#tikuna

Photo

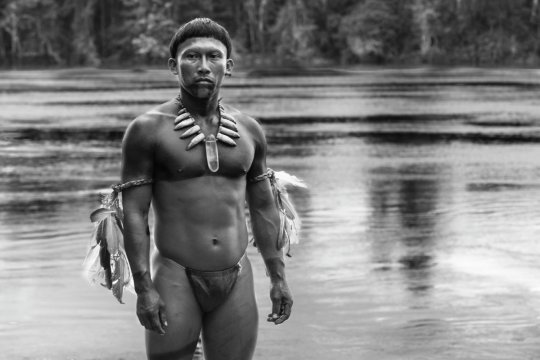

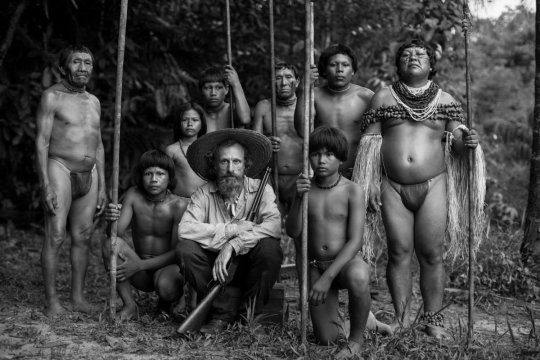

Embrace of the Serpent (El Abrazo de la Serpiente) | Ciro Guerra | 2015 | Colombia

#embrace of the serpent#indigenous films#ticuna#el abrazo de la serpiente#tikuna#ciro guerra#black and white cinema#films#movies#indigenous cinema#cinema#ocaina#2015#2010's#colombia#amazon#colombian cinema

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brazilian Amazon River Turns into a Desert and Indigenous People Get Sick from Drinking Contaminated Water

Huge sandbanks have formed and, with dirty water in the stream, indigenous people suffer from diarrhea and vomiting

The Solimões River is a central vein of the Amazon. It carries ancestry, connects regions and countries, gives life to a multitude of traditional communities on its banks and on the banks of tributaries and streams.

The stretch that bathes the Porto Praia de Baixo Indigenous Land, in the Tefé region (AM), has turned into a desert. The mighty river, which dictated the rhythm of the community, has been replaced by huge sandbanks as far as the eye can see. Kokamas, Tikunas, and Mayorunas cross these sandbanks from one bank to the other, from one end to the other of the indigenous land, in an image reminiscent of a desert.

Continue reading.

#brazil#brazilian politics#politics#environmentalism#environmental justice#indigenous rights#amazon rainforest#mod nise da silveira#image description in alt

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

i want to learn spanish. and french. and japanese. and brazilian sign language. and latin. and arabic. and mandarin. and tikuna. and esperanto. and

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Colonial Language in Indigenous Queer Spaces

Experience, perspective, and culture contribute greatly to the formation of language. Why it is "flower" in English and "wâpikwaniy" in Northern Cree dialect can be explained by geographic, cultural, and grammatical formation differences. Knowing this, let's discuss the erasure of Indigenous language in "queer" (a colonial term) spaces and how the linguistic aspect of gendercide continues to harm Indigenous peoples.

Waziyatawin Angela Wilson writes “Language is linked to systems of thought, which are linked to history and to identity. Every description of the world depends on language, every ceremony conducted depends on language, every teaching about the past depends on language; Language conveys the meaning of life. Because of this connection, history cannot be discussed without consideration of the state of [language] and where they intersect and apply to one another” (Wilson, 2005). Language is shaped by and acquired through lived experiences on the land and with Her creations; Language also shapes how the world is perceived and explained. If/when language is translated, or if words and terms are removed, the intended meaning or message may very well be lost. The impacts of colonialism on language alter and destroy original meanings and connections, while fracturing the relationship between the people and their traditional culture, knowledges, and practices and contribute to the Pan-Indigenization (or forced homogenization) of Indigenous knowledges. In relation to queerness, preserved language shows that queer Indigenous identities predate colonial language and understood identities yet due to harmful stereotypes of both Indigenous peoples and queerness, both identities are not seen as intersectional with one another in many spaces, including both queer spaces and Indigenous spaces.

Indigenous queerness suffers from forced repression and erasure of knowledge and loss in translation. Picq and Tikuna explain that "The meanings of gender roles and sexual practices are cultural constructions that inevitably get lost when they are de-contextualized in cultural (and linguistic) translation. The spectrum of Indigenous sexualities does not fit the confined [colonial] registries of gender binaries, heterosexuality, or LGBT codification...It is not these idioms that are untranslatable, but rather the cultural and political fabric they represent"(Picq & Tikuna, 2019). Even in attempting to define known traditional Indigenous identities in other languages fails to truly encapsulate all aspects of a specific identity, nor can they be reduced to fit into settler-colonial queer identities (including the term "queer", which I do not like to use due to inaccuracy and erasure, but further solidifies the importance of language and the issues with translation) such as transgender, genderfluid, nonbinary, bisexual, homosexual, etc.

Often silenced in conversations of queerness, both in Indigenous and settler spaces, are the experiences of colonially-described AFAB (assigned female at birth) queer Indigenous individuals. Even in conversations within marginalized communities, those that benefit more from Euro-colonially implemented structures are ascribed slightly more privileges than those with multiple intersecting identities. For example, white-settler cisgender gay men are ascribed more privileges and given more attention when speaking out than a non-white or Indigenous, non-cisgender nor heterosexual individual is, and this is rampant in all queer spaces whether recognized or not. Historically, very few queer Indigenous women and third and/or other gender-identifying individuals are translated and shared, if not flat-out erased or heavily altered for colonial tastes. Bíawacheeitchish was a well-respected member of the Council of Chiefs, a warrior and chief of the Apsáalooke peoples of southern Montana; She was also married to four wives and "permanently assumed" traditional male roles, yet her story was heavily altered to fit colonially-accepted ideas and definitions of femininity and women. Not only was her queer identity erased through language, but it was also censored and heavily fetishized in accounts written by James Beckwourth (DeVoto, 1931).

English, French, and Spanish are languages that employ gendered terms. As language evolves, non-gendered terms and words make a resurgence or are created to properly address queer individuals in settler societies. In many Indigenous languages, however, gendered terms and language did not exist. For example, pre-colonial Zapotec language was not gendered, yet was rather categorized as people, animals, and inanimate objects (Picq & Tikuna, 2019). Upon the arrival of colonizers came the implementation of colonial masculine and feminine gendered language and identities, silencing traditional queer Indigenous individuals and their identities on pages and in mouths.

References:

Wilson, Waziyatawin Angela. Remember This!: Dakota Decolonization and the Eli Taylor Narratives. Lincoln, NE: U of Nebraska Press;c2005: 51.

Picq , M. L., & Tikuna, J. (2019, August 20). Indigenous sexualities: Resisting conquest and translation. E-International Relations. https://www.e-ir.info/2019/08/20/indigenous-sexualities-resisting-conquest-and-translation/

Bernard DeVoto in the introduction to Thomas D. Bonner (ed.): The Life and Adventures of James P. Beckwourth. Edited, with an Introduction by Bernard DeVoto, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1931 (reprint of the edition by Harper and Brothers, New York, 1856), p. xxiii

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A MAIOR COLEÇÃO DE BANCOS INDÍGENAS Celebrado como um dos mais expressivos, o conjunto pertencente à Coleção BEI (@colecaobei) reúne mais de 500 peças oriundas de povos de diferentes regiões: Alto e Baixo Xingu, sul da Amazônia/Centro-Oeste, norte do Pará e Guianas e noroeste amazônico. Os bancos aliam funcionalidade e beleza; ao mesmo tempo que são reconhecidos como objetos de arte e design, preservam sua dimensão religiosa e simbólica: esculpidos em madeira, muitas vezes em formatos de animais, decorados com grafismos ou coloridos com pigmentos diversos, eles espelham o universo cultural e a cosmologia das etnias que os criam. Entre elas estão Mehinaku, Waujá, Asurini, Kamayurá, Tukano, Yawalapiti, Tikuna, Karajá, Guajajara, Palikur, Waiwai e Yekuana. A coleção, localizada próxima ao Parque do Ibirapuera, em São Paulo, ainda conta com máscaras, remos, peneiras e outros objetos. É absolutamente sensacional! Para mais detalhes sobre visitação, entre em contato diretamente com @colecaobei ou através do www.colecaobei.com.br #novosparanos #colecaobei #bancosindigenas #artebrasileira #brasil (em São Paulo, Brazil) https://www.instagram.com/p/CgIWNKTvZqz/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

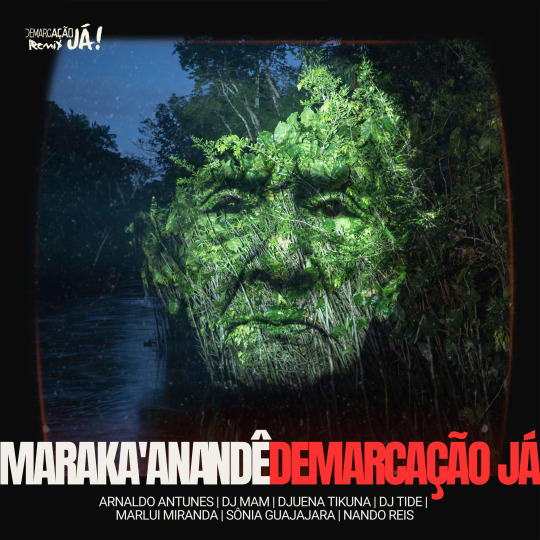

DJ Mam, Nando Reis, Arnaldo Antunes, Sônia Guajajara, Djuena Tikuna - Maraka'anandê (Demarcação Já)

On the cover, the work “Symbiosis” by visual artist Roberta Carvalho from Pará, humanizes the Amazon rainforest projecting the faces of riverine people onto the treetops.

Following the success of the “Demarcation Now” campaign, spreading the rallying cry for indigenous and environmental causes over 100 million times in its music video (2017), eight editions of the Demarcation Now Remix Festival…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Amazon drought: ‘We’ve never seen anything like this’ – Stigmatis News

The Amazon rainforest experienced its worst drought on record in 2023. Many villages became unreachable by river, wildfires raged and wildlife died. Some scientists worry events like these are a sign that the world’s biggest forest is fast approaching a point of no return.

Oliveira Tikuna says this year’s drought has been a wake up call. PAUL HARRIS / BBC

Source: Amazon drought: ‘We’ve never…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Hearing Amazônia: MIT musicians in Manaus, Brazil

New Post has been published on https://thedigitalinsider.com/hearing-amazonia-mit-musicians-in-manaus-brazil/

Hearing Amazônia: MIT musicians in Manaus, Brazil

On Dec. 13, the MIT community came together for the premiere of “We Are The Forest,” a documentary by MIT Video Productions that tells the story of the MIT musicians who traveled to the Brazilian Amazon seeking culture and scientific exchange.

The film features performances by Djuena Tikuna, Luciana Souza, Anat Cohen, and Evan Ziporyn, with music by Antônio Carlos Jobim. Fred Harris conducts the MIT Festival Jazz Ensemble and MIT Wind Ensemble and Laura Grill Jaye conducts the MIT Vocal Jazz Ensemble.

Play video

“We Are The Forest”

Video: MIT Video Productions

The impact of ecological devastation in the Amazon reflects the climate crisis worldwide. During the Institute’s spring break in March 2023, nearly 80 student musicians became only the second student group from MIT to travel to the Brazilian Amazon. Inspired by the research and activism of Talia Khan ’20, who is currently a PhD candidate in MIT’s Department of Mechanical Engineering, the trip built upon experiences of the 2020-21 academic year when virtual visiting artists Luciana Souza and Anat Cohen lectured on Brazilian music and culture before joining the November 2021 launch of Hearing Amazônia — The Responsibility of Existence.

This consciousness-raising project at MIT, sponsored by the Center for Art, Science and Technology (CAST), began with a concert featuring Brazilian and Amazonian music influenced by the natural world. The project was created and led by MIT director of wind and jazz ensembles and senior lecturer in music Frederick Harris Jr.

The performance was part eulogy and part praise song: a way of bearing witness to loss, while celebrating the living and evolving cultural heritage of Amazonia. The event included short talks, one of which was by Khan. As the first MIT student to study in the Brazilian Amazonia (via MISTI-Brazil), she spoke of her research on natural botanical resins and traditional carimbó music in Santarém, Pará, Brazil. Soon after, as a Fulbright Scholar, Khan continued her research in Manaus, setting the stage for the most complex trip in the history of MIT Music and Theater Arts.

“My experiences in the Brazilian Amazon changed my life,” enthuses Khan. “Getting to know Indigenous musicians and immersing myself in the culture of this part of the world helped me realize how we are all so connected.”

“Talia’s experiences in Brazil convinced me that the Hearing Amazônia project needed to take a next essential step,” explains Harris. “I wanted to provide as many students as possible with a similar opportunity to bring their musical and scientific talents together in a deep and spiritual manner. She provided a blueprint for our trip to Manaus.”

An experience of a lifetime

A multitude of musicians from three MTA ensembles traveled to Manaus, located in the middle of the world’s largest rainforest and home to the National Institute of Amazonian Research (Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia, or INPA), the most important center for scientific studies in the Amazon region for international sustainability issues.

Tour experiences included cultural/scientific exchanges with Indigenous Amazonians through Nobre Academia de Robótica and the São Sebastião community on the Tarumã Açu River, INPA, the Cultural Center of the Peoples of the Amazon, and the Museu da Amazônia. Musically, students connected with local Indigenous instrument builders and performed with the Amazonas State Jazz Orchestra and renowned vocalist and Indigenous activist Djuena Tikuna.

“Hearing Amazônia: Arte ê Resistência,” a major concert in the famed 19th century opera house Teatro Amazonas, concluded the trip on March 31. The packed event featured the MIT Wind Ensemble, MIT Festival Jazz Ensemble, MIT Vocal Jazz Ensemble, vocalist Luciana Souza, clarinetist Anat Cohen, MIT professor and composer-clarinetist Evan Ziporyn, and local musicians from Manaus. The program ended with “Nós Somos A Floresta (We Are The Forest) — Eware (Sacred Land) — Reflections on Amazonia,” a large-scale collaborative performance with Djuena Tikuna. The two songs were composed by Tikuna, with Eware newly arranged by Israeli composer-bassist Nadav Erlich for the occasion. It concluded with all musicians and audience members coming together in song: a moving and beautiful moment of mediation on the sacredness of the earth.

“It was humbling to see the grand display of beauty and diversity that nature developed in the Amazon rainforest,” reflects bass clarinetist and MIT sophomore Richard Chen. “By seeing the bird life, sloths, and other species and the flora, and eating the fruits of the region, I received lessons on my harmony and connection to the natural world around us. I developed a deeper awareness of the urgency of resolving conflicts and stopping the destruction of the Amazon rainforest, and to listening to and celebrating the stories and experiences of those around me.”

Indigenous musicians embodying the natural world

“The trip expanded the scope of what music means,” MIT Vocal Jazz Ensemble member and biomedical researcher Autumn Geil explains. “It’s living the music, and you can’t feel that unless you put yourself in new experiences and get yourself out of your comfort zone.”

Over two Indigenous music immersion days, students spent time listening to, and playing and singing with, musicians who broadened their scope of music’s relationship to nature and cultural sustainability. Indigenous percussionist and instrument builder Eliberto Barroncas and music producer-arranger César Lima presented contrasting approaches with a shared objective — connecting people to the natural world through Indigenous instruments.

Barroncas played instruments built from materials from the rainforest and from found objects in Manaus that others might consider trash, creating ethereal tones bespeaking his life as one with nature. Students had the opportunity to play his instruments and create a spontaneous composition playing their own instruments and singing with him in a kind of “Amazonia jam session.”

“Eliberto expressed that making music is visceral; it’s best when it comes from the gut and is tangible and coming from one’s natural environment. When we cannot understand each other using language, using words, logic and thinking, we go back to the body,” notes oboist and ocean engineer Michelle Kornberg ’20. “There’s a difference between teaching music as a skill you learn and teaching music as something you feel, that you experience and give — as a gift.”

Over the pandemic, César Lima developed an app, “The Roots VR,” as a vehicle for people to discover over 100 Amazonia instruments. Users choose settings to interact with instruments and create pieces using a variety of instrumental combinations; a novel melding of technology with nature to expand the reach of these Indigenous instruments and their cultural significance.

At the Cultural Center of the Peoples of the Amazon, students gathered around a tree, hand-in-hand singing with Djuena Tikuna, accompanied by percussionist Diego Janatã. “She spoke about being one of the first Indigenous musicians ever to sing in the Teatro Amazonas, which was built on the labor and blood of Indigenous people,” recalls flutist and atmospheric engineer Phoebe Lin, an MIT junior. “And then to hold hands and close our eyes and step back and forth; a rare moment of connection in a tumultuous world — it felt like we were all one.”

Bringing the forest back to MIT

On April 29, Djuena Tikuna made her MIT debut at “We Are the Forest — Music of Resilience and Activism,” a special concert for MIT President Sally Kornbluth’s inauguration, presenting music from the Teatro Amazonas event. Led and curated by Harris, the performance included new assistant professor in jazz and saxophonist-composer Miguel Zenón, director of the MIT Vocal Jazz Ensemble; Laura Grill Jaye; and vocalist Sara Serpa, among others.

“Music unites people and through art we can draw the world’s attention to the most urgent global challenges such as climate change,” says Djuena Tikuna. “My songs bring the message that every seed will one day germinate to reforest hearts, because we are all from the same village.”

Hearing Amazônia has set the stage for the blossoming of artistic and scientific collaborations in the Amazon and beyond.

“The struggle of Indigenous peoples to keep their territories alive should concern us all, and it will take more than science and research to help find solutions for climate change,” notes President Kornbluth. “It will take artists, too, to unite us and raise awareness across all communities. The inclusivity and expressive power of music can help get us all rowing in the same direction — it’s a great way to encourage us all to care and act!”

#2023#Amazon#app#Art#artists#Arts#awareness#bass#bearing#blood#Brazil#Center for Art#Science and Technology#change#climate#climate change#climate crisis#collaborative#Community#Composition#Difference Between#direction#display#diversity#earth#Engineer#engineering#Environment#Environmental#eyes

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

POBLACIÓN

Según el Censo Nacional de Población y Vivienda (CNVP) del DANE 2018 se certificaron 13.842 personas auto reconocidas como integrantes de la comunidad indígena Tikuna. Cabe resaltar que la población Tikuna tuvo un cambio porcentual del 75,7% entre el censo del 2005 y el censo del 2018, debido a que en el 2005 la comunidad contaba con un total de 7.879. La mayor parte de la población por no decir toda (96.9%) se encuentra ubicada en Leticia (Amazonas) a diferencia del 3,1% que se distribuye en Bogotá y diferentes partes de Cundinamarca y el país. Del total de la población Tikuna el 43,6% reside en cabeceras municipales, el 33,3% en resguardos indígena y el 23,1% reside fuera del territorio étnico.

0 notes

Text

Indigenous women are showing us how to fight for environmental and human rights

During a recent trip to Brazil, I saw how Indigenous women activists there have completely changed the political landscape

I was invited to the third Indigenous Women’s March in Brasília, the capital of Brazil, earlier this month. The last occupation of Brazil’s legislature was in January 2022, when a group of rightwing thugs, imitating the January 6 riot in the US, attempted to kill Brazilian democracy. This was the exact opposite.

Five hundred Indigenous women from across Brazil occupied the Congress – not with guns or knives or anger, but with the strength and truth of their words, the intensity of their knowing, with their headdresses, feathers and beaded primordial designs calling us to the earth, to know the earth, to protect and respect the biomes and honor Indigenous women’s rights to their lands.

There, in a space dominated by conservative white men in suits, deep in the business of mining, timber, agro-business and evangelizing – Indigenous women, once only a few, pepper-sprayed and excluded – now had their sisters as they walked through the front door with a sense of belonging, pride, pageantry and urgency. They opened with their version of the national anthem, sung by Djuena Tikuna in her Indigenous language. Those who suffered the “violence of absence” for years were suddenly undeniably present.

It hasn’t even been a year since two Indigenous leaders, Sônia Guajajara and Célia Xakriabá, were elected to Congress in Brazil. (Guajajara was later appointed minister of Indigenous peoples.) In their very short time in power – through brilliant organizing to claim demarcation of Indigenous lands, unapologetic assertion of their Indigenous culture, and mobilizing thousands of Indigenous women throughout the country, they have already shifted the policies and political landscape of Brazil.

Guajajara told me, “Many people are saying that Brasília is now breathing new air, that you can already see many cocares [headdresses] and wraps of black women within government spaces on the streets of Brasília, and we are present in all environments. So, it is certainly not just a physical presence, but also a different energy that we bring to this place, which is the energy of ancestral strength.”

What I experienced during my recent time in Brazil was nothing less than a radical re-imagining of the country’s future, but it also felt like the beginning of what many Indigenous women there are calling for – a much broader and more global agenda, a “reforesting” of politics and the mind. Before I had not been terribly hopeful; I am now.

Here are four reasons why.

Continue reading.

#brazil#politics#indigenous rights#environmental justice#feminism#brazilian politics#mod nise da silveira#image description in alt

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘EL TIKUNA’ SE CONVIERTE EN EL PRIMER EMBAJADOR DIGITAL DEL AMAZONAS

http://dlvr.it/SmQS1m

0 notes

Text

Assista a "MUSICA INDÍGENA! MARACANANDE . Weena Tikuna. Lindo Canto Indígena" no YouTube

youtube

Bom dia. Somos todos Um! Todos juntos em uma grande festa, a liberdade está ao alcance de todos... Vêm junto comigo!!! Que Nhanderu abençoe a toda minha família humana, e todos meus parentes. Gratidão! 💎🥷🥷💎

1 note

·

View note