#and where does trauma and toxic masculinity overlap

Text

Sniff sniff i’m sick <]:-[

#retro.bullshit#i love my tiny minor antagonist something something how elysium valley is all about the guilt the guilt you feel over loss or avoidance or#wahtever and addressing that guilt and if you leave it to simmer for too long it starts to spill out in unhealthy ways#the first seasons about identity and loss and how when we shape ourselves around another person when we lose that person#we're left not knowing who we are#IE doppelgangers in regard to identity and feeling liek you 'could do better' would my mother be proud of who i am right now#and allowing yourself to be overtaken by something that feels like it can worm its way into your life and consume who you are without notice#also in helens case kind of the complex matter of masking too and internalized ableism#but then the second season is liek about trauma and the exploitation of that trauma by companies in order to profit off of you by claiming#care when in reality things like the pharma companies price things to sucha. degree that people who need these things to survive can barely#afford them and also toxic masculinity#and where does trauma and toxic masculinity overlap#and while helen is opening up to jun and they're healing their relationship and starting to form a healthy connection#in opposition to how Jun was consumed by helens prescense the sun to her icarus#Michael doesn't have an outlet for the grief and trauma he endured during the first season#adn how the evil little guy of the series is now haunting him with this grief in a manifestation of the one person he couldn't save#and how that challenges his view on his masculinity#hes the man he should've saved her instead he stood frozen and watched her die#as if he could've done anything to prevent it#also michaels toxic masculinity is something in the first half too#thats just being more so addressed in the second half#blah blah thats where my sick mind is at now#the elysium valley radio show#i might as well tag the story since i rambled so much in the tags

0 notes

Text

I can't help but notice that back in the first episode, Walker referred to Sam and Bucky as "Cap's wingmen" to Sam, implying that he doesn't really view the relationship between them as anything but this. He sees the Captain as the show and his backup as sidekicks. As much as Walker did genuinely care for Lemar, he also treated him like this in the group settings the whole show. He does all the talking, doesn't introduce Lemar to Sam and Bucky, who have to ask him who he is. Lemar could temper Walker a bit but Walker still sees himself as the show and Lemar a tool to help with his success more than anything else. Why does this matter in the context of Sam and Bucky?

Because John uses the word 'partner' to Bucky twice in reference to Sam and this implies that he can tell that Sam and Bucky roll differently than he does and treat one another differently. But Walker thinks this is dumb because Sam doesn't have the serum and Bucky is stronger physically. He doesn't get why Bucky doesn't act like Walker himself does-- in the leadership role, with Sam following as his wingman.

Bucky replies that Sam has dealt with worse than Karli (and clearly, ironically, means The Winter Soldier in part here, plus Thanos, etc.) He is making it clear that he doesn't see Sam as lesser than him because he's not a supersoldier-- that it isn't all about brute force. In saying this, he's saying that Sam has strengths to bring to the table that are not super physical strength and Bucky respects them. (By contrast, try to imagine Walker recognizing that Lemar had similar strengths. Imagine him saying it aloud, in front of other soldiers, including ones who were objectively physically stronger than him. Impossible, right?) Just by saying this, Bucky is showing another kind of strength that he possesses that John does not-- he's man enough to be a good, respectful partner. Which brings us to that word...

Bucky adds that Sam isn't his partner. This can be read a lot of different ways and has several overlapping meanings that are all probably a bit correct. On one level, he is saying they aren't working together as partners. (Even if the show has proved they are.) They still haven't really defined what it is they're doing together to one another and like hell is Bucky going to let John Walker be the one to label it, right? On another level, saying Sam isn't his partner is saying he doesn't view it that way because he is actually there to back up Sam. He's following Sam. Sam might see Bucky as a partner (even if they haven't discussed this) but Bucky might see it more as his role to back Sam up, similar to how he backed up Steve during the war. Sam, likely, wants to be more partners and has been allowing Bucky that space-- it is what they have evolved into-- but it isn't as clearly defined between them yet. But there's also the other use of it...

Walker, the physical embodiment of toxic masculinity, is attempting to bully Bucky a little, using words because he can't possibly best him physically at this point. The use of 'partner' from Walker comes off as aggressively sexual so here is a case of Walker being that asshole on the football team that we all know he was, trying to look bigger and tougher and more macho through thinly-veiled harassment of guys around him who dared to be comfortable with backing each other up and showing any caring openly. It is worth noting here that we have seen Sam and Bucky's whole evolution in the works here but Walker was just shown two guys he had no idea were arguing with one another because they put up a completely unified front in front of him. To Walker, this all is a little much for him and he tries to slander it by implying that it is gay, which he sees as not masculine.

Bucky denies being Sam's partner here for the already mentioned reasons regarding how they work together and that kind of partnership but make no mistake, he knew exactly what Walker was saying. So, another way of interpreting it is that Bucky was answering not in terms of the field work (where they do act as partners, really, even if Bucky might still be viewing it as something a little different... and, if he is, I hope Sam sets him straight on this being equal footing)... but I think Bucky was answering it regarding the sexual/romantic partners that Walker was trying to call them. But he did so in a way that is protective of Sam and makes him, ironically, a good partner.

Bucky is the character, remember, whose experience in the modern world included testing out and not minding casually outing himself as interested in men in the first episode, to a woman he was on a date with, no less. This isn't to say he's torn off the closet door from the era he grew up in in which he would have had to have been into men in secret. One thing he does get though is this kind of asshole like Walker that has sadly not evolved since the 30s. He responds in a way that he means to be protective of Sam, which is to say with his tone essentially "no, John, actually we are just like this because we aren't assholes like you and even if we were, we would still be better than you." But even if you think Bucky and Sam are already a thing by this episode or are aware of each other's potential feelings, Bucky isn't denying it to Walker as if it's something that makes then vulnerable or lesser as men. He doesn't have the same definition of it as Walker does.

Bucky is responding in a way where his tone says he gets what Walker was implying, thinks Walker is shit for not having a clue when it comes to what being a man is, and then casually answers the question as if Walker had meant field partners because, of course, that's what he meant, right? He makes Walker look stupid (which he is) by answering with word choice that says he didn't get the insinuation, even if his tone says he totally did. So, why not just be like "and so what if we were fucking, Walker! We still could kick your dumb ass anyday!"? Because Sam.

Because Bucky, who knows what it is like to be a soldier forced to sometimes be around guys like Walker, likely does not yet know how Sam approaches it. He likely doesn't know if Sam is out. The canon plays it as if literally everyone just assumes Bucky is bi or gay or basically anything that isn't straight but Sam is a different story. Bucky is not about to out Sam in front of everybody. He likely doesn't know yet how out Sam even is with others or how he feels about it. Out of respect for Sam, he's not about to let Walker's attempt at deriding them get anywhere. They literally could have been sleeping together for awhile now and Bucky is still not going to do anything about others knowing, least of all John Walker, unless or until that is what Sam wants and based on the canon, I would doubt very much if that had been a conversation they've already had by Ep 4.

But Walker, the terrifying awful dumb fuck, tries it again later-- this time, not in front of Sam. He saw what Bucky was doing, understood it, was embarrassed by Bucky making him look like a fool so what does he do? He bullies again. He goes at the core of Bucky in the way only the worst bullies can. He does it when Sam had to be in there alone, with a supersoldier, and Bucky is confident in Sam and giving him the space to do his thing, and then Walker lashes out at this less macho and violent plan to Bucky, calling Sam Bucky's partner again, trying to twist a knife by saying how could Bucky leave Sam in there and does he want his blood on his hands?

It's unspeakably cruel. But you might me mistaken if you think Bucky gave in here, even if it was a worry he had as he always worries for Sam because he cares and he has lost so many people and hurt so many that thinking about it happening again hurts him deeply. Bucky didn't verbally respond to Walker's taunts-- he did something much stronger than words could convey.

He didn't deny any definition of partner for Sam to Walker and he let Walker see how cruel he was by tearing up a bit, the pain in his eyes. Walker had no idea what to do with this. He had been trying to make Bucky angry. Instead, Bucky is silently strong enough to show how he feels *without* masking it all behind a macho, angry cover like Walker. Bucky's face says it all: yeah, you asshole, I love him. Yeah, I'm worried I could hurt him and have his blood on my hands. But also yeah, I survived being the Winter Soldier-- in general and just recently-- and I go to therapy now and I'm making amends and I'm free. Freer than you will ever be because which one of us will tear up and be a little afraid for another man and show him open care in this episode and which one will respond to pain with violence that begets nothing but more trauma and pain? Which one of us, Walker, is a brainwashed soldier and which one of us is a strong, decent man trying to be a good friend and partner? Which one of us, by the end of the episode, will make his partner feel like he'd take the serum in a heartbeat and which one of us will respond to his partner's fear at being vulnerable with "I'm going with you"?

He didn't speak a word in that scene but man. Whew. When it comes to toxic bullies?

Bucky Barnes can do this all day.

234 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ranking : Spike Lee (1957 - present)

There have been countless directors whose careers have spanned my lifetime, but out of these countless masses, the one whom I can find the most in common ground with (as well as endless inspiration from) is Spike Lee. A New Yorker through and through, Lee went from a series of films that seamlessly blended hip-hop and old school Hollywood aesthetics, to personal films, to his take on the blockbuster, and currently, to the point where his canon has earned him artistic freedom and expression that many of his peers have not been able to achieve. He is the perfect bridge between the director-driven mindset of the 1970s and the cultural boundary-pushing films of the 1990s-forward. Not everything that he directed was a hit or a masterpiece, but this man has more iconic films under his belt that some directors have films to their name. That being said, it’s time to stir the pot and make an attempt at the monumental task that is ranking the films of Spike Lee.

I will only be including theatrically released feature films of Spike Lee that I have seen. His documentary work will be excluded, as well as his films I have missed or have yet to see. Here is a list of these films : Da 5 Bloods, Chi-Raq, Da Sweet Blood of Jesus, Joe’s Bed-Stuy Barbershop: We Cut Heads, 4 Little Girls, The Original Kings of Comedy, When the Levees Broke, A Huey P. Newton Story.

20. Oldboy (2013)

Every film that you make can’t be a winner. In the case of Lee’s attempt at remaking Oldboy, there were already two major strikes against it : a superior version of the film already existed, and that version was the middle film of a trilogy. I doubt that even a team of the most talented directors could have made a superior version of Oldboy that surpassed the original, but after 30 years of making films, it’s admirable that Lee would even attempt something so bold and seemingly insurmountable.

19. Red Hook Summer (2012)

When your film catalog covers three decades, there’s bound to be some overlap, be it stylistically or narratively. I’ve only seen Red Hook Summer once, but it was impossible for me to look at it subjectively, as it seemed to be a modern day mirror to another one of Lee’s explorations of New York adolescence. While this story is not a direct copy of a Spike Lee film that I will go into more detail on later, it does feel like the update equivalent that focuses on himself rather than the childhood of his sister. While an entertaining film from what I can remember, it sits behind a list of previous impressive achievements.

18. She Hate Me (2004)

Humor has been an element present in a number of Spike Lee films, but for my money’s worth, this film is the closest thing to an outright comedy that he ever made. Like a number of films on the back half of his career, he is touching upon important topics (sexuality and toxic masculinity, in this case), but these are topics that he has hit with more nuance and creativity in earlier films. This film did help transition Anthony Mackie into a leading man role, and he certainly took that opportunity and ran with it, so She Hate Me could be heralded for that alone. That being said, it was a great idea that slightly missed the mark, therefore placing it on the backend of the memorable films list for Lee.

17. Miracle at St. Anna (2008)

This film had the potential to be a breakout resurgence for Spike Lee. He was coming hot off the heels of Inside Man, a perfect blend of Lee’s style and modern Hollywood fare, so having a period-piece war film seemed like a slam dunk. His cast was strong, while also being filled of relatively unknown young actors on the verge of becoming stars in their own right, but for whatever reason, this film failed to make a connection with the masses. While I do remember mostly enjoying my watch, I also remember feeling a bit underwhelmed by the ending, which in turn left me lacking a reason to revisit it. Maybe it’s a hidden gem that I haven’t seen enough times yet, but at this moment in time, its home is near the bottom of Lee’s impressive list of films.

16. Get on the Bus (1996)

Many people’s eyes were opened to racial injustices during the COVID-19 pandemic, as several African-American men and women found themselves on the wrong end of violent acts from the police and other citizens in the midst of a ‘shelter-in-place’ era. Not only have these injustices been going on for my entire lifetime, but they’ve been a generational trauma for many African-Americans in the United States. When the Million Man March was announced in 1996, it was not surprising that Spike Lee took it as an opportunity to both document the march and build a narrative around it in which he could showcase a collection of actors he’d either featured in past films or would work with in future films. To my knowledge, this is one of maybe two or three films about the event, and it was certainly the film released in the closest proximity to it. For an independent, quick shoot, it definitely stands up, but in comparison to Lee’s other works that benefited from full crews and production schedules, it finds itself paling in comparison.

15. BlacKkKlansman (2018)

Despite the fact that this is the film that finally got Lee some sort of recognition at the Oscars, BlacKkKlansman was not quite the true return to form that many fans of Spike Lee expected. The film had moments of humor, compelling moments that directly focused on racial injustice and systematic oppression, and it pulled no punches while doing so. Like a handful of Lee’s other films, however, this one falls when compared to his other films that deal with similar subject matter. Adam Driver continued to show fans his expansive range, and Jasper Paakonen deserved INFINITELY more recognition than he got, but ultimately, this film checks all the ‘good’ boxes where it was expected to check the ‘great’ ones.

14. 25th Hour (2002)

As the year 2000 approached, Lee seemed to attempt and make a shift from films that specifically spoke on aspects of the African-American experience in favor of occasional films that reached a wider audience. While Summer of Sam would be considered the first foray into that realm, the true mark of this elevated sense of creative duty came in the form of 25th Hour. With the actors in tow, in tandem with the cinematography and skilled directing ability displayed in the film, one would expect a powerhouse movie, but ultimately, the expectations exceeded the narrative of this film. This one is entertaining, don’t get me wrong, but I personally did not find a connection with the story, meaning that the film was, at best, fun to watch.

13. Summer of Sam (1999)

I’ve been a true-crime junkie since my early teenage years, and even the most casual of true-crime fans is more than likely familiar with David Berkowitz, also known to many as the Son of Sam. While Red Hook Summer did come out after Summer of Sam, it’d be hard to deny the fact that Summer of Sam is the last of Lee’s love letters to New York City. This was the film where Spike Lee stepped out of his comfort zone of the African-American experience, choosing instead to focus on more colloquial aspects of the American experience, and for my money’s worth, it was the start of an important shift for him. Despite being light on the Son of Sam action, the actors this film does focus on (and the story it chooses to tell) is a fresh look at a familiar era, and a crowning achievement that signaled new things for Spike Lee.

12. He Got Game (1998)

If you made a Venn diagram of people familiar with Spike Lee, the two biggest circles would be film fans and people who have seen at least one New York Knicks game since the 1990s. Therefore, the only thing that was really and truly surprising about He Got Game was the fact that it took Spike Lee 15 years and 11 films to make a film about basketball. On the outset, that’s exactly what it is : a film about basketball. Viewed with a wider lens, however, this story is a love letter to one of the most popular American inventions, and a story about how it can serve as a common-ground bridge for those from wholly different walks of life. The juxtaposition of Aaron Copland and Public Enemy made the soundtrack provocative, and Ray Allen stood out in his lead role, holding his own against the living legend that is Denzel Washington, who is always good for a stellar performance in a Spike Lee joint. Don’t mistake this film’s place on the list for my feelings about it... this is a stellar film, in my opinion, and one of my favorites to revisit.

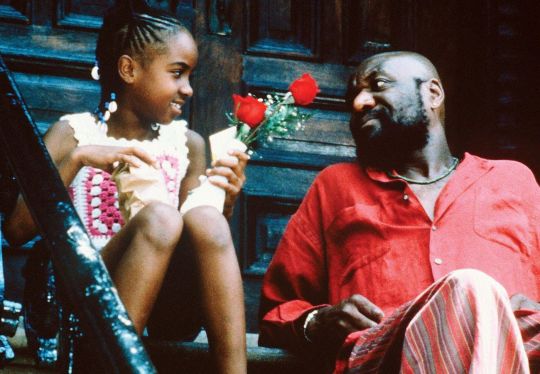

11. Crooklyn (1994)

After making what many would argue to be the most important film of his career (which we will eventually get to), it’s no surprise that Spike Lee circled his creative wagons and made the focus of his next film inward. Crooklyn covers what seem like many personal bases for Spike Lee : he portrays the New York of the past vividly and beautifully, while spinning a true-to-life tale based on his personal experience, but opting to focus on his sister Joie Lee and his father Bill Lee. Of Lee’s many, many films, this was the one that I felt the most compelled to see at the time of release, it is one of the two I have the most vivid memories and recollections of, and it has a number of stylistic choices that keep me wonderfully perplexed to this day. Despite not cracking the top ten Spike Lee films, this one ranks high on the list of Spike Lee films that hit the bullseye of my heart.

10. Jungle Fever (1991)

Interracial romance is one of those things that seemingly will always be a sensitive subject. I’ve heard many people say that Jungle Fever has a dated look on the subject, but I’d argue that the film was very forward thinking, especially in showing that an interracial romance is not the answer to the cultural and societal problems that life presents us. The movie also touches deeply on drug addiction without crossing over into the realm of being preachy or talking down to the viewer. It didn’t hurt that Stevie Wonder also managed to create a soundtrack’s worth of new material that instantly brought the seemingly controversial film directly into the public eye. Maybe it is dated... maybe it is uncomfortable... but what it is, undoubtedly, is an early masterpiece that fell near the end of one of the most stellar introductory runs that any filmmaker has presented us.

9. Clockers (1995)

Ever wonder what would happen if a Martin Scorsese film found its way into the hands of Spike Lee? Well, wonder no longer, because Clockers is out there waiting for you to discover it. The amount that this movie gets slept on is an outright tragedy and travesty. The soundtrack is KILLER, the color-timing puts the viewer in an immediate ‘cold-world’ environment, the order of operations presented in this film is brutal and unforgiving, and yet, it manages to be one of the most heartfelt films in the Spike Lee canon. EVERYONE presented in this movie brought their A-game to the table, from the Spike Lee regulars like Isaiah Washington, John Turturro and Harvey Keitel, to the glorified cameos and supporting roles, like Thomas Jefferson Byrd, Sticky Fingaz and Fredro of Onyx, and relative newcomer but promising leading man Makhi Phifer. This film is intense, but it is more than worth your time and attention.

8. Bamboozled (2000)

Bamboozled was shocking when it was released, to say the least. The true revelation, however, has been the way that relevance has seemingly caught up to the film... fake wokeness, modern day minstrel shows, low budget/high yield television and behind the scenes scandals have all come to light many years after this film had its initial run. While this film did not transition Savion Glover into the world of superstardom and crossover success, it certainly crystalized his immense talent and charisma in a way that his recordings of stage shows had previously been unable to capture. The imagery of America’s strange fascination with the dehumanization of African-Americans for generation after generation is rich, and every performance is compelling. This was definitely Spike Lee’s first masterpiece of the new millennium, and at the risk of being bittersweet, probably one of his last truly stunning achievements.

7. Girl 6 (1996)

Every ranking list has to have the controversial placement, so here’s mine... Girl 6 started as a lingering interest for me. The internet was just about to change the world, but we were still locked into landlines at the time, with cellular being a luxury, so the world of phone sex still had relevance. Upon seeing the film, however, I quickly realized that the phone sex exploration was playing counter to a Hollywood hopeful narrative that was brave enough to explore new ground (per the changing times) while being mindful enough to pay homage to the countless stories of Hollywood hopefuls that came before it. Many of the shifting cinematography looks that made Clockers so gritty were used to make Girl 6 feel dangerously euphoric. The list of cameos and brief supporting roles were not only a who’s who of cultural movers and shakers at the time, but it ran about as long as my arm. I recently revisited the film and expected it to be a bit more on the side of kitsch, but surprisingly, the times had not been as hard on the film as I anticipated. The film shifts quite well between light and dark, and even the ending that initially slightly annoyed me has found a strange sort of charm in my older, more life-experienced years. Add to this the hilarious running joke of Isaiah Washington being a kleptomaniac in nearly every scene he appears in, and there’s a realization that there are sublayers going on right in front of our eyes. This collaboration with Suzan-Lori Parks gives me hope that maybe one day, we’ll get a Spike Lee film adaptation of Topdog/Underdog, but we will see.

6. Inside Man (2006)

If you had to pick the most ‘Hollywood’ of the Spike Lee films, my money would be on this film ending up as the chosen one. By this rationale, it makes the film that much more impressive, as it also stands out as one of the most compelling, well-directed and well-acted Spike Lee films. At the time of its release, it was not only a return to form, but it seemed to signal an evolution. Spike Lee was able to use his signature, iconic shots that he was known for, like his camera-turned-to-dolly float, or the push-pull zooms, but he was also able to incorporate familiar Hollywood tropes, including the twist ending, and give them a breath of fresh air via an newly infused sense of style. Lee also stayed true to himself by educating as well as entertaining, bringing to light how atrocities from the past have more than historical connections to modern day benefactors. While I do think there are a handful of better ‘pure’ Spike Lee films, if I had to pick one movie for a curious party that my be skeptical, this would easily be my pick.

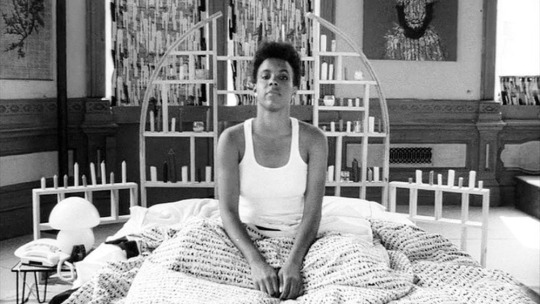

5. She's Gotta Have It (1986)

Oh, the joy of having your first film be a breakout success, but not to the point of pigeon-holing your career. She’s Gotta Have It was an important introductory step to the masses for Spike Lee : it showed his dedication to putting African-American performers into familiar narratives, it showed an appreciation for the voice of women on film that many first-time directors would likely not want to be the initial association to their style, it introduced the world to Mars Blackmon (who became a cultural icon), and it presented sense of style that switched on the viewer the moment before they could label it pretentious. Having characters address the camera made it feel like a play or a novel, but when the film shifted into movie mode, the camera moved with the energy and grace of a performance artist or dancer, which in turn fed into the character development and narrative it presented. As a bonus, the property found new life nearly 40 years later as a Netflix original series, introducing new generations to a modern day classic statement of feminism, and how it does not excuse bad behavior.

4. Mo' Better Blues (1990)

Those familiar with Spike Lee’s family know that he was raised by jazz bassist Bill Lee, who scored some of Spike’s early films. By this rationale, it comes as no surprise that Lee could make such a rich, nuanced and heartfelt film about jazz music that serves as an allegory for the hurdles that beset those driven purely by passion. The conversations about race, musical integrity and commercialism also work on both direct and symbolic levels, giving Mo’ Better Blues some of the highest repeat viewing value of any film in the Spike Lee canon. The film also marked the first collaboration of Spike Lee and Denzel Washington, a combination that yielded artistic, career, creative, commercial and critical success, led to a multitude of classic performances, and ultimately led to a generational collaborative changing of the guard in the form of John David Washington. The only negative I can give this film is that it did not lead to future films that explored genres of music like hip-hop and soul. While She’s Gotta Have It did focus heavily on relationships and intimacy, it could be argued that Mo’ Better Blues was Spike Lee’s first adult contemporary film, and his first look at modern romance in the more ‘traditional’ sense.

3. School Daze (1988)

The African-American college experience, specifically that of HBCUs (Historically Black College and Universitys), is one that has often been neglected in the annals of film history. As a graduate of Clark Atlanta University, it makes total sense that Spike Lee’s second commercial film would focus on that specifically overlooked culture, as it became a fitting vehicle for establishing Lee’s sense of duty and responsibility for education, sharing the African-American experience to the masses, and exposing systematic injustices and hypocrisies that kep the disadvantaged in a disadvantaged position. The real genius of this film, however, comes in the juxtaposition of presentations it jumps between... for the majority of the film, it is an unflinching look at the coming of age process that teenagers must traverse on their way to adulthood, including the hurdles of romance, forming your identity and expanding your view of the world around you. At key moments, however, the film switches into musical numbers, song performances and school dances that not only expand on the inner feelings, emotions and desires of characters, but heighten the reality of the story to a dizzying pace. In all the ways that She’s Gotta Have It put the world on notice that a unique voice was present in the industry, School Daze signaled the continuation of a run that would last another handful of films, and it firmly established Spike Lee as a generational talent.

2. Do the Right Thing (1989)

I would guess that over the course of a career, a director secretly hopes that at least one of their works comes close to making an impact culturally. In the case of Spike Lee, however, we have a man who released two cultural-shifting films, and did so in a span of less than 5 years. They say the third time is a charm, and that’s exactly what Do the Right Thing was for Spike Lee. The vivid colors, stylistic earmarks, historical and cultural sense of urgency and focus on telling minority stories all expanded greatly with this film, which acted as both a parable of how past injustices can come back to haunt you, and a harbinger of how the reactions to these continued injustices would only amplify if not addressed. The fact that Spike Lee not only directed this film, but played the lead actor as well, is a monumental achievement, especially considering how few flaws the film has, if any. Several established actors played some of their most iconic roles in this film, and a breadth of newer, younger faces exploded onto the scene, almost all of whom either continued to work with Lee or found themselves evolving their careers in the wake of Do the Right Thing. The film is also directly responsible for perhaps the most iconic hip-hop song of all time, Public Enemy’s classic protest anthem Fight The Power. Any fan of film would be foolish to skip the Spike Lee catalog, but regardless of whether you’re interested in his work or not, this film is one of two he made that should flatly be considered required viewing across the board. The other one, being...

1. Malcolm X (1992)

For everything that Do the Right Thing did for Spike Lee and those involved in the production, the monumentally powerful biopic Malcolm X did all of that while also managing to humanize, canonize and create and icon out of a man that America tried its best to demonize. The masterful hand that Lee used to direct this film shows, as this film is the most ‘every frame a painting’ in his canon. Everything from the period costuming to the locations to the dance numbers to the cinematography absolutely leaps off of the screen. The editing is kinetic, the performances are full of life and depth, and the narrative does just enough going forwards and backwards to make proper connections without beating it over the head of the viewer. The respect shown to Malcolm X is massive, so much so that almost seemingly overnight, Malcolm X went from being a feared and often heavily criticized sign of aggressive blackness to a commercial commodity and household name, with the famous X suddenly adorning t-shirts, baseball caps and necklaces of all American youth, not just minorities. The impact of this film was so immediate that many schools held field trips for viewings, which further cemented the immediate and historical value of the film. Often, the connotation of saying someone ‘peaked’ for a film so early in their career would be negative, but the heights to which Malcolm X achieved on all fronts meant that even if the rest of Lee’s career was a steady decline (which it certainly wasn’t), he more than likely still would have ended up in a pantheon far above that of the average director.

With projects reportedly in the early stages of development, it doesn’t look like Spike Lee has any plans on stopping anytime soon. I certainly owe it to myself to see the handful of his films and documentaries that I’ve not seen yet... who knows, perhaps I may even go back one day and add the documentaries into the list, or find a surprise gem in one of his more recent movies I’ve yet to see.

#ChiefDoomsday#DOOMonFILM#SpikeLee#JoesBedStuyBarbershopWeCutHeads#ShesGottaHaveIt#SchoolDaze#DoTheRightThing#MoBetterBlues#JungleFever#MalcolmX#Crooklyn#Clockers#Girl6#GetOnTheBus#HeGotGame#SummerOfSam#Bamboozled#25thHour#SheHateMe#InsideMan#MiracleAtStAnna#RedHookSummer#Oldboy#DaSweetBloodofJesus#ChiRaq#Blackkklansman#Da5Bloods

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Come To where I'm from monologues

Describe briefly in a few sentences what each of the Paines Plough monlogues was about?

(Come to where I’m from Plymouth)

This monologue is about a grieving widow who has lost her love at war, there are implications of an affair due to the mention of a “French woman” from the quote “…she was a French woman” which is followed by a pause implying distress and emotional trauma. However, through the use of repetition in the dialogue we hear he recall a story from her and her lovers past involving a piano which contrasts the other themes of the monologue such as war and loss with a more tender moment that she seems to be found of remembering.

(Come to where I’m from Cardiff)

This monologue is about a man recalling his youth, how he was raised in a rough crime infested environment and how this affects him now. He mentions how he had a perm hairstyle and how this made him stand out from the crowd, he goes on to recall being arrested by police after he was found trying to steal a bike. After being held in a prison cell he vividly tells us his memory of being alone in there with a duck, although this seems very random and unrelated to the story completely, this is a metaphor as in the prison cell he realises that he was an ‘ugly duckling’ trying to fit in by making himself different ( the perm) and committing crime out of frustration brought about an epiphany of sorts where he discovers he never needed to change himself to fit in since he was already perfect in himself, very much reminiscent of the ugly duckling children’s tale.

(Come to where I’m from Manchester)

This monologue depicts a retelling of a traumatic event that happened on a drunken night shared between friends, the main character speaks about how he was in deep thought whilst intoxicated however his friends around him where laughing and poking fun at his demeaner. He goes on to tell us about how during this moment of deep thought his friends took advantage of him to such an extreme that he was scared that it would lead to sexual assault, after the moment of the assault ends he stands and leaves the room to only return with a golf club and proceeds to attack his friends out of anger and leaves them extremely injured, we understand this is an attack of revenge to re-instate his manhood amongst other male friends. He ends his story by now describing how this event has shaped him as a man as now he realises that he is not in control of his own temper and what happens when this anger over comes him.

(Come to where I’m from London)

This monologue depicts the story of an immigrant who finds himself in London and now feels this is his true home, he describes the city in a love song like manner personifying the city of London itself. He references modern British pop culture with reference to ‘major tom’ (David Bowie), this reference connects to the story as the song itself describes being lonely and far away from home which this character is himself. He sings in his native tongue for a moment during the speech, connecting us with his culture from back home. Finally the most important message given is that no matter the distance or the place he will be forever connected to his home country.

(Come to where I’m from Liverpool)

This monologue recalls the childhood of a woman from Liverpool in 1988 when she was 12 and in school struggling with severe anxiety, she tells us about the one day she had had enough and decided to not abide by the school rules but instead remain in the toilets even after the bell had rung for lessons. She sits on the toilet and does a certain routine of tapping and pulling on her body in different areas and in very precise numbers implying to us that she had OCD and does this routine in order to calm herself in times of stress. The OCD is so self-consuming that any minor change to her routine be that enforced by teachers or anyone else she MUST find a way to cope therefore adjusts the routine to fit circumstances. The story comes to a conclusion with a revelation of sorts, she is at the beach and gets stuck in quicksand whilst trying to retrieve a ball and escapes without saying or doing her OCD routine which brings about her realising she doesn’t need it to survive in the world.

What images/ characters / moments particularly stuck out for you in any of the Paines plough monologues and why? ( choose 3)

(Come to where I’m from Plymouth)

The parrot, the piano, the French woman, “he was a poet”, “I was a musician”, the audio overlapping at parts. These specific moments/images successfully depict the denial to accept the loss of a loved one to war and that life will not be as it was before.

(Come to where I’m from Cardiff)

The perm, the bike, the duck, the moment when he becomes the duck. These moments/images successfully depict how the main character struggled to fit in in his society and was driven to petty crime to let out his frustrations.

(Come to where I’m from Manchester)

The balls in his face, the description of his friends and his own anus leading to the line “it’s not happening because of who I am, it’s happening because of where I am” implying it was anything to do with him personally but to do with the situation he placed himself in to begin with. The description of the violence in this monologue projects how toxic masculinity and his fragile male ego are the main themes in the monologue and the main causes of his anger issues.

How were the National Theatre Scotland monologues using the frame ( screen) to succesfully tell a story?

National Theatre Scotland’s monologues where presented to us in a very casual listening form, where we can build the imagery mentally and understand/relate to their stories more. Therefore allowing us to implement our own thoughts and opinions as to why characters behaved and acted in the ways that they did making this method of storytelling successful.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

‘Douglas’ Goes Deep Inside the Mind of Hannah Gadsby | Rolling Stone

All stand-up is curated confession, a chance for the person behind the mic to spill their guts but still shape their own narrative — to both tell the audience a story but also let us know how we should be thinking about it. We appreciate great comedians for their humor, of course, but also for their mastery. Like mentalists or con artists, stand-ups know how to pull our strings, how to put us at ease or discomfit us.

No one has had more occasion in recent years to think about the structure of stand-up than Hannah Gadsby. The Australian comic made waves in 2018 when Netflix released Nanette, a special in which she publicly processed her trauma about instances of sexism, assault, and homophobia she’d experienced in her life, all while deconstructing and questioning the format of joke-telling as a way to tell stories about ourselves.

Nanette earned Gadsby both admirers and haters in droves, as any thoughtful and provocative piece of media will in this age of instant public reaction. She went from being a comedian mostly familiar in her native Australia to an international household name, known as a woman who either revolutionized or took an ax to the art form. So it’s only natural that she opens her follow-up special, Douglas, by discussing how this new set will inevitably live in the shadow of her last one.

“If you’re here because of Nanette… why?” she asks her Los Angeles audience early on in Douglas. “What the fuck are you expecting from this show? Because, I’m sorry, if it’s more trauma, I am fresh out. Had I known how wildly popular trauma was going to be in the context of comedy, I might have budgeted my shit a bit better.”

Though nothing since (Douglas included) has quite gone to the places Nanette took us, other innovative stand-ups have been messing with the format in interesting ways since 2018. Gary Gulman experimented with documentary as a means of circling the topic of his depression in The Great Depresh; Jenny Slate meta-critically dissected her own fears about public performance in Stage Fright; Julio Torres utilized tiny objects and a mini conveyer belt to discuss his identity in My Favorite Shapes; and Lil Rel Howery related the story of his uncle’s funeral in a high school gym in Live in Crenshaw. As the diversity of comedians whose work makes its way to the TV-watching public broadens and more stand-up specials get released each year, so too does the format stretch and evolve to accommodate a wider range of both stories and tellings.

Douglas is in many ways a more traditional special, what Gadsby jokingly calls “my difficult second album, that is also my tenth.” But like its predecessor, Douglas is interested in pulling back the lid to see the structure of stand-up; the comic spends the first 15 minutes offering an outline of what we should expect, including “a lecture,” “the joke section” and “a gentle and very good-natured needling of the patriarchy.” (It’s not gentle; more on that later.)

But what might appear at first glance as a list of spoilers is actually Gadsby’s roundabout way of offering insight into how her brain works. Because where Nanette was about the comic unpacking old baggage, Douglas is about a more recent revelation in Gadsby’s life: her diagnosis with autism. Douglas is Gadsby’s attempt to acclimate the audience to her own inner weather system, inviting us into her thought processes and teaching us her own language of personal associations. (She memorably describes a time in school when a lesson on prepositions devolved into a young Gadsby very seriously asking her teacher to explain how a penguin could be related to a box.)

If you’re already a Gadsby fan, odds are you’re very much here for her brand of puzzle-box comedy, the kind that laughs at its own deconstruction. As in Nanette, Gadsby takes aspects of herself that are left of perceived center — her queerness, her femaleness, and, in this case, her neurodiversity — and invites viewers to realign their perspectives. “I’m not here to collect your pity,” she says. “I’m here to disrupt your confidence.”

If this all sounds a little heady for a stand-up special, don’t worry — Douglas is also very funny. Named after Gadsby’s dog but also for a pouch located between the rectum and the uterus in the female reproductive system (don’t worry about it), Douglas covers everything from an awkward interaction at the dog park to Renaissance art to the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. A portion of the set in which she tears antivaxxers a new one — and points out that there are probably a sizable number of them in her audience, overlapping as it does with “rich, white, entitled women” — hits in a powerful way in this time when certain people are refusing to wear masks in public in the middle of a pandemic.

Gadsby also devotes plenty of time to eviscerating that cause of so much collective grief, and the font from which most of her haters spring: the patriarchy. Just like in the real world, toxic masculinity lingers in the wings of Douglas: men telling women to smile, the male gaze in art, men (quite literally) asserting their dominance over women’s uteruses. If your reaction to this topic is that you’re tired of hearing about it, Gadsby would shoot back that she’s tired of living with it.

Gadsby spent much of Nanette questioning her own career-long reliance on self-deprecating humor. In Douglas, she lets us in on the way her mind works not to mock or undermine herself, but to revel in the way she, as an autistic person, experiences the world. “There is beauty in the way I think,” she says near the end of the set.

It’s likely Douglas will earn Gadsby as many hate-tweeting detractors as her last special did, if only for the fact that a woman getting up onstage to talk unapologetically about herself still makes a portion of the population very uncomfortable. But if Nanette was a dirge, Douglas is ultimately a celebration. So, in the words of Gadsby, “If that’s not your thing, leave. I’ve given you plenty of warning. Just go. Off you pop, man-flakes.”

#hannah gadsby#douglas#nanette#hannah gadsby nanette#hannah gadsby douglas#rolling stone#jenna scherer#stand up#comedy#tv#tv review#television#comedy review

0 notes

Text

Moonlight and Nurturing Black Men

I know this is even more scattered than my last post, but I had to get it out and put some distance before I attempt to hone it down into something more. There’s three different threads I want to follow, but each one is important, each one here. —————–

I’ve watched Moonlight twice in the theaters in two days--the weekend it was released. Something about it, my chest was tight the whole time. Nothing good can come of this in the sort of black world Chiron lives in. I fear at each moment for Chiron. I want to jump through the screen and hold him. Tell him he is safe and loved because he expects the opposite of that. When he experiences tenderness, the tenderness that shouldn’t be there, I am afraid that it will be snatched away at any moment. Suddenly, it will all go away. That, to me, is the tension of the movie. That the fleeting goodness might disappear.

And yet, every small bit of the movie brought me a fullness. Small moments of joy. One of James Baldwin’s friends once said that Baldwin was like Dostoevsky. “He is not a pessimist. He layers darkness upon darkness, pain, sadness, then he blasts you with light.” Moonlight could be in that company. The blast of light. That particular blast of light reminded me of another, perhaps more timely, piece. Frank Ocean’s Blond. Frank Ocean helped the writer, Nicholas Britell, visualize the scenes, the script. How? Channel Orange. However, I think Blond is a far better musical representation of Moonlight. In fact, one song could fully represent the movie: Frank Ocean’s “Ivy”:

I thought I was dreaming

When you said you loved me

It started from nothing

I had no chance to prepare

Couldn’t see you coming

And we started from nothing

I could hate you now

It’s alright to hate me now

We both know that deep down

The feeling still deep down is good

I love the quiet intensity of the movie. It kept me tight, wound up, both optimistic and terrified. I’d been thinking about the movie for a bit. It spoke to sexual fluidity, yes, but more to toxic masculinity–specifically toxic black masculinity. This is where, I believe, Frank Ocean, steps in. Our contemporary R&B artists tend to avoid emotion unless the emotion is lust or anger. This is where Frank Ocean stands apart. He sings almost exclusively about vulnerability. No. No. No. Black men do not talk about being young, innocent, and definitely not vulnerable. However, he does so in a way that wrenches the heart. In the same way, Moonlight does. I think it is because I want black men to be vulnerable and true to themselves, but I also fear the backlash for that.

Arm around my shoulder so I could tell how much I meant to you…

meant it sincere back then

We had time to kill back then

You ain’t a kid no more

We’ll never be those kids again

I am saying very little about sexuality in Moonlight because I know many people can dismantle it far better than I can, and this, this, moment of driving down the road listening to Blond brought tears down my cheeks as scenes from the movie flashed in front of me like a trailer. Layers of darkness. A blast of light. Moonlight is Blond. A blast of light in deep blue-black night. Moments to breathe. I have every intention to chew this over more, say more but for now, I have tears in my eyes and both pain and joy in my heart. What is it that I feel has not been said about Moonlight? I think it is encapsulated by Mahershala Ali’s short explanation about why Juan resonates with Chiron. To be an outcast. To feel adrift in the world. Juan feels it–albeit in a different way–and when he sees a young black boy, as young as he was when he realized he was an outsider, he can’t help but to step in. God knows, we miss our elder brothers/fathers to walk us through. It is a moment that makes us hold our breath, a father, a father who will love him and protect him from all of the things that destroy little black boys. Yes, Juan is the local drug dealer, but he loves Chiron fiercely (and wants more for him). I was heartbroken that Juan had such a small role, though powerful. He was a spectre behind Chiron, in a way that his biological father that we never hear of is not. The movie is definitely geared to black men, and I am very willing to play the back. However, it still made me turn inside out as it unfolded. It still made me quiet. I still cannot form words. Maybe it is because I see the pain my cousins and students struggle with all of this and I can’t help. Maybe it is because I want them to step into that blinding light that is self-acceptance. I don’t know. I’ve been working on this over the last two or three days, revisiting the notes I wrote months ago and feeling woefully ill-prepared to discuss this movie. I knew I was bursting, but no way of explaining it.

Last night, I had a long nightmare, the majority of it operated as my typical nightmares–some type of post apocalyptic world in strange things hunt and devour people. I fell. There was a giant tan and speckled crocodile snapping its jaws at me. I screamed “Daddy, save me!” and he appeared and forced it to retreat. Throughout the dream, the crocodile reappears and every time my daddy saves me. In most of my dreams, I am leading some type of resistance, protecting people, killing creatures, but–here, when I am cornered, I call for him. I don’t call for anyone in my dreams. I take whatever comes and if I cannot beat it, I push past it. But last night, I woke up crying for my father when it seemed, for once in the dream, he wouldn’t come. My close friends know that in my dreams, I take care of it. No help. Nobody. It didn’t help that it is very soon the 20th anniversary of my father’s death. How is this related? Because Chiron has been going through the world alone. Then there’s Juan. Juan is his first (and perhaps only protector). What I am saying is that Chiron probably relied on Juan in his absence the way I relied on my father. And that is a conversation we’re not having. Being protected. By our fathers. By our big brothers and uncles and cousins.

No, we aren’t talking about this. This movie is as much about discovering one’s sexuality as it is about discovering one’s need for nurturing. Nurturing and sex overlap, but are not the same thing. Men, especially black men, are told that physical touch only comes through fucking or fighting. And in this contemporary moment, “Netflix and Chill” is code for sex. Not to be physically close to someone, not to cuddle with someone, but to get that nut because to have sex is the only way most people get the physical attention they so desperately need. I was once told that people are starving. Starving to be touched, touch deprived in fact. Hold me. Let me feel you breathe, let me feel warm and safe.

But I am a woman, so they allow it. The thing is, do they do that for their boys? And what is the trauma of not having that from their father? I asked one of the most nurturing black men I know, and he said as a child, he always wanted to bring joy. “I was the hugger of the family. I had to fight back against being bullied as a pansy, but I couldn’t stop. I could see what people needed. When to smile, when to hug. I was naive, but no one hurt me. I just knew I wasn’t acting like the black man I was expected to be.” My father, my uncle, my cousin, they all touched. They were nurturers, the kind that they say doesn’t exist in black men. My mentor, my baba, I could go to his house when he wasn’t there and sleep in his bed. Get that nurturing I so desperately needed. But then again, I was a girl.

This is why Chiron is so thirsty. He’s thirsty for physical love outside of sex. When Juan holds him in the water, teaching him to float, teaching him to swim, it has power. No one has touched Chiron except to abuse him. When we see Chiron held so tenderly by Juan, that idea of the binary of fighting or fucking explodes. Chiron needs this. He’s silent in his starvation for love–conserve energy, don’t waste it, don’t drink too much water, you’re dehydrated, take it easy, slow now–and ekes by. He knows that maybe sex isn’t what he wants. He wants the feeling of love through nurturing in a way that black men are not allowed to know. Hold me. Let me feel you breathe, let me feel warm and safe.

Moonlight offer resilience and healing for black men. But it comes at a cost. You must eschew all false masculinity to get the necessary healing. This movie is not for the uninitiated. This is thick, frightening, sweet, dangerous, healing. It is asking to hold you, “I got you”, it says. It is Juan holding Chiron in the water, swearing to not let anything bad happen to him. It’s trying to hold us, and god knows we’re so starved, we should let it. I am struggling with this. This, sadly, is the best I can do. Hold me. Let me feel you breathe, let me feel warm and safe.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

So Brett Got Confirmed. Now What?

s.e. smith

Brett Kavanaugh may have prevailed in the short term, but he doesn’t get the last word.

The nailbiter confirmation vote for Brett Kavanaugh has many people feeling dispirited and frustrated. Even before the revelations that Kavanaugh committed multiple sexual assaults, the hearing felt impatient and rushed, with Republicans eager to push it through before the midterm elections. After, in the face of dwindling public support and calls for further investigation, it feels like a slap in the face to see the senate voting for his confirmation — and then celebrating it.

If you’re feeling raw, furious, betrayed, or any number of other things after the confirmation, you’re not alone. At Scarleteen, we’re pretty enraged too.

It’s not just that Kavanaugh’s legal history suggests that he will be an extremely conservative jurist who is also pretty sloppy with the rules. It’s also that we spend so much time trying to build a better world for young people, and telling you that being kind and respectful to each other is the right thing to do, and it’s infuriating to see men like him rewarded. And to see people dismissing his abusive history with “boys will be boys.” We know that behavior like Brett’s is the result of unchecked toxic masculinity and privilege, not because he was a teenage boy, and we hope you do too.

Especially if you’re not eligible to vote, you may be wondering what you can even do about the whole Kavanaugh situation, since everywhere you look, the response seems to be “register to vote” followed by “actually go to the polls on election day.” Or it’s “donate to civil rights organizations.” Those are all great things to do if you can, and you can learn more about registering and voting in our primer on the subject, but what if you can’t vote or can’t donate? Or if you want to take other steps?

I rounded up five things that don’t require voting, documented residency, other bureaucratic markers, or cash to make a difference.

1. Talk About Consent

Kavanaugh’s case highlighted the fact that we’re still having complicated conversations about consent, sexual communication, and how to be kinder with one another. Some of those conversations happen best spontaneously amongst friends — and not just in the heat of the moment. Consider using this as an opportunity to talk about consent and learn more about how other people approach the topic.

We advocate for enthusiastic consent, but consent is much deeper than a single yes. It’s about an ongoing conversation, and not just in the sexual sphere. Friendships often involve elements of consent, whether it’s “may I hug you” or “may I talk to you about an emotionally charged issue right now.” Expand the conversation about consent and think about how it applies to your own life; you have the right to your autonomy in any setting, whether the doctor’s office or a sexual relationship and your own home. And you can negotiate and renegotiate those boundaries, whether we’re talking about sexual intimacy or a friend who’s handsier than you’d like in casual social situations.

How do the people around you think about consent? How do you advocate for people who are having trouble articulating themselves, or who are not able to provide affirmative consent? When you see someone pushing another person’s boundaries, do you intervene? Do you have gendered ideas about what kinds of consent people give, and in what situations?

2. Care for Survivors

The Kavanaugh hearings and confirmation vote were extremely difficult for some victims/survivors of sexual assault, some of whom live in silence and couldn’t even speak out about why they were experiencing pain. Being mindful of survivors is a good idea all the time, because chances are statistically high that someone in your social circle has experienced harassment or assault, but especially when these topics are in the news.

Survivors may be struggling with feeling like their trauma has just been refreshed and then denied; for a moment, it felt like people were validating feelings of violation and abuse, and then Kavanaugh was confirmed anyway. But some people may also have been struggling with issues like not being the “perfect” survivor, or speaking up and being ignored because of who they are.

How can you care for a population that might not always be visible? Make it clear that you are working to make the spaces around you safer for survivors of sexual violence from all backgrounds, and all levels of healing. Shut down rape jokes, victim-blaming, and comments that can make environments feel hostile and unwelcoming. Promote affirmative, enthusiastic consent and gender justice, and be mindful that sex workers, people of color, disabled people, and others in marginalized groups are at greater risk of sexual assault, while simultaneously being less likely to be believed or helped when they speak out about it.

If someone does open up to you, tell them “I believe you” and “I’m listening” and let them progress at their own pace. Tell them you’re happy to help them connect with resources, but you respect their needs and choices.

3. Defend Sexual Education

The Trump Administration is launching systematic attacks on funding for sexual education — it’s getting harder to access comprehensive, age-appropriate sex and gender education in many parts of the United States. And while lots of opinion editorials recently have proclaimed the need for “consent education,” sex education is bigger than that.

Information about the full spectrum of human gender and sexuality helps you make informed choices about both your body and your heart. Everyone deserves access to that education, provided in a setting and format that’s conducive to education; no cheesy half-hour video in the gym, please!

Changes to sexual education curricula happen in a number of ways, and you can intervene at each step. In addition to relying on federal funds, sexual education in your area can come from the state and community organizations as well. All of this funding can come with strings attached — and you can be involved in the decisionmaking behind those strings by submitting public comments to the people and agencies involved.

You can also get active with your local school board, which has a tremendous impact on policy across your district. School board meetings are often poorly attended, and the elections are often uncontested, too. Consider attending meetings, or at the very least, reading the agenda packets and submitting comments. The more you go and engage, the more seriously they’ll take you when you comment on agenda items or bring up issues you want them to address; they say “politics is made by those who show up” for a reason.

For bonus points, check out the requirements for school board officeholders. You might be surprised by who’s eligible to run!

4. Advocate and Agitate at Your Own Pace

In coming years, a series of important cases will work their way to the Supreme Court, and Kavanaugh may decide their outcome. You may hear people saying “we should take to the streets” after unfavorable verdicts, which can be empowering and energizing, but isn’t an option for everyone, for a variety of reasons. You don’t need to explain or justify yourself if you can’t engage in direct action — maybe it would threaten your immigration status or health, or maybe it’s just too scary for you right now. That’s okay!

There are lots of ways to make a difference. If you don’t want to take to the streets (or even if you do!) there are lots of things you can do to support social change. For one thing, all those marches actually need a lot of logistics, from developing accessibility plans to making signs, and someone has to be at home to pick up the phone if people get arrested and need someone to bail them out. Being on the support team is a vital part of making change happen. So is participating in letter writing campaigns; joining social media events; attending local government meetings; starting conversations at the dinner table; pushing for changes in your classroom, and so much more. Do the work that you feel able to do, and support others doing their work — and if you are one of the people fearlessly taking to the streets or calling your representatives every morning, don’t give people a hard time if that’s not within their capacity right now.

Social change doesn’t happen overnight. If you’re angry right now, think ahead to your potential career as well as volunteering opportunities. Maybe you’re already thinking about going to law school and joining one of the many organizations using impact litigation — lawsuits that rely on a big case that could set a precedent, like Obergefell v Hodges, which legalized same gender marriage in the US — to make a difference. Maybe you want to become a social worker who supports people in immediate need; volunteer on a sexual assault hotline; run for office; or start a spa that offers free and reduced-cost hair and skincare to low-income people who want to look their best for job interviews. Start learning about what will help you achieve your dreams of a better world.

5. Participate in the Process, at Any Level

At times like this, it often feels like the system is broken, maybe even irreparably. How can someone win the popular vote and still lose the election? How come votes in some places seem to count for more than others? How can elected officials and the people they appoint blatantly engage in criminal activity and apparently get away with it? If you’re having these feelings of defeat and frustration, you are not alone.

But you are also in a position to make a difference, because you do care, and the work of caring people can change the world — or at least pave the way to make that change possible in the future. Dedicated, loving humans have always existed, even during extremely dark times, and some of them changed thing by working within the process, like Oskar Schindler, who saved over 1,000 Jewish people during the Holocaust by leveraging his Nazi connections, subverting the system in a pretty spectacular way.

While it may seem pointless, participating in the process really does make a difference, even, and maybe especially, when your participation is actually designed to fundamentally reshape the process because it’s messed up and unfair and you think it has the capacity to be better. Sometimes that can mean voting, at any level. It can also mean attending meetings and events, submitting formal comments, contacting elected or appointed officials who work for you, or even going to work for a government agency yourself.

Find the kind humans who care and are doing their best and support them. Find the unkind humans who are being cruel, and work to push them out. Because kindness does prevail through darkness.

life in hell

politics

united states

SCOTUS

rights

anger

change

coping

action

activism

self-care

kindness

consent

survivors

advocacy

sadness

vote

seriously please freaking vote

Politics

from MeetPositives SM Feed 4 https://ift.tt/2P1qKS9

via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

A Sex Positive and Transformative Justice Approach to #MeToo

Raechel Anne Jolie

Ready to take #MeToo to the next level?

This essay includes descriptions of sexual violence.

I thought this was going to be an essay about my first and most traumatic #MeToo story. The story of the time when I was 12, and held down on a bed by my mom’s then-boyfriend who told me he’d love to go down on me. It was going to be an essay about my fear and panic and how I didn’t even know what that phrase meant. It was going to be an essay about how heavy his body was on top of mine, how he felt like a plank of concrete, and how I could barely breathe through my weeping and begging for him to leave. It was going to be an essay about how he smelled like Listerine and gasoline and how the scent of each of them, to this day, fills my stomach with knots and bile.

But I realized that I don’t want to tell you more about that, nor the countless experiences I would have after of men touching me without permission, standing too close as a means of intimidation, commenting on my clothes or my body, fucking me even after I said no, (and so on).

I don’t want to talk about those things, because I hope by now you know that if you see a woman, you are, more often than not, also seeing a living history of those kinds of stories of abuse, assault, and terror. Too many people (women, trans and non-binary folks disproportionately) have borne the brunt of so much sexual and sexualized violence, that it has become part of our skin. It is why, I surmise, that when, in the yoga classes I teach, I press into the hips of women in half-pigeon pose, they tremble beneath my palms. We carry trauma in little pockets tucked awkwardly and persistently between our muscle and bones. We are all sewn up with these memories, clinging and wrestling below our surfaces. We know they are there. And now, finally, most others who have not experienced this personally (largely men) seem to be acknowledging this too.

So that’s not what this essay is going to be about. This is, instead, a story of the other times. The times when sex went right, when consent was enthusiastic, and also the times when it was somewhere in the middle. And I want to talk about these good times and these confusing times because I am a sex-positive prison abolitionist, and believe that putting transformative justice theory into action most commonly emerges in the most challenging, triggering, and seemingly egregious situations. And although it seems like perhaps there is an exhilarating shift in the tide — as men are finally being called out and women are finally being believed — I am not sure that this will ultimately eradicate rape culture either. But I do think putting these two frameworks — sex-positivity and transformative justice — in conversation with these abuses may provide us new and effective avenues for change.

In their edited collection, Yes Means Yes! Visions of Female Sexual Power & A World Without Rape, Jessica Valenti and Jaclyn Friedman argue that “no means no” as an anti-rape framework leaves little room for a culture to value sexual pleasure. They write that they want to explore “how creating a culture that values genuine female sexual pleasure can help stop rape, and how the cultures and systems that support rape in the United States rob us of our right to sexual power.”1 This book was an early lesson in my development as a sex-positive feminist, and I think the concept of “yes means yes” is worth revisiting, especially in this current moment.

I am not trying to argue that we shouldn’t tell these stories of harm, or that we shouldn’t hold men accountable. The recent call-outs and testimonies as one very important tool in addressing toxic masculinity.

But what would it look like if we also combatted the behavior of sexually abusive perpetrators with stories of men (and other genders) who do it right?

As one of my sex-positive, transformative justice heroes, adrienne maree brown, recently wrote: “It is humbling to realize that the majority of us are trying to reach pleasure through the complex trauma of transgression. In the onslaught of unveiling, I thought it would be useful to take a step back and address something crucial: the pleasure of consent.”

So what if, instead of sharing the story of when I was 12, I told you the story of how when I was 16, the 20-year-old barista who made out with me after punk shows told me he wanted to be respectful of my boundaries and when we started to have intercourse one night, he paused and asked if it was okay, and when I said I wasn’t sure, he stopped without protest? What if, instead, I told you about how when I did eventually start having sex with a different boyfriend that it was tender and protected and discussed at length in advance? What if I told you about how the first time I explored dominant/submissive dynamics, that my partner went slow and checked in all the time, and would back off in response to my body’s signals, even when I verbally (and unconvincingly) said it was okay to keep going?

Or what if we talked about the incredible heat of consensual foreplay; of hands on hard dicks, and fingers in wet cunts, and tongues desperate for mouths? What if we talked about explosive orgasms, and the silly and joyful pleasure of sexting? (What if we asked why these kinds of sentences are more often censored than sentences about sexual harm?)

And what if we also talked about the times that were neither entirely consensual but also not entirely abusive? Like the time, with a person I met at a party, when I was drunk and so was he and that although he fucked me and I barely remember it, it didn’t feel traumatic and I don’t consider it rape. (Which is not to say others wouldn’t be traumatized by it, or consider it rape, which would also be true, and which is why this is all very complicated.) Or like the time I was in a toxic relationship and my queer partner and I, at different times, pressured each other for sex, and how often we’d feel upset or confused after, and how we talked through those moments and cried and went to therapy and did the hard work of rebuilding trust in our intimacy. What if we talked about how I didn’t want to publicly shame and call-out any of the people from these in-between scenarios, but instead wanted to think through mutual complicity, and solutions on how to heal to do better moving forward?

This is where transformative justice comes in. According to the organization Generation FIVE, transformative justice “responds to the lack of — and the critical need for — a liberatory approach to violence. A liberatory approach seeks safety and accountability without relying on alienation, punishment, or State or systemic violence, including incarceration and policing.”

In the most simple terms, transformative justice acknowledges that “hurt people hurt people,” and that the causes of harm are largely structural rather than individual. Further, given that the State is the cause of so much of the cultural conditioning of harmful behavior, we should not rely on it to solve problems. Which is to say: throwing our rapists in prison does not stop rape, but it does further entrench a reliance on the prison industrial complex and the State more generally. Given that one of the biggest root causes of sexual violence is toxic masculinity, we ought to address the culture that breeds it, instead of excommunicating and disowning individuals who are products of it. And that we especially ought not try to address toxic masculinity through an industrial punishment system that is seeping with it.

That said: transformative justice does not shirk individuals of responsibility and accountability. And although there will be instances when transformation may be near impossible, it doesn’t mean we should dismiss accountability and healing work as a desperately needed tool in our fight to end rape culture.

In a discussion with transformative justice activists Miriame Kaba and Shira Hassan, Kaba states:

We have to complicate this conversation around sexual violence and see all the different ways that it is used as a form of social control across-the-board, with many different people from all different genders and all different races and all different social locations. If we understand the problem in that way, we have a better shot at actually uprooting all of the conditions that lead to this, and addressing all of the ways in which sexual violence reinforces other forms of violence. Our work over a couple of decades now has been devoted to complicating these narratives that are too easy, these really simple narratives around a perfect victim who is assaulted by an evil monster and that is the end of the story. The “Kill all rapists” conversation, which just kind of flattens what sexual violence really is, that doesn’t take into consideration the spectrum of sexual violence, therefore minimizing certain people’s experiences and making others more valid.

I echo Kaba and Hassan in this call for nuance, and am wondering what it might look like for the feminist movement to embrace complexity when thinking about sexual violence. And this is especially important for feminists who claim to be invested in fighting the carceral State—in other words, the way the prison system operates as a tool of governing. Can we actually be anti-prison activists who believe in the redemption of the abstract masses behind bars, and simultaneously call for the public disownment of perpetrators in our activist communities and families? This is the hardest work of all, especially when perpetrators are rich and powerful. But it might be necessary work, if we are truly committed to an end to sexual violence, to consider that people like Harvey Weinstein, Kevin Spacey, and Louis C.K. are actually human beings who are not only capable of doing better, but might even deserve some compassion. (I know, I know... it’s not easy; but being compassionate toward perpetrators as victims of patriarchy does not diminish compassion for victims. Compassion is not a finite resource.)

And showing compassion to abusers does not mean protecting them from consequences, or from confronting the harm they have caused. In fact, in affirming the humanity of perpetrators, we recognize, as Maggie Block recently wrote, that:

Rapists can be our children, our siblings, and our parents, rapists can be our good friends, or our partners, or a member of our church community. Because we live in rape culture, there are lots of people who think their actions are totally normal and acceptable, even when they commit sexual assault and rape. And we as their community members need to not only teach them better, but we need to hold them accountable. If someone we love, someone who shows us their best self, someone who we know to be a very good person is accused of rape, we must believe the accuser. Just because we love someone does not make them incapable of rape, and if we spend all our time fighting for them, all our passion worrying about how hard it is for the perpetrator- we make it harder for survivors, we further engrain rape culture, and we do nothing to help the perpetrators we love to be better people.

Transformative justice makes space for holding these multiple truths. That perpetrators can be good people who do bad things. That we should believe victims no matter what, and also that we shouldn’t silence abusers, so that we can begin to engage with what they did and didn’t understand about their behavior. That while traumatizing an abuser through public shaming is not aiding in healing the cause of harm, it is also not a victim’s job to do the healing. These sometimes conflicting truths and gray areas are not easy to grapple with, but to address a complex issue, we must respond with complex solutions.

So, I want us to think beyond public shaming and expulsion. I want us to think beyond the tools provided to us by the carceral State, and I want us to refuse to be content to only hear about women in relationship to sex when they are victims of harmful iterations of it.