#Septizodium

Text

DEMOLISHING THE SEPTIZODIUM

As Raphael’s letter to Leo X (1519) makes clear, for all its professed admiration for antiquity, the Renaissance destroyed far more than it preserved of ancient Rome.

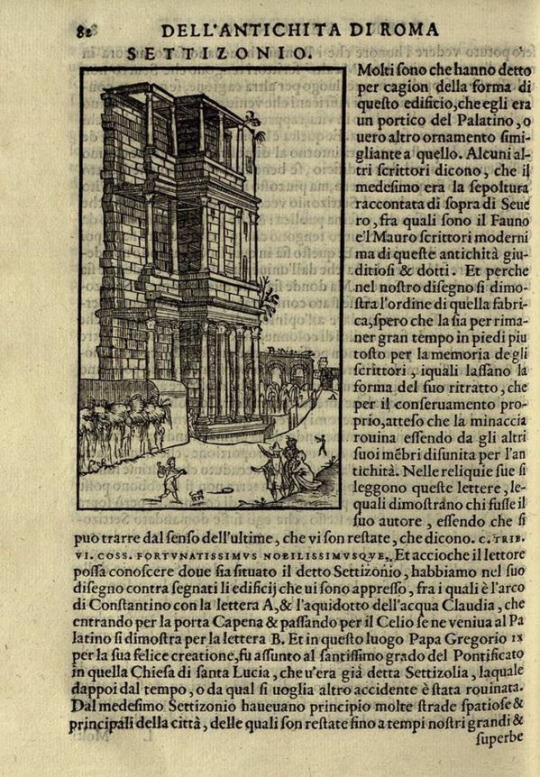

As late as the 1580s, as substantial 3-story fragment of the Septizodium still stood at the foot of the Palatine Hill. Erected in AD 203 by Septimius Severus as decorative façade or nymphaeum masking the base of the hill below the imperial palace, the name referred to the seven solar deities honored in its seven distinct parts. The central portion of the elaborate screen-like edifice had collapsed in the mid-9th century, during an earthquake that brought down many Roman buildings. By 1500, the standing remains of the eastern end of the Septizodium were in parlous condition. Nevertheless, as numerous detailed drawings by various 16th-century artists and architects recording its plan, elevation and dimensions make clear, the Septizodium was regarded as a work of great historical and artistic importance.

During the pontificate of Sixtus V, the early modern city of Rome was carved out of the warren of surviving ancient ruins and medieval accretions. This radical reorganization, carried out by the pontiff’s chief architect, Domenico Fontana, necessitated the systematic destruction of several monuments, including the Septizodium. Fontana is remembered today for the relocation of the Vatican obelisk, a masterwork of carefully-orchestrated engineering. As Christine Pappelau has meticulously demonstrated, the destruction of an ancient monument required just as much advanced engineering and logistical foresight as the preservation of one.

Working from records in the Vatican Archive, including Fontana’s invoice with his notes explaining his intentions and the job’s projected expenses, Pappelau reveals the ins and outs of the rarely-mentioned Renaissance demolition industry. Fontana’s report lays out the order of events. The project begins with the dismantling of the superstructure. Elaborated architectural components like the columns were dislodged and lowered to the ground with winches, while materials with no reuse value like medieval bricks were unceremoniously tossed off the building. Next came the more technically-challenging excavation of the foundation’s massive blocks of travertine. Fontana also had to consider where the on the site the deposed masonry would placed without impeding the on-going works.

The determination of transportion and storage logistics required the counting and the calculation of the total volume of the reusable blocks of peperino and travertine. Fontana subcontracted the task of loading and moving the resulting 200 cartloads of stone to a company specializing in the transportation of building materials. The plotting of traffic routes was complicated by the multiple, on-going construction works. The hauling the Septizodium stone came cost 400 scudi, or 40% of the project’s total budget would of 1400 scudi.

The bulk of the spoliated building materials were used in the foundations of the obelisk raised in the Piazza del Popolo; to restore the base of the column of Marcus Aurelius; and for new construction at the monastery occupying the Baths of Diocletian.

Sources:

Samuel Ball Platner and Thomas Ashby, A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (Oxford, 1929).

Christine Pappelau, “The Dismantling of the Septizonium – a Rational, Utilitarian and Economic Process?”

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

BRO i do not want to work on my site presentation

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

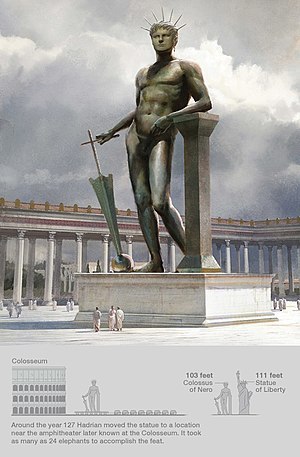

The Colosseum takes its name from the Colossus - a 30 metre bronze statue of Nero. It was still standing in the Middle Ages, and was seen as a symbol of the power of Rome: “When the Colossus falls, Rome shall fall; when Rome falls, so falls the world.”

And here's an article I wrote a while back on other amazing Roman monuments that disappeared, including the pyramid near the Vatican and the Septizodium by the Palatine Hill.

0 notes

Photo

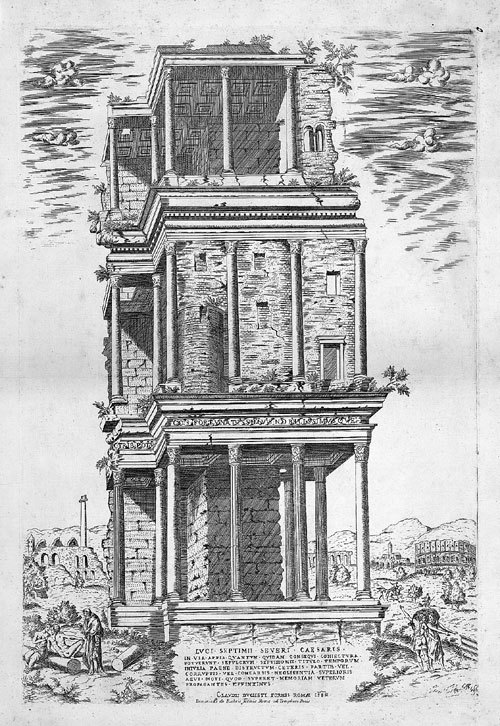

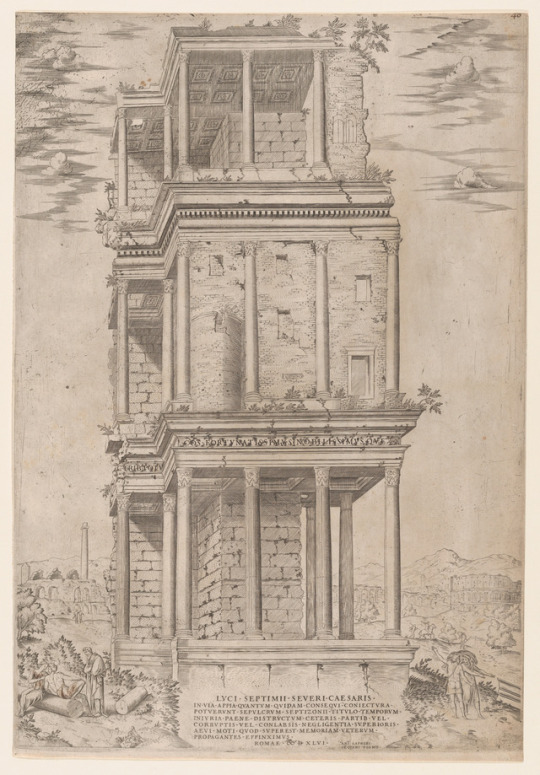

Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae: The Septizodium by Anonymous via Drawings and Prints

Medium: Etching and engraving

Rogers Fund, Transferred from the Library, 1941 Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY

http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/403247

0 notes

Photo

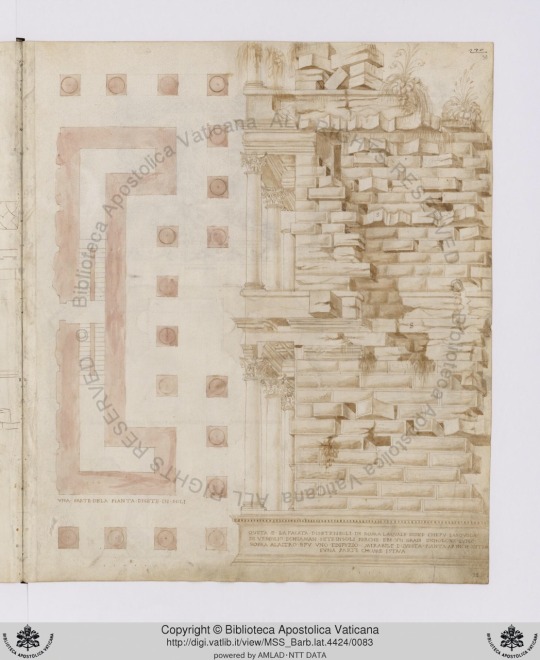

Giuliano da Sangallo’s “book of designs”, and the Septizonium I was looking through the Vatican manuscript Barberini lat. 4424, the "book of designs" by Giulano da Sangallo (d.1516), and I found what seems like an old favourite - a drawing of the Septizonium, the now vanished facade that once stood at the end of the Via Appia to hide the Palatine.

0 notes

Photo

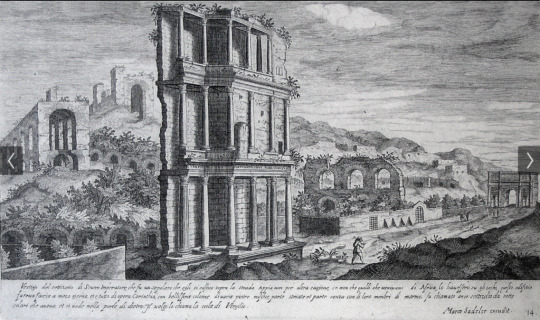

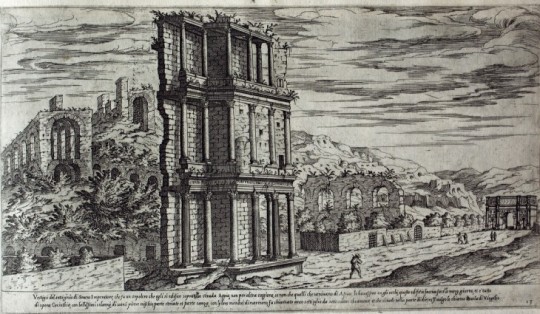

A 16th century etching depicting ruins of Septizodium that was built during the reign of Septimius severus. The edifice was demolished in 1588 by order of Pope Sixtus V.

83 notes

·

View notes