#icelandic folklore

Note

Hello, uh, 'Auntie grey' as your adoring fans call you, have you ever made an animation? Or tried to?

Hello, yes Auntie Grey that’s me!😜

I Have done animations yes! Mostly animatics too.

I never in my life want to be an animator, but I like having that skill just to entertain myself.

Here’s a little Icelandic horror animation I did once! I’m very proud of it but don’t get a lot of opportunity’s to show it off.😜

240 notes

·

View notes

Text

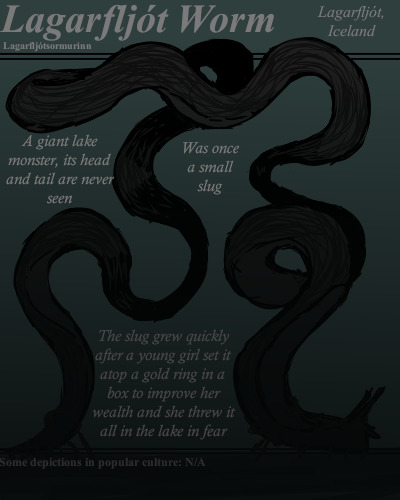

After it was thrown in the lake, the slug grew to such size that it began to occasionally come ashore and terrorize the countryside with its appetite and its poisonous spit.

Eventually the worm was subdued, but the gold ring could neither be retrieved from under it, nor could they manage to kill the creature. Instead they chose to tie its head and its tail to the bottom of the lake. Its continued growth since then means that its body occasionally reaches the surface, or even arches above it. The sightings of this phenomenon are considered ill omens.

#BriefBestiary#bestiary#digital art#fantasy#folklore#legend#lake monster#lagarfljót worm#lagarfljótsormurinn#icelandic folklore#icelandic legend#monster#serpent#worm#wurm

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

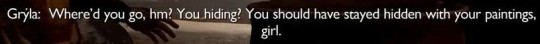

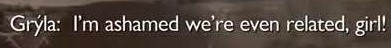

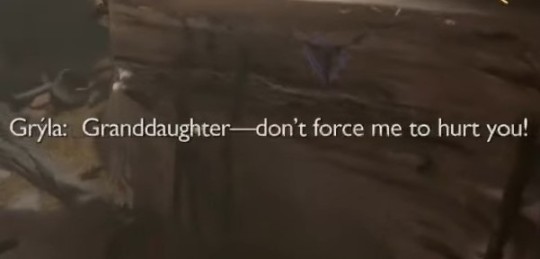

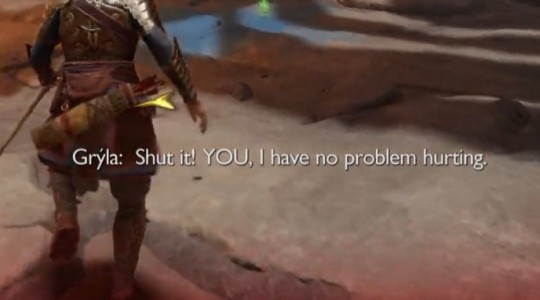

EDIT UPDATE 9/4/2023: A little reminder that Grýla had never once addressed her own granddaughter's name and instead used "girl" to not only degrade Angrboða but as an attempt to detach herself from her sole family member while keeping her granddaughter at a distance, this familiar dynamic between Grýla and Angrboða closely resembles the relationship between Kratos and Atreus back in 2018.

(Credits to @/averagehellraiser for the screenshots!)

While Grýla had cared for Angrboða from afar, Kratos does the same for Atreus before and throughout the occurrences in God of War (2018). The only difference lies in the death of Angrboða's parents, especially Grýla's son, causing the rift between them at a time when they could have found solace together and healed through their shared grief. By contrast, Faye's death strengthens the bond between Kratos and Atreus, allowing them the opportunity to reconcile their strained relationship.

#Kratioed Speaks#Norse Mythology#Angrboða#Icelandic Folklore#Grýla#God of War#God of War: Ragnarök#God of War: Ragnarok#Angrboda#Gryla#gow#gow ragnarök#gow ragnarok#gow Angrboda#gow Gryla#gowr

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

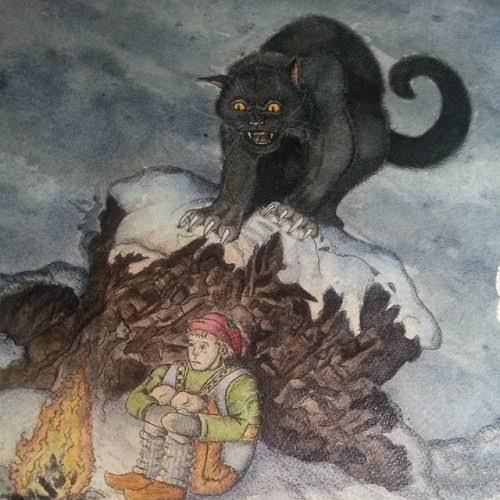

Yuletide Greetings from the icelandic Yule Cat! 🎄🌟

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

As we have established, I have Can't Shut Up Disease about the Bjarna-Dísa folktale and so I've spent most of this evening making a rough translation, the better to not shut up about it. My Icelandic is a little rusty at this point, so if you spot any parts I've obviously misunderstood, do let me know.

You can read the Icelandic online here, which I'm fairly sure is just a transcription of the text from Jón Árnason's Íslenzkar Þjóðsögur.

You can listen to Snorri Helgason's haunting (haha) song version here on his Bandcamp. The entire Margt býr í þokunni album is a collection of songs inspired by Icelandic folklore, would very much recommend.

Finally, you can find my translation of Bjarna-Dísa below the cut. I'm not sure how best to content warn for it other than to say that it's an Icelandic ghost story where the weather may actually be scarier than the ghost.

EDIT: apparently I'm doing more of these:

The Deacon of Myrká

Bjarna-Dísa

There was a man called Bjarni, the son of Þorsteinn. He was born in the late 18th century and lived until 1840. He had a sister called Þordís. She was about twenty when this story took place.

Þordís was pleasing in appearance, but was considered rather arrogant in attitude. She made a great deal of her clothing and imitated as best she could the fashions of Danish ladies, and she stayed at Eskifjörður marketplace in the last year of her life.

It so happened that Bjarni Þorsteinsson travelled down into Eskifjörður, and Þordís then joined her brother on his journey and planned to go with him to Seyðisfjörður, where Bjarni then lived.

Nothing is told of their journey before they took up lodgings at Þrándarstaðir in Eiðaþinghá. That was in the first half of Þorri [late winter]. They were there for one night. But the next morning, when they wanted to go pass over Fjarðarheiði, the weather was thick with snow and frost. Bjarni told his sister that she should stay behind, because the weather was unreliable and she was dressed for looks and not for protection.

She was in a simple linen dress and linen undershirt, sleeveless from the elbows down. She called it a serk and wanted no other kind of shirt. She had a cloth headdress, red and brown, and her hands and feet were poorly clad.

Dísa was not pleased to sit waiting. She declared that she should go with him, whether he would or no. They fell into an argument, and so set off both in poor humour, and made their way up onto the heath, in spite of the fact that the weather was growing worse and worse.

Now it came to pass that Bjarni had no idea where he was going, and Dísa grew weary from both cold and exertion, and always she complained that she was exhausted from all this walking; then Bjarni began to dig a cave into a snowdrift and when he had finished, it seemed to him that there was a gap in a gravel bank a little way away; then he said to Dísa that he wanted to go over there and see if he recognised the gravel bank. She asked him not to leave her, but it was no use.

So Bjarni went, but then the weather closed in; he thus found neither the gravel bank, nor Dísa again; nonetheless, he carried on indecisively until he crawled, barely awake, into Fjörður in Seyðisfjörður that evening, almost completely without strength, speechless and very scraped up around his face. He had gone astray past the mountain and fallen into brambles and ravines, lost his hat and was generally in a bad way.

At that time, there lived in Fjörður a farmer who was called Þorvaldur Ögmundsson. He was well thought of, powerfully strong and very brave. Those who knew him said that he knew no fear. He was straightforward and even-tempered, intelligent and the best man to ask for a favour.

He received Bjarni well and had him nursed back to health as best he could. And it was not until the next evening that Bjarni was able to tell the tale of his journey, so exhausted was he. Then he begged Þorvaldur to prepare himself to search for his sister; but the weather continued the same as ever. It was weather from the north, very harsh and dark, and so much frost that it was hardly possible for a strong man to find his way home between the houses. So Bjarni was there for two more nights, but on the fifth day after he parted from Dísa, the weather calmed a little.

Then they prepared themselves for the journey, Þorvaldur, Bjarni and a labourer by the name of Jón Bjarnason, a hard-working man and a good fellow; they made their way up to the heath, but a little way from the common route, because it was Bjarni’s guess that that would be the best place to search for Dísa.

When they had come north of Stafdalsfell, they heard a scream so loud that it resounded through all the nearby mountains. Jón and Bjarni were shocked but not terrified, and Þorvaldur did not know what it was to be afraid. He headed in the direction from which the sound had come, until he was east of Stafdalur. His companions had begun to fall behind. Then Þorvaldur questioned Jón’s courage to get him to keep up.

By then, the day had ended, and the weather was somewhat bright, and bitter frost came driving at them; the moon shone down and clouds passed overhead; thus the time passed. Then Þorvaldur saw something in a snowdrift, where he had had no hope of finding anything, though the area was well-known to him. There was a grassy hill stretching away from them.

Then he said to the others, “Þordís must be there now,” and it was as he said.

So he went to her. She was not at that time lying down, as he would have expected from a dead person, but rather she was positioned most like when people are sitting in a chair; the linen dress was tented around her middle and frozen in spikes, and she was bare below and bareheaded, the snow-house blown away so that you could only see the bottom of it.

Þorvaldur spoke then to his companions, saying that they should approach and help each other to arrange the corpse on a skin which he had brought with them for transportation. They dragged it towards him. Then he told Bjarni to cut the frozen covering off her, because he wanted to dress her in trousers, which he had with him, so she was not naked as they carried her. Bjarni did as he was told, though he was afraid.

Then Þorvaldur lifted her up in his arms and intended to dress her in the trousers, but at this, she let out such a great howl that it overpowered him; Þorvaldur has said that it seemed to him impossibly strong and mighty.

His companions recoiled from deadly fear, but Þorvaldur reacted thus: he put Dísa down hard and said rather quickly: “No good are you, Dísa, to struggle like this, because I am not at all afraid, and if you carry on like this, then you will find out that I shall tear your apart nerve by nerve and then throw your body to the wolves; on the other hand, if you behave agreeably for us while we carry you and we have no trouble getting you down, then I shall make a coffin for you and bury you in a Christian grave, though I imagine you aren’t worthy of such a thing.”

After that, he took her, dressed her and arranged her on the skin, called his companions to him and made his way home.

(Other stories say that Þorvaldur may have broken Dísa’s back to make her be quiet, and thus she stopped howling. There are many other ugly stories about their exchange. Þorvaldur was a decent, honest man, but superstitious like many in the 18th century, and the story he told himself must be the most accurate.

(The stories say that Dísa and Bjarni had had a cask of strong spirits. Dísa may have been drunk, but alive, and Þorvaldur dealt with her out of superstitious fury.))

Þorvaldur had seen that the tracks from Dísa’s lair were like this: that she had walked, so that each path was different, to about four fathoms away and then leapt backwards in a single leap with both feet, back into her den, and she had done this twice. Hermann of Fjörður in Mjóafjörður, who was called very wise, has said that this was the habit of those who walked after death, and they needed to do it three times in order to become full revenants, but Dísa lacked the third path.

Now they carried on down from the heath; the weather was so dark overhead that it was hard to find their way, yet they arrived unharmed at Fjarðarsel; it was then a short way out to Fjörður over the shoulder of the mountain, but Þorvaldur did not trust himself to find his way along the fjord; he asked for lodgings for him and his companions. But the farmer refused; he said that he had become wary of the unpleasant spirit that followed them.

Then Þorvaldur began to make arrangements: he set the body in a shed across from the doors to the living quarters and went into the living quarters with his companions, and the farmer sat with his son on the edge of the sleeping platform. Both of these two were called Björn; they each held a spiked walking stick in their hands and paced back and forth in front of the door. Thus they continued into the night. Þorvaldur did not become sleepy, and did not undress, but went out alone to look at the weather. One time during the night, when he wanted to turn back to the main building, Dísa appeared before him in the doorway, as though she wanted to follow him inside, but he turned her away and hurried into the living quarters.

With the coming of day, the weather quietened, so that they were able to reach Fjörður. The hut in which Dísa had spent the night was scratched as though by claws. Now Þorvaldur went to a coffin-maker, just as he had promised, and had Dísa brought to Dvergasteinn. The priest there at that time was Þorsteinn Jónsson the poet (d. 1800). He offered Dísa burial in the Christian manner. But it so happened that the next morning there was a strangely deep hole at the foot of Dísa’s resting place; the hole was filled, but in the morning it was open again. Again it was filled, and yet again, on the third morning, it was open as before. Then the priest himself came and said a blessing over the hole. Men say that from that point on, it did not re-open.

Now it must be told about Bjarni, that henceforth, whenever he intended to sleep, Dísa came and tried to take him by the throat, and this was no secret because both the blind and the sighted saw her. Men also said that she had often attacked him, even in the light. Then he went to Father Þorsteinn, who was mentioned before, and received some kind of protection from him, so that Dísa never succeeded in hurting Bjarni himself.

Bjarni had thirteen children, and they all died young and quickly. Men have it as true that Dísa must have hastened all of their deaths. She followed Bjarni until his dying day and often made her presence felt: killed living people, and sometimes attacked men, and there are many tales told of her tricks that would be too long to relate here.

And thus ends the story of Bjarna-Dísa, and the story here is written as it was told by Þorvaldur himself.

#I would love for people to read this because I think it's a very cool and creepy little story#with lots of room to imagine all sorts of horrible things if you want to#unfortunately I have no idea what to tag it as so *shrug* here goes#folklore#icelandic folklore#translations#ghost stories#(on which note I should really see if we have anything else attributed to Mr Cleverclogs Hermann of Fjörður because his stuff about#How to Make a Revenant is very interesting and I wonder how well-known it was)

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

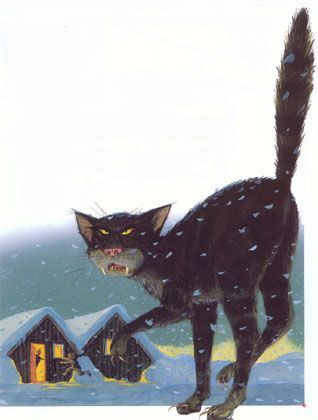

Happy Yule, everyone! I hope the Yule Cat doesn't get you!

Find this new pattern in my shops, my Patrons on Patreon get it free!!

#cross stitch#xstitch#crossstitch#cross stitch pattern#broderie#fiber arts#stitchcraft#patreon creator#pixel art#yuletide#yule cat#icelandic folklore

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

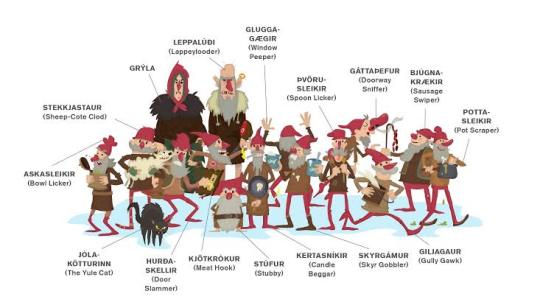

The Creatures of Yuletide: The Giant Grýla and her dysfunctional Yule Family

Some days ago, I talked with @ariel-seagull-wings about how Ded Moroz, Grandfather Frost, and his granddaughter Snegurochka, the Snow Maiden, were probably the only holiday figures that were related. I WAS WRONG.

Iceland produced a family so colorful and dysfunctional that it’s a crime there are still no sitcoms based around them. Some members of this family are already famous, others not so much and will have a spotlight today. @thealmightyemprex, my dear, I think you are going to like this family.

Today, we are talking about the giants Grýla and Leppalúði, their yule children, and their giant pet.

Grýla is a giantess said to live in a cave in Dimmuborgir, an area of various volcanic caves and rock formations located in the Myvatn area of north Iceland. Others believe she and her family simply live in an unidentified mountainous area.

Always hungry, she senses the smell of naughty children all year, and during Christmastime, she leaves her cave and comes to cities and towns to haunt them. She collects children in an enormous sack, then brings them back to her cave. There she will cook them in a pot and turn them into a giant stew that will sustain her until the next winter.

Surprisingly, Grýla has been married THREE times, having KILLED her first and second husbands, and EATEN the first. Her third and current husband is the giant Leppalúði. Grýla is often shown beating and berating her husband that is described as being lazy, staying behind in their cave, while Grýla searches for food.

The relationship between Gryla and Leppaludi echoes many villainous couples in sagas and legends from Iceland that were composed of a cruel and bloodthirsty woman with a pathetic, spineless husband.

The threat of Grýla was a means to scare children and put them in line, since winters in Iceland were incredibly dangerous, and there was a lot of work that needed to get done before the darkest months set in, requiring effort from all members of the family. It was also a way of protecting children from wandering alone at night, as many disobedient children who went out in the dark and snow never returned home.

Grýla is originally mentioned in the 13th-century compilation of Norse mythology, Prose Edda but no specific connection to Christmas is mentioned until the 17th century.

In the thirteenth century, she was described as having fifteen tails. In the seventh century, she had a hundred bags tied to each tail, with each bag containing twenty naughty children for her pot.

The Yule Lads, are the mischievous offspring between Grýla and Leppalúði. They arrive one by one over the final nights leading up to Christmas, pulling pranks on the humans they find. Originally they were described as being far meaner and more evil, being as monstrous and deformed as their parents, representing the dangers and nuisances of Winter. But by the 18th century, a royal decree about religious practice and domestic discipline banned parents from disciplining their children by scaring them with horror stories of monsters, like Grýla and her family.

By the end of the 19th Century, wealthy merchants began hosting public Christmas tree balls, turning the Yule Lads into friendly old men who brought treats. These versions of the characters first appeared in towns and villages, while their original counterparts survived longer in the countryside. But by the 1930s their transformation had been completed as they begin making regular visits to schools and making appearances on the radio to tell children stories and sing Christmas songs. Today they are gift-bringers like Santa, leaving small gifts in shoes that children place on window sills, but if the child has been disobedient, they leave a rotten potato in the shoe instead.

Originally the personalities and number of Yule Lads varied greatly, but thanks to a poem from 1932 by Jóhannes úr Kötlum in the children’s book Christmas is Coming (Jólin koma), still very popular and recited in many Icelandic homes and schools in December, established what is now considered the canonical 13 Yule Lads and their names and personalities.

Here’s the poem, translated by Hallberg Hallmundsson:

Let me tell the story of the lads of few charms, who once upon a time used to visit our farms.

Thirteen altogether, these gents in their prime didn´t want to irk people all at one time.

They came from the mountains, as many of you know, in a long single file to the farmsteads below.

Creeping up, all stealth, they unlocked the door. The kitchen and the pantry they came looking for.

Grýla was their mother – she gave them ogre milk – and the father Leppalúdi; a loathsome ilk.

They hid where they could, with a cunning look or sneer, ready with their pranks when people weren´t near.

They were called the Yuletide lads – at Yuletide they were due – and always came one by one, not ever two by two.

And even when they were seen, they weren´t loath to roam and play their tricks – disturbing the peace of the home.

The first of them was Sheep-Cote Clod. He came stiff as wood, to pray upon the farmer´s sheep as far as he could. He wished to suck the ewes, but it was no accident he couldn´t; he had stiff knees – not to convenient.

The second was Gully Gawk, gray his head and mien. He snuck into the cow barn from his craggy ravine. Hiding in the stalls, he would steal the milk, while the milkmaid gave the cowherd a meaningful smile.

Stubby was the third called, a stunted little man, who watched for every chance to whisk off a pan. And scurrying away with it, he scraped off the bits that stuck to the bottom and brims – his favorites.

The fourth was Spoon Licker; like spindle he was thin. He felt himself in clover when the cook wasn´t in. Then stepping up, he grappled the stirring spoon with glee, holding it with both hands for it was slippery.

Pot Scraper, the fifth one, was a funny sort of chap. When kids were given scrapings, he´d come to the door and tap. And they would rush to see if there really was a guest. Then he hurried to the pot and had a scrapingfest.

Bowl Licker, the sixth one, was shockingly ill bred. From underneath the bedsteads he stuck his ugly head. And when the bowls were left to be licked by dog or cat, he snatched them for himself – he was sure good at that!

The seventh was Door Slammer, a sorry, vulgar chap: When people in the twilight would take a little nap, he was happy as a lark with the havoc he could wreak, slamming doors and hearing the hinges on them sqeak

Skyr Gobbler, the eighth, was an awful stupid bloke. He lambasted the skyr tub till the lid on it broke. Then he stood there gobbling – his greed was well known – until, about to burst, he would bleat, howl and groan.

The ninth was Sausage Swiper, a shifty pilferer. He climbed up to the rafters and raided food from there. Sitting on a crossbeam in soot and in smoke, he fed himself on sausage fit for gentlefolk.

The tenth was Window Peeper, a weird little twit, who stepped up to the window and stole a peek through it. And whatever was inside to which his eye was drawn, he most likely attempted to take later on.

Eleventh was Door Sniffer, a doltish lad and gross. He never got a cold, yet had a huge, sensitive nose. He caught the scent of lace bread while leagues away still and ran toward it weightless as wind over dale and hill

Meat Hook, the twelfth one, his talent would display as soon as he arrived on Saint Thorlak´s Day. He snagged himself a morsel of meet of any sort, although his hook at times was a tiny bit short.

The thirteenth was Candle Beggar – ´twas cold, I believe, if he was not the last of the lot on Christmas Eve. He trailed after the little ones who, like happy sprites, ran about the farm with their fine tallow lights.

On Christmas night itself – so a wise man writes – the lads were all restraint and just stared at the lights.

Then one by one they trotted off into the frost and snow. On Twelfth Night the last of the lads used to go. Their footprints in the highlands are effaced now for long, the memories have all turned to image and song

Okay, we have the abusive mother, we have the lazy father, we have the troublemaking sons, but we still haven’t talked about the pet. You know what I’m talking about. I think he’s probably the most famous one in this post, at least outside Iceland. Yes, the Yule Cat is their family cat.

The Yule Cat, Jólakötturinn, is a monstrous giant cat that devours innocent souls that have not received any new clothes to wear before Christmas Eve.

Jóhannes úr Kötlum also wrote about the cat. Here’s the poem, translated by Vignir Jónsson:

You all know the Yule Cat and that Cat was huge indeed.

People didn't know where he came from or where he went.

He opened his glaring eyes wide, the two of them glowing bright. It took a really brave man to look straight into them.

His whiskers, sharp as bristles, his back arched up high. And the claws of his hairy paws were a terrible sight.

He gave a wave of his strong tail, he jumped and he clawed and he hissed. Sometimes up in the valley, sometimes down by the shore.

He roamed at large, hungry and evil in the freezing Yule snow. In every home people shuddered at his name.

If one heard a pitiful "meow" something evil would happen soon. Everybody knew he hunted men but didn't care for mice.

He picked on the very poor that no new garments got for Yule - who toiled and lived in dire need.

From them he took in one fell swoop their whole Yule dinner always eating it himself if he possibly could.

Hence it was that the women at their spinning wheels sat spinning a colorful thread for a frock or a little sock. Because you mustn't let the Cat get hold of the little children. They had to get something new to wear from the grownups each year.

And when the lights came on, on Yule Eve and the Cat peered in, the little children stood rosy and proud all dressed up in their new clothes.

Some had gotten an apron and some had gotten shoes or something that was needed - That was all it took. For all who got something new to wear stayed out of that pussy-cat's grasp he then gave an awful hiss but went on his way.

Whether he still exists I do not know. But his visit would be in vain if next time everybody got something new to wear.

Now you might be thinking of helping were help is needed most. Perhaps you'll find some children that have nothing at all.

Perhaps searching for those that live in a lightless world will give you a happy day and a Merry, Merry Yule.

Of all the members of the family, the Yule Cat is the most recent one, with written accounts only as recently as the 19th century. The story was likely created by farmers to ensure their workers finished their weaving, knitting, and sewing by the dead of winter. The reward for those who took part in the work was a new piece of clothing. Those who were lazy received nothing. The Yule Cat was used as an incentive to get people to work harder.

Resuming, we have an abusive mother that haunts and eats naughty children, a spineless father who stays at home all day doing nothing, thirteen rebellious children who seem to have been hanging out too much with Santa, and a giant cat that eats people. I would give anything to see how their Christmas dinners are like.

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

Urge yaoi

#Would you believe me if I said these were lazytown characters#Yeah thats why I’m not putting in the main tags#Art#painting#digital art#gay#yaoi#lol#men in love#art#homo#drawing#Icelandic folklore#tw nudity#cw nudity#suggestive#nudity

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Business as usual

#iceland#Icelandic murder whale folklore#icelandic folklore#murder whales#evil whales#illhveli#nordic

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

#yuletime#yule cat#icelandic folklore#icelandic mythology#winter solstice#traditional art#watercolor#drawing#my art#artists on tumblr#illustration#happy yule#yule

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Terrifying Earth - The Yule Cat

youtube

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

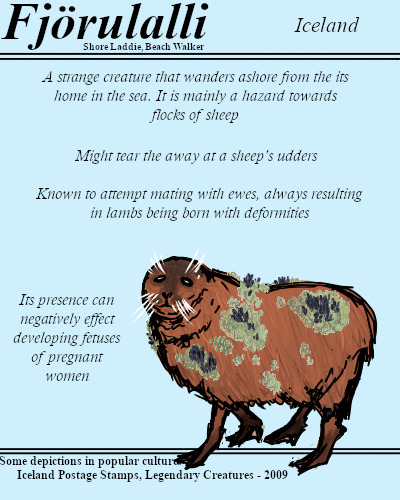

An unwanted creature, highly abhorrent to those who keep sheep. It is a notable detriment that has tendencies to wander ashore and stalk the coastlines, on the lookout for ewes to approach.

#BriefBestiary#bestiary#digital art#fantasy#folklore#legend#myth#mythology#monster#fjörulalli#shore laddie#beach walker#icelandic folklore#icelandic legend

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

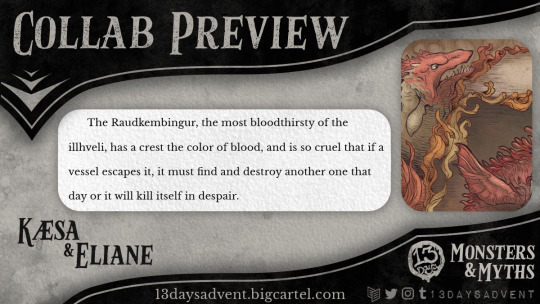

Hey guys, I'm excited to show off some snippets of the monster descriptions I've been writing for the 13 Days: Monsters & Myths zine! The third and final sample I have for you is illustrated by @feusus and is about a collection of Icelandic sea monsters known as the illhveli, or evil whales.

If you want to see the full piece and all! six! malevolent! whales! (plus a free bonus fish) go check out @13daysadvent and buy a copy of the zine & advent calendar before August 2!

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

I like the straightforwardness of the Icelandic approach to ghosts. Elsewhere in Europe it's vaguely unsettling apparitions, but in Iceland a gang of reanimated corpses will break into your house and beat you to death. Icelandic folklore is like European folklore directed by Quentin Tarantino.

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Deacon of Dark River

Hello friends, spooky season continues and I am here once more with a translation of one of my favourite Icelandic ghost stories, this time The Deacon of Myrká. This one is also a Christmas story! A gift for all seasons. This one also comes with a song version: Djákninn á Myrká by Rósa Ingólfsdóttir. And apparently there was a ballet too, which sounds cool as fuck and if anyone has a recording, hmu. The music for that, by Alex Cook, Hlér Kristjánsson and friends, can be found here on Bandcamp.

As with Bjarna-Dísa, I am translating the text from Snerpa here.

There are some notes for people unfamiliar with Icelandic placenames and folklore conventions at the end of the story - these will give added context to some events, but are also mild spoilers. There are also content warnings.

The Deacon of Dark River

In earlier times, there was a deacon at Myrká in Eyjafjörður; no mention is made of what he was called. He was courting a woman called Guðrún; according to some accounts, she lived at Bægisá, on the other side of the Hörgá River, and she was a serving woman to the priest there. The deacon had a grey horse, and rode him often; he called the horse Faxi. One time, a little before Christmas, it happened that the deacon went to Bægisá to invite Guðrún to a Christmas party at Myrká, and he promised her that he would meet her at the appointed time and accompany her to the party on Christmas Eve. The day before the deacon had gone to invite Guðrún, there had been a heavy snowfall and it was icy out: but the same day that he rode to Bægisá, there had been a rapid thaw, and as the day passed, the river became impassable because of the rushing water and ice floes, while the deacon was delayed at Bægisá. When he left there, he thought little of what had happened during the day, and expected that the river would still lie as it had before. He crossed over Yxnadalsá by bridge; but when he came to Hörgá, the river had burst its banks. He therefore rode along the bank until he reached Saurbær, the next farmstead over from Myrká; there was a bridge over the river there. The deacon rode onto the bridge, but when he came to the middle, it collapsed beneath him and he fell into the river. The next day, when the farmer at Þúfnavellir rose from his bed, he saw a horse in riding gear at the far end of the hayfield and thought he recognised Faxi, the horse of the deacon of Myrká. He was surprised at this, because he had seen the deacon leave the day before, but was not aware he had returned, and so soon suspected what must have happened. So he went down to the end of the hayfield; there, as he had thought, was Faxi, all wet and in a sorry state. Then he went down to the river, out along the point called Þúfnavallanes; there he found the deacon washed up lifeless on the farthest point of the promontory. The farmer went immediately to Myrká to tell them the news. The deacon was badly injured in the back of the head from the ice floes when he was found. Like this, he was brought home to Myrká and buried the week before Christmas.

From the time that the deacon went to Bægisá up until Christmas Eve, no news passed between Myrká and Bægisá about this event, because of the thaw and the flooding. But on Christmas Eve, the weather was calmer and the river had gone down in the night, so that it seemed a good idea to Guðrún to go to the Christmas party at Myrká. As the day wore on, she went to get herself ready, and when she was well on the way with that, she heard a knock at the door; another woman went to the door, which was next to her, but saw no one outside, and it was neither bright outside nor dark, because the moon waded through the clouds and drew them back and forth. When this girl came back inside and said she hadn’t seen anything, Guðrún said, “The game must be for me, and of course I will go out.” She was then entirely ready, except that she had yet to put on a cassock. Then she took up the cassock and put on one sleeve, but flung the other over her shoulder and wrapped it about her like that. When she came outside, she saw Faxi standing in front of the doors and a man next to him that she thought must be the deacon. It is not said that they exchanged any words. He took Guðrún and set her on the back of the horse and he himself sat in front of her. They rode like this for a while, not speaking. Now they came to Hörgá, and the river was high in its banks, and when the horse plunged forward off the edge, the deacon’s hat lifted up at the back, and Guðrún saw his bare skull. At that moment, the clouds drifted away from the moon; then he said:

The moon rises,

the dead ride;

can’t you see the white mark

in the back of my skull,

Garún, Garún?

And she was startled at this and fell silent. But some say that Guðrún lifted up his hat at the back and saw the white skull; then she had had no choice but to say, “I see that which is there.” No more is said of their conversation, nor of their journey, before they came home to Myrká, and they dismounted there in front of the lychgate; then he said to Guðrún:

Wait here, Garún, Garún,

while I bring my Faxi, Faxi

up to the yard, the yard.

Having said this, he went with the horse; but she looked into the churchyard. There she saw an open grave and became very afraid, but to save herself, she grabbed hold of the bell-rope. At that moment, she was seized from behind, and it was fortunate for her that she had not had time to put on more than one sleeve of the cassock, because so mightily was she gripped that the garment split apart at the shoulder-seam of the sleeve that she had on. And the last she saw of the deacon’s journey was that he flung himself with the torn cassock, which he was still holding, down into the open grave, and gravedirt from both sides was swept in on top of him.

And there is this to tell about Guðrún, that she rang the bell continually until the inhabitants of Myrká came out and found her, because she had become so afraid from all this that she dared neither leave nor stop ringing the bell, because she was almost certain that she had encountered the revenant corpse of the deacon there, though she had not previously heard of his death, and she was later certain of it, when she got word from the people of Myrká, who told her the whole story of the deacon’s death, and she in return told them about the journey of the two of them. That same night, when everything was over and the lights had been extinguished, the deacon came and sought out Guðrún, and there were so many wicked tricks that everyone was woken up, and no one slept that night. Half a month after this, she could never be alone, and needed a watch kept over her every night. Some say that the priest had to sit by her bedside and read psalms.

Now a sorcerer was summoned from Skagafjörður in the west. When he came, he had them dig up a large stone from the end of the field and roll it back to the main hall. During the evening, when it grew dark, the deacon came and wanted to get into the farmstead, but the sorcerer forced him south in front of the hall, and settled him there with many great wounds; then he rolled the stone down on him, and there the deacon rests to this very day. After that, all the hauntings at Myrká ceased and Guðrún began to be more lively. A little later, she went home to Bægisá, and it is said by people that she was never the same as before.

~

Notes: There are some ~potentially significant~ names that appear in this narrative. They’re not suspiciously apposite, but it might be nice for the reader to know that the deacon’s home of Myrká means Dark River, with many of the other placenames in the story also containing the river suffix -á, and that the first syllable of the name Guðrún refers specifically to the Christian god (as opposed to goð for other gods). The undead and other unholy creatures are generally held to be unable to pronounce the name of God. This is perhaps because, somewhat unintuitively, it's pronounced Gvuð. It's also worth knowing that Christmas Eve is generally considered a deeply haunted time in Icelandic folklore and many supernatural events occur on it.

Content warnings: death by drowning, the undead

6 notes

·

View notes