#literary metaphors have lasted centuries for a reason.

Text

One of "Well, Actually"'s that I find most annoying:

We shouldn't use the Heart as the icon of emotions, because all those lovey-dovey Feelings come from the Brain (I'm very smart and got an 'A' in high school biology)

Look: The Brain is like a super reclusive genius, whose job it is to make sure The Household remains safe, and functioning. They are locked away in a garret, somewhere at the top of labyrinthine stairs. No one has ever heard their voice, and no one's even allowed to knock on their chamber door.

But three floors down, in a corridor around the corner to the left, there's a whopping, great, glowing monitor. And if the genius at the top of the stairs wants to send a Very Important Message to the inhabitants of the House, that message will appear on that screen.

Which part of the house do you think the Inhabitants come to associate with Important Truths, that must not be ignored -- the locked door at the top of the stairs (that most have never seen), or the glowing monitor with flashing lights that sometimes wakes them up in the middle of the night?

That glowing monitor is The Heart.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

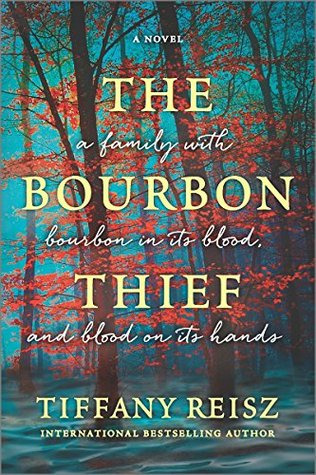

My aim for this year was to read more books. I read twenty nine, which was a vast improvement on last year (I read nine). There’s only twenty eight listed because I forgot about Kurt Vonnegut and Suzanne Mcconnell’s Pity The Reader. Sorry about that.

I tried to expand beyond my preferred genres, and made a concerted effort to read the recommendations given to me by friends and work colleagues. Nevertheless, a few of my own comfort reads made it on to the list.

Here they are! (There’s also a Q&A with myself under the cut)

The Best One

Metaphors We Live By - George Lakoff and Mark Johnson

I came to this book via two others. Philip Pullman in his nonfiction book Daemon Voices: Essays on Storytelling, referenced Mark Turner’s The Literary Mind, which in turn referred to Metaphors We Live By. It was an exercise in reverse-engineering, starting with Pullman’s perspective (whose style I greatly admire), and then working backwards to see what has informed his writing.

Metaphors We Live By helped me understand the importance of word choice, the messages we send through them, but also, how very wired our brains are for story-telling. It spoke of metaphor being fundamental to our conceptual system, not just as a poetic literary device. Whether the science is settled on this is irrelevant for me; it’s helped my writing immensely, and also been very useful in my day job. I just came away from it being so excited about language, life and brains.

The Surprising One

This Is How You Lose The Time War - Amal El-Mohtar and Max Gladstone

Firstly, I would never have picked this for myself. I don’t really read typical romance, and the idea of having to read love letters… ugh. I was so glad to find out from my book club it was less than 200 pages—I wouldn’t be wasting too much of my time.

But I think around page 30-40, something clicked and I was hooked on the intensity and—I don’t know—violence of the love between the two characters. The prose was quite abstract and there were a few new words I learnt, which is always exciting (‘apophenic as a haruspex’ comes to mind). And after, at book club, when I discovered the unusual way it was co-authored, the inventiveness of it left me feeling even more impressed.

The Not So Great One

Lucy By The Sea - Elizabeth Strout

I just did not connect with the main character at all, and there were a few sentences that irked me by the end of the book. If I recall, it was something like ‘What I remember about it was this:’

It was also the second book I’d read that touched on the subject of the pandemic, and my own experience of the pandemic coloured my response to the main character. I judged the hell out of her, in other words, and found her to be a bit of a rich, white idiot. I don’t have time for that.

The Best One About Writing

Steering The Craft: A 21st Century Guide to Sailing the Sea of Story - Ursula K. Le Guin

I honestly hadn’t heard of Le Guin until this year, so I read Wizard of Earthsea. And then my writing club set this as reading, and I just loved it. It’s more workshop and pragmatic (not a writing memoir, like Stephen King’s On Writing, or Lamott’s Bird By Bird), but I liked how accessible it was, and the exercises set at the end of each chapter (which I did not do but would like to with other people). Oh, I also loved the excerpts from other authors she used as examples to press home her points. They were great for context.

The One I Couldn’t Finish

The Fourth Wing - Rebecca Yarros

I read to chapter 4 of The Fourth Wing and I had to stop, and it was for an incredibly petty reason. It’s not a spoiler because this character very quickly dies and serves no other purpose other than to demonstrate the danger the main character Violet faces in trying to become a Dragon Rider. BUT… we see this poor guy getting hugged by his family as he leaves to start training (oh look how loved he is), then he pulls out a ring from underneath his shirt while in a queue and says so innocently, so completely unaware that he is a foil, that he and his fiancée will get married once he’s a Dragon Rider; how confident he is, so tall, and so strong, he is already halfway there. But oh wouldn’t you know it, he slips on the stone bridge and plummets to his death.

I think I was meant to feel a little bit sorry for him, or that maybe he was going to become Violet’s friend (she definitely needed one). But this guy was meant to be twenty years old. TWENTY. And engaged?

I am too old to trust the judgment of anyone who thinks getting married at twenty is a good idea. And the fact that Violet wasn’t thinking that made me question her judgment too.

It reminded me of every action movie ever involving soldiers: as soon as a side character mentions they have someone waiting for them back home—especially a baby they’ve never met—you know they’re going to die.

But… does this mean I’ll never try and read it again? No. I’ll just choose a whole bunch of other books before I look at it again.

#2023 books#2023 book review#books and reading#readblr#booklr#literature#too many authors to tag separately

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Catharine MacKinnon speaks on the work of Andrea Dworkin

This speech was given by Catharine A. MacKinnon at the Andrea Dworkin Commemorative Conference, April 7, 2006. This original transcript was prepared by secondwaver (blog now defunct).

Andrea should have been here for this. She would have liked it, or most of it. [laughter in audience]

There’s something awful, in both senses, that is, terrible and awe-inspiring, both, about Andrea’s work having to be my topic, instead of my tool, speaking her words not only to further our work together as they were and we did, for over thirty years, but to speak about it, and about her, as a subject, and in the past tense.

Yet even at the same time, her clarity and her passion and her inspiration to all of us to go further, go deeper, flows through her words.

Her whole theory is amazingly present in each phrase that she used. As Blake saw a whole world in a grain of sand, in each of Andrea’s sentences you can see the whole world the way she saw it.

Andrea Dworkin was a theorist and a writer of genius, an unparalleled speaker and activist, a public intellectual of exceptional breadth and productivity. Her work embraced the last quarter of the twentieth century and spanned fiction, critical works of literature, political analysis in essays and speeches and books, and journalism. Her legacy includes a vivid example of the simultaneity of thinking and activism, and of art and politics. Formally, she was an Enlightenment philosopher, in that she believed in and used reason. She was interested in diginity and equality and morality, and, especially, in freedom. Her contribution as a complex humanist was to apply all of this to women, and that changed everything.

An original thinker and literary artist, Andrea saw society ordered by power and the status excrescences of its variations animated by the sexual. She pioneered understanding the social construction of sexuality, and the sexual construction of the social, long before academics dared touch this third rail of social life.

In talking about The Story of O, a book of S/M pornography, in her book, Woman Hating, she says, “The Story of O claims to define epistomologically what a woman is.” She saw O as “a book of astounding political significance.”

Largely overlooked as an intellectual in her own time, she mapped social life before the postmodernists did, finding fairy tales and pornography to be maps for women’s oppression. She wrote about humiliation and fear before study of the emotions was a big academic trend. She analyzed social meaning before hermeneutics really caught on in the scholarly world, asking what pornography means, as for example, in the preface to Pornography, “this is not a book about what should or should not be shown. It is a book about the meaning of what is being shown,” what intercourse means, to men and women, most of all, what freedom for women means.

Her first book, Woman Hating, she “wrote to find out why I am not free, and what I can do to become free.” In her later work, this emphasis on freedom was synthesized with a re-made equality, consistent with and necessary for that freedom.

Her cadences were rhythmic, her use of repetition gaining inevitability and momentum, her suddenly-shifting convergences and metaphors were telling, and often surprising, lyric and antic, fluid and explosive by turns.

Such was her skill as a writer that she gave us almost the experience of pornography without her writing–being–pornography. She could even make intercourse funny, writing of Norman O. Brown speaking of entering women “as if we were lobbies and elevators.” [laughter in audience]

And for undertaking a synchronic reading of her work as a whole and selecting some over-arching themes, I want to reflect for just a minute on what it means that we are here doing this.

The relation between the work and the life is not a new question. But the relation between who Andrea Dworkin was and how her work was socially received is. And it has, as some of us have noticed, shifted noticeably, even dramatically, since the death of her body.

Three months after she died, so unexpectedly, a prominent French political theorist in a Ph.D. exam that I was in, in Paris, referred to her, excoriating the poor student, for eliminating various notables from the bibliography, referred to her as “l’incomparable Andrea Dworkin”–this, in a country that has long refused even to translate her work!

How has the world related Andrea Dworkin’s body to her body of work? Why was it necessary to destroy her credibility and bury her work alive, only now to be resurrected, disinterred, as it were? Why can now she be taken seriously, respected, even read, now that her body is no longer here? Why this is the first conference ever to be held on her work is one side of the coin of the question of why there never was one when she was alive. Her work is as alive now as it ever was, as challenging, threatening, illuminating, inspiring. Maybe it is that she can no longer tell us that we’re wrong, but don’t bet on it. Or maybe if you engage her work while she’s alive you further her mission, and we can’t have that, now, can we?

But why was respecting her and taking her work seriously such a risk? Why were the people who did it considered brave? As the quintessential scholar of the hell of women’s embodiment in social space, Andrea’s relation to her work is posed by, as well as in, this conference. Her work guides us to pursue this question, I think, as one of stigma. Stigma is what has kept people from reading Andrea Dworkin’s work, especially in the academy, where, I must note, people are not noted for their courage. That stigma has been sexual, due to her public identification as a woman with women, including lesbian women, especially as a sexually abused woman publicly identified with sexually violated women–in particular, the raped and the prostituted among us.

Being marked by sexuality, is, in her analysis, the stigma of being female, analyzed by Andrea in greatest depth in Intercourse, a work of literary and political criticism, a work of how men imagine and construct sexual intercourse when they can have it any way they want it, as they can, in fiction. It is a work of criticism of literature, that is at the same time a trenchant and visionary work of social criticism, her most distorted, I would say, a signal honor in a crowded field, published in 1987, at, as John and I were saying, the height of her powers. Of Elma, in Tennessee Williams’ Summer and Smoke, she wrote: “This being marked by sexuality requires a cold capacity to use, and a pitiful vulnerability that comes from having been used, or a pitiful vulnerability that comes from something lost or unattainable, love, or innocence, or hope, or possibility. Being stigmatized by sex,” she wrote, “is being marked by its meaning, in a human life of loneliness and imperfection where some pain is indelible.”

If the stigma of being a woman is the stigma of the body sexually violated, it lessens some when you die. That, girls, is the good news! [laughter in audience] Before now, we have had to be kept from reading Andrea Dworkin’s work, and were, by the living, breathing existence of her sexualized body attached to it, thereby, that work was sexualized. We had to be kept from holding a violated woman’s body in our hands and having her speak to us what she knows. Especially, we had to be kept from knowing in-depth, up close, and personal, that for women, having a body means having a sexuality attributed to you, the sexuality, specifically, of being a sexual thing for use, and from knowing that the need to be fucked in order to see and value ourselves as female means living within a political system that is pervasive, cultural, organized, institutionalized, unnatural, and unnecessary. Cutting to the quick of all of this, with her customary conciseness, Andrea always said she would be rich and famous when she was dead.

Now, Andrea’s great subject is the status and treatment of women, as has been said, focusing on violence against women, as central to depriving women of freedom.

Andrea’s method was predicated on the lived, visceral body experience that women have of our social status. She mined her life, particularly, in her work, knowing what she wrote from experience. Her driving force was rage and outrage, unapologetic critique, unbridled, passionate, truth-telling. Her sensibility was tenderness, kindness, and love. Her aesthetic is political–political in method, that is, you know it’s true because it happened to you, political in voice–clear, direct, no writing for passive readers, as John noted, and no talking down to anyone.

In the rhythms you can feel her breathing. Here is a woman talking to a publisher who is trying to get her to have sex with him. Essentially, this is a woman being sexually harassed. It is from Ice and Fire.

“I want, I say, to be treated a certain way, I say, I want, I say, to be treated like a human being, I say, and he, weeping, calls my name and says, please, begging me in the silence, not to say another word, because his heart is tearing open, please, he says, calling my name. I want, I say, to be treated, I say, I want, I say, to be treated with respect, I say, as if, I say, I have, I say, a right, I say, to do what I want to do, I say, because, I say, I am smart, and I have written, and I am good, and I do good work, and I am a good writer, and I have published. And I want, I say, to be treated, I say, like someone, I say, like a human being, I say, who has done something. I say, like that, I say, not like a whore. Not like a whore, I say, not any more. And I say to him, seriously, some day I will die from this, just from this, just from being treated like a whore, nothing else. I will die from it and he says, dryly, with a certain self-evident truth on his side, you will probably die from pneumonia, actually.”

Her writing is new; this is a new voice in literature. It has new forms; it’s full of new ideas, in part because the reality she wrote, like her, was submerged and ignored. But she was interested in all the classical questions of western philosophy–method, reality, consciousness, meaning, freedom, equality, especially the relation of thought to world, and the connections between social order and human action.

She created new concepts: moral intelligence, scapegoat, woman hating, not quite the same as misogyny, gynocide, gave new meaning to the term possession. She was a profound moral philosopher, and she gave new juice to old concepts like dignity, honor, and cruelty.

But I’m going to do a reading now, today, of her as a political philosopher, a specifically intellectual reading of her work in terms of these questions. Which is not how she wrote it to be read, actually. But she certainly knew what she was doing in these terms. She did not use the word method, but she had one, and she knew it. She observed in her book Pornography: “Women have been taught, that, for us, the earth is flat, and that if we venture out we will fall off the edge. Some of us have ventured out, nevertheless, and so far, we have not fallen off.”

In the afterward of Woman Hating, she said this: “One can be excited about ideas, without changing at all. One can think about ideas, talk about ideas, without changing at all. People are willing to think about many things. What people refuse to do, or are not permitted to do, or resist doing, is to change the way they think.” She knew thinking had a way, and that she had a way of thinking, and she wrote to change the way people thought.

Central to all her work was a metaphysical distinction between what she once termed truth and reality. While the system of gender polarity is real, it is not true.” The polarity of the sexes is a reality because reality is social. Equality of the sexes is true, but social reality is not based on it, but instead on a model that is not true, that is, that the sexes are bipolar, discrete, and opposite–some of us with little, tiny feet. For example, “we are living imprisoned inside a pernicious delusion, a delusion on which all reality, as we know it, is predicated.”

And, then, similarly, on the relation actually between sex and gender–not called that–but check it out: “Foot binding did not emphasize the differences between men and women, it created them, and they were then perpetuated in the name of morality.”

She also said we “need to destroy the phallic identity in men, and masochistic non-identity in women.” Now, it is not that she thought all reality was only an idea, as in classical idealism or only a psychology or an identity in the internal sense. She analyzed material reality and ideas as equally, and reciprocally, even circularly determinative. Of reality, she wrote this: “Men have asked over the centuries a question, that, in their hands, ironically, becomes abstract: ‘What is reality?’ They have written complicated volumes on this question. The woman who was a battered wife and has escaped knows the answer.” Philosophers, take note (is my note here): “Reality is when something is happening to you, and you know it, and can say it, and when you say it, other people understand what you mean and believe you. That is reality, and the battered wife, imprisoned alone in a nightmare that is happening to her has lost it, and can not find it anywhere. A fist in your face is not just the idea of a fist in your face. Reality is relational, and that relation is unequal and social.”

She also wrote explicitly of the relation between the ideational and the material in women’s status, without using specifically those words. That is, both have to be there, and both are there. In Right Wing Women, her 1978 book, the most extended analysis of women’s status and of feminism together, the elements and preconditions of both, she said this: “It does not matter whether prostitution is perceived as the surface condition, with pornography hidden in the deepest recesses of the psyche, or whether pornography is perceived as the surface condition, with prostitution being its wider, more important, hidden base, the largely unacknowledged sexual economic necessity of women. Each has to be understood as intrinsically part of the condition of women, pornography being what women are, prostitution being what women do, and the circle of crimes–these are the crimes against women, rape, battering, incest, and so on, that she discussed–being what women are for.”

The resulting “female metaphysics” under male dominance means that rape, battery, economic and reproductive exploitation “define the condition of women correctly, in accordance with what women are, and what women do,” correctly meaning consistently and accurately, within the existing system. She also said you can’t be a feminist and support any element of this model, including “so-called feminists who indulge in using the label but evading the substance.”

Her identification with women made her especially brilliant at seeing how women’s views are reflected in their material circumstances, hence, were rational, in that sense, including in her devastating portrayal of the academic, not-Andrea, so-called feminist woman who begins and ends Mercy, one of her novels, having been sexually abused, actually, this not-Andrea woman with the arch voice, siding with abstraction, with power, and with distance.

Right wing women, she shows in her book of the same name, also side with male power, because it is powerful, and reject feminism because women are powerless, in the hope, and on the bet, that male protection is a better deal than feminists’ resistance and struggle for change. It is, in that sense, a rational choice, meaning a direct reflection of their circumstances, which isn’t to say that it’s in their long-term interest.

She saw, always, how what women think and do makes sense in light of the realities of male power. As she put about right wing women, “the tragedy is that women so committed to survival can not recognize that they are committing suicide.”

The right–this is part of her deep analysis of religious fundamentalism–gives women form, shelter, safety, rules, and love. This complex and respecting analysis completely outdistances any analysis of false consciousness.

Similarly, in Intercourse, which I am going to have to discuss, this part, she wrote complexly of what it meant that Joan of Arc was a virgin. Probably not literally, she said, but because she carried herself with the dignity of the nonpenetrated, i.e. as a man, and her dressing as a man meant noncompliance with her inferior/female status, for which the Inquisition killed her. Joan wore men’s clothes, not to flout convention, or to make a statement about women’s status, or to portray dignity (performists take note), but because she’d been raped in prison. All she had to do was say–this is Joan–that she would not wear men’s clothes, and they would let her go free. Andrea says, “she was a woman who was raped and beaten and did not care if she died. That indifference is a consequence of rape, not transvestism.”

A new concept of ideology as sexual was proposed by Andrea in the book, Pornography: Men Possessing Women. Pornography is analyzed as male ideology, for its meaning and its dynamics. The concrete harms of pornography weren’t, then, its central topic. All the evidence of that was to come. But Andrea notes that “with the technologically advanced methods of graphic depiction, real women are required for the depiction, as such, to exist.”

In asking what it means, she said this: “the fact that pornography is widely believed to be sexual representations or depictions of sex emphasizes only that the valuation of women as low whores is widespread, and that the sexuality of women is perceived as low and whorish in itself. She says, “The fact that pornography is widely believed to be depictions of the erotic means only that the debasing of women is held to be the real pleasure of sex, and it also embodies and exploits, sells and promotes the idea that ‘female sexuality is dirty.’

So how do you go from seeing to being pornography, from buying a woman in pornography to owning her, from owning pictures of her to owning her, you might be wondering. She says this: “Male sexual domination is a material system with an ideology and a metaphysics. The metaphysics of male sexual domination is that women are whores. The sexual colonization of women’s bodies is a material reality.” This ideology is effectuated sexually, a level of belief and experience never before analyzed as political and gendered in the way she did.

Now on the subject of freedom, her core concern. She notes in her piece, “Violence against Women: It Breaks the Heart, Also the Bones,” “Our abuse has become a standard of freedom, the meaning of freedom, the requisite for freedom throughout much of the western world.” She goes on to say, “as to pornography, the uses of women in pornography are considered liberating.”

The subject of Intercourse, specifically, is what freedom means for women, precisely, how it is denied by the inferiority imposed and the occupation effected thereby, “destroying in women the will to political freedom, destroying the love of freedom itself,” when it takes place under conditions of force, fear, and inequality.

She says, ” to want freedom is to want not only what men have but also what men are. This is male identification as militance, not feminine submission. It is deviant, complex.” This becomes something she terms “the new virginity,” or what might be called the new freedom. “Believing that sex is freedom,” she says, intercourse needs blood, “to count as a sex act in a world excited by sadomasochism, bored by the dull thud-thud of the literal fuck. Blood-letting of sex, a so-called freedom, exercised in alienation, cruelty and despair, trivial and decadent, proud, foolish, liars, we are free.”

This analysis converged her thinking on equality, which underwent a progression over her life. In Our Blood, the piece renouncing sexual equality, she rejected equality, which she understood there as “exchanging the male role for the female role.” There was no freedom or justice in it, an accurate understanding of the mainstream view of equality. Over time, she reclaimed and redefined equality. In “Against the Male Flood” she said, “equality is a practice; it is an action; it is a way of life. Equality is what we want, and we are going to get it.”

To clarify the relation between her freedom and the equality that she redefined, she said this (this is again in her piece for the Irish women, “Violence Against Women: It Breaks the Heart, Also the Bones”)–check this out–: “What we want to win is called freedom or justice when those being systematically hurt are not women. We call it equality because our enemies are family.”

Even with family, Andrea took no prisoners, a paradoxical result of her passionate humanism. She says this in “I Want a Twenty-Four Hour Truce During Which There Is No Rape,” a talk to five hundred men in 1983: “Have you ever wondered why we are not just in armed combat against you? It’s not because there’s a shortage of kitchen knives in this country. It’s because we believe in your humanity, against all the evidence.”

Now, her legacy leaves us a lot to do. We can learn from the richness of her thirteen volumes, we can read her work closely, figure out how her writing was so singularly effective, and we can effectuate it. We can respond to the challenges of her questions, and be changed by her interventions and fearless probing of the structures and forces and people that rule our lives, denied by most people, a denial she also analyzed.

But in the academy, you know, whole theses could be written exploring sentences chosen virtually at random, that are ripe with possibilities, such as this: “any violation of a woman’s body can become sex for men. This is the essential truth of pornography.”

Or this: “in pornography, everything means something,” overwhelmingly ignored by massive departments of Media Studies and Communications, except for a tiny branch of largely social psychologists. Or this one, an analysis of social life in gendered terms: “Money is one instrument of male force. Poverty is humiliating, and, therefore, a feminizing experience.” Now, envision an economics where the laws of motion of sexuality socially are as well understood as the laws of motion of money are understood today, and the relation between the two of them.

Or this. Racism has always been central to her analysis, as it was in Pornography: “the sexualization of race within a racist system is a prime purpose and consequence of pornography.” And she talked about depicting women by sexualizing their skin, thus sexualizing the abuse, sexually devaluing black skin in racist America by perceiving it as a sex organ.

In Scapegoat she took this entire analysis to a whole deeper and higher level simultaneously showing what a gendered analysis of racism would look like in application. Try this: “While Nazism was a male event, Auschwitz might be called a female event, built on a primal antagonism to the bodies of women, an antagonism that included sadistic medical experiments.” In Scapegoat she also said this: “Hitler tried to make Jews as foul and expendible as prostitutes already were, as inhuman as prostitutes were already taken to be.” All of this can be taken up, unpacked, deeply considered, extended, gone further with.

Andrea wanted a day without rape. She said, “I want to experience just one day of real freedom before I die.” And that was the day without rape. She didn’t get it. She told the story of her own life in many ways in her work, over and over again. In one meditation, in Ice and Fire, turning over and over Kafka’s referring to coitis as “punishment for the happiness of being together,”–that’s a quote from him–Andrea writes this: “Coitis is punishment. I write down everything I know, over some years. I publish. I have become a feminist, not the fun kind. Coitis is punishment, I say. It is hard to publish. I am a feminist, not the fun kind. Life gets hard. Coitis is not the only punishment. I write. I love solitude. Or, slowly, I would die. I do not die.”

She wrote in Intercourse of her vision of all of our sexual lives, never, as always, excluding herself. In writing of the sex reformer Ellen Key’s consistent vision of sexuality for women, in the words of Ellen Key: “based on a harmony that is both sensual and possible,” one not based, in Andrea’s words, “on fear of force and the reality of inequality as now.” “A stream, herself,” Andrea wrote, “she would move over the earth, sensual and equal; especially, she will go her own way.”

“A stream herself.” Well, maybe a raging river at flood tide, perhaps, Andrea went her own way. She even wrote what might be her own epitaph: “I am whole, and I am flames. I burn. I die. From this light, later you will see. Mama, I made some light.”

Living without Andrea is living without this special light, the one she burned her life to make. Her incandescent mind never to illuminate another dark chasm or hard alley or guard tower of male supremacy. We are going to need a lot of what she wrote about, so long ago, at the end of Lesbian Pride, in Our Blood, seeing us walking into a terrible dark storm in which she said, “Those who are raped will see the darkness as they look up into the face of the rapist” in hunger and despair.

Love for women was what we need to remember, she said, that light within us that shines, that burns, no matter the darkness without which there is no tomorrow and was no yesterday. Quoting her now, she said, “That light is within us–constant, warm and healing. Remember it, sisters, in the dark times to come.”

Question and Answer Session with Catharine MacKinnon

Clare Chambers: Thank you very much for a wonderful, wonderful address. Does anyone have any questions or comments they would like to make?

Male voice #1: You touched on, I think, race in her work, which is rarely commented on. Do you understand the, I mean, there’s an invisibilization around a lot that she did, but I’ve often wondered why that, in particular, kind of dropped off the radar screen, in people’s reading of her. Don’t you understand it?

Catharine MacKinnon: Well, a lot of women of color know it’s there, and haven’t missed it, at all. I think it’s because it would give her credibility, that pigeon-holing her as just the woman who talks about women, as if racism isn’t about women, that that pigeon-holing, you know, confines her. You know, people think that things about women are “that’s just that stuff about women. Now let’s talk about freedom, or equality, or dignity, but this about women’s just that stuff.” And it would break down that isolation to recognize the central place that it always had in her work and the indivisibility of the analysis of male dominance and white supremacy in her work.

Female voice #1: You know that there’s all kinds of lies out there about how feminists never considered issues of race, and the women’s movement was a white women’s movement, and so on,

Catharine MacKinnon: As if all these women of color weren’t there making the women’s movement before Day One!

Female voice #1: Absolutely! Absolutely! It’s the most common attack on feminism, really, and then you go back, and look at Woman Hating, which is from 1974, there’s a huge section in there on race, and how feminism came from the struggles against racism in the US. It’s an enormously powerful section, the book was 1974! So it was written in the two years previous to that, so it gives the complete lie to these very serious and ridiculous accusations against feminism, so I ..

Catharine MacKinnon: But also, also, those accusations, which, you know, in part, are valid, for pointing out that an analysis of racism in the women’s movement in general, needs to be better, needs to go further, and so on. It also makes invisible all the women of color who are the backbone of that movement. In other words, it has this double way of being racist in itself. It’s like they weren’t even there! Like they aren’t even there.

Female voice #2: One of the things you made in your talk, let me speak to something that, I’ve been thinking about how to … (untelligible) … pull up, that you said that many of her individual sentences could be Ph.D. theses in themselves…

Catharine MacKinnon: Right.

Female voice #2: … that you could take the sentences and unpack them and go… I’ve often felt that, you know, Andrea Dworkin’s work is complex, it’s very detailed, it’s very nuanced, it’s very kind of packed with meaning, and I think one of the reasons, perhaps, why her work has often been misrepresented is that people haven’t been willing to read it with that kind of complexity, haven’t been willing to read it with that kind of seriousness that often people are willing to read the work of, you know, “great male theorists,” and that they have kind of been willing to just read it of very quickly and to see sentences which are hard to understand in a nuanced way–would you share that idea?

Catharine MacKinnon: I do! You know, people were told how to read Andrea Dworkin’s work, and have remarkably, on the whole, it strikes me, accepted that. They were told, you know, simplistic lies, about what it’s about, and including what our work together was about, and so that’s then what they see, people who should know better. And especially people who make their living by reading and writing about what they read, really should read what they write about.

Female voice #3: I wondered if you could say anything helpful about the way forward … look at the situation through Andrea Dworkin’s vision of it … you’re living it, we’re all living it, in different ways … You’re an academic, you work in the law, I’m an academic, I work in … we’re all in these different situations where … we’re put in these situtations where we have to compromise, … I don’t know … we don’t have to compromise … people like Andrea …

Catharine MacKinnon: Do you have tenure?

Female voice #3: Yes, I do.

Catharine MacKinnon: Ok, well …

Female voice #3: But I’m under a gagging order by my university …

Catharine MacKinnon: Pardon me?

Female voice #4:

I’m under a gagging order by my university … I may not say why … I’m in a kind of complicated position … but, you know, I’m constantly interacting with people who make my blood boil, and I’m sure there’s lots of people here who are as well, … I don’t know … or else you don’t say anything and it makes you crazier …

Catharine MacKinnon:

Well, you know, this may sound odd, but I don’t identify as an academic. I do work in the world, which includes, when I can financially afford to do it, thinking and writing, which I, myself, I did for twelve years with no job at all, I mean no real job, just one hitch to another, to another, kind of thing. You know it’s called unemployment, in the academic world and you know if the academic world finds value in it, looking on, while I’m addressing the world as a whole, that’s up to them. So that’s what I have to say about that. I think, too, that the way academia works is that younger people think that they will sell out now just a little bit in order to get tenure so that then can say something, which is why they wanted to be in academia in the first place and what happens is, that process destroys in you the very possibility of becoming the person who will have anything to say by the time that time comes.

Female voice #4:

I didn’t mean academia is in any way special, I don’t think it is, I just think it’s one way …

Catharine MacKinnon:

Indeed.

Female voice #4:

I take your point … compromise … the very thing you’re compromising to attain … I just wondered what the hell you do … that vision of the world is so dark … atrocity … and the experience of it … is there some some maneuver that we can make that doesn’t include having to do battle with men …

Catharine MacKinnon:

Well, I actually think it’s kind of important to, and indeed to, how to say it, I think one gets a lot of self-respect out of having integrity and that that gives you a kind of energy, it isn’t called doing battle with people around you all the time, it’s called not letting every atrocity just go by you. I think a tremendous amount of women’s energy in particular goes into denying atrocities to women, and I deal with them very directly, absolutely all the time, and you know people are always asking me, you know, how can you, like, do this, and I’m like, how can you, like, not? And I don’t mean that as a moral stand, I mean that as a stand of how much of your energy is going into denying what’s going on around you, how much of it is going into holding down, holding in, shutting up, squishing, compressing, flattening yourself inside yourself? You know, you get a tremendous amount of energy out of actually letting it in and flowing back with it, letting it go through you, and feeling what it really feels like, and being changed by it, and knowing what you know and saying it and finding ways to say it and push back against it and work around it and you get a tremendous amount of energy from actually — you know, Andrea once said to me, and it like shocked me totally, to death, I think she published it, that she, how’d she say, that she had recently come to think, it’s something she learned largely from me, she said, that women have a right to be effective. Now, I had never thought of it that way, you know, but I think that we do. Like, we live here, too. And that understanding that we have a right to occupy space and, you know, to speak out and to say what we see, and that that isn’t the same thing as doing battle all the time as if you’re just, you know, smashing your head against a brick wall. It’s actually engaging with the life of your own time, as opposed to acting like you weren’t even there. [applause]

Male voice #2:

I learned one thing from Andrea, that I attribute to Andrea, and I probably mangled it a little bit, and it’s not repeated, and I wouldn’t even be able know where to find it, maybe you could help me with this, that she said that biological superiority is the world’s most dangerous idea

Catharine MacKinnon, in unison: is the world’s most dangerous idea

Male voice #2:

Where is it?

Catharine MacKinnon:

It’s in Our Blood somewhere, it’s somewhere in Our Blood, I’m certain it is.

Male voice #2:

Yeah.

Catharine MacKinnon:

John, do you know where it is?

John Stoltenberg:

I think it might be on line, actually, it might be on line.

Catharine MacKinnon:

Yeah, look in Nikki’s website. You know Nikki’s website?

Other voices in the room:

Nikki Craft’s website. The website is on the postcard. … ironically, … I was the one, we were asked, I think, for favorite quotes, and that was one that I …

Catharine MacKinnon:

About the delusion of sexual polarity and …oh, no right … about biological determinism being the world’s most dangerous idea, yeah, see now, sociobiologists …

John Stoltenberg:

I don’t want to put you on the spot, and this might be a topic for a conversation, rather than a Q & A session, but since there are a lot of teachers, or people who teach here, and the one time Andrea taught was at the University of Minnesota, she co-taught with you, and I don’t know a lot about that time, because she was in Minneapolis and I was in New York…

Catharine MacKinnon:

And she missed you very much.

John Stoltenberg:

Ah. [pause] The question was,

Catharine MacKinnon:

I remember that.

John Stoltenberg:

what you learned while teaching together, about teaching. [pause]

I think that’s my question. I think I just want to know what it was.

Catharine MacKinnon:

Yeah. Well, one really major thing we learned was that we thought that we could teach a course on pornography, and, of course, you can’t teach on a subject that isn’t there, you know. I mean, in other words, it would be like teaching about a novel and not reading the novelist. So, and, indeed, sometimes, … one’s novels … but in any case, the way we organized it was: if I’m the court, here’s the pornography, and here’s the law on this pornography, which is usually just so way wacked out, beside the point–the second, of the first, you know, it’s highly instructive, so here’s the pornography, here’s the law on the pornography, here’s the pornography, here’s the law on the pornography, and we went all the way through, Playboy to Snuff, you know, and everything in between. And what we learned is that to say pornography violates women was not excessive, and it was not a metaphor. That, what was happening was that our students were in traumatic stress, on week-by-week basis, and, indeed, a couple of them had psychotic breaks, one when she … we actually had child pornography, and that was assigned, as well, and she, just in the way one of the children in the child pornography looked, or turned, or something, suddenly, she remembered having been sexually abused on a stage when she was a child, not too long before, and pornography had been made of her. Anyway, that was her … there were five or six people who had extremely serious psychological consequences from this, and the whole class was this cumulation of traumatic stress over the term and so we learned that we can’t, you can’t do what we thought you could do and we learned how much … that’s what we learned about teaching, was that you can’t do this, you know, unless you want to violate your students, and pornography violating women was not hyperbole. And it was not an approximation. And this was before there had been any real studies on the effects on women of consuming pornography, but the men were as messed up and harmed by it as the women. There were lots of men in that class, and that’s one thing we learned–that you can’t ever assume that you control the context more than the pornography does. That the pornography is its own context. That’s what we learned. You’re surrounded by critique! You’re surrounded by law! You’re surrounded by whatever, you know, but it is still going to do what it does. And it did it. We learned that. We also learned from the people who snuck in, who weren’t at the university, and just came in and sat in the back, and the people who were, that … first of all, that some of them, in particular, the .. I mean, Andrea had always known this, but we both learned it all over again, in a whole other way, that when people … first of all, that prostituted women know everything, and that if and when their visions can be brought out, and applied that whatever it is you need to know is something that they already know. And there were numbers of them, and that there’s something about the organizing potential of the issue of pornography in relation to prostitution that broke open in that class, and has gone forward, ever since. Now we learned that about teaching, as well, both in the university, and in a university within a city. And it also turned out, then, eventually to be a lot of the people who were our students who became the organizers for the ordinance that she and I ended up writing, out of the process of our teaching together. Just a couple things that occur to me.

Female voice #5:

… I’m a radical feminist .. (unintelligible). it is dark times, difficult times .. now … don’t by any means have the answer . (unintelligible) .. to go out to just talk to people we encounter . (unintelligible).. thank you so much …

Catharine MacKinnon:

Thank you. Andrea wanted respect for her work. And this conference has that. So thank you.

Clare Chambers:

If there aren’t any more questions at this point in the presentation, on which to end. We do have a drinks reception in the common room, to which you are all very, very welcome, and I hope you will. And let us end by thanking you all for coming, and thank you again, Catharine MacKinnon.

[applause]

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to Get Teenagers to Read Important Books? Ban Them.

When I was a young teenager near the middle of the last century, I asked the high school librarian if I could borrow J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye. Why did I want to read it? she asked. I lied and told her my parents told me it was excellent literature.

The real reason I wanted to read The Catcher in the Rye was it had been banned from the library. I knew the librarian kept one copy behind her desk, and I was determined to get it. She reluctantly handed it to me. I read it voraciously.

There’s no better way to get a teenager to read a book than to ban it.

Which is why it was so clever of the McMinn County, Tennessee, school board to vote to remove Maus from its eighth grade curriculum. Maus is a Pulitzer-winning graphic novel by Art Spiegelman that conveys the horrors of the Holocaust in cartoon form. The board cited “objectionable language” and nudity.

Before the board made its decision, teenagers in McMinn County probably weren’t particularly eager to read about the Holocaust, even in the form of a graphic novel. But now that Maus has been banned for objectionable language and nudity, I bet they’re wildly trading whatever threadbare copies they can get their hands on.

Since it was banned, half the teenagers in America seem to have bought Maus (or insisted their parents do). Two weeks ago, the book wasn’t even in the top 1,000 of Amazon’s bestseller list. Now it’s hovering around number 1.

Way to go, McMinn County school board! Get teenagers all over America excited to read about the Holocaust!

******

Btw, if you’d like my daily analyses, commentary, and drawings, please subscribe to my free newsletter: robertreich.substack.com

******

Even the McMinn County school board has been outdone by the Matanuska-Susitna school board in Palmer, Alaska, which presumably had a more serious problem on its hands than getting teenagers excited to read about the Holocaust. It couldn’t even get them to read the great novels of American literature.

So the Matanuska-Susitna school board voted 5 to 2 to ban Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison, Catch-22 by Joseph Heller, The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou, and The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Brilliant! I bet nearly every teenager in Palmer, Alaska is now deep into these books. They’re probably having intense discussions about them online late at night, away from their parents and other snooping adults. “Why do you think Ellison called himself ‘invisible?’” “How did Angelou come up with those amazing metaphors?” “Why did Daisy Buchanan reject Jay Gatsby?” “Wait! Gotta go! My parents are right outside my room! Call back in 20 minutes!”

The Great Gatsby was required reading when I went to high school. I admit I never read it. Had it been banned, I probably would have devoured it.

Beginning last fall, at least 16 school districts in a half-dozen states have demanded school libraries ban Out of Darkness. It’s a young adult novel about a love affair between two teenagers, a Mexican American girl and Black boy, set against the backdrop of the 1937 natural gas explosion at a New London, Texas plant that claimed nearly 300 lives. The book received lots of favorable reviews and literary rewards, but only a handful of teenagers read before it was banned. Now, it’s hot.

It’s the cleverest marketing strategy I’ve ever seen. Publishers must be clamoring to have school districts ban their books. (Why haven’t my books been banned, dammit?)

An influential group called “No Left Turn” is partly responsible. Just take a look at their website of books “used to spread radical and racist ideologies to students.” (Here's the link: https://www.noleftturn.us/exposing-books/) You can bet teenagers across America are now lining up to read them.

205 notes

·

View notes

Text

“...The letters, biographies, memoirs, and diaries that recorded Victorian women’s lives are essential sources for differentiating friendship, erotic obsession, and sexual partnership between women. The distinctions are subtle, for Victorians routinely used startlingly romantic language to describe how women felt about female friends and acquaintances. In her youth, Anne Thackeray (later Ritchie) recorded in an 1854 journal entry how she “fell in love with Miss Geraldine Mildmay” at one party and Lady Georgina Fullerton “won [her] heart” at another. In reminiscences written for her daughter in 1881, Augusta Becher (1830–1888) recalled a deep childhood love for a cousin a few years older than she was: “From my earliest recollections I adored her, following her and content to sit at her feet like a dog.”

At the other extreme of the life cycle, the seventy one-year-old Ann Gilbert (1782–1866), who cowrote the poem now known as “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star,” appreciatively described “the latter years of . . . friendship” with her friend Mrs. Mackintosh as “the gathering of the last ripe figs, here and there, one on the topmost bough!” Gilbert used similar imagery in an 1861 poem she sent to another woman celebrating the endurance of a friendship begun in childhood: “As rose leaves in a china Jar / Breathe still of blooming seasons past, / E’en so, old women as they are / Still doth the young affection last.” Gilbert’s metaphors, drawn from the language of flowers and the repertoire of romantic poetry, asserted that friendship between women was as vital and fertile as the biological reproduction and female sexuality to which figures of fruitfulness commonly alluded.

Friendship was so pervasive in Victorian women’s life writing because middle-class Victorians treated friendship and family life as complementary. Close relationships between women that began when both were single often survived marriage and maternity. In the Memoir of Mary Lundie Duncan (1842) that Duncan’s mother wrote two years after her daughter’s early death at age twenty-five, the maternal biographer included many letters Duncan (1814–1840) wrote to friends, including one penned six weeks after the birth of her first child: “My beloved friend, do not think that I have been so long silent because all my love is centered in my new and most interesting charge. It is not so. My heart turns to you as it was ever wont to do, with deep and fond affection, and my love for my sweet babe makes me feel even more the value of your friendship.”

Men respected women’s friendships as a component of family life for wives and mothers. Charlotte Hanbury’s 1905 Life of her missionary sister Caroline Head included a letter that the Reverend Charles Fox wrote to Head in 1877, soon after the birth of her first child: “I want desperately to see you and that prodigy of a boy, and that perfection of a husband, and that well-tried and well-beloved sister-friend of yours, Emma Waithman.” Although Head and Waithman never combined households, their regular correspondence, extended visits, and frequent travels were sufficient for Fox to assign Waithman a socially legible status as an informal family member, a “sister-friend” listed immediately after Head’s son and husband.

In A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf lamented that a woman born in the 1840s would not be able to report what she was “doing on the fifth of April 1868, or the second of November 1875,” for “[n]othing remains of it all. All has vanished. No biography or history has a word to say about it.” Yet as an avid reader of Victorian life writing, Woolf had every reason to be aware that in the very British Library where her speaker researches her lecture, hundreds of autobiographies, biographies, memoirs, diaries, and letters provided exhaustive records of what women did on almost every day of the nineteenth century.

One cannot fault Woolf excessively for having discounted Victorian women’s life writing, for even today few consult this corpus and no scholar of Victorian England has used it to explore the history of female friendship. Scholars of autobiography concentrate on a handful of works by exceptional women, and historians of gender and sexuality have drawn primarily on fiction, parliamentary reports, journalism, legal cases, and medical and scientific discourse, which emphasize disruption, disorder, scandal, infractions, and pathology. Life writing, by contrast, emphasized ordinariness and typicality, which is precisely what makes it a unique source for scholarship.

The term “life writing” refers to the heterogeneous array of published, privately printed, and unpublished diaries, correspondence, biographies, autobiographies, memoirs, reminiscences, and recollections that Victorians and their descendants had a prodigious appetite for reading and writing. Literary critics have noted the relative paucity of autobiographies by women that fulfill the aesthetic criteria of a coherent, self-conscious narrative focused on a strictly demarcated individual self. Women’s own words about their lives, however, are abundantly represented in the more capacious genre of life writing, defined as any text that narrates or documents a subject’s life.

The autobiographical requirement of a unified individual life story was irrelevant for Victorian life writing, a hybrid genre that freely combined multiple narrators and sources, and incorporated long extracts from a subject’s diaries, correspondence, and private papers alongside testimonials from friends and family members. A single text might blend the journal’s dailiness and immediacy and a letter’s short term retrospect with the long view of elderly writers reflecting on their lives, or the backward and forward glances of family members who had survived their subjects.

For example, Christabel Coleridge was the nominal author of Charlotte Mary Yonge: Her Life and Letters (1903), but the text begins by reproducing an unpublished autobiographical essay Yonge wrote in 1877, intercalated with remarks by Coleridge. The sections of the Life written by Coleridge, conversely, consist of long extracts from Yonge’s letters that take up almost as much space as Coleridge’s own words. Coleridge undertook the biography out of personal friendship for Yonge, and its dialogic form mimics the structure of a social relationship conducted through conversation and correspondence.

The biographer was less an author than an editor who gathered and commented on a subject’s writings without generating an autonomous narrative of her life. Reticence was paradoxically characteristic of Victorian life writing, which was as defined by the drive to conceal life stories as it was indicative of a compulsion to transmit them. This was true of life writing by and about men as well as by and about women. The authors of biographies often did not name themselves directly. Instead they subsumed their identities into those of their subjects. Authors who knew their subjects intimately as children, spouses, or parents usually adopted a deliberately impersonal tone, avoiding the first person whenever possible.

In her anonymous biography of her daughter Mary Duncan, for example, Mary Lundie completely avoided writing in the first person and was sparing even with third-person references to herself as Duncan’s “surviving parent” or “her mother” (243, 297). The materials used in biographies and autobiographies were similarly discreet, and the diaries that formed the basis of much life writing revealed little about their authors’ lives. Victorian life writers who published diary excerpts valued them for their very failure to unveil mysteries, often praising the diarist’s “reserve” and hastening to explain that the diaries cited did “not pretend to reveal personal secrets.”

Although we now expect diaries to be private outpourings of a self confronting forbidden desires and confiding scandalous secrets, only a handful of authenticated Victorian diaries recorded sexual lives in any detail, and none can be called typical. Unrevealing diaries, on the other hand, were plentiful in an era when keeping a journal was common enough for printers to sell preprinted and preformatted diaries and locked diaries were unusual. Preformatted diaries adopted features of almanacs and account books, and journals synchronized personal life with the external rhythms of the clock, the calendar, and the household, not the unpredictable pulses of the heart.

Diaries were rarely meant for the diarist’s eyes alone, which explains why biographers had no compunction about publishing large portions of their subjects’ journals with no prefatory justifications. Girls and women read their diaries aloud to sisters or friends, and locked diaries were so uncommon that Ethel Smyth, born in 1858, still remembered sixty years later how her elders had disapproved when she started keeping a secret diary as a child. Some diarists even explicitly wrote for others, sharing their journals with readers in the present and addressing them to private and public audiences in the future. By the 1840s, published diaries had created a popular consciousness, and self-consciousness, about the diary form.

In 1856, at age fourteen, Louisa Knightley (1842–1913), later a conservative feminist philanthropist, began to keep journals “written with a view to publication” and modeled on works such as Fanny Burney’s diaries, published in 1842. When the working-class Edwin Waugh began to keep a diary in 1847, his first step was to paste into it newspaper clippings about how to keep a journal. One young girl included diary extracts in letters to her cousin in the 1840s. Princess Victoria was instructed in how to keep a daily journal by her beloved governess, Lehzen, and until Victoria became Queen, her mother inspected her diaries daily.

Diarists often wrote for prospective readers and selves, addressing journal entries to their children, writing annual summaries that assessed the previous year’s entries, or rereading and annotating a life’s worth of diaries in old age. Journals were a tool for monitoring spiritual progress on a daily basis and over the course of a lifetime. Diarists periodically reread their journals so that by comparing past acts with present outcomes they could improve themselves in the future. A Beloved Mother: Life of Hannah S. Allen. By Her Daughter (1884) excerpted a journal Allen (1813–1880) started in 1836 and then reread in 1876, when she dedicated it to her daughters: “To my dear girls, that they may see the way in which the Lord has led me.”

Far from being a repository of the most secret self, the diary was seen as a didactic legacy, one of the links in a family history’s chain. Victorian women’s diaries combined impersonality with lack of incident. Although Marian Bradley (1831–1910) wrote, “My diary is entirely a record of my inner life—the outer life is not varied. Quiet and pleasant but nothing worth recording occurs,” she in fact devoted hundreds of pages to recording an outer life that she accurately characterized as regular and predictable. Indeed, the stability and relentless routine that diaries labored to convey goes far to explain why Victorians were so eager to read the poetry that lyrically expressed spontaneous emotion and the novels that injected eventfulness and suspense into everyday life.

Diaries and novels had common origins in spiritual autobiography, and diaries played a dramatic role in Victorian fiction, but although diaries shared quotidian subjects and diurnal rhythms with novels, they were rarely novelistic. Most diarists produced chronicles that testified to a woman’s success in developing the discipline necessary to ensure that each day was much like the rest, and even travel diaries were filled not with impressions but descriptions similar to those found in guidebooks. When something unusually tumultuous took place, it often interrupted a woman’s daily writing and went unrecorded.”

- Sharon Marcus, “Friendship and the Play of the System.” in Between Women: Friendship, Desire, and Marriage in Victorian England

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Weight of Other People’s Thoughts

Demoman/Soldier, 2k

Request for @lilythedragon05, Scotland

It was a bad idea to follow that tugging cord at the center of his being, the one that called him to Ullapool, and he never would have dared to entertain it if he knew it would have brought him here.

Jane sat by the ocean, stone’s throw from the town, but his distasteful frown kept his eyes locked firmly ahead instead of gazing dubiously at it. What had he been thinking? Coming to Ullapool had only make him feel worse, not better, a smirch against Tavish’s memory if there ever was one. Rubbing in Tavish’s face that he’d never go home again—and here Jane was, free to frolic across the whole damn planet, even if it took him to stupid countries ending in ‘land’.

He leaned further over his knees, barely feeling the sea breeze as he thought about his dead friend.

His murdered friend, he reminded himself. Murdered by someone who he thought he could trust, who now had to carry that guilt with him for the rest of his life.

Everywhere Jane looked it reminded him of Tavish. Maybe that’s why he’d come: self-flagellation. Appropriate punishment. Or maybe he was so desperate not to forget, he’d take the pain that came with remembering. Torturing himself truly, since he could look on the hills and surrounding coast that he had once only known through enthusiastic descriptions, see for himself the places where a young Tavish had played with dummy-grenades. He could imagine him talking to the local shopkeeps. He could practically see him walking up this very path, groceries in one hand, a newspaper filled with fried fish in the other as he took a large bite out of it-

Wait.

Tavish stopped dead, his face enveloped in utter shock. Still mid-chew, he said, “Jdra-ne?”

Jane leapt to his feet. “Apparition!” He pointed an accusing finger at the offending spirit. “Do not think for a second I will be cowed into repentance by the spectral manifestation of my guilt!”

Tavish nearly choked as he tried to swallow his bite of fish. “I…what?”

“Ghosts serve no purpose on my journey to recovery,” Jane continued. “Not even ones that look like my dead friend! Be gone creature of the other world!”

“What I- I’m not bloody dead.”

Jane squinted at him. He definitely didn’t look dead, totally opaque, no fettered chains representing his sins in life and his guilt over failing to help his fellow Man.

“…Are you sure?” Jane pressed.

“You’d think someone would know if they were dead,” Tavish grumbled poignantly, now glaring at Jane for some reason.

“I killed you though. It was-” -pickaxe right through the sternum, crushing, all the red bits coming out when they should have been in- “That was definitely fatal.”

“Aye, was, but I managed to limp my was back into Respawn range. Took a better part of an hour, but I made it.”

There was something odd to Tavish’s voice, something he wasn’t saying, but the realization that he might actually-seriously-really be alive was starting to set in and Jane was too afraid to believe it.

He took a step closer, past the bench he’d been enjoying his solitude at and completing a full circle around the Demoman. Tavish’s head followed him all the while, up until Jane came to a stop in front of him. “…Promise you are not a ghost?”

“I’m not a ghost,” Tavish said, as convincingly honest as he’d always been. Not that his acting skills hadn’t covered for his mendacity before-

-no, no that was a trick, it all turned out to be a lie a damn lie-

“Fine then. You’re not.” Though Jane would keep his eyes peeled for phantasmal anyway. “What the hell are you doing here then?”

“I live here,” Tavish huffed. “Gravel Wars are over, wasn’t going to spend the rest of my years in some blighted desert. Better question is what are you doing here, yank?”

Crap. Well, maybe a half-truth would suffice. “You always talked so much about Scotland I thought…” He rubbed the back of his neck. “I wanted to see what all the fuss was about.”

Tavish stood there, one hand still clasped around his groceries. The moment dragged on, vast seas of unsaid things between them, of regrets still festering, to which he ended with, “would you like me to show you around?”

Jane looked down, trying not to stare at his shoes but instead at the foreign soil around them. “…Sure. Why not.”

“Everything is incredibly vertical,” Jane complained as they climbed up yet another hill Tavish insisted was part of the journey.

“Aye, that’s why they call it the Highlands, BLU.”

Jane hated how fucking smug he sounded. Hated, and missed it all the same, missed how this bastard could set a fire in his gut just with one of his damn smiles.

“And there she is,” the Demoman said proudly as the crested the final ridge.

“Damn. Really went to crap in the last couple centuries.”

“Oi, don’t point fingers at me! I’ve only been around for forty of those.”

DeGroot Keep was shriveled and hunchbacked since Jane had last seen it, folding under its own legacy as ages had eaten the tallest spires first and chewed its way down to the cob. Still, he could just make out the choke points, the parapets, the places he used to go charging into with his mêlée weapon held high—all sanded down by the years, the vaguest memories of control points where a portal in time had briefly allowed Jane to witness their existence.

“So what,” he asked, following Tavish into the slight dip in the Highlands where the Keep nestled, “you live in here like some sort of anti-Italian?”

“An anti- what now?”

“Anti-Italians! Despises sun, allergic to garlic, doesn’t show up in mirrors, no sex life. Basic literary reference, RED.”

Tavish rolled his eye. “No, I’m not squatting in the dilapidated castle. Got a perfectly nice home down in the village, I just happen to have inherited this along with…all the other crap.” He waved his hand. “I’ve considered shelling out to having it restored but…dunno. Seeing it go from its heyday to this makes me think that in another couple hundred years it’ll just fall apart again.”

He sat on a piece of tumbled rock, one that used to hang over the Keep’s gate, a bright and shining keystone now used as a stool. Jane joined him.

“Don’t get much of this at home, do you? Old crap. Yer country’s still a wee babe you know, nothing’s even falling apart yet.”

“Incorrect!” Jane amended. “There are plenty of old things in America!”

“For last time lad, Thomas Edison wasn’t immortal, and he didn’t be build a second Shangri-La under Pennsylvania Avenue.”

“Your statements reveal both your ignorance and your compunction, but I was actually talking about mounds.”

“Mounds,” Tavish repeated dubiously.

“Yes! Mounds! Fourteen hundred years ago Americans were building ceremonial mounds in order to track celestial events! They look like animals from the top, lynx, bears, fish, all that crap. I used to walk next to this bird one every day on the way to school.”

Tavish blinked at him, tilting his head. “No offense Jane, but including Native people usually isn’t in your worldview. Where’d you even learn all ‘o that?”

“My mother taught me, so think insinuating more cyclops—lest you show disrespect against her memory and I am forced to take out your other socket!”

Tavish raised his hands defensively, but there was a smile creeping at the corner. “Alright, alright, I get ye. A Mum’s honor is a serious thing.”

“Hm. Good.” Jane glanced ahead, suddenly afraid of lapsing back into silence, as though Tavish would start to slip away from him if they did. “How is your mother?”

“Ah…she passed some years back.”

“…I’m sorry to hear that.”

“It’s alright.” Tavish paused. “I still see her sometimes.”

“Metaphorically or…?”

Tavish glanced at him, but then away just a quickly, as though frightened of what he might see. “I’d rather not talk about it, if that’s alright with you.” Instead, he stared ahead, the sun setting between its cradle within the mountains. “Heh. At least there’s something that’s the same no matter where you go. Always a sunset.”

“Guess so.”

Still, Jane found he liked this one better than the ones back home. At least, better than all the ones he’d seen before he’d met Tavish.

The next day was spent in the village, and Jane couldn’t help but yearn for more of Tavish’s time, more of his attention. His friend. His friend who was still alive. Tavish had a kind word for every person they passed, all of whom didn’t seem to notice Jane at all, simply starting up a conversation with their fellow local and submitting to the rhythm of the morning. Breakfast was some sort of potato scone, but Jane wasn’t hungry, so he just walked beside Tavish as the other man ate. They found themselves at the same bench where they’d first run into each other.

“So,” Tavish asked. “Ullapool everything you thought it would be?”

“Hm. It’s…nice. It is obviously not perfect for geographical reasons entirely outside of its control, but. I understand how it made you the man you are.”

“Me? Nah.” Tavish wiped off his mouth with his sleeve. “I made myself like this.”

Again, he wouldn’t look at Jane, wouldn’t say what they were both thinking. That things had gone wrong, that they had both fucked up. One of them more than the other, but Jane had found him again, and maybe they could still figure something out, still have time to unearth all that they had deemed too dangerous and buried in the sand.

Jane reached forward, and put his hand over where Tavish’s was resting on the bench.

And watched it pass straight through.

Jane sprang away. “I knew it! I knew you were a ghost!”

Likewise, Tavish stood up sharply. “I am not. I bloody told you I was’t.”

“Liar! I will not be swayed by any more perjury from your ethereal mouth!”

“I’m not lying!” Tavish snarled at him, his eye dark and narrowed, burning hotter than the words would imply. “I never lied. I never wanted any of-”

“Blasphemy!”

“Would you just listen for-!”

“You cannot guilt me apparition! For I know that-”

“Shut up! Just fucking shut up!” Tavish’s fist closed around the neck of his scrumpy bottle, half drained before noon, and threw it full force at Jane’s head.

Jane raised an arm to block the incoming blow, but the impact never arrived. A second ticked by, then two, then three, and slowly he lowered his forearm to reveal the panting Demoman behind it, shoulders heaving and an inscrutable expression tearing across his features.

“How’s that for the truth you bleeding idiot,” he said.

Jane looked to Tavish, then rotated his neck slowly, staring at the bottle that had landed in the grass behind him. He blinked, willing what he was looking at to make sense, to suddenly disappear and go back to where things were a second ago. To believe he hadn’t seen that bottle connected with his own nose.

There was something he didn’t want to do, but he did it anyway, turning his gaze forward inch by agonizing inch, staring down at his own hands. Fully taking how translucent they were.

The moment shattered, Tavish tore his eye away. “Fuck. Fuck I’m sorry. I shouldn’t’ve…”

Jane was still looking at his hands. There was panic, deep and overwhelming rising within him, but there was no raised pulse to accompany it, no sweat on the back of his neck.

He lifted his chin to Tavish. “What? I don’t…”

“I didn’t die,” Tavish said thickly. “You did. I killed you and I walked off and you just bled out for who knows how long and-”

-the pickaxe but also a sword, just as deadly buried two feet into his chest and the man above him trying to shove it in a few extra inches, strangled screaming as it pushed deeper-

Jane hadn’t been paying attention to the last half of Tavish’s muttered confession. The Demoman was crying now, pawing furiously at his one lone eye as stared out valley below them, looking anywhere but at Jane as his sclera turned red.

“I’m sorry,” he sputtered. “Christ Jane I’m so fucking sorry. If you came to haunt me or whatever I just- I just want you to know that you can’t hate me more than I hate myself. That it’s been killing me every day since.”

He collapsed on the bench, curling away from Jane as he buried his face in his hands.

It could have been some sort of trick. A ghost bottle or…no Jane wouldn’t even try. He attempted to remember what flight he had come in on but couldn’t. He grasped for how many years since the Gravel Wars had ended, and couldn’t find the answer.

Jane was a ghost, yet everything still hurt as much as it had when he had lived. Immaterial, and he still so badly wanted to touch Tavish’s hand.

He sat on the bench next to him. “I didn’t come to make you feel bad, Tavish.”

“Then why did you come?” It sounded like it was meant to be venomous, but instead it only sounded empty—empty and wet with tears, like a plastic bag trampled into a puddle.

Jane looked down at his hands. His useless, ghost hands that he could still knit together. “I…I wanted to see you,” he said truthfully. “I missed you.”

Tavish looked at him, bleary-eyed. He whispered, “I missed you too. So damn much.”

“Whatever I was doing before, I missed you enough to come here. To someplace I thought you would be.”

A panicked jolt crossed Tavish’s face. “You’re not leaving, are you?” The same man who a moment ago thought Jane had come to smother him with guilt was despondent at the idea that Jane might go after all, that he wouldn’t get a chance to hurt himself with his own regret anymore.

“No, no not yet,” Jane said. He tried his best to wrap and arm around Tavish’s shoulder. The mortal shivered where their skin met.

“Okay,” Tavish said quietly. “Okay. Good. Thank you. I don’t think I can…When I saw you sitting up here I couldn’t believe it could be fore something good. That the only reason you’d want to haunt me would be because you hated me.”

“I don’t hate you.”

It was true. Even though he remembered now, remember lying there, thinking how they’d killed each other, Jane had only ever hated the man who’d believed the TV’s lies.

“I really did come because I was thinking of you. Missing you.” Jane paused. “Today was fun. I’m sure you have a lot of other places to show me, right private?”

“…Sure. Sure whatever you want.” Tavish wiped at his nose. “I’m sorry Jane.”

“It’s alright Tavish.” He held his head in the crook of Tavish’s neck. “I’m sorry too.”

30 notes

·

View notes

Note

I want to hear about gay knights. Please.

Ahaha. So this is me finally getting, post-holiday, to the subject that was immediately clamoured for, when I volunteered to discuss the historical accuracy of gay knights if someone requested it. It reminds me somewhat of when my venerable colleague @oldshrewsburyian volunteered to discuss lesbian nuns, and was immediately deluged by requests to do just that. In my opinion, gay knights and lesbian nuns are the mlm/wlw solidarity of the Middle Ages, even if the tedious constructionists would like to remind us that we can’t exactly use those terms for them. It also forces us to consider the construction of modern heterosexuality, our erroneous notions of it as hegemonically transhistorical, and the fact that behaviour we would consider “queer” (and therefore implicitly outside mainstream society) was not just mainstream, but central, valorized, and crucial to constructions of medieval manhood, if not without existential anxieties of its own. Because medieval societies were often organized around the chivalric class, i.e. the king and his knights, his ability to make war, and the cultural prestige and homosocial bonds of his retinue, if you were a knight, you were (increasingly as the medieval era went on) probably a person of some status. You had a consequential role to play in this world, and your identity was the subject of legal, literary, cultural, social, religious, and other influences. And a lot of that was also, let’s face it, what the 21st century would consider Kinda Gay.