#abolish the family

Text

What is the family? So deep runs the idea that the family is the exclusive place where people are safe, where people come from, where people are made, and where people belong, it doesn’t even feel like an idea anymore. Let us unpick it, then.

The family is the reason we are supposed to want to go to work, the reason we have to go to work, and the reason we can go to work. It is, at root, the name we use for the fact that care is privatized in our society. And because it feels synonymous with care, “family” is every civic-minded individual’s raison d’être par excellence: an ostensibly non-individualist creed and unselfish principle to which one voluntarily signs up without thinking about it. What alternative could there be? The economic assumption that behind every “breadwinner” there is a private someone (or someones) worth being exploited for, notably some kind of wife—that is, a person who is likely a breadwinner too—“freely” making sandwiches with the hard-won bread, or hiring someone else to do so, vacuuming up the crumbs, and refrigerating leftovers, such that more bread can be won tomorrow: this feels to many of us like a description of “human nature.”

Without the family, who or what would take responsibility for the lives of non-workers, including the ill, the young, and the elderly? This question is a bad one. We don’t hesitate to say that nonhuman animals are better off outside of zoos, even if alternative habitats for them are growing scarcer and scarcer and, moreover, they have become used to the abusive care of zoos. Similarly: transition out of the family will be tricky, yes, but the family is doing a bad job at care, and we all deserve better. The family is getting in the way of alternatives.

In part, the vertiginous question “what’s the alternative?” arises because it is not just the worker (and her work) that the family gives birth to every day, in theory. The family is also the legal assertion that a baby, a neonatal human, is the creation of the familial romantic dyad; and that this act of authorship in turn generates, for the authors, property rights in “their” progeny—parenthood—but also quasi-exclusive accountability for the child’s life. The near-total dependence of the young person on these guardians is portrayed not as the harsh lottery that it patently is, but rather as “natural,” not in need of social mitigation, and, furthermore, beautiful for all concerned. Children, it is proposed, benefit from having only one or two parents and, at best, a few other “secondary” caregivers. Parents, it is supposed, derive nothing so much as joy from the romance of this isolated intensity. Constant allusions to the hellworld of sheer exhaustion parents inhabit notwithstanding, their condition is sentimentalized to the nth degree: it is downright taboo to regret parenthood. All too seldom is parenthood identified as an absurdly unfair distribution of labor, and a despotic distribution of responsibility for and power over younger people. A distribution that could be changed.

Like a microcosm of the nation-state, the family incubates chauvinism and competition. Like a factory with a billion branches, it manufactures “individuals” with a cultural, ethnic, and binary gender identity; a class; and a racial consciousness. Like an infinitely renewable energy source, it performs free labor for the market. Like an “organic element of historical progress,” writes Anne McClintock in Imperial Leather, it worked for imperialism as an image of hierarchy-within-unity that grew “indispensable for legitimating exclusion and hierarchy” in general. For all these reasons, the family functions as capitalism’s base unit—in Mario Mieli’s phrase, “the cell of the social tissue.” It may be easier to imagine the end of capitalism, as I’ve riffed elsewhere, than the end of the family. But everyday utopian experiments do generate strands of an altogether different social tissue: micro-cultures which could be scaled up if the movement for a classless society took seriously the premise that households can be formed freely and run democratically; the principle that no one shall be deprived of food, shelter, or care because they don’t work.

Sophie Lewis, Abolish the Family

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

At present, it is standard among practically all communities to fête the family as a bastion of relative safety from state persecution and market coercion, and as a space for nurturing subordinated cultural practices, languages, and traditions. But this is not enough of a reason to spare the family. Frustratedly, Hazel Carby stressed the fact (for the benefit of her white sisters) that many racially, economically, and patriarchally oppressed people cleave proudly and fervently to the family. She was right; nevertheless, as Kathi Weeks puts it: “the model of the nuclear family that has served subordinated groups as a fence against the state, society and capital is the very same white, settler, bourgeois, heterosexual, and patriarchal institution that was imposed by the state, society, and capital on the formerly enslaved, indigenous peoples, and waves of immigrants, all of whom continue to be at once in need of its meagre protections and marginalized by its legacies and prescriptions” (emphasis mine). The family is a shield that human beings have taken up, quite rightly, to survive a war. If we cannot countenance ever putting down that shield, perhaps we have forgotten that the war does not have to go on forever.

This is why Paul Gilroy remarked in his 1993 essay “It’s A Family Affair,” “even the best of this discourse of the familialization of politics is still a problem.” Gilroy is grappling with the reality that, in the United Kingdom as in the United States, the state’s constant disrespect of the Black home and transgression of Black households’ boundaries, as well as its disproportionate removal of Black children into the foster-care industry, understandably inspires an urgent anti-racist politics of “familialization” in defense of Black families. Both the British and American netherworlds of supposedly “broken” homes (milieus that are then exoticized, and seen as efflorescing creatively against all odds), have posed an obstinate threat to the legitimacy of the family regime simply by existing, Gilroy suggests. The paradox is that the “broken” remnant sustains the bourgeois regime insofar as it supplies the culture, inspiration, and oftentimes the surrogate care labor that allows the white household to imagine itself as whole. As a dialectician, “I want to have it both ways,” writes Gilroy, closing out his essay. “I want to be able to valorize what we can recover, but also to cite the disastrous consequences that follow when the family supplies the only symbols of political agency we can find in the culture and the only object upon which that agency can be seen to operate. Let us remind ourselves that there are other possibilities.

There are other possibilities! Traces of the desire for them can be found in Toni Cade (later Toni Cade Bambara)’s anthology The Black Woman, published in America in 1970, not long after the publication of the US labor secretariat’s “Moynihan report,” The Negro Family: The Case for National Action. The open season on the Black Matriarch was in full swing. And certainly not all of the anthology’s feminists, in their valiant effort to beat back societal anti-maternal sentiment (matrophobia) and the hatred of Black women specifically (more recently known as “misogynoir”), make the additional step of criticizing familism within their Black communities. But one or two contributors do flatly reject the notion that the family could ever be a part of Black (collective human) liberation. Kay Lindsey, in her piece “The Black Woman as a Woman,” lays out her analysis that: “If all white institutions with the exception of the family were destroyed, the state could also rise again, but Black rather than white.” In other words: the only way to ensure the destruction of the patriarchal state is for the institution of the family to be destroyed. “And I mean destroyed,” echoes the feminist women’s health center representative Pat Parker in 1980, in a speech she delivered at ¡Basta! Women’s Conference on Imperialism and Third World War in Oakland, California. Parker speaks in the name of The Black Women’s Revolutionary Council, among other organizations, and her wide- ranging statement (which addresses imperialism, the Klan, and movement- building) purposively ends with the family: “As long as women are bound by the nuclear family structure we cannot effectively move toward revolution. And if women don’t move, it will not happen.” The left, along with women especially of the upper and middle classes, “must give up ... undying loyalty to the nuclear family,” Parker charges. It is “the basic unit of capitalism and in order for us to move to revolution it has to be destroyed.”

Forty years later, the British writer Lola Olufemi is among those reminding us that there are other possibilities: “abolishing the family...” she tweets, “that’s light work. You’re crying over whether or not Engels said it when it’s been focal to black studies/black feminism for decades.” For Olufemi as for Parker and Lindsey, abolishing marriage, private property, white supremacy, and capitalism are projects that cannot be disentangled from one another. She is no lone voice, either. Annie Olaloku-Teriba, a British scholar of “Blackness” in theory and history, is another contemporary exponent of the rich Black family-abolitionist tradition Olufemi names. In 2021, Olaloku-Teriba surprised and unsettled some of her followers by publishing a thread animated by a commitment to the overthrow of “familial relations” as a key goal of her antipatriarchal socialism. These posts point to the striking absence of the child from contemporary theorizations of patriarchal domesticity, and criticize radicals’ reluctance to call mothers who “violently discipline [Black] boys into masculinity” patriarchal. “The adult/child relation is as central to patriarchy as ‘man’/‘woman,’” Olaloku-Teriba affirms: “The domination of the boy by the woman is a very routine and potent expression of patriarchal power.” These observations reopen horizons. What would it mean for Black caregivers (of all genders) not to fear the absence of family in the lives of Black children? What would it mean not to need the Black family?

Sophie Lewis in “Abolish Which Family?” from Abolish the Family: A Manifesto for Care and Liberation, 2022.

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

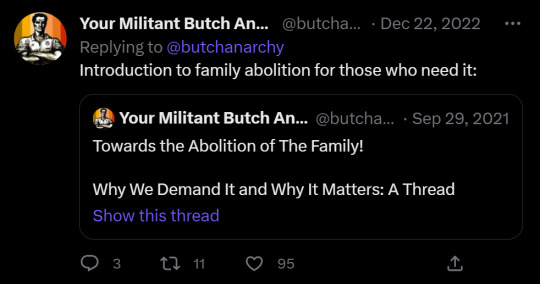

https://twitter.com/butchanarchy/status/1605984420778778625

[transcription:

butchanarchy:

If you have the great (and rare) fortune to have a loving and supportive kinship network the abolition of the institution of the family is something you should support, because its ultimate goal is for everyone to have that love and support regardless of their luck in blood relations.

If you think of times that you wouldn’t have gotten through something if not for the support of your family, you should also be able to see how difficult it is for people who have abusive/neglectful family that they are forced to be reliant on in the absence of other support.

Introduction to family abolition for those who need it:

Towards the Abolition of The Family!

Why We Demand It and Why It Matters: A Thread

AlmiraAlba5 (reply):

Excellent thread, thank you. The institution of family perpetuates cycles of abuse and dysfunction. Abused members may be held hostage by both their abusers and their own feelings of familial duty, which, for any multitude of reasons, they are unable to abandon.

texantifascist (quote tweet):

THIS. It should be a connection of people who are voluntarily joined through love and support.

thirdworldmiss1 (quote tweet):

Yes. Telling me “sorry you have a crap family” makes me want to abolish yours, okay? /s

turnedtofire (quote tweet):

I learned an enormous amount from this thread and the nested thread. It’s about how institutional power isn’t just concentrated in “the church” and “the government,” but also in “the family”—a relationship that gets clearer when you think about how cisheteropatriarchy works.

I’m particularly struck by what OP says about how abuse victims are often isolated within families—particularly if they are children, older or disabled—because (as I’ve recently experienced) outsiders are hugely reluctant to interfere between partners, or parents and children

Also now I think about it, even the fact I thoughtlessly said “interfere” says a lot—what if we reframed it as “intervening”?

The content in the nested thread has also been reposted here:

/end transcription]

#repost of someone else’s content#twitter repost#butchanarchy#FAQ#101#nuclear family abolition#ageism#adultism#domestic abuse#child abuse#parental abuse#abolish the family#youthlib#youth liberation#the anarchist library

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

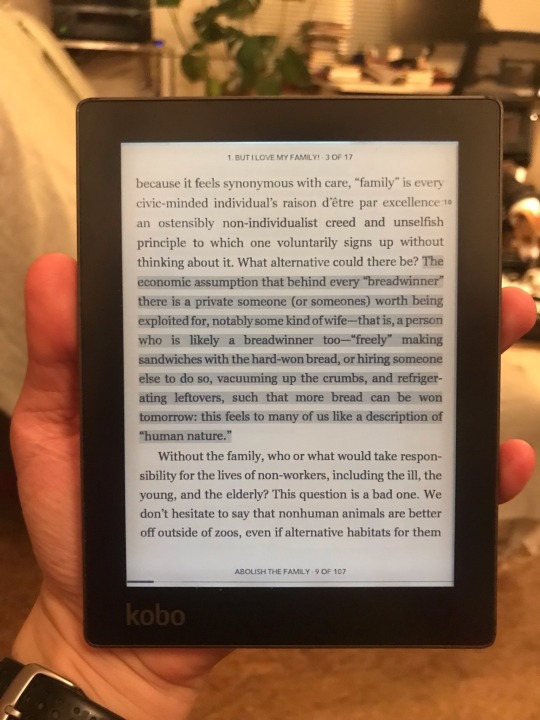

Absolutely in love with Sophie Lewis and her book "Abolish the family"

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

does anyone have a pdf or link to abolish the family by sophie lewis to share with me privately 👉👈

1 note

·

View note

Text

who needs a functional economy when you could pay for a billionaire pensioner's hat party instead

#uk politics#uk#coronation#charles 3#charles iii#abolish the monarchy#british royals#british royal family#royal family#imperialism#hat party

12K notes

·

View notes

Text

A little something made by me in honor of this momentous occasion

#queen Elizabeth#crab rave#the queen#sans undertale#current events#Queen Elizabeth ii#rip bozo#british#britain#uk politics#abolish the monarchy#royal family#england#queen of england#the british monarchy#destiel#great british bake off#fresh memes#memes#paul hollywood#prince philip#prince harry#princess diana#prince charles

39K notes

·

View notes

Text

it’s existentially petrifying to imagine relinquishing the organized poverty we have in favor of an abundance we have never known and have yet to organize

Sophie Lewis, Abolish the Family

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

For well over a century, as we will see in the next chapter, socialists, feminists, and revolutionaries in the United States have argued over the best orientation to take toward forms of family that aren’t (or at least don’t seem to be) bourgeois or white. The fight hit the mainstream when, in 1965, the US secretary of labor officially diagnosed the (female-led) “Negro family” as “a tangle of pathology,” galvanizing an entire critical tradition back into action. In the thirties, Black socialist sociologists like E. Franklin Frazier had set out to discover—and appropriate for the purposes of a politics of Black respectability—a true pastoral Black family within the archive of slavery. Naturally, the violently anti-Black Moynihan report revived this tradition. This time around, though, a skeptical left-feminist counter- tradition emerged, too, which peaked with philosopher Hortense Spillers’s epochal account of the production of Black un-motherhood in ante-bellum America, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe.” Unimpressed with the reconciliatory misogyny embedded in pro-Black protestations (like Frazier’s) that enslaved people had always aspired to the patriarchal family as best they could—with the implication that, hence, their descendants can and will uphold it—Spillers wanted to take the violently produced “kinlessness” of Black people seriously enough to necessitate the crafting of a whole new kin-equivalent way of relating.

She writes: “Whether or not we decide that the support systems that African-Americans derived under conditions of captivity should be called ‘family,’ or something else, strikes me as supremely impertinent.” The point, for Spillers, is that “African peoples in the historic Diaspora had nothing to prove,” given that it is “stunningly evident” that they were capable of modes of care “at least as complex as those of the ‘nuclear family’ in the West.” Rather than orienting toward the “family” as a measuring-stick (or aspiration), Spillers focuses on the fact that Black women in the wake of slavery stand “out of the traditional symbolics of female gender,” and what this means for political struggle—namely: “it is our task to make a place for this different social subject.” A place, in other words, that one might call a family, or not. So, whereas Frazier’s “good revisionist history” (as Spillers acidly calls it) of “The Negro Family” is ironically quite close to Moynihan’s—both agree that a “matriarchate” is something obscene—Spillers discards both options, proposing that the existing “grammar” of American life is unfit for purpose, especially for Black women: “We are less interested in joining the ranks of gendered femaleness than gaining the insurgent ground as female social subject.”

Spillers’s text can be read as family-abolitionist, and Tiffany Lethabo King does read it that way in a 2018 essay, to great effect. But apart from “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe,” King notes, Black scholarly and feminist/ womanist responses to the Moynihan report rarely go this far; “rarely [do they] interrogate the viability of the notion of the family itself.” Rather, arguments are typically made for “expanded,” “extended,” “non-sanguinal,” “queer,” and “intergenerational” alternatives. The problem, for King, with these “modifications and revisions to the family” is that they “still retain attachments to the liberal humanistic concept of the filial,” meaning that they refer back to the human “subject” of liberalism who has not been ungendered via slavery, and so don’t quite break free of the definition of kinship (kinship-as-property-relation) that Spillers, in the eighties, exposed as elemental to white American culture (its racial/gender grammar).

Sophie Lewis in “Abolish Which Family?” from Abolish the Family: A Manifesto for Care and Liberation, 2022.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

#sophie anne lewis#abolish the family#quote of the day#reading quotes#social issues#social inequality

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anyway regardless of how you feel about the Royals, even if you’re like me and think they’re all parasites, here are some things to remember:

The UK taxpayer is funding Kate’s high-end treatments whilst millions of citizens are on years-long NHS waiting lists for their own treatments and waiting hours upon hours to be seen in A&E when they’ve had a severe incident; so much money that could be going towards funding the NHS properly is instead going to the Royals. Kate is very likely going to be perfectly fine. Millions of regular tax-paying UK citizens will not.

HOWEVER. Kate isn’t going to see your memes making fun of her on tumblr dot com — but other people whom have suffered because of cancer will. If common decency won’t stop you from posting crab rave GIFs celebrating the illness of a mother to three young children, hopefully the chance of someone else with cancer or with a friend or relative with cancer seeing it will.

Seriously does no one else think Kensington’s PR nightmare is kind of fucked up like the fact they were so Weird about all this and let a sick woman in their “family” take all the blame for their shitty Photoshop skills. Royalist stan blogs I’ve seen you on here and I ask you: is THAT not some kind of indication as to how fucking evil they are if absolutely nothing else is. Please tell me you’ve seen the light by now I can’t cope anymore

#Breaking news we all already knew: The Royals are misogynistic af#kate middleton#royal family#british royal family#nhs#british politics#uk politics#tw cancer#terminal illness#abolish the monarchy#down with the crown#fuck the royals#anti royal family

491 notes

·

View notes

Text

imagine if diana just fucking showed up

#coronation#abolish the monarchy#fuck the monarchy#fuck the royal family#british royal family#uk politics#king charles iii

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

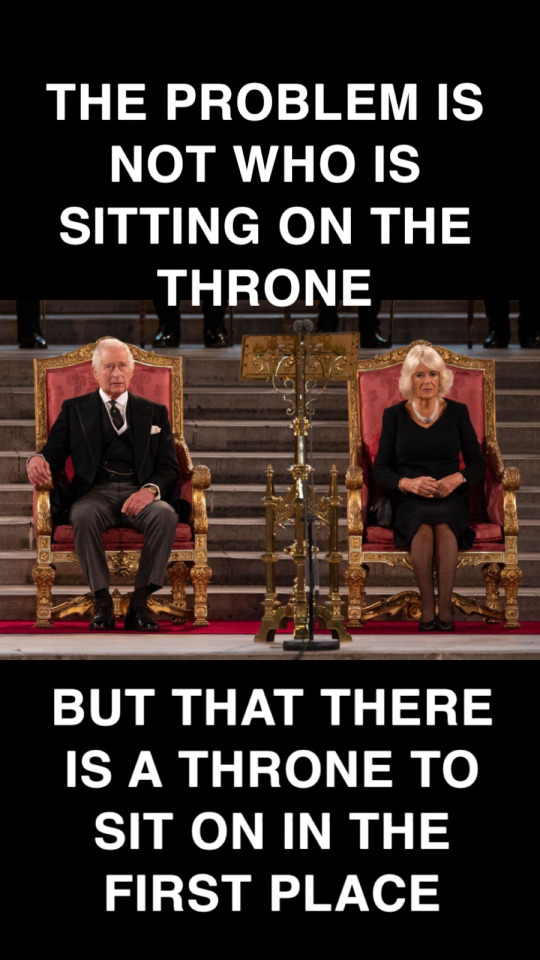

#anti monarchy#abolish the monarchy#fuck the monarchy#they’re cocks#pieces of SHIT#stealing from people#murdering#slave owning#rich#shit stains#not a countdown#id in alt text#tampon charlie#c*milla#bitch asses#hate them#the coronation#just shitposting#image#alt text#british royalty#british royal family#king charles iii#queen camilla#queen of england#king of england#uk politics#british politics#punk

1K notes

·

View notes