#aarne thompson uther

Text

(I was going to make a post about "Why Tale Type 425 is my favorite", and then realized I should find a good explanation of what that means, first)

I've known about this index for decades, and it's one of my favorite things. It helps me think about my own "in the folk tradition" creations -- like stitching old pieces of fabric into a new quilt.

I didn't realize until I read this article, though, that it was updated and rearranged in 2008, to try and correct for the sexism and Eurocentrism (work's not done, but it's begun).

BTW, Melvil Dewey was pressured to resign from the American Library Association in 1905, for racism, antisemitism, and sexual harassment of women. So not only does the ATU motif index have more ogres, it also has less bigotry.

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think it would be fun to challenge people to write stories promoted only by categories in the aarne-thompson-uther index. With the optional additional challenge that the genre/style is NOT folk tale or fable.

Categories such as “war between birds (insects) and quadrupeds” and “which bird is father?” and “innocent slandered maiden” and “suitors at the spinning wheel” and “seemingly dead relatives” and, possibly my favorite, “cases solved in a manner worthy of Solomon”

I’m finding a lot from this table of tale types: https://libraryguides.missouri.edu/c.php?g=1083510

#my post#fairy tales#folk tales#fables#atu index#aarne-thompson-uther index#classifications#writing#prompt

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Curious: what are your favorite type of fairy stories listed in the Aarne-Thompson enciclopedia classification?

First off, it's nice to meet you and thank you for asking! Secondly, I want to preface this: I'm not a student or a scholar of folklore as a genre, and my knowledge of ATU is limited to what I've managed to find online over the years. More often than not, it's either something I've found on JStor in college, something in a Maria Tatar book, or this website.

Still, I love seeing these stories and all their variations across times and places. Without further ado:

306: The Worn-Out Dancing Shoes: I love the mystery element of this story, and I'm forever intrigued by all the variations of the other world the women travel to, whether it's the palace of Indra, the court of Satan, or something else entirely. Many versions attribute their actions to some curse that must be broken to achieve a heterosexual happy ending, but it's in the in-between that this story really sings to me. And a not-quite-variant of it, "Kate Crackernuts", may just be my favorite fairy tale of all time; how often is the ugly (or at least, "less bonny") stepsister the hero of her own story?

310: The Maiden in the Tower: I'm a sucker for a magical chase, and Rapunzel's relatives absolutely provide. My favorites include "Snow-White-Fire-Red", "The Canary Prince", and "Louliyya, Daughter of Morgan".

311: Magic Flight: Stories of magical escapes from dire situations, like "Sweetheart Roland", "The White Dove", "The Fox Sister", and "The Tail of the Princess Elephant".

407: The Flower Girl: Plants who become women or vice versa, often coupled with an escape from an abusive romance. I love these stories purely for the folkloric weirdness factor: "A Riddling Tale" (shout-out to Erstwhile for introducing me to this one), "The Gold-Spinners", "The Girl in the Bay Tree", and "Pretty Maid Ibronka".

451: Brothers as Birds: This one's purely on my love for the Grimms' "Six Swans" and "Seven Ravens". I love a resilient heroine who draws her strength from her family. I admittedly haven't read many others, but these two mean so much to me they get a place here entirely on the strength of these two.

510B: All-Kinds-Of-Fur: The story of a woman's escape from her incestuous father who then gets a Cinderella ending. I admire the heroine's courage in face of an all too real type of monster. Grimms' is a favorite, as is "Florinda" (which could also qualify as 514), "Princess in a Leather Burqa", "The She-Bear", and "Nya-Nya Bulembu".

514: The Shift of Sex: I first came across this story when I stumbled on Psyche Z. Ready's terrific thesis some years ago and I haven't been able to get it out of my mind since. All of these variations from all over the world -- I find it cathartic to know that we've been asking these questions about gender and sexuality forever, and a happy ending is an imaginative possibility.

709: Fairest of Them All: This I owe squarely to Maria Tatar's anthology from a few years ago. Unfortunately, this also means that there are several I can't find online, including "Kohava the Wonder Child" (a rare Jewish heroine in a genre infamous for how it absorbs anti-Semitism) and "King Peacock" (one of the few African American fairy tales I know, also included in Tatar's collaboration with Henry Louis Gates). I love "Princess Aubergine", "Little Toute-Belle", and especially "Gold-Tree and Silver-Tree" - my little bi self was elated to stumble across a princess who lives happily ever after with her kind and gentle limbo husband and her cunning and resourceful wife.

Even as a hobbyist, I love folklore and fairy tales. I love these little glimpses into other cultures, and I love the way these story structures act as magnets for so many nuances of people's lives across history. Still, I hope this answers your question, gives a glimpse into my experience with fairy tales as a genre, or (at the very least) gives you some new and interesting stories to read!

#ariel seagull wings#ask response#fairy tales#the six swans#12 dancing princesses#Kate crackernuts#snow white#rapunzel#the canary prince#the fox sister#sweetheart roland#wild swans#all kinds of fur#donkeyskin#fet fruners#gold tree and silver tree#Aarne Thompson Uther index#the classification system isn't perfect#because nothing is#but it's still a great resource for nerds like me who eat this stuff up like candy#I also have a whole list of fairy tales that don't fit neatly into ATU#but that's beyond the scope of this person's ask#feel free to talk to me about fairy tales any time!#I love this stuff and I love finding people to enjoy it with!

145 notes

·

View notes

Text

ATU-130

ATU-130 manifests as a group of animals. The animals seem to be of advanced age. Manifest location is usually living quarters mainly used as hideouts of illicit of organizations. After manifesting, the animals will assault the residents, driving them out, after which they claim the residence for themselves. Regardless of the previous disposition of the ex-residents, they will be too terrified to return.

If such manifestation occurs, submit the group as a new entry in the dossier of Groups Of Interest.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

does anyone know where i can find an online version of the complete Aarne-Thompson-Uther index??

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Aaarne-Thompson-Uther Index

Animal Tales: 1 - 299

Tales in Magic: 300 - 749

Religious Tales: 750 - 849

Realisitic Tales (Set in Real Settings and Contexts): 850 - 999

Tales of the Stupid Ogre/giant/Devil: 1000 - 1199

Anecdotes & Jokes: 1200 - 1999

Formula Tales: 2000 - 2399

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Come now and listen. I know it’s exciting. Yes, this is where I grew up. Yes, I can speak-- no, the castle is over that hill, we’ll be there by morning. I’m sure your grandmother is very excited to meet you. It’s time to sleep now, or you’ll be yawning in front of the queen. Okay, one bedtime story, but only one. What was that? Why didn’t we come sooner? Well…. What now? One question at a time dove, you’re bouncing off the walls, now sit. Those are just decorations, they have a winter holiday. No. I don’t celebrate with them. Now sit, I’ll read you a story.

Yes, I’m reading it … right now, sit. I know the road is bumpy little dove, but look at all these cushions…. Are you comfortable? Okay, I’ll begin.

They tell it different in the city, but… yes, I know that’s your favorite part, now sit still.

They tell it different in the city, but when King Wouter III toured his small land for a second wife, he plucked Pietrenella out of a butcher’s line of seven daughters, born to a world that valued them only as bodies for bartering influence, wealth, children, or labor—oh, like that’s changed. I’m sorry, I know, I know, I promised. Yes, yes, I’m reading, reading only.

After a short life spent following her own mother’s instruction in beauty, and thoroughly practiced in caring for six younger siblings, Pietrenella was beyond prepared to step into the role of… mother. Is this a fairytale or a biography? Alright, don’t get sassy.

Before she was the Nation’s Mother, that quintessential figure immortalized on every facade and coin, starved thin and dragging that heroic wheelbarrow of packed… meats and broths… meats and broths? Meats… and broths? Dragging that heroic wheelbarrow of packed meats and broths… that would save them all, she was just a butcher’s daughter, accustomed to sacrifices for the greater good.

Sigh.

No, I’m not crying. I’m… no, I’m not mad at you little dove, I’m sorry for slamming the book shut. I think… I think you might be old enough to hear a secret story. Yes, I know you don’t want me to call you little dove anymore, but you still let me read you fairytales, hm? How about I tell you a different version. I know The Great Queen Pietrenella is your favorite, but I’ve got a different one for you. Yes, different like how they tell it in the city. Are you all tucked in? Sure, I can brush your hair. You’re right, it is getting very long. Sorry, I caught a tangle, I’ll be more careful, I’m sorry dove. Do you forgive me? Oh good. Alright, I’ll start from the beginning.

They tell it different in the city, but, here’s how the ghosts tell it in the castle:

Continue reading

#grimdark#fairytales#brothers grimm#grimm fairy tales#fairy tale retelling#snow white#rapunzel#sleeping beauty#horror story#girl in the tower#aarne thompson uther index#evil queen#evil step mother#cinderella#children in the woods#short story#mommy issues#once upon a time#horror#dark fantasy#fantasy story#cw death

0 notes

Text

كيف تُولِّد عددًا لا محدودًا من أفكار القصص باستخدام أداة تصنيف مُستلّة من علم الفولكلور؟

كيف تُولِّد عددًا لا محدودًا من أفكار القصص باستخدام أداة تصنيف مُستلّة من علم الفولكلور؟

مساء الخير،

عندما تنتهي من مطالعة مقال اليوم ومشاهدة الفيديو أدناه لن تقول مرّة أخرى أعطوني فكرة قصة أو لا أجد فكرة أكتب عنها قصة.

استمتع!

ما هو الفولكلور؟

يُترجم البعض كلمة folklore بـعِلْم الأوابد: عِلْم التقاليد والفنون الشعبيّة لبَلَد (المعاصر قاموس فرنسي-عربي)، في حين يترك آخرون الكلمة كما هي أي فولكلور، وهو وفق معجم المصباح (إنجليزي/عربي) فولكلور: تقاليدُ الشعب، عاداته وأساطيره…

View On WordPress

#Antti Aarne#ATU#folklore#Hans-Jörg Uther#myth#Stith Thompson#فلكلور#فنون شعبية#فولكلور#قصص شعبية#نظام تصنيف آن تومبسون أوثر#نظام تصنيف آرن تومبسون#نظام تصنيف آرن تومبسون أوثر#نظام تصنيف القصص الشعبية#أساطير شعبية#التراث الشعبية#حكايات#سرديات#علوم

0 notes

Text

Diamonds, Toads, and Dark Magical Girls

According to Bill Ellis in "The Fairy-Telling Craft of Princess Tutu: Meta-Commentary and the Folkloresque," the fairy tale of Cinderella can be seen as one of the earliest examples of the transformation sequences/henshin seen in magical girl anime, particularly in how the title character is given items that help her achieve a goal, usually given to her by a magical being (her mother's spirit in a tree, a fairy godmother, etc.).

Thinking again about the connection between magical girls and fairy tales--even if they aren't as meta as Tutu, many magical girls do use imagery and ideas from European fairy tales (Sailor Moon alone has references to Hans Christian Andersen and Charles Perrault)--I wondered what other character types from the genre may have some precedent in fairy tales. Then I started thinking about the Dark Magical Girl character.

Not every magical girl story has a Dark Magical Girl, but they do crop up in a lot of works. To name a few, there's Fate Testarossa from Magical Girl Lyrical Nanoha, Homura Akemi from Puella Magi Madoka Magica, Rue/Kraehe from Princess Tutu, and countless others that would be too numerous to name. In general they tend to be more cynical, darker counterparts to the main protagonists, who tend to come from relatively more stable environments. Whatever magic they possess also may be more sinister, at least initially.

Tying in somewhat to the story of Cinderella is the Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index fairy tale type "The Kind and Unkind Girls" (ATU 480). Many of the stories of this type involve a rivalry between two stepsisters, one being favored by the stepmother due to being the latter's biological daughter. The general idea in most versions of the tale is that both girls encounter a magical being at separate points in time. The kind girl helps the magical being in some way, at which point the magical being gives her a magical ability or magical presents. Meanwhile, the unkind girl refuses to help the magical being and is cursed in some fashion, or, worse, killed. The kind girl meanwhile usually ends up marrying a prince, or a similar character. One of the more popular versions of this story, "Diamonds and Toads," has the kind girl gain the ability to have a jewel or flower fall from her mouth when she speaks, while the unkind girl is cursed to have toads and snakes fall from hers. And while the kind girl does marry a prince, the unkind one is kicked out of her house and dies alone in the woods. (Insert something about Revolutionary Girl Utena's comment about how a girl who cannot become a princess is doomed to be a witch.)

Typically in these fairy tales, the unkind girl is never shown to be a real threat to the kind one; the ultimate threat is the stepmother, who uses her daughter as a means to an end. In contrast, Dark Magical Girls tend to have, well, magic that helps them attack the magical girl protagonist. In this regard, they're the Heavy in the plot, while the witch/mother-like figure/real enemy waits in the background (as is the case in a lot of magical girl shows--the Raven and Rue, Precia and Fate, Fine and Chris in Symphogear etc.). Sometimes the Dark Magical Girl will be a major threat, though--like the Princess of Disaster in Pretear (who is loosely-inspired by the Evil Queen in Snow White).

In The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales (1976), Bruno Bettelheim argues that the stepmother as a character is a way for children to process the negative traits of their own mothers, while still idealizing the good qualities of them. With that in mind, the unkind sister and the Dark Magical Girl can be viewed as a way of processing/externalizing the negative traits that a girl can have, being cruel, rebellious, and uncaring. They also embody their fears, too--the fear of being alone, rejected, and doomed to fail.

Of course, nowadays, Dark Magical Girls have a tendency to be redeemed and reconcile with/befriend the main magical girl, something the kind and unkind girls never seem to do in the fairy tales. Maybe it's just emblematic of society deciding that killing a girl off for being a little rude is a bit unfair. She's just a kid trying to find her place in the world, too, after all.

#magical girl#magical girl lyrical nanoha#puella magi madoka magica#princess tutu#senki zesshou symphogear#dark magical girl#fate testarossa#homura akemi#rue kuroha#princess kraehe#chris yukine#cinderella#diamonds and toads#kind and unkind girls#fairy tales#hans christian andersen#brothers grimm#charles perrault#bruno bettelheim#the uses of enchantment#random thoughts#text#read more

62 notes

·

View notes

Note

how goes the reading of the andersen tales? also, thoughts on the aarne-thompson-uther index?

I am approximately 2/3rds done, I took a break last week to read something else for a book club I’m in.

I’m not knowledgable enough about fairlytales and folklore to have any strong opinions on the ATU index besides it being interesting and helping me find similar and “related” stories. I imagine there is some controversy and messiness with it as is the case with all classification systems, but I haven’t read into it enough to know about that

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

1.

The Roud Folk Song Index lists it as the 39th Child Ballad. Comparisons to be made to Type 425 in the Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index, under the entry “The Search for the Lost Husband.” TvTropes.com has more to say on the page titled “Shapeshifting Lover.” A story iterated upon in many forms. A young woman, almost always a woman, sometimes virginal, is wedded, or falls in love with, or is taken away by a man under some sort of curse. He is horse. Or a lindworm. Or a wolf. Sometimes only at night. Sometimes only when the fairies who cursed him make him so. He is a Beast, she must undo whatever evil makes him so, normally through a kiss, true love, wedding him, or, in some of the less sanitized versions, simply sex.

1.

The first time they hooked up he cried afterwords, which she didn’t understand at the time. They were sophomores in college. It wasn’t her first time. It should have been casual. It was up until he cried in the morning. She felt so bad that she suggested they get breakfast together, when she had simply meant to leave.

At breakfast he calmed, he talked about his life. Quiet, nerdy, hiding in his hoodie. There was something vulnerable there, and she liked it. She gave him her number after.

2.

Later thinkers and writers have revisited this trope. Sometimes it is played straight, depicted on the screen by Disney. Sometimes this is (falsely I would argue) called Stockholm Syndrome. Sometimes this is, it must be said, simply used for purposes of sex and titillation. I think, however, that the continued persistence of this motif in media, it’s emotional resonance, demands further explication of its longevity. What about this appeals to us in the modern day, when we (ideally) can no longer ascribe to it a moral of young women being forced to accept arranged marriages?

2.

They’re a few months into their time dating, after long arguments about that label, when the crying returns. This time no longer after sex, but she feels the emotion is the same. You should leave me, he says. Break up. You should do it now before I hurt you, he says.

And she, not wanting to point out that she is bigger and stronger than he is, gently asks why he says something like that? In there time together he has been nothing if not careful. Thoughtful. Kind. One of the most soft and charming people she knows. He cannot explain it in any satisfying way. He simply insists that there is something dark inside him. Something he has sought to deny far too long, and will not be able to deny forever. That if she stays she will be hurt, simply as a function of loving him. He will one day lose the fight against himself.

She does not know what to do but hold him.

3.

I think some of the appeal of this trope can be found in reference to another motif of our pop cultural mythos. That of the werewolf.

We are used to seeing werewolves depicted from the viewpoint of the hunted. But there is perpetually the question of what such a transformation looks like from the viewpoint of the animal itself. A human transforming into a beast demands of a human audience that we consider what it must be like to monster. To be capable of hurting those we love. And yet, I at least wonder, if we are capable of hurting those loved ones, do we not still hope that they will love us as we transform? As we become different, monstrous in shape and utterly unknown even to them?

3.

They graduate. Together. Move into an apartment above a Taiwanese restaurant. She gets a shitty job that has health insurance for them both. He does commission from home. It’s not perfect. There is some part of him he never shares and she does her best to make peace with that. To accept that wherever his mind goes when he is watching her put on a dress, do her make up, whatever he ponders while watching the women passing by the street outside, or after they have sex, that is something he has chosen not to share.

But instead they share popcorn. And bills. And shitty inside jokes. And that time they got accidentally drunk at his mothers remarriage to Craig (fucking Craig amiright?) and got found by the staff of the hotel whose ballroom she had rented, having passed out near the punch bowl.

It’s a life. It’s their life. She tries to give him space within it.

4.

Consider again the Ballad of Tam Lin. The idea of Janet in the woods, holding onto her lover as wicked fairies transform him. To something ice cold. To something burning hot. To a horrible slimed thing writhing in her embrace. To a snarling wolf-monster, a beast of wicked claws and gnashing teeth.

Who has, at one time or another, when circumstances reveal that which we keep hidden, felt like that?

4.

She gets home unexpectedly early one spring afternoon in her late twenties. Janet from accounting somehow set fire to a microwave, which set off the sprinklers, and no one could get anything done that day. A small treat, and it validates her admittedly flash-judgment of Janet.

And as she unlocks the door, flowers in hand, she finds him in front of the closet they share, and understands the secret that has been kept from her for almost a decade.

5.

And then of course, the tales and legends end. Normally in the curse being lifted, the lover being returned to normal. Beast is a beast no more, the Lindworm is again a prince, Tam Lin may leave the woods a man. A simple ending to a simple story.

But for us living in reality? Outside of the tidy constraints of fiction? Perhaps there is no ending. Perhaps we remain a beast, remain a wolf, remain cursed, and monstrous and strange. Perhaps we endlessly transform into new, and more twisted shapes, and have only hope that our loves will hold us nonetheless. That even if we become something that may hurt them, something they may not understand, they will still love us.

5.

It is hard. It would be nice to say there are not challenges. She always thought she was bi, but the label of straight was easy, and she never had to examine it when she was with him. She keeps on stealing her dresses.

There are good times too. Times where she looks at this woman still becoming, someone she had loved for a decade and still barely knows, and sees how brightly she smiles, and feels so proud.

But it is above all else hard. The crying does not go away. Estrogen works wonders, but cannot stop dysphoria, and hurt, and pain. It is hard to love her. But she is trying. And when the fights over labels and new boundaries and shifting emotions break out, or the dread comes, or the weeping, she does what she can.

She holds her partner, no matter the form she takes.

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

To say that ‘John dressed and walked to town’ is not to give a single motif worth remembering; but to say that the hero put on his cap of invisibility, mounted his magic carpet, and went to the land east of the sun and west of the moon is to include at least four motifs – the cap [D1067.2,] [D1361.15,], the carpet [D1155,], the magic air journey [D2120,], and the marvelous land [F771.3.2,]. Each of these motifs lives on because it has been found satisfying by generations of tale-tellers.

Source: The British Columbia Folklore Society: Motif Index: What it is.

(In other words: Tropes are not bad).

#Folklore#academic study#aarne-thompson-uther index#(TV tropes for stories that existed before the invention of TV)#Indices are only useful if people actually know about them

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

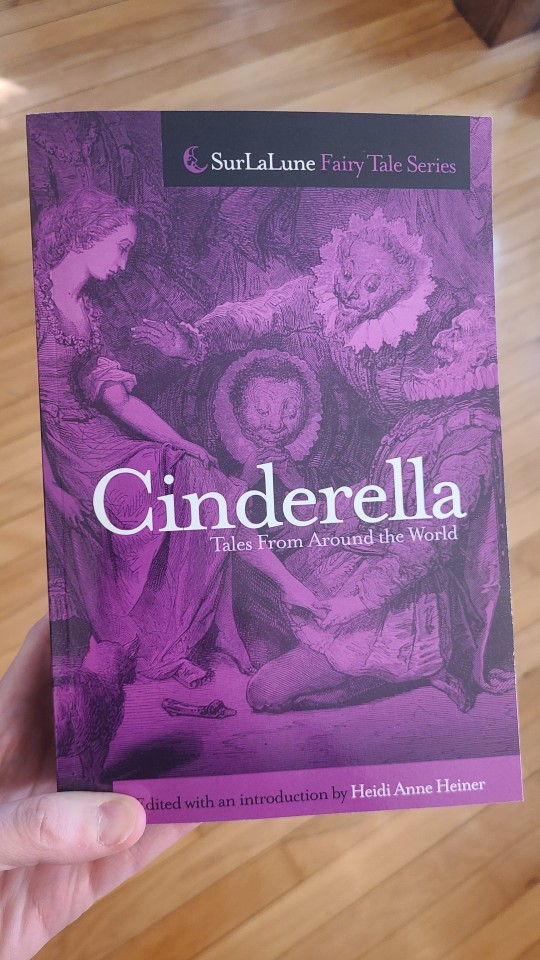

Do you think that Rey's story (excluding episode 9 'cause that was a shitshow) could be interpreted as a Cinderella/Ash girl story?

I hope you realize asking me this is like throwing chum to a shark 😈. But the short answer is yes, to a point.

The long answer is more complicated, so to begin with, let's consult the Cinderella bible:

According to the Aarne Thompson Uther Index, there are five primary motifs to a Cinderella tale:

Persecuted heroine, usually by family

Help or helper, usually magic

Meeting the prince, usually with true identity disguised

Identification or penetration of disguise, usually by means of an object

Marriage to the prince

Rey is abandoned by her family, which is a form of persecution, and harassed by the inhabitants of Jakku like Unkar Plutt. Thus she clearly fulfills the first item.

As for meeting a helper, there are several for her, including Han Solo, Maz, Luke, and Leia. Any or all of these may be considered fairy godparents in the way that they offer her wisdom and material help. Further, except for Maz, they all die in the course of the story, which is consistent with many Cinderella tales in which the helper dies and their bones continue to offer wisdom and comfort to the heroine.

Next, meeting the prince. I mean

To the extent that Rey is "in disguise' here, it would be the extent of her force powers, her destiny as Ben Solo's dyad mate, and her role as the heir apparent to the Jedi (chosen by the Force to wield the legacy saber), all of which are obscured from Kylo Ren when he discovers her in the forest. Further, she is grimy and covered in desert sand, similar to how Cinderella is smeared with ashes that hide her true beauty.

So now an object penetrates the disguise. This is obviously the Skywalker lightsaber, which reveals Rey to be everything listed above, especially when she calls it to her on Starkiller Base, and again when she wields it on Ahch-to.

And lastly, marriage to the prince. As many others have pointed out over the years, Rey and Ben have almost too many symbolic marriages to count in the course of the sequel trilogy. They're extremely married, the Force said so.

BUT WAIT! Go back and look at that list again. Who ELSE fits all those criteria?

It's our boy! Consider:

He is indeed persecuted by family, most notably when Luke momentarily considers killing him.

Ben's helpers are both dark and light, as Snoke/Palpatine guide him in the dark while Luke guides him in the light (poorly). But note again what I said above about the bones of the mentor continuing to offer guidance and comfort after their death. Who should appear at Ben's lowest hour but his departed father, Han Solo? With a message of love, acceptance, and encouragement, Han's memory (because in fairy tales, bones contain memory) encourages Ben to at last cast off his beastly skin and become who he always was.

Next, meeting the prince/ss in disguise. He's wearing a literal mask when he meets Rey, so yeah.

An object penetrates the disguise? Rey slashed his face with the legacy saber, thus symbolically peeling away his mask. And I've argued before that the stabbing in TROS (which I still HATE, btw) is another cutting or burning away of the beastly skin.

And lastly, marriage to the prince/ss. As previously stated, that happened. Many times.

So yes, the Sequel Trilogy can definitely be considered a Cinderella story, with but one glaring issue: Cinderella's husband usually doesn't die at the end. But that's another topic that's been done to death, so let's all just read some more fanfic and forget about it. 👑 Thank you for the ask, this was fun!

#reylo#reylo meta#star wars#star wars meta#sw meta#star wars sequel trilogy#sequel trilogy#sequel trilogy meta#sw sequels#rey x ben#rey of jakku#ben solo#kylo ren#cinderella#aschenputtel#fairy tale#fairy tale meta#folktales#folktale types#folktale motifs#atu 510#aarne thompson uther#han solo#luke skywalker#leia organa#maz kanata#fairy godmother#my meta

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

A class on fairy tales (1)

As you might know (since I have been telling it for quite some times), I had a class at university which was about fairy tales, their history and evolution. But from a literary point of view - I am doing literary studies at university, it was a class of “Literature and Human sciences”, and this year’s topic was fairy tales, or rather “contes” as we call them in France. It was twelve seances, and I decided, why not share the things I learned and noted down here? (The titles of the different parts of this post are actually from me. The original notes are just a non-stop stream, so I broke them down for an easier read)

I) Book lists

The class relied on a main corpus which consisted of the various fairytales we studied - texts published up to the “first modernity” and through which the literary genre of the fairytale established itself. In chronological order they were: The Metamorphoses of Apuleius, Lo cunto de li cunti by Giambattista Basile, Le Piacevoli Notti by Giovan Francesco Straparola, the various fairytales of Charles Perrault, the fairytales of Marie-Catherine d’Aulnoy, and finally the Kinder-und Hausmärchen of Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. There is also a minor mention for the fables of Faerno, not because they played an important historical role like the others, but due to them being used in comparison to Perrault’s fairytales ; there is also a mention of the fairytales of Leprince de Beaumont if I remember well.

After giving us this main corpus, we were given a second bibliography containing the most famous and the most noteworthy theorical tools when it came to fairytales - the key books that served to theorize the genre itself. The teacher who did this class deliberatly gave us a “mixed list”, with works that went in completely opposite directions when it came to fairytale, to better undersant the various differences among “fairytale critics” - said differences making all the vitality of the genre of the fairytale, and of the thoughts on fairytales. Fairytales are a very complex matter.

For example, to list the English-written works we were given, you find, in chronological order: Bruno Bettelheim’s The Uses of Enchantment ; Jack David Zipes’ Fairy Tales and the Art of Subversion ; Robert Bly’s Iron John: A Book about Men ; Marie-Louise von Franz, Interpretation of Fairy Tales ; Lewis C. Seifert, Fairy Tales, Sexuality and Gender in France (1670-1715) ; and Cristina Bacchilega’s Postmodern Fairy Tales: Gender and Narrative Strategies. If you know the French language, there are two books here: Jacques Barchilon’s Le conte merveilleux français de 1690 à 1790 ; and Jean-Michel Adam and Ute Heidmann’s Textualité et intertextualité des contes. We were also given quite a few German works, such as Märchenforschung und Tiefenpsychologie by Wilhelm Laiblin, Nachwort zu Deutsche Volksmärchen von arm und reich, by Waltraud Woeller ; or Märchen, Träume, Schicksale by Otto Graf Wittgenstein. And of course, the bibliography did not forget the most famous theory-tools for fairytales: Vladimir Propp’s Morfologija skazki + Poetika, Vremennik Otdela Slovesnykh Iskusstv ; as well as the famous Classification of Aarne Anti, Stith Thompson and Hans-Jörg Uther (the Aarne-Thompson-Uther Classification, aka the ATU).

By compiling these works together, one will be able to identify the two main “families” that are rivals, if not enemies, in the world of the fairytale criticism. Today it is considered that, roughly, if we simplify things, there are two families of scholars who work and study the fairy tales. One family take back the thesis and the theories of folklorists - they follow the path of those who, starting in the 19th century, put forward the hypothesis that a “folklore” existed, that is to say a “poetry of the people”, an oral and popular literature. On the other side, you have those that consider that fairytales are inscribed in the history of literature, and that like other objects of literature (be it oral or written), they have intertextual relationships with other texts and other forms of stories. So they hold that fairytales are not “pure, spontaneous emanations”. (And given this is a literary class, given by a literary teacher, to literary students, the teacher did admit their bias for the “literary family” and this was the main focus of the class).

Which notably led us to a third bibliography, this time collecting works that massively changed or influenced the fairytale critics - but this time books that exclusively focused on the works of Perrault and Grimm, and here again we find the same divide folklore VS textuality and intertextuality. It is Marc Soriano’s Les contes de Perrault: culture savante et traditions populaires, it is Ernest Tonnelat’s Les Contes des frères Grimm: étude sur la composition et le style du recueil des Kinder-und-Hausmärchen ; it is Jérémie Benoit’s Les Origines mythologiques des contes de Grimm ; it is Wilhelm Solms’ Die Moral von Grimms Märchen ; it is Dominqiue Leborgne-Peyrache’s Vies et métamorphoses des contes de Grimm ; it is Jens E. Sennewald’ Das Buch, das wir sind: zur Poetik der Kinder und-Hausmärchen ; it is Heinz Rölleke’s Die Märchen der Brüder Grimm: eine Einführung. No English book this time, sorry.

II) The Germans were French, and the French Italians

The actual main topic of this class was to consider the “fairytale” in relationship to the notions of “intertextuality” and “rewrites”. Most notably there was an opening at the very end towards modern rewrites of fairytales, such as Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber, “Le petit chaperon vert” (Little Green Riding Hood) or “La princesse qui n’aimait pas les princes” (The princess who didn’t like princes). But the main subject of the class was to see how the “main corpus” of classic fairytales, the Perrault, the Grimm, the Basile and Straparola fairytales, were actually entirely created out of rewrites. Each text was rewriting, or taking back, or answering previous texts - the history of fairytales is one of constant rewrite and intertextuality.

For example, if we take the most major example, the fairytales of the brothers Grimm. What are the sources of the brothers? We could believe, like most people, that they merely collected their tale. This is what they called, especially in the last edition of their book: they claimed to have collected their tales in regions of Germany. It was the intention of the authors, it was their project, and since it was the will and desire of the author, it must be put first. When somebody does a critical edition of a text, one of the main concerns is to find the way the author intended their text to pass on to posterity. So yes, the brothers Grimm claimed that their tales came from the German countryside, and were manifestations of the German folklore.

But... in truth, if we look at the first editions of their book, if we look at the preface of their first editions, we discover very different indications, indications which were checked and studied by several critics, such as Ernest Tomelas. In truth, one of their biggest sources was... Charles Perrault. While today the concept of the “tales of the little peasant house, told by the fireside” is the most prevalent one, in their first edition the brothers Grimm explained that their sources for these tales were not actually old peasant women, far from it: they were ladies, of a certain social standing, they were young women, born of exiled French families (because they were Protestants, and thus after the revocation of the édit de Nantes in France which allowed a peaceful coexistance of Catholics and Protestants, they had to flee to a country more welcoming of their religion, aka Germany). They were young women of the upper society, girls of the nobility, they were educated, they were quite scholarly - in fact, they worked as tutors/teachers and governess/nursemaids for German children. For children of the German nobility to be exact. And these young French women kept alive the memory of the French literature of the previous century - which included the fairytales of Perrault.

So, through these women born of the French emigration, one of the main sources of the Grimm turns out to be Perrault. And in a similar way, Perrault’s fairytales actually have roots and intertextuality with older tales, Italian fairytales. And from these Italian fairytales we can come back to roots into Antiquity itself - we are talking Apuleius, and Virgil before him, and Homer before him, this whole classical, Latin-Greek literature. This entire genealogy has been forgotten for a long time due to the enormous surge, the enormous hype, the enormous fascination for the study of folklore at the end of the 19th century and throughout all of the 20th.

We talk of “types of fairytales”, if we talk of Vladimir Propp, if we talk of Aarne Thompson, we are speaking of the “morphology of fairytales”, a name which comes from the Russian theorician that is Propp. Most people place the beginning of the “structuralism” movement in the 70s, because it is in 1970 that the works of Propp became well-known in France, but again there is a big discrepancy between what people think and what actually is. It is true that starting with the 70s there was a massive wave, during which Germans, Italians and English scholars worked on Propp’s books, but Propp had written his studies much earlier than that, at the beginning of the 20th century. The first edition of his Morphology of fairytales was released in 1928. While it was reprinted and rewriten several times in Russia, it would have to wait for roughly fifty years before actually reaching Western Europe, where it would become the fundamental block of the “structuralist grammar”. This is quite interesting because... when France (and Western Europe as a whole) adopted structuralism, when they started to read fairytales under a morphological and structuralist angle, they had the feeling and belief, they were convinced that they were doing a “modern” criticism of fairytales, a “new” criticism. But in truth... they were just repeating old theories and conceptions, snatched away from the original socio-historical context in which Propp had created them - aka the Soviet Union and a communist regime. People often forget too quickly that contextualizing the texts isn’t only good for the studied works, we must also contextualize the works of critics and the analysis of scholars. Criticism has its own history, and so unlike the common belief, Propp’s Morphology of fairytales isn’t a text of structuralist theoricians from the 70s. It was a text of the Soviet Union, during the Interwar Period.

So the two main questions of this class are. 1) We will do a double exploration to understand the intertextual relationships between fairytales. And 2) We will wonder about the definition of a “fairytale” (or rather of a “conte” as it is called in French) - if the fairytale is indeed a literary genre, then it must have a definition, key elements. And from this poetical point of view, other questions come forward: how does one analyze a fairytale? What does a fairytale mean?

III) Feuding families

Before going further, we will pause to return to a subject talked about above: the great debate among scholars and critics that lasted for decades now, forming the two branches of the fairytale study. One is the “folklorist” branch, the one that most people actually know without realizing it. When one works on fairytale, one does folklorism without knowing it, because we got used to the idea that fairytale are oral products, popular products, that are present everywhere on Earth, we are used to the concept of the universality of motives and structures of fairytales. In the “folklorist” school of thought, there is an universalism, and not only are fairytales present everywhere, but one can identify a common core for them. It can be a categorization of characters, it can be narrative functions, it can be roles in a story, but there is always a structure or a core. As a result, the work of critics who follow this branch is to collect the greatest number of “versions” of a same tale they can find, and compare them to find the smallest common denominator. From this, they will create or reconstruct the “core fairytale”, the “type” or the “source” from which the various variations come from.

Before jumping onto the other family, we will take a brief time to look at the history of the “folklorist branch” of the critic. (Though, to summarize the main differences, the other family of critics basically claims that we do not actually know the origin of these stories, but what we know are rather the texts of these stories, the written archives or the oral records).

So the first family here (that is called “folklorist” for the sake of simplicity, but it is not an official or true appelation) had been extremely influenced by the works of a famous and talented scholar of the early 20th century: Aarne Antti, a scholar of Elsinki who collected a large number of fairytales and produced out of them a classification, a typology based on this theory that there is an “original fairytale type” that existed at the beginning, and from which variants appeared. His work was then continued by two other scholars: Stith Thompson, and Hans-Jörg Uther. This continuation gave birth to the “Aarne-Thompson” classification, a classification and bibliography of folkloric fairytales from around the world, which is very often used in journals and articles studying fairytales. Through them, the idea of “types” of fairytales and “variants” imposed itself in people’s minds, where each tale corresponds to a numbered category, depending on the subjects treated and the ways the story unfolds (for example an entire category of tale collects the “animal-husbands”. This classification imposed itself on the Western way of thinking at the end of the first third of the 20th century.

The next step in the history of this type of fairytale study was Vladimir Propp. With his Morphology of fairytales, we find the same theory, the same principle of classification: one must collect the fairytales from all around the world, and compare them to find the common denominator. Propp thought Aarne-Thompson’s work was interesting, but he did complain about the way their criteria mixed heterogenous elements, or how the duo doubled criterias that could be unified into one. Propp noted that, by the Aarne-Thompson system, a same tale could have two different numbers - he concluded that one shouldn’t classify tales by their subject or motif. He claimed that dividing the fairytales by “types” was actually impossible, that this whole theory was more of a fiction than an actual reality. So, he proposed an alternate way of doing things, by not relying on the motifs of fairytales: Propp rather relied on their structure. Propp doesn’t deny the existence of fairytales, he doesn’t put in question the categorization of fairytales, or the universality of fairytales, on all that he joins Aarne-Thompson. But what he does is change the typology, basing it on “functions”: for him, the constituve parts of fairytales are “functions”, which exist in limited numbers and follow each other per determined orders (even if they are not all “activated”). He identified 31 functions, that can be grouped into three groups forming the canonical schema of the fairytale according to Propp. These three groups are an initial situation with seven functions, followed by a first sequence going from the misdeed (a bad action, a misfortune, a lack) to its reparation, and finally there is a second sequence which goes from the return of the hero to its reward. From these seven “preparatory functions”, forming the initial situation, Propp identified seven character profiles, defined by their functions in the narrative and not by their unique characteristics. These seven profiles are the Aggressor (the villain), the Donor (or provider), the Auxiliary (or adjuvant), the Princess, the Princess’ Father, the Mandator, the Hero, and the False Hero. This system will be taken back and turned into a system by Greimas, with the notion of “actants”: Greimas will create three divisions, between the subject and the object, between the giver and the gifted, and between the adjuvant and the opposant.

With his work, Vladimir Propp had identified the “structure of the tale”, according to his own work, hence the name of the movement that Propp inspired: structuralism. A structure and a morphology - but Propp did mention in his texts that said morphology could only be applied to fairytales taken from the folklore (that is to say, fairytales collected through oral means), and did not work at all for literary fairytales (such as those of Perrault). And indeed, while this method of study is interesting for folkloric fairytales, it becomes disappointing with literary fairytales - and it works even less for novels. Because, trying to find the smallest denominator between works is actually the opposite of literary criticism, where what is interesting is the difference between various authors. It is interesting to note what is common, indeed, but it is even more interesting to note the singularities and differences. Anyway, the apparition of the structuralist study of fairytales caused a true schism among the field of literary critics, between those that believe all tales must be treated on a same way, with the same tools (such as those of Propp), and those that are not satisfied with this “universalisation” that places everything on the same level.

This second branch is the second family we will be talking about: those that are more interested by the singularity of each tale, than by their common denominators and shared structures. This second branch of analysis is mostly illustrated today by the works of Ute Heidmann, a German/Swiss researcher who published alongside Jean Michel Adam (a specialist of linguistic, stylistic and speech-analysis) a fundamental work in French: Textualité et intertextualité des contes: Perrault, Apulée, La Fontaine, Lhéritier... (Textuality and intertextuality of fairytales). A lot of this class was inspired by Heidmann and Adam’s work, which was released in 2010. Now, this book is actually surrounded by various articles posted before and after, and Ute Heidmann also directed a collective about the intertextuality of the brothers Grimm fairytales. Heidmann did not invent on her own the theories of textuality and intertextuality - she relies on older researches, such as those of the Ernest Tonnelat, who in 1912 published a study of the brothers Grimm fairytales focusing on the first edition of their book and its preface. This was where the Grimm named the sources of their fairytales: girls of the upper class, not at all small peasants, descendants of the protestant (huguenots) noblemen of France who fled to Germany. Tonnelat managed to reconstruct, through these sources, the various element that the Grimm took from Perrault’s fairytales. This work actually weakened the folklorist school of thought, because for the “folklorist critics”, when a similarity is noted between two fairytales, it is a proof of “an universal fairytale type”, an original fairytale that must be reconstructed. But what Tonnelat and other “intertextuality critics” pushed forward was rather the idea that “If the story of the Grimm is similar but not identical to the one of Perrault, it is because they heard a modified version of Perrault’s tale, a version modified either by the Grimms or by the woman that told them the tale, who tried to make the story more or less horrible depending on the situation”. This all fragilized the idea of an “original, source-fairytale”, and encouraged other researchers to dig this way.

For example, the case was taken up by Heinz Rölleke, in 1985: he systematized the study of the sources of the Grimm, especially the sources that tied them to the fairytales of Perrault. Now, all the works of this branch of critics does not try to deny or reject the existence of fairytales all over the world. And it does not forget that all over the world, human people are similar and have the same preoccupations (life, love, death, war, peace). So, of course, there is an universality of the themes, of the motives, of the intentions of the texts. Because they are human texts, so there is an universality of human fiction. But there is here the rejection of a topic, a theory, a question that can actually become VERY dangerous. (For example, in post World War II Germany, all researches about fairytales were forbidden, because during their reign the Nazis had turned the fairytales the Grimm into an abject ideological tool). This other family, vein, branch of critics, rather focuses on the specificity of each writing style, of each rewrite of a fairytale, but also on the various receptions and interpretations of fairytales depending on the context of their writing and the context of their reading. So the idea behind this “intertextuality study” is to study the fairytales like the rest of literature, be it oral or written, and to analyze them with the same philological tools used by history studies, by sociology study, by speech analysis and narrative analysis - all of that to understand what were the conditions of creation, of publication, of reading and spreading of these tales, and how they impacted culture.

#fairy tales#fairytales#fairytale#fairy tale#a class on fairytales#brothers grimm#grimm fairytales#charles perrault#perrault fairytales#history of fairytales#vladimir propp#aarne-thompson classification#aarne-thompson#analysis of fairytales#critics of fairytales#book reference#sources#fairytale research#literary vs folklorist#which actually should be more intertextuality vs folklorist

105 notes

·

View notes

Note

What do you think about Aarne-Thompson-Uther tale type 2301 "corn carried away one grain at a time"? It's one of my favorites.

I had never heard of this story until now, so I looked it up. I like it. There's not a lot of substance to it, but it's funny.

Here's an example, for anyone else who doesn't know it:

Once upon a time there was a king who had a very beautiful daughter. Many princes wished to marry her, but the king said she should marry the one who could tell him an endless tale, and those lovers that could not tell an endless tale should be beheaded.

Many young men came, and tried to tell such a story, but they could not tell it, and were beheaded. But one day a poor man who had heard of what the king had said came to the court and said he would try his luck. The king agreed, and the poor man began his tale in this way:

"There was once a man who built a barn that covered many acres, and that reached almost to the sky. He left just one little hole in the top, through which there was only room for one locust to creep in at a time, and then he filled the barn full of corn to the very top. When he had filled the barn there came a locust through the hole in the top and fetched one grain of corn, and then another locust came and fetched another grain of corn."

And so the poor man went on saying, "Then another locust came and fetched another grain of corn," for a long time, so that in the end the king grew very weary, and said the tale was endless, and told the poor man he might marry his daughter.

It reminds me of "Jack's Story" from The Stinky Cheese Man and Other Fairly Stupid Tales:

"Once upon a time there was a Giant. The Giant squeezed Jack and said, 'Tell me a better story, or I will grind your bones to make my bread. And when your story is finished, I will grind your bones to make my bread anyway! Ho, ho, ho.' The Giant laughed an ugly laugh. Jack thought 'He'll kill me if I do. He'll kill me if I don't. There's only one way to get out of this.' Jack cleared his throat, and then began his story. 'Once upon a time there was a Giant. The Giant squeezed Jack and said'..."

And so on and so on until the Giant falls asleep.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

gimmick blog that assignes aarne-thompson-uther types to posts

51 notes

·

View notes