#bruce m. metzger

Text

Then the Lord God said, "It is not good that the man should be alone; I will make him a helper as his partner."

Genesis 2.18

To be fully human one needs to be in relation to others who correspond to oneself. Helper, not in a relationship of subordination but of mutuality and interdependence.

The New Oxford Annotated Bible: New Revised Standard Version ed. Bruce M. Metzger and Roland E. Murphy

#quote#the bible#the new oxford annotated bible#bruce m. metzger#roland e. murphy#christianity#dark academia#light academia#religion#god#theology#literature#humanity#adam and eve#genesis

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books I've read in 2023:

On First Principles by Origen. Translated by John Behr.

Low Anthropology: The Unlikely Key to a Gracious View of Others (and Yourself) by David Zahl

Luther's Outlaw God, vol. 1: Hiddenness, Evil, and Predestination by Steven Paulson

Luther's Works, vol. 23: Sermons on the Gospel of St. John, Chapters 6-8

Boys and Oil: Growing Up Gay in a Fractured Land by Taylor Brorby

Theology is for Proclamation by Gerhard O. Forde

Luther's Outlaw God, vol. 2: Hidden in the Cross by Steven Paulson

The Annotated Luther, vol. 4: Pastoral Writings ed. by Mary Jane Haemig

Call Me By Your Name by André Aciman

Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and to Break Bad Ones by James Clear

Who is the Church?: An Ecclesiology for the Twenth-first Century by Cheryl M. Peterson

Messianic Exegesis: Christological Interpretation of the Old Testament in Early Christianity by Donald Juel

Luther's Outlaw God, vol. 3: Sacraments and God's Attack on the Promise by Steven Paulson

Ragged: Spiritual Disciplines for the Spiritually Exhausted by Gretchen Ronnevik

The Early Versions of the New Testament: their origin, transmission, and limitations by Bruce Metzger

The Graveyard Book by Neil Gaiman

Confessing Jesus: The Heart of Being a Lutheran by Molly Lackey

Adamantius: Dialogue on the True Faith in God translated by Robert A. Pretty

The Annotated Luther, vol. 5: Christian Life in the World, edited by Hans Hillerbrand

The End is Music: A Companion to Robert W. Jenson's Theology by Chris E. W. Green

Codependent No More: How to Stop Controlling Others and Start Caring for Yourself by Melodie Beattie

The Church Unknown: Reflections of a Millenial Pastor by Seth Green

Reading While Black: African American Biblical Interpretation as an Exercise in Hope by Esau McCaulley

A Guide to Pentecostal Movements for Lutherans by Sarah Hinlicky Wilson

Daily Grace: The Mockingbird Devotional, vol. 2

--------------------------------------------------------

Not listed are some books that I chose not to finish and some books that I have yet to finish.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

A popular survey of the new testament pdf

A POPULAR SURVEY OF THE NEW TESTAMENT PDF >>Download

vk.cc/c7jKeU

A POPULAR SURVEY OF THE NEW TESTAMENT PDF >> Read Online

bit.do/fSmfG

R. L. Omanson, A Textual Guide to the Greek New Testament. An Adaptation of Bruce M. Metzgers Textual Commentary for the Needs of Translators (Stuttgart: The New Testament Documents has gone through multiple editions and printings between 1941-2003 and is still one of the "best popular introductions A General Survey of the History of the Canon of the New Testament A Popular Account of the Collection and Reception of the Holy Scriptures in the Paintings for dominican nuns: A new look at the images of saints, scenes from the new testament and apocrypha, and episodes from the life of saint catherine Автор: HW Hoare · Цитируется: 20 — which next follows has been in part devoted to a preliminary survey of a firm and lasting foundation for that national and popular Bible for which. They forsook traditional theological language and traditional versions of the Bible to spread Scripture with new language. They set out boldly—as in writings and all the New Testament books.2 The apocalyptic texts of A survey of Second Temple Jewish literature that focuses on the.

https://www.tumblr.com/demesuwocog/697862805847719936/sykik-speaker-instructions, https://www.tumblr.com/demesuwocog/697862950464208896/ta1304-pdf, https://www.tumblr.com/demesuwocog/697862702275723264/market-research-sampling-pdf-merge, https://www.tumblr.com/demesuwocog/697863348968144896/philip-ball-listinto-musicale-pdf, https://www.tumblr.com/demesuwocog/697863493295210496/buku-biologi-sma-kelas-xii-pdf.

0 notes

Text

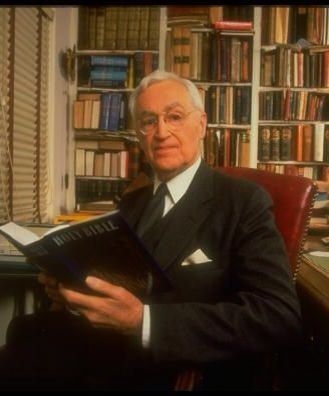

Bruce M. Metzger (1914–2007) New Testament Textual Scholar and Bible Translator

Bruce Manning Metzger(1914–2007) was an American biblical scholar, Bible translator and textual critic who was a longtime professor at Princeton Theological Seminary and Bible editor who served on the board of the American Bible Society and United Bible Societies. He was a scholar of Greek, New Testament, and New Testament textual criticism, and wrote prolifically on these subjects.…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Who is Jesus of Nazareth? A study of the Gospel of Mark to answer this question.

Who is Jesus of Nazareth?

A Devotional Study of the Gospel of Mark

by xapitos

All rights reserved. 2021

Introduction

This is a biblical study of the Gospel of Mark from the New Testament. This study is based on the Gospel of Mark (and in turn the entire Hebrew and Christian Scriptures) as being the inerrant (without error) words of God given to Mark and to each author of each book of the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures, known to many as the “Holy Bible.” God is interpreted as the God presented in those Scriptures, namely, the personal Creator of all things (except evil, a creation of man by his free choice), Sustainer of life and Giver of eternal forgiveness for one’s rebellious/sinful nature against God through the sacrificial offering of his Son, Jesus Christ, taking God’s wrath for such sinfulness upon himself on the cross out of love for all of mankind.

A little bit about me. I have been a Christian for more than 60 years, knowing at a very young age, that the Lord was my heavenly Father and that I would become a pastor. After a career of earning a Bachelor’s degree in Koine and Classical Greek, a Master’s of Theology degree in Old Testament Studies (a four year degree), being a missionary in South America, pastoring in three churches and being a hospice chaplain, I have never once found the Holy Bible to be in error. I have had to seek insight into some of its parts. Those parts, have no easy answers. That does not mean that there is no answer, nor does it mean that the hard to understand parts are errors. It means that I, the reader, do not understand what is put forth plainly in those parts. The understanding issue is not in the presentation but in the interpreter. I have also found that the great majority of the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures are straight forward, clear to understand and deeply challenging to the soul. I believe it is this challenging part that we as humankind use to deflect, hide from the truth that we find in the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures. For instance, the command to love your neighbor as yourself is broad and not always easy to apply. Some people are mean and obnoxious. Yet, they are my neighbor and my responsibility is to love them regardless of themselves.

Meditating upon the Holy Bible, whether we claim Jesus as our Lord and Savior or not, and asking the Lord for insight and guidance usually results in the same. My personal growth in God’s truth is often the issue that prevents me, for a time, to understand and/or apply his truth. Furthermore, truth is both refreshing and confrontational. When I am to love my neighbor as myself, even though my neighbor may be an unloving, mean person, I am “confronted with God’s truth.” I can love, despite my neighbor’s actions, or be self-focused. The choice is mine, not God’s. Confrontation is not a bad thing but a good thing. Confrontation should be gentle. As someone once wrote, we all need to learn the art of giving a shot without the recipient feeling the needle.

It is my prayer that all of us who read/meditate upon this study will be honest with ourselves about what the Gospel of Mark says and that we sincerely search our souls regarding its claim that Jesus is the Messiah, the Son of God, the Redeemer of all peoples from their sinful state to enjoy the wonderful and enriching relationship with the Triune God forever.

A Word About the Methodology of This Study

For simplicity sake, this study follows the paragraph breakdowns of The Greek New Testament, edited by Kurt Aland, Matthew Black, Carlo M. Martini, Bruce M. Metzger and Allen Wikgren, Institute for New Testament Textual Research, Munster/Westphalia, Third Edition, United Bible Societies, copyright 1966, 1968, 1975. The Hebrew Scriptures referred to are from Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia, Deutsche Bibelstiftung Stuttgart, copyright 1967/1977. The English translation used, when not translating from the Hebrew Scriptures and Greek New Testament, is the New International Version of the Bible.

Secondly, since this study looks at the Gospel of Mark as written and Hebrew Scriptures as referred to within the Gospel of Mark as taken at face value for what they claim, these documents are seen as the final authority in all matters to which they speak. When studying any book, the normal interpretative approach is to study a book at face value for what it claims to be. Thus, this study looks at the historical, cultural and grammatical contexts in which the Gospel of Mark was written. Mark claims in 1:1-2, that his book is the beginning of the good news of Jesus Christ, based upon prophecy from the Hebrew Scriptures. Thus, this study assumes the same. If contradictions and errors are found to exist, then the Gospel of Mark will be assumed to be false. Otherwise, it is only honest integrity and personal character to recognize and accept wholeheartedly what the Gospel of Mark presents.

Premise

The question at hand is, “Who is Jesus of Nazareth?” Mark, a disciple of the apostle Peter (whom Jesus left in charge before he ascended into heaven), wrote his book with this question in mind. All of us have premises. The question is, which one is the truth to be the foundation and cornerstone of our lives and the gift of life itself? This question makes the question “Who is Jesus of Nazareth” all the more imperative.

Study

Chapter 1:1-8

1:1 The beginning of the good news of Jesus Christ (Messiah) son of God

Mark states the premise of his book in its opening words. With the use of the name “Christ” (the Greek word for the Hebrew word “Messiah”) Mark immediately draws attention to Jesus of Nazareth being the Promised One of the Nation of Israel. He wants all to know, especially Jewish people, that the Messiah they have been looking for has already come. Mark also claims that this Messiah is the Son of God. A debatable matter amongst Jewish and Gentile people. Yet, the claim is so bold, that it is worthy of investigation.

1:2-3 Just as it has been written in Isaiah the prophet, Behold I will send my messenger before you who will prepare your way, a voice of one calling out in the wilderness, ‘Prepare the way of the Lord, make straight paths for him.’

Immediately, Mark lays claim to the Hebrew Scriptures as the supreme authority to backup his statement in verse 1. Isaiah was written approximately between 740-701 B.C., long before the arrival of the Mark’s good news/gospel that Jesus Christ is God’s Son, the Promised One to the Jewish people and to the world. Isaiah chapters 1-39 are about Israel’s rebellious, sinful ways (Isaiah 1-5), and then about the LORD’s coming judgment upon the Jewish people because of their chosen rebellion. Isaiah 39 reviews the coming judgment through the hand of the Babylonians, who will even ransack and burn the Lord’s temple and take his people into captivity. We know that Daniel 9 reviews the 70 year captivity. The context of Isaiah 40-66 is to comfort the LORD’s people (the Hebrews), that the times of judgment will not last, and that there will be the time to prepare the way of the LORD and make straight paths for him for his Messiah will redeem and restore his people and any who claim his name as Lord. It is with this comforting news that Mark begins the good news of Jesus Christ/Messiah God’s Son.

In both Isaiah and Mark, the forerunner of the Messiah is key. A forerunner prepares, go before. Thus, the very nature of a forerunner makes the message about what follows even more imperative and worthy of listening to with a change in action for the listeners.

1:4 Now there was John the Baptizer in the dessert and he was preaching a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins.

John the Baptizer performed his mission not in the cities and villages but in the dessert. Why? For none, there are less distractions in the dessert. Someone proclaiming a message and baptizing people would stand out more than in a city, where he could easily be ignored. Also, he was baptizing people in the Jordan river, where many go for water, bathing and washing of clothes, as well as to be refreshed from the arid, hot climate of Israel. Thus, word would easily spread about John and his message.

The historical context of Mark at this point is that the Hebrew people have been under the thumb of the Roman Empire for many years. They were heavily taxed, oppressed and helpless against a ruthless government that worshiped Caesar. Thus, the Romans were detestable to most Hebrews, who worshiped the LORD God of Israel through sacrifices at the Second Temple in Jerusalem.

What kind of message is John the Baptizer preaching? It isn’t one of sacrifices per the Law of Moses. It’s a new message, a different message of repentance for forgiveness of sins. A message that would smooth out the valleys and bring low the mountains of life. The roughness of life shall become level, its rugged smooth. Thus, his message stood out all the more. This would cause the message to spread quickly.

Self-Reflection

Where/what is our dessert? Where/what is the refreshment of our souls? To whom are we listening? One proclaiming the way of the Lord to make straight paths for him? Or, are we listening to the many voices, the confusion and the hustle and bustle of a hectic life, filled with many voices? How is our present state of life refreshing our souls and bringing us closer to who the Gospel of Mark claims Jesus of Nazareth to be? Name three ways in which you can change your life to listen better to John the Baptizer’s message, as well as the message of the Gospel of Mark thus far?

1.

2.

3.

1:5 and all the Judean region and all those living in Jerusalem were going out to him and were being baptized by him in the Jordan River, confessing their sins.

The going out to John was an intentional one. One of purpose. Under the heavy hand of Rome (like the Hebrews of Isaiah’s and Daniel’s day being judged by God through the Assyrians and the Babylonians) there is now the time of preparing for the way of the LORD and making straight paths, leveling out life’s hardships and difficulties. This message is not carried out by throwing off the hardships and difficulties but by turning to the One who forgives sin and then makes our way smoother in the midst of the hardships and difficulties. Although the people of that time were used to traveling in the dry, arid climate of the Judean wilderness, it was still an arduous journey. The trip from Jerusalem to the Jordan River crosses a dessert area littered literally with millions upon millions of rocks of various sizes, deep crevices, low mountains, valleys, dust, heat (depending on the time of year), little to no water. The people of the region and of Jerusalem are so thirsty for a making straight of their oppressed and rugged lives, that they welcomingly travel the arid countryside by foot, donkey and/or camel to listen to this new message from a loner man, who lives in the dessert.

1:6 and John wore clothes made of camels hair, with a leather belt around his waist, and ate locusts and wild honey.

To the Hebrew, this is a clear reference to the highly-esteemed prophet, Elijah. Mark is saying that one like Elijah, the mighty prophet and miracle worker of the Hebrews, is now here and his message is even greater, as the new Elijah, John the Baptizer. That Elijah is so pertinent to the Jewish culture of this time, Elijah himself is one of two people who appear and talks with Jesus on the Mount of Tranfiguration (Mark 9:2-13). Jewish people understand that Elijah must come before the Messiah arrives. Mark claims that John is that man.

Self-Reflection

Would we truly travel across a dessert area on foot or animal, let alone a vehicle of today, to listen to the message of a loner, who lives in the dessert? His hair has to be dirty and matted. His beard, eyebrows, ear hair long, possibly filled with dirt and grime. He stinks. His teeth are dirty and possibly rotting. Not only all of this, he dresses like a crazy man, wearing camel haired clothes (brown and tan against his sun darkened skin). He eats giant grass hoppers and unprocessed honey. What kind of truth does he have to offer? Would we be willing to accept him as greater than one of the greatest of God’s prophets ever? What would we do personally to change our lives in light of his message?

1:7-8 and he preached saying, There is one more powerful than I, after me, of whom I am not worthy to loosen the straps of the sandals of his feet. I baptize you with water, but he himself will baptize you with the holy spirit.

Baptism is a common concept to Jewish people. The Greek word “to baptize” is equal to the Hebrew ritual word used for the “ritual cleansing bath” a worshiper would take to spiritual cleanse oneself before offering sacrifices to the LORD at the Temple in Jerusalem. At the southern end of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem there is an archaeological find of what are known to be “mikvahs”. Mikvahs are the ritual cleansing areas one would use before entering the Temple Mount to offer sacrifices to the LORD at the Temple. Mikvahs have steps that descend some 4-5 feet into a small area that was filled with water to immerse one’s self for the cleansing ritual. The Mikvah area at the southern end of the Temple Mount is most likely where over 3000 people were baptized by Peter and other apostles with him when he preached on the Day of Pentecost, post-resurrection of Jesus (Acts of the Apostles 3).

The message here is clear, spiritually cleanse ourselves before the LORD by being baptized to receive forgiveness of our sins. In other words, instead of taking the symbolical ritual mkvah bath to present yourselves to the LORD at the Temple with your sacrifice(s) for him, be ritually/spiritually cleansed by offering yourself as the sacrifice to the LORD for the forgiveness of your sins. Clearly, a new message, the good news, the gospel of Jesus Christ/Messiah Son of God has come to his people and to the world.

This new message brings a new gift, the holy spirit. In the Hebrew Scriptures of Psalm 51, King David (the one to whom the LORD promised an eternal kingdom) cries out in deep grief stricken repentance that the LORD will not remove his spirit from him. David was the man after God’s own heart, as the Hebrew Scriptures describe him. Yet, David committed adultery with another man’s wife (one of his soldiers), deceived others about this by calling her husband back from the war front to sleep with his wife, plotted to have him killed in battle (murder), and then lied about it for a year. The LORD sent his prophet Nathan to confront David for all of this. This is the context of Psalm 51. It is no wonder that David cries out begging the LORD not to remove his spirit from him. The LORD mercifully forgives David and grants his request. David knew that without the spirit of the LORD, he could not become the man and king that the LORD wanted him to be. John proclaims that The One who is greater than I, he himself will baptize you with the holy spirit. The religious leaders of Israel did not teach this teaching. They emphasized a distorted message of the LORD, because of which people from all over the Judean wilderness and Jerusalem itself, flocked to a loner, hairy, stinky, weird dressed, grasshopper eating man, who proclaimed a new message from the LORD, be baptized for the forgiveness of your sins, for the Promised Messiah is coming soon.

Self-Reflection

How committed are we to obeying the call of the LORD upon our lives to live in a deepening relationship with him? What are we willing to give up in the comfort and convenience of our lives to be a lone soul in the dessert of life crying to any who will listen…There is a better way, a smoother way. There is a life worth living, that is not filled with the clutter of many voices and guilt ridden teachings and philosophies of self-dependence. There is a better life, because the only One who is worthy has come and invites us to live in the wonder and joy of his forgiveness and guidance to the deeper life with the Father. What will we do to live in, to embrace that life?

List three ways in which the Lord is speaking to you about such change:

1.

2.

3.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Can Good Exegesis Make Bad Theology?

By Author Eli Kittim

——-

The Canonical Context

This principle suggests that we should read the Books of the Bible not as distinct, individual compositions but rather as parts of a larger *canonical context*, that is, as part of the “canon” of Scripture. In other words, instead of evaluating each book separately in terms of its particular historical, literary, and editorial development, this principle focuses instead on its final canonical format that was legitimized by the various communities of faith. The idea is that since the redacted version or “final cut,” as it were, is considered “authoritative” by the different communities of faith, then this format should hold precedence over all previous versions or drafts.

Moreover, this concept holds that despite the fact that the Biblical Books were written by a number of different authors, at different times, in different places, using different languages, nevertheless the “canonical context” emphasizes the need to read these Books in dialogue with one another, as if they are part of a larger whole. So, the hermeneutical focus is not on the historical but rather on the canonical context. The hermeneutical guidelines of the canon therefore suggest that we might gain a better understanding of the larger message of Scripture by reading these Books as if they were interrelated with all the others, rather than as separate, diverse, and distinct sources. The premise is that the use of this type of context leads to sound Biblical theology.

——-

Theology

Theology is primarily concerned with the synthesis of the diverse voices within Scripture in order to grasp the overarching message of the complete Biblical revelation. It deals with Biblical epistemology and belief, either through systematic analysis and development of passages (systematic theology) or through the running themes of the entire Bible (Biblical theology). It addresses eternity and the transcendent, metaphysical or supernatural world. And it balances individual Scriptural interpretations by placing them within a larger theoretical framework. The premise is that there is a broader theological context in which each and every detailed exegesis coalesces to form a coherent whole! It’s as if the Bible is a single Book that contains a complete and wide-ranging revelation! It is under the auspices of theology, then, that the canonical context comes into play.

——-

Exegesis

The critical interpretation of Scriptural texts is known as “exegesis.” Its task is to use various methods of interpretation so as to arrive at a definitive explanation of Scripture! Exegesis provides the temporal, linguistic, grammatical, and syntactic context, analysis, and meaning of a text. It furnishes us with a critical understanding of the authorial intent, but only in relation to the specific and limited context of the particular text in question. It is the task of theology to further assess it in terms of its relation and compatibility to the overall Biblical revelation! One of the things that exegesis tries to establish is the composition’s historical setting or context, also known as “historical criticism.” This approach inquires about the author and his audience, the occasion and dating of the composition, the unique terms and concepts therein, the meaning of the overall message, and, last but not least, the *style* in which the message is written, otherwise known as the “genre.” While the author’s other writings on the topic are pivotal to understanding what he means, nothing is more important than the *genre* or the form in which his writing is presented.

——-

The Analogy of Scripture

One of the most important hermeneutical principles of exegesis is called “the analogy of Scripture” (Lat. ‘analogia Scripturae’). In short, it means that Scripture should interpret Scripture. This principle requires that the implicit must be explained by the explicit. In other words, the exegesis of unclear or ambiguous parts of Scripture must be explained by clear and didactic ones that address the exact same topic. That means that one Biblical Book could very well explain another. For example, the New Testament (NT) Book of Ephesians 1.9-10 seems to demystify Galatians 4.4. This principle is based on the “revealed” inspiration (Gk. θεόπνευστος) of Scripture:

All scripture is inspired by God and is useful

for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and

for training in righteousness (2 Tim. 3.16

NRSV).

As for those scholars who refuse to take the NT’s alleged “pseudepigrapha” seriously because of their *apparent* false attribution, let me remind them that the most renowned textual scholars of the 20th century, Bruce M. Metzger and Bart D. Ehrman, acknowledged that even alleged “forged” works could still be “inspired!” It’s important to realize that just because these works may be written by unknown authors who may have attempted to gain a readership by tacking on the name of famous Biblical characters doesn’t mean that the subject-matter is equally false. The addition of amanuenses (secretaries) further complicates the issue.

So, returning to our subject, the analogy of Scripture allows the Bible to define its own terms, symbols, and phrases. It is via the analogy of Scripture, which defines the many and varied parts, that the broader canonical context is established, namely, the principle that the various Biblical Books form a coherent whole from which a larger theological system can emerge.

And, of course, interdisciplinary studies——such as archaeology, anthropology, psychology, sociology, epistemology, and philosophy——contribute to both systematic and Biblical theology by presenting their particular findings, concepts, and theoretical ideas.

——-

Testing the Legitimacy of these Principles

In explaining how these principles work in tandem, I’d like to put my personal and unique theology to the test. I have raised the following question: “What if the crucifixion of Christ is a future event?” The immediate reaction of Christian apologetics or heresiology would be to revert to “dogmatic theology” (i.e., the dogmas or articles of faith) and the scholarly consensus, which state that Jesus of Nazareth was crucified under Pontius Pilate during the reign of Tiberius. Really? Let’s consider some historical facts. There are no eyewitnesses! And there are no first-hand accounts! Although the following references were once thought to be multiple attestations or proofs of Jesus’ existence, nevertheless both the Tacitus and Josephus accounts are now considered to be either complete or partial forgeries, and therefore do not shed any light on Jesus’ historicity. One of the staunch proponents of the historical Jesus position is the textual scholar Bart Ehrman, who, surprisingly, said this on his blog:

. . . Paul says almost *NOTHING* about the

events of Jesus’ lifetime. That seems weird

to people, but just read all of his letters.,

Paul never mentions Jesus healing anyone,

casting out a demon, doing any other

miracle, arguing with Pharisees or other

leaders, teaching the multitudes, even

speaking a parable, being baptized, being

transfigured, going to Jerusalem, being

arrested, put on trial, found guilty of

blasphemy, appearing before Pontius Pilate

on charges of calling himself the King of the

Jews, being flogged, etc. etc. etc. It’s a

very, very long list of what he doesn’t tell us

about.

Therefore, there appears to be a literary discrepancy regarding the historicity of Jesus in the canonical context between the gospels and the epistles. And, as I will show in due time, there are many, many passages in the epistles that seem to contradict dogmatic theology’s belief in the historiographical nature of the gospels. So, if they want to have a sound theology, exegetes should give equal attention to the epistles. Why?

First, the epistles precede the gospels by several decades. In fact, they comprise the earliest recorded writings of the NT that circulated among the Christian churches (cf. Col. 4.16).

Second, unlike the gospels——which are essentially *theological* narratives that are largely borrowed from the Old Testament (OT)——the epistles are *expositional* writings that offer real, didactic and practical solutions and discuss spiritual principles and applications within an actual, historical, or eschatological context.

Third, according to Biblical scholarship, the gospels are not historiographical accounts or biographies, even though historical places and figures are sometimes mentioned. That is to say, the gospels are not giving us history proper. For example, the feeding of the 5,000 is a narrative that is borrowed from 2 Kings 4.40-44. The parallels and verbal agreements are virtually identical. And this is a typical example of the rest of the narratives. For instance, when Jesus speaks of the damned and says that “their worm never dies, and the fire is never quenched” (Mark 9.48), few people know that this saying is actually derived from Isaiah 66.24. In other words, the gospels demonstrate a literary dependence on the OT that is called, “intertextuality.”

Fourth, the gospels are like watching a Broadway play. They are full of plots, subplots, theatrical devices (e.g. Aristotelian rhetoric; Homeric parallels), literary embellishments, dialogues, characters, and the like. Conversely, the epistles have none of these elements. They are straightforward and matter of fact. That’s why Biblical interpreters are expected to interpret the implicit by the explicit and the narrative by the didactic. In practical terms, the NT epistles——which are the more explicit and didactic portions of Scripture——must clarify the implicit meaning of the gospel literature. As you will see, the epistles are the primary keys to unlocking the actual timeline of Christ’s *one-and-only* visitation!

Fifth, whereas the gospels’ literary genre is mainly •theological•——that is to say, “pseudo-historical”——the genre of the epistolary literature of the NT is chiefly •expositional.• So, the question arises, which of the two genres is giving us the real deal: is it the “theological narrative” or the “expository writing”?

In order to answer this question, we first need to consider some of the differences in both genres. For example, although equally “inspired,” the gospels include certain narratives that are unanimously rejected as “unhistorical” by both Biblical scholars and historians alike. Stories like the slaughter of the innocents, the Magi, the Star of Bethlehem, and so on, are not considered to be historical. By contrast, the epistles never once mention the aforesaid stories, nor is there any mention of the Nativity, the virgin birth, the flight to Egypt, and the like. Why? Because the Epistles are NOT “theological.” They’re expository writings whose intention is to give us the “facts” as they really are!

Bottom line, the epistles give us a far more accurate picture of Jesus’ *visitation* than the gospels.

In conclusion, it appears that the gospels conceal Jesus far more effectively than they reveal him.

——-

Proof-text and Coherence Fallacies

The “proof-text fallacy” comprises the idea of putting together a number of out-of-context passages in order to validate a particular theological point that’s often disparagingly called “a private interpretation.” But, for argument’s sake, let’s turn these principles on their head. Classical Christianity typically determines heresy by assessing the latter’s overall view. If it doesn’t fit within the existing theological schema it is said to be heretical. Thus, dogmatic theology sets the theological standard against which all other theories are measured. They would argue that good exegesis doesn’t necessarily guarantee good theology, and can lead to a “coherence fallacy.” In other words, even if the exegesis of a string of proof-texts is accurate, the conclusion may not be compatible with the overall existing theology. This would be equivalent to a coherence fallacy, that is to say, the illusion of Biblical coherence.

By the same token, I can argue that traditional, historical-Jesus exegesis of certain proof-texts might be accurate but it may not fit the theology of an eschatological Christ, as we find in the epistles (e.g., Heb. 9.26b; 1 Pet. 1.20; Rev. 12.5). That would equally constitute a coherence fallacy. So, these guidelines tend to discourage independent proof-texting apart from a systematic coherency of Scripture. But what if the supposed canonical context is wrong? What if the underlying theological assumption is off? What then? So, the $64,000 question is, who can accurately determine the big picture? And who gets to decide?

For example, I think that we have confused Biblical literature with history, and turned prophecy into biography. In my view, the theological purpose of the gospels is to provide a fitting introduction to the messianic story *beforehand* so that it can be passed down from generation to generation until the time of its fulfillment. It is as though NT history is *written in advance* (cf. מַגִּ֤יד מֵֽרֵאשִׁית֙ אַחֲרִ֔ית [declaring the end from the beginning], Isa. 46.9-10; προεπηγγείλατο [promised beforehand], Rom. 1.2; προγνώσει [foreknowledge], Acts 2.22-23; προκεχειροτονημένοις [to appoint beforehand], Acts 10.40-41; ερχόμενα [things to come], Jn 16.13)!

So, if we exchange the theology of the gospels for that of the epistles we’ll find a completely different theology altogether, one in which the coherence of Scripture revolves around the *end-times*! For example, in 2 Pet. 1.16–21, all the explanations in vv. 16-18 are referring to the future. That’s why verse 19 concludes: “So we have the prophetic message more fully confirmed” (cf. 1 Pet. 1.10-11; 1 Jn 2.28).

In response, Dogmatic Theology would probably say that such a conclusion is at odds with the canonical context and that it seems to be based on autonomous proof-texting that is obviously out of touch with the broader theological teaching of Scripture. Really? So the so-called “teaching” of Scripture that Jesus died in Antiquity is a nonnegotiable, foregone conclusion? What if the basis upon which this gospel teaching rests is itself a proof-text fallacy that is out of touch with the teaching of the *epistles*? For example, there are numerous passages in the epistles that place the timeline of Jesus’ life (i.e., his birth, death, and resurrection) in *eschatological* categories (e.g., 2 Thess. 2.1-3; Heb. 1.1-2; 9.26b; 1 Pet. 1.10-11, 20; Rev. 12.5; 19.10d; 22.7). The epistolary authors deviate from the gospel writers in their understanding of the overall importance of •eschatology• in the chronology of Jesus. For them, Scripture comprises revelations and “prophetic writings” (see Rom. 16.25-26; 2 Pet. 1.19-21; Rev. 22.18-19). Therefore, according to the *epistolary literature*, Jesus is not a historical but rather an “eschatological” figure! Given that the NT epistles are part of the Biblical *canon,* their overall message holds equal value with that of the NT gospels, since they, too, are an integral part of the canonical context! To that extent, even the gospels concede that the Son of Man has not yet been revealed (see Lk. 17.30; cf. 1 Cor. 1.7; 1 Pet. 1.7)!

What is more, if the canonical context demands that we coalesce the different Biblical texts as if we’re reading a single Book, then the overall “prophetic” message of Revelation must certainly play an important role therein. The Book of Revelation places not only the timeline (12.5) but also the testimony to Jesus (19.10b) in “prophetic” categories:

I warn everyone who hears the words of the

prophecy of this book: if anyone adds to

them, God will add to that person the

plagues described in this book; if anyone

takes away from the words of the book of

this prophecy, God will take away that

person’s share in the tree of life and in the

holy city, which are described in this book

(Rev. 22.18-19 NRSV).

Incidentally, the Book of Revelation is considered to be an epistle. Thus, it represents, confirms, and validates the overarching *prophetic theme* or eschatological “theology” of the epistolary literature. That is not to say that the •theology• of the epistles stands alone and apart from that of the OT canon. Far from it! Even the *theology* of the OT confirms the earthy, end-time Messiah of the epistles (cf. Job 19.25; Isa. 2.19; Dan. 12.1-2; Zeph. 1.7-9, 15-18; Zech. 12.9-10)! As a matter of fact, mine is the *only* view that appropriately combines the end-time messianic expectations of the Jews with Christian Scripture!

Does this sound like a proof-text or coherence fallacy? If it does, it’s because you’re evaluating it from the theology of the gospels. If, on the other hand, you assess it using the theology of the epistles, it will seem to be in-context or in-sync with it. So, the theological focus and coherency of Scripture will change depending on which angle you view it from.

——-

Visions of the Resurrection

There are quite a few scholars that view the so-called resurrection of Christ not as a historical phenomenon but rather as a visionary experience. And this seems to be the theological message of the NT as well (cf. 2 Tim. 2.17-18; 2 Thess. 2.1-3). For example, Lk. 24.23 explicitly states that the women “had indeed seen a vision.” Lk. 24.31 reads: “he [Jesus] vanished from their sight.” And Lk. 24.37 admits they “thought that they were seeing a ghost.” Here are some of the statements that scholars have made about the resurrection, which do not necessarily disqualify them as believers:

The resurrection itself is not an event of

past history. All that historical criticism can

establish is that the first disciples came to

believe the resurrection (Rudolph

Bultmann, ‘The New Testament and

Mythology,’ in Kerygma and Myth: A

Theological Debate, ed. Hans Werner

Bartsch, trans. Reginald H. Fuller [London:

S.P.C.K, 1953-62], 38, 42).

When the evangelists spoke about the

resurrection of Jesus, they told stories

about apparitions or visions (John Dominic

Crossan, ‘A Long Way from Tipperary: A

Memoir’ [San Francisco:

HarperSanFransisco, 2000], 164-165).

At the heart of the Christian religion lies a

vision described in Greek by Paul as

ophehe—-“he was seen.” And Paul himself,

who claims to have witnessed an

appearance asserted repeatedly “I have

seen the Lord.” So Paul is the main source

of the thesis that a vision is the origin of the

belief in resurrection ... (Gerd Lüdemann,

‘The Resurrection of Jesus: History,

Experience, Theology.’ Translated by John

Bowden. [London: SCM, 1994], 97,

100).

It is undisputable that some of the followers

of Jesus came to think that he had been

raised from the dead, and that something

had to have happened to make them think

so. Our earliest records are consistent on

this point, and I think they provide us with

the historically reliable information in one

key aspect: the disciples’ belief in the

resurrection was based on visionary

experiences. I should stress it was visions,

and nothing else, that led to the first

disciples to believe in the resurrection (Bart

D. Ehrman, ‘How Jesus Became God: The

Exaltation of a Jewish Preacher from

Galilee’ [New York: Harper One, 2014],

183-184).

Ehrman sides with the *visionary language* that Luke, Bultmann, Crossan, and Lüdemann use. In the words of NT textual critic Kurt Aland:

It almost then appears as if Jesus were a

mere PHANTOM . . .

——-

Exegetical Application

I deliberately stay away from theology when I exegete Scripture precisely because it will taint the evidence with presuppositions, assumptions, and speculations that are not in the text. Thus, instead of focusing on the authorial intent hermeneutic, it will inevitably superimpose out-of-context meanings and create an eisegesis. All this, of course, is courtesy of confirmation bias.

So, I think one of the reasons why we’ve done so poorly in understanding, for example, the story of Jesus is because we have mixed-up exegesis with theology. When theology drives the exegesis, then the exegesis becomes blind and erroneous.

My method of exegesis is very simple. I see EXACTLY what the text *says,* EXACTLY *how* it says it. I don’t add or subtract anything, and I don’t speculate, guess, or theorize based on existing philosophies or theologies. The minute we go outside *the analogy of scripture,* that’s when we start to speculate. And that’s how we err. In short, let the Scriptures tell you what it means. Thus, the best interpretation is no interpretation at all!

——-

Conclusion

To find the truth, we must consider all the evidence objectively. Evangelicals, for instance, would be biased if they didn’t consider the academic standpoint even if, at times, it seems to be guided by liberal theology. In this way, they will be in a better position to consider objectively all the possibilities and probabilities regarding the correct interpretation of Scripture. That’s because the truth usually touches all points of view . . .

One of the exegetical stumbling blocks is our inability to view the gospels as “inspired metaphors.” Given their literary dependence on the OT, it appears as if the gospels themselves are “inspired parables.”

So, if the epistolary literature, which is both expositional and explicit, seems to contradict these so-called “theological parables,” then it becomes quite obvious that the “theology” of the gospels fails to meet scholarly and academic parameters. And, therefore, the epistolary literature must be given more serious attention and consideration!

Our exegetical shortcomings often stem from forced or anachronistic interpretations that are based on *theological speculation* and conjecture rather than on detailed exegesis. Even the Biblical translations themselves are not immune to the interpretative process, whether they be of dynamic or formal equivalence.

That’s why I have developed an exegetical system and have demonstrated the effectiveness of its approach to the study of the Biblical Christ. Accordingly, I argue that the epistles are the primary *keys* to unlocking the future timeline of Christ’s ***ONLY*** visitation! Hence, I leave you with one final rhetorical question:

What if the crucifixion of Christ is a future

event?

#canonical context#biblical theology#systematic theology#exegesis#authorial intent#biblical criticism#biblical interpretation#bible prophecy#eli kittim#the little book of revelation#future eschatology#end times#historical criticism#the analogy of scripture#pseudepigrapha#Bruce Metzger#bart ehrman#christian apologetics#heresiology#dogmatic theology#Tacitus#Josephus#canonical gospels#epistles#proof-text fallacy#coherence fallacy#Rudolf Bultmann#John Dominic Crossan#Gerd Lüdemann#Kurt Aland

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

What do actual Bible scholars say about the Jehovah’s Witnesses’ “New World Translation”?

Dr. Bruce M. Metzger, professor of New Testament at Princeton University, calls the NWT "a frightful mistranslation,... Erroneous... pernicious... reprehensible... If the Jehovah's Witnesses take this translation seriously, they are polytheists."

Dr. William Barclay, a leading Greek scholar, said "it is abundantly clear that a sect which can translate the New Testament like that is intellectually dishonest."

British scholar H.H. Rowley stated, "From beginning to end this volume is a shining example of how the Bible should not be translated....Well, as a backdrop, I was disturbed because they (Watchtower) had misquoted me in support of their translation." (These words were excerpted from the tape, "Martin and Julius Mantey on The New World Translation", Mantey is quoted on pages 1158-1159 of the Kingdom interlinear Translation)

Dr. Julius Mantey, author of A Manual Grammar of the Greek New Testament, calls the NWT "a shocking mistranslation... Obsolete and incorrect... It is neither scholarly nor reasonable to translate John 1:1 'The Word was a god... I have never read any New Testament so badly translated as The Kingdom Interlinear Translation of The Greek Scriptures... it is a distortion of the New Testament. The translators used what J.B. Rotherham had translated in 1893, in modern speech, and changed the readings in scores of passages to state what Jehovah's Witnesses believe and teach. That is a distortion not a translation." (Julius Mantey, Depth Exploration in The New Testament (N.Y.: Vantage Pres, 1980), pp.136-137) the translators of the NWT are "diabolical deceivers." (Julius Mantey in discussion with Walter Martin)

On a side-note: Dr. Mantey was also misquoted by the Watchtower. The letter he sent (in which he calls the NWT a perversion of God’s Word) can be found here

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Are There So Many Bible Translations?

Many skeptics contend that given the myriad of Bible translations we have today, how can we be confident of what the original said or what the original meaning was? Let’s take a closer look at the trustworthiness of the various English translations of the Bible.

Firstly, translations are essential, because language changes. Words and their meanings evolve over time. Translations are necessary to ensure each generation has an accurate understanding of the Bible.

Secondly, the Bible was originally written in three different languages: Hebrew, a little bit of Aramaic, and Greek. Unless you’re fluent in all three of these ancient languages you’re going to need a modern translation to read the Bible for yourself.

There are essentially two approaches to translating the Bible into English. It’s helpful to visualize them forming two ends of a spectrum. At one end you have word for word translations. They’ll take a word in Hebrew or a word in Greek and they’ll match it with the English equivalent, where possible. These translations are word for word accurate but can become very technical, difficult to read and understand. At the other end of the spectrum are thought for thought translations. They won’t take the identical words but they’ll attempt to translate and communicate the underlying message or thought. Often these translations are easier to read and understand but the question is, are they accurately capturing and communicating the underlying thought. Both approaches aim to get as close to the original language as possible while faithfully conveying the meaning of the text for the reader.

It’s important to understand that the biblical languages are far more nuanced, so sometimes there are meanings that aren’t perfectly caught by English. It is therefore necessary and a great advantage to have a number of translations that employ one of these two approaches, or a mixture of both to more accurately and completely capture the meanings of the original Hebrew or Greek.

Here are some examples of various English translations and the approach they follow:

Formal equivalence (word for word): King James Version (KJV), New American Standard Bible (NASB), and Young’s Literal Translation (YLT).

Dynamic equivalence (thought for thought): New International Version (NIV), and Contemporary English Version (CEV).

Mixture of both: English Standard Version (ESV), New King James Version (NKJV), New Century Version (NCV), New Living Translation (NLT), and Christian Standard Bible (CSB).

Paraphrase: New Living Bible (NLB), and the Message.

When studying the Bible it’s helpful to read the same section in a number of different translations, in order to build a more complete, accurate, nuanced, and robust understanding of what the Bible says.

Given the necessity and benefit of many Bible translations, it’s clear that rather than undermine the accuracy and reliability of the Bible, the various translations work together to provide us with a clearer and more complete understanding of God’s Word.

_____

If you enjoyed this article, click here to check out the accompanying ebooklet

Why Are There So Many Bible Translations?

_____

Further reading recommendations

‘The Bible in Translation' by Bruce M Metzger

'Understanding Bible Translation' by William D Barrick

'The Challenge of Bible Translation' by Glen Scorgie, Mark Strauss, & Steven Voth

'The Complete Guide to Bible Translation' by Ron Rhodes

'Bible Translations Comparison (Booklet)' by Rose Publishing

0 notes

Text

Book Review: Suffering & Glory by Lexham Press

In Suffering & Glory, Lexham Press presents the best of Christianity Today’s meditations for Holy Week and Easter. With contributions from Esau McCaulley, Tish Harrison Warren, Nancy Guthrie, Jeremy Treat, and more -- this collection has a variety of voices and personal perspectives. Each writer has their own characteristic style, but the book flows well as it follows the Passion narrative.

The 17 chapters are short, and the book is less than 200 pages. Each chapter corresponds to a day in the Biblical story, starting with Palm Sunday and ending with Pentecost. They are meant to be read devotionally, but I found them hard to resist reading them through in one sitting.

Learn to Hope

There were several standout selections. Philip Yancey has the honor of writing for Easter Sunday, and he tells a tragic childhood story of how he learned that death is irreversible. But in the grief, he learned to hope, and Yancey turned my heart to the resurrected Christ.

J. I. Packer takes us on the road to Emmaus, showing how Jesus was the perfect counselor, explainer of Scripture, and ultimately revealed his presence. It helped me imagine what it would be like to have Jesus appear after his death, speaking amidst my pain and confusion.

Christ is Superior and Sovereign

The four Gospels are each given their due by Eugene Peterson as he explains how each is unique and ultimately provides a true and clearer picture of Christ. I reflected on how each of us has a story to tell of Christ’s saving work on the cross as well as in our lives.

By the time the book got to Christ’s ascension, I wasn’t ready to put it down. I wasn’t ready for Jesus to leave us. Bruce M. Metzger shows how Jesus entered a higher sphere of spiritual existence, and this is significant to show his superiority and sovereignty. I felt comforted knowing that Christ sends us the Spirit.

Exclaim the Good News

The book ends with John Stott showing us in Acts 2 what a Spirit-filled church should look like. A Spirit-filled church studies the Scriptures, shares a common fellowship, and worships. Furthermore, the worship is both formal and informal, reverent and rejoicing. Finally, a Spirit-filled church evangelizes.

As churches begin to reopen and as the world begins to reopen, I actually find myself wanting to spend more time alone with Christ. While that is certainly a possibility, I am also energized to exclaim the Good News. Christ is risen. Christ is King. And Christ is returning -- coming back in terrible, uncontainable glory.

I received a media copy of Suffering & Glory and this is my honest review. Find more of my book reviews and follow Dive In, Dig Deep on Instagram - my account dedicated to Bibles and books to see the beauty of the Bible and the role of reading in the Christian life. To read all of my book reviews and to receive all of the free eBooks I find on the web, subscribe to my free newsletter.

0 notes

Text

One must pay attention not only to what is said, but also by whom it is said, to whom it is said, at what time, under what circumstances, what precedes, and what follows. There is the thoughtless habit of quoting all parts of the Bible as of equal value, whether they are the words of the Lord or the words of Bildad the Shuhite and Zophar the Naamathite in the book of Job, who are afterwards represented as condemned and contradicted by God. In other words, not everything contained in the Bible is affirmed by the Bible.

The New Oxford Annotated Bible: New Revised Standard Version ed. Bruce M. Metzger and Roland E. Murphy

#quote#the bible#nrsv#the new oxford annotated bible#bruce m. metzger#roland e. murphy#christianity#dark academia#light academia#religion#god#theology#religious studies#literature

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

A,B,F,G,H,I,J,K,M,X,Y,Z!

A: What’s the first book you see with a red spine? In my backpack currently there is A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament - 2nd Edition edited by Bruce M. Metzger. It is red.

B: What’s your most expensive book? What immediately jumps to mind is my The Oxford Handbook of Islamic Theology edited by Sabine Schmidtke. Though way cheaper now, it was over $100 or so when I bought it. Upon further thinking, I realize my Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament edited by Koehler and Baumgartner is just about three times more expensive.

F: What’s your regular order at Starbucks? Grande blonde roast.

G: What’s your favorite reading spot? Currently a book and wine bar in my town.

H: What’s the longest book you’ve ever read? I suppose the easy answer is the Bible is the longest book I’ve ever read. (now about five times in my lifetime). Other relatively long books I’ve read are The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco or The Once and Future King by T. H. White. Maybe The Bondage of the Will by Martin Luther, or his Against Latomus. I remember Origen’s Commentary on the Gospel of Matthew to be pretty long. Irenaeus Against the Heresies was five volumes.

I: Do you have a favorite poet? This is a hard question for me because I don’t read nearly as much poetry as I would like. In college I took a class on English Literature that included poets like William Blake. But, it’s been so long I don’t recall what I particularly enjoyed and by whom. I seem to have been impacted by a poet who wrote something about an albatross, but I don’t remember who or what it was. If musical lyrics count as poetry, I have liked the likes of dodie Clark or Sufjan Stevens.

J: Favorite woman writer? I have liked a lot of the theological work of Kathryn Kleinhans. Barbara Rossing on the topics Revelation, eschatology, and apocalyptic is quite illuminating. For non-theological books, I’ve liked Suzanne Collins, Tara Westover. I was captivated by Heather Morris.

K: Favorite male writer? Clearly I have an affinity for Martin Luther. But also Philip Melanchthon and Johannes Bugenhagen, together the triumvirate of the Reformation. Gerhard Forde, Steven Paulson, and Adam Morton are contemporary favorites. As well as my beloved professor Kurt Hendel. For non-theological it is harder. Perhaps you can count Umberto Eco.

M: Favorite classic? Hmmm. Much Ado About Nothing was something I remember reading in high school that I enjoyed. I’m not sure about other classics.

X: What book has your favorite cover art? Generally I toss away the dust jackets on books. I like the cover art on Word of Life: Introducing Lutheran Hermeneutics by Timothy J. Wengert.

Y: Do you have a favorite quote? Yes. “And this is the reason why our theology is certain: it snatches us away from ourselves and places us outside ourselves, so that we do not depend on our own strength, conscience, experience, person, or works but depend on that which is outside ourselves, that is, on the promise and truth of God, which cannot deceive.” ~Martin Luther

Z: If you wrote a book, what would it be about? I could possibly write a book centering ‘justification by faith’ for any kind of affirmative LGBT theology, which currently there isn’t a book that does this. I could write a book of confirmation curriculum. I have pondered writing a theological poetry book. I wouldn’t mind writing a gay romance book.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Refined Greek Texts

New Testament textual criticism goes back to Origen (185-254), in the third century of our common era. The historical roots of textual scholarship actually go back to the 3rd-century B.C.E. in the Library of Alexandria. We are going to the 18th-19th centuries for the purposes of this chapter.

From 1550, the New Testament Greek text was in bondage to the popularity of the Textus Receptus, as though it were inspired itself, and no textual scholar would dare make changes regardless the evidence found in older manuscripts that are more accurate that became known. The best they would offer was to publish these new finding in their introductions, margins, and footnotes of their editions. Just prior to Griesbach in 1734, Johann Albrecht Bengel (1687-1752) apologized for having once again to print the Textus Receptus (Received Text) “because he could not publish a text of his own. Neither the publisher nor the public would have stood for it.” (Robertson 1925, 25)

It was Griesbach himself, who became the first textual scholar to place his finding within his version of the Greek text. However, even Griesbach was not the first to break away completely from the influential Textus Receptus was Karl Lachmann (1793-1851), Professor of Classical and German Philology at Berlin. In 1831, he published at Berlin his edition of the Greek text overthrowing the Textus Receptus. Ezra Abbot says of Lachmann, “He was the first to found a text wholly on ancient evidence; and his editions, to which his eminent reputation as a critic gave wide currency, especially in Germany, did much toward breaking down the superstitious reverence for the textus receptus.” (Schaff, Companion to the Greek Testament, 1883, 256-7)

Johann Jakob Griesbach [1745-1812]

Griesbach obtained his master’s degree at the age of twenty-three. He was educated at Frankfurt, and at the universities of Tubingen, Leipzig, and Halle. Griesbach became one of Johann Salomo Semler’s most dedicated and passionate students. It was Semler (1725 – 1791), who persuaded him to focus his attention on New Testament textual criticism. Even though it was Semler, who introduced Griesbach to the theory of text-types, Griesbach is principally responsible for the text-types that we have today. Griesbach made the Alexandrian, Byzantine, and Western text-types appreciated by a wide range of textual scholars over two centuries.

After his master’s degree, Griesbach traveled throughout Europe examining Greek manuscripts: Germany, the Netherlands, France, and England. Griesbach would excel far beyond any textual scholar that had preceded him, publishing his Greek text first at Halle in 1775-77, followed by London in 1795-1806, and finally in Leipzig in 1803-07. It would be his latter editions that would be used by a number of Bible translators, such as Archbishop Newcome, Abner Kneeland, Samuel Sharpe, Edgar Taylor and Benjamin Wilson.

Griesbach was the first to include manuscript readings that were earlier than what Erasmus had used in his Greek text of 1516 C.E. The Society for New Testament Studies comments on the importance of his research, “Griesbach spent long hours in the attempt to find the best readings among the many variants in the New Testament. His work laid the foundations of modern text criticism, and he is, in no small measure, responsible for the secure New Testament text which we enjoy today. Many of his methodological principles continue to be useful in the process of determining the best readings from among the many variants which remain.” (B. Orchard 1776-1976, 2005, xi)

The Fifteen Rules of Griesbach

In the Introduction to his Second edition of the Greek New Testament (Halle, 1796) Griesbach set forth the following list of critical rules for weighing the internal evidence for variant readings within the manuscripts.

The shorter reading is to be preferred over the more verbose, if not wholly lacking the support of old and weighty witnesses.

For scribes were much more prone to add than to omit. They hardly ever leave out anything on purpose, but they added much. It is true indeed that some things fell out by accident; but likewise not a few things, allowed in by the scribes through errors of the eye, ear, memory, imagination, and judgment, have been added to the text.

The shorter reading is especially preferable, (even if by the support of the witnesses it may be second best), –

(a) if at the same time it is harder, more obscure, ambiguous, involves an ellipsis, reflects Hebrew idiom, or is ungrammatical;

(b) if the same thing is read expressed with different phrases in different manuscripts;

(c) if the order of words is inconsistent and unstable;

(d) at the beginning of a section;

(e) if the fuller reading gives the impression of incorporating a definition or interpretation, or verbally conforms to parallel passages or seems to have come in from lectionaries.

But on the contrary, we should set the fuller reading before the shorter, (unless the latter is seen in many notable witnesses), –

(a) if a “similarity of ending” might have provided an opportunity for an omission;

(b) if that which was omitted could to the scribe have seemed obscure, harsh, superfluous, unusual, paradoxical, offensive to pious ears, erroneous, or opposed to parallel passages;

(c) if that which is absent could be absent without harm to the sense or structure of the words, as for example prepositions which may be called incidental, especially brief ones, and so forth, the lack of which would not easily be noticed by a scribe in reading again what he had written;

(d) if the shorter reading is by nature less characteristic of the style or outlook of the author;

(e) if it wholly lacks sense;

(f) if it is probable that it has crept in from parallel passages or from the lectionaries.

On Griesbach’s principle of preferring the shorter reading, James Royse offers us a word about appreciating the complexity and exceptions to the rule, “I would certainly accept Silva’s reminder that Griesbach’s formulation of the lectio brevior potior principle is far from a simple preference for the shorter reading, and that its correct application requires a sensitivity to the many exceptions and conditions that Griesbach notes.” (J. R. Royse 2007, 735) On this same principle, Kurt and Barbara Aland qualify it as well, “The venerable maxim lectio brevior lectio potior (“the shorter reading is, the more probable reading”) is certainly right in many instances. But here again, the principle cannot be applied mechanically. It is not valid for witnesses whose texts otherwise vary significantly from the characteristic patterns of the textual tradition, with frequent omissions or expansions reflecting editorial tendencies (e.g. D).” (Aland and Aland, The Text of the New Testament 1995, 281) On this, Harold Greenlee offers us a simplistic balance view of this principle,

(b) The shorter reading is generally preferable if an intentional change has been made. The reason is that scribes at times made intentional additions to clarify a passage but rarely made an intentional omission. Of course, this principle applies only to a difference in the number of words in the reading, not to the difference between a longer and a shorter word.

(c) The longer reading is often preferable if an unintentional change has been made. The reason is that scribes were more likely to omit a word or a phrase accidentally than to add accidentally. (Greenlee, Introduction to New Testament Textual Criticism 1995, 112)

On Griesbach, Paul D. Wegner writes, “While Griesbach sometimes would rely too heavily on a mechanical adherence to his system of recensions, by and large he was a careful and cautious scholar. He was also the first German scholar to abandon the Textus Receptus in favor of what he believed to be, by means of his principles, superior readings.” (Wegner, A Student’s Guide to Textual Criticism of the Bible: Its History Methods & Results 2006, 214)

His choosing the shorter reading of the Lord’s Prayer at Luke 11:3-4, evidence Griesbach’s ability as a textual scholar. He made this decision based on only a handful of minuscule and uncials, patristic and versional evidence. A few short years later, the Vaticanus would confirm that Griesbach’s choice was correct. Today we have one of the most valued manuscripts, P75 and it has the shorter reading as well. Many scribes from the fourth century onward harmonized Luke’s form of the prayer with Matthew’s Gospel.

Luke 11:3-4 New American Standard Bible (NASB / NU)

3 ‘Give us each day our daily bread.

4 ‘And forgive us our sins,

For we ourselves also forgive everyone who is indebted to us.

And lead us not into temptation.’”

Luke 11:3-4 New King James Version (NKJV / TR)

3 Give us day by day our daily bread. 4 And forgive us our sins,

For we also forgive everyone who is indebted to us. And do not lead us into temptation, But deliver us from the evil one.”

Luke 11:3-4 Updated American Standard Version (UASV)

3 Give us day by day our daily bread. 4 And forgive us our sins; for we ourselves also forgive every one that is indebted to us. And bring us not into temptation.

Karl Lachmann [1793-1851]

After two and a half centuries, in 1831 a German classical philologist and critic, Karl Lachmann, had the courage to publish an edition of the New Testament text he prepared from his examination of the manuscripts and variants, determining on a case-by-case basis what he believed the original reading was, never beholding to the Textus Receptus. However, he did not include his textual rules and principles in his critical text. He simply stated that these principles could be found in a theological journal. “Karl Lachmann, a classical philologist, produced a fresh text (in 1831) that presented the Greek New Testament of the fourth century.”[1]

The Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible sums up Lachmann’s six textual criteria as follows:

Nothing is better attested than that in which all authorities agree.

The agreement has less weight if part of the authorities are silent or in any way defective.

The evidence for a reading, when it is that of witnesses of different regions, is greater than that of witnesses of some particular place, differing either from negligence or from set purpose.

The testimonies are to be regarded as doubtfully balanced when witnesses from widely separated regions stand opposed to others equally wide apart.

Readings are uncertain which occur habitually in different forms in different regions.

Readings are of weak authority which are not universally attested in the same region.[2]

It was not Lachmann’s intention to restore the text of the New Testament back to the original, as he believed this to be impossible. Rather, his intention was to offer a text based solely on documentary evidence, setting aside any text that had been published prior to his, producing a text from the fourth century. Lachmann used no miniscule manuscripts but instead, he based his text on the Alexandrian text-type, as well as the agreement of the Western authorities, namely, Old Latin and Greek Western Uncials if the oldest Alexandrian authorities differed. He also used the testimony of Irenaeus, Origen, Cyprian, Hilary, and Lucifer. As A. T. Robertson put it, Lachman wanted “to get away from the tyranny of the Textus Receptus.” Lachmann was correct in that he could not get back to the original, at least for the whole of the NT text, as he just did not have the textual evidence that we have today, or even, what Westcott and Hort had in 1881. The Codex Sinaiticus had yet to be discovered, and Codex Vaticanus had yet to be photographed and edited. Moreover, he did not have the papyri that we have today.

Samuel Prideaux Tregelles [1813-1875]

Tregelles was an English Bible scholar, textual critic, and theologian. He was born to Quaker parents at Wodehouse Place, Falmouth on January 30, 1813. He was the son of Samuel Tregelles (1789–1828) and his wife Dorothy (1790–1873). He was at Falmouth Grammar School. He lost his father at the young age of fifteen, moving him to take a job the Neath Abbey iron works. However, he had a gift and love of language, which led him to his free time to the study of Hebrew, Greek, Aramaic, Latin, and Welsh. He began the study of the New Testament at the age of twenty-five, which would become his life’s work.

Tregelles Discovered that the Textus Receptus was not based on any ancient witnesses, he determined that he would publish the Greek text of the New Testament grounded in ancient manuscripts, as well as the citations of the early church fathers, exactly what Karl Lachmann was doing in Germany. In 1845, he spent five months in Rome, hoping to collate Codex Vaticanus in the Vatican Library. Philip W. Comfort writes, “Samuel Tregelles (self-taught in Latin, Hebrew, and Greek), devoted his entire life’s work to publishing one Greek text (which came out in six parts, from 1857 to 1872).[3] As is stated in the introduction to this work, Tregelles’s goal was ‘to exhibit the text of the New Testament in the very words in which it has been transmitted on the evidence of ancient authority.’[4] During this same era, Tischendorf was devoting a lifetime of labor to discovering manuscripts and producing accurate editions of the Greek New Testament.”[5]

Friedrich Constantin von Tischendorf [1815-1874]

His name was Friedrich Constantin von Tischendorf, a world leading biblical scholar who rejected higher criticism, which led to noteworthy success in defending the authenticity of Bible text. Tischendorf was born in Lengenfeld, Saxony, northern Europe, the son of a physician, in the year 1815 and educated in Greek at the University of Leipzig. During his university studies, he was troubled by higher criticism of the Bible, offered by famous German theologians, who sought to prove that the Greek New Testament was not authentic. Tischendorf became committed, however, that a thorough research of the early manuscripts would prove the trustworthiness of the Bible text.

We are indebted to Tischendorf for dedicating his life and abilities to searching through Europe’s finest libraries and the monasteries of the Middle East for ancient Bible manuscripts and especially for rescuing the great Codex Sinaiticus from being destroyed. However, our highest thanks go to our heavenly Father, who has used hundreds of men since the days of Desiderius Erasmus, who published the first printed Greek New Testament in 1516, so that the Word of God has been accurately preserved for us today. We can be grateful for the women of the twentieth and now the twenty-first century who have given their lives as well, like Barbara Aland.

This is the second principal recension of Tischendorf (as enumerated in Reuss 1872). The Introduction sets forth the following canons of criticism with examples of their application (see Tregelles 1854, pp. 119-21):

Basic Rule: “The text is only to be sought from ancient evidence, and especially from Greek manuscripts, but without neglecting the testimonies of versions and fathers.”

“A reading altogether peculiar to one or another ancient document is suspicious; as also is any, even if supported by a class of documents, which seems to evince that it has originated in the revision of a learned man.”

“Readings, however well supported by evidence, are to be rejected, when it is manifest (or very probable) that they have proceeded from the errors of copyists.”

“In parallel passages, whether of the New or Old Testament, especially in the Synoptic Gospels, which ancient copyists continually brought into increased accordance, those testimonies are preferable, in which precise accordance of such parallel passages is not found; unless, indeed, there are important reasons to the contrary.”

“In discrepant readings, that should be preferred which may have given occasion to the rest, or which appears to comprise the elements of the others.”

“Those readings must be maintained which accord with New Testament Greek, or with the particular style of each individual writer.”[6]

Westcott and Hort’s 1881 Master Text

The climax of this restored era goes to their immediate successors, the two English Bible scholars B. F. Westcott and F. J. A. Hort, upon whose text the United Bible Society is based, which is the foundation for all modern-day translations of the Bible. Westcott and Hort began their work in 1853 and finished it in 1881, working for twenty-eight years independently of each other, yet frequently comparing notes. As the Scottish biblical scholar Alexander Souter expressed it, they “gathered up in themselves all that was most valuable in the work of their predecessors. The maxims which they enunciated on questions of the text are of such importance.” (Souter 1913, 118) They took all imaginable factors into consideration in laboring to resolve the difficulties that conflicting texts presented, and when two readings had equal weight, they indicated that in their text. They stressed “Knowledge of documents should precede final judgment upon readings” and “all trustworthy restoration of corrupted texts is founded on the study of their history.” They followed Griesbach in dividing manuscripts into families, stressing the significance of the manuscript genealogy. In addition, they gave due weight to internal evidence, “intrinsic probability” and “transcriptional probability,” that is, what the original author most likely wrote and wherein a copyist may most likely have made a mistake.

Westcott and Hort relied heavily on what they called the “neutral” family of texts, which involved the renowned fourth-century vellum Vaticanus and Sinaiticus manuscripts. They considered it quite decisive when these two manuscripts agreed, particularly when reinforced by other ancient uncial manuscripts. However, they were not thoughtlessly bound to the Vaticanus manuscript as some scholars have claimed, for by assessing all the elements they frequently concluded that certain minor interpolations had crept into the neutral text that was not found in the group more given to interpolations and paraphrasing, for instance, the Western manuscript family. Thus, Professor E. J. Goodspeed shows that Westcott and Hort departed from the Vaticanus manuscript seven hundred times in the Gospels alone.

According to Bruce M. Metzger, “the general validity of their critical principles and procedures is widely acknowledged by scholars today.”[10] In 1981 Metzger said,

The international committee that produced the United Bible Societies Greek New Testament, not only adopted the Westcott and Hort edition as its basic text but followed their methodology in giving attention to both external and internal consideration.[7]

Philip Comfort gave this opinion:

The text produced by Westcott and Hort is still to this day, even with so many more manuscript discoveries, a very close reproduction of the primitive text of the New Testament. Of course, I think they gave too much weight to Codex Vaticanus alone, and this needs to be tempered. This criticism aside, the Westcott and Hort text is extremely reliable. (…) In many instances where I would disagree with the wording in the Nestle / UBS text in favor of a particular variant reading, I would later check with the Westcott and Hort text and realize that they had often come to the same decision. (…) Of course, the manuscript discoveries of the past one hundred years have changed things, but it is remarkable how often they have affirmed the decisions of Westcott and Hort.[8]

Critical Rules of Westcott & Hort

The following summary of principles is taken from the compilation in Epp and Fee, Studies in the Theory and Method of New Testament Textual Criticism (1993, pages 157-8). References in parentheses are to sections of Hort’s Introduction, from which the principles have been extracted.

Older readings, manuscripts, or groups are to be preferred. (“The shorter the interval between the time of the autograph and the end of the period of transmission in question, the stronger the presumption that earlier date implies greater purity of text.”) (2.59; cf. 2.5-6, 31)

Readings are approved or rejected by reason of the quality, and not the number, of their supporting witnesses. (“No available presumptions whatever as to text can be obtained from number alone, that is, from number not as yet interpreted by descent.”) (2.44)

A reading combining two simple, alternative readings is later than the two readings comprising the conflation, and manuscripts rarely or never supporting conflate reading are text antecedent to mixture and are of special value. (2.49-50).

The reading is to be preferred that makes the best sense, that is, that best conforms to the grammar and is most congruous with the purport of the rest of the sentence and of the larger context. (2.20)

The reading is to be preferred that best conforms to the usual style of the author and to that author’s material in other passages. (2.20)

The reading is to be preferred that most fitly explains the existence of the others. (2.22-23)