#paul rotha

Quote

There lies a major, perhaps even a sufficient, reason, for the strange curse lying on our documentarists' ventures into fiction. Roy Boulting, Anthony Asquith and Carol Reed had made fictions films before turning to the wartime documentary, and quit documentary as soon, it seems, as they could. Ian Dalrymple, executive producer at the Crown Film Unit during the war years, had previously worked with Korda; he makes the bravest attempt at applying the documentary spirit of responsibility to post-war problems. John Grierson, while executive producer of Group 3 (1950-55), offered mainly sub-Ealing comedies so timid as to be positively ingratiating, and Group 3's best movies with their modest virtues break no new ground. Paul Rotha's one memorable feature, No Resting Place (1950) brings a sharply neo-realistic tone to the romantic shroud which usually envelopes Gaelic peasants. Among B features of limited resources his The Life of Adolf Hitler shockedly informs us that Horst Wessel was a homosexual. So what? What does that prove about Nazism? Given this moralising, this rhetoric, it's obvious why the film is so incoherent in its social perspectives.

Raymond Durgnat, A Mirror for England

#raymond durgnat#a mirror for england: british movies from austerity to affluence#roy boulting#anthony asquith#carol reed#ian dalrymple#john grierson#paul rotha#bernardo bertolucci

1 note

·

View note

Text

He's Psychotic | Feyd-Rautha

fandom: Dune: Part Two (2024)

pairing: feyd-rautha harkonnen x irulan corrino

description: He’s psychotic, Irulan was sure of it. And she was about to marry him.

word count: 4k

warnings!: smut, wedding night, loss of virginity, rough sex, knifeplay 🔪, bloodplay🩸, where's my wife?, who did this to you?, concubines, blood and injury, praise kink, marriage.

He was psychotic, Irulan was sure of it. An animal, a beast, a sort of soulless creature no living woman could bear to stand.

And Irulan was about to marry him.

This wasn’t the plan, of course. She was supposed to marry Paul Atreides, Duke of Arrakis, but fate had different plans. Her fate took an unexpected turn the moment Paul’s lifeless body fell to the floor, with his enemy’s blade deep in his guts. In that moment, Feyd-Rotha’s black eyes bore into her and the smile of his was just as black.

Her father said, “You’ve won. What would you like in return for this victory?”

She shuddered, unable to take her eyes off the man before her as he walked back to Paul’s body, ripped out the blade from it and pointed the sharp tip towards her, the blood still dripping from it—drip, drip, drip.

“Had the Duke won, he would’ve gotten the princess. Now, as the victor, I have the right to her. I want your daughter.”

Her father didn’t oppose. Perhaps he wanted to but had nothing else to offer. Alas, Irulan was the thing he could give, in his mind, he had already given her up to Paul Atreides.

And so, three days later, she was dressed in traditional bridal garments: the ivory dress of the finest silk, a modest scoop neckline adorned with beading, with long fitted sleeves cascading down her arms with sheer panels, the skirt flowing out from the waist in a graceful line. To finish off, she wore a dramatic veil that framed her entire form and was held up by an ornate headpiece.

She was to be sacrificed to a demon.

Irulan walked down the isle, surrounded by a flood of the same harkonnean faces, all of them bald and pale and muscular, neither of them familiar, only one, at the very end, waiting for her, watching her every step, even the slightest movement of flesh underneath her garments – Feyd-Rautha’s eyes on her were like a hawk’s. She shuddered.

The road to her future husband in this hall at Giedi Prime. She walked, and walked, alone and exposed, and it seemed that the distance between him and her remained the same. But no, she was getting closer, because now she could see him better. His robes were of tight shiny leather with silver lining, they clung to his body like a glove. He stood tall and regal, a neutral expression on his face. Except for his eyes, of course. He held his hands in front of himself as if he was imprisoning his own body in one spot, as if he was trying to stop himself from eating away at the distance between them himself, as if he had to keep his hands from reaching out for her.

Irulan finally stood in front of him and, while the Reverend Mother spoke words of matrimony she couldn’t understand (she could understand the language, undoubtedly, only in that moment she wasn’t capable of understanding the meaning behind them), she watched Feyd-Rautha in all his glory. His dark gaze demanded attention. The only comfort was the veil that covered her face from him.

Sometime in the middle of the ceremony, Irulan heard a strange hissing sound. She turned her head very slightly to see three women standing behind her soon-to-be husband. All three of them looked the same—bald heads, black eyes, blackened teeth and pure hatred, addressed to her—different only in height. It took a few moments for Irulan’s frightened mind to realize that these were Feyd-Rautha’s concubines who were hissing at her. No one else, besides Irulan, paid them any attention, so she learned to ignore the hissing too.

However, Irulan was so focused on the concubines, she didn’t understand that the Reverend Mother spoke the last words of the matrimonial ceremony until Feyd-Rautha lifted his hands and unveiled her. She flinched, caught off guard, feeling small and vulnerable before him. His face moved closer to hers very slowly, as if he didn’t want to frighten her. The initial moment of his kiss felt like a butterfly’s touch to her lips—soft, tender, barely there. When her mouth opened to him in surprise, he explored it with his tongue, and the kiss soon turned passionate, wild all-consuming. It lasted far longer than a dutiful wedding kiss should’ve lasted and it left Irulan breathless once it ended.

She stared at his lips, now red from the kiss, even more so in contrast with his paper-white skin. His breathing was just as heavy as hers, their chests heaving in tandem, but he soon regained his wits, reaching out his hand for her, which she wasn’t cautious enough not to take.

He started walking her out of the hall and down the dark empty corridors, leaving the Harkonnens and the rest of Giedi Prime behind them. He led her to a spacious minimally furnished room but she could tell every single item there must’ve cost a fortune.

Feyd-Rautha let go of her hand only when she was standing in front of a canopy bed. Then he disappeared from her sight, and she was too nervous to turn around. He’s psychotic, she had to remind herself. One wrong move and he might attack like an animal.

She felt her headpiece being lifted from her head together with the veil. She saw his pale hands put it aside carefully. She turned her head slightly only to see he had taken off his top garments, and she saw his naked chest, tattooed with thick black lines. He watched her face as she peered into his nether region, then grabbed her chin between his thumb and forefinger, forcing her to look at him.

“Are you scared of me, princess?” he asked.

Irulan looked into his eyes, searching for madness there, or for empathy. She found neither.

Swallowing thickly, she held his gaze.

“No.”

She couldn’t let him know how frightened she truly was.

Feyd-Rautha’s and moved to the back of his bottoms and he took out a knife, ornate and beautiful, like a piece of art. Irulan’s eyes widened in fear, her body shivered violently outside of her control. Her reaction put a smile on his face. As Feyd-Rautha moved his knife to the fabric of her dress, she closed her eyes, daring herself to get through whatever pain he was about to inflict on her. Most importantly, she couldn’t show panic.

She scrunched her nose, waiting to get stabbed, waiting for the blade to pierce her skin, then dig into her flesh, she waited for him to draw her blood, make her scream—until she heard fabric ripping in half. Irulan opened her eyes, drawing in a lungful of air like a man lost in dessert, breathing in oxygen for the first time. she felt the dress fall of her body before she saw her own nakedness, blushing from shame. She noticed Feyd-Rautha’s eyes on her even if she didn’t see him, she felt his hot breath on her exposed skin. Her nerves were akin to violin strings—tout and resonant—as he stood behind her like a looming threat.

As Irulan tried to calm her respiration, Feyd-Rautha’s fingers dug into her scalp, kneading at her hair and messing up the fancy braids that formed a bun, until her hair was freed, falling down her back in waves. She felt his fingers brush through her locks—once, twice—and then, to Irulan’s grave horror, he brought the knife to her neck, his other arm holding her down by her waist, pulling her bottom into his groin. She gasped at the cold sharp blade on her delicate skin there.

“Still not scared, princess?” he spoke lavishly into her ear.

This was a trick. He wanted a reaction out of her. But he wasn’t going to truly hurt her, otherwise he would’ve done so already. She wouldn’t let him trick her.

“No,” she repeated, although a slight tremor in her voice betrayed the truth.

He pulled the blade away from her, grabbing her by the throat with his other hand. His lips touched her jaw tenderly and she closed her eyes at the feeling.

“Good girl,” he whispered.

His hands guided her to get on the bed, slowly and barely pushing her as she complied. She lied on the bed on her back, feeling her hair fall around her like the sun. Feyd-Rautha’s widened eyes roamed over her body possessively, taking their time to appreciate the curve of her neck, her shoulders, her round breasts, her flat belly, until they landed on her apex. His gaze was hungry, wild, untamed, which she took as a compliment.

Still holding the knife in one hand, he unbuttoned his bottoms with the other and took them off. His cock caught Irulan’s attention immediately—long, thick, and veiny, monstrous just like its’ owner. Seeing where her gaze had landed, Feyd-Rautha smirked, kneeling on the bed as she moved away to give him space, but he grabbed her thighs, pulling her close. He spread her thighs, putting her ankles onto his shoulders, his black gaze boring into her sex. His lips parted as if he was trying to imagine how she would taste down there.

Irulan was hot, so very hot, and the way he stared at her, the way he handled her body was of no help at all.

It was the moment his fingers touched her burning center that she realized how sensitive and wet she truly was. Feyd-Rautha hissed, realizing that very same thing. He began playing with her flesh as if he was a boy with a toy, and she heart the sounds of her own sex dripping and parting for him whichever way he wished.

“Beautiful,” he murmured, making her even wetter. This was affecting him too, it appeared—his cock was so hard and aching it was slowly turning red.

But of course, he couldn’t leave his knife behind. As he brought the knife closer to her core, Irulan panicked, kicking at him and trying to get away, but his grip on her thigh was like vice, she couldn’t move.

“Shhh,” he said, caressing her thigh. “There’ll be nothing but pleasure, wife.”

Irulan was certain that his definition of pleasure differed from hers, so she kept squirming. Only slightly annoyed, Feyd-Rautha gripped his knife tightly by the blade and pushed the handle past her nether lips.

Irulan released a prolonged moan when his thumb found her clitoris and began rubbing circles while simulteneously thrusting the handle of his knife in and out of her.

“That’s it, wife,” he groaned, watching the way her face furrowed in pleasure. “Take my knife like a good girl.”

And she did. His moves grew aggressive, but even the sight of his blood as the sharp blade tore the skin of his palm where he gripped it did not deter her—she was too focused moving her hips in tandem with his thrusts, chasing her pleasure.

Only when she was at the precipice of her own release did he stop abruptly, pulling out the knife out of her and throwing it on the ground. Irulan was irrationally angry and disappointed, but that feeling soon ceased as Feyd-Rautha fondled her body, mostly her breasts and bottom, with his hands, leaving a bloody trail wherever he touched her.

Once finished, he began stroking his now-turned-blue cock, watching her soiled body as a mesmerizing painting. He then lined the head of his cock with her entrance and she tensed without meaning to. He put only the tip in, but Irulan tensed furthermore. He towered over her with his entire body, but not threateningly, it was more like a promise to keep her safe. Feyd-Rautha caressed her cheek, pushing in more, and she hissed from the pain that not even his tender movements helped soothe.

He was patient with her that night, but he wasn’t that patient, so after a few minutes of trying to slowly push into her, Feyd-Rautha thrust all of himself into her while kissing her at the same time, catching the pained scream that tore out of her with his mouth. He kept kissing her and moving inside of her until he was sure she wasn’t going to scream and that the pain eased a little. He pulled away slightly just to watch her breasts move at the rhythm his hips had set.

“Such a good wife I have,” he praised. “Taking me so well.” Irulan whimpered when the pain in her lower abdomen was slowly replaced with pleasure. “That’s it,” he said, moving his face closer to hers. “I want you to look at me as you come on my cock, princess.”

She did.

Irulan woke up. Her body ached and she felt disoriented, reaching out for the warm body that kept her close the whole night. She found the other side of the bed empty.

She washed off the blood from her thighs—her blood—and his blood from all the other places. It was foolish of her to expect Feyd-Rautha to stay until morning as a loving husband, but the abandonment still hurt.

She found a dress to put on and then sat down to brush her hair when a knock came.

“Princess Irulan, na-Baron is calling for you,” a servant said.

“Tell him I’m preoccupied with something.”

“I’m afraid this isn’t an offer, princess.”

And so, two minutes later, she was following the servant down the clinically sterile yet dark corridors, until he led her to a door, saying, “Na-Baron is already waiting for her.”

Na-Baron was actually not waiting for her at all, if his physical state was any sign of that. When Irulan got into the room, she found Feyd-Rautha in no need of any more attentions from another woman. He lied sprawled on a divan while his three concubines attended to his needs: two of them were sucking on his cock as if it were a candy while the third one kissed, but and nibbled on the skin of his chest, neck and shoulders. However, his cock, no matter what they did, remained flaccid.

Irulan reddened at the sight but more than anything she was furious. She would’ve turned on her heel and left right then, if Feyd-Rautha hadn’t already caught her with his eyes.

“There you are, wife,” he spoke to her. “After the magical night I spent with you, my concubines seem to be unable to satisfy me properly. I thought it would help the mattes at hand if you joined them. So, princess, care to join?” he motioned at the tow women sucking his cock. None of the three of them paid her any mind but she felt wrath emanating from them all the same.

Irulan didn’t move a single muscle. “I am your wife, not one of your whores, Feyd-Rautha,” she said coldly and tightly.

Feyd-Rautha merely chuckled at her defiance. She stayed in place like a tree grown into the ground, undeterred by his charming laughter.

“Of course not,” he said, still smiling. Then, in a voice that was firm and commanding, “All of you, leave.”

The concubines obeyed immediately, pulling away from him. The one who had his cock in her mouth took it out with a loud pop. They hissed as they passed her, and Irulan waited from them to leave from out the door, not foolish enough to have her back to them. But, just as she was about to leave, she heard, “Not you, wife. They are only pets. You are not one of them.”

Irulan turned back to him, regaining her composure.

He smirked at her. She noticed his cock was beginning to harden.

He beckoned her closer, “Come.”

She took slow steps toward him as he watched her every move with unblinking eyes. Irulan came to stand in front of him, raising her chin. “What do you want from me, Feyd-Rautha?” she demanded.

His grin only widened. “I want you to satisfy your husband. You didn’t like seeing me with my concubines? Then you do the job. Let me have all of you. Let me ruin you.”

Irulan stared down at him, seemingly unaffected by his words, although her insides were burning. However, he seemed to be seeing right through her. Neither of them said another word, both staring at one another, waiting for who will star first.

Irulan couldn’t handle it any longer, not when his cock was now as hard as ever and her own arousal was practically running down her inner thighs.

She leaned down and lifted her skirt just enough so she could straddle him. She didn’t sit on top of his cock, only the outside of their nether regions was touching. As she wore no undergarments, she could feel that his flesh was hotter than hers, almost feverish.

The smile disappeared from Feyd-Rautha’s face, giving space for a deeply focused expression. She moved her hips to tease his swollen cock and he hissed from the stimulation, grabbing her hips instinctively and hoisted your skirt enough to have her bared for his eyes only.

“Don’t tease me, princess,” he groaned. That was enough for Irulan. She lifted her hips and sank down onto him, eliciting a prolonged moan from the both of them. She was still sore and he was huge, but she soon found a comfortable rhythm that brought waves of pleasure to her core. Feyd-Rautha watched her intensely with his black eyes, but when your thighs began to give out and the strain on your muscles seemed like too much, he took over, thrusting into her from below, grabbing her by the back of her neck to bring her lips to his. He kissed her like a starved man, all the while untwining the braid she had quickly put together before running off to him. When her hair was freed, he sunk his fingers into it—she remembered him giving special attention to her hair last night too. It must’ve been one of the things his concubines couldn’t give him.

Whereas Irulan’s moves were slow and sensual, Feyd-Rautha set a vicious pace, one she couldn’t catch up with, so she let him grab her arms by the wrists and pull them behind her, taking full control of her entire body. She moaned and mewled on top of him, her breathing growing labored. She was on the edge of her climax, but stopped herself from coming, watching as Feyd-Rautha’s expression grew violent as he neared his own end. And just as he was about to come, she told him, “You won’t lie with your concubines anymore. They won’t entertain you and you won’t give them special treatment. If you want release, you will come to me and me only, is that clear, Feyd-Rautha?”

His face twisted from pleasure and Irulan leaned in closer, touching his forehead with her own as he thrust into her the last few times.

“Yes, yes, anything you want, my wife…” he answered breathlessly.

Satisfied with her work yet careful not to show him, Irulan pulled away from him and his cock, standing back up and fixing her skirt. Feyd-Rautha, still heaving, reached out his head as if to touch the fabric of her dress or the ends of her hair, but she had already found her way to the door, leaving him all alone.

As she walked down the dark corridors, Irulan was lost in thoughts of the scene that just passed between them, and so she didn’t notice someone lurking for her in the shadows. Three figures then stood in her way, and even though it was dark, the three concubines of Feyd-Rautha were hard to miss. They were hissing at her, fury evident in their abnormal features as they lunged at her, baring their black teeth. Before Irulan managed to scream or shout for help, one of them forced her mouth shut with her hand, the other grabbed her by the hair and held her hands down, and the third gripped her right hadn’t, exposing her forehearm. Irulan saw the sharp silver blade glinting in the low light. Her eyes widened and she squirmed, trying to free herself, but to no avail.

The concubine brought the blade to Irulan’s veins and spat in her face, “Na-Baron is ours,” before slicing her flesh.

Unimaginable pain reddened Irulans’s vision. She screamed and thrashed until all strength abandoned her, and, sensing that, the concubines released her, letting her fall to the ground. When her head hit the ground, Irulan was drowned in darkness.

Irulan regained consciousness in an unfamiliar room with an never-before-seen face in front her and a dull ache in her arm.

She blinked awake and tried to sit up in bed, but the man before her held her down softly. “Easy, princess. You’re very hurt.”

Irulan then noticed that the man was slicing a needle through her already mutilated flesh. The white thread that sealed her wound contrasted with the red-brown blood. She was sleepy and her mind was working very slowly, but all sleepiness evaded her once she heard a voice outside the room shout, “Where’s my wife!”

No one was there to answer Feyd-Rautha’s command, and they needn’t be—a moment later, he burst through the door like a sandstorm.

His eyes found her lying form immediately as he strode forward until he was right beside her. There was no smile on his face, nothing but ferocious outrage. His black gaze eyed the wound in her arm.

“Who did this to you?” he demanded, his voice low with rage.

She scoffed. “I won’t tell you. I don’t have a death wish.”

“Who,” he repeated.

Irulan narrowed her eyes at him. “They must have been listening behind the door as we… spoke.”

That was enough for him. After another moment of intense eyeing, Feyd-Rautha turned around and left. No sooner had the man that must’ve been her healer finished stitching up her wound that her husband was back.

“Come with me,” he said, reaching out his hand for her to take. “It won’t be far.”

She took it, despite how tired she felt.

Feyd-Rautha led her to a room with black walls and floor, and she noticed the three women lined up with their heads bowed low, their white skin glinting in the black darkness like fog. He made Irulan stand in front of them as he took his knife from the table besides and then came back to her.

“Which one of them hurt you?” he asked.

Irulan swallowed. “If I tell you, next time they will surely kill me.”

Without taking his eyes off her, without even moving—Irulan only saw his right hand slice the air swiftly—but it didn’t slice air, it slid the first concubine’s throat. Blood poured from the wound as the woman grasped at her throat in panic, trying to desperately stop the bleeding. She fell to the ground with a thud—the same way Irulan had mere hours ago.

“Was it this one?” Feyd-Rautha asked, never letting his eyes leave her.

Irulan shook her head. “She held my mouth shut.”

The other two bowed their heads even lower, visibly shivering.

The fury that overcame him was more visible by the way his muscles twitched under his skin. The second kill was just as smooth and barely visible, the same scenario repeating itself—Feyd-Rautha sliced the throat of the concubine and she fell dead.

“This one?”

“She grabbed me by my hair,” Irulan said.

He took a step toward the last of his pets, not sparing her a single glance, and the woman fell to her knees before him, “Na-Baron, I did nothing wrong, I’m begging you, she’s lying!”

Feyd-Rautha looked down at his concubine with nothing but wrath in his eyes. Then looked back up at Irulan.

“Did this one draw your blood?”

She swallowed, then nodded, watching with wide eyes as Feyd-Rautha’s blade sank into the left eye of the concubine. She screamed as blood poured from it, trying to stop the flow just like the other two before her. He pulled the blade out and repeated the process on the other eye. Then, more driven by a wish to end this as soon as possible rather than a sentimental feeling of mercy, he slit her throat, ending the third life.

Irulan watched in awe at the three bodies at her feet but Feyd-Rautha’s presence was the only one that demanded attention.

She looked up at him. He stepped closer, taking her face in his palm while the other hand held the bloody knife.

“I promised you, wife,” he said. “Anything you want.”

THE END

#ao3#fanfic#fanfiction#fanart#archive of our own#ao3 fanfic#feyd rautha#feyd x reader#feyd x you#feyd x irulan#feyd oneshot#dune movie#dune 2#dune part 2#harkonnen#austin butler#dune gifs#dune part two#feyd-rautha

201 notes

·

View notes

Photo

There’s no end of opinions about Buster Keaton’s work & whilst I’d place him on the highest pedestal, other critics are little more grounded. Here’s what Paul Rotha had to say in his 1930 book, ‘The Film Till Now; A Survey of the Cinema’

“Apart from the comedies of Chaplin it is necessary only to mention

the more recent work of Buster Keaton and the expensive knockabout contraptions of Harold Lloyd. Keaton at his best, as in The General, College, and the first two reels of Spite Marriage, has real merit. His humour is dry, exceptionally well constructed and almost entirely mechanical in execution. He has set himself the task of an assumed personality, which succeeds in becoming comic by its very sameness. He relies, also, on the old method of repetition, which when enhanced by his own inscrutable individuality becomes incredibly funny. His comedies show an extensive knowledge of the contrast of shapes and sizes and an extremely pleasing sense of the ludicrous. Keaton has, above all, the great asset of being funny in himself. He looks odd, does extraordinary things and employs uproariously funny situations with considerable skill. The Keaton films are usually very well photographed, with a minimum of detail and a maximum of effect. It would be ungrateful,perhaps, to suggest that he takes from Chaplin that which is essentially Chaplin's, but, nevertheless, Keaton has learnt from the great genius and would probably be the first to admit it.”

Amusingly, he also mentions Donald Crisp, whose efforts on ‘The Navigator’ were almost entirely reshot because Buster was unimpressed with the result. He pretended it was a wrap & sent Crisp home!

“Donald Crisp is a director of the good, honest type, with a simple go-ahead idea of telling a story. He has made, among others, one of the best of the post-war Fairbanks films, ‘Don Q’, and Buster Keaton's ‘The Navigator’.”

#buster keaton#the great stoneface#paul rotha#donald crisp#charlie chaplin#the navigator#1920s#silent era#silent movies#vintage hollywood#harold lloyd#the general#college#spite marriage#critique

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

You Oughta “Get Carter”

Another old Night Flight piece, tied to a Turner Classic Movies airing, about a movie I never tire of watching. (Unfortunately, the Krays film “Legend” turned out to be not so good.)

**********

The English gangster movie has proven an enduring genre to this day. The 1971 picture that jumpstarted the long-lived cycle, Get Carter, Mike Hodges’ bracing, brutal tale of a mobster’s revenge, screens late Thursday on TCM as part of a day-long tribute to Michael Caine, who stars as the film’s titular anti-hero.

We won’t have to wait long for the next high-profile Brit-mob saga: October will see the premiere of Brian Helgeland’s Legend, a new feature starring Tom Hardy (Mad Max: Fury Road, The Dark Knight Rises, Locke) in a tour de force dual role as Ronnie and Reggie Kray, the legendarily murderous identical twin gangleaders who terrorized London in the ‘60s. The violent exploits of the Krays mesmerized Fleet Street’s journalists and the British populace until the brothers and most of the top members of their “firm” were arrested in 1968.

The siblings both died in prison after receiving life sentences. They’ve been the subjects of several English TV documentaries and a 1990 feature starring Martin and Gary Kemp of Spandau Ballet. However, the Krays and their seamy milieu may have had their greatest impact in fictional form, via the durable figure of Jack Carter, the creation of a shy, alcoholic graphic artist, animator, and fiction writer named Ted Lewis, the man now recognized by many as “the father of British noir.”

Born in 1940 in a Manchester suburb, Lewis was raised in the small town of Barton-upon-Humber in the dank English midlands. A sickly child, he became engrossed with art, the movies, and writing. The product of an English art school in nearby Hull, he wrote his first, unsuccessful novel, a semi-autobiographical piece of “kitchen sink” realism called All the Way Home and All the Night Through, in 1965.

He soon moved sideways into movie animation, serving as clean-up supervisor on George Dunning’s Beatles feature Yellow Submarine (1968). However, now married with a couple of children, he decided to return to writing with an eye to crafting a commercial hit, and in 1970 he published a startling, ultra-hardboiled novel titled Jack’s Return Home.

British fiction had never produced anything quite like the book’s protagonist Jack Carter. He is the enforcer for a pair of London gangsters, Gerald and Les Fletcher, who bear more than a passing resemblance to the Krays. At the outset of the book, recounted in the first person, Carter travels by train to an unnamed city in the British midlands (modeled after the city of Scunthorpe near Lewis’ hometown) to bury his brother Frank, who has died in an alleged drunk driving accident.

Carter instantly susses that his brother was murdered, and he sets about sorting out a hierarchy of low-end midlands criminals (all of whom he knew in his early days as a budding hoodlum) responsible for the crime, investigating the act with a gun in his hand and a heart filled with hate. He’s no Sam Spade or Phillip Marlowe bound by a moral code – in fact, he once bedded Frank’s wife, and is now sleeping with his boss Gerald’s spouse. He’s a sociopathic career criminal and professional killer – a “villain,” in the English term -- who will use any means at his disposal to secure his revenge.

Carter’s pursuit of rough justice for his brother, and for a despoiled niece, attracts the attention of the Fletchers, whose business relationships with the Northern mob are being disrupted by their lieutenant’s campaign of vengeance. As Carter leaves behind a trail of corpses and homes in on the last of his quarry, the hunter has become the hunted, and Jack’s Return Home climaxes with scenes of bloodletting worthy of a Jacobean tragedy, or of Grand Guignol.

Before its publication, Lewis’ grimy, violent book attracted the attention of Michael Klinger, who had produced Roman Polanski’s stunning ‘60s features Repulsion and Cul-de-Sac. Klinger acquired film rights to the novel before its publication in 1970, and sent a galley copy to Mike Hodges, then a U.K. TV director with no feature credits.

Hodges, who immediately signed on as director and screenwriter of Klinger’s feature – which was retitled Get Carter -- was not only drawn to the taut, fierce action, but also by the opportunity to peel away the veneer of propriety that still lingered in British society and culture. As he noted in his 2000 commentary for the U.S. DVD release of the film, “You cannot deny that [in England], like anywhere else, corruption is endemic.”

Casting was key to the potential box office prospects of the feature, and Klinger and Hodges’ masterstroke was securing Michael Caine to play Jack Carter. By 1970, Caine had become an international star, portraying spy novelist Len Deighton’s agent Harry Palmer in three pictures and garnering raves as the eponymous philanderer in Alfie.

Caine had himself known some hard cases in his London neighborhood; in his own DVD commentary, he says that his dead-eyed, terrifyingly reserved Carter was “an amalgam of people I grew up with – I’d known them all my life.” Hodges notes of Caine’s Carter, “There’s a ruthlessness about him, and I would have been foolish not to use it to the advantage of the film.”

Playing what he knew, Caine gave the performance of a lifetime – a study in steely cool, punctuated by sudden outbursts of unfettered fury. The actor summarizes his character on the DVD: “Here was a dastardly man coming as the savior of a lady’s honor. It’s the knight saving the damsel in distress, except this knight is not a very noble or gallant one. It’s the villain as hero.”

The supporting players were cast with equal skill. Ian Hendry, who was originally considered for the role of Carter, ultimately portrayed the hit man’s principal nemesis and target Eric Paice. Caine and Hendry’s first faceoff in the film, an economical conversation at a local racetrack, seethes with unfeigned tension and unease – Caine was wary of Hendry, whose deep alcoholism made the production a difficult one, while Hendry was jealous of the leading man’s greater success.

For Northern mob kingpin Cyril Kinnear, Hodges recruited John Osborne, then best known in Great Britain as the writer of the hugely successfully 1956 play Look Back in Anger, Laurence Olivier’s screen and stage triumph The Entertainer, and Tony Richardson’s period comedy Tom Jones, for which he won an Oscar for best adapted screenplay. Osborne, a skilled actor before he found fame as a writer, brings subdued, purring menace to the part.

Though her part was far smaller than those of such other supporting actresses as Geraldine Moffat, Rosemarie Dunham, and Dorothy White, Brit sex bomb Britt Ekland received third billing as Anna, Gerald Fletcher’s wife and Carter’s mistress. Her marquee prominence is somewhat justified by an eye-popping sequence in which she engages in a few minutes of steamy phone sex with Caine.

Some small roles were populated by real British villains. George Sewell, who plays the Fletchers’ minion Con McCarty, was a familiar of the Krays’ older brother Charlie, and introduced the elder mobster to Carry On comedy series actress Barbara Windsor, who subsequently married another member of the Kray firm. John Bindon, who appears briefly as the younger Fletcher sibling, was a hood and racketeer who later stood trial for murder; a notorious womanizer, he romanced Princess Margaret, whose clandestine relationship with Bindon later became a key plot turn in the 2008 Jason Strathan gangster vehicle The Bank Job.

Verisimilitude was everything for Hodges, who shot nearly all of the film on grimly realistic locations in Newcastle, the down-at-the-heel coal-mining town on England’s northeastern coast. The director vibrantly employs interiors of the city’s seedy pubs, rooming houses, nightclubs and betting parlors. In one inspired bit of local color, he uses an appearance by a local girl’s marching band, the Pelaw Hussars, to drolly enliven a scene in which a nude, shotgun-toting Carter backs down the Fletchers’ gunmen.

The film’s relentless action was perfectly framed by director of photography Wolfgang Suchitzky, whose experience as a cameraman for documentarian Paul Rotha is put to excellent use. Some sequences are masterfully shot with available light; the movie’s most brutal murder plays out at night by a car’s headlights. The breathtakingly staged final showdown between Carter and Paice is shot under lowering skies against the grey backdrop of a North Sea coal slag dump.

Tough, uncompromising, and utterly unprecedented in English cinema, Get Carter was a hit in the U.K. It fared poorly in the U.S., where its distributor Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer dumped it on the market as the lower half of a double bill with the Frank Sinatra Western spoof Dirty Dingus Magee. In his DVD commentary, Caine notes that it was only after Ted Turner acquired MGM’s catalog and broadcast the film on his cable networks that the movie developed a cult audience in the States.

Get Carter has received two American remakes. The first, George Armitage’s oft-risible 1972 blaxploitation adaptation Hit Man, starred Bernie Casey as Carter’s African-American counterpart Tyrone Tackett. It is notable for a spectacularly undraped appearance by Pam Grier, whose character meets a hilarious demise that is somewhat spoiled by the picture’s amusing trailer. (Casey and Keenan Ivory Wayans later lampooned the film in the 1988 blaxploitation parody I’m Gonna Git You Sucka.)

Hodges’ film was drearily Americanized and relocated to Seattle in Stephen Kay’s like-titled 2000 Sylvester Stallone vehicle. It’s a sluggish, misbegotten venture, about which the less that is said the better. Michael Caine’s presence in the cast as villain Cliff Brumby (played in the original by Brian Mosley) only serves to remind viewers that they are watching a vastly inferior rendering of a classic.

Ted Lewis wrote seven more novels after Jack’s Return Home, and returned to Jack Carter for two prequels. The first of them, Jack Carter’s Law (1970), an almost equally intense installment in which Carter ferrets out a “grass” – an informer – in the Fletchers’ organization, is a deep passage through the London underworld of the ‘60s, full of warring gangsters and venal, dishonest coppers.

The final episode in the trilogy, Jack Carter and the Mafia Pigeon (1977), was a sad swan song for British noir’s most memorable bad man. In it, Carter travels to the Mediterranean island of Majorca on a Fletchers-funded “holiday,” only to discover that he has actually been dispatched to guard a jittery American mobster hiding out at the gang’s villa. It’s a flabby, obvious, and needlessly discursive book; Lewis’ exhaustion is apparent in his desperate re-use of a plot point central to the action of the first Carter novel.

Curiously, the locale and setup of Mafia Pigeon appear to be derived from Pulp, the 1975 film that reunited director Hodges and actor Caine. In it, the actor plays a writer of sleazy paperback thrillers who travels to the Mediterranean isle of Malta to pen the memoirs of Preston Gilbert (Mickey Rooney), a Hollywood actor with gangland connections. Hilarity and mayhem ensue.

All of Lewis’ characters consume enough alcohol to put down an elephant, and Lewis himself succumbed to alcoholism in 1982, at the age of 42. Virtually unemployable, he had moved back home to Barton-upon-Humber, where lived with his parents.

He went out with a bang, however: In 1980, he published his final and finest book, the truly explosive mob thriller GBH (the British abbreviation for “grievous bodily harm”). The novel focuses on the last days of vice lord George Fowler, a sadist in the grand Krays manner, whose empire is being toppled by internal treachery. Using a unique time-shifting structure that darts back and forth between “the smoke” (London) and “the sea” (Fowler’s oceanside hideout), it reaches a finale of infernal, hallucinatory intensity.

After Lewis’ death, his work fell into obscurity, and his novels were unavailable in America for decades. Happily, Soho Press reissued the Carter trilogy in paperback in 2014 and republished GBH in hardback earlier this year. Now U.S. readers have the opportunity to read the books that influenced an entire school of English noir writers, including such Lewis disciples and venerators as Derek Raymond, David Peace, and Jake Arnott.

Echoes of GBH can be heard in The Long Good Friday, another esteemed English gangster film starring Bob Hoskins as the arrogant and impetuous chief of a collapsing London firm. Released the same year as Lewis’ last novel, the John Mackenzie-directed feature is only one of a succession of outstanding movies – The Limey, The Hit, Layer Cake, Sexy Beast, and Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels among them – that owe a debt to Get Carter, the daddy of them all.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Diuna 2020 cały film online zalukaj lektor polski

http://diunacdaonline.pl/diuna-2020-caly-film-online-zalukaj-lektor-polski/

Opis filmu:

Diuna to epicki film science fiction 2020 w reżyserii Denisa Villeneuve ze scenariuszem autorstwa Jona Spaihtsa, Erica Rotha i Villeneuve. Film jest koprodukcją międzynarodową Kanady, Węgier, Wielkiej Brytanii i Stanów Zjednoczonych i jest pierwszą z planowanej dwuczęściowej adaptacji powieści Franka Herberta z 1965 roku o tym samym tytule, która obejmie mniej więcej pierwsza połowa książki.

W filmie występuje obsada, w tym Timothée Chalamet, Rebecca Ferguson, Oscar Isaac, Josh Brolin, Stellan Skarsgård, Dave Bautista, Stephen McKinley Henderson, Zendaya, David Dastmalchian, Chang Chen, Sharon Duncan-Brewster, Charlotte Rampling, Jason Momoa i Javier Bardem .

Wydanie Dune w Stanach Zjednoczonych w IMAX i 3D planowane jest na 18 grudnia 2020 r. Nakładem Warner Bros. Pictures.

Fabuła:

W dalekiej przyszłości ludzkości książę Leto Atreides przyjmuje zarządcę niebezpiecznej pustynnej planety Arrakis, znanej również jako Dune, jedynego źródła najcenniejszej substancji we wszechświecie, „przyprawy”, leku, który przedłuża ludzkie życie, dostarcza nadludzkiej poziomy myślenia i umożliwia podróżowanie po przestrzeniach składanych. Chociaż Leto wie, że okazja jest skomplikowaną pułapką zastawioną przez jego wrogów, zabiera swoją konkubinę Bene Gesserit, Lady Jessikę, młodego syna i spadkobiercę Paula oraz najbardziej zaufanych doradców na Arrakis. Leto przejmuje kontrolę nad operacją wydobywania przypraw, która jest niebezpieczna z powodu obecności gigantycznych robaków piaskowych. Gorzka zdrada prowadzi Paula i Jessicę do Fremenów, tubylców Arrakis, którzy żyją na głębokiej pustyni.

Produkcja

Krótko po publikacji w 1965 roku, Dune została zidentyfikowana jako potencjalna filmowa perspektywa, a prawa do adaptacji powieści na film posiada kilku producentów od 1971 roku. Podjęto wiele prób nakręcenia takiego filmu i jest on uważany za trudna praca przy dostosowaniu się do ekranu ze względu na obszerność treści. Słynny filmowiec Alejandro Jodorowsky nabył w latach 70. prawa do ekstrawaganckiej, dziesięciogodzinnej adaptacji książki, ale projekt się rozpadł. Wysiłki, by nakręcić film później, zostały udokumentowane w filmie dokumentalnym Jodorowsky’s Dune, który ukazał się w 2013 roku. Przed tym filmem z powodzeniem wydano dwie osobne adaptacje na żywo; Dune z 1984 roku w reżyserii Davida Lyncha i miniserial z 2000 roku na kanale Sci Fi, wyprodukowany przez Richarda P. Rubinsteina, który posiadał prawa do filmu Dune od 1996 roku.

Rozwój

Denis Villeneuve stwierdził w wywiadach, że zrobienie nowej adaptacji Diuny było jego życiową ambicją. Został zatrudniony jako reżyser w lutym 2017.

W 2008 roku Paramount Pictures ogłosiło, że ma nową fabularną adaptację Dune Franka Herberta w produkcji, której reżyserem będzie Peter Berg. Berg opuścił projekt w październiku 2009 r., A dyrektor Pierre Morel został powołany do kierowania nim w styczniu 2010 r., Zanim Paramount zrezygnował z projektu w marcu 2011 r., Ponieważ nie mogli dojść do kluczowych umów, a ich prawa wygasły z powrotem do Rubinsteina.

21 listopada 2016 roku ogłoszono, że Legendary Pictures nabyło prawa do filmu i telewizji Dune. W grudniu 2016 roku Variety poinformowało, że reżyser Denis Villeneuve rozmawiał ze studiem, aby wyreżyserować film. We wrześniu 2016 r. Villeneuve wyraził zainteresowanie projektem, mówiąc, że „moim od dawna marzeniem jest adaptacja Dune, ale uzyskanie praw to długi proces i nie sądzę, by mi się udało”. Villeneuve powiedział, że czuł, że nie jest gotowy do wyreżyserowania filmu Diuny, dopóki nie ukończył projektów takich jak Przybycie i Blade Runner 2049, a mając doświadczenie w filmach science fiction, „Dune to mój świat”. Do lutego 2017 roku Brian Herbert, syn Franka i autor późniejszych książek z serii Diuny, potwierdził, że Villeneuve będzie kierował projektem.

John Nelson został zatrudniony jako kierownik ds. Efektów wizualnych do filmu w lipcu 2018 roku, ale od tego czasu opuścił projekt. W grudniu 2018 roku ogłoszono, że autor zdjęć Roger Deakins, który miał ponownie połączyć się z Villeneuve przy filmie, nie pracuje nad Dune i że Greig Fraser przyjedzie do projektu jako reżyser zdjęć. W styczniu 2019 roku Joe Walker został potwierdzony jako montażysta filmu. Inna załoga to: Brad Riker jako nadzorujący dyrektor artystyczny; Patrice Vermette jako scenograf; Paul Lambert jako opiekunowie efektów wizualnych; Gerd Nefzer jako kierownik ds. Efektów specjalnych; a Thomas Struthers jako koordynator kaskaderów. Producentami Dune będą Villeneuve, Mary Parent i Cale Boyter, a Tanya Lapointe, Brian Herbert, Byron Merritt, Kim Herbert, Thomas Tull, Jon Spaihts, Richard P. Rubinstein, John Harrison i Herbert W. Gain będą producentami wykonawczymi i Kevin J. Anderson jako konsultant kreatywny. Twórca języka Game of Thrones, David Peterson, został potwierdzony, że opracowuje języki do filmu w kwietniu 2019 roku.

Pisanie

W marcu 2018 roku Villeneuve stwierdził, że jego celem jest adaptacja powieści na dwuczęściowy serial filmowy. Villeneuve ostatecznie podpisał kontrakt na dwa filmy z Warner Bros. Pictures, w tym samym stylu, co dwuczęściowa adaptacja It Stephena Kinga w 2017 i 2019 roku. Stwierdził, że „Nie zgodziłbym się na wykonanie tej adaptacji książki jednym pojedynczy film „jako Diuna” był „zbyt złożony” z „mocą w szczegółach”, których nie udało się uchwycić w jednym filmie. Eric Roth został zatrudniony do współtworzenia scenariusza w kwietniu, a później potwierdzono, że Jon Spaihts współtworzył scenariusz wraz z Roth i Villeneuve. Villeneuve powiedział w maju 2018 r., Że pierwszy szkic scenariusza został ukończony. Brian Herbert potwierdził w lipcu 2018 r., Że najnowszy szkic scenariusza obejmuje „mniej więcej połowę powieści Dune”. Legendarny dyrektor generalny Joshua Grode potwierdził w kwietniu 2019 r., Że planują nakręcić kontynuację, dodając, że „istnieje logiczne miejsce na zatrzymanie [pierwszego] filmu przed zakończeniem książki”. W listopadzie 2019 roku Spaihts ustąpił ze stanowiska showrunnera w prequelu telewizyjnego Dune: The Sisterhood, aby skupić się na drugim filmie.

Filmowanie

Filmowanie rozpoczęło się 18 marca 2019 roku w Origo Film Studios w Budapeszcie na Węgrzech, a także odbyło się w Jordanii. Pierwsza część filmu, która rozgrywa się na planecie Caladan, została nakręcona w Stadlandet w Norwegii. Filmowanie główne zostało ukończone w lipcu 2019 r. Dodatkowe zdjęcia mają się odbyć w Budapeszcie w sierpniu 2020 r., Ale nie oczekuje się, że wpłyną one na datę premiery filmu.

---------------------------

Nasze media:

---------------------------

➤ Strona: http://diunacdaonline.pl/

➤ FB: https://www.facebook.com/Diuna-2020-CDA-Online-Lektor-Polski-100870458386189

➤ YT: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCbUJvjxRslljn2bwlXEehig

1 note

·

View note

Text

An Excerpt of the Essay: David Lynch Keeps His Head by David Foster Wallace

I know a lot of you love David Lynch and this is an EXCELLENT defense and deconstruction of his work. The full essay is largely about the film Lost Highway, which was about to be released, and is 67 pages with 61 footnotes. The whole essay is incredibly entertaining and if you like to read, is worth it. You can find it here: x. This excerpt mainly concerns Blue Velvet and Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me. I put the footnotes at the end, I know it isn’t ideal, but it is hard when there aren’t pages.

9A. The cinematic tradition it’s curious that nobody seems to have observed Lynch comes right out of (w/ an epigraph)

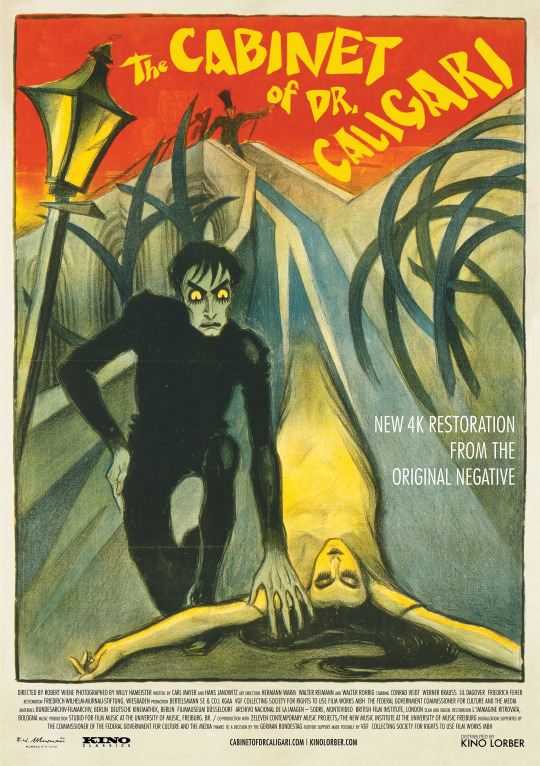

“It has been said that the admirers of The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari are usually painters, or people who think and remember graphically. This is a mistaken conception.”

—Paul Rotha, “The German Film”

Since Lynch was trained as a painter (an Ab-Exp painter at that), it seems curious that no film critics or scholars(42) have ever treated of his movies’ clear relation to the classical Expressionist cinema tradition of Wiene, Kobe, early Lang, etc. And I am talking here about the very simplest and most straightforward sort of definition of Expressionist, viz. “Using objects and characters not as representations but as transmitters for the director’s own internal impressions and moods.”

Certainly plenty of critics have observed, with Kael, that in Lynch’s movies “There’s very little art between you and the filmmaker’s psyche…because there’s less than the usual amount of inhibition.” They’ve noted the preponderance of fetishes and fixations in Lynch’s work, his characters’ lack of conventional introspection (an introspection which in film equals “subjectivity”), his sexualization of everything from an amputated limb to a bathrobe’s sash, from a skull to a “heart plug,”(43) from split lockets to length-cut timber. They’ve noted the elaboration of Freudian motifs that tremble on the edge of parodic cliche—the way Marietta’s invitation to Sailor to “fuck Mommy” takes place in a bathroom and produces a rage that’s then displaced onto Bob Ray Lemon; the way Merrick’s opening dream-fantasy of his mother supine before a rampaging elephant has her face working in what’s interpretable as either terror or orgasm; the way Lynch structures Dune’s labrynthian plot to highlight Paul Eutrades’s “escape” with his “witch-mother” after Paul’s father’s “death” and “betrayal.” They have noted with particular emphasis what’s pretty much Lynch’s most famous scene, Blue Velvet’s Jeffrey Beaumont peering through a closet’s slats as Frank Booth rapes Dorothy while referring to himself as “Daddy” and to her as “Mommy” and promising dire punishments for “looking at me” and breathing through an unexplained gas mask that’s overtly similar to the O2-mask we’d just seen Jeffrey’s own dying Dad breathing through.

They’ve noted all this, critics have, and they’ve noted how, despite its heaviness, this Freudian stuff tends to give Lynch’s movies an enormous psychological power; and yet they don’t seem to make the obvious point that these very heavy Freudian riffs are powerful instead of ridiculous because they are deployed Expressionistically, which among other things means they’re deployed in an old-fashioned, pre-postmodern way, I.e. nakedly, sincerely, without postmodernism’s abstraction or irony. Jeffrey Beaumont’s interslat voyeurism may be a sick parody of the Primal Scene, but neither he (a “college boy”) nor anybody else in the movie ever shows any inclination to say something like “Gee, this is sort of like a sick parody of the good old Primal Scene” or even betrays any awareness that a lot of what’s going on is—both symbolically and psychoanalytically—heavy as hell. Lynch’s movies, for all their unsubtle archetypes and symbols and intertextual references and c., have about them the remarkable unselfish-consciousness that’s kind of the hallmark of Expressionist art—nobody in Lynch’s movies analyzes or metacriticizes or hermenteuticizes or anything(44), including Lynch himself. This set of restrictions makes Lynch’s movies fundamentally unironic, and I submit that Lynch’s lack of irony is the real reason some cineastes—in this age when ironic self-consciousness is the one and only universally recognized badge of sophistication—see him as a naif or a buffoon. In fact, Lynch is neither—though nor is he any kind of genius of visual coding or tertiary symbolism or anything. What he is is a weird hybrid blend of classical Expressionist and contemporary postmodernist, an artist whose own “internal impressions and moods” are (like ours) an olla podrida of neurogenic predisposition and phylogenic myth and psychoanalytic schema and pop-cultural iconography—in other words, Lynch is sort of G. W. Pabst with an Elvis ducktail.

This kind of contemporary Expressionist art, in order to be any good, seems like it needs to avoid two pitfalls. The first is a self-consciousness of form where everything gets very mannered and refers cutely to itself.(45) The second pitfall, more complicated, might be called “terminal idiosyncrasy” or “antiempathetic solipsism” or something: here the artist’s own perceptions and moods and impressions and obsessions come off as just too particular to him alone. Art, after all, is supposed to be a kind of communication, and “personal expression” is cinematically interesting only to the extent that what’s expressed finds and strikes chords within the viewer. The difference between experiencing art that succeeds as communication and art that doesn’t is rather like the difference between being sexually intimate with a person and watching that person masturbate. In terms of literature, richly communicative Expressionism is epitomized by Kafka, bad and onanistic Expressionism by the average Graduate Writing Program avant-garde story.

It’s the second pitfall that’s especially bottomless and dreadful, and Lynch’s best movie, Blue Velvet, avoided it so spectacularly that seeing the movie when it first came out was a kind of revelation for me. It was such a big deal that ten years later I remember the date—30 March 1986, a Wednesday night—and what the whole group of us MFA Program(46) students did after we left the theater, which was to go to a coffeehouse and talk about how the movie was a revelation. Our Graduate MFA Program had been pretty much of a downer so far: most of us wanted to see ourselves as avant-garde writers, and our professors were all traditional commercial Realists of the New Yorker school, and while we loathed these teachers and resented the chilly reception our “experimental” writing received from them, we were also starting to recognize that most of our own avant-garde stuff really was solipsistic and pretentious and self-conscious and masturbatory and bad, and so that year we went around hating ourselves and everyone else and with no clue about how to get experimentally better without caving in to loathsome commercial-Realistic pressure, etc. This was the context in which Blue Velvet made such an impression on us. The movie’s obvious “themes”—the evil flip side to picket-fence respectability, the conjunctions of sadism and sexuality and parental authority and voyeurism and cheesy ‘50s pop and Coming of Age, etc.—were for us less revelatory than the way the movie’s surrealism and dream-logic felt: the felt true, real. And the couple things just slightly but marvelously off in every shot—the Yellow Man literally dead on his feet, Frank’s unexplained gas mask, the eerie industrial thrum on the stairway outside Dorothy’s apartment, the weird dentate-vagina sculpture(47) hanging on an otherwise bare wall over Jeffrey’s bed at home, the dog drinking from the hose in the stricken dad’s hand—it wasn’t just that these touches seemed eccentrically cool or experimental or arty, but that they communicated things that felt true. Blue Velvet captured something crucial about the way the U.S. present acted on our nerve endings, something crucial that couldn’t be analyzed or reduced to a system of codes or aesthetic principles or workshop techniques.

This was what was epiphanic for us about Blue Velvet in grad school, when we saw it: the movie helped us realize that first-rate experimentalism was a way not to “transcend” or “rebel against” the truth but actually to honor it. It brought home to us—via images, the medium we were suckled on and most credulous of—that the very most important artistic communications took place at a level that not only wasn’t intellectual but wasn’t even fully conscious, that the unconscious’s true medium wasn’t verbal but imagistic, and that whether the images were Realistic or Postmodern of Expressionistic of Surreal of what-the-hell-ever was less important than whether they felt true, whether they rang psychic cherries in the communicatee.

I don’t know whether any of this makes sense. But it’s basically why David Lynch the filmmaker is important to me. I felt like he showed me something genuine and important on 3/30/86. And he couldn’t have done it if he hadn’t been thoroughly, nakedly, unpretentiously, unsophisticatedly himself, a self that communicates primarily itself—an Expressionist. Whether he is an Expressionist naively or pathologically or ultra-pomo-sophisticatedly is of little importance to me. What is important is that Blue Velvet rang cherries, and it remains for me an example of contemporary artistic heroism.

10A (w/ an epigraph)

“All of Lynch’s work can be described as emotionally infantile…Lynch likes to ride his camera into orifices (a burlap hood’s eyehole or a severed ear), to plumb the blackness beyond. There, id-deep, he fans out his deck of dirty pictures…”—Kathleen Murphy of Film Comment

One reason it’s sort of heroic tot be a contemporary Expressionist is that it all but invites people who don’t like your art to make an ad hominem move from the art to the artist. A fair number of critics(48) object to David Lynch’s movies on the grounds that they are “sick” and “dirty” or “infantile,” then proceed to claim that the movies are themselves revelatory of various deficiencies in Lynch’s own character, (49) troubles that range from developmental arrest to misogyny to sadism. It’s not just the fact that twisted people do hideous things to one another in Lynch’s films, these critics will argue, but rather the “moral attitude” implied by the way Lynch’s camera records hideous behavior. In a way, his detractors have a point. Moral atrocities in Lynch movies are never staged to elicit outrage or even disapproval. The directorial attitude when hideousness occurs seems to range between clinical neutrality and an almost voyeuristic ogling. It’s not an accident that Frank Booth, Bobby Peru, and Leland/“Bob” steal the show in Lynch’s last three films, that there is almost a tropism about our pull toward these characters, because Lynch’s camera is obsessed with them, loves them; they are his movies’ heart.

Some of the ad hominem criticism is harmless, and the director himself has to a certain extent dined out on his “Master of Weird”/“Czar of Bizarre” image, see for example Lynch making his eyes go in two different directions for the cover of Time. The claim, though, that because Lynch’s movies pass no overt “judgement” on hideousness/evil/sickness and in fact make the stuff riveting to watch, the movies are themselves a-or immoral, even evil—this is bullshit of the rankest vintage, and not just because it’s sloppy logic but because it’s symptomatic of the impoverished moral assumptions we seem not to bring to the movies we watch.

I’m going to claim that evil is what David Lynch’s movies are essentially about, and that Lynch’s explorations of human beings’ various relationships to evil are, if idiosyncratic and Expressionistic, nevertheless sensitive and insightful and true. I’m going to submit that the real “moral problem” a lot of cineastes have with Lynch is that we find his truth morally uncomfortable, and that we do not like, when watching movies, to be made uncomfortable. (Unless, of course, our discomfort is used to set up some kind of commercial catharsis—the retribution, the bloodbath, the romantic victory of the misunderstood heroine, etc.—I.e. unless the discomfort serves a conclusion that flatters the same comfortable moral certainties we came into the theater with.)

The fact is that David Lynch treats the subject of evil better than just about anybody else making movies today—better and also differently. His movies aren’t anti-moral, but they are definitely anti-formulaic. Evil-ridden though his filmic world is, please notice that responsibility for evil never in his films devolves easily onto greedy corporations or corrupt politicians or faceless serial kooks. Lynch is not interested in the devolution of responsibility, and he’s not interested in moral judgments of characters. Rather, he’s interested in the psychic spaces in which people are capable of evil. He is interested in Darkness. And Darkness, in David Lynch’s movies, always wears more than one face. Recall, for example, how Blue Velvet’s Frank Booth is both Frank Booth and “the Well-Dressed Man.” How Eraserhead’s whole postapocalyptic world of demonic conceptions and teratoid offspring and summary decapitations is evil…yet how it’s “poor” Henry Spencer who ends up a baby-killer. How in both TV’s Twin Peaks and cinema’s Fire Walk with Me, “Bob” is also Leland Palmer, how they are, “spiritually,” both two and one. The Elephant Man’s sideshow barker is evil in his exploitation of Merrick, but so too is good old kindly Dr. Treeves—and Lynch carefully has Treeves admit this aloud. And if Wild at Heart’s coherence suffered because its myriad villains seemed fuzzy and interchangeable, it was because they were all basically the same thing, I.e. they were all in the service of the same force or spirit. Characters are not themselves evil in Lynch movies—evil wears them.

This point is worth emphasizing. Lynch’s movies are not about monsters (i.e. people whose intrinsic natures are evil) but about hauntings, about evil environment, possibility, force. This helps explain Lynch’s constant deployment of noirish lighting and eerie sound-carpets and grotesque figurants: in his movies’ world, a kind of ambient spiritual antimatter hangs just overhead. It also explains why Lynch’s villains seem not merely wicked or sick but ecstatic, transported: they are, literally, possessed. Think here of Dennis Hopper’s exultant “I’LL FUCK ANYTHING THAT MOVES” in Blue Velvet, or of the incredible scene in Wild at Heart when Diane Ladd smears her face with lipstick until it’s devil-red and then screams at herself in the mirror, or of “Bob”’s look of total demonic ebullience in Fire Walk with Me when Laura discovers him at her dresser going through her diary and just about dies of fright. The bad guys in Lynch movies are always exultant, orgasmic, most fully present at their evilest moments, and this in turn is because they are not only actuated by evil but literally inspired(50): they have yielded themselves up to a Darkness way bigger than any one person. And if these villains are, at their worst moments, riveting for both the camera and the audience, it’s not because Lynch is “endorsing” or “romanticizing” evil but because he’s diagnosing it—diagnosing it without the comfortable carapace of disapproval and with an open acknowledgment of the fact that one reason why evil is so powerful is that it’s hideously vital and robust and usually impossible to look away from.

Lynch’s idea that evil is a force has unsettling implications. People can be good or bad, but forces simply are. And forces are—at least potentially—everywhere. Evil for Lynch thus moves and shifts, (51) pervades; Darkness is in everything, all the time—not “lurking below” or “lying in wait” or “hovering on the horizon”: evil is here, right now. And so are Light, love, redemption (since these phenomena are also, in Lynch’s work, forces and spirits), etc. In fact, in a Lynchian moral scheme it doesn’t make much sense to talk about either Darkness or about Light in isolation from its opposite. It’s not just that evil is “implied by” good or Darkness by Light or whatever, but that the evil stuff is contained within the good stuff too, encoded in it.

You could call this idea of evil Gnostic, or Taoist, or neo-Hegelian, but it’s also Lynchian, because what Lynch’s movies(52) are all about is creating a narrative space where this idea can be worked out in its fullest detail and to its most uncomfortable consequences.

And Lynch pays a heavy price—both critically and financially—for trying to explore worlds like this. Because we Americans like our art’s moral world to be cleanly limned and clearly demarcated, neat and tidy. In many respects it seems we need our art to be morally comfortable, and the intellectual gymnastics we’ll go through to extract a black-and-white ethics from a piece of art we like are shocking if you stop and look closely at them. For example, the supposed ethical structure Lynch is most applauded for is the “Seamy Underside” structure, the idea that dark forces roil and passions seethe beneath the green lawns and PTA potlucks of Anytown, USA.(53) American critics who like Lynch applaud his “genius for penetrating the civilized surface of everyday life to discover the strange, perverse passions beneath” and his movies are providing “the password to an inner sanctum of horror and desire” and “evocations of the malevolent forces at work beneath nostalgic constructs.”

It’s little wonder that Lynch gets accused of voyeurism: critics have to make Lynch a voyeur in order to approve something like Blue Velvet from within a conventional moral framework that has Good on top/outside and Evil below/within. The fact is that critics grotesquely misread Lynch when they see this idea of perversity “beneath” and horror “hidden” as central to his movies’ moral structure.

Interpreting Blue Velvet, for example, as a film centrally concerned with “a boy discovering corruption in the heart of a town”(54) is about as obtuse as looking at the robin perched on the Beaumonts’ windowsill at the movie’s end and ignoring the writhing beetle the robin’s got in its beak.(55) The fact is that Blue Velvet is basically a coming-of-age movie, and, while the brutal rape Jeffrey watches from Dorothy’s closet might be the movie’s most horrifying scene, the real horror in the movie surrounds discoveries that Jeffrey makes about himself—for example, the discovery that part of him is excited by what he sees Frank Booth do to Dorothy Vallens. (56) Frank’s use, during the rape, of the words “Mommy” and “Daddy,” the similarity between the gas mask Frank breathes through in extremis and the oxygen mask we’ve just seen Jeffrey’s dad wearing in the hospital—this kind of stuff isn’t there just to reinforce the Primal Scene aspect of the rape. The stuff’s also there to clearly suggest that Frank Booth is, in a certain way, Jeffrey’s “father,” that the Darkness inside Frank is also encoded in Jeffrey. Gee-whiz Jeffrey’s discovery not of dark Frank but of his own dark affinities with Frank is the engine of the movie’s anxiety. Note for example that the long and somewhat heavy angst-dream Jeffrey suffers in the film’s second act occurs not after he has watched Frank brutalize Dorothy but after he, Jeffrey, has consented to hit Dorothy during sex.

There are enough heavy clues like this to set up, for any marginally attentive viewer, what is Blue Velvet’s real climax, and its point. The climax comes unusually early,(57) near the end of the film’s second act. It’s the moment when Frank turns around to look at Jeffrey in the back seat of the car and says “You’re like me.” This moment is shot from Jeffrey’s visual perspective, so that when Frank turns around in the seat he speaks both to Jeffrey and to us. And here Jeffrey—who’s whacked Dorothy and liked it—is made exceedingly uncomfortable indeed; and so—if we recall that we too peeked through those close-vents at Frank’s feast of sexual fascism, and regarded, with critics, this scene as the film’s most riveting—are we. When Frank says “You’re like me,” Jeffrey’s response is to lunge wildly forward in the back seat and punch Frank in the nose—a brutally primal response that seems rather more typical of Frank than of Jeffrey, notice. In the film’s audience, I, to whom Frank has also just claimed kinship, have no such luxury of violent release; I pretty much just have to sit there and feel uncomfortable.(58)

And I emphatically do not like to be made uncomfortable when I go to see a movie. I like my heroes virtuous and my victims pathetic and my villains’ villainy clearly established and primly disapproved of by both plot and camera. When I go to movies that have various kinds of hideousness in them, I like to have my own fundamental difference from sadists and fascists and voyeurs and psychos and Bad People unambiguously confirmed and assured by those movies. I like to judge. I like to be allowed to root for Justice To Be Done without a slight squirmy suspicion (so prevalent and depressing in real moral life) that Justice probably wouldn’t be all that keen on certain parts of my character, either.

I don’t know whether you are like me in these regards or not…though from the characterizations and moral structures in the U.S. movies that do well at the box-office I deduce that there must be a lot of Americans who are exactly like me.

I submit that we also, as an audience, really like the idea of secret and scandalous immoralities unearthed and dragged into the light and exposed. We like this stuff because secrets’ exposure in a movie creates in us impressions of epistemological privilege, of “penetrating the civilized surface of everyday life to discover the strange, perverse passions beneath.” This isn’t surprising: knowledge is power, and we (I, anyway) like to feel powerful. But we also like the idea of “secrets,” “of malevolent forces at work beneath…” so much because we like to see confirmed our fervent hope that most bad and seamy stuff really is secret, “locked away” or “under the surface.” We hope fervently that this is so because we need to be able to believe that our own hideousnesses and Darkness are secret. Otherwise we get uncomfortable. And, as part of an audience, if a movie is structured in such a way that the distinction between surface/Light/good and secret/Dark/evil is messed with—in other words, not a structure whereby Dark Secrets are winched ex machina up to the Lit Surface to be purified by my judgement, but rather a structure in which Respectable Surfaces and Seamy Undersides are mingled, integrated, literally mixed up—I am going to be made acutely uncomfortable. And in response to my discomfort I’m going to do one of two things: I’m either going to find some way to punish the movie for making me uncomfortable, or I’m going to find a way to interpret the movie that eliminates as much of the discomfort as possible. From my survey of published work on Lynch’s films, I can assure you that just about every established professional reviewer and critic has chosen one or the other of these responses.

I know this all looks kind of abstract and general. Consider the specific example of Twin Peaks’s career. Its basic structure was the good old murder-whose-investigation-opens-a-can-of-worms formula right out of Noir 101—the search for Laura Palmer’s killer yields postmortem revelations of a double life (Laura Palmer=Homecoming Queen & Laura Palmer=Tormented Coke-Whore by Night) that mirrored the whole town’s moral schizophrenia. The show’s first season, in which the plot movement consisted mostly of more and more subsurface hideousnesses being uncovered and exposed, was a huge smash. By the second season, though, the mystery-and-investigation structure’s own logic began to compel the show to start getting more focused and explicit about who or what was actually responsible for Laura’s murder. And the more explicit Twin Peaks tried to get, the less popular the series became. The mystery’s final “resolution,” in particular, was felt by critics and audiences alike to be deeply unsatisfying. And it was. The “Bob”/Leland/Evil Owl stuff was fuzzy and not very well rendered,(59) but the really deep dissatisfaction—the one that made audiences feel screwed and betrayed and fueled the critical backlash against the idea of Lynch as Genius Auteur—was, I submit, a moral one. I submit that Laura Palmer’s exhaustively revealed “sins” required, by the moral logic of American mass entertainment, that the circumstances of her death turn out to be causally related to those sins. We as an audience have certain core certainties about sowing and reaping, and these certainties need to be affirmed and massaged.(60) When they were not, and as it became increasingly clear that they were not going to be, Twin Peaks’s ratings fell off the shelf, and critics began to bemoan this once “daring” and “imaginative” series’ decline into “self-reference” and “mannered incoherence.”

And then Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me, Lynch’s theatrical “prequel” to the TV series, and his biggest box-office bomb since Dune, committed a much worse offense. It sought to transform Laura Palmer from dramatic object to dramatic subject. As a dead person, Laura’s existence on the television show had been entirely verbal, and it was fairly easy to conceive her as a schizoid black/white construct—Good by Day, Naughty by Night, etc. But the movie in which Ms. Sheryl Lee as Laura is on-screen more or less constantly, attempts to present this multivalent system of objectified personas—plaid-skirted coed/bare-breasted roadhouse slut/tormented exorcism-candidate/molested daughter—as an integrated and living whole: these different identities were all, the movie tried to claim, the same person. In Fire Walk with Me, Laura was no longer “an enigma” or “the password to an inner sanctum of horror.” She now embodied, in full view, all the Dark Secrets that on the series had been the stuff of significant glances and delicious whispers.

This transformation of Laura from object/occasion to subject/person was actually the most morally ambitious thing a Lynch movie has ever tried to do—maybe an impossible thing, given the psychological text of the series and the fact that you had to be familiar with the series to make even marginal sense of the movie—and it required complex and contradictory and probably impossible things from Ms. Lee, who in my opinion deserved an Oscar nomination just for showing up and trying.

The novelist Steve Erickson, in a 1992 review of Fire Walk with Me, is one of the few critics who gave any indication of even trying to understand what the movie was trying to do: “We always knew Laura was a wild girl, the homecoming femme fatale who was crazy for cocaine and fucked roadhouse drunks less for the money than the sheer depravity of it, but the movie is finally not so much interested in the titillation of that depravity as [in] her torment, depicted in a performance by Sheryl Lee so vixenish and demonic it’s hard to know whether it’s terrible or a de force. [But not trying too terribly hard, because now watch:] Her fit of the giggles over the body of a man whose head has just been blown off might be an act of innocence or damnation [get ready:] or both.” Or both? Of course both. This is what Lynch is about in this movie: both innocence and damnation; both sinned-against and sinning. Laura Palmer in Fire Walk with Me is both “good” and “bad,” and yet also neither: she’s complex, contradictory, real. And we hate this possibility in movies; we hate the “both” shit. “Both” comes off as sloppy characterization, muddy filmmaking, lack of focus. At any rate that’s what we criticized Fire Walk with Me’s Laura for.(61) But I submit that the real reason we criticized and disliked Lynch’s Laura’s muddy bothness is that it required of us empathetic confrontation with the exact muddy bothness in ourselves and our intimates that makes the real world of moral selves so tense and uncomfortable, a bothness we go to the movies to get a couple hours’ fucking relief from. A movie that requires that these features of ourselves and the world not be dreamed away or judges away or massaged away but acknowledged, and not just acknowledged but drawn upon in our emotional relationship to the heroine herself—this movie is going to make us feel uncomfortable, pissed off; we’re going to feel, in Premiere magazine’s own head editor’s word, “Betrayed.”

I am not suggesting that Lynch entirely succeeded at the project he set for himself in Fire Walk with Me. (He didn’t.) What I am suggesting is that the withering critical reception the movie received (this movie, whose director’s previous film had won a Palme d’Or, was booed at the 1992 Cannes Film Festival) had less to do with its failing in the project than with its attempting it at all. And I am suggesting that if Lost Highway gets similarly savaged—or, worse, ignored—by the American art-assessment machine of which Premiere magazine is a wonderful working part, you might want to keep all this in mind.

Premiere Magazine, 1995

42. (Not even the Lynch-crazy French film pundits who’ve made his movies subject of more than two dozen essays in Cahiers du Cinema— the French apparently regard Lynch as God, though the fact they also regard Jerry Lewis as God might salt the compliment a bit…)

43. (Q.v. Baron Harkonen’s “cardiac rape” of the servant boy in Dune’s first act)

44. Here’s one reason why Lynch’s characters have this weird opacity about them, a narcotized over-earnestness that’s reminiscent of lead-poisoned kids in Midwestern trailer parks. The truth is that Lynch needs his characters stolid to the point of retardation; otherwise they’d be doing all this ironic eyebrow-raising and finger-steepling about the overt symbolism of what’s going on, which is the very last thing he wants his characters doing.

45. Lynch did a one-and-a-half-gainer into this pitfall in Wild at Heart, which is one reason the movie comes off so pomo-cute, another being the ironic intertextual self-consciousness (q.v. Wizard of Oz, Fugitive Kind) that Lynch’s better Expressionist movies have mostly avoided.

46. (=Master of Fine Arts Program, which is usually a two-year thing for graduate students who want to write fiction and poetry professionally)

47. (I’m hoping now in retrospect this wasn’t something Lynch’s ex-wife did…)

48. (E.g.: Kathleen Murphy, Tom Carson, Steve Erickson, Laurent Varchaud)

49. This critical two-step, a blend of New Criticism and pop pyschology, might be termed the Unintentional Fallacy.

50. (I.e. “in-spired,”=“affected, guided, aroused by divine influence,” from the Latin inpsirare, “breathed into”)

51. It’s possible to decode Lynch’s fetish for floating/flying entities—witches on broomsticks, sprites and fairies and Good Witches, angels dangling overhead—along these lines. Likewise his use of robins=Light in BV and owl=Darkness in TP: the whole point of these animals is that they’re mobile.

52. (With the exception of Dune, in which the good and bad guys practically wear color-coded hats—but Dune wasn’t really Lynch’s film anyway)

53. This sort of interpretation informed most of the positive reviews of both Blue Velvet and Twin Peaks.

54. (Which most admiring critics did—the quotation is from a 1/90 piece on Lynch in the New York Times Magazine)