#alaskan archipelago

Text

youtube

0 notes

Note

Oh hey we're "neighbors"! My irl best friend is an Alexander too and I'm an Alaskan Timber from the Tongass area. :)

hiii neighbor!!! its nice to hear from another wolf friend here, tell your friend i said hello too!!! :D 🐾

#therian#therians#therianthropy#therian wolf#wolf therian#wolf therians#canine therian#alexander archipelago wolf therian#archipelago wolf therian#alaskan timber wolf therian#nonhuman#non human#otherkin#wolf kin#canine kin#alterhuman#alter human

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Mockingbirds Song |Chapter 1|

Pairing: Hybrid!Taehyung x Hybrid!F!Reader

Chapter warnings: nothing really :)

Summary: You had fled from your old home, your old owner, your old life in hopes you’ll find a better one. You ran as far as you could, as much as you could, until you couldn’t. Left for dead, you have no hopes you’ll make it to see the light of the morning.

Genre: angst, fluff…

Word count: 1k

Hybrid types: Reader: Omega!Red wolf, Namjoon: Alpha!Eurasian wolf, Yoongi: Omega!Alaskan Tundra wolf,Hoseok: Alpha!Steppe wolf Jin: Beta!Great Plains wolf, Jimin: Omega!Northwestern wolf Jungkook: Beta!Arctic wolf, Taehyung: Alpha!Alexander archipelago wolf

A/n: I’m really excited to start this series, like I have a feeling it’s actually going to be a good series 😁

I recommend reading the teaser first, as it is more so a intro to the story than it is a teaser!

Credit to @cafekitsune for the dividers!

Next - Masterlist

You whimper, your body feels so stiff. You hear muffled voices, yet you can’t bring yourself to open your eyes. Your mind is running a mile a minute, screaming at you to Get up! but you can’t find it in you to. You attempt to shift onto your side—wait, your side? You didn’t black out on your back. You jolt upright, wincing at the pain that courses through you. Your gaze lands on seven bodies all watching you intently.

You whimper, backing up against the couch. “Hey hey hey, no no we’re not gonna hurt you. We’re hybrids too.” At the man’s words your gaze flickers to the tops of all their heads. They are. “We found you in the woods..well I should say Taehyung found you and brought you back here.” You look at the man that’s gestured too. He’s watching you closely, brows furrowed with a small pout tugging at his lips.

“T-thank you for taking me here but…why did you?” You ask, your voice a bit hoarse from disuse. “Well you didn’t look very good, your neck had slight bruising on it, and your body just..” The man, now known as Taehyung, trails off, his concerned eyes never once leaving your form. “What were you doing out in the woods?” Another voice speaks up. You turn your head to the source, finding cold eyes boring into yours.

You swallow nervously, gaze lowering to your lap to avoid the man’s. “I-I ran away..” You mumble, playing with your fingers. “From what?” The man asks again. You consider not responding, frowning as you mull over what to do. “You don’t have to say anything. The important thing is you're safe now.” Another man speaks up, reaching out and putting a reassuring hand on yours.

You flinch, a small, barely there flinch yet the man quickly takes his hand back. “Sorry..” You mumble, relaxing back into the couch as best as you can. “No no, don’t apologize.” You look up to see a frown on the man’s face. You quickly look back down, fiddling with your hands. You bring your tail into your lap, gently combing your fingers through it as you press your ears to your head, a form of comfort for you.

“What kind of hybrid are you?” One of the men speaks up, earning a smack from another. “Kook!” One of the men whisper harshly. “I-I’m a red wolf..” You mumble, keeping your eyes firmly planted on your fingers working out the small tangles in your tail. You hear a small gasp from someone, “Like the really rare one?” You nod, nibbling on your bottom lip. “Coolio!” One of them say, jumping up from the floor making you look up.

“I’m an arctic wolf.” The man says, sitting by you on the couch with a wide smile. You look up at him, giving him a small smile in return. You haven’t met another wolf in years. “I’m Jungkook.” He says, extending a hand in your direction. You take it hesitantly, giving it a weak shake before letting go. He starts to point at the men on the floor, “That’s Jimin, that’s Jin, that’s Namjoon, that’s Yoongi, that’s Hobi, and that’s Taehyung.” You follow Jungkook’s finger over all the men, doing your best to match the names with faces in your head.

They all give you a small, little awkward wave with a small smile. You give them all a smile, “Thank you all for helping me, but how do I get out of here?” You ask, regretting your question when you see some of their faces fall ever so slightly, the sour change in their scents becoming more and more prominent. “I, uhm, can show you.” One of the men, Jin says as he gets up. You nod, standing up from the couch.

You wince, struggling to keep your balance when one of the men, Taehyung, reaches out, steadying you. “I don’t think you should go yet. You can hardly stand.” Taehyung says, holding you gently by your forearms. Your legs wobble and you wince as you move to take a step. “I-I’m fine.” You mumble, attempting to move closer to Jin. Taehyung hesitantly lets you go, hovering nearby.

You move to take another step and lose your balance, pinching your eyes shut as you wait to make contact with the ground. You open your eyes when you don’t, feeling yourself being pressed against a chest before you’re moved back to the couch. “Yeah, sorry but you're not leaving. At Least not until you can walk properly again.” Taehyung says, sitting on the floor in front of you.

You nod, looking down at your lap. “Are you hungry?” You look up at the voice, about to deny when your stomach betrays you. You look away, flustered, as the man laughs. “I’ll take that as a yes.” The man says before walking away. “What happened to you? I know you said you’d run away but..” Taehyung asks, his concerned eyes foaming over your form.

“I uh..I fell.” You mumble. It isn’t a complete lie, but it’s not the full truth either. “And your neck?” Taehyung asks, his eyes flitting down to your bruised skin. You press your ears to your head, combing your fingers through your tail. “I um…it was the fall?” You mumble, nervously looking up at Taehyung. He frowns, eyeing your neck. “Weird. They look like hand prints.” He mumbles, pursing his lips. You avert your eyes to your tail laying in your lap, pursing your lips as tears cloud your vision.

“Did you..did you have an abusive owner?” Taehyung mumbles, tilting his head to try and catch your gaze. You bite back a sob, a single tear slipping down your cheek. “Hey hey hey..it’s okay. They can’t reach you now.” Taehyung mumbles, his brows furrowing. At this the sob escapes you, making you curl in on yourself. You miss the concerned glances the men in front of you exchange, all of them eyeing your shaking figure worriedly.

“Is she okay? I heard a sob.” The man who’d previously left the room returns, a frying pan in hand as he eyes everyone. Taehyung sighs, sparing you one last glance before standing up and leading the man out of the room.

Next - Masterlist

A/n: I’m sorry it’s a short chapter, but I made like a mini drabble type of chapter with Tae talking to Jin in the kitchen.

If anyone would like to be on a taglist for this series please let me know!

58 notes

·

View notes

Photo

TTB!Sunstreaker’s character sheet is ALMOST DONE and I’m working through a commission, but this damn game has been eating at my brainmeats for weeks at this point so y’all gonna have to deal while this blog also becomes a Tara/Westley stan account :’3

Narrativewise, this hairy fuzzball has never explained where or how he was ‘turned’ into a werewolf or why he’s estranged from his brother, so that leaves a bitch to fill in the blanks with her own headcanons (in which he used to be a bookish professor sort who was documenting Kodiak Russian---a dying Alaskan dialect---and the oral history of its remaining speakers, and was attempting to intervene on the acquisition of logging land on Prince of Wales Island on their behalf. When his older brother, the head of a logging crew, crumbles to pressure and attempts to chase out a pack endangered Alexander Archipelago wolves from the area which ends up in the accidental death of one of the animals, a werewolf living among the pack who has forsaken the human world decides to exact her revenge, except Westley gets in the way of that)

Also if you love cozy games with great story and diverse characters, for real, hit up Wylde Flowers. That it’s fully voice-acted (and voice-acted WELL) is a def plus, and I’m ready to listen to 7864623555 audiobooks narrated by Ray Chase (Westley’s VA).

348 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m so glad I finally discovered which wolf species I am a while ago, I wanted to share a few facts about it! I am an Alexander Archipelago Wolf.

The Alexander Archipelago Wolf, also known as the Islands Wolf, is a genetically distinct coastal subspecies of Grey Wolf found in the southeast Alaskan islands commonly known as the Alexander Archipelago. Their habitat is dense, undeveloped forest with an abundance of wildlife for food sources. Old-growth forest is also critical to providing proper wolf denning sites. Eighty percent of the wolves' habitat is within the boundaries of the Tongass National Forest.

Typically dark grey, black, or brown with short coarse fur, these wolves are known to primarily feed on Sitka black-tailed deer and salmon, but will also eat beaver, mountain goats, moose. They feed opportunistically on harbor seals, mustelids, small mammals, birds, and even marine invertebrates. They are around 2 feet tall, 3.5 feet in length, and usually weigh between 30-50 pounds, which is smaller than most wolves.

An official memorandum issued by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game estimated the population to number only 89 wolves in the fall of 2014, down from 221 the prior year — although the number could be as low as 50. Female wolves were said to have been particularly hard-hit; data in the report show that, as of fall 2014, only 7 to 32 females were left. That being said, Alexander Archipelago wolves are considered to be one of the rarest wolf species in the world.

#staring#type2#other tags:#clinical lycanthropy#nonhuman#wolf#alexander archipelago wolf#island wolf#coastal wolf#photos#facts#nature#therian#wolf therian#wolfkin#otherkin#otherkith#kith#wolfkith#endel#kin#canine#caninekin#canine therian

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

This story originally appeared in Hakai Magazine, an online publication about science and society in coastal ecosystems, and is part of the Climate Desk collaboration. It was published in collaboration with Earth Island Journal.

The floatplane bobs at the dock, its wing tips leaking fuel. I try not to take that as a sign that my trip to Chirikof Island is ill-fated. Bad weather, rough seas, geographical isolation—visiting Chirikof is forever an iffy adventure.

A remote island in the Gulf of Alaska, Chirikof is about the size of two Manhattans. It lies roughly 130 kilometers southwest of Kodiak Island, where I am waiting in the largest town, technically a city, named Kodiak. The city is a hub for fishing and hunting, and for tourists who’ve come to see one of the world’s largest land carnivores, the omnivorous brown bears that roam the archipelago. Chirikof has no bears or people, though; it has cattle.

At last count, over 2,000 cows and bulls roam Chirikof, one of many islands within a US wildlife refuge. Depending on whom you ask, the cattle are everything from unwelcome invasive megafauna to rightful heirs of a place this domesticated species has inhabited for 200 years, perhaps more. Whether they stay or go probably comes down to human emotions, not evidence.

Russians brought cattle to Chirikof and other islands in the Kodiak Archipelago to establish an agricultural colony, leaving cows and bulls behind when they sold Alaska to the United States in 1867. But the progenitor of cattle ranching in the archipelago is Jack McCord, an Iowa farm boy and consummate salesman who struck gold in Alaska and landed on Kodiak in the 1920s. He heard about feral cattle grazing Chirikof and other islands, and sensed an opportunity. But once he’d bought the Chirikof herd from a company that held rights to it, he got wind that the federal government was going to declare the cattle wild and assume control of them. McCord went into overdrive.

In 1927, he successfully lobbied the US Congress—with help from politicians in the American West—to create legislation that enshrined the right of privately owned livestock to graze public lands. What McCord set in motion reverberates in US cattle country today, where conflicts over land use have led to armed standoffs and death.

McCord introduced new bulls to balance the herd and inject fresh genes into the pool, but he soon lost control of his cattle. By early 1939, he still had 1,500 feral cattle—too many for him to handle and far too many bulls. Stormy, unpredictable weather deterred most of the hunters McCord turned to for help thinning the herd, though he eventually wrangled five men foolhardy enough to bet against the weather gods. They lost. The expedition failed, precipitated one of McCord’s divorces, and almost killed him. In 1950, he gave up. But his story played out on Chirikof over and over for the next half-century, with various actors making similarly irrational decisions, caught up in the delusion that the frontier would make them rich.

By 1980, the government had created the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge (Alaska Maritime for short), a federally protected area roughly the size of New Jersey, and charged the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) with managing it. This meant preserving the natural habitat and dealing with the introduced and invasive species. Foxes? Practically annihilated. Bunnies? Gone. But when it came to cattle?

Alaskans became emotional. “Let’s leave one island in Alaska for the cattle,” Governor Frank Murkowski said in 2003. Thirteen years later, at the behest of his daughter, Alaska’s senior senator, Lisa Murkowski, the US Congress directed the USFWS to leave the cattle alone.

So I’d been wondering: What are those cattle up to on Chirikof?

On the surface, Alaska as a whole appears an odd choice for cattle: mountainous, snowy, far from lucrative markets. But we’re here in June, summer solstice 2022, at “peak green,” when the archipelago oozes a lushness I associate with coastal British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest. The islands rest closer to the gentle climate of those coasts than to the northern outposts they skirt. So, in the aspirational culture that Alaska has always embraced, why not cattle?

“Why not cattle” is perhaps the mantra of every rancher everywhere, to the detriment of native plants and animals. But Chirikof, in some ways, was more rational rangeland than where many of McCord’s ranching comrades grazed their herds—on Kodiak Island, where cattle provided the gift of brisket to the Kodiak brown bear. Ranchers battled the bears for decades in a one-sided war. From 1953 to 1963, they killed about 200 bears, often from the air with rifles fixed to the top of a plane, sometimes shooting bears far from ranches in areas where cattle roamed unfenced.

Bears and cattle cannot coexist. It was either protect bears or lose them, and on Kodiak, bear advocates pushed hard. Cattle are, in part, the reason the Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge exists. Big, charismatic bears outshone the cows and bulls; bear protection prevailed. Likewise, one of the reasons the Alaska Maritime exists—sweeping from the Inside Passage to the Aleutian chain and on up to the islands in the Chukchi Sea—is to protect seabirds and other migratory birds. A cattle-free Chirikof, with its generally flat topography and lack of predators, would offer more quality habitat for burrow-nesting tufted puffins, storm petrels, and other seabirds. And yet, on Chirikof, and a few other islands, cows apparently outshine birds.

The remoteness, physically good for birds, works against them, too: Most people can picture a Ferdinand the Bull frolicking through the cotton grass, but not birds building nests. Chirikof is so far from other islands in the archipelago that it’s usually included as an inset on paper maps. A sample sentence for those learning the Alutiiq language states the obvious: Ukamuk (Chirikof) yaqsigtuq (is far from here). At least one Chirikof rancher recommended the island as a penal colony for juvenile delinquents. To get to Chirikof from Kodiak, you need a ship or a floatplane carrying extra fuel for the four-hour round trip. It’s a wonder anyone thought grazing cattle on pasture at the outer edge of a floatplane’s fuel supply was a good idea.

Patrick Saltonstall, a cheerful, fit 57-year-old with a head of tousled gray curls, is an archaeologist with the Alutiiq Museum in Kodiak. He’s accompanying photographer Shanna Baker and me to Chirikof—but he’s left us on the dock while he checks in at the veterinarian’s where he has taken his sick dog, a lab named Brewster.

The owners of the floatplane, Jo Murphy and her husband, pilot Rolan Ruoss, are debating next steps, using buckets to catch the fuel seeping from both wing tips. Weather is the variable I had feared; in the North it’s a capricious god, swinging from affable to irascible for reasons unpredictable and unknowable. But the weather is perfect this morning. Now, I’m fearing O-rings.

Our 8 am departure ticks by. Baker and I grab empty red plastic jerrycans from a pickup truck and haul them to the dock. The crew empties the fuel from the buckets into the red jugs. This will take a while.

A fuel leak, plus a sick dog: Are these omens? But such things are emotional and irrational. I channel my inner engineer: Failing O-rings are a common problem, and we’re not in the air, so it’s all good.

Saltonstall returns, minus his usual smile: Brewster has died.

Dammit.

He sighs, shakes his head, and mumbles his bewilderment and sadness. Brewster’s death apparently mystified the vet, too. Baker and I murmur our condolences. We wait in silence awhile, gazing at distant snowy peaks and the occasional seal peeking its head above water. Eventually, we distract Saltonstall by getting him talking about Chirikof.

Cattle alone on an island can ruin it, he says. They’re “pretty much hell on archaeological sites,” grazing vegetation down to nubs, digging into the dirt with their hooves, and, as creatures of habit, stomping along familiar routes, fissuring shorelines so that the earth falls away into the sea. Saltonstall falls silent. Brewster is foremost on his mind. He eventually wanders over to see what’s up with the plane.

I lie on a picnic table in the sun, double-check my pack, think about birds. There is no baseline data for Chirikof prior to the introduction of cattle and foxes. But based on the reality of other islands in the refuge, it has a mix of good bird habitats. Catherine West, an archaeologist at Boston University in Massachusetts, studies Chirikof’s animal life from before the introduction of cows and foxes; she has been telling me that the island was likely once habitat for far more birds than we see today: murres, auklets, puffins, kittiwakes and other gulls, along with ducks and geese.

I flip through my notes to what I scrawled while walking a Kodiak Island trail through Sitka spruce with retired wildlife biologist Larry Van Daele. Van Daele worked for the State of Alaska for 34 years, and once retired, sat for five years on the Alaska Board of Game, which gave him plenty of time to sit through raucous town hall meetings pitting Kodiak locals against USFWS officials. Culling ungulates—reindeer and cattle—from islands in the refuge has never gone down well with locals. But change is possible. Van Daele also witnessed the massive cultural shift regarding the bear—from “If it’s brown, it’s down” to it being an economic icon of the island. Now, ursine primacy is on display on the cover of the official visitor guide for the archipelago: a photo of a mother bear, her feet planted in a muddy riverbank, water droplets clinging to her fur, fish blood smearing her nose.

But Chirikof, remember, is different. No bears. Van Daele visited several times for assessments before the refuge eradicated foxes. His first trip, in 1999, followed a long, cold winter. His aerial census counted 600 to 800 live cattle and 200 to 250 dead, their hair and hide in place and less than 30 percent of them scavenged. “The foxes were really looking fat,” he told me, adding that some foxes were living inside the carcasses. The cattle had likely died of starvation. Without predators, they rise and fall with good winters and bad.

The shape of the island summarizes the controversy, Van Daele likes to say—a T-bone steak to ranchers and a teardrop to bird biologists and Indigenous people who once claimed the island. In 2013, when refuge officials began soliciting public input over what to do with feral animals in the Alaska Maritime, locals reacted negatively during the three-year process. They resentfully recalled animal culls elsewhere and argued to preserve the genetic heritage of the Chirikof cattle. Van Daele, who has been described as “pro-cow,” seems to me, more than anything, resistant to top-down edicts. As a wildlife biologist, he sees the cattle as probably invasive and acknowledges that living free as a cow is costly. An unmanaged herd has too many bulls. Trappers on Chirikof have witnessed up to a dozen bulls at a time pursuing and mounting cows, causing injury, exhaustion, and death, especially to heifers. It’s not unreasonable to imagine a 1,000-kilogram bull crushing a heifer weighing less than half that.

But, as an Alaskan and a former member of the state’s Board of Game, Van Daele chafes at the federal government’s control. Senator Murkowski, after all, was following the lead of her constituents, at least the most vocal of them, when she pushed to leave the cattle free to roam. Once Congress acted, Van Daele told me, “why not find the money, spend the money, and manage the herd in a way that allows them to continue to be a unique variety, whatever it is?” “Whatever it is” turns out to be not much at all.

Finally, Ruoss beckons us to the plane, a de Havilland Canada Beaver, a heroically hard-working animal, well adapted for wandering the bush of a remote coast. He has solved the leaking problem by carrying extra fuel onboard in jerrycans, leaving the wing tips empty. At 12:36 pm, we take off for Chirikof.

Imagine Fred Rogers as a bush pilot in Alaska. That’s Ruoss: reassuring, unflappable, and keen to share his archipelago neighborhood. By the time we’re angling up off the water, my angst—over portents of dead dog and dripping fuel—has evaporated.

A transplant from Seattle, Washington, Ruoss was a herring spotter as a young pilot in 1979. Today, he mostly transports hunters, bear-viewers, and scientists conducting fieldwork. He takes goat hunters to remote clifftops, for example, sussing out the terrain and counting to around seven as he flies over a lake at 100 miles per hour (160 kilometers per hour) to determine if the watery landing strip is long enough for the Beaver.

From above, our world is equal parts land and water. We fly over carpets of lupine and pushki (cow parsnip), and, on Sitkinak Island, only 15 kilometers south of Kodiak Island, a cattle herd managed by a private company with a grazing lease. Ruoss and Saltonstall point out landmarks: Refuge Rock, where Alutiiq people once waited out raids by neighboring tribes but couldn’t repel an attack from Russian cannons; a 4,500-year-old archaeology site with long slate bayonets; kilns where Russians baked bricks for export to California; an estuary where a tsunami destroyed a cannery; the village of Russian Harbor, abandoned in the 1930s. “People were [living] in every bay” in the archipelago, Ruoss says. He pulls a book about local plant life from under his seat and flips through it before handing it over the seat to me.

Today, the only people we see are in boats, fishing for Dungeness crab and salmon. We fly over Tugidak Island, where Ruoss and Murphy have a cabin. The next landmass will be Chirikof. We have another 25 minutes to go, with only whitecaps below.

For thousands of years, the Alutiiq routinely navigated this rough sea around their home on Chirikof, where they wove beach rye and collected amber and hunted sea lions, paddling qayat—kayaks. Fog was a hazard; it descends rapidly here, like a ghostly footstep. When Alutiiq paddlers set off from Chirikof, they would tie a bull kelp rope to shore as a guide back to safety if mist suddenly blocked their vision.

As we angle toward Chirikof, sure enough, a mist begins to form. But like the leaking fuel or Brewster’s death, it foreshadows nothing. Below us, as the haze dissipates, the island gleams green, a swath of velveteen shaped, to my mind, like nothing more symbolic than the webbed foot of a goose. A bunch of spooked cows gallop before us as we descend over the northeast side. Ruoss lands on a lake plenty long for a taxiing Beaver.

We toss out our gear and he’s off. We’re the only humans on what appears to be a storybook island—until you kick up fecal dust from a dry cow pie, and then more, and more, and you find yourself stumbling over bovid femurs, ribs, and skulls. Cattle prefer grazing a flat landscape, so stick to the coastline and to the even terrain inland. We tromp northward, flushing sandpipers from the verdant carpet. A peppery bouquet floats on the still air. A cabbagey scent of yarrow dominates whiffs of sedges and grasses, wild geraniums and flag irises, buttercups and chocolate lilies.

Since the end of the last ice age, Chirikof has been mostly tundra-like: no trees, sparse low brush, tall grasses, and boggy. Until the cattle arrived, the island never had large terrestrial mammals, the kind of grazers and browsers that mold a landscape—mammoths, mastodons, deer, caribou. But bovids have fashioned a pastoral landscape that a hiker would recognize in crossing northern England, a place that cows and sheep have kept clear for centuries. The going is easy, but Baker and I struggle to keep pace with the galloping Saltonstall, and we can’t help but stop to gape at bull and cow skeletons splayed across the grasses. We skirt a ground nest with three speckled eggs, barely hidden by the low scrub. We cut across a beach muddled with plastics—ropes, bottles, floats—and reach a giant puddle with indefinable edges, its water meandering toward the sea. “We call it the river Styx,” Saltonstall says. “The one you cross into hell.”

Compared with the Emerald City behind us, the underworld across the Styx is a Kansas dust bowl, a sandy mess that looks as if it could swallow us. Saltonstall tells us about a previous trip when he and his colleagues pulled a cow out of quicksand. Twice. “It charged us—and we’d saved its life!”

Hoof prints scatter from the river. At one time, the river Styx probably supported a small pink salmon run. A team of biologists reported in 2016 that several Chirikof streams host pink and coho, with cameo appearances of rainbow trout and steelhead. This stream is likely fish-free, the erosion too corrosive, a habitat routinely trampled.

Two raptors—jaegers—cavort above us. A smaller bird’s entrails unspool at our feet. On a sandy bluff, Saltonstall pauses to look for artifacts while Baker and I climb down to a beach where hungry cattle probably eat seaweed in winter. We follow a ground squirrel’s tracks up the bluff to its burrow, and at the top meet Saltonstall, who holds out his hands: stone tools. Artifacts sprinkle the surface as if someone has shaken out a tablecloth laden with forks, knives, spoons, and plates—an archaeological site with context ajumble. A lone bovid’s track crosses the sand, winding through shoulder blades, ribs, and the femoral belongings of relatives.

After four hours of hiking, we turn toward the lake where we left our gear. So far on this hike, dead cattle outnumber live ones, dozens to zero. But wait! What’s that? A bull appears on a rise, across a welcome mat of cotton grass. Curious, he jogs down. Baker and Saltonstall peer through viewfinders and click off images. The bull stops several meters away; we stare at each other. He wins. We turn and walk away. When I look back, he’s still paused, watching us, or—I glance around—watching a distant herd running at us.

Again, my calm comrades-in-arms lift their cameras. I lift my iPhone, which shakes because I’m scared. Should I have my hands on the pepper spray I borrowed from Ruoss and Murphy? Closer, closer, closer they thunder, until I can’t tell the difference between my pounding heart and their pounding feet. Then, in sync, the herd turns 90 degrees and gallops out of the frame. The bull lollops away to join them. Their cattle plans take them elsewhere.

Saltonstall has surveyed archaeology sites three times on Chirikof. The first time, in 2005, he carried a gun to hunt the cattle, but his colleagues were also apprehensive about the feral beasts. At least one person I talked to suggested we bring a gun. But Saltonstall says he learned that cattle are cowards: Stand your ground, clap, and cows and bulls will run away. But to me, big domesticated herbivores are terrifying. Horses kick and bite, cattle can crush you. The rules of bears—happier without humans around—are easier to parse. I’ve never come close to pepper spraying a bear, but I’m hot on the trigger when it comes to cattle.

The next morning, we set out for the Old Ranch, one of the two homesteads built decades ago on the island and about a three-hour amble one way. Ruoss won’t be picking us up till 3 pm, so we have plenty of time. The cattle path we’re following crosses a field bejeweled with floral ambers, opals, rubies, sapphires, amethysts, and shades of jade. It’s alive with least sandpipers, a shorebird that breeds in northern North America, with the males arriving early, establishing their territories, and building nests for their mates. The least sandpiper population, in general, is in good shape—they certainly flourish here. High-pitched, sped-up laughs split the air. They slice the wind and rush across the velvet expanse. Their flapping wings look impossibly short for supporting flights from their southern wintering grounds, sometimes as far away as Mexico, over 3,000 kilometers distant. They flutter into a tangle of green and vanish.

From a small rise, we spot cattle paths meandering into the distance, forking again and again. Saltonstall announces the presence of the only other mammal on the island. “A battery killer,” he says, raising his camera at an Arctic ground squirrel, and he’s right. They are adorable. They stand on two legs and hold their food in their hands. To us humans, that makes them cute. Pretty soon, we’re all running down the batteries on our cameras and smartphones.

Qanganaq is Alutiiq for ground squirrel. An Alutiiq tailor needed around 100 ground squirrels for one parka, more precious than a sea otter cloak. Some evidence suggests the Alutiiq introduced ground squirrels to Chirikof at least 2,000 years ago, apparently a more rational investment than cattle. Squirrels were easily transported, and the market for skins was local. Still, they were fancy dress, Dehrich Chya, the Alutiiq Museum’s Alutiiq language and living culture manager, told me. Creating a parka—from hunting to sewing to wearing—was an homage to the animals that offered their lives to the Alutiiq. Archaeologist Catherine West and her crew have collected over 20,000 squirrel bones from Chirikof middens, a few marked by tool use and many burned.

Chirikof has been occupied and abandoned periodically—the Alutiiq quit the island, perhaps triggered by a volcanic eruption 4,000 years ago, then came people more related to the Aleuts from the west, then the Alutiiq again. Then, Russian colonizers arrived. The Russians lasted not much longer than the American cattle ranchers who would succeed them. That last, doomed culture crumbled in less than 100 years, pegged to an animal hard to transport, with a market far, far away.

Whether ground squirrels, some populations definitely introduced, should be in the Alaska Maritime is rarely discussed. One reason, probably, is that they are small and cute and easy to anthropomorphize. There is a great body of literature on why we anthropomorphize. Evolutionarily, cognitive archaeologists would argue that once we could anthropomorphize—by at least 40,000 years ago—we became better hunters and eventually herders. We better understood our prey and the animals we domesticated. Whatever the reason, researchers tend to agree that to anthropomorphize is a universal human behavior with profound implications for how we treat animals. We attribute humanness based on animals’ appearance, familiarity, and non-physical traits, such as agreeability and sociality—all factors that will vary somewhat across cultures—and we favor those we humanize.

Ungulates, in general, come across favorably. Add a layer of domestication, and cattle become even more familiar. Cows, especially dairy cows named Daisy, can be sweet and agreeable. Steve Ebbert, a retired USFWS wildlife biologist living on the Alaska mainland outside Homer, eradicated foxes, as well as rabbits and marmots, from islands in the refuge. Few objected to eliminating foxes—or even the rabbits and marmots, he told me. Cattle are more complicated. Humans are supposed to take care of them, he said, not shoot them or let them starve and die: they’re for food—and of course, they’re large, and they’re in a lot of storybooks, and they have big eyes. Alaskans, like many US westerners, are also protective of the state’s ranching legacy—cattle ranchers transformed the landscape to a more familiar place for colonizers and created an American story of triumph, leaving out the messy bits.

We spot a herd of mostly cows and calves, picture-book perfect, with chestnut coats and white faces and socks. We edge closer, but they’re wary. They trot away.

Saltonstall, always a few leaps and bounds ahead, spots the Old Ranch—or part of it. A couple of bulls are hanging out near the sagging, severed rooms that cling to a cliff above the sea, refusing their fate. Ghostly fence posts march from the beach across a rolling landscape.

Close by is a wire exclosure, one of five Ebbert and his colleagues set up in 2016. The exclosure—big enough to park a quad—keeps out cattle, allowing an unaggravated patch of land to regenerate. Beach rye taller than cows soars within the fencing. This is what the island looks like without cattle: a haven for ground-nesting birds. The Alutiiq relied on beach rye, weaving the fiber into house thatching, baskets, socks, and other textiles; if they introduced ground squirrels, they knew what they were doing, since the rodents didn’t drastically alter the vegetation the way cattle do.

Saltonstall approaches a shed set back from the eroding cliff.

“Holy cow!” he hollers. No irony. He is peering into the shed.

On the floor, a cow’s head resembles a Halloween mask, horns up, eye sockets facing the door, snout resting close to what looks like a rusted engine. Half the head is bone, half is covered with hide and keratin. Femurs and ribs and backbone scatter the floor, amid bits and bobs of machinery. One day, for reasons unknown, this cow wedged herself into an old shed and died.

Cattle loom large in death, their bodies lingering. Their suffering—whether or not by human hands—is tangible. Through size, domestication, and ubiquity, they take up a disproportionate amount of space physically, and through anthropomorphism, they grab a disproportionate amount of human imagination and emotion. When Frank Murkowski said Alaska should leave one island to the cattle, he probably pictured a happy herd rambling a vast, unfenced pasture—not an island full of bones or heifer-buckling bulls.

Birds are free, but they’re different. They vanish. We rarely witness their suffering, especially the birds we never see at backyard feeders—shorebirds and seabirds. We witness their freedom in fleeting moments, if at all, and when we do see them—gliding across a beach, sipping slime from an intertidal mudflat, resting on a boat rail far from shore—can we name the species? As popular as birding is, the world is full of non-birders. And so, we mistreat them. On Chirikof, where there should be storm petrels, puffins, and terns, there are cattle hoof prints, cattle plops, and cattle bones.

Hustling back to meet the seaplane, we skirt an area thick with cotton grass and ringed by small hills. In 2013, an ornithologist recorded six Aleutian terns and identified one nest with two eggs. In the United States, Aleutian tern populations have crashed by 80 percent in the past few decades. The tern is probably the most imperiled seabird in Alaska. But eradicating foxes, which ate birds’ eggs and babies, probably helped Chirikof’s avian citizens, perhaps most notably the terns. From a distance, we count dozens of birds, shooting up from the grass, swirling around the sky, and fluttering back down to their nests.

Terns may be dipping their webbed toes into a bad situation, but consider the other seabirds shooting their little bodies through the atmosphere, spotting specks of land in the middle of the Pacific Ocean to raise their young, and yet it’s unsafe for them on this big, lovely island. The outcry over a few hundred feral cattle—a loss that would have absolutely no effect on the species worldwide—seems completely irrational. Emotional. A case of maladaptive anthropomorphism. If a species’ purpose is to proliferate, cattle took advantage of their association with humans and won the genetic lottery.

Back at camp, we haul our gear to the lake. Ruoss arrives slightly early, and while he’s emptying red jerrycans of fuel into the Beaver, we grab tents and packs and haul them into the pontoons. Visibility today is even better than yesterday. I watch the teardrop-shaped island recede, thinking of what more than one scientist told me: when you’re on Chirikof, it’s so isolated, surrounded by whitecaps, that you hope only to get home. But as soon as you leave, you want to go back.

Chirikof cattle are one of many herds people have sprinkled around the world in surprising and questionable places. And cattle have a tendency to go feral. On uninhabited Amsterdam Island in the Indian Ocean, the French deposited a herd that performed an evolutionary trick in response to the constraints of island living: the size of individuals shrank in the course of 117 years, squashing albatross colonies in the process. In Hong Kong, feral cattle plunder vegetable plots, disturb traffic, and trample the landscape. During the colonization of the Americas and the Caribbean, cattle came to occupy spaces violently emptied of Indigenous people. Herds ran wild—on small islands like Puerto Rico and across expanses in Texas and Panama—pulverizing landscapes that had been cultivated for thousands of years. No question: cattle are problem animals.

A few genetic studies explore the uniqueness of Chirikof cattle. Like freedom, “unique” is a vague word. I sent the studies to a scientist who researches the genetics of hybrid species to confirm my takeaway: the cattle are hybrids, perhaps unusual hybrids, some Brown Swiss ancestry but mostly British Hereford and Russian Yakutian, an endangered breed. The latter are cold tolerant, but no study shows selective forces at play. The cattle are not genetically distinct; they’re a mix of breeds, the way a labradoodle is a mix of a Labrador and a poodle.

Feral cattle graze unusual niches all over the world, and maybe some are precious genetic outliers. But the argument touted by livestock conservancies and locals that we need Chirikof cattle genes as a safeguard against some future fatal cattle disease rings hollow. And if we did, we might plan and prepare: freeze some eggs and sperm.

Cattle live feral lives elsewhere in the Alaska Maritime, too, on islands shared by the refuge and Indigenous owners or, in the case of Sitkinak Island, where a meat company grazes cattle. Why Frank Murkowski singled out Chirikof is puzzling: Alaska will probably always have feral cattle. Chirikof cattle, of use to practically no one, fully residing within a wildlife refuge a federal agency is charged with protecting for birds, with no concept of the human drama swirling around their presence, have their own agenda for keeping themselves alive. Unwittingly, humans are part of the plan.

We created cattle by manipulating their wild cousins, aurochs, in Europe, Asia, and the Sahara beginning over 10,000 years ago. Unlike Frankenstein’s monster, who could never find a place in human society, cattle trotted into societies around the world, making themselves at home on most ranges they encountered. Rosa Ficek, an anthropologist at the University of Puerto Rico who has studied feral cattle, says they generally find their niche. Christopher Columbus brought them on his second voyage to the Caribbean in 1493, and they proliferated, like the kudzu of the feral animal world. “[Cattle are] never fully under the control of human projects,” she says. They’re not “taking orders the way military guys are … They have their own cattle plans.”

The larger question is, Why are we so nervous about losing cattle? In terms of sheer numbers, they’re a successful species. There is just over one cow or bull for every eight people in the world. If numbers translate to likes, we like cows and bulls more than dogs. If estimates are right, the world has 1.5 billion cattle and 700 million dogs. Imagine all the domesticated animals that would become feral if some apocalypse took out humans.

I could say something here about how vital seabirds—as opposed to cattle—are to marine ecosystems and the overall health of the planet. They spread their poop around the oceans, nurturing plankton, coral reefs, and seagrasses, which nurture small plankton-eating fishes, which are eaten by bigger fishes, and so on. Between 1950 and 2010, the world lost some 230 million seabirds, a decline of around 70 percent.

But maybe it’s better to end with conjuring the exquisiteness of seabirds like the Aleutian terns in their breeding plumage, with their white foreheads, black bars that run from black bill to black-capped heads, feathers in shades of grays, white rump and tail, and black legs. Flashy? No. Their breeding plumage is more timeless monochromatic, with the clean, classic lines of a vintage Givenchy design. The Audrey Hepburn of seabirds. They’re so pretty, so elegant, so difficult to appreciate as they flit across a cotton grass meadow. Their dainty bodies aren’t much longer than a typical ruler, from bill to tail, but their wingspans are over double that, and plenty strong to propel them, in spring, from their winter homes in Southeast Asia to Alaska and Siberia.

A good nesting experience, watching their eggs hatch and their chicks fledge, with plenty of fish to eat, will pull Aleutian terns back to the same places again and again and again—like a vacationing family, drawn back to a special island, a place so infused with good memories, they return again and again and again. That’s called fidelity.

Humans understand home, hard work, and family. So, for a moment, think about how Aleutian terns might feel after soaring over the Pacific Ocean for 16,000 kilometers with their compatriots, making pit stops to feed, and finally spotting a familiar place, a place we call Chirikof. They have plans, to breed and nest and lay eggs. The special place? The grassy cover is okay. But, safe nesting spots are hard to find: Massive creatures lumber about, and the terns have memories of loss, of squashed eggs, and kicked chicks. It’s sad, isn’t it?

This story was made possible in part by the Fund for Environmental Journalism and the Society of Environmental Journalists and was published in collaboration with Earth Island Journal.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Character Info Post

good-boy

---

Spotify ||| Pinterest ||| toyhou.se

____________________________________________

Name: good-boy (also dog! or good-dog)

Species: wolfdog

Pronouns: he/him

Occupation: dog

------------------------

good-dog is largely inspired by The Call of The Wild, White Fang, and Balto

He's a large all black wolfdog except for two white marks on his chest and one on his tail tip. He has very thick fur. His eyes are an icy silver-blue. He wears a bright red bandana.

His mother is an Alexander Archipelago Wolf and his father an Alaskan Noble Companion Dog (works as a sled dog) (both alive)

Caught in a hunters trap as a young pup and was given to the hunters daughter as a gift. She took care of him as best she could. She named him good-boy and gave him his signature red bandana.

Growing up he always longed to run into the wilderness never to return but his love for the hunters daughter kept him in place. That is until the hunter took him to a dog fighting ring where good-boy escaped into the snowy countryside.

Lost and confused he set out with no where in particular to go. Eventually he decides to find his parents. He meets his father on his travels but never learns who he is. He eventually finds his mothers pack and stays with them awhile.

But a dog such as him he just couldn't stay still forever. With wind in his fur and stars in his eyes he left to explore the world.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Illuminating the Aleutians

An astronaut aboard the International Space Station captured this photo of the Aleutian Islands off the coast of mainland Alaska. The archipelago is illuminated by moonglint—a phenomenon similar to sunglint that occurs only when the Moon’s light reflects from the water at a particular angle. Capturing moonglint is uncommon in astronaut photography.

While some archipelagos form from processes such as erosion and rising sea level, most island chains, including the Aleutians, are the result of volcanic eruptions. Occupying an area of about 6,800 square miles (17,611 square kilometers), the islands arc southwest then northwest for about 1,100 miles (1,800 kilometers) from the Alaskan Peninsula to Attu Island (not pictured). The Aleutian chain forms the boundary between the main body of the Pacific Ocean to the south and the Bering Sea to the north.

Notice the green light high in Earth’s atmosphere. This phenomenon is called the aurora borealis, also known as the northern lights. Massive bursts of energy from the Sun, such as solar flares and coronal mass ejections, can speed through space and sometimes impact Earth’s magnetic field. The interaction between the magnetic field and solar radiation causes the color display shown in the image. Auroras appear in different hues, from green and yellow to shades of purple and red. Auroras can also occur over the southern hemisphere, where they are known as the aurora australis (southern lights).

Astronaut photograph ISS067-E-363431 was acquired on September 17, 2022, with a Nikon D5 digital camera using a focal length of 28 millimeters. It is provided by the ISS Crew Earth Observations Facility and the Earth Science and Remote Sensing Unit, Johnson Space Center. The image was taken by a member of the Expedition 67 crew. The image has been cropped and enhanced to improve contrast, and lens artifacts have been removed. The International Space Station Program supports the laboratory as part of the ISS National Lab to help astronauts take pictures of Earth that will be of the greatest value to scientists and the public, and to make those images freely available on the Internet. Additional images taken by astronauts and cosmonauts can be viewed at the NASA/JSC Gateway to Astronaut Photography of Earth. Caption by Minna Adel Rubio, GeoControl Systems, JETS Contract at NASA-JSC.

2 notes

·

View notes

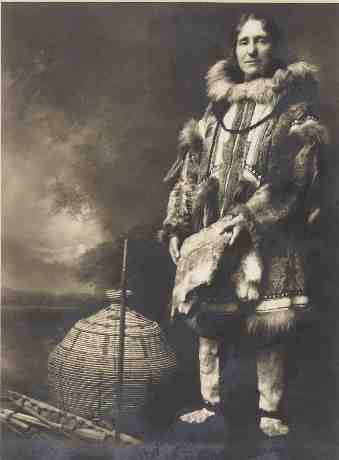

Photo

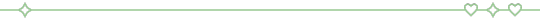

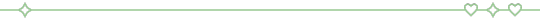

30th May 1889 saw the birth near Kirkliston of Isobel Wylie Hutchison.

Isobel Wylie Hutchison was an Arctic traveller during the 1920s and 1930s. She was also a botanist, a writer, a poet, an artist and speaker of numerous languages, so a bit of a polymath.

Carlowrie Castle a Scots baronial mansion was the comfortable upper-middle class home into which Isobel Wylie Hutchison was born in 1889. It was there her father, Thomas Hutchison, a successful wine merchant in Edinburgh, looked after his gardens, and passed on to Isobel his fascination for plants and his habit of meticulous note-taking. Although called a castle, Carlowrie was built between 1852 and 1855, so was never a defensive structure, but a luxurious home.

Isobel’s father, Thomas Hutchison, was a successful wine merchant in Edinburgh, he was a keen gardener and passed on to Isobel his fascination for plants and his habit of meticulous note-taking.

From 1917-18, she studied at an agricultural college, after which, she visited a number of countries around the Mediterranean region. But the sudden death or her father was subsequently followed by the loss of both her brothers. Isobel was left in a darkened place with a deeply grieving heart. Walking became her escape.

At a time when women were expected to stay at home, dressed in petticoats and tending to domestic duties, Isobel would often leave home for several days – much to the despair of her mother!

A Gaelic speaker, she had soon covered Scotland, including a trek from Blairgowrie to Fort Augustus, and began to look at bigger challenges. She wanted to spread her wings and fly away, and Iceland seemed like a good place to start.

Iceland, which she visited in 1925, was both a test and a revelation. She was told that she couldn’t walk the 260 miles north from Reykjavik to Akureyri because there were no maps, no guides, and it was far too dangerous. But she proved everyone wrong and then set her sights on another goal: Greenland.

By now, Isobel was making a name as a traveller in the Far North. She had written books about her experiences in both Iceland and Greenland. However, she hadn’t quite finished her Arctic adventures! She made arrangements to travel to Alaska and Northern Canada to explore and again, collect plant specimens. In May 1933, Isobel left Manchester and went by ship, riverboat, train and also plane, to reach Nome in Alaska.

Eventually, she arrived in Barrow, in the north of Alaska, where she transferred to another small vessel before the Arctic Ocean ice began closing in, making it impossible to travel any further. Isobel was forced to stay in a migrant Estonian’s hut for many weeks until the weather situation improved. Although her journey had come to a halt, it was an opportunity for her to visit local Inuit families, walk, travel by dog sled and stay in igloos. Eventually, she continued her Arctic trip with a 120-mile dog sled journey and crossed over into Canada. After many months in the Alaskan and Canadian Arctic she eventually returned to Scotland, having been away for around a year.

Unable to obtain permission from the Soviet authorities to visit Eastern Siberia, Isobel’s next northern journey was in 1936, to the Aleutian Islands, off the coast of Alaska. This thousand-mile long archipelago of both large and small volcanic islands draped like a gigantic necklace between Alaska and the Kamchatka Peninsula in the far east of the USSR. These islands were inhabited by Aleut people on treeless terrain and were exposed to continuous windy, foggy and stormy weather.

The Aleut people of the islands were able to live in such extreme conditions because they managed to catch a range of marine life. Fortunately, she was able to visit many of the inhabited islands by way of US government vessels. Invariably, landing on the islands involved negotiating heavy seas in wild conditions. However, when she did make land, she met with the local inhabitants, generally explored and was able to collect her plants.

The onset of World War Two curtailed any plans for further journeys into the Arctic. After the war, she completed a number of long treks, including walking from her home in Scotland to London, from Innsbruck to Venice, and from Edinburgh to John O’Groats. Isobel Wylie Hutchison passed-away at her home in Carlowrie Castle in 1982, aged 92.

The Arctic journeys of Isobel Wylie Hutchison were extraordinarily daring during a time when such trips were unheard of for a single woman. She developed a real passion for the North as she explored various regions of the Arctic world. Isobel was a true adventure traveller, enjoying the uncertainty of her journey, taking calculated risks, but being utterly intrigued by all she saw in the Far North.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Friday 23rd June 2023

Breakfast this morning again in the hallowed surroundings of the main dining room where starched white linen table cloths abound and riff raff don't. Eggs Benedict tailored to one's needs with the requisite smoked salmon, all most civilised and above all, peaceful; no harsh and shrill American voice nor screeming children. Tranquility focused entirely on starting a new day with a meal to break the fast of the night now passed. Then the customary jaunt around the deck at speed, with a more chill but highly refreshing sea breeze direct from the arctic today. The sun not far away but not quite managing to clear a way through the clouds. Not many to share the experience with on deck apart from a few optimistic whale watchers excitedly exclaiming at a suspicious parting of the calm waters and a flourish of binoculars and telephoto lenses. Often to be disappointed and equipment stood down.

Today we docked (nautical term) at Ketchikan, Alaska. We were booked on the Rainforest Wildlife Sanctuary , Eagles and Totems tour.

Ketchikan we liked a lot. It was a frontier's town again set on yet another island. Together as an archipelago in SE Alaska it accounts for an area of rainforest the second largest in the world. The majority is not now commercially felled and is protected from logging. We were shown through a section of rainforest and native species of trees; Cedars, Red-Alders, Spruces and Hemlock most common. Interestingly felled trees on the forest floor provided sustenance for propagating seeds; a substitute for topsoil. With competition for light, the strongest will succeed. Our guide told us that bears inhabit these woods, and we suspect the code words 'ham sandwich' whispered into her radio related to a sighting of one close by which she wished the group to avoid. Certainly fresh bear poo in various sites might substantiate this. We saw spawned salmon in the river that when a certain size will make their way to the sea via Herring Cove; the route their parents will have taken a fews weeks previously and generations before them. More bald eagles, purple and blue swifts circling the river, a couple of owls in a sanctuary where they will stay for the rest of their lives because of injuries sustained in the wild rendering them unable to hunt for themselves. Oh, then there were totem poles. Bit of a mystery with this one. It would appear that the two main First Nation's tribes in this area have symbols of the Raven and the Eagle. A totem pole will have one or the other carved on it and it will be placed prominently in their village. A Raven wanting to marry must marry an Eagle and vise versa. We were introduced to an Indian chipping away at a new pole and we asked him if the pole told a story. Yes he said. What is it? We asked. Can't tell you, it would take too long. Give us the quick version then. That will take at least 10 minutes and I haven't got that amount of time. With that he resumed chipping.

The bus returned us to Ketchikan where we partook of an Alaskan beer or two in a seedy downtown bar called Asylum. The clientele on the rough and ready spectrum, part American, part Indian; the atmosphere heavy with the sweet aroma of cannabis. The thick set barmaid, possibly of Russian descent decidedly dismissive of our tourist credentials and indecisive approach to beer selection. We chose one described as Amber on the recommendation of the drunk on the barstool. With our integrity still intact we held our beers and heads aloft and found somewhere to sit in the courtyard. Unfortunately I had to return and grovel to Greta for the WiFi password. Replete and refreshed we strolled the high street to the old Red Light District, Creek Street. The sign said, 'If you can't find your husband, he's in here'. Well at least that clears that one up!

We very much enjoyed Ketchikan so much so I bought the tee shirt. It was agreeable, clean, well presented and perhaps with the exception of Greta, friendly considering 3 cruise ships dominated this small town of just 14,000 souls that day.

ps. The whole gang was here today, Brilliance of the Seas, Celebrity Eclipse, and Holland and Barrett (Holland America)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Understanding Current Real Estate Trends: Average Rent in Kodiak

Kodiak, the Jewel of the Alaskan Archipelago, is a unique city enthralled by mesmerizing scenes of nature and its rare blend of cultural diversity and community spirit. Factors including the city’s economic prosperity and demographics have buoyed its real estate sector, making it an attractive destination for real estate enthusiasts, families looking for a peaceful abode, and young professionals alike. One significant element of this real estate market is the average rent in Kodiak.

Simple economics dictates that the costs of living, along with rental prices, are generally higher in areas defined by a higher quality of life and economic opportunities. Kodiak, with a blend of both these offerings, sees an upward trend in real estate prices, especially rentals. Apartment rates in Kodiak echo this upward trend, shaped by a balance of demand and supply, coupled with the city's growth and development trajectory.

The Kodiak rental market features a variety of apartments ranging from basic studios to luxury accommodations, catering to different income groups and preferences. While costs can vary, the average monthly rent for a one-bedroom apartment in Kodiak is around $1,200, with slight fluctuations depending on the location and amenities. Prices for larger apartments or houses for rent can shift upwards, often breaching the $2,000 per month mark. The Kodiak real estate market demonstrates resilience and consistency, benefiting from the stability of the local economy and attractive lifestyle benefits. While rental rates might appear steep, they reflect Kodiak's unique qualities – its splendorous beauty, flourishing economy, low crime rate, and sense of community.

In conclusion, whether you're considering the prospect of moving in or investing in real estate, understanding the average rent in Kodiak and the factors that influence Apartment rates in Kodiak will equip you with valuable insights to make informed decisions. Kodiak's real estate mirrors the essence of this vibrant city, offering idyllic living conditions against a backdrop of stunning natural beauty.

0 notes

Text

Tuesday, July 18, 2023

Global hunger enters a grim ‘new normal’

(Washington Post) While the fact that there wasn’t a major increase in global hunger between 2021 and 2022 could be viewed as a positive sign, there are a lot more negative trends to be gleaned from the United Nations’ annual flagship report on global food security, which was released last week. The U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimated that between 691 million and 783 million people faced hunger last year. The midrange of that calculation, about 735 million, is 122 million more people going hungry than in 2019, before the coronavirus pandemic shook the world. This year’s report—“The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2023”—also found that nearly 30 percent of humanity, or roughly 2.4 billion people, lacked access to adequate food in 2022, while an even greater number—3.1 billion people—were unable to afford a healthy diet. It projected that by the end of the decade, despite significant poverty alleviation initiatives, some 600 million people will still be chronically undernourished, a blow to U.N.-outlined goals of eliminating hunger by 2030. Qu Dongyu, director general of the FAO, said in a statement. “This is the ‘new normal’ where climate change, conflict, and economic instability are pushing those on the margins even further from safety.”

Air quality warnings return in U.S. as Canada deploys troops for wildfires

(Washington Post) Canada deployed its military to help overwhelmed local authorities and emergency workers fight intensifying wildfires, which have burned nearly 25 million acres of the country’s land so far this year and prompted authorities in parts of the United States to issue air quality warnings. The Canadian Armed Forces and Canadian Coast Guard will deploy to British Columbia, in the west of the country, after the province submitted a request for federal assistance that the Canadian government approved, it said Sunday. Smoke from the fires turned the sky orange in parts of the U.S. East Coast last month, prompting local health authorities to issue air quality warnings and ask people, especially the most vulnerable, to stay indoors. Parts of the U.S. Northeast, Midwest and South, as well as the Great Plains, were forecast to reach air quality levels Monday that are unhealthy for vulnerable people, including Pittsburgh, Chicago and Nashville, according to AirNow, a tracker maintained by a group of U.S. government agencies. Parts of Iowa and cities on the northeast border with Canada—including Cleveland and Buffalo—were expected to experience “unhealthy” air quality levels, according to AirNow. Louisville, the most populous city in Kentucky, was under an Air Quality Alert on Monday.

Rumbles in Alaska

(1440) Alaskans spent the weekend experiencing an uptick in seismic activity, with a series of volcanic eruptions from the remote Shishaldin Volcano Friday followed by a 7.2 magnitude earthquake late Saturday morning off the southwestern coast. The volcano is nestled in the middle of the sparsely populated Aleutian Islands, part of the archipelago making up the Alaskan peninsula. Shishaldin started exhibiting low-intensity eruptions Tuesday but began Friday with a burst that sent an ash cloud nearly 40,000 feet in the air. Meanwhile, the Saturday earthquake was the strongest to hit the area since an 8.2 magnitude quake in 2021. The region sits along the northeastern ridge of the “Ring of Fire”—a set of tectonic boundaries that encircle the Pacific basin, giving rise to numerous volcanoes and frequent earthquakes along its perimeter.

Weeks of extreme heat are straining aging infrastructure.

(WSJ) A streak of 110-degree days is frying Phoenix, and an unrelenting heat wave is punishing Texas and other parts of the South. Some of the hardest-hit areas will face hotter temperatures in the coming days, forecasters say. The heat wave is testing the U.S. electric grid, which is being asked to deliver more power for running air conditioners without much of a break for routine maintenance. The North American Electric Reliability Corporation, a nonprofit that monitors the health of the bulk power system, says large portions of the U.S. could face blackouts this summer.

American Paychecks Grow, Europeans Become Poorer

(WSJ) Americans’ growing paychecks surpassed inflation for the first time in two years, providing some financial relief to workers, while complicating the Federal Reserve’s efforts to tame price increases. Inflation-adjusted average hourly wages rose 1.2% in June from a year earlier, according to the Labor Department. That marked the second straight month of seasonally adjusted gains after two years when workers’ historically elevated raises were erased by price increases. Europeans, meanwhile, are facing a new economic reality: They are becoming poorer. The French are eating less foie gras and drinking less red wine. Spaniards are stinting on olive oil. Finns are being urged to use saunas on windy days when energy is less expensive. German meat and milk consumption has fallen to the lowest level in three decades. With consumption spending in free fall, Europe tipped into recession at the start of the year, reinforcing a sense of relative economic, political and military decline.

A National Treasure, Tarnished: Can Britain Fix Its Health Service?

(NYT) Fifteen hours after she was taken out of an ambulance at Queen’s Hospital with chest pains and pneumonia, Marian Patten was still in the emergency room, waiting for a bed in a ward. Mrs. Patten, 78, was luckier than others who arrived at this teeming hospital, east of London: She had not yet been wheeled into a hallway. For months, doctors at Queen’s have been forced to treat people in a corridor because of a lack of space. As the ambulances kept pulling up outside, the doctor supervising the E.R., Darryl Wood, said it was only a matter of time before nurses would begin diverting patients into the overflow space again. “We’re in that mode every day now because the N.H.S. doesn’t have the capacity to deal with all the patients,” Dr. Wood said. As it turns 75 this month, the N.H.S., a proud symbol of Britain’s welfare state, is in the deepest crisis of its history: flooded by aging, enfeebled patients; starved of investment in equipment and facilities; and understaffed by doctors and nurses, many of whom are so burned out that they are either joining strikes or leaving for jobs abroad. Interviews over three months with doctors, nurses, patients, hospital administrators and medical analysts depict a system so profoundly troubled that some experts warn that the health service is at risk of collapse.

Riots in France Highlight a Vicious Cycle Between Police and Minorities

(NY) Years before France was inflamed with anger at the police killing of a teenager during a traffic stop, there was the notorious Théo Luhaka case. Mr. Luhaka, 22, a Black soccer player, was cutting through a known drug-dealing zone in his housing project in a Paris suburb in 2017 when the police swept in to conduct identity checks. Mr. Luhaka was wrestled to the ground by three police officers, who hit him repeatedly and sprayed tear gas in his face. When it was over, he was bleeding from a four inch tear in his rectum, caused by one of the officers’ expandable batons. Mr. Luhaka’s housing project, and others around Paris, erupted in fury. He was held up as a symbol of what activists had been denouncing for years: discriminatory policing that violently targets minority youth, particularly in France’s poor areas. And there was a sense that, this time, something would change. Instead, the relationship between the country’s minority populations and its heavy-handed police force worsened, many experts say, as evident in the tumultuous aftermath of the killing in late June of Nahel Merzouk, 17, a French citizen of Algerian and Moroccan descent. After multiple violent, publicized encounters involving the police, a pattern emerged: Each episode led to an outburst of rage and demands for change, followed by a pushback from increasingly powerful police unions and dismissals from the government. “It’s a repeating cycle, unfortunately,” said Lanna Hollo, a human rights lawyer in Paris who has worked on policing issues for 15 years. “What characterizes France is denial. There is a total denial that there is a structural, systemic problem in the police.”

Wind-fanned wildfires force thousands to flee seaside resorts outside Greek capital

(AP) Wildfires outside Athens forced thousands to flee seaside resorts, closed highways and gutted vacation homes Monday, as high winds pushed flames through hillside scrub and pine forests parched by days of extreme heat. Authorities issued evacuation orders for at least six seaside communities as two major wildfires edged closer to summer resort towns and gusts of wind hit 70 kph (45 mph). The army, police special forces and volunteer rescuers freed retirees from their homes, rescued horses from a stable, and helped monks flee a monastery threatened by the flames.

Russia blames Ukraine for attack on key Crimea military supply bridge that kills 2

(AP) Traffic on a key military supply bridge connecting Crimea to Russia’s mainland came to a standstill Monday after one of its sections was blown up, killing two people and wounding their daughter. Russian officials blamed the attack on Ukraine, but Kyiv officials didn’t openly admit it. The strike on the 19-kilometer (12-mile) Kerch Bridge was carried out by two Ukrainian sea drones, Russia’s National Anti-Terrorist Committee said. Ukrainian officials didn’t claim responsibility for the attack, which is the second major strike on the bridge since October, when a truck bomb blew up two of its sections. The $3.6 billion bridge is the longest in Europe and is crucial for enabling Russia’s military operations in southern Ukraine during the almost 17-month-long war.

Russia halts wartime deal that allows Ukraine to ship grain

(AP) Russia said Monday it has halted an unprecedented wartime deal that allows grain to flow from Ukraine to countries in Africa, the Middle East and Asia where hunger is a growing threat and high food prices have pushed more people into poverty. Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov announced halting the deal in a conference call with reporters, adding that Russia will return to the deal after its demands are met. “When the part of the Black Sea deal related to Russia is implemented, Russia will immediately return to the implementation of the deal,” Peskov said. Russia has complained that restrictions on shipping and insurance have hampered its exports of food and fertilizer—also critical to the global food chain.

China’s youth unemployment hits record high

(BBC) As China’s post-pandemic recovery falters, last month 21.3% of 16 to 24 year olds in the nation’s urban areas were unemployed. The second largest economy only grew 0.8% in the three months, with demand for Chinese goods falling while local government debt and the housing market skyrocketed.

13 found dead in flooded tunnel as South Korean storm toll rises to 40

(Washington Post) Thirteen bodies were recovered from a tunnel in South Korea as the flooding death toll across the country rose to at least 40. Cars were trapped in a tunnel underpass in Osong near the city of Cheongju, about 70 miles south of Seoul, when the Miho River burst its banks on Saturday. More than 10 vehicles including a bus were flooded and 13 people were killed, with nine rescued at the scene, the Ministry of Public Administration and Safety said in a statement on Monday. Up to 23 inches of rain has fallen on South Korea since Thursday, triggering landslides and road collapses, wiping out crops, and damaging homes and other buildings.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Mockingbirds song |Masterlist|

Pairing: hybrid!Taehyung x hybrid!f!reader

Summary: You had fled from your old home, your old owner, your old life in hopes you’ll find a better one. You ran as far as you could, as much as you could, until you couldn’t. Left for dead, you have no hopes you’ll make it to see the light of the morning.

Total wc: 1.4k (with teaser 2.7k)

Genre: angst, fluff…

Hybrid types: Reader: Omega!Red wolf, Namjoon: Alpha!Eurasian wolf, Yoongi: Omega!Alaskan Tundra wolf,Hoseok: Alpha!Steppe wolf Jin: Beta!Great Plains wolf, Jimin: Omega!Northwestern wolf Jungkook: Beta!Arctic wolf, Taehyung: Alpha!Alexander archipelago wolf

| Teaser/intro |₊˚ପ⊹ | Chapter//1 |₊˚ପ⊹ | Chapter//1.5 |₊˚ପ⊹ | Chapter//2 |₊˚ପ⊹ | Chapter//3 |₊˚ପ⊹ | Chapter//4..

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Is Alaska Seafood Company?

Alaska Seafood Company is a seafood company that specializes in salmon fishing. They have a fleet of vessels that they use to fish for salmon, halibut, and tuna. They sell their seafood either fresh or frozen.

Alaska Seafood Company is the only seafood company in Alaska that specializes in fresh, sustainable Alaska seafood. To find more about the Alaska seafood company then visit https://www.sugpiaqseafood.com/.

Image Source: Google

The company was founded by Rick and Julie Roush in 2006, and began operations out of their home on the Kenai Peninsula. Today, Alaska Seafood Company operates a fleet of fishing boats and processing facilities on the Kenai Peninsula, Gulf of Alaska, Kodiak Archipelago, and Prince William Sound.

The Roush's focus on sustainable practices when harvesting their seafood. They use longline gear to catch halibut and salmon using baited hooks that allow them to keep fish alive until they are ready to be processed. This method results in less waste and helps maintain populations of Alaskan fish species.

The company also uses cold storage techniques to preserve seafood before it is sold. This allows them to sell fresh fish year-round without having to ship it overseas or subject it to temperature fluctuations during transport.

In addition to selling seafood directly to consumers, Alaska Seafood Company provides catering services for events like weddings and corporate functions. Alaska Seafood Company is a fishing company that specializes in fishing for salmon and halibut.

They offer fresh, frozen, and prepared seafood products. They also have a retail store that sells Alaska-themed items. At Alaska Seafood Company, we believe that the best seafood is fresh and sustainable.

That's why we only use the finest Alaskan seafood, sourced from local fishermen who abide by strict catch limits and catch periods to ensure a sustainable fishery. You can also click here for more info about the Alaska seafood company.

Image Source: Google

Our salmon is hand-picked and flash frozen right after being caught to lock in the flavor and nutrients. Our crab is also fresh, caught the day before it's served. We don't use any processed or preservative laden seafood, so you can be sure you're getting the most delicious meal possible.

We also offer a variety of lobster items, like our lobster bisque soup and lobster roll. Our bisque is made with chunks of lobster meat, while our lobster roll features two soft boiled lobsters with a crispy exterior.

1 note

·

View note

Text

What An Ancient Jawbone Reveals About Polar Bear Evolution

Grizzly bears and polar bears aren't one species—but they share a close ancient history.

— By Philip Kiefer | June 7, 2022 | Popular Science

The jawbone of a polar bear that lived on the archipelago of Svalbard 115,000 to 130,000 years ago. Karsten Sund, Natural History Museum (NHM), University of Oslo

The longer you think about polar bears, the stranger they seem. They’re the largest bears and the largest land predator. They’re adapted to a life spent crossing open ice floes, or waiting out hungry summer months. Despite those superlatives, it’s hard to figure out how exactly these bears came to be, because they rarely leave bones behind to be studied. “When they die, their remains end up on the seafloor,” says Charlotte Lindqvist, an evolutionary biologist at State University of New York at Buffalo.

So in 2004, when a geologist working in the cliffs of the archipelago of Svalbard, Norway, found a 115,000-year-old jawbone sticking out of the sediment, the find spurred decades of insight into the evolution of the polar bear. A new, high-resolution analysis of the DNA contained in that jawbone, published this week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, opens a window into the evolution of both brown bears and polar bears through a warming and cooling world.

The study also clarifies a yearslong debate among evolutionary biologists: Polar bears and brown bears are so closely related that it’s been proposed the animals should be lumped together as one species. According to the new analysis, which compared the DNA of the ancient jawbone to that of 65 modern bears, the species are clearly genetically distinct.

The population history of polar bears and brown bears is “so different,” says Lindqvist, who has led much of that research on the genes of ancient polar bears. “One is this Arctic specialist, and one is a boreal generalist, found across the Northern Hemisphere.”

But the two have evolved in tandem for roughly the past million years, and polar bears carry genes from repeated interbreeding with brown bears. That’s a new discovery—prior studies, which hadn’t had access to the ancient jawbone, had suspected that polar bears had contributed genes to brown bears. In fact, it’s the other way around.

Since the early 2000s, biologists have watched ‘pizzly bears’ expand across the high Arctic as brown bears move north into polar bear habitat. But the pizzlies, the offspring of a polar bear and a grizzly, aren’t as common as news coverage makes it seem. As far as genomicists can tell, the hybrids are all descended from a single female polar bear, who mated with two different brown bears.

That pattern seems to have been true for ancient bears, too. Hybridization might have been consistent, but it wasn’t common—a chance encounter between a few individuals, rather than an interspecies love fest. Brown and polar bears live radically different lives, even when they cohabit the same latitudes. Polar bears are primarily an ocean animal—hence their scientific name, Ursus maritimus—and breed mostly in March and April. Brown bears hunt in forests and plains, and breed during the summer.

Studying polar bears in zoos could help their wild counterparts. Deposit Photos

Brown bears are wildly genetically diverse compared to their maritime cousins. There are the populations Americans know as grizzly bears, which inhabit the Rocky Mountains and once lived as far south as Mexico. There are European brown bears in Scandinavia and Russia. There are Kodiak bears, which live on the Alaskan Kodiak Archipelago, and grow nearly twice the size of typical brown bears, rivaling the size of a bison.

Once, polar bears were genetically diverse, too. The ancient polar bear whose jawbone was retrieved in Norway carries enough unique genes to be a “sister group” to its modern counterparts. Still, says Lindqvist, it lived in the same place as today’s polar bears. It grew to about the same size. “At least from that limited evidence, it was just a regular polar bear as we know it today,” she says.