#janaki

Text

If you think Sita was weak, remember that she single handedly lifted the Shiv-Dhanush as a child, was capable of burning people to ashes with a mere glance, could have freaking killed Ravan, was eligible to rule Ayodhya instead of Shree Ram as Guru Vashisht pointed out, was warned to Ravan as being Kalaratri, being capable of killing him, and did kill Raavan’s more powerful brother by invoking MahaKali.

She was every bit as strong as Śri Ram, something that was established in the Swayamvar itself. Just because she did not pick up a weapon, does not mean she was not capable of it either.

493 notes

·

View notes

Text

The feminine urge of holding hands with ur husband and spending 14 13 years of heaven in the forest away from the society <3

#desi love#lord rama#ram x sita#ramayana#valmiki ramayan#love#desi academia#sita#sita x ram#ravana#rama#ram mandir#ram leela#ram#indian aesthetic#desiblr#indian tumblr#india#desi indian#indian#desi#desi aesthetic#janaki#vaidehi

45 notes

·

View notes

Note

if i could request a prompt, a ramayana au! where rama goes to valmiki’s ashram to request sita to come back (as he does in some retellings) and gets a glimpse into how she’s lived all of these years, if the unit she and luv-lush have become and feels decidedly like an outsider. thank you!

Hello there! Thank you for the prompt. I haven't read any such retelling where Rama goes to request her to come back (unless you mean the one when Sita goes back into the earth, and I don't think you mean that?) so I hope this piece works for you:

It is Lakshmana who drives his chariot all the way to Valmiki’s aashram and offers him a hug of encouragement. A short, stocky woman in a saffron angavastra and a bun at the nape of her neck notices them first. Rama introduces himself and his brother, and watches with a wretched feeling in his gut as she gives them both a strained smile, introduces herself as Isha, and invites Rama in. To Lakshmana she says sternly, though not ungraciously, “Perhaps, it would be better if you wait outside.”

Rama opens his mouth to protest, daunted by the thought of facing this alone, and perhaps even a little peeved by the insinuation that his brother had done wrong by his wife; but Lakshmana touches his arm, bows, and answers, “As you wish, devi.”

Isha ushers him past residents going about their daily tasks and introduces him only to those curious enough to ask. She settles him under an old banyan tree, fetches him a glass of water with jaggery, tells him to wait, and then disappears.

Not long after, she returns and takes him past a different section, around the back and to a thatched hut in a corner. Rama immediately discerns this is where Sita must live. There is a little garden around the track leading to the door, and the flourishing greenery bears the marks of her care. In the verandah is a straw chair, amateurly made but well loved. Isha, who had gone in, now comes out with two little boys, one in each hand, and nods at him. “You can go in,” she tells him, “but do not wander around alone. This is the women’s section.”

It is only when she and her charges are out of sight that he realizes those two must have been his sons. He has heard, of course, of the twins – Lav and Kush, but for the first time he knows their faces. The thought of it nearly brings him to his knees and it is with some difficulty that he drags himself in.

Janaki, as he sees her now, is much changed. No longer is she the delightful princess he met so long ago. She is thin, her face gaunt from the labour of raising her children so far from the family that was supposed to aid her. And yet she still shines brighter than the Sun that fathered the Raghu clan, and if Rama ever harboured notions of getting over his love and loss, he now knows he was sorely mistaken.

“Sita,” he murmurs, and how broken a sound it is! What use is his kingship if he cannot have what he wants with all his heart? This is the woman he has waged a war for, the one who has borne his children, and the one who he has forsaken.

“Rama,” she murmurs back, and he can hear the suppressed tears trying to burst out. But this Sita is not the blushing girl he wedded in Mithila. This Sita has lived through the humiliation of an Agni-Pariksha, has endured the ignominy of being forsaken. Sorrow has brightened the fire in her eyes, misery has pressed her lips close together. She now stands straight and tall, assured in her ability to walk through horrors untold. This Sita will not be won over by lifting a bow.

“Please,” Rama says – and what a day, that Ayodhya’s king has come to beg – “please, come back. Come home with me.”

“And then?” she asks.

“I will fix everything,” Rama promises. There is a desperation in him that he can no longer suppress. He cannot hold her eye, and he cannot look away. All around him are traces of a hard life he has not lived – three straw mats propped on the wall, an earthen pitcher draped with a moist white cloth, utensils stacked neatly on a rack. “Come home, Sita,” he pleads, and weeps.

Sita’s hands are rough on his face, marred with callouses. She draws him close to her, and he leans onwards, shuddering like a man dying as her lips touch his forehead in benediction.

“I love you,” she tells him, and it is like pressing down on a much-loved bruise, painful and intoxicating all at once. “I have loved you all my life, and I will continue doing so forever. But I cannot go back.”

Rama’s voice is a whisper when he speaks, a prayer at the temple of her soul. “Why?”

Sita laughs. It is not the same resonant sound as before, bright as a bell. This laugh is a softer tinkle, tinged with the memory of what is, and what has been. “Do I not get an apology?” she teases.

Rama opens his mouth, a hundred protestations and regrets bubbling up even as shame colours his cheeks.

Sita shakes her head. “Where is your dharma, scion of Raghu? What will the people say?”

“The people miss you,” Rama says, and Sita scoffs.

“Bharat can be King,” Rama bursts out, unable to bear the harshness of that sound. “He has done this before. I will… we will go away together. Sitey, we will make something for ourselves, I…”

There is a scuffling sound, and Sita lets go of his face. Clutching his arm, she hauls him to his feet and steps outside. The loss of her touch stings, like someone has poured ice-cold water over him and he follows her blindly, seeking that relief again.

“Maa!” It is all the warning they have before the twins dash around the corner, all muddy clothes and twigs tangled in their hair. A calf prances in right after them, mooing out to the whole world.

Sita frowns like a switch has been flipped. She gives them both a severe look. “Where is Isha? And which of you freed him?”

“I don’t know. I saw him and he was getting bored,” Lav (or was it Kush?) pouts. “And we were bored too.”

Beside him, his twin draws a line in the mud with his toes, giggling. Sita stares at it for a long while.

“Maa! Bhaiyya poked me,” the first boy complains, and Rama feels a rush of relief knowing he had not guessed wrong.

“I didn’t,” Kush protests.

Sita places a hand on each of their shoulders, herds them to the calf. “Go, return him. It is bad manners to let loose animals in the aashram.”

Lav clutches the edge of her pallu, his little lips wobbling. “I wasn’t trying to be bad.”

“I know,” Sita sighs and presses a kiss to each of their foreheads. Rama’s heart aches. They cannot be older than six years, Taksh is, after all, just five. They are just babies, really.

Kush tugs his brother’s arm. “Come,” he says, side-eying Rama. Lav quietens down and follows him.

Sita watches him watch them go. “Do you think they would be better off in the Palace?” she asks eventually.

“Not if you aren’t there,” he replies. And it is true, he thinks bitterly.

Sita twists her fingers, pulls her pallu closer. “I will think on it,” she promises, and Rama holds those words close to his heart.

“I must go now,” he says, although he wants to do anything but. Sita does not seem particularly offended though. “I will see you off,” she offers, and he thinks it’s better she has the time to reflect on everything.

Outside, Lakshmana is sitting on a rock, talking softly with Lav and Kush. The calf is sprawled across the ground with its head on his knee, making soft, contented noises from all the petting. He stands when he notices them, and the boys let out identical shrieks of alarm.

“We’re going!” Kush yells, dragging the poor creature away.

Beside him, Sita rolls her eyes. “Go faster.”

They wait till the children are gone before approaching, and Lakshmana bows down to touch her feet.

Rama watches with a foreign pang in his chest as his brother apologizes profusely to his wife, and Sita, ever-loving, pats his shoulders and forgives him with a hug. Lakshmana volunteers information about her parents and sisters and she listens with the rapture of a chataka witnessing the year’s first rains, and Rama barely manages not to be jealous.

They leave much later with well-meaning goodbyes, and Lakshmana extracts a second invitation to the aashram. When Rama gets on to the chariot, all he knows is failure and loss.

But Lakshmana does not drive them home. He leads the horses half a mile into the jungle and swings around to look at him. “You are upset,” he says. It is not a question.

“I messed up,” Rama tells him bitterly. It is hard to conceal his resentment now that the whole world is against him. He had sent away his wife to please his people, against the wishes of all his family. And now the same citizens of Ayodhya denounce and scorn him, and his brothers look to him warily, as if to guard his sisters-in-law from a similar fate. Dasaratha had chosen his wife over his people and paid for it, and now Rama pays for the contrary. What is, then, the right answer?

“Did you apologize or explain?” Lakshmana asks.

Rama bites his lip, barely refrains from losing his temper. How is this my fault? he wants to ask. Have I not suffered as well?

Lakshmana touches his arm, gives him a compassionate look. “When we had the boys,” he begins, and Rama has to smile at the thought of them, “we – Urmila and I – fought a lot. One of those times, it was my fault. I will not tell you want happened, and I hope you will not ask, because you will be very angry, but suffice to say it was bad.”

Rama sits down, blinks at him, interested now. “And then?”

Lakshmana gives him a sheepish smile. “I was too bull-headed to accept that it was my fault. But Urmila came up and said that she was sorry for acting the way she did, and that she could see my point. I was, as you can understand, mortified.”

“Huh,” Rama says, surprised. This is not how fights between Sita’s sister and Sumitra’s oldest usually end.

“Anyway, I told her that no, it was my fault, and she should not have to step back when she had been correct. And then, bhaiyya, Urmila told me something really important. She said when we fight someone we love, we should step back for a moment, and apologize even if we weren’t wrong, so we could initiate a conversation about what happened and how to prevent it.”

“…oh,” Rama says, for lack of a better response. “That is… very mature.”

His brother nods sagely. “There is never a dull moment with Janak’s daughter. But you see what I’m trying to say?”

“Yes,” Rama breathes, pieces falling into place. “Let’s go back, I will tell her! Lakshmana!”

But Lakshmana merely settles back in, shakes his head. “Not today,” he advises. “Let her have some time to see what she wants. Too long we have tried to mold her into what she should have been, instead of appreciating what she was. We will come back another day.”

Rama doesn’t want to go, not to that empty Palace in Ayodhya that is no longer home. But he takes his brother’s words to heart and listens. After all, if he cannot trust Lakshmana, he can trust no one.

#lakshmana is a marriage counsellor of sorts#i'm not sorry#ramayan#rama#ram#ramayana#sita#janaki#lakshmana#urmila#valmiki's aashram#ask#anonymous#askbox#ask box#ask response#anon answered#answered#fic#boo writes

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don't know how to explain jaanu but whenever I visited a temple all I prayed was "God, keep jaanu with me all the time".

Ramachandra, 99

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The main entrance of the Janaki Temple in Janakpur, Nepal

0 notes

Photo

The main entrance of the Janaki Temple in Janakpur, Nepal

0 notes

Text

The main entrance of the Janaki Temple in Janakpur, Nepal

0 notes

Photo

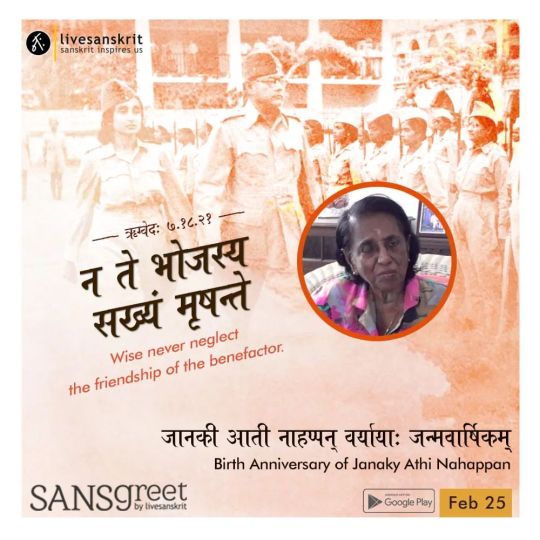

Send from Sansgreet Android App. Sanskrit greetings app from team @livesanskrit . It's the first Android app for sending @sanskrit greetings. Download app from https://livesanskrit.com/sansgreet Janaky Athi Nahappan. Puan Sri Datin Janaky Devar (25 February 1925 – 9 May 2014), better known as Janaky Athi Nahappan, was a founding member of the Malaysian Indian Congress and one of the earliest women involved in the fight for Malaysian (then Malaya) independence. #sansgreet #sanskritgreetings #greetingsinsanskrit #sanskritquotes #sanskritthoughts #emergingsanskrit #sanskrittrends #trendsinsanskrit #livesanskrit #sanskritlanguage #sanskritlove #sanskritdailyquotes #sanskritdailythoughts #sanskrit #resanskrit #janaky #janaki #nahappan #janakyathinahappan #janakydevar #kualalumpur #malaysia #malaysianindian #malaysianindiancongress #malaya #malaysianindependanceday #celebratingsanskrit #tamil #ina #japanese https://www.instagram.com/p/CpFutkmPmFa/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#sansgreet#sanskritgreetings#greetingsinsanskrit#sanskritquotes#sanskritthoughts#emergingsanskrit#sanskrittrends#trendsinsanskrit#livesanskrit#sanskritlanguage#sanskritlove#sanskritdailyquotes#sanskritdailythoughts#sanskrit#resanskrit#janaky#janaki#nahappan#janakyathinahappan#janakydevar#kualalumpur#malaysia#malaysianindian#malaysianindiancongress#malaya#malaysianindependanceday#celebratingsanskrit#tamil#ina#japanese

0 notes

Text

Can you imagine opening Tumblr and perhaps, you like theology, let's say you know about hindu and greek gods. Now you open Tumblr and because you're bored and curious and on Tumblr you start searching posts tagged with certain gods' names, but for some fucking reason you keep getting miscellaneous posts about... Cats maybe??? Because some idiot decided to name their cats after gods they know very little about. Imagine you find my blog like that

... Would you follow me?

#Vishnu#Janaki#Tique#Also I've had cats named Dharana. Prema. Ganesha. And a hamster named Swami (that's just male for teacher or smth like that)

0 notes

Photo

AMAZING ❤️❤️❤️❤️CONNECTIONS between temples. All Mahadev Temples in the same longitude!!!!! .. 🙏🕉🙏🕉🙏 1. Kedarnath 2. Kalahashti 3. Ekambaranatha- Kanchi 4. Thiruvanamalai 5. Thiruvanaikaval 6. Chidambaram Nataraja 7. Rameshwaram 8. Kaleshwaram N-India 🙏🕉🙏🕉🙏 Can you guess what is common between all these prominent temples? 🙏🕉🙏🕉🙏 The longitude in which these SIVA temples are located is AMAZING. 🙏🕉🙏🕉🙏 They all are located in 79° longitudes. 🙏🕉🙏🕉🙏 What is surprising and awesome is that how the architects of these temples many hundreds of kilometres apart came up with these precise locations without GPS or any such gizmo like that. 🙏🕉🙏🕉🙏 1. Kedarnath 79.0669° 2. Kalahashti 79.7037° 3. Ekambaranatha- Kanchi 79.7036° 4. Thiruvanamalai 79.0747° 5. Thiruvanaikaval 78.7108 6. Chidambaram Nataraja 79.6954° 7. Rameshwaram 79.3129° 8. Kaleshwaram N-India 79.9067° 🙏🕉🙏🕉🙏 See the picture -- all are in a straight line. 🙏🕉🙏🕉🙏 #india #hinduism #hindu #Aum #om #chinmayanission #bharatanatyan #mohiniyattam #priya #janaki #radha #lordkrishna #bharat #lordsiva #adiyogi om Namah Shivaya 🙏🏽🕉💙 (at Howard Beach) https://www.instagram.com/p/CgDQgyqL09Gw4Ugq0Nb1039R4THFmEH59qRrLM0/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#india#hinduism#hindu#aum#om#chinmayanission#bharatanatyan#mohiniyattam#priya#janaki#radha#lordkrishna#bharat#lordsiva#adiyogi

0 notes

Text

கண்மணி அன்போடு

காதலன் நான் எழுதும் கடிதமே

பொன்மணி உன் வீட்டில்

சௌக்கியமா நான் இங்கு

சௌக்கியமே

"Kanmani Anbodu Kaadhalan

Naan ezhuthum kadithamae

Ponmani un veetil sowkiyama

Naan ingu sowkiyamae"

Dear, this is the letter I write with love

Golden dear, is everyone fine at home, I'm fine here

- Guna (1991) Illayaraja

Kamal Hassan, S. Janaki

#tamil songs#guna#kanmani#this song popped up in my head and i had to type this lol#this song is so fricking good#im adding the song in case you wanna listen#kanmani anbodu#kamal hassan#sapphorarelyreads#tamil#desi tag#tamil tag#janaki

0 notes

Note

May I request another prompt, this time Ramayana??

Where after Sita's bhumi pravesh, Luv -Kush live at Ayodhya's palace. They are merely 8, feel scared at this new place and battle resentments against their father for abandoning their mother. Who love their mother but are angry at her for forsaking them. Grappling with loss of their familiar forest and pleasures of simple lives, find the city walls strangling them.

Hi there, and sorry, this is a little late. This is also a little depressing, and I do not apologise for it.

Prev ask: Karna and Arjuna character swap is here

1.

This day Luv is eight years old, and the world is gray.

“You may play here if you wish to, you will be safe,” the King, their father, says, gesturing at the gardens. The trees are trimmed and gray, the walls are high and soot.

Their father leads them to the throne room; he doesn’t know it is their birthday.

“This is where we talk about... er, important affairs,” Rama explains, stilted and awkward.

High on the dias, a sculpture sits hard and cold upon the Queen's seat. It looks to him an ashen thing, but Luv has learnt it is a golden memorial to Sita's enduring place at Rama's side.

There is gold of the coin, and the gold of the wheat, and then there is the gold of Sita's smile. He thinks of his mother at the aashram, bent over the flour mill with calloused hands and crinkled eyes, and pities the statue that seeks to compare.

“Your eyes deceive you, Your Majesty,” he tells Rama. “That is not my mother.”

The King looks stricken, and Luv turns away. Perhaps this is what the King needs, a statue that is silent and chaste and dear.

“I know,” Rama whispers, kneeling by his side. There are tears in his royal eyes, and Luv has never loathed anyone more.

2.

Angada's mother is tall and beautiful, and the quietest of all his aunts. She sits on the steps to her husband’s room, and beckons them closer.

“Greetings,” Kush bows, and Luv follows.

“Sit by me, my dears,” she says. Her hair is coiffed up in a high bun, and Luv imagines the pins in them gleaming with gems.

Urmila notices him watching, and plucks one from her head. It is gray in her palm as she holds it out to him, like all other things, and he takes it in silence.

“May I help you?” Kush asks, ever polite and well-mannered, and she laughs.

“I am not doing anything,” she says. “Do you want-”

The door opens, and Lakshmana appears at the end of the hallway. He rubs a hand over his haggard face, spots them, and staggers.

Kush jumps up, bows. “Greetings, uncle.”

Luv remains seated, staring at the soft gray carpet and the forbidding gray walls, and thinks of Lakshmana swooning at his arrow's end.

“Forgive me,” he says abruptly, “I have to go.”

He holds out the pin, a flower atop a long straight needle, and bows. Kush touches his arm in concern.

“Keep it,” aunt Urmila says. “It was your mother’s.”

Luv looks down at the little trinket in his palm, turns it over. Kush peers over his shoulder with hungering eyes.

“It is red,” his aunt says, as if she knows about the gray, “and there is a ruby at its heart.”

Luv clutches it to his breast, watches the colour spill across it like the red sun bleeding on a newborn dawn. The world is gray and he is a colourless blot, and Sita sits at the centre of it, burning in the fire's test, bright red and lost.

3.

In his dreams, Luv is a weevil in the flour. Someone is shifting through it, running vivid gold fingers through the dusted grains. He bites at the right and bites at the left, lets the starchy sweetness flood his tongue.

Then there are great gold walls closing upon him, and it is his mother who hauls him out, who throws him to the grass to starve and die.

“Maa!” he calls, clinging to her hands, but he is weak, and he is lost, and he falls, and then he wakes up.

The walls are gray, but no less imposing, and he clutches at Kush's arm. His brother is draped in a blanket as black as a washerman's heart, and Luv crumples the fabric in his fist.

Kush sits up beside him, an ashen smear against an ashen world. “Did you have a bad dream?”

Luv twists the dark cloth between his fingers, contemplates on how to answer. Their uncles claim Kush takes after Sita; Luv knows he needs a little brother to lean on, just like Rama.

“You had a bad dream too, didn’t you?” he asks.

“Mhmm,” Kush hums, and Luv takes his hand.

“You first, then me,” he says.

Kush taps his lips and stares at the dark ceiling. “In my dream...” he recounts thoughtfully, “I was a weevil in the flour.”

Luv tugs on the blanket, wraps himself in their shared sorrow. The world is gray, his mother’s love is a flame, and his brother’s blanket is night.

4.

At the furthermost wing of Ayodha’s palace sits a sunroom of dramatic proportions. The windows here are wide and open, facing the east, so mornings are warm and evenings cool, and Luv could stay here forever.

Uncle Bharata, who leads him with a hand on his back, settles on one of the footstools before a large canvas. Luv watches as aunt Shrutakeerti follows, and their spouses settle on the big couch to the side, pretending to be annoyed at having their portraits done.

“I feel like I should have Luv with me,” aunt Mandvi says, swinging her legs. “And Shatru can have Kush. The heights match that way.”

Luv does not want a portrait done, not when he would never know the colours again. Uncle Bharata beckons him to get another stool and says, “Next time perhaps, darling. Let him observe first.”

Luv plops on the stool with a thump, and studies his uncles and aunts. Shrutakeerti is sketching rough outlines, unlike Bharata, who meticulously draws one eye, then the other.

“Do you want to try?” she murmurs quietly. “You can say ‘no’.”

Luv twists his fingers, feeling warm and shy. He can say no, even though he has no mother and knows none of his family.

“I can try,” he mutters.

Shrutakeerti gives him a conspiratorial smile. “Let’s use brown for the walls,” she says conversationally, as if she knows the grays.

Luv takes the brush and swipes at the corner. It is the colour of earth and mud, of dates and cows and a potter’s clay. The world is gray, but his mother’s love is red and his sorrow is black, and his family is reliable and brown.

5.

Rama wears a yellow dhoti – Luv knows this because the washermen mutter about it all the time. He keeps a close eye on them – they hate how easily the cloth stains, and they hate his mother.

Kush’s condemnation of this practice falls on unheeding ears. His brother is too sweet and too trusting, and Luv must protect what their mother could not.

Brinda, who is some washerman’s wife, brings them lunch at the river everyday. She bows when she sees him, all flustered with shame, and walks faster.

That day he returns from the river with quick steps, excited to see the browns on the barks and the black of Kush’s hair. He has found a pebble on the banks, a pale, smooth rock, and uncle Bharata, he knows, will tell him the colour.

Outside, the gardener burns a heap of fallen leaves, dried by the passing of the rains, and dead with the sorrow of oncoming winter. Some of them are red like his mother’s flower, stark amid the grays. They crumple in the flames and burn, and for a moment he sees Sita engulfed in heat, smiling.

“Maa!” he screams, throws himself at the soaring column of fire.

“Put that out! Now!” someone says, hard and commanding. A hand snatches his shoulder, draws him close and away. He can see no higher than their waist, but their dhoti is the yellow of sunshine and an oriole’s breast, a hundredfold more vibrant than the paltry fires.

Luv lifts his head and finds himself swung up in the air, to where his father’s cheek presses against his. Rama’s face is the brown and black of alluvial earth, and he smells of lotuses and rain.

“It will be okay, little one,” he murmurs, voice quivering. “I am here.”

The world is gray, but it recedes bit by bit, like hope rising from sleep; it is red with his mother’s love and black with his grief, brown with his family’s presence, and bright with his father’s refuge.

+1

His cousins play in the royal gardens all day, unbothered by walls that choke him, unafraid of a parent dying. Luv sits in the shade with his bright red flower and dark black blanket, stroking a brown bark. The world is gray, and Luv’s dhoti is hay, and does not care.

Uncle Lakshmana comes to sit beside him with a huff, ruffles his hair distractedly.

“Will you not join them?” he asks, blunt as ever, and Luv sighs.

“Everything is gray,” he says, as if that makes any sense, but uncle Lakshmana shakes his head as if he understands.

“That is not,” his uncle says, pointing at a lonely little sapling poking out of the earth.

The ash leaches from it like rain clouds fleeing from sequestered plains, and it is the green that defies the winter’s chill.

“It is a weed,” he says weakly. "I have seen the forest."

Uncle Lakshmana scoffs. “Weeds, weeds, weeds,” he grumbles. “All arrogant words made by men who think to tame who grows where. There are no weeds, dear one, and no season either. You grow where and when you will, like all things in this world.”

It is too great a thing to hope for, but the gray is fading like dust blown off an old painting, and it is true. There is green on the leaf and green on the grass, green on the bower and green on the bough. The barks are brown and the flowers are red, and the sun of the Raghu clan shines bright yellow.

“Will you wait till the gray goes away?” he asks Lakshmana.

His sorrow is black, and Sita is gold; when he looks up, his uncle kisses his forehead with a smile. “Always,” he says. “Always.”

#hc: when it comes to kush#luv is basically lakshman 2.0#hindu mythology#ramayan#rama#ram#ramayana#sita#janaki#lakshmana#urmila#ask#anonymous#askbox#ask box#ask response#anon answered#answered#fic#boo writes#5 + 1 fic#luv#kush#bharata#shrutakeerti#laxman

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

the casting of adipurush sucks. i said it.

#arunima blabbers#No I don't see Prabhas as Lord Ram#I don't see anyone as Lord Ram actually#Kill me for this but idc Prabhas cannot act#He's a flat actor no expressions there I said it idc cancel me#Kriti may be nice or whatever but she's no Janaki to me#I'm actually angry about this prabhas should not be playing Lord Ram#Prabhas fans don't kill me but he's overhyped#The trailer looks so bad imma go cringe#The cgi and the vfx look so bad plus the acting ew God wtf is happening#Ps. To the people defending Prabhas by saying Lord ram actually looked like him Y'ALL CAN GO TO HELL BECAUSE HE'S A BLAND ACTOR TCH TCH

82 notes

·

View notes