#dori's younger cousin series

Text

My little cousin (15) is watching atla for the first time. She's just started season 2. Here are her opinions of the characters so far:

Aang: "bald. Very bald."

Katara: "bad bitches do it so well"

Sokka: "attractive but in an older cousin type of way" (??????)

Zuko: "also bald. Angry and bald. Although he changed his hair now so just angry i guess."

Azula: "i will use my right to remain silent."

Uncle Iroh: "how old is he? Like 80? I'm gonna say 80."

Admiral Zhao: "musty dusty crusty" her exact words.

Yue: "she's coming back right?" Oh sweet summer child.

Jet: "all i remember is that stupid wheat thing in his mouth."

Haru: "who?"

King Bumi: "he looks like his mother got electrocuted when he was in the womb"

Suki and the Kyoshi Warriors: "all power to them bc i would not stand a chance fighting in a heavy dress"

#she's a very opinionated 15yr old#i can't tell if she's intimidated by azula or attracted to her#also i did tell her azula is supposed to be 14 and she did not believe me lol#avatar the last airbender#atla#avatar#aang#avatar aang#sokka#zuko#prince zuko#katara#azula#princess azula#iroh#uncle iroh#dori's younger cousin series

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

prologue, the burning sky — star wars.

series masterlist | writing masterlist | askbox

─── summary: prologue; the burning sky. some tragedies will always happen, like a story you've always been unable to rewrite. but you still try.

─── warnings: star wars au, canon divergent. character death, vehicle accidents, blood & injury (nondescriptive), child loss, grieving.

─── notes: this is the prologue to a series i'll be posting following my ocs. this is a whole rewrite of the star wars sequel trilogy featuring ocs and focusing largely on family, grief, what you would do / how far you would go for family, haunting the narrative. the whole point of this story is family. are there love interests?? yes. but the core of it is 'what would you for / because of family?' you don't have to like this, but if i receive any rude feedback i'll just block you because the star wars fandom already fuckin terrifies me, let me just post my sad shit.

─── word count: 2.5k.

━━ the beginning.

The sun rises, as it always does, a burning orb cresting over the horizon, painting streaks of pink across the silvery sky. Dawn leaks in through the windows of a newly-broken home, reaching across the room with long yellow fingers to raise a house full of heartache.

Dory wakes with itchy, saltwater eyes.

For a moment, she wonders why the skin around her eyes feels tight and sore, her nostrils stinging. She winces as the sunlight bleeds through the blinds, casting the room in a happy yellow glow. Her stomach twists violently as she remembers what happened the night before, each painful memory crashing back into her mind; bile burns the back of her throat, and she has to choke it back down.

A sob racks her shoulders, sudden and vicious. She presses a hand to her mouth, trying to keep it in as tears rise in her eyes again, blurring her bedroom into one sun-drenched mess.

Something heavy lays curled at the foot of her bed. Blinking her tears away, she peers over the edge of the covers, finding her younger cousin Marya sleeping there. She must've crept in in the middle of the night.

Gently, she nudges Mare, and the younger girl stirs. Dory pulls back the covers and pats the space beside her. Blonde hair stuck to her face, mascara smudged beneath her eyes, Mare pushes herself up onto her elbows and crawls into bed beside her cousin. Dory pulls the blankets back up over their heads, and wraps her arms around Mare, pulling her cousin as close as she can.

"My room was too quiet," Mare whispers into the fabric of Dory's shirt, fingers curled and clinging tightly to it. "I wanted to stay up to hear any news, but I couldn't stay in there."

"That's alright." Dory's voice comes out cracked; she runs her fingers through the tangled strands of her cousin's hair, trying not to wince as Mare hugs her, pressing into the bruises that are spread across Dory's torso like a gruesome abstract painting.

She has never been the most affectionate person, not even to her own sister ━ but things can change in the blink of an eye, and people get lost when you thought they would live forever, and things bleed when they aren't supposed to, and Dory just wants to hold onto Mare for as long as she can before she has to let go again, no matter the pain it causes.

"Mum hasn't slept, has she, Mare?" asks Dory.

Mare shakes her head a little. "Not since I last checked. She was sitting in the kitchen when I left my room earlier... my mum was sitting with her. Uncle Luke went to be with mama in case something happened with Rion, and I don't think they've come back yet..."

Dory swallows at the mention of her other cousin.

When she stumbled in last night, stained with blood and reeking of smoke, with Mare hanging onto her arm, her father had folded them both into his arms. He'd sat with her as she screamed and raged for hours, held her when she sobbed until there were no tears left, and never said a word.

No one else had been there waiting for them; her mother had gone straight to the medical centre with Aunt Ashka and Aunt Leia when she heard what happened, and only returned in the early hours of the morning, pale as a ghost and clinging to Ashka as if she were the only thing keeping her standing.

Dory had never seen her parents like that before. Yve Cybele was the strongest woman in the galaxy, and Han Solo was always smiling, laughing as if everything were easy.

Last night, though, Dory watched her mother shatter into a million pieces, and her father had no way of pressing them back together again.

Last night, her sister died.

When Dory closes her eyes against the sunlight, it all comes back to her in sharp, jarring flashes.

She recalls the events leading up to the accident with perfect clarity; she, her parents and her little sister, Clarya, had come to visit their family for a month, as they had done every year for as long as Dory could remember. The visit, at least, had gone reasonably smoothly ━ she always worried about growing apart from her cousins, when they spent so much of the year on separate ends of the galaxy. She and Rion, especially; Rion had been absent their last few visits, training at their uncle's re-established Jedi temple, and this was the first she and Clarya had seen him in such a long time.

But it had been fine. Clarya and Marya, both fourteen, had stuck together like glue from the moment they arrived. Dory and Rion, too, had gotten over their initial awkwardness and bonded once more. Rion, one year younger than Dory at seventeen, had delighted in showing off all the things he'd learned at the temple. Clarya had laughed and wished she was Force-sensitive, and Rion had lifted her in the air, saying that flying was far better than being a Jedi, anyways.

Last night, Clarya had wanted to go racing. Rion had a landspeeder he'd hardly had the opportunity to use since getting back from the temple, and Clarya desperately wanted to try it. She was their father's daughter entirely ━ with the wind in her hair, she could do anything, be anything.

And nobody had ever been able to say no to Clarya.

Memories of the accident are more fractured, flashes of blinding light and sickening noise. Dory and Mare had gone along with their siblings, not wanting them to get into any trouble. Rion had been driving... too fast, Dory had thought, but she'd never been a thrill-seeker like her little sister, so she hadn't been too concerned.

Until Rion lost control of the speeder.

Dory woke up on the ground. Mare was screaming, covered in blood that didn't belong to her, clutching Rion to her chest. He'd been unconscious, too, the jagged cut across his head leaking crimson into his hair. The air crackled around them, heat from the speeder rolling over them in waves from where it lay burning nearby.

Clarya had been lying next to Rion. Her eyes, wide and blue as the dusk sky above them, stared blankly at nothing at all. She'd been impossibly pale, her leg bent at a strange angle, her hair stained pink. Dory had dragged herself over there, an unbearable pain digging claws into her chest, and only after a moment had she realised that her sister was dead.

Mare holds tighter to her now. It is too warm beneath the blankets, and her lungs ache for fresh air, but salty tears flow silently down her cheeks and Dory cannot bear to face a world without her sister in it.

"Where's dad?" she asks, careful to hold her voice steady, so she doesn't upset Mare anymore than she has to. Last night, Dory had been a howling beast, pounding fists against her father's chest, a cataclysmic explosion barely-contained within a fragile teenage girl.

But Mare's brother, her closest and dearest friend, is still unconscious in the medical centre. The doctors fear he may never wake up. While the cruellest, most spiteful parts of Dory pray he never does ━ he took her sister with his recklessness, and Dory has always seen the world in -black-and-white, and eye for an eye, his life for her sister's ━ she knows it would destroy her aunts the same way it has destroyed her parents, left them a burnt-out wreck the same as the speeder that crashed.

It would destroy Mare like it has destroyed her.

Gently, Mare shrugs, sniffling. "He wasn't with Aunt Yve and mum. I think he left... Maybe to check on mama and Uncle Luke? I hope he comes back with news..."

Dory has to fight to bite her tongue.

Later, when the sun is higher in the sky and Dory is done being angry with it ━ how dare you rise on such a dark day? she wants to spit at it, bloody fingernails grasping for the sky in a bid to tear it down ━ she peels herself from her bed, showering away all the blood and smoke from the night before, though the pain remains.

She passes the guest room her aunts had made up for Clarya during their stay. The door is cracked open a little, and peeking inside, she sees the room is exactly the way Clarya left it. Clothes strewn across the floor, a pile of her favourite books on her bedside table, the ones she brought just for this trip, in case Aunt Ashka and Aunt Leia didn't have any she wanted to read.

Reaching out, she pulls the door closed sharply, as if she can trap her sister's ghost in there forever.

Her mother and Aunt Ashka aren't in the kitchen, but the living area. Yve looks as if hell descended on her in the night, and left her nothing but a living corpse; her blonde hair, patches of silver creeping in at the roots, is a tangled mess, her eyes bloodshot. Ashka looks little better, her own blonde hair kept in a long braid thrown over her shoulder. She smiles at Dory as she enters the room.

"Mare is sleeping in my room," says Dory quietly.

Her aunt nods, hands folded carefully before her, every inch a politician. "I don't think she slept a wink all night, worrying about her brother."

"I don't think any of us slept, really," Yve says. Dory's eyes dart to her mother, who pats her knee. Soundlessly, Dory pads across the room and curls up in her mother's lap, in a way she hasn't done since she was a little girl. Her mother wraps thin, strong arms around her, stroking her hair back and rocking her like she is a baby again, and Dory doesn't mind.

Quiet sobs wrack her body as the tears flow once more. Her sister is dead. Sweet Clarya, her little sunshine sister, born in the summertime. She used to weave flowers in her hair and dance on the balcony when she could, and their father would let her stand on his toes even when she grew too old for it, just so he could hear his little girl laugh.

Her sister wasn't an angel. Clarya could be a brat when she wanted to be, when she didn't get her way, but she was the brightest flame of them all, and in the end, she was only a flickering candle, snuffed out far too easily when she should have been a star, burning forever.

Her mother is crying, too. Her tears flow into Dory's hair, making it damp, but she doesn't mind at all. There is enough ache here to drown the whole room, if they truly wanted to. Dory wants to open her veins and let it all spill out, let her ocean of hurt drown the world. She wants to take everyone down with her into this agony. She wants everyone is the galaxy to feel as awful as this.

It was her fault.

She should've tried harder to stop them going. Clarya wanted to go, and Rion wanted to show off for his cousins and sister, but Dory had known it was a bad idea and she'd let them do it anyway. She was the oldest. She should've stopped them. She should've known better. She should've told Rion to slow down, to stop...

It's Rion's fault, too.

"Have we heard anything?" she wonders aloud, her raw throat burning.

There are a million other questions she'd rather ask. Like why did this happen, or how did this happen, or where has dad gone? All of them feel like ticking bombs, each designed to inflict maximum damage, so she sews them into the lining of her tongue and keeps quiet.

Asking about Rion is normal, and safe, even if she doesn't care at all.

Her mother's arms stiffen around her. Aunt Ashka frowns, the gentle lines of her face deepening slightly. When Dory looks properly, she sees her aunt's eyes are bloodshot, too, and there are dry tear tracks staining her cheeks. Her too-thin fingers weave together.

"We didn't want to wake you," she says quietly, her gaze falling to the ground. Her shoulders droop slightly. "Leia called and told us about an hour ago... Rion woke up in the night."

Dory swallows her bitterness like poison. It festers in her gut. She wanted him to die instead. If she could trade her life for her sister's, then she would, but she would trade Rion's first. Her cousin is lovely and good, and she hates him still for what he did. For what she let him do.

It's his fault, and your fault, too.

"Is he alright?"

Ashka picks at a loose bit of skin on her thumb. She seems so unlike herself that Dory has to blink, in case she is dreaming. Her politician aunt, a former princess, married to another politician and former princess, has always been the smiling kind. Even so, Dory has always been able to pick out the similarities between Ashka and Yve, aside from their shared blonde hair and shining blue eyes.

She sees the similarities in the harsh edge to their smiles, the mischievous glint in their eyes, the sadness that settled into their bones over thirty years ago which hasn't ever gone away. Ashka may be a politician, but she has always been easy-going in equal measure, determined to balance her stoic facade with something happier.

Today, Dory isn't seeing Aunt Ashka. She is seeing Ashka Cybele, the politician, sharp-angled and cool, channelling her emotions into being someone else, to control the situation.

"He's alive." Ashka offers a small, slightly-relieved smile, but Dory doesn't take the bait.

"And?" There's something else. Dory can tell.

Ashka hesitates for a moment, and then sighs. "He doesn't remember what happened. The accident. Or..." Her lower lip trembles. Something inside her breaks free, and a single tear rolls from her eyes and drips from her chin. She doesn't bother swatting it away.

"Or anything at all."

For Dory, her fragile world, held up with cracked pillars and broken columns, comes crashing down in that moment. Her damned cousin, Rion, who caused the accident and killed her sister, gets to blissfully forget about what he did. Her lovely cousin, Rion, whom she still loves because that's how awful the world is, gets to forget.

And she has to remember. If, in that moment, Dory had known what would come for them all ━ what the memory of Clarya would make them become, how they would fill the void she left, how they would take the ache and learn to make it feel like home ━ she would wish to forget, too.

#star wars fanfic#star wars oc#poe dameron oc#poe dameron x reader#rey star wars fanfic#* fic: beautiful ghosts.#* chapter update.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

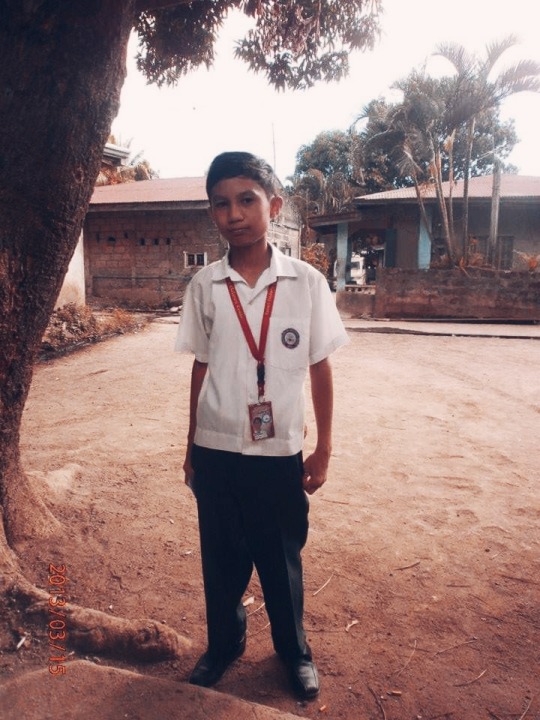

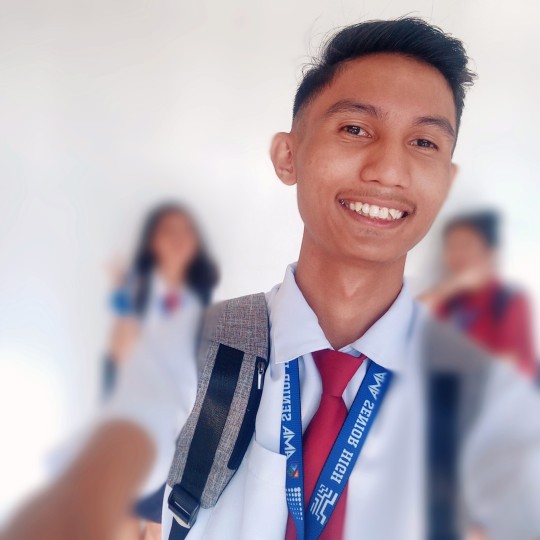

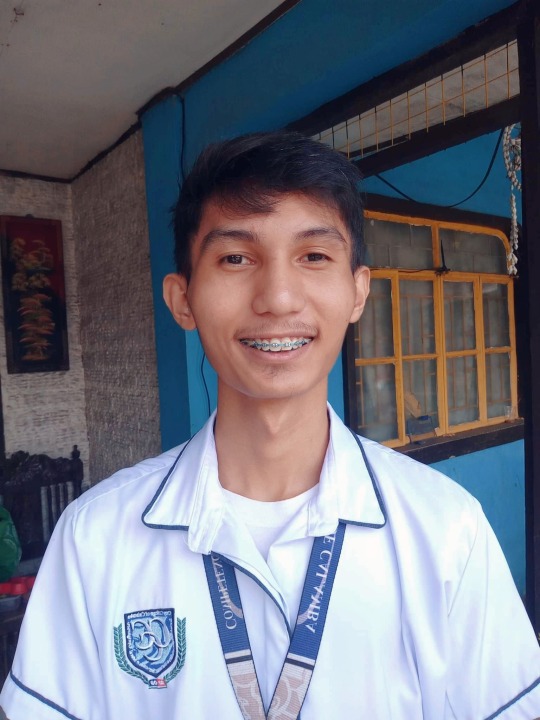

Hi! This is my first blog and I would like to share my adventurous journey about my life. Let’s start. My name is Ian Francis Maranan. I’ve been living for 20 years since the day I was born on the 25th of October, year 2000. I’m currently living in the city of Calamba, province of Laguna. When I was younger, I was an introvert. I don’t like interacting with anybody other than my family. Many people don’t know the truth about me, not even some of my friends.

I am the fifth and last son of my biological parents. Yes, I am an adopted child. It is because of an emotional turmoil that my family was going through that time. Truth is during the whole duration of me being inside my mother’s womb, every single family member didn’t know that she was conceiving me. They only discovered it when my godfather heard my cry as a baby. The pregnancy was not expected nor my birth because it was just recent when my brother was born. During that time, my biological mom is experiencing a psychological problem so she’s been emotionally unstable resulting to our family facing financially insecurity. For everybody, I am the miracle baby. Despite the challenge that my biological family, there is still hope.

I was adopted by the eldest sister of my biological mom who is my Mama Dorie. She is one of the many Overseas Filipino Workers in Macau. She is still single until now so I’m very sure that I am the only boy in her life. Though I was left here by Mama Dorie with my Lola, Mama Dorie and Mama Gloria’s mom, we never failed to communicate with each other. I am really blessed, right? I have three mothers, a father and four brothers.

For 11 years, my Lola took care of me and loved me. I was in grade 5 then, but I can still remember how dark my days when she died. I really miss her. I miss when she brings me to school and takes me home every single day. I miss her ways of disciplining me. I miss her every Sundays I go to mass because it reminds me of her wanting me to grow up as a child who is God fearing. But I’m still thankful I had her for 11 years of my life and I would treasure those times and memories with her.

After the death of my grandma, I was left in the custody of my Tita Delia until I graduated grade school. Tita Delia is a day care teacher and the mother of my best friend and cousin, Benok. I had been a consistent honor student then. With the help of my biological brother, who is a licensed teacher now, I excelled in my studies. He’d been very patient with me every day so I guess I had to give back through a bit of recognition in school.

I graduated in grade six as the second honorable mention or top four of our class. That time, my Tita Delia was supposed to be with me on graduation but I was surprised when Mama Dorie showed up on the day of my graduation ceremonies. I was still in shock Mama Dorie and I claimed my diploma and academic awards at the stage provided. But that doesn’t end there; Mama Dorie brought me to Macau and Hongkong as a graduation gift.

After that, I continued my journey at the city of Makati. Mama Dorie decided to send me to my godmother’s house to live and continue my studies because things were a bit complicated when Lola passed away and no one will take care of me. Not even my brother because he needed to focus in his work to support the needs and finances of my biological family. So, I started studying in Gen Pio Del Pilar National High school in Makati as a grade 7 junior high school student. At first, I was really nervous. Imagine; you have been some kind of an introvert for years than suddenly you are in a new place with no acquaintance. Scary, isn’t it?

In spite of my shyness, I tried my best to have some friends in school and luckily, I gained a lot of them and found that extrovert part of me. Every holiday, I visit Laguna to have some vacation. I finished junior high school in Makati city. I experienced facing challenges and sharing memories as a student and as a friend. Although junior high school wasn’t a paradise, I still had great memories. I’ve gained a group of true friends which was formed during grade nine and grown at grade ten. We named ourselves “team hoCage”. We thought it was funny when one of my friends pronounced hokage as hocage and so we laughed and decided to use the word as the name of the group. I will never forget those treasured bonding memories that I had with my friends. At the day of our moving up ceremony, I thought it will be the last day I’ll see them; we hugged and promised that we will bond again. Now, even from afar, we still talk together through online communication.

Moving on, I decided to continue my studies in Laguna at an IT school named AMA Computer College-Calamba campus. Taking science, technology, engineering, and mathematics strand. For the last 2 academic years, senior high school has been very challenging yet fun for me. I’ve made new friends. I had come to learn to be more independent. It has been a year of learning as well. And though it was tough, I am grateful, especially to God, my friends, and family who have always been there to help and support me. I am hoping there will be more wonderful, exciting and blessed experiences to come in my journey through life.

For now, I am currently a student in second year at City College of Calamba, taking an IT course. I am grateful for experiencing college life, still in progress until I graduated. This period of time is not that easy as an adult. I'm always thinking about my future and whether I will be successful. Many responsibilities will come, so I should be ready to face them. Today, this pandemic has had a major effect on our lives. Many of us are facing challenges that can be stressful and that can cause strong emotions in adults and children. One of the major effects is education. Many students are struggling with their modules and online classes, and some of them are worsening their mental health conditions. I hope this pandemic ends soon.

Now, I’m focusing on the things I like. First on the list is my love for arts. I draw a lot. I love creating portrait and anime drawings. I wish to be recognized someday as one of the popular artists in the world. I also like taking pictures with my smart phone usually through selfies or groufies with my friends and taking pictures of sunset and post it on my Instagram or Facebook accounts. A lot of people say that I have skills in photography. Someday, I also wish to have a dslr camera. Definitely, my life will not be complete without sports. Badminton is first on my sports list which I started playing since childhood. Second is playing volleyball. I also love playing strategic games like chess and dama. I also dance and I consider it as my passion. I like watching hip-hop and urban dance videos because it really makes me happy. As a result, I’m become a fan of Matt Steffanina and Sean Lew for the reason that they are the great dancers and choreographers and that they keep inspiring the people in the field of dance. I’m also a certified music lover and I can’t live without it. I play music that fits me when travelling, feeling alone, feeling sad and feeling bored. Music is my source of happiness. Just by plugging the earphones, you can easily forget the world.

After all, I feel blessed and I’m thankful for the good things that had come into my life and for all my friends and my family who never fails to put a smile on my face. In life, we commit mistakes but always put in mind the things we learned from it. There will always be a bad days and problems will come into your life but never give up and always stick of the positive side of life! There will be a way to solve it and let our God guide you always.

I want to thank you for reading and I hope I made you smile :) Have a nice day! :D

1 note

·

View note

Note

You like AUs, right? Mash up Metalocalypse and That 70s Show, go! Mash up Metalocalypse and Friends, go! Mash up Metalocalypse and Frasier, go!

Oh jeebus, why?

… But yeah you’re right I do.

That Dethklok’s Show

You know what makes me mad is that I want to say Nathan and Charles are Eric and Donna, but Seth is unarguably Lori and that messes everything up.

Okay so Pickles = Eric, Seth = Lori, Calvert = Red but with hair, and Molly = Kitty except Seth is her favorite child too.

Skwisgaar = Kelso because he’s tall, pretty, and horny. Also, in this AU, he is drowning in brothers because Servetta can’t keep it in her panties.

Toki = Fez because he’s foreign, happy most of the time, sings and dances for the simple joy of it, and his room is decked out with toys and fun stuff.

Murderface = Hyde because of the righteous fa-RO baby, and also because he DOESN’T HAVE ANY PARENTS. He moves in with Pickles’ family and lives in the basement. (Pickles was hoping this would give Molly and Calvert another Target to rag on and give him a break. It didn’t work.)

Unlike Hyde, Murderface is not cool and doesn’t get any eventual Hyde/Jackie storyline. Instead, his relationship history goes more like Fez’s. Without the weird forced Fez/Jackie stuff at the end of the series, which really went downhill has soon as Donna dyed her hair blonde.

Charles = Buddy, the random rich kid who is canonically gay, only he’s a regular part of the group instead of a one-episode throwaway character.

I’m cool with Pickles/Charles, and that fits with Buddy coming on to Eric in the show. But I would eventually break them up and put Charles with…

Nathan = no one on the show, but he’s got a lot of Hyde’s qualities in terms of stoic, bad boy vibes. However, like Kelso, he is an Adorable Dumb (see “that’s doable” hat).

Rebecca Nightrod = Jackie, but she’s not a necessarily a regular character. Murderface fawns/lusts over her like Fez, even though she’s a bitch. Nathan hates her, even though he does date her briefly in a relationship that she holds onto tenaciously until, in an act of desperation that absolutely horrifies Pickles, he cheats on her with Seth.

Abigail = Donna, because she’s smart and has good hair. (Zero bleach kits in sight.)

Rockso = Bob, because he’s a cue ball on top and makes liberal use of crazy wigs. Bargain Rockso’s is that store that’s always open on holidays — just in case you’re driving home Christmas night, realize you forgot to get a gift, and rush in to buy a fridge to solve the gift problem and/or some cocaine to forget there was ever a problem in the first place.

Magnus = Leo. He gives Murderface a job at his hilariously unprofitable Photo Hut business, declines to sell his real cool car to Skwisgaar on principal, and generally supplies the gang with all their weed and assorted drugs.

Dory McLean = Midge. She’s young, dumb, has big boobs, and Abigail is exasperated as hell that she doesn’t understand feminism in the slightest.

Knubbler = Mitch, the weird kid who hangs around and is sometimes kinda entertaining but keeps hitting on Abigail, which annoys her. However, he’s also stupid and accidentally self-sabotages (see setting his sleeve on fire while trying to flirt), so she doesn’t really waste energy on slapping him back down.

Pickles “burning down the shed” = Eric telling Red “I do it too” when Hyde gets busted for possession. Either way Abigail (Donna) is standing in the background going, “For the love of god, DON’T.”

Trindle = Cousin Penny, only instead of prankish Pickles (Eric) she targets Nathan, who during her last visit when they were much younger helped Pickles trap her in a revolving door. Abigail is completely secure in her looks compared to Trindle and actually talks Rebecca out of a potentially disastrous sunlamp tan.

Nathan and Abigail go out for like, a second, while Nathan and Charles are I one of their off-again fazes.

Endgame parings are Nathan/Charles, Abigail/Rebecca, and Skwisgaar/Toki.

B.A.N.D.M.A.T.E.S

Nathan = Ross. Can you picture Nathan doing the *long sigh, ex wife is a lesbian blues* “Hi” thing? Because I can.

Abigail = Carol. They got together but it just didn’t work out in the long run.

Rebecca Nightrod = Susan. Tbh, I think the reason she keeps popping up is because of how @little-murmaider portrayed her in Stay Alive. She and Nathan get along like a house on fire, in that it’s a disaster and Abigail keeps having to turn the hose on them to stop the bickering.

Toki = Monica, although his chef skills are mostly confined to providing fruit and burning plastic. He’s still got the overshadowed younger sibling thing going on though.

Molly = Judy Geller. Dotes on Nathan.

Oscar = Jack Geller. Is amiably odd.

Charles = Rachel. Except not as ditzy. But he does break an engagement off at the altar and moves in with Toki, an old acquaintance he hasn’t seen since high school and one of the few people he, ah, did not invite to the wedding. For the record, he was hoping that wouldn’t come up.

Skwisgaar = Joey. Except when they all go to London, Toki (Monica) does hook up with him, gradually teaches him how to relationship, and eventually they get married.

Murderface = Chandler. He hates his data processing job and keeps threatening to leave it to work on his side project, Planet Piss, but never actually does because the money is really good. When he goes back to the pet store to return the baby chick Skwisgaar impulse bought, he instead adopts an ugly-ass duck that no one wants because it’s original owners thought it was just an ugly duckling that would grow up into a swan. He feels that he can empathize with it, and names it Dick van Duck.

Knubbler = Dick van Duck. Listens patiently to all of Murderface’s Planet Piss ideas.

Pickles = Phoebe. He doesn’t even know who his dad is, and is proud that he doesn’t. (I’m not going to lie, Phoebe’s family situation definitely fits more with Murderface, but Phoebe’s dating track record is too good.) Remember the one where Pickles broke up with someone he’d just moved in with because the person shot a bottle of liquor?

Seth = Ursula. 100% Ursula. Seth is a “career driven” waiter and also a part time porn star on the side, using Pickles’ name.

Fraiser

I don’t watch this one as much, so this one won’t be as detailed probably.

Skwisgaar = Frasier. Idk, because he goes on dates with a different woman at least every episode. Also, he’s a jackass, but good at what he does and there are some redeeming glimmers of not being a complete asshole that make his presence worthwhile.

Nathan = Niles. Minus most of the neuroses. Instead of successful musicians, he and Skwisgaar are both successful psychiatrists, although Skwisgaar usually gets the bulk of the public’s, ahem, attention.

Daphne = Charles. He’s oblivious to Nathan’s crush on him for ages, but when he realizes it’s there and thinks about how sweet Nathan’s always been to him, he falls hard.

Rebecca Nightrod = Maris. She and Nathan have a rocky marriage, and eventually a rockier divorce in which she accuses Nathan of being emotionally unfaithful because of Charles.

Abigail = The brilliant divorce lawyer that handles Nathan’s case, and briefly dates Charles. They seem like such a good fit on paper that they’re actually engaged for a bit, but they break it off amiably right before getting to the altar, and Nathan and Charles ride off into the sunset in an RV with “road warrior” vanity plates.

Toki = Roz. (I know, technically Roz’s promiscuousness would be more Skwisgaar, but Skwisgaar’s superiority complex fits better with Frasier.) Although competent and successful in his own right, he is not the on air talent. Unlike in Frasier, when Toki and Skwisgaar sleep together they actually become a couple instead of backing off and remaining good friends.

Rockso = That garbage man that Roz was head over heals with for a while… Rodger?He belongs in a garbage can. Anyway, after breaking up with Toki over the latter’s inability to get over his massive cocaine use, Toki goes to Skwisgaar for comfort, which leads to drinking which leads to sex. Toki flees the next morning and flies to Norway for the annual family reunion, only he hadn’t told anyone he’s broken up with Rockso. Skwisgaar, desperate to Talk Things Out and hopefully even Do That Again, follows and (cringingly, but of his own volition) answers to/pretends to be Rockso to help Toki save face in front of his critical family.

Murderface = Bulldog. He and Toki briefly have a thing, and he’s actually kind of sweet when you get right down to it, but things don’t work out. Masturbation photos are involved — don’t ask. Also, at one point Skwisgaar accidentally repeats a rumor that Murderface is going to get fired where Murderface can hear it, so

Murderface goes and yells at the station manager (then Knubbler) and quits. Then he’s unemployed for a while, and scrapes by delivering pizzas. I forget how that situation resolved itself in the show but it does.

Knubbler = Kenny the station manager. Weak willed. Weak chinned. Ineffectual. Good track record in his career, but mostly he’s just there.

Abigail = That domineering and extremely competent lady station manager that’s there for a while… Kate? Has a cat. But she does NOT get it on with Skwisgaar (Frasier) on his desk and accidentally bump the On Air button partway through. She has a very strict policy of not getting involved with anyone she works with, although naturally everyone tries.

That’s all I got.

Magnus = Martin. Because he’s a cranky old man. He and Nathan don’t get along and he resents having to live with Skwisgaar, but they all gamely trade barbed insults and leave it at that. Magnus is a retired cop who still works on old cold cases as a hobby, having vowed revenge on uncaptured murderers everywhere. He and Charles (Daphne) get along pretty well, and there is no stabbing of any kind.

Metal Masked Assassin = Cam Winston. At one point he blocks Skwisgaar and Toki in Skwisgaar’s SUV into a parking space with his own SUV, and only relents and backs out when Charles comes and calmly threatens him, because “that’s my bread and butter you’re blocking in.”

There, are you happy now?? I spent a ridiculous amount of time on this, asdf;lkj lol.

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Six Sentence Sunday

Sharing excerpts from works in progress and completed stories under the cut.

Snow White & Rose Red, Chapter 1:

Once upon a time in a cottage in the woods lived two lovely girls and their mother. The older girl was named Rose Red because when she was born she had the prettiest little red lips and rosy cheeks. Just so people would be sure to remember her name her mother made her a red cloak to wear when she went to town for her. Rose Red grew to be a beautiful young lady with lovely auburn locks and shining sapphire blue eyes.

The younger girl was named Snow White for when she was born both her skin and hair was white as snow. Like her sister, her mother made her a white cloak.

WIP- Reworking this entire series before re-release.

Silver and Gold, Chapter 1:

On the first fine Spring day Bilbo, Balin, and Gandalf left Erebor; Bilbo to return to his home in the Shire, Balin to summon the Durinfolk to their ancient home, and Gandalf to go wherever it is wizards go. Dori was never certain where it was Gandalf got off to and wasn’t sure he cared as it reminded him too much of Nori’s old rambling ways. All he knew was that it seemed rather irresponsible to go off somewhere else when one was expected and/or needed elsewhere.

That was why he had waited so long.

Dori hugged his family and friends and perhaps blubbered a bit about their leaving and his own. He would miss them all.

WIP- I keep going back and re-writing things.

Jackdaw:

In and out. In and out.

Dori would never approve if he knew, but Nori needed this. Mahal, how he needed this! He loved the thrill of it. He was breathless from the anticipation of it and his heart raced in the act of it.

Available for early access for $1 patrons. There is a teaser, a bit longer than this, available on AO3.

A Gypsy’s Dance:

Except for the tinkling of the bells about her ankles, her feet added almost no sound to the percussion of her dance. She didn’t need it what with the clacking of her many bracelets, the soft zyee-zyee of the coined belt and trim of her bodice, and the jingle and tap of the tamborine with its long streamers that she employed during the day. At night she had the little finger cymbals and the clapping along by the men of the village who had only given the gypsies looks of disdain during the day. No, the night was another matter entirely. Something in the gypsy music called the men from their judgment and brought them to the gypsy camp where they would toss coins at the feet of the dancers when the tempo of the music changed to something that aroused an unfamiliar feeling in the dwarf.

It had taken Bofur all of two days or perhaps two nights to get the feel for the exotic rhythms of the gypsies enough for him to join in with his pipe.

Early access phase for $3 patrons.

An Unexpected Return, Chapter 2:

“That’ll put her off, don’t you think?” Gigi asked as they hurried through the marketplace.

“Only a bit.” Hamfast pulled them behind a large cart of hay and watched from behind. “And not for long. She won’t give up.”

“We’re gonna get it when she catches us then. I’ll be out on my ear and you’ll be out of a job.” Gigi sighed. She could not even imagine the trouble they were going to be in when the nearest relative of their Master found out they had lied.

Chapter 1 is available for everyone to read on AO3 along with a teaser of chapter 2. The entirety of chapter 2 is available on Patreon as early access for $1 patrons.

An Unexpected Return, Chapter 3:

Now Gigi had spent the entirety of her stay wondering about Bilbo Baggins. When she had her hands in the rich, moist dirt of his kitchen garden she couldn’t understand how a Hobbit who had worked the same ground could think of leaving. Of course he left it in the capable hands of her cousin, so it would be well cared for, but who would possibly leave a garden in Spring? Who could? It must have been a terribly important errand or he was a decidedly careless Hobbit. Certainly she heard rumors he was a little odd, but as she felt the warm sun on her back, the cool, pliant earth between her fingers, witnessed the full greening and vibrant colors, and scented the fragrant breezes that whispered of flowers along the lane and pies cooling in windows, no one could be so foolish or odd as to leave a place that told every sense one was home.

Early access of this chapter is available for $3 patrons.

AO3 - https://archiveofourown.org/users/FountainsOfSilver

Patreon - https://www.patreon.com/FountainsOfSilver

Patronage and engagement unlocks more writing available for all to read for free on AO3 each month. Patrons get early access to complete chapters, one-shots, and sfw art as well as exclusive access to epilogues and nsfw art. <3

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

57 Facts Tag!

Thank you so much @serensims for tagging me! I kept seeing this in my dash, so I was genuinely surprised to be tagged myself. I’m tagging @dreemiie, @existentialisims, @xsunnysims, @justkeeponsimming and @thesheslittleredridinghoodblog (if you’ve already done this then sorry)

I love the color blue

I am a white, 17 year old Albanian girl

I’m a Taurus! I share this with my little sister and Mom

I have 2 younger siblings

My birthstone is emerald!

I share a birthday with my grandma

I have never left the U.S

I have never been on a plane (man I‘m boring)

I went to Hershey Park once and screamed my head off on some of the rollercoasters

I love seafood, like shrimp or crab (much to the disgust of my sister)

In order to youngest to oldest, me and my siblings are 4 years apart

I have never been stung my a bee

I am a huge baby when it comes to heights

I do not know how to swim

The only pet I’ve ever had was an angel fish named Dory when I was 5, which lived for 3 days because I was 5 and had no idea of to care for a fish (I’m sorry Dory)

Movies I was obsessed as a kid was Finding Nemo (pet fish was called Dory) and Tarzan

For I was obsessed with as a kid, Drake and Josh, SpongeBob, Goosebumps tv, and a whole bunch that was on CartoonNetwork

I have never broken a bone

I really want either a cat or a dog (I’ll probably just get a cat) when I have my own place, and financially stable enough for one

I still don’t know how to drive

I love coffee, and make is really sweet and milky (its basically not coffee at this point)

My favorite fruit is strawberries

I got into the sims from youtube

I use a MacBook air

I edit my screenshots with Gimp

I once burned my fingers trying to make tea back when I was obsessed with drinking it (coffee has taken over)

I really like doodling and drawing and want to improve at it

What got me to discover tumblr was Undertale, when I was looking at all the really cool fanart

I have been to so many wedding because I have so many cousins (including all’ve my distant cousins)

I have a lot of cousins

I can never get enough sleep when its a school night

When I was little, I loved reading the Goosebumps books, its what started my love for reading. My little brother has inherited that same love.

Once in 4th grade, before my family moved, I made the mistake I borrowing book 4 of Harry Potter from my school’s library (i was really getting into the series then) and I wanted to finish it, so I ended up spending a week just reading all day

I can’t handle spicy food at all

I really like the Broadway play Hamilton

I’ve taken 2 AP history classes (AP Euro made me suffer so much)

I don’t like bananas

I suck at learning languages

My first phone was an iPhone 4

I’m a city gal

I have face planted into the pavement

I have never been to Disney Land

I’ve never owned a game console of some kind ever (i really want to change that)

I have a bit of a weird way of speaking? Like its hard to describe. Not as bad as when I was little and had to go to speech therapy.

Someone once asked me if I was British

I suck at lying

I’ve read the Harry Potter series so many times

I used to be super into Rainbow loom and would make charms a few years back, and I still have a box full of leftover rainbow loom from that time

My closet has stacks and stacks of books from me and my siblings. It get’s messy sometimes

I always wear jeans, and either a hoodie or t-shirt

I almost always wear sneakers

I hate high heels with a passion

I’m not really into make-up that much

When I was little I wasn’t really scared of bugs but for some reason now I kinda am

I love reading

I once offered a dandelion to a random cat when I was 8 and the cat just curiously stared back at me.

I am bad at talking about myself

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Choice

The last installment of the Mori(you)/Thorin drabble series!

Art by unknown artist(egads, I hate when reverse image search gives me nothing but uncredited pinterest boards... I shall keep looking, because this is epic)

Previous chapters: Cuddles, On the Road Again, In Rivendell, Splashes of Thought, Frustrations Peak, Reactions, Mirkwood Muddle, Laketown and Lamentations, The Arkenstone, The Maker

“No…” Thorin moaned, when he saw her, pale and still, her auburn hair flowing across Dori’s thick arm. The cut eyebrow had clotted, but her hair was matted along the side of her face; a bloody wound on her temple still seeping red. “Mori!” he cried, fighting to get up off the cot where Óin was trying to fix his foot. “Mori, please,” he begged, but she did not stir, Dori’s silent sobs disturbing a lock of hair, making it trail across her closed eye.

“She’s not dead, Thorin,” Nori choked out, “but we can’t wake her.”

“Get the Elf,” he ordered, staring at the thief, “please. Tell him… anything. For her life, anything.” It was the last words he spoke, staring at her gentle breathing as though he could make the small motion of her chest continue by his willpower alone. Dori undressed her, letting Óin look her over for damages, but other than the head-wound there was little but a few bruises to care for. The Arkenstone shone on her breast, but Thorin ignored it aside from telling Dori not to move it. He had not been the one to give it to her, but Mori should be Queen – would be Queen, he swore – and the Arkenstone should be hers. He saw again the way she had smiled when she’d spoken of the song – he had touched it before, before the dragon, and it had not sung for him, which made him wonder if the Mountain thought him unworthy of the seat of his forebears; yet he dared not reach to touch it, dared not test whether the song would fill his soul as he had seen it in Mori. It hardly mattered; Thorin considered himself unworthy of the Throne, and even if his apology was accepted by the small Hobbit, he did not think it would be enough to erase the shame of his actions over the past month. Dwalin had punched his good shoulder – Thorin had felt he’d earned a punch to the bad one, but Dwalin wasn’t cruel – and he knew they would eventually be alright; he had not wanted to harm Dwalin in the Throne Room, though he seemed unable to stop himself from reaching for his sword – his words meant as a warning as much as they might be perceived as a threat.

“You asked for me, King Thorin?” Thorin had never been so happy to see anyone as he was to look upon the Elvenking in that moment, had never heard a voice as sweet as the haughty drawl that filled him with a burning sense of hope.

“For Mori,” he whispered, staring at the Elf; uncaring that his heart was laid bare before those ancient eyes. “Please. Help her.” Thranduil gazed at him for what felt like eternity, but was probably no longer than a minute, turning his face towards Mori instead. He hummed, stretching out long pale fingers, resting his hand on her forehead and closing his eyes.

“Móeidr Queen,” he murmured, “where have you gone?” Later, Thorin would have sworn Mori began glowing, just like the elf; lit from within by starlight, the green walls around them brightening. The elf was singing; Thorin did not understand the words, though he felt an indefinable sense of power in the chant. Thranduil’s eyes opened, staring directly at Thorin. He did not speak, and Thorin felt absolute certainty that he didn’t even see the Dwarrow in the tent, paying no heed to Thorin’s own pleading gaze, nor to the way Ori was whimpering in Dori’s arms, while Nori was cursing at the healer trying to tend him.

“Uncle!” Fíli cried out, waking in his own cot.

“Hush, Fíli,” Thorin croaked, reaching for the lad to press him back down. “You’ll tear out Óin’s stitches.”

“Kíli?” his oldest nephew begged, staring up at him as he fought the draw of the poppymilk Óin had given him. Thorin sighed.

“He’s fine; we were only worried about you.” There had been so much blood; so much blood Thorin had felt certain that death had come for his golden prince… but it had not. “Kíli’s got a broken arm,” he murmured, squeezing Fíli’s hand. His nephew tried to return the touch, but his fingers lacked their customary strength, Thorin knew. Fíli would be weak for a time, but the blade that had pierced his side had missed all major organs, simply slicing through skin and muscle. “He’s in the food tent, I think.” Fíli nodded, subsiding into drugged sleep once more and Thorin’s attention fixed inexorably on Mori’s rising and falling chest; was her breathing slower?

“Cousin,” Dáin’s usually boisterous voice was comparatively quiet as he shouldered his way into the small sickroom that the Company had claimed for their own. Thorin didn’t even have to will to glare at him, the anger he felt smouldering in his breast not willing to catch flame. If she died… “I’m sorry,” Dáin continued solemnly. “Does… is there… hope?” he asked, looking torn. Thorin wondered what his face was telling his deceptively perceptive cousin in that moment, but he had no mind to formulate an answer, lost in staring at Mori. The wound on her temple had finally stopped bleeding, though the bandage showed a stain in the middle.

“We don’t know yet, cousin,” Dwalin murmured, startling Thorin who hadn’t even realised that the warrior had resumed his usual silent position at Thorin’s side.

“She has to…” he trailed off, unable to voice even the possibility that she might not. Even if the kiss had been a fluke and she was still angry with him, so long as she was alive to be angry with him, Thorin would take it; as long as Mori simply existed, his life would not be so… empty.

Thranduil’s eyes closed, and he seemed to sway gently. The light diminished, leaving them bathed only in the gentle glow of the Arkenstone. He moved slowly, pulling his hand back from Mori’s face with what Thorin might have called a caress and a soft smile, if he had had the presence of mind to care. He stared. The Elvenking’s eyes opened again, but this time the sharp gaze was present, the mind behind the blue eyes alert.

“So be it…” he breathed, stumbling back from the cot. Dori’s quick action kept him from falling, the tailor guiding the Elvenking to a chair in the corner. He fetched him a cup of water, helping him sip. Thranduil’s hands trembled.

“Will…” he tried, but the question would not pass the guard of his teeth. The elf held up a hand, making everyone in the tent fall silent.

“I think so,” he finally muttered, wiping a loose strand of hair away from his blood-spattered face. “It was… the oddest sensation I have ever felt.” The Dwarrow simply stared. Ori was still clinging to Nori, whose face seemed grey as he stared at his sister.

“What did you do?” Thorin heard himself ask, without choosing the words.

“I don’t… know. There was light, and singing,” Thranduil mumbled, his gaze distant as though he was staring at something only he could see. “Lady Mori was there, and a presence I could only call… Aulë, I think, though I cannot say how that could be. I- I made her remember.” He swallowed. Thorin copied the nervous move.

“Remember… what?” Some people with head injuries were never the same; just look at Bifur, Thorin thought. Would Mori be one of those?

“You,” Thranduil sighed, getting to his feet. “The rest is up to her, King Thorin; the choice is up to her.”

“What choice?!” Thorin called after him, as the elf ducked out of the doorway – he didn’t really need to, it was high enough for an elf to enter the sickroom comfortably – but Thranduil did not turn around.

“Life,” he said, his voice floating back to the group of Dwarrow who were now staring horrified at each other, “or death.” The wounded noise he heard; not quite a scream, but not a whimper either, didn’t end until Thorin realised it was coming from his own chest, turning back to Mori as though she might have perished in the seconds since he last looked at her. Dori was cleaning her hair, the dark rust colour of dried blood turning the water in his bowl red, as he combed out the auburn strands. Nori had taken her hand, staring just as intently on her chest as Thorin himself.

“Don’t!” Thorin cried, when Dori made to move the Arkenstone from her breast; she had apparently stuffed it into her breast-band, and a distant part of him knew it couldn’t be comfortable for her, but a larger part of him felt utter revulsion at the thought of taking the stone from her; in his mind, the Arkenstone belonged to Mori, his Queen… whether she lived or died. “Leave it, Dori,” he muttered, when his loud voice shocked them all. “The Arkenstone. Leave it with her; she owns it.” The Heart of the Mountain, he thought wryly. It was a fitting tribute for the one who held the Heart of the Mountain’s King. Dori nodded, but didn’t reply, though neither ri-brother objected when Thorin hobbled over to sit in the chair on Mori’s other side, stroking her palm gently.

They waited. Thorin would have liked to say – and it would have sounded better in a song – that they waited still as statues, all eyes on Mori, but it would have been a lie. As more wounded soldiers made it through the Gates and into the purview of Óin and a handful of healers from the Iron Hills, the sounds of busy hands interrupted the silence. Someone brought them food, and at some point Dáin disappeared along with Balin, but Thorin didn’t care. He looked up when Kíli returned, but he only managed a pale smile in the direction of his nephew, who was quietly filled in by Ori before he collapsed on Fíli’s cot, making Thorin think of the way they would sleep closely entwined as dwarflings when Fíli just protested sleepily and wrapped his arm around his younger brother.

Mori squeezed his hand.

Thorin looked up, gasping, to meet the equally startled gaze of Nori, who had been holding her other hand. Turning his face slowly, he feared what he would see. Mori squeezed his hand again.

“Mori,” Nori croaked, while Thorin could only stare at her, speechless. Mori smiled gently, tugging on Nori’s hand.

“Hey, nadad,” she whispered hoarsely, “fancy meeting you here.” Nori gave a watery chuckle, leaning in to press his forehead against hers. Dori was openly weeping behind him, Ori’s head pressed into his shoulder and Thorin felt like he might be able to breathe again. Nori’s shoulders shook, and Mori’s fingers remained wrapped around his thumb, a remind to Thorin’s wildly beating heart that she was there, she was alive.

“Mori,” he finally whispered, when the thief sat up, wiping his face with his grimy sleeve. Thorin didn’t dare to hug her, though he wanted nothing more, wanted to hold her as tightly as he could, kiss her like he had dared to do in the middle of battle.

“Thorin,” she replied, biting her lip. All his attention zeroed in on that spot, the contrast between her white teeth and the red lip, turning slightly bloodless with the pressure.

“Mori…” he repeated, hardly recognising his own voice. He felt her tug on his hand.

“Come here, Thorin,” she murmured, and he could do that, certainly, he was capable of following that simple command… right?

Thorin remained upright, stiff as a statue. Mori’s brows furrowed.

“Thorin?” This time, his name was a question he didn’t know how to answer, reaching out the smooth the lines between her brows with a gentle touch. “What are you doing?” she smiled, tugging on his other hand again. His grip tightened, his free hand sliding down to cup her cheek as he leaned in until her grey eyes filled his view completely.

“Never scare me like this,” he murmured, stroking her cheek and tracing the line of her jaw, marvelling at the softness of her beard. “Never again, Móeidr,” he repeated, “promise me.” He stared at her, watched as her eyes turned almost silver, crinkling around the corners.

“Thorin?” she asked, her breath whispering across his lips. He nodded. “Kiss me.” He heard some far-off groan, but it was lost to his mind when he finally moved the last distance between them, slanting his mouth across hers. She had been sweet the last time, sweet and a little hesitant, but this kiss was filled with fire and love and Thorin couldn’t get enough, sliding his hand into her hair and seeking out every part of her mouth with his tongue, his own hair falling like a curtain between them and the rest of the room. Mori chuckled against his lips, squeezing his hand gently. Thorin pulled back slightly

“My Mori,” he murmured, kissing her again just because he could. “My Queen.” Mori’s eyes widened.

“I am not!” she objected, releasing his hand to lift the Arkenstone from her breast. “Take it, Thorin,” she murmured, pressing it into his hand. Thorin chuckled. “It’s your throne,” she insisted, “I was only holding it for a little while, I swear.” He didn’t like the anxiety in her face, the way he could feel her heart race beneath the heel of his hand where it rested against her neck.

“I will take it from you,” he murmured, pleased that she responded to his kisses still, “but you would still be my Queen, love, even if I do not deserve you.” Mori froze beneath him.

“Thorin…” she repeated, “Are you… what are you doing?”

“I was kissing you,” Thorin replied, feeling nearly giddy with relief. “And I think I just implied that you should marry me. Make it official, as it were.” He kissed her again, stroking her cheek.

“O-Official?” she stammered, and Thorin felt the heat of her blush against his fingertips.

“Yes.” He nodded; it sounded like a plan. “As Dwalin will tell you – because he’s evil like that – I’ve wanted you to be my Queen since… well,” Thorin frowned, considering.

“I’d say nigh a century, give or take,” Dwalin replied matter-of-factly somewhere behind him. Thorin started; he’d quite forgotten that there were others present. He felt the heat rise in his own cheeks, but he didn’t raise his head to glare at his old friend, simply stared at Mori.

“You… want to marry me?” she asked, lifting her hand to trace his face. Thorin turned his head, pressing a kiss into her palm. He nodded. Mori’s eyebrow lifted. Thorin began to feel like this wasn’t going to plan – not that he had had a plan, really, a small voice in the back of his head added. “And this is your idea of a marriage proposal?!” she asked, gaping up at him. Thorin closed his eyes; things were definitely not going the way he had dreamed when he allowed himself to dream of such things. “Look at me!” she snapped.

“Móeidr, daughter of Dagni,” he interrupted whatever she wanted to say, speaking quickly as he tried to salvage whatever fondness she still felt for him. “I have kept my silence, and if you do not accept, I shall speak of this never again, but I love you, as I have loved you, and as I will continue to love you. There is little to say that you don’t already know, and little to give that is not already freely given. I come to you as any Dwarf comes to his love. I swear to keep you and hold you, comfort and tend you, protect you and shelter you, for all the days of my life. Will you marry me?” He stared into her eyes, hardly daring to blink. Mori looked stunned.

“Oh, Mahal’s Beard,” Dwalin groused, “just accept already, we all know you’re mad for each other.” Thorin lifted his face to glare at his unrepentant Captain, but his ire was diverted by the way Mori’s fingers tangled in his hair, drawing him back to her mouth for a kiss that stole his breath away.

“Yes.” She whispered, when he finally had to pull back, feeling dizzy. “Yes, I will marry you, my clot-heid King,” she chuckled, kissing him again, “but don’t you ever dare try to banish me for my own good again!” Thorin nodded fervently, pulling her off the cot and into his arms. Mori went willingly, her solid form warm against his chest. A loud throat clearing interrupted him before his hand could move lower than the small of her back, making Thorin start guiltily, lifting his head to stare at Dori’s stern glare of disapproval.

“Hardly the place or time, Mori!” he exclaimed, gesturing wildly. Beside him, Nori was grinning; his greatest source of amusement was putting bees in Dori’s bonnets and Thorin had just managed spectacularly. Mori moved slightly, before she froze. The beads in her hair clacked together when she turned her face to star at him. Thorin ducked his head shyly, silently gesturing at her shift-clad body. Mori’s cheeks glowed slightly, but she settled more firmly in his lap, looking up him in a way that begged him to kiss the smirk off her lips. Thorin obliged dutifully.

“I think there’s no better time to kiss my future husband, Dori,” Mori stated calmly. Dori spluttered. If possible, Nori’s grin widened, though Thorin didn’t miss the speaking glance he sent towards the dagger that had suddenly appeared in his fist. His free hand signed only ‘or else’, but Thorin understood clearly. He nodded.

“Do you feel well enough, amrâlimê?” he murmured into her hair. Mori yawned.

“Hungry,” she admitted.

“Dori!” Thorin called, interrupting the rant no one was paying attention to. Dori shut up. Little Ori stared wide-eyed at Thorin. “Your sister – and Queen – is hungry. Could you get her some food?” Dori’s mouth opened and closed a few times but then he simply nodded, ducking out of the small room. Dwalin sighed.

“About time, Thorin,” he murmured, punching Thorin’s good shoulder lightly, “about bloody time.”

“Can you hear it singing?” Mori whispered suddenly, holding up the Arkenstone, its gentle glow bathing her hand and turning her skin milky pale. Thorin shook his head, still not quite daring to touch the shining gem. Mori kissed him, distracting him with her mouth as she placed the stone in his palm, holding it with him.

Thorin heard it.

Welcome home, my Children.

54 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Coco (2017)

In 2013, the Walt Disney Company moved to trademark “Día de Los Muertos” in anticipation of Pixar’s planned Day of the Dead film. Responding to the news, comic strip author Lalo Alcaraz (La Cucaracha) created a protest image of “Muerto Mouse”, warning of its intentions to, “trademark [Latino] cultura!”. Alcaraz, through La Cucaracha, has always been politically-minded through his comic strip and has been a vehement Disney critic since at least 1994, when he infamously dressed Mickey Mouse as “Migra Mouse” to protest the Walt Disney Company’s support of California Proposition 187 and the immigration policies of then-Governor Pete Wilson. So it came as a surprise to Alcaraz’s readers when he accepted a job as cultural consultant on Coco, directed by Lee Unkrich and Adrian Molina (also a co-writer). Alcaraz helped oversee an American film that justly honors Mexican culture while approaching questions about death in ways that cross borders, answered in different ways by people of different ages.

Looking at the reaction in Mexico, Pixar and Disney have avoided what could have been a mortifying cultural blunder. Unadjusted for inflation, Coco is a Mexican cultural phenomenon, being the highest-grossing film in that nation (adjusted for inflation, it is behind a handful of 2000s releases). With the exception of Russell from Up (2009), it is the first Pixar film in which the human protagonists are non-white. It is the first Pixar film to make note of and celebrate that specific cultural and national background. At worst, Coco is devalued by hackneyed storytelling decisions (this is a great Pixar movie, but not the best of what the studio has to offer) and its frantic climax. At its best, this an affecting tearjerker always in command of its characters’ sorrow and strength in family.

Born to a family of shoemakers, all twelve-year old Miguel wants to do is be a musician like his movie hero, Ernesto de la Cruz (a composite of Mexican singer-actors Pedro Infante and Jorge Negrete; both dominated the Golden Age of Mexican Cinema and make a joint cameo in Coco... Miguel also believes, for reasons best seen than described, that de la Cruz is his great-great grandfather). Miguel lives with his extended family, including his parents, cousins, grandmother Elena, and great-grandmother Coco (for whom this film is named). Día de Los Muertos – the day when the dead return to the Earth – is approaching. To describe how Miguel enters the Land of the Dead is too convoluted, lest this paragraph should run far too long. Upon entry with a stray Xolo dog named Dante, he is instantly recognized by his deceased relatives – everyone appears as skeletons – and is informed that he must return to the world of the living before sunrise with the family’s blessing. The family stipulates in their blessing that he must abandon any musical pursuits. Miguel refuses, and seeks to find Ernesto de la Cruz and receive his blessing.

Along the way to find de la Cruz, Miguel will pair up with Héctor, a fellow unable to return to the land of the living and on the cusp of being forgotten by his daughter.

Día de Los Muertos (also known without the “Los”; “The Day of the Dead”) is a Mexican holiday with Aztec origins that has been synthesized with Catholic elements. The holiday, known superficially among non-Mexican-Americans in the United States, might not be as familiar to audiences outside the Americas. But Molina and co-screenwriter Matthew Aldrich do their damndest to introduce the holiday, Mexican culture, even more than several snippets of Spanish throughout. This has been covered before in Jorge Gutiérrez’s The Book of Life (2014), another musical animated film delving into the Day of the Dead. Then again, there is boatloads of Christmas media that has been produced by American television and movie studios, so there should be room for more than one Day of the Dead movie. The animators certainly have taken great care of their worldbuilding and although the colorful Coco does not highlight the incredible visual bounds Pixar has innovated with each film (The Good Dinosaur’s photorealism, water animation breakthroughs in Finding Dory), the layered wide shots in the Land of the Dead recall what the multiplane camera provided for Walt Disney Animation Studios in the 1930s.

Preventing Coco from being top-tier Pixar is its tendency towards exposition dumps, a plot structure dependent on fakeouts that is becoming predictable and tired (something that keeps reappearing from Frozen to Big Hero 6 to Zootopia and unfortunately, I cannot elaborate any spoilers), and lightly treading on heavier moments (think of nursery rhymes that, after the first two stanzas, reveal stories dark and twisted, never recited by most parents). Molina and Aldrich spend too much of their screenplay having the dead characters explain their world, rather than it revealing itself to the audience. Once the basic rules are established for the Land of the Dead, they neglect Miguel and his living family. The living family also disdain Miguel’s wishes to become a musician, so how does he reconcile his love for family with their attacks on his true passion? The movie never makes that clear, missing a compelling facet of characterization. It is too focused on its an increasingly repetitive journey-to-x adventure (see: Inside Out, which I loved despite that criticism) that reveal more about the supporting characters than it does the leads. Not that exploring supporting characters is a terrible thing, but the aforementioned explains one reason why I haven’t truly connected with a Pixar lead character in a non-sequel since Up.

As I have mentioned before, personal and collective loss have been central to Pixar’s greatest movies since the beginning. Titles like Finding Nemo (2003) and the entire Toy Story series have been premised in loss – some losses being more abstract than others, like the emptiness of humanity found among the passengers of the Axiom in WALL-E (2008). Coco takes these themes further than all of these previous films, acknowledging that death is its central theme and not an accessory to characterization. All other subjects, feelings, and ideas can queue behind it as Coco inspires tears. Here, death takes on a culturally specific context approaching areas that major American animation studios have rarely endeavored: that death can inspire both anguish for whom one has lost and celebration for how they lived their lives. It is how one conducts themselves in life that informs how we die – even if one’s death is unexpected, senseless, arbitrary, excruciating.

Coco wants to reaffirm that, through the characters of Héctor and Ernest de la Cruz, that a person’s goodness will impact how they live in others’ memories, but takes a circuitous way to that point. The film neglects others who do not have a distant family member who can embark on an adventure through the Land of the Dead for them – in depicting the celebratory half of death, Coco forgets how death can devastate. The two can be balanced (see: Up), so it is an unnecessary compromise.

The closest Coco comes to darkness is the fact that, when a resident of the Land of the Dead no longer has anyone on Earth who remembers them, they disappear. This idea is first introduced when we meet Chicharrón, a musician friend of Héctor’s, whose time is dwindling. Chicharrón’s second and, perhaps, final passing occurs in silence and stillness, not entirely at peace. I wished that, while leaving Chicharrón’s shack with guitar in hand and after explaining the metaphysics of the Land of the Dead, Héctor took the time to tell Miguel things like why he and Chicharrón were friends, what he found admirable about him, a single memorable moment, and what he would miss about him. This need not have been a ten-minute retelling of Chicharrón’s life story, but it would have helped to show younger audiences that, yes, some are forgotten after death, but also the complexity of memory’s weight: how those we love most continue to live, in a way, when they have passed on. Though death devastates, it is not to be feared.

Coco is also a musical journey featuring a good score from Michael Giacchino (his fourth and final film score of the year, and his second-best behind War for the Planet of the Apes), but especially the songs penned by Robert Lopez and Kristen Anderson-Lopez (Frozen and the upcoming Frozen 2). Orchestrator Germaine Franco (an orchestrator decides upon the instrumentation of the score; Kung Fu Panda series, The Book of Life), was brought in to assure the music’s authenticity. Michoacano and Oaxacan (two states in Mexico) music is featured, as is a variety of genres: mariachi, banda, chilena, and norteño. Solo guitar, violin, pan flute, and trumpet respective to all those genres lead the orchestral-based score. A more qualified person should judge the appropriateness of Giacchino’s score, but, to me, it does not sound like a poor imitation of Mexican music that I might have expected from him about ten years ago. Giacchino continues to progress as a composer, knowing how to adjust his styles for the films he is working on.

Yet it is the song score from the Lopezes that take center stage in Coco, and no song is as important as “Remember Me”/”Recuérdame” (all provided links are the Spanish-language versions, as they are superior to the English-language versions – note that this review has been written on the basis of the English-language version). The song’s first appearance, sung by Ernesto de la Cruz in a flashback, is an energetic ballad replete with an awesome grito (a Mexican interjection analogous to an American cowboy’s “yeehaw”). But the song’s integration in its next two placements that will break the eye’s floodgates. Without saying too much, the lullaby and its final use in the film proper are marvelous examples of how a song may evolve in meaning from the beginning to the end. It changes with context; it changes as Miguel finds his way home. Pedro Infante and Jorge Negrete would be proud.

Marcela Davison Aviles (President/CEO of the Mexican Heritage Corporation) and playwright Octavio Solis joined Lalo Alcaraz as Pixar’s cultural consultants on Coco. Noting and implementing the suggestions from these three proved difficult for Unkrich, Molina, and the producers at Pixar, but it has been well worth it in the end. Aviles critiqued the film’s music, Solis examined the theatrical presentation of the film, and Alcaraz, “looked to include more Mexican elements in the film when possible, like additional Spanish in the dialogue, and made suggestions on specific words.” Says Alcaraz: “I think we struck a good balance on giving comments that helped the cultural authenticity of the story without bogging it down as if it were some kind of Día de Los Muertos documentary.”

Quality representation in American cinema has always been difficult (this is a classic film blog, so I should know something about that), and some movie executives say “catering” to minority communities is not worth the risk. When done correctly and with respect, the results are incredible to behold. Such fortune has followed Coco from the moment it premiered in Mexico, endearing itself to Mexicans and non-Mexicans alike. It is on its way to becoming the highest-grossing Pixar film in China (where Pixar has historically struggled). The Chinese censors have, in the past, enforced a rigid ban on the depiction of ghosts and other undead. But I sense in Coco’s case, because the veneration of the deceased is so prominent in China (as is the case in many East and Southeast Asian nations; being Vietnamese-American, my extended family’s practice of ancestor veneration is the most prominent aspect immune to Americanization), the censors did not mind this time. If your movie can even make a censor feel feelings to the point where they are not executing the letter of the law, you must be doing something right!

Perhaps my criticisms of Coco are actually quibbles, but I guess I will only know upon any rewatches. In any case, Coco is one of the strongest films – animated or otherwise – released this calendar year. It attempts storytelling that other contemporary animation studios and filmmakers are too hesitant to try. It builds understanding in a year where the nation this film came from has turned inward, benefitting none. That alone makes this newest Pixar film worth seeing.

My rating: 8/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found here.

#Coco#Pixar#Lee Unkrich#Adrian Molina#Lalo Alcaraz#Matthew Aldrich#Jason Katz#Michael Giacchino#Robert Lopez#Kristen Anderson Lopez#Germaine Franco#Marcela Davison Aviles#Octavio Solis#My Movie Odyssey

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rules: Answer 8 questions and come up with your own 8 questions. Tag others to answer your questions.

Tagged by: @neonfree

Something you get told by people all the time?

Well, I guess there are two things. That I don’t look my age (at the very least 8y younger than my actual age) and I smile all the time. First one I am starting to appreciate more and more, second one is actually tiring because people tend to have the attitude that nothing is wrong because I smile a lot. But lucky me I have a few great friends who knows me more than I usually want people to. Actually friends who probably knows me more than my own family.

The best dream you ever had?

While awake or asleep? xD

Thing is I rarely remember my dreams, when I do they are either scary or plain weird. But I guess the few times our earlier dogs Ritzi and Joy have appeared counts. Although it’s sad to wake up afterwards.

The clumsiest thing you have ever done?

I’m not really that clumsy. Sure I tip over a bit when going to toilet at night and stuff, but I rarely break things or fall over. But I do have bad memory and forget things easily. Things I just heard xD I’m like Dory in Finding Nemo.

What are the things you collect?

STONES! Ever since I was a kid I have loved stones. The tiger eye my dad brought back from South Africa was my favorite and my mom always had to empty my pockets of white, smooth and/or glittering stones whenever we went home after being out fishing. Even today I collect them. Brought at least a kilogram back from Albania, buying pretty stones at a local store and yeah... stones <3

I also collect VIXX albums, but not for that long of a time xD

A pet peeve?

Wow. ehm... people being rude without reason? I’m a leo, I thrive on happiness, including the happiness of people around me. Have a bad day? I listen. You sad? I listen. You just want some love? I’m there. But energy thieves who has no real reason to be rude or disrespectful but still are... no I won’t let things like that ruin my day. Also “I’m not racist/sexist/homophobe/etc, but-”... yeah, that is a pet peeve to many of us.

What are some of habits you have?

Bad or good ones? Both maybe?

A bad habit I have is I can stop listening to a conversation but still seem like I am listening (sometimes not). My attention span is short and I am trying to get better at it but have been like this since I was a kid. I listen better if I am doing something practical at the same time, like drawing or folding clothes, something that don’t require much thinking.

Good habit... trying to make people smile? Like I like to smile to make others smile (my job as a barista requires this too). And also say things to bring their moods up. idk, I just can’t feel at ease when people show negative emotions, so I just do it.

What makes you nostalgic?

Hmmm, my grandparents. Like their stuff and their old house (which they recently sold to my third cousin). They gave me a trousseau which has been in my grandmother’s family for some generations that always stood beneath the stairs. They used it for keeping firewood ^w^ I really love old style furniture and stuff and this was something I really wanted. Also since they are getting old and aren’t at best health I feel like this is something that can remind me of the best days when they were still up and about, full of energy. *le sobs*

A Favorite word?

Guuurl, this is a really hard question. I found one before once when I was scrolling words for prompts. “Lucida” which is the brightest star in a constellation. I like stars and astrology and zodiacs and such, so Lucida is nice in that way, but it also sounds beautiful. tbh I could name one of my children Lucida because of it. :)

My eight questions:

If you could go anywhere in the world, where would you go?

If you met you fave and had to choose one thing/sentence to tell them what would it be?

What book is your favorite?

Name a character from a movie/book/series from your childhood that have left an impact on your life?

Cats or dogs? (I’m not kidding here. Choose)

If you were to travel the world and had to choose 5 things to bring, what would it be (money excluded)?

Your motto?

A possession that means a lot to you?

Ok I summon: @librarianknights @lerrryyyyy @by-ca ... who more... shit I barely talk to people here these days... wait... @haru2115 (you were so kind and told me a bit about ldh so yeah ^^) I give up... just whomever can answer xD

1 note

·

View note

Text

Keeping Secrets

Modern!AU

Master Lists: Drabbles/Imagines, and Completed Series

“Morning class,” you say as the bell rings.