#kgb treblinka

Quote

“El amor se parece al carbón; cuando está candente quema; y cuando está frío ensucia”

Vasili Grossman

Fue un escritor y periodista soviético judeoruso, nacido en Berdychiv Imperio ruso, en diciembre de 1905. Publicó varias decenas de relatos cortos y algunas novelas largas y, tras el estallido de la Segunda Guerra Mundial se convirtió en corresponsal de guerra para el ejercito rojo.

Nace en el seno de una familia burguesa cultivada de origen judío. Su padre era bundista, es decir, afiliado a un movimiento politico judío de corte socialista, e ingeniero químico de profesión. Su madre era profesora de francés tras haberse formado en Francia.

A partir de 1927, su pasión por la ciencia decae y en su lugar lo ocupa su interés por la literatura. No obstante, en 1929, obtiene el titulo de ingeniero químico, contrayendo matrimonio en el mismo año.

En 1930, trabaja en una mina, pero tras una hambruna en la region de Ucrania, se instala en Moscú en donde trabaja en una fabrica de lápices. En 1932 se divorcia de su esposa y comienza a sufrir las consecuencias de las primeras purgas estalinistas.

En 1934, abandona definitivamente su empleo de ingeniero para dedicarse de lleno a la escritura, su primer libro titulado “La ciudad de Berdychiv” se publica en 1934, y muestra la vida de una familia judía pobre. Recibe el reconocimiento de Máximo Gorki, escritor y politico ruso, de Issak Bábel, escritor y periodista ruso que mas tarde seria detenido, torturado y ejecutado durante la gran purga de Stalin, y de Mijail Bulgákov, escritor, dramaturgo y médico ruso.

En junio de 1941, cuando Alemania invade a la Unión Soviética, Grossman se alista como periodista para el diario “La estrella Roja”, el diario del Ejercito Rojo, y parte hacia el frente en agosto de 1941, en donde es testigo de la falta de preparación del ejercito, escapando de la debacle surgida en la batalla de Kiev en dos ocasiones.

En 1942, es enviado a Stalingrado, en donde es testigo de meses terribles en el frente de batalla, y de donde tomaría experiencia y material para sus dos obras maestras tituladas “Por una causa justa” y ”Vida y destino”.

Cuando el ejercito rojo logra recuperarse del asedio aleman, Grossman recibe la orden de dejar Stalingrado y de ser remplazado, por lo que lo considera una tradición. Es enviado a Calmuquia, participando en 1943 en las batallas de Kursk y la batalla de Dniéper

Durante el otoño de 1943, es reclutado para el comité Judío Anti-Fascista, y en Ucrania progresivamente liberada, Grossman descubre la amplitud de las masacres cometidas contra los judíos.

En julio de 1944, Grossman es testigo de los campos de concentración de Majdanek y Treblinka, lo que lo convierte en la primera persona en describir los campos de exterminio nazis. Su relato “El infierno de Treblinka”, serviría de testimonio en los juicios de Nuremberg.

Después de la guerra en 1946, el regimen optó por dar un giro en materia de literatura y en 1948, el comité Judío Anti-fascista es disuelto. El antisemitismo de estado sale a la superficie en 1949, y para Grossman ese suceso supone la demostración del paralelismo entre los regímenes nazi y soviético, que finalmente se tocan en el antisemitismo.

Aunque Grossman nunca llegó a ser arrestado por las autoridades soviéticas, sus dos obras maestras (Vida y destino y Todo Fluye) fueron censuradas durante el periodo de Nikita Jrushchov como antisoviéticas. La KGB registró su departamento después de que completase “Vida y destino” en busca de manuscritos, notas, e incluso las cintas de máquinas de escribir. Cuando Grossman falleció, en 1964, “Vida y destino” permanecía inédita.

“Vida y Destino” fue publicada en 1980 en Suiza, gracias a una pequeña red de disidentes soviéticos, pasando de contrabando microfilms con la obra fotografiada secretamente por el físico Andréi Sajárov, y finalmente, publicada oficialmente en la Unión Soviética en 1988 gracias a la política de Glásnot iniciada por Mijaíl Gorbachov. Es considerada como una de las cumbres literarias del siglo XX. “Todo Fluye”, fue también publicada en la Unión Soviética en 1989.

Fuente Wikipedia.

#frases#frases celebres#citas de reflexion#frases de la vida#citas de escritores#escritores#rusia#notas de vida#notasfilosoficas#citas de la vida

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Those of Jewish faith seem understandably predisposed to persecutory vengeance even if an accusation can't be proven or is difficult or outright questionable.

So many records were burned after the fall of the reich, many more were collected by the Red Army (including blank identification templates) and then promptly sealed within the KGB governmental files.

I think it's not unreasonable to accuse Ivan "John" Demjanjuk of being a guard at Sobibol or even Treblinka (many Red Army POWs were), but to base your whole case on whether Demjanjuk was a specific Nazi-collaborating guard called Ivan was destined for failure. Trying to prove Demjanjuk was specifically Ivan the Terrible is why the state of Israel lost that case at the Israeli Supreme Court. I'm convinced of it.

6 notes

·

View notes

Link

Single Treblinka KGB 1983 Dro.

0 notes

Text

Also for anyone who isn't really familiar with the Grossman duology (Stalingrad and Life and Fate), it is ABSOLUTELY a condemnation of Soviet ideology. So much so that the author, Vasily Grossman (Iosif Solomonovich Grossman), was targeted for it and his books banned. Life and Fate was seized by the KGB. It is a minor miracle he was not actually arrested for it.

He was a Ukrainian Jew who saw first hand the n*zi death and concentration camps (Treblinka and Majdanek) as they were being liberated and became one of the first reporters to give an account of them. He tried at first to join the Soviet military but was likely denied for his anti-commie sentiment and the fact he was Jewish. So instead he became a reporter on the front lines in World War 2.

Stalingrad is the first book in the duology (and published in 1952) and there are a lot of lines that seem to be pro-communism but that's generally being spouted by characters loyal to the regime but Life and Fate has a far more biting criticism of communism and was written in the late 1950s and it took until the 1980s for it to be published (it also mostly follows a Soviet Jew).

A revised English translation of both books was published back in 2019, including his preferred title for Stalingrad which was originally called For a Just Cause (and had not been published in English until 2019).

#vasily grossman#life and fate#stalingrad novel#holocaust mention /#anti communism tag#antisemitism tag /

0 notes

Photo

Auschwuitz, Polônia - Campo de Extermínio Nazista  Casa de Ernest Hemingwey - Finca Vigia, San Fco de Paula, Cuba  Apartamento onde viveu Lautréamont - Montmartre, Paris  No Rastro de David Ben-Gurion, Deserto de Néguev, Israel  Margaret Mitchell House, autora do Clássico "E o Vento Levou" - Atlanta, Georgia  No Rastro de Immanuel Kant, em Kaliningrado - Rússia Muralhas da China, Mutianyu, China - trecho edificado no ano 206 a.C. Casa de Boris Pasternak em Peredelkino, Rússia Next Cover - The Last Songs of Autumn Monument Valey, Arizona EUA Recepção na Casa de Edgar Alan Poe, Baltimore - EUA Tumba de Theodor Herzl no Monte Herzl, Cemitério Nacional de Israel, lado oeste de Jerusalém. Prêmio de Ficção na Academia Brasileira de Letras Pesquisando na KGB, Moscou Homenagem da Escola Johnson, Fortaleza. Treblinka, Campo de Extermínio Nazi, Polônia Castelo de Braan (Conde Drácula) na Transilvânia Ketchikan Gateway, Alaska, fundada em 1868 Stalingrado, hoje Volgorado, Rússia Novosibirsk, Sibéria Odessa, Ucrânia Prêmio de Ficção pela Academia Brasileira de Letras, Melhor Romance de 2004, Editora Record Lançamento do romance CANTOS DE OUTONO na Academia Brasileira de Letras Mark Twain House, in Hartford, Connecticut  William Faulkner House Beijing, China Capa » BIBLIOTECA (Textos do Autor) » PARÁBOLA DO BURRO  PARÁBOLA DO BURRO  Havia um burro amarrado a uma árvore. Veio o demônio e o soltou. O burro entrou na horta dos camponeses vizinhos e começou a comer tudo. A mulher do camponês dono da horta, quando viu aquilo, pegou o rifle e disparou. O dono do burro ouviu o disparo, saiu, viu o burro morto, ficou louco de raiva, pegou seu rifle e atirou contra a mulher do camponês. Ao voltar para casa, o camponês encontrou a mulher morta e se vingou matando o dono do burro. Os filhos do dono do burro, ao verem o pai morto, queimaram a fazenda do camponês. O camponês, em represália, os matou à bala. Aí perguntaram ao demônio o que ele havia feito para causar tamanha desgraça e ele respondeu: – “Não fiz nada, só soltei o burro”. Conclusão, Se você quiser destruir um país, Solte o Burro. https://www.instagram.com/p/B4Hy_j5FuLf/?igshid=4c8mhhd4ojjy

0 notes

Text

alright, time to make a few bullet points about erik and whatnot. there are going to be some things changed from the movie to incorporate some 616 stuff so that shall all be under the cut. there are some triggering things that include death and the holocaust so be cautious if that is stuff that triggers you.

before he became erik lehnsherr, he was known as max eisenhardt. he attended school in nuremburg, germany, and it was during this time that he fell in love with a young romnai girl named magda. in school he had a pretty difficult time because kids are assholes, but that was the least of his worries during this time in his life.

it all began in october of 1940 when the nazis turned the jewish section of warsaw into the warsaw ghetto. max became a smuggler in order to get food and supplies that were needed for his family. however, inhabitants of this area were soon being deported to the treblinka extermination camp in july of 1942. max and his family escaped from warsaw, but on the way to their hideout they were captured by nazi soldiers and his family was executed.

max was saved only because his father, jakob, pushed him out of the line of firing without anyone's notice. but, he was eventually found and was taking to auschwitz.

things were horrible in the camp for him. he served in the sonderkommando, which were the squad of jewish men that were forced to help the nazis run the gas chambers, ovens, and fire pits at the camp. max was forced to put dead bodies into the fire pits to have them burned. he saw a lot of death during his time in the camp.

max was reunited with magda in the camp, however. he did anything he could do to help her survive, such as smuggling food and supplies for her. he saved her from the has chambers, as well as execution later on and during the sonderkommando revolt, they escaped together and lived in carpathian mountain village and married. they had a daughter named anya, who meant absolutely everything to him. it was during this time that max changed his name to erik lehnsherr, an identity that belonged to a deceased member in the village that they lived in. he eventually moved his family to the city of vinnista in order to better himself where he got a job and had hoped to settle down. of course, nothing went according to plan.

erik was being cheated out of pay, so unconsciously he used his newly manifested powers to lunge a crow bar at his boss. this resulted in the boss calling the KGB, and he had to watch his home burn while his daughter died in the fire. erik then used his powers to kill everyone there. magda saw the entire thing and she was absolutely terrified of erik and ran from him. he hasn’t seen her since, has no idea where she is.

that’s where the story will resume with first class where erik was hunting down shaw and all of the events in the movie

erik has been in maximum security at the pentagon for the last 10 years as per days of future past. he’s had a long time to perfect building walls in his mind and filing away his thoughts. so it’s a bit more difficult for a telepath to get into his head now even without the helmet. but of course erik got his helmet after he was busted out of the pentagon so there’s that

the only reason that erik is willing to help those from the future is for the mutants. he doesn’t give a shit about the heroes or anyone else being killed by the sentinels. his only care is always for his own kind.

he is still the leader of the brotherhood of mutants to those that have survived over the years, and since he is out of prison, he has begun to rebuild his brotherhood.

erik can be nice. he can be very civil with people. but, he can also be cruel and cold to those that he doesn’t like, or that piss him off. he can be quick to violence since that is often his first choice to deal with things.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

NETFLIX DOCUMENTARY MASTERLIST ;

A masterlist of my favorite documentaries on Netflix. They’re split up into the genres that they’re in on Netflix, although some might be found in multiple genres. You can also read their descriptions on the list as well. If this list helped you, I’d love if you'd consider buying me a coffee to help me out. Thank you. Enjoy! xo

BIOGRAPHICAL DOCUMENTARIES ;

Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer —

This documentary “looks at serial killer Aileen Wuornos' tortured childhood and subsequent years as a hitchhiking.”

Josef Fritzl: Story of a Monster —

Pointed interviews and rare footage reveal the horrific case of Josef Fritzl, who for decades brutalized and sexually assaulted his own daughter.

Audrie & Daisy —

Two teenage girls experience brutal attacks. But in the age of social media, their nightmares are only beginning.

The Imposter —

A documentary centered on a young man in Spain who claims to a grieving Texas family that he is their 16-year-old son.

Aileen Wuornos: The Selling of a Serial Killer —

This mesmerizing documentary explores the troubled life and deadly end of serial killer Aileen Wuornos, a woman who murdered johns.

My Friend Rockefeller —

Clark Rockefeller: He was a best pal, a surrogate son, a charming dinner guest. He was also a con man and a killer.

Death Camp Treblinka: Survivor Stories —

Treblinka: The darkest, most primitive of the Nazi concentration camps. Only two survivors remain to tell their stories.

A Nazi Legacy: What Our Fathers Did —

It’s not easy to make peace with the past. When your fathers took part in the century’s darkest crime, it’s impossible.

Bound by Flesh —

Take a peek behind the freak show curtain to see how America’s most famous Siamese twins were also famously exploited.

H. H. Holmes: America's First Serial Killer —

This film looks at the life of H.H. Holmes, America's first serial killer, who designed his Chicago home with a torture chamber in the late 1800s.

CRIME DOCUMENTARIES ;

Killer Legends —

What if some of the most horrifying stories you ever told turned out to be true?

Matt Shepard Is a Friend of Mine —

This documentary chronicles the life of Matthew Shepard, whose infamous 1998 murder left his friends and family devastated.

Dear Zachary: A Letter to a Son About His Father —

Filmmaker Kurt Kuenne's tribute to his murdered childhood friend, Andrew Bagby, tells the story of a child custody battle won by Bagby's ex-girlfriend and accused killer.

Sleepwalkers Who Kill —

This documentary takes a serious look at a rare medical and legal condition that has turned ordinary people who sleepwalk into unwitting killers.

Manson’s Missing Victims —

The infamous mass killer had a very large family. What happened to the ones that weren’t so loyal?

Murder on the Social Network —

Using real cases, this documentary demonstrates the extent to which violent criminals can use social media to locate and manipulate victims.

The Confessions of Thomas Quick —

A serial killer whose crimes were so horrific they scarred a nation. Then someone started checking the story.

HISTORICAL DOCUMENTARIES ;

Auschwitz: The Nazis and the 'Final Solution' —

Eyewitnesses recall how those in power stole from Jewish inmates, and how inmates were the subjects of horrific experiments.

The Seven Dwarfs of Auschwitz —

Actor Warwick Davis traces the ordeal of the Ovitz family, a troupe of Jewish dwarf performers subjected to experiments by Nazi doctor Josef Mengele.

Auschwitz: Blueprints of Genocide —

Newly released KGB files expose evidence proving how architects and engineers conspired with the Nazis to build a camp designed for genocide.

Titanic’s Final Mystery —

Icberg, right ahead! How did it seem to come out of nowhere? This illusion has to be seen to be believed.

SCIENCE & NATURE DOCUMENTARIES ;

Planet Earth —

Dazzling imagery highlights this breathtaking documentary series featuring footage of some of the world's most awe-inspiring natural wonders -- from the oceans to the deserts to the polar ice caps.

Blackfish —

This fascinating documentary examines the life of performing killer whale Tilikum, who has caused the deaths of several people while in captivity.

Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey —

Astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson presents new revelations about time and space in this reboot of the original “Cosmos” documentary series.

Ocean Giants —

A documentary series granting a unique access into the magical world of whales and dolphins.

The Blue Planet: A Natural History of the Oceans —

Although two-thirds of the world's surface is covered with water, scientists know less about the oceans than they do about the surface of the moon. Sir David Attenborough narrates this documentary series that dives deep into the marine environment of Planet Earth.

SOCIAL & CULTURAL DOCUMENTARIES ;

Jesus Camp —

This documentary follows three kids at a controversial summer camp that grooms the next generation of conservative Christian political activists.

Married, Single, Dead —

This documentary shares the disturbing stories of four British women killed by their exes after changing their relationship status on Facebook.

Men in Rubber Masks —

This documentary spotlights “female maskers”, mean who transform themselves into lifelike female dolls with silicone masks and bodysuits.

Revenge Porn —

This eye-opening investigation of so-called “revenge porn” shows how easily a sexually charged share can go public if it gets into the wrong hands.

Room 237 —

This fascinatying documentary explores various theories about hidden meanings in Stanley Kubrick’s classic film The Shining.

After Porn Ends —

When the hedonism is over, the search for normality begins. But having a dirty past can leave its mark.

Into the Abyss —

After a murder spree, survivors and killers collide in a state-sponsored execution. Is it justice to kill a killer?

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

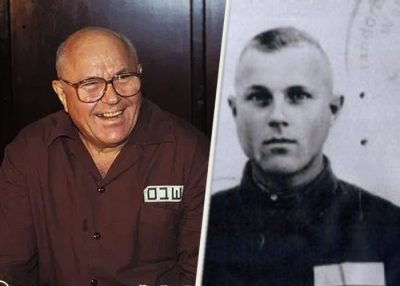

"Iván el Terrible: el operador de la cámara de gas de Treblinka"

Uno de los casos que mas impacto a la sociedad en 1985, llevándonos hacia los horrores cometidos en el Holocausto. ¿Pero quien era Iván el terrible? , Iván John Demjanjunk, era un Ucraniano que desempeñaba su labor como guardián del campo de exterminio de Sobibor. ¿Pero porque le decían el operador de gas de Treblinka si se encontraba en Sobibor?, Iván Demjanjunk fue confundido con Iván Marchenko quien era un compañero nazi de él, Demjanjunk enfrento varios juicios por las causas imputadas que denunciaron los sobrevivientes del holocausto, pero en un juicio en Israel en 1988 se descubrió que estos actos en realidad no fueron perpetrados por él, si no por Marchenko, quien era un hombre cruel que operaba en los campos de exterminio en Treblinka, cometía actos inmorales hacia las victimas desde cortar orejas hasta los senos de las mujeres con tal de demostrar su poder y crear miedo a los prisioneros del holocausto.

Si bien Demjanjunk no perpetro estos crímenes en Treblinka no era del todo inocente ya que sí llevó a cabo actos criminales en los campos en los que sirvió. Tras ser enviado al campo de detención de Chelmno, en Polonia, Demjanjuk aceptó colaborar con las temidas SS, y tras recibir entrenamiento en el centro de formación de se le hizo entrega de un arma y un carné que lo identificó como guardián de las SS. Unos 29.000 judíos, la mayoría polacos, fueron asesinados en las cámaras de gas, la cuales era manejadas por el propio Demjanjuk, el cual las ponía en marcha y se ocupaba de hacer ingresar a los prisioneros en su interior.

En mayo de 1945, una vez acabada la guerra, Iván se presentó en uno de los campos instalados en Alemania para "personas desplazadas", en 1947 trabajó como conductor en una empresa estadounidense en Regensburg (Alemania), donde se casó con una ucraniana y tuvieron una hija. Sus otros dos hijos nacerían ya en Estados Unidos, país al que la familia emigró en 1952. En 1958 obtuvo la nacionalidad estadounidense, ademas cambio su nombre por "John" y se instaló en Indiana y más tarde en Cleveland (Ohio), donde trabajó en la compañía Ford. No sería hasta 1985 cuando surgió la noticia de que un hombre de 66 años llamado John Iván Demjanjuk, un operario ya jubilado de la fábrica de Ford en Cleveland, podía ser un criminal de guerra y es así como comienza el juicio contra el supuesto "Iván el terrible", fue condenado a la horca en 1988, pero el KGB ruso aportó pruebas que demostraban que Demjanjuk no era "Iván el Terrible", el asesino de Treblinka, por lo que, en 1993, el Tribunal Supremo israelí al final tuvo que retirar la condena y permitir a Demjanjuk regresar a Estados Unidos. En 2001 el Departamento de Justicia estadounidense retomó el caso.

En julio de 2009, la fiscalía alemana acusó a Demjanjuk de ser cómplice en el asesinato de 28.060 personas en el campo en Sobibor. Tras seis meses de juicio, el proceso se cerró a mediados de marzo de 2011, y el 12 de mayo de 2011, Demjanjuk fue declarado culpable y condenado a cinco años de prisión, pero su avanzada edad (en aquella época tenía ya 91 años) provocó que el tribunal de Múnich decidiera ponerlo en libertad después de emitir un veredicto de culpabilidad. Finalmente murió en un asilo de ancianos alemán el 17 de marzo de 2012.

Después de todo, aunque no sea el operario de Treblinka nunca fue un hombre inocente.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Vasily Grossman and the Soviet Century by Alexandra Popoff

If Vasily Grossman’s 1961 masterpiece, Life and Fate, had been published during his lifetime, it would have reached the world together with Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago and before Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag. But Life and Fate was seized by the KGB. When it emerged posthumously, decades later, it was recognized as the War and Peace of the twentieth century. Always at the epicenter of events, Grossman (1905–1964) was among the first to describe the Holocaust and the Ukrainian famine. His 1944 article “The Hell of Treblinka” became evidence at Nuremberg. Grossman’s powerful anti‑totalitarian works liken the Nazis’ crimes against humanity with those of Stalin. His compassionate prose has the everlasting quality of great art. Because Grossman’s major works appeared after much delay we are only now able to examine them properly. Alexandra Popoff’s authoritative biography illuminates Grossman’s life and legacy.

The post Vasily Grossman and the Soviet Century by Alexandra Popoff appeared first on Jewish Book World.

from WordPress https://ift.tt/30DhQ0Z

via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

Aquí te va una canción para ti… Treblinka de KGB

https://open.spotify.com/track/0N0mgxelaSBNX1ipUz60a1?si=ZLuSq9_ATeCEEy2W09a8Xw

0 notes

Text

“Scrissi del mio amore per gli esseri umani e della mia solidarietà con il loro dolore”: Vasilij Grossman, uno scrittore contro il potere

Una scena mi è parsa emblematica. L’emblema, straordinario e straziante per esattezza, dei rapporti tra lo scrittore e la Storia, tra la scrittura e l’esercizio del potere. Il potere, esemplificato da una costruzione astratta – che sia lo Stato, il Tribunale, la Legge, la sopraffazione di un regime – che impedisca l’affronto frontale, non manda più al rogo l’eretico, non brucia più i libri del poeta, esaltandone la carica incendiaria. Confisca. Ruba. Custodisce in casse caine. Provai, tempo fa, a scrivere in modo ‘teatrale’ dell’episodio, per me una icona, accaduto a Vasilij Grossman. Lo ricalco.

*

“Immaginate. Chiudete gli occhi. Ampliateli, come candele. Immaginate. Immaginare che abbiano messo il vostro cuore in un cassetto.

Il palazzo è enorme. Una città. Anzi, no, un alveare. Un immenso alveare di cemento. In questo alveare gli uffici sono tantissimi. Infiniti. In alcuni uffici è accesa la luce. In altri no. Chi vi lavora? Che lavoro si svolge? Noi non lo sappiamo. Sappiamo che quello è il cuore dello Stato. Il cuore del potere. E che in uno di quegli uffici, ma non sappiamo quale, c’è una cassettiera. E che in un cassetto di quella cassettiera c’è il vostro cuore.

Come sonnambuli, ansimanti, vagate per la città oceanica, caracollate per Mosca. Come corpi senza un cuore. Guardate quel palazzo, che ha il ruolo di incutere terrore. Sembra un giaguaro di cemento, in effetti. Guardate quel palazzo e sapete che da qualche parte, lì c’è il vostro cuore. E che il vostro cuore vi è stato sottratto per sempre. Hanno messo il vostro cuore in un cassetto.

Siamo nella primavera del 1962. Lo scrittore Vasilij Grossman scrive a Nikita Chruščëv, Presidente del Consiglio dei Ministri dell’Unione Sovietica. “A metà febbraio 1961 ufficiali del KGB si presentarono a casa mia con un mandato di perquisizione e requisirono varie copie e abbozzi del manoscritto di Vita e destino. Simultaneamente, vennero sequestrate anche le copie consegnate a Znamja e Novyj Mir. Questo segnò la fine delle mie speranze di veder uscire un lavoro, che mi aveva richiesto dieci anni di sforzi”.

Il cuore di uno scrittore è la sua opera. Vasilij Grossman era ebreo, ma era un ebreo che non creava problemi. Intelligente, ateo, aderì all’ideologia comunista: durante la Seconda guerra è sul campo di battaglia, a Stalingrado. Scrive dei reportage di guerra straordinari; i suoi romanzi strappano gli applausi dei ‘compagni’: è uno scrittore allineato. Che presto diventa un alienato. Cosa accade? Accade che Grossman capì che i metodi dei nazisti non erano diversi da quelli proposti da Stalin. Capì che il ‘bene di Stato’ provoca stermini, che la ‘ragion di Stato’ crea i Gulag e i campi di concentramento. Così, Grossman si concentra, passa dieci anni a scrivere Vita e destino. E quel romanzo gli viene sequestrato. Non lo vedrà mai più. «Il Suo lavoro è pericoloso per il popolo sovietico. La sua pubblicazione sarebbe nociva non solo per il popolo sovietico e per lo Stato sovietico, ma anche per tutti coloro che stanno lottando per il comunismo al di là dei confini dell’Unione Sovietica, per tutti quei lavoratori progressisti nei paesi capitalisti, per tutti coloro che lottano per la pace. Il Suo romanzo farebbe il gioco del nemico»: così gli dice Michajl Suslov, burocrate di regime, censore stipendiato, il 23 luglio del 1962. Nel 1962 nascono i Beatles e muore Marilyn Monroe, esce il primo film della serie 007 e il Presidente Kennedy lancia la sua sfida per conquistare la Luna, ed è John Steinbeck a vincere il Nobel per la letteratura. Beh, in quello stesso 1962 un dirigente pubblico dice al più grande scrittore del suo paese che «I nostri scrittori sovietici devono solamente produrre ciò che serve ed è utile per la società». Dice che il romanzo di questo scrittore, Vita e destino, definito il più possente romanzo sul male del Novecento e sull’ostinazione al bene, sarà sequestrato. Non lo bruceranno. Badate. Non lo distruggono. Lo sequestrano. Solo così il regime può tenere in mano il cuore dello scrittore. Ma qual era la colpa di Grossman? “Facendo del mio meglio con le mie limitate capacità, scrissi sulle persone comuni, il loro dolore, le loro gioie, i loro errori e le loro morti. Scrissi del mio amore per gli esseri umani e della mia solidarietà con il loro dolore”, così dice lui. Questa, questa è la colpa. Cosa è successo? Succede che la scrittura è sempre, quando è autentica, ostile al potere”.

*

Vasilij Grossman muore quando gli sottraggono Vita e destino, perché il destino di uno scrittore è legato alla propria opera; poi muore, ancora, nel corpo, neanche sessantenne, nel 1964, 55 anni fa. In Italia, fino a poco fa, c’è stata una specie di ubriacatura per Grossman. I suoi libri sono editi da Adelphi – Vita e destino, il capolavoro immane, ma anche L’inferno di Treblinka, così necessario. Un bel libro per conoscere Grossman lo ha pubblicato Marietti dieci anni fa, si intitola Le ossa di Berdičev. La vita e il destino di Vasilij Grossman, ed è scritto da due studiosi americani, John e Carol Garrard. A Torino esiste anche uno Study Center Vasilij Grossman. Fatto è che l’ultimo libro di Grossman è stato pubblicato da Adelphi nel 2015, Uno scrittore in guerra, una raccolta di reportage dal cuore della Seconda guerra.

*

Piuttosto, nel mondo anglofono si torna a parlare di Grossman con una certa effervescenza. I pretesti editoriali – connessi all’anniversario della morte – sono due. Da un lato la pubblicazione di una nuova biografia, Vasily Grossman and the Soviet Century, a cura di Alexandra Popoff per la Yale University Press (che ha offerto, in questi giorni, a Sheila Fitzpatrick il crisma per una articolessa, A Complex Fate. Vasily Grossman in war and peace pubblicata su “The Nation”). Dall’altro, soprattutto, è la pubblicazione di Stalingrad – cioè: “Per una giusta causa” – scritto nel 1952, che costituisce il prototipo e il precursore di Vita e destino, il romanzo che ne anticipa temi e personaggi, a galvanizzare la stampa anglofona. “Stalingrad è uno dei grandi romanzi del XX secolo, pubblicato per la prima volta in lingua inglese. In origine, Grossman immagina Stalingrad e Vita e destino, il suo capolavoro, come una singola opera organica. Stalingrad è un prequel di abbagliante splendore”, gorgheggia, dal Guardian, Luke Harding. “Stalingrad equivale a Vita e destino: è, indiscutibilmente, un libro più ricco, che si snoda attraverso le storie di uomini per concederci al senso della bellezza e della fragilità della vita”. Un paio di settimane fa – faccio del cerchiobottismo culturale – il Telegraph ha scritto di Stalingrad dicendolo “Un Guerra e pace del XX secolo”.

*

Vasilij Grossman ha descritto con raffinatezza il pitone del potere. In Tutto scorre… (Adelphi, 1987) le pagine su Lenin sono di micidiale lucidità. “In un dibattito Lenin non cercava la verità, cercava la vittoria… Tutte le sue facoltà, la sua volontà, la sua passione erano subordinate a un solo scopo: prendere il potere… La capacità di calpestare nel fango l’avversario senza scomporsi, di tramortirlo in un dibattito, si associava in modo incomprensibile al gentile sorriso, alla timida delicatezza. La spietata crudeltà, il disprezzo per la cosa più sacra alla rivoluzione russa: la libertà, e lì accanto, dentro il petto dello stesso uomo, il puro entusiasmo giovanile per una buona musica, un bel libro”. L’anamnesi di Stalin è egualmente impeccabile: “Nel carattere di Stalin, in cui l’asiatico si fondeva con il marxista europeo, si esprimeva il sistema del carattere statale sovietico. Lenin incarnava il principio nazionale russo storico, Stalin il sistema statale russo sovietico. Il sistema statale russo – nato in Asia ma abbigliato all’europea – non è storico ma metastorico… Dalla sua fede negli incartamenti burocratici e nella forza della polizia quale forza principale di vita, dalla sua segreta passione per le uniformi e le decorazioni, dal suo inaudito disprezzo della dignità umana, della sua deificazione dell’assetto ministeriale e burocratico, dalla sua disponibilità a uccidere un essere umano per amore della sacrosanta lettera della legge, e in quel punto stesso a disprezzare la legge per amore di un mostruoso arbitrio – saltava fuori la gerarchia poliziesca, lo spirito del gendarme”.

*

Si intitola La Madonna a Treblinka, però, alle mie orecchie, il testo miliare di Grossman (io lo leggo in una edizione fragile, che sta in una mano, stampata dalle Edizioni Medusa nel 2006; il testo è raccolto come La Madonna Sistina nel tomo Il bene sia con voi!, Adelphi, 2011). Qui Grossman racconta l’esposizione, a Mosca, del quadro di Raffaello, era il 1955, prima che lo stato sovietico lo restituisse alla Pinacoteca di Dresda. Quel quadro, di devastante dolcezza, dove la Madonna, una mamma, sembra vedere il volto, a falangi, di quelli che verranno a estirpargli il Figlio e a mangiarlo (“Madre e figlio sono come un unico essere, e tuttavia qualcosa li separa. Vedono insieme, hanno gli stessi pensieri, sono uniti – ma tutto induce a pensare che si separeranno, non può essere altrimenti, poiché l’essenza della loro unione consiste appunto nel fatto che dovranno separarsi”), diventa il centro del mondo, un’opera d’arte che custodisce l’uomo per varcarlo. “…e pur rimanendo intatta la mia enorme ammirazione per Rembrandt, Beethoven, Tolstoj, compresi che di tutto ciò che era stato creato da un pennello, da uno scalpello, da una penna – soltanto questo quadro di Raffaello non morirà finché sarà vivo l’uomo. Ma forse, se anche l’uomo morirà, altri esseri che resteranno sulla terra al suo posto – lupi, ratti, orsi, rondini – verranno, camminando o volando, ad ammirare la Madonna”. L’opera si incunea nella Storia, con nitore di stimmate: s’incarica di ogni essere, ha il dono di una commozione primordiale, prelogica. “Non c’è stato tempo più terribile del nostro – diremo – ma non abbiamo permesso che nel genere umano si estinguesse l’umanità. Contemplando la Madonna Sistina manteniamo la nostra fede nel fatto che vita e libertà siano inscindibili e non vi sia nulla di più alto dell’umanità dell’uomo. Questa umanità sopravvivrà in eterno, e vincerà”. Di fronte all’opera non c’è riconoscimento, ma riconoscenza. Non c’è niente da conoscere in ciò che toglie il fiato. Resta quello. La riconoscenza. La capacità di inginocchiarsi davanti alla cosa grande. (Davide Brullo)

L'articolo “Scrissi del mio amore per gli esseri umani e della mia solidarietà con il loro dolore”: Vasilij Grossman, uno scrittore contro il potere proviene da Pangea.

from pangea.news http://bit.ly/2Y1cF8G

0 notes

Text

Recensie van: Michel Krielaars: Alles voor het moederland, de Stalinterreur ten tijde van Isaak Babel en Vasili Grossman, Atlas Contact, 2017 (344 pagina’s)

Review:

De Russische revolutie van 1917 lichtte eerst het tsaristische regime uit het zadel en bracht enkele maanden later een bolsjewistische regering onder leiding van Vladimir Lenin aan de macht. De utopische droom van de Sovjet-Unie mondde echter al gauw uit in dictatuur, angst en bloedvergieten, met als gruwelijk dieptepunt de Grote Terreur onder Jozef Stalin. In dat tijdperk was niemand veilig en vreesde vrijwel iedereen de nachtelijke klop op de deur.

De historische feiten van dit ongure stuk geschiedenis kan je natuurlijk nalezen op Wikipedia. Om inzicht te krijgen over hoe deze periode werd beleefd en wat het teweegbracht in de hoofden van de mensen die het meemaakten, is Alles Voor Het Moederland van Michel Krielaars een beter startpunt.

Krielaars, chef Boeken bij NRC Handelsblad en gewezen correspondent in Moskou, brengt het beklemmende tijdperk tot leven aan de hand van twee joods-Russische schrijvers: Isaak Babel (1894-1940) en Vasili Grossman (1905-1964). Beiden waren populaire oorlogscorrespondenten, beiden geloofden aanvankelijk in de socialistische heilstaat en beiden werden gekende Sovjetschrijvers. Stalin bestempelde ze als ‘ingenieurs van de ziel’. Naarmate hun ogen echter open gingen voor de onmenselijkheid van het regime, verloren Babel en Grossman hun hoop in de communistische droom. En uiteindelijk gingen ze allebei aan de terreur ten onder.

Schrijverslevens

Alles voor het moederland laat je kennismaken met de levenslopen en het werk van deze twee bijzondere schrijvers. Ondanks zijn kritische werken ontsnapte Grossman wonderlijk genoeg aan een nekschot, al leefde hij wel voortdurend in angst en eindigde hij zijn leven als een gebroken man. Dat zijn meesterwerk Leven en Lot vele jaren later gepubliceerd raakte buiten de Sovjet-Unie, blijkt een klein wonder.

Minder fortuinlijk verging het Isaak Babel. Hij werd in mei 1939 gearresteerd door de NKVD (de voorloper van de KGB). Al zijn manuscripten werden in beslag genomen en nooit terug gevonden. Op bevel van Stalin kreeg hij de kogel.

Foto’s van Isaak Babel, gemaakt door de NKVD na zijn arrestatie in 1939 (Wikimedia Commons)

Het boek heeft echter veel meer te bieden dan deze schrijverslevens. Ruslandkenner Krielaars volgt de voetsporen van Babel en Grossman en schreef zo ook een meeslepend reisverslag over het hedendaagse Rusland en Oekraïne, doorspekt met persoonlijke verhalen en bespiegelingen. Hij spreekt met nabestaanden, historici en literatuurwetenschappers, waardoor het ook een goed gestoffeerd essay en een geschiedenisles is geworden. Krielaars is een bevlogen verteller en slaagt er wonderwel in om deze verschillende invalshoeken aan elkaar te breien tot een samenhangend en bij momenten bloedstollend verhaal.

Confronterende vragen

Alles voor het moederland bevat enkele huiveringwekkende hoofdstukken waarin de gruwel van zowel het Sovjet- als het naziregime aan bod komen. Met de bloedbaden van Berditsjev, Babi Jar en Treblinka richt Krielaars de spots op de pijnlijke en confronterende vragen die als een onzichtbare rode draad doorheen het boek lopen: waarom zijn mensen zo goedgelovig en sluiten ze zo makkelijk hun ogen voor onrecht en misdadige dictatuur? Hoe komt het dat zelfs brave huisvaders onmenselijke beulen kunnen worden, behekst door een giftige ideologie? En uiteindelijk: zou ik zelf zo intellectueel en moreel verlamd kunnen raken uit angst of blind idealisme?

Het belang van die laatste vraag onderstreept Krielaars met een treffende passage aan uit Alles Stroomt, de roman waar Grossman aan werkte na het voltooien van Leven en Lot:

Alleen mensen die die kracht zelf niet kennen, kunnen zich erover verbazen dat anderen zich eraan onderwerpen. Mensen die die kracht gevoeld hebben, verbazen zich erover dat iemand zichzelf ook maar een moment kan vergeten en een woedende opmerking of een vlug, angstig gebaar van protest kan maken.

Parallellen met het heden

Net zoals Svetlana Alexijevitsj, de winnares van de Nobelprijs voor de Literatuur in 2015, laat Krielaars ooggetuigen aan het woord om zijn verhaal over de Stalin-terreur te vertellen. Op die manier trekt hij ook opvallende parallellen met het hedendaagse Rusland.

Onder Stalin was het leven een grote illusie, maar ook Poetin is niet vies van censuur en fake news. De massale arrestaties behoren dan wel tot het verleden, maar ook vandaag wordt in het Kremlin gesidderd en gebogen voor de macht. Veel Russen lopen Poetin kritiekloos achterna omdat ze in hem de ‘efficiënte manager’ zien die Rusland moet redden van de anarchie. En net zoals Stalin na 1945 werpt Poetin zich op als de verdediger van het land tegen een buitenlandse vijand: Amerika.

De menselijke neiging tot medeplichtigheid

Krielaars beseft dat de vergelijking op verschillende vlakken spaak loopt, maar hij stelt vooral de ‘menselijke neiging tot medeplichtigheid aan de kaak. Ook hoogontwikkelde, beschaafde mensen kunnen zich laten leiden door lafheid en zwakheid. Ook vredelievende burgers kunnen hun vermogen tot zelfstandig denken verliezen en zijn in staat tot grote misdaden. Een eerste, schijnbaar onschuldige stap in dit proces is onverschilligheid. En dat brengt ons terug bij die parallel met het heden. In een gesprek met Grossmans jonge biograaf Joeri Bit-Joenan, noteert Krielaars deze ontmoedigende quote over Rusland anno 2017:

Tegenwoordig kun je twee dingen doen. Gek worden of je net als in de jaren dertig op je werk concentreren en je in je vrije tijd in het feestgedruis storten of in een nieuw restaurant gaan eten. Met politiek kun je je op dit moment beter niet bemoeien.

Alles voor het moederland is een gelaagd boek: biografie, literatuurstudie, geschiedenis, reisverhaal en filosofisch essay in één. Bij het taggen van deze blogpost leken alle categorieën van toepassing. Ik heb ervan genoten én ik heb ervan gegruweld. Ik heb ervan bijgeleerd én het heeft me achtergelaten met lastige vragen. Zo heb ik mijn non-fictie graag.

Blijf op de hoogte via Facebook en Twitter of abonneer je op de VDF-nieuwsbrief.

Gerelateerde boeken:

#gallery-0-4 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-4 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 33%; } #gallery-0-4 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-4 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

1924: het kanteljaar van Hitler – Peter Ross Range (2016)

Het Einde van Europa – James Kirchick (2017)

Harde Tijden – Rudi Vranckx (2017)

Alles voor het moederland: van blind idealisme naar beklemmende terreur Recensie van: Michel Krielaars: Alles voor het moederland, de Stalinterreur ten tijde van Isaak Babel en Vasili Grossman,

#Atlas Contact#Geschiedenis#Isaak Babel#Jaartal: 2017#Jozef Stalin#Michel Krielaars#Politiek#Rusland#Vasili Grossman

0 notes