#and since my mom got rona we all have to wear masks at home so who better to draw than Bestie

Photo

mask time

#rgg#ryu ga gotoku#ryu ga gotoku 7#yakuza series#yakuza 7#yakuza like a dragon#joon-gi han#yeonsu kim#snap sketches#//the government trying to break my fingers so i stop drawing today// NO JUST ONE MORE JUST ONE MORE I PROMISE--#listen i was just one drawing short of making ten doodles this year so far alright i had to get one in#and since my mom got rona we all have to wear masks at home so who better to draw than Bestie#ive been wantin to draw him for a while- or properly anyway i still remember that lil doodle i did#the first time i drew him i didnt really like it and ive been haunted ever since SO here's so Kinda redeem myself to myself#OK NOW IM GOOD IM DONE FOR REAL THIS TIME BYE#if im back on here tonight shank me

143 notes

·

View notes

Text

Quarantine, Day 80

I acquired more toilet paper today! Go me! This is becoming less of an accomplishment as supply chains catch up with the needs of American bottoms, but it still feels nice, especially since it's my favorite brand. I found it at CVS so I had to pay a considerable upcharge for it,but such is life. I suspect that from this point on in my life, I will have a month's worth of toilet paper in storage at all times, along with my two weeks of food. One day the kiddo will inherit a closet full of pristine vintage TP still in the plastic packaging and think "Mom never really was the same after the 'Rona came through." But he'll never have to consider the benefits of a bidet!

Today's trip out was to CVS and the day old bread store. The CVS trip was necessary because I had a prescription refill to pick up, and I also took the opportunity to buy very expensive toilet paper and moderately expensive milk. Everything at CVS is extremely fucking expensive unless you have the right coupons, and then it is free. Back when the kiddo was a baby and we were living on 2000 dollars a month in grad student stipend, I kept him in diapers almost solely on the grace of my couponing prowess. Back in the late twenty-teens, shows like Extreme Couponing hadn't ruined coupons yet, and if you were smart and watched the ways the stores timed their sales, you could get really, really good deals on stuff. I made it a point to never be an asshole about my coupons and let people go ahead of me in line when I had something complicated to do, but I still managed to get 80-90% off on a lot of transactions. CVS and Walgreeens were definitely the best for it. Being able to combine in-store coupons with manufacturer's coupons plus the store's own Value Bucks systems meant that in certain weeks, the store was actually paying me to shop there. Most of the time it was a matter of several complex transactions that resulted in a very unique assortment of items, but I could always donate my excess toothpaste or shampoo or soap to the food pantry. They give away that stuff too, and it is often in demand.

Anyway, diapers are stupidly expensive and WIC doesn't cover them, so I was always on the lookout for coupons, and always buying ahead. I had a buy price and a stock up price, don't remember what they were now, but I was very serious about them. At one point half of Kiddo’s closet was stacked full of diapers in varying sizes all the way up to toddler sizes, even though he wasn't sitting up on his own yet. Oh, and that was back before Diapers.com got eaten up by Amazon too, and they were super bad about checking to see whether you really were a new user and entitled to that 40% diaper discount, so every time I got a coupon, I really went to town. Small wonder they didn't end up profitable, whoops. But my kid never went bare-butted!

What the hell was I even talking about? CVS, right. Anyway, it truly pains me to buy anything full price at CVS, but it extends the time between full-on grocery store visits and nearly everybody was wearing a mask, so I'll take it for now. One day I shall unlock their coupony puzzles again! The day old bread store was just for bread, buns and snack cakes, quick in and out. I haven't been there in several weeks and they'd rearranged the whole store, making it a one way loop (it is a little store) with one right hand aisle and two left hand aisles. This leaves customers at the end of the only right-hand aisle with the difficult choice of whether you want to go down the aisle with the mini-doughnuts or the aisle with the peanut butter chocolate crunch bars. (the peanut butter bars are always the right choice, but it was not easy.) Got out of there in five minutes and headed home. The day old bread store is the opposite of CVS, it is always cheap and there is never a challenge. I got my $5 bags of brioche style hamburger buns for 99 cents and didn't even have to try.

Takeout from a local restaurant for dinner, it was good even though they forgot the two bottles of their in-house ranch dressing we ordered. We'll pick it up Monday so it's not a big deal anyway. They thoroughly redeemed themselves by construing "extra feta" for two orders of greek spaghetti as meaning "basically an entire square styrofoam container of feta cheese that you may cake on your food at will." Tomorrow's lunch will be spinach and feta quesadillas, I have a recipe! After dinner the kiddo and I went outside and, rather than starting the campfire in the extremely wet firepit, we used fireplace matches to set fire to marshmallows speared on chopsticks. It would not be any good for golden toasting a marshmallow, but when all you need is for that sugar to catch fire, it's just fine.

Today also marks the end of Book One in our Avatar rewatch. It was all very exciting, and the kiddo is very into it. I am way deep into reading Avatar fanfic right now, some of which is very good and some of which is obviously people just wanting to wrap Zuko in a blanket and carry him home. (These two things are not mutually exclusive, but there is a woobification threshold beyond which it is just hilarious.) Kiddo was baffled at the end of the last episode when I laughed and said "Hello, Azula..." because he didn't remember who she was. He'll figure it out, and probably be glad he's an only child.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

May 9, 2020

Day 130 of the Cute Campaign: Yes, guys, gals, and nonbinary pals, today was, indeed, a cute day. I spent quite a bit of it nauseated in a car (my first car ride in nearly two months (the last time I was in a car was Friday, March 13), actually), but my lipstick was poppin so that’s ok.

Day 58 of The Q: Went to deliver cinnamon rolls to my mom’s friends and some family! It was awful. I was nauseous most of the time because I get severe motion sickness. Also, much to my mother’s dismay/annoyance/frustration, my grandfather (her dad) still refuses to wear a mask. I don’t think he believes in the destructive power of the virus, and that’s especially bad for him because he is older and he is the caretaker of my grandmother. Two of his brothers were at his house today and both of them were wearing masks, and my grandfather was really upset that me, my mom, and my sister wouldn’t get out of the car to greet him. He doesn’t understand that we’re doing this to protect him and his wife. He was upset that he got to see us “for the first time since Nina’s gotten back home” (which is factually incorrect because we’ve video-chatted multiple times, but he doesn’t consider that to be “seeing someone”, and also I’ve been too busy this half of the semester to even try going out to visit people) and we didn’t even get out of the car to say hello/hug/greet him. I honestly don’t know which part about the virus literally killing people he doesn’t understand. He thinks it’s a big conspiracy (set by Republicans? by Trump? by white people?), and I just don’t know how to talk to him about it.

I think part of my problem is simply that I want it all. Like, I don’t want to just be one thing, you know? I want people to me as an intelligent person. I want to study ancient history. I want to work in a lab. I want to act. I want to engage with people. I want to write. I want to be famous. I want to live in a little cottage. I want to live in a city. I want to find someone to love romantically. I want to travel and explore world history. I want to sing. I want the applause.

Is this my lack of focus coming out again? Is it even possible to live so many lives in the span of 80 or so years?

Anyway.

Remember how the archaeology summer study abroad trip to Ireland was sort of what propelled me into Anthropology earlier this semester? Yeah, well, I’m afraid of Ms. Rona messing that up. Like, we have no idea how long these worldwide changes to our lifestyles could last, and some of those changes have impacted travel. What if summer study abroad gets cancelled next year too? Well, maybe that’s gazing a bit too far into the future, but I suppose I could look into getting an internship or participating in another field school nearby or across the country somewhere. I still am interested in living history (despite... issues that I can discuss later), but I should probably look more into cultural resource management or biological anthropology with a focus on history (as opposed to modern forensics because Lord knows I don’t want to be doin’ autopsies or nothin’) to get more experience with my chosen field (assuming I’m still interested by next summer lol).

As for living history issues, well, I’m black. And while I spent much of my young life trying to forget that, I think, I’ve come to really be proud of that part of my identity. So like, even though slavery 100% was not cool, I have some sort of solemn appreciation for my ancestors who were brought here and survived, though I don’t really know much about them.

Speaking of my ancestors, I think I want to record an interview with my grandparents. Like, there’s so much I don’t know about my own heritage because records weren’t really kept for slaves in the same way, you know? I know that my grandfather’s grandmother was an emancipated slave and that he knew her, and since I want to use my profession to study and interpret history, I feel like it’d be fitting to, as one of my first anthropological acts (I assume), record a spoken history. My grandparents are getting up there in age, and I don’t want their stories to be forgotten. No one deserves to be forgotten. I think that’s one of the things that’s eventually driven me to Anthropology/Archaeology. I want to build a legacy, and I recognize that everyone else has a right to a legacy as well. I wrote about that in my essay to my Choice 1. About Star Trek and legacies and being remembered. Forgetting people is absolutely one of the saddest things that can happen to us, I think. No one deserves to be forgotten. We can at the very least learn from unfavorable people of the past. And we can celebrate the “ordinary” people, too.

Back to living history and blackness: I’m afraid that the color of my skin will hinder me from being able to effectively play a role in living history internships/jobs. I know there are black reenactors (notyourmamashistory on instagram!) who do incredible work with their research and interpretation of slavery to the general public, but a lot of these internships don’t exclusively have positions for black reenactors. Why? Well, almost all reenactors are white. Living History is something that I would love to at least try at some point in my life, and I’m sure there are locations where my skin color wouldn’t matter to the bosses, but I also know that visitors can be cruel, you know? “I can see that you’re black. Is that historically accurate?” Or, even more overtly, “I don’t think that there were any black people in this role at this time.” And to put a young adult into a role where they’re playing a slave 5-6 days a week for an entire summer without proper support or guidance from her bosses while her white counterparts are playing upper class roles... I would imagine that an experience like that can be extremely psychologically damaging.

So, yeah. Living History sounds fun, but there are a lot of fears that I have about it.

Along the same lines: LARP. I know that a lot of people who do LARP (live-action roleplay, for those unfamiliar) are geeks and whatnot, so they’re used to not exactly “fitting in.” But I imagine that some of these people are also the people who stand firmly by George R. R. Martin in the idea that Medieval history was all-white-all-the-time and that there’s no room for Others unless they’re the barbaric bad guys. I’m both afraid of feeling out of place and afraid of people making me feel unwelcome because I don’t fit into the typical profile of someone who does LARP. Again, it’s another thing I want to try, and I know that there will be groups who don’t care that I’m black and playing an elf (and not a Drow (though that could be fun for a game maybe)), but I have to make sure I find them first, you know?

These are just things that I have to be acutely aware of. And I know that it’s not something that will ever be a problem for my DnD-friend (unless she encounters sexism, I guess, but I don’t really see that happening), and there’s not really anyone I’d be okay with sharing these kinds of worries I have. Obviously, if I encounter an issue while at an event with my DnD-friend, I’d tell her, and I’m sure she’d understand, but I don’t want to, like, jump the horse, if you get what I mean.

Alright. On the page of LARP, I’ve got a lot of sewing projects that I want to do this summer. I want to finish my swing dress (I’m sure I only need one or two ore 6-hour sessions) first. Then, I want to make a Renn Faire/LARP costume/kit. I intend to have multiple pieces for these (underdress/shift, overdress, corset, overskirt, cloak, sword, bracers, boots/shoes, belt(s), belt bag(s), wooden instrument (recorder? mini piccolo??? fife (basically a cross between the two!!)???????), proper ears, wineskin (for water lol, I just think they look cool), and probably some wooden cutlery) so that I can switch them out as I need to. Especially for things like the overdress and overskirt, where changing the color can change the outfit, I’d like to have multiple versions of roughly the same piece. So I already know that I’ll be writing a ton this summer for the audio drama project, and I think that the rest of my time will probably be spent sewing, designing, working on audio editing, and maybe applying for scholarships so that I can do the study abroad next summer. That sounds like a pretty solid time, if you ask me. In addition, I’d like to practice on my flute and saxophone because I miss them.

Today I’m thankful for Sunkist Orange Soda because sometimes I just really crave that fizz.

Here’s to my last week of freshman year!

1 note

·

View note

Text

I found out that my family has been exposed to Covid for OVER A WEEK.

That one of my husband’s Co-Workers has tested positive. A co-worker who refuses to wear a mask properly... A co-worker that is a Trump Supporter... do I need to say more about my fury right now...

I had Cancer...

My son is Medically Fragile...

I was supposed to go tomorrow to finally get my official “In Remission” check up... which has been pushed back 3 times since May between Covid shit and my son’s health.

I want to actually go find out where this motherfucker lives that exposed us all for SELFISH ASS “I FELT FINE AND DIDN’T NEED TO TAKE OFF WORK, THE RONA IS JUST A COLD MAN” reasons... tell him all about himself...

as if it being the anniversary of my mom’s death in 2 days isn’t bad enough... now I am literally stuck at home... we don’t have the groceries we need... I don’t have shit...we are on food stamps so I can’t use instacart...

So I got to make a whole bunch of lovely calls to my doctors... to my son’s explaing we have been exposed now for a week. We were at the hospital for my son on friday... and I am freaking out...

Send me calming thoty John Seed thoughts.... cuz I am about to loose my shit.

0 notes

Text

Quarantine Days

Kevin and I have been making the best out of staying indoors. Two things we are very grateful for:

We are healthy (though Kevin gets paranoid from time to time “my stomach hurts, do I have the rona?”)

We still have our jobs. Luckily our jobs can continue to be done remotely. That being said, everyone’s hours at my company, Barr Engineering, have reduced to 32 hours a week, reducing my pay. And Kevin has been having a bit of an issue lately trying to sell services with the current situation. Nonetheless, things could be worse. We could be one of the 22 million people filling for unemployment.

We spend our weekdays very busy working until 5pm. Kevin upstairs in his “Business Center” he calls it, which is basically a camping table set up in our bedroom, with a chair from our dining room and a monitor from his office. I’m downstairs in the office area, I already had a monitor and standing desk since half the time I already worked from home. So I was set.

When 5pm comes around, we do home workouts. Either online yoga with friends through zoom, boxing class, HIT (High Intensity Training), ab workout class, dance class with my mom… we are trying to stay active.

When we’ve had nice days, we go outside to the park to play frisbee, bike or go for a run.

Last time I saw any friend/coworker (people I normally interact with) was March 10th. It’s strange to realize it’s been over a month now. Time has passed by really fast for me. Luckily, I have many hobbies and things I’ve been wanting to do but never had enough time. Well, I’ve been doing all of them now!

1. I created two new hats for upcoming Kentucky Derby parties (yes, for the years 2021, 2022). That’s how far in advance I plan and here’s one of them, garden gnome themed:

2. I’ve gotten back into my Rosetta Stone studying French. My daily goal is to do 30 mins. I’ve been pretty consistent!

3- I sewed a bunch of clothes I’ve been wanting to hem/fix.

4- I’m finishing D-Day Girls book.

5- Reorganized EVERYTHING

The tool box (as in go through every crew and tool and categorize them).

My tea collection, separated them by type in different cans (green, black, chamomile, fruity, etc).

Went through my clothes to decide anything I don’t wear anymore.

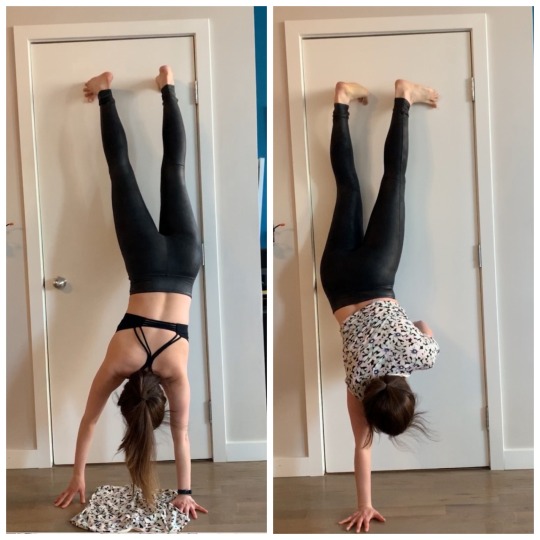

6- I’ve been doing some Instagram challenges like putting a t-shirt on while doing a handstand:

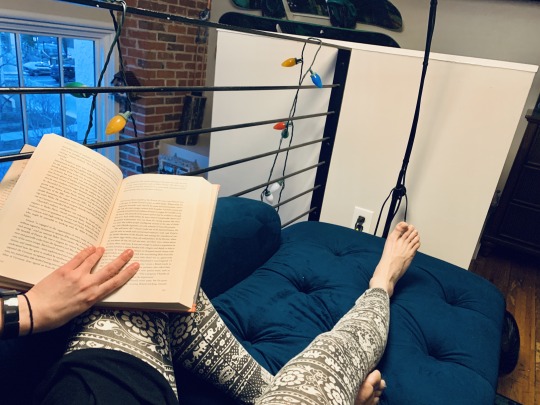

7- Online shopping hasn’t ended for me, eek! I mean, I had to get some comfy cute quarantine clothes like this one:

And also cute “Rachel Green” dress when things go back to normal, gotta be prepared ;)

Kevin has found new pastimes:

1. He dusted off his x-box and has been playing Grand Theft Auto – never seen him play before but he now plays a bit every day.

2. He made a delicious moist banana bread for the first time.

3. He’s gotten into every kind of home improvement project he could think of:

A. Pantry Upgrade:

A.1. He removed everything from the pantry.

A.2. Painted the pantry walls.

A.3. Bought new shelves and installed them.

B. Painted the windows.

C. Changed all the old electric plugs.

D. Currently upgrading our lights from the ceiling ** IN PROGRESS**

E. Done some intense cleaning!

E.1. Moved the refrigerator/WD/oven to clean under (SO DISGUSTING!)

E.2. He cleaned the oven with a power tool:

4- He cut his own hair!! I, on the other hand, made a hair salon appointment for May 12. Fingers crossed I can still make the appointment because this hair needs some work!

We order groceries to be delivered. And we obsessively clean the packages when they arrive. We also splurge once a week and order food from our neighborhood sushi, thai, pho, Greek or Venezuelan place (those are our go-to joints!). Gotta support our local restaurants!

I’ve been getting creative with my vegetarian meals:

Besides working out together, other activities we do together:

1. We play board games

Santorini has been a new favorite.

I even bought a new board game: Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Life.

Giant Jenga - Apparently Kevin has never lost in his life. Winning steak continues.

2. Watch a movie every other day. A few favorites so far:

JoJo Rabbit

Parasite

Molly’s Game

Knives Out

3. We have our rooftop to enjoy lunch and drinks with city and mountain views. We’ve recently discovered we can see Red Rocks Amphitheater from our rooftop. Might be the lack of industrial activities clearing up the air pollution.

4. Take many bubble baths.

5. Participate in #FormalFriday where we dress up, cook a fancier dinner and have cocktails.

6. Every night at 8pm we howl at the moon and hear the neighborhood play drums, trumpet, put out christmas lights. We pulled out our vuvuzela which I got in South Africa World Cup 2010.

Even though we are away from our friends and family, we’ve been staying connected quite often:

1. Do a weekly Happy Hour call with friends (pretty consistent with Kate and Rayelle) through GoogleChat and HouseParty app.

2. Do a weekly yoga class with Kevin’s friends.

3. We celebrated both our dad’s birthdays through Zoom and GoToMeeting. Their birthdays are 7 days apart (April 2, April 9).

4. I sent flowers to abuelita cause poor thing, she hasn’t seen anyone and needs more attention.

5. Emailed grandparents photos so they are up to date with what we are doing.

6. Mailed my brother a couple of books – one for Demi and one for him.

7. Mailed Kate her favorite popcorn (Kettle Head Popcorn Jalapeno Cheddar flavor).

8. Mailed Carla a 4-pack energy drink we used to drink in South Africa back in 2010. I randomly saw it on amazon and made me remember such a great time we had together. And thought it would brighten her day to remember our South Africa trip.

I’m not the only one that have been sending surprise packages. My family has been very sweet to me:

Parents have sent surprise Venezuelan treats in the mail

Grandpa sent me a book: American Dirt

When I do have to leave the house to run errands like drop off packages at UPS or USPS, I wear a “mask” (made out of a bandana) and wear gloves. Everyone around is wearing masks as well and staying far apart. Feels very doomsday.

Overall, things have been going well for us. That being said, we are extremely privileged to be able to do all these things. Unfortunately there are others that cannot work from home, have filed for unemployment, have lost their health insurance due to it or have kids in the house which makes it harder to work and homeschool their kids. Domestic violence has skyrocketed. There are families that cannot afford internet and their children cannot do their school work online. Single mothers who work multiple jobs cannot be at home to help their child with homework when school is expecting for parents to take over. There are older people that are struggling with the new technology changes and it’s giving them increased anxiety and stress to learn how to use online conferencing (I know it seems normal to most of us, others are really having a hard time). There are people with health issues that have increased anxiety of contracting COVID-19. Healthcare workers, grocery store workers, delivery services, waste management services, cleaning services... they are all putting their health at risk everyday to help us continue to live “normal” lives.

They are the true MVP.

Best thing we can do is to stay home, stay positive and find creative ways to have fun. Here is Kevin faceswap with a barbie:

1 note

·

View note

Link

Len Necefer, as told to Frederick Reimers | Longreads | August 2020 | 3,211 words (12 minutes)

It’s early March, the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic in the United States, and I-25 in downtown Albuquerque is nearly deserted at nine am on a Wednesday. It feels like a risky time for a road trip. After filling morgues in Italy, the virus is propagating across the globe and countries everywhere are closing their borders. No one seems sure exactly who transmits the disease or even how it is spread. Every day feels like living on a knife ridge. A light rain is falling and the signs hanging above the highway that normally display traffic times instead read: Stay Home, Save Lives.

I’m trying to save a life by dashing across five states. Driving eastward from Tucson, where I’m an assistant professor of at the University of Arizona, I’m bound for Lawrence, Kansas, where my 72-year old dad lives. He’d retired from teaching at Haskell Indian Nations University there four years ago, and has been living alone since. “I’ll be fine here,” he says, but when I ask him who can do his grocery shopping or who would take care of him if he were to fall ill, he can’t think of anyone. All his friends there have moved away or passed away. I can’t bear the thought of him riding out a pandemic alone if cities and states are locked down, and don’t really trust my older parent to take precautions against the virus. I’m going to get him.

I throw in some N95 masks and nitrile gloves I have from tinkering with the van engine, clean sheets for the van’s bed, and food to cook on the camp stove. I don’t want us eating in restaurants, and figure we can share the bed instead of risking a hotel. I notify my students that class, already moved online, is canceled for the week, and drive out of Tucson just before dark on a Tuesday.

* * *

The next morning as I’m driving through Albuquerque, I call my mom, who lives there with my stepdad Dan. I tell her that I am on my way to Kansas to bring dad back. “Was he open to the idea, or did you have to convince him?” she asks. My mom, who is Navajo, knows that like a lot of white guys of his age, Dad has trouble accepting help. He agreed to shelter with me for a couple months, I tell her, though I’m planning on him staying much longer. She invites us to stay with them on our way back through, and it’s good to think that at least right now, I’m within a few miles of her. This road trip has already gotten a little weird.

The night before, I’d driven until I was tired, past one a.m. I pulled off the highway to camp at a spot I knew in the open desert in western New Mexico–just a clearing in the saltbrush and sage flats off the side of a dirt road, earth packed down by the tires of successive car campers. I’d been surprised to see the broad white side of RV after RV appear in my headlights at each potential turnout. I had to drive a few extra miles to find a vacant spot. Other campers always make me uneasy when I’m pulling in late at night, and I really couldn’t understand what all these people were doing out here in the middle of the pandemic.

Their attitude towards the pandemic is, ‘It’ll work out,’ because for them, things always have.

Then in the morning, I’d been awakened by texts from friends in Salt Lake City, where there’d been a 5.7 magnitude earthquake. No one had been hurt, but the shaking had knocked the trumpet out of the golden hands of the Angel Moroni perched atop the highest spire of the principal Mormon temple; my friends noted wryly that the Latter-day Saints were counting on Moroni and his trumpet to herald the second coming.

Finally, two hours past Albuquerque, I pull off the highway to cook lunch at a place called Cuervo, New Mexico, that turns out to be a ghost town. Standing beside the van, waiting for the water to boil, I scan the crumbling husks of houses and a fenced off stone church. Thinking of The Road, Cormac McCarthy’s haunting novel about a father and son traveling together through abandoned towns after an unnamed apocalypse, I laugh to avoid thinking of this rest stop as an omen.

That afternoon, driving Highway 54 through the panhandles of Texas and Oklahoma, more cars began appearing. I’m surprised to see a bowling alley and then a restaurant with full parking lots. Somewhere in western Kansas, I pass a group of high school kids playing full-squad basketball. At a gas station, people look at me strangely as I operate the pump wearing my mask and gloves, and it is obvious the residents and I are listening to different news sources.

* * *

In Kansas, I pass signs pointing to Haskell County, which I recognize from a podcast I’ve been listening to about the 1918 flu pandemic. The Spanish Flu is believed to have originated in Haskell County where it jumped from pigs to humans before hitching a ride to Europe with some local kids who joined the army to fight in World War I, where it mutated into the deadly strain that eventually killed 50 million people worldwide. It’s ironic: that so much vitriol is already being directed at China and towards Asian Americans, when the biggest pandemic in modern history began just miles from here, in America’s heartland.

The 1918 pandemic also hit my people hard, taking as much as 24 percent percent of the Navajo population. It was a population just a little more than a generation removed from an even larger trauma — the Long Walk of the Navajo. In 1864, the U.S. Cavalry forced the Navajo from their homeland in North Arizona, New Mexico, and Southern Utah, and marched them 300 miles to Fort Sumner, New Mexico, in the winter, with only what they could carry. Hundreds died from starvation, hypothermia, or execution when they couldn’t keep up. By the time they left Sumner four years later, more than 2,000 had died. We are taught not to talk about Hwéeldi — “the place of suffering.” Normally when I drive to Kansas, I detour far around it, but in this case, it lay along the fastest route; I’d passed signs for it in the morning. Late that night, I pull into a campsite at Pratt Sandhills, a vestige of remaining tall grass prairie spread atop ancient sand dunes. The dirt road is a pair of parallel puddles from a recent storm and the van loses traction here and there. When I finally turn off the ignition, it’s a day I feel glad to let go of.

* * *

I make Lawrence the next afternoon, embracing my dad, Edward, on the walkway to the small house where I’d spent much of my youth. He has the easygoing demeanor of a good teacher: attentive, warm, a mischievous sense of humor. He grew up in Detroit in the 60s then joined the Peace Corps, teaching English and math in Liberia. Once home, he meandered through a series of jobs in the Bureau of Indian Education, and eventually got a gig teaching math at Haskell, where he met my mom.

“Have you thought about what you’ll bring to Tucson?” I ask.

“I’m all packed,” he says, and it’s a relief. I’d been worried we’d waste a few days wrangling over his belongings. But when we pull out of Lawrence in the morning, we’re in two vehicles, not just my van. He says it is because he doesn’t want to leave his car parked on the street while he is gone, but I’m sure he just isn’t ready to give up that independence. I’m frustrated because I know it will slow us down and leave us more exposed. It means more breaks — I assume he’s no longer capable of driving more than six hours at a shot — and more gas stops, since his Volkswagen GTI has less than half the range of my van.

At the first, just past Wichita, I say, “Let me gas up both cars, so we only have to use up one set of gloves.” He says “Okay,” but when I turn around after getting the second pump started, I see the back of him disappearing into the store.

We’d talked about staying out of buildings — paying at the pump, going to the bathroom behind a tree. Just a few hours in, and he’s already broken that. I stew angrily at the pumps waiting for him to return, trying to keep panic at bay. If I get upset, I think, he’s not going to hear anything I say.

“Dad, I thought we talked about this,” I say when he returns. “We have to make these decisions together. You have to take this seriously.”

“Fine,” he says. “Let’s talk about it. I can stay out of gas station restrooms, but I’m going to need to get a hotel tonight. My back is already stiff.”

I can’t budge him. “Okay,” I say, “but we’ll have to scrub it all down with Clorox wipes — every surface. Let’s try for the Kansas border,” I say. “The town of Liberal should have hotels. We’re exposed in Trump country, but at least we can take comfort in the name,” I joke.

A few hours later, I still feel we the need to lighten the mood, so during a stretch break beside the highway, I show Dad a few quarantine videos people are posting on Instagram — the sock puppet appearing to eat traffic on the street below, and people “rock climbing” across their apartments with ropes and harnesses. “We should make one,” I say. “How about ghostriding the whip?” I explain the concept of the meme, grooving to music alongside, or atop, a moving vehicle without anyone in the driver’s seat. I show him a few examples, and Dad is game. I crank up some music on the van stereo — the Snotty Nose Rez Kids — put the emergency brake on halfway, and put it in gear. Dad does the rest, strutting alongside the open door of the slowly moving van with his sunglasses on and his cap turned backwards under the bright blue Kansas sky, always happiest staying loose.

I post the video on Instagram with the caption, “My dad has ascended to the throne of Quaranking.”

View this post on Instagram

When the whip contaminated. My dad has ascended to the throne of Quaranking #quarantined #quarantine #quaranking #rona #corona #quaranteamchallenge Shoutout to my dad & @snottynoserezkids

A post shared by Dr. Len Necefer (@lennecefer) on Mar 20, 2020 at 3:45pm PDT

Except that he hasn’t. He won’t give up on the hotel idea. In Liberal, I manage to convince him to drink a can of cold-brew coffee from the van fridge and drive a little longer. Two hours later, at sunset, we gas up in Dalhart, Texas, and I propose we shoot for Tucumcari, New Mexico, an hour and a half further — and in a state where the governor has put some precautions in place. Ironically, when we get there, those precautions keep us from finding my dad a bed. Hotels are only allowed fifty percent occupancy, and there are no vacancies. At the fourth and last hotel we try, Dad holds the door open for a woman also entering the lobby and she gets the last room.

He is dejected and exhausted. Driving for 12 hours has taken its toll. We cook a pot of ramen in the parking lot, huddled inside the van against the windy night.

“What if we just sleep here in the van?” I ask.

“I need my own bed,” he says.

“I’ll sleep on the floor,” I say.

“I’m going to have to get up to pee in the night a few times,” he says, now irritated, “and I don’t want to disturb you.”

“It won’t,” I say, but he’s not having it.

We decide to try to push through the last 175 miles to Mom’s house, but after 100 of those, I can see Dad’s headlights dropping further back.

“How ya doing?” I ask over the phone.

“I probably need to stop,” he says, and we pull over at a rest area, just an hour from Albuquerque, to sleep till morning. There are a dozen others there doing the same, towels tucked into their windows for privacy. Dad sleeps in his car. I can’t talk him out of it.

* * *

We spend two nights recovering at my mom and stepdad’s house in Albuquerque, knowing Tucson is just a day’s drive away. They are all friends and Dad has stayed with them before; any tension is on my end. Over dinner, I’m surprised at how much Dan and Dad minimize the pandemic, and how they assume things will get quickly back to normal.

“Guys,” I say, “it’s gonna be at least 18 months before there’s a vaccine, and because of your age, you’re both in a high-risk demographic.” I never expected to be parenting my folks so soon. “In fact,” I say, “if something does happen, I’m probably going to be the one who makes all the arrangements. I should probably have copies of your wills.”

“Let’s not get carried away,” says Dan.

It comes to a head the next day. I’d watched Dan come home from the grocery store, toss his mask on the key rack, and settle in without washing his hands.

“Dan,” I say, “if you really care about my mom’s health, you have to take this seriously.” He assures me that he is, but I can tell I’ve pissed him off. Later, I have an aside with mom.

“I’m pretty frustrated with Dan,” she says, “and I can imagine you are frustrated with your father, too.” I tell her I really did need their last directives and will documents. “I’ll get that for you today,” she says, “and we can talk it through.”

It’s not surprising that my mom’s approach to the pandemic has been markedly different from my father and stepfather’s. Both of the men are white baby boomers, members of a generation who’d had the freedom to live exactly how they wanted. Their attitude towards the pandemic is, “It’ll work out,” because for them, things always have.

My mother was born in Red Valley, on the reservation near Shiprock, New Mexico. She grew up trailing her family’s sheep herd to high camp each spring and back again in the fall. It was the same journey that my great-grandparents made twice a year, and the same one that my cousins and I tagged along on as kids, walking alongside the herding dogs, and running into roadside stores to buy candy with cash my grandfather or uncle would slip us.

Kickstart your weekend reading by getting the week’s best Longreads delivered to your inbox every Friday afternoon.

Sign up

Mom’s family have always been planners. It comes from migrating with the sheep, and from the cultural trauma of the Long Walk. In the summer of 1864, life was as it had been in Navajo country for hundreds of years. Then, in September, Kit Carson burned the crops, and in January an entire people were being force-marched across New Mexico. “You know, when society collapses, we need to be prepared,” I’d hear my grandfather say.

I’ve inherited that affinity for being prepared. I took my education all the way to a Ph.D., fulfilling the idea that it’s better to be overqualified for a job. I take pains to cultivate my relationships, knowing it leads to more social resilience. Before I drove to Kansas, realizing I hadn’t met all my neighbors yet and that such connections might be critical in the coming months, I knocked on every door to introduce myself and left notes at the doors no one opened. Even my van, fully outfitted for camping adventures, is subconsciously a backup home.

Which is why it is frustrating, and even a little scary, to watch my father resist my guidance. I’m sure it’s how a parent feels watching their teenage children make brash choices in a bid to establish their independence. I realize that all I can do is continue to offer support, and to remain patient myself. Which isn’t all that hard when you love someone, I realize that night as the four of us sit around the kitchen table sipping on whiskey and enjoying each other’s company.

* * *

On the last day we get on the road early, and with just seven hours drive to Tucson, I feel relaxed. When we stop for lunch, I can’t find the utensils to spread the peanut butter — Dad had stashed them somewhere after our parking lot dinner nadir — so I use a 19 millimeter wrench. If I were Cormac McCarthy this is the kind of thing I’d put in my post-apocalypse book, I think.

I’m excited to get home. “Maybe you should look at this quarantine as a trial run for moving to Tucson full-time,” I’d suggested to Dad the night before, glad that he seemed open to the idea. It should be a pretty easy sell — few places compare to southern Arizona in March, with mild temps and the Sonoran desert in bloom. Then fittingly, just around Wilcox, I see that the entire desert is carpeted with yellow and orange fiveneedle pricklyleaf. Clumps of the daisy-like flowers have erupted from the desert in a superbloom, spreading for miles across the basin southwards towards the blue ramparts of the Chiricahua and Dragoon ranges, storied strongholds of the Apache people who were some of the last Native Americans to resist white settlement. I pull off the highway, and Dad pulls in behind me. “Let’s take a little walk,” I say.

“Let’s keep going,” he says. “We’re only an hour away.”

I realized he isn’t seeing the flowers. “Dad, take off your sunglasses and look out there,” I say.

He lifts them up, looks around, and just says, “Oh.”

View this post on Instagram

Pretty unreal welcome to the Sonoran Desert. Full desert bloom of Fiveneedle Pricklyleaf (Thymophylla pentachaeta)

A post shared by Dr. Len Necefer (@lennecefer) on Mar 22, 2020 at 8:03pm PDT

We walk out among the flowers on a faint gravel road, taking in the blooms and the tiers of mountains reaching southward clear to the Mexico border. We wander, just breathing and releasing the tension of driving. “How long do they last?” Dad asks.

“Only a week,” I say. “We’re lucky to be here.”

* * *

The next months are bittersweet. Dad loves Tucson’s ample cycling opportunities and is a good houseguest. Wary of culinary skills atrophied by two decades of bachelorhood, I do most of the cooking, though he does help pack the van for my next road trip. By May, Covid-19 has torn through my Navajo Nation homeland, inflicting the highest per-capita infection rate in the United States thanks to underfunded health resources and food deserts that have increased health risk factors. A Natives Outdoors fundraiser provides masks and hand sanitizers to communities on the reservation, which a friend and I make two separate trips to deliver.

By the time we return from the second, Dad has decided to move to Tucson for good. We’ve found a place for him to rent and a moving company to pack up his house in Kansas. I’m pleased of course, but also sad that our time living together again will soon be over. We’ve bonded over these strange quarantine times, but there’s also a real feeling of accomplishment to having successfully adapted our lives to each other. Multigenerational living is becoming rare — it challenges the supremacy of freedom and convenience, but in that we also lose something, additional layers and complexity to our most foundational relationships.

* * *

Len Necefer is an assistant professor at the University of Arizona. His writing and photography have been featured in the Alpinist, Outside, Beside magazine, and more.

Frederick Reimers is based in Jackson, Wyoming, and contributes to Outside, Bloomberg, Men’s Journal, Ski, Powder, and Adventure Journal magazines. Follow him at @writereimers.

Editor: Michelle Weber

Factchecker: Julie Schwietert Collazo

0 notes

Text

Notes for a Post-apocalyptic Novel

https://ift.tt/eA8V8J

Len Necefer, as told to Frederick Reimers | Longreads | August 2020 | 3,211 words (12 minutes)

It’s early March, the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic in the United States, and I-25 in downtown Albuquerque is nearly deserted at 9 a.m. on a Wednesday. It feels like a risky time for a road trip. After filling morgues in Italy, the virus is propagating across the globe and countries everywhere are closing their borders. No one seems sure exactly who transmits the disease or even how it is spread. Every day feels like living on a knife ridge. A light rain is falling and the signs hanging above the highway that normally display traffic times instead read: Stay Home, Save Lives.

I’m trying to save a life by dashing across five states. Driving eastward from Tucson, where I’m an assistant professor at the University of Arizona, I’m bound for Lawrence, Kansas, where my 72-year-old dad lives. He’d retired from teaching at Haskell Indian Nations University there four years ago, and has been living alone since. “I’ll be fine here,” he says, but when I ask him who can do his grocery shopping or who would take care of him if he were to fall ill, he can’t think of anyone. All his friends there have moved away or passed away. I can’t bear the thought of him riding out a pandemic alone if cities and states are locked down, and don’t really trust my older parent to take precautions against the virus. I’m going to get him.

I throw in some N95 masks and nitrile gloves I have from tinkering with the van engine, clean sheets for the van’s bed, and food to cook on the camp stove. I don’t want us eating in restaurants, and figure we can share the bed instead of risking a hotel. I notify my students that class, already moved online, is canceled for the week, and drive out of Tucson just before dark on a Tuesday.

* * *

The next morning as I’m driving through Albuquerque, I call my mom, who lives there with my stepdad Dan. I tell her that I am on my way to Kansas to bring dad back. “Was he open to the idea, or did you have to convince him?” she asks. My mom, who is Navajo, knows that like a lot of white guys of his age, Dad has trouble accepting help. He agreed to shelter with me for a couple months, I tell her, though I’m planning on him staying much longer. She invites us to stay with them on our way back through, and it’s good to think that at least right now, I’m within a few miles of her. This road trip has already gotten a little weird.

The night before, I’d driven until I was tired, past one a.m. I pulled off the highway to camp at a spot I knew in the open desert in western New Mexico — just a clearing in the saltbrush and sage flats off the side of a dirt road, earth packed down by the tires of successive car campers. I’d been surprised to see the broad white side of RV after RV appear in my headlights at each potential turnout. I had to drive a few extra miles to find a vacant spot. Other campers always make me uneasy when I’m pulling in late at night, and I really couldn’t understand what all these people were doing out here in the middle of the pandemic.

Their attitude towards the pandemic is, ‘It’ll work out,’ because for them, things always have.

Then in the morning, I’d been awakened by texts from friends in Salt Lake City, where there’d been a 5.7 magnitude earthquake. No one had been hurt, but the shaking had knocked the trumpet out of the golden hands of the Angel Moroni perched atop the highest spire of the principal Mormon temple; my friends noted wryly that the Latter-day Saints were counting on Moroni and his trumpet to herald the second coming.

Finally, two hours past Albuquerque, I pull off the highway to cook lunch at a place called Cuervo, New Mexico, that turns out to be a ghost town. Standing beside the van, waiting for the water to boil, I scan the crumbling husks of houses and a fenced-off stone church. Thinking of The Road, Cormac McCarthy’s haunting novel about a father and son traveling together through abandoned towns after an unnamed apocalypse, I laugh to avoid thinking of this rest stop as an omen.

That afternoon, driving Highway 54 through the panhandles of Texas and Oklahoma, more cars began appearing. I’m surprised to see a bowling alley and then a restaurant with full parking lots. Somewhere in western Kansas, I pass a group of high school kids playing full-squad basketball. At a gas station, people look at me strangely as I operate the pump wearing my mask and gloves, and it is obvious the residents and I are listening to different news sources.

* * *

In Kansas, I pass signs pointing to Haskell County, which I recognize from a podcast I’ve been listening to about the 1918 flu pandemic. The Spanish Flu is believed to have originated in Haskell County where it jumped from pigs to humans before hitching a ride to Europe with some local kids who joined the army to fight in World War I, where it mutated into the deadly strain that eventually killed 50 million people worldwide. It’s ironic: that so much vitriol is already being directed at China and towards Asian Americans, when the biggest pandemic in modern history began just miles from here, in America’s heartland.

The 1918 pandemic also hit my people hard, taking as much as 24 percent percent of the Navajo population. It was a population just a little more than a generation removed from an even larger trauma — the Long Walk of the Navajo. In 1864, the U.S. Cavalry forced the Navajo from their homeland in North Arizona, New Mexico, and Southern Utah, and marched them 300 miles to Fort Sumner, New Mexico, in the winter, with only what they could carry. Hundreds died from starvation, hypothermia, or execution when they couldn’t keep up. By the time they left Sumner four years later, more than 2,000 had died. We are taught not to talk about Hwéeldi — “the place of suffering.” Normally when I drive to Kansas, I detour far around it, but in this case, it lay along the fastest route; I’d passed signs for it in the morning. Late that night, I pull into a campsite at Pratt Sandhills, a vestige of remaining tall grass prairie spread atop ancient sand dunes. The dirt road is a pair of parallel puddles from a recent storm and the van loses traction here and there. When I finally turn off the ignition, it’s a day I feel glad to let go of.

* * *

I make Lawrence the next afternoon, embracing my dad, Edward, on the walkway to the small house where I’d spent much of my youth. He has the easygoing demeanor of a good teacher: attentive, warm, a mischievous sense of humor. He grew up in Detroit in the ’60s then joined the Peace Corps, teaching English and math in Liberia. Once home, he meandered through a series of jobs in the Bureau of Indian Education, and eventually got a gig teaching math at Haskell, where he met my mom.

“Have you thought about what you’ll bring to Tucson?” I ask.

“I’m all packed,” he says, and it’s a relief. I’d been worried we’d waste a few days wrangling over his belongings. But when we pull out of Lawrence in the morning, we’re in two vehicles, not just my van. He says it is because he doesn’t want to leave his car parked on the street while he is gone, but I’m sure he just isn’t ready to give up that independence. I’m frustrated because I know it will slow us down and leave us more exposed. It means more breaks — I assume he’s no longer capable of driving more than six hours at a shot — and more gas stops, since his Volkswagen GTI has less than half the range of my van.

At the first, just past Wichita, I say, “Let me gas up both cars, so we only have to use up one set of gloves.” He says “Okay,” but when I turn around after getting the second pump started, I see the back of him disappearing into the store.

We’d talked about staying out of buildings — paying at the pump, going to the bathroom behind a tree. Just a few hours in, and he’s already broken that. I stew angrily at the pumps waiting for him to return, trying to keep panic at bay. If I get upset, I think, he’s not going to hear anything I say.

“Dad, I thought we talked about this,” I say when he returns. “We have to make these decisions together. You have to take this seriously.”

“Fine,” he says. “Let’s talk about it. I can stay out of gas station restrooms, but I’m going to need to get a hotel tonight. My back is already stiff.”

I can’t budge him. “Okay,” I say, “but we’ll have to scrub it all down with Clorox wipes — every surface. Let’s try for the Kansas border,” I say. “The town of Liberal should have hotels. We’re exposed in Trump country, but at least we can take comfort in the name,” I joke.

A few hours later, I still feel we the need to lighten the mood, so during a stretch break beside the highway, I show Dad a few quarantine videos people are posting on Instagram — the sock puppet appearing to eat traffic on the street below, and people “rock climbing” across their apartments with ropes and harnesses. “We should make one,” I say. “How about ghostriding the whip?” I explain the concept of the meme, grooving to music alongside, or atop, a moving vehicle without anyone in the driver’s seat. I show him a few examples, and Dad is game. I crank up some music on the van stereo — the Snotty Nose Rez Kids — put the emergency brake on halfway, and put it in gear. Dad does the rest, strutting alongside the open door of the slowly moving van with his sunglasses on and his cap turned backwards under the bright blue Kansas sky, always happiest staying loose.

I post the video on Instagram with the caption, “My dad has ascended to the throne of Quaranking.”

View this post on Instagram

When the whip contaminated. My dad has ascended to the throne of Quaranking #quarantined #quarantine #quaranking #rona #corona #quaranteamchallenge Shoutout to my dad & @snottynoserezkids

A post shared by Dr. Len Necefer (@lennecefer) on Mar 20, 2020 at 3:45pm PDT

Except that he hasn’t. He won’t give up on the hotel idea. In Liberal, I manage to convince him to drink a can of cold-brew coffee from the van fridge and drive a little longer. Two hours later, at sunset, we gas up in Dalhart, Texas, and I propose we shoot for Tucumcari, New Mexico, an hour and a half further — and in a state where the governor has put some precautions in place. Ironically, when we get there, those precautions keep us from finding my dad a bed. Hotels are only allowed fifty percent occupancy, and there are no vacancies. At the fourth and last hotel we try, Dad holds the door open for a woman also entering the lobby and she gets the last room.

He is dejected and exhausted. Driving for 12 hours has taken its toll. We cook a pot of ramen in the parking lot, huddled inside the van against the windy night.

“What if we just sleep here in the van?” I ask.

“I need my own bed,” he says.

“I’ll sleep on the floor,” I say.

“I’m going to have to get up to pee in the night a few times,” he says, now irritated, “and I don’t want to disturb you.”

“It won’t,” I say, but he’s not having it.

We decide to try to push through the last 175 miles to Mom’s house, but after 100 of those, I can see Dad’s headlights dropping further back.

“How ya doing?” I ask over the phone.

“I probably need to stop,” he says, and we pull over at a rest area, just an hour from Albuquerque, to sleep till morning. There are a dozen others there doing the same, towels tucked into their windows for privacy. Dad sleeps in his car. I can’t talk him out of it.

* * *

We spend two nights recovering at my mom and stepdad’s house in Albuquerque, knowing Tucson is just a day’s drive away. They are all friends and Dad has stayed with them before; any tension is on my end. Over dinner, I’m surprised at how much Dan and Dad minimize the pandemic, and how they assume things will get quickly back to normal.

“Guys,” I say, “it’s gonna be at least 18 months before there’s a vaccine, and because of your age, you’re both in a high-risk demographic.” I never expected to be parenting my folks so soon. “In fact,” I say, “if something does happen, I’m probably going to be the one who makes all the arrangements. I should probably have copies of your wills.”

“Let’s not get carried away,” says Dan.

It comes to a head the next day. I’d watched Dan come home from the grocery store, toss his mask on the key rack, and settle in without washing his hands.

“Dan,” I say, “if you really care about my mom’s health, you have to take this seriously.” He assures me that he is, but I can tell I’ve pissed him off. Later, I have an aside with mom.

“I’m pretty frustrated with Dan,” she says, “and I can imagine you are frustrated with your father, too.” I tell her I really did need their last directives and will documents. “I’ll get that for you today,” she says, “and we can talk it through.”

It’s not surprising that my mom’s approach to the pandemic has been markedly different from my father and stepfather’s. Both of the men are white baby boomers, members of a generation who’d had the freedom to live exactly how they wanted. Their attitude towards the pandemic is, “It’ll work out,” because for them, things always have.

My mother was born in Red Valley, on the reservation near Shiprock, New Mexico. She grew up trailing her family’s sheep herd to high camp each spring and back again in the fall. It was the same journey that my great-grandparents made twice a year, and the same one that my cousins and I tagged along on as kids, walking alongside the herding dogs, and running into roadside stores to buy candy with cash my grandfather or uncle would slip us.

Kickstart your weekend reading by getting the week’s best Longreads delivered to your inbox every Friday afternoon.

Sign up

Mom’s family have always been planners. It comes from migrating with the sheep, and from the cultural trauma of the Long Walk. In the summer of 1864, life was as it had been in Navajo country for hundreds of years. Then, in September, Kit Carson burned the crops, and in January an entire people were being force-marched across New Mexico. “You know, when society collapses, we need to be prepared,” I’d hear my grandfather say.

I’ve inherited that affinity for being prepared. I took my education all the way to a Ph.D., fulfilling the idea that it’s better to be overqualified for a job. I take pains to cultivate my relationships, knowing it leads to more social resilience. Before I drove to Kansas, realizing I hadn’t met all my neighbors yet and that such connections might be critical in the coming months, I knocked on every door to introduce myself and left notes at the doors no one opened. Even my van, fully outfitted for camping adventures, is subconsciously a backup home.

Which is why it is frustrating, and even a little scary, to watch my father resist my guidance. I’m sure it’s how a parent feels watching their teenage children make brash choices in a bid to establish their independence. I realize that all I can do is continue to offer support, and to remain patient myself. Which isn’t all that hard when you love someone, I realize that night as the four of us sit around the kitchen table sipping on whiskey and enjoying each other’s company.

* * *

On the last day we get on the road early, and with just a seven-hour drive to Tucson, I feel relaxed. When we stop for lunch, I can’t find the utensils to spread the peanut butter — Dad had stashed them somewhere after our parking lot dinner nadir — so I use a 19 millimeter wrench. If I were Cormac McCarthy this is the kind of thing I’d put in my post-apocalypse book, I think.

I’m excited to get home. “Maybe you should look at this quarantine as a trial run for moving to Tucson full-time,” I’d suggested to Dad the night before, glad that he seemed open to the idea. It should be a pretty easy sell — few places compare to southern Arizona in March, with mild temps and the Sonoran desert in bloom. Then fittingly, just around Wilcox, I see that the entire desert is carpeted with yellow and orange fiveneedle pricklyleaf. Clumps of the daisy-like flowers have erupted from the desert in a superbloom, spreading for miles across the basin southwards towards the blue ramparts of the Chiricahua and Dragoon ranges, storied strongholds of the Apache people who were some of the last Native Americans to resist white settlement. I pull off the highway, and Dad pulls in behind me. “Let’s take a little walk,” I say.

“Let’s keep going,” he says. “We’re only an hour away.”

I realized he isn’t seeing the flowers. “Dad, take off your sunglasses and look out there,” I say.

He lifts them up, looks around, and just says, “Oh.”

View this post on Instagram

Pretty unreal welcome to the Sonoran Desert. Full desert bloom of Fiveneedle Pricklyleaf (Thymophylla pentachaeta)

A post shared by Dr. Len Necefer (@lennecefer) on Mar 22, 2020 at 8:03pm PDT

We walk out among the flowers on a faint gravel road, taking in the blooms and the tiers of mountains reaching southward clear to the Mexico border. We wander, just breathing and releasing the tension of driving. “How long do they last?” Dad asks.

“Only a week,” I say. “We’re lucky to be here.”

* * *

The next months are bittersweet. Dad loves Tucson’s ample cycling opportunities and is a good houseguest. Wary of culinary skills atrophied by two decades of bachelorhood, I do most of the cooking, though he does help pack the van for my next road trip. By May, Covid-19 has torn through my Navajo Nation homeland, inflicting the highest per-capita infection rate in the United States thanks to underfunded health resources and food deserts that have increased health risk factors. A Natives Outdoors fundraiser provides masks and hand sanitizers to communities on the reservation, which a friend and I make two separate trips to deliver.

By the time we return from the second, Dad has decided to move to Tucson for good. We’ve found a place for him to rent and a moving company to pack up his house in Kansas. I’m pleased of course, but also sad that our time living together again will soon be over. We’ve bonded over these strange quarantine times, but there’s also a real feeling of accomplishment to having successfully adapted our lives to each other. Multigenerational living is becoming rare — it challenges the supremacy of freedom and convenience, but in that we also lose something, additional layers and complexity to our most foundational relationships.

* * *

Len Necefer is an assistant professor at the University of Arizona. His writing and photography have been featured in the Alpinist, Outside, Beside magazine, and more.

Frederick Reimers is based in Jackson, Wyoming, and contributes to Outside, Bloomberg, Men’s Journal, Ski, Powder, and Adventure Journal magazines. Follow him at @writereimers.

Editor: Michelle Weber

Factchecker: Julie Schwietert Collazo

https://ift.tt/2XLnfCT

from Blogger https://ift.tt/2PsWhLG

0 notes

Text

Let the flood gates begin

This post may contain affiliate links, which means that if you click on one of the product links within the post, I may receive a commission for your click and purchase. You do not have to make a purchase to enjoy this post, I only highlight products to help with the cost of running the blog, and I only post links to products relevant to the topic in that post and to companies I use and trust.”

Please Note: I started writing this blogpost in pen and paper. You know, the old-fashioned way of writing. I got the idea from an episode from Star Trek: Voyager where one of my favorite captains, Captain Janeway was sick of technology, after dealing with species 842 and the Borg. This was the episode that introduced Jeri Ryan as Seven of Nine, a former Borg drone brought back by to her human self by The doctor, authorized by Captain Janeway. Captain Janeway decided to take to writing her captain’s log by this method. It is a practice that we should all do in the wake of this pandemic. To me, even though you are seeing my post in digital form, it was a way of getting back to things in a natural way.

Photo by Pixabay

This was the week when my city reopened for retail. Today was the day I ventured out to a new norm of new rules (other than what was already in place). As I drove, doing my errands of depositing money in my business checking account and going to a grocery store that carried a Starbucks kiosk, because the Starbucks down the street lied about being open, I was thinking, “was it all worth being quarantined for the past 2 ½ months?” The only difference was Columbus, Ohio all of sudden looked like a Japanese prefecture, with mask-wearing people out and about in the 70° plus weather. This is something that the Japanese and other Asians are used to doing, not Americans.

Americans are used to having the freedom to do whatever we want to do, and how we want to do it. If it puts us in jail, so be it. When we get out, some of us will try it again until someone ignores us, then it becomes a norm. If we have to protest, that is fine, it makes an interesting news story locally and/or nationally.

I am not sure how I feel about it.

OK, let me explain….

Since this whole Covid-19 started, I have been squeamish about a few things and those are:

What is my new norm?

How is the country supposed to work now that there is the new little bug that can wipe us out, especially in places like the city where I live and places that I love, like the Caribbean and Walt Disney World.

What is my new norm?

I have been a quiet person all my life. I get it from my mom. So, I do not mind being isolated during this time period. My only problem at first was wearing the mask and gloves, and I get it. I had no problem putting them on, the problem comes because my hands are the same size as a child. There are people who cannot be around others because of their immune system and they are the elderly and the young. I have 6 people I have to respect that. My parents and aunt all have pre-existing conditions and they are elderly. I have a niece who will be 3 months old next week, I have a friend who also has a pre-existing condition and a pastor who has a pre-existing condition. I also have to watch it because I have high blood pressure and I am pre-diabetic. Depending on the doctor, I either have diabetics, or it can come at any time. Either way, I have to watch my diet and my weight. Thank you, Corona for giving me the sense of ignoring those two things. I am much better at doing that now.

Also my new norm: My business. I could tell you that I have the easiest job I could ever have, but like most businesses, there is the struggle of getting gigs. There is a struggle of getting money for this business. I also could say that I like the stimulus package for small or even home businesses. I do not have a small business, I have a home business, and as a home business owner, we often get lumped in with small businesses. What Is a home business? It is a business that is operated out of the home and if you do have any employees, it is usually an assistant. Your revenue is lower than a small business. A good year is when a person is able to earn $1,000 plus per month.

Why offer help to small businesses if big businesses get approved?

Well, to be honest, the EIDLE and the PPP portion of the first stimulus package has done nothing for me and my business because of companies like Potbelly and The Lakers basketball team, who should not have been allowed to apply in the first place, nor their applications should never been approved. Potbelly has returned the money and I believe so has The Lakers. That still does not help P. Lynne Designs. I applied twice. The first application was on Go Alice, while the second application was on the SBA.gov site. I have not heard back, and I doubt I will at this point. I do not have any employees. This is just to maintain the business of one, and for growth. The government did not handle this process very well. I chucked as “I am getting no help as usual” and went about my day. Update: Last night, I was able to file for unemployment, a right that was not given to people like freelance writers and freelance graphic designers, which I am. I pray and hope they approve it.

So let us go back to what I was talking about

THE RETAIL STORES

I do not mind the retail stores being open. Personally, I will not be going in the very beginning. Actually, I am having fun online ordering. I do not have to worry about donning on a mask, fighting crowds, not finding what I want. In fact, I ordered a mystery Die cut bag from Tonic Studios at 3 am this morning. That is how much fun I am having to order online. Yes, I can always order online, then pick up at the store like Walmart.

Amazon has been my store of the hour, and ever since I was told by my governor that even pickup was impossible in the craft stores in my state, I said “okay”, and started ordering online. Ordering online is natural for me anyway, so it did not bother me that I could not go to any of my stores, except Ikea. That is another story for another day.

I have been to two grocery stores since lockdown. One was for last-minute stuff as I found out just today that the second store only allows me to do pickup ordering if the order was over $30. The reason: Cat food. Well my nephew came through with the cat food, so now I do not have to buy that.

It is best if all stores keep in mind a level of safety. My feeling is this since I do have pre-existing conditions, as well as my parents, I do not want to spread the super germs. I am calling Corona that until we find a vaccination for it

My hardest hit yet, Walt Disney World

I am having the hardest time with a Disney Vacation. Last May, I booked a stay for 12 at The Bay Lake Towers at The Contemporary Resort (its official name) for the time of December 15-20, 2019, with all the bells and whistles as this might be the last vacation with my parents, who are in their 80s.

This was a well-meaning trip as two things went wrong from the start: how to pay for a $30,627.00 trip that included a 3-bedroom villa, tickets to the parks, and a deluxe dining plan, and how to tell a Disney-hating father that we were going to the “land of the mouse” times 4 (The Magic Kingdom, Epcot, Disney’s Hollywood Studios, and The Animal Kingdom theme parks). It would not be a requirement for my parents to go into the parks unless they wanted to. In years past (1998, 2004, and Disneyland in 2007 respectively), my father stayed at the resort or drove around the property, Orlando, and surrounding cities (Cape Canaveral, Kissimmee, and Tampa are close by). This time, my mom, who loves the parks will join him if she wants to. She is not too keen on using a riding scooter.

We were going to drive down instead of flying. We were coming back home that Sunday so that my siblings and my nephew and niece can get back to work by that Monday before Christmas. The kids (Nephews (age 12 and 9) and niece (11)) was being pulled out of school. Ohio has a funny winter break schedule where they are out either the day before Christmas eve or a couple of days before Christmas. Either way, it would have been fun. I pulled the plug on that trip on October 15th, one month before our last cancelation date of November 15th. I did not cry because I was going to call them the day after Christmas with a new date of December 12-19, 2020.

Well with Ms. ‘Rona on the prowl, and for the first time ever since Walt Disney opened Disneyland in 1955, all the parks were close, due her not wanting to play fair, I decided to see what Disney is going to do with the guidelines that they and the State of Florida government, as well as the federal government, was going to say about a reopening date. For the moment, Disney reopened Shanghai Disneyland Monday, Disney Springs, Walt Disney World’s shopping area is reopening on May 20th, and Walt Disney World is excepting bookings starting July 1 (it has been delayed from June 1st).

I do not want a vacation in 2020. I feel like it is too soon to book a vacation and go in 2020. So, I have decided to wait until December 15-19, 2021 to take the trip. This all depends on two things: the health of my parents and the health of our savings. There is one more factor and I am not depending on whether I do or do not do for this vacation and that is to get another Disney Vacation Club membership. This will affect how we pay for this trip. Naturally, this membership is a timeshare, and I have spoken about timeshares before on this blog. That is a talk for my yet to be created a new blog, which will be Disney-related. I took all the travel stuff off of my blog, Home Prep because it is not related.

Some good has come out of all this…

My stories are not all bad, in fact, some of them quite funny.

Last week, a friend had a birthday. She announces it each year 6 days in advance. This year was no different. What I love about Facebook is the ability to have people donate to your favorite charity in loo of presents for your birthday. I am going to do one, I am not sure where yet. July 21 has not gotten here yet.

Anyway, her sister and mother thought that since Ms. ‘Rona decided to cancel my friend’s plans, a surprise drive-by birthday salute was in order. Can I tell you that I do not know how to do one, LOL?

First, I told her mother that I was coming by via Facebook invite. I have seen lineups, so I thought that I was going to meet at her mother’s house, and we would fall in line to go to my friend’s apartment. After all, it was a surprise. Since I am one of those people who would show up late to her own wedding if given a chance, I decided to arrive early so my friend’s mother cannot say that I was late. So, I drove to the house at 4:46 and I did not see any cars. “Good, I am the first one,” I thought, so I went the next street over to turn around. Okay, next thing I knew, I saw my friend’s daughter, who is 3, then my friend. I thought, “Oh, Crap”, and I drove off to my parent’s house who live around the corner. This drive-by was at 5, so I killed some time at my parent’s house and went back over there. It turned out to be an “individual” happy birthday, as my friend and her mother sat there while people drove by, wishing her a happy birthday. It turned out great, and this goofy person now know the proper drive by, LOL.

Business Dealings….

I was able to get some things done for my business while on lockdown. I was approved for an affiliate that I have been wanting since 2017. You know how much I love Erin Condren products, so you will be seeing more affiliate links from that company. As always, I only support companies that I love and believe in, and you are not obligated to make a purchase, but it would be nice for the support. It is a way to put money back into my business. Some of these companies with affiliates, like Erin Condren, Cricut, and Amazon may have links that will help you save money as well. So in that case, if you need the product, it is good to help out a blog and save money at the same time.

I am also working on some things that will help improve this blog, including the infamous blog move.

Even though I was down and out during this period of time, I am fine now and living a new norm. For the moment, my state is wrapping being on lockdown. This is the reason for this title. Let the flood gates open!!! Well, I am over my limit. Be well and safe. Wear a mask, and I will talk to you later.

from Blogger https://bit.ly/3g08hQU

via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

Notes for a Post-apocalyptic Novel

Len Necefer, as told to Frederick Reimers | Longreads | August 2020 | 3,211 words (12 minutes)

It’s early March, the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic in the United States, and I-25 in downtown Albuquerque is nearly deserted at nine am on a Wednesday. It feels like a risky time for a road trip. After filling morgues in Italy, the virus is propagating across the globe and countries everywhere are closing their borders. No one seems sure exactly who transmits the disease or even how it is spread. Every day feels like living on a knife ridge. A light rain is falling and the signs hanging above the highway that normally display traffic times instead read: Stay Home, Save Lives.

I’m trying to save a life by dashing across five states. Driving eastward from Tucson, where I’m an assistant professor of at the University of Arizona, I’m bound for Lawrence, Kansas, where my 72-year old dad lives. He’d retired from teaching at Haskell Indian Nations University there four years ago, and has been living alone since. “I’ll be fine here,” he says, but when I ask him who can do his grocery shopping or who would take care of him if he were to fall ill, he can’t think of anyone. All his friends there have moved away or passed away. I can’t bear the thought of him riding out a pandemic alone if cities and states are locked down, and don’t really trust my older parent to take precautions against the virus. I’m going to get him.

I throw in some N95 masks and nitrile gloves I have from tinkering with the van engine, clean sheets for the van’s bed, and food to cook on the camp stove. I don’t want us eating in restaurants, and figure we can share the bed instead of risking a hotel. I notify my students that class, already moved online, is canceled for the week, and drive out of Tucson just before dark on a Tuesday.

* * *

The next morning as I’m driving through Albuquerque, I call my mom, who lives there with my stepdad Dan. I tell her that I am on my way to Kansas to bring dad back. “Was he open to the idea, or did you have to convince him?” she asks. My mom, who is Navajo, knows that like a lot of white guys of his age, Dad has trouble accepting help. He agreed to shelter with me for a couple months, I tell her, though I’m planning on him staying much longer. She invites us to stay with them on our way back through, and it’s good to think that at least right now, I’m within a few miles of her. This road trip has already gotten a little weird.

The night before, I’d driven until I was tired, past one a.m. I pulled off the highway to camp at a spot I knew in the open desert in western New Mexico–just a clearing in the saltbrush and sage flats off the side of a dirt road, earth packed down by the tires of successive car campers. I’d been surprised to see the broad white side of RV after RV appear in my headlights at each potential turnout. I had to drive a few extra miles to find a vacant spot. Other campers always make me uneasy when I’m pulling in late at night, and I really couldn’t understand what all these people were doing out here in the middle of the pandemic.

Their attitude towards the pandemic is, ‘It’ll work out,’ because for them, things always have.

Then in the morning, I’d been awakened by texts from friends in Salt Lake City, where there’d been a 5.7 magnitude earthquake. No one had been hurt, but the shaking had knocked the trumpet out of the golden hands of the Angel Moroni perched atop the highest spire of the principal Mormon temple; my friends noted wryly that the Latter-day Saints were counting on Moroni and his trumpet to herald the second coming.

Finally, two hours past Albuquerque, I pull off the highway to cook lunch at a place called Cuervo, New Mexico, that turns out to be a ghost town. Standing beside the van, waiting for the water to boil, I scan the crumbling husks of houses and a fenced off stone church. Thinking of The Road, Cormac McCarthy’s haunting novel about a father and son traveling together through abandoned towns after an unnamed apocalypse, I laugh to avoid thinking of this rest stop as an omen.

That afternoon, driving Highway 54 through the panhandles of Texas and Oklahoma, more cars began appearing. I’m surprised to see a bowling alley and then a restaurant with full parking lots. Somewhere in western Kansas, I pass a group of high school kids playing full-squad basketball. At a gas station, people look at me strangely as I operate the pump wearing my mask and gloves, and it is obvious the residents and I are listening to different news sources.

* * *