#minna dubin

Text

[“In addition to the gender imbalance of societal perceptions of anger, dads partnered to women also need to consider that because they are not usually the primary parent, the cultural expectations for them are drastically lower than they are for mothers.

Motherhood is touted as the top of the mountain for women, “the best job in the world.” With that kind of pressure to not only become mothers, but to love it and do it right (or at least perform the role of happy, perfect mom to continue the scam of Motherhood), raging at our families feels like the ultimate taboo. It is the opposite of what we were taught mothers are supposed to be like. Raging is not gentle, not kind, not nurturing, not affectionate, and not supportive. In essence, raging is anti-Mother. But raging is not anti-father. In Western culture, fathers get to be anything they want. They can be kind or domineering (or both!) because fathers aren’t wholly defined by their fatherhood. It is not considered their highest calling. Fatherhood is a side gig. Dads are not in the midst of the greatest identity battle of their lives, disoriented and flailing as they become new selves. Fathers get to stay who they are when they have kids, whereas moms are just Mother.

So, if raging is anti-Mother, and Mother is all we are, then all we are is bad.

Under the patriarchal institution of motherhood, all the visible and invisible labor mothers do (picking the kids up from school, meal planning, researching summer camps, scheduling the dad’s next colonoscopy) is in service to the interests of men. Each one is a tiny gift of freedom the mother grants the father. Because she has done the labor, he doesn’t have to. While fathers may have their own laundry lists of personal gripes, their entire lives have not been usurped to serve the interests of women. If dads could take in these nuances, and understand that mom rage is an experience rooted in misogyny and the disempowering gender dynamics of patriarchy, they would see that mom rage is much more complicated than moms getting “too mad.” And, hopefully, this understanding can expand dads’ compassion for the mothers they love, minimizing the distance between them. A father who gets it might even reach for the mother’s spinning body, pull her from the shame spiral, and rock her gently, his body a safe mother place.”]

minna dubin, from mom rage: the everyday crisis of modern motherhood, 2023

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review: Mom Rage by Minna Dubin

Minna Dubin really lets it rip in this jarring review of motherhood. She says many of the things most moms experience, but are afraid to say out loud. Her hold nothing back approach made me fall instantly in love with her book.

While at points I laughed out loud, other points I couldn't stop nodding my head in agreement.

Dubin mixes her own personal accounts with facts and statistics to back up her claims and shows she is not just writing on emotion, but has thoroughly researched what she is sharing.

Mom Rage is an un-sugarcoated look at motherhood and the many many emotions that come into play mentally, with children but also family, and especially spouses. Bravo to Minna Dubin for her transparency and having the courage to share her deepest thoughts and saying what so many are thinking on a daily basis.

See more of Ashley's recs

Check out Mom Rage

#mom rage#minna dubin#nonfiction#parenting#motherhood#book recommendations#book recs#bookblr#ashleyrecs#LCPL recs

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Dubin is not really imagining the freedom to be more than “one thing” but the freedom to run away from this bind and into the arms of nothing—no fixed roles, no lasting responsibilities. This is a negative freedom that does not expand one’s sense of self so much as shrink it to pure potentiality. But you cannot live in potentiality forever. If spouses and children do not get in the way, then time will. In its purest and most personal moments, Dubin’s rage seems like grief for the future, which is available to her children in a way it will never again be available to her.

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The Mother Trap: Everyone’s Talking About ‘Mom Rage,’ But What Is it?” by Merve Emre

“On September 13, 2019, Minna Dubin, a mother in Berkeley, California, published a brief, confessional essay in the Times’ parenting section titled “The Rage Mothers Don’t Talk About.” …What explained her rage? Her son would not get into the car, or eat the foods that she wanted him to eat, or let her brush his teeth. He bit other children. He ignored her. She yelled at him, threatened him, squeezed his arms, threw him in his crib, and wanted badly to hit him. She ate too many sweets and wandered the house, ashamed and lonely, whispering to stop herself from laying her hands on him: “Don’t touch him, don’t touch him, don’t touch him.”

But she was reluctant to speak to anyone, even her husband. “Mother rage is not ‘appropriate,’” she wrote. “As if mother rage equals a lack of love. As if rage has never shared a border with love.” She sensed that her reactions were excessive, but she made no real effort to understand. Understanding was not the point of her essay. The point was to unleash the primal scream of a mother who had regressed—spectacularly, obscenely—into a tantruming child, not unlike the three-year-old who had spurred her rage in the first place.

The tantrum had its desired effect; immediately, Dubin started to receive messages from mothers around the world. They confided that they, too, struggled with uncontrollable anger and that her story “made them feel less alone,” she reported. Her essay went viral when the Times republished it, in April, 2020, weeks after the surge in Covid-19 cases prompted many governments to close schools. Parents struggled to work from home and care for their children, who were suddenly underfoot all the time; households everywhere grew isolated yet overcrowded, overstimulated yet bored, and exceedingly agitated. “Between stay-at-home orders, Covid-19 health concerns, financial instability (or fear of it), and police violence against Black people, it is no surprise that mothers are experiencing intensified rage,” Dubin wrote, in a follow-up essay that was published in the Times on July 6, 2020, with the headline “‘I AM GOING TO PHYSICALLY EXPLODE’: MOM RAGE IN A PANDEMIC.”

The artlessness of Dubin’s essays made them tremendously gripping—so gripping as to deflect certain intellectual and ethical questions that readers might have asked of her central concept, “mom rage.” It was a term that Dubin had adapted from a 1998 essay by Anne Lamott, called “Mother Rage: Theory and Practice.” Whereas Lamott’s essay was a self-deprecating, mock-scholarly comedy about parenting, Dubin presented mom rage as a solemn social diagnosis. But what was “mom rage,” exactly? How did it differ from related diagnoses, such as anger issues or impulse-control disorders? More sensitive questions suggested themselves, too.

…“Mom Rage: The Everyday Crisis of Modern Motherhood” (Seal Press, 2023) is Dubin’s book-length effort to grant mothers the absolution that many of them seek. “What if the conclusion I, and the moms who were writing to me, had come to—that each of us must be ‘the worst mother in the world’—was untrue?” she asks. “What if we were normal mothers reacting to unjust circumstances? What if mom rage were a widespread, culturally-created phenomenon, and not just a personal problem?” Since around 2016, popular works of American feminist nonfiction have often fallen into two overlapping genres: books that reclaim women’s anger for personal and political emancipation (“Rage Becomes Her,” “Burn It Down,” “Good and Mad,” “Eloquent Rage”) and books that popularize Marxist feminist analyses of domestic and emotional work as forms of unwaged labor (“Fed Up,” “All the Rage,” “Essential Labor,” “Emotional Labor,” “Labor of Love”).

The first half of “Mom Rage” squats at the intersection of these genres. The anger of mothers is overdetermined by the “white supremacist, homophobic, classist, ableist, xenophobic, transphobic, misogynistic, capitalist patriarchy,” Dubin writes. The capitalist patriarchy props up the ideology of “capital-M Motherhood,” which “tells mothers we must throw ourselves full throttle into our mothering job—researching, planning, contacting, scheduling, overseeing, washing, tidying, folding, driving, thanking, inviting, hosting, cooking, preparing, and sharing.” Rage is simultaneously “a natural reaction to being systematically stripped of one’s power” and a source of “power in its potential for individual and cultural change.” The remedies Dubin proposes range from state-subsidized child care to communal parenting, art-making (“I recommend the transformative power of creative practice,” she writes), and non-normative sexual arrangements (“I also recommend queerness”).

Dubin’s claims and prescriptions are, by now, staples of pop-feminist nonfiction. Such personal essays and polemics are built on the foundational arguments of an earlier generation of feminists—among them, Silvia Federici, Mariarosa Dalla Costa, and Selma James—who, in the nineteen-seventies, argued that capitalism’s emphasis on waged work outside the home occluded the unwaged work of housewives and mothers. It is a measure of how influential such theorizing has become that this proposition, once radical, is almost received opinion among a new crop of cultural critics. But, by the same token, the newer books—call them “feminish”—engage only sparingly with the original sources. Reading paraphrases of paraphrases of paraphrases, one starts to feel as if there is something a little hollow and shiftless about the ease with which phrases such as “white supremacist, homophobic, classist, ableist, xenophobic, transphobic, misogynistic, capitalist patriarchy” are trotted out. We get the right words, strung together like marquee lights, but not the structural analysis that puts them in relation to one another.

…Although rage is the passion that gets top billing in the book, it is made to share the stage with another feeling: shame. Shame is simultaneously the cause and the effect of rage. “Society punishes angry women and shames mothers who step out of their domestic box of caregiving,” Dubin writes. If the shame of not living up to the ideals of capital-“M” Motherhood causes mothers to rage, then it also causes them to stay silent, lest they articulate a greater and deeper shame: that they really are a “bad mom.” “Shame” and its variants appear with greater frequency as “Mom Rage” shifts into its second half, which looks to the genre of self-help to break the “Mom Rage Cycle” and, with it, the “Shame Spiral.” “Self-isolation is a key component of the Shame Spiral for me,” Dubin writes. “I am so deep in my own sorrow and self-hatred after a rage, I have a hard time reaching out to friends.”

Dubin’s presupposition is that it is desirable to banish shame from the scene of parenting, and that once we do we may move “toward creating a more equitable and joyful motherhood.” But surely this depends on the cause of shame and to what ends shame is, or can be, directed. “Shame is itself a form of communication,” the queer theorist Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick writes. Sedgwick, who was also one of the great theorists of shame, saw the relationship between mother and child as a model for the isolation (and, more surprisingly, the possibility of intimacy) that shame can produce. The hot blush or the averted gaze that arises when a mother shouts at her child are “semaphores of trouble,” the outward signs of a breach in their intimacy that has caused them to shrink from each other and into their innermost loneliness. At the same time, these visible responses are invitations for the mother and child to repair their relationship. They can make it anew with an apology or an embrace—and, in doing so, they can make themselves anew, with a deeper understanding of their identities as both linked and separable beings.

…In the book, her son has a name, Ollie, and he is no longer the Everychild she previously presented. Dubin introduces him through his diagnoses: a sensory-processing disorder, fine and gross motor delays, food rigidity, and autism-spectrum disorder. Once we learn this, her mom rage reads differently, as the reaction of a parent facing more than run-of-the-mill challenges. Alarmed by Ollie’s uncomprehending reactions and emotional blankness—“His silence infuriated me,” she writes—she screams and tries to frighten him. Staging these scenes allows her to capture him through his physical responses to her. We learn about his “chubby, tear-streaked face” and the “doughy hugs'' he offers to appease his mother. “Between genetics and autism, Ollie never really had a chance,” she writes, and, although the sentence is specific to his challenges with potty training, it is difficult not to hear in it a more general lament or judgment.

“Moms of sick, disabled, or neurodivergent kids all have increased stress levels that make them more prone to mom rage,” Dubin observes. Such stress cannot be underestimated, but the specificity of Dubin’s experience presents a problem for her thesis. Even if we accept her argument that “white supremacist, capitalist patriarchy” shapes the conditions of contemporary motherhood in profoundly unjust ways, it is clear that this is not the whole story of her rage. The book fails to universalize a particular predicament, and, in strenuously attempting to do so, turns into an exercise in ill-advised candor. There are times when one wants to shield both Dubin and her son from such exposure, and times, too, when one feels rage toward Seal Press, which should have used better editorial discretion with a first-time author. Aptly enough, the fortunes of Seal Press echo, in a way, the current mainstreaming of feminist theory in nonfiction publishing. Founded by two feminists in a Seattle garage in 1976, it has now, after a sequence of corporate acquisitions, ended up as an imprint of Hachette, one of the world’s largest trade publishers, which is apparently happy to pass off the book as a “groundbreaking work of reportage” by dressing it up in the flimsiest fashions of pop feminism.

There are scenes scattered throughout “Mom Rage” when Dubin’s gaze widens beyond the mother’s point of view. In one of them, Dubin’s son and daughter have been tussling over the bathroom door, her on one side of it, him on the other. He pushes too hard, and she falls back and hits her head. Dubin is about to bellow but then stops. Instead, she looks closely at her son: “I recognize regret and sadness in his wet, almond eyes, mirror images of mine. I take a slow breath and see that his heart is just like my heart—full of self-punishment. I open my arms to him and say no words at all.” She closes the chapter by describing a piece of scrap paper with two sentences written on it that, for a time, she kept in her purse to remind her of this moment. The first sentence read, “Ollie is a four-year-old boy, and he is good.” The second read, “I am a thirty-five-year-old woman, and I am also good.”

The mother and child’s silent embrace is the ideal image of intimacy renewed. It is the closest Dubin comes in the book to the tender mood of the photograph, and it will soften even readers who have hardened to her extravagant performance. And yet it is difficult to accept it as proof of understanding. At such a pivotal moment, one would expect the language of recognition to be slightly more imaginative and precise, not his eyes are “mirror images of mine” or “his heart is just like my heart.” How clearly can a writer see anyone or anything—her children or the social and political contours of motherhood—when she perceives everything through the haze of moral cliché? “My boy IS good! I wanted to scream. He’s GOOD!” “Please SEE him! See his good self,” Dubin pleads. It is wrenching to witness how much she needs others to affirm that both she and her son are good, instead of understanding how they can be good to, or good for, each other. And it is unsettling to realize that she is incapable of seeing him or herself clearly—that careless prose can narrow the terrain on which a person encounters others and interrogates her own desires.

Dubin never relinquishes the language of morality. She cannot; her book has promised universal absolution and universal absolution it must deliver. “You are a good mom,” she assures the reader in the book’s last line. But to liberate parents from shame like this is every bit as moralizing an act as scolding them would be. Both acts situate the writer on a plane of judgment above the reader, reducing the reader to an extension of the writer’s values. The question “How can she be sure that I am a good mother?” can only be answered with another question: “Does she care who I am?” The writer gets to play out a fantasy of the infinitely benevolent mother by casting the reader in the role of the child, desperate for forgiveness. Yet what the reader really seeks from the writer, and what the child seeks from his mother, is not a moral sentence. It is an ethical point of view—the attentiveness and the curiosity borne of the clear-eyed recognition of both self and others.”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

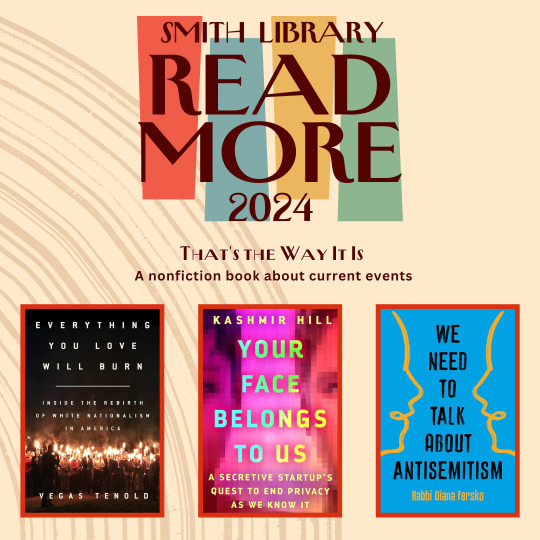

Read More 2024

That's the Way It Is

A non-fiction book about current events.

Biography

A Promised Land by Barack Obama

Non-Fiction

Your Face Belongs To Us by Kashmir Hill

We Need to Talk About Antisemitism by Rabbi Diana Fersko

Bloodbath Nation by Paul Auster

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt

Escape From Freedom by Erich Fromm

While Idaho Slept by Appelman

Everything You Love will Burn by Vegas Tenold

The Climate Book by Greta Thunberg

To Dye For by Alden Wicker

Chaos Kings by Scott Patterson

Going Infinite by Michael Lewis

Kings of Crypto by Jeff John Roberts

Outrage Machine by Tobias Rose-Stockwell

Burn it Down by Maureen Ryan

Tyranny of the Gene by James Tabery

Mom Rage by Minna Dubin

Quitting: A Life Strategy by Julia Keller

1 note

·

View note

Text

october 2023

03 - Mom Rage: The Everyday Crisis of Modern Motherhood by Minna Dubin (3/5) 📙🌈📚

04 - It Happened One Summer by Tessa Bailey (3/5) 📘

05 - Small Game by Blair Braverman (2/5) 🎧📘🌈

13 - Witch of Wild Things by Raquel Vasquez Gilliland (3/5) 📘🌈📚

17 - The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson (2/5) 📘🌈📚⏸

24 - The Blackthorn Key by Kevin Sands (3/5) 📘📚

26 - Should I Not Return: The Most Controversial Tragedy in the History of North American Mountaineering! by Jeffrey Babcock (2/5) 📙📚

27 - The Drift by C. J. Tudor (3/5) 🎧📘

#bb reads#bb reads 2023#🅱 = botm#🎧 = audiobook#🗯️ = comic book / graphic novel#📘 = fiction#📙 = non fiction#🌈 = lgbtq+ inclusive#📚 = borrowed#💱 = translated#🎯 = 2023 tbr#⏸ = reread

1 note

·

View note

Text

0 notes

Text

[“It can be difficult for people raised as girls to express rage when we’ve been taught from very early on that it is in our best interest to suppress our anger. It is culturally acceptable for women to be sad, not angry. In one study on gender, anger, and the workplace, the participants conferred higher status to sad female employees than to angry ones. For men the opposite was true. Men, particularly white men, are rewarded and forgiven for their anger, while women are penalized and blamed.

Ceci, the mestiza paralegal, now lives in Los Angeles with her husband, five-year-old son, and twenty-two-year-old stepdaughter. She described herself using the exact language of a woman who was taught by the culture not to value or express her anger: “I’m a people pleaser. I don’t rock the boat. I go along with everything, do what people tell me.” This is the path of being a good girl, a good woman, and eventually a good mother. Lifelong gendered learning teaches people raised to be women to push down anger and any feelings in the “sub-anger” ballpark, such as annoyance, irritation, and frustration. I imagine this emotional push-down like the carnival game whack-a-mole. Each time an uncomfortable or unpleasant anger-related feeling pops up—whack!—women automatically bang it with a big-headed mallet, sending it back beneath the surface.

Like the rage itself, this game of anger whack-a-mole is an international phenomenon for women. In Korea, there is a culture-related anger syndrome called hwa-byung. It translates literally to “illness of fire” and mostly affects working-class middle-aged housewives, who have chronically suppressed anger stemming from strict gender roles, gender-based inequality, and patriarchal family structures. In traditional Latin American folk medicine, it is believed that holding onto certain emotions can cause physical illness. In Northeast Brazil, the term engolir sapos translates to “swallowing frogs,” and is mostly used by women to refer to the suppression of anger and irritation, and the pressure to tolerate unfair treatment without complaint.

Cheryl, the Black civil rights lawyer who internalizes her mom rage, is practiced at playing whack-a-mole with her anger: “I’m good at repressing things. So, a little problem, I repress it, and it gets packed on top of all the other things that make me mad, until there’s no way to untangle it. It’s just this huge tangle of anger that I’m trying to disassociate from all the time.” In our present-day culture of busy, intensive motherhood, stuffing down unpleasant emotions can be a matter of practicality. Minutes are a precious resource, and airing every frustration is a time expense that modern mothers cannot afford. Emails must be sent, dinner needs to get into bellies, and bodies need to snuggle under covers. But the perceived time-saver of the Emotional Whack-a-Mole phase is a mirage. Every time a mom suppresses her angry feelings, as she’s been taught to do her entire life, she is pushing them onto an ever-growing pile of anger inside her. Eventually, the pile will topple.”]

minna dubin, from mom rage: the everyday crisis of modern motherhood, 2023

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey MAMArtist* MINNA DUBIN!

What are the ages of your child(ren), and where do you live?

My kids are 10 and 6, Berkeley, CA.

How do you describe your art practice?

Roller-coaster-y. I work in waves -- I either have the muse or I don't. And when I do, it's the most amazing feeling to have the words just rush out of my fingers. And when I don't, I am kind of sad with myself and grumpy. Oh maybe you mean, what is my art? I'm a writer--mostly memoir, some journalism, some poetry, some fiction. I write a lot with other writer friends, either at cafes or on Zoom. I will make up any excuse not to write, so other people help me to stay accountable to getting my butt in the chair.

Who is your artistic crush?

Dorothy Allison, her work transports and heals me.

What is a superpower Mother+Artists have?

For me, parenting and work feed and enhance each other. I have never-ending inspiration for my work from my family and the trials and joys of mothering. And my writing gives me a safe place to work through so much of what I'm feeling and experiencing in my mothering life. It's a symbiotic feedback loop.

You have something exciting coming up! PLEASE SAY MORE ABOUT IT!

My first book Mom Rage: The Everyday Crisis of Modern Motherhood comes out on September 19th. I've been working on it ever since my New York Times articles on mom rage went viral in 2020. I interviewed 50 mothers from across the country and around the world, and I also tell my own story of anger in motherhood. It's really the first comprehensive book on the what, why, and how of mom rage. I did so much research, but it's based in story, which felt important to me because I'm a memoirist--a storyteller, really--not an academic. I'm hopeful it will provide moms (and the people who love them) with relief and some ways forward.

How did motherhood directly, indirectly, oppositionally or integrally influence this project?

Hah! I wouldn't have had these experiences if it weren't for motherhood! Becoming a mother to my son just blew the roof off of me. I was so spun trying to figure out how to give myself what I needed while also trying very hard to be a "good mother." And those two things are in opposition in our society. A "good mother," according to current ideas about mothering, is one who basically has no needs and so she disappears herself. This book is kind of the culmination of a decade of examining the culture of motherhood in America and thinking deeply about my mothering experience.

What are you currently reading or listening to that is giving you thoughts, feelings and reactions?

I've been listening to the Serial Podcast's show The Retrievals, about a fertility clinic at Yale. Even though I only had one miscarriage, and was able to conceive pretty easily, I am very interested in infertility as a feminist frontier. I think birthing people's right to access free and safe fertility treatment should be part of the bodily autonomy fight, right next to abortion and gender-affirming medical care and treatments.

Any message for Mother+Artists reading this?

This book came from an essay that came from a list that was part of a funky public art project I did for 3 years. I wrote lists about motherhood and turned them into art pieces, then hung them up in public places. I did it because it was a way to write but in early motherhood I needed to make something with my hands. My advice to do whatever artistic acts you can manage that bring you joy, even if they are weird and quirky and quick. Everything can be artistic practice. And we never know where it will lead.

BEST LINKS to find you and your work!

Preorder Link for Mom Rage!

Mom Rage Book Tour Dates!

All my published writing including the NYT Mom Rage pieces

Check out the 150 lists from #MomLists

Follow me on Instagram

*Each month The MAMAs features a Mother+Artist and their work in the world. Thank you Melissa!

0 notes

Photo

"‘I Am Going to Physically Explode’: Mom Rage in a Pandemic" by BY MINNA DUBIN via NYT Parenting https://ift.tt/3iG8DgX

0 notes

Text

The Rage Mothers Don’t Talk About

By BY MINNA DUBIN

Mothers are supposed to be patient martyrs, so our rage festers beneath our shame.

Published: April 16, 2020 at 12:47PM

from NYT Parenting https://ift.tt/2RDMu6H

via IFTTT

0 notes

Link

By BY MINNA DUBIN from NYT Parenting https://ift.tt/3iG8DgX

0 notes

Text

NYT article #homeschool "‘I Am Going to Physically Explode’: Mom Rage in a Pandemic" by Minna Dubin via https://t.co/rJ6U883lqL

NYT article #homeschool "‘I Am Going to Physically Explode’: Mom Rage in a Pandemic" by Minna Dubin via https://t.co/rJ6U883lqL

— Homeschool Base (@HomeschoolBase) July 6, 2020

from https://twitter.com/HomeschoolBase

Respond! July 06, 2020 at 05:17AM

0 notes

Text

The Rage Mothers Don’t Talk About

Mothers are supposed to be patient martyrs, so our rage festers beneath our shame.

“[My son] can provoke me into a state of something similar to road rage. I have felt many times over the years that I was capable of hurting him … [T]he myth of maternal bliss is so sacrosanct that we can’t even admit these feelings to ourselves.” Anne Lamott, “Mother rage: theory and practice,” Salon.com

The rage lives in my hands, rolls down my fingers clenching to fists. I want to hurt someone. I am tears and fury and violence. I want to scream and rip open pillows, toss chairs and punch walls. I want to see my destruction — feathers floating, overturned furniture, ragged holes in drywall.

When I get mad like this around my 3-year-old son, I have to say to myself, like a mantra, “Don’t touch him, don’t touch him, don’t touch him.” Touching him with this rage coursing through me only ends in my shame, and my son’s shock, and what else I do not know; only time will reveal that. I have never hit him, but the line between “hitting” and “not hitting” is porous. In this “not hitting” gray area there are soft arms squeezed too tight, a red superhero cape (Velcro-clasped around his neck) forcefully yanked off, a child picked up and thrown into his crib. For me it is better not to touch at all. Only a few years ago, I remember judging a mother on the bus for smacking her child. Now I have only empathy for her. Mother rage can change you, providing access to parts of yourself you didn’t even know you had.

Mother rage is not “appropriate.” Mothers are supposed to be martyr-like in our patience. We are not supposed to want to hit our kids or to tear out our hair. We hide these urges, because we are afraid to be labeled “bad moms.” We feel the need to qualify our frustration with “I love my child to the moon and back, but....” As if mother rage equals a lack of love. As if rage has never shared a border with love. Fearing judgment, we say nothing. The rage festers and we are left under a pile of loneliness and debilitating shame.

The shame is as bad as the rage and just as damaging. I am afraid of my actions. Of myself. I know — know — in the deepest part of myself that this yelling, this terrifying anger is not O.K. My little boy is unfolding, blossoming more into his glorious self with each passing day. I am afraid I am destroying his bloom with my rage.

I get furious with my son for all kinds of reasons: for running away from me down the sidewalk; for not getting in the car; for not letting me brush his teeth; for spitting at, hitting and biting other children at school; for ignoring me; for eating only five monochromatic foods. In my calmer moments, I can access the wisdom of distance. I remember that his behavior is age-appropriate, that all kids test limits. But in the moment, I’m consumed by what a brat he is being. Fury does not welcome wisdom.

In this red place, I yell at my son so hard my voice becomes a growl. I want him to react. To cry or look scared. To feel my fury. I turn into a tantruming child, stomping along with each word. I slam doors, smack my hand on the counter. “Goddamn it! Jesus Christ! You’re making me insane!” I threaten forever-timeouts, no supper. I take away videos, treats, toys, privileges. When I get through with him the house will be barren, the dusty outlines where the furniture used to be the only indication that a nice family once lived there.

[How to discipline your child without yelling or spanking]

One evening, my partner, working late, calls me after a particularly rage-filled day. I am watching a movie on our bed, while finishing off all the sweet things in the house. “How was the day?” he asks. My voice is tired and small. “It was hard,” I say, trying not to cry, and I detect an edge in his voice when he asks me what happened. He knows, I think. I can’t tell him everything. He will hate me. He won’t trust me. Our son is his baby, too. I wouldn’t trust me either.

Mostly, I keep my rage between my son and me. My partner’s presence mitigates my outbursts, but sometimes my fury bubbles over and he witnesses it. He’s an even-keeled guy, so when he says, “You need to figure this out now,” I know I need to get help beyond ice cream and deep breathing.

I start working with a life coach. He assigns me a section of Daniel Goleman’s book “Emotional Intelligence.” Goleman cites the work of University of Alabama psychologist Dolf Zillmann, who discovered that the physiological effects of rage can last for days, and that rage builds on rage. Repeated aggravations — “a sequence of provocations” — can dramatically increase anger, so that by the third or fourth rage trigger, the person is reacting on a level 10 in response to a misplaced key or a dropped spoon.

The example Goleman uses is (wait for it!) a mother in a grocery store with a 3-year-old and a baby. The 3-year-old is begging his mother to buy things, pulling food off shelves and not listening when she orders him to put it back. Then the baby drops a jam jar, which shatters on the floor. The mother explodes: yells, slaps the baby, slams the cereal box down and angrily zigzags the cart toward the exit.

Of course Goleman chose this story to illustrate Zillmann’s “sequence of provocations.” Motherhood is relentless provocation! And yet we are expected to be saintly and patient, to lovingly hold and care for our babies, even at their most challenging. To dwell so serenely in the state Anne Lamott calls “the myth of maternal bliss,” that we don’t yell or curse, and we certainly don’t become enraged or violent.

Looking for help, I join a 12-week anger-management group for mothers. The facilitator encourages us to add “tools” to our “toolboxes.” We practice deep breathing through one nostril at a time, and we read about “happy parenting.” The most important part, for me, is the mirror provided by the circle of tired, sad mothers. One woman is divorced. One has a toddler at home and a 3-month-old on her breast. Only one participant is a dad; apparently, there is no class for dads who rage. Another mom admits that she wants to throw her child across the room, and the rest of us have forgiven her before she has finished her sentence. We all nod, as our bodies flood with relief that the rage has not singled us out.

Couples therapy, individualized therapy, life coaching, anger management for mothers — I have been working on my mother rage. I have not yet found the golden ticket to serenity, but I have noticed that when I manage to exercise, make art and eat healthy food, I have a longer fuse. In toolbox lingo: These things fill up my patience cup. Unfortunately, as a working mom with a small child I am not swimming in spare time, and cooking, running and unpaid hobbies often fall to the bottom of the to-do list.

I am trying, though. And failing. And sometimes succeeding. I count every small win — today I got mad and clenched my fists but kept my voice really calm! Each day I begin again: breathing in his sweet little-boy smell when he crawls into our bed and I wrap my arms around him, enveloping his body in mine; and by the end of the day, whispering to myself, “Don’t touch him, don’t touch him, don’t touch him.”

Minna Dubin, a writer, public artist and performer in the Bay Area, is working on a collection of essays about motherhood.

Kin Leung is a Marriage & Family Therapist, MFT practicing in the San Francisco Bay area. Kin specializes in helping couples overcome struggles related to infidelity, intimacy, miscommunication, mistrust, and parenting. Kin's kind, thoughtful and compassionate approach to marriage counseling San Francisco helps guide couples to a calmer and safer space to explore issues and move forward in a more productive manner.

0 notes