#ming dynasty women

Text

Hi Producer (正好遇见你) Infodump

Disclaimer: I have no idea about the accuracy of the information shared in the drama, I'm merely transcribing for future reference purposes. Proceed with caution!

.

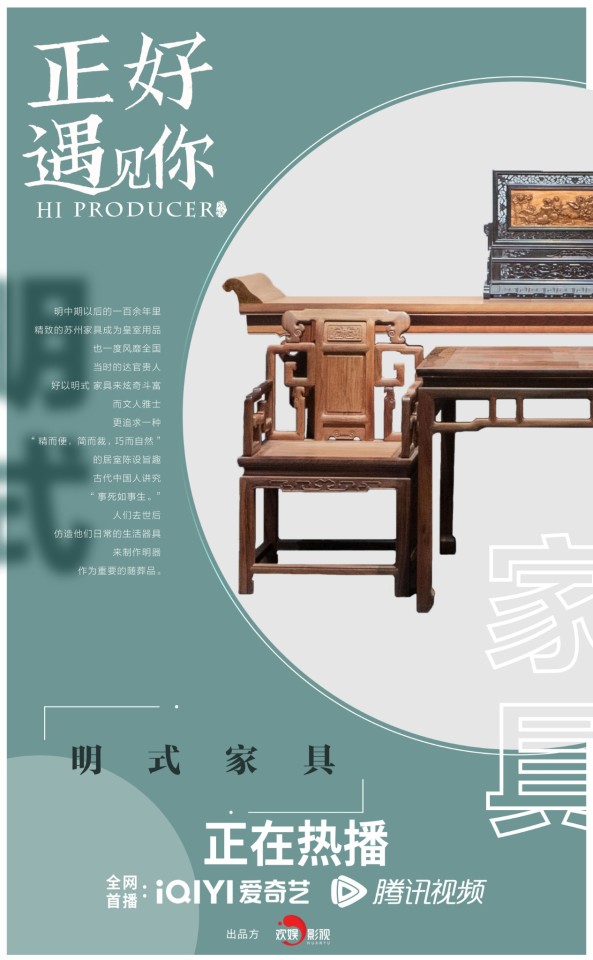

Ep 32-33: Ming-Style Carpentry and Landscaping

Canglang Pavillion and Ke Yuan

Known for the unique landscaping art, before you enter the garden of Canglang Pavilion there is a pond surrounding the garden. Inside it, rocks are the main element of the scenery. You'll be greeted by a hill. Pavilion is right on top of it. At the foot of the hill is a pond. The body of water is connected to the mountain with a winding corridor. Southeast of the fake mountain is Mingdao Hall. It's the main building of the garden. In 2000, the UNESCO listed it as a world heritage site.

Keyuan garden isn't very big. It's only 0.741 acres. But it has a long and rich history. The characteristics of Keyuan can be described with five lines, which are, "An azure pond in the middle, a spacious construction, a full-circle corridor, a bright and clear view, a tranquil and vast yard."

Landscaping art boasts so many details. The buildings, rocks, plants, and ponds that form the scenery come from nature and transcend nature. It's an extraordinary fusion of picturesque scenery and craftsmanship. This goes perfectly with the saying, "The garden owner's disposition is represented and told by the well-arranged landscape."

In spring, you can appreciate the blooming crabapple. On a summer day, you can enjoy the coolness under a pipa tree. On autumn nights, you can hear raindrops hitting the banana leaves. And in winter, you can enjoy the warmth of a fire while admiring the plum blossoms. It's such a serene and relaxing life.

youtube

Ming era Furniture and Carpentry

The unearthed cultural relics in Wang Xijue's tomb from the late Ming Dynasty, such as garments, jewelry, accessories, embroidery, furniture used as funeral objects, and items used in daily life not only reflect the advanced level of craftsmanship and technology at that time but also shed light on the political, economic and cultural conditions of that period.

When the powerful official Yan Shifan's property was confiscated, a total of 657 beds made of marble, mother-of-pearl inlay, and colored lacquer were collected, along with 7,444 items of chairs, cabinets, and tables. This shows officials and the rich at the time preferred using Ming-style furniture as a symbol of great wealth.

The scholars sought a refined and simplified living environment that was skillfully natural in its arrangement. A miniature Ming-style furniture set discovered in the joint tomb of Wang Xijue, a Senior Grand Secretary, and his wife. These things are so tiny and delicate. Chinese in ancient times thought of death as another life. After the passing, replicas of items used in life were buried as funeral objects. When Wang Xijue's tomb was unearthed, this set of miniature funeral objects was placed on his coffin. There is a hanger, a wooden basin, and an alcove bed. There is a stand for the basin and so many kitchen wares. You can find almost anything you need in real life.

The palaces in Hengdian World Studio are one-to-one replicas, but they aren't made with traditional mortise and tenon joints.

Suzhou Museum recreated a Ming-style study based on the literature "Chang Wu Zhi".

.

Tanyangzi and the Alcove Bed

She's a legendary young woman from Ming Dynasty, whose proposed future husband died and the in-laws demanded that she live the rest of her life in seclusion as a widow. Then she apparently cultivated Taoism and ascended at mere age of 23, which resulted in an entire niche religion of people worshipping her.

It's a very interesting story for sure, when you consider how Ming Dynasty was the most restrictive towards women and how this girl stood her ground and found her salvation in her own way. History says that Tanyangzi's death might have been from a hunger strike or poisoning from an elixir. But in the "Miscellaneous Morsels from Zaolin", Tan Qian wrote Madam Zhu was able to marry her daughter to a scholar from Shaoxing with a hefty dowry. And she claimed that her daughter had ascended in daylight.

It's irrelevant if she truly attained immortality or played a trick to get the society forcing their norms on her off of her back. Either way, you go Gui'er!!

I tried looking up sources in English but could only find some old articles by some Western universities, I think you can get a better summary by even just machine translating the Baidu Baike page which is linked below.

Hi Producer narrates this story by incorporating her mother's unconditional love and support into it and provides a "realistic explanation".

The alcove bed is a type of large bed that came into being in the late Ming Dynasty. It is also known as the eight-step bed and the platform bed. The alcove bed came in two styles. The colonnade style and the enclosed colonnade style. A small "room" is built on top of a four-post bed with three low panels to form a cloister-like structure. A shallow colonnade of about two to three chi is installed at the front of the bed, with a footrest in the centre. The left and right sides are used to place small cabinets, tables, stools, and even dressing tables. It is a clever and intricate design. The hardwood alcove bed requires a lot of materials and manual labor. It is a luxurious and exquisite piece of furniture. It was popular in the Jiangnan area during the Ming and Qing dynasties. Many wealthy families in the area would have such a bed made for their daughters the moment they were born to be included as part of their dowry, taking years to complete. To have a piece of furniture encompass parental love is also a unique way the Chinese show love.

The segment is timestamped below immeadietely followed by the Documentary part:

youtube

.

More Hi Producer posts

#cdrama#chinese drama#正好遇见你#Hi Producer#chinese history#Ming dynasty#ming dynasty women#chinese furniture#chinese gardens#carpentry#landscaping

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Consort Duan 端妃 (duān fēi),of the Cao Clan, was a Ming Dynasty concubine of the Jiajing emperor. Lady Cao was born in Wuxi, modern Jiangsu Province. She was one of JIajing Emperor’s favourite consorts. In 1536, Lady Cao gave birth to the emperor's first daughter Zhu Shouying, Princess Chang'an. The same year, she was promoted to Imperial Concubine Duan. In 1537, Imperial Concubine Duan was promoted to Consort Duan. She gave birth to the emperor's third daughter in 1539, Zhu Luzheng, Princess Ning’an. The Jiajing emperor was a notoriously short-tempered, harsh man with many enemies, and in late 1542 several maids, despairing of his cruelty, attempted to assassinate him. This event has come to be known as the palace incident of the renyin year [1542] (renyin gong bian) or the incident of the palace maids. That night, the emperor had fallen asleep in the chambers of Consort Duan, who withdrew with her attendants, leaving him alone. The palace maids entered the room, tied a knot in a silk curtain cord, and slipped it around his neck; they also began to stab him in the groin with their hairpins. Someone among them panicked, Empress Fang was alerted, and a physician was summoned. The emperor remained unconscious until the following afternoon and, acting on his behalf, Empress Fang ordered that all of the women involved be executed immediately. As the attack had taken place in Consort Duan's palace, the empress determined that she had conspired with the palace women and sentenced her to death by slow slicing in the marketplace. The Jiajing held Empress Fang responsible for the death of his favorite, Consort Duan, thinking that she couldn’t have been involved, and when the empress was trapped in a palace fire in 1547 he refused to agree to her being rescued, leading to her death.

Source: Lee, Lily Xiao Hong; Wiles, Sue. Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women, Volume II (University of Hong Kong Libraries Publications), Zhang Tingyu, (1739). History of Ming, Volume 114, Historical Biography 2, Empresses and Concubines 2.

Happy belated birthday @misssylvertongue!

#women in history#historyedit#cao duanfei#曹端妃#consort duan of the cao clan#ming dynasty#16th century#misssylvertongue#sorry this took so long!#hope you like it <3#her life was so sad#the fact that so many women died while jiajing lived to abuse even more women is so tragic#*mine

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

Abridged History of Qing Dynasty Han Women’s Fashion (part 1: Late Ming & Shunzhi Era)

Intro

Finally got around to writing this series! Couple notes before we begin. I will only discuss civilian fashion and not court dress because 1) Qing court dress is well documented and there are plenty of other people/blogs/articles that explain it better than I ever could 2) court dress doesn’t really count as fashion because it serves ceremonial/religious/political purposes and is not supposed to change. The overwhelming majority of English language information about Qing Dynasty clothing is about court dress and Manchu women’s fashion, so I will be doing a disservice to the era if I continued that line of discussion. It should be noted that most literature on court dress and Manchu women’s fashion is not flawless either; court dress is often flattened to “dragon robes” by white historians despite it not being a legitimate fashion history term, and much information about “Qing Dynasty” Manchu fashion is really about that of the early 20th century, the Republican era. That is outside the scope of discussion for this series. Instead, I would like to shed some light on the life and times of Han women’s fashion during the Qing, something strictly kept out of the canon of Chinese fashion history until very recently.

Before we jump into it, we need some context. Prior to the establishment of the Qing Dynasty, China was ruled by the Ming Dynasty under ethnically Han (majority ethnicity in China nowadays) rulers since 1368. A collection of Jurchen tribes from what is now northeastern China and parts of Siberia, who later called themselves the Manchus, conquered China in 1644. In order to solidify their power, the new Manchu rulers forced Han Chinese men to adopt Manchu style clothing and hairstyles, but Han women were allowed to continue wearing Han style clothing, which is why the second half of the 17th century appears to be the continuation of the late Ming Dynasty aesthetic.

However, the early Qing was undeniably distinct from the Ming Dynasty, and I will not tolerate anybody calling clothes from this era “Ming style”. It could potentially be considered hanfu, as it was worn by Han women exclusively----something up for the community to decide----but it definitely did not belong to Ming Dynasty proper. Although in the 1640s and 50s some resistance forces in the south (dubbed “Southern Ming”) were still around, it’s not really worthwhile to make the distinction for womenswear, so let’s place it under Qing Dynasty for convenience. I have berated 18th century erasure quite frequently and passionately in the past (and it’s often extended to the 17th century as well), if you have seen any of those posts you would know that Qing Han women’s fashion prior to the 19th century is routinely mislabelled as Ming because it didn’t adhere to 20th century stereotypes about the “Manchuness” of Qing clothing and supposed Chinese backwardness in the colonial imagination of the time. Because of this reason, please do not be surprised if any of the images from the first couple posts of this series appear to be depicting what is commonly considered “Ming Dynasty hanfu”; they do not, they were from the Qing, plain and simple. It’s often simply because people don’t pay enough attention to the dating of artworks.

I will use emperors’ reign years as a guide for eras in this series because oftentimes that’s the most accurate dating that exists for artworks (many are unclear as to the exact year/decade they were made in), though I would recommend using exact dates instead of emperors wherever possible.

Fashion of the Ming-Qing transition

Han women’s fashion of the very early Qing had significant overlap and continuity with the late Ming. I’m not very knowledgeable on the minutiae of Ming Dynasty clothing so do add/correct anything. The standard ensemble for Han Chinese women was the 袄裙 aoqun (alternatively named 衫裙 shanqun) ensemble consisting of a robe and a skirt. In the 1620s and 30s, the cut of the robe was extremely generous, the hem hitting about knee length and the sleeves almost touching the ground. The sleeves of this era (and often throughout Chinese history) were longer than that of the length of the wearer’s arms, meaning that the wearer is required to grab the cuffs of the sleeves in order to facilitate the use of their arms. Many consider this inconvenient nowadays, but keep in mind that these robes with huge sleeves were made for wealthy people who hired servants and didn’t need to do physical labor. Working class people wore shorter, tighter sleeves that could also be held up by a garter.

The robe had a fitted tall standing collar, as opposed to the cross collar popular in previous centuries. The standing collar in the 1620s and 30s was soft, unstiffened and closed by two 子母扣 zimukou, metal clasp buttons, one at the bottom of the collar where it touched the bodice and one at the middle of the collar. Collars with only one button also existed, and these would be worn folded over. Gold or silver piping on the collar began to be popularized on the collar. Robes were closed at the side under the right armpit, commonly with tie strings. The placket forms a straight diagonal line from the collar to under the armpit. In the 17th century, robes were commonly plain and unicolor, with only brocade/embroidery in the same color. When decorative patterns were used, they were frequently in a repetitive arrangement of small clusters of motifs. Light pastel colors or white were very popular. Undergarments whose cuffs could be seen on the outside were commonly red, providing a contrasting flash of color to the otherwise light and plain ensembles.

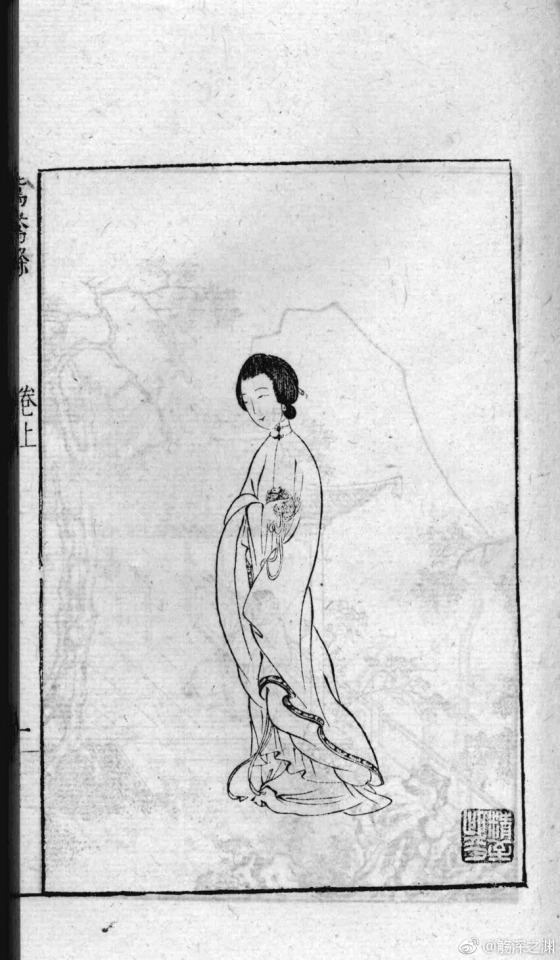

Illustration from the late Ming novel 鸳鸯绦, showing the large sleeves popular at the time.

Late Ming women’s robe from the Confucius Estate collection.

The skirt was usually of 马面 mamian construction, basically two pleated pieces of fabric with two unpleated sections at the middle each, called 裙门 qunmen, that are sewn onto a waistband with one unpleated section overlapping, creating a wrap skirt. It has ribbons attached to each end of the waistband and was closed by wrapping the skirt around the waist and tying with the ribbons. Throughout much of the Ming Dynasty, mamian skirts were decorated using 裙襕 qunlan, a horizontal row of gold brocade or embroidery across the skirt, whose placement and widths varied depending on the trends of the decade. In the 1620s and 30s, skirts became increasingly simple, and plain white skirts were all the rage. Decorative features like qunlan were frequently relegated to formal dress.

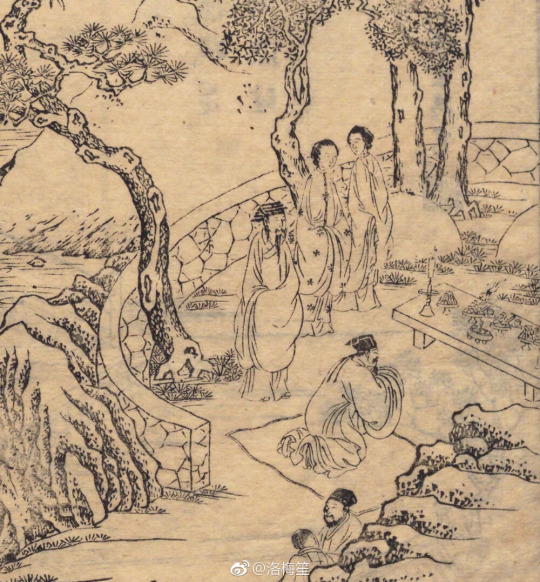

Illustration for the Chongzhen era novel 醋葫芦. The repetitive decorative patterns could be seen on the robe of the lady to the left.

Women’s hairstyle of this period is referred to as 三绺梳头 or “hair in three sections”, where the front of one’s hair would be divided into three sections, top, left and right, which would then be tied and coiled at the back, sometimes forming an elongated end at the bottom called a 燕尾 or “swallow tail”.

Late Ming/early Qing painting showing two fashionable women. The flash of red from the under robe is visible.

Beside the skirt and robe, women could layer a 披风 pifeng on top of the robe. These were equally generous in cut as the robe but had a 直领 zhiling, parallel collar, and were closed by tie strings or bigger decorative clasp buttons at the center front. It usually had a wide facing at the collar, which in the 1620s and 30s were often plain and in the same color as the garment.

Mid 17th century portrait. This lady is wearing a plain red robe with gold buttons and piping, blue pifeng and plain white mamian skirt.

By the 1640s, the width of the sleeves had become smaller, and hairstyles became gradually fuller and more voluminous at the top, beginning the transition to the Kangxi era. The diagonal placket on robes began to be replaced by closures at the center front, often held together by tie strings.

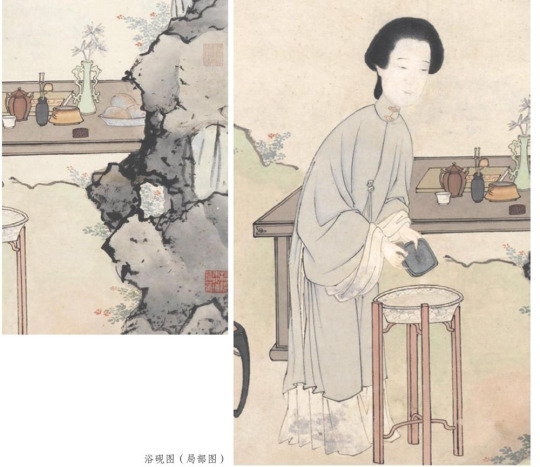

Section of 浴砚图 by 蓝瑛 Lan Ying and 徐泰 Xu Tai, 1659. We can see the center front closure with tie strings instead of the diagonal placket closing under the right armpit popular in previous eras.

Around this time, robes made of sheer fabric were being popularized as informal loungewear for warmer weather. Sheer robes were not proper enough to be worn outside, but we can catch a glimpse of these robes along with the undergarments beneath in romantic paintings with a domestic setting. The principle women’s undergarment for the upper body remained a 主腰 zhuyao, a tube top-like garment that provided bust support. It could have shoulder straps and was usually closed at the back with tie strings, though closures with cloth buttons became increasingly common throughout the Qing.

Shunzhi era painting series by Sun Huang (the cover image for this post is from the same series), showing a lady and her maids in lounging clothes, the zhuyao visible under the sheer robe.

--

I’m not as knowledgeable about the earlier parts of the Qing Dynasty as the later ones, so as always feel free to correct or add anything to this post :))

#qing dynasty#17th century#ming dynasty#shunzhi era#chongzhen era#abridged history of qing dynasty han women's fashion#chinese fashion#hanfu#fashion history

199 notes

·

View notes

Text

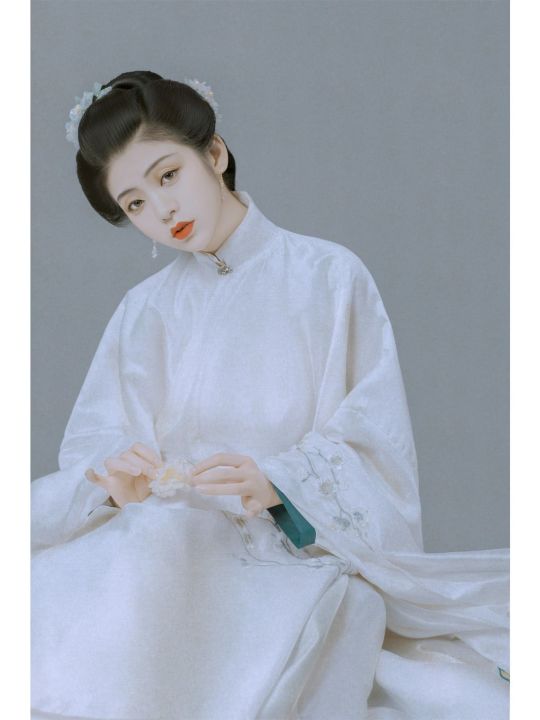

Elegant Ming Dynasty Hanfu

From Zuitangfeng Hanfu Photography Studio

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

tag yourself

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

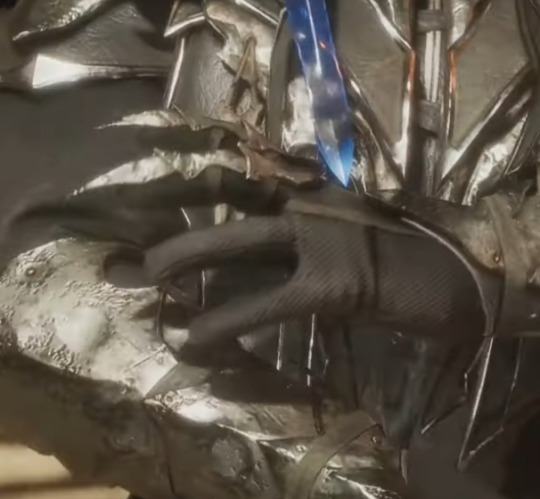

A Hermit a Day, Day 4: FalseSymmetry

#mulberry's art tag#hermitadaymay#hermitaday art#falsesymmetry#falsesymmetry fanart#this is inspired off of ming dynasty armor 👍#bc women in armor is <3 <3 <3

11 notes

·

View notes

Quote

The Jiajing Emperor (1507–1567) was the twelfth emperor of the Chinese Ming dynasty. Every day he would drink a concoction called ‘red lead’, made from the menstrual blood of virgins that he believed would prolong his life. The girls were aged between eleven and fourteen and were treated so cruelly that in 1542 they attempted to assassinate the emperor. Though he was badly injured, the emperor survived, and his attackers, along with their families, were sentenced to death by slow slicing. The emperor continued to drink red lead for the rest of his life. Twat.

A Curious History of Sex (Kate Lister)

... Girls aged 13–14 were kept for this purpose, and were fed only mulberry leaves and rainwater. Any girls who developed illnesses were thrown out and they could be beaten for the slightest offence. ...

wiki: Palace plot of Renyin year

#A Curious History of Sex#Kate Lister#ch: Period Drama: A History of Menstruation#history#Jiajing Emperor#China#Ming dynasty#Palace plot of Renyin year#women#menstruation#abuse#books#quotes#V

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

fuckin. blue and pink pirate mommy be upon ye

#still not playing genshin but im gonna double dip and draw all the women bc i think theyre cool#i do think beidou and the white bitch that runs the ming dynasty should fuck though#idk if thats popular opinion or not#sherbo art#genshin impact#beidou#genshin beidou#genshin fanart#genshin impact art#genshin impact fanart

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Interview with Alice Poon, author of Tales of Ming Courtesans

New Post has been published on https://china-underground.com/2020/04/30/interview-with-alice-poon-author-of-tales-of-ming-courtesans/

Interview with Alice Poon, author of Tales of Ming Courtesans

Born and raised in Hong Kong, Alice Poon steeped herself in Chinese poetry and history, Jin Yong’s martial arts novels, and English Literature in her school days.

This early immersion has inspired her creative writing. Always fascinated with iconic but unsung women in Chinese history and legends, she cherishes a dream of bringing them to the page. She is the author of The Green Phoenix and the bestselling and award-winning non-fiction title Land and the Ruling Class in Hong Kong. She now lives in Vancouver, Canada and devotes her time to writing historical Chinese fiction.

Official Site | Instagram | Twitter

Where does the interest in the lives of these three fascinating female figures come from?

When I did research in 2014 for a subplot minor character Chen Yuanyuan for my earlier historical novel The Green Phoenix (published in 2017), I accidentally stumbled on Liu Rushi’s biography, titled An Ulterior Biography of Liu Rushi, written by the eminent historian Chen Yinke, who lauded her as the embodiment of the Chinese nation’s spirit of independence and liberal thinking. My interest in Liu was immediately piqued, and a vague idea of blending Chen’s story with Liu’s was formed then. Between 2015 and 2018, on and off, I plowed through the 800,000-word, 3-volume, biographical tome.

In 2016, I also chanced to read Kong Shangren’s famous classic historical play The Peach Blossom Fan, and Li Xiangjun’s story left a deep impression. It then struck me that these women were among the Eight Great Beauties of Qinhuai and their lives were the most dramatic. I felt strongly that they had far more moral courage and integrity than people are willing to give them credit for.

By early 2018, the idea of writing a novel featuring them took concrete shape.

How long did it take you to make this volume? How did you go about finding information?

The research started in 2014 and continued in fits and starts until early 2018. In mid-2018 I started to work on the first draft. The full manuscript was completed in mid-2019.

The main source of information for Liu Rushi was her epic biography by Chen Yinke. For Li Xiangjun, I relied on The Peach Blossom Fan and Hou Fangyu’s short biography of her. As for Chen Yuanyuan, Wu Weiye’s narrative poem Song of Yuanyuan and Mao Xiang’s memoir Reminiscences of the Plum Shaded Cloister were the key source.

Other information about the period and cultural details mainly came from Yu Huai’s Banqiao Zaji (Diverse Records of the Wooden Bridge), Jonathan Spence’s Return to Dragon Mountain: Memories of a Late Ming Man and Zhang Dai’s The Dream Recollections of Taoan, plus various English-language reference books related to women, culture and the literary world in Ming China.

Why did you choose this particular historical period? What did the invasion of the Qing mean for Chinese society and culture?

The period in question is one that straddles two ruling regimes: the Ming and the Qing dynasties. I have a particular interest in this turbulent period because growing up I had come across intriguing and poignant human stories of love, sacrifice, divided loyalties and patriarchal cruelty from the period through books, operas, movies and TV dramas. As a grown-up, I’ve found these stories highly relatable, as they seem to reflect in some way our present-day human condition. Also, this period in Ming history saw the culmination of literary (in particular poetry) and music development. It witnessed a dynamic interaction between cultured courtesans and the literati, both in the romantic and literary sense. In short, in my new novel I wanted to highlight three courtesans’ love stories and their gritty struggle against a misogynistic society, as well as the era’s unique and vibrant artistic tapestry.

The Qing’s invasion into Han China certainly stirred up violent resentment in Chinese society, especially during Regent Dorgon’s oppressive reign as he tried to use brutal force to subdue the Han Chinese by foisting Manchu customs on them despite their repulsion (a notorious example was the shave-head mandate on pain of death). Luckily his violent rule didn’t last long, and thanks to the benevolent rule under Empress Dowager Xiaozhuang/the Shunzhu Emperor and later the Kangxi Emperor, there came a chance for war-torn China to heal and prosper as the Manchu rulers realized that only civilized ways could win hearts and minds.

The Han culture and civilization had very deep roots and had always been the Han Chinese’s pride, so the initial violent clash with the Manchu couldn’t but leave gaping wounds on society, both physical and emotional. As a matter of interest, this part of Chinese history is fleshed out in my 2017 novel The Green Phoenix.

How does the fate of these three women intertwine with the fate of China?

While alive, all three women struggle for survival, dignity and hope for a better life, but that struggle is in vain, much like the Ming Dynasty’s futile fight to avert its fate of humiliation and defeat.

But in the story, the women refuse to give up hope.

How were courtesans socially considered in China at the time?

Courtesans, like actresses, entertainers and prostitutes of the time, were socially classed as “jianmin” (worthless people).

They were considered below the commoner class, which effectively meant they were social outcasts.

Alice Poon

What was the fate of the protagonists?

Liu Rushi, upon her husband’s death, was bullied by her husband’s relatives into taking her own life. Li Xiangjun passed in her sickbed with a broken heart, having been abandoned by her lover.

Chen Yuanyuan lived into old age, but her fading years were said to be spent in quiet solitude in a nunnery.

What were the episodes that most touched you?

To tell you the truth, I teared up in several places of the story while writing the first draft.

One episode that touched me most was where the child Liu Rushi faces the death of her mother. I still choke up whenever my mind goes over that scene, because it always brings back the sad memory of my own mother’s death from lung disease.

There was a scene where Liu Rushi and Chen Yuanyuan have a heart-to-heart talk on the night before Liu’s wedding. They have been estranged from each other for a while due to an earlier row based on some misunderstanding. The way they are able to bare their souls to each other that night moved me deeply.

Are there traces in contemporary Chinese culture of the influence of these female figures?

Many Chinese people are familiar with the folklore about Chen Yuanyuan. One of Jin Yong’s famous novels – The Deer and the Cauldron – recreates Chen’s story and features her daughter as one of the wives of the protagonist. There are numerous movies and TV historical drama series that feature Chen.

Iconic historian and intellectual luminary Chen Yinke (1890 – 1969) spent ten years of the latter part of his life to write the 800,000-word An Ulterior Biography of Liu Rushi. He reconstructed Liu’s life story from her impressive collection of poetry and letters as well as her peers’ literary works (poetry, epistolary writings and memoirs). Some of Liu’s paintings are in the custody of The Freer Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. There is a 2012 China-produced film that features Liu Rushi as the protagonist.

Both Chen Yuanyuan and Li Xiangjun were both renowned kunqu opera singers. This operatic art reached its peak of development in the late-Ming era. Kunqu opera was named one of the masterpieces of Intangible Heritage by UNESCO in 2001.

Related articles: The Story of Princess Shanyin’s Harem

#ChineseWomen, #Concubines, #Courtesans, #MingDynasty, #QingDynasty

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

– Lisa See, Lady Tan's Circle of Women

#book quote of the day#lisa see#lady tan's circle of women#historical fiction#Yunxian Tan#inspired by a true story#Ming dynasty#Chinese medicine#book quotes#book recs

1 note

·

View note

Text

Making a mamianqun (馬面裙; lit. horse face skirt). Mamianqun can be traced back to the Song Dynasty and was in vogue from the Ming and Qing Dynasties until the Republican era. The skirt consists of two overlapping sections of fabric sewn together, each with a pleated section and skirt panels on either side. The skirt panels are overlapped to create the front and back of the skirt. This design allowed greater freedom of movement.

A note: Mamianqun are women's wear, but with the hanfu revival movement, men nowadays wear it too.

[eng by me]

#douyin#arts#hanfu#clothing#imparting culture#traditional craft methods#creator: 鲁磊#see the thing op blows on to make a fire?#i think i might post his video of making that at some point

3K notes

·

View notes

Note

do you have any idea when people in china stopped bowing to each other as a greeting? it seems like the most common forms of greeting now is to shake hands or wave both which were introduced from the west. it's the same in taiwan too.

Tldr: It never stopped because Chinese people never had the practice of bowing in greeting the way that Japanese people did/do.

-

(Note: there are types of greetings that involve a sort of bowing (ketou), but this is reserved for special occasions)

Back in the day, the greetings were made by clasping one's hands in front of them in the direction of the person being greeted. There might be some head lowering/slight bowing involved but it's done in conjunction with the hand greeting. You can see various forms of this in historical dramas and even hanfu shows and shortform videos. The exact way one held their hands changed in some years but the general idea is the same.

Women's and men's hand greetings differed back in the day. A women's greeting was called 万福礼 wànfùlǐ and consisted of holding the hands in front of oneself and bending the legs, or holding hands at the hip, etc. The exact way to hold the hands also changes through the years. Women also do what is called 肃拜 sù bài, which is an earlier form of a women's greeting and includes getting on one's knees (thus the 拜).

Some examples of greetings:

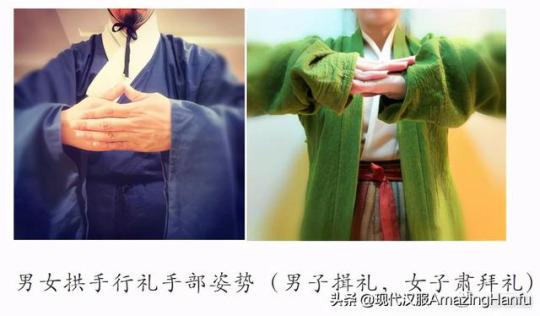

Men's vs women's hand positions

拱手礼 gōngshǒu lǐ ("cupped hands greeting"). The most common greeting. Top photo shows the gendered difference for proper etiquette for nowadays if you ware going to do it, for example, as a new year's greeting.

Bottom photos: I think if you look carefully in modern society, you can still see examples of this greeting in China. It is a gesture that can also be used to expresses one's gratitude. It is still there, it's just fell out of vogue in favor for waving and hand shaking.

This can also be seen in The video above shows Ming era 万福礼 as well as men's 揖礼. 作揖礼 zuòyī lǐ ("bow with clasped hand greeting") is kind of the same thing as 拱手礼, but 作揖 specifically includes a slight bow whereas 拱手礼 is merely the raising of the hands.

叉手礼 chāshǒu lǐ ("crossed hands greeting") popularised during the Western Jin - Song dynasties, seen in the drama "The Longest Day in Chang'an", which takes place in the Tang Dynasty. This particular greeting started out as one used by Buddhists in the Eastern Han dynasty.

https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/489897518

抱拳礼 bàoquán lǐ ("cupped fist greeting"). This one is something done more so by martial artists. For men, you use your left hand to cover your right hand. For women, the opposite is true. It is also called 吉拜 jíbài when showing respect. If you flip your hand (keep in mind men/women do this the opposite way), it is called 凶拜 xiōngbài and it used to show respect to the dead. So one has to pay attention to this.

There's kind of a lot more etiquette rules you could get into but this answer has already sort of gone beyond the scope of your question lol. Chinese people wrote rites books over the many dynasties so actually there are descriptions of how these greetings were done and over time and that's how they are replicated in dramas and movies.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Ma Xiuying from the Radiant Emperor duology!

Design/research notes under the cut

The characters read 馬秀英 (Pinyin: mǎ xiù yīng), her personal name, and 孝慈高皇后 (xiào cí gāo huáng hòu), her name as Empress.

There's certainly no dearth of material on Chinese clothing history out there. That is, if you can read Chinese, which I can't, so everything I have is from secondary and tertiary sources and/or relies on translation software. Fortunately, we're dealing with historical fantasy here, so some anachronisms are not only allowed but encouraged.

While Shelley Parker-Chan takes many liberties, the books are still set in a very specific time period, which is both a blessing and a curse. Most readily accessible resources will tell you about dynasties, which can span hundreds of years, and the duology takes place in a transitional period. So how to dress a Semu girl from the Yuan dynasty who lives with Nanren rebels wanting to revive the Song dynasty and who later becomes the first Ming empress?

Let's go through them one by one. The best resource was this book which is on the Internet Archive. I disregarded Mongol and Semu influences for the design since clothing is very much political and a way to either stand out or fit in with the surrounding society, see for example Wang Baoxiang wearing a topknot in Khanbaliq. Ma, I imagine, would want to fit in with the Nanren around her, so she's pretty much wearing the attire of Han women under Yuan rule. For the hair I went for something that looks youthful while being plausible, though I found very little on hair in this period, so who's to say.

The next one is from a specific scene in the book, so there is some description to go on: red, long sleeves with gold embroidery, high hair, red and gold ribbons. Since this is the scene where Ma declares herself queen and future empress in front of the Red Turban, it has to be a very deliberate dress. It therefore takes inspiration from Song aristocrats' broad-sleeved gowns as well as from 翟衣 (dí yī), the highest ceremonial gown of both Song and Ming empresses. (Some examples for 翟衣 are in this post, which also features the bird shaped crown I just had to include, and this post.) Her hair still has the loops, but it's much more sculpted.

Finally, Empress Ma! This is mainly based on the two actual portraits I could find of the historical figure that Ma is based on, with elements taken from other portraits and paintings. It includes 凤冠 (fèng guān), the phoenix crown, 霞帔 (xiá pèi), the sash, and 禁步 (jīn bù), the jade belt. This video shows how Ming dynasty layers are worn, but it refers to a much later period so it's not quite the same as Ma's.

(Some additional, historically irrelevant notes: I realized too late that a right-to-left timeline might be more appropriate. Oh well! Also, how the colours photograph frustrates me, I swear I did not make her this deathly pale. And finally, some of the characters look a bit smudged because my cat spilled water on them. I did what I could to save them.)

252 notes

·

View notes

Text

Amazing fanart by Joanacchi! Posted here on tumblr with their blessing. Each one is based on a style that reflects a particular ancient culture's art history. (See below for descriptions provided by the artist!)

Store (buy these prints!) Twitter Instagram

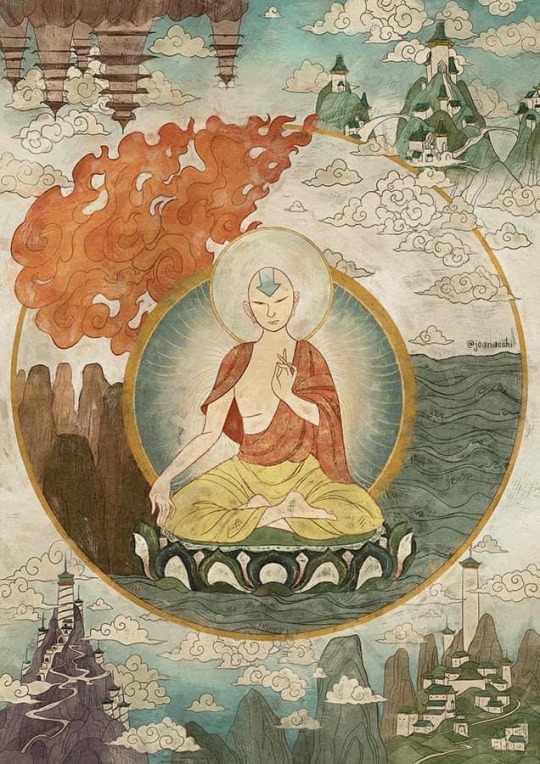

Aang: Tibetan Thangka

"Thangkas are traditional Tibetan tapestries that have been used for religious and educational purposes since ancient times! The techniques applied can vary greatly, but they usually use silk or cotton fabrics to paint or embroider on. What you can depict in a Thangka is really versatile, and I wanted to represent things that make up Aang as a character."

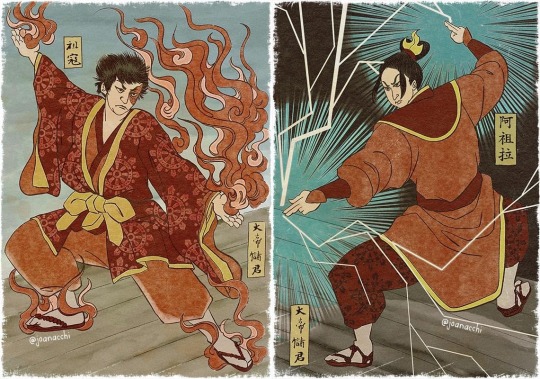

Zuko and Azula: Japanese Ukiyo-e

"Ukiyo-e is a style that has been around Japan between the 17th and 19th century, and focused mainly in representing daily life, theater(kabuki), natural landscapes, and sometimes historical characters or legends!

Ukiyo-e was developed to be more of a fast and commercial type of art, so many drawings we see are actually woodblock prints, so the artist could do many copies of the same art!

I based my Zuko and Azula pieces on the work of Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798-1861) one of the last ukiyo-e masters in Japan! He has a specific piece which featured a fire demon fighting a lord that fought back with lighting, and that really matched Zuko and Azula's main techniques!”

Toph: Chinese Portraiture from Ming and Qing Dynasties

"Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) was one of the longest in China! It was also a period where lots of artistic evolutions were happening, especially when it comes to use of colour! There was not a predilection for portraits during this time, but there are a lot of pieces depicting idealized women and goddesses from the standards of the time. For this portrait of Toph, I imagined something that maybe their parents commissioned, depicting a soft and delicate Toph which we know is not what she is about ♥️

Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) was the last Chinese Dynasty to reign before the Revolution. One of the most famous emperors of this period was Qianlong, and he really liked Western art! He commissioned a lot of portraits of his subordinates, and I chose a portrait of one of his bodyguards as a reference for the second Toph portrait, which I believe is much more like how she would want to be represented! The poem on top talks about the bodyguards' achievements during a specific war. I had no time to come up with a poem for Toph, so I just used the same one for the composition!”

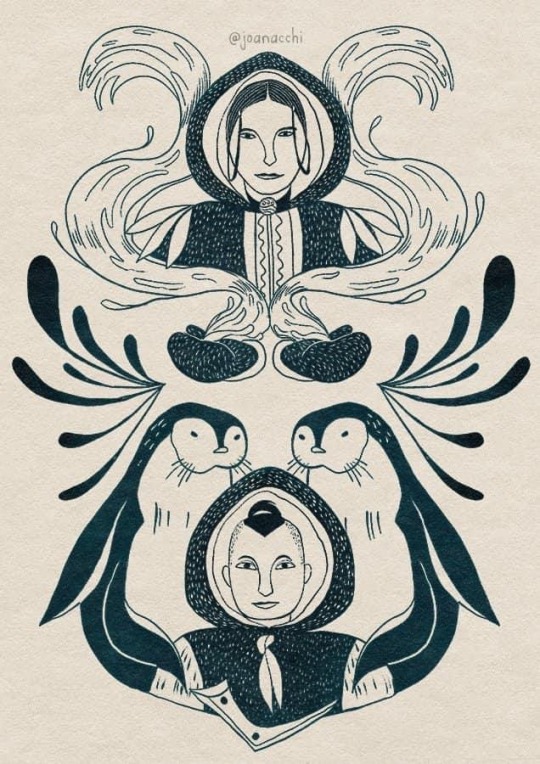

Sokka and Katara: Inuit Lithograph

"For a long time, Inuit art expressed itself in utilitarian ways. The Nomadic lifestyle of early Inuit tribes played a huge part in that: most art pieces are carved in useful tools, clothing, or children's toys, small and easy to be transported, and depicted scenes and patterns representing their daily lives!

That changed a lot during the colonization. Since the settling of the Inuit tribes, many art pieces began to be created in order to be exported to foreigns, so they started to sculpt bigger and more decorative pieces.

Lithography, which is a type of printmaking, was introduced to Inuit people by James Houston, that learned the technique from the japanese. The art form was quickly embraced by the inuit, as part of the process is very similar to carving. Prints that are produced by inuit artists are still being sold today!

As lithography is not an old art style and it's still commercially relevant to the Inuit communities, since creating these in 2021 I have been donating regularly to the Inuit Art Foundation, not only all the money I get from selling some prints of these but a bit more, at least once a year. Hopefully, I can increase donations this year!”

663 notes

·

View notes

Text

Love wins

Based nine coloured deers design off the Ming Dynasty, apologies if there’s some inaccuracies it was hard to find anything officially concrete for how women dressed back then ^^;

#sky cotl#sky: cotl#sky children of the light#skyblr#tac art#sky: children of the light#sky cotl fanart#megabird#season of the nine-colored deer

343 notes

·

View notes

Text

while staring at noob saibot i realised he had these cool nail coverings/nail guards! I'm not sure if they are the same thing but they remind me of zhijiatao (指甲套) or huzhi (護指), which were used since the ming dynasty by aristocrats and people of power

they're usually worn by women to protect their nails or as an accessory as long nails were seen as a symbol of power (it shows that you don't have to work) but men wore them as well. they're usually made out of metal like silver or gold and worn in pairs. it's kinda cool that a warrior like noobie wears these, he wears glove so what's even the purpose??

146 notes

·

View notes