#gavroche: the gamin of paris

Text

Below is the view which made me aware of the silly book above.

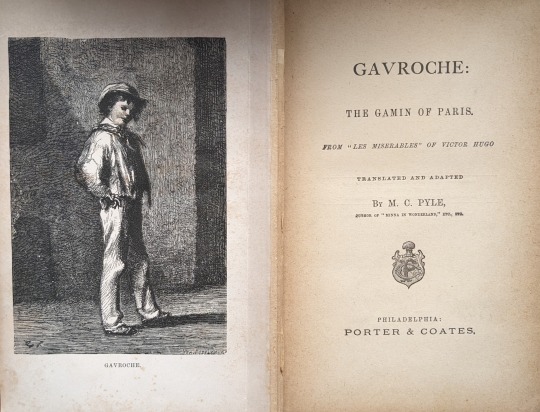

Gavroche: The Gamin of Paris. From “Les Miserables” of Victor Hugo. Translated and adapted by M. C. Pyle. Philadelphia: Porter & Coates. Chicago: W. B. Keen & Cooke.

Such a book, among the inanities that flood the reviewer, comes to him like a fresh flower or some rare rosebud tossed up out of driftwood. Poor little Gavroche! Noble Jean Valjean! What heart has not grown tender in reading this beautiful episode of their lives in that garden of episodes, “Les Miserables.”

Who but loves that wretched little Gavroche, always ragged, sometimes starving, but always bright, ready with a song, a laugh, or a jest, who, when he shivers, shivers gayly, and, when he steals, makes us glad he steals successfully; who drifts forlornly through his guttered career, without father, or mother, or any love that he knows, and yet feels within his unloved little heart a spark of the Divine love, a feeling for his race, restless, helpful, budding out in kind deeds, and little self sacrifices; wonderful in his vagabond-life as a lily blooming in filth and slime!

One feels his own humanity inspired by the paternal solicitude of the little fellow, stealing, begging, filching, working hard and honestly when the chance is given to provide for his little family, — two little waifs whom he finds helpless in the maze of Paris, and shelters under his own unsheltered wing, to find them afterwards to be his own brothers.

The little hero becomes a tiny soldier of the barricades, “a fly on the wheel of the Revolution,” a Napoleon in rags, giving a hint here, lending a hand there; a spy now, and a savior of the barricade anon; handling a musket much larger than himself; and when the Republicans were failing for want of ammunition, is out in the street, between the barricade and its assailants, exposed to their bullets, filling a hamper with the cartridges of the soldiers dead in the street, crawling from one body to another, writhing, gliding hither and thither, emptying the cartridge-boxes as a monkey opens nuts, and, while doing it, is shot!

Whose heart does not fall with him? As Jean Valjean carries the dear, little wounded fellow in his arms, through the sewers, to his home, he carries us with him; and when, at the end, we find Gavroche and Jean Valjean, and the family— his two waif brothers — all united, happy, and secure, in Clairvue, on the shores of the great, blue, bloodless sea, far from perils, we are glad, and thank God for the humanity of the story, which is true, and for the poetry of it, which is true and, more than all, for the truth that we have streets of our own with little Gavroches in them, to whom it is not too late for us to play Jean Valjean.

Source: the Chicago Daily Tribune, 20 December 1872

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

I know I just said I didn't want to just be complaining about everything so I'll try to word this in a more constructive way asdfghjkl

It's hard to be an Eponine fan in a world where the musical -and On My Own specifically- is sooooo mainstream. Because imo as much as On My Own itself is kind of a half-decent, if simplified, encapsulation of Eponine's struggle with her love for Marius if you analise the lyrics in isolation, the musical as a whole, her role in the narrative as the unrequited love diva (I'm also simplifying here. I don't think this is super fair to the anglo musical, but compared to the book there's no question of how they reworked her into a glamorous 80s diva contralto because musical theatre has usually very strict gender roles), did her so dirty. So dirty. And imo often her character is reduced to her pining in fandom as a result. And I don't like that, personally.

I love that girl so much. I love that she is just young enough to still be a child but adult enough to be aware of her social role. She has one foot in the gamin life and one foot in the adult world. I love the tragedy that is the fact that she likes the beauty and pomp of high society girls and wish she could have silk shoes but knowing she can't.

And also being super resigned to her class despite it, she doesn't believe she ever will have any of that. She resents that too, somewhat. The tragedy of her knowing that she couldn't be with Marius because of his social class and her accepting that (angrily? sadly?). I love her self-banishment as his guard dog because of this. I love her drunk sailor voice. I love how manipulative she is and that she isn't Marius's friend at all. He's just her one neighbor who wasn't a total asshole one time. He was, later. But not at first. And she can't be in his head and know he thinks she's kinda despicable because crime because Marius is a judgemental little shithead.

And Eponine isn't an idealist, she's resigned to her position. I understand why she gets paired with grantaire in fics but her canon narrative parallel is Javert, they both believe they are excluded from society from their outcast position and so become the watchdogs for it. Eponine a kind of guardian (in her own words a devil, not an angel) and Javert the same. That's why he's the one person who sees her in the barricade, he's the same as her. Marius saw her but that's only cause he had a use for her in that moment, as soon as she didn't he forgot all about it.

I think also Gavroche, with his ability to be kind of a figure above the narrative, with his gamin skills of being almost omnipresent is something Eponine used to have, but with her age she's starting to lose that. She's starting to grown old enough that she's required to be IN the world and not supercede it. Gavroche is also almost there, if he had been allowed to grow up he would've lost that ability too. They both inhabit this sort of magical surreal world superimposed on our own.

A lot of Les Mis and Notre Dame de Paris can be kinda described as magical realism, I would go so far as calling them urban fantasy. And characters like Babet, Thenardier sometimes, Gavroche, Eponine (and Javert sometimes as well) are inhabiting this magically charged layer. This reality that's imposed Over the real world.

Talking about that One Series Of Wizard Books is a bit passé rn so uh. Doctor Who. Particularly the initial New Who seasons before they got that huge budget. That's a good parallel to what I'm getting at. The real world is still the same but there are certain characters that inhabit this mystical overlayer and are able to transverse from one to the other (Javert can't really because he is stuck forever outside and the second he understands that you CAN'T be an unbiased outsider who only enforces the norm without participating he freaks out and literally dies about it). Eponine is right in the eye of the storm tho. She manipulates reality to get her way, to die with Marius, because that's as close as she can get to being with him. And she manipulates reality to protect him too. Contradictions be damned. She has many contradictory feelings that make her complex and cool and an awesome character whom I love and wish would stop being reduced to the glamurous mysical theatre role with a single black stain on her face and a beautiful actor and a big unrequited love song about a random boy (whose personality was also changed for the musical and I argue is probably the character that was most fucked up by it in the public perception because he's such an weird little self-insert of an even weirder guy. But I get it, the musical is long enough as it is).

Anyway, I wish eponine could be more of a mongrel, a little gremlin. A little rat child that's just beginning to grow into an adult and is self aware of her role in the narrative society. She's a teenage girl which already sucks to go through when you're not constantly starving and cold and being forced by your father to work and do con jobs. Marius is the object she attaches herself to, but it could've been literally anything. Javert did that with the social order, he protects and guards it. She just chose Some Guy instead. Which, we all have that one friend who does that too. Like girl you're too good for him. Come on let's get you sone ice cream. And clean clothes and a roof. Literally anything. Bread.

I think if Eponine had a roof over her head and like, food on the regular she would forget Marius exists. Same as Cosette if she had moved to England. Like he'd be that one intense crush they had as teenagers. Can't say the same for him tho. He would hold onto that for the rest of time.

#rambling#idk. anyone has any thoughts?#if you disagree with me. go right ahead and say your piece! I'm open to being contradicted here#I'm no authority asdfghkkflsbsg like I'm just some rando on the internet with a les mis blog#long post

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

There are numerous aspects in this somber chapter that perplex me. I understand why Gavroche ventured outside the barricade with a large basket - the insurgents were running low on bullets, and Fannicot's fallen men, with their full cartridge-boxes, were awaiting someone to empty them. I comprehend his initial actions as he embarked on his sortie: cautious, quiet, and crawling, taking advantage of the smoke shrouding the street while the insurgents maintained silence to avoid drawing attention to Gavroche. However, what transpires thereafter eludes my understanding. Why did he not retreat before approaching too close to the enemy line? Why did he not retreat under the cover of the smoke? Why did he choose to stand up when discovered? Was it due to his youthful inability to assess risks? Was it his gamine nature that rendered him unafraid, unable to resist the urge to taunt and confront his adversaries? Or was it a mature realization that he was fated to die that day regardless, even if he returned safely?

In a strange way Hugo brings parallels with Éponine. At one point, he likened her to fantastical creatures, ranging from fairy and angel to goblin, ghoul, and devil. Here, Gavroche, too, is compared to a 'strange gamin-fairy' and an 'invulnerable dwarf.' Both arrived at the barricade with a seemingly suicidal purpose - more explicit in Éponine's case and less overt in Gavroche's.

In an earlier chapter discussing gamins, Hugo mentioned their obliviousness to the existence of Voltaire and Rousseau. Previously, I suggested that Gavroche was aware of them, citing his final song. Yet now I am inclined to think that perhaps he sang the song without fully grasping the significance of the names mentioned. I am not sure.

The little sparrow, the embodiment of Paris, is dead. His song remained unfinished…

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

The weather that Hugo describes feels very indicative of the mood in Paris, with the winds of cholera brewing a storm of popular anger. With respect to Gavroche, though, this is immediately relevant in that it makes him cold (and Magnon’s children are freezing, too). The cold is especially bad since, like his sister, he often goes several days without eating and wears rags.

Watching Gavroche take charge is so cute! He tries to seem so confident in front of the younger kids (saying that having nowhere to sleep isn't a big problem, for instance) even though he’s also suffering. As we saw with Mabeuf earlier, he’s genuinely generous, too. Not only is he helping these children, but he gives his scarf to a poorly clothed girl, demonstrating his general kindness and good nature. The girl’s lack of a response reminds me of the line from before about the Thénardier children not noticing their new siblings because they were too impoverished to be aware of their surroundings. It’s a sad parallel, but it reflects well on Gavroche’s character. And his kindness and confidence work! The kids are soon happier! They’re all still in a horrible situation, but he’s lifted their spirits.

His exchange with Montparnasse is hilarious. He has no respect for him whatsoever. On the one hand, that lack of respect is one of the many gamin traits Hugo listed that Gavroche embodies. On the other, though, it shows his casual familiarity with crime. Montparnasse isn’t scary to Gavroche because he already knows his world, using the same slang and recognizing the people Montparnasse talks about. As for Montparnasse, his ease around Gavroche is a reminder of where he came from. He was a gamin, too, so Gavroche is equally familiar to him. It’s funny to read, but it does indicate that Montparnasse’s life is one of the most likely options for Gavroche’s future if he manages to age out of being a gamin. That Montparnasse seems cool to the young children probably isn’t a good sign for gamins more broadly, either, as he may seem appealing to children with so few options even though he’s horrible.

(And he’s not even that good at crime!)

I love how he warns Gavroche about the officer, though! It’s a kind gesture, and it’s clever! According to Donougher, in the French, there’s assonance with the syllable ���deeg” in everything he says (“je te dis,” “ma digue,” “si vous me prodiguez dix gros sous,” “d’y goupiner,” “mardi gras”).

And we’ve reached the heavily symbolic elephant! Gavroche literally lives in the ruins of empire. Hugo says we can’t know what it means, so in that sense, we should be careful not to overestimate how clear its meanings are, but that he explicitly states that it’s difficult to know also pushes us to search for symbols in it. And it’s not all bad! It’s grand and majestic (maybe even “great!”), like Napoleon I was to Hugo. But it’s also a carcass that’s being worn away by time, and it’s unpleasant to look at for “respectable” people in particular (much like its gamin inhabitants are ignored and looked down on).

And it’s also been replaced. Hugo frames it as an inevitable change like that of classes, drawing on 19th-century theories of the “natural development” of societies to explain why the elephant’s era ended. The emphasis on ideas over power feels like an indirect criticism of the Napoleons, with the idea of a republic being the progress that their dictatorial power can’t counter.

That aspect, in general, feels the most significant. Napoleon did some good; his elephant is now a shelter for Gavroche, and his rule inspired many in France by giving them hope that they, too, could advance socially and that their country would be influential. But this is a hollow sort of “good.” The elephant is a shelter, but only because there are homeless children who need it (and, as Hugo points out, it was a real need; the fiction here is based on a real case). France’s empire couldn’t last because it was against republican principles in France and across Europe. If the elephant was in such a bad state so soon after Napoleon I, then, imagine how much worse it would be to bring its idea back with Napoleon III!

Hugo even says that the good of the elephant came from God, not Napoleon!

Another note: the elephant is for someone that other doors are closed to, once again illustrating the importance of open doors. Gavroche wouldn’t need the elephant if he weren’t a social outcast. His poverty would not be this desperate if people respected him and helped him.

His use of the wire is very creative! But that it’s all from animal enclosures in the Jardin des Plantes drives home that animals have more than he does (and are given more by society). It’s worse than Valjean not having a place to stay when the dog had a house, in a way, because at least the dog was tied to a family in some way, either as a pet or a work animal; the animals of the Jardin des Plantes are there as a spectacle alone, and it’s for that spectacle that they’re given good quality things. His narration is hilarious, but it’s heartbreaking, too.

41 notes

·

View notes

Note

Are there any crumbs of backstory between Montparnasse and Éponine in your fic that you would like to share or elaborate on? You capture their dynamic so well and it’s so fascinating and entirely canon to me!!!

Hello, thank you for your lovely compliment! It means so much, especially coming from you (I remain in absolute awe of your brilliant writing!)

And— oh boy— this is going to end up quite long, so I apologise... I’m not really giving you crumbs, at this point I feel I’m presenting you with an entire baked loaf of backstory to my fic!

In the summer of 1829 Éponine and Montparnasse's paths cross for the first time, courtesy of an unexpected collaboration between Babet and Thénardier on some inconsequential criminal endeavour. (I’ve taken loose inspiration from details in the novel that possibly allude to there being more history between Thénardier and Babet compared to other Patron-Minette characters, since Babet has a surprising wealth of knowledge about Éponine, Azelma, and Gavroche whereas the other rogues do not).

At this particular point, the Patron-Minette were not yet formally established and remained far from ruling the dregs of Paris. In fact, Babet had only just recruited Montparnasse to serve as an amateur accomplice to his crimes— and this is how he ended up regularly frequenting the Thénardier family’s lodgings in the latter half of that year, and therefore meeting Éponine.

At the time, Montparnasse— being between the ages of 15 and 16— certainly had a much more boyish look compared to his appearance in 1832. Rather than being a polished dandy of the sepulchre, he was still a scrawny, teenage lout who'd only recently been picked up by Babet from the streets and given a sharp knife + a fresh set of clothes. His slick appearance and pomaded, oiled hair was not yet in existence, and instead a messy mop of inky curls hid his bright, springlike eyes.

Éponine too was significantly more youthful in this period. As she navigated through puberty's tumultuous stages, the weariness of spending the last few years steeped in squalor had already etched itself upon her face. However, amidst such hardships, she still was able to retain some of the natural beauty of youth that her circumstances had so cruelly tried to snatch from her. Her skin freckled over in the summer sun, and a warm glint lingered in her dark eyes when she laughed.

Naturally, Éponine was already brimming with an intense yearning for the homely luxuries and comforts she had once had as a little girl at the inn in Montfermeil. As her life plummeted further into the depths of poverty with each passing day, the desire for a better life only burned deeper within. It only seems fitting, then, that when she first crossed paths with Montparnasse that summer, she would be instantly taken to him. Thanks to Babet, Montparnasse was then beginning to scrub up well in nice fashions— gradually transforming his appearance, although without the foppish extravagance that would later be used as his identifier in 1832. He possessed a modest selection of fine but plain garments that enhanced his appearance. And, in 1829, Montparnasse had a much softer, sweeter temperament… seeing as he did not yet have any proper criminal reputation attached to his name.

Throughout the latter half of the year the pair became increasingly close— the way that teenagers do— with each time that they were able to see each other, aka whenever Babet and Thénardier collaborated on a criminal plot. And, on Christmas Eve in 1829, as they stood outside in the snow together, Éponine told Montparnasse that he was easy on the eye— and the pair shared their first kiss together. With Éponine being the first girl to ever tell Montparnasse that he’s handsome, the moment was extremely important for him. As a scraggly, overgrown gamin that had lived on the streets for as long as he could remember up until a few months previous (when Babet purchased him some meagre lodgings), no girl had ever looked at him properly or said any words to this effect until this point.

Not only would this encounter surge Montparnasse’s affections for Éponine— for she’d made him feel desirable— but receiving this compliment, and that kiss, was the spark that made him realise that he was naturally good-looking. And, with this newfound confidence, a familiar tale unfolds. Possessing the knowledge that he is handsome only encouraged him to become more arrogant and cocky… and, well, that’s where all his other girls come in when we get to 1832...

Anyhow, by the time that 1830 rolls around, Montparnasse and Éponine find themselves rarely seeing much of each other. After all, the collaboration between Thénardier and Babet was only temporary, being confined to small-scale schemes. And, with the Patron-Minette now gaining momentum and beginning to establish their formidable reputation it was only natural for Babet’s focus to shift entirely towards conducting greater, large-scale criminal endeavours that did not involve the old innkeeper. During this period, Montparnasse also started his formal induction into the ranks of the gang, beginning to commit murderous crimes and quickly establishing himself as one of the four heads of the group.

The pair thus drifted apart, and their youthful affections for each other were long forgotten.

Things went on in this way until the cusp of 1831, when Thénardier offered both of his daughters to Babet to serve as informal look-outs for the Patron-Minette. He saw it as a way for him to get involved and perhaps even make a profit by occasionally working with the gang. (This occurred around the same time that Thénardier first comes up with the idea of informally soliciting his daughters out to men through his letter scheme also, and he spends the coming months planning and organising his idea).

With Babet and Thénardier partially collaborating again, Montparnasse and Éponine stumble upon one another once more.

Of course, they'd both grown up by then. Since 1829, Éponine had become womanly, and Montparnasse had shed himself of those last remnants of boyhood.

After that fateful kiss in the snow on Christmas Eve, life has only gotten harder for Éponine. In an attempt to appease the Patron-Minette, her father had allowed Babet to take some of her teeth, further diminishing her already worn appearance, and her rags were even more worn than they had been a couple of years ago. By contrast, Montparnasse has only gotten grander in his foppish appearance and notable reputation over the years. Yet, despite such differences, they both yearned for the same thing— attention. Montparnasse revelled in being noticed by the young women on the boulevard who giggled and called him desirable as he passed them, and Éponine—seeking escapism from her miserable life— remained desperate for any affection that she could obtain which made her feel seen.

Therefore, it did not take long for the pair to pick up where they left off in 1829, and by the early months of 1831 their evening flirtations had transgressed into them sleeping together.

Although neither of them would ever openly acknowledge it, the bond forged by their first kiss in 1829 continues to bind them together. It is what draws Montparnasse back to Éponine, even when he later begins enjoying affairs with numerous other grisettes. And, for Éponine, this bond is what compels her to continue indulging in Montparnasse, even as he becomes colder and more cruel than before.

However, the most profound of these invisible threads of unspoken significance that keeps the pair returning to one another is the fact that they were each other's firsts. Éponine admitted this to Montparnasse at the time, but he never voiced the sentiment aloud— nor would he ever confess such a vulnerability to her.

By February 1832 Éponine and Montparnasse are extremely familiar with each other, since they had been rendezvousing in alleyways at night for about a year. However, their relationship— though rooted by a need to feel desired and be seen— is loaded with complicated emotions that persist beneath the surface. While they use each other as a means to fulfil their own wants, seeking solace in the temporary intimacy they share... these odd feelings persist between them; feelings that they are both too stubborn and embarrassed to acknowledge or admit to themselves...

...that was until the Gorbeau ambush failed, and Éponine began lodging with Montparnasse...

—One last point; the pair’s night-time trysts are something they (naïvely) think they’re doing discreetly, but absolutely everyone around them is actually aware of it. Babet, in particular, possesses knowledge of their affair and at least for the moment views it with mostly with approval, for he sees the relationship as something that can entrap Éponine and further entangle her in the Patron-Minette’s criminal operations. Other characters also certainly see corrupt benefits to the pair being an item... but I cannot speak any more on this else I might end up spoiling some future plot points...

#I LOVE being asked questions like this— thank you for letting me release all of the pent up thoughts in my brain#montparnasse#eponine#montparnasse x eponine#les mis fanfic#I did not proofread this— if you see any spelling or grammar mistakes no you didn't#ask response#épines d’une rose

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brickclub 5.1.15 “Gavroche outside”

Brickclub is back and it’s the worst. I don’t know how to analyze this chapter. I don’t WANT to analyze this chapter.

There’s a realistic reading here, of: this is why children shouldn’t be in WAR. He’s brave! He’s so brave! And also, twelve-year-olds don’t understand risk and mortality and shouldn’t be in a war zone!

And reading it there’s this sense of “no dammit don’t go out there” and then “okay, they haven’t seen you yet, you’ve got a few cartridges, come back NOW” and then “okay they’ve SEEN you but they’re not hitting you, run back NOW YOU CAN STILL DO IT” and so on.

And he never does.

But, also, that kind of response feels like a wrong direction to me? Much as I want him to Not, criticizing Gavroche feels very off.

Criticizing the adults is exactly right, though. FUCK these suburban National Guard. We’re reminded they’re from the suburbs several times--which matters, because they don’t have any connection to the people of Paris and don’t mind killing them. That’s no excuse at all for making a game of shooting at a child, but... here we are. We’re told they’re laughing as they do it, because of course they’re laughing as they do it.

And, of course, they don’t have to do this. Gavroche getting the insurgents a few more bullets doesn’t change the outcome of all this. They’re shooting because it’s a sport; unlike the other shooting they’ve been doing, Gavroche can’t hurt them back. They’re shooting at a sparrow, and it won’t do them any good to succeed, it’s just a challenge because he’s so inoffensive and so fast and so small.

Symbolically, what IS this chapter though? I’ve never really known. Gavroche has always been Paris, and right now he’s at his most Paris: the spirit of the gamin incarnate, singing his defiance to cruel and repressive authority, slipping through cracks unscathed that it doesn’t seem like he could possibly manage.

But this book always has an uneasy relationship with it’s own magic system; the magic pervades everything, but we always fall back to reality in the end. For a long, long time we manage to follow the magic rules that make Gavroche invulnerable--and then the magic runs out, and we’re stuck in the realistic ending of all this.

This isn’t fully the end of the magic, or even the end of the magic at the barricade--there’s enough left for OFPD, still.

But it’s the end, I suspect, of a lot of it. We lost a lot of magic with Jean Prouvaire’s death; now we lose most of the rest. The scenes that follow this will be far more brutal than the ones that preceded. Symbolic Paris has been crushed, and the last of our innocence is lost.

If hope comes, when it comes, it will a bright spot in a much bleaker world.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

hey can we talk about trans!gavroche for a second

the thenardiers forcing him to wear fancy dresses as a kid and him hating it but not knowing why and his parents shunning him for it, being taught how to sit still and sew and be a good Lady and being certain that something's off, the family moving to paris and m. thenardier making bby gav the 'sweet little girl' that makes the bourgeois melt and hand over their pocket money, gav finally having enough and running away the second he can

finding a piece of glass on the side of the road and chopping off all his hair, stealing pants drying in a garden and chucking his skirts in the seine, giving himself a new name and introducing himself to the gamins he meets as gavroche

him wandering the streets of paris for days, finally stumbling across the musain and les amis, them taking him in as their little brother and teaching him everything they know, enjolras as a fellow trans guy taking little gav under his wing, less in a big-brother way and more in a strict-but-lovable-uncle way, and showing him how to pass and have people assume he's cis

after the rebellion m. thenardier going around fake-crying about his poor daughters who died on the barricades, a small plaque being built with the names of all who died, thenardier insisting gav's deadname be used, gav's little brothers trying to find him, coming across the plaque but not recognizing the names, and never knowing what happened to their brother

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Éps & Cos Sister Fic

She knew her early childhood was a nightmare. She tried not to linger on it but it really had a bad habit of creeping into her mind. She hadn’t precisely been an unusual case, the poor of France were many and the living conditions of the dregs, ghastly. She knew this but it was still heartbreaking, she had only recently arrived in Paris after spending so many of her formative years in the convent and had become unaccustomed to suffering. Still, there was this grief in her heart that lingered unabated. Giving alms to the poor was one of those gifts in her life that allowed her to feel fulfilled, even if it could only last her a short time. Whatever aid her father had the power to give must make these people’s lives even the slightest bit better. Cosette looked up, she had just walked away from a beggar she had greeted when her sisters crowded either side of her.

“Look how pensive you are, aren’t you just darling?” teased Éponine.

“What’s on your mind?” Azelma replied softly, but she always spoke softly.

Cosette tried a smile but she was sure it came out quite guilty and half-formed, “nothing really,” she tried.

“Pensive indeed,” said Azelma conspiratorially.

“She’s lost in the past again,” Éponine realized, eyes widening. Their father called to them then. He was entering a curtained building to help a woman and her child it seemed. As Cosette spoke to her sisters a young man walked past and saw them.

She was the most beautiful girl he’d ever seen but there was a shout on the street just then and he ran.

Éponine gasped, father was fighting a bunch of men as they left the small building. Then she saw the woman who had followed behind and she felt the air leave her chest as if she had sustained a blow. She grabbed at her sisters’ arms and drew them back. They would not be seen, they could not, not by her or her husband. A policeman barreled into the square shouting for order, as he passed Azlema ripped free from her and ran to Father. She clung to his arm. Éponine could do nothing but hold onto her twin for dear life. She could tell Cosette had put the pieces together as well and was doing her best to hold her composure. They saw as a boy who had been observing the drama attempted to flee the scene. He didn’t make it far before the policeman lifted the gamin up by his lapels. Éponine saw that Cosette looked indignant. As soon as he was set down he ran near their direction so Éponine stopped him.

“Are you alright?” Cosette asked the boy.

“Yeah, the Thénardiers might get it this time though. Not that I care 'bout my no-good parents.” he sounded so flippant but Éponine’s world began careening further.

“What is your name” she demanded.

He scowled but replied “Gavroche”.

Cosette realized then that this was the baby boy she used to take care of as a child; she felt slightly sick. She looked up then to see the policeman, Javert, turn away from her father. Even if their father had never said so outright, all three girls knew he was wary of lawmen and had some complicated past. It broke her heart to see him so anxious, not unlike a trapped animal. She locked eyes with Azelma and motioned that they should go. They could get back home just fine she indicated, whether or not that was strictly true. They had developed some communicative gestures as adolescents that they still were able to use and adapt. Azelma bit her lip but nodded. She asked when they would be home and Éponine replied that they would be home by midnight. Azelma whispered to their father and he seemed almost to say no but then they turned and were gone.

“Gavroche” Cosette invoked, getting his attention. “How well do you know the city?”

“It’s me personal theatre. I run everything, I can get anywhere” he declared.

Cosette looked Éponine in the eye and grinned. Éponine realized then that she was at the mercy of her sister’s mischievous side.

“Would you show us around then?” she cajoled.

Gavroche did show them around, sort of. It was more like they followed as he went on about his day, him occasionally providing commentary. It was fun though, magical even, Éponine wasn’t sure she had ever been this free with Cosette. They were chatting and laughing and running. Their lives at Petit-Picpus had been blessed but also so very contained. There was so little physicality to it, an hour to play a day? But here, in the busy streets, even if they did look respectable and clean they could just, roam. It was so different. Father was a very contained and secretive person and dear Zelma was so passive, she had few opinions and never fought. Cos and she had pretended to be twin sisters during their time at the convent but, at some point, it stopped being an act to keep them safe and just became their reality. Their faces were quite different but they had the same chestnut hair and most people didn’t choose to question it further. Cosette had a wonderful wicked streak, mischievous and raucous for brief moments before remembering her manners and upbringing and returning within herself and becoming quiet and thoughtful. Éponine loved her sister and seeing this freedom grace her she felt alive. So far as she knew, Éponine remembered their childhood better, more vividly than Cosette. She remembered how Mme. Thénardier had pitted them against one another and how cruel she had been in turn. She had a certain lingering guilt about that so she couldn’t help doing whatever she could to make Cosette smile. They had entered an, evidently, wealthier part of the city when Gavroche was flagged down by a group of gamin rushing at him.

Cosette had been so engrossed in the sights of the city and her delight in seeing so many people and interactions and life she hadn’t noticed how late it had gotten, their father would be so fretful. “Éponine, it’s nearly sundown, we really must head home. Gavroche, can you escort us?” Gavroche barely looked at her, just grabbed her hand and started running. Éponine caught up with them moments later and Cosette grabbed her hand. The bustle on the streets paired with the sound of her pounding heart was almost deafening. Everyone was starting to talk. “Éps, are we going the right way?” she shouted.

“I don’t know, I don’t remember” she called back. As dire as this should perhaps have seemed they were both smiling and she couldn’t stifle a giggle even with how out of breath she was quickly becoming from running. 'Ponine burst out laughing then too. They weren’t running too long, fortunately. They seemed to have arrived where Gavroche intended them. They appeared to be in front of some sort of cafe, the name Musain painted on its front. It was emitting bright, warm light and excited chattering and laughing and perhaps some music.

Éponine wasn’t sure this was a good idea, as restraining as it sometimes felt they were still proper young ladies, whatever sort of place this was they almost certainly had no business being within it. Gavroche split with them then, running into the building. She may have had reservations but she also wasn’t about to lose their only guide. She ran after him now dragging Cosette with her. As soon as she started climbing the stairs she realized she had made a mistake. The men in this place were preparing to revolt, they were looking for a revolution. Gavroche started shouting for attention when they were halfway up the steps. Silence befell when they were at the top and Gavroche proclaimed the death of General Lamarque. Cosette gasped and Éponine realized that must have been why the children had accosted Gavroche.

Cosette watched from beside the stairs with Éponine as the men all started talking over one another again. Then a young-looking blonde man raised up his hand and the room went quiet again. He looked momentarily crestfallen but he pushed forward, “Lamarque is dead.” A startling determination came forth on his face then and he shook his head, “Lamarque, his death is the sign we await,” a rallying cry was building up in him and it infected her. She knew that much was broken in this country, in her country. She was a newcomer to Paris but she was aware of the significance of Lamarque, his name was a buzz in the street, an ever-present whisper on the wind. His death would be a tragedy to the powerless of this place. And these men, though many were well dressed and likely from well-to-do families, seemed intent to do whatever it took to bring justice to the people. The apparent leader spoke on though, they planned to use the general’s funeral to stage a protest. Most of the men looked fully enraptured, there was a man on either side of the leader, one tall and serious, the other round and jovial. There were three men talking in the back, one drinking tremendously, staring at the leader, the other two looking vaguely concerned. Many other men were talking or listening, hearts nearly beating as one.

The round man split from the leader’s side then and approached them, “I feel I recognize the pair of you, have we met?” he asked with a broad smile.

Cosette held polite eye contact, “I’m afraid I think not.”

The man looked closer at Éponine’s face then and a spark of recognition alit his eyes “The sisters Lanoire! I remember; the four of you used to sit for hours in the Luxembourg. A friend and I saw you often on strolls, he is not here tonight. You have both grown quite lovely.”

Cosette blushed faintly at having been remembered as such. Éponine picked up the conversation from there, “Thank you for saying so, Monsieur…”

“Courfeyrac, you can just call me Courfeyrac. But what brings you here this night? Were you lost?” His eyes were kind but Cosette was also wary of outsiders.

“We were just walking with Gavroche, he brought us here.”

He seemed to contemplate momentarily before deciding “Seeing as you are friends with little Gav, would you like to stay to observe the meeting? No one here will give you any trouble I can assure you.”

Éponine was wary, she sensed true kindness within this man but how could she truly trust the other men here? She looked to Cosette and saw the yearning plain on her face. “Are you sure Cos?” She nodded and Éponine sighed. She looked Monsieur Courfeyrac in the eye and said “It would be our pleasure.” Cosette beamed and the Monsieur escorted them towards an ill-dressed man with red hair. Éponine let Cosette choose most of her dresses after she had a brief spell of studying all the fashion plates she could find and dedicating herself t understanding the day’s fashions some weeks ago, but even she could tell his outfit was disastrous. He turned out to be immensely wonderful though, called Jehan. He wrote poetry in a little leather-bound book. After her time in the convent, Éponine had become a vociferous reader and the man seemed ecstatic to talk with her about poetry and recommend her some poetry collections and political works. He wrote a little list and tore the page out of his book. She was momentarily surprised he would defile the book as such but he smiled and her heart melted. He flipped to another page and peeled a piece of pressed rosemary from the page and folded it within her page. She didn’t know what to do so she asked him another question about one of the essays he had been praising.

Cosette was wonderfully surprised by how fast Éponine engrossed herself in the conversation with Jehan. She was usually so wary of strangers and generally shy but she hardly noticed when Cosette walked away to talk with some of the other men so she counted it as a win. Courfeyrac introduced her to the tall man, Combeferre, and the leader, Enjolras. They were both perfectly lovely but also too busy to really engage with her. Courfeyrac looked across the room, his eyes landed on the three men she had noticed in the back earlier but he decided against it and led her instead to a broad man in a flashy waistcoat. She was surprised realizing how much older he was than the other men she had met but took it in stride. Courfeyrac made the introductions and excused himself to attend to other matters. Somehow emboldened by his sizable stature she decided to be frank and told him how much she appreciated his waistcoat. He preened somewhat and returned the compliment. She explained her recent escapades into the world of fashion after having lived with nuns for so long. He described his red waistcoat in turn and she began to pepper him with questions about politics, inserting her own observations along the way. At one point when the topic of history and other countries came up a man named Feuilly entered the conversation. She drifted between many of the different men, asking questions and posing different perspectives and hypotheticals. Even Enjolras took some time from his planning to speak with her upon prompting by Courfeyrac who had returned to the conversation. Two of the three men from the back of the room also got curious and made their introductions, Bossuet and Joly. She was thoroughly occupied for at the least, two hours. She regularly checked up on Éponine who had decided to remain seated with Jehan.

Éponine had begun to realize how late it was when the drunk man with dark curly hair she had been wary of sat down at the head of the small table between Éponine and Jehan. He whispered something in Jehan’s ear and he giggled.

“Grantaire, don’t be impolite, introduce yourself to the lovely lady,” he laughed. It seemed this Grantaire fellow might not have been as drunk as he should have been considering all she had seen him consume but he spoke clearly if not entirely logically. He ranted about the fruitlessness of attempting the revolution until the blonde leader, Enjolras, sat down across from him and took up the argument. Cosette sat down beside Éponine and smiled at her.

Éponine laughed, “You’re enjoying this entirely too much, aren’t you?”

“So are you,” Cosette tried to tamp down a laugh but it bubbled up out of her. Courfeyrac took the last seat at the table across from her and smiled at them. Grantaire and Enjolras barely noticed them over their debate. Cosette turned in her seat to face Éponine and began pointing out each individual she had spoken to and what they had seemed interested in and what they had discussed. Éponine listened intently as her sister recalled her different conversations. She was intrigued by the variety of temperaments and interests of the group. They all seemed so in sync towards this one goal, excepting Grantaire she supposed. Her body chose that moment to rebel against her mind and she couldn’t stifle a great yawn from emitting. Jehan giggled again and Cosette patted her arm. Gavroche approached them, appearing from nowhere as children like he tended to do.

“It’s quite late now misses. D’you wanted me to walk ye home?”

Cosette took the initiative to reply “That would be absolutely lovely, thank you Gavroche.”

Éponine huffed a little but rose when Cosette prompted. Enjolras and Grantaire seemed too occupied to notice their departure but both Courfeyrac and Jehan rose to wish them well. Courfeyrac played at charm and chivalry and places a kiss on both their hands. Cosette laughed and Éponine couldn’t help roll her eyes. Cosette bid her farewells to the rest of the Amis and Éponine waved to them.

Cosette noticed that unlike Courfeyrac, Jehan had not yet said his goodbyes and returned to the table they had left. He hovered a short distance behind her sister towards the stairs. When she concluded her goodbyes she prompted Gavroche to lead the way and almost made to follow but instead turned to Éponine and Jehan. If her sister trusted him, which she so clearly did, then she also trusted him. She put on a winning smile and asked if he would also like to accompany them. He beamed and agreed immediately, Éponine blushed. She smiled and quickly caught up to Gavroche. Letting Éponine and Jehan trail behind them. Would never forget this day, she could already tell.

I don’t think I described the table layout that well so have this:

J___C

R |____| E

É, Cos

#Les mis#Les miserables#Les miz#cosette fauchelevent#eponine thenardier#Les amis#sooo I’ll finish editing this later when I have time but here ya go#barricade day

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Les Misérables 160/365 -Victor Hugo

151

The gamin loves the city all things of interest and souvenirs. Anyone who goes through Paris sees the group of children free and playing, “this constitutes all the earth to those children. They never venture beyond this. They can no more escape from the Parisian atmosphere than fish can escape from water.”p.374 (they are a product of their environment it’s all they know and they can't escape for anywhere else)

152

Stray children are around an estimated 2609 homeless, a disastrous social system. “All crimes of the man begin in the vagabond of the child.”p.374 In any other city a vagabond child is left for itself in Paris they have an almost intact interior. While it doesn’t diminish the anguish to see fractured families. The monarchy didn’t discourage discarding children, it was in sometimes need of them, so they skimmed the streets. Lois XIV had a fleet and a need of galley slaves, so parliament made as many convicts as possible if a street child was fifteen there he went. (this just reminds me of the American prison industrial complex and how the courts are prejudice against the poor and minorities and how convicted felons aren’t allowed to vote so the politicians that allow this stay in power)

153

The street Arabs in Paris are almost a caste. (yeah that makes sense even the streets have a social order)

154

The police keep an eye on the gamin, in 1830 they cried warnings to each other. The gamin knows all the police and faces of anyone he meets, studying habits. (kid’s got street smarts)

155

The Paris gamin is respectful and insolent, all beliefs are possible to him, he is one that finds amusement because he is unhappy.

156

The gamin today is gone, cured by light, universal education, men make men. Paris is the top of the human race, it accepts everything royally. “All civilizations are there in an abridged form, all barbarians also, Paris would greatly regret it if it had not a guilotine.”p.379 (I think it has some regrets of the guillotine)

157

There is no limit to Paris, it makes law fashion, routine if it’s fit to be stupid the universe it stupid company. Tempered explosions, masterpieces, pedigrees, all forms sublime, though scolding or laughing, Paris shows its teeth, it’s immense and daring, the price of progress and conquests and the prize. “It is necessity, for the sole of the forward march of the human race,”p.380

158

To paint the child is to paint the city, (a country is only as rich as its poorest citizen) suffering and toil, the two faces of man, would you abandon the barefoot and illiterate, can light not penetrate them.

159

Nine years after the second part of the story people noticed a boy on the Boulevard du Temple, he was about twelve, dressed in rags of charity because his parents didn’t love or think of him. He was better off on the street because he was free. Every few months he went back to the Gorbeau hovel, to Madame Bourgon who let out the space which now housed a family with two daughters. While dismissive of him his mother loved his sisters, the boy was called Little Gavroche. Next to the family’s room was one belonging to M. Marius.

BOOK SECOND THE GREAT BOURGEOIS

160

There are a few old inhabitants who remember a man named M. Gillenormand, in 1831 he was a curiosity simply because he was so old. A bourgeois of the eighteenth century, ninety with all his teeth and claimed to be too poor for women. An old man in good health and still threw into passions on subjects and beat people with his cane and had a daughter in her fifties. His philosophy was nature gives specimens of amusing barbarism so civilization can have a little of everything.

NEXT

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Gamin of Paris, an early example of a Les Miserables fix-it fic

I came across Gavroche: The Gamin of Paris by reading a review from 1872 (the year it was published), a review which made me say what the hell?? On the Wikipedia page for Les Miserables Adaptations, Gavroche is listed first among the literary adaptations, with no indication of how wild the review lead me to believe it would be. So I bought a copy off Ebay and read it, which brought me immense amusement and equal parts terror. Now I know we are all used to adaptations of Les Miserables which diverge from the original but I think it's fair to say that this goes beyond adaptation so please enjoy my summary (and below the cut I will put some notes about the author, the publisher, etc.)

The story begins with Gavroche hiding in the bushes at the house of an unnamed old man and his companion Mere Plutarque Mary Anne. From his vantage point, Gavroche sees Montparnasse attempt to rob an old passerby. Yes, Montparnasse has a rose in his mouth and yes he is dressed to the nines. The man gives Montparnasse his purse and a sermon: Hugo’s original rant was 1,118 words, but while this lecture is considerably paired down, the impact…well, as you will see the impact is far greater. When Gavroche later encounters Montparnasse, the young man says of the experience: “Such a sermon – my faith! It has nearly spoiled my taste for business ever since. If you’ll believe me Gavroche, I have some thoughts of turning honest man.”

When Gavroche steals the purse from Montparnasse to give to Mary Anne, the author remarks: “He was rewarded not not [sic] an hour after, by a sixpence given him by a gentleman, whose hat he rescued from a gutter.”

We learn that Gavroche’s mother, Mother Jondrette, has sold her two youngest sons to a woman named Magnon Manon. This Manon (besides being a criminal) is a nurse who bought the boys to replace two boys who died in her care. She then loses the two adopted boys.

One day, while Gavroche is contemplating theft (“we regret to say”), he encounters the two lost children and decides to care for them. Gavroche asks them their names.

“My name is Adolphe, sir,” said the elder boy; “his,” pointing to his brother, “is Gustav.”

“What fine names!” said Gavroche with a shrug, “fit for a crown prince! Well, I shall call you Dolph and Gus.”

Time passes and Gavroche cares for the boys. Things began to look up for him.

Gavroche, with the cares of a family on his hands, found, as it happened – or rather as Providence so ordered – that his condition was no worse but better than before. The scanty food, picked up by chance, as the crumbs and berries of sparrows are, proved more nearly enough for three than it had been for one. Perhaps this was because his new sense of responsibility awoke in him a desire for employment which he had never felt before. All he knew was, that errands fell in his way in a marvelous manner.

Now, by some narrative maneuvering owing to the fact that Gavroche is the main character of this story, events are a bit out of the familiar order and the Gorbeau House ambush arrives 30 chapters later than it would have in the original table of contents. On the night of the ambush (and not after) Gavroche goes to see his parents, whereupon he overhears Montparnasse and Brujon speaking:

“How soon will the crib be ready?” asked Montparnasse.

“Not for an hour yet,” answered the other, a thickset man with a harsh, croaking voice.

“It is only to pluck a pigeon?”

“We may have to pinch it a little to make it sing,” answered the other; sinister words which Gavroche well understood.

Montparnasse moved uneasily. “Do you need me, Brujon?” he asked.

“Not if you are so flush of jobs as not to want a finger in this one,” answered the other, laughing. “There will be enough to share without you.”

“I will be your watch,” said Montparnasse. “You’ll need one.”

“Eponine is on the watch,” said Brujon. “You can keep her company instead of blacking your pretty face.”

It appears Montparnasse can no longer stomach violent crime. Surmising that his family is involved in what is about to take place, Gavroche sneaks into the house and hides in the neighbor’s room. The neighbor is a “poor student” who is not important and not at home.

Looking through a hole in the wall, Gavorche recognizes that the man his father is targetting is the same man who delivered the sermon to Montparnasse. The man, named Jean Valjean, knows Jondrette as “Fabantou” “Faber” and Valjean himself is living under the alias “Leblanc” (I guess “Fauchelevent” was too much for the young American reader.)

Jondrette offers to sell Leblanc a painting, “on which were painted some coarse figures, no doubt a sign-board from some tavern,” but that is not important to the plot. Jondrette reveals that he knows Leblanc is Valjean:

“You remember me now, I see, the man whom you robbed of the child who was a fortune to him – the boy for whose keep I received a sum which sufficed to maintain my family. You are the rogue who sneaked and spied upon me, who complained of me in the courts for ill-treatment of the child, offering to take charge of him yourself till the return of his parents, and getting me three months in prison which were the beginning of my downfall!”

You may be wondering who is this boy? He is also not important to the plot.

Gavroche wants to help Valjean but does not want to go to the police or betray his family. (In some sentences the name “Marius” is here just replaced with “Gavorche.”) Jondrette demands money from Valjean and proposes to dictate a letter to him:

“What shall I write?” asked the prisoner.

“You have a steward?” asked Jondrette.

“Yes.”

“What is his name?”

“Simon.”

Simon is not important either, I just thought I would mention him. Valjean jumps up and seizes a red-hot chisel from the fire, saying:

“The money you demand I could not give you, and if I could, what is held in trust for the unfortunate should not be wasted on the wicked to save my life. It is in your hands. Then take it.”

Valjean throws the chisel out an open window. (There is no Azelma so the window was not broken.) Gavroche has the idea to write a note saying “the beaks are coming” and throws it into the room, causing the assailants to flee through the window. Jondrette says invokes the rule of ladies first and they do NOT fight over who gets out first.

Gavroche frees Valjean (“This is one of Brujon’s knots but whatever he can tie I can untie”) and introduces himself as “Little Gavroche.” Valjean tells Gavroche to come home with him but Gavroche says he must get back to Adolphe and Gustav.

The Jondrette parents are soon arrested and Eponine is taken to “the House of Refuge” but “the police not being omniscient, they could hardly have known of the attempted robbery in the Jondrette garret, as no information was furnished them by the old man who had so nearly been its victim.” Their arrest is due to some unrelated, unmentioned crime.

Gavroche encounters Montparnasse again and Montparnasse enlists him to help break Jondrette out of prison and, as in the original, the father does not even recognize his son. Meanwhile, the boys are still around, getting up to quirky adventures such as this one recounted by Adolphe:

“We went down to the wharves, but they shoved us about so that I was afraid Gustav would get hurt, and was just going to take him away, when only think, a great Englishman who was there stumbled against us, and almost knocked Gustav into the water, so that I cried out quite loud, and then he boxed my ears for bringing Gustav there, and then he gave me a sixpence.”

Now it is time for an insurrection. Why? The author declines to state. It is noted that “no matter how quiet and prosperous the times may appear to be,” revolution may spark at any time and that, besides those with good intentions, there are also “the desperate, the discontented, the criminal, ignoble souls who hope for disorders which offer a chance to plunder.” The author asserts that the majority of people “denounce all disturbances equally, whether their cause be a just or an unjust one. To them all insurrection is the revolt of the dog against the master, worthy to be punished with the whip and the chain: but when the revolutionary effort is successful, when the dog shows itself a lion, they throw up their caps and shout 'Long live the people.' ” (It can be hard to figure out which lines are the author’s own invention and which come from Hugo. This bit about dismissing revolutionaries as dogs was originally applied to the bourgeoisie, not “the great body of citizens.”)

Insurrectionists build a barricade in the Rue St. Denis, before the tavern of Mother Houcheloup Hourdeloup. The insurrectionists are led by a man named Marius (this Marius bears no resemblance whatsoever to Marius Marius and I have to believe that “Enjolras” was simply deemed too hard to pronounce). Marius has two lieutenants, Joly and Combeferre Comberre. Gavroche decides to join them. He has lost his way since he became separated from Adolphe and Gustave some time ago. He had tried to distract himself “with such amusements as he could find, but often, even in the best contested game of hop-scotch or pitch-and-toss, he would stop and mutter gloomily, ‘But where the deuce can my two children be?’ ”

Gavroche asks Marius for a gun since he had one “thirty years ago” in the “last revolution.” He also requisitions a cart for the French Rebuplic and runs into the National Guard (this is just happening a bit out of order but that is to be expected).

Meanwhile, in the Luxembourg gardens, “Dolphy” and Gustav are eating soggy cake when suddenly an old man appears and offers them a whole non-soggy cake. The man is, of course, Jean Valjean, and, through speaking to the boys, they realize that they are all looking for Gavroche.

“Surely, in meeting them, Providence gives me a sign that I shall find the lad I sought for in vain thus far, and pay the debt I owe him,” thinks Valjean. He takes the boys to his home and sits outside, wondering what to do. “A republican himself in his convictions, he had no thought of joining in this revolt, which he believed to be ill-timed and absolutely in vain.”

Then, who should walk by breaking lamps for the Republic but Gavroche? Valjean attempts to convince Gavroche not to return to the barricades, but when that fails, he puts on his National Guard uniform and goes after him.

The insurrectionists know that no one is coming to join them and have resolved to die for their cause. When Valjean arrives, Gavroche vouches for him. Then, during the first attack, Gavroche threatens to blow up the barricade with a powder keg! Again Valjean tries to convince Gavroche to leave, this time telling him that Adolphe and Gustav are at the house, but Gavroche again declines. He goes out to collect cartridges singing:

I am merry, I am free,

That’s because my money’s spent;

All my clothes in rags you see,

That’s the fault of the Government.

Not a penny can I give,

That’s because my money’s spent;

Like a little bird I live,

That’s the fault of the Government.

I am done for, I suppose,

That’s because my money’s spent;

In the gutter goes my nose,

That’s the fault of the –

He collapses, unable to finish the last verse after having been shot. “Unheeding the rain of bullets that fell about him,” Valjean retrieves his body while Comberre gets the cartridges. However, the barricade is quickly attacked again and Marius, Joly, and Comberre are all killed. Valjean escapes with Gavroche.

In the sewers, Valjean is “guided by chance, or rather, as he himself felt, led by the providence of God” and strengthened by the “miraculous gift [of] God.” He encounters a group of policemen. The police are not there searching for insurgents. They are “making their half-yearly inspection of the sewers; for in spite of the insurrection, the wheels of government still ran on in the old grooves.” Valjean goes unnoticed.

Finally, Valjean reaches a locked grate and encounters a man who offers to let him out for a price:

He saw standing beside him a man dressed in a style more suited for the streets of Paris than for this den of the sewers. . . At sight of that dandified well-fitting black coat, and the youthful handsome face of its wearer, the old man had not a moment’s hesitation in recognizing him. It was Montparnasse. . .He looked at the young man with strange feelings. He felt that [Montparnasse] was as truly sent by Providence to his aid, and to save the life of Little Gavroche, as if he had been a shining angel instead of a bandit, who had taken refuge in the sewer; and that he too was sent to Montparnasse to save him from something worse than death itself.

Montparnasse does not recognize Valjean or Gavroche but, pressuring that the old man has killed the young one in order to rob him, Montparnasse proposes to split the profits. Valjean agrees, on the condition that Montparnasse will receive his share when they arrive “at a better place where we can look over the papers together.” Montparnasse agrees. Montparnasse is slightly surprised to see that Valjean’s victim is a child but it doesn’t bother him much. He even offers to help Valjean sink the body in the Seine but the old man explains that they need the body in order to obtain their reward.

At Valjean’s house on the rue St. Antoine, Montparnasse is terrified when he realizes that the child is Gavroche and confused when he recognizes Valjean. Valjean explains that he is an escaped galley-slave, an inventor, and a manufacturer.

“And why, Monsieur Galley-slave, have you murdered this helpless child? Not for booty, assuredly, for the poor little gamin never owned a penny but to share it. Even wolves would not tear wolves’ cubs for sport.”

“Young man. . .I have not murdered but saved this child. I did not give him wounds, but bound them. Once long ago my hand was reddened with blood shed by an angry blow. That was my crime, bitterly repented and expiated through long years. . . Help me, my son, to draw this boy from the edge of the pit into which he is sliding. Here is your share of the riches I promised you should be gained by this night’s work.”

Gavroche wakes up weeks later, and finds that noxious Paris has been replaced with “a quiet seaside village on the northern coast, called Clairvue.” Upon seeing Valjean, Gavroche believes that the old man has also died and that they are both in heaven, but he is confused to see Adolphe and Gustav there too. Slowly, as he is nursed back to health by a woman named old Jeannette, he realizes that he is not dead. The boys tell Gavroche that when he is better, he can play with them by “the great water.”

“What do you mean by the great water?” said Gavroche. “Is it the river Seine?”

“O, no, it is the real ocean!” cried Adolphe.

“Mother Street” has been replaced by “Mother Ocean.” Valjean sends the boys away before they can say more. Only when Gavroche has had more time to recover does Valjean allow Gavroche another visitor:

A handsome jaunty young sailor appeared at the door, and, approaching, disclosed the face and form of Montparnasse. . .

“My faith! You look like a fancy picture of a sailor lad!”

“Don’t you like it, Gavroche? Isn’t it becoming?” asked Montparnasse with a well-satisfied smile, turning himself round for inspection like a young girl with her first ball-dress.

“I think so,” answered Gavroche emphatically. “The blue shirt beats the black swallowtail to nothing. The girls will look at you and make you more conceited than ever, Montparnasse.”

Gavroche was right. Nothing was ever so becoming to the handsome face and slim alert figure of Montparnasse, as the blue shirt, opening to show his round young throat, the knotted silk neckerchief, the wide white trousers, and the Panama hat with its broad ribbon, which replaced the tight-fitting black suit in which the dandy of the bandits had rejoiced.

It is revealed that Valjean, knowing that Montparnasse’s “weakness,” “vanity,” and “love of admiration” had been the driving causes of his criminality, purchased for him a sailor’s uniform and, knowing that Montparnasse would be “followed with glances of sincere and open admiration from the pretty fisher-girls of Clairvue,” had decided to make Montparnasse into a sailor. Valjean “smoothed away all difficulties” for Montparnasse by purchasing a ship and instating Montparnasse as overseer, rather than as a common sailor. Also, Valjean legally adopted Montparnasse and the other sailors, “receiving Montparnasse as the son of the liberal owner of their vessel, were careful to make the first trials of his new profession as pleasant and as little arduous as possible.”

Away from the “evil associates of his Parisian life” the “gentleness and goodness in Montparnasse’s heart were awakened.” He even took on a new name: Victor Leblanc. Valjean, of course, considered himself to be the father of all four boys, remarking “I shall have four brave sons now, in place of my lonely old age. God is very good to us, my children.” In Valjean, Gavroche “found father, mother, kindred, all in one.”

All was well, until one day Victor encounters a ghost from his past: Manon, who was in Clairvue, en-route to England, in the guise of a lady’s maid. Manon attempts to lead Victor back into a life of crime but Victor refuses. However, he does learn a few things from her.

“Your sister Eponine is dead, Gavroche. She died of consumption in the Hospital of Saint Sadelon.”

“Poor Eponine,” said Gavroche seriously, but not deeply grieved for the sister he had scarcely known. “She was always sickly. The hospital was at least a better place to die than the street.”

Victor also realizes through his conversation with Manon that Adolphe and Gustav – originally named “Jean” and “George” and lost to her while she was “satisfying the police” – are the children of Jondrette and the biological brothers of Gavroche.

[Valjean] bowed his head. Prayerfully he felt that Providence had committed to his care the sons of his deadly enemy, that he might be a father to the worse than fatherless. . .

“My own brothers!” [said Gavroche.] And then, after a pause – “But, father, they were my brothers a truly before, since we are all your children.”

Together the family walks off to look at the sunset, which was “as clear and calm as that which was closing the storm and struggle of Jean Valjean’s life.”

The End.

This post is already so long that adding a read more seems ridiculous but whatever.

Note about the author: Gavroche: The Gamin of Paris was “translated and adapted by” M.C. Pyle aka Margaret Churchman Pyle. Margaret was the mother of the famous children’s book illustrator Howard Pyle and of the prolific but lesser know children’s book writer, Katherine Pyle. The Pyle family was one of Wilmington Pennsylvania’s old Quaker families (side note: although Howard didn’t ever illustrate a scene from Les Miserables as far as I am aware, he was a great influence on Mead Schaeffer who did).

Note about the publisher: Porter & Coates, located in Philadelphia, published over 100 children’s books. Their popular Alta Edition series (to which most copies of "Gavroche" for sale today belong) consisted of reprints and was published between the 1880s and 1890s. (Whereas the original Gavroche was printed in 1872 but I’ve only seen one photograph online of what I believe to be a first edition.)

Pyle's other book, published around the same time and through Porter & Coates, was called Minna in Wonderland and could generously be called an "alternative" to Alice in Wonderland. The same is true of Gavroche.

Note on Margaret's translation: I did not compare Pyle's story line by line to the original text but for the most part (for the parts which were actually from the text) her translation seemed fairly true, though obviously heavily abridged and simplified for her readers. I liked her choice of English slang equivalents, which I compared to those used in the Wilbour translation (the translation I assume she would have had at her disposal). Wilbour mostly left the argot untranslated, whereas I thought Pyle's word choice was readable and fun. I also liked Pyle's choices for Gavroche's songs. At least one song is a traditional English language folk song, while others seem to be Pyle's invention, rather than attempted translation. Here they are:

[After his parents are arrested]

I’m a jolly stroller boy,

Bold and free, bold and free.

Now an orphan I must roam,

Since my folks are all from home.

I can bear it till they come

Back to me, back to me.

[On his way to join the insurrection]

Louis Philippe will lose his sheep,

And never again shall find them;

The people of France will make an advance,

And leave their King behind them.

[While scouting out the National Guard and stealing a cart, #236 in the Roud Folk Songs index]

Let’s go to the woods, said Robin to Bobbin;

What will we do there? Said Bobbin to Robin;

We’ll shoot at a wren, said Robin to Bobbin,

‘Tis the best of all four-footed game.

[Sung to let the insurrectionists know he is near]

Morning is coming,

The day dawns clear;

Open the door

Till my story you hear,

In blue uniform

And bearskin chapeau

The soldiers are coming;

Co-co-rico!

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

btw there's one thing I don't understand about Fantine (and I think this is also a problem of Hugo generally having a hard time thinking of women as whole people and not rhetorical devices, but not just): she is an "innocent", she represents a naive tenager/young woman who doesn't understand how society works or doesn't think ahead about money and assumes Tholomyes is gonna be there for her etc. you know. But she's also... an orphan raised on the streets (in Paris).

so I don't understand how she is simultaneously the picture perfect waif while also beeing hardened by the life of a gamin (or the girl equivalent) ? I'm not saying someone who was raised on the street couldn't do all she did I'm talking about how Hugo frames her as this pure little innocent who doesn't know abandonment doesn't seem to know how to survive with very little money without her neighbor to give her tips? Needs to learn how to endure the taunts on the street when presumably she's had plenty given what life with Gavroche was like.

I dunno man. What's going on there

#either there are some missing context clues in there#or we're supposed to believe she has the memory of a goldfish

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

What a nice way to finish the very long third volume. Hugo circles back to the gamin with whom he introduced the tome! (Although I'm not entirely sure why he chose to reference that obscure mention of Gavroche in tome two, when he was crying in the cradle. Perhaps, simply to remind the reader that he is a part of the ill-fated Thénardier clan.) Gavroche is “pale, thin, clad in rags, with linen trousers in the month of February” and he sings a lot — all of which make him a miniature version of Éponine. He arrives at the empty and locked Gorbeau house, only to discover that his (unloving) family is imprisoned. His response to this news is simply an "Ah!" and he goes away singing. (@akallabeth-joie gives some contextual information about women prisons in Paris where female members of the family were taken) This chapter also marks the end of the very long day, portrayed hour by hour.

Symbolically, the tome titled “Marius” does not feature Marius in either its opening or closing chapter. Marius has also mysteriously vanished.

Tomorrow, we’ll delve into the fourth volume, which commences with a new portion of digression. This might require some tuning for readers (spoiled by the entire last book filled with suspense and action). So, let’s get ourselves ready!

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is all the fault of @pilferingapples and @midautumnnightdream. I take no responsibility for this. Steampunk AU heavily inspired by Steampunk Musketeers and it is still 1830s Paris.

Twenty years ago, there was still to be seen in the southwest corner of the Place de la Bastille, near the basin of the canal, excavated in the ancient ditch of the fortress-prison, a grand mechanical contraption. We say grand although a more accurate term would be a relic. it was already rusted past recognition. It was a grandiose idea of Napoleon--a mechanical invention that took several men, several coffers of the public’s money as well as several years to construct. Successive gusts of wind over the years had blown away much of its gears and the rains had done the rest by eroding its plaster and bright paint. It was some mighty symbol, one knew not of what, few people visited or even glanced at it nowadays.

Many who passed by this relic would have considered themselves cogs in the machine of the state, some were too poor to be even that and went unnoticed by the state. The poor fell through the cracks of the bureaucratic machine which resembled a grotesque hydra not unlike the Elephant, a darkness that was resistant to all forms of light. The young gamin who went by the name of Gavroche, and lived in the Elephant was the only light visible. The gamins would invent games using the mechanical cogs and gaze at the new gadgets present in shops, with a mix of wonder and awe, both admirable qualities that all children possess in heaps.

None of that is relevant to this story. By which we mean, if the reader permits us to give a sketch of Paris as it was, we will also be able to give the sketch of the shops frequented by Parisians where at this epoch of fashion, sleeves were ballooning and burgeoning outwards, inspired no doubt by the airships; a spectacle that had recently arrived and taken Paris by storm and which also caused much debate among our friends, the gamins and gamines, who were little science enthusiasts though unlettered.

Cosette scanned the building in front of her. Her studies at the convent had taught her how to climb buildings effortlessly, the nuns had mastered parkour; and her father had a number of gadgets in the house, which he had always allowed her to use freely. While she wore a fashionable black gown and carried a sharp blade tipped parasol, and a brightly coloured purple hat that concealed a parachute, that was not all she carried; in her sleeves at all times were, a small coin with sharp ridges, a mechanical bow and arrow contraption, a pocket watch that also contained several knives and lock picks, as well as a pair of binoculars which folded neatly. She had used the gadgets to scale the wall of her bedroom and meet a young gentleman in the garden, unbenownst to Toussaint and her father. This young gentleman had been puzzled by the new technology that Cosette showed him.

She had learned from her papa how to use this technology for her benefit and her papa’s as well; not from anything he said, but from his manner of keeping secrets, his manner of only walking in the garden at night, and disappearing for days on business; how to avoid running into gendarmes and police in Paris. Cosette intuited that her papa would not like the idea of running into the Parisian police, he would move living quarters at the slightest hint of anyone asking his whereabouts. That was fortunate, since Charles X had cracked down more and more on any new technology as well as on the journalists talking about it until the July Revolution ousted him; his own government remained just as the Elephant; a relic, inefficient but tyrannical. Louis Phillippe’s government though less censorious was also random about censorship and spies and one could not be too careful about. Cosette surmised a difficult past for her papa and avoided the police accordingly.

Marius had told her how he had met a group of students that had literally dazzled him with their light, all were radiant and full of a brightness, and their excited discussions of new technology carried on till late hours. The pace of discussion on airships, hydraulics, faster steam powered trains, more precise surgical equipment, new mechanical contraptions to evade spies; all of it was too rapid for him to follow along. It was a buzzing hive of ideas and Marius found himself out of depth. So it surprised, nay shocked him when Cosette also produced many of her own mechanical contraptions which she had used many times. He very nearly fainted, it must be stated, as he had when her dress had sightly blown with wind and revealed her dainty ankles. Cosette smiled sweetly and turned the conversation to other matters. She was nothing if not considerate of Marius’ technology deficient upbringing in the Gillenormand household.