Text

THE SEVERANS AND THE CULT OF SOL INVICTUS

The Priest-King of the temple city of Emesa presided over the Syrian cult of the Sun God, El-Gabal. As seen on the reverses of these 3rd-century bronze coins, the god was worshipped in a large, lavishly-decorated temple, in the form of a large black meteorite belived to have fallen to earth from the sun.

Septimius Severus traveled to Emesa to seek the hand of the priest-king Julius Bassanius' younger daughter, the princess Julia Domna, in AD 187. The elder daughter, Julia Maesa, accompanied her sister to Rome in AD 193 following Severus' accession to the imperial throne.

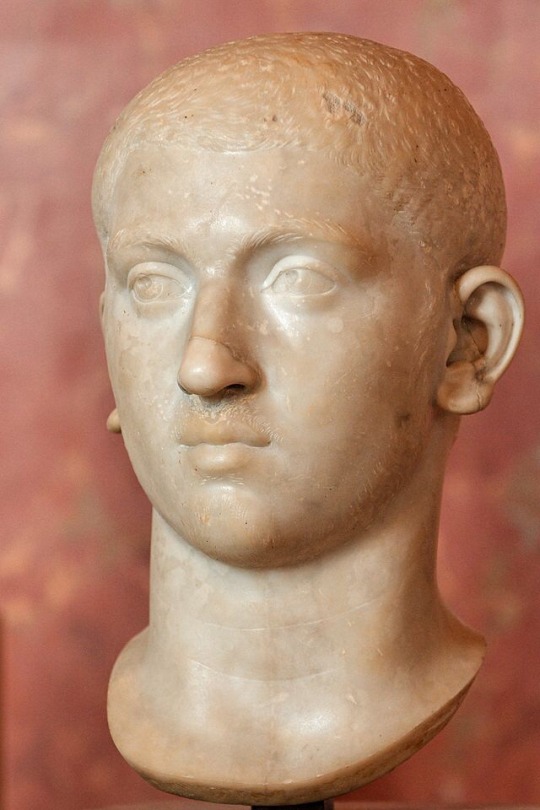

At the age of 14,:Elagabalus, the son Julia Maesa's daughter, Julia Soaemias, assumed the throne in AD 218, restoring the Severan dynasty after the assassination of Caracalla and the short reign of Macrinus. His name, Elagabalus, identified him with the Emesan sun god, who had already been accepted into the porous Roman pantheon as Sol Invictus in the Republican period.

Elagabalus' attempted to supplant Jupiter as the chief deity of Rome in favor of going so far as to having the black meteorite transported from Emesa and installed in the a dedicated temple on the Palatine Hill. Attempts to displace the three dieties Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva, worshipped in the Capitolium with the Syrian Istarte, Urania, and Elgabal profoundly alienated the Roman senate and people. The drastic religious changes proposed by Elagabalus (and not the lurid sexual slanders later included in the Historia Augusta) probably caused the Praetorian Guard to support the plot, organized by Julia Maesa, to dethrone and assassinate the emperor in AD 221. He was replaced by Alexander Severus, the son of Julia Emaea, sister of Julia Soaemias, who ruled as the last Severan emperor until AD 235.

After the fall of Elagabalus, the meteorite was returned to its temple in Emesa.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Three plates from Robert Wood's The Ruins of Palmyra, Otherwise Tedmor, in the Desart (London, 1753).

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

This late 4th-century belt comprises two gold, imperial medals, the larger of Constantius II (reigned 350-361) and the smaller of Galeria Faustina (died 140/141), wife of Antoninus Pius. Such medals were distributed to supports and friends, who often mounted them in jewelry or articles of personal adornment to proclaim their favored status. The Constantius medal, minted in Nicomedia (Asia Minor), represents on the reverse the triumphant emperor in his chariot. Other mounted medals and coins, separated by lengths of chain, would have completed the belt.

The belt is in the collection of the Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

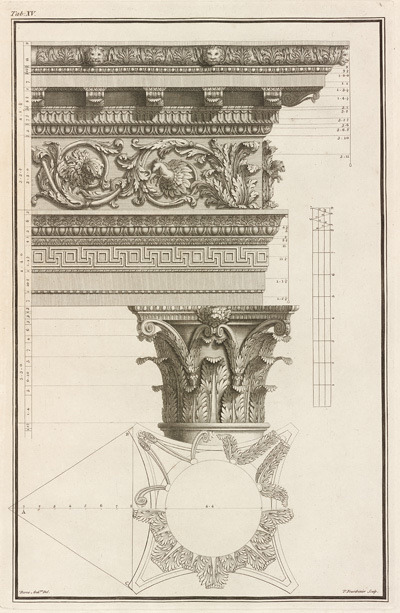

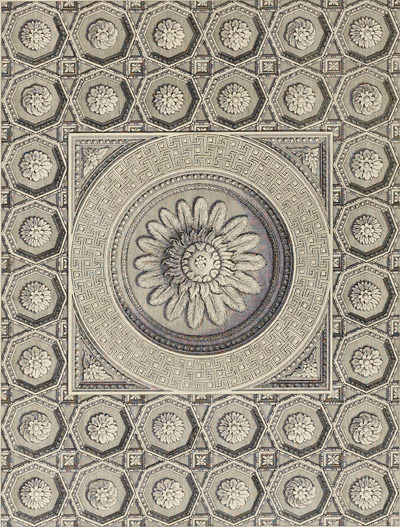

THE SEVERAN FORUM OF LEPCIS MAGNA

above: Basilica, Lepcis Magna, c. AD 209-216.

On the occasion of his state visit to his native city in AD 203, Septimius Severus granted special privileges and tax exemptions to the citizens of Lepcis Magna. In gratitude, they erected a quadrifrons arch, decorated with reliefs depicting the emperor’s military conquests. To further embellish his provincial hometown, Severus ordered the construction of a new forum, which would comprise two courtyards, a temple dedicated to the gens settimia and a basilica.

left: Lepcis Magna, Arch of Trajan, c. AD 106; right Lepcis Magna, Arch of Septimius Severus, c. AD 203.

The designs of the arch and the forum were self-conscious based on the architectural patronage of an earlier emperor, who had also favored Lepcis Magna. Trajan had raised the city to the status of a colonia shortly after AD 106, and this act was commemorated by a quadrifrons arch honoring the emperor. The Severan arch therefore replicated the distinctive form of the earlier monument, which stood nearby over the same decumanus.

Similarly, the Severan Forum was modeled on the Forum of Trajan in Rome. In the latter, the Basilica Ulpia was placed perpendicularly between to two colonnaded courtyards.

above: Forum of Trajan, Rome, c. AD 106-112

The Severan basilica (J) was originally intended to stand between two open courtyards, only one (G) of which was built. Like the Basilica Ulpia, the long hall of the Severan basilica was divided into two aisles and high taller central vessel carried by superimposed colonnades and terminated in hemispherical apses.

above: Severan Forum, Lepcis Magna, c. AD 209-216

Due to irregularities of the site, the two courtyards of the Severan forum were slightly off-axis. To create the illusions of rectilinearity and axiality, the architects placed the basilica at an oblique angle to the southern square and filled in the wedge-shaped interstice with a row of shops of diminishing sizes. This subtle device creates the visual impression of axial continuity as the viewer passed from one rectilinear space (G) to another (J).

A lengthy and largely unabbreviated inscription (typical of the verbose Severans) on the basilica’s architrave states that Septimius Severus began the building and that it was completed during the reign of Caracalla in AD 216.

Unlike the monumental, classicizing sculpture of the Forum of Trajan, the style of the lavish sculptural decoration of the Severan basilica, carried out by sculptors from Aphrodisias, derives from eastern monuments, and reflects the influence of the Syrian empress Julia Domna.

Despite that superficial difference, through the repetition of architectural forms, the architects of the Severan forum emphasized the two acts of imperial patronage that had raised the city to its position of properity and prominence in north Africa.

#septimius severus#leptis magna#tripolitania#roman architecture#imperial forum#basilica#triumphal arch

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marble reliefs from the House of the Dionysiac Reliefs (Herculaneum), 1st c. AD, Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale.

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Egyptian basalt portrait bust of Nero Julius Caesar Germanicus (15 BC - AD 19), carved c. AD 20 and defaced in the early Christian period. London, British Museum.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

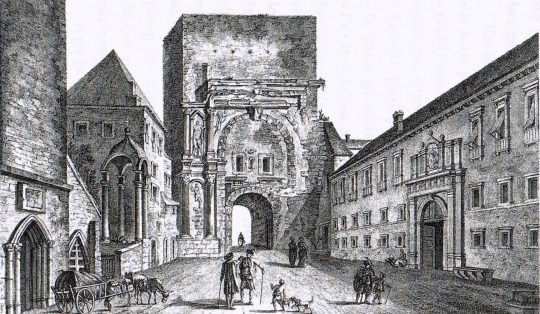

LA PORTE NOIRE in Besançon (Latin: Vesontio, later Besontio) is a triumphal arch constructed around AD 175 to commemorate the victories of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus over the Parthians in AD 164/65 and the victories of Marcus Aurelius over various Germanic tribes in AD 171/78.

Called the Arch of Mars in antiquity, the structure was originally free-standing. It was incorporated into the city walls in the Middle Ages and remained engulfed in a bastion until the mid 19th century. The arch ceased to be noire after the restoration of 2011 removed layers of dark soot and debris.

The surviving portion of the unusually rich sculptural decoration depicts the capture of Ctesiphon and scenes of mythogical battles. The reliefs on the other side, now lost, depicted barbarian conquests. The finely-grained, locally-quarried pierre de Vergenne is ideal for detailed carving, but also vulnerable to erosion.

201 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fullery of Stephanus on the Via del Abbondante, Pompeii. Paul Williams photo.

646 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE ARCH OF GERMANICUS AT SAINTES

The Arch of Germanicus was built by Caius Julius Rufus, a wealthy citizen of Mediolanum Santonum (Saintes) in AD 19. The inscription beneath the cornice states that the arch was dedicated to Germanicus, the adopted son of Tiberius:

GERMANICO [CAESA]R[I] TI(berii) AUG(usti) F(ilio)

DIVI AUG(usti) NEP(oti) DIVI IULI PRONEP(oti)

[AUGU]RI FLAM(ini) AUGUST(ali) CO(n)S(uli) II IMP(eratori) II

[To Germanicus Caesar, son of Tiberius Augustus, grandson of the deified Augustus, great-grandson of the deified Julius, augur, flamen, augustales, consul for the second time, hailed imperator for the second time.]

The arch commemorates the death of Germanicus in AD 19, but inscription’s disproportionately long reference to Tiberius indicates that the monument was tacitly addressed to the emperor.

The donor is fully identified by an inscription that carved on all four sides of the arch:

C(aius) IVLI[us] C(aii) IVLI(i) OTUANEUNI F(ilius) RVFVS C(aii) IVLI(i) GEDOMONIS NEPOS, EPOTSOVIRIDI PRON(epos)

[SACERDOS ROMAE ET AUG]USTI [AD A]RAM QU[A]E EST AD CONFLUENT[E]M, PRAEFECTUS [FAB]RUM, D(at).

[Caius Julius Rufus, son of Caius Julius Otuaneunus, grandson of Caius Julius Gedemo, great-grandson of Epotsovirid(i)us, priest of Rome and of Augustus at the altar at Confluens, prefect of works, gave this.]

The arch originally stood over the road running from Lyon to Saintes. To allow for the expansion of the river quays in 1843, it was was disassembled and relocated 15 meters closer to the entrance to the city.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

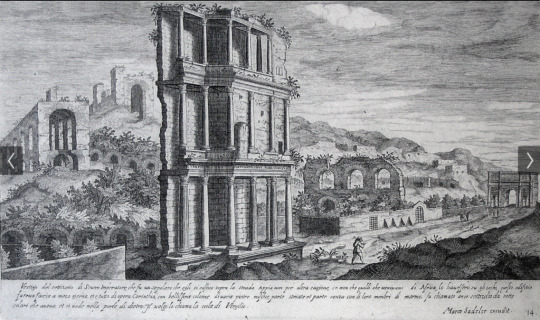

Vedute engravings of ancient monuments of Rome by Giuseppe Vasi.

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE SEVERAN DYNASTY

Julius Bassianus, Priest-King of Emesa

Julia Domna, daughter of Julius Bassianus, wife of Septimius Severus (AD 193-211), mother of Caracalla (AD 209-217) and Geta (AD 209-211);

Julia Maesa, daughter of Julius Bassianus, older sister of Julia Domna, mother of Julia Soaemias and Julia Mamaea;

Julia Soaemias, mother of Elagabalus (AD 218-222);

Julia Mamaea, mother of Alexander Severus (AD 222-235).

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

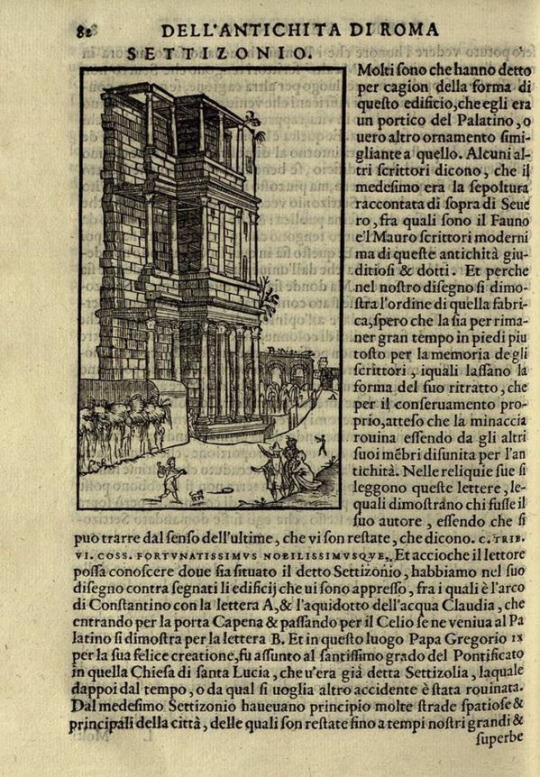

DEMOLISHING THE SEPTIZODIUM

As Raphael’s letter to Leo X (1519) makes clear, for all its professed admiration for antiquity, the Renaissance destroyed far more than it preserved of ancient Rome.

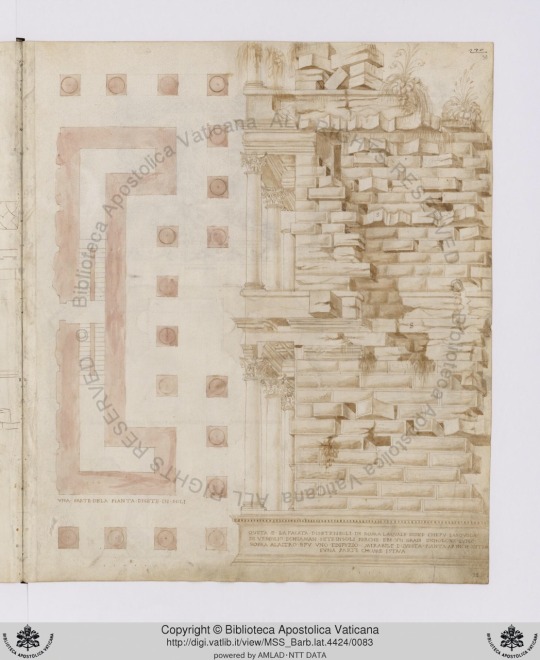

As late as the 1580s, as substantial 3-story fragment of the Septizodium still stood at the foot of the Palatine Hill. Erected in AD 203 by Septimius Severus as decorative façade or nymphaeum masking the base of the hill below the imperial palace, the name referred to the seven solar deities honored in its seven distinct parts. The central portion of the elaborate screen-like edifice had collapsed in the mid-9th century, during an earthquake that brought down many Roman buildings. By 1500, the standing remains of the eastern end of the Septizodium were in parlous condition. Nevertheless, as numerous detailed drawings by various 16th-century artists and architects recording its plan, elevation and dimensions make clear, the Septizodium was regarded as a work of great historical and artistic importance.

During the pontificate of Sixtus V, the early modern city of Rome was carved out of the warren of surviving ancient ruins and medieval accretions. This radical reorganization, carried out by the pontiff’s chief architect, Domenico Fontana, necessitated the systematic destruction of several monuments, including the Septizodium. Fontana is remembered today for the relocation of the Vatican obelisk, a masterwork of carefully-orchestrated engineering. As Christine Pappelau has meticulously demonstrated, the destruction of an ancient monument required just as much advanced engineering and logistical foresight as the preservation of one.

Working from records in the Vatican Archive, including Fontana’s invoice with his notes explaining his intentions and the job’s projected expenses, Pappelau reveals the ins and outs of the rarely-mentioned Renaissance demolition industry. Fontana’s report lays out the order of events. The project begins with the dismantling of the superstructure. Elaborated architectural components like the columns were dislodged and lowered to the ground with winches, while materials with no reuse value like medieval bricks were unceremoniously tossed off the building. Next came the more technically-challenging excavation of the foundation’s massive blocks of travertine. Fontana also had to consider where the on the site the deposed masonry would placed without impeding the on-going works.

The determination of transportion and storage logistics required the counting and the calculation of the total volume of the reusable blocks of peperino and travertine. Fontana subcontracted the task of loading and moving the resulting 200 cartloads of stone to a company specializing in the transportation of building materials. The plotting of traffic routes was complicated by the multiple, on-going construction works. The hauling the Septizodium stone came cost 400 scudi, or 40% of the project’s total budget would of 1400 scudi.

The bulk of the spoliated building materials were used in the foundations of the obelisk raised in the Piazza del Popolo; to restore the base of the column of Marcus Aurelius; and for new construction at the monastery occupying the Baths of Diocletian.

Sources:

Samuel Ball Platner and Thomas Ashby, A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (Oxford, 1929).

Christine Pappelau, “The Dismantling of the Septizonium – a Rational, Utilitarian and Economic Process?”

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aureus of Antoninus Pius, struck at the mint in Rome, with the Deified Faustina (d. AD 140) on the obverse and the Temple of the Deified Faustina on the reverse. Yale University Art Gallery.

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE FARNESE BULL

Pliny the Elder mentions a sculpture in the collection Asinius Pollio depicting the Supplice of Dirce:

Asinius Pollio, a man of a warm and ardent temperament, was determined that the buildings which he erected as memorials of himself should be made as attractive as possible; for here we see ... Zethus and Amphion, with Dirce, the Bull, and the halter, all sculptured from a single block of marble, the work of Apollonius and Tauriscus, and brought to Rome from Rhodes. (Historia Naturalis 36.4)

This outsized Hellenistic sculpture, carved from a single block of marble, was displayed near the Forum in the Atrium Libertatis. In 39 BC, Pollio had funded the rebuilding of this structure, which housed the censor’s archive and the brass tablets of the ager publicus. Also included were an art gallery and Greek and Latin libraries, which Pollio founded in 39 BC. This lavish complex was demolished during the construction of the Forum of Trajan.

In 1546, excavators hired by Paul III working in the palestra of the Baths of Caracalla discovered numerous “beautiful fragments of statues and animals were found that were all in one piece in antiquity,” as a contemporary phrased it. These fragments were immediately identified as the Hellenistic group described by Pliny. This identification was supported by the fact that the baths had been built on the site of the Horti Asiniani, the gardens of Pollio’s estate, to where the sculpture might have been relocated after the closing of the Atrium Libertatis. The sculpture was reconstructed and restored by Michelangelo and installed in the Palazzo Farnese.

It is now, however, thought that the Farnese Bull is a late 2nd-century copy of Pollio’s sculpture. If that is the case, the original was either already lost or at some other location. The decision to place this work in a bathing complex contrasts sharply with the context of Pollio’s version. Situated in the Atrium Libertatis, the sculpture was prized by its owner and his cultured peers for its Greek pedigree, technical virtuosity and mythological drama. The Severans, however, may have chosen it for its size. Rising 4 m from the floor on a 3.3” x 3.3” m base, the Farnese Bull (unlike the other sculptures decorating the main bathing block) held its own amidst the gargantuan architecture. Besides the work’s scale, its violent subject matter and turbulent composition might have appealed to Caracalla’s brutish tastes and personality.

#toro farnese#gaius asinius pollio#baths of caracalla#pliny the elder#roman sculpture#hellenistic sculpture#dirce

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE TEMPLE OF HADRIAN AT EPHESUS

As an inscription on the archivolt states, the asiarch of Ephesus, Poplius Vedius Antoninus Sabinus, dedicated the small temple in the center of the city to Artemis Ephesia, the reigning Emperor Hadrian and to the demos of Ephesus.

The temple was originally built to commemorate Hadrian’s first visit to Ephesus in AD 124. The temple’s dedication to the living emperor is therefore purely honorific, recognizing his benefactions to the city, and does not reflect the establishment of an imperial cult (the ruins of a much larger structure discovered in Ephesus in the 1980s are probably the official temple of the deified Hadrian).

As seen. today, the temple consists mainly of the portico which was excavated and reconstructed in the 1950s. The profusely-decorated broken pediment and arcuated lintel are hallmarks of the baroque taste of the eastern provinces.

The structure was severely damaged by an earthquake in AD 262. Its rebuilding was completed during the early years of the tetrarchy, as evidenced by the four plinths placed in front ot the pronaos which bear the names of Diocletian, Maxentius, Constantine Chlorus and Galerius. The four marble reliefs, depicting the founding of Ephesus were removed from another monument and reused in the portico as part of a rebuilding campaign following yet another earthquake in the 370s.

The temple underwent a complete restoration in 2012/14.

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

First-century AD Roman bridge, spanning the Ofanto River, near Canosa di Puglia.

143 notes

·

View notes