#raymond durgnat

Quote

The films of David Lean crystallize the forlornness implicit in British Romanticism, so much so that his art has special problems. It's often said that nothing is more difficult to establish, in screen terms, than a negative, whether physical or spiritual: the absence of all those feelings which no-one even dreamed of feeling, though they might have. Lean's art is ultimately in this key. The love stories, slow as glaciers, look towards Antonioni's, yet never quite discover what seems to me to be their own theme. Even The Sound Barrier remains earthbound. Its plot asks a test pilot's wife (Ann Todd) to accept her aircraft manufacturer father's determination to sacrifice her husband in the service of aviation and she answers, predictably, yes. It loses, in gloomy interiors, the other half of its subject: a sense of duty and the intoxication of flying, above cloud-mountains, on pure oxygen.

Raymond Durgnat, A Mirror for England

#raymond durgnat#a mirror for england: british movies from austerity to affluence#david lean#michelangelo antonioni

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

“..style is essentially a matter of intuition. There is no possibility whatsoever of an ‘objective’, ‘scientific’ analysis of film style - or of ‘film’ content. It is worse than useless to attempt to watch a film with one’s intellect alone, trying to explain its effect in terms of one or two points of style.”

Raymond Durgnat, The Mongrel Muse

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

A bout de souffle (1960) By Michael Bump

A bout de souffle (1960)

A bout de souffle is a film about a perry criminal named Michel. Michel kills a police officer. While on the run he hides out in Paris with his American girlfriend named Patricia. Michel is infatuated with Patricia while she is reluctant to trust him. Patricia discovers that the police are after Michel when she becomes aware of his crime. She turns Michel in to the authorities and he is killed trying to run away. Most of the film is dialogue between Michel and Patricia. The film is exciting, and jazz music plays with the emotions of the scene.

A bout de souffle (Breathless) was directed by Jean-Luc Godard. Godard was inspired by the American Hollywood gangster films. Breathless was Godard’s first feature film. Many critics felt that Godard’s style of filming pushed the conventions of filmmaking at the time. Specifically, the handheld camera angels and “jump-cuts” for which he became famous for. Godard also pays homage to other directors that came before him. Being that it was Godard’s first film, he could not afford some of the equipment needed to shoot certain scenes. There is continuous dialogue throughout the movie which is reminiscent of other old gangster movies. During that time, many people embraced the film. Young directors looked at the film as a revolution to the film industry.

Noteworthy events that were happening in the world when this film was released was first, the entire world and the superpowers were focused on stopping communism and creating the most nuclear bombs. February of 1960 France tested its first nuclear bomb in the Sahara Desert. Another event that happened during 1960 was the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba. The world had only ended the second World War 15 years prior. There was massive hysteria around the world because people were worried about nuclear conflict with Russia and other communist powers. France and the United States were allies and it makes sense that the movie would have two people from those nations as love interests.

The film is movies fast. It almost feels like one long perpetual scene. I found myself rooting for Michel to get away from the police. I wanted him to make Patricia leave with him so they could start anew elsewhere. This film was good at making one root for the bad guy. It helps one understand that we all do not intend to do bad things, sometimes we just get caught up in the wrong situations. Michel does give off the notion that he has been a swindler for quite some time. It was just a matter of time before his evil deeds caught up with him. He falls in love with a woman and the almost successfully pulled her into his underworld. Godard wanted to show that you cannot run away from your problems, they will always catch up to you, no matter how well you hide. Michel was destined to be killed in the end. Patricia, the one he gave his heart to, was the one that turned him in. I think that was proof that she was in love with him.

This film is unconventional because it was unlike what people were used to seeing at that time in France and in the world of cinema. The style of filmmaking set the stage for future gangster-love sagas that came after it. This film was revolutionary to how action-romance films are made today.

There is a direct line through "Breathless" to "Bonnie and Clyde," "Badlands" and the youth upheaval of the late 1960s. The movie was a crucial influence during Hollywood's 1967-1974 golden age. You cannot even begin to count the characters played by Pacino, Beatty, Nicholson, Penn, who are directly descended from Jean-Paul Belmondo's insouciant killer Michel.

“À bout de souffle remains, as Raymond Durgnat suggested in 1988, "vivid witness to its era, in a manner transcending journalism and nostalgia alike". (1) Beyond all the surface icons of the hip late '50s – sunglasses, cool jazz, Seberg's endlessly imitated short haircut and tomboyish dress sense – there is something much deeper about that time which strikes a chord with today's audiences.”

“The original À bout de souffle may not seem half as disturbing, confronting or difficult as Godard's strange, nominal remake. But in 1960, its casual violence, disconcerting style, open-ended philosophising and raw invention had an immediate impact which was just as powerful and unsettling. These are qualities well worth rediscovering at any point in cinema history.”

http://www.filmcritic.com.au/reviews/a/aboutdesouffle.html

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

It’s fitting, in a way one almost never finds outside of art, that D. W. Griffith visited the set to watch this scene between his old Biograph players Lillian Gish and Lionel Barrymore—although he made Barrymore so nervous that Vidor finally had to ask him to leave. Isn’t this deathbed scene the American cinema’s last great burst of Griffithian sentiment? And doesn’t Duel in the Sun’s physical, lyrical, “pre-rational” psychology belong more to the silent cinema than the sound? The dying Belle’s struggling movement (across her bed toward her husband, paralyzed by his jealousy) anticipates Pearl’s dying movement (across the sand toward her demon lover, who is immobilized also, by his stomach wound). Vidor (who shot both sequences) reverses the movements: Belle going right to left, Pearl left to right.

#lillian gish#lionel barrymore#Gregory Peck#jennifer jones#Joseph Cotten#Duel in the sun#king vidor#raymond durgnat#scott simmon#1988#film review#film criticism#biography#essay

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Untitled Project: Robert Smithson Library & Book Club

[Durgnat, Raymond, Nouvelle Vague: The First Decade, 1963]

Oil paint on carved wood, 2017

#FILM#RAYMOND DURGNAT#DURGNAT#NOUVELLE VAGUE#NOUVELLE#VAGUE#THE FIRST DECADE#PAPERBACK#1963#AVAILABLE

1 note

·

View note

Photo

**** / TTT

Le Cercle rouge

Un film de Jean-Pierre Melville

À peine libéré de prison, un truand monte un fabuleux hold-up avec l’aide d’un gangster évadé et d’un ancien policier alcoolique. Le coup réussit. Le receleur, effrayé par l’importance du butin, leur recommande de s’adresser à un spécialiste. Ce dernier n’est autre que le commissaire chargé de l’enquête.

Policier-Suspense - France/Italie - 1970 - 140 min - couleurs

À propos

Pour son avant-dernier long-métrage, Jean-Pierre Melville renoue avec son genre de prédilection, le polar, auquel il a donné ses lettres de noblesse avec des films comme Le Doulos ou Le Samouraï. Brillant exercice de style où le cinéaste pousse à l’extrême son goût pour l’épure, Le Cercle rouge s’apparente à un ballet funèbre : Melville orchestre avec précision les déplacements de ses héros solitaires, malfrats et flic réunis par le destin, auxquels les acteurs Alain Delon, Yves Montand, André Bourvil (dont ce fut le dernier film) et Gian Maria Volonté prêtent admirablement leurs traits.

Aujourd’hui restauré en 4K à l’occasion de son 50e anniversaire, Le Cercle rouge reste le plus important succès public de Melville auquel de nombreux réalisateurs ont rendu hommage, de Jim Jarmusch à John Woo en passant par Michael Mann.

-----------------

In this brief tribute, John Woo praises Le cercle rouge and its tough romanticism: “Jean-Pierre Melville, a gentleman who believed in the philosophy (very much like the Asian philosophy) of the code of honor, could edit a film and work a camera like no other . . . His movies had a coolness and a style that separated him from other filmmakers of his time.”

"Critic Raymond Durgnat has said of Melvillian heroes that they are "cool cats that walk by themselves". Martin Scorsese, Quentin Tarantino and Michael Mann all acknowledge a debt to Melvillian codes and dynamics, and it is difficult to imagine revisionist noir without Melville." - Richard Armstrong (The Rough Guide to Film, 2007)

“An existentialist noir painted with the cold hues of grey, blue and green where the only warm touch is the red of blood, of death. Dialogues are reduced to a minimum as Melville displays his iconographic mastery throughout having condensed noir into an immanent palette where images are more expressive words.” - Mubi

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

One's favourite films are one's unlived lives, one's hopes, fears, libido .. they constitute a magic mirror with shadowy forms woven from one's shadow selves, one's limbo loves ..

Raymond Durgnat 1967

9 notes

·

View notes

Quote

This might have been a pacifist film if Hawkins and Holden had blown up the bridge while all the British prisoners were lined up on it, and even that wouldn't have proved anything, for the analogous depth-charge episode in The Cruel Sea doesn't lead to a pacifist reaction. You can't make an omelette without breaking eggs and you can't make war without scrambling a few guts. In America, even better class audiences, it appears, shriek 'Kill Him! kill him!' as Nicholson tries to save his bridge. Industrial hall audiences here don't shriek, and they feel sorry for him, but - he's got to go. For the anti-Nicholson audience, the doctor's cry - 'Madness! madness!' - refers to Nicholson's actions. For the pro-Nicholson audience, it condemns the destructiveness of war. For those who feel with both sides, even if they know that Nicholson must die, it underlies the tragic criss-cross of heroisms of which the greatest has gone wrong, in a convulsive and challenging way. Nicholson's own evolution is not particularised. Is the bridge, for him, a symbol of the unconquerable quality which he, and his men, can show? Is it an emblem of honour, beyond all question of usefulness? Or do its associations with engineering relate it to the long utilitarian-liberal-middle-class tradition with its pacifist leanings (the merchant skipper of Billy Budd is an earlier champion of the same creed)!

Raymond Durgnat, A Mirror for England

#raymond durgnat#a mirror for england: british movies from austerity to affluence#the bridge on the river kwai#david lean#charles frend#herman melville

8 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

For our latest Film Comment Free Talk, Claire Denis and Robert Pattinson joined us to discuss their singular film High Life, which graces the cover of our March-April issue. They discussed their approach to filmmaking, Denis's eye for physicality, encountering the taboo, working with a baby, and much more. As a thank you for watching this talk, enjoy $10 off an annual print subscription to Film Comment magazine, which also includes digital app access. Redeem here: http://bit.ly/2WSMyzE The Film Society of Lincoln Center is devoted to supporting the art and elevating the craft of cinema. The only branch of the world-renowned arts complex Lincoln Center to shine a light on the everlasting yet evolving importance of the moving image, this nonprofit organization was founded in 1969 to celebrate American and international film. Via year-round programming and discussions; its annual New York Film Festival; and its publications, including Film Comment, the U.S.’s premier magazine about films and film culture, the Film Society endeavors to make the discussion and appreciation of cinema accessible to a broader audience, as well as to ensure that it will remain an essential art form for years to come. Published since 1962, Film Comment magazine features in-depth reviews, critical analysis, and feature coverage of mainstream, art-house, and avant-garde filmmaking from around the world. Today a bimonthly print magazine and a website, the magazine was founded under the editorship of Gordon Hitchens, who was followed by Richard Corliss, Harlan Jacobson, Richard Jameson, Gavin Smith, and Nicolas Rapold. Past and present contributing critics include Paul Arthur, David Bordwell, Richard Combs, Manohla Dargis, Raymond Durgnat, Roger Ebert, Manny Farber, Howard Hampton, Molly Haskell, J. Hoberman, Richard Jameson, Kent Jones, Dave Kehr, Nathan Lee, Todd McCarthy, Jonathan Rosenbaum, Tony Rayns, Frank Rich, Andrew Sarris, Richard Schickel, Elliott Stein, Amy Taubin, David Thomson, Richard Thompson, Amos Vogel, Robin Wood, and many more. More info: http://filmlinc.org/ Subscribe: http://www.youtube.com/subscription_center?add_user=filmlincdotcom Like: http://facebook.com/filmlinc Follow: http://twitter.com/filmlinc

0 notes

Text

When Italian cinema meets its Celtic shadow: Castle of Blood (1964)

When Italian cinema meets its Celtic shadow: Castle of Blood (1964)

This is a slightly unusual guest post for Silent London, by Daniel Riccuito from the Chiseler, who promised me he could persuade us that 1964’s Castle of Blood/La Danza Macabra was essentially a silent film. What do you think?

Her appearance in 1960’s Black Sunday had already conquered him. And thereby imbued Raymond Durgnat’s now famous one-liner – “She is the only girl in films whose eyelids…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

A bout de souffle (1960)

A bout de souffle

“À bout de souffle remains, as Raymond Durgnat suggested in 1988, "vivid witness to its era, in a manner transcending journalism and nostalgia alike". (1) Beyond all the surface icons of the hip late '50s – sunglasses, cool jazz, Seberg's endlessly imitated short haircut and tomboyish dress sense – there is something much deeper about that time which strikes a chord with today's audiences.”

“The original À bout de souffle may not seem half as disturbing, confronting or difficult as Godard's strange, nominal remake. But in 1960, its casual violence, disconcerting style, open-ended philosophising and raw invention had an immediate impact which was just as powerful and unsettling. These are qualities well worth rediscovering at any point in cinema history.”

The critiques of the film suggest it is a gangster love story. Godard also proves to have a unique style of directing which catches the viewer’s attention.

http://www.filmcritic.com.au/reviews/a/aboutdesouffle.html

0 notes

Text

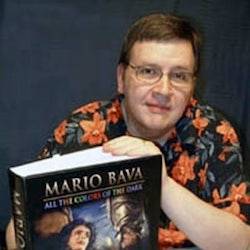

The Chiseler Interviews Tim Lucas

Born in 1956, film historian, novelist and screenwriter Tim Lucas is the author of several books, including the award-winning Mario Bava: All the Colors of the Dark, The Book of Renfield: A Gospel of Dracula, and Throat Sprockets. He launched Video Watchdog magazine in 1990, and his screenplay, The Man With Kaleidoscope Eyes, has been optioned by Joe Dante. He lives in Cincinnati with his wife Donna.

The following interview was conducted via email.

*

THE CHISELER: You're known for your longstanding love affair with horror films. Could you perhaps explain this allure they hold for you?

Tim Lucas: I suppose they’ve meant different things to me at different times of my life. When I was very young (and I started going to movies at my local theater alone, when I was about six), I was attracted to them as something fun but also as a means of overcoming my fears - I would sometimes go to see the same movie again until I could stop hiding my eyes, and I would often find out they showed me a good deal less than I saw behind my hands, so I learned that when I was hiding my eyes my own imagination took over. This encouraged me to look, but also to impose my own imagination on what I was seeing. Similarly, I remember flinching at pictures of various monsters in FAMOUS MONSTERS OF FILMLAND magazine, then realizing that, as I became able to stop flinching, to look more deeply into the pictures, I began to feel compassion for Karloff’s Frankenstein Monster and admiration for Jack Pierce’s makeup. You could say that I learned some valuable life lessons from this: not to make snap judgements, not to hate or fear someone else because they looked different. I should also point out that beauty had the same intense effect on me as ugliness, in those early days at the movies. I was as frightened by the glowing light promising another appearance by the Blue Fairy in PINOCCHIO as I was by Stromboli or Monstro the Whale. I also covered my eyes when things, even colors, became too beautiful to bear.

As I got older, I found out that horror, science fiction, and fantasy films often told the unpleasant truths about our world, our government, our politics, and other people, before such things could be openly confronted in straightforward drama. So I’m not one of those people who are drawn to horror by gore or some other superficial incentive; I have always responded to them because they made me aware of unpopular truths, because they made me a more empathic person, and because they sometimes encompass a very unusual form of beauty that you can’t find in reality or in any other kind of film.

THE CHISELER: I'm fascinated by what you term "a very specific hybrid of beauty that you can’t find in reality or in any other kind of film.” Please develop that point.

Tim Lucas: For example, the aesthetic put forward by the films of David Lynch... or Tim Burton... or Mario Bava... or Roger Corman... or Val Lewton... or James Whale... or F.W. Murnau. It's incredibly varied, really; too varied to be summarized by a single name, but it's dark and baroque with a broader, deeper spectrum of color. I’ll give you an example: there is a Sax Rohmer novel called YELLOW SHADOWS - and only in a horror film can you see truly yellow shadows. Or green shadows. Or a fleck of red light on a vine somewhere out of doors. It’s a painterly version of reality, akin to what people see in film noir but even more psychological. It might be described as a visible confirmation of how the past survives in everything - we can see new artists quoting from a past master, making their essence their own.

THE CHISELER: Your definition of horror, to me, goes straight to the heart of cinema as an almost metaphysical phenomenon. My friend and frequent co-writer, Jennifer Matsui, once wrote: "Celluloid preserves the dead better than any embalming fluid. Like amber preserved holograms, they flit in and out of its parameters, reciting their own epitaphs in pantomime; revenant moths trapped in perpetual motion." Do Italian directors have what I guess you can call special epiphanies to offer? If so, does this help explain your Bava book?

Tim Lucas: The epiphanies of Italian horror all arise from the culture that was inculcated into those filmmakers as young people - the awareness of architecture, painting, writing, myth, legend, music, sculpture that they all grow up with. It's so much richer than any films that can be made by people with no foundation in the other art forms, people who makes movies just because they've seen a few - and maybe cannot even be bothered to watch any in black and white. I imagine many people go into the film business for reasons having to do with sex or power rather than having something deep down they need to express. The most stupid Italian and French directors have infinitely more in their artistic arsenals than directors from the USA, because they are brought up with an awareness of the importance of the Arts. No one gets this in America, where we slash arts and education budgets and many parents just sit their children in front of a television. Without supervision, without a sense of context, they will inevitably be drawn to whatever is loudest or most colorful or whatever has the most edits per minute. And those kids are now making blockbusters. They make money, so why screw with the formula? When I was a kid, it was still possible to find important, nurturing material on TV - fortunately!

Does it explain my Bava book? I don't know, but Bava's films somehow encouraged and sustained the passion that saw me through the researching and writing of that book, which took 32 years. When my book first came out, some people took me to task for its presumed excess - on the grounds that “our great directors” like John Ford and Orson Welles, for all their greatness, had never inspired a book of such size or magnitude. I could only answer that my love for my subject must be greater. But the thing about the Bava book, really, was that - at that time - the playing field was pretty much virgin territory in English, and Bava as a worker in the Italian film industry touched just about everything that industry had encompassed. All of those relationships needed charting. It would have been an insult to merely pigeonhole him as a horror director.

THE CHISELER: I discovered your publication, Video Watchdog, back in 2000 when Kim's Video was something of an underground institution here in NYC. I mean, they openly hawked bootlegs. There was a real sense of finding the unexpected which gave the place a genuine mystique. Now that you've had some time to reflect on its heyday, what are your thoughts, generally, on VW?

Tim Lucas: It's hard to explain to someone who just caught on in 2000, when things were already very different and more incorporated. VIDEO WATCHDOG began in 1990 as a magazine, but before that it was a feature in other magazines of different sorts that began in 1986. At that time, I was reviewing VHS releases for a Chicago-based magazine called VIDEO MOVIES, which then had a title change to VIDEO TIMES. I pointed out to my editor that his writers were reviewing the films and not saying anything about their presentation on video, and urged him to make more of a mandate about discussing aspect ratios, missing scenes (or added scenes) and such. I proposed that I write a column that would start collecting such information and that column was called "The Video Watchdog.”

In 2000, VW's origins in Beta and VHS and LaserDisc had evolved to DVD and Blu-ray was on the point of being introduced, so by then most of the battles we identified and fought had already been won and assimilated into the way movies were being presented on video. But in our early days, my fellow writers and I - were making our readers aware of filmmakers like Bava, Argento, Avati, Franco, Rollin, Ptushko, Zuławski - and the conversation we started led to people seeking out these films through non-official channels, even forming those non-official channels, until the larger companies began to realize there was an exploitable market there. Our coverage was never limited to horror - horror was sort of the hub of our interest, which radiated out into the works of any filmmaker whose work seemed in some way paranormal - everyone from Powell and Pressburger to Ishiro Honda to Krzystof Kiesłowski.

Now that the magazine is behind me, I can see more easily that we were part of a process, perhaps an integral part, of identifying and disseminating some very arcane information and, by sharing our own processes of discovery, raising the general consciousness about innumerable marginal and maverick filmmakers. A lot of our readers went on to become filmmakers (some already were) and many also went on to form home video companies or work in the business.

I'm proud of what we were able to achieve, and that what were written as timely reports have endured as still useful, still relevant criticism. Magazines tend to be snapshots of the present, and our back issues have that aspect, but our readers still tell me that the work is holding up, it’s not getting old.

When I say "we," I mean numerous writers who shared my pretentious ethic and were able to push genre criticism beyond the dismissive critical writing about genre film that was standard in 1990. I mentioned this state of things in my first editorial, that the gore approach wasn’t encouraging anyone to take horror as a genre more seriously, and I do think horror became more respectable over the years we were publishing.

THE CHISELER: My own personal touchstone, Raymond Durgnat, drilled deep into genre — particularly horror films — while pushing back instinctively against the Auteur Theory. No critic will ever write with more infatuated precision about Barbara Steele, whose image graces the cover of your Bava tome. Do you have any personal favorites in that regard; any individual author or works that acted as a kind of Virgil for you?

Tim Lucas: I haven't read Durgnat extensively, but when I discovered him in the 1970s his books FRANJU and A MIRROR FOR ENGLAND were gospel to me. Tom Milne's genre reviews for MONTHLY FILM BULLETIN were always intelligent and well-informed. Ivan Butler’s HORROR IN THE CINEMA was the first real book I read on the subject, along with HITCHCOCK/TRUFFAUT - and I remember focusing on Butler’s chapter on REPULSION, an entire fascinating chapter on a single film, which I hadn’t actually seen. It showed me the film and also how to watch it, so that when it finally came to my local television station, I was ready to meet it head on. David Pirie’s books A HERITAGE OF HORROR and THE VAMPIRE CINEMA I read to pieces. But it was Joe Dante's sometimes uncredited writing in CASTLE OF FRANKENSTEIN magazine that first hooked my interest in this direction - followed by the earliest issues of CINEFANTASTIQUE, which I discovered with their third issue and for which I became a regular reviewer and correspondent in 1972. I continued to write for them for the next 11 years.

THE CHISELER: I was wondering how you responded to these periodic shifts in taste and sexual politics, especially as they address horror movies — or even something like feminist critiques of the promiscuity of rage against women evident all throughout Giallo; the fear of female agency and power which is never too far from the surface. Are sexism, and even homophobia, simply inherent to the genre?

Tim Lucas: None of that really matters very much to me. I've been around so long now, I can see these recurring waves of people trying to catch their own wave of time, to make an imprint on it in some way. For some reason, I find myself annoyed by newish labels like "folk horror" and "J-horror" because such films have been with us forever; they didn't need such identification before and they have only been invented to get us more quickly to a point, and sometimes these au courant labels simply rebrand work without bringing anything substantially new to the discussion. Every time I read an article about the giallo film, I have to suffer through another explanation of what it is - and this is a genre whose busiest time frame was half a century ago. Sexism and homophobia are things people generally only understand in terms of the now, and I don’t know how fair it is to apply such concepts to films made so long ago. Think of Maria’s torrid dance in METROPOLIS and all those ravenous young men in tuxedos eating her with their eyes. Sexist, yes - but that’s not the point Lang was making.

I don’t particularly see myself as normal, but I suppose I am centrist in most ways. I don’t bring an agenda to the films I write about, other than wanting them to be as complete and beautifully restored as possible. That said, I am interested in, say, feminist takes on giallo films or homosexual readings of Herman Cohen films because - after all - we all bring ourselves to the movies, and if there’s more to be learned about a film I admire, from outside my own experience, that can be precious information. I want to know it and see if I can agree with it, or even if it causes me to feel something new and unfamiliar about it.

My only real concern is that genre criticism tends to be either academic or conversational (even colloquial), and we’re now at a point where the points made by articles published 20 or more years ago are coming back presented as new information, without any idea (or concern) that these things have already been said. As magazines are going by the wayside, taking their place is talk on social media, which is not really disciplined or constructive, nor indeed easily retrievable for reference. There are also audio commentaries on DVD and Blu-ray discs. Fortunately, there are a number of good and serious people doing these, but even when you get very intelligent or intellectual commentators, they often work best with the movie image turned off, because it’s a distraction from what’s being said. Is that true commentary? I'm not an academic; I’m an autodidact, so I don't have the educational background to qualify as a true intellectual, and I feel left out by a lot of academic writing. I do read a good deal and have familiarity with a fair range of topics, so I tend to frame myself somewhere between the vox populist and academia. That's the area we pursued in VW.

THE CHISELER: David Cairns and I once published a critical appreciation of Giallo, using fundamentally Roman Catholic misogyny — and, to a lesser extent, fear of gay men — as an intriguing lens. For example, lesbians are invariably sinister figures in these movies, while straight women ultimately function as nothing more than cinematographic objects: very fetishized, very well-lit corpses, you might say.

Tim Lucas: See, I admire a lot of giallo films but it would never occur to me to see them through a lens. I do, of course, because personal experience is a lens, but my lens is who I am and I’ve never had to fight for or defend my right to be who I am. I have no particular flag to wave in these matters; I approach everything from the stance of a film historian or as a humanist.

There is a lot of crossdressing and such in giallo, but these are tropes going back to French fin de siècle thrillers of the early 1900s, they don't really have anything to do with homophobia as we perceive it in our time. In the Fantomas novels, Souvestre and Allain (the authors) used to continually deceive their readers by having their characters - the good and the evil ones - change disguises, and sometimes apparently change sexes.

I remember Dario Argento saying that he used homosexual characters in his films because he was interested in their problems. He seldom actually explored their problems, and their portrayal in his earliest films is… quaint, to be kind about it… but it was a positive change as time played out. I think the fact that Argento’s flamboyant style attracted gay fans brought them more into his orbit and the vaguely sinister gay characters of his early films become more three dimensional and sympathetic later on, so in that regard his attention to such characters charts his own gradual embracing of them. So in a sense they chart his own widening embrace of the world, which is surprising considering what a misanthropic view of the world he presents.

THE CHISELER: But Giallo is roughly contemporaneous to the rise of Second Wave Feminism. Like the Michael & Roberta Findlay 'roughies', this is not a fossilized species of extinct male anger we're talking about here. Women's bodies are the energy of pictorial composition; splayed specifically for the delectation of some very confused and pissed off men in the audience. I know of no exceptions. To me it makes perfect sense to recognize the ritualized stabbings, stranglings, the BDSM hijinks in Giallo as rather obvious symptoms of somebody's not-so-latent fear and hatred.

Tim Lucas: I think that’s a modernist attitude that was not all that present at the time. Once the MPAA ratings system was introduced in late 1968, all genres of films got stronger in terms of graphic violence and language, and suspense thrillers were no exception. At the time, women and gay people were feeling freer, freer to be themselves, and were not looking for new ways to be taken out of films, however they might be represented. Neither base really had that power anyway at that time, but at any rate it wasn’t a time for them to appear more conservative. That would come at a later period when they felt more assured and confident in their equality. Throughout the 1960s, even in 1969 films like THE WRECKING CREW and BEYOND THE VALLEY OF THE DOLLS, you can see that women are still playthings of a sort in films; there are starting to be more honest portrayals of women in films like HUD, but the prevailing emphasis of them is still decorative, so it makes sense that they would be no different in a thriller setting. There’s no arguing, I don’t think, that the murder scenes become more thrilling when the victim is a beautiful, voluptuous woman. It’s nothing to do with misogyny but rather about wanting to induce excitement from the viewer. If you look back to Janet Leigh’s character arc in PSYCHO, the exact same thing happens to her, but because she’s a well-developed character and time is given to explore that character and her goals and motivations, there is no question that it is a role women would want to play, even now. However, the same simply isn’t true of most giallo victims, which should not be seen as one of their rules but as one of their faults. In BLOOD AND BLACK LACE, I think Mario Bava shows us just enough of the women characters for us to have some investment in their fates - but when the giallo films are in the hands of sausage makers, you’re going to feel a sense of misogyny. It may be real but it may also be misanthropy or a more commercial mandate to pack more into a film and to sex it up. I should add that, because I’m not a woman or gay, I don’t bring personal sensitivities to these things, so I see them as something that just comes with the territory, like shoot-outs in Westerns. If you were to expunge anything that was objectionable from a giallo film, wouldn’t it be just another cop show or Agatha Christie episode? You watch a giallo film because, on some level, you want to see something with the hope of some emotional or aesthetic involvement, or with the hope of being outraged and offended. There is no end of mystery entertainment without giallo tropes, so it’s there if you demand that. Giallo films aren’t really about who done it, only figuratively; they are lessons in how to stage murder scenes and probably would not exist without the master painting of PSYCHO’s shower scene, which they all seek to emulate.

THE CHISELER: You mentioned Val Lewton earlier. Personally, I've never encountered anything like the overall tone of his films. There's always something startling to see and hear. Would you shed a little light on his importance?

Tim Lucas: He's an almost unique figure in film in that he was a producer yet he projected an auteur-like imprint on all his works. The horror films for which he's best known are not quite like any other films of their kind; I remember Telotte's book DREAMS OF DARKNESS using the word "vesperal" to describe the Lewton films' specific atmosphere - a word pertaining to the mood of evening prayer services, which isn't a bad way of putting it. I've always loved them for their delicacy, their poetical sense, their literary quality, and their indirectness - which sometimes co-exists with sources of florid garishness, like the woman with the maracas in THE LEOPARD MAN. In THE SEVENTH VICTIM, one shy character characterizes the heroine's visit to his apartment as her "advent into his world," and when I first saw it, I was struck by the almost spiritual tenderness and vulnerability of that description. Lewton was remarkable because he seems to have worked in horror because it was below the general studio radar, which allowed him to make extremely personal films. As long as they checked the necessary boxes, he could make the films he wanted - and I think Mario Bava learned that exact lesson from him.

THE CHISELER: I've always been fascinated by a question which is probably unanswerable: Why do you think it is that movies based on Edgar Allan Poe stories — even those films that only just pretend to sink roots in Poe, offering glib riffs on his prose at best — invariably bear fruit?

Tim Lucas: Poe's writings predate the study of human psychology and, to an extent, chart it - so he can be credited with founding a wing of science much like Jules Verne's writings were the foundation of science fiction and, later, science fact. Also, from the little we know of Poe's personal life, his writing was extremely personal and autobiographical, which makes it all the more compelling and resonant. It's also remarkably flexible in the way it lends itself to adaptation - there is straight Poe, comic Poe, arty Poe, even Poeless Poe. It helps too that a lot of people familiar with him haven't read him extensively, at least not since school, or think they have read him because they've seen so many Poe movies. The sheer range of approaches taken to his adaptation makes him that much more universal.

It also occurs to me that people are probably much more alike internally than they are externally, so the identification with an internal or first person narrator may be more immediate. But it's true that his work has inspired a fascinating variety of interpretation. You can see this at work in a single film: SPIRITS OF THE DEAD (1968), which I’ve written an entire book about. It’s three stories done by Roger Vadim, Louis Malle, and Federico Fellini - all vastly different, all terribly personal expressions of the men who made them.

THE CHISELER: Speaking of Poe adaptations, I've long thought it's time to confront Roger Corman's legacy; as an artist, a producer, an industrial muse, everything. Sometimes I think he's the single most important figure in cinema history. And if that's a wild overstatement, I could stand my ground somewhat and point out that no one person ever supported independent filmmakers with such profound results. It's as though he used his position at a mainstream Hollywood studio to open a kind of Underground Railroad for two generations of film artists. He gave so many artists a leg up in a business where those kinds of opportunities were never exactly abundant that it's hard to keep track. Entering the subject from any angle you like, what are your thoughts on Corman's overall contribution to cinema?

Tim Lucas: I can think of more important filmmakers than Corman, but there has never been a more important producer or mogul or facilitator of films. I said this while introducing him on the first of our two-night interview at the St. Louis Film Festival’s Vincentennial in 2011. He was largely responsible for every trend in American cinema during its most decisive quarter century - 1955 through 1980, and to some extent a further decade still, which bore an enormous influx of talent he discovered and nurtured. People talk about Irving Thalberg, Darryl F. Zanuck, Steven Spielberg, etc. - but their productions don’t begin to show the sheer diversity of interests that you get from Corman’s output. He has no real counterpart. I’ve spent a lot of the past 20 years musing on him, first as the protagonist of a comedy script I wrote with Charlie Largent called THE MAN WITH KALEIDOSCOPE EYES, which Joe Dante has optioned. A few years ago, I decided to turn the script into a novel, which is with my agent now. It’s about the time period before, during, and after the making of THE TRIP (1966). It's a comedy but one with a serious, even philosophical side.

You know, Mario Bava once described himself to someone as “the Italian Roger Corman.” It’s incredible to me that Bava would have said that, not because it’s wrong or even because he was a total filmmaker before Corman made his first picture, but because Bava has been dead for so long! He’s been gone now almost 40 years and Roger is still making movies. And he’s been making movies for the DTV market longer than anybody, so he sort of predicted the current exodus of new movies away from theaters to streaming formats.

THE CHISELER: Are there any other producers/distributors you'd care to acknowledge, anyone that you think has followed in what you might call Corman’s Tradition of Generosity?

Tim Lucas: No, I really think he is incomparable in that respect. I do think it’s important to note, however, that I doubt Roger was ever purely motivated by generosity of spirit. I don’t think he would put money or his trust in anyone merely as a favor. He’s a businessman to his core and his gambles have always been based on projects that are likely to improve on his investment, even if moderately. I have a feeling that the first dollar he ever made is still in circulation, floating around out there bringing something new into being. I also don’t think he would give anyone their big break unless they had earned that break already in some respect. And when he does extend that opportunity, he’s got to know that, when these people graduate from his company, he’ll be sacrificing their talent, their camaraderie, maybe even in some cases their gratitude. So yes, there is some generosity in that aspect - but he also knows from experience that there are always new top students looking to extend their educations on the job. I wish more people in the film business had his selflessness, his ability to recognize and encourage talent. It may be his greatest legacy.

THE CHISELER: You introduced me, many years ago, to Mill of the Stone Women — I'll end on a personal note by thanking you and asking: Would you share an insight or two about this remarkable gem, particularly for readers who may not have seen it?

Tim Lucas: MILL OF THE STONE WOMEN was probably my first exposure to Italian horror; I saw it as a child, more than once, on local television and there were things about it that haunted and disturbed me, though I didn't understand it. Perhaps that's why it haunted and disturbed me, but the image of Helfy's hands clutching the red velvet curtains stayed with me for decades (a black and white memory) until I got to see it on VHS - I paid $59.95 for the privilege because my video store told me they would not be stocking it. It's a very peculiar film because Giorgio Ferroni wasn't a director who favored horror; the "Flemish Tales" that it's supposedly based on is non-existent, a Lovecraftian meta-invention, and it's the only Italian horror filmed in that particular region in the Netherlands. It looks more Germanic than Italian. I’m tempted to believe Bava may have had a hand in doing the special effects shot, which look like his work, but they might also have been done by his father Eugenio, as he was also a wax figure sculptor so would have been good to have on hand. He seldom took screen credit. So it's a film that has stayed with me because it's elusive; it's hard to find the slot where it belongs. It's like an adult fairy tale, or something out of E.T.A. Hoffmann. I can’t tell you how many hours I’ve wasted, trying to find another movie with the unique spell cast by that one.

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

La Boheme makes its best sense through an Americanized viewing of this Paris: Mimi’s all-night hard work and fatal self-sacrifice is the harshest puritanical way out. His puritan streak notwithstanding, Vidor was too transcendent an optimist to look on Mimi’s death without being irritated by its masochism.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Durgnat and Perkins on Hitchcock’s Psycho

Alfred Hitchcock

Psycho

1960

Raymond Durgnat

Inside Norman Bates

From Films and Feelings 1967

V.F. Perkins

The world and Its Image

Film as Film

A different approach from the beginning was taken by these critics. Durgnat described the film bit by bit explaining his theories and ideas as he went. Perkins uses the filmmaking aspects as a way in, and as a continuing theme.

Although both agreeing on some aspects of the film such as the sexual nature of the of the shower scene and the resulting contrast between pleasure and horror from the audience.

Durgnat took the focus to Norman and the cleaning he did afterwards, reflecting on the relationship between him and his mother and how Marion threatened it.

Perkins spent longer on the shower scene itself, instead of character aspects the focus was on the use of montage, symbolism and the resulting reaction from the audience.

The montage to lengthen and give the audience time to react was interesting, the symbolism described very Freudian.

In fact both essays linked many aspects back to sexual nature.

Durgnat’s focus on character relationships occasionally drawing conclusions to theories that I find difficult to understand. Particular when talking about Norman watching through the peephole, ‘his spying on Marion represents a movement towards normality and freedom’. Not only do I disagree with this but even the idea of trying justifying the voyeurism doesn’t sit well with me. This is probably due to the social ideals of now vs when the piece was written.

Perkins tends to follow the editing aspect throughout this essay, beginning with disagreeing with the theory of montage. I found this curious not only because I adore editing but because Hitchcock believed heavily in the theory of montage. It’s a very fascinating way to begin an essay on a Hitchcock film.

Although not discounting montage all together, later explaining it’s significance in the shower scene. Perkins’ conclusion of editing in general tends to be that the editing alone isn’t what makes Psycho a great film, although it is a major focus of this essay.

Durgnat’s focus on characters, especially that of Norman Bates regarding his behaviour, and the perceived audience reaction. Which again would change over time and the meaning and significance of films change over time.

This essay was a bit dry compared to Perkins. The relatively chronological order and constant reflection on character motivation became old quickly.

While both critics are writing on the same text, the resulting essays are very different both in the topics covered and conclusions drawn. Even in the similarity’s the expression used by Durgnat’s and Perkins’ are distinct from each other

0 notes