#chicano moratorium march

Text

Chicano Moratorium

“The Chicano Moratorium, formally known as the National Chicano Moratorium Committee Against The Vietnam War, was a movement of Chicano anti-war activists that built a broad-based coalition of Mexican-American groups to organize opposition to the Vietnam War. Led by activists from local colleges and members of the Brown Berets, a group with roots in the high school student movement that staged walkouts in 1968, the coalition peaked with a August 29, 1970 march in East Los Angeles that drew 30,000 demonstrators. …”

W – Chicano Moratorium, W – Brown Berets, Union del Barrio, W – “Strange Rumblings in Aztlan” by Hunter S. Thompson

Chicana-Chicano Agonists, These Pictures Capture The Raw Energy Behind The Chicano Movement, In the Chicano Movement, Printmaking and Politics Converged

W – Chicano, W - Chicanismo, W – Chicana feminism, W – Aztlán, W – TELACU

W – Las Adelitas de Aztlán, W – Rosalio Muñoz, W – Gloria Arellanes, W – Soledad Alatorre

YouTube: The Chicano Moratorium: Why 30,000 People Marched Through East LA in 1970, Chicano Moratorium, National Chicano Moratorium Committee East Los Angeles protest August 29, 1970, LA Raza at the Autry: Exhibit highlights social protest photography, 5 Things To Know About The Black Panthers

August 29, 1970: A Day Every Chicana/o Must Always Remember

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

New mural at Salazar Park, unveiled on the 53rd anniversary of the National Chicano Moratorium March which ended at Salazar Park, then called Obregón Park.

1 note

·

View note

Text

“Lessons About Police Brutality from the Chicanx Experience” by Joseph Orosco

Summary of Key Points

This essay provides a very brief summary of some notable incidents of police brutality and corruption from the Chicanx perspective. These include:

The Texas Rangers, who were specifically formed to patrol the Texas-Mexico border, were brutal. They abducted and murdered hundreds of Mexican-Americans from 1915-1919 during a period known as La Hora de Sangre.

In 1942, in an incident known as the Sleep Lagoon Murder, over a dozen Mexican-American youth were arrested in connection with the death of a Chicano man. They were denied lawyers, were forced to appear in court in dirty clothes, and they were stereotyped as “violent” and “savage” by experts for the prosecution. They were taken away from their families and sent to reform school despite shaky evidence.

In 1951, in an incident known as Bloody Christmas, the LAPD arrested a group of young Mexican-American men. During a Christmas party, LAPD officers forced beat the men with clubs, resulting in severe injuries. Though initially covered up, families of the men joined up with Community Services Organization (CSO), a grassroots civil rights organization, to pressure the city. A review led to several convictions and many reassignments.

The Chicano Moratorium March was a nonviolent demonstration against the Vietnam War, in August 1970. 30,000 people showed up. When a nearby business was broken into, LAPD declared the entire assembly unlawful, attacked protestors with tear gas and other less-lethal weapons, injuring many and killing some, including a journalist.

These incidents reveal that police brutality and racism is not restricted to anti-Black racism.

#abolition study group#week 1#joseph orosco#police brutality#chicanx#chicanx history#abolition#abolish cops#study#studyblr#bloody christmas#sleepy lagoon#la hora de sangre#chicano moratorium march#defund the LAPD#cso#mexican american#defund the police#defund ice#texas rangers

22 notes

·

View notes

Link

That Saturday was muggy and filled with smog, but an estimated 25,000 Angelenos still made their way to East LA’s Whittier Boulevard to march against the Vietnam War. Sheriff’s deputies began the day peacefully directing traffic, following Pitchess’ instructions to keep a “low profile.” But around 1:30 in the afternoon, hundreds of additional deputies arrived on the scene outfitted in riot helmets. Los Angeles historian Mike Davis, who was there that day, writes in his book Set The Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties, “after a desultory warning that the rally was an ‘unlawful assembly,’ they began pushing, prodding, and–where there was any resistance–beating people.” Deputies arrested roughly 150 people and four more were killed, including journalist and law enforcement critic Ruben Salazar.

The night before his death, Salazar informed friends and colleagues that he suspected he was under police surveillance. He was hit with a tear gas projectile as he sat inside a café drinking a beer with his team, waiting for things to calm down outside. Deputy Thomas Wilson, who fired the fatal shot, was never disciplined for his actions.

Salazar’s death ignited criticism of the department and resulted in the longest coroner’s inquest in the County’s history. Salazar’s family eventually settled with the County for $700,000. Pitchess maintained “there was absolutely no misconduct on the part of the deputies involved [in the incident] or the procedures they followed.” However, three years later in an internal memo, department management acknowledged the first deputy gang: the Little Devils. Members allegedly inflicted violence on demonstrators during the Chicano Moratorium. Captain R.D. Campbell compiled a list of 47 known members with the signature red devil tattoo, but it isn’t clear if anyone was disciplined.

Deputies working at the East Los Angeles Station appeared to take pride in the terror they inflicted on the community during the Chicano Moratorium – a now infamous logo for the station immortalized the violence wrought that day. The Fort Apache logo depicts a police riot helmet over a boot within a circle of mottos reading “siempre una patada en los pantalones,” which translates to “always a kick in the pants.” The other motto, “Low Profile,” appears to mock Pitchess’ instructions to the deputies on duty at the Chicano Moratorium. The logo was banned by Sheriff Jim McDonnell in 2016 because he found it to be “disrespectful” to the East LA community. The Fort Apache reference dates back to a 1948 John Ford western of the same name. The story is centered on a remote U.S. cavalry outpost surrounded by enemies whom the white officers regard as dangerous “savages.” Current Los Angeles Sheriff Alex Villanueva revived the logo shortly after he took office in 2018, but declined to comment on why. Villanueva worked at the station earlier in his career, and even met his future wife there.

good series of 5 articles

39 notes

·

View notes

Photo

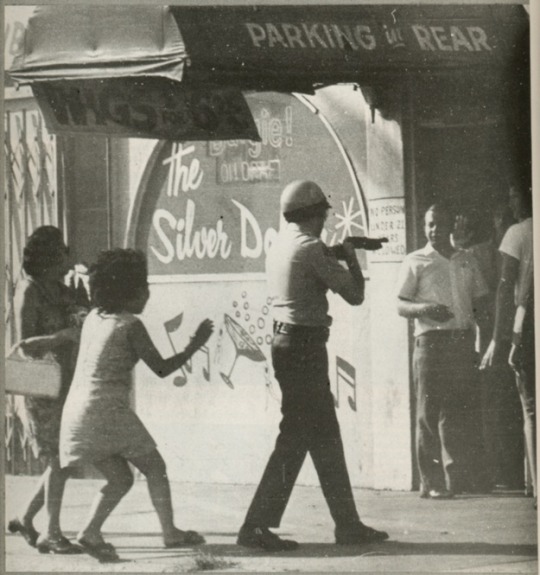

50 Years On I grew up a block from where this scene takes place. In fact, if I stood in the middle of our street, I could see the Silver Dollar Bar. In 1970, I was an 11-year-old kid, who had already seen a lot of what the world was like, starting with the assassination President Kennedy in ’63. Mostly, I remember all the people on my block coming out of their houses, crying and consoling each other. Hugs across the chain link fence. Then in ’65, just months after the murder of Malcolm X, the Watts Rebellion (my maternal grandparents lived less than five miles from the flash point). In 1968, Dr. King was killed in Memphis, followed shortly thereafter by Senator (and Presidential candidate) Robert F. Kennedy in June. We watched it happen in real time on television. In March of that year, my father took me to see RFK speak at the Greek Theater, here in Los Angeles. My politics have veered further left with each passing year, but they were initially instilled in me by my Mexican American, Teamster Shop Stewart, Father. Together, we watched the Vietnam War, with its updated body count and graphic footage delivered nightly via the 6 O’clock News. A disproportionate number of these casualties were from communities just like mine. On August 29, 1970, a group of activists sought to call attention to this fact, along with other injustices, including but not limited to Police Brutality, with a march called The Chicano Moratorium. The march went through the major business district in East Los Angeles, along Whittier Blvd, to Laguna Park (now Salazar Park), where everyone gathered to hear the speakers of the movement that were on hand. My dad packed up his camera and went to Laguna Park on this day, purposefully leaving me behind at home with my mother. About an hour later, I slipped out the door and walked up the street from our house and stood in front of Discount Records, directly across the street from the Silver Dollar Bar to watch the event. It would not be my last experience with direct action, but it was my first. When the march was over, I walked home and waited for my dad to return from the park. When he did, he said, “I’m glad I didn’t take you, son, because the Sheriffs started busting things up”. He managed to slip away to his car before things too ugly. He walked with a limp (from childhood Polio) and used a cane and could not afford to get stuck in a melee. We looked at his polaroids of the first use of teargas at the park. The day, of course, was to get much worse than what he had witnessed. There would be death and destruction. There would be bloodshed and tears shed and more hot August nights to come. (You can read more about the events of the day and beyond here). Postscript: It was a few years later that finally I told him I went to see the march on my own. He nodded his head, as if to say, “of course you did”. Rest in Peace, Ruben Salazar. Photo by Raul Ruiz

121 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Recent mural by 3B Collective commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Chicano Moratorium, a broad-based coalition of groups raising awareness of the Vietnam War as a civil rights issue: Mexican-Americans were dying in disproportionate numbers in the war. The movement’s march along Whittier Blvd on August 29, 1970 reportedly drew 30,000 people, was met with a violent response from the LAPD, and led to the death of acclaimed journalist Ruben Salazar under suspicious circumstances. Mural location: 4840 Whittier Blvd, East Los Angeles.

#chicanomoratorium#3bcollective#brownpower#rubensalazar#abolishice#larazaunida#laluchasigue#lacausa#mexicanamericanliberation#mural#art#laart#urbanart#publicart#streetart#streetartla#lastreetart#eastla#eastlos#eastlosangeles#la#losangeles#impermanentart

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The ‘70s Turn 50: Celebrating the Decade that Broke the Mold

The 1976 Bonaventure Hotel is an iconic 1970s building in downtown L.A. Photo by Architectural Resources Group.

The Los Angeles Conservancy celebrates the 1970s’ golden anniversary with The ‘70s Turn 50, an exciting initiative exploring the decade’s lasting imprint on L.A. County’s built environment. This yearlong campaign will raise public awareness and educate Angelenos about 1970s architectural and cultural heritage sites in Los Angeles.

Why Fifty Years?

The fifty-year mark is significant in historic preservation. One of the criteria for designation on the National Register of Historic Places states that properties under the age of fifty should not be considered eligible unless they are of “exceptional importance.” While there is no age limit in Los Angeles for local landmark designation, the fifty-year rule remains a benchmark for examining buildings and structures from a period not yet long-gone. It serves as a rallying cry for preservationists anxious to spotlight places that may be at risk.

In 2010, the Conservancy leveraged the 1960s’ fiftieth birthday to shine a light on the growing number of lost or threatened buildings from that decade. Increasing public awareness and pressure helped spare some threatened ‘60s buildings.

The 1966 Fairmont Century Plaza (formerly, the Century Plaza Hotel), which had faced potential demolition, was successfully saved thanks to massive public support and a sensitive redevelopment plan brokered by the Conservancy and the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

Instilling value for structures not yet in our collective consciousness is half the battle when it comes to preserving them. However, those most in need of attention are in constant flux, moving targets based on the time and changing trends.

Threats to the ‘70s

In the decade since the Conservancy launched its efforts to preserve resources from the 1960s, structures from the 1970s have moved increasingly into the cross-hairs—especially those made with faltering building materials.

Gasoline shortages caused by the 1973 oil embargo quickly curtailed the postwar housing explosion in the United States, a boom that had resulted in the construction of roughly six million housing units in California. Construction shrank as ‘stagflation,’ a term coined in the ‘70s to describe the simultaneous occurrence of slow economic growth and high rates of inflation, gripped the country. The subsequent emphasis on cheap construction materials resulted in buildings that were difficult and expensive to maintain.

1970s buildings also face an increased threat due to a lack of enthusiasm for the aesthetics of the era. The design features and fads iconic to it (shag carpet, faux wood-grain paneling, platform shoes, and macramé) tend to be polarizing ones, and its architecture may be equally difficult for many to embrace.

A Time of Experimentation

Yet in Southern California, the ‘70s marked a time of unprecedented architectural exploration, and the structures left in its wake are some of the finest examples of that creative spirit. Large architectural firms expanded beyond the plain International Style glass box with a variety of building shapes and experimented with glass-skinned exteriors that gave their corporate commissions a simple yet beautiful aesthetic.

The Westin Bonaventure Hotel (John Portman, 1976), the colorful Pacific Design Center (Pelli and Gruen Associates, 1975), and the Federal Aviation Administration Headquarters (César Pelli, Anthony J. Lumsden, DMJM, 1972) exemplify the originality of the decade.

Simultaneously, schools of architecture, such as the newly formed Graduate School of Architecture and Urban Planning at UCLA; the School of Environmental Design at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona; and the radical Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc), joined the ranks of the University of Southern California’s established architecture school in producing many of the leading architects of the time. Craig Hodgetts, Robert Mangurian, Thom Mayne, Michael Rotondi, Eric Owen Moss, Eugene Kupper, and Frederick Fisher all taught at these institutions, which provided them the means to experiment despite limited budgets.

Frank Gehry’s 1978 re-design of his Santa Monica residence using cheap and accessible materials was the first project to bring him significant attention. It catapulted the Los Angeles Deconstructivism movement onto the national stage.

The colorful Pacific Design Center’s first building, the Blue Building, rose at the corner of Melrose Avenue and San Vicente Boulevard in West Hollywood in 1975. Photo by Adrian Scott Fine/L.A. Conservancy.

Movers and Shakers

On the social and cultural front, the ‘70s were a crucible for movements. The Los Angeles Conservancy, Whittier Conservancy, Pasadena Heritage, and many other preservation and heritage groups were founded in the 1970s in response to the demolition and threatened destruction of historic sites across the County.

Similarly, the environmental movement, which gained national attention with landmark legislation, such as the National Environmental Protection Act, the Clean Water Act, and the Endangered Species Act, solidified in Los Angeles through the efforts of new organizations like TreePeople and the California Conservation Corps.

Begun in the ‘60s, the battle for civil rights continued, now in tandem with and alongside anti-Vietnam War marches and protests. The Chicano Moratorium took place in 1970, imprinting East Los Angeles with the memories of its message, marchers, and casualties. In the following years, both the women’s and LGBTQ+ liberation movements would make their presence known across Southern California, as well. Despite Tom Wolf’s descriptor of the 1970s as the “Me” decade, Los Angeles retained strong elements of civic engagement and activism.

Celebrating the ‘70s

The Conservancy will explore all of this and much more through The ‘70s Turn 50 initiative. Throughout 2020, we will tell the stories and explore the legacies of the 1970s in a variety of ways, including:

Holding a yearlong tour and discussion series at significant ‘70s buildings across the County.

Hosting special tours of buildings and sites of architectural and cultural importance.

Nominating structures from the decade for landmark designations.

Launching a social media campaign and a new ‘70s-centered microsite.

Most importantly, we will build a coalition of fellow organizations eager to join us in this enterprise. We hope that Conservancy members and citizens of Los Angeles County will create a force for valuing and preserving the rich heritage and unique culture of the 1970s.

Visit our microsite at laconservancy.org/70sTurn50 to learn more about this initiative, our programming partners, and upcoming events celebrating the 1970s. We will add more content and announce additional events throughout 2020.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#Repost @reporter.arce ・・・ Today marks the 49th anniversary of the Chicano Moratorium and the killing of Ruben Salazar. He was the news director at KMEX Univision in Los Angeles in the late 60s. He was also a columnist for the LA Times. More importantly, many in the Mexican-American community considered him their only voice in a society that looked down upon Mexicans. Racism was rampant, police misconduct was routine, dropout rates were high, many young Chicanos were dying in Vietnam (some 20 percent of all war-time casualties) and the media seemed to ignore our plight. On August 29, 1970, more than 40,000 Chicanos took to the streets of East LA to denounce these injustices. The LA County Sheriff's were ordered to forcibly disperse the crowd. Hundreds were injured, dozens were arrested and five people - including Salazar - were killed. The journalist was inside the Silver Dollar Bar about a mile up the road taking a break from covering the march & rally when a Sheriff Deputy fired a tear gas missile into the bar. The missile entered and exited Salazar's head, killing him instantly. Sheriff Deputies contend it was an accident yet most in the Chicano community were suspicious because Salazar reported heavily on police misconduct. 40 years later, I was given access to the Sheriff Department's private files on Salazar. The pictures are gruesome. The collection is telling: Deputies collected surveillance on nearly all the militant/radical groups of the day. They even kept tabs on mainstream Mexican-American politicians and celebrities. The Department - and even an independent investigator - say it was all an accident. But many people who took part in the march and who remember those times refuse to accept that answer. Ruben Salazar presente! #RubenSalazar #journalism #journalist #DangerousProfession #Mexican #Chicano #ChicanoMoratorium #LosAngeles #EastLA #WhittierBoulevard #AllPowerToThePeople #1970 ➡️ #mextasy for the memory of his work and legacy #nomextasy for his murder https://www.instagram.com/p/B11HaK6gmXE/?igshid=yydmjpoenq7g

#repost#rubensalazar#journalism#journalist#dangerousprofession#mexican#chicano#chicanomoratorium#losangeles#eastla#whittierboulevard#allpowertothepeople#1970#mextasy#nomextasy

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Appearing on Chicana punk rock musician/songwriter Alice Bag’s second album Blueprint (2018), here’s a very relevant song about the way the criminal justice system - in America, especially - has repeatedly failed people of color throughout history.

From an interview with Alice, this is what’s said about the song, including the inspiration behind it:

“White Justice,” another collaboration, features vocals from Martin Sorrondeguy of Los Crudos and Limp Wrist. The song is about the Chicano Moratorium anti-war march through the streets of East Los Angeles on August 29, 1970. The protest was in response to how disproportionate numbers of Chicano soldiers were drafted and sent to dangerous places to die.

Bag was there: “During the march, the riot squad came out and started launching tear gas at the participants. It just turned into this chaotic situation.” More than 150 were arrested and four were killed, including the journalist Rubén Salazar.

“The news outlets reported it as a riot,” Bag recalls. “They made it seem like we had taken to the streets causing trouble, when in fact that protest had been very peaceful. People were to meet at the park afterwards. There were young kids dancing. They had food vendors and speakers and music. It was never this angry, chaotic thing that they portrayed.”

Bag wrote the song in 2016 when her friend put together a tribute event to honor the overlooked women of the early Chicana movement. A group of songwriters participated in story circles and discussion groups, and they each chose a person or event to write about.

When Bag decided to write about the Chicano moratorium, one of those early Chicana movement organizers told her, “If you really want people to connect it to change, and not just to remember history, [you have to] connect it to the present day.”

“You have to see what went wrong back then and what’s going wrong now.”

On “White Justice,” Bag connects this piece of protest history to the way protests by people of color are still policed today.

“When a person of color tries to protest, suddenly it turns into something that has to be shut down with deadly force. As a society we don’t take the time to reflect on why people are upset and why people are asking for a change of policy,” Bag contends. ‘In my experience as a person of color, it seems that it’s just like, ‘shut them up by any means necessary,’ and if a few brown or black people die, it’s seen as what’s needed to maintain the status quo. So we’re sacrificed.”

“Gray smoke in ’70. I still choke when I stop to think. Our struggle then was here at home. And it’s still going on,” Bag sings. “You say justice is colorblind. But I know you’re lying. I know you’re lying. White justice doesn’t work for me.”

“I was thinking of the Black Lives Matter movement,” Bag says. “We have to reflect on how the justice system is not working for people of color.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Los 5 Puntos, 3300 E Cesar Chavez Ave., Los Angeles (Boyle Heights), CA 90063

There are many places to get tacos and Mexican food in Boyle Heights/East LA, but Los 5 Puntos stands out for several reasons. The location is one of these – it’s named after the five points intersection of Cesar Chavez Avenue, Lorena Blvd., and Indiana Street. This is also where you can find a memorial dedicated to the Mexican American veterans of World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War. And, it was the starting point of the first Chicano Moratorium march in protest of the Vietnam War in East Los Angeles. This place is part of East LA’s history.

And then there’s the food. Los 5 Puntos is a Mexican delicatessen/carniceria. Established in 1967, the food is made from scratch, authentic, and delicious. It’s still popular today. I could smell the masa from outside the building. Once inside, I was a bit confused because there were multiple lines and a sign that said “line starts here.” People weren’t standing under the line starts here sign. I am not sure how it works but I think there is one line and multiple cashiers. The person at the start of the line goes to the first open cashier. There might be a separate line for to go orders, but I can’t read Spanish, so I’m not sure.

It’s a large place with lots of people and lots of food. They have burritos, tortas, tacos, flautas, enchiladas, sopes, quesadillas, tamales, menudo (weekends), tostadas, and meat by the pound. Their tacos are considered to be among the finest in LA. The carnitas tacos seem to get the most mentions.

Meat choices: Asada, buche, lengua, rinones (kidneys), cuerrito (pig skin), trompas (lips or snout?), carnitas, pollo, chicharron, tripas and carne de res

I have to respect a place with unusual meat choices. The tacos ($2.69) are made to order. Cheese, guacamole, or sour cream are extra. There is no self-service salsa bar but they do have a salsa bar and a massive tub of nopales salad.

* Two tacos and a 20 oz Coke ($6.99): Normally two street tacos aren’t enough to fill me up. But the tacos here are not street tacos. Two L5P tacos are very filling. First the handmade corn tortillas are much thicker and larger than your street taco tortilla. They’re almost like plain pupusas. They’re made throughout the day, I think. I saw a woman making them while I was there. You get one tortilla per taco. Mine did get soggy and fell apart because of the salsa, meat juices, and nopales salad. Wow, the meat was in HUGE chunks. Maybe these were the biggest chunks of meat I’ve had in a taco. They were generous with the amount of meat. The lengua was tender and the trompas was tender too. I’m not sure what trompas are but whatever I ate was fatty and soft. I liked the spicy salsa though I asked for their spiciest and it wasn’t crazy spicy. The nopales salad was very nice too – with big strips of soft nopales, chopped tomatoes, onions and cilantro. I added guacamole which was nice and chunky. I need to eat these tacos with a fork next time. I planned to take them to go but they didn’t package them as a to go order, so I ate it there. The tortillas would have gotten even soggier had I waited to eat. The wetness of the tacos is an issue but they were delicious.

They also sell drinks, lottery tickets and some groceries. There are only three small tables inside and a few on the sidewalk. They have their own parking lot. I saw people eating in their cars.

Service was super friendly and nice. He didn’t even charge me for my guacamole.

4.5 of 5 stars

By Lolia S.

#Los 5 Puntos#los cinco puntos#Mexicatessen#Mexican deli#carniceria#tacos#burritos#tortas#flautas#sopes#Boyle Heights#East LA

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Two female Brown Berets stand together in matching uniforms during a National Chicano Moratorium Committee march in opposition to the war in Vietnam in Los Angeles on Feb. 28, 1970.

0 notes

Photo

The Chicano Moratorium

On August 29, 1970, as many as 30,000 Chicano anti-war activists marched in East Los Angeles to protest the Vietnam War. The march, organized by the grassroots coalition the Chicano Moratorium (formally known as the National Chicano Moratorium Committee Against the Vietnam War), was the biggest anti-war demonstration undertaken by any ethnic group in the nation. Gathering in Laguna Park, marchers headed down Whittier Boulevard as L.A. county sheriff’s deputies, declaring the rally an unlawful assembly, attempted to break it up with tear gas and batons. Storefronts burned in the ensuing violence and four people were killed, among them the award-winning Los Angeles Times journalist Rubén Salazar. Salazar and others had sought refuge from the chaos in a local bar, the Silver Dollar Bar and Café. A sheriff’s deputy fired a tear gas canister into the establishment, which struck and killed Salazar. No charges were filed. The former Laguna Park is now Ruben F. Salazar Park.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Chicano Moratorium

Was the Chicano Moratorium successful?

Despite an otherwise peaceful rally, Los Angeles sheriffs fired on protesters with tear gas and billy clubs, resulting in the deaths of three people. ... The Chicano Moratorium was so much more than a successful march and rally infiltrated by the sheriffs.

The Chicano Moratorium, formally known as the National Chicano Moratorium Committee Against The Vietnam War, was a movement of Chicano anti-war activists that built a broad-based coalition of Mexican-American groups to organize opposition to the Vietnam War.Background · March in Los Angeles

1 note

·

View note

Quote

The casual nature of the police violence in this case, and the easy manner in which police were able to deploy weapons in a deadly way, demonstrated to many Chicanxs that mainstream America would not tolerate even nonviolent dissent from people of color.

Joseph Orosco on the Chicano Moratorium March

“Lessons About Police Brutality from the Chicanx Experience”

#abolition study group#week 1#joseph orosco#abolition#police violence#chicanx#chicano moratorium#nonviolent#abolitionism#mexican-american#protest#defund the police#abolishthepolice#study#studyblr#abolish cops

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"La Causa" (The Cause), 2011

"This is one of two paintings I created especially for ¡ADELANTE!, an exhibit of Chicano art at the Forest Lawn Museum in Glendale, California. La Causa is a portrait of militants from the Brown Beret organization, a Chicano group that gained notoriety in the late 1960s for struggling to advance the civil and human rights of Mexican-Americans.

The Chicano Moratorium march againt the Vietnam War took place in East Los Angeles on August 29, 1970, and was partly organized by the Brown Berets. The group originally organized in East L.A. in 1967 as an outgrowth of the burgeoning Chicano civil rights movement. In 1968 the group organized the first student walkouts to protest racism and substandard schools in East L.A., electrifying an entire generation. Soon Brown Beret chapters sprang up throughout California, Arizona, Texas, Colorado, New Mexico, and beyond - but it all started in the city of Los Angeles.

Some 30,000 people took part in the 1970 moratorium march, which culminated in a rally at Laguna Park; dozens of Brown Berets acted as marshals, providing security for the protest. The L.A. County Sheriff’s Department attacked the gathering, initiating a riot. Ultimately police killed four citizens that day, Lyn Ward, José Diaz (both Brown Berets), Gustav Montag, and L.A. Times reporter Rubén Salazar. Salazar was slain as he sat in the Silver Dollar Café; a deputy sheriff fired a tear gas projectile into the cafe, striking Salazar in the head and killing him instantly."

Artist: Mark Vallen

115 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

same day essays

About me

Essay

Essay The virus is particularly a threat for essential employees and the formerly incarcerated, but the virus and the methods that make it so deadly threaten us all. It turned clear that the younger men and women I noticed graduate, had graduated not only into a health disaster, but in addition into a joblessness crisis. By day’s end, lots of were arrested and trailblazing Latino journalist Ruben Salazar was dead. On Aug. 29, 1970, a minimum of 20,000 demonstrators marched by way of East Los Angeles to protest the disproportionate variety of Mexican American service members dying within the Vietnam War. His throughline — Chicanos are misunderstood, angry and discriminated in opposition to — struck me as unoriginal. Because his job could not be accomplished remotely, he was furloughed, however paid because of an extra in paid time off. It was too akin to a condition he had long wished to overlook—imprisonment. But at the time, Ángel’s near-death experience solely led him additional on a path of self-destruction. At Brooklyn Woods, BWI’s woodworking program, I met Ángel Pérez, a foreman for this system’s social venture. Ángel makes vanities and cupboards for local housing developments whereas coaching latest woodworking graduates to do the identical. Salazar was snug among politicos and Brown Berets, cholos and businessmen. The subjects Salazar lined nearly 60 years ago read just like the headlines your woke friends publish on Facebook at present. Immigration, health and education disparities amongst Mexican Americans. I tried to volunteer, whilst all the senior residents I work with stayed residence. Over the subsequent eight months Salazar produced a outstanding string of writing for The Times, till his life was all of a sudden ended at a protest march on Aug. 29. His biggest fear was, and remains, infecting his young son who's already combating his personal battle. Work is not the sanctuary it was once; it’s a danger. Heriks, then again, grew to become an important worker, as folks still want heat and hot water in a pandemic. But with every passing day, he was hearing about yet one more resident or colleague that had gotten contaminated. Almost instantly, Ángel and I bonded over our mutual Latin American heritage and shared Brooklyn neighborhood. He was always making me laugh and displaying me his latest creations. Every day he walked into the woodshop with a huge smile and a tape measure at his side, ready for whatever the day requested of him. In early March, when it was changing into increasingly clear that the coronavirus was beginning its silent, however quickly to be crushing, assault on New York City, I continued to reside my life as I at all times had. I rode the subway, even as I saw it getting emptier by the day. On Jan. 18, 1969, he gave a speech at a San Antonio convention held by the U.S. Department of Justice to look at how media depicted Mexican Americans. Four days earlier, Salazar had filed his first story for his new Chicano task. The National Chicano Moratorium Against the Vietnam War started out peacefully, but that afternoon a minor disturbance touched off skirmishes between demonstrators and legislation enforcement. The writing appeared labored, explanatory, geared towards a gabacho audience. The guide is one of the few easily obtainable ways to read Salazar’s work, even in this Internet age, and it remains in print. My colleague Ben Welsh has put together an online archive of some of Salazar’s stories and columns from 1970, the 12 months he died. But my favorite Salazar piece is an Oct. 21, 1962, story titled “Case History of a ‘Rumble’ — Who’s to Blame? ,” a examine of a brawl between white and Mexican gangs in Pico Rivera.

0 notes