#and its so embedded in the history of early cinema

Text

one thing about me is i am obbsessed with the history of i love lucy

#desi and lucy (individually and together) have such an interesting story#and its so embedded in the history of early cinema#from vaudville influences to the communist trials#it somehow reflects a specific moment in time while also being so ahead of its time#and actually began a lot of tv practices still used today like reruns and live studio audience

1 note

·

View note

Text

Real Dinosaurs Versus Reel Dinosaurs: Film’s Fictionalization of the Prehistoric World

by Shelby Wyzykowski

What better way can you spend a quiet evening at home than by having a good old-fashioned movie night? You dim the lights, cozily snuggle up on your sofa with a bowl of hot, buttery popcorn, and pick out a movie that you’ve always wanted to see: the 1948 classic Unknown Island. Mindlessly munching away on your snacks, your eyes are glued to the screen as the story unfolds. You reach a key scene in the movie: a towering, T. rex-sized Ceratosaurus and an equally enormous Megatherium ground sloth are locked in mortal combat. And you think to yourself, “I’m pretty sure something like this never actually happened.” And you know what? Your prehistorically inclined instincts are correct.

From the time that the first dinosaur fossils were identified in the early 1800s, society has been fascinated by these “terrible lizards.” When, where, and how did they live? And why did they (except for their modern descendants, birds) die out so suddenly? We’ve always been hungry to find out more about the mysteries behind the dinosaurs’ existence. The public’s hunger for answers was first satisfied by newspapers, books, and scientific journals. But then a whole new, sensational medium was invented: motion pictures. And with its creation came a new, exciting way to explore the primeval world of these ancient creatures. But cinema is art, not science. And from the very beginning, scientific inaccuracies abounded. You might be surprised to learn that these filmic faux pas not only exist in movies from the early days of cinema. They pervade essentially every dinosaur movie that has ever been made.

One Million Years B.C.

Another film that can easily be identified as more fiction than fact is 1966’s One Million Years B.C. It tells the story of conflicts between members of two tribes of cave people as well as their dangerous dealings with a host of hostile dinosaurs (such as Allosaurus, Triceratops, and Ceratosaurus). However, neither modern-looking humans nor dinosaurs (again, except birds) existed one million years ago. In the case of dinosaurs, the movie was about 65 million years too late. Non-avian dinosaurs disappeared 66 million years ago during a mass extinction known as the K/Pg (which stands for “Cretaceous/Paleogene”) event. An asteroid measuring around six miles in diameter and traveling at an estimated speed of ten miles per second slammed into the Earth at what is now the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico. The effects of this giant impact were so devastating that over 75% of the world’s species became extinct. But the dinosaurs’ misfortunes were a lucky break for Cretaceous Period mammals. They were able to gain a stronger foothold and flourish in the challenging and inhospitable post-impact environment.

Cut to approximately 65 million, 700 thousand years later, when modern-looking humans finally arrived on the chronological scene. Until recently, the oldest known fossils of our species, Homo sapiens, dated back to just 195,000 years ago (which is, in geological terms, akin to the blink of an eye). And for many years, these fossils have been widely accepted to be the oldest members of our species. But this theory was challenged in June of 2017 when paleoanthropologists from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology reported that they had discovered what they thought may be the oldest known remains of Homo sapiens on a desert hillside at Jebel Irhoud in Morocco. The 315,000-year-old fossils included skull bones that, when pieced together, indicated that these humans had faces that looked very much like ours, but their brains did differ. Being long and low, their brains did not have the distinctively round shape of those of present-day humans. This noticeable difference in brain shape has led some scientists to wonder: perhaps these people were just close relatives of Homo sapiens. On the other hand, maybe they could be near the root of the Homo sapien lineage, a sort of protomodern Homo sapien as opposed to the modern Homo sapien. One thing is for certain, the discovery at Jebel Irhoud reminds us that the story of human evolution is long and complex with many questions that are yet to be answered.

The Land Before Time

Another movie that misplaces its characters in the prehistoric timeline is 1988’s The Land Before Time. The stars of this animated motion picture are Littlefoot the Apatosaurus, Cera the Triceratops, Ducky the Saurolophus, Petrie the Pteranodon, and Spike the Stegosaurus. As their world is ravaged by constant earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, the hungry and scared young dinosaurs make a perilous journey to the lush and green Great Valley where they’ll reunite with their families and never want for food again. In their on-screen imagined story, these five make a great team. But, assuming that the movie is set at the very end of the Cretaceous (intense volcanic activity was a characteristic of this time), the quintet’s trip would have actually been just a solo trek. Ducky and Petrie’s species had become extinct several million years earlier, and Littlefoot and Spike would have lived way back in the Jurassic Period (201– 145 million years ago). Cera alone would have had to experience several harrowing encounters with the movie’s other latest Cretaceous creature, the ferocious and relentless Sharptooth, a Tyrannosaurus rex.

Speaking of Sharptooth, The Land Before Time’s animators made a scientifically accurate choice when they decided to draw him with a two-fingered hand, as opposed to the three fingers traditionally embraced by other movie makers. For 1933’s King Kong, the creators mistakenly modeled their T. rex after a scientifically outdated 1906 museum painting. Many other directors knowingly dismissed the science-backed evidence and used three digits because they thought this type of hand was more aesthetically pleasing. By the 1920s, paleontologists had already hypothesized that these predators were two-fingered because an earlier relative of Tyrannosaurus, Gorgosaurus, was known to have had only two functional digits. Scientists had to make an educated guess because the first T. rex (and many subsequent specimens) to be found had no hands preserved. It wasn’t until 1988 that it was officially confirmed that T. rex was two-fingered when the first specimen with an intact hand was discovered. Then, in 1997, Peck’s Rex, the first T. rex specimen with hands preserving a third metacarpal (hand bone), was unearthed. Paleontologists agree that, in life, the third metacarpal of Peck’s Rex would not have been part of a distinct, externally visible third finger, but instead would have been embedded in the flesh of the rest of the hand. But still, was this third hand segment vestigial, no longer serving any apparent purpose? Or could it have possibly been used as a buttressing structure, helping the two fully formed fingers to withstand forces and stresses on the hand? Peck’s Rex’s bones do display evidence that strongly supports arm use. You can ponder this paleo-puzzle yourself when you visit Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Dinosaurs in Their Time exhibition, where you can see a life-sized cast of Peck’s Rex facing off with the holotype (= name-bearing) T. rex, which was the first specimen of the species to be recognized (by definition, the world’s first fossil of the world’s most famous dinosaur!).

T. rex in Dinosaurs in Their Time. Image credit: Joshua Franzos, Treehouse Media

Jurassic Park

One motion picture that did take artistic liberties with T. rex for the sake of suspense was 1993’s Jurassic Park. In one memorable, hair-raising scene, several of the movie’s stars are saved from becoming this dinosaur’s savory snack by standing completely still. According to the film’s paleontological protagonist, Dr. Alan Grant, the theropod can’t see humans if they don’t move. Does this theory have any credence, or was it just a clever plot device that made for a great movie moment? In 2006, the results of ongoing research at the University of Oregon were published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, providing a surprising answer. The study involved using perimetry (an ophthalmic technique used for measuring and assessing visual fields) and a scale model T. rex head to determine the creature’s binocular range (the area that could be viewed at the same time by both eyes). Generally speaking, the wider an animal’s binocular range, the better its depth perception and overall vision. It was determined that the binocular range of T. rex was 55 degrees, which is greater than that of a modern-day hawk! This theropod may have even had visual clarity up to 13 times greater than a person. That’s extremely impressive, considering an eagle only has up to 3.6 times the clarity of a human! Another study that examined the senses of T. rex determined that the dinosaur had unusually large olfactory bulbs (the areas of the brain dedicated to scent) that would have given it the ability to smell as well as a present-day vulture! So, in Jurassic Park, even if the eyes of T. rex had been blurred by the raindrops in this dark and stormy scene, its nose would have still homed-in on Dr. Grant and the others, providing the predator with some tasty midnight treats.

Now, it may seem that this blog post might be a bit critical of dinosaur movies. But, truly, I appreciate them just as much as the next filmophile. They do a magnificent job of providing all of us with some pretty thrilling, edge-of-your-seat entertainment. But, somewhere along the way, their purpose has serendipitously become twofold. They have also inspired some of us to pursue paleontology as a lifelong career. So, in a way, dinosaur movies have been of immense benefit to both the cinematic and scientific worlds. And for that great service, they all deserve a huge round of applause.

Shelby Wyzykowski is a Gallery Experience Presenter in CMNH’s Life Long Learning Department. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

#Carnegie Museum of Natural History#Dinosaurs#Dinosaur Movies#Jurassic Park#Jurassic#Land Before Time#Paleontology

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

An introduction to DeVita

Do you want to learn all about the AOMG artist DeVita? This article will cover everything you need to know about the third female member to join the labels roster.

The content of this article is also available in video format, embedded at the bottom of this article.

Prelude

In early April of 2020, the Korean hip-hop label AOMG ambiguously announced that a new artist was signing onto the label. This label was grounded by the Korean-American triple-threat; Jay Park, who’s also one of its executives. This is a label with a very organic feel and artist-oriented nature, which stands out compared to many other music labels.

On April 3rd, the label’s official Instagram account posted a video. It was titled, “Who’s The Next AOMG?” where fellow AOMG members talked about this upcoming recruit. They sprinkled small hints and details by sharing their thoughts on the artist without mentioning who.

Around the world, fans immediately began speculating on who this could be. The major consensus was that it had to be the solo artist Lee Hi, due to reporting like this: “AOMG responds ‘nothing is confirmed’ to reports of Lee Hi signing on with the label”

A few other names got thrown in fan speculations like Hanbin (B.I), previous member of IKON, Jvcki Wai, and MOON (문) aka Moon Sujin. This despite a few of these already being signed to other labels.

On April 6th, three days later, the account was updated with a part two. This time dropping more hints, which would exclude many names from fan speculations.

On the 7th of April, the label’s official Instagram account posted a short teaser. The video sported an 80’s retrofuturistic setting, with a woman turned from the camera, dressed in all black, rocking braids, and some glistening high-heels. As it seemed to be a female, some were now certain that it had to be Lee Hi. A small few actually guessed correctly that the one who would be joining AOMG would be Ms DeVita.

Finally on April 9th, it was official! She debuted with the music video, from which the teaser clips was taken from, EVITA!, which accompanied the release of her EP, CRÈME.

What does the name DeVita mean?

The name DeVita, draws inspiration and meaning from two things. Firstly, Eva Perón – also known as Evita – who was Argentina’s former First Lady. When Chloe was learning about Eva’s life, it inspired her to combine “Devil” and “Evita”, thus creating “DeVita”. The name signifies the duality of how both Eva Perón and DeVita could be perceived. Either being a devil, or an angel depending on the eye of the beholder. Secondly, Salvatore Di Vita, a character from Cinema Paradiso, was also a source of inspiration.

An introduction to DeVita

Chloe Cho – now known under the artist name DeVita – was born and raised in South Korea, until the age of eleven. In 2009, she moved to Chicago, where she would learn English.

In 2013, she went back to Korea and participated in the third season of the show; K-pop Star. A talent show, where the “big three” (the three largest music labels in Korea) hosts auditions to find the next big k-pop star. However she didn’t win, therefore neither got signed.

Later on, she returned to Chicago and graduated high school. After reflecting on what she wanted to do next, she decided to make music. In 2014, her pursuit to become an artist brought her to the talent show Kollaboration. On this show, she performed covers and actually ended up being a finalist. Despite her talents, she did not triumph as the winner of the show.

Not letting these losses stop her, she started releasing music on Soundcloud. The earliest release I could find, Halfway Love (Ruff), was from 2016. Her catalogue consisted of both covers and original music.

One day, Kirin, an artist and CEO of the music label 8balltown Records, was introduced to DeVita’s music. He liked what he heard and the two linked up. In May of 2018, WEKEYZ, one of 8balltown’s producer duos released a track titled Sugar. This track featured both DeVita, and the AOMG rapper Ugly Duck. This was the beginning of many collaborations to come.

On August 28th of 2018, just a few months later, AOMG released Sugar (Puff Daehee Mix).

This was a remix done by Puff Daehee, the alter ego of Kirin. Along with this track, it was accompanied by a music video starring Kirin, DeVita, and Ugly Duck. For most people, this was their first time seeing DeVita.

DeVita continued doing features on many songs by Korean artists while creating a little buzz for herself. There’s one notable feature, which could be seen as an important milestone in her career. That is her feature on the track Noise, from AOMG artist Woo Won Jae’s project, titled af.

In a tweet a few days after the release of CRÈME, she shared the significance of this moment.

“I was still making minimum wage working at a restaurant back when Noise dropped- I wrote my part during my shift on the back of this receipt paper. This was about a year and a half ago. A little bit after that I got a call from Pumpkin at 3am Chicago time. He said Jay wanted to meet in Philly in 4 hours. They put me on a plane and the rest is history.”

The phone call she mentioned in her tweet, about Jay wanting to meet, must have been made around September 2018. Jay was performing in Philadelphia at the time. The moment they met in Philadelphia was actually captured through a photo of the two. However, this picture ended up getting removed later on.

Fast forward a few months and Jay had just released his Ask About Me EP. The project focused on a western audience, so he went to the States on a promo run. During his visit, he also met up with DeVita once again, as can be seen here.

Finally, on April 9th, her being signed to AOMG was officially announced and she debuted with her EP titled CRÈME. Her joining AOMG, looked like something that happened pretty naturally. The vast majority of artists she had collaborated on tracks with happened to be AOMG members. Getting comfortable with the AOMG family, likely made the decision to join crystal clear.

Artistically

Just a quick look at her body of work thus far, a majority of it is in English. However, she has no issues singing in Korean, as proven by her feature on Code Kunst’s; Let u in. The tone in her voice has this sort of mixture of many singers, a melting pot of sorts. It reminds me of Audrey Nuna, SAAY, H.E.R, some vocal riffs from Dinah Jane, and at times, just a tiny bit of Ariana Grande.

As an artist, she’s still in the early stages of carving out her own unique sound and style. There’s incredible potential here, but her distinct identity is not completely there yet. I see before me a caterpillar that within a couple years, will transform into a butterfly, with its own identifiable pattern to spread its wings out on.

From what she’s shown so far, I would say she seems most comfortable doing R&B and soul music. However, beyond a quick description I prefer to refrain from categorizing her. Mostly because artists generally feel limited when categorized. More importantly, because we have no idea what she has in store for the future.

Debut EP: CRÈME

CRÈME is DeVita’s “crème de la crème”. She constantly modified the tracklist to present her debut project in a way that held her personal standard; essentially presenting us her best tracks. The result is CRÈME, which consists of five tracks, with a runtime of fourteen minutes altogether.

This EP showcases the fact that she is a competent songwriter, able to write some soulful, emotional ballads. It is completely in English and all the tracks are written by her, telling both life stories of her own and that of others. A majority of the production was handled by her “musical soulmate”; TE RIM, but other notable names, like Code Kunst show up as well.

Tracks:

Movies, introduces the project in a very gentle manner. In the track, DeVita paints a picture of a criminal couple, getting a rush, by committing crimes together. The lyrics feel inspired by movies like Bonnie and Clyde. My initial thoughts were that, for some ears, it could possibly be “too” calm as an opener. It doesn’t demand attention the way EVITA! does. Simply put, it’s not a bad track. I would just have put this track later on in the EP.

EVITA!, is something different compared to what I hear from others in the K-R&B lane. I love the 80’s aesthetic in both the track and music video. Sonically, the nostalgic saxophone riffs, warm lush synth pads, thumping bass line, results in a trip back to the 80s. With this recipe, topped with DeVita’s “current” contemporary soul and R&B voice makes for an interesting combination. The music video had that futuristic 80’s look with the neon colors, and I loved how the guns she played around with looked a lot like the “Needlers” from the Halo franchise. The title is once again just like DeVita’s name, an ode to the controversial Eva Perón. The instrumental was originally used by TE RIM, the producer of the track in 2017. His version has the same title as DeVita’s version and I recommend giving that one a listen as well, as it has a different feel to it. This track was definitely one of the highlights of the EP.

All About You, is a simple yet beautiful piano love ballad. Originating from her own tales of love, her vocals effortlessly capture what she felt during these moments.

1974 Live, is yet another ballad, but this time, with a calm guitar backing, playing a poppier R&B chord progression. DeVita’s voice is given a lot of space to be in the center of the track. As soon as I heard this track I became curious. What was the significance of this year, which would have her title the track as such? My questions were left unanswered… until the EP had marinated a while, when she tweeted: “1974 Live is about Christine Chubbuck”. In case you’re unfamiliar, Christine Chubbuck was a television news reporter, who made history in 1974. She was the first person to commit suicide live on air. According to her mother Christine’s suicide would on paper be due to an unfullfilling personal life. All throughout her life, she had experienced unreciprocated love. With this information tying back to the track, it becomes a lot less ambiguous and reveals a more cohesive narrative.

Show Me, is the final track of the EP, featuring immaculate production from the talented CODE KUNST. The sound is very moody, which fits her voice like a glove. This is my favorite performance on the entire EP, both lyrically and vocally. The lyrics present someone who’s fed up dealing with men, who talk the talk but don’t walk the walk. Now she’s looking for love with someone who’s honest and “real”.

With the project being a year old now, it has already gotten her nominated for both Rookie of the Year along with EVITA being nominated for Best R&B & Soul Track in the 18th iteration of the Korean Music Awards.

A majority of listeners seemed to enjoy the project. Many seem to be in love with her voice judging by the endless amounts of praise she has received, often described as painfully addicting, soothing, smooth, and so on.

I also asked a friend who’s a huge fan of Korean music, especially the hiphop and r&b scene to share her thoughts on the project. Here’s what she said:

"This whole project is empowering, in particular the tracks Show Me and EVITA! DeVita being a new artist, managed to impress me and many more listeners through this EP. As mentioned earlier, empowering lyrics with unique melodies and beats. Especially with the track EVITA! The fact that 1974 Live and EVITA! was referring to, two historically important women, is something that I love. This is one of my favorite EP:s of 2020 and DeVita is now included in my list of favorite artists." @Haonsmom

From what I’ve seen, only a few have been vocal about not really being too fond of the project. Some were left a bit disappointed, as they were expecting more hip-hop and R&B from an AOMG artist. The lack of “danceable” tracks was also a concern to some. Despite these criticisms, one thing was always mentioned; the girl has a beautiful voice and is obviously talented.

After listening to this EP, I hear a lot of potential. Being an EP with just five tracks, it definitely avoids overstaying its welcome. It’s brief enough to allow a listen through the entire project, no matter what you’re doing. My favorite tracks would have to be Show Me and EVITA!, but I found the whole project to be enjoyable. This EP is sprinkled with lovely vocal performances and simple but captivating production. I do still stand by my opinion that Movies would have fit better later in the tracklist if you’re chasing that mainstream ear.

I think the way EVITA! kicks you in the face, demanding attention, would’ve been a better fit as the opening track. In contrast to the other tracks, the energy level is unique, making the placement feel odd as the rest of the tracks have a chill vibe. All in all, this project gave me a taste of the “crème” but left me with a curious yearning for what this chef will whip up for dessert.

Bright future ahead

The addition of more female artists to the AOMG roster was much needed. Hoody was the first and only female member for about four years. This was the case up until late 2019, where she was then joined by sogumm, who had just won AOMG’s audition program called SignHere. Now funnily enough after DeVita, Lee Hi actually did end up officially signing with AOMG on July 22, last year.

Based on what I’ve heard during Devita’s Kollaboration days, she has improved immensely. This topped with her leaving the impression of someone passionate about their craft, bodes well for what's to come. She seems to be someone who'll constantly evolve.

Following an artist, at the early stages of their career, is something that I always find exciting. With such a lovely debut, I cannot wait to see what the future has in store for DeVita.

To view the content of this article in video format simply play the video embedded below.

youtube

Thanks for reading, watching. If you enjoyed this content feel free to follow my socials to stay up to date on when new content is posted.

https://allmylinks.com/dossi-io

Credits:

The first image in article: Original photo, pre-edit from @jinveun

Gif from the Sugar Puff Daehee MV: @moxiepoints

#devita#krnb#jay park#aomg#h1ghrmusic#8balltown#kpop#review#korea#uglyduck#chloe devita#chloe cho#kirin#evita!#crème#moon sujin#khh#korean hip hop#krap

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Music for Films, Vol. II: Chick Habit

For good and for ill, Quentin Tarantino’s movies have been strongly associated with postmodern pop culture — particularly by folks whose reactions to the word “postmodern” tend toward pursed lips and school-marmishly wagged fingers. There for a while, reading David Denby on Tarantino was similar to reading Michiko Kakutani on Thomas Pynchon: almost always the same review, the same complaints about characters lacking “psychological depth,” the same handwringing over an ostensible moral insipidness. Truth be told, Tarantino’s pranksome delight with flashy surfaces and stylistic flourishes that are ends in themselves gives tentative credence to some of the caviling. Critics have raised related concerns over the superficiality of Tarantino’s tendency toward stunt casting, especially his resurrections of aging actors relegated to the film industry’s commercial margins: John Travolta, Pam Grier, Robert Forster, David Carradine, Darryl Hannah, Don Johnson and so on. There might be a measure of cynicism in the accompanying cinematic nudging and winking, but it’s also the case that a number of the performances have been terrific.

The writer-director brings a similar sensibility to his sound-tracking choices, demonstrating the cooler-than-thou, deep-catalog knowledge of an obsessive crate-digger. Tarantino thematized that knowledge in his break-through feature, Reservoir Dogs (1992). Throughout the film, the characters tune in to Steven Wright deadpanning as the deejay of “K-Billy’s Super Sounds of the Seventies”; like the characters, the viewer transforms into a listener, treated to such fare as the George Baker Selection’s “Little Green Bag” (1970) and Harry Nilsson’s “Coconut” (1971). As with the above-mentioned actors, Tarantino has sifted pop culture’s castoffs and detritus, unearthing songs and delivering experiences of renewed value — and thereby proving the keenness of his instincts and aesthetic wit. “Listen to (or look at) this!” he seems to say, with his cockeyed, faux-incredulous grin. “Can you believe you were just going to throw this out?” And mostly, it works. If the Blue Swede’s “Hooked on a Feeling” (1974) has become a sort of semi-ironized accompaniment to hipsterish good times, that resonance has a lot more to do with Tim Roth, Harvey Keitel and Co. cruising L.A. in a hulking American sedan than with the Disney Co.’s Guardians of the Galaxy (2014).

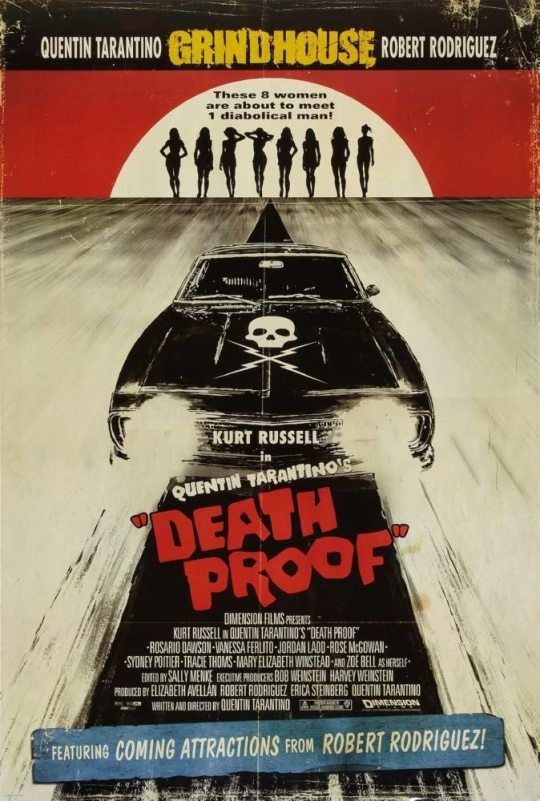

In Death Proof (2007), Tarantino’s seventh film and unaccountably his least favorite, soundtrack and screen are both full to bursting with the flotsam and jetsam of “entertainment” conceived as an industry.

youtube

In just the opening minutes, we see outmoded moviehouse announcements, complete with cigarette-burn cue dots; big posters of Brigitte Bardot from Les Bijoutiers du claire de lune (1958) and of Ralph Nelson’s Soldier Blue (1970) bedecking the apartment of Jungle Julia (Sydney Tamiia Poitier); the tee shirt worn by Shanna (Jordan Ladd), which bears the image of Tura Satana; and strutting under all of it are the brassy cadences of Jack Nitzsche’s “The Last Race,” taken from his soundtrack for the teensploitation flick Village of the Giants (1965). Bibs and bobs, bits and pieces of low- and middle-brow cinema are cut up and reconstructed into a fulsome swirl of signs. And there’s an unpleasant edge to it; the cuts are echoed by the action of the camera, which has been busily cleaving the bodies of the women on screen into fragments and parts. First the feet of Arlene (Vanessa Ferlito), propped up on a dashboard; then Julia, all ass and gams; then Arlene’s lower half again, chopped into slices by the stairs she dashes up (“I gotta take the world’s biggest fucking piss!”) and by the close-up that settles on her belly and pelvis, her hand shoved awkwardly into her crotch.

As often happens in Tarantino’s movies, furiously busy meta-discursive play collapses the images’ problematic content under multiple levels of reference and pastiche. The film is one half of Grindhouse (2007), Tarantino’s collaboration with his buddy Robert Rodriguez, an old-fashioned double-feature comprising the men’s love letters to the exploitation cinema of the 1960s and 1970s. In those thousands of movies — mondo, beach-cutie, nudie-cutie, women in prison, early slasher, rape-revenge, biker gang, chop-socky, Spaghetti Western and muscle-car-worship flicks (and we could add more subgenres to the list) — symbolic violence inflicted on women’s bodies was de rigueur, and frequently the principal draw. Tarantino shot Death Proof himself, so he is (more than usually) directly responsible for all the framing and focusing — and he’s far too canny a filmmaker not to know precisely what he’s doing with and to those bodies. The excessive, camera-mediated gashing and trimming is a knowing, perhaps deprecating nod to all that previous, gratuitous T&A. His sound-tracking choice of “The Last Race” metaphorically underscores the point: in Bert I. Gordon’s Village of the Giants, bikini-clad teens find and consume an experimental growth serum, which causes them to expand to massive proportions. Really big boobs, actual acres of ass. Get it?

Of course, all the implied japing and judging is deeply embedded in the film’s matrix of esoteric references and fleeting allusions. You’d have to be very well versed in the history of exploitation cinema to pick up on the indirect homage to Gordon’s goofy movie. But as in Reservoir Dogs, Tarantino doesn’t just gesture, he dramatizes, folding an authoritative geekdom into the action of Death Proof. In the set-up to Death Proof’s notorious car crash scene, Julia is on the phone, instructing one of her fellow deejays to play “Hold Tight!” (1966) by Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick & Tich. Don’t recognize the names? “For your information,” Julia snorts, Pete Townsend briefly considered abandoning the Who, and he thought about joining the now-obscure beat band, to make it “Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick, Tich & Pete. And if you ask me, he should have.”

youtube

It’s among the most gruesomely violent sequences in Tarantino’s films (which do not run short on graphic bloodshed), and Julia receives its most spectacular punishment. Those legs and that rump, upon which the camera has lavished so much attention, are torn apart. Her right leg flips, flies and slaps the pavement, a hunk of suddenly flaccid meat. Again, Tarantino proves himself an adept arranger of image, sign and significance. Want to accuse him of fetishizing Julia’s legs? He’ll materialize the move, reducing the limb to a manipulable fragment, and he’ll invest the moment with all of the intrinsic violence of the fetish. He’ll even do you one better — he’ll make that violence visible. Want to watch? You better buckle up and hold tight.

Hold on a second. “Hold Tight”? The soundtrack has passed over from intertextual in-joke to cruel punchline. It doesn’t help that the song is so much fun, and that it’s fun watching the girls groove along to it, just before Stuntman Mike (Kurt Russell) obliterates them, again and again and again. The awful insistence of the repetition is another set-up, establishing the film’s narrative logic: the repeated pattern and libidinal charge-and-release of Stuntman Mike’s vehicular predations. It is, indeed, “a sex thing,” as Sheriff Earl McGraw (Michael Parks) informs us in his cartoonish, redneck lawman’s drawl. Soon the sexually charged repetitions pile up: see Abernathy’s (Rosario Dawson) feet hanging out of Kim’s (Tracie Thom) 1972 Mustang, in a visual echo of Arlene’s, and of Julia’s. Then listen to Lee (Mary Elizabeth Winstead) belt out some of Smith’s cover of “Baby It’s You” (1969), which we most recently heard 44 minutes before, as Julia danced ecstatically by the Texas Chili Bar’s jukebox. Then watch Abernathy as she sees Stuntman Mike’s tricked-out ’71 Nova, a vibrating hunk of metallic machismo — just like Arlene saw it, idling menacingly back in Austin, with another snatch of “Baby It’s You” wisping through that moment’s portent.

For a certain kind of viewer, the Nova’s low-slung, growling charms are hard to resist, as is the sleazy snarl of Willy DeVille’s “It’s So Easy” (1980; and we might note that Jack Nitzsche produced a couple of Mink DeVille’s early records, connecting another couple strands in the web) on the Nova’s car stereo. Those prospective pleasures raise the question of just who the film is for. That may seem obvious: the same folks — dudes, mostly — who find pleasure in exploitation movies like Vanishing Point (1971), Satan’s Sadists (1969) or The Big Doll House (1971). But there are a few other things to account for, like how Death Proof repeatedly passes the Bechdel Test, and how long those scenes of conversation among women go on, and on. Most notable is the eight-minute diner scene, a single take featuring Abernathy, Kim, Lee and Zoë (Zoë Bell, doing a cinematic rendition of her fabulous self, an instance of stunt casting that literalizes the “stunt” part). Among other things, the women discuss their careers in film, the merits of gun ownership and Kim and Zoë’s love of (you guessed it) car chase movies like Vanishing Point. One could read that as a liberatory move, a suggestion that cinema of all kinds is open to all comers. All that’s required is a willingness to watch. But watching the diner scene becomes increasing claustrophobic. The camera circles the women’s table incessantly, and on the periphery of the shot, sitting at the diner’s counter, is Stuntman Mike. The circling becomes predatory, the threat seems pervasive.

If you’ve seen the film, you know how that plays out: Zoë and Kim play “ship’s mast” on a white 1970 Dodge Challenger (the Vanishing Point car); Stuntman Mike shows up and terrorizes them mercilessly; but then Abernathy, Zoë and Kim chase him down and beat the living shit out of him, likely fatally. In another sharply conceived cinematic maneuver, Tarantino executes a climactic sequence that inverts the diner scene: the women surround Stuntman Mike, abject and pleading, and punch and kick him as he bounces from one of them to another. The camera zips from vantage to vantage within the circle, deliriously tracking the action. All the jump cuts intensify the violence, and they provide another contrast to the diner’s scene’s silky, unbroken shot. The sounds and the impact of the blows verge on slapstick, and our identification with the women makes it a giddily gross good time.

youtube

So, an inversion seeks to undo repetition. Certainly, Stuntman Mike’s intent to repeat the car-crash-kill-thrill is undone, and predator becomes prey. But, as is inevitable with Tarantino’s cinema, there are complications, other echoes and patterns to suss out. For instance: as the women stride toward the wrecked Nova, while Stuntman Mike pathetically wails, the camera zooms in on their asses. Bad asses? Nice asses? What’s the right nomenclature? To make sure we can put the shot together with Julia’s first appearance in the film, Abernathy has hiked up her skirt, revealing a lot of leg. Repetition reasserts itself. In an exacerbating circumstance, Harvey Weinstein’s grubby fingerprints are smeared onto the film. Rodriguez’s Troublemaker Studios is credited with production of Grindhouse, but Dimension Films, a Weinstein Brothers company, handled distribution.

When the film cuts to its end titles, we hear April March’s “Chick Habit” (1995), with its spot-on lyric: “Hang up the chick habit / Hang it up, daddy / Or you’ll never get another fix.” And so on. Even here, where the girl-power vibe feels strongest (cue Abernathy burying a bootheel in Stuntman Mike’s face), there are echoes, patterns. Note how the striding bassline of “Chick Habit” strongly recalls the pulse beating through Nitzsche’s “The Last Race.” Note that March’s song is a cover, of “Laisse tomber les filles,” originally recorded by yé-yé girl France Gall. The song was penned by Serge Gainsbourg, pop provocateur and notorious womanizer. The two collaborated again, releasing “Les Sucettes,” a tune about a teeny-bopper who really likes sucking on lollipops, when Gall was barely 18; the accompanying scandal nearly torpedoed her career. Gall refused to ever sing another song by Gainsbourg, and disavowed her hits.

Again, that’s all deeply embedded, somewhere in the film’s complicated play of pop irony and double-entendre and the sudden explosions of delight and disgust that intermittently reveal and conceal. Again, you’d have to know your pop history really well to catch up with the complications, and Death Proof moves so fast that there’s always another reference or allusion demanding your attention as the cars growl and the blood spurts. Too many signs to track, too many signals to decipher — that’s the postmodern. But perhaps we have become too glib, assuming that all signs are somehow equivalent. Death Proof insists otherwise. Much has been made of the film’s strange relation to digital filmmaking, of the sort that Rodriguez has made a career out of. Part of Grindhouse’s shtick is its goofball applications of CGI, all the scratches and skips and flaws that the filmmakers lovingly applied. They are digital effects, masquerading as damaged celluloid. Tarantino cut back against that grain, filming as much of the car chase’s maniacal stuntwork in meatspace as he safely could. Purposeful practical filmmaking, for a digitally enhanced cinematic experience, attempting to mimic the ways real film interacts with the physical environment and its manifold histories. Is that clever, or just more cultural clutter?

Amid all the clutter that crowds the characters onscreen, and their conversations in the film’s field of sound, it can be easy to lose track of the distinctions between appearances and the traces of the real bodies that worked to bring Death Proof to life. Which is why Tarantino’s inclusion of Bell is so crucial. She provides another inversion: Instead of masking her individual presence, doing stunts for other actresses in their clothes and hair (for Lucy Lawless in Xena: Warrior Princess, or for Uma Thurman in Tarantino’s Kill Bill films), Bell is herself, doing what she does best, projecting the technical elements of filmmaking — usually meant to bleed seamlessly into illusion — right onto the surface of the screen. And instead of allowing one group of girls to slip into a repeated pattern, bodies easily exchanged for other bodies, Bell’s presence and its implicit insistence on her particularity (who else can move like she does?) breaks up the superficial logic of cinema’s market for the feminine. She disrupts its chick habit. There’s only one woman like her.

youtube

Jonathan Shaw

#music for films#chick habit#jonathan shaw#dusted magazine#death proof#quentin tarantino#reservoir dogs#grindhouse#Dave Dee Dozy Beaky Mick & Tich

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The brutality and desperation of war

Throughout history of cinema, war has been one of the most common topics and one of the most used backdrops to tell stories. So when a new war film comes along and it feels like something you have never seen before, it will certainly get a lot of attention. ‘1917’ by Sam Mendes is that film! Not only does it take place during the first world war (a commonly overseen war in more recent cinematic history), but it also takes the daring cinematic choice to film and edit the film as if it is one single take. That alone makes it interesting, but it is the sheer quality of the filmmaking, the acting, the score and the cinematography that turns this little story in to an exceptional film that simply demands to be seen in the cinema!

The story IS small and extremely simple. Two young british soldiers are given a task of extreme importance and with deadly possibilities, when they are asked to cross the - apparently deserted - German frontline and the dangerous no-man’s land to reach another British battalion to give them an important order from the general. An imminent attack must be stopped to prevent the involved troops (including the older brother of one of our protagonists) from falling into a German ambush. They have until dawn. In its core the story is simple and with the film’s one-take vision, this simplicity becomes one of its main assets. Here we do not have a lot of extra side stories to give the (extreme amount of) British acting super stars’ supporting roles more screen time. We do not have long montages showing the consequences of the war. No the supporting roles are reduced to mere cameos as these people would be in the soldiers’ mission, and the consequences of war are shown as a natural and organic part of the surroundings as our two main characters make their way through the different war zones. And the camera never loses these two soldiers out of sight - we are with them through it all.

These two soldiers who truly are the only fully fleshed characters of our story are portrayed with impressive amount of nuance and details by young duo Dean-Charles Chapman (of ‘Game of Thrones’), 22, and George McKay (of ‘Captain Fantastic’), 27. I remember when I first read of the film and it was described as “Sam Mendes WWI film starring Colin Firth, Mark Strong and Benedict Cumberbatch”. While these three huge British actors are still here, they are in no way carrying this film - their cameos are strong, make no mistake, and the same can be said about a brilliant Andrew Scott (delivering a few, rare laughs) and a touching Richard Madden - but this film belongs to Chapman and McKay.

Chapman sends off some young Di Caprio vibes here in both looks and acting ability as he infuses his young Lance Corporal Blake with a vulnerable mix of naive empathy and goal-oriented focus. Opposite him, McKay is the main star of the film as the slightly older and more haunted, Lance Corporal Schofield, who is mostly drawn into this mission by coincidence. It is simply awe-inspiring to witness the character development McKay manages to portray without the camera ever letting him out of sight or cutting away (the film has only one (!) visible cut). You feel his desperation, his isolation, his traumas that are still evolving and his forceful devotion to the life that is now the only he can truly be in. In one specifically touching scene, he opens up about the true feelings of going home from the war on leave. McKay delivers this scene with such a presence and delicate delivery that your view on his character is changed instantly. A very strong performance that sadly seem to be ignored in any awards context in an exceptionally crowded year for male leads.

Another reason for this lack of acknowledgement of Chapman and McKay in awards season might also be the fact that ‘1917’ more than anything has left people stunned by its crafts. And it has to be said, that - while regrettable - this is very understandable. The meticulous planning that Sam Mendes and cinematography mastermind, Roger Deakins, have had to put into every single shot is astounding. Not only does it demand extreme precision to shoot a film as ‘one-take’ but to do it while creating hauntingly beautiful and yet naturalistic imagery is simply cinematic beauty of the highest order. The film is in no way focused on making as many aesthetically beautiful shots as possible (although an early crossing of a no-man’s land water hole, a flare illuminated city of ruins and a final shot of relief are absolutely stunning), but every shot is filled with details that I cannot wait to discover even more of on my next viewing. Roger Deakins is a cinematography legend and he seems destined to win every single cinematography award of the season after which he - obviously - can send a much deserved ‘thank you’ to editor Lee Smith for putting it all seamlessly together.

It is, however, not only visually that the film simply demands to be seen in the cinema. The sound mixing and editing is brilliant too and follows suit with the naturalistic visuals. Every gunshot, every explosion and every scene of absolute silence feel real; here are now over-the-top, enhanced sound effects. Another brick in the construction of an extremely intense and nerve-racking experience that is rounded off by a brilliant and fittingly subtle score by Thomas Newman. Admittedly, it does have a few classic, suspenseful orchestrations (especially towards the end), but its true strength is that it also allows itself to be subtle and quiet when it needs to be. People who have seen the first full length trailer, will be happy to find that its beautiful rendition of the song ‘Wayfaring Stranger’ is also found in the film in a very fine scene.

With ‘1917’ Sam Mendes has made an original film that, despite the fact that it probably features every single war film cliché out there (but hey, war in itself is pretty cliché, right?), manages to grab you from the very first second before tying you to your chair for two hours before the credits allow you to finally breath again and take your first handful of popcorn. It shows the brutality and desperation of war, while it ironically manages to show vast nuances of warfare through its simplicity. Every soldier (and every dead body) that the camera slowly and objectively pans over have their own stories to tell, and that is thought-provoking to dwell on once you have left the cinema having witnessed just two of these stories. The film feels almost nihilistic at times with its disregard of every empathetic move or gesture until a spark of hope and life is given by the warm light of a fire just when the story seems as bleak as possible.

As such the film of course is a tightly planned construction and it does require a certain suspension of disbelief, but isn’t that part of what film can do? If you just suspend your disbelief for a couple of hours you can be told stories, given experiences and presented to ideas deeply founded in reality. I, for one, think so and as such this film is a surprising masterpiece for me. With its intense simplicity, groundbreaking use of “one-take” techniques and gorgeous visuals, nerve-racking sound design, beautifully composed score and profoundly moving acting, ‘1917’ is Sam Mendes showing us every single reason why films should still be enjoyed in the cinema. He does that while telling a gripping story of a reality that will forever be embedded in our history all the while it sadly still is the reality for far too many people across the globe. A cinematic triumph!

5/5

#Academy Awards 2020#Oscars 2020#Film Review#Movie Review#1917#Sam Mendes#George McKay#Dean-Charles Chapman#Colin Firth#benedict cumberbatch#Mark Strong#Andrew Scott#Richard Madden#Roger Deakins

80 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Haunting (1963)

Why do people like being scared? I am not one to answer this question, but even a non-thrill seeker like myself can appreciate a decent fright. For centuries, humans have been imparting to others stories of haunted places, ghastly monsters, the occult. That storytelling tradition has long endured and, of course, it would someday touch cinema. As film matures as a medium, there are certain films that produce experiences that are uniquely cinematic, unconstrained by older mediums. One of those movies is The Haunting – released by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) and directed by Robert Wise in between his work on West Side Story (1961) and The Sound of Music (1965). Though the film may no longer be scary to those expecting machete-wielding murderers and torture-happy mannequins, The Haunting boasts a suffocating eeriness in what initially appears to be just another haunted house film. Its disturbing visuals break it from its source material’s (Shirley Jackson’s novel The Haunting of Hill House) prose, embedding itself into the imaginations of its viewers. No less significantly, The Haunting is a striking validation of the beauty and necessity of black-and-white film – it is impossible to imagine it as a color film.

In the prologue, Dr. John Markway (Richard Johnson) introduces our primary setting before telling of its violent history:

…Hill House had stood for ninety years and might stand for ninety more. Silence lay steadily against the wood and stone of Hill House, and whatever walked there… walked alone.

Dr. Markway is an anthropologist with research interests in the paranormal. To determine whether or not Hill House is haunted, he invites six individuals with extrasensory perception (ESP) or past history with paranormal events. Only two of those invitees arrive at this Massachusetts mansion: Eleanor (Julie Harris; whose character is often called “Nell”) and Theodora (Claire Bloom; whose character, heavily coded as queer, is often called “Theo”). Heir-to-the-house apparent Luke Sanderson (Russ Tamblyn) is also here. Following the opening narration, The Haunting shifts its perspective from Dr. Markway to Nell. What the four main characters find at Hill House is an estate with off-center perspectives; numerous rooms and ceilings without right angles; stylistically-clashing art and furnishings; and isolation from humanity (the house is far from the next town and is staffed by two individuals, who leave before sunset).

This is barely a spoiler, but let it be clear that Hill House is indeed haunted. What happens is no ruse, and there is no living being orchestrating the abnormalities that occur. Much is left to the viewer’s imagination – neither discovered by the characters nor explained by the filmmaking. Whatever lurks down the hall or the floor above is beyond any explanation The Haunting provides. Davis Boulton’s cinematography provides few comforts. Boulton, whose career was defined by still photography and not cinematic work, liberally employs low-angled shots and film noir-influenced chiaroscuro to highlight the house’s unusual structure and to intensify the contrasts between lit and unlit areas. Color film would make Hill House seem too inviting, too sunny, too earthly. Viewers may notice some spatial distortions along the left and right-hand side of the frame during scenes within Hill House. The effect is caused by the fact that Wise and Boulton used a technically unready 30mm wide-angle Panavision lens to shoot this film. But Wise and Boulton lean into their imperfect lens by keeping the camera moving as characters move, in addition to the unsettling Dutch angles and unusual tracking shots in the film’s second half. The widescreen Panavision format appears to be ill-suited for haunted house films, when a filmmaker may want the audience to feel as trapped as the characters. But in this exceptional case, it (perhaps unintentionally) benefits Hill House’s quietly spooky atmosphere.

Production designer Elliot Scott (1958’s Tom Thumb, 1989’s Who Framed Roger Rabbit) and set decorator John Jarvis (1953’s Knights of the Round Table, 1972’s Sleuth) have crafted a frightening set to accompany with Boulton’s cinematography. Hill House’s exterior were shot on the grounds of Ettington Park in Warwickshire, England; the interiors housing Scott and Jarvis’ work were shot at MGM-British Studios near London. The dark wood-paneled walls; the heaving large doors; dearth of right-angled corners; the creepily-placed and sad-eyed statues, limited light sources (a motley assortment of candles, gas lights, and electricity); and excessive dark-wooded furniture contribute to the house’s oppressive dread. In daylight, these rooms appear curious, eccentric. By night, the environment of the house is – at best – unnerving. The two most terrifying interior scenes during The Haunting involve interactions with the set itself. The first instance occurs in stillness, with a view of a bas relief bedroom wall. The second features a door moving in ways impossible.

The Haunting merges the paranormal and the psychological to the point where the two become indistinguishable. That may alienate some viewers, but it will certainly keep one on tenterhooks. This merger of the paranormal and psychological is mostly thanks to Julie Harris as Nell. We are not given Nell’s entire biography. Yet, the viewer can surmise that she has lived a sheltered life. Nell claims that her trip to Hill House is an opportunity for adventure, a departure from a homebound existence where she mostly spent caring for her late, bedridden mother. Harris also expresses her character’s noticeable sexual repression and need for nurture – no other actor in this film is doing as much (or as brilliantly) as she is. Nell’s tendencies and desires are sometimes articulated aggressively, without tact and consideration for the feelings of others. She can be downright loathsome as her grip on reality crumbles, with no apologies to give after a horrible remark. As Nell, Harris pushes hard against the audience’s desire to find a relatable, sympathetic central character – and thus makes the viewer question about which scenes presented from her viewpoint might be believed (days after watching this film, I am still having difficulty grappling with Nell’s unreliable perceptions).

In 114 minutes, Nell’s relationships with Theo and Dr. Markway (not so much the smarmy Luke) become more turbulent. We sense that Nell has had little interaction with people outside her household. For what might be the first time in her life, she finds comfort in both Theo and Dr. Markway. But her frustration with her family life is never far behind. Her idealization of human connection beyond the family sees her lash out at the slightest violation of said idealization. There is some mutual attraction between Nell and Theo, but the former cannot bring about herself to say anything (Nell also ineptly flirts with Dr. Markway, who thinks nothing of these advances). On occasion via voiceover, Nell reveals her inner thoughts. This is a clumsy device when first utilized, but as the film progresses, it accentuates Nell’s madness. Her thoughts become incomprehensible, contradictory, hypocritical, and divorced from observable reality.

The use of sound in The Haunting is deeply strategic. I can not write much on this without revealing much of what makes this film scary. But on multiple occasions throughout, there are wonderfully-timed sound effects – some as soft as a whisper; others as loud as thunder – that will jolt the audience from its sense of complacency and safety. Wise’s sense of timing in this regard originates from his work as director on The Curse of the Cat People (1944), the sequel to Jacques Tourneur’s Cat People (1942). Both those films shared a producer in RKO’s Val Lewton, a low-budget horror specialist. Both those films innovated the “Lewton bus” – the gradual buildup of tension, culminating in abrupt aural and/or visual terror. The Lewton bus is the progenitor of the modern jumpscare, which became de rigueur sometime in the late 1970s or early ‘80s. Compared to modern horror films, let’s just say that this Lewton bus does not mind taking its time to pull up to the station – the influence of Cat People and The Curse of the Cat People on this film is unmistakable. Through its use of its own versions of Lewton buses, The Haunting twists the terror into its viewers’ stomachs slowly, agonizingly.

English composer Humphrey Searle’s soundtrack has never been released commercially. Searle, an expert of serial music (a form of contemporary music; in brief, it is a reaction against atonalism through a form of fixed-order chromaticism), composes an uncharacteristic tonal score here. Yet, it is just barely tonal. The score mostly disappears after the opening few minutes, but it is colored by high string tremolos and runs, foreboding brass triplets, and tinny bells that are a valuable contribution the sound mix. It flirts with atonalism, but there is always some melodic sense to this score. Searle’s score is unorthodox without being experimental for its time. There appears to be no sign of motifs in Searle’s score, but the horror genre tends to resist such musical construction anyways.

Upon release, audiences and critics did not know what to make of The Haunting. Most detractors were hostile to its plot (or lack thereof). In the years since, the film has been reevaluated on how Hill House itself is a character – shrouded in the darkness, its worst secrets unknowable. Robert Wise, the cast, and the numerous technicians working on this film all contribute to one of the greatest, most spine-tingling haunted house films ever made. The paucity of its special effects and dependence on a superb acting ensemble – Julie Harris especially – have shielded The Haunting from aging.

The house or whatever is haunting it is the star of this film. It is actively searching to kill. It does so biding its time, wearing down the psychological defenses of those who, seeking excitement or a deathly fright, dare spend a night within its walls. One will see how quickly such barriers, created over a lifetime of traumas and broken dreams, can be breached. In the moody shadows that could never be created on color film, therein lies the suggestion – functionally similar to, but artistically dissimilar from Jackson’s original novel – of something sinister, calculating, and cold.

My rating: 9.5/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. Half-points are always rounded down. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found in the “Ratings system” page on my blog (as of July 1, 2020, tumblr is not permitting certain posts with links to appear on tag pages, so I cannot provide the URL).

For more of my reviews tagged “My Movie Odyssey”, check out the tag of the same name on my blog.

#The Haunting#Robert Wise#Julie Harris#Claire Bloom#Richard Johnson#Russ Tamblyn#Fay Compton#Rosalie Crutchley#Lois Maxwell#Valentine Dyall#Shirley Jackson#Nelson Gidding#Davis Boulton#Ernest Walter#Humphrey Searle#Elliot Scott#John Jarvis#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

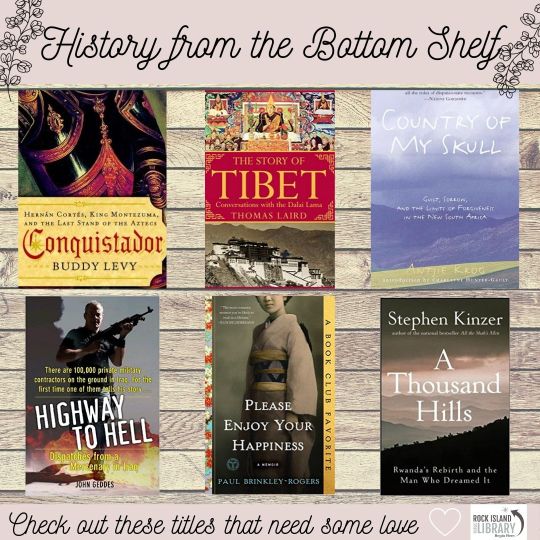

Check out these history books from our bottom shelf! All these titles need some love, so check them out today!

Summaries and Ratings from goodreads.com

Conquistador: Hernán Cortés, King Montezuma, and the Last Stand of the Aztecs by Buddy Levy

4.19/5 stars

It was a moment unique in human history, the face-to-face meeting between two men from civilizations a world apart. Only one would survive the encounter. In 1519, Hernán Cortés arrived on the shores of Mexico with a roughshod crew of adventurers and the intent to expand the Spanish empire. Along the way, this brash and roguish conquistador schemed to convert the native inhabitants to Catholicism and carry off a fortune in gold. That he saw nothing paradoxical in his intentions is one of the most remarkable—and tragic—aspects of this unforgettable story of conquest.

In Tenochtitlán, the famed City of Dreams, Cortés met his Aztec counterpart, Montezuma: king, divinity, ruler of fifteen million people, and commander of the most powerful military machine in the Americas. Yet in less than two years, Cortés defeated the entire Aztec nation in one of the most astonishing military campaigns ever waged. Sometimes outnumbered in battle thousands-to-one, Cortés repeatedly beat seemingly impossible odds. Buddy Levy meticulously researches the mix of cunning, courage, brutality, superstition, and finally disease that enabled Cortés and his men to survive.

Conquistador is the story of a lost kingdom—a complex and sophisticated civilization where floating gardens, immense wealth, and reverence for art stood side by side with bloodstained temples and gruesome rites of human sacrifice. It’s the story of Montezuma—proud, spiritual, enigmatic, and doomed to misunderstand the stranger he thought a god. Epic in scope, as entertaining as it is enlightening, Conquistador is history at its most riveting.

The Story of Tibet: Conversations with the Dalai Lama by Thomas Laird

4.18/5 stars

The Story of Tibet is a work of monumental importance, a fascinating journey through the land and history of Tibet, with His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama as guide. Over the course of three years, journalist Thomas Laird spent more than sixty hours with His Holiness the Dalai Lama in candid, one-on-one interviews that covered His Holiness’s beliefs on history, science, reincarnation, and his lifelong study of Buddhism. Traveling across great distances to offer vivid descriptions of Tibet’s greatest monasteries, Laird brings his meetings with His Holiness to life in a rich and vibrant historical narrative that outlines the essence of thousands of years of civilization, myth, and spirituality. His Holiness introduces us to Tibet’s greatest yogis and meditation masters, and explains how the institution of the Dalai Lama was founded. Embedded throughout this journey is His Holiness’s lessons on the larger roles religion and spirituality have played in Tibet’s story, reflecting the Dalai Lama’s belief that history should be examined not only conventionally but holistically. The Story of Tibet is His Holiness’s personal look at his country’s past as well as a summation of his life’s work as both spiritual and temporal leader of the Tibetan people.

Country of My Skull: Guilt, Sorrow, and the Limits of Forgiveness in the New South Africa by Antjie Krog

4.09/5 stars

Ever since Nelson Mandela dramatically walked out of prison in 1990 after twenty-seven years behind bars, South Africa has been undergoing a radical transformation. In one of the most miraculous events of the century, the oppressive system of apartheid was dismantled. Repressive laws mandating separation of the races were thrown out. The country, which had been carved into a crazy quilt that reserved the most prosperous areas for whites and the most desolate and backward for blacks, was reunited. The dreaded and dangerous security force, which for years had systematically tortured, spied upon, and harassed people of color and their white supporters, was dismantled. But how could this country--one of spectacular beauty and promise--come to terms with its ugly past? How could its people, whom the oppressive white government had pitted against one another, live side by side as friends and neighbors?

To begin the healing process, Nelson Mandela created the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, headed by the renowned cleric Archbishop Desmond Tutu. Established in 1995, the commission faced the awesome task of hearing the testimony of the victims of apartheid as well as the oppressors. Amnesty was granted to those who offered a full confession of any crimes associated with apartheid. Since the commission began its work, it has been the central player in a drama that has riveted the country. In this book, Antjie Krog, a South African journalist and poet who has covered the work of the commission, recounts the drama, the horrors, the wrenching personal stories of the victims and their families. Through the testimonies of victims of abuse and violence, from the appearance of Winnie Mandela to former South African president P. W. Botha's extraordinary courthouse press conference, this award-winning poet leads us on an amazing journey.

Highway to Hell: Dispatches from a Mercenary in Iraq by John Geddes

3.62/5 stars

Present-day Iraq: a crucible of torture, chemical warfare and Islamic terrorism, and straddling over it all the mighty US Army and its allies; but there's another western army in Iraq that dwarfs the British contingent and is second only in size to the US Army itself.

It's a disparate and anarchic multi-national force of men gathered from twenty or more countries numbering some 30,000. It's a mercenary army of men and a few women with guns for hire earning an average of $1,000 dollars a day. They are in Iraq to provide security for the businessmen, surveyors, building contractors, oil experts, aid workers and, of course, the TV crews who have flocked to the country to pick over the carcass of Saddam's regime and help the country re-build.

Not since the days when the East India Company used soldiers of fortune to depose fabulously wealthy Maharajas and conquer India for Great Britain, and mercenaries fought George Washington's Continental Army for King George, has such a large and lethal independent fighting force been assembled. Once upon a time such men were called freelances, mercenaries, soldiers of fortune or dogs of war, but today they go under a different name: private military contractors. There's a far more fundamental sea change, too, as women have joined their ranks in significant numbers for the first time, bringing a new and interesting dynamic into the equation.

In Iraq today the majority of their number are men who come from 'real deal' Special Forces units or former soldiers from regular units and regiments; all of them know what they're about and rub shoulders together more or less comfortably with at least a shared understanding of basic military requirements.

One such man is John Geddes, ex-SAS warrant officer and veteran of a fistful of hard wars who became a member of the private army in Iraq for the eighteen months immediately following George W. Bush's declaration of the end of hostilities in early May 2003. Now, for the first time, John Geddes will reveal the inside story of this extraordinary private army and the private war they are still fighting with the insurgents in Iraq.

Please Enjoy Your Happiness by Paul Brinkley-Rogers

3.56/5 stars

Please Enjoy Your Happiness is a beautifully written coming-of-age memoir based on the English author's summer-long love affair with a remarkable older Japanese woman.

Whilst serving as a seaman at the age of nineteen, Brinkley-Rogers met Kaji Yukiko, a sophisticated, highly intellectual Japanese woman, who was on the run from her vicious gangster boyfriend, a member of Japan's brutal crime syndicate the yakuza. Trying to create a perfect experience of purity, she took him under her wing, sharing their love of poetry, cinema and music and many an afternoon at the Mozart Café.

Brinkley-Rogers, now in his seventies, re-reads Yukiko's letters and finally recognizes her as the love of his life, receiving at last the gifts she tried to bestow on him. Reaching across time and continents, Brinkley-Rogers shows us how to reclaim a lost love, inviting us all to celebrate those loves of our lives that never do end.

A Thousand Hills: Rwanda's Rebirth and the Man Who Dreamed It by Stephen Kinzer

4.19/5 stars

A Thousand Hills: Rwanda's Rebirth and the Man Who Dreamed It is the story of Paul Kagame, a refugee who, after a generation of exile, found his way home. Learn about President Kagame, who strives to make Rwanda the first middle-income country in Africa, in a single generation. In this adventurous tale, learn about Kagame's early fascination with Che Guevara and James Bond, his years as an intelligence agent, his training in Cuba and the United States, the way he built his secret rebel army, his bloody rebellion, and his outsized ambitions for Rwanda.

#nonfiction#non fiction#nonfiction books#history#world history#us history#history books#historical reads#war#tibet#reflective#reading recommendations#book recs#book recommendations#reading recs#currently reading#book list#booklr#bookish#pretty books

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

How our screen stories of the future went from flying cars to a darker version of now

by Aaron Burton

Years and Years begins with the re-election of Trump in the US, and the election of unconventional populist Four Star Party in the UK. BBC/HBO

Fans of Ridley Scott’s 1982 masterpiece Blade Runner returned to cinemas for an unusual milestone: history catching up with science fiction.

Blade Runner opens in Los Angeles, in November 2019. Furnaces burst flames into the perennial night and endless rain. Flying cars zoom by. The antihero film-noir detective, Deckard (Harrison Ford) has seen too much, drinks too much, and misses his mother between “retiring replicants”.

As in “Back to the Future day”, (October 21, 2015), which marked Marty McFly’s journey into the future in the 1989 film, the Blade Runner screenings came with a flurry of discussion about what the filmmakers got right and wrong. Environmental collapse, yes. But where are our flying cars?

youtube

So: what now that the future is here?

Our current versions of near future stories - namely the television series Black Mirror (now on Netflix) and SBS’s Years and Years - explore more extreme versions of the present.

Charlie Brooker’s Black Mirror is an anthology of standalone episodes, produced between 2011 and 2019, each set in a slightly different, undated, near future.

Years and Years, written by Russell T. Davies, bravely spans 2019 to 2034 with each episode leaping forward a few years through striking montages of fictional news events: the collapse of the European Union, the US leaving the United Nations, catastrophic flooding, mass migration, widespread homelessness.

We are in a very familiar world. The “near” is depicted in a realistic way through identifiable locations, documentary-style visuals, news footage, and lifelike dialogue.

youtube

Technology: good and bad

Back in the real world, the future in the 21st century is unfolding in the palm of our hands. Elections are won and lost on social media, Sydney is covered in smoke. The rate at which technology is altering our lives is rivalled only by the rate we’re transforming our planet.

These shows explore these rates of change. In a 2016 episode of Black Mirror, “Nosedive”, every interpersonal interaction becomes a transaction: an extreme version of Uber Ratings with China’s Social Credit System.

Lacie (Bryce Dallas Howard) is an ambitious young professional excited by the opportunities higher ratings open up, such as discounts on luxury apartments, but being pleasant to her barista and workmates only gets her so far. So begins a perilous spiral of trying too hard to be liked, echoing the personality-as-product phenomenon of social media influencers around the world.

youtube

The standalone episode format of Black Mirror means it can be challenging to develop empathy for characters, consequently the interest often rests on the single concept or final twist. The episode “Striking Vipers” explores the possibility of extra-marital love between best mates in Virtual Reality; “Hang the DJ” envisions dating apps as an authoritarian apparatus.

Most episodes are neatly wrapped up for viewers to escape to for pure entertainment – but also to escape from each dystopian possibility.

In Years and Years, we follow one Mancunian family over 19 years. The series opens with Trump re-elected for a second term. In the UK, the unconventional populist Four Star Party, led by straight-speaking Vivienne Rook (Emma Thompson), rides to success on the back of social instability.

Sci-fi concepts are introduced early on so we can explore their evolution and implications. In the first episode, teenager Bethany declares herself “trans”. As progressive parents, Stephen and Celeste immediately comfort their child, who they presume is transsexual.

youtube

Bethany shrugs, “I’m not transsexual … I’m transhuman”. A concept not lost on Blade Runner fans who may be aware of transhumanist gatherings in Los Angeles in the 1980s, transhumanism is premised on the idea that humans have breached evolutionary constraints through science and technology. Biology is a restriction to the possibility of eternal life.

Disgust and dismay ensue from parents unable to comprehend why their child wants to rid her flesh and live forever as data. Through the course of the series we see how Bethany’s transhuman ambitions influence her personal relationships, health, career trajectory, and political activism.

It even starts to feel normal.

Years and Years delicately resists portraying a dystopia, allowing room for technology to demonstrate a positive influence on society. “Señor”, the ubiquitous virtual assistant, connects the Lyons family whenever they wish. Like Alexa or Siri, Señor is always at hand to answer questions – but more importantly, facilitates an intimacy that could easily be lost to technological isolation.

In 2029, grandmother Muriel digs up the dusty digital assistant Señor because she misses its company. By now, virtual assistants are embedded into the walls and omnipresent digital cloud but the Luddite grandmother resists.

“I like having something to look at, I’m not talking to the walls like Shirley Valentine,” she says.

It’s moments like these that remind us of our agency over technology and hint at its revolutionary potential to connect us all.

Lessons for the present

While classics like Blade Runner looked to the future to ignite our technological desires, near-future fiction reveals how new technologies are injected into our lives with little choice as to whether we should adopt them and little thought to their long-term appropriateness and sustainability.

These shows ask us to be critical of what might seem like minor developments in technology and politics. In an age of rapidly changing political landscapes and the climate catastrophe, it can feel like we are approaching the final frontier. In creating stories set in the near, instead of the far, future, science fiction provides valuable lessons for the present.

In other words: the choices we fail to stand up for in the near-future may prevent us from having a distant future at all.

About The Author:

Aaron Burton is a Lecturer in Media Arts at the University of Wollongong

This article is republished from our content partners over at The Conversation.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Show Notes 107 "Implosion"

Evil is afoot, Agents.

As always, you can click on this link or by clicking play on the embedded player below to listen to this week’s episode while reading the show notes.

Also, don’t forget that you can support us on Patreon!

This week's Writer Appreciation Corner focuses on Bob Goodman, a true asset to the Warehouse 13 writing staff. We love Bob Goodman and even featured a quote from his io9 article in our "Bonus 01 - Podcast 13 Season 1 Trailer,” linked here and embedded below.

You can follow him on Twitter as @b0bg00dman.

The episode starts with Pete imitating a dubbed Japanese samurai movie. This week's episode dealt a lot with a lot of ~heavy themes~ related to Japan and WWII, and interestingly those themes tie directly into the media history of samurai cinema. Pete was almost certainly imitating the action-packed samurai cinema films that were popular after WWII. And, in fact, most samurai cinema was set during the Tokugawa/Edo Period--exactly when the Honjō Masamune was crafted. You can find a list of some seminal works of Samurai Cinema from The Criterion Collection.

It's interesting that the episode focused on a Masamune being given as a gift to a US president after WWII, because a Masamune was actually given to President Harry S. Truman after WWII and currently resides in the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum. That's a pretty direct allegory to a sword being given to Woodrow Wilson and residing in the Woodrow Wilson Museum of Peace.

Incidentally, there is no actual Woodrow Wilson Museum of Peace, but there is a Woodrow Wilson Presidential Library and Museum, and it is (at least partially) a house!

And since the episode got to the Honjō Masamune pretty quickly and led to an early introduction of our expert in the podcast, let's give her the same treatment here in the show notes! We are so grateful and honored to have had the highly illuminating Dr. Nyri Bakkalian as our Artifact Expert this week. She shed so much light onto a subject that I have just…no other knowledge of whatsoever. It was fascinating to hear all she had to say about the Honjō Masamune and about Japanese swords post WWII more broadly. You can find her on Twitter as @riversidewings, check out her blog, or support her on her Patreon for more information.

Dr. Nyri Bakkalian shared a cringe-worthy story of someone who stripped a samurai sword to the tang. If you know nothing about swords (like me) then you probably didn't know what a tang was--or that there are so many more parts of a blade than the hilt, tsuba, and that long stabby bit. For my fellow sword novices, here's some info on the anatomy of a sword. Here's some information specifically on Japanese swords. And here's some information specifically on tsubas and other Japanese sword mountings.

But guess what?!

Dr. Bakkalian was kind enough to give us even more information after Miranda's interview. She sent us a link to a Japanese resource that discusses the real Honjō Masamune--and that even includes a diagram of the sword itself. Dr. Bakkalian added that "the sword was appraised many times, but it was designated a National Treasure of Japan in 1939, so we're fortunate that we at least have a paper trail if not the blade itself."