#senegalese architecture

Photo

The #MissiriMosque is a former #French military community center inspired by sub-Saharan #Islamic #architecture. It was constructed in 1928–1930 for the #Senegalese Tirailleurs based in military camps in #Fréjus, #cotedazur southern #France. (hier: Mosquée Missiri) https://www.instagram.com/p/Ch8-EfHMrR2/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

1 note

·

View note

Text

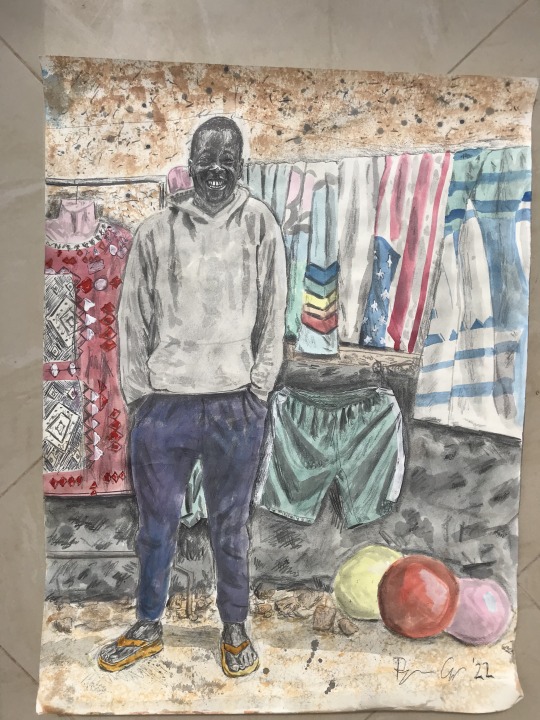

Rubell Museum - DC - Jan 13 2024

A trip to the Rubell Museum was something to look forward to despite my new Doc Martens slicing up my ankles during my 10-minute walk from the Waterfront Metro station. Opened on Oct 29th, 2022, the DC location at 65 I St. SW brought Mera and Don Rubell's collection of post-1980 art from Miami to the DC's Southwest neighborhood. This would be my second time visiting with my first experience viewing the inaugural exhibition What's Going On?. The collection showcased many artists I was not familiar with. It was a treat discovering new and exciting art. For me, artists that I wanted to learn more about from my last visit were Chase Hall, Hernan Bas and Christina Quarles.

Christina Quarles

Detail: Fell to Earth (Felt to Pieces), 2018

Acrylic on Canvas

Taking advantage of the gorgeous and expansive space past the entrance, the museum mounted works by Alexandre Diop - a Franco-Senegalese artist who, according to the website, "uses discarded objects to create work that raises questions pertaining to sociopolitical, cultural and gender issues. Drawing inspiration from his European and African roots, he explores the legacies of colonialism and diaspora while tackling universal themes of ancestry, suffering, and historical violence". The open space with its large cathedral-esque windows floods the space with natural light, showcasing all the wonderful varied textures and highlighting all the materials that Diop uses in his work.

Once you exit this room, you will enter a three-level building that was once part of Randall Junior High School, a historically Black public school that ceased operations in 1978. The Rubells purchased this historic site from the Corcoran College of Art and Design in 2010 for $6.5 million. The building was the site for the inaugural What's Going On? when the museum opened in 2022.

Although quite disorienting to navigate at first, each level essentially follows a radial floor plan. There will be an exhibit in the middle of the level when you first come, and then out in all directions are hallways that will lead to individual rooms with their own exhibits relating to the overall current exhibition - Singular Views: 25 Artists.

One of the biggest flaws in the architecture of the building or more importantly, how the architecture is utilized, is the decision to install art in the narrow hallways. These hallways doubtfully will pass the modern fire and safety code. Large enough to fit one individual through, there would often be two-dimensional works hanging on both sides of the wall. The proximity between the visitors and the works would make any conservator nervous. There is a serious bottleneck where a visitor must wait for another to pass through before entering these spaces. Needless to say, when there is a person waiting, one cannot help but exit in a hurried manner. This takes away any chance for close looking or truly connecting and appreciating the work.

Overall, the exhibition was something you would come to expect of the Rubell Museum (so far that I have seen in DC): colorful, vibrant, electric and featuring young artists, some in their early or mid careers. The standouts this time for me were Amoako Boafo, Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe and Rozeal, whom I will be covering in separate posts so they each have their own spotlights.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Facts About Senegal That makes It Special🇸🇳🇸🇳

1. Senegal is a country in West Africa known for it's vibrant culture with over 20 ethnic groups.

2. The capital of Senegal is Dakar, which is the political and economic capital of Senegal and holds over 30 percent of Senegal's total population.

3. Senegal has a Pink Lake.The lake contains high concentrations of salt and bacteria that can only survive under a particular condition and gives off a pink colour when absorbing sunlight, the uniqueness of the Pink Lake has attracted a lot of Tourists to the country.

4. Senegal boasts of beautiful colonial architecture, secluded beaches blessed with world famous surf breaks,and wildlife.

5. Senegal's biggest export are peanuts and fish.

6. In 2026, Senegal will be the first African country to host the Olympics.

7. One of Africa's most famous dish jollof rice originated from the Wolof tribe of Senegal during the 14th-16th century.

8. The Senegalese flag has green,yellow and red vertical stripes with a central green star. These are Pan-African colours with green(along with the stars)representing hope and the country's major religion(Islam),yellow representing the riches and wealth obtained through labour and red representing the struggle for Independence, Life and Socialism.

Guys let's get our YouTube channel (YT: Historical Africa) to 70k subscribers. Kindly click on the link to subscribe. 🙏 https://youtube.com/c/HistoricalAfrica

4 notes

·

View notes

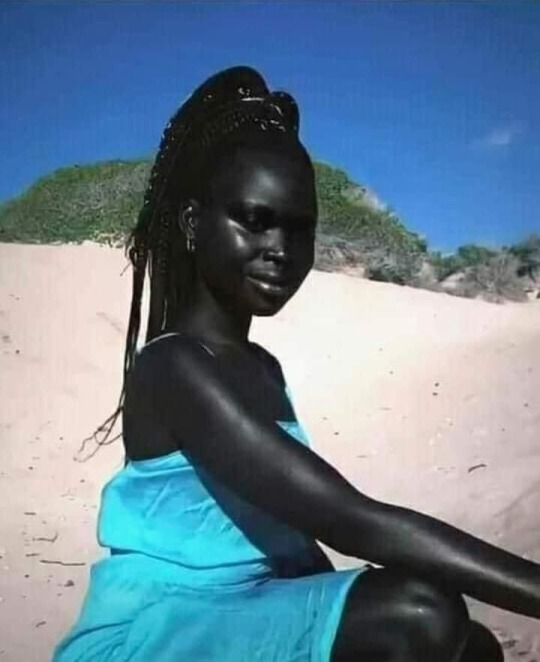

Photo

The Cast of Characters

“The soul of a country lives in any one block” -Peter Hessler

The people make the place, and that’s especially true in Dakar. Besides the painted pirogues in Lebou villages, the bustling downtown markets and -gulp- the remaining French colonial architecture, Dakar is not a very Instagram ready city. “Lots to do, nothing to see,” is how someone described it to me. It’s a magical and compelling place because of the density and full commitment of it’s inhabitants to living their lives out in public space, and often together. Men work out in the dozens on the beach in muscled groups, women stride together in neon tailored dresses down the street, the nightclubs are filled with coordinated Afro-beat dancers, kids run squealing in neighborhood bunches down the alley, the fisherman grunt and haul their vessels together out to see, vendors cluster together with hair products and mangoes and dried fish. It was so overwhelming, at first, that it took a minute to separate out faces and stories from the crowd. Some of my first attempts at friendship didn’t quite take, as happens in anyplace.

Here are snapshots of some of my favorite Senegalese and West African friends I spent time with this year:

-Ibraham: Guinean musician with a spider tattoo on his shoulder (he told me the spider protected the prophet Muhammed by weaving a web across the entrance to a cave where he was hiding, leading his pursuers to think it was abandoned.) I met him trying to haul heavy new flower pots up my stairs, when he stopped to lend a hand. He’d lived in Dakar for about 8 years, came looking for work and learned Wolof from kids here, though he spoke a half dozen other languages besides. He was an incredible musician, especially percussion, with a whole stable of guinean songs he could lead solo or sing as part of a group. I eventually started taking drumming lessons with him in the spring. He was constantly meeting new arrivals -especially from Guinea- and taking them under his wing, as well as striking up conversations with friendly foreigners. People were drawn to him, I could see. It was also a tough year for him, precarious housing and economic situation. COVID hit everywhere hard, especially creative industries that depended on live performance, and Senegal was no exception. He battled some dark days, alternating between seeking work in low-skill labor fields and holding out for musical gigs that never materialized. There was always his family home in Guinea to go back to, and at the end of my time he was ready to head home and recharge if things didn’t improve in a few months.

-Abdalla: I drew a portrait of Abdalla for his mom, and I needed to erase the mouth twice to make the smile bigger each time. That should tell you most of what you need to know. I had trouble connecting with a lot of the Baye Fall besides occasional greetings, but Abdalla was a local boy who seemed to dip his toe in just enough to scoop out reggae music and an extra dose of peace and love. The songs he composed himself are some of my favorite pieces of music from Senegal, and I hope he has the chance sometime to sing them in front of the huge crowd he deserves. His mom -Madame Faye- was not only acknowledged as making some of the best thieb in the village, but gave some of the best life advice around- I spent a good few days in her kitchen, where we’d berate Abdalla together for not helping with the cooking and he’d laugh his big laugh and play us another song. He was trying to organize a local music festival through the town, and waiting for enough funding to record an album. I worried about how trusting he was, sometimes; he always took people at face value. In the winter he let a new arrival looking for work sleep in his bed, and the man took off at 4 AM with his recording instrument, phone and guitar. The village seemed to take care of it’s own, though, the tough fisherman always jostling him affectionately when we walked around. He led a lot of our song circles, parceling out melodies and crooning high notes. During one golden afternoon I walked out to the beach and swam to Ngor Island, to find Abdalla on my favorite hidden beach with a few friends. They had guitars, flutes, drums. We sang together, and then when the sunset came we hugged and I swam home.

-Nalla: Friends who work towards goals are high on my list, whatever those goals. I few years ago Nalla was a pastry chef, when he decided he wanted to pursue art. He spent most of his time on the island, helpings uncle fix up a giant dilapidated house they were going to one day turn into a hotel/restaurant. There he holed up with paints and scraps of wood and canvasses and worked on his technique all year. Soft-spoken, blue-black skin, the chiseled Lebou cheekbones. He was one of the most constant presences at the Tuesday art nights, and I saw his technique improve dramatically while we were there. At the end of the year, he had a piece entered into the Dakar Biennial, and I felt like a proud cousin. He was an Ngorois through and through, with his dad a fisherman and dad an underwater welder. It was astonishing how may people he said hi to, both in the village and on the island. Sometimes we’d take out kayaks from the house, paddling out the the surf wave and daring each other to take bigger rides in the hard top. Even in the water, he knew every fishing boat and solitary figure that slippered along with a spear gun. He was focussed on bettering his art with a laser focus, to the exclusion of looking for a romantic partner, trying to stay on the island so he wouldn’t get distracted.

Julie: My Congolese friend, with a big smile and a weakness for sappy French love songs. She’d lived here for a few years, but been in a toxic relationship that she’d just escaped a few months before we met, with a jealous partner who didn’t want her to leave the house much. She talked about her mom often, a professional chef who cooked for airline pilots at the flight lounge. (Incidentally, her chicken recipe is one of my most treasured phone notes from my time there) When we met she was managing a clothing boutique, and sparring with an owner who seemed both not to trust her enough and to ask for too much commitment. It was fun to be around her; she had she energy of just having moved to the city and wanting to try everything. Carolyn took her along on several dance nights, and I think she might be hooked. Notably, she has an identical twin named Juliet, and two gorgeous twins with almost the same name caused a stir whenever I saw the two of them out together.

In some ways she seemed to be adapting to life in Senegal, and others still seemed to grate. Taxi drivers going for the financial jugular in proposing fares never stopped annoying her. I’d long since resigned myself to giving the many kids asking for money a sympathetic smile and walking on, but it made her angry to see every time. “What parent would let their child out to do this??” She’d always ask. We were both trying to make friends and community in the new city, and reconcile it’s patterns with what we were familiar with. It was so nice to have a partner in that.

Petit: I first saw Petit marching around at midnight acting like a tree come to life. He was acting out a scene on the dance floor with his friend Tafa. The two of them remain some of the most creative individuals I’ve come across in any country. Like athletes slumped over chairs except for the big game, they had the ability to hide in a crowd, or to dazzle. Petit was often out of town, down performing or taking workshops down the coast in Toubab Diallo, but when he was around I loved getting together to dance or just play with movement. He had recently taken a puppet making course as well as a mask-styling workshop, and also worked as an acting teacher for a local school.

He grew up in the southern region of Casamance, and talked about it always with deep, abiding love. I have no doubt when I go back he will be living there. His projects dealt often with the relationship between the self and the whole, or past traumas unearthed and confronted. One night he extemporized over Ibrahim’s drum beat, a monologue on the contentment we feel or don’t when alone. The last week before I left he was preparing a dance to welcome a group of black Americans, part of a program called Back to the Source. They were traveling to the famous Door of No Return on Goree Island, where slaves where loaded onto ships. After, they'd come to Ngor, where Petit and his crew were constructing a beautiful wooden door, through which they'd dance their American cousins as a blazing contrast to the door on Goree they’d just “closed.” Having such bright creative energy was a blessing and a half this year.

-Cheikh: ran a clothing boutique near the beach. He invested a lot in upgrading the space while I was there, until it became the hang-out spot for his group of friends. Twenty years ago he started out just selling clothes from a bag on this beach, and it was cool to see him now with a fancy shop. He started selling ice cream near the end, which I thought was a smart business move. I set him up with a Tinder account and we talked about love and dating a lot. His friend Moustafa always had a good sense of the political goings on of the neighborhood, and I lived leaning against the clothing racks, picking their brain and occasionally helping them sell things to tourists or lay out new merchandise.

-Amadou: Worked at a French-Senegalese organization around the corner, a center for unhoused kids, often running away from Quranic schools or home. Amadou ran soccer programs for them, helped with the lunch programs and literacy courses. He was a formidable soccer player himself, chiseled straight out of a men's health magazine. I couldn't believe he was still single. It was a treat watching the African Cup with him, such intense concentration and joy.

And many, many others of course, too many to fit here, everyone on their path, with lovely traits and foibles and disappointments and dreams little and big.

My European and American friends are dear as well, and just because I don’t spin out their stories here doesn’t mean they didn’t make this year so very special. Ben, Nick, Emily, Sait, Anne, Sara, Liz, Jake, if you’re reading this, sending you a big hug.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Monument to the Battle of Oum Tounsi in Mauritania

The earliest documented contact between Mauritanian and European merchants dates back to 1442, but sporadic trading certainly predates the 15th century. The year 1442 marks the moment when the Portuguese established the first permanent presence in the territory that later became Mauritania. Although this establishment had more to do with trade than with political control, its ramifications run through the rest of Mauritanian history. Between the 15th and 19th centuries, the Spanish, Dutch, and British also established some form of trading posts in Mauritania, but it was the French that eventually claimed sovereignty over this land. In 1840, after years of trade and political alliances, France issued a decree that claimed possession of Senegal. Most of the territory identified as Senegal, however, was located in modern-day Mauritania. The part of modern-day Mauritania that France was not able to claim was the inland regions of the country. These regions were barren and plagued by the harshest weather conditions imaginable. Inevitably, only the sturdiest and most resilient people called this land home. Among these were the emirates of Trarza and Brakna united against their common enemy: France. After years of local skirmishes and full-fledged battles, the parties finally signed a treaty in which the two emirates became French protectorates. This situation persisted up to the beginning of the 20th century, when France declared ownership over all Mauritania, now considered a political entity separate from Senegal. In spite of efforts to pacify the inland regions, animosity persisted against the French. Among the episodes that punctuated this volatile situation, the Battle of Oum Tounsi (aka Umm-Tunisi) stands out. It was the year 1932, and Lieutenant Patrick de Mac Mahon was the head of a French contingent made up of French, Senegalese, and Mauritanian soldiers. Mounted on camels, they were coming from Samara, about 1,500 kilometers to the north. To travel across the desert for so long, the contingent had to do as ancient merchants did, and rely on natural springs and wells. One of these wells was in Oum Tounsi, a nondescript location about 80 kilometers north of Nouakchott. It was in Oum Tounsi that the contingent was ambushed by 120 Oulad Delim men armed with French and Spanish rifles. The battle was fierce and by the end, the land was strewn with corpses. Thirty-seven men from the French contingent died, including Lieutenant Mac Mahon. The Oulad Delim forces also lost 25 men, but managed to capture the weapons and camels from the French. Subsequently, the French authorities decided to erect a mausoleum to honor Lieutenant Mac Mahon. However, what was meant to immortalize the valor of the French colonizers, was quickly reclaimed to stand as a symbol of Mauritanian resistance against the French colonizers. Reflecting this, today the mausoleum is better known as the Monument to the Battle of Oum Tounsi. The design of this relatively small structure (about four meters tall) is dominated by Arabic architectural elements, perhaps to acknowledge the number of local soldiers that lost their lives here. If there were inscriptions on the stones at the center, they are no longer discernible due to unsightly graffiti and overexposure to the elements. Not far from the monument is the well that Lieutenant Mac Mahon and his contingent probably used on the fatal day.

https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/monument-to-the-battle-of-oum-tounsi

0 notes

Link

A Senegalese architecture firm is championing a lower-tech material than concrete to help cities prepare for climate change.

0 notes

Text

To Prepare for Climate Change, Build With Mud

A Senegalese architecture firm is championing a lower-tech material than concrete to help cities prepare for climate change.

Source: To Prepare for Climate Change, Build With Mud – The Atlantic

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Architects Design a Senegalese Hotel Resort Built Around the Local Baobab Trees

A proposal for a hotel resort in Dakar, Senegal, is taking inspiration from the local culture to elegantly integrate with the surrounding landscape of massive baobab trees. Called La Reserve, the design was created by architecture firm SAOTA and has just been named a finalist in the World Architecture Festival (WAF) 2021.

The hotel is designed to seamlessly blend into the surrounding landscape instead of trying to compete with the natural beauty of the area. Because of this, the architects designed a collection of smaller buildings that are organized in waves between the baobab trees. The largest of the trees can be found at the center of the hotel; it's a decision made to honor the custom of Senegalese people, where the biggest nearby baobab tree in a community becomes a place for gathering.

#hotel resort#hotel#building#resort#architects#soata architecture firm#architecture#senegal#dakar#baobab trees#la reserve

0 notes

Text

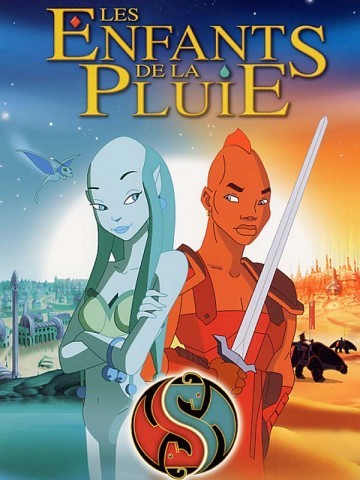

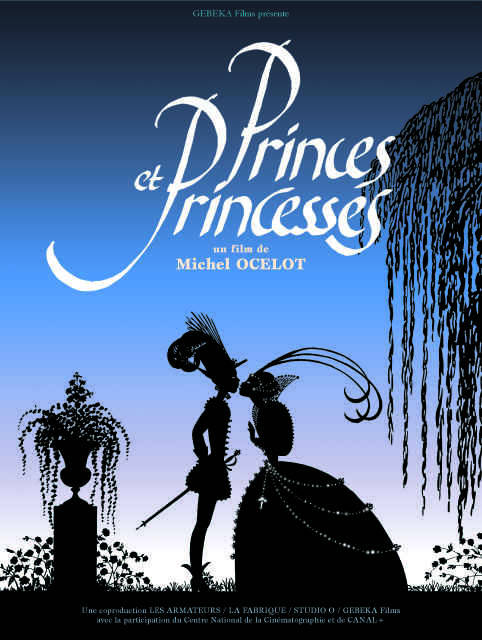

The 2000s were the golden age of French fantasy/fairytale animated films (think Prince of Egypt on a lower budget) and people are sitting on it and lamenting that Disney and Amazon can't do diversity well. (No shit). Spoilers in the links.

Kirikou et la Sorcière (Kirikou and the Sorceress), 1998 + its two sequels: inspired by West African storytelling and folktales, Kirikou is a young boy who can walk and talk since the womb and helps his people defeat the evil witch who has taken away all the men of the village. The sequels are more episodic tales focused on smaller issues Kirikou helps resolve with his ingenuity. It's got some banging songs by Senegalese star Youssou N'Dour, an almost exclusively pan-African voice cast (in the original French dub at least), and it explores some pretty dark issues without pulling any punches while managing to stay light-hearted. (It also has a lot of non-sexual nudity, which might be disconcerting if you're not expecting it.)

La Reine Soleil (The Sun Queen), 2007: essentially a Prince of Egypt rip-off but focused on Egyptian history and religion instead. It follows Ahkenaten and Nefertiti's daughter Ahkesa and her betrothed Prince Tuthankaten. The animation's not the greatest but it has some pretty impressive visuals here and there (although for the life of me I can't figure out why the royals have got otherworldly blue eyes). It's not as great as the others on the list but it's got the right vibes.

Azur et Asmar (Azur and Asmar: The Princes' Quest), 2006: by the same director as Kirikou. Azur is a rich young boy raised by an Arab nursemaid together with her young son Asmar. The three of them are separated, but an adult Azur eventually crosses the sea on a quest to find the Djinn fairy, and the two not-quite-brothers find themselves at odds. The early 3D animation is pretty funky but the backgrounds and the Morrocan architecture especially can be incredibly beautiful and detailed, and a lot of the movie is in classical Arabic (spoken by native speakers).

Les Enfants de la Pluie (The Rain Children), 2003: some very beautifully animated heroic fantasy with very nice worldbuilding and lore. It's not directly inspired by any one culture or fairytale but it's pretty far from the standard European fantasy worldbuilding that's been done to death. All the characters are non-human, with some big Atlantis vibes for the Hydross and a cool desert aesthetic for the Pyross. Sweet and short.

Princes et Princesses (Princes and Princesses), 1989, compiled in 2000: also by the guy who made Kirikou and Azur and Asmar. It's six short tales in handcrafted paper silhouette animation (inspired by Chinese-shadow puppetry), with three European-style fairy tales with some pretty imaginative visuals, and other tales from Japan, Egypt and even a sci-fi story 'from the year 3000'. As many female characters as male ones, and the female characters are all pretty awesome. The music can get hauntingly beautiful.

If you can get your hands on these, I definitely recommend giving them all a try!

#kirikou#kirikou et la sorcière#kirikou and the sorceress#michel ocelot#youssou ndour#princes et princesses#princes and princesses#azur and asmar#the princes' quest#azur et asmar#french animation#french culture#diversity#the sun queen#the rain children#ancient egypt#african culture#arab culture

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

This family home and office on the banks of Lake #Geneva, with architecture by SAOTA and interiors by ARRCC, was designed for a successful Senegalese businessman based in #Switzerland. The home draws on the owner’s heritage to advance an emerging African‐inspired aesthetic in its sculptural form, materiality, and textural quality. Read more: Link in bio! Project name: Lake House Architecture firm: @_saota Interior design: ARRCC, Mark Rielly Location: Lake Geneva, Switzerland Completion year: 2010 Project team: Stefan Antoni, Greg Truen & Juliette Kavishe Architects of Record: SRA Kössler & Morel Architects Site area: 1666 m² Project area: 1553 m² Photography: Adam Letch, Stefan Antoni #awesome #архитектура www.amazingarchitecture.com ✔ A collection of the best contemporary architecture to inspire you. #design #architecture #picoftheday #amazingarchitecture #style #nofilter #architect #arquitectura #luxury #realestate #life #cute #architettura #interiordesign #photooftheday #love #travel #instagood #fashion #beautiful #archilovers #architecturephotography #home #house #amazing #معماری (Lake Geneva, Switzerland) https://www.instagram.com/p/B-vrkD7lu56/?igshid=1i2purmvysiu7

#geneva#switzerland#awesome#архитектура#design#architecture#picoftheday#amazingarchitecture#style#nofilter#architect#arquitectura#luxury#realestate#life#cute#architettura#interiordesign#photooftheday#love#travel#instagood#fashion#beautiful#archilovers#architecturephotography#home#house#amazing#معماری

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

This family home and office on the banks of Lake Geneva, with architecture by SAOTA and interiors by ARRCC, was designed for a successful Senegalese businessman based in Switzerland. The home draws on the owner’s heritage to advance an emerging African‐inspired aesthetic in its sculptural form, materiality, and textural quality. Photography by Adam Letch, Stefan Antoni.

.

The triangular shape of the dramatically located lakeside site, in addition to strict planning parameters and prohibitions, imposed considerable restrictions on the design. The response was to carve architectural forms from the triangular footprint of the site and to create a ‘reductive’ sculptural design of round‐edged cubes and triangular masses.

For ARRCC Director Mark Rielly, this bold approach to form directly influenced his approach to the interiors. Working closely with the homeowners, Mark sourced from a wide range of South African and international décor and furniture brands. “The contemporary architectural space defined the design direction, resulting in a modern approach with brands of diverse origin chosen for the décor,” says Rielly.

Internally, finishes include walnut joinery, marble and travertine floors and light granite wall cladding with stainless steel detail insets. Externally dark zinc cladding covers the sculptural forms with textured granite used on feature wall and the floors. A double-volume living area, with a curved glass wall façade facing the lake, flows into the dining area and kitchen on the ground floor while the bedrooms and en-suites are located on the top level. Furniture with organic and rounded shapes were selected to accommodate the irregular shape of the main living spaces, with the living room divided into two zones, a formal and informal area that are centred around the feature fireplace – a suspended black flue and fire dish secured to the floor.

Comfort in this generous, open-plan layout is achieved using modular furniture pieces, such as Arne sofas from B&B Italia, that can be easily reconfigured to create continuity between the two living areas. Custom GT armchairs by South African studio OKHA and a leather pouffe by Dominique Perrault and Gaëlle Lauriot-Prévost add to the luxe layering, further bridging the gap between formal and informal spaces. This blurring of African and European provenances continues with the mix of organic-shaped patchwork Nguni rugs, African-inspired ceramics by Louise Gelderblom, a colourful portrait from Parisian artist Françoise Nielly and a horse lamp from MOOOI. An eye-catching wall of randomly patterned Chandore stone with recessed strips of stainless steel becomes an architectural feature in itself.

The dining room features a glass OKHA Vista table, which complements the glass and timber screen wall panel behind. Wooden slats on the glass screen match the timber panelling of the bar area, with polished steel OKHA Frame barstools complimenting the dining selections. A Carolina Sardi art installation consisting of suspended yellow discs create striking focal points on the wall of the bar.

The upper level is accessed by a spiral staircase as well as a glass-cylinder encased elevator, which houses the bedrooms. A yellow-coloured Caesarstone slab for the floor, vanity and mirror wall form a striking finish in the children’s bathroom. The bath alcove walls are clad in sheets of brushed stainless steel, contrasting with the polished chrome finishes of the heated towel rails and bathroom chrome ware.

Through this symbiosis of iconic European design and an emerging African aesthetic, the interior successfully reflects the global family that live within the spaces, while achieving a nuanced layering of tones, textures and materials.

Lake House This family home and office on the banks of Lake Geneva, with architecture by SAOTA and interiors by…

#ARRCC#bathroom#bedroom#house#house idea#houseidea#kitchen#lake house#living#myhouseidea#outdoor#pool#saota#terrace#villa

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dakar in Ousmane Sembène's The Wagoner (1966)

#film#short film#african cinema#senegal#senegalese cinema#ousmane sembène#ousmane sembene#the wagoner#borom sarret#dakar#1966#mine#architecture

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A common vision for 2030 The leaders are also expected to discuss “how the two continents can build the foundations for greater prosperity,” according to the aforementioned statement, which stressed that “the goal is to launch an ambitious African-European investment package, in line with global challenges such as climate change and the current health crisis,” as well as finding viable solutions. for ways to “enhance stability and security through a renewed peace and security architecture” As for the topics on the table, they are: financing for growth, health systems and vaccine production, agriculture and sustainable development, education, culture, vocational training, migration and mobility, support for the private sector and economic integration, and peace and security. The EU statement declared that "participants are expected to adopt a joint declaration on a common vision for 2030." The European Union wants to support viable solutions to African conflicts Brussels has always considered that "the European Union wants to support African solutions to African conflicts. This includes social and humanitarian development, health and education and the transition process towards green policies, sustainable energy use, digital transformation and job creation." "Partnership presupposes exchange and sharing," Belgian European Council President Charles Michel and Senegalese African Union President Macky Sall said in a joint article. Borrell: "Europe will not be able to help Africa while instability prevails" But the EU's High Representative for Foreign Policy and Security Affairs, Josep Borrell, stressed that Europe will not be able to help Africa while instability and insecurity prevail. He said that military coups, conflicts, terrorism, human trafficking and piracy are sweeping the continent and affecting Europe. Borrell believed that the destabilization of the African continent is being fueled by "new actors" Chinese and Russian "whose methods and agendas are very different from ours." This continent, rich in raw materials, is witnessing a struggle for influence between the great powers, led by China. This #article continues https://www.instagram.com/p/CaHGXXNtyls/?utm_medium=tumblr

0 notes

Photo

10 BLACK SCHOLARS WHO DEBUNKED EUROCENTRIC PROPAGANDA October 6, 2013 | Posted by A Moore DR. CHEIKH ANTA DIOP SENEGALESE-BORN Cheikh Anta Diop (1923 – 1986) received his DOCTORATE DEGREE from the University of Paris and was a BRILLIANT historian, anthropologist, physicist and politician and one of the most PROMINENT AND PROFICIENT black scholars in the HISTORY of African civilization. Contrary to the long-standing EUROPEAN MYTH of a Caucasian Egypt, Diop’s studies into ORIGINS of the human race and PRECOLONIAL AFRICAN CULTURE established that ANCIENT EGYPT was founded, populated, AND ruled by black Africans; the Egyptian language and culture STILL EXISTS in modern African languages (including his own Wolof language); and that BLACK EGYPT WAS RESPONSIBLE FOR THE RISE OF CIVILIZATION throughout Africa AND the Mediterranean, INCLUDING Greece and Rome. Diop ALSO pioneered techniques of SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH – such as CARBON DATING as a means of dating artifacts and remains, and the MELANIN DOSAGE TEST which he used to VERIFY the melanin content of Egyptian mummies. Forensic investigators LATER ADOPTED THIS TECHNIQUE to determine the “racial identity” of badly burned accident victims. Cheikh Anta Diop University in Dakar, Senegal, is named after him. Source: cheikhantadiop.com DR. JOHN HENRIK CLARKE Dr. John Henrik Clarke (1915 – 1998) was a Pan-Africanist writer, historian, professor, and a pioneer in the establishment of Africana studies in PROFESSIONAL INSTITUTIONS in academia starting in the late 1960s. He was professor of AFRICAN WORLD HISTORY and in 1969, he became the FOUNDING chairman of the Department of BLACK AND PUERTO RICAN STUDIES AT HUNTER COLLEGE of the City University of New York. He ALSO was the Carter G. Woodson Distinguished Visiting Professor of African History at Cornell University’s Africana Studies and Research Center. He CHALLENGED the mostly white academic historians and attributed THEIR RELUCTANCE TO ACKNOWLEDGE the HISTORICAL CONTRIBUTIONS of black people as part of the systematic AND racist suppression and distortion of African history. Clarke asserted: ”NOTHING IN AFRICA HAD ANY EUROPEAN INFLUENCE BEFORE 332 B.C. If you have 10,000 YEARS behind you before you even SAW A EUROPEAN, then WHO GAVE YOU THE IDEA that he moved from the ICE-AGE, came all the way into Africa AND built a great civilization AND disappeared, when he had NOT built a shoe for himself or a house with a window?” Source: Africana.library.cornell.edu/africana/clarke/index.html DR. MARIMBA ANI Dr. Marimba Ani is an ANTHROPOLOGIST AND AFRICAN STUDIES SCHOLAR best known for her book “YURUGU,” a comprehensive critique of European thought and culture. She COMPLETED her Bachelor of Arts degree at the University of Chicago, and holds MASTERS AND DOCTORATE DEGREES in anthropology from the Graduate Faculty of the New School University. In her GROUND-BREAKING WORK, “Yurugu: An Afrikan-Centered Critique of European Cultural Thought and Behavior,” Ani uses an AFRICAN PERSPECTIVE through the myths of the DOGON PEOPLE and the LANGUAGE OF SWAHILI to examine the IMPACT of European cultural influence on black people and the world. She DEVELOPED a framework that METHODICALLY DEBUNKED the belief that Western civilization was the best, most constructive society ever built and instead she pointed out its inherent DESTRUCTIVE tendencies. Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marimba_Ani DR. AMOS WILSON Dr. Amos N. Wilson (1941 – 1995) was a SOCIAL CASEWORKER, PSYCHOLOGICAL COUNSELOR, SUPERVISING PROBATION OFFICER and TRAINING ADMINISTRATOR in the New York City Department of Juvenile Justice. He was ALSO an assistant professor of psychology at the City University of New York. In his book “Black-on-Black Violence: The Psychodynamic of Black Self-Annihilation in Service of White Domination,” Wilson, DISCREDITED THE PERVASIVE MYTH that blacks are inherently criminal. NOT ONLY did he chronicle the vast history of VIOLENCE that was pervasive in American culture, but he ALSO demonstrated HOW black-on-black violence and black male criminality in the United States WAS A POLITICALLY AND ECONOMICALLY ENGINEERED PROCESS designed to MAINTAIN the subservience and relative powerlessness of black people and black communities worldwide. However, Wilson contended that bringing an END to black-on-black violence and criminality is the SOLE RESPONSIBILITY OF ALL BLACK PEOPLE. In his book he lays out practical AND theoretical ways of eradicating it. Source: Awis.scripterz.org IVAN VAN SERTIMA Dr. Ivan Gladstone Van Sertima (1935 – 2009) was a Guyanese-born ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR of Africana Studies at Rutgers University in New Jersey. He was BEST KNOWN for his work “They Came before Columbus,” which provided a PYRAMID OF EVIDENCE to support the IDEA that ANCIENT AFRICANS WERE MASTER SHIPBUILDERS who sailed from AFRICA TO THE AMERICAS THOUSANDS OF YEARS BEFORE Spanish explorer Christopher Columbus, and that the Africans TRADED with the indigenous people, leaving lasting influences on their cultures. In one example, Van Sertima presents EVIDENCE that EMPEROR ABUBAKARI OF MALI used these “almadias” or longboats to make a TRIP TO THE AMERICAS during the 1300s. Van Sertima methodically demonstrates that these blacks WERE NOT SLAVES, but traders and priests who were HONORED AND VENERATED BY THE NATIVE AMERICANS who built statues – Olmec heads- IN THEIR HONOR. In the closing of the book, he declaimed the notion of “discovery” by Columbus. In 1987, Van Sertima TESTIFIED before a United States congressional committee to OPPOSE RECOGNITION of the 500th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ “discovery” of the Americas. He said, “You CANNOT really conceive of how INSULTING it is to Native Americans … to be TOLD they were discovered.” Source: raceandhistory.com/historicalviews/ancientamerica.htm DR. FRANCES CRESS WELSING Dr. Frances Cress Welsing is an African-American PSYCHIATRIST practicing in Washington, D.C. She is noted for authoring the “Cress Theory of Color Confrontation” and “The Isis Papers: The Keys to the Colors,” which explore AND define the global system of white supremacy. In “The Isis Papers,” Welsing contradicts the notion that white supremacy was rooted in an idea of genetic superiority. Instead, she presents a PSYCHOGENETIC THEORY suggesting whites FEAR genetic annihilation because their genes ARE recessive to the majority of the world’s population, which consists of people of color – the most threatening being black. Therefore they established white supremacy to PREVENT people of color from diluting their genes and subsequently rendering them extinct. Source: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frances Cress Welsing DR. YOSEF BEN-JOCHANNAN Dr. Yosef Alfredo Antonio Ben-Jochannan, also known as Dr. Ben, is an Ethiopian-Puerto Rican WRITER, HISTORIAN AND EGYPTOLOGIST. Ben-Jochannan earned a Bachelor of Science degree in CIVIL ENGINEERING at the University of Puerto Rico in 1938, and earned his master’s degree in ARCHITECTURAL ENGINEERING from the University of Havana, Cuba in 1938. He received his doctoral degrees in CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY AND MOORISH HISTORY from the University of Havana and the University of Barcelona, Spain, respectively. Ben-Jochannan is the AUTHOR OF 49 books, primarily on ancient Nile Valley civilizations AND their impact on Western cultures. One of Dr. Ben’s most thought-provoking works, “African Origins of the Major ‘Western Religions’” (1970), highlights how the roots of Judaism, Christianity and Islam originated in black Africa. He also ARGUES that the ORIGINAL JEWS WERE FROM ETHIOPIA AND WERE BLACK AFRICANS, while the European Jews later ADOPTED the Jewish faith and its customs. http://www.thehistorymakers.com/biography/yosef-ben-jochannan-41 http://www.raceandhistory.com/Historians/ben_jochannan.htm http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yosef_Ben-Jochannan DR. ANTHONY MARTIN Dr. Anthony Martin (1942 – 2013) was a Trinidadian-born PROFESSOR of Africana Studies at Wellesley College, Massachusetts. He was a lecturer AND prolific author of scholarly articles about black history AND was considered the world’s foremost AUTHORITY ON JAMAICAN BLACK NATIONALIST LEADER MARCUS GARVEY. Martin authored, compiled or edited 14 BOOKS, his earliest work being “Race First: The Ideological and Organizational Struggles of Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association” (1976). In his works on Garvey, Martin used his scholarship to COUNTERACT attempts by the mainstream to mischaracterize and deny Garvey’s TRUE LEGACY as one of the GREATEST black leaders of all time. When Martin detailed the ROLE European Jews played in the transatlantic slave trade in his book, “The Secret Relationship between Blacks and Jews,” the professor found himself the subject of a CHARACTER ASSASSINATION campaign, which is ONGOING even after his death. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tony_Martin_%28professor%29 http://www.blackbluedog.com/2013/01/news/dr-tony-martin-noted-scholar-and-proponent-of-pan-africanism-passes-away/ DR. CHANCELLOR WILLIAMS Dr. Chancellor Williams (1893 – 1992) was an African-American sociologist, historian and writer. His BEST KNOWN work is “The Destruction of Black Civilization: Great Issues of a Race from 4500 B.C. to 2000 A.D.”, for which he was AWARDED honors by the Black Academy of Arts and Letters. In “Destruction of Black Civilization,” Williams chronicles how HIGH CIVILIZATION BEGAN IN BLACK AFRICA, contrary to what mainstream historians have espoused to the world. He meticulously lays out the history of Africa in GREAT DETAIL AND DEMONSTRATES that the continent’s current underdevelopment came after thousands of years of consistent onslaught by Eurasians, and not because Africans made no significant contributions to the world. http://aalbc.com/authors/chancell.htm http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chancellor_Williams www.goodreads.com/author/show/72450.Chancellor_Williams DR. GEORGE G.M. JAMES Dr. George Granville Monah James (unknown – 1954) was a well-regarded historian and author from Georgetown, Guyana. He’s best known for his 1954 book “Stolen Legacy,” in which he PRESENTED EVIDENCE that Greek philosophy ORIGINATED IN ANCIENT EGYPT. He gained his DOCTORATE DEGREE at Columbia University in New York, became a PROFESSOR OF LOGIC AND GREEK at Livingstone College in Salisbury, N. C., for two years, and then taught at the University of Arkansas, Pine Bluff. In “Stolen Legacy,” James painstakingly DOCUMENTS the African ORIGINS of Greco-Roman philosophical thought. He asserted that “Greek philosophy” WAS NOT created by the Greeks at all, instead it was BORROWED WITHOUT ACKNOWLEDGMENT OF the ancient Egyptians. James even CHALLENGED the foundations of Judaism AND Judeo-Christianity and argued that the STATUE of the EGYPTIAN GODDESS ISIS with her child Horus in her arms is the ORIGIN of the Virgin Mary and child. He MYSTERIOUSLY DIED, shortly after publishing Stolen Legacy. http://www.africaresource.com/rasta/sesostris-the-great-the-egyptian-hercules/george-gm-james-guyanas-shining-star-a-tribute/ Artwork by: Citizins

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ten architecturally impressive hospitals that aim to redefine healthcare

Following The Friendship Hospital in Bangladesh being named the world's best building, we have rounded up 10 other architecturally impressive medical facilities from across the globe.

Photo is by Iwan Baan

Tambacounda Maternity and Paediatric Hospital, Senegal, by Manuel Herz Architects

Characterised by its lattice-like brickwork, this maternity and paediatric clinic designed by Swiss studio Manuel Herz Architects, is an extension to an existing hospital.

It has a distinctive S-shape which curves around other buildings on the site to create new courtyards as well as encouraging airflow to manage temperatures in the scorching Senegalese climate.

Find out more about Tambacounda Maternity and Paediatric Hospital ›

Photo is by Rubén P Bescós

Centro Psicogeriatrico San Francisco Javier, Spain, by Vaillo+Irigaray Architects

Spanish studio Vaillo+Irigaray Architects modernised this 19th-century psychiatric centre in the city of Pompolona.

The designers added concrete structures shaped and dyed to mimic the older buildings on the site, cantilevered above glazed walls to create sheltered walkways and give the impression that the heavy volumes are floating.

Find out more about Centro Psicogeriatrico San Francisco Javier ›

Photo is by Irfan Naqi

Bamyan Provincial Hospital, Afghanistan, by Arcop

Nestled in a valley in Afghanistan's highlands, Bamyan Provincial Hospital is organised around a series of courtyards that become increasing private the further one ventures into the complex.

"Overall, our attempt is to take a 'biophilic' approach to design," said Pakistani architecture studio Arco.

"Through natural light and ventilation, views of mountains and gardens and access to outdoor courts, an architecture is created which fosters healing and well-being."

Find out more about Bamyan Provincial Hospital ›

Harvey Pediatric Clinic, USA, by Marlon Blackwell Architects

Located in the suburbs of a small city in northwest Arkansas, Harvey Pediatric Clinic has an irregular shape and a bright red facade intended to make it stand out from its surroundings.

American firm Marlon Blackwell Architects said the design reinforces the progressive identity of the clinic, which takes a holistic approach to treating children.

The project was shortlisted at the 2017 World Building of the Year awards, hosted by the World Architecture Festival.

Find out more about the Harvey Pediatric Clinic ›

Photo is by Elizabeth Felicella

Bayalpata Hospital, Nepal, by Sharon Davis Design

Created by New York-based Sharon Davis Design, the Bayalpata Hospital medical campus is located a 10-hour drive on mountain roads from the nearest manufacturing centres in one of Nepal's poorest and most remote regions.

To make the project feasible the designers focused on using local materials, including rammed earth made with soil from the site itself for the walls, stone for the foundations, and wood from the indigenous sal tree for the doors, window louvres and furniture.

Find out more about Bayalpata Hospital ›

Photo is by Andre Cepeda

Epilepsy Residential Care Home, France, by Atelier Martel

This facility in the northeastern French town of Dommartin-lès-Toul provides both long- and short-term care to people living with epilepsy.

Designed by Paris-based practice Atelier Martin in collaboration with American artist Mayanna von Ledebur, the building's concrete facade is covered in hundreds of soft indents in reference to the markings found on an ancient tablet from 600 BC believed to be the first written record of epilepsy.

Find out more about Epilepsy Residential Care Home ›

Photo is by Tristan McLaren

Nelson Mandela Children's Hospital, South Africa, by Sheppard Robson and John Copper Architecture

Designed by London studios Sheppard Robson and John Cooper Architecture in partnership with local office GAPP, this 200-bed children's hospital in Johannesburg is deliberately divided into six separate wings linked by a single spine.

"By breaking down the mass of the building into six elements, the design has a domestic, human scale that is reassuring and familiar to children," said Sheppard Robson.

Find out more about Nelson Mandela Children's Hospital ›

Photo is by Peter Landers

Kachumbala Maternity Unit, Uganda, by HKS Architects and Engineers for Overseas Development

Kachumbala Maternity Unit, in rural eastern Uganda, is entirely self-sustaining, generating its own power from solar panels and collecting rainwater from roof runoff to create its own water supply.

HKS Architects and Engineers for Overseas Development designed the birth centre to be built using local skills, technology and materials, including external walls made from terracotta screens.

Find out more about Kachumbala Maternity Unit ›

Waldkliniken Eisenberg, Germany, by Matteo Thun & Partners and HDR Germany

Milan-based design studio Matteo Thun & Partners and German architecture firm HDR Germany designed this new wing of the Waldkliniken Eisenberg orthopaedics centre to feel more like a hotel than a hospital.

Surrounded by trees in the Thuringian Forest, the circular building has shared winter gardens between adjacent rooms, while pervasive use of wood, green roofs and planted courtyards are intended to enhance the connection with nature.

Find out more about Waldkliniken Eisenberg ›

Cancer Centre at Guy's Hospital, UK, by Rogers Stirk Harbours + Partners

This dedicated cancer treatment clinic at Guy's Hospital in London was built in the inimitable style of Rogers Stirk Harbours + Partners, made famous by its co-founder, the late Richard Rogers.

Services are arranged in four stacked "villages" designed to make the environment feel human-scaled and non-institutional, while bare concrete walls contrast with pale timber walkways and exposed metalwork.

Find out more about the Cancer Centre at Guy's Hospital ›

The post Ten architecturally impressive hospitals that aim to redefine healthcare appeared first on Dezeen.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

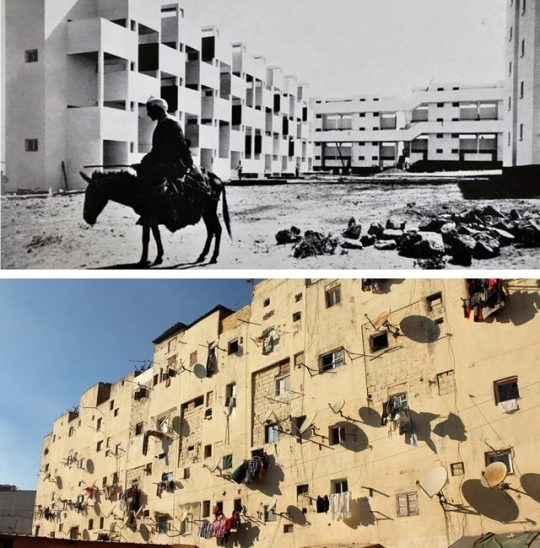

”I recently traveled to Algeria to do some researches for my next book dedicated to the space of the French state of emergency; I am hoping to write a few of these non-rigorous articles about it soon but, in the meantime, I would like to write a short piece about a national liberation struggle against the French colonial empire we usually evoke less often than the Algerian Revolution: the Moroccan liberation struggle. One moment of this struggle is of particular importance when evoking the relationship between colonialism and architecture, in particular when comparing it with the strategies adopted by the successive French governments in Algeria in the years that will follow this specific moment. The event considered here consists in two days of strike and protests organized by the Moroccan worker union confederation (UGSCM) and the main Moroccan nationalist party (Istiqlal) in December 1952, described precisely by Jim House in an essay entitled “L’impossible contrôle d’une ville coloniale?” (The Impossible Control of a Colonial City?”, Genèses vol. 86, 2012). Although this article is partially motivated by the attempt to translate some components of House’s depiction of the 1952 strike (what the first part of this article is dedicated to), it also finds its motive in the absence in his paper of consideration for the massive urban transformation that the colonial authorities were undertaking at that time. This, as well as what it tells us about architects’ responsibilities in the colonial counter-revolution, will therefore make for the second part of this article.

An Anti-Colonial Event in Casablanca’s Carrières Centrales ///

On December 5, 1952, Tunisian nationalist and union member Ferhat Hached is assassinated in a plot that seems to involve the French colonial authorities in Tunisia. As a transnational response, the Moroccan UGSCM and the Istiqlal organize a general strike in Morocco on December 7. This strike finds its core in the shantytown of the Carrières Centrales (now Hay Mohammadi) in Casablanca where over 130,000 colonized people reside. Some of them moved here from rural areas of the country; others were displaced in 1938 from the city center after a typhoid epidemic was used by the authorities as a pretext to destroy smaller shantytowns adjacent to the “European quarters” and expel their residents outside of what were then the city limits. The massive shantytown that therefore exists in the beginning of the 1950s is considered by the French authorities as a political threat to the colonial order — we will see in the second part in what the subsequent counter-revolutionary strategy consisted. Consequently, a specific suppression plan has been created to respond to any anti-colonial movement in the Carrières Centrales: in addition to the French and Moroccan (the latter being under the orders of the makhzen) police officers, the colonial authorities have imagined several layers of military reinforcements such as Moroccan or Senegalese tirailleurs (infantrymen), goums (Berbere military units), and other branches of the colonial army.

The strike originally organized by the Istiqlal is called a “mouse strike.” It consists in simply refusing to leave home to go to work. In the evening of December 7 however, town criers circulates in the shanty town to declare that the strike is forbidden and that everyone will have to open their shops like any regular day. Moments later, the police open fire on residents who were throwing stones at them in response to the interdiction. Demonstrators gather in front of the local police station; some are shot and killed. Police officers then undertake to search the shantytown and enters systematically into the houses, while nationalist activists are arrested. The next day, settlers who live close by are evacuated and more shot are fire by the police in the neighborhood, killing in particular a 15 year-old boy who was digging a trench inside his house to protect his family. In the afternoon of December 8, a massive march is organized, leaving the Moroccan poor neighborhoods and heading to the city center, towards the Union House, where a meeting is scheduled. When later describing the events, the French press evoke the “attempt to invade the European city.” The police fires and kill at least 14 people in the march. Many others are arrested. Some are released in small numbers among a crowd of settlers who proceed to assault them. Meanwhile, important military reinforcements are called to circumscribes poor Moroccan neighborhoods. Scout planes fly at low altitude above these neighborhoods in an effort that has as much to do with surveillance than it has with intimidation. Similarly, light tanks and machine guns parade around the Carrières Centrales. Within the neighborhood itself, the Moroccan police force residents to open their shops and destroy those that remain close, in what prefigures the French response to the FLN-organized general strike in Algeria five years later.

During the days that follow, thousands of police officers and soldiers are deployed in Moroccan neighborhoods, and 1206 people are judged guilty of harming the state orders by the colonial courts. Some of the arrested protesters are tortured by electricity in police stations — here again prefiguring the following years of the Algerian Revolution (1954-1962). 51 French union members, close from the Moroccan Nationalist movement are also deported back to France. As it is often the case with colonial massacres (the state having a strong interest to prevent the archive to exist), the number of protesters killed during these days of suppression remain unclear, but is believed to be between 100 and 300. (Jim House, “L’impossible contrôle d’une ville coloniale?“, 2012).

Architects and the Counter-Revolution ///

As mentioned above, the information provided by Jim House in his essay are extremely valuable, but also miss to mention how the Carrières Centrales were simultaneously the site of a drastic urban transformation that remains today well-known in the history of architecture. The political and historical account therefore fails to involve architecture and, unsurprisingly, most of the architectural account fails to involve the violence of colonialism or does so with too little insistence. During his tenure as director of the Morocco Department of Urban Planning (1946 to 1952) French architect and urban planner Michel Ecochard designed a master plan for the Carrières Centrales, along with his collective, whose name, GAMMA for Groupe d’Architectes Modernes Marocains (Group of Moroccan Modern Architects), deceives about which kind of architects were involved (“Moroccan” here means French and Western in Morocco, such as Shadrach Woods or Georges Candilis).

As mentioned above, this master plan and its recognizable 8×8 meter grid, as well as his (more or less orientalist) attempts to adapt it to the Moroccan population, belongs to the canonical history of architecture. In the rare occasions that the political context of this project is mentioned (not ‘simply’ the French colonial order in Morocco, but also the suppression of the Moroccan Nationalist movement), such a context is understood as the background of the project, rather than its very essence. This is, in my opinion, a fundamental dimension to understand, not simply the role of architecture here; not even only the relationship that architecture maintains with colonialism, but even more broadly, the very function of architecture in its crystallization and enforcement of political orders (and, in a very few occasions perhaps, disorders).

In other words, we should not simply be struck by the fact that the 1952 massacre happened while the urban transformation of the shanty town was happening — if anyone knows of any photographs that would show the strike in relation to the construction site, please contact me! — we should consider this transformation as the colonial effort to shut the anti-colonial movement down, as it will later be the case in Algeria in the late 1950s with the construction of massive housing complexes by the French authorities as the second counter-revolutionary wave (after and simultaneously with the legal and military one) against the anti-colonial Revolution. Of course, the project itself is not in response to the 1952 strike but, rather, it constitutes a preemptive response to such a political struggle. Affirming this is not a proposal to reread history through the prism of a colonial conspiracy involving architects and urban planners at every level of military and administrative decisions. I have not personally read of any account involving Ecochard and the military regarding the counter-revolutionary characteristics of his urban design and do not know if any exist — nor did I for Fernand Pouillon in Algiers a few years later. However, the degree of intentionality manifested by architects when it comes to participating to the colonial order is secondary when the clients consist precisely in the guardians of such an order, and that architects consist in members of the settler society. Furthermore, through its extreme valuing of rationality, modern architecture, perhaps more than any others, embody the ideal spatial paradigm when it comes to population control (see this 2014 article about Brasilia for instance) and the framing of most aspects of the daily life of its residents. The various modernist housing complexes built by the French colonial authorities in Morocco and Algeria should therefore be seen at both political and operative levels for what they are: architectural counter-revolutionary weapons.

Architecture and the Anti-Colonial Revolution ///

As expressed countless times on The Funambulist, I am convinced that architecture has a propensity to embody the colonial order. Its intrinsic violence easily materializes the walls that the colonial state necessitate to sustain itself, and nothing is easier than to extrude a line traced a map where borders are colonial constructions. A part of me still believes that an anti-colonial design can be achieved if somehow one accepts to embrace such an intrinsic violence in favor of an anti-colonial agenda. Nevertheless, the relationship between architecture and the anti-colonial revolution is never greater than when the order embodied by the former is subverted (voluntarily or not) in favor of the latter. Although the liberation of Morocco occurred in 1956 and that it is doubtful that such a process had been already achieved by then in the Ecochard grid in the Carrières Centrales, the visit of the modern architecture of current Hay Mohammadi certainly suggests such a subversion in the difficulty we might even experience trying to recognize it. Of course, the subversion here was mostly based on the appropriation of a domestic space for daily needs, not on the political anti-colonial effort; yet, just like settler architects do not need to voluntarily contribute to the colonial order to actually do so, colonized and post-colonial residents (Hay Mohammadi remains a proletarian neighborhood today) do not need to voluntarily subvert this order to actually do so. If we may conclude with an ultimate comparison with Algiers, the Casbah did not need to be politically transformed to constitute an ideal spatial condition for the Algerian Revolution, its continuous existence in discrepancy with colonial logic, as well as its embodiment of a multitude of rational processes (in opposition to a uniform one, always manifested in a master plan), made it this way. May the following photographs in comparison to the previous one of the Ecochard grid therefore represent less the effectiveness of a past anti-colonial struggle, than the symbol of its potentiality in the present or the future in the subversion to the colonial order they incarnate.

- Léopold Lambert, “CASABLANCA 1952: ARCHITECTURE FOR THE ANTI-COLONIAL STRUGGLE OR THE COUNTER-REVOLUTION.” The Funambulist.

Photographs provided by Léopold Lambert & Hay Mohammadi.

Top to bottom:

1) The Ecochard master plan and the shanty town. / Photothèque du ministère de l’habitat marocain.

2) March of the strikers towards the Casablanca city center on December 8, 1952

3) The so-called building “Nid d’Abeilles” (Bee Hive) designed by Georges Candilis and Sadrach Woods in 1952 and in 2016.

#Nid d’Abeilles#casablanca#georges candilis#morocco#Moroccan liberation struggle#french colonial empire#fourth republic#french history#urban planning#urban architecture#colonial massacres#anti-colonial struggle#shanty towns#squatters#social housing#michel ecochard#architects of empire#moroccan history

2 notes

·

View notes