#sir Douglas Haig

Text

Character ask response!

This is from @histoireettralala who found the ask post

I have made some modifications given that this is a “history fandom-only” blog and I’ve ask everyone here to send me random historical people instead of what the original ask post has suggested.

So, you asked for Sir Douglas Haig

This biatch.

Hmmmmmmm

Horse plinko and blorbo at the same time because I just love calling him dumb blondie all the time and he’s one of my favourite WWI bois to read about OwO

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

EL LLEGAR TARDE A SU OBLIGACIÓN, AUNQUE SEA DE MINUTOS... Rafael Dávila Álvarez. General de División (R.)

EL LLEGAR TARDE A SU OBLIGACIÓN, AUNQUE SEA DE MINUTOS… Rafael Dávila Álvarez. General de División (R.)

Dicen las Reales Ordenanzas para las Fuerzas Armadas, Capítulo I dedicado a los principios básicos del militar, en concreto al Espíritu militar, en su artículo 14:

«El militar cuyo propio honor y espíritu no le estimulen a obrar siempre bien, vale muy poco para el servicio; el llegar tarde a su obligación, aunque sea de minutos; el excusarse con males imaginarios o supuestos de las fatigas que le…

View On WordPress

#batalla de somme#blog generaldavila.com#Ciropedia de Jenofonte#Dia de la Fiesta Nacional#El protocolo#glosas a heraclito#julian marias#rafael davila alvarez#reales ordenanzas para las fuerzas armadas#sir douglas haig

0 notes

Photo

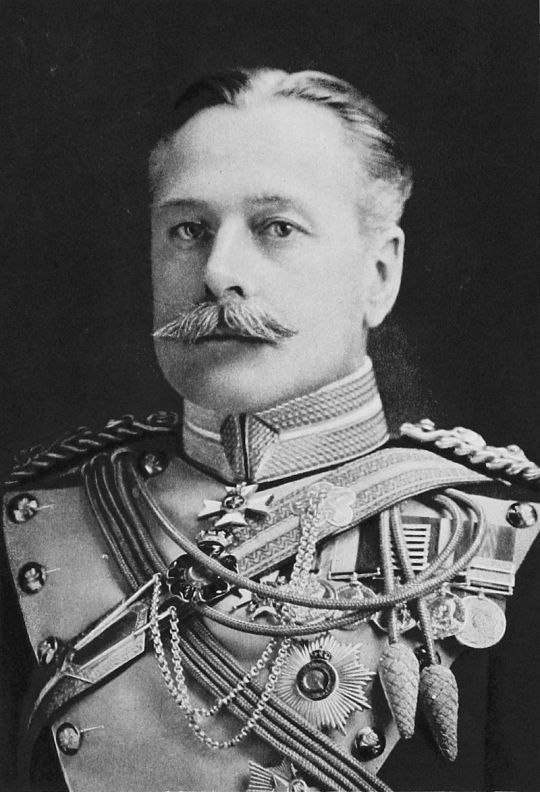

Field-Marshal Sir Douglas Haig at General Headquarters, France: Sir William Orpen, May 1917.

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

History

November 20, 1789 - New Jersey became the first state to ratify the Bill of Rights.

November 20, 1910 - Francisco Madero launched the social revolution in Mexico, exposing Mexico's political dictatorship and called for honest elections. Dubbed the "Apostle of Democracy," he was elected president in 1911, but was hampered by a lack of practical political experience. He was ousted by a military revolt in 1913, and was then assassinated while in police custody.

November 20, 1917 - The first use of tanks in battle occurred at Cambrai, France, during World War I. Over 300 tanks commanded by British General Sir Douglas Haig went into battle against the Germans.

November 20, 1943 - The Battle of Tarawa began in the Pacific War as American troops attacked the Japanese on the heavily fortified Gilbert Islands. It took eight days for the 5th Amphibious Corps, 2nd Marine Division and the 27th Infantry Division to take Tarawa and the Makin Islands. Over 1,000 Americans were killed with 2,311 wounded. The Japanese lost 4,700 men.

November 20, 1945 - The Nuremberg War Crime Trials began in which 24 former leaders of Nazi Germany were charged with conspiracy to wage wars of aggression, crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity.

November 20, 1947 - England's Princess Elizabeth married Philip Mountbatten. Elizabeth was the first child of King George VI and became Queen Elizabeth II upon the death of her father in 1952.

November 20, 1962 - The Cuban Missile Crisis concluded as President John F. Kennedy announced he had lifted the U.S. Naval blockade of Cuba stating, "the evidence to date indicates that all known offensive missile sites in Cuba have been dismantled."

November 20, 1980 - In China, Jiang Qing, the widow of Mao Zedong, went on trial with nine others on charges of treason.

November 20, 1992 - Fire erupted inside Queen Elizabeth's residence at Windsor Castle causing extensive damage.

Birthday - Swedish author Selma Lagerlof (1858-1940) was born in Varmland Province. She was a member of the Swedish Academy and in 1909 became the first woman to receive the Nobel Prize for literature.

Birthday - American astronomer Edwin Hubble (1889-1953) was born in Marshfield, Missouri. He pioneered the concept of an expanding universe. The Hubble Space Telescope was named in his honor. It was deployed from the Space Shuttle Discovery in 1990, allowing astronomers to see farther into space than they had ever seen from telescopes on Earth.

Birthday - Robert F. Kennedy (1925-1968) was born in Brookline, Massachusetts. He was the younger brother of President John F. Kennedy and served as his attorney general. Following the assassination of President Kennedy, Robert Kennedy became a U.S. Senator from New York. In 1968, he sought the Democratic nomination for president and appeared headed for victory, but was shot and killed by an assassin in Los Angeles, just after winning the California primary.

0 notes

Text

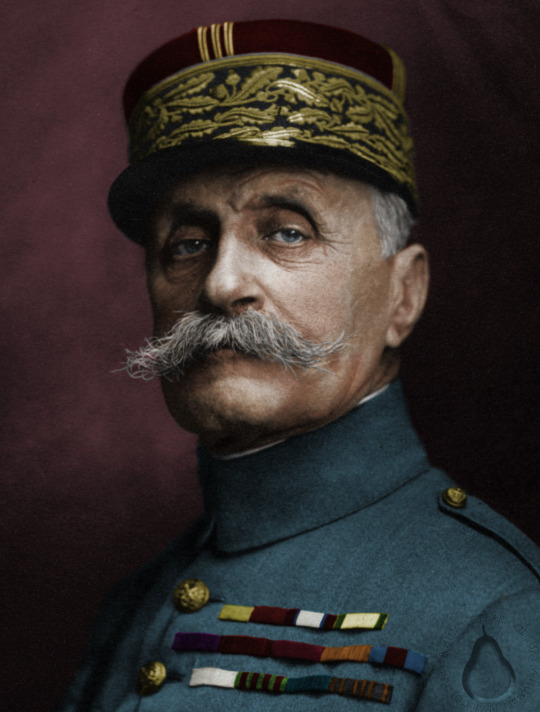

British Commander in Chief Sir Douglas Haig Ended His Army’s Offensive Near the Somme River in Northwest France, Ending the Larger-Than-Life Battle of the Somme After More Than Four Months of Blood-Stained Battle. November 18, 1916.

Image: Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, 1917. (Public Domain)

On this day in history, November 18, 1916, British Commander in Chief Sir Douglas Haig ended his army’s offensive near the Somme River in northwest France, ending the larger-than-life Battle of the Somme after more than four months of blood-stained battle.

The Battle of the Somme, which occurred from July to November 1916, started as…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

The First Battle of Somme

The First Battle of Somme began on July 1st, 1916, and was a largely unsuccessful allied offensive on the western front. The Terrible loss of life on the very first day of this battle is historically regarded as a metaphor for Futile and Indiscriminate Slaughter. On the opening day of the battle, eleven divisions of the British Fourth Army under Sir Henry Rawlinson joined five divisions of the French army maneuvering to attack a less developed area of the German army’s defense grid on an eight-mile front from Curlu to Perone. For this eight-mile stretch, the french were well equipped with over nine hundred heavy gunners. Unfortunately, the British were less than half as well equipped and tasked with the maneuver to the north over a 12-mile range. British Commander-in-Chief Douglas Haig gambled on a breakthrough despite warnings from headquarters. Even up until the battle, Haig was optimistic of the outcome but was losing compensation from France was stretched elsewhere, and couldn’t spare the agreed number of troops for the offensive. Rawlinson even reassured Haig and was quoted saying that following the bombardment “the infantry would only have to walk over and take possession.” Despite this optimism, sixty thousand troops were about to be faced with crossing a German defensive “no-mans land” carrying 66 pounds of gear and aligned like “Like Nine-pins”. The battle was an absolute disaster with almost all British troops marked as casualties. Over twenty thousand British soldiers lay on the battlefield, lifeless, having been struck down during the bombardment. This battle also marked the single worst loss the British army had ever suffered. The French and east wing of the British front did see some success during this battle but the gains were lost due to a breakdown in leadership. This battle greatly changed Commander Haigs' approach moving forward saying “I feel that every step in my plan has been taken with the Divine help.”

“Battle of the Somme.” National Army Museum, https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/battlesomme.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "First Battle of the Somme". Encyclopedia Britannica, 6 Sep. 2022, https://www.britannica.com/event/First-Battle-of-the-Somme. Accessed 13 November 2022.

0 notes

Photo

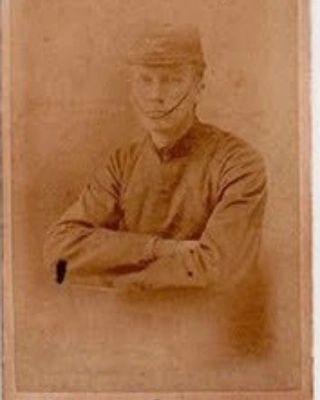

FitzRoy Curzon at the age of 19 Dated 20 September 1878 FitzRoy Curzon was born on 23 March 1859, and died, killed in action in WWI on 9 September 1916 at the Somme aged 57 having attained the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel. He fought in the Egyptian Campaign in 1898; the Battle of Khartoum, where he was mentioned in despatches; the Sierra Leone Expedition between 1898 and 1899; the Boer War between 1900 and 1902. He gained the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel in the service of the 6th Service Battalion, Royal Irish Regiment, the rank he held in the First World War. He was m entioned for the DSO in Sir Douglas Haig's Despatch of 13th November 1916. https://www.instagram.com/p/CiS3W0RD-HA/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

1 note

·

View note

Text

“In 1915 and early 1916, Canadian shell-shocked soldiers were quickly evacuated from the front and sent to special hospitals that the Canadian army established at Granville and Buxton, England. These hospitals were especially set up to treat soldiers’ symptoms as neurasthenia – as if they were physical ailments rather than emotional or mental illnesses. The established prewar regimen for neurasthenia was the rest cure, which combined sleep, light activity, diet, electrotherapy, massage, and a relaxing environment. Thus both Buxton and Granville took over former British seaside resorts that had offered the rest cure to an exclusive civilian clientele before the war and already had the necessary treatment apparatus installed. The rationale was that these pre-existing facilities and a naturally relaxing, therapeutic environment would do the most good for wartime nerve cases – especially those with shell shock.

But the special hospitals did little to encourage soldiers to remain at the front, and shell shock soon became a pressing military as well as a medical problem. In a war of attrition, soldiers who seemed to be physically healthy could not be allowed to escape their duty to King and country. The problem became acute in the Canadian army in the spring and summer of 1916 when shell-shock cases accounted for an average of 21 per cent of all non-fatal casualties in the Canadian army. The crisis came at the Battle of Mount Sorrel when between 24 May and 13 June alone, the 1st Canadian Division reported 532 cases of shell shock – 44.6 per cent of total casualties. How could so many men – but not every man – break down simultaneously?

Some medical officers began to doubt that every case was legitimate. ‘A number of men [were] buried by shell explosions or otherwise put out of action without having sustained an open wound,’ wrote Captain Harold W. McGill, 31st Canadian Infantry Battalion’s medical officer. ‘Of these there was [only] one to whom the much-abused term ‘‘shell-shock’’ could properly be applied. Often the term was used to describe a condition that was nothing but terror.’ But this implied that many soldiers were willing to intentionally feign illness or were becoming hysterical in combat; either way they were avoiding their duty as men.

At a pragmatic level, shell shock helped ensure survival – psychologically and physically. The symptoms not only relieved anxiety, but also helped the soldier to escape from the dangers of the front. It was thus a rational response to the physical threat posed by trench warfare, and many soldiers understood it to be such. ‘I am going up before the captain tomorrow to see if I cannot get leave to come home,’ wrote Private John E. to his wife Kitty. ‘My nerves are in an awful condition and my heart pumps like a thrashing machine. If I went before a medical board they’d kick me out in five minutes. I think I’ll go over to Weston [the Regimental Medical Officer] and make him take me up. I get so shakey at times I can’t control myself. I’d never be able to shoot a rifle.’

As E.’s letter shows, soldiers consciously used shell shock to negotiate with their superiors to escape from the trenches. It also provides evidence of what psychologists would later call ‘secondary gain’ in which neurological symptoms are perpetuated and encouraged because they can help fulfil psychological needs that are otherwise unobtainable. They were willing to ignore constructed masculine expectations of patriotism, self-sacrifice, and devotion to duty in order to secure psychological and physical safety. They were also willing to do so publicly by declaring themselves ‘shell shocked’ – an inherently introspective and unmasculine act. Increasingly doctors at the front began to suspect that as soldiers recognized the benefits of a shell shock diagnosis, they were subconsciously being encouraged to develop the disorder’s symptoms.

In June 1917, the commander of the British Expeditionary Force, Sir Douglas Haig, decided to block this escape route from the trenches by restricting use of the term shell shock to trained medical experts working at special shell-shock centres close behind the front. Doctors henceforth became the sole arbiters of what constituted ‘legitimate’ trauma. After Haig’s order, Canadian soldiers who seemed to be suffering from shell shock would be sent back to a dressing station or field ambulance where they were labelled with the term ‘nydn’: not yet diagnosed – nervous. From there the soldier would continue on to a special shell-shock centre such as Number 3 Canadian Stationary Hospital at Doullens, behind the lines but still close to the front. The first order of business at these hospitals was for a doctor to determine the validity of the soldier’s symptoms. ‘Immediately on admission [to one of these centres],’ recounted a Canadian shell-shock doctor,

a form . . . is made out that states that Private ‘so-and-so,’ number ‘so-and-so,’ was admitted to this hospital through a certain field ambulance; that his present condition is – giving a description of it; perhaps that he is shaking all over, perhaps he is paralyzed in his legs, perhaps he has lost his voice, or cannot see. He states that on ‘such-and-such’ a date, in ‘such-and-such’ a trench, he was under exceptional exposure, in that he was heavily shelled – and giving a description of his statement. That form is then immediately sent to the Officer Commanding of his battalion, who looks into the matter and either confirms or refutes his statement.

If the commanding officer confirmed that the soldier had suffered ‘exceptional exposure,’ either due to some specific close call with a shell or by too many months spent in the trenches, he was admitted to hospital. Doctors diagnosed those soldiers who ‘gave in’ after months in the trenches with neurasthenia, or nervous exhaustion – a case of physical fatigue.

The term shell shock was now reserved for soldiers who suddenly lost their nerve as the result of some identifiable stimulus, such as being buried by a shell explosion or blown into the air by the concussive force of the blast. If, on the other hand, the commanding officer rejected the man’s claims, he was given a quick rest and then sent back to the front within a matter of hours. While this triage system was effective insofar as it stemmed the exodus from the trenches, the greater effect of removing diagnostic power to a team of specialist doctors was to restrict and codify acceptable masculine responses to combat.

Even those doctors who believed that shell shock was a euphemism for cowardice conceded that some responses to the traumas of war were legitimate. ‘Any soldier going out to the front line has his instinct of self-preservation stimulated,’ Colin Russel, the Canadian army’s expert on psychiatric illness, told a special committee of the House of Commons:

He recognizes [that] it is a very unhealthy place for him to be and his instinct is to get out; it is only his discipline, his self-respect, his higher intelligence, that makes him stay where he is and do his duty; but that requires an effort of self-control, and that effort really amounts to a physical effort . . . We all have our physical limitations; and after a man has been at the front undergoing that strain for a certain length of time, he may become exhausted, his physical limitation is reached, and he can no longer make that intellectual effort at self-control, and gives in.

This manly, brave, physical struggle with fear was a medical sign to Russel that the case was in fact due to ‘exceptional exposure’ or nervous exhaustion. Such soldiers were developed, modern men who had proven themselves capable of resisting the emotional, base, and ‘feminine’ instinct to flee. Like prewar neurasthenics, it was their very engagement with the horrors of modern combat that caused them to acquire a condition of nervous exhaustion. To doctors it was these soldiers’ weak and inferior bodies – and specifically their nervous systems – that eventually failed them, not their minds or emotions.

Medical officers at the front agreed with Russel’s explanation. ‘There was a true condition of shell shock,’ wrote Captain McGill.

The victims were men of the finest moral courage [which in fact] set the stage for the development of shell-shock. The man’s whole physical nature revolted from the sights and sounds of a bombardment. This was much intensified if he was with troops holding a static position and obliged to sit still and take punishment without the opportunity of striking back. The thoughts and the sights of jagged pieces of steel tearing through living human flesh were appalling. All the man’s natural physical impulses prompted him to take shelter, and to run away if necessary. On the other hand his spiritual courage, his faith to his duty and his discipline forced him to remain. The result was a conflict under which the nervous system collapsed and the soldier became a gibbering maniac.

Doctors wanted to identify traditionally masculine traits in those soldiers who had proven themselves to be honourable soldiers so that they could be classified among the legitimately wounded. As Joanna Bourke argues, some doctors went so far as to theorize that ‘real men’ broke down in battle because they were unable to find an effective outlet for their masculine, aggressive instincts; modern combat was simply too impersonal to allow them to properly channel their desire to strike back at the enemy. In truth these were rationalizations that allowed doctors to explain how apparently manly men could break down with the symptoms of hysteria without challenging idealized conceptions of masculinity.

If ‘real men’ broke down only after a sustained or significant period of physical stress and unnatural restraint of their instinct to kill, then those who exhibited the symptoms of trauma without enduring ‘exceptional exposure’ must have been, by definition, less than real men, either defective in some way or feminized. Continued Russel in his testimony before the special committee:

The great majority of shell-shock cases are men who have only been over there under a month and a half or two months. They have made insufficient effort. If you see a man in the trenches trying to cover himself with his rubber sheet, to hide himself from the shells, you realize that his thinking apparatus is not working very much . . . If he thought about it he would know the rubber sheet could not protect him from the shells. In other words, his intellect is not working. His primitive instincts have control over him.

Such soldiers were not suffering from physical exhaustion but some underlying defect of personality that prevented them from controlling their baser emotion to flee. Such soldiers were considered to be cases of emotional breakdown, not physical exhaustion – akin to the prewar hysteric who lost control of her body and emotions. It was these cases that Sir Andrew Macphail, the war’s official Canadian medical historian, labelled ‘childish’ and ‘feminine.’ The 1922 British War Office Committee of Inquiry into Shell Shock reported that these ‘emotional’ cases represented 80 to 90 per cent of total breakdowns in the British Expeditionary Force, of which the Canadians were a part.

In the view of military doctors, these soldiers deserved neither recognition nor treatment because the normal trauma of war had only awakened some internal and pre-existing defect; it had not actually done damage to the body that they had placed in a uniform. When Colin Russel later boasted that his doctors had cured 80 per cent of the soldiers who arrived at the Canadian special shell shock centres, what he meant was that eight in ten of them had been returned to duty, having failed to live up to dominant masculine norms. Yet in this analysis, these soldiers did not challenge dominant masculinities because they had almost immediately failed war’s test of manhood. They were cowards and defectives who could only have been expected to fail and were thus sent back to the front where war would hopefully make men of them yet. This was doctors’ solution to the first shell-shock crisis.

The other 10 to 20 per cent of shell-shocked soldiers were those who had passed the test of war but were now suffering the effects of nervous exhaustion. These ‘legitimate’ cases continued to be sent to the two special hospitals at Buxton and Granville for the duration of the war. The maintenance and care of these ‘legitimately’ shell-shocked soldiers in former resort hotels may have been an expensive undertaking, but it was designed to limit long-term expenditures.

Ottawa politicians were well aware that disabled soldiers would require government financial assistance after the war ended – and they wanted to keep costs down. As pensions would be awarded to compensate for a specific loss to a veteran’s earning potential, alleviating the symptoms of disability before discharge would save the government money over time.

‘A man is not pensioned because he has lost his eyes, but because, having lost his eyes, he cannot see,’ wrote Lt Colonel J.L. Biggar of Canada’s Board of Pension Commissioners. ‘He is not pensioned for a wounded shoulder, but because he had lost his full ability to use his arm. In other words he is pensioned for the loss, partial or complete, of a normal ability; which, in fine, is the exact meaning of the word disability.’ Although Biggar was speaking about physical disabilities, the same underlying principle applied to shell-shock casualties where the goal of treatment was the removal of neurological symptoms before discharge to civilian life.”

- Mark Humphries, “War’s Long Shadow: Masculinity, Medicine, and the Gendered Politics of Trauma, 1914–1939,” The Canadian Historical Review 91, 3, September 2010: p. 512-519.

#world war 1#world war 1 canada#war trauma#trauma#disability in history#canadian veterans#masculinity#masculinities#crisis of masculinity#gender deviance#military pension#war wounded#war invalids#shell shock#trench warfare#history of mental health in canada#academic research#academic quote#british expeditionary force#canadian expeditionary force

0 notes

Photo

Con le spalle al muro: la resistenza britannica sul fronte occidentale

L'Ordine del Giorno dell'esercito britannico datato 11 Aprile 1918 è tra i documenti che hanno segnato la storia e la storiografia della Grande Guerra, e fotografa, forse in parte ingigantendola, la critica situazione di quei giorni di Aprile di cento anni fa.

Questo il testo completo: (traduzione mia, per la versione originale consultare il testo in inglese più avanti):

“A tutti i ranghi dell'esercito britannico in Francia e nelle Fiandre,

Tre settimane fa da oggi, il nemico ha iniziato un terrificante assalto contro le nostre posizioni su un fronte di 50 miglia (80 km, ndt). Il suo obiettivo è quello di separarci dai Francesi, conquistare i porti sul Canale e distruggere l'esercito britannico.

Nonostante abbia già gettato 106 divisioni nella battaglia, subendo un incosciente sacrificio di vite umane, allo stato attuale ha fatto pochi progressi verso i suoi traguardi. E questo lo dobbiamo alla lotta determinata e al sacrificio delle nostre truppe.

Non ho parole per esprimere l'ammirazione che provo per la splendida prova di resistenza offerta da tutti i ranghi del nostro esercito nelle più difficili circostanze.

Molti fra noi ora sono stanchi. A costoro vorrei dire che la vittoria sarà di quella fazione che resisterà più a lungo. L'esercito francese si sta muovendo rapidamente e in grandi forze per darci supporto.

Non ci rimane alcuna alternativa se non combattere. Ogni posizione deve essere tenuta fino all'ultimo uomo, non deve esserci nessuna ritirata. Con le spalle al muro e fermamente convinti nella giustizia della nostra causa, ognuno di noi deve combattere fino alla fine. La sicurezza delle nostre case e la libertà dell'umanità dipendono dal comportamento di ciascuno di noi in questo momento critico”.

Non tutti reagiscono bene a queste parole, alcuni si domandano ironicamente quale sia il muro a cui Haig fa riferimento e a cui poter appoggiare le spalle.

Lo stesso giorno, Armentières, evacuata dagli alleati il giorno prima, è occupata dai tedeschi.

Nelle foto: 1. Soldati tedeschi corrono tra le strade di Armentières durante un bombardamento inglese. 2. Copia dell'Ordine del Giorno.

With our backs to the wall: British resistance on the western front On 11 April 1918.

Sir Douglas Haig issues a remarkable "Special Order of the Day" to the British Army. The document, one of the most iconic and known documents of the Great War, marks how critical was the situation in those April days, one hundred years ago. Here's the full text:

"To all ranks of the British Army in France and Flanders

Three weeks ago to-day the enemy began his terrific attacks against us on a fifty-mile front. His objects are to separate us from the French, to take the Channel Ports and destroy the British Army.

In spite of throwing already 106 Divisions into the battle and enduring the most reckless sacrifice of human life, he has as yet made little progress towards his goals.

We owe this to the determined fighting and self-sacrifice of our troops. Words fail me to express the admiration which I feel for the splendid resistance offered by all ranks of our Army under the most trying circumstances.

Many amongst us now are tired. To those I would say that Victory will belong to the side which holds out the longest. The French Army is moving rapidly and in great force to our support.

There is no other course open to us but to fight it out. Every position must be held to the last man: there must be no retirement. With our backs to the wall and believing in the justice of our cause each one of us must fight on to the end. The safety of our homes and the Freedom of mankind alike depend upon the conduct of each one of us at this critical moment.

Douglas Haig

Commander-in-Chief British Armies in France

General Headquarters

Tuesday, April 11th, 1918"

Not all the men enjoys these words, some of them ironically questions: "where's the fucking wall?" On the same day Haig issued the Order, Armentières evacuated the previous day is occupied by the Germans.

In the pictures: 1. German troops running through British shell fire at Armentières.2. Copy of the Special Order of the Day.

Fonte / Source: Immagine/Image 1. © IWM (Q 61032) Immagine/Image 2. Australian War Memorial website

#Imperial war museum#Australian War Memorial#WW1#Prima Guerra Mondiale#First World War#Grande Guerra#Great War#1918#Sir Douglas Haig#Western Front#fronte occidentale#esercito britannico#Armentières#France#Francia#1GM#storia#history

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unveiling of the Cenotaph

The Cenotaph, pictured between 10:30 and 11AM on November 11, 1920. The casket of the Unknown Warrior, drawn by a gun carriage, is partially obscured behind a tree.

November 11 1920, London--The official Victory Parade, celebrating the Allied victory in the war, was held in July 1919. It featured a cenotaph--an empty tomb--commemorating all the soldiers of the British Empire who had fallen overseas, their bodies buried there. The 1919 cenotaph was a temporary construction, but it was so popular (over a million people visiting the structure in the week after the parade) that there were soon calls for a permanent version.

The permanent Cenotaph, built on the same site in Whitehall as the temporary one, was built between May and November 1920, ahead of the unveiling on the second anniversary of the Armistice. As part of the ceremony, it was also decided to exhume an unidentified British soldier from France and bury him as the Unknown Warrior in Westminster Abbey (not in the Cenotaph itself, which was intentionally empty).

At 11 AM, exactly two years after the Armistice went into effect, King George V pulled a lever, revealing the Cenotaph from under the two large Union flags that had covered it. The crowd stood in silence for two minutes, the “Last Post” was sounded on bugle, and the King laid a wreath before the unveiled cenotaph before the procession continued to Westminster Abbey. There, the pallbearers, which included Marshals Haig and French and Admiral Beatty, bore the casket inside, where it was interred after a brief and solemn ceremony.

Until closed at midnight, crowds filed by both the Cenotaph and the tomb in Westminster Abbey. Within a week, well over a million had paid their respects, and the Cenotaph was partially buried in a pile of wreaths and flowers over ten feet high.

#wwi#ww1#ww1 centenary#ww1 history#world war 1#world war i#The First World War#The Great War#Armistice Day#armistice#november 1920#haig#Douglas Haig#Sir John French#london#King George V#Beatty

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

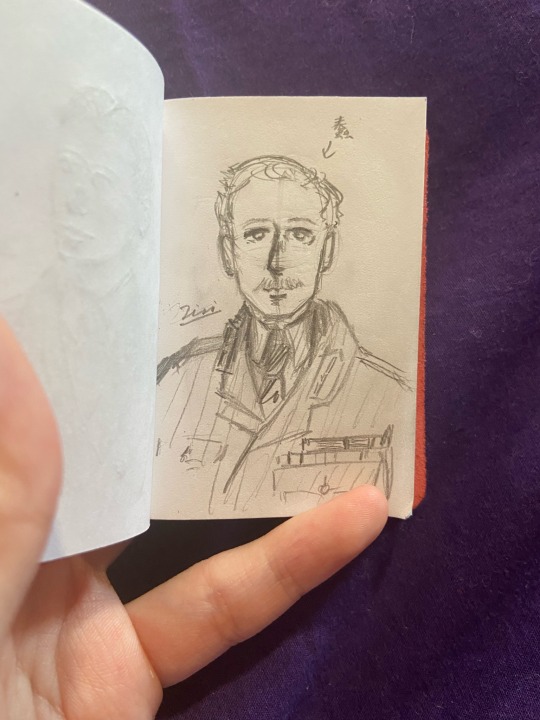

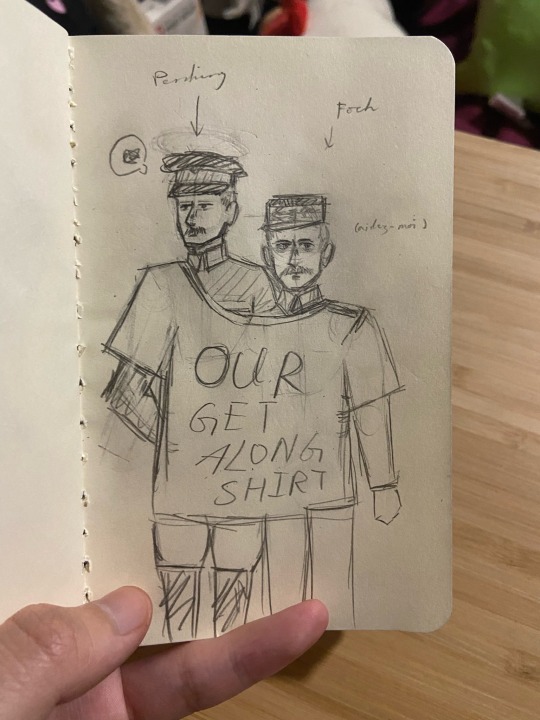

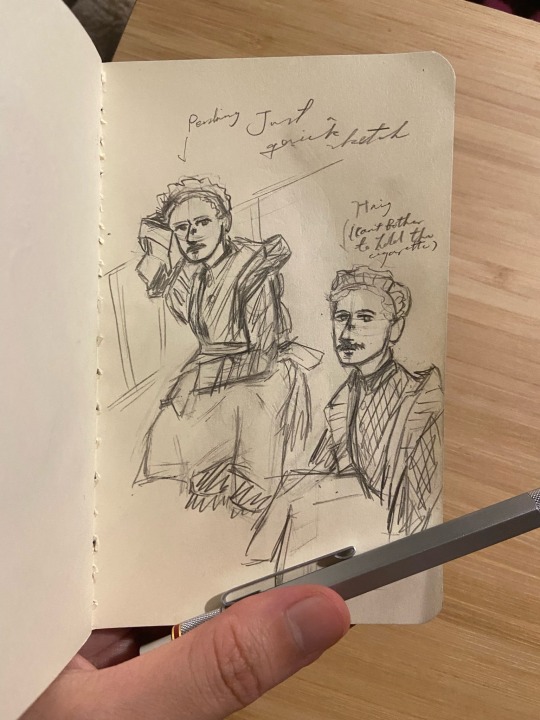

Burn book type of sketches

For some reasons, very likely because of Douglas Haig (actually found out about him when I went to Museum of Edinburgh the first time), I got into WWI so I just decided that I am drawing some dudes.

SO- May I present: Sir Douglas Haig and John J. “Black Jack” Pershing, commanders of British Expeditionary Forces and American Expeditionary Forces respectively.

They two were friends and they corresponded quite frequently after the war until Haig’s sudden death in 1928. I’ve been reading about WWI commanders lately, and there’s some stuff going on between the West Front Allied generals, so why not make it like a Burn Book?

Here is my dumb blondie Douglas 😔✨ (he’s Scottish and I luv him)

Ngl I only draw Pershing by virtue of being friends with Haig—I guess he will be the only American that I will ever draw except Hollywood stars.

Bonus: shitposting

#douglas haig#sir Douglas Haig#dumb blondie#i luv you goddamnit#John J. Pershing#black jack Pershing#someone who would have thought he had the N word pass if being in 21st century#going to draw Foch next since he needs more love#maybe I should draw Joffre or Pétain as well#Pétain was good in WWI but him in WWII was pee#history shitposting#Ferdinand Foch#ferdi foch#smol fightey babey#Foch sets my soul on fire so now I’m so motivated to get everything done#thank you Ferdi

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

ESPAÑA FEDERAL Y REPUBLICANA General de División (R.) Rafael Dávila Álvarez

ESPAÑA FEDERAL Y REPUBLICANA General de División (R.) Rafael Dávila Álvarez

Escribí este artículo hace más de un año. Un buen amigo me lo recuerda a la vez que me dice: “Muy buen oráculo hace más de un año”. Releo y caigo en la cuenta que ha sucedido antes de lo que esperaba. Nadie combate en defensa de la Patria. Eso que veis y os parece, es: nada. No hay nada ni nadie y ellos lo saben. Huir nos costará la vida. Decía: “Se aproximan tiempos que requieren dignidad, valor…

View On WordPress

#aquiles#batalla de somme#españa federal r republicana#españa federal y republicana#gabriel albiac#hector#homero#iliada#la republica federal#ortega y gasset#polidamante#sir douglas haig

0 notes

Text

History

November 18, 1477 - William Caxton printed the first book in the English language, The Dictes and Sayengis of the Phylosophers.

November 18, 1883 - A Connecticut school teacher, Charles F. Dowd, proposed a uniform time zone plan for the U.S. consisting of four zones.

November 18, 1916 - During World War I, Allied General Douglas Haig called off the First Battle of the Somme after five months. The Allies had advanced 125 square miles at a cost of 420,000 British and 195,000 French soldiers. German losses were over 650,000 men.

November 18, 1993 - South Africa adopted a new constitution after more than 300 years of white majority rule. The constitution provided basic civil rights to blacks and was approved by representatives of the ruling party, as well as members of 20 other political parties.

Birthday - German composer Carl Maria von Weber (1786-1826) was born in Eutin, Germany. He founded the German romantic style of music. Best known for his operas including Der Freischutz.

Birthday - Photography inventor Louis Daguerre (1789-1851) was born in Cormeilles, near Paris. In 1839, at a meeting of the French Academy of Sciences, he announced his daguerreotype process, the first practical photographic process that produced lasting pictures.

Birthday - British author Sir William Gilbert (1836-1911) was born in London. He wrote the verses for the famed Gilbert and Sullivan comic operas which poked fun at the British establishment. Among their operas; H.M.S. Pinafore, The Pirates of Penzance, Iolanthe, The Mikado and The Yeoman of the Guard. He died in May 1911, suffering a heart attack while attempting to save a woman from drowning.

Birthday - Polish pianist Ignacy Jan Paderewski (1860-1941) was born in Kurylowka in southwestern Russia. He achieved world fame for his interpretations of Schubert and Chopin. After World War I, he served briefly as the first premier of the Republic of Poland.

0 notes

Photo

A la guerre, c'est celui qui doute qui est perdu : on ne doit jamais douter.

- Maréchal Ferdinand Foch

Ferdinand Foch (1851-1929) was the most iconic French military commander during World War One.

He was born in 1851, the son of a civil servant. In the summer of 1870, during the Franco-Prussian War, he enlisted as a private in the French infantry but never fought. (But he did gain peacetime fame for massing 100,000 men at a review in a rectangle of 120 by 100 metres.) He rose steadily in rank and in 1885 became a professor at the Ecole Supérieure de Guerre, the command college in Paris that he would eventually head. He was now in his element, and his pronouncements would influence a generation of French officers, as well as the opening events of 1914.

Foch wrote two widely read paeans to the offensive, The Principles of War (1903) and The Conduct of War (1905). “A lost battle,” he proclaimed, “is a battle which one believes lost.” “A battle won is a battle we will not acknowledge to be lost.” “The will to conquer sweeps all before it”. “Great results in war are due to the commander.” In argument, Foch tended to win by intimidation and deliberate arrogance - irresistible, perhaps, because he never admitted to doubts.

August 1914 found him in command of a crack, two-division corps on the Lorraine border. While his disciples disastrously pressed offense, the apostle of attack soon found himself on the defensive. At Morhange on August 20, the rocklike stand of his XX Corps helped avert a French catastrophe. It may have been the only time in his life - he was just short of sixty-three - that he saw action. Put in charge of the French IX Army during the Battle of the Marne, he blocked the German advance at the marshes of St.-Gond. “My right is driven in, my center is giving way, the situation is excellent, I attack,” he is supposed to have said. He probably never uttered these legendary words, but he surely would have done so had he thought of them.

Foch next took charge of the French armies of the north; he now coordinated moves with the British and Belgian armies during the so-called “race to the sea.” If he did not succeed in going on the offensive, he did help check the German drive for the last true prizes of 1914, the Channel ports.

Several times he was forced to brace up the nervous British commander, Sir John French, with what his biographer, B. H. Liddell Hart calls “an injection of Fochian serum.” But when the Germans ruptured the line at the Second Ypres in 1915, Foch’s insistence on counterattacks produced only unnecessary Allied losses. Death on an even larger scale was the most visible result of Foch’s Artois offensives in the spring and early fall of the year; casualties approached 150,000. After the Artois the élan of the French common soldier, which he so prized, would never be the same.

In 1916, he directed the French part of the 141-day offensive at the Battle of the Somme. He gained more territory and lost fewer men than his British opposite, General Sir Douglas Haig, but the costly lack of a decision seemed to have permanently tarnished his career. Foch was relieved of command. He bided his time, a phoenix waiting to soar from the ashes, and gradually worked his way back to a position of influence. He had the good fortune not to have played a part in the Allied disasters of 1917.

On March 21, 1918, Erich Ludendorff’s German armies broke through on the Western Front and seemed ready to split the French and British armies asunder. Desperate prospects demanded desperate measures–and on March 26 the Allied leaders did what they should have done long before: they named a supreme commander. Their choice was Foch. His reaction was characteristic. “Materially, I do not see that victory is possible. Morally, I am certain that we shall gain it.”

Foch’s optimism was infectious. He unselfishly lent French troops to the beleaguered British, and the Allies weathered Ludendorff’s unremitting spring storm until American troops began to arrive in significant numbers. By midsummer the worst German threat was over. Henceforth, as hugely influential British military stratrgist Liddell Hart wrote, “Foch beat a tattoo on the German front, a series of rapid blows at different points, each broken off as soon as its initial impetus waned.”

By the late fall, the German army was on the point of disintegration. Foch felt that the war had gone on long enough. On November 8-11, 1918, in a railway carriage at a forest siding near Compi[egrave]gne, he personally dictated armistice terms to a German delegation. At last, but not too late, he had learned when to stop.

Ferdinand Foch was the most inspired of the Western Front generals in World War I, sometimes to his detriment. He could be almost mystically reckless with lives, initiating attacks when restraint would have served him better or prolonging offensives beyond all hope of success. His own pronouncements had a tendency to catch up with him. Fortunately for his permanent reputation, he is chiefly remembered more for his presiding role in the victory of 1918 than for his sanction of the futile hecatombs of 1915 and 1916.

#foch#ferdinand foch#quote#french#french army#military#militaire#first world war#world war one#leadership#strategy#history#france

38 notes

·

View notes

Photo

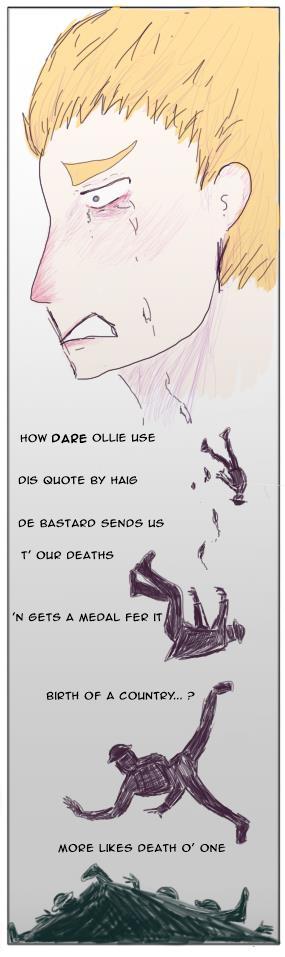

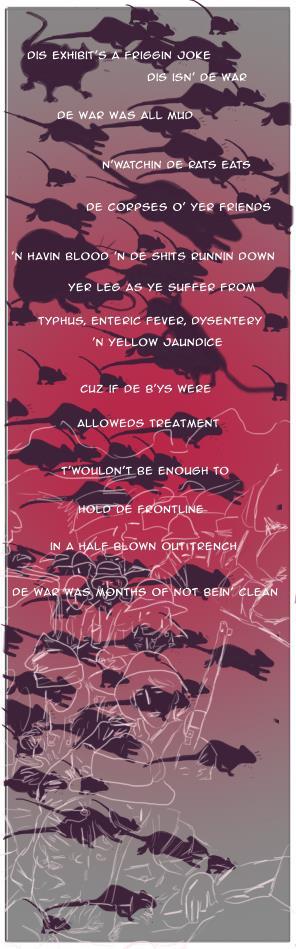

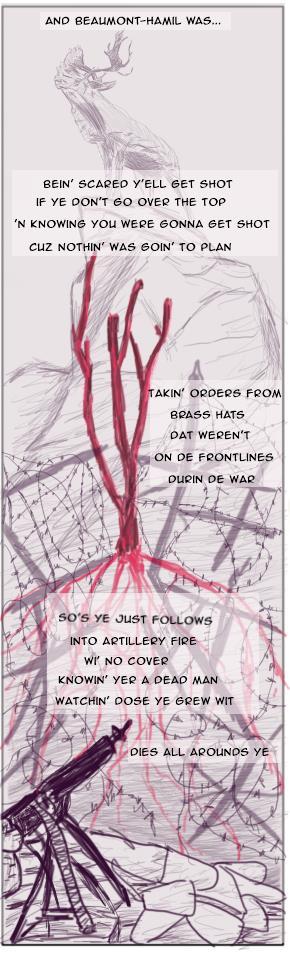

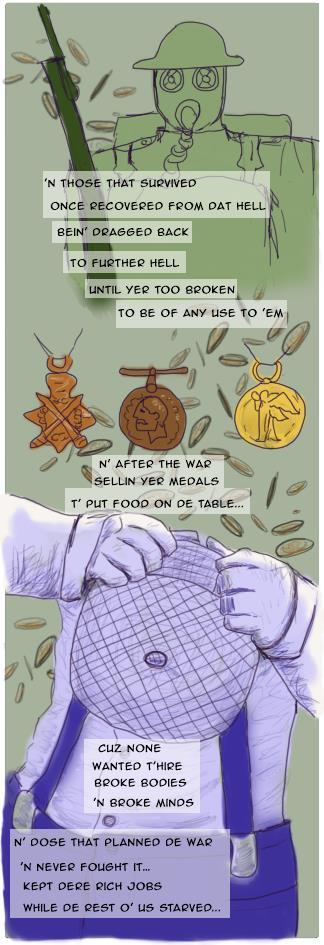

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4

Notes below

1) Oh boy that quote from Douglas Haig in theory is one he said when he visited in St Johns (this was from A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service ) but then the Fighting Newfoundlander source claims it was said by Lieutenant-General Sir Aylmer Hunter-Weston. What is the truth when the sources conflict? I don’t know. I decided to keep it as Haig because there is a lot of complicated feelings around that man and the decisions he made (especially when reading Into the Blizzard and A Boy from Botwood)

2) I was having conflicting feelings about posting this and having Ben be bitter about the war, with the intentions of memory being more from a working class perspective. I feel like a lot of war narratives glorify it as nation building and a wonderful thing to happen and when boys become men, when in reality its the poor people being sent out to die on the rich mans orders and being promised the world, when in reality all they get is shit. It was quite depressing reading post war narrative where, while some companies hired veterans, there was literally the need to hide the fact you were a war veteran because companies did not want to hire disabled men who had PTSD.

3) Bert is the type of man who typically would look away from someone expressing an emotion that is not anger. The fact he even attempted to comfort is miraculous haha. He is also secretly Very Thirsty for all the Information because he was raised on war propaganda and thinks the war is cool

4) Yes for some god foresaken reason I did read numerous books just to draw some sad war comic, please do not question how my brain works. I suppose this is more fun than a research paper.

5) Ben survived Beaumont-Hamil and went on to fight some of the other battles such as at Gueudecourt, Sailly-Saillisel and ending at the Battle of Aras, where he lost his leg (is this a spoiler??) (Maybe the question is Why did I think this Through so Much) I should probably say I’ve put him in the first 500 mythos, so he did go to Gallipoli as well and got to enjoy all the flies and trench rats. : )

6) Looking forward to wrapping this comic up.

7) Let me know if you want to know anything else

#quatschart#war comic#pc: newfoundland#pc: alberta#iamp#procan#iamp: alberta#iamp: newfoundland#wwi#quatschcomic

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On This Day In Royal History

.

12 September 1938

.

Prince Arthur of Connaught died aged 55

.

½: Prince Arthur was born on 13 January 1883 at Windsor Castle. His father was the Duke of Connaught and Strathearn, third son of Queen Victoria & Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. His mother was the former Princess Louise Margaret of Prussia.

.

◼ Arthur was the first British royal prince to be educated at Eton College. After attending finishing school, Prince Arthur was educated at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, from where he was commissioned into the 7th (Queen’s Own) Hussars in 1901. During the Second Boer War, he saw active duty with the 7th Hussars. In 1907, he was promoted to the rank of captain in the 2nd Dragoons (Royal Scots Greys). He became the honorary Colonel-in-Chief of this regiment in 1920.

.

◼ During the First World War, Prince Arthur served as aide-de-camp to British army Generals Sir John French & Sir Douglas Haig, the successive commanders of the British Expeditionary Force in France & Belgium. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel in 1919 & became a colonel in the reserves in 1922. In October 1922, Prince Arthur was promoted to the honorary rank of major general & became an aide-de-camp to his first cousin, King George V.

.

◼ Since the king’s children were too young to undertake public duties until after the First World War, Prince Arthur carried out a variety of ceremonial duties at home & overseas.

.

. (at United Kingdom)

https://www.instagram.com/p/CTu1C7gsPyb/?utm_medium=tumblr

15 notes

·

View notes