#enslaved people

Text

Petticoat attributed to an enslaved seamstress known as Old Aunt Sarah, 1840.

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

400+ years of extreme exploitation.

306 notes

·

View notes

Text

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

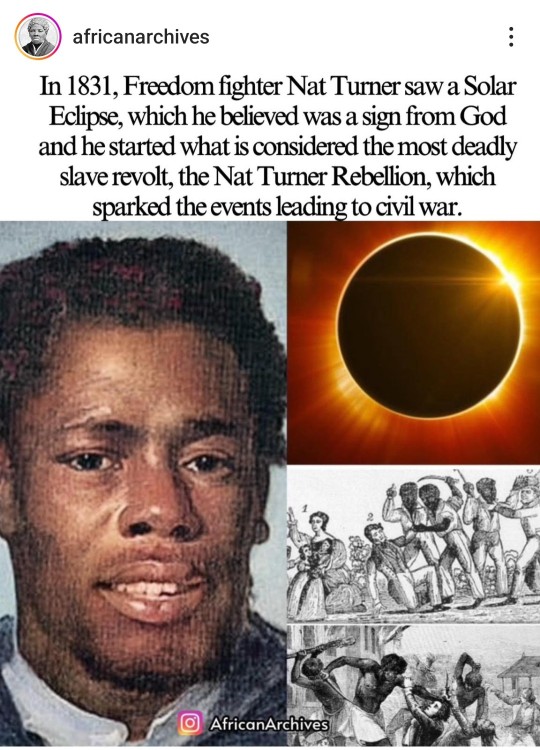

Around early 1828, Nat Turner was convinced that he "was ordained for some great purpose in the hands of the Almighty". A solar eclipse and an unusual atmospheric event and is what inspired Nat Turner to start his insurrection, which began on August 21, 1831.

Nat Turner believed God was showing him a sign by putting a black man hand over the Sun. Its been known for thousands of years solar eclipse give off energy.

On August 21, he began the rebellion with a few trusted fellow enslaved men. The rebels traveled from house to house, freeing enslaved people and killing their White owners.

Turner's rebellion was suppressed within two days and he was captured October 30. On November 5, he was convicted and sentenced to death and was hanged November 11, 1831.

The state executed 56 other Black men suspected of being involved in the uprising and another 200 Black people, most of whom had nothing to do with the uprising, were beaten, tortured, and murdered by angry White mobs.

The Virginia General Assembly passed new laws making it unlawful to teach enslaved or free Black or Mulatto (mixed) people to read or write and restricting Black people from holding religious meetings without the presence of a licensed White minister.

#Nat Turner#solar eclipse#insurrection#rebellion#enslaved people#White owners#suppression#capture#conviction#death sentence#execution#Virginia General Assembly#laws#literacy#religious gatherings#racial oppression

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bill of Sale for Person Named George

Record Group 21: Records of District Courts of the United States Series: Law, Equity, and Criminal Case Files

Know all men by these presents, That I, Albert G. Ewing of the county of Davidson and the state of Tennessee have this day, for and in consideration of five hundred dollars, to me in hand paid by Joseph Woods and John Stacker, Trustees for Samuel Vanleer, his wife and children, under the will of Bernard Vanleer, now recorded in the office of the Davidson county court, state of Tennessee, bargained and sold unto said Trustees, a certain negro boy named George aged about seventeen years; which said slave I warrant to be sound and healthy; and I also will warrant the right and title of said slave, unto said Trustees, their heirs, executors, &c &c. and that said negro boy George is a slave for life. Witness my hand and seal, this sixth day of November 1833. Frederick Bradford Nov. 6. 1833. A.G. Ewing Orville Ewing

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

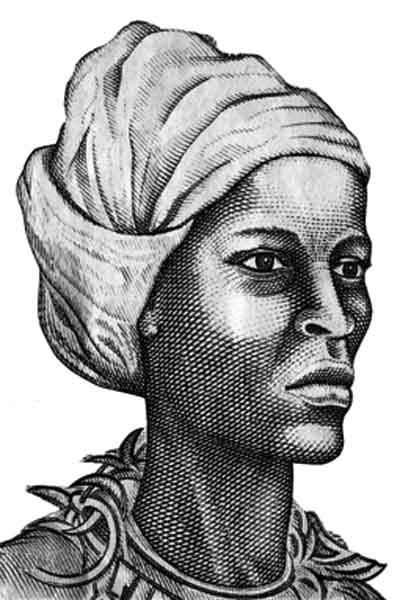

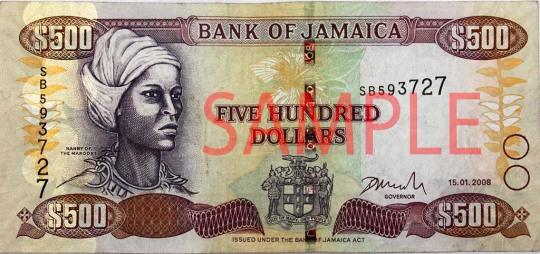

Queen Nanny of the Maroons

Nanny, known as Granny Nanny, Grandy Nanny, and Queen Nanny was a Maroon leader and Obeah woman in Jamaica during the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Maroons were slaves in the Americas who escaped and formed independent settlements. Nanny herself was an escaped slave who had been shipped from Western Africa. It has been widely accepted that she came from the Ashanti tribe of present-day Ghana.

Nanny and her four brothers (all of whom became Maroon leaders) were sold into slavery and later escaped from their plantations into the mountains and jungles that still make up a large proportion of Jamaica. Nanny and one brother, Quao, founded a village in the Blue Mountains, on the Eastern (or Windward) side of Jamaica, which became known as Nanny Town. Nanny has been described as a practitioner of Obeah, a term used in the Caribbean to describe folk magic and religion based on West African influences.

Nanny Town, placed as …[Read more here]

Source: BlackPast.org, Wikipedia

Visit www.attawellsummer.com/forthosebefore to learn more about Black history.

Need a freelance graphic designer or illustrator? Send me an email.

#Nanny Town#Jamaica#Caribbean#Queen Nanny#Maroons#Ashanti people#Ghana#west Africa#Obeah#African Diaspora#Moore Town#Windward Maroons#slavery#slaves#enslaved people#Black history#For Those Before

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Her name was Julia Chinn, and her role in Richard Mentor Johnson’s life caused a furor when the Kentucky Democrat was chosen as Martin Van Buren’s running mate in 1836.

She was born enslaved and remained that way her entire life, even after she became Richard Mentor Johnson’s “bride.”

Johnson, a Kentucky congressman who eventually became the nation’s ninth vice president in 1837, couldn’t legally marry Julia Chinn. Instead the couple exchanged vows at a local church with a wedding celebration organized by the enslaved people at his family’s plantation in Great Crossing, according to Miriam Biskin, who wrote about Chinn decades ago.

Chinn died nearly four years before Johnson took office. But because of controversy over her, Johnson is the only vice president in American history who failed to receive enough electoral votes to be elected. The Senate voted him into office.

The couple’s story is complicated and fraught, historians say. As an enslaved woman, Chinn could not consent to a relationship, and there’s no record of how she regarded him. Though she wrote to Johnson during his lengthy absences from Kentucky, the letters didn’t survive.

Amrita Chakrabarti Myers, who is working on a book about Chinn, wrote about the hurdles in a blog post for the Association of Black Women Historians.

“While doing my research, I was struck by how Julia had been erased from the history books,” wrote Myers, a history professor at Indiana University. “Nobody knew who she was. The truth is that Julia (and Richard) are both victims of legacies of enslavement, interracial sex, and silence around black women’s histories.”

youtube

Johnson’s life is far better documented.

He was elected as a Democrat to the state legislature in 1802 and to Congress in 1806. The folksy, handsome Kentuckian gained a reputation as a champion of the common man.

Back home in Great Crossing, he fathered a child with a local seamstress, but didn’t marry her when his parents objected, according to the biography “The Life and Times of Colonel Richard M. Johnson of Kentucky.” Then, in about 1811, Johnson, 31, turned to Chinn, 21, who had been enslaved at Blue Spring Plantation since childhood.

Johnson called Chinn “my bride.” His “great pleasure was to sit by the fireplace and listen to Julia as she played on the pianoforte,” Biskin wrote in her account.

The couple soon had two daughters, Imogene and Adaline. Johnson gave his daughters his last name and openly raised them as his children.

Johnson became a national hero during the War of 1812. At the Battle of the Thames in Canada, he led a horseback attack on the British and their Native American allies. He was shot five times but kept fighting. During the battle, the Shawnee chief Tecumseh was killed.

In 1819, “Colonel Dick” was elected to the U.S. Senate. When he was away in Washington for long periods, he left Chinn in charge of the 2,000-acre plantation and told his White employees that they should “act with the same propriety as if I were home.”

Chinn’s status was unique.

While enslaved women wore simple cotton dresses, Chinn’s wardrobe “included fancy dresses that turned heads when Richard hosted parties,” Christina Snyder wrote in her book “Great Crossings: Indians, Settlers & Slaves in the Age of Jackson.”

In 1825, Chinn and Johnson hosted the Marquis de Lafayette during his return to America.

In the mid-1820s, Johnson opened on his plantation the Choctaw Academy, a federally funded boarding school for Native Americans. He hired a local Baptist minister as director. Chinn ran the academy’s medical ward.

“Julia is as good as one half the physicians, where the complaint is not dangerous,” Johnson wrote in a letter. He paid the academy’s director extra to educate their daughters “for a future as free women.”

Johnson tried to advance his daughters in local society, and both would later marry White men. But when he spoke at a local July Fourth celebration, the Lexington Observer reported, prominent White citizens wouldn’t let Adaline sit with them in the pavilion. Johnson sent his daughter to his carriage, rushed through his speech and then angrily drove away.

When Johnson’s father died, he willed ownership of Chinn to his son. He never freed his common-law wife.

“Whatever power Chinn had was dependent on the will and the whims of a White man who legally owned her,” Snyder wrote.

Then, in 1833, Chinn died of cholera. It’s unclear where she is buried.

Johnson went on to even greater national prominence.

In 1836, President Andrew Jackson backed Vice President Martin Van Buren as his successor. At Jackson’s urging, Van Buren — a fancy dresser who had never fought in war — picked war hero Johnson as his running mate. Nobody knew how the Shawnees’ chief was slain in the War of 1812, but Johnson’s campaign slogan was, “Rumpsey, Dumpsey. Johnson Killed Tecumseh.”

Johnson’s relationship with Chinn became a campaign issue. Southern newspapers denounced him as “the great Amalgamationist.” A mocking cartoon showed a distraught Johnson with a hand over his face bewailing “the scurrilous attacks on the Mother of my Children.”

This political cartoon was a racist attack on Johnson because of his relationship with Julia Chinn. (Library of Congress)

Van Buren won the election, but Johnson’s 147 electoral votes were one short of what he needed to be elected. Virginia’s electors refused to vote for him. It was the only time Congress chose a vice president.

When Van Buren ran for reelection in 1840, Democrats declined to nominate Johnson at their Baltimore convention. It is the only time a party didn’t pick any vice-presidential candidate. The spelling-challenged Jackson warned that Johnson would be a “dead wait” on the ticket.

“Old Dick” still ended up being the leading choice and campaigned around the country wearing his trademark red vest. But Van Buren lost to Johnson’s former commanding officer, Gen. William Henry Harrison.

Johnson never remarried, but he reportedly had sexual relationships with other enslaved women who couldn’t consent to them.

The former vice president won a final election to the Kentucky legislature in 1850, but died a short time later at the age of 70.

His brothers laid claim to his estate at the expense of his surviving daughter, Imogene, who was married to a White man named Daniel Pence.

“At some point in the early twentieth century,” Myers wrote, “perhaps because of heightened fears of racism during the Jim Crow era, members of Imogene Johnson Pence’s line, already living as white people, chose to stop telling their children that they were descended from Richard Mentor Johnson … and his black wife. It wasn’t until the late 20th century that younger Pences, by then already in their 40s, 50s, and 60s, began discovering the truth of their heritage.”

#He Became the Nation’s Ninth Vice President. She Was His Enslaved Wife.#enslaved people#Richard Johnson#Julia Chinn#Youtube

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Favoring the British Crown: enslaved Blacks, Annapolis, and the run to freedom [Part 1]

This watercolour sketch by Captain William Booth, Corps of Engineers, is the earliest known image of an African Nova Scotian. He was probably a resident of Birchtown. According to Booth's description of Birchtown, fishing was the chief occupation for "these poor, but really spirited people." Those who could not get into the fishery worked as labourers, clearing land by the acre, cutting cordwood for fires, and hunting in season. Image and caption are courtesy of the Nova Scotia Archives, used within fair use limits of copyright law.

In 1777, William Keeling, a 34 year old Black man ran away from Grumbelly Keeling, a slaveowner on the Eastern Shore of Virginia, which covers a very small area. [1] The Keelings were an old maritime family within Princess Anne County. William, and possibly his wife Pindar, a "stout wench" as the British described her, would be evacuated July 1783 on the Clinton ship from New York with British troops and other supporters of the British Crown ("Loyalists") likely to somewhere in Canada. [2] They were not the only ones. This article does not advocate for the "loyalist" point of view, but rather just tells the story of Blacks who joined the British Crown in a quest to gain more freedom from their bondage rather than the revolutionary cause. [3]

Reprinted from my History Hermann WordPress blog.

Black families go to freedom

There were a number of other Black families that left the newly independent colonies looking for freedom. Many of these individuals, described by slaveowners as "runaways," had fled to British lines hoping for Freedom. Perhaps they saw the colonies as a “land of black slavery and white opportunity,” as Alan Taylor put it, seeing the British Crown as their best hope of freedom. [4] After all, slavery was legal in every colony, up to the 1775, and continuing throughout the war, even as it was discouraged in Massachusetts after the Quock Walker decision in 1783. They likely saw the Patriots preaching for liberty and freedom as hypocrites, with some of the well-off individuals espousing these ideals owning many humans in bondage.

There were 26 other Black families who passed through Annapolis on their way north to Nova Scotia to start a new life. When they passed through the town, they saw as James Thatcher, a Surgeon of the Continental Army described it on August 11, 1781, "the metropolis of Maryland, is situated on the western shore at the mouth of the river Severn, where it falls into the bay."

The Black families ranged from 2 to 4 people. Their former slavemasters were mainly concentrated in Portsmouth, Nansemond, Crane Island, Princess Ann/Anne County, and Norfolk, all within Virginia, as the below chart shows:

Not included in this chart, made using the ChartGo program, and data from Black Loyalist, are those slaveowners whose location could not be determined or those in Abbaco, a place which could not be located. [5] It should actually have two people for the Isle of Wight, and one more for Norfolk, VA, but I did not tabulate those before creating the chart using the online program.

Of these slaveowners, it is clear that the Wilkinson family was Methodist, as was the Jordan family, but the Wilkinsons were "originally Quakers" but likely not by the time of the Revolutionary War. The Wilkinson family was suspected as being Loyalist "during the Revolution" with “Mary and Martha Wilkinsons (Wilkinson)... looked on as enemies to America” by the pro-revolutionary "Patriot" forces. However, none of the "Wilkinsons became active Loyalists." Furthermore, the Willoughby family may have had some "loyalist" leanings, with other families were merchant-based and had different leanings. At least ten of the children of the 26 families were born as "free" behind British lines while at least 16 children were born enslaved and became free after running away for their freedom. [6]

Beyond this, it is worth looking at how the British classified the 31 women listed in the "Book of Negroes" compiled in 1783, of which Annapolis was one of the stops on their way to Canada. Four were listed as "likely wench[s]" , four as "ordinary wench[s]", 18 as "stout wench[s]", and five as other. Those who were "likely wench[s]" were likely categorized as "common women" (the definition of wench) rather than "girl, young woman" since all adult women were called "wench" without much exception. [7] As for those called "ordinary" they would belong to the "to the usual order or course" or were "orderly." The majority were "stout" likely meaning that they were proud, valiant, strong in body, powerfully built, brave, fierce, strong in body, powerfully built rather than the "thick-bodied, fat and large, bulky in figure," a definition not recorded until 1804.

Fighting for the British Crown

Tye Leading Troops as dramatized by PBS. Courtesy of Black Past.

When now-free Blacks, most of whom were formerly enslaved, were part of the evacuation of the British presence from the British colones from New York, leaving on varying ships, many of them had fought for the British Crown within the colonies. Among those who stopped by Annapolis on their way North to Canada many were part of the Black Brigade or Black Pioneers, more likely the latter than the former.

The Black Pioneers had fought as part of William Howe's army, along with "black recruits in soldiers in the Loyalist and Hessian regiments" during the British invasion of Philadelphia. This unit also provided "engineering duties in camp and in combat" including cleaning ground used for camps, "removing obstructions, digging necessaries," which was not glamorous but was one of the only roles they played since "Blacks were not permitted to serve as regular soldiers" within the British Army. While the noncommissioned officers of the unit were Black, commissioned officers were still white, with tank and file composed mainly of "runaways, from North and South Carolina, and a few from Georgia" and was allowed as part of Sir Henry Clinton's British military force, as he promised them emancipation when the war ended. The unit itself never grew beyond 50 or go men, with new recruits not keeping up from those who "died from disease and fatigue" and none from fighting in battle since they just were used as support, sort of " garbage men" in places like Philadelphia. The unit, which never expanded beyond one company, was boosted when Clinton issued the "Phillipsburgh Proclamation," decreeing that Blacks who ran away from "Patriot" slavemasters and reached British lines were free, but this didn't apply to Blacks owned by "Loyalist" slavemasters or those in the Continental army who were "liable to be sold by the British." In December 1779, the Black Pioneers met another unit of the same type, was later merged with the Royal North Carolina Regiment, and was disbanded in Nova Scotia, ending their military service, many settling in Birchtown, named in honor of Samuel Birch, a Brigadier General who provides the "passes that got them out of America and the danger of being returned to slavery." Thomas Peters, Stephen Bluke, and Henry Washington are the best known members of the Black Pioneers.

The Black Brigade was more "daring in action" than the Black Pioneers or Guides. Unlike the 300-person Ethiopian Regiment (led by Lord Dunmore), this unit was a "small band of elite guerillas who raided and conducted assassinations all across New Jersey" and was led by Colonel Tye who worked to exact "revenge against his old master and his friends" with the title of Colonel a honorific title at best. Still, he was feared as he raided "fearlessly through New Jersey," and after Tye took a "musket ball through his wrist" he died from gangrene in late 1780, at age 27. Before that happened, Tye, born in 1753, would be, "one of the most feared and respected military leaders of the American Revolution" and had escaped to "New Jersey and headed to coastal Virginia, changing his name to Tye" in November 1775 and later joined Lord Dunmore, The fighting force specialized in "guerilla tactics and didn’t adhere to the rules of war at the time" striking at night, targeting slaveowners, taking supplies, and teaming up with other British forces. After Tye's death, Colonel Stephen Blucke of the Black Pioneers replaced him, continuing the attacks long after the British were defeated at Yorktown.

After the war

Many of the stories of those who ended up in Canada and stopped in Annapolis are not known. What is clear however is that "an estimated 75,000 to 100,000 black Americans left the 13 states as a result of the American Revolution" with these refugees scattering "across the Atlantic world, profoundly affecting the development of Nova Scotia, the Bahamas, and the African nation of Sierra Leone" with some supporting the British and others seized by the British from "Patriot" slaveowners, then resold into slavery within the Caribbean sea region. Hence, the British were not the liberators many Blacks thought them to be.Still, after the war, 400-1000 free Blacks went to London, 3,500 Blacks and 14,000 Whites left for Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, where Whites got more land than Blacks, some of whom received no land at all. Even so, "more than 1,500 of the black immigrants settled in Birchtown, Nova Scotia," making it the largest free Black community in North America, which is why the "Birchtown Muster of Free Blacks" exists. Adding to this, these new Black refugees in London and Canada had a hard time, with some of those in London resettled in Sierra Leone in a community which survived, and later those from Canada, with church congregations emigrating, "providing a strong institutional basis for the struggling African settlement." After the war, 2,000 white Loyalists, 5,000 enslaved Blacks, and 200 free Blacks left for Jamaica, including 28 Black Pioneers who "received half-pay pensions from the British government." As for the Bahamas, 4,200 enslaved Blacks and 1,750 Whites from southern states came into the county, leading to tightening of the Bahamian slave code.

As one historian put, "we will never have precise figures on the numbers of white and black Loyalists who left America as a result of the Revolution...[with most of their individual stories are lost to history [and] some information is available from pension applications, petitions, and other records" but one thing is clear "the modern history of Canada, the Bahamas, and Sierra Leone would be greatly different had the Loyalists not arrived in the 1780s and 1790s." This was the result of, as Gary Nash, the "greatest slave rebellion of North American slavery" and that the "high-toned rhetoric of natural rights and moral rectitude" accompanying the Revolutionary War only had a "limited power to hearten the hearts of American slave masters." [8]

While there are varied resources available on free Blacks from the narratives of enslaved people catalogued and searchable by the Library of Virginia, databases assembled by the New England Historic Genealogical Society or resources listed by the Virginia Historical Society, few pertain to the specific group this article focuses on. Perhaps the DAR's PDF on the subject, the Names in Index to Surry County Virginia Register of Free Negroes, and the United Empire Loyalists Association of Canada (UELAC) have certain resources.

While this does not tell the entire story of those Black families who had left the colonies, stopping in Annapolis on the way, in hopes of having a better life, it does provide an opening to look more into the history of Birchtown, (also see here) and other communities in Canada and elsewhere. [9]

© 2016-2023 Burkely Hermann. All rights reserved.

#british crown#british rule#british royalty#annapolis#enslaved people#enslavement#black history#nova scotia#birchtown#fisheries#slaveowners#american revolution#revolutionary war#slavery#book of negroes#1800s#1780s#colonel tye#lord dunmore#canada#loyalists

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

White Supremacy vs. Black Legacy

Drinking coffee while walking down the street. The thoughts came as I listened to the podcast Kelechi Okofor’s Say Your Mind.

I stood in the cold and wrote…

The fact that enslaved people were repositioned to work as internships apprenticeships etc after the abolishment of slavery with the slaved families getting compensation for their black bodies nullifies the act and undermines the totality…

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Theophilus D Packard: the anti-slavery crusader

Pamphlet for meeting opposing annexation of Texas in Boston.

Theophilus D Packard, as his Find A Grave entry notes (which I wrote), was born in Bridgewater, Massachusetts on March 4, 1769 to Abel Packard and Esther Porter, and had three siblings. By February 25, 1800 he would marry a woman named Mary Terrill in Abington, Massachusetts and they would have five children: Theophilus (1802), Isaac (b. 1804), Louisa (b. 1808), Laura (b. 1815), and Jane (b. 1817). He would live in Shelburne, Massachusetts until his death, serving as a Christian minister, going to Princeton, Amherst, was a member of the Franklin County Anti-Slavery Society (FCAS), formed on December 1836, and helped Mary Lyon establish the Mount Holyoke Female Seminary. Beyond that bio, and his death in September 1855 at age 86, he would be involved in four anti-slavery petitions to the US Congress.

Note: This was originally posted on Nov. 3, 2017 on the main Packed with Packards WordPress blog (it can also be found on the Wayback Machine here). My research is still ongoing, so some conclusions in this piece may change in the future.

As the nation continued to debate the topic of enslaved Blacks, Theophilus came out on the side of justice. On September 18, 1837, he joined "other congregational ministers of the Franklin Association" in Franklin County, Massachusetts, to protest against the "annexation of Texas to the Union of these States." Nine days later he (or perhaps his son of the same name who seemed to be against slavery as well) signed onto another petition. Again he petitioned on behalf of the Franklin Association of Ministers, supporting "the abolition of slavery, or of slavery and the slave trade, in the District of Columbia, or in the District of Columbia and the Territories of the United States." Two days later, John Quincy Adams, then a representative of Massachusetts who strongly disapproved of "the expansion of slavery..[and] the annexation of Texas and the war with Mexico," specifically

presented sundry petitions and memorials of inhabitants of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, praying that the resolution of the House of Representatives of the 18th of January last, requiring all petitions, memorials, and papers, relating in any way to slavery, to be laid upon the table, may be rescinded

One of those petitions was from "...Theophilus Packard and 13 other citizens."

Theophilus wasn't done. With fifty other citizens of MA, on January 12, 1846, he petitioned "against the admission of Texas as a slave State into the Union."

In order to understand Theophilus's stand, lets give some historical background.

In 1836, Texas had declared independence from Mexico because they felt the Mexican government had "ceased to protect the lives, liberty and property of the people" of their region, cited "atrocities" by the Mexican state on those in the region including siding with indigenous peoples, declaring that "the necessity of self-preservation, therefore, now decrees our eternal political separation." But there was more than this. When they talked about "property," they meant enslaved Blacks. Article 5 of the 1836 Treaty of Velasco between Mexico and Texas made this clear:

That all private property including cattle, horses, negro slaves or indentured persons of whatever denomination, that may have been captured by any portion of the mexican army or may have taken refuge in the said army since the commencement of the late invasion, shall be restored to the Commander of the Texian army, or to such other persons as may be appointed by the Government of Texas to receive them.

From 1836 until 1845, Texas continued as an independent slaveholding republic. By 1845, as the Texas State Library and Archives Commission argued, the joint resolution passed by Congress, "that admitted Texas to the Union provided that Texas could be divided into as many as five states." [1] James Polk, then the President, supported the measure, saying it was "the peaceful acquisition of a territory once her own." Furthermore, as the US State Department, all of all places, says in their write-up on the topic, there were economic motives at play:

...Texas was a producer of cotton. It was also dependent upon slave labor to produce its cotton. The question of whether or not the United States should annex Texas came at a time of increased tensions between the Northern and Southern states...over the legality and morality of slavery... there was another issue raised by the Texas-cotton nexus: that of the market for raw cotton. One of the largest export markets for North American raw cotton...was to Great Britain. As long as Texas remained an independent state, it could give Southern U.S. cotton plantation owners competition in terms of setting prices

The Texas government accepted the terms proposed by the US Congress, the latter which allowed Texas to be a "slave state," giving it two representatives in the US House of Representatives. In later years, Southerners wanted to "exercise the provision to create another slave state from Texas to balance the admission of California as a free state" but this was rendered moot with the end of the Civil War. Beyond that, Texas would later be given $10 million to pay off its debt to Mexico, along with the passing of the Fugitive Slave Act, all as part of the Compromise of 1850. While the nation stayed united, it didn't stay that way for long, as the Civil War from 1861 to 1865 tore the nation apart, with over 600,000 people dying overall in one of the most bloody conflicts in US history. Texas, in its declaration of succession defended its slaveholding, declaring that abolitionism was one of the causes for joining the Confederacy, which fundamentally was (and should always be seen as) a pro-slavery racist force:

...the non-slave-holding States...demand the abolition of negro slavery throughout the confederacy, the recognition of political equality between the white and negro races...For years past this abolition organization has been actively sowing the seeds of discord through the Union, and has rendered the federal congress the arena for spreading firebrands and hatred between the slave-holding and non-slave-holding States...We hold as undeniable truths that the governments of the various States, and of the confederacy itself, were established exclusively by the white race, for themselves and their posterity; that the African race had no agency in their establishment; that they were rightfully held and regarded as an inferior...the servitude of the African race...is mutually beneficial to both bond and free.

Theophilus, although there is no record he went to the southern part of the US, was among the "firebrands" that Texas detested for reasons as mentioned above. For this, he should be celebrated by any rational individual. He was, by any definition, an anti-slavery crusader, a fighter for justice, to say the least. It is hard to say what political party he was sympathetic toward, but undoubtedly sided with those at the time who opposed slavery.

Courtesy of Find A Grave. While something seems to make me think this is a new stone, the lichen on the stone makes me think it was actually created in 1855.

© 2017-2022 Burkely Hermann. All rights reserved.

#packards#slavery#enslaved people#black people#black history#find a grave#massachusetts#texas#us history#california#mexico#mexican-american war#james polk#petitions#cotton#ministers#john quincy adams

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

American President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. January 1, 1863.

Image: First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation of President Lincoln by Francis Bicknell Carpenter (1864) (Public Domain)

On this day in history, January 1, 1863, as the third year of the Civil War approached and the carnage on the battlefield continued, American President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. The Proclamation pronounced “that all persons held as slaves”…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

John Edmonstone, the formerly enslaved person who became a master taxidermist and taught Charles Darwin at university in Scotland

This piece also gives a good description of the incredibly complicated relationships that developed between enslaved people and the people who enslaved them.

0 notes

Text

Most of the potters at this time, those who were enslaved as well as the white laborers who were not, did not inscribe or mark their work in any identifying way. Dave was different. He signed his name on the walls of his pots. He engraved markings, for example, such as forward slashes and circled X’s that may have been a way to keep inventory, or that hearkened to ancestral roots. Dave also wrote dates, the location where he fashioned the pots, lines of poetry, and Christian proverbs. All of these practices set him apart."

"Such men were true artists in a world that did not recognize their work, yet they persisted in moving beyond necessity to create works of enduring beauty.”

Full Article On JStor.org

#art history#pottery#ceramics#dave the potter#enslaved people#Southeast US#the South#South Carolina#handmade#art#sculpture

0 notes

Photo

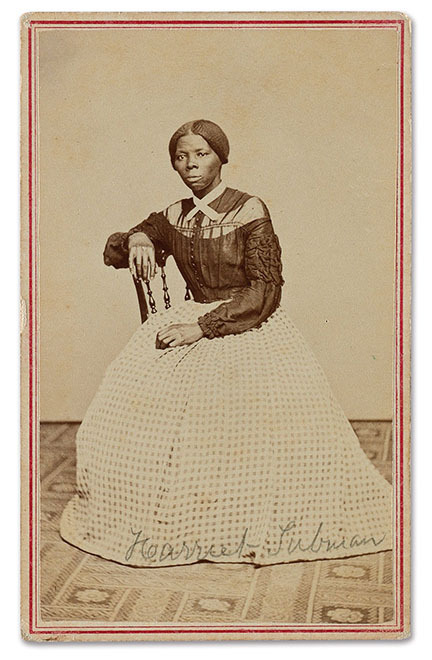

The governor’s office said the home is believed to be that of an enslaved overseer, possibly Jerry Manokey. It follows the April 2021 announcement of the discovery of the home of Ben Ross, Tubman’s father.

“Harriet Tubman’s birthplace is sacred ground, and this discovery is part of our ongoing commitment to preserve the legacy of those who lived here,” Moore said in a news release.

Maryland Department of Transportation Chief Archaeologist Dr. Julie Schablitsky and her team have been searching for the homes of those enslaved on the Thompson Farm for more than two years. At one time, more than 40 enslaved people lived there. The recent home discovery is on private property, while the archaeological remains of Ross’s home are located on the Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge.

Beneath layers of soil, archaeologists uncovered a substantial brick building foundation of the home. The excavation also revealed hundreds of artifacts.

Watch interview with archaeologist Dr. Julie Schablitsky here.

Source: AP News, WBALTV, Town & Country Magazine. Learn more about the rare Harriet Tubman photo used above here.

Visit www.attawellsummer.com/forthosebefore to learn more about Black history and read new blog posts first.

Need a freelance graphic designer or illustrator? Send me an email.

#Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge#Ben Ross#Thompson Farm#Harriet Tubman#archaeology#enslaved people#slaves#slavery#New England#Maryland#Baltimore Maryland#Baltimore history#Black history#American history#Dorchester County

10 notes

·

View notes