Text

"After Confederation, when the province's sources of income were reduced to licences, fees, direct taxes and the crown lands, the financial importance of the forests increased tremendously. Whenever the provincial treasurer required additional revenue to meet his obligations (this usually happened just before an election), the Commissioner of Crown Lands merely auctioned off another batch of timber limits. By this time good timber was in such demand that lumbermen were prepared to bid against one another—paying what was called a bonus—for cutting rights. Timber dues (paid on the amount cut at the time of cutting) and ground rent (paid annually on the area under licence) were, of course, in addition to the initial bonus payment. Good reasons could always be found for holding a timber limit auction. The usual one was to protect the area from fire. Encroaching settlers or railroads as a rule supplied the necessary menace. Better the timber be cut over than burnt over. But one of the most obvious and persistent pressures for such sales, succinctly stated in E. H. Bronson's (a lumberman, Minister without Portfolio in the Mowat cabinet) notes for a speech defending the 1892 auction was simply: "WE WANTED THE MONEY." To help pay for railroad subsidies, roads, public institutions, hospitals, public works and the Parliament Buildings, Sandfield Macdonald's government sold off 635 square miles of timber; Edward Blake's ministry parted with 5,031 square miles in one year, and over the next 20 years Oliver Mowat disposed of 4,234 square miles. Between 1867 and 1899 bonuses, dues and ground rent from the lumber industry produced in excess of $29 million, or approximately 28 per cent of the total provincial revenue. Only the federal subsidy brought in a larger sum. In large measure the flourishing state of Ontario's public finances after Confederation can be traced to this extraordinary income from forest regulation.

As a result, politicians were not overly eager to pass on this paternity free of charge to homestead farmers if the lumbermen would literally pay millions for it. And while the state had sold rights to the lumbermen and was to a certain extent bound to protect those rights, they were not those of exclusive possession. No politician dared to appear to exclude the pioneer, the symbolic embodiment of all civic virtue, from the northern forest. The device of crown ownership and licensed rental gave the lumbermen access to the forest, returned a welcome revenue, and under ideal circumstances generated cut-over lands that could then be recovered from the lumbermen and passed on free to the homesteaders. The visibly temporary tenure of the lumberman, expressed in his annual licence and ground rent charges, allowed the state to open up desirable lands when pressed to do so. Because it served the political and economic interests so well, crown ownership continued to serve as the basis of Ontario's forest law on into the twentieth century."

- H. V. Nelles, The Politics of Development: Forests, Mines & Hydro-Electric Power in Ontario, 1849-1941. Second Edition. McGill-Queen's University Press, 2005 (1974). p. 18-19

#ontario history#forest law#lumber barons#timber stands#resource extraction#resource capitalism#birth of natural resources#h. v. nelles#reading 2023#academic quote#settler colonialism in canada#homesteading#crown lands

1 note

·

View note

Text

"As stated previously, the system of transportation, at least as far as Australians were concerned, was a system for bringing cheap labour to the market. Australia was an open prison system that provided the colonies with workers – on infrastructure projects in government chain gangs or on assignment to local employers – who were still officially serving their sentences. The original intention of the ticket of leave system was to promote good behaviour in convicts as well as to provide labour for growing economies far quicker than would otherwise have been possible. Convicts on this ticket boosted the economy – and they could be sent places where free labour did not want to go, such as uninviting and geographically dispersed rural settlements. The system was, in essence, a grand device for sorting labour. It was also a way of ‘rewarding’ those who possessed higher levels of useful skills with a quicker release from the drudgery and pains of convict life.

This system of convict labour supply probably reached its apogee in Western Australia in the early 1850s, at which time over half the transported men were working for private employers. Approximately a quarter of the convicts who arrived in Western Australia were issued tickets of leave upon entry, so they were able to take employment assignments as soon as they started their lives in the colony. However, when the government removed the stipulation that convicts had to spend half their sentence in a British prison before being transported, new arrivals to Australia in the 1850s were forced to spend more time in the ‘probationary system’ – on road gangs and on government work – before being eligible for a ticket of leave.

For both the Australian and the British authorities, the ticket of leave system had three main benefits. First, it delivered labour to the colony as soon as was practicably possible. Second, it gave colonial authorities an unusually high level of control over the ex-convict population. Third, it considerably reduced the costs of the convict system.

However, when faced with the prospect of the end of convict transportation, the British government regarded the application of the ticket of leave system on home soil suspiciously. Employers in Britain were not crying out for labour, and the newly established police constabularies had enough on their plate without supervising more and more convicts and ex-convicts. While the opportunity to reduce the costs of imprisonment through a system of early release was appealing, and might even have been viewed as fundamental to the running of a large prison estate (which was already proving to be expensive), the public could take fright at ex-convicts being ‘at large’ in their towns and cities. This was something that would require delicate handling. There was no dominant view on how all this should be achieved.

The first question was, whose views would prevail? [Joshua] Jebb [Surveyor-General of Prisons] started with an optimistic approach. He suggested that the authorities encourage ex-convicts released in Britain to opt for assisted passage to Western Australia. He was convinced that this scheme would see many willing volunteers sign up (he even assumed that the scheme was so attractive that ex-convicts would pay their own fares); however, it is unlikely that his rosy view of the opportunities offered by voluntary transportation would have attracted many ex-convict émigrés, especially since they would still have been subject to restrictions and regulations – and they would still have to hold a ticket of leave on their person whenever they ventured outside of their homes. No, the system would have to work for those who were intent on resettling into their own British neighbourhoods following release from prison.

Knowing the anxieties around released convicts, Jebb tried to assure government that the ticket system was safe and reliable. He was careful to explain that tickets of leave were only granted to those who were ‘ready’ to be released. This explains the extensive bureaucracy in Australia related to convicts’ characters, assignments, offences committed upon sentencing, and so on: these records were needed to assess who was ready to receive their ticket. A scaling-up of prison bureaucracy can be seen in the United Kingdom from the mid-nineteenth century. Indeed, it is these sets of records that form the basis of much modern historical research on convicts. However, when the convict system was repatriated to the British mainland, Jebb turned away from an individualistic approach (the kind of labour-sorting device that had predominated in Western Australia). Instead, he favoured a form of ‘conditional release’, whereby most if not all convicts received a stipulated and prescribed period of release (subject to certain conditions, such as not committing more offences and not consorting with known offenders and/or prostitutes). The promise of release on licence under certain conditions would, Jebb hoped, produce a more orderly response to imprisonment – if you kept your nose clean while inside, you could calculate the day of your release with a fair amount of accuracy.

The Penal Servitude Act of 1853 was the government’s first attempt to repatriate the convict system. As McConville noted, ‘all the essentials of penal servitude were in full operation considerably before 1853: all that the 1853 Act added to these was the certainty of release on licence in this country for all those whose sentences would not, before the passing of the Act, have exceeded fourteen years’ transportation’. Despite the public’s general dissatisfaction with tickets of leave, the system seems to have been put into operation with few problems. However, the publication (and republication in the newspapers) of annual statistics of recorded crime in 1856 and 1857, which appeared to show unacceptably large amounts of offending, caught the public’s attention.

The annual statistics collected by the police and the courts also revealed to the public a new putative category of ‘criminal classes and habitual offenders’, who were said to inhabit the rookeries and haunts of British towns and cities. This group was thought to be comprised of habitual offenders, ex-convicts, and ticket of leave men who had not been reformed by their prison experiences. High levels of crime began to be strongly associated with men who would previously have been transported to Australia, and newspaper reports lost no time in reflecting this view:

Shockingly attacked by a Ticket-of-Leave convict. The murderer, Jenkins, was convicted and sentenced to transportation in 1853. For some time after his release as a Ticket-of-Leave man he was in employment. He had no excuse of destitution or inability to earn a maintenance honestly, therefore, for relapsing into crime.

The under secretary at the Home Office, Horatio Waddington, who disliked Jebb’s ideas about early release and the act of 1853 that made them concrete, took advantage of the public’s increasing disquiet. He held the view that a ticket or conditional release should only be granted to a prisoner who was too ill to continue serving their sentence (he did not anticipate that this would apply to many), or who had served their time with such remarkable good conduct that they deserved to be rewarded with conditional release (he did not anticipate many being released on these grounds, either). Moreover, Waddington felt that release should be curtailed on the suspicion (not the conviction) of further offences being committed, and that licences should be permitted to be revoked on a whim: a capricious act on the part of the authorities. As a result, released convicts would live in terror of being recalled to prison and therefore be cautious not to draw any adverse attention to themselves.

Although his views were at the more extreme end of the debate, Waddington’s was not the only voice that outlined concern with the system as it stood. In the House of Lords in 1857, Lord Berners stated that

there was no doubt that the public mind had been very greatly agitated in reference to the ticket-of-leave system, and that the opinion was almost universally entertained, as appeared by the remarks of learned Judges, including the noble and learned Lord the Chief Justice of England himself, the Lord Mayor and magistrates of the metropolis, the recorders of different boroughs, grand juries and courts of quarter-sessions in various counties, that the system was a complete failure.

On 17 March 1857, Viscount Dungannon voiced his opinion on the matter, stating that ‘the present system was most fearful in its operation, tending to increase crime to a terrible extent, and dangerous to the peaceable part of the community. The public, therefore, had some claim for a satisfactory explanation on the subject.’ A government spokesperson replied that it was not necessary to suspend the operation of the ticket of leave system, because it only concerned a small number of convicts. ‘What is the number?’ shouted the Viscount, to which the spokesperson replied that he did not know, but he did not think it was many – not a very convincing answer given the considerable disquiet about the system among the public. None of these views carried the day, however, and – following a meeting of the Select Committee – a regulated and clear system was put in place with the introduction of the Penal Servitude Act of 1857.

The new system gave the kind of expectation of release in a calibrated manner for which Jebb had advocated. However, some saw injustice in each convict having the same proportion of their sentence reduced on licence. Why should first-time offenders, asked the anonymous author of Penal Servitude, receive the same proportion as habitual offenders who ‘spend half their lives getting into prison and the other half getting out again’? Yet, in practice, individual convicts received different periods of conditional release, structured by their progression through the system (i.e., whether they had shortened their time to release through good behaviour and carrying out their prison labour, or lengthened their time inside by breaking prison rules). While the act of 1853 had meant the certainty of release on licence in England, the act of 1857 offered the possibility of early release. An important distinction between the two acts was that, although both allowed for release on licence, only the act of 1857 allowed for remission or ‘time off’ the sentence in a more systematic manner; this resulted in a considerable amount of variation in release practices in the early years of the system as well as a sense of injustice among prisoners, especially by those held in the same prisons."

- Helen Johnston, Barry Godfrey and David J. Cox, Penal Servitude: Convicts and Long-Term Imprisonment, 1853–1948. Kingston and Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2022. p. 36-40

#convict prison#convict transportation#penal colony#uk prisons#parole#parole system#prisoner release#convict license#penal reform#sentenced to the penitentiary#parole violator#penal servitude#academic quote#history of crime and punishment#reading 2023#prison administration#ex-convicts#moral panic#conditional release#joshua jebb

0 notes

Text

"Contractors who appealed for the protection of strikebreakers and their property had good reason to expect armed intervention by the state. In British North America the law appeared ambiguous as to the legality of combinations of workers. Intersection of common law and criminal statute in the Canadas, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia left room for conflicting judicial decisions in this area and remains the subject of debate among legal historians. However, a primary advisor on labour relations to the Board of Works for the Canadas was unequivocal in declaring the labourers' combinations illegal, and in this was representative of others involved in controlling labour on the canals.

This was also the clear message presented to the government and the labourers by the commissioners investigating disturbances on the Lachine and Beauharnois. Their 1843 report concluded that the stipendiary magistrate appointed for the Beauharnois, on learning of the plans for a general strike, had been remiss in not impressing on the labourers "the illegality of all combinations of that nature and the punishment reserved for all those, who would dare to resort to such violations of the law."

Moreover, little ambiguity surrounded the contractors' right to continue operations during a strike. Contractors enjoyed widespread support among newspaper editors and the government, courts, and state law enforcement officers, who shared a general belief that strikers who interfered with those continuing work were, at best, acting outside the law and, at worst, "evil." They invited criminal charges for a wide range of activities, not necessarily violent. Men on the ground like superintendent Power might decry the low wages which pushed families to destitution, but their overriding responsibility was to continue the work, and even he could not condone any action which disrupted operations. As one scholar has argued, lack of clarity in this area of the law may have encouraged a legal zone of toleration of trade unions and strikes, which reflected a social zone of toleration evolving prior to Confederation, though strikes by canallers did not fall within that zone. Even had they, most meaningful action towards achieving their goals left strikers liable to prosecution.

At the heart of official efforts to protect strikebreakers was the belief that most labourers would be content to accept the wages and conditions offered if they were properly instructed concerning their responsibilities to their employers, the government, and God and if the few troublemakers could be weeded out.

The board also threw the resources of the state into policing. In 1843 it took the initiative in creating a constabulary to serve along the Welland, and during 1843 and 1844 from ten to twenty constables were on duty at any one time, their numbers diminishing as the workforce decreased after 1845. The board also wasted no time in creating an armed constabulary of twenty-two officers on the Williamsburg Canals under the command of Captain Wetherall, and in the wake of the labour unrest on the Lachine and Beauharnois, it reinforced its commitment to routine policing of the canals in Lower Canada. The 1845 Act for the Preservation of the Peace near Public Works committed the state more deeply to enforcement of the law through mounted police stationed on the public works wherever the government considered them necessary, not on a piecemeal basis as had been the case to that point. At a time when even the larger communities in the Canadas, along with most communities in North America, still relied on only a few constables working under the direction of a magistrate, the size of these police forces, frequently reaching over twenty officers on any one canal, demonstrated the government's commitment to labour control. The board also set out a model for state intervention in labour unrest which would be emulated, though hard to match, in subsequent decades.

Canal police forces worked closely with existing magistrates, whose responsibility it was to ensure the police acted within the law, though official investigation into the conduct of the Welland Canal force revealed that magistrates did not always keep constables from abusing their powers, exceeding their authority, operating outside the law, and increasing sectarian tensions by expressing open hostility to Catholicism. Along the Williamsburg Canals inhabitants provided additional details of mounted police who, far from generating respect for the law, made fools of it and themselves and endangered local citizens by carrying out their responsibilities recklessly and while drunk. Inhabitants of Williamsburg Township petitioned the governor general concerning the conduct of Captain James MacDonald and his men during a circus at Mariatown, when

through the misconduct of the police on their duty two persons have been maltreated and abused cut with swords and stabbed, taken prisoners and escorted to the police office that all this abuse was committed by having the constables in a state of intoxication on their duty when the Magistrate who commanded them was so drunk that he fell out of a cart. A pretty representative is Mr. MacDonald.

Their conduct provoked the priest on the canal to warn the labourers:

They are like a parcel of wolves and roaring mad lions seeking the opportunity of shooting you like dogs and all they want is the chance in the name of God leave those public works.

While the forces fulfilled various functions, in the eyes of the Board of Works their primary purpose was to ensure completion of the works within the scheduled time. Even protection of contractors from higher wages was not in itself sufficient reason for increasing the size of one of the forces. When, in December 1845, Power asked for accommodation for a superintendent of police at the Welland Junction, the board answered that the old entrance lock was the only place where a strong force was necessary, since no combination of labourers for wages on the other works could delay the opening of the navigation, "the paramount object in view." A later communication expressed more forcefully the board's general approach to funding police forces, stating that the only circumstances under which the expense of keeping the peace could be justified were those in which the availability of the canals to trade was in jeopardy.

Despite this apparently strict criterion for funding police, the board usually intervened to protect strikebreakers, probably because any strike threatened to delay opening of the navigation in the long, if not the short, term. Indeed, in their 1843 report to the legislature, the commissioners argued that it was part of their responsibility to help contractors meet deadlines by providing adequate protection to those labourers willing to work during a strike. In meeting this responsibility the board at times hired as many as sixteen extra men on a temporary basis. When it was a question of get ting the canals open for navigation, the government appears to have been willing to go to almost any lengths to continue the work. In the winter of 1845, the governor general finally gave Power the authority to hire whatever number of constables it would take to ensure completion of construction by spring.

In the following decade, no special force was created for either the Junction or the Chats Canal; perhaps the expense did not appear warranted, given the number of labourers employed at any one time and the relatively sparsely settled area of the country in which the projects were located. That left policing to local magistrates. Magistrate Cook, responsible for the area around the Junction, complained that he could not provide the additional time and money necessary to respond to disturbances on the canal, particularly since he could not afford the help of special constables. Were the department able to help cover his expenses and the cost of a sufficient number of special constables, he would do his best to maintain the peace. Inhabitants along the canal also believed they were in need of protection from the disturbances in their immediate area and requested appointment of a stipendiary magistrate and police force. Superintendent Page advised the department that a stipendiary magistrate and what he called "a sort of reserve police," along the lines suggested by Magistrate Cook, might ultimately be required, but it does not appear to have been created."

On the European and North American Railway, the special railway police force created by the New Brunswick government included in its mandate protection of the work and those who wished to continue work during a strike. It expanded from an initial four permanent constables to nine by the end of the first year, and the head of the force argued that more were always needed, particularly on the thirty-two miles between Sussex and Salisbury, where the "facilities for the protection of the settlers [were] anything but good." The force was large enough, however, to protect those labourers who wished to return to work when the contractor refused to accede to strikers' demands in May 1858, and all of the labourers were soon back on the job. The force was also buttressed by twenty special constables drawn from contractors and their foremen.

On the canals of the Canadas in the 1840s such direct involvement of employers in law enforcement had been questioned as undermining the image of the law as an impartial force and perhaps promoting trouble as much as controlling it. But questions of image and propriety aside, cloaking contractors with the authority of the law had the advantage of drawing into law enforcement men with the most immediate interest in order on the public works and the type of relationship with labourers which allowed them to exact their own harsh forms of punishment such as docking pay, firing, and blacklisting.

A special constabulary was not created to police the Nova Scotia Railway, though the desirability of such a force was debated in the press. Both those papers critical of government officials and those politicians most directly responsible for prosecuting the work argued that all along the line the state of lawlessness had reached such extreme proportions that it would be difficult to find men willing to accept the role: "Constables come out here and go home scared to death." The result? Only "a mad fool" would take a position as railway magistrate in Nova Scotia."

- Ruth Bleasdale, Rough Work: Labourers on the Public Works of British North America and Canada, 1841–1882. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018. p. 233-237.

#construction workers#navvies#canal building#railway construction#regulation of work#strike#working class struggle#railway police#mounted police#province of canada#special constables#nineteenth century canada#strikebreaking#canadian history#working class history#academic quote#reading 2023#rough work#policing the crisis#union organizing#law and order in canada

0 notes

Text

"Through the 1870s and 1880s, recurring debate over weapons control reveals both concern that guns were too readily accessed by the wrong individuals and concern that the state tread carefully in restricting that access. Perceptions of increased gun violence in the streets of large communities, escalating sectarian violence, and fears of civil unrest, particularly during the depression years, provoked calls for the protection of innocent citizens but at the same time warnings against restricting citizens' liberties. The year in which the act to control weapons on public works came into effect, members of Parliament registered concern that a different act, this one directed at the public at large, threatened to infringe on citizens' liberty when it made it a misdemeanor to carry offensive weapons such as pistols and knives unless they were being used at work. The act was considered unenforceable largely because of this infringement on citizens' liberty." Other legislative efforts to combat gun violence in particular ran up against similar concerns to preserve the citizens' ability to carry arms in self-defence and to not be subjected to unreasonable and unwarranted searches of their persons or premises.

In 1877 when Minister of Justice Edward Blake introduced his Bill to Make Provision against the Improper Use of Firearms, he struggled against clearly articulated fears that the rights of law-abiding citizens would be trampled by an unjustified extension of state power in the hands of magistrates given too broad discretion to infer intent. Blake insisted the proposed law would be used to target only two specific groups: "the rowdy and reckless characters" becoming all too common in the streets of major urban centres like Montreal and the boys and young men for whom carrying revolvers had become something akin to a rite of passage, "almost part of their ordinary equipage." Those with legitimate reason to fear for their safety would not be prohibited from carrying weapons, only those with reckless or criminal intent. In the end, however, safeguards to protect the law-abiding from prosecution weakened the bill, and the resulting act was considered by many unenforceable.

When Parliament revisited gun control the following year, with an eye to creating legislation applicable only to designated troublemakers in specific parts of the country as the need arose, and not to the general citizenry, Blake reminded members that the 1869 act to preserve public works provided a Canadian precedent and a template for legislation which could target just one group and thus allay peace on concerns about general disarming of the citizenry on the one hand, while offering an aggressive assault on problem groups and problem areas on the other. In introducing his 1878 Crimes of Violence Prevention Bill, Blake underscored the value of the special law which allowed for extraordinary measures to disarm those who presented an extraordinary threat: in the case of the act to preserve peace on public works, public works labourers in

certain districts in which it was thought possible that owing to the congregation of fluctuating bodies of labourers there might be increased danger to the public peace, and consequently the necessity of increased precautions, increased rigour, and diminution of the ordinary liberties of the subjects of this country.

In backing Blake's proposed legislation, Prime Minister Mackenzie warned that its enforcement would run into the same difficulties as those encountered by the act targeting public works labourers. Those who needed to be controlled would least appreciate and likely oppose attempts at control, as experience with the act to preserve peace on public works had demonstrated:

[W]here there were vast masses of workingmen assembled, who were not, perhaps, as well informed as the other classes of the community, and not perhaps so much above the reach of excitement, which might be brought on by imprudent acts committed by a few persons, it was not easy to obtain that sympathy which was necessary for the observance of the law.

But that made such legislation all the more crucial. In committee, members continued to debate the bill's violation of individual liberties. But the majority agreed with Langevin, who concluded that the violation of liberty was necessary "in order to avoid a greater evil," and they concurred with Devlin, who, as an MP for Montreal, could claim to speak with authority on the situation in that community and who argued that not to pass such legislation "would, in his judgment, be criminal, in fact, on the part of the House."

- Ruth Bleasdale, Rough Work: Labourers on the Public Works of British North America and Canada, 1841–1882. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018. p. 206-207.

#disarming workers#carrying offensive weapons#weapon restrictions#parliament of canada#conservative party of canada#members of parliament#criminal code of canada#gun control#reading 2022#academic quote#rough work#working class struggle#turbulent men

1 note

·

View note

Text

"The sorting of patients into disruptive and calm was an important separation principle in psychiatry. In general, the hospitals were divided into four or five types of wards that each had a particular purpose. The newly arrived patients were admitted to the first of these wards, a “reception and observation department,” which consisted of several large interconnected bed wards where the admitted patients could be constantly observed. The reception wards were divided in two, with calm and disruptive patients kept separately. If the patients’ condition improved, they were often moved to a “transition ward,” where the conditions were a little freer. If there were further improvements, they could be transferred to a “reconvalescence ward,” where the patients were to regain their strength, were active throughout the day, worked and were prepared for discharge. The patients whose illness made slow progress were placed at the “care wards,” which were divided into calm and disturbed. Finally, there were special “sick or invalid departments” that housed hospitalised patients with physical illnesses and the elderly, infirm or senile patients. These wards were also divided the same way as the others. The total number of beds for wards with disturbed patients was 40–50% of the hospital’s beds. The committee whose task it was to investigate the most appropriate layout for a psychiatric hospital believed that this, together with the outdated hospital buildings, was a serious problem.

The committee highlighted that the disturbed wards at some hospitals had become so large, with up to 36 patients on one ward, that it was, among other things, difficult “to create calm in the departments and give the patients a differentiated treatment.” In particular, at the psychiatric hospitals in Viborg and Middelfart the situation was stark, while other institutions such as Aarhus and Vordingborg were better positioned, since modernisations had been carried out a few years earlier. In addition, a number of the hospitals were characterised by being built years ago and were often in buildings that had previously been used for other purposes. The committee emphasised that extensive work lay ahead in which the psychiatric hospitals “to the greatest extent should be designed with the possibility for carrying out modern forms of treatment and examinations."

- Jesper Vaczy Kragh, Lobotomy Nation: The History of Psychosurgery and Psychiatry in Denmark (Springer: 2021) p. 138-193.

#directorate of the state mental hospitals#mental hospital#aarhus#vordingborg#hospital administration#psychiatric clinic#psychiatric power#classification and segregation#danish history#madness and civilization#lobotomy nation#academic quote#reading 2023#history of mental illness

1 note

·

View note

Text

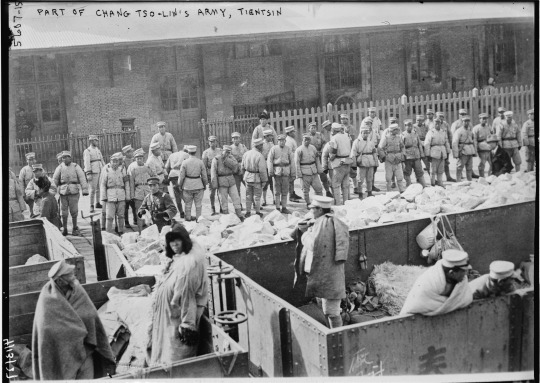

Part of Chang Tso-Lin's Army, Tientsin, April 13, 1922. Bain News Service.

Soldiers of the Northeastern Army 东北军, also known as the Fengtian Army 奉系军 of warlord Zhang Zuolin 張作霖, invading Tianjin on the way to Beijing during the First Zhili–Fengtian War 第一次直奉战争.

Library of Congress, LC-B2- 5607-15. hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ggbain.33489

#tianjin#fengtian army#奉系军#zhang zuolin#張作霖#warlord china#warlord era#republic of china#civil war#first zhili–fengtian war#第一次直奉战争#manchuria

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The Organisation de l’Armée Secrète (OAS) had no such scruples. With General Raoul Salan as its figurehead, this sinister alliance of diehard pieds noirs and mutinous paras and légionnaires turned to indiscriminate terrorism after the failure of its April 1961 uprising. With no real goal beyond the preservation of settler supremacy, its declared enemies included General de Gaulle himself, the security forces, Communists, peace activists (including Jean-Paul Sartre), and, especially, Algerian civilians. (Oddly enough, the OAS seldom confronted the FLN directly.)

In order to disrupt the Evian peace talks between de Gaulle’s representatives and the Algerian leaders, the OAS launched a series of festivals de plastique (380 bombings throughout Algeria in July 1961 alone), using the 4132 kilos of plastic explosive and 1000 electric detonators that it boasted of having liberated from army arsenals. Chief of the OAS’s dreaded “Delta Commandos” was Roger Degueldre, a 36-year-old veteran of Dien Bien Phu who led 500 Légionnaire deserters and Algérie française ultras from his hiding place in the petit blanc district of Bab-el-Oued. In early 1962, as de Gaulle began to yield to FLN demands for complete independence, Salan declared “total war” and ordered Degueldre to unleash the Deltas against both Algeria and France.

….

Although the OAS was effectively decapitated in April 1962 with the arrests of Salan (codename: “The Sun”), Degueldre and other key leaders, the at-large middle leadership – les colonels – was even more fanatically fixated than the generals on provoking an Algerian Götterdämmerung. Their almost insane strategy was to massacre so many ordinary Muslims that the otherwise highly disciplined FLN would be forced to break its truce with French forces and retaliate massively against the pieds noirs. The OAS “bunker,” in other words, was deliberately fomenting a race war that they hoped might topple de Gaulle and lead to a “Rhodesian” or “Israeli” solution."

- Mike Davis, Buda's Wagon: A Brief History of the Car Bomb. Verso, 2017 (2007). p. 42-43

#car bomb#organisation de l’armée secrète#ultras#algérie française#settler colonialism#violence of settler colonialism#algerian war#academic quote#terrorism#decolonisation#pieds noirs#reading 2024

0 notes

Text

"It was at Sing Sing that the instrumentalization of new penological reform found its fullest expression. More than any other prison warden, Sing Sing’s Lewis E. Lawes insisted that the best prison was one in which the prisoners were well-fed, well-exercised, and frequently entertained. Lawes had risen through the ranks of prison administration from the position of prison guard at Clinton, in 1905, to that of Superintendent of the New York Reformatory for Boys, in 1916, and, finally, in 1920, to the wardenship of Sing Sing. He brought with him an unusually acute understanding of the peculiar problems that beset prison administrators in the years after the abolition of prison labor contracting. A first-hand witness to the great disciplinary and political crises that beset New York’s penal system in the early Progressive Era, he also had an intuitive grasp of the “unwritten law” of the prison that the convicts would forcefully defend what they took to be their fundamental rights. Between 1920 and 1943, Warden Lawes carefully and skillfully constructed a prison order based on the principle of the square deal and the morale-building techniques that Moyer had begun to refine at Sing Sing. Grasping that the stability of the prison also depended upon outside forces, he also worked tirelessly to legitimize his administration in a slew of books, articles, radio shows, and Hollywood films.

When Lawes arrived at Sing Sing in 1920 to take up his wardenship, he gave all the prisoners a clean disciplinary slate and placed them in “A” grade. As “A graders,” they were entitled to all entertainment and recreational privileges. Lawes explained that if they broke a rule, they would be demoted to “B” grade, with limited privileges. A further offense would land them in “C” grade, with no privileges. Good behavior would result in promotion to a more privileged grade. As part of this overhaul of the disciplinary system, Lawes reorganized the sale of tobacco and other comforts at the prison, linking the purchase of those “pleasures” to the disciplinary system: He merged the two commissaries to create a single grocery store, and authorized prisoners to purchase a set amount of goods each week, to be determined by the grade they were in. Lawes then set about extending sporting activities at Sing Sing and made the mass media of radio, film, and newspapers part of the fabric of everyday life. He installed a master radio receiving station in the east wing of the prison and appointed a civilian censor, who then relayed selected radio programs to loud speakers and headphone sets around the prison and cellhouse. He also expanded the prisoner baseball program, established a football team, laid down playing fields and handball courts, and gave the prisoners three hours of outdoor exercise time every afternoon in the summer months. Like Moyers and Osborne before him, Lawes continued the practice of having outside teams come to play the prisoners; in 1925, he also organized a memorable ballgame on the prison diamond, between the New York Giants and the New York Yankees (Babe Ruth was reported to have hit the ball over the field wall for a home run; unfortunately, the outcome of the game appears not to have been recorded). Although Lawes understood prisoners’ conception of their elemental rights, he recognized few of these rights as having any basis in positive law (the two he did explicitly acknowledge as properly legal were the right to attend a religious congregation of the prisoner’s choosing and the right to a minimum food allowance.) Nonetheless, Lawes’s actual management of the prisoner indicates that he understood the force of custom in the prisons and that he was very attentive to convicts’ sense of fairness in all his dealings with them.

As at other New York prisons, the new warden retained the Mutual Welfare League (MWL), chiefly as an organizing staff by which to provide entertainments, education, and recreation, and as a disciplinary agency, by which convicts who transgressed minor rules would be policed and punished. Lawes also moved to consolidate his administrative powers viz. the MWL (which, just like outside reformers and embattled politicians, was a potentially disruptive force from the administrators’ point of view). In particular, he took steps to mute the league’s voice beyond the prison walls and to curtail the scope of its activities within the prison walls. The administration clamped down on prisoners’ correspondence with the outside world, and warden Lawes established a censorship office where all prisoners’ outgoing correspondence (whether letters to loved ones or short stories for publication) and incoming mail were scrutinized for subversive content. Lawes also restructured the league’s election process and prohibited the prisoner “political parties” that had emerged in the late 1910s, on the grounds that prison-yard electioneering was overly exciting and emotional for the prisoners, and hence damaging to prison morale. From 1920 onwards, the league’s primary obligation was to regulate the leisure hours of prisoners, Lawes directed; its other obligations were to maintain discipline at these events and to represent prisoners’ grievances and requests to the warden: “The League was to be a Moral force,” insisted Lawes; “If it could not sustain itself in that capacity it was futile and should be eliminated.”

Lawes also maintained the automobile, barber, cart, and tailoring classes and made reading and writing courses compulsory for all illiterate convicts. By 1934, all convicts were routinely administered educational tests. Those achieving lower than the level of the sixth grade were then enrolled in classes taught by a civilian head teacher, two civilian assistant teachers, and twenty grade school convict teachers. Ten prisoners taught more advanced courses, and several convicts were enrolled in correspondence college courses run by the Massachusetts Department of Education. It was under Lawes that psychomedical therapies became a critical component of the disciplinary regime, not merely as a means of classifying prisoners (as the new penologists had initially envisioned them), but as a means of managing convicts’ daily frustrations, depression, and desire to rebel. Like the educational, recreational, and athletic programs, the psychomedical sciences were given over to the therapeutic pacification of convicts. Glueck’s psychiatric Classification Clinic was reorganized and funded by the state in 1926 and proceeded to surveil the entire prison population; clinicians also began attending the warden’s court to give advice on disciplining rule-breakers. Convicts were encouraged to seek psychological and psychiatric advice from Dr. Amos T. Baker and his staff of psychologists and psychiatrists. Throughout his career, Lawes repeatedly made it clear in press releases, radio interviews, and a series of books and articles that high prisoner morale was the immediate objective of his penology, and the peace and security of the prison were his foremost concerns. As he put it in an interview in 1924, under his system:

The men are no longer bottled up, constrained to silence, tyrannized and brutalized by unworthy keepers, or exploited and spied upon. They are permitted some chance of self-expression, some freedom for their personalities. They are shown humane and constructive precepts and they are not repressed, screwed down and baffled. The result is that we have almost done away with those emotional explosions so common in the older kinds of prisons. All acts of violence and attempts at escape are the result of these emotional disturbances.

Lawes conceptualized the various reforms initiated by the new penologists as means to the end of higher morale. On the question of education, for example, Lawes justified the expense of running classes for prisoners: “To me, as a warden, prison schools more than justify their continuance and expansion if for no other reason than to foster and maintain the morale of those prisoners who take advantage of the facilities offered them to study and to learn.” In a similar vein, Lawes argued for the benefits of commercial radio at Sing Sing: “I am happy to report,” he wrote in Radio Guide in 1934, “that since this system has been in vogue, the morale and behavior of the prisoners [have] rocketed sky-ward.” As Lawes conceptualized it, the proper objective of prison management was to facilitate “decent, normal and satisfying expression of personal interests.” This expression was entwined in a system of incentive and privilege that aimed at keeping the convicts more or less happy. Even fire-fighting (for which the convicts were responsible) succumbed to the logic of Lawes’s managerialism. As he wrote, “There is a keen rivalry between the different fire companies and positions on the fire department are frequently given as rewards of merit.” So, too, the death of a prisoner (by natural or other causes) became an occasion for boosting the morale of other prisoners: “When a fellow dies,” Lawes informed an audience at the New School for Social Research in 1931, “whatever his religious belief was, or if he had any, or if he hadn’t, whatever his belief was, it is respected. I don’t know if that helps a fellow that is dead any, but I think it helps the fellows who are left behind” (emphasis added).

Notably, Lawes rarely mentioned the new penological objective of restoring convicts to citizenship. Indeed, he frequently argued that crime originated in the structures and pathologies of modern industrial society itself, and would be eliminated only once those structures were themselves changed. As he saw it, “(u)nder our present social order prisons are a necessary evil.” For Lawes, unlike Osborne and the new penologists, the chief task of prison administration was not to “cure” criminals or deter crime; it was to maintain the peace and security of the prison, both within the institution’s walls and outside, in the large sphere of penal politics.

Although most, if not all, the disciplinary techniques found in Sing Sing and the other New York prisons in the 1920s owed their origins to the progressives, those techniques were being put to different uses and were taking on very different meanings than the ones progressives had intended. At Sing Sing, the enlightened “republic of convicts” became a bargaining table across which prisoners and administrators hashed out a “square deal;” the goal of making good prisoners of convicts usurped that of restoring convicts to manly worker-citizenship. The lament of one new penological investigator, in 1924, was typical:

The emphasis today is laid on the gaining of privileges as a reward for conduct rather than in stimulating the sense of individual responsibility for the common welfare, which is the basis of good citizenship. In one case the privileges are used as a (sic) end in themselves; in the other, merely as the means to a very different, and far greater end.

The disappointed observer concluded that the warden “uses the League chiefly to serve the prison administration rather than uses both the League and Administration to serve society.” Although rehabilitation remained a formal objective of imprisonment, “morale-making” was the guiding principle of the new system. Although both the new penologists and the administrators of the 1920s aimed to produce a prison order in which the convict turned outwards from his self, his soul, or his morbid unconscious and became absorbed in activities that sublimated his mental and physical energies, the new penologists had subordinated those techniques to the overriding objective of socializing prisoners as self-disciplined worker–citizens. After the war, conversely, New York’s prison wardens consistently reiterated that imprisonment’s principal task was essentially managerial in nature: The administrator’s job was to maintain what Lawes referred to as the “morale of the domain” and he was to achieve this by establishing various activities that sublimated the passions and desires of the prisoners.

The morale of the domain depended upon prisoners and keepers entering a double relationship of exchange. On the one hand, prisoners exchanged their good behavior for “good-time”: That is, if they behaved well, they would regain their liberty sooner. In the meantime, they also traded obedience for the gratifying privileges of attending (or playing in) convict baseball matches, watching movies, making use of psychiatric counseling services, and purchasing tobacco and other small pleasures from the prison commissary. Radio, cinema, recreational activities, athletics, access to a well-stocked grocery, and therapy were all part of one pervasively psychological penal order of sublimation. These various activities were comforting commodities to be purchased with the only hard currency a prisoner possessed: obedience. Lawes did not hesitate to plainly state this point: “Naturally the convicts have to pay some price for the possession of such a cherished bounty. The asking price is a matter of obedience.” At Sing Sing, in particular, but to a significant degree in Auburn and Clinton as well, prison order came to rest on a more or less tacit agreement between prisoner and keeper that the former could purchase some measure of pleasure from the latter by resisting the urge to cause trouble. Morale-building, as a technique of maintaining peaceful institutions, took the place of moral reform.

Within a few years of arriving at Sing Sing, Lawes had completed the transformation of the original new penological project into a new, managerialist penal order. Although elements of this penal managerialism could be found in other New York prisons (and in a number of other states, including Texas, Minnesota, Illinois, and California), nowhere was it as fully and systematically developed as at Sing Sing. In the few years either side of 1930, three separate, though related, strings of events – the Baumes laws, prison riots at Auburn and Clinton prison (but not at Sing Sing) and federal regulation of prison labour - would propel Lawes’s system to national notice and reinforce the relevance and utility of penal managerialism."

- Rebecca M. McLennan, The Crisis of Imprisonment: Protest, Politics, and the Making of the American Penal State, 1776-1941. Cambridge University Press, 2008. McCormick, p. 443-449.

The photo shows an officer instructing a Sing Sing prisoner on bed-making, from Lewis E. Lawes, Twenty Thousand Years in Sing Sing. New York: A. L. Burt Company, 1932, p. 176.

#sing sing prison#penal reform#penal modernism#managerialism#prison discipline#prison administration#crisis of imprisonment#new york prisons#classification and segregation#mutual welfare league#sports in prison#history of crime and punishment#academic quote#reading 2023#psychiatric examination#prison psychiatry#lewis lawes

1 note

·

View note

Text

"Much of the canal labourers' reported drinking consisted of the payday binges common among both skilled and unskilled workers. The release from work in bouts of hard drinking was a time-honoured and, in the right hands, tolerable tradition. Though these drinking bouts were under attack from temperance advocates and other members of respectable society, they remained common practice among segments of the working class through the latter half of the nineteenth century. The sheer numbers and concentration of construction labourers, however, gave to their payday binges a particularly frightening edge. The first payday on the Welland in 1873 offered the surrounding community a foretaste of future problems. With all the appearance of a "jamboree," labourers took over the bars and served themselves, ran the city, and drank their way through the town's supply of alcohol, though they were careful to pay their way. According to the Welland Tribune, these sprees followed a long dry spell: "Dry as a sponge after a month's forced abstinence," labourers settled their accounts for board and lodging and then descended on taverns and hotels." Repeated each month, these binges became an expected, if not welcome, part of the construction process.

From the more isolated Grenville, reports of payday binges emphasized less the threat to the peace of the community and more the disruption to the work. In the early months of construction before the supply of labour became more plentiful, the contractor claimed that problems in maintaining an adequate labour force were compounded by the opportunities for heavy drinking in the area. When the Department of Public Works recommended paying the workers more frequently to make the job more attractive, Goodwin countered that he had no problem with paying as often as once a week, but that would only create another problem. As it was, he lost too much time to the men's monthly drinking binges. More frequent payment would increase those binges to the point that "it would be impossible to keep the men at their work" Of course, contractor Goodwin had his own reasons for preferring the longer interval between paydays, not to an important point, nonetheless, for those who tied excessive drinking to paydays. From his perspective, unless the means could be found to stop or at least regulate the sale of alcohol, the choice appeared to be between a small workforce sober much of the time and a larger workforce too frequently drunk.""

- Ruth Bleasdale, Rough Work: Labourers on the Public Works of British North America and Canada, 1841–1882. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018. p. 196

#construction workers#navvies#canal building#railway construction#payday#binge drinking#working conditions#working class culture#working class struggle#nineteenth century canada#social history#canadian history#working class history#academic quote#reading 2023#rough work#welland canal#welland

0 notes

Text

"While the war raged in Europe, psychiatrist Arild Faurbye, together with three colleagues, introduced electro-convulsive therapy at Bispebjerg Hospital’s Psychiatric Department in Copenhagen. Faurbye had been in the audience at Cerletti and Bini’s lecture at the congress, where he had understood the interest in the new treatment. Shortly after, he employed a Danish civil engineer to construct an electroshock device based on the Italian example and received an experimental device with a transformer that could deliver a voltage from 0 to 150 volts. The shock was given as an alternating current via two electrodes, which consisted of two zinc plates of 4 × 5.5 cm with gauze that was smeared with a glycerine ointment and fastened using a rubber band around the patient’s head.

Having received the device, the first treatment at Bispebjerg Hospital was performed on 15 November 1940, and in the following two months 200 electro-convulsive treatments were given to 26 patients. In the first attempts, Faurbye and three other psychiatrists from Bispebjerg Hospital noted in the patients’ records that there were improvements in a little under half of the patients, but they did not report of actual recoveries. The results were assessed based on experiences with Cardiazol shock therapy. At Bispebjerg, the doctors concluded that “all in all it appears to us that electro-convulsive therapy has the same effect as Cardiazol and is not subject to many of the Cardiazol’s drawbacks.”

In the Directorate for the State’s Psychiatric Hospitals, the new treatment method was noticed by the director, Georg Brøchner-Mortensen, who in the beginning of 1941 contacted chief physician Max Schmidt from Augustenborg Psychiatric Hospital. The directorate’s director wanted to hear Schmidt’s assessment of the new treatment, since he knew that two doctors from Augustenborg had previously visited Bispebjerg Hospital to observe the electro-convulsive therapy.

In his reply, Schmidt highlighted that there appeared to be certain advantages with electroshock but that with each new treatment there was always an associated risk that in “the case at hand could not easily be over-looked.” The existing knowledge on the effect of electricity on the human body could not be considered to be exhaustive, and there had been “an inexplicable death in connection with the treatment” at Bispebjerg.Hospital. Since he at the same time found that the Cardiazol treatment in Augustenborg worked well, and since he “did not like the matter of death,” he had refrained from introducing electroshock therapy.

Financial circumstances had also contributed to Max Schmidt’s reluctance, and he had assessed that it was not possible to make any savings by using electro-convulsive therapy instead of Cardiazol. But after Brøchner-Mortensen’s enquiry, he had begun to calculate the costs again and had reached the conclusion that electroshock would be cheaper in the long run. In his letter, he therefore ultimately recommended for electroshock therapy to be thoroughly tested in at least one of the state psychiatric hospitals.

Max Schmidt—after applying a great deal of pressure himself—was assigned the task by the Directorate of the State Mental Hospitals, and on 3 October 1941 he was able to start the first test of the treatment. Thereafter, he kept the Directorate informed of the progress, and in his letters, he was able to report good results. Electro-convulsive therapy was thought to be just as effective as Cardiazol, induced less angst in the patients and caused slightly fewer physical injuries. In relation to Cardiazol, there was also “a considerable time-saving,” since, for restless patients, it was not necessary to have “a significant number of care workers to strap down the patient” and the electroshock could be carried out before the patient was “aware of what lay ahead.” Therefore, in the beginning of 1942, Max Schmidt warmly supported the new treatment and suggested to the Directorate that the other hospitals should also benefit from it.

At a chief physician meeting on 27 January 1942, Schmidt presented electroshock therapy to the other senior consultants from the state mental hospitals, and everyone was very positive regarding the new method. After the meeting, when the Directorate’s director was willing to provide money for the treatment, all the chief physicians wanted two or three electroshock devices available at their hospitals. Comprehensive electrical work was however needed so that all the hospitals were able to use the Swedish devices that had been chosen for the treatment. Therefore, the Directorate applied for additional funding, which was granted by the Ministry of Finance on 4 March 1943. Subsequently, electro-convulsive therapy could take its place in all the state psychiatric hospitals.

Just like the previous physical treatment methods, electroshock therapy quickly became popular among psychiatrists at the psychiatric hospitals, and it also received a warm welcome among the general public. The treatment was praised by popular magazines such as Billed-Bladet, which in 1943 visited Augustenborg Mental Hospital and received a demonstration of electroshock therapy as the latest breakthrough in psychiatry. And Danish newspaper readers were also informed of the new treatment. In the newspapers, electro-convulsive therapy was portrayed positively, even though the journalists also discovered that, as a treatment, electric shocks were rather dramatic in nature.

However, even when the journalists witnessed electroshock therapy— and did not simply refer to doctors’ statements—they were not negative regarding the treatment (the press’ critical attitude towards electroconvulsive therapy first came later). As was the case with a journalist in May 1950, the press occasionally witnessed demonstrations in electro-convulsive therapy at state mental hospitals. That year, the journalist had been given permission to be present at the shock therapy on one of the departments at psychiatric hospital in Middelfart and in a detailed account described the process surrounding the treatment in the newspaper Fyns Social-Demokrat:

The midday siren rang out from the top of the kitchen building, but the ambulatory patients return only reluctantly from the arts and crafts rooms. They know that the department is at the other end, because it is shock day! In the long corridor, no nurses are to be seen. They are all inside to assist on the shock wards – the two small rooms that have been cleared, making six patients homeless until late in the afternoon. At a long table, a number of patients are sitting and eating lunch. Others are waiting to talk to the doctor. Those who will have shock treatment are in their night clothes with a blanket over them. If they have not been lethargic before, then they are now completely empty in the eyes after a restless night and a morning’s anxious wait – all on an empty stomach. (...)

The door to the office springs open and a whole procession, with doctors leading the way, turns in to one of the shock wards. At the end, the shock device is rolled in. And the door is shut. The treatment happens as if it is on a conveyor belt. The first patient is treated in the bed by the window, a screen in front, the next patient is called in, another screen in front – but when number three comes to the door it can well be that the first patient by the window has woken up after the shock. And it is not nice to lie there after a shock and hear another patient’s unconscious screams from the seizures. It is not nice at all ...

Even at the lunch table out in the corridor, one cannot escape the seizure screams. The newly arrived stare terrified at the treated patients, who are supported by nurses as they are led back to their own beds. They do not know that these exhausted, unwell people will most often laugh and talk merrily by the evening. Nonetheless, this is the most natural. The shock therapy can seem like a complete miracle.

The journalist concluded the article, entitled “Electric shock can lead the mentally ill back to life,” by saying that it “is really a fact that psychiatric hospitals the world over are able to send several hundred patients home cured every year – only because of a couple of electrodes’ miraculous effect."

- Jesper Vaczy Kragh, Lobotomy Nation: The History of Psychosurgery and Psychiatry in Denmark (Springer: 2021) p. 132-136.

#shock therapy#electroconvulsive therapy#electroshock therapy#bispebjerg hospital#psychiatric clinic#psychiatric power#danish history#mental hospital#madness and civilization#lobotomy nation#academic quote#directorate of the state mental hospitals#copenhagen#reading 2023

1 note

·

View note

Text

What was the licensing system for?

"Although the repatriation of the licensing system following the end of transportation seems to have been, at least in part, an unthinking policy reflex, as the system persisted through the nineteenth century, it appears to have offered three distinct advantages to the authorities.

First, it reduced costs to the extent that it made the convict prison system more affordable. At between £32 and £42 a year, the average cost per convict was remarkably stable between 1856 and 1914. This cost approximately doubled in the wake of World War I, but it was only in the 1930s – a time when the convict population was much smaller – that it rose significantly. After the prison closures of the inter-war period, the cost was, on average, £140 per convict. The total cost of the system was, of course, affected by the number of people consigned to convict prisons. Although there were fluctuations in numbers and therefore costs, the system as a whole was expensive. Between 1856 and 1940, the average cost of the convict prison system was £218,000 per year. By the start of World War II, the cost of the overall system was still £240,000 per year, not far off from the £226,000 it had cost to run in 1856. In the post-World War II period, the cost rose steeply once more. The prison system has always been (and continues to be) very expensive. However, its costs were considerably lightened by the licensing system. Without a licensing system, the average daily prison population would have increased by one-quarter to one-third, as would the financial costs of running the convict prisons.

The licensing system operated like a pressure valve that made the convict prison system manageable and able to operate at a much-reduced cost. Between 1870 and 1885, when the long stretches handed to people sentenced under habitual offender legislation inflated the convict population, the licensing system saved the authorities close to one million pounds. After 1882, convict establishments largely became net exporters of prisoners, and the licensing system continued to save a considerable annual sum for the prison estate. The proportion of a penal servitude sentence that needed to be served before release on licence was formalized in 1853, long before the prison crises of the next three decades, but the impact of reducing the number of licences granted between 1856 and 1859, and the concomitant rise in the prison population, must have been a lesson for the authorities. The system could be viewed as an elegant mechanism for the authorities, allowing them to reduce costs whenever the system became bloated with convicts by releasing more and more men and women on licence. The system had not been conceived as a cost-saving device, but it was quite evidently operated in that way, making the convict prison system as a whole financially viable.

Second, the promise of a licence being dangled over prisoners’ heads helped to keep order inside the prisons. In Walls Have Mouths, former convict McCartney wrote that ‘a good prison record means that the convict is at the beck and call of every jailer in the prison, that he has to suffer every indignity and injustice in silence, that he cannot associate himself with any complaints, and that he has to do whatever is convenient to the warders, otherwise he gets a bad report, and that report may militate against him to the extent of an extra five years in prison’. The explicit and implicit threat of the loss of remission was one way of keeping discipline in a prison, especially as it would have inculcated self-government among convicts.

Lastly, the licensing system allowed the prison authorities to put right obvious errors that might have undermined the legitimacy of the criminal justice system. This was especially important – or, indeed, may have only been important – when glaring miscarriages of justice attracted attention from the media or from politicians. For example, George Whitehood and Charles Holden were charged with the arson of three haystacks at Hayes on 25 October 1869. In court, Holden stated that ‘he would rather be in prison than not, walking about with nothing to eat’, and he received a ten-year sentence at the Old Bailey on 22 November 1869. Whitehood, however, who may well have been in the same state of poverty, desperation, and disillusionment as Holden, had difficulty proving that he had been anywhere near the crime scene. He had only been liberated from Wandsworth Prison at 9.30 a.m. on the day of the fire and could not possibly have walked to Hayes (a five-hour journey) by the time the fire was started (just after midday). The judge at the Central Criminal Court believed Whitehood had confessed to the crime in order to be transported – if Western Australia was no longer an option, perhaps he was thinking of Gibraltar (where penal servitude continued until 1875), although the judge seems to have been unclear about the options. Whitehood’s case was taken up by the governor of Brixton Prison and the Home Office, who were on firmer footing in correcting the error through the licensing system. Whitehood, having served less than a year of his ten-year sentence, was given a licence in 1870. ‘If he commits another offence it will subject him to imprisonment in, and not removal from this country,’ stated the governor. Whitehood never reoffended, but without the intervention of the prison authorities he would have served another six years in prison before becoming eligible for release on licence. It should be noted that Whitehood’s case had been taken up by MPs in the House of Commons, no doubt putting pressure on the Home Office to act. The number of highly visible cases were few, and therefore one assumes that the number of ‘corrections by licence’ were similarly few.

For most people on licence, it served one very real and valuable purpose: it got them out. As the outpouring of emotion at the beginning of this chapter from people about to be released from prison attests, this purpose should not be underestimated. However, there was not much support with regard to rehabilitation while on licence, and, indeed, there were many barriers to reformation that the system itself put in the way of anyone attempting to ‘go straight’. The authorities were more than aware of the stigma attached to those who had been in prison. The Penal Servitude Acts Commission of 1863 reported that it was ‘far from confident that persons in this condition would find it easy to obtain an honest livelihood. Men with characters branded by their having been convicts are exposed to insuperable disadvantage, in the strong competition for employment.’ This issue was also a topic of considerable discussion by the Kimberley Commission fifteen years later. Several ex-convict witnesses who gave evidence objected to police supervision on the grounds that police officers informed their employers of their status as ex-prisoners and this resulted in the termination of their contracts. Representatives of the Royal Discharged Prisoners Aid Society also put forward a few examples in which this had been the case. A number of male and female convicts in our study also claimed to have experienced this problem. The commission recommended improving the system of supervision in this regard, arguing in line with the 1863 commission that

no time should be lost … in improving the present system. We fear that supervision, if left in the hands of ordinary police constables ... will tend more and more to become a mere matter of mere routine, harassing to the men who are subjected to it, and affording no real security to society against the criminal classes.

However, the licensing system did reduce the period in custody and thereby gave people more time to do the ordinary things that other Victorians and Edwardians did: form relationships, marry, settle down, and have children; find work and build a career or at least have a steady form of income; build relationships and put down roots in a neighbourhood after establishing a secure and stable residence; and take responsibility for one’s own actions, rather than being told what to do and when to do it. All of this helped to build maturity and foster self-reliance and responsibility. These structural factors operating at the individual level encouraged rehabilitation and desistence from offending, but they took time – time that was given back to convicts through the granting of a licence. Although it offered significant financial and operational benefits to the convict prison system, the licensing system was of no intrinsic value to individual convicts, except as a temporal window that allowed more supportive processes to get to work beyond the prison gates."

- Helen Johnston, Barry Godfrey and David J. Cox, Penal Servitude: Convicts and Long-Term Imprisonment, 1853–1948. Kingston and Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2022. p. 147-151

#convict prison#uk prisons#parole#parole system#prisoner release#convict license#penal reform#sentenced to the penitentiary#prison discipline#penal servitude#academic quote#history of crime and punishment#reading 2023#prison administration

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The reach of the law [in 19th century Britain] was extended through several means. The best known is the creation of professional police forces, urged and supported by most law reformers. Peel's Act of 1829 established the metropolitan police, providing a model of a force consisting of a larger number of constables, set apart from the population by uniform and discipline and pressed to be more active and less discretionary than their predecessors. Acts of 1835, 1839, and 1856 first encouraged and then required the creation of county and borough police forces on that model. As police forces grew, the summary jurisdiction of magistrates also expanded, capped by a series of acts between 1847 and 1855 making it possible to process a much higher caseload without creating many expensive new courts. Enforced by professional police and harder working magistrates, the law became less discretionary and less tolerant, pulling in more and more lesser offenders - vagrants, drunkards, prostitutes, and disorderly juveniles. Many of these offenses had traditionally been ignored by the authorities. A police commissioner reflected in the more settled situation of 1880 that "The Metropolitan Police in their early days were rather over enthusiastic in enforcing the law and dealing with minor offences." This widened activity of the criminal law embraced not only apprehension and trial, but conviction and punishment for offenses that, as the first prison inspectors noted in 1836, "were formerly disregarded, or not considered of so serious a character as to demand imprisonment." " The sharpest rise in prison admissions came not for serious felonies, but for petty felonies and misdemeanors. Not only were more people being taken into custody, many more also were being summoned by magistrates for public order and nuisance offenses; the number of summonses issued in London rose faster than the population until the early 1870s. Clearly, during the first half of the century and beyond, governmental intolerance for popular immorality and disorderliness, however minor, was on the rise.

- Martin Weiner, Reconstructing the Criminal: Culture, Law, and Policy in England, 1830-1914. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990. p. 50-51.

[More 'efficient' police functionally creating more crime and more criminals by broadening who was considered a criminal and who would be identified, caught and punished.]

#law and order politics#professional policing#police reform#criminal justice reform#war on crime#build it and they will come#british history#history of crime and punishment#liberal era#academic quote#reading 2022#reconstructing the criminal

1 note

·

View note

Text

"Coordination and regimentation were crucial to the efficient deployment of men labouring at close quarters on interrelated tasks. Along the more isolated excavations and embankments or on any section where the workforce was thinly stretched, close surveillance was difficult, but ideally it was built and maintained through a rigid hierarchy of supervision moving up through gangers and foremen to the section supervisors who patrolled the work. At mid-century a gang of roughly seven to fifteen members worked to the rhythm set by the ganger tasked with maintaining the pace of the work and paid at a higher rate to ensure his commitment to the contractors interests. On some private railway projects in British North America during the 1850s, gangs were modelled sometimes on the "butty gangs" of Britain's early railway age. The aristocrats of the pick and shovel, members of butty gangs either formally subcontracted for a quantity of the work or worked collectively at piece rates. They were only indirectly responsible to the contractors' supervisory personnel and consequently enjoyed considerable independence on the job. On public works by mid-century the relative independence of the butty gang appears to have been reserved for small groups of skilled workers. For the unskilled, division into gangs was a means of supervision, not a measure of autonomy.

How gangs formed, how long and at whose discretion they remained together, and whether the gang travelled as a unit from project to project were questions of fundamental importance to the labourers. The men with whom they worked most closely helped determine not just quantity and quality of their output but also the tone of interpersonal relations on the site and the labourers' capacity to survive them without injury. The composition of gangs in industries such as long-shoring, mining, and lumbering suggests the likelihood that labourers themselves played an important role in determining those who worked alongside them. Likely they preferred to labour beside those whose work rhythms and proficiency they had learned to trust, and experienced contractors and supervisory personnel would have seen the advantages to gangs whose productive capacity was well oiled by familiarity, provided that familiarity did not undermine the author ity of those pressing the work. Pragmatism would also have endorsed what the gang members of the 1840s and 1850s clearly embraced, the opportunity to work with those whose language they readily understood. How strong that preference remained into the 1870s is less clear. The familial and kinship ties which helped define immediate workmates in mining and longshoring probably were also important among labourers on construction sites. Bonds of family and kin within gangs are suggested but confirmed only in rare images: of one family's relief when two brothers escaped a cave-in on the Lachine in January 1877; of another family's grief compounded when the same cave-in claimed brothers-in-law working side by side."