#king constantine ii of greece

Photo

King Constantine II and Queen Anne-Marie of Greece with their first child, Princess Alexia.

by Patrick Lichfield, 1965

57 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Μόχθων δ’ ουκ άλλος ύπερθεν ή γας πατρίας στέρεσθαι.

- Euripides

There is no greater grief that the loss of one’s fatherland.

RIP King Constantine II of Greece (1940-2023)

Constantine II, the last King of Greece, died aged 82 in Athens. A much-loved second cousin of King Charles III and godfather to Prince William, Constantine ascended to the Greek throne in 1964, but was forced to leave the country just three years later following a military coup. Constantine and his family then settled in the UK, where they lived for decades after the Greek monarchy was abolished in 1973.

In 2013, in the midst of the economic crisis, Constantine and Anne-Marie returned permanently to Greece after four decades of exile. "All Greeks who live in exile want to return. It's in their blood," he said at the time. His death closes a chapter on Greece’s history. It’s been decided that he would not be given a state funeral.

#euripides#greek#classical#quote#king constantine II#king constantine II of greece#greece#democracy#exile#monarchy#history#royalty#europe#icon

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

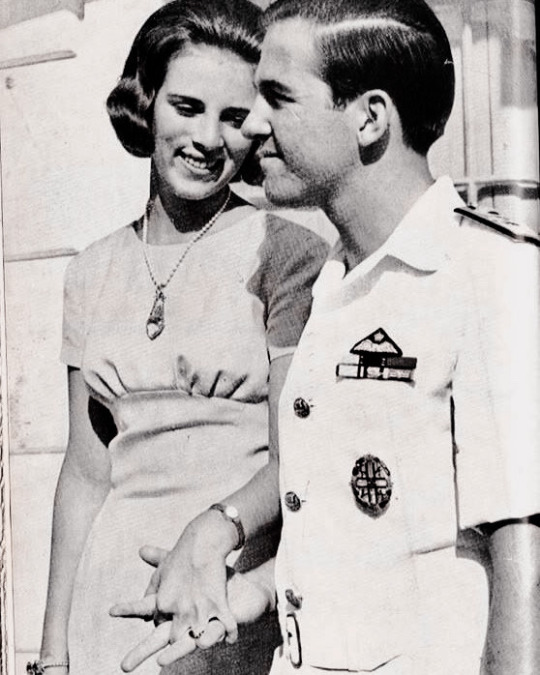

King Constantine II of Greece and his fiancée, Princess Anne-Marie of Denmark, in Corfu, July 1964.

#always hand in hand <3#king constantine ii of greece#queen anne marie of greece#princess anne marie of denmark#greek royal family

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Princess Sofia of Greece takes a snapshot during an excursion with her brother, Prince Constantine (right), and her cousin, the Prince of Hannover, in Athens in 1954.

#greek royal family#house of glücksburg#king constantine ii of greece#queen sofia of spain#princess Sophia of Greece#1954

1 note

·

View note

Photo

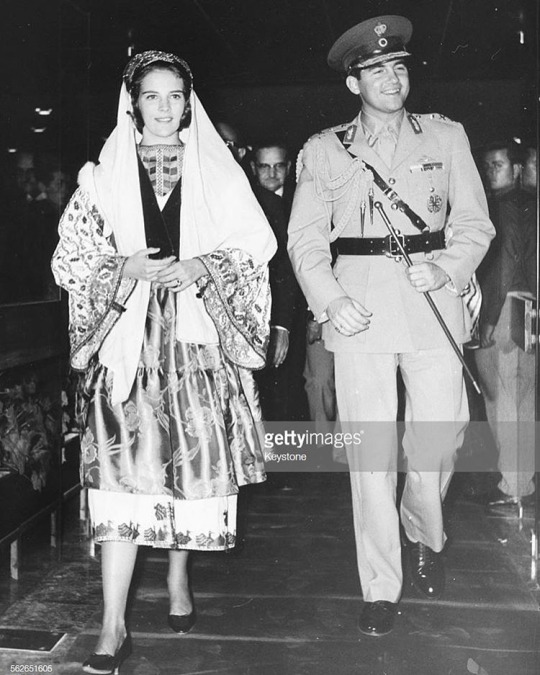

King Constantine of Greece and his wife Anne Marie, who is wearing a traditional local costume from Tilos island, Dodecanese, visiting the Dodecanese Islands, October 19th 1965. (Photo by Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

#greece#europe#greek royals#european royalty#traditional clothing#historical fashion#folk dress#traditional dress#folk clothing#greek people#greek royal family#anne-marie of the hellenes#ex king Constantine ii of Greece#tilos#dodecanese#greek islands

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Princess Anne embraces Queen Anne-Marie of Greece after attending the funeral of King Constantine II in Tatoi on 16 January 2023

#🥺#embracing everyone#bless#princess anne#princess royal#tim laurence#timothy laurence#queen anne marie#british royal family#brf#greek royal family#king constantine of greece#king constantine ii

185 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The former Greek King Constantine II recalling the moment he asked King Frederik IX of Denmark for permission to marry his then 16-year-old daughter Princess Anne-Marie in the documentary seres A Royal Family (2003). Constantine and Anne-Marie were married 1 and 1/2 year later on 18 September 1964.

REST IN PEACE CONSTANTINE II OF THE HELLENES (1940-2023)

#royaltyedit#historyedit#king constantine ii#king frederik ix#danish royal family#greek royal family#en kongelig familie#royal in laws#**#gif: greece#💔#death and funeral: constantine

156 notes

·

View notes

Text

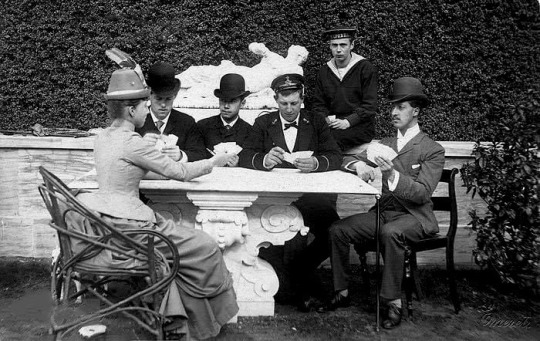

Cousins playing cards, late 1880's

Princess Alexandra of Greece and Denmark, Crown Prince Constantine of Greece and Denmark, Tsesarevich Nicholas, Prince George of Greece and Denmark, Grand Duke George Alexandrovich, Prince Albert Victor of Wales.

#alexandra georgievna#king constantine i#tsesarevich nicholas#George of Greece and Denmark#george alexandrovich#prince albert victor#1880s#danish royal family#nicholas ii#grand duke george#albert victor#alexandra of greece

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

King Constantine II and Anne-Marie of Denmark.

#royal couple#kingdom of greece#greece and denmark#king constantine ii#anne marie of denmark#Κωνσταντίνος Βʹ

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

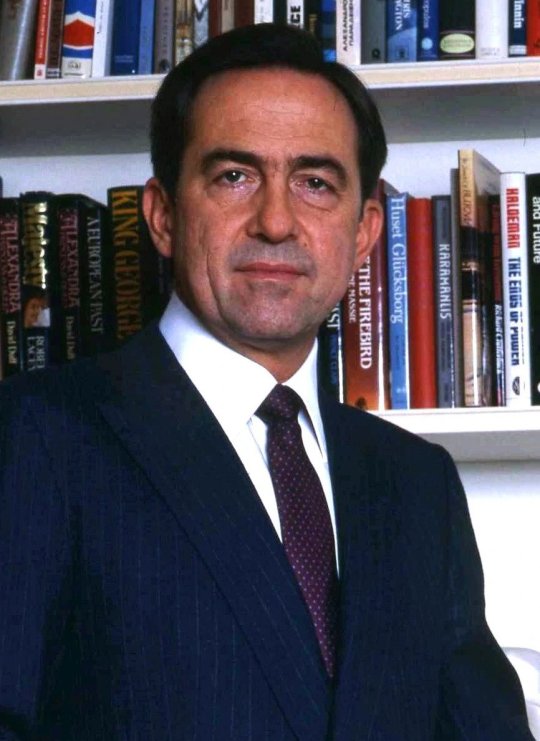

News : King Constantine II of Greece passed away on January 10th 2023, after suffering from a stroke.

He will be buried as a private citizen at the Metropolitan Cathedral of Athens on January 16th 2023 -January 12th 2023.

#king constantine#king constantine ii#greek royal family#greece#2023#king constantine ii's death#official portraits#royal children#my edit

61 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I consider myself King of the Hellenes and sole expression of legality in my country until the Greek people freely decide otherwise. I fully expected that the military regime would depose me eventually. They are frightened of the Crown because it is a unifying force among the people.

- King Constantine II of the Hellenes

An important chapter of Greek history ended on 11 January 2023, in Athens, with a deafening silence. The former king Constantine II died at the age of 82 in Athens. Some Greek media outlets referred to him as Constantine Glücksburg, not wishing to mention the royal title of the former monarch who was deposed in 1974.

The last member of the Danish dynasty to rule from 1863 until the return of the Parliamentary Republic was the cousin of the British monarch Charles III and one of the godparents of his son, Prince William, and the brother of Queen Sofia of Spain. But his death caused barely a rustle in Greece, a country that has been riven by divisions between royalists and democrats since its creation.

He was not given the state funeral he had so much desired. Neither the Greek Prime Minister, Kyriakos Mitsotakis, nor the President of the Republic, Katerina Sakellaropoulou, were present at his funeral on 16 January. His death "marks the formal epilogue (...) of a chapter that was definitively closed with the 1974 referendum," when Greeks voted by 70% to abolish the monarchy, said the prime minister in a terse message of condolence. The conservative leader also recalled "the eventful journey of former King Constantine, marked and punctuated by turbulent moments in the contemporary history of Greece." "History now has the floor. It will judge fairly and severely the Constantine of public life," he concluded.

The legacy of King Constantine II of the Hellenes remains a mixed one and mirrors the divided feelings of Greeks have to this day about their last king.

In many ways, Constantine was a victim of the vicious political infighting that had characterised Greek politics and its society for much of the period since the second world war. It perhaps needed a stronger, more experienced and more resolute approach to surmount the crises of his three-year reign than the young man in his early 20s could manage. In later life he said in an interview that he might have liked to be an actor or a journalist, but his fate was to spend his life as an ex-king, harried by Greek politicians and in turn harassing them in a prolonged legal fight for compensation for his family’s lost property, eventually through the European court of human rights.

Born in Athens, Constantine was the son of the Greek crown prince, Paul, the younger brother of King George II, and his German-born wife Princess Frederica, and was taken into exile as a baby following the Italian and then Nazi invasions of the country in 1940-41. His early years were spent first in Egypt and then in South Africa, before the family returned to Greece following the referendum that restored George to the throne in 1946. George died the following year, and Paul became king.

Constantine was educated at a private high school in Athens, modelled on the same lines as the German educationist Kurt Hahn’s principles at Gordonstoun, and afterwards attended Athens University to study law. A keen sailor, Constantine was a member of Greece’s winning sailing team at the 1960 Rome Olympics – the country’s first gold medal in nearly 50 years.

He succeeded to the throne aged 23 on his father’s death in March 1964, becoming head of state in a country that had not got over the civil war between communists and the Greek government of 1946-49, and where political tensions and divisions continued to run deep. The CIA, desperate to avoid Greece falling into communist hands, was also active in Athens. Greece was a strategic pawn between the US and the Soviet Union, each anxious to pull the country into its sphere of influence in the eastern Mediterranean. At the same time, it was attempting to modernise with social and economic reforms as an associate member and applicant to join the Common Market.

The month before Constantine came to the throne, a general election had produced a leftwing government under George Papandreou, following eleven years of rightwing government. Within a year, relations between the king and his prime minister were breaking down. Conservative army officers were alarmed by a perceived leftwards drift among the junior ranks, who were supported by Papandreou’s Harvard-educated son Andreas. When George Papandreou announced that he would take over the defence ministry himself, Constantine refused to allow him to do so, and the government resigned. In the hiatus that followed, the king attempted to appoint a government without holding an election and was accused of acting unconstitutionally.

When elections were finally called in April 1967, the likely re-election of Papandreou was forestalled by an army coup led by colonels. Constantine initially appeared to go along with the insurgents. He argued later that he had had no choice as the palace was surrounded by army tanks, but there were also persistent suggestions that he had been urged by the American embassy to do so in order to avoid another radical government. Many Greeks and civilian politicians never forgave the king for acceding to the coup, but within months he attempted a counter-coup of his own, fleeing to loyalist troops in the northern city of Kavala that December in an attempt to create a rival military support and force the junta to resign.

The operation was poorly organised and, although the air force and navy declared their support, the army and its officers rallied to the coup leaders. Support for the king melted away within 24 hours. Fearing bloodshed if it came to a military confrontation, Constantine and his family fled into exile, first in Rome and then a few years later in London.

There was no going back for the king. The junta, led by Colonel Georgios Papadopoulos, brutally consolidated their regime using censorship, mass arrests of opponents, torture and imprisonments, and were not going to reinstate Constantine after his attempted coup. When monarchist navy officers unsuccessfully attempted to overthrow the colonels in June 1973, Papadopoulos declared the country a republic, endorsed subsequently in a plebiscite widely assumed to have been rigged.

Nonetheless, when the regime fell following the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974, to be succeeded by a civilian government, a further referendum was held to determine whether the king should be restored. Constantine was not allowed to return in order to campaign on his own behalf, though he was allowed to broadcast an address from London in which he apologised for his previous errors. But his maladroit interference with the civilian governments before the coup was held against him and the outcome of the vote in December 1974 was heavily in favour of a republic: by 69% to 31%.

Thereafter, for decades, Constantine was prevented from visiting Greece except briefly and on rare occasions: for his mother’s funeral in 1981 and for an attempted holiday in 1993, when he found his yacht was constantly harried by torpedo boats and aeroplanes. The following year, the Greek government revoked his citizenship and passport and seized the royal family’s property. “The law basically said that I had to go out and acquire a name. The problem is that my family originates from Denmark and the Danish royal family haven’t got a surname,” he said, adding that Glücksburg was the name of a place not a family: “I might as well call myself Mr Kensington.”

In 2000, the court of human rights found for the king in relation to the property, though it could only order compensation, not the return of his extensive estates nor the royal palace at Tatoi and awarded him only 12m euros (around £10m), rather than the 500m he had asked for: a reduction that the Greek government counted as a triumphant vindication. It nevertheless took another two years to pay the money and, when it did so, the government took it from its extraordinary natural disasters fund rather than general reserves. In retaliation, Constantine used the money to set up a charitable foundation in the name of his wife to assist Greeks suffering from natural disasters. He said: “I feel the Greek government have acted unjustly and vindictively. They treat me sometimes as if I am their enemy – I am not the enemy. I consider it the greatest insult in the world for a Greek to be told he is not a Greek.”

Generally, while expressing a wish to be allowed to live in Greece, which was granted in 2013, Constantine seemed equable about his fate and did not attempt to regain the throne. “All I want is to have my home back and to be able to travel in and out of Greece like every other Greek. I don’t have to be in Greece as head of state. I am quite happy to be there as a private citizen,” he told the news media in 2000. “Forget the past, we are a republic now. Let’s get on with the future.”

By the standards of the hapless Greek monarchy, Constantine II, the last king of the Hellenes, who died aged 82 on 10 January 2023, led a comfortable life in exile after a brief and turbulent reign. Of the seven Greek monarchs of the 19th and 20th centuries, three were deposed, one assassinated, two abdicated and one died of septicaemia after being bitten by a barbary ape in the royal gardens.

The Glücksburg monarchy was German-Danish in origin, imposed on Greece in the 1830s. During prolonged wrangling after Constantine’s deposition, the Greek government refused to give him a passport until he acknowledged that he was Mr Glücksburg, whereas he insisted he was just plain Constantine. As the last of Greece’s deposed monarchs he escaped lightly. But decades of exile in London, as one thing the Greeks did not want back from Britain, were not how he would have chosen to spend his life. For more than 20 years he was careful not to stir up anti-monarchist feeling in Greece, though he never relinquished his claim to the throne.

But Greeks have long memories. When the Greek colonels seized power in 1967, instigating seven years of tyranny, it was King Constantine who tried to stand up to them and rally the forces of democracy; but he did so rather naively and feebly.

Had Constantine succeeded, as did his brother-in-law Juan Carlos of Spain, he might have been a hero to his people. As it was, in the eyes of many Greeks, he remained tainted by family history and by his own clumsy mishandling of the political crisis that had brought about his exile. It’s a mistake he has freely acknowledged during the long 46 years of exile from his homeland.

There are Greeks still today who have always felt the referendum to depose him as King was rigged. For his part, Constantine, always continued to support democracy and the republic. Except with one caveat. According to many, Constantine never accepted his deposition. His Danish diplomatic passport still read "Constantine, King of Greece." In an interview with the television channel Skai in 2016, he even said: "I am not the former King Constantine, I am King Constantine, period."

In public at least, his fidelity to the republic bore fruit when he was allowed to come back to Greece and reside there. By all accounts his return from exile was a happy one where his home in Peloponnese coast gave him the peace he so long craved to live and eventually die in his own homeland. "All Greeks who live in exile want to return. It's in their blood," And so he got his wish. He was buried as a Greek, if not as a king.

RIP King Constantine II of the Hellenes (1940-2023)

#king constantine II of the hellenes#constantine II#greece#quote#royalty#monarchy#history#politics#coup#exile#king constantine II of greece

44 notes

·

View notes

Photo

By the standards of the hapless Greek monarchy, Constantine II, the last king of the Hellenes, who has died aged 82, led a comfortable life in exile after a brief and turbulent reign. Of the seven Greek monarchs of the 19th and 20th centuries, three were deposed, one assassinated, two abdicated and one died of septicaemia after being bitten by a barbary ape in the royal gardens.

The Glücksburg monarchy was German-Danish in origin, imposed on Greece in the 1830s. During prolonged wrangling after Constantine’s deposition, the Greek government refused to give him a passport until he acknowledged that he was Mr Glücksburg, whereas he insisted he was just plain Constantine. As the last of Greece’s deposed monarchs he escaped lightly. But decades of exile in London, as one thing the Greeks did not want back from Britain, were not how he would have chosen to spend his life.

In Hampstead Garden Suburb, Constantine lived in some state – apparently supported largely by donations from Greek monarchists – and visitors were expected to address him as Your Majesty. He was included in many invitations by the British royal family, to whom, like most of Europe’s monarchies, he was related. Prince Philip was his father’s first cousin, King Charles III his second cousin and Queen Elizabeth II a third cousin, and he was a godfather to Prince William. His wife was a Danish princess, the sister of Denmark’s Queen Margrethe II, and his sister Sofía became queen of Spain. Only in Greece was he unrecognised, and he was not allowed to return to live there until 2013, long after the events that had toppled him from the throne after a military coup in 1967 and resulted in the abolition of the monarchy in Greece in 1973.

In many ways, Constantine was a victim of the vicious political infighting that has characterised Greek politics and its society for much of the period since the second world war. It perhaps needed a stronger, more experienced and more resolute approach to surmount the crises of his three-year reign than the young man in his early 20s could manage. In later life he said in an interview that he might have liked to be an actor or a journalist, but his fate was to spend his life as an ex-king, harried by Greek politicians and in turn harassing them in a prolonged legal fight for compensation for his family’s lost property, eventually through the European court of human rights.

Born in Athens, Constantine was the son of the Greek crown prince, Paul, the younger brother of King George II, and his German-born wife Princess Frederica, and was taken into exile as a baby following the Italian and then Nazi invasions of the country in 1940-41. His early years were spent first in Egypt and then in South Africa, before the family returned to Greece following the referendum that restored George to the throne in 1946. George died the following year, and Paul became king.

Constantine was educated at a private high school in Athens, modelled on the same lines as the German educationist Kurt Hahn’s principles at Gordonstoun, and afterwards attended Athens University to study law. A keen sailor, Constantine was a member of Greece’s winning sailing team at the 1960 Rome Olympics – the country’s first gold medal in nearly 50 years.

He succeeded to the throne aged 23 on his father’s death in March 1964, becoming head of state in a country that had not got over the civil war between communists and the Greek government of 1946-49, and where political tensions and divisions continued to run deep. The CIA, desperate to avoid Greece falling into communist hands, was also active in Athens. Greece was a strategic pawn between the US and the Soviet Union, each anxious to pull the country into its sphere of influence in the eastern Mediterranean. At the same time, it was attempting to modernise with social and economic reforms as an associate member and applicant to join the Common Market.

The month before Constantine came to the throne, a general election had produced a centrist – moderate, leftwing – government under George Papandreou, following 11 years of rightwing government. Within a year, relations between the king and his prime minister were breaking down. Conservative army officers were alarmed by a perceived leftwards drift among the junior ranks, who were supported by Papandreou’s Harvard-educated son Andreas. When George Papandreou announced that he would take over the defence ministry himself, Constantine refused to allow him to do so, and the government resigned. In the hiatus that followed, the king attempted to appoint a government without holding an election and was accused of acting unconstitutionally.

When elections were finally called in April 1967, the likely re-election of Papandreou was forestalled by an army coup led by colonels. Constantine initially appeared to go along with the insurgents. He argued later that he had had no choice as the palace was surrounded by army tanks, but there were also persistent suggestions that he had been urged by the American embassy to do so in order to avoid another radical government. Many Greeks and civilian politicians never forgave the king for acceding to the coup, but within months he attempted a counter-coup of his own, fleeing to loyalist troops in the northern city of Kavala that December in an attempt to create a rival military support and force the junta to resign.

The operation was poorly organised and, although the air force and navy declared their support, the army and its officers rallied to the coup leaders. Support for the king melted away within 24 hours. Fearing bloodshed if it came to a military confrontation, Constantine and his family fled into exile, first in Rome and then a few years later in London.

There was no going back for the king. The junta, led by Colonel Georgios Papadopoulos, brutally consolidated their regime using censorship, mass arrests of opponents, torture and imprisonments, and were not going to reinstate Constantine after his attempted coup. When monarchist navy officers unsuccessfully attempted to overthrow the colonels in June 1973, Papadopoulos declared the country a republic, endorsed subsequently in a plebiscite widely assumed to have been rigged.

Nonetheless, when the regime fell following the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974, to be succeeded by a civilian government, a further referendum was held to determine whether the king should be restored. Constantine was not allowed to return in order to campaign on his own behalf, though he was allowed to broadcast an address from London in which he apologised for his previous errors. But his maladroit interference with the civilian governments before the coup was held against him and the outcome of the vote in December 1974 was heavily in favour of a republic: by 69% to 31%.

Thereafter, for decades, Constantine was prevented from visiting Greece except briefly and on rare occasions: for his mother’s funeral in 1981 and for an attempted holiday in 1993, when he found his yacht was constantly harried by torpedo boats and aeroplanes. The following year, the Greek government revoked his citizenship and passport and seized the royal family’s property. “The law basically said that I had to go out and acquire a name. The problem is that my family originates from Denmark and the Danish royal family haven’t got a surname,” he said, adding that Glücksburg was the name of a place not a family: “I might as well call myself Mr Kensington.”

In 2000, the court of human rights found for the king in relation to the property, though it could only order compensation, not the return of his extensive estates nor the royal palace at Tatoi and awarded him only 12m euros (around £10m), rather than the 500m he had asked for: a reduction that the Greek government counted as a triumphant vindication. It nevertheless took another two years to pay the money and, when it did so, the government took it from its extraordinary natural disasters fund rather than general reserves. In retaliation, Constantine used the money to set up a charitable foundation in the name of his wife to assist Greeks suffering from natural disasters. He said: “I feel the Greek government have acted unjustly and vindictively. They treat me sometimes as if I am their enemy – I am not the enemy. I consider it the greatest insult in the world for a Greek to be told he is not a Greek.”

Generally, while expressing a wish to be allowed to live in Greece, which was granted in 2013, Constantine seemed equable about his fate and did not attempt to regain the throne. “All I want is to have my home back and to be able to travel in and out of Greece like every other Greek. I don’t have to be in Greece as head of state. I am quite happy to be there as a private citizen,” he told the Sunday Telegraph in 2000. “Forget the past, we are a republic now. Let’s get on with the future.”

Constantine is survived by his wife, Princess Anne-Marie of Denmark, whom he married in 1964; and their three sons, Pavlos, Philippos and Nikolaos, and two daughters, Alexia and Theodora.

🔔 Constantine II, former King of Greece, born 2 June 1940; died 10 January 2023

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Greek media continue to insist on the fact that William and Catherine (+Edward) will join Anne for King Constantine II's funeral tomorrow despite royal reporters only confirmed Anne's attendance. According to this article, BP and KP won't confirm William and Catherine's attendance because they would attend the funeral in private capacity and not officially...

I don't know if that's true but let's see tomorrow 👀

#king constantine#king constantine ii#greek royal family#prince william#prince of wales#princess of wales#princess anne#princess royal#prince edward#earl of wessex#british royal family#england#2023#january 2023#greece#king constantine ii's death#king constantine ii's funeral#funeral

21 notes

·

View notes