#slave revolt

Text

The Death of Spartacus by Hermann Vogel

#spartacus#art#hermann vogel#ancient rome#slave revolt#slave rebellion#history#antiquity#thracian#gladiator#gladiators#roman republic#roman#romans#rebellion#revolt#uprising#europe#european#servile wars#third servile war#italy

159 notes

·

View notes

Photo

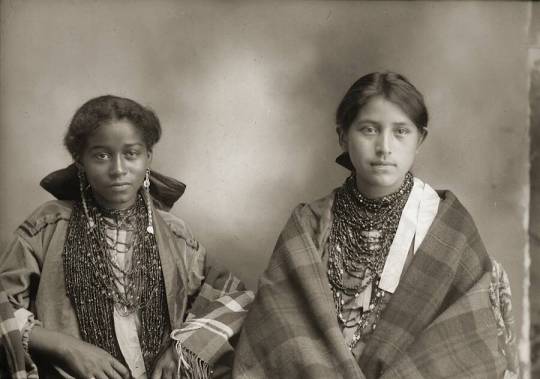

Rebel Faces: An 18th century painting containing the actual faces of rebels who participated in one of the most well documented revolts by black enslaved people.

“...The main figures in the revolt were the three brothers Wally, Mingo and Baratham.”

“... Because of the shortage of women, many of the enslaved men had wives and children living on other nearby plantations and it had become custom for these men to visit their families during their free time.”

“...warden Westphaal was given the order to increase the yield and restore order and discipline. To effectuate this, one of the measures he took was bringing down the amount of free time from two days back to one.”

Read more at https://anaelrich.com/2020/11/10/rebel-faces/

Source images: https://estherschreuder.wordpress.com/2020/04/13/terugblik-op-de-grote-suriname-tentoonstelling-de-slavendans-van-dirk-valkenburg/

#slavery#slave revolt#black history#african history#black diaspora#african diaspora#suriname#caribbean#art history

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

November 7th marks the 182nd anniversary of The Creole Ship Slave Revolt ✊🏾

The Creole was a slave ship owned by the Johnson-Eperson Co. that set sail in November 1841 carrying 135 enslaved Afrikans & shipments of tobacco from Richmond, VA to New Orleans, LA. Among them was a brotha given the name, Madison Washington - a runaway slave from Canada who was captured in VA while searching for his wife - and his wife, given the name, Susan.

On Nov 7th, Washington along with 18 other males made their move to overthrow the ship. They overpowered the crew, killing one of the slavers in the process. The ship’s wounded captain, family, & crew survived the battle. The battle was a success though not without its cost; one of the rebels was mortally wounded and succumbed to his injury. Desperate to save his own neck, the overseer on board swore he'd navigate the ship for them.

First, the rebels demanded they set sail for Liberia, Afrika; but the long distance and low food/water supplies ixneyed that possibility. One of the rebels, a brotha given the name, Ben Blacksmen, asserted that they should aim for the British controlled islands in the West Indies; word had spread of previous rebels gaining their freedom there after overtaking American slave ships. He hoped the same fortune would befall them.

They arrived in Nassau, Bahamas 2 days later. There, they were met by the harbor pilot and his men - a crew of all local Black Bahamians. The harbor pilot declared them free once ashore. Upon discovering that the Creole's captain was also mortally wounded, the American consul was notified of the revolt and demanded the arrest of Washington & all 18 rebels implicated in his death under charges of Mutany. His wife, Susan, and the other Afrikan survivors were given leave to live freely within the British boundary of the West Indies.

Some stayed in the Bahamas to start a new life, others sailed for Jamaica to do the same. Only 5 survivors chose to remain aboard the Creole set sail for New Orleans, LA to return to American Slavery ; 3 women, 1 boy, and 1 girl. It wasn't until April 16th of the next year that Washington and the other 18 rebels were freed and joined their companions on West Indian soil as freefolk.

Moreover, for their courage, unity, & nerve, 128 enslaved Afrikan Peoples gained their freedom from this day, making the Creole Slave Revolt THE most successful revolt in U.S. history.

We pour libations of water, speak their names, & offer prayers toward their elevation - especially those lost & returned to bondage.

#hoodoo#hoodoos#the hoodoo calendar#The Creole#The Creole Slave Revolt#Slave rebellion#Slave revolt#Freedom Fighters#black history

186 notes

·

View notes

Text

SLAVE REVOLT OF 1842.

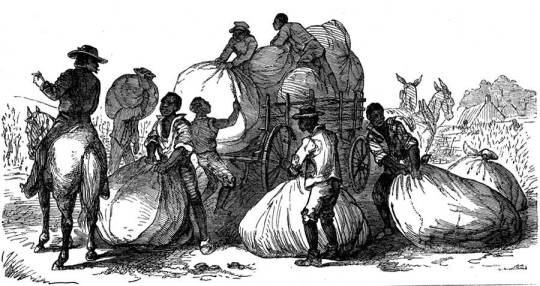

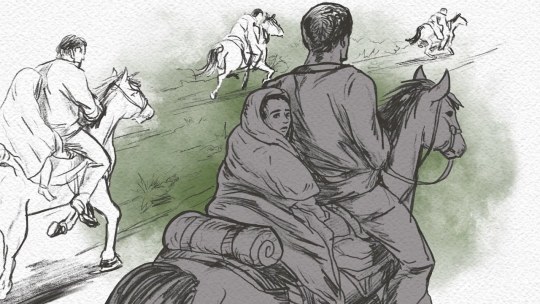

Of the Five Tribes, the Cherokees were the largest holder of Africans as chattel slaves. By 1860 the Cherokees had 4,600 slaves. Many Cherokees depended on them as a bridge to white society. Full-blood Indian slave owners relied on the Africans as English interpreters and translators. Mainly, however, enslaved persons worked on farms as laborers or in homes as maids or servants. The Cherokees feared the aspect of a slave revolt, and that is just what happened in 1842 at Webbers Falls.

On the morning of November 15 more than twenty-five slaves, mostly from the Joseph Vann plantation, revolted. They locked their masters and overseers in their homes and cabins while they slept. The slaves stole guns, horses, mules, ammunition, food, and supplies. At daybreak the group, which included men, women, and children, headed toward Mexico, where slavery was illegal. In the Creek Nation the Cherokee slaves were joined by Creek slaves, bringing the group total to more than thirty-five. The fugitives fought off and killed a couple of slave hunters in the Choctaw Nation.

The Cherokee Nation sent the Cherokee Militia, under Capt. John Drew, with eighty-seven men to catch the runaways. This expedition was authorized by the Cherokee National Council in Tahlequah on November 17, 1842. The militia caught up with the slaves seven miles north of the Red River on November 28, 1842. The tired, famished fugitives offered no resistance.

The party returned to Tahlequah on December 8, 1842. Five slaves were executed, and Joseph Vann put the majority of his rebellious slaves to work on his steamboats, which worked the Arkansas, Mississippi, and Ohio Rivers. The Cherokees blamed the incident on free, armed black Seminoles who lived in close proximity to the Cherokee slaves at Fort Gibson. On December 2, 1842, the Cherokee Nation passed a law commanding all free African Americans, except former Cherokee slaves, to leave the nation.

#african#afrakan#kemetic dreams#africans#brownskin#afrakans#brown skin#african culture#slave revolt#cherokee#asians#asian#asian americans#native americans#indigenous peoples#indigineous people#indigenous#indigenous history#Ani'-Yun'wiya#Kituwah#Tsalagi

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

Not sure if this is something that would be interesting for you to answer, but do you think there is any way a slave revolt at some point early on (or just before the civil war) could’ve established some kind of break away nation in the south? There’s so much emphasis on edge lord “what if the bad guys win!” type stuff that I’ve tried pondering this but I’m not sure if it would be possible. Do you think this could’ve been done with the right “here’s money to look the other way big northern business and political people?” Or would it always be doomed to fail because even if luck broke the revolt/revolutions way against the whole south the north would just send an army to quash it because most white northerners would still be upset white people were dieing/that part of the country was “being taken away.”

Ah, the dream of self-determination in the Black Belt...

So if we're talking sometime close to the Civil War, what we're really talking about is the John Brown scenario, whereby a state for freedmen would be established in the hill country of Appalachia. I think the problem is that, even had John Brown's raid on Harper's Ferry not gone awry so quickly (and had he had a more realistic number of soldiers), the speed at which a U.S military dominated by Southerners like Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson as well as multiple state militias mobilized to suppress the revolt speaks to how well-developed the American system of repressing slave revolts had become in the 19th century.

If we're talking earlier, then I think you do have some historical examples in the form of maroon communities like the Black Seminoles in Florida or the Great Dismal Swamp in Virginia and North Carolina, although there you're talking about runaways rather than a slave revolt. The problem as I see it is that you're combining the practical difficulties of carrying off a slave revolt - which always, always, always faced massive state repression - with the difficulties of maintaining an independent state in the face of American imperialism.

For example, the Black Seminoles were able to prosper in Florida because it was a Spanish colony and the Spanish had a policy of providing refuge to runaway slaves as a measure to destabilize the English and eventually Americans to their north - however, the existence of an armed native/freedmen state just on the other side of the Georgia state line prompted Andrew Jackson to launch a series of "punitive expeditions" that forced Spain to hand over Florida to the United States, which allowed him to bring in the U.S military to try to force the Seminoles into reservations and then try to remove them to Oklahoma. The Seminoles effectively used guerilla tactics to resist the U.S military for some time, but when they bring in 30,000 troops and use starvation tactics, they were absolutely decimated.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Baronalyg of Lalo are a race of musteline bipeds descended from ambush predators, building algae- and fish-farming communities in the murky wetlands and eventually great sailships to cross the narrow oceans of their cold world. By the time a taynifi seeker scout arrived in planetary orbit, their medieval civilization was already in disarray.

Although their scholars hadn't yet blundered into explosive powders, the race had, through a runaway accumulation effect, devised metal tools and a terrible array of elaborate social classes and kinship networks, grades of free and unfree citizenry, "chattel," pseudo-biological caste systems, and expansive maritime kingdoms and banking empires that were slaughtering one another in innumerable wars. The taynifi explorers, who never knew a conflict worse than the seasonal feuds that emerged between two quarreling clans, were horrified and intervened against the explicit advice of Sympolity dialecticians.

The resulting prolonged drama culminated in a series of peasant and slave revolts, collapsing and bringing the territory of three of Lalo's foremost empires into a single planetary federation. With the great powers subdued, many smaller states soon followed the pattern of social-revolution. The last great realm tightened its grip on neighboring lands and began to consolidate its wealth and mechanize, modeled after what its scholars learned from alien visitors of the history of less fortunate worlds. This empire, too, would fall by the wayside, and the unhappy continents of Lalo eventually joined the Sympolity.

#an unhappy world#class war#empires#fiction#furries#furry#history#lalo#lol#medieval#mustelid#paracosm#peasant revolt#planet#revolt#scifi#scifi writing#setting#slave revolt#sneak peek#space#space furries#sympolity#sympolity of mind#world#worldbuilding#writing

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Toussaint L'Ouverture is not in the Pantheon.

Somewhere along the way, I was misinformed. I had heard that France had relocated Toussaint L'Ouverture's remains to the Pantheon in Paris. But I couldn't find him in the crypt. In fact, the young steward of the gift shop didn't think that they had any display dedicated to Toussaint L'Ouverture at all. I was surprised and pleased, then, to come across the empty space where the man might have been enshrined, alongside some acknowledgement. What can be seen honoring the hero of the Haitian Revolution in the Pantheon is, importantly, an empty plinth where a tomb might lay.

In point of fact, the idea that Toussaint L'Ouverture be interred there was but a briefly entertained proposal-- see on this point Charles Forsdick's article "The Panthéon's empty plinth: commemorating slavery in contemporary France" (Atlantic Studies, 9:3, 279-297). Forsdick analyzes this absence as indicative of both France's inattention to the history of slavery, but also, symbolically, paradoxically, a gap that opens up a space of possibility (280). As Forsdick notes later in the article, in attending to various monuments devoted to slavery and abolition in France, Achille Mbembe (at a conference at the Quai Branly in Paris in May 2011) cautioned against the "museumification" of slavery, that "the entrance of the enslaved into the museum might be seen as a further act of re-enslavement" (292). Putting these two together, then, the empty plinth might be read as a sign of Toussaint L'Ouverture's marronage: a resistance to his re-incorporation into the glorious memory of French history.

For more on this issue, see not only the aforementioned article by Forsdick but also Nathan Dize's blog post, "MONUMENTAL LOUVERTURE: FRENCH/HAITIAN SITES OF MEMORY AND THE COMMEMORATION OF ABOLITION" from Age of Revolutions, April 9, 2018. https://ageofrevolutions.com/2018/04/09/monumental-louverture-french-haitian-sites-of-memory-and-the-commemoration-of-abolition/

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Currently reading

0 notes

Text

11

EXCEPTIONAL FREEDOM AND FREEDOM WITHOUT EXCEPTION

Two Views of Slave Rebellion in Jamaica

(November 5th, 2023)

Throughout the eighteenth century, all across the Americas, enslaved Africans broke from the iron grip of the slave system and launched countless direct assaults on its varied and depraved institutions. At every moment, the mountainous island of Jamaica and the thousands of enchained peoples occupying it sat at the heart of these struggles. In the familiar telling, such risings were isolated events, eventually contained or put down, and the unfree peace of plantation society was restored. What historians Mavis C. Campbell and Vincent Brown make undeniably clear is that no such peace has ever existed; not for the slaves, and not for the planters. In their accounts, following Equiano, they describe how slavery is indistinguishable from “a state of war.”[1] In fact, both authors go much further, detailing the interconnectedness of military revolution in Africa, globe-spanning competition between the warring European powers, and slavery and rebellion in the Caribbean. In each of the works under examination, the formation of a unique diaspora culture, provoked by the slavers and developed and protected by the slaves, is identified as a key factor in rebel success. Additionally, both books go to great lengths to situate Jamaican slave rebellion as world-historical phenomena; these insurrections were both influenced by their truly global context and capable of affecting economies and politics far beyond the turquoise waters of the West Indies, eventually bringing the entire colonial system to its knees. The scholarship of Campbell and Brown is separated by more than three decades and deviates sharply in methodology, ideological approach, and in each writer’s respective priorities. Nevertheless, in the divergent works of these historians, we find two views of Jamaican slave rebellion and marronage that suggest, no matter the conscious goals of the rebels, the antagonisms of slave society once laid bare by uprising and marronage could only be resolved in abolition.

Between Mavis C. Campbell’s sweeping 1988 overview of Jamaican marronage, The Maroons of Jamaica 1655-1796: A History of Resistance, Collaboration, and Betrayal and in Vincent Brown’s forcefully written 2020 book on Jamaican slave rebellion, Tacky’s Revolt: The Story of an Atlantic Slave War, we see an undeniable interpretive unity. In both books, engagement with seventeenth and eighteenth century West African politics and culture are deemed essential for developing any understanding of the slave rebellions rattling the nerves of planters across the Americas, and especially in Jamaica. The Jamaican planters expressed a perverse preference for the Africans of the Gold Coast precisely because they “often had experience in military campaigns… a superior but difficult-to-manage piece of property; like wild horses broken to domesticity, they conferred prestige upon the master.”[2] The European demand for exportable unfree labor fueled the flames of African warfare, in turn ratcheting up the production of human beings as slaves, driving down costs, and ultimately creating a devastating cycle of depredation and degradation. While European thirst for blood-soaked riches led them to plunder the Slave Coast of Africa with their right hand, they had unknowingly sowed the seeds of the colonial system’s destruction in the Caribbean with their left: “War and conquest also stimulated important cultural transformations. Not only did smaller states come to pay tribute to the expansionist states, they also learned and adopted second and third languages and new mores and customs. These wars led to a great familiarity with the family of Akan languages… the process made a common set of symbols and cultural practices widely available.”[3] Campbell establishes clearly that “most of the Maroon leaders, especially those of Jamaica, were of the Akan-speaking group.”[4] Indeed, of the countless “slave rebellions from 1760 to 1831, most… were led by the Akan-speaking group, the last one being the exception.”[5] West African military conflict is recognized across both works not only as a critical site in the production of a transatlantic slave trade, but also as the political and cultural basis for future rebellious alliances and devastating rivalries, for claims to leadership and structures for governing, and for the tactical and strategic success of any assault on slave society and its defenders. Furthermore, convergent West African cultural practices, especially in the context of the turbulent century of imperial warfare on the Slave Coast, made possible the formation of new diaspora identities and customs, in turn unlocking a rebel solidarity that eclipses the difference and separation deliberately cultivated among the slaves by the owning class. Across both books, we are shown how rebel groups coalesce around military and political leaders from the homeland, employ guerilla tactics and knowledge of the familiar landscape with profound success, and use ritual and oath-making ceremonies derived from African folkways to bind disparate and desperate peoples into a powerful historical force.

Both books also maintain that the significance of slave rebellion and marronage can only be grasped by situating the risings as one front in a broader global ecology of warfare and commerce. Jamaican slave rebellion and maroon warfare were influenced by, and capable of decisively influencing, the inter-European struggle for world supremacy. In the final years of the 17th century, the power of the Maroons was already unmistakable to the governor of Jamaica and, recognizing the “heightened successes of the ‘intestine’ enemies and the very real external threats from the French and the Spaniards,” he desperately, and futilely, sought a path to bring them to terms.[6] In fact, at many different points during the course of the eighteenth century, the Spanish, Dutch, French, and British all had to reckon with the emergent power of maroon societies in their respective colonies, both as internal threats to the stability of colonial production and as autonomous nations capable of expressing a discrete geopolitical interest, and even of threatening the very existence of the transnational institution of slavery itself. In Jamaica, the scope of the challenge posed by rebellion and marronage was undeniable and, as both books skillfully illustrate, the phenomena seriously jeopardized the economic success of the colony for the entirety of the first hundred years of British rule, making profitable settlement and production on the island virtually impossible by way of sabotage, assault, and the simple subtraction of territory from colonial control. By the first years of the new century, “the north and northeastern sectors of the island was entirely possessed by the windward Maroons… many of the marginal planters had perforce to abandon their estates.”[7] By the 1760s, the slave rebellions had decisively imperiled Britain’s position in the world economy, having “disrupted production, delayed shipping… slave rebellion created bottlenecks… Edward Long would later estimate total losses of at least £100,000 sterling ‘in ruined buildings, cane-pieces, cattle, slaves, and disbursements,’ and a similar additional amount for the cost of erecting new barracks and fortifications across the island.”[8] The persistent slave risings and resilience of the maroons did not simply threaten Jamaica’s economic viability, however. The example set by maroon autonomy and the ensuing unwavering refusal of submission to the slave order by so many of the enchained Africans undermined the entire racial and political hierarchy of the island and of the colonial system, prefiguring its overcoming and clearing a path towards its eventual dissolution.[9]

Nonetheless, the story of Jamaican slave rebellion and marronage is far from a one-dimensional tale of solidarity and liberation. The Leeward and Windward Treaties of 1738-1739 provided for the security of the oldest maroon communities on the island at the expense of much of their imagined political content; the treaties enshrined a nominal autonomy in exchange for more than a simple cessation of hostilities, cloaking the roots of dependence in the language of friendship and extracting collaboration as the high price of recognition.[10] In the latter half of the 18th century, right up until the outbreak of the Second Maroon War in 1795, the Maroons occupied an unsustainable zone of exception, existing simultaneously as the single most effective weapon of counterinsurgency available to the British colonists and as a powerful example of the feasibility and rewards of rebellion. It is here, in the treatment of this perplexing aspect of this period’s history, that both books begin to sharply differentiate themselves from one another, opening space for a conversation on their varied priorities, approaches, and methodologies.

Mavis C. Campbell, writing in 1988, set out to achieve something very different from Vincent Brown, who wrote his book some three decades later, and she attempted to do so under a very different set of circumstances. In introducing her own work, Campbell says that “there has been no historical study of the Maroons of Jamaica tracing them through Nova Scotia to Sierra Leone since R. C. Dallas’s History of the Maroons (1803),” laying out her aim of crafting a multivolume study of the maroon communities from their formation all the way through their lengthy exodus.[11] She points to several path breaking scholarly articles, most notably one written by historian Orlando Patterson in 1970, where he too “laments that ‘no adequate historical analysis yet exists on this vital episode of West Indian history. Available accounts are either too inaccurate or superficial or ideologically biased.’”[12] Campbell concludes: “The present work is an attempt to fill this gap.”[13] Given the apparent dearth of reliable secondary sources and a sensitivity to “the misconceptions, the inaccuracies, and the misinterpretations connected with this subject… materials of primary origin were therefore sought as far as they were available.”[14] At every turn, Campbell’s bibliography attests to her commitment to such a methodology, utilizing letters, journals, legal documents, and contemporary accounts to reconstruct the events of this period. Her emphasis on primary source material not only ensured that “old maps, surveyor’s diagrams and notes, songs, folklore, taboos, and the like were all mobilized in the process” of constructing a definitive history of Jamaican marronage, but also the oral histories and closely guarded ancestral knowledge of the Maroon communities themselves. Campbell made numerous visits to the remote interior of the island where she “interviewed a number of people including the colonels, majors, and captains from all the existing Maroon communities,” as well as tracking down “disparate families from disintegrated former Maroon societies.”[15]

It is likely that Campbell’s insistence on drawing almost exclusively on primary source material was a combined product of the paucity of available scholarship, her own ambition and aspirations for her book, and a stated determination to avoiding presenting her account of slave resistance from within the narrow confines of “any theoretical construct, whether Marxist, Fanonian, ‘archaic,’ ‘primitive,’ ‘millenarian,’ or even Freudian.”[16] It is clear then that no similar necessities, scarcities, or limitations affected the creation of Vincent Brown’s recent work on the same subject, despite it too overflowing with an undeniable ambition and fiery intensity, albeit one entirely its own. Brown’s work is of course densely populated with a wealth of primary material, most of which is found in Campbell’s book and much of which is likely unavoidable in any account of the era, owing both to the limited number of written first-hand accounts and the revelatory quality of particular sources, now accepted as definitive. The contemporary writings of slaveholders Bryan Edwards and Edward Long appear prominently throughout both of the works presently under examination and help to capture the sense of overwhelming terror at the precarity of their class, among many other insights. Yet, the writing in Tacky’s Revolt is exceedingly supported by a glut of secondary works on the topic, reflecting both a significant methodological divergence between the two authors and the very different scholarly context out of which Brown’s book emerges. In the decades since Campbell’s publishing her overview on the subject, research in the field of Caribbean studies has exploded, spurred on by new recognitions of the significance of decolonial and subaltern historical perspectives within academia and a parallel rise of popular interest in “history from below.” Although Jamaica still remains relatively marginal in popular consciousness and historical scholarship alike, overshadowed by the near-mythical quality of national and revolutionary histories of places like Haiti and Cuba, the island now has countless monographs dedicated to its history, many on the maroons in particular, and Campbell’s work no doubt played a small part in inaugurating this new era of historical activity. In fact, Brown cites Campbell’s Maroons early and often in his own chronicling of the events of 1760-1761, relying on her systematic overview of the topic for secondary background information and interpretive schemas. But her name is recorded unceremoniously among an unfathomably long list of recent scholarly works populating Brown’s bibliography, reinforcing our appreciation of these two book’s differences. The two authors do not only separate themselves by their methodologies however, as Brown says little else in introducing his work to the reader other than unambiguously situating his book in the black radical tradition, “following [W.E.B.] Du Bois… C.L.R. James, Eric Williams, and Walter Rodney.”[17] It is clear then that the two writers not only differ in methodologies, but also in ideological approach.

As alluded to in the above, the biggest discrepancy between these two historical works is neither methodology nor approach, but rather the historical and conceptual priorities of the authors as evinced by their treatment of certain aspects this period, and none more so than maroon collaboration with the colonial authorities. For Campbell, developing a definitive history of the Jamaican Maroons and following that thread wherever it might lead was her stated goal. So when the first Maroon Treaty is signed by Cudjoe in 1738, Campbell dutifully evaluates the event’s significance in a distinctly non-partisan style, arguing that admittedly, “one can find no ancient precedents of rebel slaves and their ex-masters signing treaties conjointly. And it is in this sense that the Treaty is historically important, that it is a triumph for the Maroons. In practical terms, though, it is another matter, for the Treaty, in effect, represents more a victory for the colonial powers than for the Maroons, who were never defeated in battle by the British… demonstrating that what the British could not gain on the battlefield, they now gained in full measure over the negotiating table.”[18] Campbell does not seek to minimize the ramifications of such a treaty nor downplay the Maroons’ agency in its formulation, pointing to a range of primary source materials that strongly indicate the willingness of the Maroons to act as slave-catchers and an irregular fighting force under British command, although she does make sure to note the illegitimacy of any treaty where one half of the signatories can neither read nor write. According to Campbell, “the Maroons, over time, had developed an inordinate sense of their own importance and a marked feeling of superiority over the other blacks of the island… the combination of ethnic particularity and earned superiority, as they perceived it, did not make for a feeling of black solidarity.”[19]

In keeping with her unwavering commitment and steadfast focus, the unprecedented slave rising of 1760-1761, known colloquially as Tacky’s Revolt, is afforded only about three pages of examination and is discussed only as the first of many successful maroon forays into the business of counterrevolution. Campbell collapses a year’s worth of exhilarating military campaigns and liberation struggles into a few lines, abruptly explaining that, “without going into all the details of the rebellion which spread throughout the island, involving the Akan-speaking group, suffice it to say that it was crushed” the following year.[20] One can practically sense the opening left by Campbell that Vincent Brown would step in to fill, thirty-two years later. For Brown, Tacky’s Revolt is practically overflowing with “political intent” and his fidelity in this work lies solely with the movement against the slave system, wherever he might find it.[21] In the early chapters of Tacky’s, Brown isolates the Jamaican Maroons as an obvious embodiment of a rebellious Coromantee diaspora subjectivity, as forming the clearest example of successful strategies and practices for slave liberation and survival, and as expressing a distinct, autonomous political interest on the island. But when the Maroons sign the treaties of 1738-1739, they are elevated and segregated as a middle class within Jamaican planter society, contradictorily engaged in the active repression of slave rebellion while passively serving as a living reminder to planter and slave alike of the possibility for insurrectionary emancipation. Brown, unlike Campbell, is writing about Jamaican slave rebellion, not the specific form of slave rebellion known as marronage, and as such, when the maroons make their infamous transition from an insurgent force to a counterinsurgent one, Brown abandons their story of ascendance up the Caribbean class hierarchy for the story of the ensuing slave wars, keeping his feet firmly planted in the mud alongside those at the lowest ranks of colonial society. The maroons subsequently appear in the pages of Tacky’s Revolt almost exclusively as a material fetter on the struggle of the enchained, as their collaboration immediately “limited the spatial horizon of the plantation slaves, diminishing their hopes of fighting their way to freedom in the interior.”[22]

Brown proceeds to narrate decades of escalating slave rebellion through the beginning of the 19th century, convincingly demonstrating an ever-increasing level of tactical sophistication and political consciousness, even detailing how “the enslaved were teaching the story of the 1760s to new arrivals… an oppositional political history taught and learned on Jamaican plantations–a radical pedagogy of the enslaved–shaped the slaves’ goals, strategies, and tactics as they rehearsed bygone battles and considered future possibilities.”[23] Campbell traces the arrested development of maroon society in the years after the successful, although temporary, extinguishing of the flames of rebellion in 1761, all the way through the Second Maroon War’s beginning in 1795. For Campbell, the tragedy of the Jamaican Maroons is not found solely or even primarily in their collaboration in the suppression of slave self-emancipation; as both authors remind us, the slaves prevail. Instead, it is that the Maroons of Jamaica, in their self-isolation and self-interest, were left behind by the movement of history, unredeemed, frozen in an amber of their own making. While “by the late eighteenth century, ethnic particularity among the slaves and the free blacks of the island would seem to have been yielding place to a kind of pan-Africanism, embracing the concerns of all blacks,” the maroons found themselves dangerously vulnerable in their solitude.[24] When talks addressing flagrant British violations of the Treaties of 1738-1739 broke down and a military assault on the Leeward Maroons began in 1795, the maroons discovered themselves to be crushingly alone. The balance of forces had decisively swung in the direction of the British government in the five decades since the last war, the Treaties and subsequent maroon collaboration being in large part responsible for creating the conditions for an explosion in productivity, population, and profits on the island, and the maroons quickly found that virtually no slaves deserted in support of their cause. Not even the Windward Maroons came to their aid; “their feeling of superiority to the other blacks finally backfired,” demonstrating the limits of Akan exclusivity and an exceptional freedom.[25] The maroons of Trelawny Town are deported as the world enters an age of unprecedented revolutionary convulsions, revolving around the insurrectionary axis of Caribbean slave revolt, reaching a crescendo in a slave war of unfathomable intensity on Jamaica in 1831, and resulting in the subsequent passage of the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833.

These two works, remarkable in their scope, their detail, and for their boldly heterodox and holistic views of Jamaican slave rebellion and marronage as genuinely global phenomena, distinguish themselves from each other in a number of important ways. Their use of sources and the academic contexts they crystalize out of present a stark contrast. Furthermore, where Campbell seeks to author a dispassioned overview on the topic, Brown unflinchingly proclaims his fidelity to a radical tradition and to the slave-warriors themselves. Naturally, such ideological differences in approach led to the telling of two very different, albeit deeply entangled, stories. However, it would seem that hovering high above such differences in methodology, approach, and focus sits a startlingly obvious connection that makes these two books far more related than the above analysis would seem to suggest: at their basest level and at their respective conceptual heights, they are both works that deal with the question of human freedom. Both works place at their core the struggle for liberation and both authors do not hesitate to declare the heroism, however flawed, of their protagonists. For Campbell, despite her tendency towards pessimism, when the Maroons avail themselves to “the best of the colonel’s venison and… the choicest of the gentleman’s port,” this is just one of many examples of their “heroic audaciousness” in the face of the disciplinary terror of the slave system.[26] And for Brown, the slave’s struggle for emancipation, proceeding even in the face of certain defeat and annihilation, should indicate to us that “military victory isn’t the only object of struggle… however degrading war itself might be, enslaved men and women fought for dignity as much as for territory.”[27] Beyond all else, these books illustrate that “power is never total. Even the most subjugated peoples have dared to plan and fight for their own forbidden aims…their struggles illuminate cracks in the edifice of racial capitalism, reminding us that another world is not only possible, another world is inevitable.”[28]

NOTES:

[1] Equiano, Olaudah. The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano; Gustavus Vassa, the African. Written by himself, Olaudah Equiano, 1789 . Literature in Context: An Open Anthology. http://anthology.lib.virginia.edu/work/Equiano/equiano-interesting-narrative.

[2] Brown, Vincent. Tacky’s Revolt: The Story of an Atlantic Slave War. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2020. 78

[3] Brown, Tacky’s Revolt, 99

[4] Campbell, Mavis C. The Maroons of Jamaica 1655-1796: A History of Resistance, Collaboration & Betrayal. Trenton, New Jersey: Africa World Press, 1990: 3

[5] Campbell, The Maroons of Jamaica, 162

[6] Campbell, The Maroons of Jamaica, 58

[7] Campbell, The Maroons of Jamaica, 59

[8] Brown, Tacky’s Revolt, 216-217

[9] “The situation had reached the point where ‘No man at [the] North side’ could be said to be master of a slave.” Campbell, The Maroons of Jamaica, 80

[10] Campbell, The Maroons of Jamaica, 130

[11] Campbell, The Maroons of Jamaica, 10

[12] Patterson, Orlando. “Slavery and Slave Revolts: A Sociohistorical Analysis of the First Maroon War, 1665-1740” In Maroon Societies, edited by Richard Price, 246-288. Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979. quoted in Campbell, The Maroons of Jamaica, 11

[13] Campbell, The Maroons of Jamaica, 11

[14] Campbell, The Maroons of Jamaica, 11

[15] Campbell, The Maroons of Jamaica, 12

[16] Campbell, The Maroons of Jamaica, 13

[17] Brown, Tacky’s Revolt, 9

[18] Campbell, The Maroons of Jamaica, 129

[19] Campbell, The Maroons of Jamaica, 131

[20] Campbell, The Maroons of Jamaica, 155

[21] Brown, Tacky’s Revolt, 131

[22] Brown, Tacky’s Revolt, 119

[23] Brown, Tacky’s Revolt, 242

[24] Campbell, The Maroons of Jamaica, 245

[25] Campbell, The Maroons of Jamaica, 245, 251

[26] Campbell, The Maroons of Jamaica, 81

[27] Brown, Tacky’s Revolt, 249

[28] Brown, Tacky’s Revolt, 15

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Brown, Vincent. Tacky’s Revolt: The Story of an Atlantic Slave War. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2020.

Campbell, Mavis C. The Maroons of Jamaica 1655-1796: A History of Resistance, Collaboration & Betrayal. Trenton, New Jersey: Africa World Press, 1990.

Equiano, Olaudah. The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano; Gustavus Vassa, the African. Written by himself, Olaudah Equiano, 1789 . Literature in Context: An Open Anthology. http://anthology.lib.virginia.edu/work/Equiano/equiano-interesting-narrative.

Patterson, Orlando. “Slavery and Slave Revolts: A Sociohistorical Analysis of the First Maroon War, 1665-1740” In Maroon Societies, edited by Richard Price, 246-288. Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979.

0 notes

Text

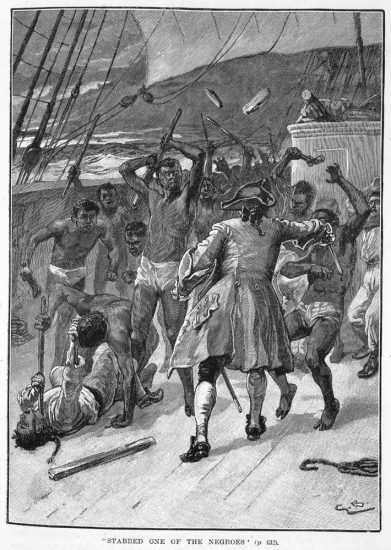

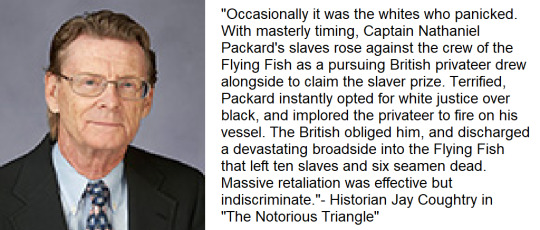

Nathaniel Packard's role in the odious slave trade

Page 158 of Coughtry's well-known 1981 book, Rhode Island and the African Slave Trade, 1700-1807 . He currently teaches at University of Nevada in Las Vegas.

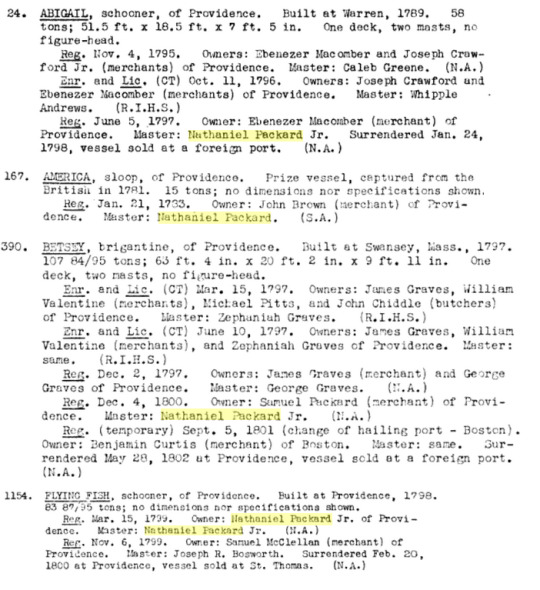

Happy Black History Month! Slave trading runs in the Packard family as I've noted on this blog before. This article was a tough one to write because there are TWO Nathaniel Packards! While I tried to ask about this on /r/AskHistorians and received no reply, [1] I am operating with the educated assumption that the slave trading shown in the 1790s was from Nathaniel Packard, Jr., not his father, of the same name, Nathaniel Sr., as he will be called herein to distinguish from his son, who was the father of Samuel. I would further like to point out that Nathaniel Jr.'s mother was part of the Sterry family, and her first cousin, Cyprian, is the same one who Samuel worked with as a slave trader! [2] Not really a coincidence if you think about it.

Some may ask, how can you be so sure that this is the right Nathaniel? What if Nathaniel Sr. was the one involved in the trade of human beings? For one, I found out that Nathaniel Sr. was born in 1730, died in 1809 while his wife "Nabby" Abigail, was born in circa 1734, and she came to live with this Nathaniel in 1752, at age 18. [3] Her death in 1819, has not been confirmed. Nathaniel Sr. had a child with Abigail in 1769 (at age 39) named Elizabeth, in 1775 (at age 45) a child named Polly, and his child Nehemiah got married in 1777. [4] Furthermore, he probably wasn't engaged in slave trading in the 1790s, due to his age. After all, in 1790, Nathaniel Sr. would have been 61, and in 1799, he would have been 70. That seems a little old to be a captain of a ship, with anecdotal evidence suggesting that captains retired between 53 and 62. [5] I wish my evidence was stronger, but I decided to go with this article anyhow.

We do know that Nathaniel, my 2nd cousin eight times removed according to FamilySearch's "View my relationship" algorithm, was a captain, participating in the Revolutionary War, and reportedly having a similar career to his son, Samuel, owning land on North Main, Howard, and Try Streets in Providence. He was a master privateer during the revolution, captain of a sloop, called the America in 1776, and had a ship he was a captain of, the Sally, captured by the Royal Navy the same year. [6] That, and the story of the America, a ship appearing in thousands of results of the Naval Documents of the American Revolution Digital Edition, is for another day, whether I choose to write about it not. The age of Nathaniel, Jr., my third cousin seven times removed, is disputed. When he died in January 27, 1807, death notices recorded his age as 25, 35, or even 55. [7] At the time of his death, he owned a house on Providence's Main Street, with two houses and other buildings, and in 1801 he is noted as a sea captain, and as marrying a woman named Miss Margaret D. Paddleford in 1800. While he would have been born in 1782 if he was 25 years old in 1807, that means he would have been 15 years old in 1797, it is more likely he was 35 or 55, meaning that he would have been born in 1772 or 1752, although I am leaning more toward his birth in 1772, around the time his other siblings were born, than 1752.

Otherwise, what is known about his personal life is sketchy at best, even having a Find A Grave entry without a photograph of his gravestone. As such, writing about his story and its interconnection with the transatlantic slave trade is important, possibly even revealing more about him as a person. Whether he was a "man of wealth" like his brother, Samuel, or not, the fact remains that uncovering his connection to the slave trade is an important part of recognizing my collective past, the history of enslaved Black people, and much more. This article tries to counter what historians Erica Caple James and Malick W. Ghachem describe as "a still powerful tendency to marginalize or suppress the stories of black lives," with narratives about the past propagated as more marketable than alternatives that try to cut against the grain of “great man” history. [8]

Often Americans see themselves as exceptional people tied together by noble ideals, but this falls apart when history is taught fully and honestly "without omitting facts or telling outright lies" as Margaret Kimberley writes in Prejudential about the racial prejudice manifested by every single US president in history. For Nathaniel, the story starts in 1797. That year, he was the captain of four ships which crossed the Atlantic. The first was the Danish Harriet, which traveled to an unspecified region of Africa, from February to December, bringing with it 53 souls, most of which were men, and selling people in Havana, Cuba. Second was the Providence schooner, Abigail, owned by Ebenezer Macomber. Unlike the Harriet, which Nathaniel owned, this ship began its journey in Rhode Island. Similarly, it traveled to an unspecified region of Africa and sold 53 enslaved peoples, mostly men, in Havana. 11 souls perished during the voyage. [9]

The same year, and into 1798, he was captain, again, of the Harriet, now owned by J de Wint. It traveled once more to Havana, this time with 57 enslaved Black people on board. [10] A pattern emerges when combining data from slave voyages: from 1797 to 1800, Nathaniel, as captain or owner, transported 314 Africans in chains to Havana, Cuba, 85 who died during the Middle Passage, and 6+6 who may have died during the voyage or have a fate unknown, while 10-15 died in a slave revolt as described later in this article. Although after 1794 U.S. slave trade to Cuba was illegal, slave traders still made slave voyages to Havana, and "profited from their own Cuban plantations". This was amidst a societal change in Cuba, which changed from underdeveloped and unpopulated small settlements, ranches, and farms in 1763 to large tobacco and sugar plantations by 1838. This was accelerated by the import of hundreds of thousands of enslaved people during that time period, estimated at 400,000 by Hubert Aimes, benefiting Cuban planters, and a decree in 1789 which allowed foreigners and Spainards to sell as many enslaved people as they wanted in Cuba's ports. Land values rose as landowners, especially those involved in sugar production, gained more power and influence as the "sugar revolution" swept the island, with a 22.8% increase in enslaved people on the island from 1774 to 1827, and the planters depended on Spanish power more than ever to protect their investments. [11]

From pages 8, 60, 136, 360 of Ship Registers and Enrollments of Providence, Rhode Island, 1773-1939, Vol. 1, 1939, I believe the America was owned by his father.

The following year, he was captain, and owner, of the Flying Fish, a schooner from Providence. He co-owned the ship with Sam McClellan. This ship went to an unspecified part of Africa and sold 76 enslaved people in Havana, but they resisted with a "slave insurrection" noted. However, a voyage earlier that year with the same ship was more deadly, as almost half of enslaved people aboard died during the Middle Passage! [12] The ship had a tonnage of 85 tons, higher than some other ships.

It was then that Nathaniel would experience a revolt on the Flying Fish, which was transporting enslaved people. Ten of those on board would revolt, noted in the Newport Mercury. 10-15 enslaved people and 4-5 crewmen were killed in a failed revolt on this private armed vessel. While some sources said this was in 1800, the revolt was in late 1799, in actuality. [13] Coughtry, who I quoted at the beginning of this article, wrote:

Occasionally it was the whites who panicked. With masterly timing, Captain Nathaniel Packard's slaves rose against the crew of the Flying Fish as a pursuing British privateer drew alongside to claim the slaver prize. Terrified, Packard instantly opted for white justice over black, and implored the privateer to fire on his vessel. The British obliged him, and discharged a devastating broadside into the Flying Fish that left ten slaves and six seamen dead. Massive retaliation was effective but indiscriminate. On the few vessels that did experience slave revolts, captors and captives alike paid a high price for the latter's courage.

Nathaniel would be captain of the Betsey in 1800, Eliza in 1803, Minerva in 1794, Juno in 1805, and Dolphin in 1792. By 1800, he was married to Margaret Downs Paddleford, the daughter of well-off physician named Philip Paddleford and Margaret Downe. By the time they married, her mother had been dead or twenty years and Philip had married another woman, Elizabeth Macomber. The same year, friends of a 10-year-old Black male child, Peter Sharp, would testify against Nathaniel to the Providence Council. [14] In later years, in 1801 to 1802, he would be captain of the aforementioned slave ship, the Betsey. Only 94 of the enslaved people made it to the Americas and were sold in Havana, with 24 people perishing during the voyage across the Atlantic. [15] He did this while professing his religious ferment in his last will and testament, bequeathing money and personal property to his children and Margaret:

Will of Nathaniel in 1806, probated in 1807, noting his children and wife. [16]

Nathaniel was creating generational wealth, something which came in part from the trading of enslaved Black people. As Mary Elliott, curator on American slavery for The Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture noted in July 2019, some 12.5 million men, women and children of African descent were forced into the transatlantic slave trade, with the "sale of their bodies and the product of their labor [bringing]...the Atlantic world into being...[with] freedom was limited to maintain the enterprise of slavery and ensure power." She further said that Africans were forcibly migrated through the Middle Passage while the slave trade provided political power, wealth, and social standing for individuals, colonies, nation-states, and the church, while noting that enslaved black people "came from regions and ethnic groups throughout Africa." Although the U.S. international slave trade was made illegal in 1808, domestic slave trade increased, even as illegal slave trading continued internationally, with people such as my ancestor, Captain Samuel Packard, involved in it. What she next is significant to keep in mind:

Slavery affected everyone, from textile workers, bankers and ship builders in the North; to the elite planter class, working-class slave catchers and slave dealers in the South; to the yeoman farmers and poor white people who could not compete against free labor.

Furthermore, slavery itself was built and sustained by "black labor and black wombs", maintaining the economic system itself, with prosperity depending upon the "continuous flow of enslaved bodies", while a campaign of violence was waged against black people that "would rob them of an incalculable amount of wealth" following the end of Reconstruction in the 1870s. [17] Nathaniel, as well as his family, was part of this exploitation and it something that should be recognized, not hidden away or covered up as some people like to do with this history.

Notes

[1] On August 21, I asked "What age did sea captains, in the 18th century, retire?", adding in part "my common sense tells me he wouldn't be sailing a ship at that age and some scattered sources about this, when I did a quick search, did point to that." Unfortunately, a moderator removed the question for asking "basic facts," to which I wasn't happy (obviously), and was directed to another askhistorians thread. I posted a similar version of the question there, asking "Does anyone know what age did sea captains, in the 18th century (more specifically 1790s-early 1800s), retire?" And, just as I expected, I received NO reply. The lesson I took away from this is that you can't trust these forums to respond to you, and sometimes you just have to do the research yourself, with no help from anyone else, sad to say.

[2] Using this family relationship chart and explanatory post, I determined that Cyprian is the son of her uncle. This is because the brother of Abigail's father, Robert (1711-1789), was a man named Cyprian (1707-1772), who had a son named Cyprian (1752-1824), the one, and same, as the slave trader. So, that's the connection. Abigail and Nathaniel later had a daughter named Abigail, who married in 1784, and was named after her. In another interesting antecote, it appears that John Congdon, the father-in-law of 3rd cousin 7x removed, and the father of Abigail, the wife of Captain Samuel Packard, may have been a slave trader as well, as a Congdon is listed as captain of an unnamed slave trading vessel in 1762 and the Speedwell schooner from 1764 to 1765.

[3] Knowles, James D. Memoir of Roger Williams, the founder of the state of Rhode-Island (Boston: Lincoln, Edmands & Co., 1834), 432-433. Reprinted in "Notes on the Grave of Roger Williams," Apr. 20, 1907, Book Notes, Vol. 24, No. 8, p. 59. Relevant quote, reprinted from a letter in The American in 1819: "I am induced to lay before the public the following facts, communicated to me by the late Capt. Nathaniel Packard, of this town, about the year 1808...Captain Packard was son of Fearnot Packard, who lived in a small house, standing a little south of the house of Philip Allen, Esq. and about fifty feet south of the noted spring. In this house Captain Packard was born, in 1730, and died in 1809, being seventy-nine years old...Mrs. Nabby [Abigail] Packard, widow of Captain Packard, who is eighty-five years old, told me, this day, that her late husband had often mentioned the above facts to her; and his daughter, Miss Mary Packard, states, that her father often told her the same... Mrs. Nabby Packard, Nathaniel Packard's widow, told me this day, that she came to live where she now lives, when she was eighteen years old, which was sixty-seven years ago."

[4] "Rhode Island Town Births Index, 1639-1932", database, FamilySearch, 4 November 2020, Nathaniel Packard in entry for Elizabeth Sterry, 1857; "Rhode Island, Town Clerk, Vital and Town Records, 1630-1945," database with images, FamilySearch, 4 November 2020), Nathaniel Packard in entry for Elisabeth Sterry, 22 Nov 1857; citing Death, Providence, Providence, Rhode Island, United States, various city archives, Rhode Island; FHL microfilm 2,022,703; "Rhode Island, Town Clerk, Vital and Town Records, 1630-1945," database with images, FamilySearch, 4 November 2020, Nathanul Packard in entry for Polly Packard, 17 Dec 1858; citing Death, Providence, Providence, Rhode Island, United States, various city archives, Rhode Island; FHL microfilm 2,022,703; "Rhode Island Town Births Index, 1639-1932", database, FamilySearch, 4 November 2020), Nathaniel Packard in entry for Polly Packard, 1858; "Rhode Island Marriages, 1724-1916", database, FamilySearch, 22 January 2020), Nathaniel Packard in entry for Nehemiah Rhoads Packard, 1777.

[5] I'm referring to a 1931 New York Times story titled "37 YEARS AT SEA, CAPTAIN TO RETIRE; SHIP MASTER TO RETIRE" (noted a captain retiring at age 55), a U.S. Navy webpage saying you retire after age 62,and the life of Captain Edward Penniman (1831-1913) described by the National Park Service.

[6] White Jr., George Wylie. “A Rhode Islander Goes West to Indiana (1817-1818),” Rhode Island History, Vol I, No. 1, January 1942, p. 22; Lewisohn, Florence, The American Revolution's Second Front: Persons & Places Involved in the Danish West Indies & Some Other West Indian Islands (University of Texas, 1976), p. 12; "Captain Nathaniel Packard's Account Against the Rhode Island Sloop America, September 30, 1776," American Theatre from September 1, 1776, to October 31, 1776, Vol. 6, via Naval Documents of the American Revolution Digital Edition; "Owners of the Rhode Island Sloop America to Captain Nathaniel Packard, August 21, 1776," American Theatre from September 1, 1776, to October 31, 1776, Vol. 6, via Naval Documents of the American Revolution Digital Edition; "Lists of Prizes Condemned in the Vice Admiralty Court of Antigua, January 14, 1778," American Theatre from January 1, 1778 to March 31, 1778, Vol. 11, via Naval Documents of the American Revolution Digital Edition; "Governor Nicholas Cooke and John Jenckes to Captain Nathaniel Packard, February 3, 1776," American Theatre from January 1, 1776, to February 18, 1776, Vol. 3, via Naval Documents of the American Revolution Digital Edition; "Prizes Taken by British Ships in the Windward Islands, May 1, 1776," American Theatre from April 18, 1776, to May 8, 1776, Vol. 4, via Naval Documents of the American Revolution Digital Edition; "Journal of H.M. Sloop Pomona, Captain William Young, March 11, 1776," American Theatre from April 18, 1776, to May 8, 1776, Vol. 4, via Naval Documents of the American Revolution Digital Edition; "Potential Suspects," Gaspee Virtual Archives, accessed September 26, 2021. He was also said, according to the 1774 RI Colonial Census, to be living in Providence with his family, that year, and have tracts of Land in Providence as early as 1762. As a note on his FamilySearch profile proposes, he may have been involved in the Gaspee Affair in 1772.

[7] According to a note on his FamilySearch profile, a death notice was published in Providence Phoenix (Providence, R.I.), 31 Jan 1807, p. 3, col. 2, has an unclear date of either he was age 25, 35, or 55, with a reprint in the Columbian Centinel (Boston, Mass.), 4 Feb 1807, p. 2, giving his age as 25, the Salem Register (Salem, Mass.), 5 Feb 1807, p. 3, col. 3, giving his age as 35, the Independent Chronicle (Boston, Mass.), 5 Feb 1807, p. 3, giving his age as 25, and Newburyport Herald (Newburyport, Mass.), 6 Feb 1807, p. 3, col. 2, giving his age as 25. See the note for further sources of information beyond this sentence, mainly abstracting from probate records. He was also living in Providence in 1800, according to "United States Census, 1800," database with images, FamilySearch, accessed 26 September 2021, Nathanies Packard Jr, Providence, Providence, Rhode Island, United States; citing p. 211, NARA microfilm publication M32, (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.), roll 45; FHL microfilm 218,680, and his marriage is noted here: "Massachusetts Marriages, 1695-1910, 1921-1924", database, FamilySearch, 28 July 2021, Nathaniel Packard, 1800.

[8] Erica Caple James and Malick W. Ghachem, "Black Histories Matter," Perspectives of History, Sept. 1, 2015, accessed September 26, 2021.

[9] Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade - Database, "Voyage 35224, Harriet (1797)", with entry also in Peoples of the Historical Slave Trade database and another entry here; Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade - Database, "Voyage 36677, Abigail (1797)", with entry also in Peoples of the Historical Slave Trade database.

[10] Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade - Database, "Voyage 35225, Harriet (1798)", with entry also in Peoples of the Historical Slave Trade database.

[11] Franklin Knight, "The Transformation of Cuban Agriculture, 1763-1838" in Caribbean Slave Society and Economy: A Student Reader (ed. Hilary Beckles and Verene Shepherd, New York: The New Press, 1991), 69, 72, 74-78.

[12] Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade - Database, "Voyage 36727, Flying Fish (1799)", with entry also in Peoples of the Historical Slave Trade database; "Voyage 36726, Flying Fish (1799)", with entry also in Peoples of the Historical Slave Trade database and here.

[13] Eric Robert Taylor, If We Must Die: Shipboard Insurrections in the Era of the Atlantic Slave Trade, Vol. 38, 2009, p. 209; Naval Documents Related to the Quasi-war Between the United States and France: From Dec. 1800 to Dec. 1801, United States. Office of Naval Records and Library, 1935, p 397.

[14] U.S., Newspaper Extractions from the Northeast, 1704-1930 for Margaret D Paddleford, Massachusetts, Columbian Centinel, Marriage, Nabor-Ryonson, :Newspapers and Periodicals. American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts; Massachusetts, U.S., Compiled Birth, Marriage, and Death Records, 1700-1850 for Margaret Downs Padelford, Taunton; Massachusetts, U.S., Town Marriage Records, 1620-1850, Vital Records of Taunton, Margaret Downs of T. and Nathaniel Packard of Providence, Feb. 12, 1800, in T. Intention not recorded; Massachusetts, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1635-1991 for Philip Padelford, Bristol, Probate Records, Padeford, James - Paine, Sarah, pages 144 and 145; via page 11 of Descendants of Jonathan Padelford, 1628-1858 chart, where it almost looks like Margaret Brown; Children Bound to Labor: The Pauper Apprentice System in Early America, 2011, p. 43.

[15] Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade - Database, "Voyage 36753, Betsey (1802)", with entry also in Peoples of the Historical Slave Trade database.

[16] Will of Nathaniel Packard, 1807, Rhode Island, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1582-1932 for Nathaniel Packard, Providence, Wills and Index, Vol 10-11 1805-1815, Rhode Island, District and Probate Courts.

[17] Of note is what one writer, Nancy Isenberg, argued: that Americans believe in social mobility, but have a "long list of slurs and of terms" for people, and noted that "the discussion of class throughout our history has forced on the centrality of land and land ownership, as well as what I call breeds, or breeding", concepts which come from the British, and notes that another English idea is that "the wealth and the strength of the nation are based on the size of its population" and goes onto say that the English were focused on bloodlines, lineage, and pedigree, even more on inheritance, while saying that class has a specific geography with class-zoned neighborhoods, and stated that convincing people that poor whites are enemies of black Americans is a way to divide people, concluding that "not only are we not a post-racial society, we are certainly not a post-class society."

Note: This was originally posted on Feb. 6, 2023 on the main Packed with Packards WordPress blog (it can also be found on the Wayback Machine here). My research is still ongoing, so some conclusions in this piece may change in the future.

© 2023 Burkely Hermann. All rights reserved.

#packards#slave trade#slavery#enslaved people#black history matters#black lives matter#rhode island#providence#18th century#19th century#havana#cuba#spain#slave revolt#slave rebellion#middle passage#slaveowners#reconstruction#nancy isenberg

0 notes

Text

1839-Amistad revolt

Twenty miles off the coast of Cuba, 53 kidnapped Africans led by Joseph Cinqué mutiny and take over the slave ship Amistad.

The crew of La Amistad, lacking purpose-built slave quarters, placed half the captives in the main hold and the other half on deck. The captives were relatively free to move about, which aided their revolt and commandeering of the vessel. In the main hold below decks, the captives found a rusty file and sawed through their manacles. On about July 1, once free, the men below quickly went up on deck. Armed with machete-like cane knives, they attacked the crew, successfully gaining control of the ship, under the leadership of Sengbe Pieh (later known in the United States as Joseph Cinqué). They killed the captain and Ferrer's mulatto/slave ships cook Selestino Ferrers of the ship;[8] two slaves also died, two sailors Manuel Pagilla and Jacinto escaped in a small boat. Ferrer's slave/mulatto cabin boy Antonio [9] was spared as was José Ruiz and Pedro Montes, the two owners of the slaves, so that they could guide the ship back to Africa.[3][6][7] While the Mende demanded to be returned home, the navigator Montes deceived them about the course, maneuvering the ship north along the North American coast until they reached the eastern tip of Long Island, New York.

0 notes

Text

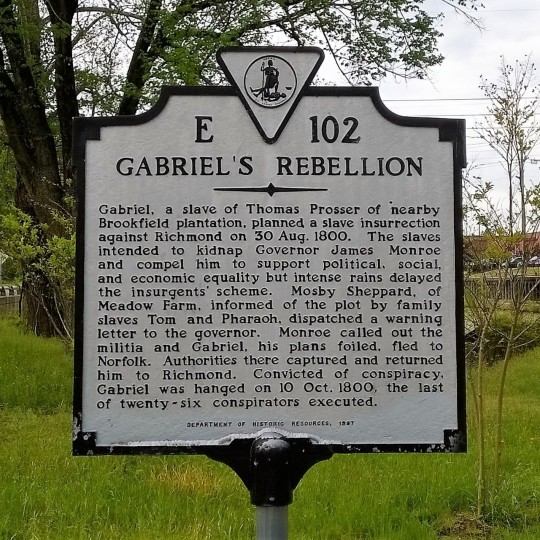

August 30th marks the 223rd anniversary of the Gabriel's Conspiracy of 1800; a most collaborative effort that would unite enslaved folks, "freefolk", First Nations, poor Whites, and the French army✊🏾

Gabriel "Prosser" was born enslaved on Thomas Prosser's tobacco plantation in Richmond, Virginia,1776. Even as a child, Brother Gabriel was unique; he was considered to be unusually intelligent & unusually large in size. By the age 20, he was 6ft feet 2-3in tall & enormously strong from his years of apprentcing as a Blacksmith. This instinctively compelled even older enslaved folks to view him as a leader.

He and his brother, Solomon, were hired out as Blacksmiths around Richmond, VA, which not only allowed them access to money and a small measure of traveling freedom, but exposed them to labor and leisure time with other hired out workers - from enslaved folk, "freefolk", to white laborers. At the time, talk of the American Revolution, Saint Domingue's uprising, White Workings Class, the small measures of success held by "freefolk", the contempt of the enslaved, and the white merchants routinely cheating them all out of fair pay was prominent. These experiences shaped his mind and molded his ambitions toward revolutionary freedom and prosperity.

Brother Gabriel believed that if enslaved folk rose up against the oppressors, then poor Whites and other oppressed communities would be inspired and join them. His plan was simple: seize Capitol Square in Richmond, take Governor James Monroe as a hostage as a bargaining tool against city authorities. He planned to send an ally to Catawbas Nation to persuade them to join them. It was also believed that he'd hoped to sway members of a French army that had landed nearby would assist them.

Gabriel conveyed his plan to his brother Solomon and another of Prosser Jr.'s slaves. From there they began building his army. They recruited only men as soldiers; majority slaves, "freefolk", and a few poor Whites. Others were recruited abolitionists, French militants, and other strong minded rebels as leaders. They traveled from Richmond to nearby towns throughout Virginia to build their army and allegiances. They amassed an armory of weapons. They began hammering swords out of scythes and molding bullets out of iron.

By August of 1800, Gabriel's army was ready. His plan now included overtaking the town of Norfolk and Petersburg by the conspirators living there. Gabriel announced that they would move come nightfall on Saturday, August 30th. As his lieutenants delivered the news to outlying areas, a rumor of insurrection surfaced among Whites in Richmond, which went largely ignored by their Governor. On August 30th, a torrential downpour flooded the region in what had been described as, "the most terrible thunderstorm every witnessed in the state of Virginia". Though a handful of men gathered at the appointed meeting spot, it became clear that the quickly rising water would make key roads and bridges impassable. Gabriel decided to postpone until Sunday evening, August 31st. To our great disappointment, before they had a chance to carry out their plan, enslaved conspirators in two different locations cracked under pressure and confessed their "masters". Thus, the Governor was alerted and white patrols, later joined by the state militia, began roaming the countryside searching for Gabriel and his army.

Soon, Gabriel and one of his leutenants disappeared. Others eluded capture for several days, but by September 9th, almost 30 slaves were jailed awaiting trial. Gabriel's brother, Solomon, was given up by one of their closest conspiratorsfrom the same Prossner plantation in exchange for a pardon. On Sept 14th Gabriel swam to a schooner called Mary on the James River to see a White man named Richardson Taylor who was a former overseer with a change of heart toward Slavery. He attempted to take Gabriel to freedom, but was thwarted by 1 of 2 Black folk on board who outted him in hopes of receiving the $300 reward for his capture, which would ensure his own freedom. Gabriel was handed over to authorities in Norfolk, VA while their informant was given a mere $50 and remained enslaved.

On October 6th, Gabriel was put on trial and set to be executed the next day. The only time he spoke during his trail was to request a stay until October 10th to be executed alongside his brothers in arms on the date that was set for them. On October 10th, he was executed alone by hanging. By the end of 2mo long trials, 26 conspirators were executed and 1 died by suicide in custody. Virginia paid over $8900 to slaveholders for the executed slaves.

This undoubtedly would have been the most far-reaching slave revolt in U.S. History. The first time in recorded U.S. history when the enslaved, "freefolk", First Nations, and even poor Whites, were united under the banner of freedom. We can only imagine how this would've reshaped the history of Virginia let alone the course of Transatlantic Slavery in the U.S.

We pour libations of water, blow tobacco smoke, speak their names, & offer prayers toward the elevation of Brother Gabriel, his lieutenants, and ally conspirators who risked it ALL for our freedom and prosperity for generations to come.

#gabriel Prossner#gabriels conspiracy#hoodoo#atr#the hoodoo calendar#hoodoos#black august#slave rebellion#Virginia#slave revolt#black power

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Tangled Mercy: A Novel

A Tangled Mercy: A Novel

Known for its history and beauty, Charleston, South Carolina, is one of my favorite places in the United States. My favorite Charlestonian of all time (besides my wife) is Denmark Vesey, who led a failed slave revolt in 1822. He left my church in Charleston (Second Presbyterian Church) to help found Mother Emmanuel AME Church – the same church that hosted a horrific Bible study in 2015 that ended…

View On WordPress

0 notes