#peter grimwade

Text

In Logopolis episode 4, aired March 21, 1981, Tom Baker's Doctor regenerated into Peter Davison's Doctor. In a departure from past and future regenerations, Davison's Doctor helped prepare for his own death as a mysterious character known as the Watcher. In the episode the Doctor died falling from a radio telescope in a battle with the Master. The episode also marked the last time the Doctor was listed as Doctor Who in the credits until the revived series. ("Logopolis: Part Four", Doctor Who TV Event)

#nerds yearbook#real life event#first appearance#sci fi tv#bbc#march#1981#doctor who#dw#time travel#peter grimwade#christopher h bidmead#5th doctor#doctor 5#4th doctor#doctor 4#tom baker#peter davison#logopolis#k9#the master#anthony ainley#seti#janet fielding#tegan jovanka#matthew waterhouse#adric#sarah sutton#nyssa of traken#nyssa

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

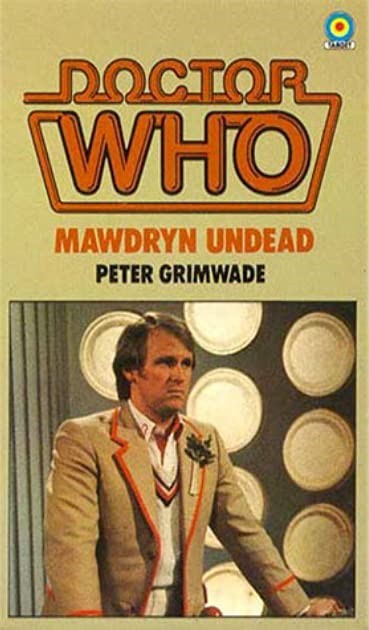

Mawdryn Undead (Doctor Who) by Peter Grimwade

Rating: ❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️

#mawdryn undead#doctor who#Peter Grimwade#books#book recommendations#sorry about the photo best one I could find#book reviews

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Panopticon V: Miss-Gendered by Worzel Gummidge

Panopticon V (Organised by @DWASonline): Miss-Gendered by Worzel Gummidge, aka the Third #DoctorWho

During the early 1980s, after becoming a ‘proper’ Doctor Who fan in 1979, I joined the Doctor Who Appreciation Society — I was a member for a couple of years. I’d receive my copy of The Celestial Toymaker, via Royal Mail, and scour its three or so pages of A4 for any titbit of news and peruse the many adverts for fanzines, information sheets, and posters that numerous local groups and the society…

View On WordPress

#Brigadier Lethbridge-Stewart#Doctor Who and the Nightmare of Eden#Doctor Who Appreciation Society#Douglas Camfield#DWAS#Fifth Doctor#Fiona Cumming#John Benton#John Nathan-Turner#Jon Pertwee#Nicholas Courtney#Nightmare of Eden#Panopticon#Panopticon V#Peter Davison#Peter Grimwade#Sergeant Benton#Terrance Dicks#Third Doctor

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hot and Cold: They Revamped Turlough's Backstory

So, here's some crazy shit I noticed while listening to BF audios that I decided to do some research on. The result is a history of Turlough's backstory and depictions of Trion from 1984 to 2013, because things have changed.

This Is a Long One Have a Break

1984-1986: The Original Backstory

Turlough's backstory was revealed in Planet of Fire, right before he left the TARDIS.

Only a year later, Peter Grimwade, who wrote the televised version of Planet of Fire and invented Turlough in the first place, wrote the novelization, which both elaborated and told a slightly different story.

This establishes that the civil war was a revolution against the Imperial Clans, which included Turlough's family.

Outside of the TV stories themselves and their novelizations, most companion backstory wasn't fleshed out until the wilderness years (1990-2004), but Turlough was one of only two companions to get a spin-off novel about what happened to him after he left the TARDIS, so more lore was dropped in 1986.

I don't have screenshots from Turlough and the Earthlink Dilemma because it's really not very good and I was told to avoid it. But, I'll give a rundown of everything important.

The Imperial Clans ruled Trion for thousands of years. They were scientists, more interested in that than ruling or leading the common people. Early on, they were authoritarian, but that changed during the reigns of the clan leaders Ykstort and Nilatis, so by Turlough's time, they mostly just let the rest of Trion govern itself. The revolution was either started or taken over by Rehctaht, who became a dictator after the Imperial Clans were overthrown.

Please remember all this alien names because I have something to say about them.

As for Turlough himself, he lived in a house in a rainforest. He studied with a friend, Juras Maateh, until they decided to specialize in different fields and went to different schools. Turlough studied astrophysics and Juras studied engineering. When the revolution started, both of them, as members of Imperial Clans, naturally supported their own people. But, when Rehctaht came to power, Juras surrendered and pretended to be loyal to her so she could work for her and use insider knowledge and technology to fight against her. Turlough remained outspoken against Rehctaht and was exiled.

Now, this whole thing is a bit silly. Remember those alien names? Ykstort and Nilatis, who made the Imperial Clans Good and Benevolent No Really? Spell them backwards. Trotsky and Sitalin, probably because Nilats wouldn't have looked as good. The people who kept the autocrats in power are named after revolutionaries who overthrew autocrats.

In a move that's really unsurprising for the 1980s, spell Rehctaht backwards. Thatcher. The evil dictator is Thatcher. That makes more sense than anything in the above paragraph.

But, it comes across like Tony Attwood, the writer, was trying a bit too hard to make sure that Turlough was on the more sympathetic side of the conflict. Peter Grimwade didn't do this. Looking at the novelization, he has Turlough being disgusted by the "barbarians" who dared to form an egalitarian government. The Imperial Clans weren't the good guys. The revolutionaries weren't really the good guys either, since they branded an infant, which good guys wouldn't do, but the civil war wasn't good vs. evil with Turlough's family on the Good Team.

But, we seem to have a writer who wanted Turlough's family to be on the Good Team, but was left wing enough that he couldn't just have the aristocratic families be the good guys by Divine Right or something. So, the Imperial Clans mostly left the common people alone, thanks to people named after Bolsheviks, and the revolution was led by a dictator named after a far right political figure. Whatever your politics, this is downright bizarre.

The Wilderness Years: People Do Interesting Things

So, the classic series ended and the show's legacy was left to the fandom. Turlough made his first reappearance in this era in 1994, with both a short story and a novel written by Craig Hinton. Hinton took charge of the Turlough Lore and added a few details, while ignoring basically everything that wasn't in the Planet of Fire novelization for sanity purposes.

Before Short Trips, there were the Virgin Decalogs, books of short stories. Zeitgeist features 5 and Turlough very shortly after Tegan left. There's a reference to them having met Sontarans somewhere between the Tegan Leaving bit and the This Story bit, which is depicted in the Virgin Missing Adventure, Lords of the Storm, which hadn't been published yet.

Anyway, the Doctor has been moping and Turlough wants him to stop moping and have fun adventures again and then the Time Lords sent them to a planet. I'm not going to recap the whole plot, since there's really only one detail we need. Turlough sees that the planet seems to be both very high-tech and very low-tech and thinks of Trion.

Turlough and the Earthlink Dilemma had Turlough living in a house in a rainforest. This is the first mention of Palaces. From here on out, Imperial Clans live in Palaces.

Another detail Craig Hinton later added, in the Virgin Missing Adventure The Crystal Bucephalus, was that the Trions had had some interaction with Gallifrey before.

(Yes, I did a word search on Turlough's name to find the right screenshot in this book. I'm very silly.)

Another Craig Hinton novel, a 6 and Mel story called The Quantum Archangel, confirms that Gallifrey colonized Trion before they started their non-interference thing.

We get more talk of Palaces in Lords of the Storm, written in 1995 by David A. McIntee. This book has 5 and Turlough land on a human colony planet that is basically Space India, with Turlough finding himself feeling almost at home there.

Now we have a specific Trion palace. Along with similarities in architecture and climate, there are cultural similarities. The Imperial Clans are apparently at the top of a caste system, similar to that of India.

We have the Meridian City and the Meridian Palace. It's never outright stated, but the book seems to imply that that's Turlough's home, a palace in a big city divided by caste. Previously, it was implied that Imperial Trions mainly lived outside of the cities, separated from the common people.

It's also interesting that Trion is compared to India here. The Time Lords are basically the Space British Empire on the Decline. So, Trion was a colony of Gallifrey as India was colonized by the British.

The general idea of the Trion civil war as a revolution against the Imperial Clans stuck around after this. What stuck around even more was the small detail of Turlough's home being in a rainforest, or at least a very warm climate compared to that of England. India is big and has a variety of climates, but all of it is warmer than England.

The King of Terror, in it's sole positive contribution to the Whoniverse, has the Doctor speculate on what Turlough's homeworld, which he naturally still doesn't know the name of, might be like.

This novel also has it proven that Turlough has higher heat resistance than a human. A hot, heavy atmosphere would fit the description of a wet, tropical area, like a rainforest. As for Turlough's health problems in Earth's atmosphere, it's thinner than Trion's. When you go to a high altitude, the air gets thinner and this can cause altitude sickness, which can cause nausea and headaches. Turlough basically has altitude sickness all the time on Earth. Not sure about the rest of it.

Jumping over to the audios, we have Loups-Garoux, written by Marc Platt, taking over from Craig Hinton as the Keeper of Turlough Lore. Turlough meets a girl named Rosa in the late 21st century, when the Amazon rainforest is gone. Rosa is Inexplicably Magical and has a sort of ghost of the Amazon in her brain. A brainforest, if you will. (Sorry). This gets Turlough talking about the forests on Trion.

Since the forests of Trion are directly compared to the Amazon here, it would fit with them being rainforests, though there's now a mention of winter, a cold season. Most tropical areas, unless they're right on the equator, basically, have something resembling seasons. I'm guessing that Trion summer is Very Hot, while Trion winter is just Hot. Trion winter is cold by Trion standards.

Now, let's jump far into the future:

2011-2013: The Part Where Things Start to Change

With novels no longer being a regular occurrence, we're talking only about audios now. Starting in 2010, Big Finish began a series of audio stories featuring an Older Nyssa traveling with Tegan and Turlough. The stories were released in trilogies. In the first trilogy, nothing has really changed. The Cradle of the Snake has Turlough be from a place that has a lot of snakes, which could fit a variety of climates, but mainly warmer ones.

Then we get to the second trilogy and Kiss of Death and things begin to change.

The Imperial Clans still exist, since Turlough mentions belonging to a clan and there's a lot of stuff about what his ancestors were up to.

Turlough's family still lives in a palace, but the climate is the complete opposite. Now the Turlough family owns its own planet, the Winter Planet, which is exactly what it sounds like, a planet covered in snow and ice. And the palace they live in is The Winter Palace. So, we're back in Russia, though the parallels with the Imperial Clans here make more sense than the ones in The Earthlink Dilemma.

Basically, with Turlough being from a ruling family overthrown in a revolution, Stephen Cole might've added a Winter Palace and made the whole thing parallel the Russian Revolution.

I'd also like to called attention to the character of Deela, surprisingly. I usually prefer to ignore her. She's basically Turlough's girlfriend from before he was exiled. They're both from the same Imperial Clan, but the clan is apparently big enough to include people who aren't biologically related so it's Totally Not Weird that they were a couple. Still, the story treats the Winter Planet/Palace as if it both belonged to Deela's father and Turlough's ancestors, with the two apparently growing up together...You know what? Everything about this is confusing and we're moving on.

I actually wanted to bring up Deela because of Juras Maateh. Remember her? Turlough's best friend in the Earthlink Dilemma? Juras was a childhood friend, who happened to be a girl, and she and Turlough were eventually separated by the revolution. Deela was Turlough's girlfriend, and childhood friend before that, whose father picked the opposite side of the revolution from Turlough's father, making the two star-crossed lovers. Deela feels like a more romantic version of Juras, as well as a younger version. Turlough and Juras began on the same side before Juras chose to surrender, secretly still on the same side. They were both adults picking what side they were on for themselves. With Turlough and Deela, it was all their fathers' politics and they were just teenagers who didn't care.

Turlough gives Nyssa a recap of the same information he'll later give the Doctor in Planet of Fire

This fits with the televised version, removing the elements from the novelization. There's no mention of a rebellion against the Imperial Clans and Turlough is forced to participate. The televised version had him say his father was on this losing side, implying that he was punished because of his father's politics and had no say in the matter. The novelization implies a more active political role on Turlough's part, which the Earthlink Dilemma depicts.

Also, there's some different wording regarding Turlough's father and brother. Earlier versions say they were exiled. Here, they ran away, as if they fled the war to Sarn, leaving Turlough behind.

It's at this point that Turlough's backstory starts to become a bit unstable. Let's jump ahead two years to Eldrad Must Die, another Marc Platt story. Turlough meets up with Charlie Gibbs, a kid he knew at Brendon. But, the story takes place in 2013. Gibbs has been living on Earth, I think, for thirty years and Turlough shows up, appearing to have never aged a day. But, that's not as important as Gibbs having an agenda that Turlough gets roped into. A lot of confusing things are said.

So, there were other Trions at Brendon the whole time and Turlough didn't know. Instead of being exiled by the government after the revolution, it seems that both sides "sold off" people during the war. Gibbs was on the winning side, but he ended up at Brendon anyway.

Also, Brendon was apparently a place to "shuttle stateless exiles into safety", when in Turlough's case, it was clearly a prison. An "underground railroad" would imply that exiles would be moving through there, not stuck there. Also, who does the solicitor on Chancery Lane even work for if he aids both sides?

And it only gets more confusing from here.

I'm not sure what the City is supposed to be. Also, Turlough was a slave? Someone who he apparently works for got him out of slavery and sent him to Earth. I'm guessing his status as an exile is unofficial. If he goes back to Trion, Bad Things Will Happen, but the Trion Government didn't send him there.

I honestly have no idea what's supposed to be going on by this point. Something to do with sponsors, a solicitor, killing Eldrad, and way too many other things.

My best guess is that this new backstory is:

Trion had a civil war over Something. Turlough's mom was killed and his dad and brother fled. Turlough was forced to fight in the war on his father's side, but he got captured and sold into slavery. Some Shady Organization made a deal with him to free him in exchange for working for them and they sent him to Brendon, where nothing happened for several years until the Black Guardian got involved. So Turlough made a deal with the devil to get out of a bad place twice.

Compared to what came before it, it's really vague and I have no idea if I even understood it correctly. I could poke so many holes in it. Outside of the stuff we were ignoring anyway, nothing was wrong with the first backstory, so I have no idea why it was redone like this. It's frustrating and I Don't Like It.

I'm still going to use my own personal version of Turlough's backstory, where there was an uprising against the Imperial Clans, Turlough's mom was killed in what was basically a terrorist attack, but when these attacks evolved into full on war, Turlough joined the military both to avenge his mother and because his father wanted him to. He got captured and spent some time as a prisoner of war until the revolutionaries officially won. His father hadn't technically fought in the war, just sided against the revolution, so he and his baby son, whose only crime was being born into an Imperial Clan, were sent to a prison planet. Turlough, having fought in the war, was exiled out of Trion space entirely. Since he was so young, they sent him a school on Earth as a sort of attempt at reeducation. They didn't know enough about the school to realize that it wouldn't teach him anything they wanted him to learn.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

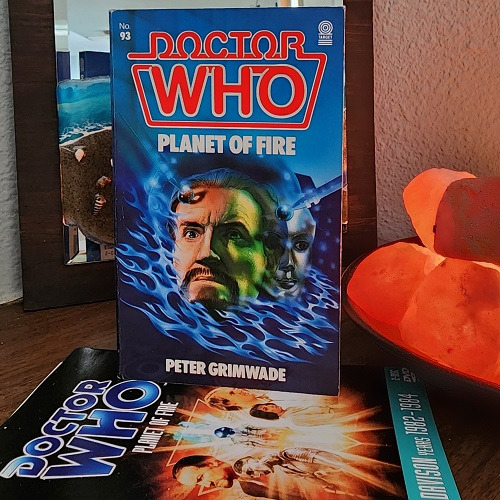

Planet of Fire by Peter Grimwade

‘Don’t be worried my boy,’ continued the old man. ‘It can be a most rewarding experience, and a blessed relief for those who are consumed in the flames. Doubters are such unhappy people.’

‘Is it not sometimes good to doubt?’ asked Malkon gravely.

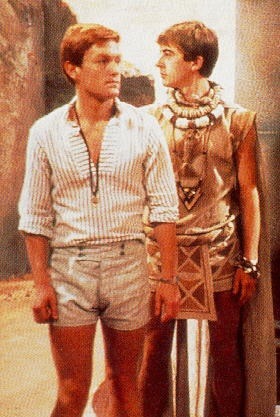

The time-travelling Doctor in need of a holiday lands on a beautiful island on Earth. But there’s little rest as a surprising connection soon surfaces amongst his companion Turlough holding back secrets, the malfunctioning shapeshifting android Kamelion, and a near drowned American tourist called Peri. Soon all are on an unplanned trip as the TARDIS is whisked to the volcanic planet of Sarn. There the inhabitants are facing catastrophic disaster while enmeshed in religious frictions. Moreover, and perhaps worst of all, is the appearance of the evil Time Lord the Master.

The requisites for Doctor Who’s 1984 Planet of Fire, as it has been succinctly put by its writer Peter Grimwade, ‘was the story’. A narrative seeing more than one character leaving, a new companion—and American at that, the Master for an antagonist, plus the very real island of Lanzarote. For someone such as Grimwade involved with Doctor Who in different capacities going back to the 1970s it also marked more than one end. It would be the director Fiona Cumming’s last for the TV series too.

So, forty years on what to make of Planet of Fire?

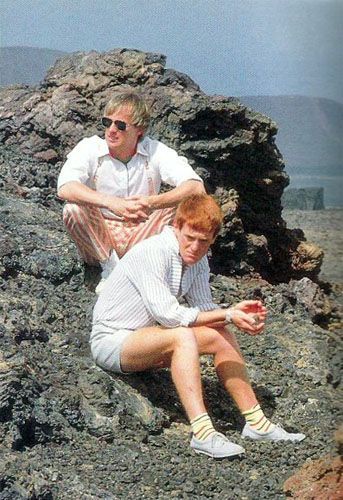

Shall we start by saying it is kind of hot? Not just fiery volcanic desert island hot but with heated issues and underlying eroticism.

Also, male homoerotism. Grimwade’s novelisation begins with a scene not in the show of an Ancient Greek vessel going down in a storm, during which one of its male merchant passengers from Rhodes clutches a kouros (i.e. young nude male statute) of the god Eros to quote ‘like a lover’. This paired centuries later by an alien Trion spaceship likewise going down on another planet. But not before releasing emergency beacons, small metallic mushroom shaped objects exhibiting a triangle symbol, one to end up of all places on Earth of course. Then, as seen on screen, both kouros and beacon to be lifted from the ocean by an archaeological team in the later part of the 20th century.

It bears mentioning Grimwade was gay, among other names involved in this story and Doctor Who. Additionally, he did love Greece and so envisioned the earthbound setting of a fictious Greek isle. Notably the earthly paradise goes unnamed in the novel, but the location filming for the serial instead was on one of the famous Canary Islands. For the classic series only the third filming destination used outside the UK and further farthest chosen at the time. Grimwade, however, was merely given photographs for his purposes. Frustrating it would also seem as he later judged the serial not working well on the screen given the cost and an excuse to go ‘on a gang bang and a nice holiday!’ Unsurprisingly too, by his own admittance had he experienced the place himself the ‘story would have been utterly different’. One can ponder how, but various details (some the writer was aware of) certainly stand out. Although the Canary Islands were known to the ancient Greeks, archaeological evidence, such that draws Peri’s professor stepfather accompanied by family, reveals Roman contact rather than Greek and further later than the period referenced.

Plus Lanzarote also does double duty for the volcanic alien world of Sarn. Grimwade may have spent a lot of time writing about aliens, but his style is one with its roots in reality. Is it surprising for a someone like him to say, 'I find it virtually impossible to write about aliens.' and 'in terms of creating an alien culture, I find it an empty exercise.' Writing on a truth (influences of classical antiquity again speckling Grimwade’s writing) Lanzarote is more contemporarily a Spanish island. But if one wanted to draw inspiration for culturally developing the people on Sarn from an older indigenous population, there are the mysterious Guanches related to the Imazighen more than the Bedouin. Since colonisation also comes up in the story interesting for the anti-colonial implications. Or ideas of the barbarous for that matter. Though the costume designer John Peacock apparently did look to ethnically complex North Africa. The aesthetics can unfortunately combine into a reading of Arab. Further the conception of the Sarns is another plot point that varies from screen to novel. One that could pose discussion on how self, and culture are formed and defined.

But back to the eros for a moment, on screen it’s visually clear the new companion character of Peri is supposed to, well, sex up things a bit. Peri (full first name Perpugilliam) Brown was outlined as an 18-year-old college student majoring in botany and, American. (Though portrayed by Nicola Bryant an English actress new on the scene with dual nationality due to marriage.) Grimwade also expressed ‘Writing for the Americans wasn’t easy either—you kind of resort to cliché ’.

Too Peri’s 40-year-old stepfather (though first imagined as older until Dallas Adams was cast) apparently the stuff of nightmares. A few lines of Peri’s would lead to speculation of an abusive childhood. (The exact nature of the abuse theorized as sexual goes back at least to the later 1980s. But not until closer to two decades later would a couple authors eventually expound on this in print form.) For its part the text of the novel version of Planet of Fire reads on the recurring nightmare how Peri was a little girl ‘sent to bed in disgrace’ pleading for Howard to not ‘put out the light’. Also later characterizing Howard’s persona with a ‘vein of ruthlessness’ through Peri’s strong emotions transferring on the automaton Kamelion who at points takes on the Howard disguise. In any event, retrospectively Peri’s character was unfortunately quickly overshadowed by the direction of the programme.

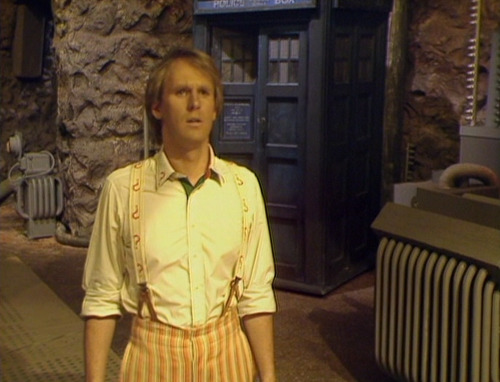

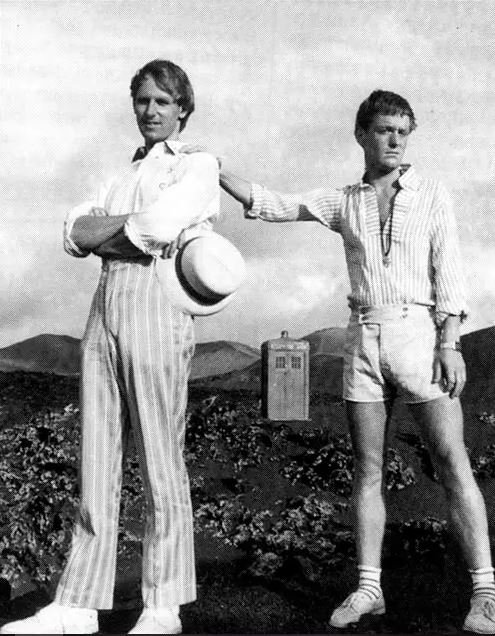

Nor did it go unnoticed for Planet of Fire that Turlough’s too dressing lighter for the climate and shedding some clothes. But to be serious the story is in large part finally Vislor Turlough’s backstory and send off. So Grimwade was a fitting, if in the end ironic, choice having been tasked to introduce the character back in 1983’s Mawdryn Undead. Carried off too with greater effect than the short lived Kamelion, meeting its demise in Planet of Fire, a real robot which had become more of a technical complication than an interesting companion. Plus, Turlough is the latter. Or cut from a different cloth at least. In Mawdryn Undead an alien mysteriously trapped in an English boys’ school on Earth. (The college used actually one Grimwade attended himself.) So desperate to escape (even not much caring if it was by death) clad in a similarly somber uniform coming under the cruel influence of another enemy of the Doctor, the Black Guardian, who tasks him to kill the Doctor. Through ten stories Turlough’s faults, though failing in murder cannot be counted as one, and his eventual progression to friendship with the Doctor brought something. Thanks to his actor Mark Strickson too. Even if companions were restrained and crowded out by other priorities as happened, the question of just what was going on with Turlough was a question. Flipping around more than the Doctor’s question mark suspenders changing direction in shots. While Turlough’s more the imperialistic brat in the novel, at points even using derogatory language, at the same time there are some really affecting moments involving him in Planet of Fire I wish were also on screen.

Speaking of reveals, it’s an intriguing choice the novel cover features an illustration by Andrew Skilleter of the Master (Anthoy Ainley) with Kamelion, two faces in a composition reminiscent of the Roman god Janus. Planet of Fire does offer the Master as a twofold villain. Ever demanding obedience, and largely enjoying every second of wielding influence at points booming ‘like a hell-fire preacher’. Bringing added turmoil as the Sarn Elders first believe he’s sent from their Fire Lord.

Contrasted by the Doctor once again attempting to allay superstition and avoid loss of life both in violence and cataclysm. A conversation between the Doctor and the Unbeliever Amyand (James Bate) on the mountainside about the Sarns, again because their origins vary between versions, goes much differently. Then if one tries to sum up Peter Davison’s Doctor in one word (though that wouldn’t do him justice) it’s probably akin to ‘nice’. So, the Doctor’s actions near the end of the story are memorable. The novel offers more insight into the Doctor’s dissonant emotions before ashen he resumes the reassuring ‘I’m… okay.’ Another much interpreted last line by the Master ‘Won’t you show mercy to your own…’ is replaced. As well the show’s poignant final scene with the, preoccupied with burning oblations, Chief Elder Timanov (Peter Wyngarde) and his faith the biggest divergence.

Then zealotry is too an important theme. As Grimwade put it ‘interested in the extremities people go to with their feelings about religion and ideology.’ The novel peppers the text with references to Greek myth, Israelites, Christianity, Islam and even an in-universe nod to the Sisterhood of Karn. But apparently a subject too hot to handle by direction from the show’s script editor, Eric Saward, the religious situation on Sarn ‘couldn’t be too strong an issue.’ At a time when audiences could easily look around them for parallels (even today), a decision that was wise or a loss? As Grimwade reflected ‘there’s a lot of very deep experience that the programme has touched on in an oblique way.’

In the end it must be more than coincidence that my favourite stories of the Fifth Doctor’s era were either directed or written by Grimwade. And if directing and writing were two different skills, they were at least linked in Grimwade’s mind as he described in writing ‘you’re directing the ideal’. Too novels gave an opportunity where ‘a lot of shortcomings can be rubbed out’. Particularly the novelizations of those serials Grimwade wrote, he once claimed were ‘the best thing about his creative involvement with the world of Doctor Who.’ Sadly, Peter Grimwade would pass away in 1990. But liking to be remembered for his stories, I remember Planet of Fire and him still today.

#scifi#doctor who#planet of fire#peter grimwade#tv novelisation#long post#bookopoly#free choice read#cw: colonisation death and of parent fire incarceration religious frictions racial slur mention civil war allusions to child (sexual) abuse

0 notes

Text

Doctor Who Mawdryn Undead.

#Mawdryn Undead#Time Lords#Time Travel#Brigadier Lethbridge Stewart#DW#DoctorWho#Books#TargetBooks#ScienceFiction#Fantasy#BookReview#VintageBooks#Classics#TARDIS#FifthDoctor#Celery#Turlough

0 notes

Photo

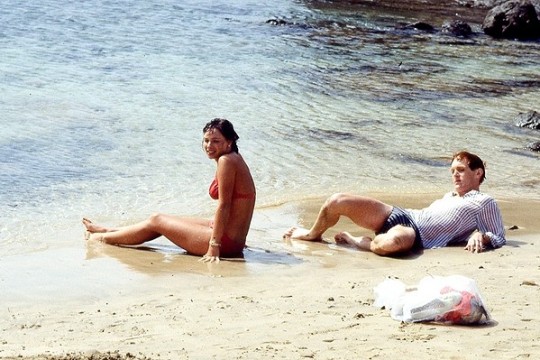

172. PLANET OF FIRE

Malkon is the chosen one of the fire god Lokar. He was found on the fire mountain as a babe and has the double triangle mark. But this mark is also on relics in Lanzarote – and on Turlough’s arm…

#planet of fire#days of the doctor#doctor who#fifth doctor#vislor turlough#peri brown#kamelion#peter grimwade#fiona cumming

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#Planet of Fire#Peter Davison#Doctor Who#Penguin Books#Peter Grimwade#Peri Brown#Nicola Bryant#SciFi#Paperback#The Fifth Doctor#vislor turlough

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

turlough's shorts? peri's swimsuit? the doctor's terrible vest?? the master being predictably overdressed? peter grimwade and eric saward said "this serial can be a little bisexual, as a treat"

same appalling vibes as this:

classic who took one look at its cast and said "is anyone going to make them bi?" and didn't even wait for an answer

#planet of fire#watching it now and yep its good#doctor who#classic who#fifth doctor#peri brown#vislor turlough#the master

158 notes

·

View notes

Text

Companions of the time traveling alien known as the Doctor (Doctor 5) arrived in England in 1977 where they met the Brigadier Lethbridge-Stewart and an alien who tried to convince them that he was the new incarnation of the Doctor, but was in reality Mawdryn. ("Mawdryn Undead" Doctor Who vlm 1, TV)

#nerds yearbook#1977#bbc#sci fi tv#dw#doctor who#peter grimwade#peter moffatt#brigadier alistair gordon lethbridge stewart#nicholas courtney#5th doctor#doctor 5#peter davison#mawdryn undead#tegan#janet fielding#nyssa#sarah sutton#vislor turlough#mark strickson#black guardian#valentine dyall#david collings#mawdryn

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Doctor Who: Ranking the Master Stories – Which is the Best?

https://ift.tt/2ZLI4i2

Roger Delgado looms large over the character of the Master, being simultaneously influential and something of an anomaly: Delgado played the role with a debonair front, but since his death, the character has been less urbane and more desperate, manic and violent. In fact the actor who’s come closest to Delgado’s approach is Eric Roberts, who plays an American version of Delgado’s Master until his performance goes big towards the end of 1996’ ‘The TV Movie’.

Each actor brings different facets to the fore, but after the character’s successful launch in Season 8 we get the tricky balancing act of the returning villain: We know that the character returns because they’re popular (indeed, the reason for their existence was the question ‘What can we do to attract viewers for the season opener?’), but in story terms, this makes them seem increasingly ridiculous. The Master, among all Doctor Who villains, seems especially keen to involve the Doctor. Why do they keep coming back if they’re always defeated?

In recent stories, writers have attempted an explanation for the Master’s behaviour, be it an unspecified insanity or a damaged friendship where each party attempts to bring the other round to their way of thinking. Mostly, though, the Master appears in Doctor Who for a simple reason: a lot of viewers find it fun when the Master appears in Doctor Who, and the Master seems to find it fun when the Master appears in Doctor Who too.

Overall the character has a solid record in the show. Fewer classics than the Daleks, fewer duds than the Cybermen, but a lot of solidly entertaining stories mostly lifted by his presence. Here, then, is my ranking of – give or take – every Master story from the television series.

27. Time-Flight

I’m sure there are redemptive readings of ‘Time-Flight’, and its flaws are more understandable in the context of its production (with the money running out at the end of the series and a shopping list of items to include imposed on writer Peter Grimwade), but the end result is poor.

To contrast Anthony Ainley’s performance with Roger Delgado’s for a second: Delgado always played the Master with a calm veneer, as though his nonsensical schemes were perfectly sensible. As a result, he seemed in control. Ainley plays the role as if they’re not merely sensible but clearly brilliant plans even though they strain credulity. They’re smaller in scale and this makes Ainley’s Master seem tragicomic. He loses control more, there’s a kind of ‘She’s turned the weans against us’ desperation that’s much more apparent in this incarnation.

‘Time-Flight’ is, despite its faults, a poor example of this. While the Master disguises himself as a mystic for no clear reason, his end goal is simply freeing himself from prehistoric Earth. Once he’s discarded his disguise, Ainley’s performance is largely underplayed (especially in contrast with ‘Castrovalva’, earlier in the season). While there’s some camp value in the guest cast, it’s not enough to rescue this from being dull.

26. The Timeless Children

The most urgent problem with this story is not the retcon, it’s that it’s simply boring television. The Doctor is passive, trapped in a prison of exposition, and billions of children on Gallifrey are slaughtered because the Master is furious that he’s descended from the Doctor (the former childhood friend whose life is intertwined with his own, indeed who is frequently defined against). This, for me, doesn’t extend logically from what we know of the characters or indeed the situation and turns Doctor Who into a grimdark slog. Not only is it lacklustre, it feels like someone has cyber-converted the show itself.

Sacha Dhawan (saddled with a Master characterisation usually reserved for when they’re clinging on to life in animalistic desperation) brings out the aggressive and violent side of the character to reflect his rage and genocide, is satisfyingly disparaging of the Lone Cyberman, and is working hard to liven things up. There’s not a lot for him to work with, though. This Master is not a dark mirror of the Doctor, he’s just here to do what the plot needs him to. Sometimes that’s what the Master is there for, to be fair, but usually in stories with much lower stakes.

You realise that the Master is only back because the story needed a big villain to destroy Gallifrey and tell the Doctor about the Timeless Child, and it couldn’t be the Cybermen (because of their other function in the series finale) or the Daleks (been there, done that). Based on the character’s interactions with the Time Lords (most obviously Rassilon in ‘The End of Time’ and the chaos he sows in ‘Trial of a Time Lord’, but Borusa was presumably the Master’s teacher too, and uses him in ‘The Five Doctors’), it’s not completely implausible that the Master would resent them, but the reasons shown thus far inadequately explain the character deliberately committing genocide. Whenever the Master’s been reset previously there’s usually been a clear and coherent motivation. In ‘Deadly Assassin’ he’s dying and furious, in ‘Logopolis’ his pettiness unravels him, and in ‘The Sound of Drums’ he wants to be like the Tenth Doctor. Here though, his motivation just poses more questions.

Things could improve. This story is incomplete and – like a Scottish football fan watching their team in Europe – hope lingers that it might be alright in the end.

25. The King’s Demons

After disguising himself reasonably well in ‘Castrovalva’ and ‘Time-Flight’, here the French Knight with the outrageous accent and surname ‘Estram’ is clearly the Master. His goal is to use a shape-shifting android to stop the Magna Carta being signed. The result is less exciting than it sounds. It’s an amiable enough low-key runaround with some good character moments for the regulars, but you’d be forgiven for thinking this was the plateau of the Master’s descent. Ainley, deprived of a Concorde crew to camp things up, gamely takes on that mantle himself.

24. The Trial of a Time Lord

As with ‘Mark of the Rani’, here we find the show using the Ainley incarnation more knowingly. Here he turns up in the thirteenth of fourteen episodes to interrupt the Doctor’s trial. This is something of a relief, because if there’s a consensus on ‘Trial of a Time Lord’ it’s that the trial scenes are interminable. Then the Master arrives on an Eighties screensaver and just turns the whole thing on its head, casually dropping huge revelations that take a minute to sink in. His presence has a galvanising effect, bringing to a head everything that had been stirring thus far in the story. His satisfaction with Gallifrey falling into chaos also ties in nicely to ‘The Five Doctors’ and his later actions in the Time War. The final episode, written in an extremely turbulent situation, doesn’t pay off this thread well (originally the Master was intended to help the Doctor in the Matrix) but that it makes sense at all is impressive given the chaos behind the scenes.

23. Spyfall

The reveal at the end of Part One, in which mild mannered agent O is revealed to be the Master, was exciting on broadcast. It came as a surprise because there’d been so little build up to it, and at the time it seemed extremely unlikely that the Master would come back so soon after their last appearance. In the end, the contrivance that reveals the Master’s presence is indicative of this episode’s larger flaws: as with ‘The Timeless Children’ the character motivations and plotting feel like they’ve been worked backwards from an endpoint. This is not an intrinsically bad way of writing if you have the time and ability to make it work, but here the episode breezes along in the hope you won’t notice the artifice (small things, like the car chase that doesn’t go anywhere, to larger ones like the Master reveal drawing attention to his ludicrously convoluted scheme that involves getting hired and fired by MI6). As it does breeze it isn’t dull, at least, but the promise of Doctor Who doing a spy film with added surprise Master really isn’t fulfilled here.

22. Colony in Space

Possibly the most boring interesting story ever, and one where the Master’s appearance doesn’t lift things. If anything, it implies the Master spends his spare time as a legal official (and to be fair to ‘Spyfall’, it does maintain this tradition of the Master sticking out a day job). Aware that the character’s appearance in every Season 8 story might become predictable, the production team decided he should arrive late in this story. This makes it feel like the Master has simply been added to pad out an underrunning six-parter (and there is a lot of lethargic padding here).

There are some interesting ideas, especially the tension between Doctor Who’s revolutionary side and its conservative one; on the radical side the story clearly sides with the colonists of Uxarieus in the face of the Interplanetary Mining Corporation’s attempts to remove them by force, with initially sympathetic governor Ashe shown to be naïve, while gradually the more active Winton exerts more authority and is proven right when he insists on armed rebellion rather than plodding through legal processes that would inevitably take the IMC’s side (the IMC’s leader, Captain Dent, is a timeless villain – calmly causing and exploiting human misery without qualms).

On the conservative side, this is a story based on British settlers in America and their relationship with the indigenous population. Here we have some British colonists under attack by British intergalactic mining corporations, and throughout everyone refers to the natives of Uxarieus as primitives. It is ultimately revealed that they were once an advanced civilisation, but the Doctor continues using the term. Indeed, he warns the Master that one is about to attack him, knowing the Master will shoot them. This latter example is absolutely in character, and we’ll see in other stories how the Doctor’s blindspot towards the Master is explored in greater detail (indeed, this story also has the Master offering to share his power and use it for good, another thread in a Malcolm Hulke script picked up on later).Considering how padded this story is, though, having no sense of empathy towards or exploration of the Uxarieans’ point of view is a glaring omission.

21. The Time Monster

In many ways ‘The Time Monster’ is crap, with its Very Large performances and a man in a cloth bird costume squawking and flapping gamely. In many ways ‘The Time Monster’ is good, there’s some funny dialogue, great ideas, and a fantastic scene with the Doctor and Master mocking each other in their TARDISes. In many ways ‘The Time Monster’ is hypnotically insane, and you can’t help but admire the way it earnestly presents itself as entirely reasonable; ‘The Time Monster’ straddles the ‘Objectively Crap/Such a hoot’ divide, and is in fact the Master in microcosm with its blend of nonsense, camp, and occasional brutality.

Delgado has now been firmly established as someone who usually lifts a story with his presence, the Master’s routine now a regular and expected part of the programme’s appeal. It’s cosy enough to somehow be endearing despite this clearly being crap on many levels. This is Doctor Who that is extremely comfortable in its own skin; on one hand this involves establishing that the Doctor’s subconscious mind being a source of discomfort for him, and on the other it involves five characters gathering round to laugh at Sergeant Benton’s penis.

20. Castrovalva

‘Castrovalva’ suffers from similar structural problems to ‘Logopolis’, in that the first two episodes are a preamble, and while there’s no lack of good ideas it does feel like the regulars have to go on a long walk to actually arrive in the story. This means we have a lot of good moments (‘Three sir’, ‘With my eyes, no, but in my philosophy’, and the Master being set upon by the Castrovalvans in a nightmarish frieze, as if he’s about to be pulled apart) but there’s little emotional pull as we haven’t spent time with the characters. The idea of people being created by the Master for an elaborate trap and then gaining free will is great, but we’ve only known them for about half an hour so the impact is lessened. The ponderings around ‘if’ in the first half could be better connected with the concepts in the second.

In contrast to the cerebral tone, Ainley is at his hammiest here. Sensing perhaps that the Master improvising an even more elaborate plan than his previous two is stretching credulity, and stuck with Adric and his little pneumatic lift (not a euphemism), Ainley goes big and ends up yelling ‘MY WEB’ while standing like he’s forgotten how to bowl overarm (extremely unlikely given Ainley’s fondness for cricket). He’s also started dressing up again, which is actually done well here but the knowledge of what’s to come makes this foreboding.

‘Castrovalva’ also connects with John Simm’s Master’s misogyny, in that when Nyssa tells him he’s being an idiot he can’t think of a reply so pushes her away, and that he creates a world where the women’s role is to do the cleaning (although that might be partly explained by Christopher Bidmead following ‘Logopolis’ with another world of bearded old science dudes).

19. The Mark of the Rani

In some ways a low point for the Master, but also a relatively good-natured story for Season 22. Here the Master is first seen dressed as a scarecrow, and chuckles at the brilliance of his disguise, as if the Doctor should really expect to find him hiding in a field caked in mud. His plan is to accelerate the industrial revolution so he can use a teched-up Earth as a powerbase.

It’s not that this Master lacks ambition, it’s just that his plans all feel like first drafts. He also plays second fiddle to the title character, with the Rani clearly put out that he’s there at all. Ainley, who regarded a few of his scripts as less than impressive, wasn’t happy at being demoted, but this works for the character. This pettiness is part of the Master now, and so ‘Mark of the Rani’ can be celebrated for finding a tone and a role that makes sense for him, something that invites the audience to indulge him rather than take him too seriously.

Read more

TV

Doctor Who: Ranking Every Single Companion Departure

By Andrew Blair

TV

Doctor Who: Ranking the Dalek Stories – Which is the Best?

By Andrew Blair

18. The Mind of Evil

The Master is cemented here as an entertaining nonsense. He has a multi-phase plan to start World War III which involves converting a peace conference delegate into the avatar of an alien parasite which has been installed in A Clockwork Orange–style machine in a prison, after which he will take over the planet. Delgado, as ever, plays this as if it’s perfectly straightforward. As with his debut story the Master bites off more than he can chew in his allegiances, and you get the impression he’s not totally serious about global domination and just wants to hang out with the Doctor. Pertwee is at his peak here, rude and abrasive, righteous and enjoyably sarcastic, but also put through the wringer by the Keller Machine (which the Master has apparently invented using the alien parasite).

For all the good work ‘The Mind of Evil’ does with the Doctor and the Master (the idea that the Master’s greatest fear is the Doctor laughing at him ultimately comes to define the character), and with this being a mostly well-made story, it does devolve into an action-orientated (I say ‘devolve’, your mileage may vary) story where the Keller machine is now lethal and capable of teleporting, combined with a Bond movie plot where UNIT find themselves transporting a missile and guarding a peace conference (far from their stated goal of dealing with the odd and unexplained).

There’s a satisfying clash between the horror of the Keller Machine and the sight of prison guards shooting and screaming at what looks like a Nespresso prototype sitting on the floor. This is a good tonal summary of ‘The Mind of Evil’ – a lot of grimness (horrible deaths and genuinely nasty characters) rubbing up against something enjoyably silly.

17. The End of Time

As with ‘The TV Movie’ here the Master get some new and largely inexplicable powers, suddenly craving food and flesh. What John Simm’s stories add is the idea that the Master was driven mad by the constant sound of drums. Here it is revealed that the Time Lords planted it in the eight-year-old Master’s head as a means of escaping the Time War. As with The Timeless Child reveal, this Chosen One storyline lessens the characters for some viewers, limiting the character’s free will and making them less interesting. Russell T. Davies is smarter than that here though.

What works well are the references to the Doctor and Master’s childhood, the brief suggestion that that Master would like to travel with the Doctor without the drumming, the Master and Doctor choosing to save each other and return the Time Lords to their war; the Master rejecting his appointed role of saviour, refusing to have his entire life disrupted. Including the Master here is a good move beyond hype, offering a warped reflection of the departing hero (the fact that the Master’s big plan is grounded in vanity is telling).

It’s a strange mix, because there are clearly great scenes in this story, but the dominant impression of the Master is now being able to fly, shoot lasers from his hands, and occasionally have his flesh go see-through. The latter feels like a call-back to his emaciated state in ‘The Deadly Assassin’ but lacks the physicality.

It feels not dissimilar to ‘Twice Upon a Time’, in that it contains parts of what made the showrunner’s work so good, as well as being a clear sign that it was time to move on.

16. Logopolis

Maybe it’s because I didn’t have the context of its original broadcast, that sense of a Titan of my childhood finally saying goodbye, but – besides a memory of finding the opening episode unnerving on VHS – I have no real sense of this story from a child’s point-of-view. As it is, I can appreciate the ideas in it – a planet of spoken maths that can influence reality (riffing on Clarke’s Third Law), the sense of the Fourth Doctor’s regeneration being inevitable, the scale of the threat involved and that it results from the Master’s attempts at petty revenge rather than a deliberate plan – but I can’t honestly say they’re woven into compelling drama.

I have few objections to silliness in Doctor Who, but I find it hard to get on board with something so ludicrous that thinks it’s incredibly serious.

There are the recursive TARDISes that stop because the Doctor has to go outside for the cliff-hanger, Tegan spending her first story as someone with a child-like fixation on planes, the exciting drama of Adric and the Monitor checking an Excel sheet for errors, and the stunning scene where the Doctor explains that the Master knew he was going to measure a police box by the Barnet bypass because ‘He’s a Time Lord: in many ways we have the same mind’ immediately followed by the Doctor’s idea to get the Master out of his TARDIS by materialising underwater and opening the door. This story thinks itself clever, but judders forward through a series of nonsensical contrivances before cramming the actual story into two episodes.

The first half is stylish nonsense, building up to the reveal of the Master chuckling to himself about ‘cutting the Doctor down to size’ – it’s then you realise that everything he did in the first two episodes was for the sake of a joke that only he can hear, and this pun kills several trillion people. To be fair, this is a brilliant idea, it’s just a shame about the slog to get to this point. The final confrontation is then less ‘Reichenbach Falls’ and more ‘Argument at a Maplin’.

The Master is well played by Antony Ainley in his full debut, and as a child his mocking laughter was genuinely unsettling. As reality unravels, so does he. If he’d killed trillions deliberately, and they knew of his power before dying, he’d be fine, but doing it by mistake without people knowing seems to break him. Mostly there’s the feeling of lost momentum with the character, going from a powerful symbol of evil that corrupted paradise to a man broken by his own banter.

As with Nyssa witnessing the death of her planet, there’s a lot of potential for character drama here that the show wasn’t interested in exploring at the time.

15. The TV Movie

As written, the Master here is a devious, manipulative creature who is willing to destroy an entire planet just to survive. This is extremely solid characterisation, matching what’s gone before. You can also hear Delgado delivering this dialogue (though I’m not sure how he’d respond to ‘you’re also a CGI snake who can shoot multi-purpose venom’).

The shorthand for this Master is Eric Roberts’ big performance in the finale, which does tend to blot out the rest of his acting. Full of smarm and charm, Roberts is mostly downplaying his lines as an American version of Delgado (indeed his costume for the ‘dress for the occasion’ scene was going to be like Delgado’s Nehru jacket), and his line delivery obscures the fact that the final confrontation scene is very well written up until Chang Lee’s death. It’s quite a good summary of the character so far: cunning, persuasive, visually monstrous, driven by survival, then ultimately camp and desperate.

While the Master and Doctor’s rebirths are very well shot, the movie would have worked better without regeneration so we could get more screentime with the new cast, and the final confrontation is the only time the Doctor and Master get to actually talk, which means we only get a broad brushstrokes version of their relationship. Nonetheless the ‘What do you know of last chances?’ ‘More than you’ exchange is fantastic.

14. The Claws of Axos

Bob Baker and Dave Martin’s debut script for the show is busy and full of nightmare-fuel for the viewer, with the Master (who wasn’t in earlier drafts) put into uneasy alliances with UNIT and the Doctor. Briefly he fulfils the role of UNIT’s Chief Scientific Advisor, which is inspired, showing through his interactions with the Brigadier how alike he and the Doctor are.

The first story in which the Master is just grifting and trying to survive rather than being halfway through a devious plan. ‘The Claws of Axos’ wisely tries something different with the Master in the midst of an enjoyably garish romp (Doctor Who will never have this colour palette ever again). There’s some effective body horror, tinges of psychedelia, and a hokey American accent.

It’s all over the place this one, but barrels along with glee and feels like the Pertwee era has relaxed into a lighter mood, albeit one where people are still electrocuted and turned into orange beansprout monsters.

13. Terror of the Autons

We are immediately told that the Master is dangerous, but also not to take him too seriously: one of the first things he does in Doctor Who is kidnap a circus in order to raid a museum.

And so the rest of the story proves: a darkly comic (and famously terrifying) blast which sets out the character of the Master for the rest of the Pertwee era: the delicate balance between the ridiculous and the vicious. Delgado isn’t quite there yet in this story, not fully realising the comic potential in the character and playing things straighter than he would later. One thing he lands immediately is acting as if the Master’s plans are perfectly sensible, bridging the gap between animating murderous chairs/phone cables and suffocating people with plastic daffodils, so that they die uncomprehendingly as they claw at their face.

Therein lies the appeal of Doctor Who, with one of its central tensions being between the mundane and the ridiculous, the cosy and the suffocating. This is exemplified here by a plastic doll coming to life and trying to kill everyone because Captain Yates wanted to make some cocoa.

12. The Dæmons

In which the Master is good-humoured and ostensibly pleasant while trying to summon a demonic alien being, accompanied by a moving stone gargoyle who can vaporise people. The show is well aware of the Master’s impact, to the extent that one of the cliff-hangers features him in danger rather than the Doctor or UNIT.

What his debut season has established is that the Master himself is mostly fun (indeed, often more fun than the Doctor), but the monsters that he brings with him are terrifying. This is true from his first story, in which he brings a barrage of nightmarish ideas to life. Bok, the aforementioned gargoyle in this story, absolutely terrified me as a child. Most of the accompanying monsters in the Pertwee era did, but by tapping into the paranormal and demonic this story has an extra frisson of fear.

I have nothing new to say about ‘The Dæmons’: it’s the first Doctor Who story to mine the works of Erich van Daniken and it does it well, the Doctor is a dick in it, the resolution with Jo’s self-sacrifice is weak, it’s an episode too long, but also it’s got Nick Courtney effortlessly winning every scene he’s in, which helps a lot.

11. The Five Doctors

This is a story that plays to Ainley’s strengths, and he delivers. No other Master is as good at looking pleased with themselves, so when the Master is having a mission pitched to him by the High Council of Time Lords Ainley’s face is priceless. He’s present, and enjoying himself immensely, disdainful of the upper echelons of the society he escaped.

Then, when he attempts to persuade the Doctors that he’s there to help, the fact they all immediately assume he’s trying to trick them makes him entertainingly frustrated. Terrance Dicks’ script plays to the former friendship between the two characters, and the Master feels more like his old self before the Brigadier dispatches him with a cathartic biff. His brief alliance with and inevitable betrayal of the Cybermen is something you can imagine Delgado delivering, while also highlighting the difference in the two incarnations. Delgado would say ‘Your loyal servant’ with confidence, and find the ‘driving sheep across minefields’ line drily amusing. Ainley feels venal and nasty in these scenes, more like a childhood bully trying not to get hit. That he ultimately does is a lovely pay-off.

10. The Sea Devils

A somewhat padded Pertwee six-parter? With much of the padding being fight scenes with lots of guns and stuntmen flipping everywhere? With the Doctor being rude to everyone? And a meddling Civil Servant, Jo being plucky and resourceful, and the Master allying himself with a group that betrays him? With Malcolm ‘Mac’ ‘Incredible’ Hulke subtly undermining the entire thing? It’s like coming back to your old local and finding nothing has changed while you understand it better than ever.

Trenchard, in charge of the Master’s prison, is a relic of Empire and friends with Captain Hart – the highest ranking Naval officer we meet – who is clearly sad when he is killed. this story may have been made with the co-operation of the Navy but Hulke implies an old boys’ club which the Doctor breezes into and disrupts (but he is no longer averse to the military’s involvement as he was in ‘The Silurians’- it’s not clear whether it’s his relationship with UNIT or the Master that has changed his mind here – is he now used to having military support or does he deem it necessary due to the Master’s presence?).

Hulke, being one of the better writers of character the show had at this point, draws out his characters extremely well and deepens the Doctor and Master’s relationship by mentioning their past in more detail (a lot of what Steven Moffat developed in Series 8 – 10 was inspired by Hulke). Delgado briefly departs from the cosiness of this story by snapping in rage at a guard he’s attacking, letting the affable façade drop just for a second to show the fury beneath it all. It’s a small moment, but it’s something that will be built on for many years to come.

Read more

TV

Doctor Who: Ranking the Cybermen Stories – Which is the Best?

By Andrew Blair

TV

Doctor Who’s Weeping Angels Are Perfect Horror Monsters But Are They Returning Villains?

By Zoe Kaiser

9. Frontier in Space

In some ways, this is just a ridiculously long pre-credits sequence for ‘Planet of the Daleks’, but there’s just something incredibly endearing about Doctor Who attempting a space opera, complete with hyperdrives and space walks. The genius move is giving it to Malcolm Hulke, who fleshes out his characters more than most and manages to use genre cliches to achieve this. There’s a great gag where the Doctor tries to convince the Earth authorities that a war with the Draconians is being engineered, only to be captured by the Draconians who put him through the exact same rigmarole.

This is also Roger Delgado’s final story before his tragic death, and he arrives delightfully, walking into Jo’s prison cell and saying ‘Let me take you away from all this’. He’s also, after ‘Colony in Space’, taken another day job, this time as a commissioner from Sirius IV. Hulke is clearly determined to explain what the character gets up to on his days off, and the repetition both underlines how static the character has been (especially in contrast to Jo Grant) but also functions as something of a last hurrah.

The dialogue is absolutely superb throughout, which is ideal because not a lot actually happens in this story. However it doesn’t really matter because Jo, the Doctor and the Master are so established that it’s great fun watching them all riff off each other, with Jo resisting the Master’s hypnotism and going on a weary semi-ironic monologue about her day-to-day life at UNIT, the Doctor having a whale of time with political prisoners, and the Master dropping bon mots left, right and centre. There’s a lot of great lines here, so I don’t really mind the repeated capture/escape/capture padding because everyone’s having such fun that it’s just a joy spending time with them.

8. The Magician’s Apprentice / The Witch’s Familiar

Opening a series with a character piece semi-sequel to a 1975 story shouldn’t work this well, however there’s definitely a sense of offering up shiny things to distract us from setting up other stories. The ending also happens in something of a rush. Nonetheless, I’m a big fan.

This story is interesting in terms of how inward looking it is. All the components involved have been established since 2005 and are explained in-story, but it’s still a demand that can limit the audience. So while I like this story, it does rather confirm that ultimately, making Doctor Who that’s right up my street isn’t a valid long-term strategy. However, if you are going to do a story steeped in lore, this is a good way of doing it: using the past as a foundation rather than trying to recreate it. Here Steven Moffat builds a lot: the Twelfth Doctor’s character softens based on his past few stories, Missy and Davros return and their relationships with the Doctor are explored, the actual experience of being a Dalek is expanded on (Rob Shearman’s ‘Dalek’ novelisation goes further if you’re into that), and the Hybrid arc is set up.

Previously in a ‘Ranking the Dalek Stories’ article I mentioned how ‘Into the Dalek’ felt like a story needed to establish that series’ themes, and didn’t do enough to integrate this with a good Dalek story. Here, though, the themes are woven more subtly in the episodes and less so in their titles. They’re also more interesting ones than ‘Fellas, is it bad to hate genocidal cyborgs?’

In the swirl of character building we have Missy essentially being the Doctor, exploring Skaro with her companion. Clara takes this role and has a terrible time as a result. As with the Doctor’s conversation with Davros, this highlights uncomfortable similarities: yes, Clara is literally pushed into danger while Missy has a secret plan for her, but it’s not like the Doctor hasn’t done similar over the years.

7. Planet of Fire

Considering all the tasks it has to do (introduce a new companion, write out two existing companions, using Lanzarote for location filming, and provide a potential exit for Anthony Ainley’s Master), ‘Planet of Fire’ is ultimately rather impressive. It suffers from an uneventful first episode (roughly 80% setup and 20% dodgy American accents), but once the Master arrives it livens up considerably.

With the Master controlling Kamelion, a shape-shifting android, remotely Ainley gives different performances for the actual Master and the Kamelion-Master, the latter more controlled. He’s also having fun here (his little smile after Peri responds to ‘I am the Master’ with ‘So what?’ is great) The Kamelion-Master, in a black suit and shirt combo (which suits him better than his usual outfit), seems more pragmatic and violent. It actually works for Ainley’s Master to be less threatening than a robot version of himself. Bent on survival, this Master has a better motivation than usual and the writing is layered: when he realises he’s in trouble in the final episode he switches instantly to pleading for his life and futile rage as the Doctor stares, either unable or unwilling to help him. There are emotional beats like this throughout the story which makes it fit well with post-2005 Doctor Who.

The rest of ‘Planet of Fire’ – as with writer Peter Grimwade’s previous script ‘Mawdryn Undead’ – has a knack for character lacking in many Fifth Doctor stories. As well as being a strong outing for the Master he writes Turlough out well and introduces Peri as a flawed but brave companion who clearly had a lot of potential. These arcs all intersect with each other, as well as the religious fundamentalism story (watered down in development), producing clear emotional journeys and an underrated gem.

6. Utopia / The Sound of Drums / Last of the Time Lords

Delgado’s Master was very specifically an inversion of Jon Pertwee’s Doctor: both of them were geniuses, one was grumpy and rude and the other suave and funny. The rude one tended to save the Earth, the funny one tried to subjugate or destroy it. John Simm’s Master isn’t an inversion of David Tennant’s Doctor so much as a warped reflection – they’re both quick-talking, charismatic and alluring figures, but while this Doctor is dangerous because he doesn’t notice the power he has over people, this Master is dangerous because he absolutely does.

It’s worth noting on the character’s reintroduction that Russell T. Davies dispensed with the kind of low-key plan that is clearly doomed to failure from the start, and instead showed the full realisation of the Master getting what he wanted coupled with the most cartoonish version of the character we’d seen: Simm went bigger than Tennant, and as Ten is a dangerous enough figure already it made sense to exaggerate this. While some fans wanted another Delgado, we got someone building on Ainley and Roberts’ over-the-topness while still feeling in control of his plans.

The character’s return was also tremendously exciting on broadcast. The impact that ‘Utopia’ had especially was huge, and Derek Jacobi left fans wanting more after his brief appearance as the Master (Hey, Big Finish Twitter person: here’s your angle if you want to retweet this). After the endearingly dated urban thriller stylings of the middle episode, ‘Last of the Time Lords’ is a really bleak episode that doesn’t quite stick the landing: the idea behind the floating Doctor offering forgiveness rather than vengeance is good, although I’m not sure it’s realised as well as it could be, and there’s an extra fight scene that adds nothing and loses momentum. The Simm Master is kept at a distance from the Tenth Doctor too, mostly speaking through phone or radio. The aged and shrunken Doctor is a misstep in terms of limiting their interactions, though the phone call we do get includes some fun nods to slash fic.

5. Survival

Rona Munro writes Ace and people her age with more verisimilitude than the surrounding stories, and she brings that same level of characterisation to the Master. Here he’s struggling against the animalistic power of a planet and plotting to escape. Ainley commits to the savagery and relishes the opportunities to be nasty.

What’s especially well written here is that this is still clearly the Master of ‘Time-Flight’, ‘The King’s Demons’ and ‘The Mark of the Rani’ – yes, he’s desperately trying to survive here and that shows him as more threatening than usual, but what’s equally important is when he says ‘It nearly beat me. Such a simple brutal power’, and then immediately takes the Doctor back to the planet, now engulfed in flames, and tries to kill him. It has beaten him. He’s lost to it. He even refuses to escape (‘We can’t go, not this time’) and is ready to die. This is the last we’ll see of Ainley in the role on TV (his last performance in the role, from a mid-Nineties computer game, can be found on this story’s DVD extras), going out with the acknowledgement that this Master is a tragic figure, he’s out of silly plans and costumes, now all that he has left is the violence that was latent within him – previously seen in…

4. The Deadly Assassin

Writer Robert Holmes hadn’t written for the Master since the character’s first story, and since then the character’s sadism had been downplayed. Here, after the death of Roger Delgado, Holmes elected to dispense with Delgado’s calm and suave persona, with the Master now a Grim-Reaper-like figure, still hypnotic but now without any pretence of reason: a creature of pure spite. That moment of jarring rage from ‘The Sea Devils’? That’s on the surface now. This, combined with his design for life, makes his plan seem more vicious than usual: simply to survive he will set off a chain of events that will destroy Gallifrey and hundreds of other planets. We’ve gone from the warped friendship of Delgado and Pertwee’s characters to explicitly stated hatred here.

The story does feature Holmes’ main weakness, in that after the fantastic world building, dialogue and horror, it all ends rather swiftly with the Doctor physically dominating the villain. What we do get here, though, is an almost casual rewriting of the lore of the series in a gripping and atypical story (that some fans hated at the time), and the successful recasting of the Master. What’s more, the character can now be revisited as this nightmarish figure or as another more Delgado-like figure, his scope has widened. What no one was expecting, though, was bringing the Master back as an almost primal force.

3. The Keeper of Traken

I know what you’re thinking. Putting this story ahead of ‘The Deadly Assassin’ is madness. Well, that’s subjective opinions for you. I think it’s fair to say that ‘The Deadly Assassin’ is a more solidly realised production than ‘The Keeper of Traken’, but I prefer the ideas in the latter and so it’s slightly ahead for me (and the ideas are still well realised).

We’ve seen from his debut onwards that the Master arrives in a location or organisation and brings it under his influence (the village in ‘The Dæmons’, the Matrix in ‘The Deadly Assassin’), but here we see him corrupt an entire civilisation. What’s more, it’s a fairy tale of a place, reputedly somewhere ‘evil just shrivelled up and died’ (to which the Doctor adds enigmatically ‘Maybe that’s why I never went there’).

I’m not 100% behind the more mythic versions of the Master (such as Joe Lidster’s Big Finish play ‘Master’, which is a great piece of work in itself but not one I keep in my headcanon). This could be one of them, with the Master a being of such purest evil that he infects and destroys the fairy tale kingdom.

Instead Johnny Byrne’s story shows Traken with a fairy tale’s darkness and decay, begging the the question of how much of Traken’s fall is down to the Master and how much of it is due to their own complacency (Traken’s Consuls are old and bickering. The youngest is clearly an idiot. They seem distant from their people). It seems the Master’s arrival exacerbates the collapse rather than causes it. This level of power likely comes from the original script without the Master, the character fulfilling a role created for something new, but it still fits with the ‘Deadly Assassin’ version who plays long games motivated purely by survival and spite.

And he capitalises on a very human fear, that of Kassia not wanting her new husband Tremas to take over as the titular keeper so that she will barely see him again. The main weak point of this story is that Doctor Who was not in a position to really commit to the heart-breaking ideas in this story (technobabble yes, but not as much pathos as there should be), especially the Master’s abrupt takeover of Tremas’ body.

As a child I found the final possession scene underwhelming, but the bit where the Master takes control of the Doctor is chilling. You understood that something extremely serious was happening. Tom Baker, it must be said, is exceptional here, especially when he shames Tremas (who doesn’t seem too fussed by the possession of his new wife) into helping him.

This story has a rich setup with good motivations for drama, and balances this with a more mythic quality. This is a significant development for the character, to become an evil so pervasive it manifests as rapid societal decay. Fortunately if there are two things Doctor Who fans are good at dealing with, it’s symbolism in storytelling and change.

2. Dark Water / Death in Heaven

Missy is something of a patchwork creation by necessity. In some respects she’s an evolution of John Simm’s Master, a manic figure concocting season finale-scale schemes and building on the Tenth Doctor’s frustration that they aren’t friends. She also evokes Peter Pratt’s Master in terms of sadism, killing a fair few of the guest cast, including some unexpected ones (and for a while it looks like she’s killed Kate Lethbridge-Stewart). She’s also reminiscent of Delgado, not necessarily in Michelle Gomez’ performance but in the sense that she’s largely in control and is written and cast as an inversion of the Doctor (Capaldi is irascible, seemingly heartless and mostly contained, whereas Gomez buzzes with childlike energy and revels in cruelty). From here, Moffat starts building towards the ends of Series 9 and 10.

Two things separate Missy from other incarnations: firstly there’s Michelle Gomez, a unique performer who varies the size of her performance in interesting ways, and secondly there’s explicit vocalisation of past suggestions that the Master does what they do as a warped gesture of friendship. This makes the character suddenly and deliberately tragic and strangely relatable: we’ve all been in difficult relationships where we try to get someone else’s attention, but none of us have been driven to an unspecified insanity by virtue of a constant drumming sound implanted by the resurrected founder of our entire society. As an explanation for all of the Master’s behaviour it’s rather neat, while also trying something different with the season finale: the grand plan isn’t to conquer the world (as with ‘Logopolis’ a colossal death toll is a side effect).

It’s Moffat’s grimmest finale – atypically no happy ending here – but if it hadn’t worked then there wouldn’t have been such solid foundations for what followed.

1. World Enough and Time / The Doctor Falls

Series 10 is arguably one long Master story, as Series 1 is one long Dalek story, which is not only true but also a handy excuse for not wanting to watch ‘The Lie of the Land’. Missy’s story is initially told around the edges of the episodes, and as a result these short scenes are to the point and occasionally clunky while laying foundations for the finale. Fortunately the finale is superb.

We are shown the relationship between the Doctor and the Master as a tragedy spanning millennia: ‘She’s the only person that I’ve ever met who’s even remotely like me’, and so the Doctor’s hope that the Master can be the friend he remembers trumps Bill’s fears. And Bill is shot. It harks right back to the Doctor remarking – after all the death and carnage in ‘Terror of the Autons’ – that’s he’s rather looking forward to their rivalry. The Doctor has a blind spot where the Master is concerned, and it kills people.

It’s impossible to say how well the John Simm reveal would have worked if his presence hadn’t already been announced, but nonetheless he does great work as both Razor and a Master who represents pretty much all other incarnations except Delgado (not unlike the War Doctor standing in for all the original run’s Doctors in ‘The Day of the Doctor’). Steven Moffat builds on the way Simm’s Master delights in pure nastiness but continues to be cruel when there’s no joy in it for him. His is a Master abandoned by his people and his friend, very much feeling it is him against the universe.

In contrast, Moffat had been re-establishing the sense of friendship present between Delgado and Pertwee’s characters with Missy and 12. Delgado’s planned final story was planned to reveal the Doctor and the Master as two aspects of the same person, with the Master ultimately dying in an explosion that saved the Doctor’s life (with it remaining ambiguous whether this was a deliberate sacrifice). It feels like Moffat took inspiration from this, with the resulting story of a broken friendship and the cost of restoring it: Bill’s conversion to a Cyberman, the Doctor’s words – for once – cutting through to the Master, who tries and fails to escape her past. Part of her would rather die than be friends with the Doctor (as Simm’s Master also did in Series 3).

It’s spoilt slightly by Simm commenting that this is their perfect ending, which feels like it’s obvious without being spelled out, but on the other hand he does have a point. If you were going to kill off the Master, it’s hard to see past this as their ideal conclusion.

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ playerId: "106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530", }).render("0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796"); });

Read more Doctor Who ranking articles here.

The post Doctor Who: Ranking the Master Stories – Which is the Best? appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/2X0NCHN

1 note

·

View note

Text

Watch Classic Doctor Who on Pluto TV Completely Free Now!

Watch Classic #DoctorWho on Pluto TV Completely Free Now!

US fans now have a new way to enjoy Doctor Who’s classic era. Pluto TV, which is a free streaming channel stateside, has set up a dedicated pop-up channel purely to screen 200 episodes of the original run. This channel is the result of a licensing deal between BBC Studios and Viacom and is a great place to start if you’re a NuWhofan looking for a way into the series as it was 1963- 89 or if…

View On WordPress

#Agatha Christie#Beryl Reid#Chris Boucher#Daleks’ Invasion Earth 2150 A.D.#Earthshock#Eric Saward#Leela#Peter Grimwade#Pluto TV#Robert Holmes#Terror of the Autons#The Ark in Space#The Caves of Androzani#The Dalek Invasion of Earth

0 notes

Text

February 2024

Happy Leap Day!

Read for February:

All The Hidden Paths by Foz Meadows

Doctor Who Planet of Fire by Peter Grimwade

0 notes

Text

‘The whole world was reducing to an image from a half-forgotten dream.’

#DW#DoctorWho#Books#TargetBooks#ScienceFiction#Fantasy#BookReview#VintageBooks#Classics#TARDIS#TimeFlight#FifthDoctor#Celery#TheMaster

0 notes

Photo

157. EARTHSHOCK

As the Earth prepares to host an intergalactic peace conference, a bomb is discovered deep underground, guarded by silent androids and surrounded by the bones of long-dead dinosaurs.

Image from http://tragicalhistorytour.com/ .

#earthshock#days of the doctor#doctor who#fifth doctor#adric#nyssa#tegan jovanka#eric saward#peter grimwade

1 note

·

View note

Text

DOCTOR WHO: EARTHSHOCK

Revenons un instant sur l’ère Peter Davison avec l’épatant ”Earthshock”, serial en quatre parties diffusé entre le 8 et le 16 mars 1982.

Marquant le retour des Cybermen (après sept ans d’absence) et le départ d’Adric (Matthew Waterhouse, compagnon du précédent Docteur et copieusement détesté par le public), cette storyline, se passant au XXVIème siècle, voit l’équipage du TARDIS venir en aide…

View On WordPress

0 notes