#septizonium

Text

DEMOLISHING THE SEPTIZODIUM

As Raphael’s letter to Leo X (1519) makes clear, for all its professed admiration for antiquity, the Renaissance destroyed far more than it preserved of ancient Rome.

As late as the 1580s, as substantial 3-story fragment of the Septizodium still stood at the foot of the Palatine Hill. Erected in AD 203 by Septimius Severus as decorative façade or nymphaeum masking the base of the hill below the imperial palace, the name referred to the seven solar deities honored in its seven distinct parts. The central portion of the elaborate screen-like edifice had collapsed in the mid-9th century, during an earthquake that brought down many Roman buildings. By 1500, the standing remains of the eastern end of the Septizodium were in parlous condition. Nevertheless, as numerous detailed drawings by various 16th-century artists and architects recording its plan, elevation and dimensions make clear, the Septizodium was regarded as a work of great historical and artistic importance.

During the pontificate of Sixtus V, the early modern city of Rome was carved out of the warren of surviving ancient ruins and medieval accretions. This radical reorganization, carried out by the pontiff’s chief architect, Domenico Fontana, necessitated the systematic destruction of several monuments, including the Septizodium. Fontana is remembered today for the relocation of the Vatican obelisk, a masterwork of carefully-orchestrated engineering. As Christine Pappelau has meticulously demonstrated, the destruction of an ancient monument required just as much advanced engineering and logistical foresight as the preservation of one.

Working from records in the Vatican Archive, including Fontana’s invoice with his notes explaining his intentions and the job’s projected expenses, Pappelau reveals the ins and outs of the rarely-mentioned Renaissance demolition industry. Fontana’s report lays out the order of events. The project begins with the dismantling of the superstructure. Elaborated architectural components like the columns were dislodged and lowered to the ground with winches, while materials with no reuse value like medieval bricks were unceremoniously tossed off the building. Next came the more technically-challenging excavation of the foundation’s massive blocks of travertine. Fontana also had to consider where the on the site the deposed masonry would placed without impeding the on-going works.

The determination of transportion and storage logistics required the counting and the calculation of the total volume of the reusable blocks of peperino and travertine. Fontana subcontracted the task of loading and moving the resulting 200 cartloads of stone to a company specializing in the transportation of building materials. The plotting of traffic routes was complicated by the multiple, on-going construction works. The hauling the Septizodium stone came cost 400 scudi, or 40% of the project’s total budget would of 1400 scudi.

The bulk of the spoliated building materials were used in the foundations of the obelisk raised in the Piazza del Popolo; to restore the base of the column of Marcus Aurelius; and for new construction at the monastery occupying the Baths of Diocletian.

Sources:

Samuel Ball Platner and Thomas Ashby, A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (Oxford, 1929).

Christine Pappelau, “The Dismantling of the Septizonium – a Rational, Utilitarian and Economic Process?”

78 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sandro Botticelli at the Sistine Chapel

The Sistine Chapel takes its name from Pope Sixtus IV della Rovere (pontiff from 1471 to 1484) who had the old Cappella Magna restored between 1477 and 1480. The 15th century decoration of the walls includes: the false drapes, the Stories of Moses (south and entrance walls) and of Christ (north and entrance walls) and the portraits of the Popes (north and south and entrance walls). It was executed by a team of painters made up initially of Pietro Perugino, Sandro Botticelli, Domenico Ghirlandaio and Cosimo Rosselli, assisted by their respective shops and by some closer assistants among whom Biagio di Antonio, Bartolomeo della Gatta and Luca Signorelli stand out.

Punishment of Korah, Datan and Abiron

This panel of Botticelli is the most important of the series from the point of view of symbolic content. He presented a subject iconographically very rare. In contrast to the previous ones, the episodes are set in a landscape which we could call urban, dominated by three classical buildings of which two are clearly recognizable, the Septizonium on the right and in the center the Arch of Constantine.

The action occurs in the foreground: on the right the attempt to stone Moses, in the center, at a sign from Moses, the followers of Korah who were offering incense are consumed by an invisible fire, contrasting with Aaron, a hieratic priestly figure with a tiara; to the left, again at a sign from Moses, the earth opens up to a swallow the blasphemers, while their children watch the scene in terror as if suspended on a cloud.

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

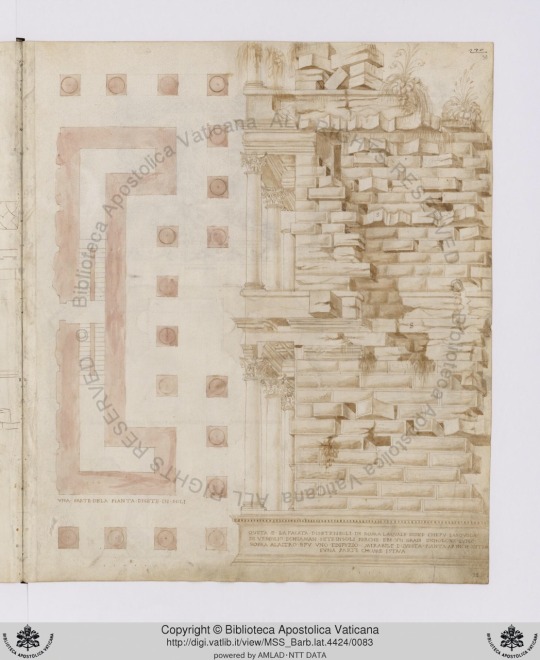

Giuliano da Sangallo’s “book of designs”, and the Septizonium I was looking through the Vatican manuscript Barberini lat. 4424, the "book of designs" by Giulano da Sangallo (d.1516), and I found what seems like an old favourite - a drawing of the Septizonium, the now vanished facade that once stood at the end of the Via Appia to hide the Palatine.

0 notes

Text

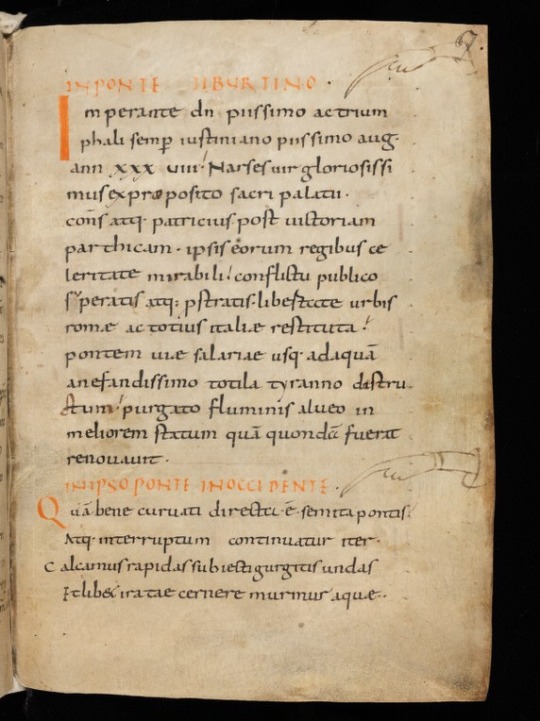

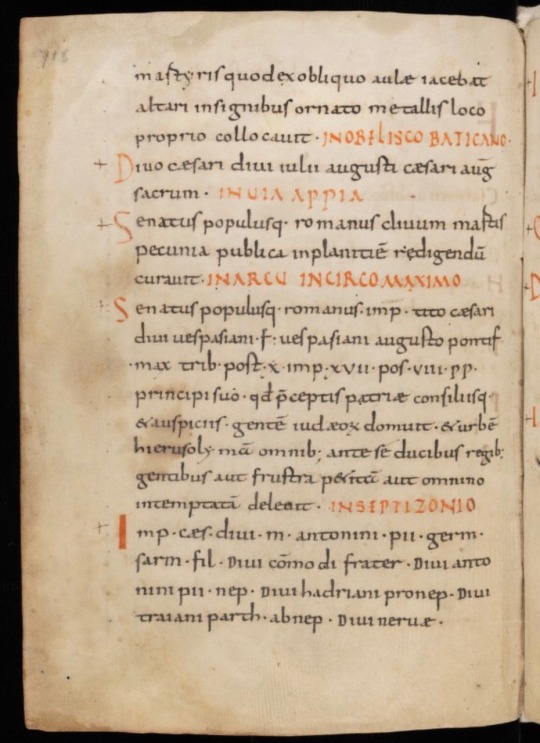

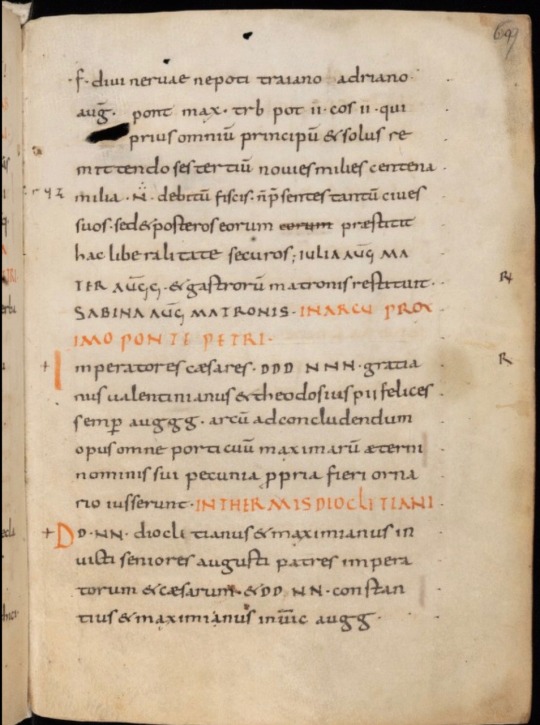

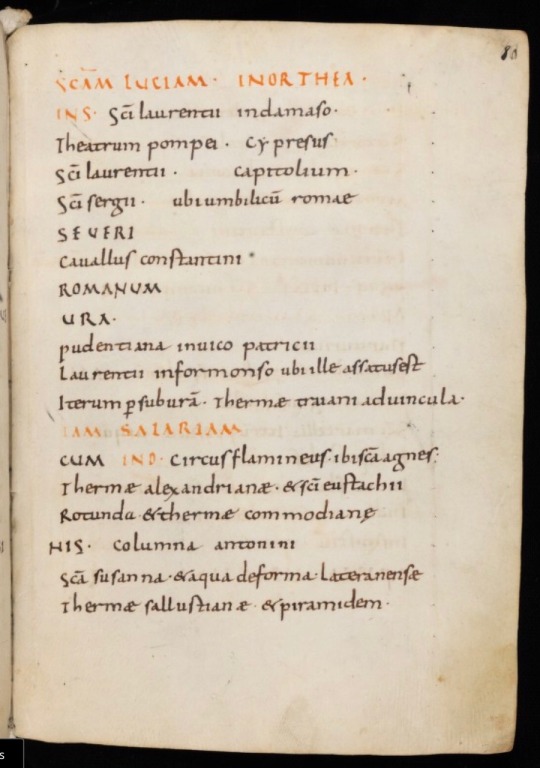

THE EINSIEDELN ITINERARY

The library of the Benedictine monastery of Einsiedeln contains a miscellany (Einsiedeln, Stiftsbibliothek Codex 326) compiled over the 9th and 10th centuries at unknown German monastery. The two most important texts, the Inscriptiones Urbis Romae and the Itinerarium Urbis Romae, were composed in Rome in the early 9th century. The author is known today as the Anonymous of Einsiedeln because the only surviving copy of his work is located in the Stiftbibliothek; the author had no connection to the Swiss monastery. The Einsiedeln texts were redacted by a northern scribe in a clearly-legible Caroline miniscule, from either a German or Italian manuscript source.

The Itinerarium (fols. 79v-89r) is a topographical guide to the principal monuments of the city. Composed for pilgrims visiting the city, the text consists of a series of walks across the city beginning and ending at different city gates. Both pagan and Christian monuments are indicated. For most monuments, the text is only list of names with no descriptions. Many of those casually mentioned names—Theatrum Pompei, Septizonium, Thermae Traiani, Capitolium—however, grip the modern reader’s attention, reminding him/her of how many major monuments of which no trace remains today, were still standing and correctly identified in the Carolingian period.

The itinareries are accompanied by the Inscriptiones Urbis Romae (67r-79v). This collection records epigraphic inscriptions seen on bridges, temples, arches, baths, basilicae, column and statue bases, and so on. As the majority of those monuments no longer survive, the Einsiedeln transcriptions are of vital importance to any understanding of ancient Roman topography, imperial patronage, and architectural and urban history. In the few cases where the source of a redaction by the Anonymous still exists, his transcritions have proved to be accurate.

Given its usefulness, the text must have been popular among foreign visitors to Rome. The Einsiedeln manuscript however, is the only known copy of the Itinerarium and Inscriptiones. Although the volume had entered the library’s collection in the 17th century, those texts were “discovered” and correctly identified only in the 19th century.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

More pictures of the Septizonium

More pictures of the Septizonium

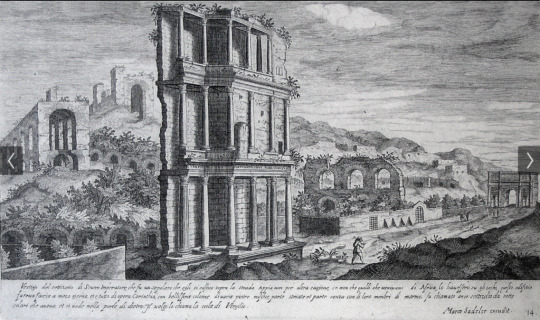

My attention was drawn to a couple more pictures of the Septizonium this week. First, drawing in B. Gamucci ‘Libri Quattro dell’ antichita della citta di Roma’ 1569: B. Gamucci ‘Libri Quattro dell’ antichita della citta di Roma’ 1569 Next, a redrawing by Dutchman Matthijs Bril, via the Louvre: original BRIL Matthijs le Jeune flamande Fonds des dessins et miniatures Interesting for showing the…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

More images of then-surviving Roman monuments from "Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae" by A. Lafrery (1593)

More images of then-surviving Roman monuments from “Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae” by A. Lafrery (1593)

Following my post yesterday, Ste Trombetti has found that the prints by Lafrerie / Lafrery are to be located in the Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae (1593). Happily this is online in high resolution, and downloadable in PDF form, at the UB in Heidelberg here (and the page shows all the pix in thumbnail too – a very well organised site).

This means that, for the first time, we can get some decent…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

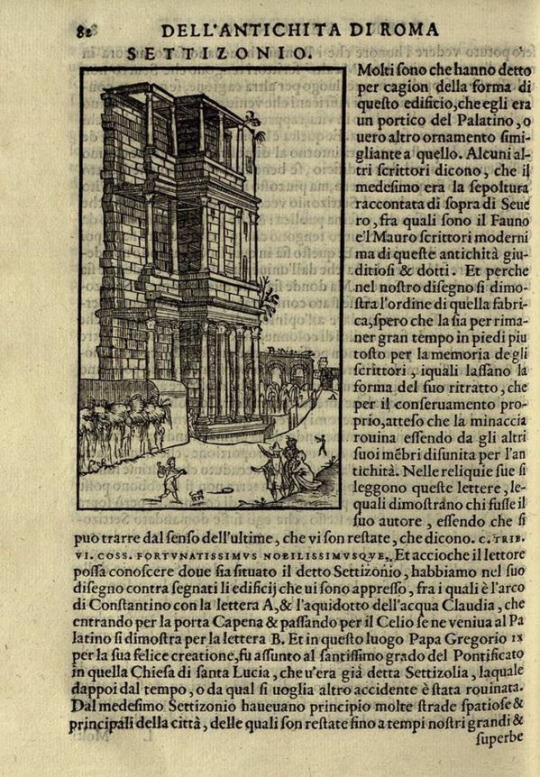

Gamucci's images of the Septizonium; the Temple of the Sun; the Arch of Claudius; and the obelisk and Vatican Rotunda

Gamucci’s images of the Septizonium; the Temple of the Sun; the Arch of Claudius; and the obelisk and Vatican Rotunda

Ste. Trombetti has continued to search through early books and prints for images of vanished Rome. Here is another example, from the 1565 work Dell’Antichita di Roma by Bernardo Gamucci.[ref]B. Gamucci, Libri quattro dell’antichità della Citta di Roma: raccolte sotto breuita da diversi antichi et moderni scrittori, Venice: G. Varisco &c, 1565. Online at Google books here, or in better quality at…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

A book describing the ceiling of the vanished Septizonium in Rome

A book describing the ceiling of the vanished Septizonium in Rome

A couple of weeks ago Ste. Trombetti posted on Twitter another couple of finds about the Septizonium. This was a facade in front of the Palatine hill in Rome, erected at the end of the Appian Way as a kind of formal entrance to the palaces, by Septimius Severus. It was pulled down in the 16th century, at which time only one end was still standing, and the materials used for various building…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Images of vanished Rome once more

Images of vanished Rome once more

Ste. Trombetti has turned his attention to the Dutch Rijksmuseum in his search for old etchings and drawings of Rome. The search for this museum is here.

The first image is of the vanished Septizonium, from 1550, a drawing by Hieronymus Cock (Antwerpen c. 1518-1570). The majority of the image consists of some unfamiliar-looking ruins on the Palatine hill – are these really in the right place?…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Images of vanished Rome : the Septizonium and the Meta Sudans

Images of vanished Rome : the Septizonium and the Meta Sudans

Ste. Trombetti has been busily searching the online site of the Spanish National Library, and posting the results on Twitter.

First of these is a view of the Septizonium, the vanished facade of the Palatine, built by Severus at the end of the Appian Way and demolished in the 16th century for materials to build New St Peter’s basilica. This shot is particularly valuable, as it is more or less…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Some early engravings of the Septizonium

Some early engravings of the Septizonium

I have blogged before about the Septizonium, a monumental facade constructed by Septimus Severus at the foot of the Palatine where it faced the end of the Appian Way. It seems to have had no function other than that of a magnificent appearance and gateway. The last remains of it were demolished to provide materials for new St. Peters.

Here are three early 17th c. engravings of the monument,…

View On WordPress

0 notes