mazikeen/mazikeem

There’s a story called The Tale of the Jerusalemite which includes Ashmadai. A guy winds up in a town/kingdom of demons, some of whom study Torah. Ashmadai is really into Torah in the Solomon myths too. Trachtenburg talks about this also; its related to an idea that demons are constantly searching to become a more complete and perfect creation.

The main creation myth for demons is that they are unfinished because God started making them before Shabbos and had to stop, then left them that way in order to show the importance of keeping the Sabbath.

Magical creatures from other cultures were integrated into medieval/early modern European Judaism with a creation myth saying that they were the children of Adam copulating with a demon (possibly Lilith?) during his (100 year?) separation from Eve after leaving the Garden of Eden. Trachtenburg talks about this too.

More animal-like creatures (from the “mythological creatures” section of Tree of Souls, p. 144-151)

· Adne Sadeh, who doesn’t fit in this category because it’s a kind of primitive man but it is so freaking cool so I don’t care. They’re attached to the earth by an umbilical cord.

· Leviathan

o Sea monster

o Want dragons? Here is a dragon

o The Great Sea/Okeanos is on top of Leviathin’s fins.

o God takes this guy for walks

o We get to eat it in the World to Come

· The Ziz

o Big bird. Very big bird. The ocean only comes up to its ankles and one time its egg broke and flooded sixty cities

o Messenger of God

o We get to eat it in the World to Come

· The Re’em

o A horned creature kind of like a unicorn or rhino but like…big. Really big.

“A re’em that is one day old is the size of Mount Tabor” big.

· The Phoenix

o “the only creature that didn’t eat the fruit of the tree of knowledge.”

o Guards earth from the sun

o “Over a thousand years, each Phoenix becomes smaller and smaller until it is like a fledgling, and even its feathers fall off. Then G-d sends two angels, who restore it to the egg from which it first emerged, and soon these hatch again, and the Phoenix grows once again, and remains fully grown for the next thousand years.”

· The Lion of the Forest Ilai

o It’s like a lion but it roars super loud. I don’t know how big a parasang is but it made Rome shake from four hundred parasangs away.

o Basically there’s a line in Amos 3:8 that uses lions as a metaphor for G-d and the story says Caesar was like “hey lions aren’t that bad people kill lions” and Rabbi Joshua ben Haninah was like “um no not this lion.”