#siegfried kracauer

Text

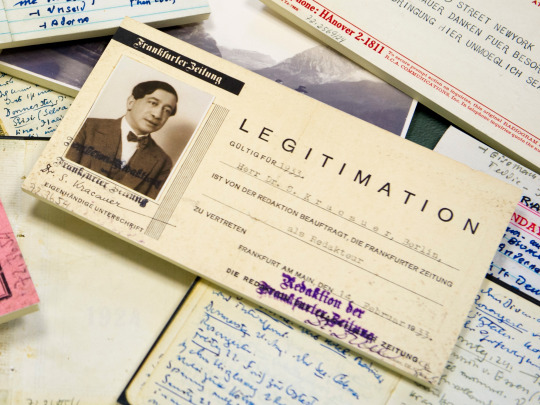

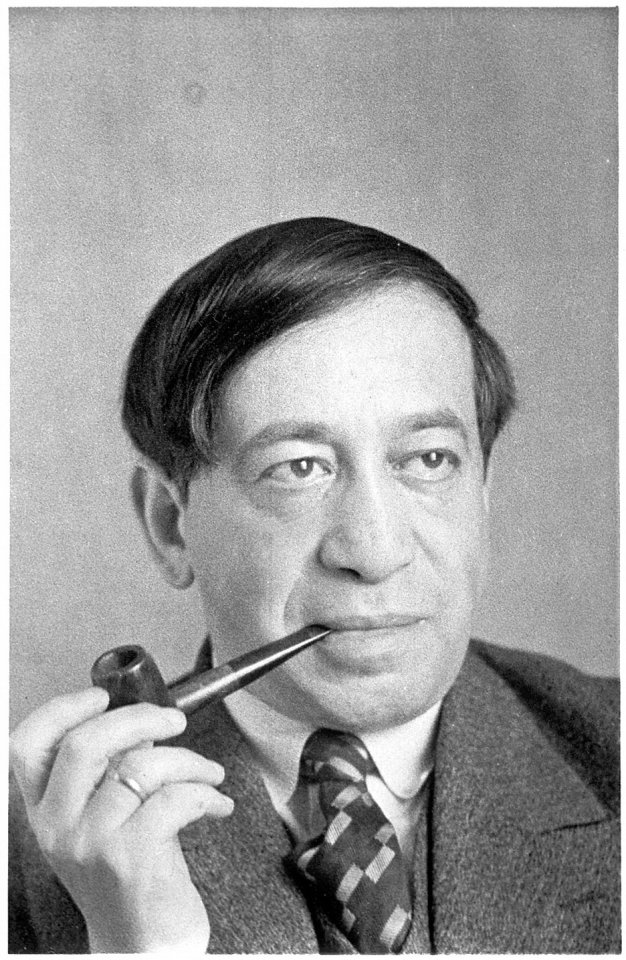

Siegfried Kracauer, February 8, 1889 – November 26, 1966.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

les nouveaux messieurs, jacques feyder 1928

#les nouveaux messieurs#jacques feyder#1928#opening sequence#siegfried kracauer#von caligari zu hitler#der schock der freiheit#1947#edgar degas#picadilly#il conformista#the black swan#summer interlude#scenes from a marriage#strohfeuer#brazil#карнавальная ночь

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Der müde Tod (Fritz Lang, 1921)

“It is as if the visuals were calculated to impress the adamant, awe-inspiring nature of Fate upon the mind. Besides hiding the sky, the huge wall Death has erected runs parallel with the screen, so that no vanishing lines allow an estimate of the wall's extent. When the girl is standing before it, the contrast between its immensity and her tiny figure symbolizes Fate as inaccessible to human entreaties. This inaccessibility is also denoted by the innumerable steps the girl ascends to meet Death.”

Siegfried Kracauer, From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film, 1947.

#siegfried kracauer#fritz lang#der mude tod#destiny#film#classic film#silent film#silent era#german film#weimar cinema#1920s#my screencaps

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is the unmasking of certain ideologies (which many people do not even clearly acknowledge) an indication of the weakening of bourgeois consciousness? In any case, the fact that the higher strata have fallen silent contributes to the radicalization of the younger generation. You can't live on bread alone, particularly when you don't even have any. Even right-wing radicals have partially freed themselves from a bourgeois mindset which they feel does not serve them well. But theirs is an emancipation in the name of irrational powers that are capable of reaching a compromise with the bourgeois powers at any time. The larger masses of the middle class and the intellectuals do not, however, participate in this mythical rebellion, which rightly strikes them as a regression. Rather than allowing themselves to be forced by the spiritual void (which reigns in the upper regions) to break out of the corral of bourgeois consciousness, they instead use all available means to try to preserve this consciousness. They do this less out of real faith than out of fear—a fear of being drowned by the proletariat, of becoming spiritually degraded and losing contact with authentic aspects of culture and education. But where does one find reinforcements for the threatened superstructure? The latter now lacks various material props, and the newly emerged strata that consider themselves part of the bourgeoisie are not its obvious supporters. They do not have any idea where they belong, and are merely defending privileges and perhaps traditions. The important question then is: How are they fortifying their position? Since under the present conditions they cannot simply adopt the inventory of bourgeois consciousness as such, they have to resort to all kinds of alternatives in order to make it seem as if they still wield their former spiritual/intellectual power.

Siegfried Kracauer, The Mass Ornament: Weimar Essays

#siegfried kracauer#philosophy#mine#popping into the ghost world to let him know that yeah they're doing it again no I don't know why#do they still like stalin well that's a bit complicated

10 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Aussi notre auteur, comme de juste, reste-t-il pour finir un isolé. Un mécontent, pas un chef. Pas un fondateur : un trouble-fête. Et si nous voulions nous le représenter tel qu’en lui-même, dans la solitude de son métier et de ses visées, nous verrions ceci : un chiffonnier au petit matin, rageur et légèrement pris de vin, qui soulève au bout de son bâton les débris de discours et les haillons de langage pour les charger en maugréant dans sa carriole, non sans de temps en temps faire sarcastiquement flotter au vent du matin l’un ou l’autre de ces oripeaux baptisés « humanité », « intériorité », « approfondissement ». Un chiffonnier, au petit matin – dans l’aube du jour de la révolution.

Walter Benjamin, évoquant le travail de l’écrivain Siegfried Kracauer: “Un marginal sort de l’ombre”, in Œuvres II, Gallimard Folio, 2000

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fast schade, dass Kracauer sich nicht beim Beobachten beobachtet hat.

1 note

·

View note

Text

[…] aveva tentato di produrre, a partire dal materiale disponibile negli archivi di immagini, dei cinegiornali che avessero davvero a che fare con le nostre faccende. Dovette accettare diversi tagli dalla censura e non ha resistito a lungo. In ogni caso, questa esperienza ci insegna che, se composte in modo differente, le immagini dei cinegiornali ne guadagnerebbero una maggiore acuità visiva (Schaukraft)”65.

Siegfried Kracauer

0 notes

Text

youtube

TODAY IN PHILOSOPHY OF HISTORY

Siegfried Kracauer and the Practicing Historian

Thursday 08 February 2024 is the 135th anniversary of the birth of Siegfried Kracauer (08 February 1889 – 26 November 1966), who was born in Frankfurt am Main on this date in 1889.

Kracauer, and Paul Oskar Kristeller commenting on Kracauer as his editor, prefers the working historian as his guide to philosophy of history, rather than the philosopher of history himself, but what exactly do we gain by appealing to the working historian? Do the historian and the philosopher represent what S. J. Gould called non-overlapping magisteria, or is the philosopher free to impose his philosophical thought on the historian, and, vice versa, the historian is free to propound his own philosophy of history?

Quora: https://philosophyofhistory.quora.com/

Discord: https://discord.gg/r3dudQvGxD

Links: https://jnnielsen.carrd.co/

Newsletter: http://eepurl.com/dMh0_-/

Podcast: https://podcasters.spotify.com/pod/show/nick-nielsen94/episodes/Siegfried-Kracauer-and-the-Practicing-Historian-e2fifm4

#philosophy of history#Siegfried Kracauer#Paul Oskar Kristeller#practicing historian#working historian#Youtube

0 notes

Text

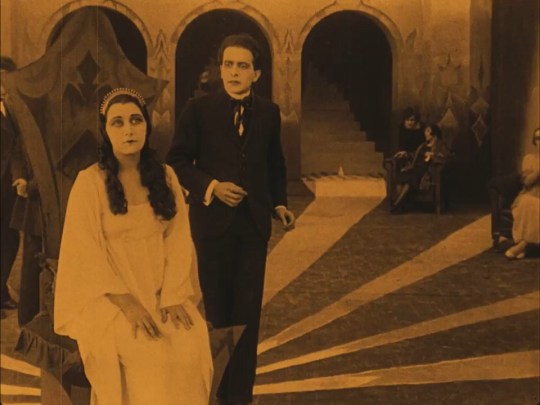

Conrad Veidt and Werner Krauss in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (Robert Wiene, 1920)

Cast: Werner Krauss, Conrad Veidt, Friedrich Feher, Lil Dagover, Hans Heinrich von Twardowski, Rudolf Lettinger. Screenplay: Carl Mayer, Hans Janowitz. Cinematography: Willy Hameister. Production design: Walter Reimann, Walter Röhrig, Herrmann Warm.

I don't know how many years ago I first saw The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari on television or in some university film series, but I remember finding it rather silly and quaint. In the meantime I have grown more serious-minded about movies and the film has been carefully restored: The flickering black-and-white images I must have seen have been replaced by smooth digitalized projection and the appropriate color filters, as well as the original hand-painted intertitles, and an appropriately spiky modern score by John Zorn has been added to some prints. It's clearly a classic, both of its time and enduring into future times. The film has been endlessly analyzed, most notoriously by Siegfried Kracauer in his 1947 book From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film, in which Kracauer posits that the film reveals post-World War I Germany's subconscious desire for an authoritarian leader. In other words, Caligari equals Hitler. Considering that in the film Caligari, played by Werner Krauss, looks both sinister and absurd, something like an elderly owl in a top hat, I find the argument hard to swallow. But this is one film that will probably never exhaust interpretation. I think it's best just to enjoy it as a tremendous artistic experience.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

There's nothing more inane when talking about cinema than people complaining about how even the smallest details in a film aren't realistic and how that lack of realism automatically means that said film is bad.

This discussion dates back to the 1940s when Siegfried Kracauer drew a line between the two approaches to filmmaking: formalism and realism. Formalism is stylized and has exactly zero interest in representing reality. When adhering to the latter though, a director wants the film to resemble reality so real life settings and extended cuts are used. Most contemporary films fall somewhere in the middle of this particular spectrum. A lot of artists lean towards realism, 'cause this form asks less of its viewers. The thing is, it doesn't matter whether films are realistic or not. What matter is how realism is used in them. Did the artists use it in ways that delivered an emotionally compelling story? Did they manage to succesfully get across whatever it was they were trying to convey?

Movies are not documentaries. There's a thing called poetic license. Let the tale seduce you and stop nitpicking everything.

There are genre conventions. For example, musicals can't be naturalistic since people in the real world don't spontaneously break into song. Maybe a particular genre isn't for you and that's okay.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Siegfried Kracauer, February 8, 1889 – November 26, 1966.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

das cabinet des dr. caligari, robert wiene 1920

#das cabinet des dr. caligari#robert wiene#1920#willy hameister#conrad veidt#werner krauß#lil dagover#friedrich fehér#caligula#fellinis casanova#das wachsfigurenkabinett#m#about photography#obst & gemüse oder der kunde ist könig#frühlingssinfonie#twelve monkeys#the cell#von caligari zu hitler#siegfried kracauer

1 note

·

View note

Text

Sara Reads an Infuriating Book, part 2

Chapter 2 of W Scott Poole's Wasteland is entitled "Waxworks". This is where I got angry enough to start taking notes in earnest rather than just annotating the ebook, so this is longer and has more actual quotes.

First, a disclaimer: I do not in any way disbelieve that WWI had a huge impact on early 20th century horror. Of course it did; how could it not? What I object to is Poole's assertion that it is the only thing that could possibly have had such an impact and that that impact always and only comes in the form of fear of bodily death and the corpse as an object of horror. Any time anyone gives you a Grand Unified Theory of Horror that claims to explain all of reasons that humans create scary or disturbing art, that theory is never going to be correct. People are more complex than that. And now, bullet points!

Okay, first off, I do have to apologize for ranting about Poole talking about Machen's "The Bowmen" without actually talking about it last chapter, because he talks about the story explicitly in this chapter. This is a structural thing he does repeatedly: he'll mention a writer/director/etc and hint at a work he's going to discuss later without actually naming it. (In this chapter, he does this with Fritz Lang and Metropolis.) This structural choice is not well-signposted and I don't care for it, but at least now I know that's what he's doing.

He also touches on Lovecraft again here, so I apologize as well for accusing him of skipping ol' Howie. Here, we talk briefly about "Herbert West: Re-animator", as it's the only Lovecraft story to a) actually feature WWI explicitly and b) deal much with corpses. There's also this quote about Cthulhu which is...a big fucking stretch: "He raised great Cthulhu, a monster that has haunted the century, a new death’s head spreading wide his black wings of apocalypse, which was clearly recognizable as the Great War and its meaning continued to menace the world."

Like, there is absolutely an argument to be made that WWI was a major influence on the invention of cosmic horror at the beginning of the 20th century. Again, how could it not be? WWI was proof for a lot of people that the universe fundamentally didn't care about them. But that's the thing that I don't think Poole gets - cosmic horror is not about the fear that you are going to die. Cosmic horror doesn't care about your corpse because it doesn't care about you. Cosmic horror is about the fear that no one cares that you exist at all. That is a huge and important difference.

As the chapter title implies, there is a lot of repeated discussion this chapter of waxworks, dolls, puppets, poppets, etc. Poole insists over and over again that a) all of these simulacra can be collapsed symbolically into a single image and that image is of a corpse and b) these objects became horrific after WWI because of the corpse thing. But then he'll go through the history of the fascination with creepy wax figures stretching back to wax images of saints through Madame Tussaud's Chamber of Horrors, or he'll talk about dolls and reference E T A Hoffman's The Sandman (from 1817), which, to my mind, totally undercuts his point. You don't need the Great War to make waxworks creepy, my dude.

(Somewhat relatedly - there is a really interesting book to be written about the prevalence of hypnotism/mind control/sleepwalking in early horror film, but it is not going to be this book because Poole thinks all that's happening there is more corpses.)

Which leads us to the discussion of The Cabinet of Caligari! Poole spends a lot of time rehashing a widely accepted interpretation of the film proposed by Siegfried Kracauer in his 1947 book From Caligari to Hitler: Kracauer reads the film as a warning about the dangers of authoritarianism, with the somnambulist Cesare standing in for the people of Europe who unconsciously do the evil bidding of their authoritarian masters. Not saying that's the only possible reading of the film - I don't believe there's only one possible reading of any film - but it's an interesting and persuasive one. 'Nope!' says Poole. See, his theory is that the filmmakers wanted to get artist Alfred Kubin to design the look of the film (he did not end up working on the film), Kubin's work has a lot of doll-like figures in it, dolls are always corpses, and therefore Caligari is, once again, only about how all those people died in the war. This is the only thing the filmmakers could have meant.

(On the positive side, this did lead me to look up the art of Alfred Kubin, which I was previously unfamiliar with. It's pretty rad.)

"There’s not enough evidence, for example, that the world understood that their somnambulistic obedience helped produce the outrages of the Great War." I don't see that the world as a whole has to see that in order for the film to attempt to convey that meaning - surely what matters is that the filmmaker saw it and made a film about it. It's not necessary for the world to understand the meaning behind a work of art for a person to make that work of art.

(Somewhat ironically, Poole complains that Kracauer is only capable of interpreting German film in the 1920s through the lens of his pet theory. Who does that remind me of? Couldn't say.)

Oh my god this is already so long, I haven't even talked about J'accuse. Poole thinks J'accuse is a zombie movie which I won't argue because I've only read about it and haven't seen it yet - that could be a valid interpretation for all I know. But then he compares it unfavorably to Romero zombie films and complains that the director of J'accuse "did not really know what to do with [his zombies]", just because they rise from their graves, make their point, and then return to their graves. The entire point of the film is to make the viewer bear witness to the dead. Poole even says this: "The film’s theme of marital infidelity, that inescapable trope in the cinema of the Great War, became a symbol for the larger question of whether the nation had been faithful to the cause of its soldiers. The dead came back to make sure they had." What else did you want the zombies to do???

God, the whole section about Vampyr made me crazy. Poole is all, "Carl Theodore Dreyer had little connection to the war and I’m not going to show any actual evidence that the war had an impact on his work but he made Vampyr in 1932 and it’s weird and scary and full of shadows and creepy imagery, so obviously it’s about WWI." (nb not at all an actual quote.) There's just no acknowledgement that a person might make a horror film that was inspired by something that happened to them that wasn't WWI. Hell, there's no acknowledgement that a person might make a horror film because they like making spooky stuff. I was a monster kid basically from birth - I suffered no trauma to make me that way. I certainly didn't participate in WWI. Explain that, W Scott Poole.

Lastly, he's just factually wrong about The Phantom of the Opera, in that he claims that the 1925 film presents no explanation for Erik's deformity, unlike the novel. This is not correct - there is no reason for his deformity in the novel either. Later films added that. The lack of explanation in the 1925 film is not a response to mutilated war veterans; it's just an accurate adaptation. Poole says, "No one in the Western world could have looked at the visage of Lon Chaney and not thought of what the French called the gueules cassées…" and maybe that's true, but he's just stating a theory based on a mistake and presenting no evidence.

On the plus side, I'm making a very cool list of books I want to read from the works cited, and also some films that I haven't gotten around to seeing yet.

#i left out the bit where he talks for several paragraphs about the first italian horror film: 'il mostro di frankenstein'#before revealing that this is a completely lost film#to the point that what remains of it is some promotional materials a photo one still and a single contemporary review#but he's sure that it supports his thesis#and also the bit where i'm sad every day that i don't have a time machine that would allow me to attend performances at the grand guignol#sara reads an infuriating book

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

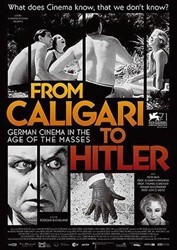

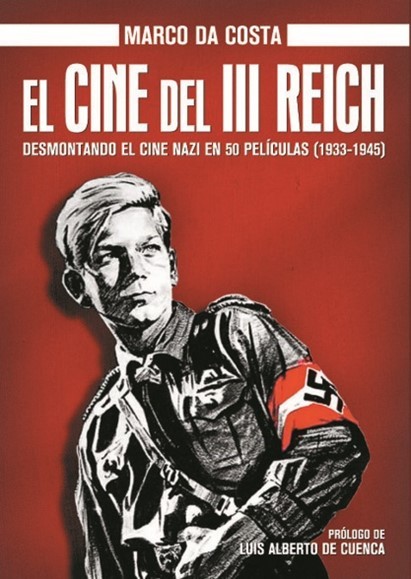

EL CINE NAZI (I): DEL EXPRESIONISMO A HITLER

EL LIBRO

EL DOCUMENTAL

MI PEQUEÑA APORTACION AL TEMA HACE MÁS DE 50 AÑOS (SIN COMPARACIÓN POSIBLE CON LOS DOS ANTERIORES)

CALIGARI

H. K. BRESLAUER

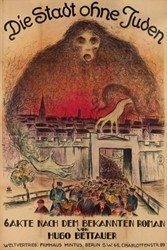

LA CIUDAD SIN JUDIOS

1933. LOS NUEVOS CINEASTAS ALEMANES

(En estos días se cumplen 90 años de la llegada de Hitler al poder en Alemania. En los próximos capítulos desgranaré la historia del cine nazi. Un cine vomitivo en la mayoría de los casos, pero no exento de calidad en algunas de sus películas.)

Si en el principio fue Francia el lugar donde se inició la cinematografía y poco después en los Estados Unidos se desarrolló la gran industria del cine, hubo otros países que aportaron movimientos y creadores que forman parte ya de la gran historia del séptimo arte. Uno de esos países fue Alemania. En el país germánico, al final de la I Guerra Mundial se inició uno de los movimientos cinematográficos que iba a marcar una época no solo en el cine de ese país sino en el de todo el mundo y que ha venido influenciando a los grandes cineastas hasta la actualidad. Ese movimiento fue conocido como el Expresionismo Alemán y directores actuales como David Lynch o Martin Scorsese reconocen inspirarse en ese movimiento para realizar su cine.

Hasta la llegada al poder de los nazis en 1933, ese movimiento aportó al cine grandes autores y grandes películas. Sin entrar en un análisis exhaustivo sobre el expresionismo es necesario señalar directores como Murnau, Ruttmann, Leni, Lang, Von Stenberg o Lubitsch y películas como El gabinete del Dr. Caligari, M el vampiro del Dusseldorf, Amanecer, Los Nibelungos, El ángel azul, Berlín sinfonía de una ciudad, El testamento del Dr. Mabuse o Metrópolis.

Sin duda fue Siegfried Kracauer en su texto de 1947 De Caligari a Hitler, el que mejor ha estudiado la evolución del cine alemán desde su nacimiento hasta la llegada de los nazis al poder. En 2014 con el mismo título y tomando como base el texto de Kracauer se realizó un documental dirigido por Rudiger Suchsland absolutamente recomendable. Otros autores como Marco da Costa han publicado y siguen publicando trabajos sobre el cine alemán especialmente sobre el cine de los años de dominio nazi; un cine ciertamente desconocido pues parte de la obra que se realizó en esos años era pura propaganda fascista y antisemita, por lo que muchas de esas películas constituyen hoy día un serio problema para acceder a ellas ya que su difusión está restringida.

Lo que ha llamado la atención a los historiadores es que en esos años de la República de Weimar se realizaron varias películas que se han catalogado como premonitorias de lo que iba a llegar a Alemania a partir de 1933. Todavía más: hay una película austriaca de 1924 que claramente muestra la persecución de los judíos. Lo llamativo de todo esto es que el partido nazi era muy minoritario durante aquellos años y que solo se fue coinvirtiendo en un partido de masas a finales de la década de los años 20 por lo que difícilmente se podía considerar un peligro en el momento de realización de algunas de estas películas.

La más conocida de todas es una película de culto del cine silente: EL GABINETE DEL DR. CALIGARI de Robert Wienne, 1920. Poco puedo aportar yo que ya no se haya escrito sobre Caligari: historiadores, sociólogos, cineastas y hasta psiquiatras han debatido y realizado múltiples estudios sobre esta película. No voy a entrar en un análisis más, que sobraría, ante todo lo que se conoce sobre la película; tan solo hay que recordar sus grandes aportaciones formales: iluminación, sombras, composición de planos, decorados inclinados, maquillaje muy acentuado, etc. Aportaciones que años después numerosos directores hicieron suyas para realizar sus películas (recordemos el cine negro norteamericano o el neorrealismo italiano sin ir más lejos). Estas aportaciones técnicas se han analizado desde puntos de vista muy profundos haciendo especialmente análisis psicológicos sobre ese “lenguaje” de sombras propias del expresionismo. Como ocurre en muchas ocasiones, a veces las cosas son más sencillas: esos decorados propios del expresionismo, con esa especial iluminación y esas sombras tan características se debían en gran parte a que… tras la guerra y durante los primeros años de Weimar las restricciones de electricidad eran muy frecuentes y los rodajes se debían limitar a una serie de horas al día a veces con escasa iluminación. Este hecho producto de las circunstancias sociales del momento se convirtió con los años en un signo de identidad de ese movimiento cinematográfico y lo desbordó hasta convertirse en una especial forma de lenguaje fílmico.

Pero si en su expresión formal Caligari aportó numerosos cambios, no fue menos lo que aportó en el aspecto conceptual con la introducción de elementos oníricos o alucinatorios lo que suponía una enorme novedad en el cine de esos años. La crítica norteamericana llegó en su mayoría a alabar la película, pero la tacharon de “siniestra y macabra”.

En síntesis, la historia de Caligari es la siguiente: a un pequeño pueblo llega el espectáculo del Dr. Caligari con un sonámbulo con capacidad para predecir el futuro. Al mismo tiempo comienzan a suceder una serie de asesinatos. La traslación política a la que aluden los expertos sobre esta película es que Caligari se corresponde con Hitler mientras que el sonámbulo es el pueblo alemán que obedeció inconscientemente a su líder supremo.

Pero otras películas ya más cercanas al cenit del partido nazi anunciaban el terror que se aproximaba: Fritz Lang como final de su trayectoria alemana realizó M el vampiro de Dusseldorf (1931) y El testamento del Dr. Mabuse (1933, inmediatamente prohibida por Goebbels). Del cine de Lang sustrajeron los alemanes elementos para la estética nazi. Según Krakauer Los Nibelungos (1924) y Metrópolis (1927) fascinaron a los nazis que tomaron de ellas elementos ornamentales para sus fastuosos desfiles.

Pero si todas estas disquisiciones sobre la premonición nazi del cine alemán no fuesen suficientes existe una película desaparecida hasta hace 7 años que, de forma clara y absoluta, sin especulaciones psicológicas de ningún tipo, anuncia el holocausto judío que iba a suceder unos años después.

En 1924 en Austria, se realiza LA CIUDAD SIN JUDIOS, dirigida por Hans Karl Breslauer. La sinopsis no puede ser más evidente: los habitantes de la República de Utopía acusan a los judíos de ser los causantes de la grave crisis económica y social que padecen y los expulsan del país, los persiguen y los maltratan. El relato final de la película es una crítica del racismo.

Breslauer (1888-1965) fue un actor, guionista y director austriaco que comenzó a trabajar en Berlín a partir de 1910 y en 1918 comenzó a dirigir. La película está inspirada en una novela satírica del escritor judío Hugo Bettauer y el rodaje se realizó cuando Hitler estaba encarcelado y escribía su Mein Kampf. Aunque básicamente el guion de la película nos traslada a un pogromo más de los que ha habido a lo largo de la historia en muchos países, lo que hace esta película singular es que los hechos suceden coetáneamente al relato y en una ciudad reconocible (Viena es Utopía).

La ciudad sin judíos aparte del interés premonitorio de la historia puede considerarse una película maldita por las consecuencias que tuvo paras sus autores:

-el autor de la novela fue asesinado por los nazis poco después del estreno.

-Breslauer, el director no volvió a dirigir y murió en la miseria en 1965.

-la coguionista Ida Jenbach fue deportada a un gueto donde murió en 1941.

-los actores principales tuvieron un recorrido diferente en sus vidas privadas: el actor que interpretaba en la película al judío se afilió después al partido nazi y fue un activo militante de las SS, mientras que al antisemita de la película se opuso al régimen en los años siguientes.

El estreno de la película en 1924 fue accidentado pues los nazis la boicotearon de forma activa atacando a los espectadores incluso. Pero lo más curioso de esta película es que unos años después de su estreno desapareció y se dio por perdida hasta que en 1991 apareció una copia incompleta en Ámsterdam y ya en 2015 apareció en un mercadillo de París la copia completa. Gracias a aportaciones particulares se recaudaron 75.000 euros para restaurarla. Hoy La ciudad sin judíos es un documento excepcional por su singularidad histórica: anuncia lo que unos años después iba a suceder en Europa.

A finales de Enero de 1933 Adolf Hitler era nombrado Canciller de Alemania. Al día siguiente con Goebbels a la cabeza se iniciaba la etapa del cine nazi.

25/2/2023

1 note

·

View note

Text

Beim Hören Assoziationen zu Krakauers Gedanken zur Dingwelt:

das Gegenständliche soll aus dem Gefängnis des Idealismus befreit, die idealistischen Bedeutungsproduktionen, die vergewaltigenden Realitätserklärungen sollen beiseitegeräumt werden, eine autonome, vom Ich unabhängige eigene Substanz der Dinge, der Oberfläche soll durch ein neues Sehen entdeckt werden.

0 notes

Text

pros of 1978 version of the pennies from heaven dance scene where arthur's application for a loan gets rejected

choice of song, choreography, and setting all work to communicate the characters' conflict and emotions

startling transition into dance makes the song feel tonally mismatched and unsettling, effective communication of the anger arthur feels but is unable to unleash on the banker—continues the series' exploration of arthur's entitlement and its themes of class and gender

pros of 1981 version

steve martin kisses a man on the lips

steve martin tap dance

they use the most embarrassing song of the tracklist for this ("my baby said yes! yes!")

synchronized dancing is an interesting nod to siegfried kracauers' theory of the mass ornament ("the mass ornament" 1927). arguably "money" here is what is being abstracted, as the concept of having the loan is stretched into this entire fantasy sequence. given the film's setting during the great depression and arthur's emasculation through his lower-class status, it makes sense that arthur would lean into what kracauer describes as the abstraction and vagueness that is perpetuated by capitalist economic systems. as kracauer writes, it seems like a "relapse into mythology" (84)—bags of money, tuxedo, large beautiful set—showing how invested arthur is in the class system/symbolic sense of money (as a way to prove himself a competent salesman) as well as how it directly affects his life.

viewing the scene as a callback to the film mass ornaments of the 20s and 30s, it's a period-appropriate way to represent arthur's emotional relationship to wealth

#im not fucking analyzing this movie correctly or incorporating theory into my argument correctly or even making an argumentative#thesis but i need to go do laundry#wise fuzz

2 notes

·

View notes