#he has intense innocence in the purity of his beliefs

Text

i love this moment bc you can SEE her regaining faith in their people, you can SEE her thinking... is that... the Mand'alor?

and i believe SHE was meant to see the Mythosaur, not Din. That's why he fell. It represents how he'd fall without her support and the support of others. The new Dawn may never come unless she and others step up behind him. The Mythosaur was a message for Bo Katan to follow Din - to die for him if necessary (as her father did, as her sister did), a message that she can have redemption and peace for her past and pain, and save Mandalore like she always dreamed.

If she just believes in this innocent fool.

#he has intense innocence in the purity of his beliefs#and its what they need#thats why he and grogu get along so well#their innocence#despite being a warrior despite being a 50 yr old survivor in grogus case#their innocence remains#bo katan kryze#din djarin#the mandalorian#i hate that shed die but also they believe dying for their ppl is their greatest honor so its a satisfying end if jt happens

173 notes

·

View notes

Photo

ANDROMEDA BLACK is TWENTY-FIVE YEARS OLD and a TRAINEE DEFENCE BARRISTER in THE DEPARTMENT OF MAGICAL LAW ENFORCEMENT at THE MINISTRY OF MAGIC. She looks remarkably like EMMA MACKEY and considers herself NEUTRAL. She is currently TAKEN.

→ OVERVIEW:

tw: death, murder

A kind hearted woman with a pure soul, Andromeda Black is considered a joy by all who know her well, though many people are often too overwhelmed by the idea of her very famous family to even give her a chance. The middle daughter of CYGNUS and DRUELLA BLACK, Andromeda has spent her life in the shadow of her family name which although she loathes, is something she has come to accept. Raised on the spralling Black family estate in Hertfordshire, cloaked by magic and woodland to shield them from the eyes of Muggles. Brideswater Manor, had been in the family for centuries and would become the first institution Andromeda would recognise. Her family home was never one of true happiness and often felt empty to her as a child, busy only with servant staff and the shrill voice of her mother as she attempted to tame her eldest sister BELLATRIX. Druella had never seemed a natural mother to Andromeda, but rather a woman who was told it was imperative to have children to continue the lineage of The Noble and Most Ancient House of Black. It also became clear to Andromeda as she got older, the pair had kept trying for a male successor but had given up by the time they had reached NARCISSA as her mother couldn’t bear the thought of having any more children who further destroyed her figure with every pregnancy.

An ideal daughter, Andromeda was dutiful, quiet and the easiest to raise of her siblings. She spoke when she was spoken to and rarely had an opinion that passed her lips. From a strict family with traditional values who upheld the belief that their blood status made them more important than other people in the wizarding world, Andromeda learned from any early age the only opinion her parents wanted to hear was the one they had given them repeated back. Her eldest sister was happy to oblige, discussing at length her disgust of Muggles and loathing of Muggle-Born witches and wizards which made their father beam with pride and their mother fan herself vigorously. A practical witch who hated vulgarity, her mother was always the fondest of her younger sister Narcissa, who shared her love of beautiful things and desire for perfection. Despite being the perfect child, Andromeda was the decidedly unspecial child to both of her parents they could rely on for good behaviour. Their middle child was the trustworthy daughter they could introduce easily to other members of notable families without family affairs ending in the tears of the other children.

Arriving at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry just as her sister was leaving, Andromeda’s reputation had already preceded her due to the wild antics of her eldest sister, meaning making friends outside of the Black family pre-approved list was fairly out of the question. Given a place in Slytherin, Andromeda liked to believe it was her intelligence and determination that had gained her a position in the house rather than her surname, but found her house was both a blessing and a curse. Although she made firmer friends with a few people she had known since childhood, it also meant people had already formed a presumption about her character which was made worse by her house having a reputation for stringent beliefs. Although her family had quite strict ideas regarding blood purity, Andromeda had never truly felt convinced by the idea her family were any better than any other magical families due to their lack of Muggle blood, which intensified during her time at school. Faced with very talented students from different backgrounds, Andromeda’s earlier suspicions were confirmed that blood had nothing to do with magical ability. Slowly she began to cast her social circle wider and associate beyond those who were raised within The Sacred Twenty-Eight.

It was becoming a prefect in her fifth year that she was first introduced to someone who would later become a very close friend to her. EDWARD TONKS, was a Muggle-Born student who truly changed Andromeda’s outlook on blood purity for the better. A fun and friendly student with an aptitude for subjects such as Charms and Herbology that outshone even Andromeda’s own, she became quite taken with the young wizard who she formed a close but secret friendship with. Although Andromeda was becoming more confident in her own worldview, people were still cruel toward her, Ted’s best friend AMELIA BONES, who has always been distrustful of Andromeda for not separating herself from her family, especially after her cousin SIRIUS renounced their family. After Sirius was burned off the wall of 12 Grimmauld Place, it became even more apparent to Andromeda their family would never change their outlook, but now making her opinions known meant she had something to lose. Her views were different, but the intense love she felt for her family was what bound her to them. Though she disliked the comparison between herself and her sisters Andromeda knew she could never leave them, an internal conflict of interest that resulted in her becoming closer to her boss RODOLPHUS LESTRANGE.

A friend of her sister’s from school, and the mentee of her father’s Rodolphus had always been in Andromeda’s life to some extent since she was a teenager. When her father had taken him on as a trainee she recalled him spending many evenings at their home, working silently with her father in his study or attempting to exchange polite conversation with her family which was often impossible when her older sister was in the house. After graduating from Hogwarts, Andromeda had expressed an interest in her father’s work at the Ministry and knowing he was about to be taking a position as Judge, requested to be able to shadow Rodolphus for a few weeks to learn more closely how their job functioned which turned into him offering her a job as his trainee. At first Rodolphus was quite cold toward Andromeda, keeping their relationship strictly professional, seemingly enjoying to watch her run around after him and sacrificing what was left of her personal life as he piled research work upon her for the cases they dealt with. It had taken a few years of working in close proximity with one another as his assistant before the two became friendly, with Andromeda spending most evenings at his home than she did with her own family or later with her friends after she moved out. Despite his exterior, Andromeda enjoyed his company as someone who expressed a desire to bring her own within her career despite her family name which she’d tried to seperate herself from her entire life.

Presently the two have begun working on a very difficult case which has changed from their usual clients. SILAS CRUMP, is an unregistered werewolf wrongly accused of killing a witch in Fleet Street, with an odd story that Andromeda found too striking to turn down. Supposedly found by a witch and wizard he can’t recall the names of, Silas was put under the Imperius Curse and given a false memory both Andromeda and Rodolphus can’t seem to be able to break through. The pair have been trying to find other cases of other magical creatures with similar stories, as werewolf and vampire related crimes have recently been on the rise. Eager to win the case, Andromeda has been attempeting to pick the brains of Ted who works at The Daily Prophet and follow up on any leads that may result in getting Silas off without a trip to Azkaban. Andromeda felt as though she was making headway with the case until the body of the Minister’s son BOOKER BAGNOLD was found floating in the Ministry fountain on Halloween. With Silas attached to the killing though he swears he is innocent, Andromeda will stop at nothing to ensure he walks free and set an example for other magical creatures who have been falsely improvised for crimes they did not commit. Though her thinking goes against that of her family, Andromeda is passionate about making a difference in the world which secretly allows her to bury her head in her work rather than focus on the negative effect her own family is having on a society she is attempting to better.

→ ADDITIONAL INFORMATION:

Blood Status → Pure-Blood

Pronouns → She/Her

Identification → Cis Female

Sexuality → Demisexual

Relationship Status → Single

Previous Education → Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry (Slytherin)

Societies → Pura Sorores

Family → Cygnus Black (father), Druella Black (mother), Bellatrix Black (sister), Narcissa Black (sister) Orion Black (uncle), Walburga Black (aunt), Sirius Black (cousin), Regulus Black (cousin/colleauge), Axel Rosier (deceased uncle), Adèle Rosier (aunt), Evan Rosier (cousin), Alexandra Rosier (cousin)

Connections → Lyra Burke (best friend/housemate), Adrasteia Greengrass (best friend/housemate), Rosalie Flint (best friend), Aaliyah Gosforth (best friend), Edward Tonks (close friend/potential love interest), Rodolphus Lestrange (close friend/boss/potential love interest), Amelia Bones (adversary/colleague), Silas Crump (client)

Future Information → Eventual Member of The Order of The Phoenix, Wife of Edward Tonks, Mother of Nymphadora Tonks

ANDROMEDA BLACK IS A LEVEL 6 WITCH.

#andromeda black#emma mackey#sex education#marauders#andromeda tonks#rpg#witch#taken neutral#neutral#ministry#magical law enforcement#wizgamot#magic#black#taken#taken lgbtqia+#taken witch

13 notes

·

View notes

Link

Nature has given humanity a roughly one-to-one ratio of adult men to women, but the most attractive women are being taken out of circulation to either join alpha male harems or participate in degenerate lifestyle choices. This leaves the average man practically no choice in settling down with a mentally stable and cute woman in her prime.

In Islam, a man is able to marry four wives, which is what my wealthy Iranian grandfather did on his way to siring 24 or so children that included my dad (the exact number is a mystery). He took away three women that an Iranian man of lesser means could have married, creating a societal imbalance, but that’s nothing compared to what we have in the modern Western world, where a single famous man can command the sexual attentions of dozens—if not thousands—of women in their sexual prime, spoiling these women for normal men who don’t have the ability to tingle their vaginas with the same intensity.

How many actors, musicians, and sports athletes are trying to plow through as much prime pussy as possible? How many Hollywood directors and music producers are leveraging their positions for sexual gain? How many club owners, restaurateurs, Arab sheikhs, and politicians are doing the same? Each one is taking way more beautiful women out of circulation than men like my grandfather, all while elevating their standards to such an extent that no average man can ever gain their love, let alone two hours—or even two minutes–of their uninterrupted attention.

We also have to account for female lifestyle choices that are designed to delay or prevent pair bonding and marriage. The biggest is career. Most girls, while embarking on a career, balance out the boredom of working a meaningless job by hopping on the cock carousel and banging at least a few men every year. By the time a girl hits 25 years old, any man who meets her will have to deal with a walk-in closet of emotional issues and hang-ups from being pumped and dumped as much as a 1930’s brothel whore.

Then there is the Instagram and Facebook lifestyle that creates crippling dopamine addiction, which causes a girl to only be satisfied if dozens of men are actively thirsting for her every day. I estimate that if a girl has over 500 followers on Instagram, she is so used to attention from throngs of men that the love of one man cannot possibly satisfy her.

We must also throw in the growing “travel blogger” lifestyle where, instead of using only her body to get attention, a girl uses pictures and video from exotic locations to enhance her beauty. Other girls, with nothing substantial to offer the world, decide to showcase pictures of pets or their tasty overpriced meals, but even that puts them on a dopamine loop that ruins their future interactions with men.

By far, the most damaging lifestyle choice women make is becoming a sugar baby, a politically correct term for “prostitute.” For some easy cash, she whores out her body to the highest bidder (some women combine Instagram and prostitution in a seamless package). How can such an Instagram prostitute ever settle down with a man who has a normal salary? There are also the hundreds of women who enter porn every year, some from seemingly stable families. Sadly, men are so desperate for love that many would wife up a former prostitute or porn star, but it’s highly unlikely those women will make for stable families.

The Western world is a sinkhole for women. The prettiest of the bunch fall into the hole and get spit out years later an entitled #MeToo hag who can never be happy, making the Islamic four-wife rule seem downright egalitarian. The sad truth is that if you meet an attractive girl today, she was pumped and dumped by numerous sexy men, prefers to nurture her career than children, is addicted to attention via the internet, and has participated in some kind of scheme to exchange social status or cash for her pussy. She’s more than suitable for a bit of fun, but would it be wise to seek a relationship with her?

Even with the obesity and short-hair epidemic, I still see a bountiful supply of cute girls I would happily reproduce with. I would love them, let them caress my beard, and lay my seed deep within their vaginal guts, but the problem is that those guts are not for me—they are for the Chads who would never marry her, the beta orbiters who await her newest selfie as if it were a source of food, or the rich and lonely men who would sponsor her for thousands of dollars a month. They’re taking her out of circulation at the time I want her most, and by the time they are done with her, I no longer want her. I guess I’ll try to weasel in a bang or two when she is not yet fully degraded, and enjoy the fleeting pleasure that comes from it as much as I can.

https://www.rooshv.com/how-to-stop-the-fall-of-women

An acronym that you’ll often come across is AWALT, which stands for “all women are like that.” It is used in response to someone trying to point out that a particular woman is different than all the rest and more deserving to be placed on a pedestal of some sort when it comes to relationships. While that acronym is useful for newbies who are just beginning to de-program themselves from egalitarian ideas spewed by the establishment, it breeds a hopelessness among men that they can never extract more than casual sex from women.

Most men have seen firsthand how women change due to the presence of corrupting factors in the environment. If you give a woman an open bar, she will over-consume and make decisions that harm herself. If you give a woman a smartphone with social networking apps, she will become a narcissist in a short amount of time, falling in love with her own image. If you give a woman a liberal education, she will come to firm belief than men were born to bring pain and slavery unto women.

Only a woman with an exceptional upbringing can resist alcohol, social networking, and university brainwashing, and for the women who can initially resist it, she will surely succumb after enough time and pressure. It is in this way that AWALT is true: all women who face corrupt influences in their lives will become corrupt and behave in a similar way that degrades their virtue, making them unsuitable for long-term partnerships. But if AWALT is true in describing the universal fall of women in the presence of toxic influences, it must also be true that they possess universal purity in environments which lack bad influences that attack her virtue.

A reliable corrupter of a woman’s virtue is having plentiful male choice. If over the course of five years a woman in New York City has her choice of 100 alpha male cocks, she will be unable to resist the thrill ride that these men offer. She will begin to structure her life around a neverending alpha male sex party where she receives and expects fun, excitement, drama, and entertainment in exchange for willingly accepting her place on various booty call rotations. During this time, she loses most ability to be a suitable wife and mother, or even to be a good person, because the alpha males who use her for late night sex do not place demands upon her that make her more feminine, loving, or nurturing. She becomes damaged goods, suitable for nothing more than casual humping.

But now let’s imagine that instead of being born in New York City, this girl was born in a poor Ukrainian village that only has a population of 1,000 people. For whatever reason, she was unable to get out of this village and a complete blackout of internet prevents her from meeting thirsty foreign men. It’s quite easy to see how she marries a village man while still young because it’s a better prospect than suffering alone to earn her bread in a place where employment opportunities are few. The environment a girl is placed in will mostly determine her worth as a life partner.

Most women who are put in New York City will, within a few years, default to becoming a promiscuous slut. Most women who are put in a tiny village with no way out, with little choice in men, and with positive religious influences, will default to being a good wife and mother, possessing normal and acceptable human flaws like all men have. Women put in specific environments will act in specific ways, which is why looking for a unicorn in a Western city is fruitless, since she’s within reach of the devil’s workshop. He will get to her and make sure she experiences all manner of vice.

Western nations facilitate the “fall” of women from a state of purity and innocence to one of abject corruption. I don’t believe women are inherently born to be degenerate, just like how I don’t believe men are, but once we put a woman in an environment that enables, facilitates, and even encourages her corruption, she will certainly become corrupt. But what if you can catch a woman before she inserts herself into this environment and then shield her from it? What if you grab her at the time she is about to jump into the abyss, and through your diligence, power, and knowledge, protect her from Western influences that will destroy her? Would it be safe to give your time, energy, love, and commitment to this woman? It’s important to note that I’m not stating you save a corrupt girl, since by then it’s too late, but to prevent a woman from becoming corrupt in the first place.

It is completely your responsibility to create the environment of a good home, a good city, and a good country to prevent the fall of your women. It’s your responsibility to create the right environment where all women remain good instead of succumbing to an evil where within a short amount of time she becomes a useless, tattooed, overweight, and masculine slut. It should be clear to you by now that women absolutely can not save themselves, and have no inherent resistance to the pollution that tempts them in this world. It’s solely up to us men to shield their natural virtue so that they become the wives and mothers that allow you to fulfill your biological destiny while furthering the health of your society.

It’s not a matter of telling a girl that sleeping around is bad or that Facebook is bad, because by then the ship has sailed and her soul is likely long gone. It’s a matter of creating the environment where women are restrained from sleeping around, blocked from becoming addicted to taking selfies, and prevented from becoming brainwashed by social justice ideas. We must stop them from entering the environments that destroy them. We must guard the door of evil that they are hurtling themselves towards while resisting evil ourselves.

Before you raise your hands in despair and claim that this is an impossible task, that Western society is finished, I say this: what is a society but a collection of the people within it? What is a society but an assembly of living humans that include ourselves? We are a part of this whole, and it’s up to us to ensure that the truism of “all women are like that” serves in our benefit and our society’s benefit instead of being at the forefront of our most terrifying nightmares.[culturewar]

Read Next: Women Must Have Their Behavior And Decisions Controlled By Men

After a long period in society of women having unlimited personal freedom to pursue life as they wish, they have shown to consistently fail in making the right decisions that prevent their own harm and the harm of others. Systems must now be put in place where a woman’s behavior is monitored and her decisions subject to approval of a male relative or guardian who understands what’s in her best interests better than she does herself.

Women have had personal freedoms for less than a century. For the bulk of human history, their behavior was significantly controlled or subject to approval through mechanisms of tribe, family, church, law, or stiff cultural precepts. It was correctly assumed that a woman was unable to make moral, ethical, and wise decisions concerning her life and those around her. She was not allowed to study any trivial topic she wanted, sleep with any man who caught her fancy, or uproot herself and travel the world because she wanted to “find herself.”

You can see this level of control today in many Muslim countries, where expectations are placed on women from a young age to submit to men, reproduce (if biologically able), follow God’s word, and serve the good of society by employing her feminine nature instead of competing directly against men on the labor market due to penis envy or feelings of personal inferiority.

The reason that women had their behavior limited was for the simple reason that they are significantly less rational than men, in a way that impaired their ability to make good decisions concerning the future. This was eloquently described by German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer in his important essay On Women. He described them as overgrown children, a comparison that any man who has dated more than a dozen of them can quickly agree to after having consistently witnessed their impulsive and illogical behavior firsthand.

Women are directly fitted for acting as the nurses and teachers of our early childhood by the fact that they are themselves childish, frivolous and short-sighted; in a word, they are big children all their life long—a kind of intermediate stage between the child and the full-grown man, who is man in the strict sense of the word. See how a girl will fondle a child for days together, dance with it and sing to it; and then think what a man, with the best will in the world, could do if he were put in her place.

[…]

…women remain children their whole life long; never seeing anything but what is quite close to them, cleaving to the present moment, taking appearance for reality, and preferring trifles to matters of the first importance.

[…]

That woman is by nature meant to obey may be seen by the fact that every woman who is placed in the unnatural position of complete independence, immediately attaches herself to some man, by whom she allows herself to be guided and ruled. It is because she needs a lord and master.

When you give a female unlimited choice on which man to have sex with, what type of man does she choose? An exciting man who treats her poorly and does not care for her well-being.

When you give a female choice on what to study in university, what does she choose? An easy liberal arts major that costs over $50,000 and dooms her to a life of debt and sporadic employment.

When a female lacks any urgent demands upon her survival, what behavior does she pursue? Obsessively displaying her half-naked body on the internet, flirting with men solely for attention, becoming addicted to corporate-produced entertainment, and over-indulging in food until her body shape is barely human.

When you give a female choice on when to have kids, what does she do? After her fertility is well past its peak, and in a rushed panic that resembles the ten seconds before the ringing of the first school bell, she aims for limited reproductive success at an age that increases the likelihood she’ll pass on genetic defects to her child.

When you give a female choice of which political leader to vote into office, who do they vote for? The one who is more handsome and promises unsustainable freebies that accelerate the decline of her country.

When you give a female unwavering societal trust with the full backing of the state, what does she do? Falsely accuse a man of rape and violence out of revenge or just to have an excuse for the boyfriend who caught her cheating.

When you give a female choice on who to marry, what is the result? A 50% divorce rate, with the far majority of them (80%) initiated by women themselves.

While a woman is in no doubt possession of crafty intelligence that allows her to survive just as well as a man, mostly through the use of her sexuality and wiles, she is a slave to the present moment and therefore unable to make decisions that benefit her future and those of the society she’s a part of. Once you give a woman personal freedom, like we have in the Western world, she enslaves herself to one of numerous vices and undertakes a rampage of destruction to her body and those who want to be a meaningful part of her life.

A man does not need to look further than the women he knows, including those in his family, to see that the more freedom a woman was given, the worse off she is, while the woman who was under the heavy hand of the church or male relative comes out far better on the other side, in spite of her rumblings that she wants to be as free as her liberated friends, who eagerly and regularly post soft porn photos of themselves on social networking and dating sites while selecting random anonymous men for fornication every other weekend.

Men, on average, make better decisions than women. If you take this to be true, which should be no harder to accept than the claim that lemons are sour, why is a woman allowed to make decisions at all without first getting approval from a man who is more rational and levelheaded than she is? It not only hurts the woman making decisions concerning her life, but it also hurts any man who will associate with her in the future. You only need to ask the many suffering husbands today on how they are dealing with a wife who entered the marriage with a student loan debt in the high five figures from studying sociology and how her wildly promiscuous sexual history impairs her ability to remain a dedicated mother, with one foot already out the door after he makes a reasonable demand that is essential for a stable home and strong family.

I propose two different options for protecting women from their obviously deficient decision making. The first is to have a designated male guardian give approval on all decisions that affect her well-being. Such a guardian should be her father by default, but in the case a father is absent, another male relative can be appointed or she can be assigned one by charity organizations who groom men for this purpose, in a sort of Boy’s Club for women.

She must seek approval by her guardian concerning diet, education, boyfriends, travel, friends, entertainment, exercise regime, marriage, and appearance, including choice of clothing. A woman must get a green light from her guardian before having sex with any man, before wearing a certain outfit, before coloring her hair green, and before going to a Spanish island for the summer with her female friends.

If she disobeys her guardian, an escalating series of punishments would be served to her, culminating in full-time supervision by him. Once the woman is married, her husband will gradually take over guardian duties, and strictly monitor his wife’s behavior and use all reasonable means to keep it in control so that family needs are met first and foremost, as you already see today in most Islamic societies. Any possible monetary proceeds she would get from divorce would be limited so that she has more incentive to keep her husband happy and pleased than to throw him under the bus for the most trivial of reasons that stem from her persistent and innate need to make bad decisions.

A second option for monitoring women is a combination of rigid cultural rules and sex-specific laws. Women would not be able to attend university unless the societal need is urgent where an able-minded man could not be found to fill the specific position. Women would not be able to visit establishments that serve alcohol without a man present to supervise her consumption. Parental control software on electronic devices would be modified for women to control and monitor the information they consume. Credit card and banking accounts must have a male co-signer who can monitor her spending. Curfews for female drivers must be enacted so that women are home by a reasonable hour. Abortion for women of all ages must be signed off by her guardian, in addition to prescriptions for birth control.

While my proposals are undoubtedly extreme on the surface and hard to imagine implementing, the alternative of a rapidly progressing cultural decline that we are currently experiencing will end up entailing an even more extreme outcome. Women are scratching their most hedonistic and animalistic urges to mindlessly pursue entertainment, money, socialist education, and promiscuous behavior that only satisfies their present need to debase themselves and feel fleeting pleasure, at a heavy cost for society.

Allowing women unlimited personal freedom has so affected birth rates in the West that the elite insists on now allowing importation of millions of third world immigrants from democratically-challenged nations that threaten the survival of the West. In other words, giving women unbridled choice to pursue their momentary whims instead of investing in traditional family ideals and reproduction is a contributing factor to what may end up being the complete collapse of those nations that have allowed women to do as they please.

I make these sincere recommendations not out of anger, but under the firm belief that the lives of my female relatives would certainly be better tomorrow if they were required to get my approval before making any decisions. They would not like it, surely, but due to the fact that I’m male and they’re not, my analytical decision-making faculty is superior to theirs to absolutely no fault of their own, meaning that their most sincere attempts to make good decisions will have a failure rate larger than if I was able to make those decisions for them, especially with intentions that are fully backed with compassion and love for them to have more satisfying lives than they do now.

As long as we continue to treat women as equals to men, a biological absurdity that will one day be the butt of many jokes for comedians of the future, women will continue to make horrible decisions that hurt themselves, their families, and their reproductive potential. Unless we take action soon to reconsider the freedoms that women now have, the very survival of Western civilization is at stake.[culturewar]

Read Next: People Should Not Be Allowed Unlimited Personal Freedom

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

rambling about eddie and religion... mention of real-life suicide and homophobia

i really, really, really feel like eddie’s one of those types for whom religion feeds into all their worst thought patterns (and feeds off of them). like i’ve seen people very close to me consumed by wanting to be someone worthy of god’s love or by thinking themselves the self-righteous extension of god or just. it’s hard to describe but a certain kind of person, there’s no other word for it, it just consumes them. and eddie’s so perfectly set up for that.

it’s intensely obsessive and interesting and exciting and an important part of his character i’m deeply invested in, it’s very much like his early relationship with the symbiote and venom’s early sense of purpose, and just like that, it is actually very unhealthy. i think the times he went all-in on purity/corruption rhetoric and framed himself as a saviour and all that are like, totally in character, i don’t think it’s part of an agenda that his religiousness is mostly portrayed in extreme contexts, i think it makes perfect sense.

(the ultimate intent behind anti-venom is a mystery for the ages, but i think we can all agree he was at least several layers removed from reality.)

anyway, like, i’m sure you could develop eddie into someone who has a healthy relationship with and gains something from spirituality or whatever, if that was your goal, i’m not saying it can’t be done. but whenever i think of it i just think of the member of our community who kept coming to my almost equally messed up mom for advice on how to cope with being unable to spread the good word as he should and to live untainted by sin (read: he was gay) and who ended up disembowelling himself in his parents’ kitchen so like. someone who’s also that big on the notion of losing innocence and worth... also suicidal... also thinks he has a higher calling... it’s not gonna work for me.

i really felt like costa!eddie giving up on the belief in a higher power to please or feel possessed by or be punished by was a necessary part of his healing process. there’s the argument that religious doctrine could act as his conscience, asking god for forgiveness and all that, but mostly he’s just twisted it to suit whatever his agenda was, anyway, i think it was a symptom of him reexamining himself, not the cause. it wasn’t the cause of his twisted morality, either, but it sure boosted it.

what am i saying. i’m personally never going to be comfortable with eddie’s catholicism as a good thing, i think it’s harmful to him.

also i’m never going to take it in the internalised homophobia direction but that’s just a preference. it’s kind of canon, anyway, conway eddie was religious and still said Gay Rights. i think eddie’s, like i said, much more likely to twist the good word into whatever matches his intentions and to use them to give himself that extra self-righteous kick, that bit of obsessive zest, the validation that his ideas really are that transcendentally important. he is extremely anti-self-flagellation at first, and he thinks bonding and the symbiote are sacred, not opposed to his beliefs, but part of them. so i don’t necessarily think he’d feel bad about boinking it just because it’s not female. at least until, like, way later, when symbiote- and self-flagellation are in fact his intent and the church has handed him all the tools. god fucking knows canon has enough of those #vibes

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Arcana: A Mystical Fanfic Chapter II - A New Family

„What's the matter, already had enough?“, I heard Morga mock me as I found my face in the dirt for so many times that I have already gotten used to tasting my own blood mixed with the ground under me.

„ I'll give up...when you finally end me“, my words mixed with heavy panting as I made myself rise once again, only driven by sheer will power, since my body was on the verge of falling apart.

Morga's face lit up with a bright grin, I swear I could see flames in her eyes. She was pleased. „I would expect nothing less“, she said almost kindly, as she came at me once again.

This has become a common practice for the two of us, ever since I've started living among her tribe. I've enjoyed our „sparrings“, I've enjoyed how she always pushed me to my limits and made me expand them, more and more every time. I was bold to believe that she enjoyed them as well, she admired my will and spirit. Ever since I've joined them, she's been treating me like her own offspring. Now, don't mistake that for something loving and nurturing, no, not from a woman like her, a warlord. Her love was rough, intense, but great. The tougher time she gave me, the more I knew I was growing on her. She would never express emotions, except through her steel. Most of the people would think her cold and stark, but I knew her better than that, I saw through her rough facade.

I came to her tribe as a sorceress, to serve their every need in exchange for leaving my family and our land alone, but I became more than just that. I was never the type to sit on the bench while the others have all the fun, I craved action, adventure, unknown. Besides, what better way to get to know better the people I'm living with and their culture, tradition, beliefs, souls, than to ride side by side with them into battle?

Few years ago I've made this request to Morga, to train me in the ways of the warrior, and she will have me, not just because of our agreement, but body and soul too. She said she knew that it would turn out like this, during our first battle, she saw the spirit of a warrior inside me, and that she would be glad to strengthen it and get me to realize my potential.

Being a warrior also helped me ensure my security among these wildlings. Even though Morga was fond of me, her men were vile and savage, a drunken moment alone with any of them could cost me more than I could ever afford to lose. At first, during my arrival, I came up with a perfect white lie to help me protect my purity from the possible defilers. I've announced that my mystical abilities come from my virginity, and should I ever lose my chastity, the powers would also be gone with it. Morga said she would personally gut anyone who dares to compromise her sorceress with his filthy paws. This was effective, but not completely reassuring, so I had to make sure I felt safe, or at least safer around the men. I've seen how they watch me with something beastly in their glares, as wolves would stare at their next catch. This was understandable and expected – I was different from their women, more gracious, delicate, almost royal as far as they were concerned. And I was an outsider.

There was one other thing that was threatening to compromise this whole charade I've created. Montag.

Montag, or Monty as everyone called him, was Morga's only son, and heir. In any other surrounding this would mean that he was probably extremely pampered and spoiled, but not here. This only meant that she was giving him the hardest time of us all. I knew this meant that she loved him most, but I was pretty sure he did not see it that way. Monty was different from all of them. While everyone's goal was just to raid, pillage, plunder and wreak havoc, Monty was above all that. He was destined for greater things, I felt that must be true. He was ambitious, he was a dreamer, he wanted more of life than what he had here, he just wasn't sure how and what exactly, because he knew little of the world outside his tribe. I've enjoyed telling him stories of kingdoms, cities, world beyond. About magic, about spiritual world, about everything I loved, I shared my world with him and we dreamed together of what life can be. He was kind of bubbly, loud, overly energetic. His emotions were as transparent as if they were written on his forehead. Those were all qualities I loved him for...and Morga scolded him for. She considered them to be a sign of weakness, of a weak future leader she never wanted him to become. She believed he would've never survived on his own, and she reminded him of that all too often. But I believed them to be virtues, to be his strengths, to be exactly the things that make him a great human being that I saw him for. I've tried many times to make him see it that way, but in vain. My word could never compare with his mother's, every letter cutting into his heart and soul like a tiny knife. He would've never showed it, though. To anyone except me, that is. I was his oasis, his escape from reality, from his fears, troubles, doubts. And he was mine.

Of course, we had to keep our little oasis a secret, because it could make people talk and compromise my safety, and neither one of us wanted that to happen. Regardless of our discretion, I was almost certain that Morga knew everything. There was just no hiding from her. She always knew...everything. Even so, she never disapproved. I wondered why at first, but the answer came to me one day, as we celebrated one of our many victories.

I held a little ceremony, semi-religious, thanking the great spirits and forces for giving our warriors the strength to subdue our targets and crush them under our feet. They loved these ceremonies, with the mystical forces gleaming and flowing all around, fire coming out of the great bonfire and embracing my figure, spirits rising from all around and dancing around them in the form of a ghastly fog, filling their hearts with courage and sense of higher purpose. My magic has gotten even stronger during my time with the tribe, and I have truly become their seer, their sage. I would contact the Arcana for omens of victory or defeat, before battle I would encourage and bless the warriors using not only my magic and herbalist mixtures to enhance their potentials, but also motivational speeches to fill their hearts and minds with greatness and flames of passion and bloodlust. They were an unstoppable force, thoughts of defeat never even crossing their minds.

After the ceremony, we all got drunk together, danced around, sang and just enjoyed life to the fullest. I felt content, I've managed to accomplish a lot during these few years, I've managed to become a lot, a lot more than I could've ever dared to dream of. It was a lot of gamble and hard work, but in the end it payed off. I've just watched them all being merry and ecstatic, feeling of bliss filling every inch of me. They weren't the savages they once were, they were more than that now, they have evolved so much. I couldn't help but feel partially responsible for that, and I was glad. Murdering and pillaging was very hard for me at first, but I knew I had to do it to prove myself as one of them, as equal, to ensure my position. With my role as a sage, I was able to direct their attacks and actions through „omens“ and such, and protect the innocent people they would've destroyed as much as I could without seeming suspicious. Luckily, no one ever suspected a thing.

„So, are you just going to watch from your pedestal, oh great seer, or are you going to enjoy your victory with the rest of us?“, Monty cut me from my thoughts. I didn't even notice him coming, I was too lost in my own thoughts. He came up to me, giving me his hand, teasing me with his smirk, as he usually does.

„OUR victory, Monty. I couldn't possibly take all the credit, now could I?“, I smirked back at him, staring him right in the eye as I put my hand in his.

He pulled me into his strong arms, so hard I almost lost my balance, his eyes never leaving mine: „You're just being modest, as usual“, he continued mockingly. Staring into his unusually gray eyes made me lose my words, which was not something that happened to me often. I just let him lead me into the dance. This caused curious looks from the rest, but in that moment we trully couldn't care less. He was the only one there at that moment, his golden hair glimmering under the light of the Moon, flickering lights of the bonfire dancing on his pale skin. He wasn't much of a dancer, he was a much better warrior, but he knew a dance or two. Everything he ever did, he did so confidently, as if he was a god, no matter if he was actually good at it or not. I loved that about him, another one of his qualities I cherished.

We were so lost in the moment, that we've barely noticed the dance has stopped. He made a little clumsy bow at me, something not characteristic for his people's customs, but as I've mentioned earlier – he was above all that. I responded with the same curtsy. I've desired him so much for so long, and if I could've taken him with my eyes at that moment, I would've. It was so hard keeping the whole chastity act together all of this time. I wanted to be his, I wanted him to defile every inch of me right there on that spot.

As we stared into each other’s eyes with such incredible passion, we were interrupted by a familiar voice: “Mhysa, a moment in private. Now. Follow me”. Morga. Both Monty and I were startled and froze like kids after making a mess and getting caught in act by a parent. ”Y-yes, of course”, was all I could muster, after which I followed in silence. Monty only stood there awkwardly, like a statue.

She led me away from the crowd, into an isolated part in the woods. We stopped when the party sounds got far enough. She didn’t turn to face me, she looked into some distant spot as if lost in her own thoughts. After some time of chilling silence, she spoke: “My son and you…are acting very friendly lately, spending every possible moment together, alone”. My heart skipped a beat. What if she thinks we were intimate? What if, by my foolish behavior, led by emotions, I have finally blown my cover and now she is going to expose me and this will be the end of me? I couldn’t breathe and the thoughts kept running through my head, I had no idea how much time has passed before Morga spoke again, it could’ve been seconds, years, it was all the same to me. “Look, I know I’ve always been…hard on him. It might seem like I don’t care for him, but that’s not how it is. I do it BECAUSE I care. This world is cruel, especially our world, and if you’re not the toughest dog around, the other dogs will devour you. And he…he is so delicate and carefree, it’s making him weak, he is weak. And I won’t always be around to protect him, and when I’m gone…” I swear, this is the first time I’ve seen Morga open up to anyone ever and show…feelings? I wasn’t even sure if she was able to do that at all. The unease and worry were clear in her tone, she stopped for a moment, like she was catching breath, letting out a loud sigh before turning up to face me for the first time since we came to this place. I now understood she must’ve been ashamed to look at me while showing her own weakness and fears. The fact that she was now facing me, staring me right in the eye, confirmed just how brave she actually was. It’s easy facing enemies in battle while wielding a spear and charging in a leather armor, but to show your naked feelings to someone, completely unarmed and open, to let them see the real you, your true self – that takes real courage. “I am well aware that he is vulnerable and weak, clueless even. Maybe one day he will change, maybe he will not. Either way, I don’t want to take that chance. He’s…he’s my only boy. I don’t want to see him devoured by rabid wolves that surround him. However, I will not always be able to protect him. So, what I’m saying is…I need to know that you are going to look after him. I need you to promise me that”, she finished, words still heavy on her tongue. The look in her eyes was…almost pleading. Underneath that cold and rough exterior was an actual caring mother, genuinely worried for her son’s well-being. “Morga, I swear to you, I swear on my life that I will never let anything bad happen to Monty while I still hold breath”.

“Good”, she let the single word out with a sigh of relief. I could swear I saw something resembling a smile on her face. Second later, the mask was back on, as well as her standard grin: “Well then, we have a party to attend, let’s not keep the eager people waiting any longer”. As she passed me by, she slapped me on the back so hard it pumped the air from my lungs. I’ve let out a short chuckle and followed.

#fanfiction#fanfic#OC#The Arcana Game#the arcana: a mystic romance#the arcana: a mystical romance#count lucio#the arcana lucio#lucio#monty#montag#Morga#The Magicians#magic#sorcerer#magician#tarot#fantasy#warrior#spells#imagination#random scribbles#goat daddy#fan#daydreaming#fiction#fan made#fanmade#random#party

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

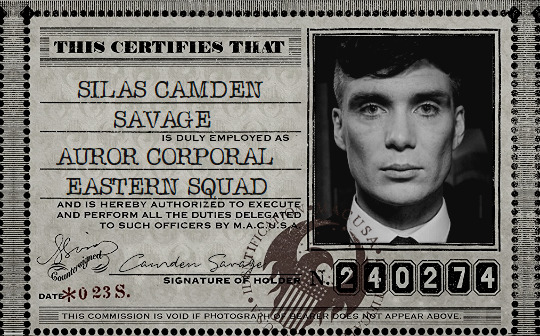

C A M D E N S A V A G E / A U R O R C O R P O R A L

AGE: Forty-Five

BADGE NUMBER: F01V25

BLOODSTATUS: Pureblood

GENDER/PRONOUNS: Trans Man, He/Him

IDENTIFYING FEATURES: Piercing blue eyes, high collars buttoned all the way up, severe haircut speckled with white, scarification (Sacred Heart on chest, several arrows on rib cage, crude flame on left wrist, upside down cross below that, eyes on the palm of left hand)

STRENGTHS/WEAKNESSES:

(+): Potion-making, decisiveness, precision, independence

(-): Combative magic, skewed moral compass, pretension, apathy, only truly respects older brother

BACKGROUND:

cw: self harm, body horror

Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are those who mourn, for they shall be comforted.

Poor in spirit, poor in body. So the kingdom has always been your family’s then, yes?

It has, at least in your parents’ minds, and your grandparents’, and your great-great grandparents’, and everyone before them. No matter what has changed in the world, the Savages remained just as they were. A snobbish upright morality, a longing for the past, when the world was right. And a desire to hold onto that, at least in their own households. A diminishing fortune that never seemed to take them off their high ground.

You were never going to be the strong one. There were stories of crusaders in the family, those who fought chivalrously for the family, for the community. But that wasn’t your calling, that was your brother. Your parents seemed to know that from the moment you were born, and decided on the path for you from the start, all by gifting you with a name, with no care for what your birth might’ve indicated you would be.

Silas Camden Savage.

The original Silas Savage came to America years and years ago, bringing with him a religion for all of the wixen population, preaching salvation and doling out mercy to the lost souls who seemed to believe religion was only for no-majs.

And so when you announced, after your older brother, that you were also a boy, your father took it as a divine sign, confirming what he had already come to believe, that you were meant to carry on Silas’ work, and help return the family to their religious importance.

The thing is, though, then, you were a follower. You followed your brother everywhere he went, did everything he did, looked up to him as a hero. You ate up every word your father spouted, easily believing whatever was said. And it felt a little bit like somewhere you had lost something. A little piece of yourself gone, and replaced with what you were meant to be.

That was your whole childhood, really, in a way, wasn’t it? Mourning. For self lost, independence lost, innocence lost. Always something lost, never something found.

But it’s a good life, a proud and blessed life, even when the robes you wore were barely better than rags, and the things you already preach fall on deaf ears upon leaving the safety of home. Sometimes you wonder if it might be easier to drop the Silas entirely, after graduating, to just stay Camden, or find who Camden is at all in the first place, to follow your brother to the aurors, and serve God in that way. But there’s this feeling in your soul that tells you Camden isn’t holy, Camden isn’t good.

So you pray and you pray and you pray and you beg for some kind sign

And a week before your graduation, you receive it.

You were never one to mourn, and so maybe it’s fitting that there was no time for comfort after your father’s death. Now you have to take charge.

Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth. Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they shall be satisfied.

After that, there wasn’t a meek thing about you, but in a way, that’s why you were always so effective.

You go from a student of magic to a student of God. Three years spent preparing to take vows, fitting in more seamlessly there than you ever had at school. You revel in it, finally feeling like you’ve found your place, your calling. You remember how passionately your brother always spoke of becoming an auror and that is how you feel about your work on the road to the priesthood. You’re doing what you were meant for, and saving souls, spreading the Word, all at once.

And maybe it helps that it’s a little like being royalty, in a way, being a Savage entering the priesthood. Maybe there some less than graceful thoughts when you’re recognized, when you shadow established priests, and you’re the one listened to as if Jesus himself is in the room.

You get your choice of assignments, even, and it’s no surprise that when you pray on the decision, you’re called to your own parish back at home. It’s only right, after all, to continue your work where your ancestor started his, to shepherd the flock your family has always been apart of. And the parish is blessed to have the new Father Silas saying their masses.

As time goes on, something changes, though. You can feel the hold that Satan has on the world, can feel his influence spreading, and you worry that perhaps you read your signs wrong and your father’s death wasn’t a calling, but a defeat.

Your sermons become more intense, your penance becomes harsher, you worry for the souls of your people as well as the souls of the world. Most of all, though, you worry for your brother, out amongst criminals and the darkness, trying so hard to make the world as good as he is. But you’ve heard just how evil the world can be, and you’re terrified that he’ll fall into the darkness, too.

You spend more time praying, more time visiting him, when you can, unable to keep from wondering if there’s something more you should be doing. But isn’t that part of the job? You shoulder the burdens of those who have faith, you watch over them, you pray for them and take their worries, to give them that chance at peace, that chance at goodness.

There’s something there in the pit of your stomach as time goes on, though. A hunger and a thirst deep within you for something more, docile, but waiting to be awakened when the time is right. You think it’s a hunger for goodness, for justice, but sometimes late at night your thoughts turn to the what ifs, the greedy, prideful things you want, things you’ve done, and it’s hard to know if it’s just the devil tempting you, or if it’s your nature.

You’ve gotten good at ignoring the things that don’t fit with what you should be, though, and so you continue on your quest for salvation, passing on the grace of God that you have found to those who need it the most, watching over your flock, building a life of good, just as the last Silas Savage did.

Blessed are the merciful, for they shall be shown mercy.

But why should you show mercy when no one has shown mercy to the person who matters most to you?

You’re in the middle of writing a sermon when you receive the news. An injury, out on a case, the sort of thing you’ve spend countless nights praying to never hear, countless candles lit to protect him, countless sinful thoughts hoping someone else might take his harm and keep him safe, since you can’t be there.

That moment, suspended in time, is a moment that changes it all. Terrible things that no prayer could prevent, terrible things happening to a person who has done nothing but good, no mercy in sight, despite everything he’s tried for.

God has a plan, God looks after those who do His will.

Does He?

God helps those who help themselves.

That feels more like it.

Instinct is to go to him immediately, pray by his bedside for some form of mercy that you can feel won’t come. But instead, you do something else. He won’t be conscious, anyway, likely won’t be in any state to even know you’re there for days, and for once, there’s something concrete you can do for him. You can make certain he’s never again in a situation like he was, you can be there with him. You can protect him.

What good is prayer, when you can offer something concrete?

Perhaps this is the sign you had been hoping for years and years ago, only you hope it hasn’t come too late.

If there is one thing that you’ve always valued above the faith you were gifted with, the desire to save others, and do even an ounce of good, it is your brother’s life. And if protecting that means abandoning your flock, abandoning your grace, your mercy, then so be it. Some things are more important than saving your own soul, after all.

Two weeks later, you finally show up to your brother’s bedside, letter of acceptance to the New Orleans Auror Academy in hand, with the full intention of being finished by the time he’s healed and ready to go back into the field, this time with you by his side.

Blessed are the pure of heart, for they shall see God.

It was long ago that you stopped believing in purity of heart as more than an abstract concept, an unattainable goal to strive for surrounded by so much sin, and the world was out to prove you right, it seems.

For a while, you try to do both, all while spending as much time with your brother as you can. Moving back and forth between the academy and your parish in Kentucky, still saying mass on Sundays, coming in to help with meetings and give confessions in between trainings and classes. It’s not as if you’re particularly interested in making friends with any of your classmates, who are nearly all at least fifteen, if not twenty years younger than you, anyway.

You try, at least at first, to pass some of your knowledge onto them. After all, that’s always been your calling in life, spreading the Word, saving the souls of those who are lost. But you see quickly enough that you’ve been living in a pleasant little bubble in which your thoughts, your religion is taken seriously, believed. Here, you receive laughs, eyes rolling, strange looks. You receive stories about how they’ve been hurt by beliefs like yours, how they could never accept something that believes suffering can elevate the soul.

There are arguments that make you feel a lot like you’re a teenager again, pointless arguments with those who wish to remain Godless. Between that, and the training, less time is spent going home, less time for the ones you promised to watch over and steer on the right path.

And then one day, without any real ceremony, you stop going back.

You pray and you pray and you pray and you realize, you cannot be both. You can’t shepherd a flock you can’t give the time to, you can’t preach while focused on saving only one soul.

And so you will be a martyr.

Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called children of God.

You become a peacemaker, if that’s what you can call it.

The work is dull and tedious, not the sort of saving you’ve ever been interested in, but you finish your time as a student once again, and easily enough find your way onto your brother’s squad. Even if you haven’t worn the collar in more than a year, there’s still a certain amount of respect that comes with the past you have, even if they don’t quite seem to understand why you gave that life up.

Or at least there’s respect from some people.

The first day on the squad, the first day back for him, the first day for you, he looks at you, with a smile that takes you back to when you were just a boy, and he says, “Just like old times, right?”

And you smile back, because it is.

But the smile doesn’t last long. You try, again, to offer your own sort of salvation to the members of your new congregation. You offer peace, you offer prayer, you offer your own soul for theirs. And yet no one seems to want it.

And if they don’t want what you have to offer, what’s the point in giving a part of yourself at all?

Something breaks in you, as time goes on. A slow decay that you realize has been happening for years, a decay you hid from even yourself behind fiery sermons and harsh penance, devoted pray with your flock and deep confession to your fellow priests. But none of that can hide the realization that you’re not good.

Camden is not good.

The one thing that kept you good is gone, abandoned for the sake of the one life you care about above your own, and now you’re left with the dregs.

You still pray, every night, every morning, every moment you feel that darkness creeping up, but it feels a whole lot like your prayers are falling on deaf ears.

My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?

Because you couldn’t forsake your brother, and so you’ve forsaken your own salvation. It’s only fair. Nothing is free.

At least it feels worth it, when you go out into the field with him, when you watch over him, keep him from trying to sacrifice himself again for someone who would never show him the same mercy.

At least your soul is being put to good work.

Blessed are those who are persecuted for the sake of righteousness, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

You have to wonder, though, does it still count, if the persecution is your own?

This is a persecution you chose, after all. There was no need to abandon your flock, to leave behind the cloth and fight against a sea of troubles that was meant to be for your brother, not you. You just want to do good, to be good. Both of you do, only, he’s succeeded. You watch him, and you see so clearly just how good he is, how he helps so many. And you’ve failed. You couldn’t even keep him safe, and you didn’t realize your prayers weren’t enough until it was much too late.

Can you still be a martyr, if it is your own thoughts that throw the stones, heat the grill?

You revel in the feeling of the collars around your neck, too tight, nearly choking, making it just hard enough to breathe that you’re constantly reminded of your own mortality, your own mistakes. Tighter than the white collar you gave up years ago, but just as oppressive, in a new way. You’re guilty, after all, of leaving so many behind, giving up their salvation, as well as your own. And all there is now is to try to bear the shame, to give back even an ounce of that salvation in any way you can.

If you bear some of that sin on your body, perhaps it takes away the sin of all the lost confessions you never heard, the sermons you never finished, the flock you left alone. Letting yourself feel the pain in your heart for your faith must be holy.

The solution comes in a dream, the first a Sacred Heart burning on your chest, a divine message that only seems to confirm your suspicions, your guilt is productive, a representation of your love for the lost, the broken, those you left behind; a divine love of humanity, of mortality. And so when you wake, you pull out your wand and give yourself the heart you were gifted in the dream.

Then come the arrows, just as Saint Sebastian, a flame gifted, for Joan of Arc, the reverse crucifix, Saint Peter, and most recently eyes resting in the palm of your hand, as Saint Lucy. And it’s a blessing to finally feel some sense of peace, knowing you’re doing good, even if you yourself have never been quite as good as you prayed you were.

Maybe you can save souls and save your brother, all at once.

There are times, of course, when you think of leaving, after a particularly hard case, or rough day, you think of finding a new parish, and going back to your old life. Those thoughts rarely stay once you think of your brother, though. There was never another purpose for you. It’s all worth it if you have even a chance of keeping him from finding more harm, after all the real good he’s done in his life.

After all, you would gladly follow him to hell and back if it meant you’d both survive.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gonna Analyze all the Devilman Media

You can totally ignore this, I'm just comparing elements I liked and didn't like. The good news is they all contain both, so it's an even playing field!

Devilman Manga (1972):

Alright this is the original core story, and I really adore Mr. Nagai for writing such an intense and powerful story. EDIT: Apparently Ryou wasn't even supposed to be Satan and was supposed to DIE and THEN Devilman was born, so all the foreshadowing/plot twist was total bullshit and frankly that really crushed me. I respect Mr. Nagai in a different way now, but..... man, I really liked it better as this huge intense plot....

Akira was portrayed as a crybaby in the manga, so I'm happy to see that change in character! But unfortunately once he became a demon he lost that intense compassion and became a sort of basic hero in my opinion, so that was a little disappointing.

I liked how Mr. Nagai also mentioned real life problems. There was an an entire page of humans accusing each other of being the next to become demons, and it was exactly as you expected; choosing eachother based on evil hate that had nothing to do with actually becoming demons. I liked how Nagai had humans react, clearly portraying how evil humanity was, and exactly what would happen if something like this happened in the real world. I fuckin love super heroes, but goddammit humanity would never come together as efficiently as we (and Akira) hope.

I LOVED how Akira realized humans weren't worth saving. I loved how he saw that humans were destroying each other and were just as bad as demons, and that Akira literally said he was ashamed to be trying to save them, and that there was truly nothing in the world left to save. I'm always a sucker for a hardcore optimistic character getting shot the fuck down, so that's also a factor, eheh.

I disliked Miki. She was funny as hell, but she was an absolute fuckin useless character. She didn't care for Akira until he demoned out, so she only genuinely liked him for being so "manly". She could have been cut clean out and it wouldn't have changed the story. I did like how she fought back, though. Less Good Little Christian Girl, and more able to stand her own ground. She fought literally to death.

I disliked that Akira acted as though she was so great, she was so important, but we never had any basis for this because of her lack of character, and therefore were going off of Akira ~~suddenly~~ caring about her deeply when everyone else was dead.

I disliked Jinmen's victim was some random girl that suddenly showed up and supposedly meant a lot to Akira. We never knew her because she died on the train two fuckin pages later, and again, had to take Akira's word for how much she mattered.

I LOVED how Satan repented, apologizing to Akira for doing exactly what God had done to the demons in his rage, trying to defend the demons against God. I didn’t like that Akira’s death was so lackluster. His last words are “the moon...”, but you never see how he died. And when Satan reacts, he’s clearly sad, but seems... still too calm about it. But it could simply be the outdated manga style.

Devilman TV Series (1972):

Sorry folks it just doesn't follow the actual story at all and I can't say I liked it all that much? Basically just Miki being a damsel in distress and Amon, who is possessing Akira and falls in love with her, rescuing her and fending off demons who are mad he's protecting and staying with humans.

BUT it gave us Devilman No Uta and for that I am forever grateful. Plus it was entertaining, so I mean!

Devilman OVA (1987-1996)

Went pretty much by the manga, so the same factors kind of stick for a bit. With Jinmen, however, it was his mom, who was killed in the ice caverns they resussitated the demons from. I LOVE JINMEN. He is my favorite Devilman villain, because of this scene. He taunts Akira because the faces are still alive, and Akira would be the one to kill them. Akira must fight his own morals to know that they are suffering.

It is a tragic scene when Akira is crying naked after he defeats Jinmen because of what he had to do. No other Devilman media has given such a powerful potrayal.

I didn't like Miki's weird interactions, they made her out to be in love with Akira but Akira... not really like her again...? It was a little more weird and perverted in this version on both sides.

Amon: Apocalypse of Devilman

This is heavily based on Amon: Darkside of Devilman but goes on a totally different tangent! I'm really gay for Amon so this was a treat to see big red fuzzy demon boy (who looked arguably cooler in the anime than the manga, whoops)

It was still kind of random and you really would have to know everything else about Devilman to een follow this one, because the entire thing was the first chapter of DOD, revolving around Akira being trapped in Amon.

I LOVED when Akira saw Miki dead HE FUCKIN OBLITERATED THE ATTACKERS BY HAND and the scene cuts to him just dropping a body part into a fuckin lake of blood surrounding him. It was powerful and angry and raw emotion, and it made Miki's death more powerful to the viewer in this version, because you saw just how angry Akira was over it.

That being said, I didn't like how Miki and Akira's relationship was in this, with Akira seeing a weird in-school dream with Miki, and him telling her it was all his fault she was dead. She kisses him and idk something about it wakes him up? It was powerful but random, because it really insinuated there was this whole love story that wasn't actually there..?? I think everyone remaking Devilman just really wanted Akira and Miki to be a bigger thing than it was...?

The Amon vs Akira fight scene was wayy extra too, he legit just kept fucking punching him and there was no build up AND THEN IT CUT TO AMON BEING DEFEATED that was dumb af not gonna lie

Again, only loosely based on DOD so I really dunno what they were going for in this.

Amon: Darkside Of Devilman:

Arguably my FAVORITE Devilman media, even if it’s more of a “behind the scenes” edition. I really liked the fact it hyper focused on Amon and Satan's past, building their characters and giving you a soft spot for Satan. It also painted angels as not "good" but just obsessed with purity, and all in all, makes you question God's authority.

It made me fall head over heels for Silene, who I unfortunately did not care much for at all up until this point. It also portrays demons as just as emotional as humans, and is very important for the reader to understand demons aren't the sinister barbarians they were painted as in the other versions by humans.

The only downfall I suppose was a kind of confusing main antagonist. And maybe that was deliberate, so I won't go too much into that.

I LOVED Satan actively defending Akira against Amon, and admitting again his love for Akira “Do you love someone so much you would destroy the world for them?” This version of Satan is my favorite. A lot of it is him sulking over Akira not loving him back, and being tender towards Akira. As mentioned, it really expands him as a character.

Devilman Crybaby:

Aaaandd last but definitely not least!

I liked how Akira was portrayed as a tiny baby child who ran fuckin, track and field and no one gave a damn about him. Even in the small amount of time, he was portrayed as a sweet kid who would defend any of his friends at the blink of an eye. He's such a good boy in every version, but this version of Baby Akira takes the bait for #glowup but remaining pure.

I liked how Akira was still a big fat crybaby, crying for others and seeing straight through emotion lies. He was still a good boy despite being all demoned out, and stayed confident in humanity till the very end, which I adored because it made you feel it 10 times harder when you saw everything be ripped away from Akira and watched him crumble, but hold strong.

I LOVED how Miki was his friend before everything, and that throughout she was constantly reassuring Akira she was there for him. It made her all the more important to the viewer, because we fell in love with her! Not to mention her innocence and naïevity but strong belief in humanity made you WANT to root for her. She was so genuine.

I liked how Miko was a huge character in this, seeing as the only other time was in DOD and AOD, which she was the boob-hole chick they showed in the very end of Crybaby. I liked how they redesigned her so majorly, bringing light and giving you yet another character to fall in love with even if you weren't always sure of her intentions.

I LOVED Taro's death in this. It was the most powerful, and the most heartbreaking. I wasn't sure if you were supposed to like Akira's parents personably, but I didn't because they had a child and proceeded to travel the world and leave him with family friends, hardly knowing him aside from occasional visits. Akira's finded fucking memory with his mother was her teaching him how to TIE HIS SHOES!

It did in fact make Jinmen a slightly more powerful villain, dealing with the possession of his father and the murder of his mother, however I was disappointed Jinmen didn't have that "they're still alive... i didn't kill them, you are!" Factor to him as he always did. It really ruined the

It was still hard, but easier for the viewer to not care, seeing as they were telling Akira they were already dead anyway. Jinmen was also a slightly bigger feat in the other ones because of this.

I hated all the sex scenes. Unnecessary and uncomfortable, the first 3 episodes make you want to turn it off. The first episode I was in love, but the second, I began questioning if I should keep watching if this anime was always gonna be a sex fest. Not because I’m such a prude, but jesus christ we get it already.

It was in no other media, and I really think it was just for a weird sort of "sex and gore" shock value. It was offputting for Akira, kicking his sex drive into high gear and almost portraying him as a creep to Miki, AND RAPING SILENE?? She was in fact asking for it, and she was evil, but that was uncalled for and once again not based off any other Devilman media.

I HATED Silene's arc, in no other media was she in love with Amon, in no other media did she fuck Akira. I legit skipped the scene because I didn't like the fact they randomly through more and unecessary porn, especially between a 17 y/o and a clearly much older demon who was in love with his demon not him ??? which was hardly a canon fact, but rather, a joke other Devilman media played off of insinuating that’s why she was angry at Akira. It really put a damper on Silene as a character too, you saw her as this big pervert instead of just absolutely hating Amon for no clear reason as she always had in the past.

I always love Kaim and Silene's story, but I liked how Akira actively pointed out to Ryo that they had been in love, and had felt love. This was a great refefence to Ryo and Akira towards each other, but also a good character build.

I liked Miki’s death in this one. Really gripping and tragic and close to her original death. I also loved Akira’s choked sobs when he saw her head on a stick. That hurt.

I understand a hero to the end is tragic in and of itself, but I much prefer Akira losing his faith in humanity. I didn’t like “they were frightened, Ryo!” But I did like Akira saying he wanted to cry for Satan, but couldn’t.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

character name(s)/alias/etc: sirius black.

character age and date of birth: 35 when he died, it’s complicated. november 3rd, year 76.

character's pronouns/gender identity/romantic & sexual identity: they/them or he/him, non binary, identifies as bisexual & biromantic but is more on the grey side of things and tends not to develop romantic feelings for a person until after sex, romantic feelings are pretty rare for sirius. also identifies as polyamorous.

character faceclaim: damiano david.

oc or canon + which fandom affiliated with: canon, harry potter/magical universe.

currently located: grimmauld place in kirington, albion but he also has a much smaller home outside the main city he spends most of his time at since grimmauld place belongs to harry.

moral alignment + people/groups etc they are aligned to: chaotic good through and through. sirius has always had pretty intense, personal moral codes he follows in life. so much so, that he doesn’t tend to trust or even tolerate those that don’t align to his views. in that respect, he can be pretty quick to judgement and disregarding someone. he has a huge superiority complex in spite of his self loathing tendencies, and stands pretty strong on his morals. though, given his history, he’s not the same kid he was. he understands better now that good and bad are shades of grey, that everyone has potential for it all and it’s not as black and white as he once thought, but it’s still difficult to let that way of thinking go entirely and he’s prone to falling back into those habits. sirius remains aligned to groups that fight for good, and while he doesn’t by any means support any kind of government groups, he’s all for the underground fighters-- like the order were. he’s aligned to harry, specifically, and to his god son’s desire to reshape the magical political landscape in albion.