#frisian archaeology

Text

King’s Field Pendant

This magnificent pendant is the ultimate proof that the “Dark Ages” is an academic concept. Rather than Europe plummeting into darkness because of the “fall” of the Western Roman Empire, it’s more the lack of academic interest in the Early Middle Ages.

This Anglo-Saxon pendant was found on King’s Field (Kent) and is made of gold and garnet, but decorated extremely intricately with gabuchon, filigree and granulation. The garnet was used to form a triskele with round centre and ending in bird heads. At just 3,5 cm across, this was made by a master craftsman with materials from all over the known world.

The pendant might have been worn on a bit of string or rope, or it may have been worn as part of a glass beaded necklace. The pendant likely belonged to a woman.

The British museum, England

Museum nr. .1145.’70

Found in King’s Field - Kent, England

#merovingian#anglo saxon#viking#Vikings#frankish#carolingian#charlemagne#viking archaeology#germanic archaeology#Merovingian archaeology#Anglo Saxon archaeology#field archaeology#archaeology#field archaeologist#frisian#frisian archaeology#Germanic#jewelry#almandine#garnet#roman empire#western Roman Empire#germanic mythology#viking mythology#Norse mythology#pagan#kent#england#anglo Saxon England#paganism

822 notes

·

View notes

Text

Atlantis of the North Sea -Rungholt

"Today I drove over Rungholt,

The town went down six hundred years ago.

Trutz, Blanke Hans."

"From the North Sea, the Murder Sea, separated from the mainland,

The Frisian islands lie at peace.

Trutz, Blanke Hans."

"A single cry - the city is sunk,

And hundreds of thousands have drowned.

Trutz, Blanke Hans?"

Trutz, Blanke Hans by Detlef von Liliencron 1883

Rungholt is also often referred to as the Atlantis of the North Sea, as there are still many legends surrounding this town in the Wadden Sea.

Rungholt was a town on the island of Strand in the North Frisian Wadden Sea (North Germany) and sank during the Second Marcellus Flood, also known as the Grote Mandränke, on 16 January 1362.

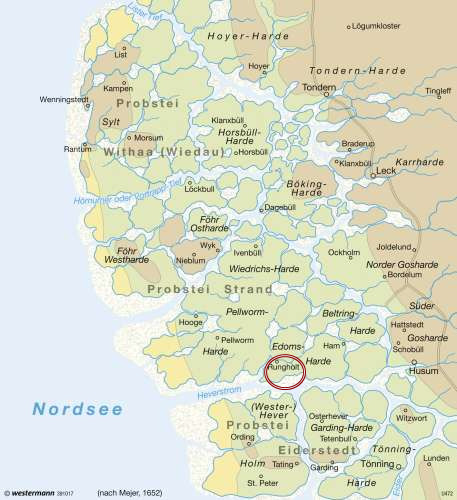

The North Frisian Coast with its islands, Halligen and the Wadden Sea before 1362 (x)

Now, in the course of time, several cities have sunk, so the question arises as to what made Rungholt so special that it was called the Atlantis of the North Sea. Rungholt mined peat and extracted salt, which they sold well. According to legend, Rungholt was incredibly rich, a large city in the middle of the mudflats. According to one legend, this made the people arrogant and thought they could go against God, whereupon he punished them with the flood. Another legend says that at a drinking party, it must have been around 1300, a few men, wild with wine, got a pig drunk. They put a nightcap on it and put it to bed. They laugh, they bawl, they call the priest to anoint the terminally ill man. The priest refuses. The men threaten him with beatings, drag him to the bed and pour beer over his hosts. Outraged by the desecration of the sacrament, the priest prays to God. Rungholt shall atone. The following night, a storm comes up. And while the lords of the town still stand on the dikes, blinded by their wealth, and think they can defy Blanken Hans (which is also the name given to the raging North Sea in a storm), the tide rises four cubits high over the tops of the dikes, swallows the town and everyone in it drowns. It is said to lie at the bottom of the sea to this day, pleading for salvation.

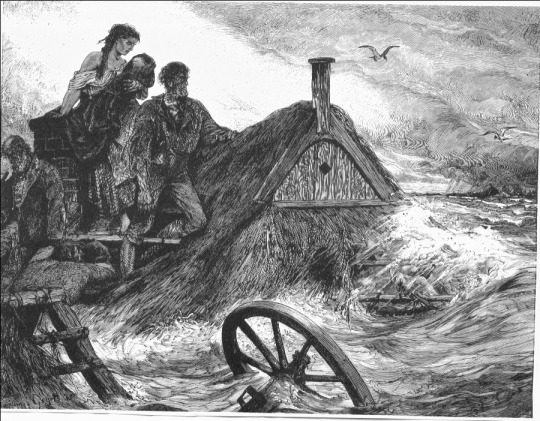

Dike breach, engraving by Johann Martin Winterstein from 1675 (x)

Unfortunately, there are hardly any records and none from that time, which makes Rungholt so legendary and even makes many people doubt that it really existed.

The first mentions date back to the 17th century and even these were initially questioned until a will was found in Hamburg. It dates from 1345 and has the full entry "Edomsharde, Kirchspiel Rungholt, Richter, Ratsleute, Geschworene, Thedo Bonisson samt Erben" (Edomsharde, Rungholt parish, judges, councillors, jury, Thedo Bonisson and heirs) as the addressee. To date, this is the only known document from the time before the town's demise. Obviously, Rungholt must have really existed and was even so large that it had its own church. The ethnologist and cultural historian Hans Peter Duerr even believes in a town the size of Hamburg, which had about 5,000 inhabitants at the time. He has evidence in the form of archaeological finds.

The first finds were made by fishermen in 1880, who found pottery shards, brick remains, large wooden remains and even plough marks from fields. Further finds were made in 1921 and 1940, where around 100 wells, the remains of about 28 terps, dike imprints and several supposed sluices were found, which later turned out to be sluices built by the inhabitants to drain the land.

Andreas Busch salvages beams of the so-called "Rungholtschleuse" (Rungholt sluice)1922 (x)

But is this really Rungholt or other towns that were also in the vicinity? There is a tendency to locate the town near the Hallig Südfall. But the Hallig has moved steadily eastwards over the centuries, and over time it has also migrated into the area of the vanished Rungholt. Today, therefore, it only reveals traces of a possible settlement at its north-western corner. But whether this is really Rungholt is questionable.

Storm tide,by Johannes Gehrs, 1880 (x)

This is still a matter of debate, but researchers have reconstructed the town as follows.

Rungholt was settled about a century and a half before the sinking. The houses, built of clay and grass sod, provided space for about 1000 inhabitants and stood on about 25 terps and on a dike about two metres high. Their livelihoods were based on livestock farming, seafaring, salt extraction from sea peat and trade. Around their settlement they cultivated grain, especially rye, on vaults.

The region today (x)

The fact that Rungholt stood on a dyke, on which the mounds were located and the area was drained, made the land quite unstable. The Second Marcellus Flood was not a light storm, but lasted for three days. The dykes gave way bit by bit, the water swept everything away and undermined Rungholt's land, forcing it to sink. But it wasn't just Rungholt that was affected: more than 100,000 people are said to have died in the floods, lands sank and entire villages disappeared from the map almost without a trace. This fate struck 28, according to other sources at least 32, villages. Which clearly left its mark on the landscape.

51 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi ! How are you ? You seem really cool ! I have a few questions for you :)

I was wondering what parts of your studies did you like the most ? Like a favorite subject , specific assignments , a very good teacher...

Do you still struggle with gender stereotypes in your line of work ? And if yes do you see an evolution since you started ?

And it's a little unrelated so i understand if you don't want to answer ,but i saw belgium in your description, do you speak french ?

Hi! So nice of you to stop by!

I'm okay at the moment, the end-of-the-week-tiredness has set in.

I never really knew what archaeology classes would be about, and I have noticed between colleagues who went to different unies that classes may very a whole lot. However I never expected myself to like landscape and ecology as much as I have. It's super duper interesting and all of a sudden with just a few classes things made so much more sense! I'm Belgian with a Dutch father and going to the Netherlands all the things I was so used to seeing in the landscape suddenly told me stories that go back 450 years or even pre-history!

Within archaeology itself there isn't that much of gender stereotypes going around. Archaeology is one of the most LGBTQA+ friendly work environments and I can name many colleagues who are on that "spectrum", including myself! People are often surprised to hear that archaeology is dominated by women. Very few male archaeologists will feel bad about it. It's a fact and that's it. It's nice to have men around because they are just physically stronger than women. On the other hand women tend to have a longer attention span and are better at detail work such as skeletons and have a better steady hand. But the basic heavy labor is equal to us both. The public however only knows archaeology stereotypes: dinosaurs, treasures, Indiana jones,... and they all expect us to look like Phil Harding (Phil I love you, but sorry :/).

I am indeed Belgian, but Flemish born so a native Dutch speaker. I have learned French but don't use it often and im much better at Germanic languages. I have learned high level English in no time, could speak basic German in two and a half months and I understand some Swedish, I know how to use Cyrillic, and am comfortable around Old Dutch, Old (High) German, Anglo Saxon, Frisian and old Norse. I can transcribe Gothic and Early Modern Dutch and English.

However I have tried Spanish, couldn't get going with it, and after all of the years I've had French in school, its actually pathetic and im almost scared to speak it because they focussed so much on exceptions in the language that we lost track of basics. Latin was never a question. Plain "nope".

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The central Roman administration of Britannia ended in about 410, but the actual end end of Roman Britain wasn’t until about 200 years later. Britannia was a Roman province for nearly 400 years. Over that time countless Roman soldiers and administrators lived among and intermarried with the Celts, creating a hybrid culture that was nonetheless distinctly “Roman” in language, culture, customs, law, and so on.

Around the beginning of the 5th Century CE, some Roman garrisons began to be withdrawn to Gaul, probably to shore up the continental legions on the German frontier. In 406, as money from Rome began to dry up, the army in Britannia revolted and set up a series of rival “emperors” from its ranks, the last of whom was defeated and executed in 411. 410 is usually cited as the “end of Roman Britain” because Emperor Honorius is said to have sent the civitates a letter telling them they’d have to fend for themselves. So it’s fair to say that’s when central Roman administration ended, but Britain was still very Roman in character, full of people who considered themselves Romans.

Civic construction collapsed as resources were diverted. Romano-British towns faced terminal decline. Few new buildings were erected, many old ones were abandoned, and by about 400 there was little left in most places but a wasteland of ruins and rubbish. A near-total collapse of the Roman settlement pattern – not just the disappearance of towns, but of villas too, and indeed many native villages and farmsteads.

Stone building tended to disappear everywhere north of the Loire; whereas in Italy, it was so important that it got its own articles in the code of law of king Rothari. There was a genuine replacement of skills, not to mention large projects -building from stone- would not have been feasible during a period of upheaval. What happened was not any kind of clumsy imitation of Roman formulas, there was a genuine re-appearance of the classic Celtic style, of a kind that had not been build south of Hadrian’s Wall for 400 years. Details, such as gates, show that Roman ideas were intertwined therein with the Celtic, but what we have in south Britain in the early 500s is a genuine return of a kind of building that had not been seen for centuries. North of the Wall, the traditions of Celtic royalty had never been replaced by those of Roman power. There are many signs in archaeology and Welsh tradition of such a “northern takeover”, including the importance of the distant tribe of the Gododdin in early Welsh tradition.

Beginning in the middle of the 5th Century, Germanic “Anglo-Saxon” tribes (they were from dozens of tribes, but A-S is a convenient shorthand) began to settle in the eastern part of the island. Under the stress of the “barbarian invasions” and in absence of a central authority, the various Breton cities began to fight amongst themselves and fracture into petty kingdoms. The Anglo-Saxons very gradually pushed west, though for nearly a hundred years in the mid-5th to mid-6th century, a north-south line of control largely stabilized, with western England and Wales remaining Breton.

Even smaller Anglo-Saxon kingdoms like Mercia etc. took a while to take shape due to the staunch resistance from Celts to the German settlers.

The Anglo-Saxons conquered or assimilated the various petty Breton kingdoms over time, while at the same time adopting some of their Roman traits and customs. There was also substantial Breton immigration to Gaul.

Like the Franks, the Saxons/Angles/Frisians/Jutes intermarried with the Bretons. The extent to which they did so seems to have varied regionally, but the English were as mongrel as the Normans; they even had a substantial Norse contribution.

By around 600CE, with the exception of Wales, the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms had absorbed all of the formerly Roman territories. While the Roman influence was never really lost, “England” was from then on a group of shifting and consolidating Germanic kingdoms, with periodic influxes of Scandinavians, until William of Normandy landed nearly 400 years later. Who along with his allies at The Battle of Hastings decapitated the whole of the Anglo-Saxon aristocracy, only a few Thanes were left alive.

In 1066, Britain was invaded twice. First, a Norwegian army led by Harald Hardrada landed in the north. Harold Godwinson, the King of England, killed Hardrada in a battle at Stamford Bridge in Yorkshire. Three days later William's Norman army landed in Sussex. Harold hurried south and the two armies fought at the Battle of Hastings (14 October 1066). The Normans won, Harold was killed, and William became king.

Now it was the Normans turn for a hostile takeover. William replaced the previous management team with his own people, who would through gifts of land be, beholden to him and not the previous lot.

After any successful coupe, revolution, or conquest its pragmatic to get rid of what’s left of the opposition, neutralize, or sideline, or just render them helpless. Next of course, is to quietly remove your most powerful helpers, so that they don’t get the same idea you had, and make similar moves.

The overwhelming majority of Britain continued to work the land practice trades but for Norman landlords instead of Saxon ones. The Normans were quite small in number and would have been outnumbered by the “locals” but they took the positions of power in order to rule, many even marrying into Saxon noble families to bolster their claim to the land. The melding of Norman French and Anglo Saxon was to form the basis of early English. The Saxon aristocracy was largely expropriated. Initially William tried to rule Northumbria through the “native” elite, but they rebelled frequently. Many of the dispossessed Saxon nobility moved to Constantinople to take service in the personal guard of the Byzantine Emperor, which had previously been recruited from the Vikings of Kiev.

By 1066, though, it's worth noting that much of the Anglo-Saxon nobility was partially or fully Scandinavian, due to the Norse conquests in the Early Middle Ages. William's main rival Harold Godwinson, for instance, had a Danish mother and his father had first risen to prominence under the rule of the Scandinavian king, Cnut the Great. Ironically, the Normans themselves were also displaced Scandinavians who had settled in Northwestern France on the condition that they convert to Christianity and swear loyalty to the then-King of the Western Franks, Charles the Simple.

The Normans built castles of solid stone, up and down the country, as bases for control, while the “Saxons” had used wood almost exclusively until fairly recently; they had no tradition of castle building. The white tower to control London, Striguil ( chepstow) to invade Wales, Clifford's Tower in York Castle to subdue York, the list goes on.

The Norse settlers were essentially the military equivalent of their subjects. The Anglo-Saxons had similar traditions of tactics, weaponry, and recruitment. In contrast, the Normans utilized their Franco-influences to make it possible for the ruler of Britain to quickly gather his vassals and overwhelm rebellions with relatively smaller numbers. This was primarily due to the tactical and operational advantages of the Norman Knight over his Saxon counterparts. Furthermore, because Britain was unified under William, any rebellion was usually kept to a single region; this meant that the rulers could call the Saxon levies from other regions and essentially have more resources available compared to the local conquests of the Norse.

When the Normans conquered, they largely replaced the very highest tiers of the British nobility, but were more than willing to allow the Earls Morcar and Edwin to keep their titles…until they rebelled. They were attempting to take over a stable, economically developed realm with a clear legal system and a history of prior conquest. Systems were already in place to suppress rebellions in parts of the country, and these systems were utilized by the Normans.

For 300 years after the conquest there was a legal distinction between the English and Normans called “Englishry” which basically said that if a Norman was murdered the entire community would be punished but if the victim was English there would be no such punishment. Every thing comes around full circle I suppose knowing the English past. Same probably in store for Normans in the future from another tribe.

The Normans gradually became mostly the Plantagenets. The Anglo-French War (1202-1214) watered down the Norman influence as English Normans became English and French Normans became French. During the reign of the House of Plantagenet, which lasted nearly four centuries, the Kings of England were all French speaking and most likely would have identified as French. Henry V was the first of the Plantagenet line to speak English regularly and by that time his house had been at war with the French sovereigns for about eighty years. After Henry’s early death, the English started fighting among themselves but the combatants were still cousins of the Plantagenet line. The Tudors won, but they couldn’t keep it going and were replaced by the Stuarts, who couldn’t keep it going either. The current royal line is largely descended from the Hanovers, a German royal house who were distant cousins of the Stuarts. The Plantagenets really ended when Henry VIII (who was a Tudor) had executed most of his Plantagenet relations, though their main power ended in 1399 with the abdication of Richard II. By the time Edward VI became King, in the early 1500s, the Plantagenets really were finished,

The first three Henries were fiRmLy Norman, but Edward I, whose reign began on 1272, was the first post-conquest King to think in terms of uniting Wales, England and Scotland, as the first King really focused on Britain without much reference to France. By this stage England had lost most of France anyway.

Only begrudgingly were occasional compromises made for the English underclasses over the centuries, although the Normans never completely did away with “free” Anglo-Saxon traditions – many of which were incorporated into common law or what later became the House of Commons. This all began to change during the mid 1600s.

Due to a combination of political disagreement, financial mismanagement, social malaise, and many of the Renaissance, Enlightenment, and Protestant ideals of the era, the Parliamentarians began to challenge the authority of the ruling elite, which culminated into the English Civil War. This war also had racial overtones – some Puritans and Parliamentarians saw it as their opportunity to remove the oppressive Norman elites and liberate their Anglo-Saxon brothers, re-establishing the kind of “egalitarian” societies that existed throughout the Germanic world and had been more prominent in England prior to the Norman invasion.

Many Puritans in North America returned to England to fight in this war of freedom for the Anglo-Saxon race. After the Puritans came out victorious, thousands of aristocrats fled to North America to re-establish a society resembling the Royal life they had left behind. In North America, they encountered a class of wealthy landed elite originally from the English Caribbean colonies who also sympathized with the Royalists, and eventually joined forces with these to produce the antebellum aristocracy of the American South.

During the tense era leading up to the American Civil War, these same racial overtones re-emerged. Southerners saw theirs as a fight of the superior Norman aristocracy against the Anglo-Saxon riffraff in the North. Southerners believed that they belonged to a master Norman race, separate from and superior to the Yankee Anglo-Saxons. One Southern journal openly declared:

The Cavaliers, Jacobites, and Huguenots who settled in the South naturally hate, contemn and despise the Puritans who settled in the North. The former are master races – the latter a slave race, the descendants of the Saxon serfs….The Saxons and Angles, the ancestors of the Yankees, came from the cold and marshy regions of the North, where man is little more than a cold-blooded amphibious biped.

Another Southern journal declared:

The Norman cavalier cannot brook into the vulgar familiarity of the Saxon Yankee, while the latter is continually devising some plan to bring down his aristocratic neighbor to his own detested level.

The Royalist and Cavalier descendants condemned the backwards Anglo-Saxon peons as a race unfit for rulership and incapable of their level of refinement. Many Southerners openly expressed a desire to re-subjugate the United States of America to Crown rule in England. The American Civil War was cast as a war for Norman liberation from Anglo-Saxon tyranny. It was a struggle to “reverse the ill-conceived American Revolution, which had been contrary to the natural reverence of the Cavalier for the authority of established forms over mere speculative ideas”. With the South's defeat, the United States was established unequivocally as an Anglo-Saxon country, not a Norman country. The English Civil War was at last brought to its complete end.

Thus, being proud of Anglo-Saxon heritage is something one is more likely to hear a person in North America, particularly the United States, say, rather than in England.

Norman England never really ended; the same Norman names and families have been in positions of power and influence for most of the past thousand years. The major landowning families are still pretty much “pure” Norman, to a truly remarkable extent owing their land and position ultimately to the redistribution of land after 1066. “Anyone” can become Prime Minister but the people advising him or her and the people funding them or their party will tend to be from a fairly narrow demographic. The working (“English”), middle (mixed) and upper (Norman/French) classes. And they are still there today.

In other words much like most modern, post-revolutionary, quasi-democratic, ostensibly plural democracies that are still -and always have been and always will be- run by a tiny, unrepresentative elite. Bums becoming aristocrats. Aristocrats losing power and fading into nothing as compared to before or dying in battle. The span of time the rise and fall of so many nobodies.

0 notes

Note

Showing my ignorance here, but I've seen a lot of posts and articles and so on about how Týr is associated with justice, honour, fairness, and other noble attributes. I was just wondering if there's any ground for this?

It's interpretive but it's not out of nowhere. I think it's speculative to assert that all of these things are right, but if nothing else, we can at least say that Týr has become the de-facto inheritor of certain ideas and attributes that definitely existed, even if there isn't an unbroken chain of tradition regarding to whom they were attributed.

And this might be an aside, but of course none of that tells us what in particular is meant by "justice," etc, especially over the course of major upheavals in social and political organization over the time periods we're looking at (or, just spitballing here but, whether "justice" means something different in relation to Týr than in relation to, say, Forseti). Starting by taking a word or concept "justice" and then reading it into a culture for which it's an etic term is the wrong way to do that, but for now we can still discuss Týr and delay that larger conversation.

I think the sources can be grouped into four categories, all individually insufficient but together forming sort of a heat map with cluster in the area of public assemblies and justice:

actual point-blank descriptions of Týr in Norse mythology

inferences from trying to read through interpretatio romana

place-names

comparative mythology

One thing to keep in mind before we begin is that Týr is both the name of a particular god, and a generic word for any god. That means there's a high risk of misidentifying a reference to any god as a reference to a distinct individual with the personal name Týr. Importantly, those conditions have been true for a very long time, so that people like Snorri could have been susceptible to it as well. I'm not going to bring this back up or comment on it further, but just keep it running in the background.

Týr in Norse mythology

In Norse mythology, Týr basically only has one myth, but it's a big one -- binding Fenrir, and giving up his hand to do so. This seems to be his defining feature in Old Icelandic literature, to the point that you can say "the one-handed god" to signify "the letter 't'." When Snorri tells the myth, the attribute of Týr that he emphasizes is courage more than anything pertaining specifically to justice. But what most modern heathens read into it is that Týr was the only god who stepped up to face the consequences of the gods' collective deceit. A lot of people see him in relation to the idea of personal sacrifice for collective good.

This isn't building to the main point, but while we're on the subject, Snorry also says that Týr is known for his wisdom, so that someone who is very wise can be called týspakr 'týr-wise'; and that he is good to call on in battle and for things done by strong and bold (hraustr) people. It is very possible that there is a connection between Týr the divine being and the line "name Týr twice" line in Sigrdrífumál in connection with "victory-runes" (sigrúnar), whether or not this also means literally inscribing two týr-runes as is also speculated.

That all might not be enough to go on on its own, but by following the transitive property of interpretatio some scholars and heathens bring in evidence from elsewhere to supplement this.

Germanic Mars

Tuesday of course comes from West-Germanic-speaking people calquing "Mars' day" (diēs Mārtis). Several authors from the ancient world mention that various Germanic people venerated Mars, and we also see (a very small, but important, amount of) evidence for that in the archaeological record, where it overlaps with Germanic people inscribing Latin. Many scholars take it for granted that these instances refer to the god whom, in their own vernacular, those Germanic-speaking people would call *Tīwaz (or whatever reflex of it), that is, Týr.

The most important of these are two votive stones put up by Frisian soldiers in the Roman military stationed along Hadrian's wall, dedicated to Mᴀʀs Tʜɪɴᴄsᴜs (also written Tʜɪɴɢsᴜs), 'Mars of the Thing.' Why Mars would be associated with people's assemblies is not clear but if this name were a standard equivalence for Týr (as seems likely to occur if they're Latin-speaking and keeping track of what day of the week it is), and if Týr was particularly important for these assemblies, then this difficulty is easily resolved. Mars Thingsus appears twice, and both times alongside the two Alaisiagae, once named Beda and Fimmilena. The Alaisiagae also appear a third time independently of Mars Thingsus, but with the names Baudihillia and Friagabis. The meaning of the collective name Alaisiagae is not clear, but two of the individual names, Baudihillia and Fimmilena, have been linked to certain Frisian law terms, bodthing 'summons' and fimelthing 'sentence' (though this is not accepted by everyone, and some scholars think this grouping of deities as a whole has mixed Celtic-Germanic origin, which is not uncommon in that context).

All of this is to say, we have very early evidence of a certain Mars Thingsus with an extremely likely connection to people's assemblies known as the thing, þing. There's no indication of what the people who raised those votive stones called him when they weren't calling him "Mars," but because we know that there was correspondence between Mars and *Tīwaʀ in the context of day-names, the most logical way to identify Mars Thingsus with a known Germanic deity is to connect him with Týr/Tīwaʀ.

This all sounds very possible but I will emphasize that although this is very neat and tidy it is still speculative. We don't know if this interpretatio worked in a one-to-one way when spread over Germania, and Mars Thingsus could have been an entirely individual deity about whom we otherwise know nothing. Maybe there was a Germanic god called *Þingsaʀ whose name didn't make it long enough to be written down in vernacular texts. Given that these were Frisians, maybe the Icelandic deity with whom Mars Thingsus should be identified is Forseti rather than Týr (fwiw, "Forseti" sounds more like a title than a personal name to me, such that I'm very prepared to accept the idea that we don't know what Baldr and Nanna actually named their son, so to speak, though I might be biased because I actually lived in a country where "Forseti" is a title and not a personal name). Or perhaps (most likely, imo) there isn't a clear through-line from 3rd century Germanic-speaking soldiers in the Roman empire to Icelandic mythology.

Place-names

Not much to say here, but Simek says that Tislund (< *Týslundr 'Týr's grove'), Denmark was the site of a þing. I don't know anything about the distribution of theophoric place-names that are also þing sites, i.e., I don't know if there are a bunch of 'Thor's grove''s out there that indicate that this Tislund is more likely random than a meaningful connection. There are ways to study this, so let this be my disclosure that I'm not doing that right now, but it would be a worthy thing to do.

Comparative Mythology

The word Týr, from Proto-Germanic *tīwaz, is cognate with other Indo-European words meaning 'god,' and with Lithuanian Dievas, another god whose name is the proper form of a common noun meaning generally 'a god.' It's not a direct cognate to, but is related to, certain other specific gods' names like Zeus and Jupiter (Jove), and its ultimate source is a derivation from an Indo-European word referring to "brightness" and "the sky."

I'm often critical of the ways that heathens and scholars use etymology to explain non-linguistic things (and like... the weird baked-in unspoken assumption that people don't share and spread culture laterally...?), but this has been extremely influential in Norse and Germanic scholarship. Generations of Norse/Germanic scholars and heathens have upheld the idea that Týr is the Indo-European Sky Father, and have looked for ways to resolve the differences between that reconstructed proto-deity and the Týr we actually see in the Eddas, but without breaking continuity. You'll see heathens say that "Týr used to be the Allfather before Óðinn took over." This is perhaps not entirely incorrect, but is definitely reductive. Regardless, a "Sky Father" type deity is very much resolvable with, even expected to be, a god of law and justice. The other hints toward an association of Týr with law and justice that I've already mentioned are very compatible with the idea that these attributes of Týr descend from a tradition ultimately leading back to a Sky Father-type deity. In this regard, it might actually be important that a significant amount of this evidence is from before the Migration Age, because while the 4,000 or so years between the Indo-European language and our early evidence for Germanic religion surely had some disruptive events that we can't reconstruct, we are damn sure that the Migration Age was incredibly disruptive to a very large amount of traditions.

So anyway, all of these things I've mentioned are things that heathens tend to take for granted or state with more certainty than they probably should, but taken all together it makes a pretty good case that even if those historical statements aren't entirely secure, that heathens are justified in regarding Týr as a god pertaining to justice in modern times. I actually think this is interesting in certain ways that it wouldn't be if it were all just spelled out point-blank for us in primary sources. None of it really actively conflicts with the Týr that we get from the Eddas, and it's all stuff that's important and should be accounted for by modern heathens. I see it as a sort of productive reincorporation, really an act of creation that might be a faithful recreation of something (and we have no way of knowing with the evidence we have) but which doesn't need to be.

What I think remains unresolved is the bigger discussion of what "justice" means in-context. But that's for another time.

Quite a lot of this post was informed by Rudolf Simek's Dictionary of Northern Mythology.

66 notes

·

View notes

Photo

England’s Largest Anglo Saxon Gold Coin Hoard Found

Norwich Castle Museum hopes to acquire the largest Anglo Saxon gold coin hoard ever found in England

The largest find to date of gold coins from the Anglo-Saxon period in England has been revealed after it was unearthed by metal detectorists in a field in West Norfolk.

Buried shortly after AD 600, the West Norfolk hoard contains a total of 131 gold coins, most of which are Frankish tremisses, solid gold coins from the Frankish Kingdoms of Gaul and Western Europe, which were not yet produced in East Anglia at the time.

The hoard also contains nine gold solidi, a larger coin from the Byzantine empire worth three tremisses and four other gold objects, including a gold bracteate (a type of stamped pendant), a small gold bar, and two other pieces of gold which were probably parts of larger items of jewelry.

It is thought the presence of these items suggests that the coins should be seen as bullion, valued by weight rather than face value. Experts say the haord will help transform our understanding of the economy of early Anglo-Saxon England.

“This internationally-significant find reflects the wealth and Continental connections enjoyed by the early Kingdom of East Anglia,” says Tim Pestell, Senior curator of Archaeology at Norwich Castle Museum, which hopes to acquire the find.

“Study of the hoard and its find spot has the potential to unlock our understanding of early trade and exchange systems and the importance of west Norfolk to East Anglia’s ruling kings in the seventh century.”

East Anglia is famed for its Anglo Saxon heritage, but the previous largest hoard of coins of this period was a purse containing 101 coins discovered at Crondall in Hampshire in 1828. It had been disturbed before discovery and may originally have included more coins. Buried around AD 640, the hoard contained a mixture of Anglo-Saxon, Frankish and Frisian coins, along with a single coin of the Byzantine Empire, minted in Constantinople.

Archaeologists now regard this period – the decades on either side of AD 600 – as quite literally a ‘golden age’ for Anglo-Saxon England. The largest find of gold metalwork from the era is the spectacular mid-7th century Staffordshire hoard, discovered in 2009 by Terry Herbert and comprising over 5.1kg of gold and 1.4kg of silver. But it contains no coins.

Back in East Anglia, the famous ship burial from Sutton Hoo in Suffolk, which dates somewhere between AD 610 and 640, includes a purse of 37 gold coins, three blank gold discs of the same size as the West Norfolk coins and two small gold ingots, as well as many other gold items.

The Sutton Hoo purse contained only Frankish coins, reflecting the fact that although imported coins were already used in East Anglia by this time, they were not yet being minted in the area by the time of the burial.

Another important Anglo Saxon grave was discovered in 2003 at Prittlewell in Essex, probably buried a few years before the Sutton Hoo ship, and yielded two gold coins and other gold objects.

The majority of the objects in the latest hoard were found between 2014 and 2020 by a single detectorist, who together with the landowner has requested anonymity, hence the find currently being described only as coming from ‘West Norfolk’.

A Coroner’s inquest is currently being held to determine whether the find constitutes Treasure under the terms of the Treasure Act (1996). If any two or more coins contain more than 10% of precious metal and are confirmed by experts to be more than 300 years old, they will be declared Treasure and will be the property of the Crown. Typically, the government only claims the find if an accredited museum wishes to acquire it, and is in a position to pay a reward equivalent to the full market value.

In this case the anonymous finder reported all of his finds to the appropriate authorities. However, ten of the coins were found by a second detectorist, David Cockle, who had permission from the landowner to detect in the same field.

Mr Cockle, who at the time was a serving policeman, failed to report his discovery and instead attempted to sell his coins, pretending that they were single finds from a number of different sites. Mr Cockle’s deception was uncovered, and in 2017 he was found guilty of theft and sentenced to 16 months in prison, as well as being dismissed from the police.

“The West Norfolk hoard is a really remarkable find, which will provide a fascinating counterpart to Sutton Hoo at the other end of the kingdom of East Anglia,” says Helen Geake, Finds Liaison Officer for Norfolk.

“It underlines the value of metal-detected evidence in helping reconstruct the earliest history of England, but also shows how vulnerable these objects are to irresponsible collectors and the antiquities trade.”

The administration of the Treasure process is undertaken at the British Museum who also manage the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) in England (in Wales it comes under the management of Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales).

Thousands of archaeological objects, many of them found by members of the public, are logged every year with the Finds Liaison Officers of the PAS to improve our understanding of the past. They can be explored at www.finds.org.uk

By Richard Moss.

#England’s Largest Anglo Saxon Gold Coin Hoard Found#archeology#metal detector#history#history news#ancient civilizations#treasure#gold#gold coins#collectable coins#jewelry

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Egyptian Widow, 19??, Museum of the Netherlands

The Frisian artist Alma-Tadema was a great success in England, where he was even knighted. His representations of ancient Egyptian, Greek and Roman scenes made him one of the most popular 19th-century painters. In this picture, full of archaeological details, a woman is mourning beside the inner mummy case containing the body of her husband. His sarcophagus stands at left, while priests and singers lament the departed.

http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.5776

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

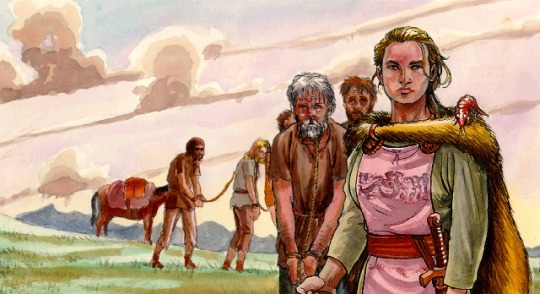

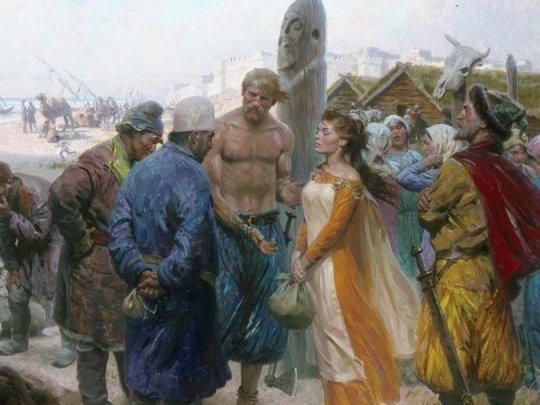

Thralls and the Norseman

Thralls

Etymology: Thrall (Old Norse/Icelandic: þræll, Faroese: trælur, Norwegian: trell, Danish: træl, Swedish: träl)[1] was a slave or serf in Scandinavian lands during the Viking Age. The corresponding term in Old English was þēow. The status of slave (þræll, þēow) contrasts with that of the freeman (karl, ceorl) and the nobleman (jarl, eorl). The Middle Latin rendition of the term in early Germanic law is servus.

The Thrall represents the lowest of the three-tiered social order of the Germanic peoples, noblemen, freemen and slaves, in Old Norse jarl, karl and þræll (c.f. Rígsþula), in Old English corresponding to eorl, ceorl and þēow, in Old Frisian etheling, friling, lēt, etc.

The division is of importance in the Germanic law codes, which make special provisions for slaves, who were property and could be bought and sold, but they also enjoyed some degree of protection under the law.

The death of a freeman was compensated by a weregild, usually calculated at 200 solidi (shillings) for a freeman, the death of a slave was treated as loss of property to his owner and compensated depending on the value of the worker.

Where were Thralls from? The thralls were mainly Franks, Anglo-Saxons, and Celts. Many Irish slaves were used in expeditions for the colonization of Iceland. The Norse also took Baltic, Slavic and Spaniard slaves. The Vikings kept some slaves as servants and sold most captives in the Byzantine or Islamic markets

Interesting factoids:

The Slavic peoples of Eastern Europe were for a long period an obvious target for European and Nordic slave traders. It is from this area that the term “slave” originates.

Slaves/Thralls were amongst the most important commodities traded by the Vikings. They acquired slaves primarily on their expeditions to Eastern Europe and the British Isles.

Thralls could also obtain Viking slaves at home, as crimes like murder and thievery were punished with slavery. For example, a woman who stole could be punished by being forced to become her victim’s slave.

Slave trading also existed before the Viking period, but with the numerous territories that the Vikings conquered and their extensive trading networks, slavery could now operate within a system and bring them great wealth.

Written sources and legal texts in particular inform us about the slave trade, but the slaves themselves have left few traces behind. However, a few archaeological discoveries have been helpful in this respect, such as burials in which slaves were forced to follow their owners in death.

Thralls usually provided unskilled labor in the Viking Age, performing the heaviest and nastiest labor, building walls, spreading manure, pig and goat herding, and peat digging. In time, favored male thralls could become overseers, bailiffs, or personal valets.

The female thralls ground corn and salt, milking, churning, and washing, with some seeing occasional service as bed-slaves, nannies, or personal maids. Both sexes also took part in the "lighter" tasks of running a farmstead, including the spring pasturing of livestock, ploughing, planting, harvesting, slaughtering, and spinning (both sexes).

LINKS:

Thralls

What exactly is a Thrall?

Slave and Thralls

Little known roles of Slavery in Viking Society

Slavery and Thralldom

What is a Thrall?

Irish enslavement during the Viking Age (PDF)

Viking Society: Nobles, Medieval Freemen, Slaves

Role of Women in Viking Society

Vikings and Misconceptions

Thralls and the Hierarchy

As most people know, the Vikings had a habit of carrying off slaves. Given the genetics of Iceland and the nature of the people who settled it, it’s possible that a large percentage of the first women on Iceland were taken there as slaves.

Based on the mitochondrial DNA, which is only passed down in the female line, we know that over half of the female settlers were Celtic, meaning they came from Ireland, Scotland, and the northwestern islands of Britain.

Aside from self-redemption (purchasing one's own freedom), thralls could be freed by their owners as a gift (especially for long and devoted service), or they could be bought free by a third party. The granting of a thrall's freedom was an occasion for much ceremony, as the former thrall had no existence as a human in the eyes of the law until his cash redemption. In most parts of Scandinavia, the freedman was adopted into his master's family, and thus given the rights and duties of any other free person in the law, including testifying or prosecuting cases at law.

Especially attractive slave girls and female prisoners of war (of a high status) could live in good conditions and achieve respect. The same applied to male slaves who were particularly skilled craftsmen.

FRILLAS: (Old Norse friðla (a mistress, a harlot, a concubine ”), usually contracted as frilla. Cognate with Danish frille, confer friðill.)

Although concubines have often been referred to as “sex slave,” the use of the term is in general a bit of an overstatement. To be sure, there were probably men who raped and dominated unfairly, but for most people, the process of choosing a Frilla is not so simply summed up. Although some have stated that concubines were all of an inferior status, in Iceland at least this not always true:

Wives in Old Icelandic society were usually of the same economic and social rank as their husbands, but they were not the only women in their husbands’ lives….In the earliest period after the settlement, many married men, whether farmers or chieftains, kept slave women as concubines.

These women were called frillur (sing. frilla). As slavery died out in the eleventh century, men continued to maintain frillur. No longer slaves, these women came from families of equal status as well as form, more commonly, from families of lower station than those of the men with whom they lived. Becoming a concubine of a prominent man often increased a woman’s status and influenced between her siblings and kinsmen, and chieftains often treated male kinsmen of their concubines as trusted brothers-in-law. In some instance’s concubines had wider latitude to act in their own interest than they might have had in poor marriage. An Icelandic folk saying of goes, ‘Better a good man’s frillur than married badly.’

University of Oslo DNA evidence suggests women accompanied men on raiding trips

Study hints men were family-orientated and children may have come too

Women played helped to establish new settlements, trade and had children

Study questions stereotype of raping and pillaging warriors

LINKS:

Viking may have taken to sea to find Slave and Women

Vikings: Marriage, Sex and Slaves

What we know about Vikings and Slaves

Viking DNA and Raids

Viking Practices in Regards to Women

VIDEOS:

Social Classes in Viking Society

The Viking Slave Trade

Viking Anglo-Saxon Slave Trade

Women in Viking Age Scandinavia

#norse culture#norse history#writers research#writers room#writer resources#viking research for writers

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

Five Fics Friday: January 3, 2020

Happy new year everyone!!! Nothing really new this week because of the crazy B.S. week I’ve had, so I didn’t really feel up to starting anything new :( But, I’ll give you the fic I am currently re-reading this week, a couple new bookmarks, a and a couple Anything Goes fics :) Hope you enjoy the first 5FF of 2020! <3

---------

CURRENTLY RE-READING

The Horse and his Doctor by khorazir (T, 129,003 w., 13 Ch. || Horse / Vet AU || Magical Realism, Horses, Vet John, Horse Sherlock, Implied Alcoholism) – Invalided after a run in with a poacher in Siberia, veterinary surgeon John Watson finds it difficult to acclimatise to the mundanity of London life. Things change when a friend invites him along to a local animal shelter and he meets their latest acquisition, a trouble-making Frisian with the strangest eyes and even stranger quirks John has ever encountered in a horse.

NEW WiP MFL’s THIS WEEK

Thermocline by J_Baillier (M, 2,139+ w. 1/12 Ch. || WiP || Scuba Diving AU || Adventure, Angst, Hurt/Comfort, Marine Archaeology, Asexual Sherlock, Horny John, Academia, Slow Burn, Scuba/Wreck/Technical Diving) – John "Five Oceans" Watson — technical dive instructor, dive accident analyst and weapon of mass seduction — meets recluse professor of maritime archaeology Holmes. As they head out to a remote archipelago off the coast of Guatemala to study and film its shipwrecks for a documentary, will sparks fly or fizzle out?

The Man in the Iron Collar by Mamaorion (G, 44,080+ w., 12/? Ch. || WiP || 1800′s Steampunk England AU || Magical Realism, Circus, Soulmates, Murder Mystery, Prophecy, Healer John, Mind Reader Sherlock, Slow Burn, Magic, Bullying, Alternating POV) – The magical worlds of Faerie and humans have been separated by the Wall for over 1,000 years, but halfbloods, half-Faerie/half-human hybrids, continue to trickle into this magical, steampunky 19th century England. Healer Captain John Watson discovers a telepathic halfblood imprisoned in a traveling circus. While he tries to unravel his mysterious connection to this wild man, the two are pulled into London's halfblood underworld. A wave of serial murders will take them beyond the Wall and into the ancient battle between humans and Faerie.

ANYTHING GOES

Nothing to Make a Song About by emmagrant01 (E, 36,833 w., 10 Ch. || Post-TRF, First Time, Reunion, Jealous John, Pining Sherlock, Romance, Angst with Happy Ending, Sherlock Has a Boyfriend) – When Sherlock returned from his faked death, John could not forgive him for the deception and broke off their friendship. Ten years later, John returns to London in search of yet another new beginning. Sherlock, not surprisingly, is waiting.

Eyes Up, Heels Down by CodenameMeretricious (E, 107,845 w., 43 Ch. || Sports Equestrian AU || Fluff, Angst, Humour, Rider!Sherlock, Groomer!John, Show Jumping, Slow Burn, Happy Ending) – Sherlock is a top eventing rider currently training at Baker Farms. John is the new groom who's been told to steer clear of the surly rider and his horses. Part 1 of Baker Farms

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Little Talk on Methodology

So, after our first talk, it is time to organise our stuff.

Our basic tool here is the Reconstructionist methodology. This is an ambiguous term, but we will understand and use it mainly in three different ways:

1. As a critical study of old written texts and modern scholar discussions on these texts and archaeological findings in order to make educated guesses on the nature of the pre-Christian beliefs of the Early English peoples;

2. As an attitude towards this information which involves empirically recreating some patterns of behaviour (both ritual and ethics) inspired by the information acquired;

3. As an aim of understanding and incorporating, through these studies and practical experiments, the underlying world view of the Early English peoples inasmuch as possible.

However, I know that fully perceive and conceive the world as the Early English peoples did is impossible. What I am gonna do is de-Christianise our perception as much as I can.

I know that the process of de-Christianisation cannot be done in a single generation, there are too much unconscious stuff that we do not even notice that is a legacy from Abrahamic religions today. Not even Christendom erased Heathendom in a single day.

You may have noticed that I deliberately avoid the term “Anglo-Saxon”. This is because there is too much discussion on how this term is ambiguous, having a racist flavour in the US and because I myself do not consider it quite fair with the post-Roman settlers of Britain.

Jutes, Frisians and Franks are among the other main raiding peoples who settled in Britain besides the Angles and Saxons from the 6th century onwards, and while the Frisians and Franks may have been in a small number, the Jutes were the first Germanic peoples to stablish a kingdom in Britain.

Not to mention Brythons among the Saxons and Scots among the Angles that were in no way altogether cleansed. Did you ever realise that all the kings in the first generations of the Anglo-Saxons’ royal houses had Celtic names?

So, the term “Germano-British” sound much more accurate to my ears, but I sincerely doubt that it is going to be widely used some day. I am going to use the term “Early English” despite finding it a bit inappropriate.

However all those terms fall into the same mistake of reducing all the Germanic speaking peoples to a single group. Historically speaking, there was no unified “Anglo-Saxon Heathendom”, rather many diverse and local Germanic-rooted world views that certainly differed from one another as can be exemplified by the position of Wōden as the begetter among Anglian (and perhaps the Jutish) kingdoms while Seaxnēat had this position in Essex (and presumably other Saxon kingdoms before the efforts of unification of Alfred the Great and his offspring).

I don’t think that the Anglian, Saxon, Jutish, Frisian and Frankish practices were actually hardly different in Britain though. It is more a question of subtleties.

What I cannot ignore is that these differences existed and our lack of sources somewhat compel us to gather in the same pot all the data about the Germanic folk religions of Britain. In Early English times there was no single “Heathendom” but “Heathendoms” in the plural form.

While most Fyrnsidu (Old English Custom) groups do not pay much heed to the later fairy tales of England, we are going to go a step further and, as in the case of Norse and Continental Heathendoms, very critically analyse what can be useful in our task.

I’m aware that folk English customs of medieval and early modern times are very mixed with many many influences, so we are going to make it carefully.

An ending note: I am not willing to give long speeches when it is not needed. I think that a straight and objective short talk is better.

#Heathenry#Heathendom#Heathenship#Heathen#Pagan#Paganism#Anglo-Saxon#English#pre-Christian#worldview#Animism#Fyrnsidu#Theodism#polytheism#reconstructionism#reconstruction

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

European Christianization and the Eternal Fate of Pagan Ancestors

”The relationship between the living and dead members of their clan has long been seen as an essential one in early medieval society. The dead constituted an age class that continued to have a role and to exercise rights in society. Archaeologists have suggested that the rich grave goods in burials of the ate fifth and sixth centuries were evidence of this importance in Reihengräberzivilization, in which ancestors played the role of intermediaries between the clans and tribes (Stämme) and the gods. Kurt Böhner and others have thus suggested that Christianity, which greatly lessens the role of the dead, must have had a fundamental impact on the place of the dead in in Merovingian society: “The profound change that Christianity brought with it is shown most clearly with relationships with the dead. Although these were once ancestors of many clans and tribes in which they lived on and enjoyed divine or quasi-divine veneration, they now entered the eternality of Christ.” As evidence of this essential transformation in relationship between the living and their ancestors, Böhner cites the famous passage from the Vita S. Vulframni in which the Frisian duke Radbod, about to be baptized, asked Wulfram, the bishop of Sens, whether there were many Frisian kings and princes in heaven or in hell. Wulfram answered that, since these praedecessores had not been baptized, they were surely in hell. Hearing this pronouncement, the duke determined not to be baptized, saying that he could not do without the company of his predecessors. This text, whose importance for historical ethnography Herwig Wolfram has emphasized, seems however to contradict other archaeological evidence which, as we shall see, places in doubt Böhner’s interpretation both of the process of Christianization and of the account in the Vita Vulframni.

Radbod died in 719 and, it can be assumed, joined his damned ancestors. Around the same time or shortly before in the Rhineland near Alzey, Frankish nobles were founding a funerary chapel that served to preserve the memory of their pagan ancestors and, in a functional sense, to Christianize them retroactively. The church in question was Flonheim, and the careful archaeological study of the site by Hermann Ament suggests that the theological response to Radbod’s question presents only part of the eighth century reality.

On December 29, 1876, the parish of Flonheim was destroyed by fire. During reconstruction between 1883 and 1885 it was discovered that the church stood on the foundations of a much older building, within which were found ten Frankish burials. The oldest portion of the church was a tower, the upper part of which was Gothic; the lower, Romanesque of ca. 1100. The foundations of the Romanesque portions of the tower, a crypt, were older still; and directly under this oldest portion of the old church, was a particularly rich Frankish burial. Ament’s examination of grave goods and his reexamination of the nineteenth-century report of the excavations demonstrated that the graves were part of a larger row cemetery, traces of which had been found in the 1950s elsewhere in the village. Moreover, the ten graves appear to be those members of a wealthy clan. That in the Merovingian period a family would erect a mortuary chapel in which to bury its members would hardly be remarkable; examples are common, particularly even earlier ones in the more Romanized areas of Europe. What is remarkable, however, is that Ament’s dating of the burials, particularly of grave 5, the one directly under the tower, is so early that the burials must predate the erection of the church (first mentioned in 764/767) and, in the case of grave 5, the conversion of Clovis. Ament compares this grave -in its depth (greater than the others at Flonheim), in its furnishings, and in its relation to other graves- to grave 319 at Lavoye. The rich furnishings of grave 5 include a famous golden-handled sword and other weapons and ornaments which both in their forms and variety argue for a date conclusively for a date contemporary with the tomb of Childeric (481). Ament sees grave 5 as a founder’s burial, like that at Lavoye. Around it, in the sixth and early seventh centuries, other clan members were buried. When the chapel was built, the importance of this founder’s burial was still recalled, and its builders included the other clan graves within the confines of its walls. The erection of a chapel over the graves of a clan and the particular position given to the clearly pre-Christian burial both strongly suggest that the continuity between pre-Christian and Christian members was not broken by baptism. In fact, on a physical, structural level, the founder was given a burial infra ecclesia after the fact, thus including him in the new Christianized clan tradition. Ament has compared the situation at Flonheim to those at Arlon, Speiz-Eingien, Morken, and Beckum and suggests that these other Merovingian churches containing Frankish burials may well be similar to Flonheim; for the chapels also appear to postdate the earliest burials.

The American archaeologist Bailey Young has compared these apparently ex post facto Christianizations to observations of Detler Ellmers on Swedish cemeteries and suggests that the practice of assimilating pre-Christian ancestors into the Christian cult of the dead may be detected there as well. In Sweden, with the coming of Christianity, churches were generally built near the preexisting sepulchers of prominent families, and the last furnished burials are therefore older than the actual cemeteries. Elsewhere, pagan remains were moved into Christian burial places. The most famous Christian reburial in the North is that of the Dane Harold Bluetooth’s pagan parents Gorm and Thyre at Jelling. Harold first buried his parents in a wooden chamber covered by a large mound surrounded by standing stones in an outline of a ship, giving them a traditional pagan burial. After his conversion around 960, he had his parents’ remains removed to a church. Excavations of the present stone church (ca. 1100) indicate three previous wooden churches and a large, centrally placed grave containing the disjointed remains of a man and a woman obviously reburied there after the disarticulation of the skeletons. Harold’s runestone explicitly announces that the monuments he created were dedicated “to his father Gorm and his mother Thyre,” although it goes on to say that Harold “made the Danes Christian.”

In both Frankish and Scandinavian situations, the archaeological evidence seems to contradict the explicit statement of Wulfram. How is the historian to resolve this contradiction? I would suggest that it arises from two sources. The first is the difference noted above between the intellectualized articulation of belief by clerical elite and the actual societal practice, lay and clerical. The second is the way the specific circumstances of Radbod’s aborted conversion color both the question and the response, making them part of a discussion of salvation in modern Christian terms, when the real issue is ethnicity and hegemony in eighth century Frankish terms.

In the case of Flonheim and similar burials, the meaning of the construction of a Christian church over a pagan tomb is implicit: the ancestors have been conjoined in the new cult as they were in the old. Conversion is not an individual, but a collective, act that involves the entire clan and people, a fact long recognized about two groups of Franks - those of Clovis’s generation and their descendants. The collective nature of conversion implicitly applies to a third group of Franks as well, their ancestors. Although Gallo-Roman authors like Gregory of Tours have emphasized Clovis’s conversion, that does not mean the Franks had lost respect for or interest in their pre-Christian ancestry. Witness the literature of Merovingian Frankish genealogy, the Liber historiae Francorum, among others. Retroactive conversion is not articulated; indeed, it would be difficult to reconcile that orthodox Christianity. But in the symbolic and ritual structure that solidified and expressed the values of Frankish-Christian civilization, a place was found for their ancestors. Here, as in the example of the ritual humiliation of the saints I mentioned earlier, the physical juxtaposition presents a meaning in a Wittgensteinian sense which was apparently accepted by the lay founders of the church at Flonheim as well as by its clerics. Perhaps, although we cannot be sure of how much they knew of its origins, even the monks at Lorsch, to whom the church was given in the 760s, perceived this meaning.

Thus the Franks of Flonheim, pagan and Christian, could keep each other company in the next life but not, apparently, Radbod and his pagan ancestors. It is tempting to cast this distinction in terms of the supposed two stages of conversion, the first represented by a maximum accommodation to pagan tradition; the second (and this being the case with Radbod), an insistence on an inner meaning of Christianity. In fact, this approach will hardly suffice. Frisia was, in the early eighth century, hardly into a second phase of conversion; it was at the first stage of a process that would take generations. Rather, we should consider the specific context of the efforts to convert Radbod and his Frisians. Wulfram’s contact with the duke was part of the Frankish effort to subjugate the Frisians, an effort in which conversion was specifically conversion to Frankish Christianity. After Pepin II defeated Radbod in 694, he sent Wilibrord to convert Radbod and his people. Wulfram’s efforts were part of this mission. Pepin’s intention was specifically to establish a Frankish political and cultural basis in order to pacify the region. Conversion and baptism at the hand of a Frankish bishop would have meant, then, the acceptance of a specifically Frankish ethnic identity and the rejection of Frisian autonomous traditions, political and cultural. Radbod would really have cut himself off from his ancestors, but not merely by being assured of heaven while they languished in hell; for he would have become, in a real sense, a Frank. A similar break with their ancestors was demanded of the Saxons during the eighth century. It is hardly happenstance that the earliest condemnations of traditional Germanic burial sites in favor of church cemeteries was specifically directed at Saxon Christians: “We order that the bodies of Christian Saxons be taken to the church cemeteries and not to the burial mounds of the pagans.” Likewise, the famous Indiculus superstitionum was directed specifically at those “sacrileges at the tombs of the dead” performed by the Saxons. In the case of both the Frisians and of the Saxons, the bonds uniting the conquered people to their independent ancestry had to be broken because they were a source of anti-Frankish ethnic and political identity, not simply because they were pagan in a narrow religious sense. In the entirely Frankish contexts of Flonheim, Arlon, Spiez-Einigen, and Morken, though, conversion did not mean the rejection of a cultural and political tradition. It meant instead the confirmation of tradition through the acceptance of a new and more powerful victory-giver, Christ. The benefits of such a conversion could be shared with the past as well as with the future.

- Patrick J. Geary (Living with the Dead in the Middle Ages, pages 35-41)

#Mass conversion#Christianity#Salvation#history#Merovingians#Frisia#Living with the Dead#Anglo Saxon#Saint Wulfram#Radbod of Frisia

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Birka’s warrior woman

This grave was found on Birka (Björko) in 1878. The grave contained human remains, remains from two horses, bowls, weaponry, a shield(boss), a chess game and saddle stirrups. The burial room was built in wood. Most likely the person was buried seated, with the bones collapsing on themselves. Some remains of textile were found.

The assumption that the person was a man was quickly made and the “high status burial of a Viking warrior” was often cited in research.

It would take until 2017 when both osteological and genetic testing proved the person was in fact a woman. To this day it is the only genetically and archaeologically proven female warrior from the Viking age.

The reason I say genetically AND archaeologically is because it is assumed that gender was a very loose concept in the Germanic age. Biological gender wasn’t necessarily denied, but there are indications that people would take on “the role” of the other gender. A woman could “step up” as a man’s son, as seen in blood feud tales where the patriarch is killed, but if there is no son to avenge him, a woman would “take up the role” and set out, armed for revenge.

Biologically male individuals have been found with “female” attributes such as beads, pendants and certain decoration styles.

From the limited amount of research there is, it seems possible that cross-dressing, gender fluidity and gender role exchange were very normal before mass christianization.

Excavated by: Hjalmar Stolpe

Found in: Birka, Björko, Ekerö - Sweden

Drawing by: Hjalmar Stolpe

#frankish#merovingian#viking archaeology#archaeology#carolingian#charlemagne#field archaeology#viking mythology#merovingian archaeology#germanic mythology#valkyrie#Walküre#Wagner#richard wagner#norse mythology#anglo saxon#field archaeologist#frisian#viking#vikings#germanic#germanic folklore#germanic archaeology#odin#wodan#anglo saxon archaeology#history#jewelry#norse

294 notes

·

View notes

Text

An illustration of the first Roman fort in Velsen. Archaeological evidence was first uncovered in 1945 by schoolchildren who found shards of pottery in an abandoned German anti-tank trench. Photograph: Graham Sumner

Large Roman Fort Built By Caligula Discovered Near Amsterdam

Fortified camp for thousands of soldiers thought to have been used by Emperor Claudius during conquest of Britain in AD43

— Daniel Boffey in Brussels | Sunday 26 December 2021

A large Roman fort believed to have played a key role in the successful invasion of Britain in AD43 has been discovered on the Dutch coast.

A Roman legion of “several thousand” battle-ready soldiers was stationed in Velsen, 20 miles from Amsterdam, on the banks of the Oer-IJ, a tributary of the Rhine, research suggests.

Dr Arjen Bosman, the archaeologist behind the findings, said the evidence pointed to Velsen, or Flevum in Latin, having been the empire’s most northernly castra (fortress) built to keep a Germanic tribe, known as the Chauci, at bay as the invading Roman forces prepared to cross from Boulogne in France to England’s southern beaches.

The fortified camp appears to have been established by Emperor Caligula (AD12 to AD41) in preparation for his failed attempt to take Britannia in about AD40, but was then successfully developed and exploited by his successor, Claudius, for his own invasion in AD43.

Bosman said: “We know for sure Caligula was in the Netherlands as there are markings on wooden wine barrels with the initials of the emperor burnt in, suggesting that these came from the imperial court.

“What Caligula came to do were the preparations for invading England – to have the same kind of military achievement as Julius Caesar – but to invade and remain there. He couldn’t finish the job as he was killed in AD41 and Claudius took over where he left off in AD43.

Roman emperor Caligula is thought to have established the fort at Velsen. Photograph: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

“We have found wooden planks underneath the watchtower, or the gate of the fort, and this is the phase just before the invasion of England. The wooden plank has been dated in the winter of AD42/43. That is a lovely date. I jumped in the air when I heard it.”

Claudius’s invading forces, untouched by the Germanic tribes, made their landing in Kent and by the summer of AD43 the emperor was confident enough to travel to Britain, entering Camulodunum (Colchester) in triumph to receive the submission of 12 chieftains.

Within three years, the Romans had claimed the whole of Britain as part of their empire.

Bosman said: “The main force came from Boulogne and Calais, but the northern flank of that attack had to be covered and it was covered by the fort in Velsen. The Germanic threat comes up in Roman literature several times.

“It was an early warning system to the troops in France. It didn’t matter what the Germanic tribes put in the field as there was a legion there.”

The first evidence of a Roman fort in Velsen, North Holland, had been uncovered in 1945 by schoolchildren who found shards of pottery in an abandoned German anti-tank trench.

Research was undertaken in the 1950s during the building of the Velsertunnel, under the Nordzeekanaal, and archaeological excavations took place in the 1960s and 70s.

In 1997, Bosman’s discovery of Roman ditches in three places, and a wall and a gate were thought sufficient evidence for the area to become a state protected archaeological site.

But at this stage the Velsen camp, identified as having been used between AD39 and AD47, was thought to have been small.

This theory was complemented by the discovery in 1972 of an earlier fort, known as Velsen 1, which is believed to have been in operation from AD15 to AD30. A thoroughgoing excavation of that site found it had been abandoned following the revolt of the Frisians, the Germanic ethnic group indigenous to the coastal regions of the Netherlands. Archaeologists discovered human remains in some former wells, a tactic used by retreating Romans to poison the waters.

The existence of the two forts within a few hundred metres of each other had led researchers to believe for decades that they were both likely to have been mere castellum, minor military camps of just one or two hectares.

It was only in November, through piecing together features of the later Veslen fort that were noted in the 1960s and 70s, but not recognised at the time as Roman, and taking into account his own archaeological findings over the last quarter of a century, that a new understanding was reached.

“It is not one or two hectares like the first fort in Velsen, but at least 11 hectares,” Bosman said. “We always thought it was the same size but that is not true. It was a legionary fortress and that’s something completely different.”

Bosman added: “Up to this year I wondered about the number of finds at Velsen 2, a lot of military material, a lot of weapons, long daggers, javelins, far more than we found on Velsen 1.

“And we know there was a battle at Velsen 1, and on a battlefield you find weapons. The number of weapons at Velsen 2 can only be explained in a legionary context. Several thousand men were occupying this fort.

“At 11 hectares, this would not be a complete fort for a full legion of 5,000 to 6,000 men but we don’t where it ends in the north and so it could have been larger.”

The Velsen 2 fort was abandoned in AD47 after Claudius ordered all his troops to retreat behind the Rhine. Roman rule of Britain ended around AD410 as the empire began to collapse in response to internal fighting and the ever-growing threats from Germanic tribes.

— The Guardian USA

0 notes

Text

15 best Islands in Europe

Deciding where to go during the summer holidays is often a dilemma. Give the old continent a chance and explore one of the beautiful islands in Europe. Enjoy tropical coastlines, cliffs, and picturesque villages. Here we leave you a selection of the 10 best islands to visit in Europe during the summer.

Weather Islands, Sweden

Sweden may not be the first country that comes to mind when you think of European islands. However, you should give it a try, you may be pleasantly surprised. Sweden has more than 220,000 islands, which include atolls and small islets.

Among so many options, the best of all is Weather Islands, an archipelago known in Sweden as Väderöarna. This set of beautiful islands is located at the westernmost point of the country. The place exhibits breathtaking beauty and endless tranquility. Many of the islands are uninhabited, therefore you can enjoy long nature walks, lazy days on the beach, and relaxing nights on the peaceful sandy atolls. Ferries leave on the mainland from Fjällbacka and from Hamburgsund, near Gothenburg.

Flores, Portugal

Flores is one of the islands of the western group of the Azores, Portugal. If you are a nature lover you will immediately fall in love with this island. It has deep valleys, high mountains, and the entire territory is covered with thousands of hydrangeas during the summer. Flores is accessed by air and ideal for boating, hiking, surfing, birds, and whales. Without a doubt, this is the place you need if you want to connect with nature enjoying secluded beaches and lush landscapes.

Andros, Greece

Even the most famous Greek archipelago has some islands that are still unknown to many. Andros is part of the Cyclades and is a green paradise that is actually closer to the Attica Peninsula than its sister islands. Andros has crystal clear waters, fine sand and beautiful valleys, so it is an excellent option for hikers thanks to its extensive network of trails. In addition, it has very beautiful typical towns where there are many interesting places to visit. The truth is, Andros has nothing to envy to other more popular islands in Greece. This is one of the best-kept secrets.

Porquerolles island, France

The Island of Porquerolles is one of the three Islands of Hyères. It is located opposite the French Riviera, between Cannes and Marseille. The island is small but it has beautiful beaches, surrounded by eucalyptus, pine, and cliffs. Porquerolles has only one town, dating back to 1820, and it is a popular destination for excursions with family and friends who enjoy the sea and explore the island, either by bike or on foot. You can book a room at the luxurious Hotel Le Mas du Langoustier or do what most people prefer, a round trip.

Elba, Italy

Elba is an island known for being the place where Napoleon was sent into exile. This territory exhibits beaches of golden sand, crystal clear waters, lots of vegetation and cliffs. A highly recommended activity is to visit Tenuta La Chiusa, the oldest winery on the island, to taste delicious wine.

Cíes, Spain

The Cíes Islands are a group of islands located off the coast of Pontevedra, in Galicia. The archipelago can be reached by ferry from Vigo. The Cíes is considered the jewel of Galicia and are known as the Galician Caribbean or Galician Seychelles. You must visit Playa de Rodas, the longest, where the ferry docks during the summer. Also, this place is very famous among hikers and bird watchers. If you are looking for serene beaches, relaxation and abundant nature, then the Cíes Islands are your best option.

Sylt, Germany

Among the islands of Germany, the best option is Sylt, the largest of the Frisian Islands. It is well known for its beaches, resorts, and laid-back lifestyle. Sylt is connected to the mainland by a carriageway that is used by trains from Hamburg. There are also flights available during the summer. You will be impressed with its virgin beaches and its picturesque towns.

Barra, Scotland

Aerial drone view of Porto da Barra beach in Salvador Bahia Brazil

Scotland certainly deserves a place in this selection. Thanks to its charming atmosphere, the island of Barra is the best option. Explore the fantastic scenery by bike or on foot. It should be noted that Kisimul Castle is a mandatory visit. Also, you can’t stop trying the delicious seafood served on this island. You will be so delighted that when you return home you will count the days to return to this Scottish island.

Vis, Croatia

Rays of traffic lights on Gran via street, main shopping street in Madrid at night. Spain, Europe.

Vis is an island located in the Adriatic Sea and is one of the more than 700 islands in Croatia. Vis is considered one of the best islands in the country because it has maintained its authentic charm. In addition, it is a meeting place for seafood lovers and wine enthusiasts.

Capri, Italy

View from the boat on Capri island coast with famous caves and vegetation. Italy. Sunny day. Copy space.