#Stone Othor

Text

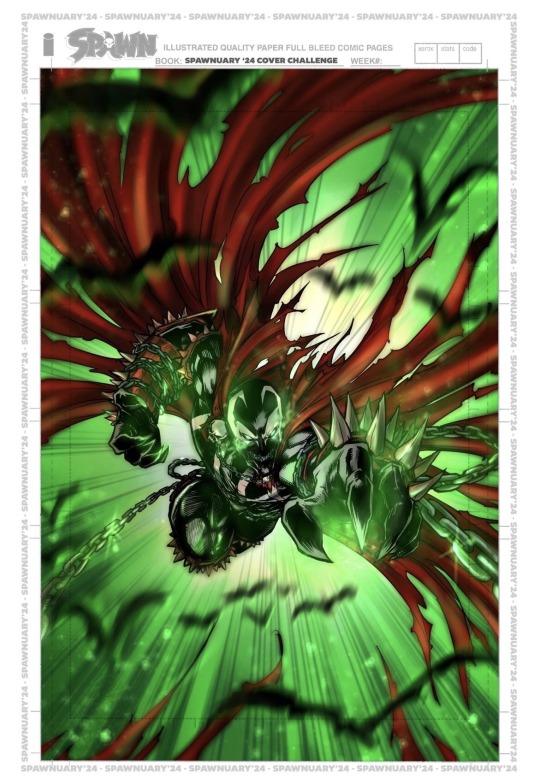

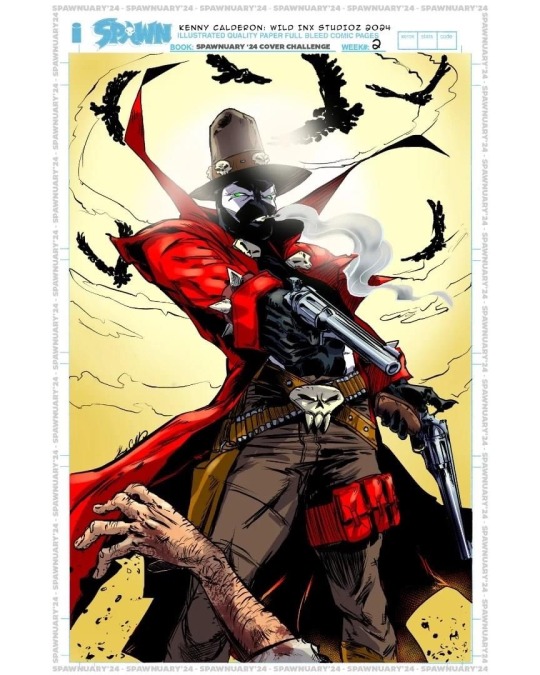

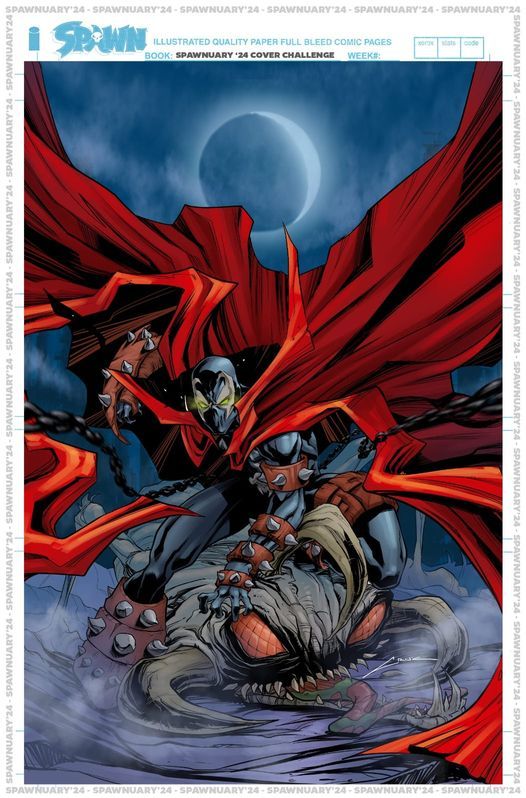

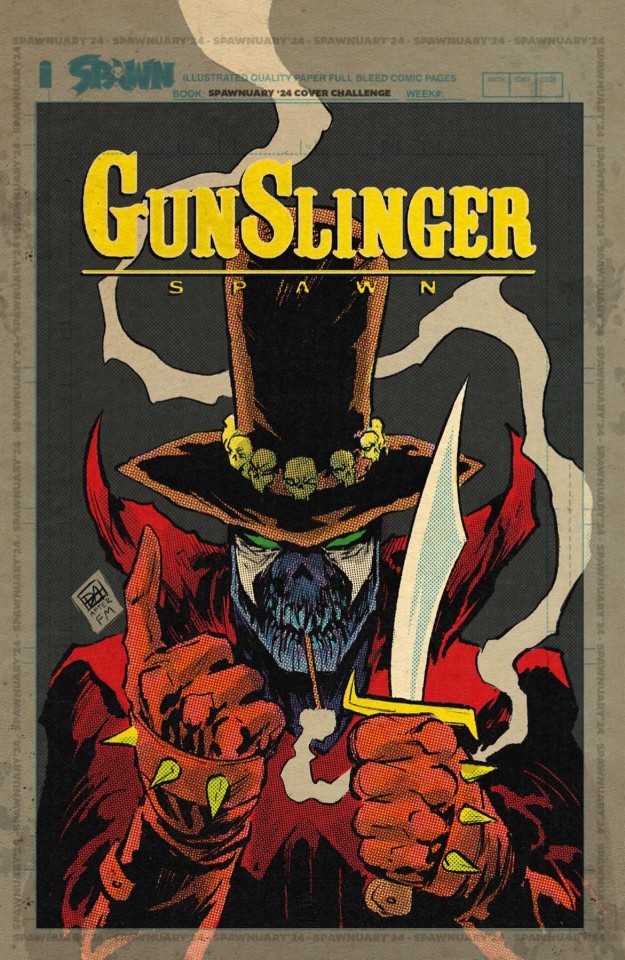

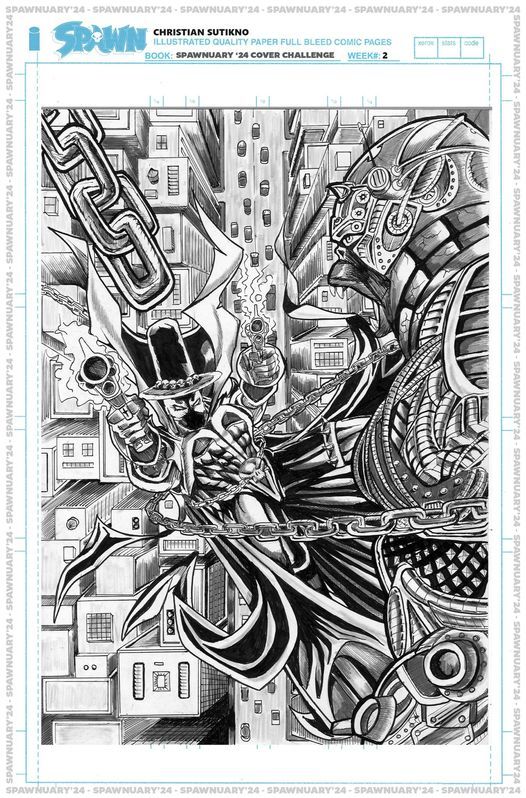

Spawnuary Covers

Cover By Francisco Javier Vazquez Delgado

Cover By Stone Othor

Cover By Manú Silva colour By Dan Kemp

Cover By Mico Suayan

Cover By Bill Scarpitti

Cover By Greg Bain

Cover By Loc Nguyen

Cover By Garrie Gastonny

Covers By Kenny Calderon

Cover By Zach Raw

Cover By Andres Cruz

Cover By Emory Covarrubias

Cover By Dylan Andrews

Cover By Jc Fabul

Cover By Christian Gunners

#spawnuary#todd mcfarlane#image comics#spawn#variant cover#history making#breaking records#spawns universe#Francisco Javier Vazquez Delgado#Stone Othor#manu silva#dan kemp#mico suayan#Bill Scarpitti#Greg Bain#Loc Nguyen#Garrie Gastonny#Kenny Calderon#Zach Raw#Andres Cruz#Emory Covarrubias#Dylan Andrews#Jc Fabul#Christian Gunners

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pyp grinned. "The Night's Watch is thousands of years old," he said, "but I'll wager Lord Snow's the first brother ever honored for burning down the Lord Commander's Tower."

The others laughed, and even Jon had to smile. The fire he'd started had not, in truth, burned down that formidable stone tower, but it had done a fair job of gutting the interior of the top two floors, where the Old Bear had his chambers. No one seemed to mind that very much, since it had also destroyed Othor's murderous corpse.

-AGOT, Jon VIII

what else could he be honored for that is considered. hmm. dishonorable. (something ... stabby? betrayal-related?)

And the honor is a place in the Gift?

#jon snow#steel as a reward for burning something#and then someone else burns something and he repays them with steel#stark v targ

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Game of Thrones - 52 JON VII (pages 533-548)

Sam shows his senior how to CSI properly, then Jon attacks Alliser after being provoked following news from King's Landing, and has to break out of his unlocked prison cell to fight a (small) zombie invasion.

The Reader, having just done mortal combat with an unkillable cockroach the size of a small mouse, knows that feels.

-

My uncle's men, Jon thought numbly. He remembered how he'd pleaded to ride with them. Gods, I was such a green boy. If he had taken me, it might be me lying here...

No might about it. It's good that you understand, but Jon? 'Was,' maybe get a winter on the Wall under your belt before you start calling yourself a seasoned man?

Last night, he had dreamt the Winterfelldream again. He was wandering the empty castle, searching for his father, descending into the crypts. Only this time the dream had gone further than before. In the dark he'd heard the scrape of stone on stone. When he turned he saw that the vaults were opening, one after the other. As the dead kings came stumbling from their cold black graves, Jon had woken in pitch dark, his heart hammering.

"force vision or inner turmoil" = 🥛

... wait... Is that really how you spell dreamt? I thought it was spelled 'dreampt'? hang on a tic. ... 'dreamed or dreamt-' blah blah blah... oh here we go: 'dreampt is an example of a phonetic intrusion that has fallen out of use but can be found in Shakespeare'

Huh, cool beans. So the correct spelling is dreamt, but because of how mouths work, the p just kind of invites itself along sometimes in audio.

"I can't look," he whispered miserably.

"You have to look," Jon told him, keeping his voice low so the others would not hear. "Maester Aemon sent you to be his eyes, didn't he? What good are eyes if they're shut?"

"Yes, but... I'm a coward, Jon."

Jon put a hand on Sam's shoulder. "We have a dozen rangers with us, and the dogs, even Ghost. No one will hurt you, Sam. Go ahead and look. The first look is the hardest."

I love how gentle and compassionate Jon is being with Sam. It's one thing to say "I know my friend's flaws, and I accommodate them," but it's another to actually care to do that. He could have tried to subtly bully Sam into it, but he's taking the time and effort to give Sam support, and making sure to keep it private to limit an external embarrassment.

I especially appreciate it after his last chapter. Growth is not always linear in one direction.

Squatting by the dead man he had named Jafer Flowers, Ser Jaremy grasped his head by the scalp. The hair came out bewteen his fingers, brittle as straw. (...) A great gash in the side of the corpse's neck opened like a mouth, crusted with dried blood. (...) "This was done with an axe."

CSI: The Wall

I like that they're actually taking the time to try and figure out what happened, instead of assuming it was wildings (though they do suspect that.)

No offense Waymar Royce, it's just cooler when Ser Jaremy does it.

Yet his eyes were still open. They stared up at the sky, blue as sapphires.

And what colour were they before he left for the ranging? Cause buddy, I've heard somethings about corpses with blue eyes north of the Wall.

"-The corpses are still fresh, they can't have been dead more than a day..."

"No," Samwell Tarly squeaked.

Ser Jaremy: I know how to do my job, what would you know?

Jon: Hey, shut up

Mormont: Yeah, shut up. Not You Sam you're a delight, tell us everything.

Sam: *explains why these corpses are old and weird*

Jon: Oh snap, he's right, these are super cursed.

"-They haven't been chewed or eaten by animals... only Ghost... otherwise they're... they're..."

"Untouched," Jon said softly. "And Ghost is different. the dogs and the horses won't go near them."

So proud of Sam for speaking up because he knew he was right, even though he was so scared. So proud of Mormont for giving him the chance to speak.

"And might be I'm a fool, but I don't know that Othor never had no blue eyes afore."

Ser Jaremy, looked startled. "Neither did Flowers, he blurted, turning to stare at the dead man.

OOOOooooohhhHHHH!!!!!!

"Burn them," someone whispered. On of the rangers; Jon could not have said who. "Yes, burn them," a second voice urged.

The Old Bear gave a stubborn shake of his head. "Not yet. I want Maester Aemon to have a look at them. We'll bring them back to the Wall."

Poor Mormont, it's gotta be tough being the guy who would make a sensible decision that gets your whole team killed in a zombie apocalypse.

Obviously he doesn't actually get his whole team killed, and this isn't really a zombie apocalypse (except that it is), but this is a sensible decision that could prove very useful scientifically, if it doesn't all go terribly wrong. Which it will, because of zombie apocalypse rules, sorry buddy.

His guard was sprawled bonelessly across the narrow steps, looking up at him. Looking up at him, even though he was lying on his stomach. His head had been twisted completely around.

Oh Snap!

One thing I love about sprawling stories like this, is when one plot line is experiencing a completely different genre than the others. South of the Wall, and South Proper, it's all court dramas and political intrigue strung through with a few murder mysteries and (civil?) war, over East we've got a magical horse girl who's about to start a revolution, but with the Night's Watch we have Tower Defense Zombie Apocalypse!!!

When Jon opened his mouth to scream, the wight jammed its back corpse fingers into Jon's mouth. Gagging, he tried to shove it off, but the dead man was too heavy. Its hand forced itself farther down his throat, icy cold, choking him.

Oh, now that's interesting. And terrifying.

But it makes it seem like the wight is trying to 'infect' Jon from the inside out. Realistically (I say of a magical zombie attack) it's probably just trying to kill him quietly by freezing shut his throat and gagging him at the same time, but the imagery is interesting. And disturbing in its phrasing of the assault in a very specific way.

I would also like to point out that "its back corpse fingers" is not my typo, that's how it appears in my copy of the book. Page 547. I am assuming it was meant to be "It's black corpse fingers" because earlier the narrative made a point of us knowing the corpses' hands were black. (I've likely made plenty of other typos during this daily live blog, but that was not one of them.)

The direwolf wrenched free and came to him as the wight struggled to rise, dark snakes spilling from the great wound in its belly. Jon plunged his hand into the flames, grabbed a fistful of burning drapes, and whipped them at the dead man. Let it burn, he prayed as the cloth smothered the corpse, gods, please, please, let it burn.

Excuse me a minute.

AAAAAAAAAA. YAAAASSSSSSSSSSSSSS KILL IT WITH FIRE!!!!!!!!!1

Ahem, where was I?

Good, quick thingking from Jon, excellent tag team from Ghost, amazing adaptability from them both. Poor Mormont has no clue what the hell just happened, though.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Operation Stumpy Re-Read

ACOK: Jon IV (Chapter 34)

Good luck everyone.

The wildlings called it the Fist of the First Men, rangers said. It did look like a fist, Jon Snow thought, punching up through earth and wood, its bare brown slopes knuckled with stone.

Sounds exactly like Storm’s End.

Of towers, there was but one, a colossal drum tower, windowless where it faced the sea, so large that it was granary and barracks and feast hall and lord's dwelling all in one, crowned by massive battlements that made it look from afar like a spiked fist atop an upthrust arm. - Catelyn III, ACOK

+.+

So the command was given, and the brothers of the Night's Watch raised their camp behind the stone ring the First Men had made. Black tents sprouted like mushrooms after a rain, and blankets and bedrolls covered the bare ground.

Alright George, what are you up to?

The steel points of pikes flamed red with sunlight, as if already blooded, while the pavilions of the knights and high lords sprouted from the grass like silken mushrooms. - Catelyn II, ACOK

+.+

One moment Jon was striding beneath the trees, whistling and shouting, alone in the green, pinecones and fallen leaves under his feet; the next, the great white direwolf was walking beside him, pale as morning mist.

Something is dead? Something is dead.

The nightfires had burned low, and as the east began to lighten the immense mass of Storm's End emerged like a dream of stone while wisps of pale mist raced across the field, flying from the sun on wings of wind. Morning ghosts, she had heard Old Nan call them once, spirits returning to their graves. - Catelyn III, ACOK

+.+

But when they reached the ringfort, Ghost balked again. He padded forward warily to sniff at the gap in the stones, and then retreated, as if he did not like what he'd smelled. Jon tried to grab him by the scruff of his neck and haul him bodily inside the ring, no easy task; the wolf weighed as much as he did, and was stronger by far. "Ghost, what's wrong with you?" It was not like him to be so unsettled.

Jon, pay attention! Something dead is there! Right now!

+.+

When the wind blew, he could hear the creak and groan of branches older than he was. A thousand leaves fluttered, and for a moment the forest seemed a deep green sea, storm-tossed and heaving, eternal and unknowable.

Apparently not just the dead, something else is lurking as well.

Children of the forest? Bloodraven? ...Bran?

+.+

The Old Bear was particular about his hot spiced wine. So much cinnamon and so much nutmeg and so much honey, not a drop more. Raisins and nuts and dried berries, but no lemon, that was the rankest sort of southron heresy

Lulz.

Is lemon forbidden, Jon? Is it blasphemous to have the lemon? Is a little taste of lemon a vile sin to the old gods and new? Jon it will be okay, have some lemon.

+.+

"I do not mean to risk the Frostfangs unless I must," said Mormont. "Wildlings can no more live on snow and stone than we can.

What a ridiculous thing to say.

+.+

"If the rangers must stay in sight of the Fist, I don't see how they can hope to find my uncle," Jon admitted.

(...)

The answer was there. "Is it . . . it seems to me that it might be easier for one man to find two hundred than for two hundred to find one."

It’s Benjen, isn’t it? Benjen is there?

+.+

If Ben Stark is alive and free, he will come to us, I have no doubt."

"Yes," said Jon, "but . . . what if . . ."

". . . he's dead?" Mormont asked, not unkindly.

Jon nodded, reluctantly.

"Dead," the raven said. "Dead. Dead."

"He may come to us anyway," the Old Bear said. "As Othor did, and Jafer Flowers. I dread that as much as you, Jon, but we must admit the possibility."

"Dead," his raven cawed, ruffling its wings. Its voice grew louder and more shrill. "Dead."

HE CAME. BENJEN IS THERE. AND HE’S DEAD. THE RAVEN SAID SO.

+.+

Dywen was holding forth, spoon in hand. "I know this wood as well as any man alive, and I tell you, I wouldn't care to ride through it alone tonight. Can't you smell it?"

(...)

The forester sucked on his spoon a moment. He had taken out his teeth. His face was leathery and wrinkled, his hands gnarled as old roots. "Seems to me like it smells . . . well . . . cold."

"Your head's as wooden as your teeth," Hake told him. "There's no smell to cold."

There is, thought Jon, remembering the night in the Lord Commander's chambers. It smells like death.

LOOK. Something dead is there! Right at that moment! IT’S BENJEN.

Also,

The light of the half-moon turned Val's honey-blond hair a pale silver and left her cheeks as white as snow. She took a deep breath. "The air tastes sweet."

"My tongue is too numb to tell. All I can taste is cold." - Jon VIII, ADWD

Lmaooo

+.+

A sound rose out of the darkness, faint and distant, but unmistakable: the howling of wolves. Their voices rose and fell, a chilly song, and lonely. It made the hairs rise along the back of his neck.

Uh oh, the wolves are howling. Why? Why are the wolves howling? That’s never good. Don’t we want to find the weapons?

+.+

The direwolf circled the fire, sniffing Jon, sniffing the wind, never still. It did not seem as if he were after meat right now. When the dead came walking, Ghost knew. He woke me, warned me. Alarmed, he got to his feet. "Is something out there? Ghost, do you have a scent?"

Obsidian doesn’t have a scent, but Benjen sure does!

+.+

The trees stood beneath him, warriors armored in bark and leaf, deployed in their silent ranks awaiting the command to storm the hill. Black, they seemed . . . it was only when his torchlight brushed against them that Jon glimpsed a flash of green.

WHAT? This is making my brain disintegrate.

Normally I’d love a description of an army of trees ready for battle, but this feels threatening. Black, then Jon glimpsed a flash of green?

+.+

He could hear the wind whistling through cracks in the rocks as they neared the ringwall.

(...)

Faintly, he heard the sound of water flowing over rocks. Ghost vanished in the underbrush. Jon struggled after him, listening to the call of the brook, to the leaves sighing in the wind. Branches clutched at his cloak, while overhead thick limbs twined together and shut out the stars.

(...)

He followed, angry, holding the torch out low so he could see the rocks that threatened to trip him with every step, the thick roots that seemed to grab at his feet, the holes where a man could twist an ankle. Every few feet he called again for Ghost, but the night wind was swirling amongst the trees and it drank the words.

BRAN? Or Bloodraven? Why are the trees trying to stop him? Doesn’t it seem that way? The trees are clutching and grabbing!

The trees are obstructing...

But Ghost is leading forward...

But the wolves are howling...

WHAT’S GOING ON.

+.+

"What have you found?" Jon lowered the torch, revealing a rounded mound of soft earth. A grave, he thought. But whose?

He knelt, jammed the torch into the ground beside him. The soil was loose, sandy. Jon pulled it out by the fistful. There were no stones, no roots. Whatever was here had been put here recently.

Soft earth, loose soil! When you say recently I hope you realize it was a minute ago.

+.+

He saw a dozen knives, leaf-shaped spearheads, numerous arrowheads. Jon picked up a dagger blade, featherlight and shiny black, hiltless. Torchlight ran along its edge, a thin orange line that spoke of razor sharpness. Dragonglass. What the maesters call obsidian. Had Ghost uncovered some ancient cache of the children of the forest, buried here for thousands of years? The Fist of the First Men was an old place, only . . .

Beneath the dragonglass was an old warhorn, made from an auroch's horn and banded in bronze. Jon shook the dirt from inside it, and a stream of arrowheads fell out. He let them fall, and pulled up a corner of the cloth the weapons had been wrapped in, rubbing it between his fingers. Good wool, thick, a double weave, damp but not rotted. It could not have been long in the ground. And it was dark. He seized a handful and pulled it close to the torch. Not dark. Black.

Even before Jon stood and shook it out, he knew what he had: the black cloak of a Sworn Brother of the Night’s Watch.

BENJEN.

Or Coldhands. Most will say Coldhands. I get it, you all think it’s Coldhands. I accept that.

BUT WHAT IF IT’S BENJEN? Why all that talk of Benjen? Lots and lots of Benjen! Please indulge me a little, and tell me this could be Benjen.

For the record, I think the idea of a magic horn is equally as misleading as a magic sword.

Final thoughts:

Trees and the colour green dominate the last two chapters. There’s 12 mentions of green altogether, and all of it seemingly loaded with symbolism.

What it’s symbolizing, I couldn’t tell you.

-> return to menu <-

80 notes

·

View notes

Note

Whenever there is mention of black blood it's associated with death, evil, corruption and rotten. Drogo wound have black blood, Othor after becoming wight described to have blood as black dust. Robert Strong had black blood and Drogon is described to have black blood. In Theon's dream when he running from wolves, he described their faces of boys dripping black blood. Craster has been described as having black blood. In Bran vision there was a giant with stone armour and black blood.

The guy Ygritte murders at Queenscrown also bled black blood (in the darkness of the stormy night).

So, yeah, there seems to be a bit of a theme. Death and betrayal and corruption.

The only notable discrepancy that comes to my mind is this one:

You might say as Benjen Stark is why we're talking, though. His blood ran black. Made him my brother as much as yours. It's for his sake I'm come. Rode hard, I did, near killed my horse the way I drove her, but I left the others well behind." (AGOT, Arya III)

Yoren is a fairly sympathetic, downright heroic character. Benjen is more ambivalent (to me), but I guess you could say that the Night's Watch in and of itself is a problematic, rotten institution. Craster's "black blood" is actually referring to his NW ranger father, after all.

I suppose Yoren's words could be taken as a bad omen for all of them: Benjen, Yoren and Ned.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

jon throwing the burning drapes on othor, dany having drogon burn the slave master, tyrion thrusting the torch at the stone man... the lightbringers...

#seriously tyrion stepping between aegon and the stone man is one of my favorite moments#asoiaf#jon snow#daenerys stormborn#tyrion lannister

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the other side of Jon VIII, Jon gets a massive reality check as he realizes that the dead men they’ve just found are in fact the men who rode out with Benjen, thinking to himself, “Gods, I was such a green boy. If he had taken me, it might be me lying here...”

Jon is just now beginning to understand the very real dangers of the Night’s Watch, and that Benjen was correct to refuse to take him along on that ranging; Jon is in no way prepared for what lies beyond the Wall.

We also see that the Watch’s hounds refused to scent the severed hand to find the bodies, suggesting that they can smell the corruption of the Others upon them, though the humans are oblivious to this.

Jon had a nightmare the night before wherein he saw the dead rising from the crypts of Winterfell, rolling back the stones of their tombs. Whether this is foreshadowing that the dead will someday rise at Winterfell, or that these dead men will rise by the end of this chapter, the themes of resurrection and dark magic are pretty strong.

Jeor is infuriated that the men were killed so close to the Wall, and blames Ser Jaremy for not hearing any alarm the men might have raised, though Jaremy points out Mormont has been commanding them to stay close to the Wall during their patrols for a while now.

The dead Othor’s eyes are ‘blue as sapphires’; it’s not clear if he had blue eyes while he was living or not.

The brothers assume it must have been wildlings, while Jon thinks briefly of the Others, then dismisses it as a fairy tale to scare children.

We also get the reveal in this chapter that it has been six months since Jon came to Castle Black and Benjen left on his ranging, which is honestly surprising, given how vaguely time’s passing is addressed in Jon’s chapters. I had initially thought it was only about three or four months since Jon came to the Wall.

Jaremy estimates the corpses have only been dead for a day, but Sam finally summons up the nerve to disagree, and makes the point that they must have been dead for longer than that, given the condition of their congealing and clotted black blood. Still, the corpses aren’t rotting, even though it shouldn’t really be cold enough to preserve them. The corpses are also untouched by animals, and there is no blood around the scene.

Finally Dwyen points out that Othor’s eyes were not, in fact, blue before he died.

The rangers urge Mormont to burn the dead men immediately, but he insists on bringing them back for Maester Aemon to inspect.

It’s also unnaturally warm; a spirit summer that the older brothers claim means that summer is finally coming to an end, and the autumn approaching. Jon knows this winter will be a very long one, since the summer lasted ten years, beginning when he was just a small child.

Much as Bran’s last chapter had Old Nan telling him about the Others, now Jon thinks of that same story again, of how the Others “hated iron and fire and the touch of the sun and every living creature with hot blood in its veins”. The Others don’t have any particular agenda or cause in the stories; they just want to destroy humanity and all living life out of sheer hatred and malice.

Upon returning to the Wall, Jon can sense something is wrong; there’s been a letter, and Robert is dead. Curiously, everyone keeps acting like that has something to do with Jon and his father, and Jon thinks that if Robert is dead, Ned will soon be returning home with the girls. He wonders if he could visit them, and resolves to ask Ned once and for all, to his face, about his mother and who she was.

Mormont summons Jon and reveals that Ned has been imprisoned for treason; Jon is horrified and in disbelief that his father could ever do such a thing. We also get Mormont telling Jon that, “The things we love destroy us every time, lad.”, citing Robert’s love of hunting and Jorah’s love for Lynesse leading them both to ruin. But Jeor is wrong. Robert and Jorah made their choices; the hunt didn’t kill Robert, and Lynesse didn’t make Jorah a slaver. Loving something or someone doesn’t make it a weakness, but how we choose to react to it might.

Jon even has a moment of doubt in Ned; if he dishonored himself with a bastard, could he also have dishonored himself with treason against Joffrey?

Mormont insists he will write, requesting Ned be allowed to take the black; despite not wanting Ned to die, this thought makes Jon uncomfortable, and he questions whether Joffrey, with his contempt for the Starks, would even allow it.

Jon is also furious with Catelyn for taking Tyrion captive, blaming her for Ned’s imprisonment and possible death, though this isn’t true; Catelyn capturing Tyrion was not the impetus for Ned’s imprisonment; Baelish’s betrayal was.

Mormont reminds Jon he is now a brother of the Watch, and whatever happens to his family is no longer his concern, but Jon struggles to reconcile this. It was easy to pretend he was no longer related to the Starks when everything was fine, but now that his father and sisters are in danger, obviously everything is much harder.

Walking with Ghost, he thinks of how Sansa and Arya are without their wolves, and how defenseless they might be without them for protection.

But it is really heartwarming to see Jon’s friends rally around him, assuring him they believe in his father, lighting candles for him in the sept and offering to pray to the old gods with him for Ned’s sake.

That’s immediately undercut when Jon hears Thorne mocking Ned and calling Jon a ‘traitor’s bastard’, and Feral Jon makes his first real appearance as Jon leaps up onto the table with his dagger, and tries to slash Thorne’s face open.

After this, Jon is locked up in a cell for the night, where he wakes to find Ghost alarmed, his guard dead, and a hooded corpse attempting to murder Mormont in his sleep. Jon recognizes the dead man as Othor, and attempts to subdue him with Ghost, but nothing works until Mormont wakes and lights his lamp, and Jon realizes he has to burn the wight, which he does by setting the drapes on fire and throwing them on Othor.

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

[ calm ] your muse telling mine to ‘ just breathe ‘ . (from Beric)

non-sexual acts of dominance (accepting) // @tymptir[ calm ] Beric telling Jon to ‘ just breathe ‘

how long has he been stood here for? two minutes? two hours? all his life? he’s exhausted, admittedly, but sleep won’t come… not even nightmares seem to want anything to do with him, tonight, and Jon isn’t certain whether this makes for a curse or a blessing. all he knows is that, whilst the rest of the castle sleeps, his steps carried him first to the godswood and from there to the crypts, and now he stands before his brother’s statue; rival and best friend and constant companion. the Young Wolf. rightful King in the North. Eddard Stark’s firstborn and heir. tell Robb that i’m going to command the Night’s Watch and keep him safe, so he might as well take up needlework with the girls and have Mikken melt down his sword for horseshoes.

gods, what a butchery he made out of that… in the end, he could not do anything for Robb. nor for Arya. nor for Rickon. their father. Bran and Sansa and even Lady Catelyn. king, they used to call him, and now warden, and lord commander afore both, and some sort of god and the man who returned from the dead… yet Jon feels nothing if not like a complete and utter FAILURE. for what good are titles and words of praise, when most your loved ones now lie buried around you and all you’re left with are memories and faces carved out of stone? what good is to be the one who lives and survives, when they were not given the same miracle?

it is a cruel space of mind to be at, the bastard knows, and it will bring him no good… there’s WAR to prepare for, and pitying himself won’t quench the Night King’s thirst for destruction. yet sometimes it is difficult to stop the torrent of thoughts and emotions once they start, and right now is one of those moments. dark greys fall shut and he can see it all so vividly… Ygritte’s body in his arms, the arrow sprouting from Rickon’s torso, dead Othor’s burning blue eyes as he wrapped black fingers around his neck, the corpses piling up on top of him and covering the skies and making him struggle to breathe and the stench of blood and death and dying all around him, and the impossibly sharp sting of frozen water consuming his bones as he struggles to breathe and only sucks in more and more water whilst desperately trying to knock the wights off him— …and, suddenly, a loud gasp and a hand on his shoulder to bring him back to reality. softly trembling, and needing a moment to remind himself where he truly is, Jon turns to find Beric’s gentle smile staring back — whispering words of tranquility, guiding him back and away from the grasp of all his inner demons. and he closes his eyes again, waiting for his heart to calm down and stop bruising his rib cage from the inside out.

#trauma cw#ptsd cw#tymptir#「ᵖᵃʳᶜʰᵐᵉᶰᵗˢ」ᵈᵃʳᵏ ʷᶤᶰᵍˢ; ᵈᵃʳᵏ ʷᵒʳᵈˢ#ᵛᵉʳˢᵉ ✻ ᵗʰᵉ ʷᶤᶰᵈˢ ᵒᶠ ʷᶤᶰᵗᵉʳ#...in my defense i did not intend for this to turn out so sad#my good boy#when will the world give him a break and let him nap

1 note

·

View note

Text

Othor Art

Othorian literature have long been orally traded and typically consist of alliterative verses. They include the proverbs, epics around the lives of old kings, and the Second Disaster. Chronicles of them are written down, containing long alliterative passages. They heavily focus on light comedies and skits, when it comes to original fiction.

Othorian sculptures are made of stone, metals, and/or jewels. Facial features of humanoid sculptures are characterized by high foreheads, thin, arching eyebrows, high-bridged noses, and small, fleshy lips, with exquisite jewelry, and known to have a peaceful and contemplative looks. The sculptures of Othor are generally made in two pieces: the body and the pedestal are made separately and then soldered together, though smaller sculptures are made in one piece. Most of the sculptures are gilded beautifully. They nearly only make humanoid figures.

Music is an integral part of Othorian culture. It is characterized by it's long songs, overtone singing, and horse-headed fiddles. The "long song" is called such because each syllable of text is extended for a long duration. A four-minute song may only consist of ten words, and lyrical themes vary depending on context. They can be philosophical, religious, romance, or celebratory, often using horses as a symbol or theme repeated throughout the song. It is often coupled with overtone singing, involving the production of two distinctively audible pitches at the same time, including a low pedal note (or drone) derived from the fundamental frequency of the vocal cord vibrations, and higher melodic notes that result when the singer's mouth acts as a filter, selecting one note at a time from among the drone's natural overtone series pitches.

Paintings are rare in Othor and usually depicting religious scenes or scenes for epics, if not the bright patterns of furniture. They are usually very bright in colours.

Another favored art of Othor is kalaga, a heavily embroidered appliqué tapestry made of silk, flannel, felt, wool and lace against a background made of cotton or velvet indigenous. This is called gold thread embroidery by Othorians. In a typical tapestry, padded figures are cut from various types of cloth and sewn onto a background, usually red or black cloth to form an elaborate scene, traditionally from classical epics. The figures are sewn using a combination of metallic and plain threads, and adorned with jewels.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jon

Sam?" Jon called softly.

The air smelled of paper and dust and years. Before him, tall wooden shelves rose up into dimness, crammed with leatherbound books and bins of ancient scrolls. A faint yellow glow filtered through the stacks from some hidden lamp. Jon blew out the taper he carried, preferring not to risk an open flame amidst so much old dry paper. Instead he followed the light, wending his way down the narrow aisles beneath barrel-vaulted ceilings. All in black, he was a shadow among shadows, dark of hair, long of face, grey of eye. Black moleskin gloves covered his hands; the right because it was burned, the left because a man felt half a fool wearing only one glove.

Samwell Tarly sat hunched over a table in a niche carved into the stone of the wall. The glow came from the lamp hung over his head. He looked up at the sound of Jon's steps.

"Have you been here all night?"

"Have I?" Sam looked startled.

"You didn't break your fast with us, and your bed hadn't been slept in." Rast suggested that maybe Sam had deserted, but Jon never believed it. Desertion required its own sort of courage, and Sam had little enough of that.

"Is it morning? Down here there's no way to know."

"Sam, you're a sweet fool," Jon said. "You'll miss that bed when we're sleeping on the cold hard ground, I promise you."

Sam yawned. "Maester Aemon sent me to find maps for the Lord Commander. I never thought . . . Jon, the books, have you ever seen their like? There are thousands!"

He gazed about him. "The library at Winterfell has more than a hundred. Did you find the maps?"

"Oh, yes." Sam's hand swept over the table, fingers plump as sausages indicating the clutter of books and scrolls before him. "A dozen, at the least." He unfolded a square of parchment. "The paint has faded, but you can see where the mapmaker marked the sites of wildling villages, and there's another book . . . where is it now? I was reading it a moment ago." He shoved some scrolls aside to reveal a dusty volume bound in rotted leather. "This," he said reverently, "is the account of a journey from the Shadow Tower all the way to Lorn Point on the Frozen Shore, written by a ranger named Redwyn. It's not dated, but he mentions a Dorren Stark as King in the North, so it must be from before the Conquest. Jon, they fought giants! Redwyn even traded with the children of the forest, it's all here." Ever so delicately, he turned pages with a finger. "He drew maps as well, see . . . "

"Maybe you could write an account of our ranging, Sam."

He'd meant to sound encouraging, but it was the wrong thing to say. The last thing Sam needed was to be reminded of what faced them on the morrow. He shuffled the scrolls about aimlessly. "There's more maps. If I had time to search . . . everything's a jumble. I could set it all to order, though; I know I could, but it would take time . . . well, years, in truth."

"Mormont wanted those maps a little sooner than that." Jon plucked a scroll from a bin, blew off the worst of the dust. A corner flaked off between his fingers as he unrolled it. "Look, this one is crumbling," he said, frowning over the faded script.

"Be gentle." Sam came around the table and took the scroll from his hand, holding it as if it were a wounded animal. "The important books used to be copied over when they needed them. Some of the oldest have been copied half a hundred times, probably."

"Well, don't bother copying that one. Twenty-three barrels of pickled cod, eighteen jars of fish oil, a cask of salt . . . "

"An inventory," Sam said, "or perhaps a bill of sale."

"Who cares how much pickled cod they ate six hundred years ago?" Jon wondered.

"I would." Sam carefully replaced the scroll in the bin from which Jon had plucked it. "You can learn so much from ledgers like that, truly you can. it can tell you how many men were in the Night's Watch then, how they lived, what they ate . . . "

"They ate food," said Jon, "and they lived as we live."

"You'd be surprised. This vault is a treasure, Jon."

"If you say so." Jon was doubtful. Treasure meant gold, silver, and jewels, not dust, spiders, and rotting leather.

"I do," the fat boy blurted. He was older than Jon, a man grown by law, but it was hard to think of him as anything but a boy. "I found drawings of the faces in the trees, and a book about the tongue of the children of the forest . . . works that even the Citadel doesn't have, scrolls from old Valyria, counts of the seasons written by maesters dead a thousand years . . . "

"The books will still be here when we return."

"If we return . . . "

"The Old Bear is taking two hundred seasoned men, three-quarters of them rangers. Qhorin Halfhand will be bringing another hundred brothers from the Shadow Tower. You'll be as safe as if you were back in your lord father's castle at Horn Hill."

Samwell Tarly managed a sad little smile. "I was never very safe in my father's castle either."

The gods play cruel jests, Jon thought. Pyp and Toad, all a lather to be a part of the great ranging, were to remain at Castle Black. It was Samwell Tarly, the self-proclaimed coward, grossly fat, timid, and near as bad a rider as he was with a sword, who must face the haunted forest. The Old Bear was taking two cages of ravens, so they might send back word as they went. Maester Aemon was blind and far too frail to ride with them, so his steward must go in his place. "We need you for the ravens, Sam. And someone has to help me keep Grenn humble."

Sam's chins quivered. "You could care for the ravens, or Grenn could, or anyone," he said with a thin edge of desperation in his voice. "I could show you how. You know your letters too, you could write down Lord Mormont's messages as well as I."

"I'm the Old Bear's steward. I'll need to squire for him, tend his horse, set up his tent; I won't have time to watch over birds as well. Sam, you said the words. You're a brother of the Night's Watch now."

"A brother of the Night's Watch shouldn't be so scared."

"We're all scared. We'd be fools if we weren't." Too many rangers had been lost the past two years, even Benjen Stark, Jon's uncle. They had found two of his uncle's men in the wood, slain, but the corpses had risen in the chill of night. Jon's burnt fingers twitched as he remembered. He still saw the wight in his dreams, dead Othor with the burning blue eyes and the cold black hands, but that was the last thing Sam needed to be reminded of. "There's no shame in fear, my father told me, what matters is how we face it. Come, I'll help you gather up the maps."

Sam nodded unhappily. The shelves were so closely spaced that they had to walk single file as they left. The vault opened onto one of the tunnels the brothers called the wormwalks, winding subterranean passages that linked the keeps and towers of Castle Black under the earth. In summer the wormwalks were seldom used, save by rats and other vermin, but winter was a different matter. When the snows drifted forty and fifty feet high and the ice winds came howling out of the north, the tunnels were all that held Castle Black together.

Soon, Jon thought as they climbed. He'd seen the harbinger that had come to Maester Aemon with word of summer's end, the great raven of the Citadel, white and silent as Ghost. He had seen a winter once, when he was very young, but everyone agreed that it had been a short one, and mild. This one would be different. He could feel it in his bones.

The steep stone steps had Sam puffing like a blacksmith's bellows by the time they reached the surface. They emerged into a brisk wind that made Jon's cloak swirl and snap. Ghost was stretched out asleep beneath the wattle-and-daub wall of the granary, but he woke when Jon appeared, bushy white tail held stiffly upright as he trotted to them.

Sam squinted up at the Wall. It loomed above them, an icy cliff seven hundred feet high. Sometimes it seemed to Jon almost a living thing, with moods of its own. The color of the ice was wont to change with every shift of the light. Now it was the deep blue of frozen rivers, now the dirty white of old snow, and when a cloud passed before the sun it darkened to the pale grey of pitted stone. The Wall stretched east and west as far as the eye could see, so huge that it shrunk the timbered keeps and stone towers of the castle to insignificance. It was the end of the world.

And we are going beyond it.

The morning sky was streaked by thin grey clouds, but the pale red line was there behind them. The black brothers had dubbed the wanderer Mormont's Torch, saying (only half in jest) that the gods must have sent it to light the old man's way through the haunted forest.

"The comet's so bright you can see it by day now," Sam said, shading his eyes with a fistful of books.

"Never mind about comets, it's maps the Old Bear wants."

Ghost loped ahead of them. The grounds seemed deserted this morning, with so many rangers off at the brothel in Mole's Town, digging for buried treasure and drinking themselves blind. Grenn had gone with them. Pyp and Halder and Toad had offered to buy him his first woman to celebrate his first ranging. They'd wanted Jon and Sam to come as well, but Sam was almost as frightened of whores as he was of the haunted forest, and Jon had wanted no part of it. "Do what you want," he told Toad, "I took a vow."

As they passed the sept, he heard voices raised in song. Some men want whores on the eve of battle, and some want gods. Jon wondered who felt better afterward. The sept tempted him no more than the brothel; his own gods kept their temples in the wild places, where the weirwoods spread their bone-white branches. The Seven have no power beyond the Wall, he thought, but my gods will be waiting.

Outside the armory, Ser Endrew Tarth was working with some raw recruits. They'd come in last night with Conwy, one of the wandering crows who roamed the Seven Kingdoms collecting men for the Wall. This new crop consisted of a greybeard leaning on a staff, two blond boys with the look of brothers, a foppish youth in soiled satin, a raggy man with a clubfoot, and some grinning loon who must have fancied himself a warrior. Ser Endrew was showing him the error of that presumption. He was a gentler master-at-arms than Ser Alliser Thorne had been, but his lessons would still raise bruises. Sam winced at every blow, but Jon Snow watched the swordplay closely.

"What do you make of them, Snow?" Donal Noye stood in the door of his armory, bare-chested under a leather apron, the stump of his left arm uncovered for once. With his big gut and barrel chest, his flat nose and bristly black jaw, Noyc did not make a pretty sight, but he was a welcome one nonetheless. The armorer had proved himself a good friend.

"They smell of summer," Jon said as Ser Endrew bullrushed his foe and knocked him sprawling. "Where did Conwy find them?"

"A lord's dungeon near Gulltown," the smith replied. "A brigand, a barber, a beggar, two orphans, and a boy whore. With such do we defend the realms of men."

"They'll do." Jon gave Sam a private smile. "We did."

Noye drew him closer. "You've heard these tidings of your brother?"

"Last night." Conwy and his charges had brought the news north with them, and the talk in the common room had been of little else. Jon was still not certain how he felt about it. Robb a king? The brother he'd played with, fought with, shared his first cup of wine with? But not mother's milk, no. So now Robb will sip summerwine from jeweled goblets, while I'm kneeling beside some stream sucking snowmelt from cupped hands. "Robb will make a good king," he said loyally.

"Will he now?" The smith eyed him frankly. "I hope that's so, boy, but once I might have said the same of Robert."

"They say you forged his warhammer," Jon remembered.

"Aye. I was his man, a Baratheon man, smith and armorer at Storm's End until I lost the arm. I'm old enough to remember Lord Steffon before the sea took him, and I knew those three sons of his since they got their names. I tell you this—Robert was never the same after he put on that crown. Some men are like swords, made for fighting. Hang them up and they go to rust."

"And his brothers?" Jon asked.

The armorer considered that a moment. "Robert was the true steel. Stannis is pure iron, black and hard and strong, yes, but brittle, the way iron gets. He'll break before he bends. And Renly, that one, he's copper, bright and shiny, pretty to look at but not worth all that much at the end of the day."

And what metal is Robb? Jon did not ask. Noye was a Baratheon man; likely he thought Joffrey the lawful king and Robb a traitor. Among the brotherhood of the Night's Watch, there was an unspoken pact never to probe too deeply into such matters. Men came to the Wall from all of the Seven Kingdoms, and old loves and loyalties were not easily forgotten, no matter how many oaths a man swore . . . as Jon himself had good reason to know. Even Sam—his father's House was sworn to Highgarden, whose Lord Tyrell supported King Renly. Best not to talk of such things. The Night's Watch took no sides. "Lord Mormont awaits us," Jon said.

"I won't keep you from the Old Bear." Noye clapped him on the shoulder and smiled. "May the gods go with you on the morrow, Snow. You bring back that uncle of yours, you hear?"

"We will," Jon promised him.

Lord Commander Mormont had taken up residence in the King's Tower after the fire had gutted his own. Jon left Ghost with the guards outside the door. "More stairs," said Sam miserably as they started up. "I hate stairs."

"Well, that's one thing we won't face in the wood."

When they entered the solar, the raven spied them at once. "Snow!" the bird shrieked. Mormont broke off his conversation. "Took you long enough with those maps." He pushed the remains of breakfast out of the way to make room on the table. "Put them here. I'll have a look at them later."

Thoren Smallwood, a sinewy ranger with a weak chin and a weaker mouth hidden under a thin scraggle of beard, gave Jon and Sam a cool look. He had been one of Alliser Thorne's henchmen, and had no love for either of them. "The Lord Commander's place is at Castle Black, lording and commanding," he told Mormont, ignoring the newcomers, "it seems to me."

The raven flapped big black wings. "Me, me, me."

"If you are ever Lord Commander, you may do as you please," Mormont told the ranger, "but it seems to me that I have not died yet, nor have the brothers put you in my place."

"I'm First Ranger now, with Ben Stark lost and Ser Jaremy killed," Smallwood said stubbornly. "The command should be mine."

Mormont would have none of it. "I sent out Ben Stark, and Ser Waymar before him. I do not mean to send you after them and sit wondering how long I must wait before I give you up for lost as well." He pointed. "And Stark remains First Ranger until we know for a certainty that he is dead. Should that day come, it will be me who names his successor, not you. Now stop wasting my time. We ride at first light, or have you forgotten?"

Smallwood pushed to his feet. "As my lord commands." On the way out, he frowned at Jon, as if it were somehow his fault.

"First Ranger!" The Old Bear's eyes lighted on Sam. "I'd sooner name you First Ranger. He has the effrontery to tell me to my face that I'm too old to ride with him. Do I look old to you, boy?" The hair that had retreated from Mormont's spotted scalp had regrouped beneath his chin in a shaggy grey beard that covered much of his chest. He thumped it hard. "Do I look frail?"

Sam opened his mouth, gave a little squeak. The Old Bear terrified him. "No, my lord," Jon offered quickly. "You look strong as a . . . a . . . "

"Don't cozen me, Snow, you know I won't have it. Let me have a look at these maps." Mormont pawed through them brusquely, giving each no more than a glance and a grunt. "Was this all you could find?"

"I . . . m-m-my lord," Sam stammered, "there . . . there were more, b-b-but . . . the dis-disorder . . . "

"These are old," Mormont complained, and his raven echoed him with a sharp cry of "Old, old."

"The villages may come and go, but the hills and rivers will be in the same places," Jon pointed out.

"True enough. Have you chosen your ravens yet, Tarly?"

"M-m-maester Aemon m-means to p-pick them come evenfall, after the f-f-feeding."

"I'll have his best. Smart birds, and strong."

"Strong," his own bird said, preening. "Strong, strong."

"If it happens that we're all butchered out there, I mean for my successor to know where and how we died."

Talk of butchery reduced Samwell Tarly to speechlessness. Mormont leaned forward. "Tarly, when I was a lad half your age, my lady mother told me that if I stood about with my mouth open, a weasel was like to mistake it for his lair and run down my throat. If you have something to say, say it. Otherwise, beware of weasels." He waved a brusque dismissal. "Off with you, I'm too busy for folly. No doubt the maester has some work you can do."

Sam swallowed, stepped back, and scurried out so quickly he almost tripped over the rushes.

"Is that boy as big a fool as he seems?" the Lord Commander asked when he'd gone. "Fool," the raven complained. Mormont did not wait for Jon to answer. "His lord father stands high in King Renly's councils, and I had half a notion to dispatch him . . . no, best not. Renly is not like to heed a quaking fat boy. I'll send Ser Arnell. He's a deal steadier, and his mother was one of the green-apple Fossoways."

"If it please my lord, what would you have of King Renly?"

"The same things I'd have of all of them, lad. Men, horses, swords, armor, grain, cheese, wine, wool, nails . . . the Night's Watch is not proud, we take what is offered." His fingers drummed against the roughhewn planks of the table. "If the winds have been kind, Ser Alliser should reach King's Landing by the turn of the moon, but whether this boy Joffrey will pay him any heed, I do not know. House Lannister has never been a friend to the Watch."

"Thorne has the wight's hand to show them." A grisly pale thing with black fingers, it was, that twitched and stirred in its jar as if it were still alive.

"Would that we had another hand to send to Renly."

"Dywen says you can find anything beyond the Wall."

"Aye, Dywen says. And the last time he went ranging, he says he saw a bear fifteen feet tall." Mormont snorted. "My sister is said to have taken a bear for her lover. I'd believe that before I'd believe one fifteen feet tall. Though in a world where dead come walking . . . ah, even so, a man must believe his eyes. I have seen the dead walk. I've not seen any giant bears." He gave Jon a long, searching look. "But we were speaking of hands. How is yours?"

"Better." Jon peeled off his moleskin glove and showed him. Scars covered his arm halfway to the elbow, and the mottled pink flesh still felt tight and tender, but it was healing. "It itches, though. Maester Aemon says that's good. He gave me a salve to take with me when we ride."

"You can wield Longclaw despite the pain?"

"Well enough." Jon flexed his fingers, opening and closing his fist the way the maester had shown him. "I'm to work the fingers every day to keep them nimble, as Maester Aemon said."

"Blind he may be, but Aemon knows what he's about. I pray the gods let us keep him another twenty years. Do you know that he might have been king?"

Jon was taken by surprise. "He told me his father was king, but not . . . I thought him perhaps a younger son."

"So he was. His father's father was Daeron Targaryen, the Second of His Name, who brought Dorne into the realm. Part of the pact was that he wed a Dornish princess. She gave him four sons. Aemon's father Maekar was the youngest of those, and Aemon was his third son. Mind you, all this happened long before I was born, ancient as Smallwood would make me."

"Maester Aemon was named for the Dragonknight."

"So he was. Some say Prince Aemon was King Daeron's true father, not Aegon the Unworthy. Be that as it may, our Aemon lacked the Dragonknight's martial nature. He likes to say he had a slow sword but quick wits. Small wonder his grandfather packed him off to the Citadel. He was nine or ten, I believe . . . and ninth or tenth in the line of succession as well."

Maester Aemon had counted more than a hundred name days, Jon knew. Frail, shrunken, wizened, and blind, it was hard to imagine him as a little boy no older than Arya.

Mormont continued. "Aemon was at his books when the eldest of his uncles, the heir apparent, was slain in a tourney mishap. He left two sons, but they followed him to the grave not long after, during the Great Spring Sickness. King Daeron was also taken, so the crown passed to Daeron's second son, Aerys."

"The Mad King?" Jon was confused. Aerys had been king before Robert, that wasn't so long ago.

"No, this was Aerys the First. The one Robert deposed was the second of that name."

"How long ago was this?"

"Eighty years or close enough," the Old Bear said, "and no, I still hadn't been born, though Aemon had forged half a dozen links of his maester's chain by then. Aerys wed his own sister, as the Targaryens were wont to do, and reigned for ten or twelve years. Aemon took his vows and left the Citadel to serve at some lordling's court . . . until his royal uncle died without issue. The Iron Throne passed to the last of King Daeron's four sons. That was Maekar, Aemon's father. The new king summoned all his sons to court and would have made Aemon part of his councils, but he refused, saying that would usurp the place rightly belonging to the Grand Maester. Instead he served at the keep of his eldest brother, another Daeron. Well, that one died too, leaving only a feeble-witted daughter as heir. Some pox he caught from a whore, I believe. The next brother was Aerion."

"Aerion the Monstrous?" Jon knew that name. "The Prince Who Thought He Was a Dragon" was one of Old Nan's more gruesome tales. His little brother Bran had loved it.

"The very one, though he named himself Aerion Brightflame. One night, in his cups, he drank a jar of wildfire, after telling his friends it would transform him into a dragon, but the gods were kind and it transformed him into a corpse. Not quite a year after, King Maekar died in battle against an outlaw lord."

Jon was not entirely innocent of the history of the realm; his own maester had seen to that. "That was the year of the Great Council," he said. "The lords passed over Prince Aerion's infant son and Prince Daeron's daughter and gave the crown to Aegon."

"Yes and no. First they offered it, quietly, to Aemon. And quietly he refused. The gods meant for him to serve, not to rule, he told them. He had sworn a vow and would not break it, though the High Septon himself offered to absolve him. Well, no sane man wanted any blood of Aerion's on the throne, and Daeron's girl was a lackwit besides being female, so they had no choice but to turn to Aemon's younger brother—Aegon, the Fifth of His Name. Aegon the Unlikely, they called him, born the fourth son of a fourth son. Aemon knew, and rightly, that if he remained at court those who disliked his brother's rule would seek to use him, so he came to the Wall. And here he has remained, while his brother and his brother's son and his son each reigned and died in turn, until Jaime Lannister put an end to the line of the Dragonkings."

"King," croaked the raven. The bird flapped across the solar to land on Mormont's shoulder. "King," it said again, strutting back and forth.

"He likes that word," Jon said, smiling.

"An easy word to say. An easy word to like."

"King," the bird said again.

"I think he means for you to have a crown, my lord."

"The realm has three kings already, and that's two too many for my liking." Mormont stroked the raven under the beak with a finger, but all the while his eyes never left Jon Snow.

It made him feel odd. "My lord, why have you told me this, about Maester Aemon?"

"Must I have a reason?" Mormont shifted in his seat, frowning. "Your brother Robb has been crowned King in the North. You and Aemon have that in common. A king for a brother."

"And this too," said Jon. "A vow."

The Old Bear gave a loud snort, and the raven took flight, flapping in a circle about the room, "Give me a man for every vow I've seen broken and the Wall will never lack for defenders."

"I've always known that Robb would be Lord of Winterfell."

Mormont gave a whistle, and the bird flew to him again and settled on his arm. "A lord's one thing, a king's another." He offered the raven a handful of corn from his pocket. "They will garb your brother Robb in silks, satins, and velvets of a hundred different colors, while you live and die in black ringmail. He will wed some beautiful princess and father sons on her. You'll have no wife, nor will you ever hold a child of your own blood in your arms. Robb will rule, you will serve. Men will call you a crow. Him they'll call Your Grace. Singers will praise every little thing he does, while your greatest deeds all go unsung. Tell me that none of this troubles you, Jon . . . and I'll name you a liar, and know I have the truth of it."

Jon drew himself up, taut as a bowstring. "And if it did trouble me, what might I do, bastard as I am?"

"What will you do?" Mormont asked. "Bastard as you are?"

"Be troubled," said Jon, "and keep my vows."

0 notes

Text

no but like the similarities between the scene of jon fighting the othor wight and the scene of tyrion fighting the stone man

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Othor Superstition

Othorian people take superstitions very seriously, and they share theirs freely to warn against doing them.

It is bad luck to kiss on the threshold between rooms.

You shouldn't drink cold drinks if you are not feeling well, it will make you more sick.

Don't write anyone's name in red, as it signifies bad luck.

If you see a wild batwolf, you'll get three years of good luck.

If you step or bump someone's foot/shoe with your own, you must shake hands to undo the bad feeling created.

Do not step on the threshold between rooms as it is like stepping on the owner's neck.

The most endangered by spirits are children, who are given non-names to protect them, and before going out their foreheads are painted with charcoal or soot to deceive spirits that this is not a child but a batrabbit with black hair on the forehead

Many different omens of good or evil fortune are drawn from objects; from the stone with which their houses are built, from their weapons and tools, from the aspects of the gems and metals, from the howling of batwolves, and the singing of bugs, from the involuntary movements of the members of one's own body...

1 note

·

View note

Text

Othor Architecture and Furniture

The architecture of Othor is largely built to be compact and easy to defend, with large and impressive buildings being reserved for public buildings, leaving two distinct types of architecture.

As such homes are often very robust buildings made from solid stone, carved directly out of the mountain, and usually stacked upon each other along the cave walls with stairs leading from roof to roof, all easily visible from windows in several directions at all times. Round shapes are common for these buildings, and the roofs are intentionally made so that people unused to walking on them will get bad footing. Houses usually have one big round room serving as kitchen and living room you enter into if entering a home, and stairs into the mountain - either down or down and in, where sleeping quarters and the armory are located.

In contrast, official buildings are placed in center stage, and they, as well as mine entrances, are more obviously inspired by other Atian architecture. With one to four floors, a heavy emphasis on articulation and bilateral symmetry, secondary elements of buildings positioned on either side of a main building to maintain the symmetry. To represent gardens they have asymmetrical gem gardens. Visual impact of the width of buildings is stressed, ceilings that are high for dwarves but low for other species are the norm. Buildings and building complexes normally take up an entire property. These buildings are built with prefab panels of stone or gemstones that are easy to rearrange, but there are taboos against rearranging a building. Doors are commonly screen walls made of gemstones or crystals, always facing the main entrance of the house.

Othorian furniture is generally made with simple shapes, due to often being mare out of iron, favoring simplistic decorative legs. The main decorative parts of their furniture, and even houses, are painting walls and furniture bright colours with complicated decorative patterns. Favors bright orange as a ground colour, with blue, green, red, pink, yellow, and black being common in the patterns.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Othor Food

The underground life of the Othorian people has affected the traditional diet, their cuisine primarily consists of bugs, mushrooms, and dairy products, meat, and animal fats from the cattle they have managed to get to thrive underground (sheep, cows, pigs, horses, yaks, and goats bred with bats and enormous insects). Use of vegetables and spices are very limited.

Meat is either cooked, used as an ingredient for soups and dumplings, or dried. Milk and cream are used to make a variety of beverages, as well as cheese and similar products. The most common dish is cooked batlamb, often without any other ingredients. Steamed dumplings filled with meat are also common, but other types of dumplings are boiled in water, or deep fried in batlamb fat. Other, more recent, dishes combine the meat with rice or fresh noodles made into various stews or noodle soups.

There is also a cooking method only used on special occasions, where the meat (often together with vegetables and mushrooms) gets cooked with the help of stones, which have been preheated in a fire. This either happens with chunks of batlamb in a sealed milk can, or within the abdominal cavity of a deboned batgoat.

The Othorian people are really fond of liquor, mostly made of mushrooms or underground berries, but a common light drink is a light milk liquor. Another national beverage is fermented batmare's milk. The everyday beverage is salted milk tea, which can be turned into a robust soup by adding rice, meat, or dumplings.

Sweets include a type of biscuit or cookie eaten on special occasions, and fried insects are commonly eaten as snacks.

0 notes

Text

Jon

Othor," announced Ser Jaremy Rykker, "beyond a doubt. And this one was Jafer Flowers." He turned the corpse over with his foot, and the dead white face stared up at the overcast sky with blue, blue eyes. "They were Ben Stark's men, both of them."

My uncle's men, Jon thought numbly. He remembered how he'd pleaded to ride with them. Gods, I was such a green boy. If he had taken me, it might be me lying here . . .

Jafer's right wrist ended in the ruin of torn flesh and splintered bone left by Ghost's jaws. His right hand was floating in a jar of vinegar back in Maester Aemon's tower. His left hand, still at the end of his arm, was as black as his cloak.

"Gods have mercy," the Old Bear muttered. He swung down from his garron, handing his reins to Jon. The morning was unnaturally warm; beads of sweat dotted the Lord Commander's broad forehead like dew on a melon. His horse was nervous, rolling her eyes, backing away from the dead men as far as her lead would allow. Jon led her off a few paces, fighting to keep her from bolting. The horses did not like the feel of this place. For that matter, neither did Jon.

The dogs liked it least of all. Ghost had led the party here; the pack of hounds had been useless. When Bass the kennelmaster had tried to get them to take the scent from the severed hand, they had gone wild, yowling and barking, fighting to get away. Even now they were snarling and whimpering by turns, pulling at their leashes while Chett cursed them for curs.

It is only a wood, Jon told himself, and they're only dead men. He had seen dead men before . . .

Last night he had dreamt the Winterfell dream again. He was wandering the empty castle, searching for his father, descending into the crypts. Only this time the dream had gone further than before. In the dark he'd heard the scrape of stone on stone. When he turned he saw that the vaults were opening, one after the other. As the dead kings came stumbling from their cold black graves, Jon had woken in pitch-dark, his heart hammering. Even when Ghost leapt up on the bed to nuzzle at his face, he could not shake his deep sense of terror. He dared not go back to sleep. Instead he had climbed the Wall and walked, restless, until he saw the light of the dawn off to the cast. It was only a dream. I am a brother of the Night's Watch now, not a frightened boy.

Samwell Tarly huddled beneath the trees, half-hidden behind the horses. His round fat face was the color of curdled milk. So far he had not lurched off to the woods to retch, but he had not so much as glanced at the dead men either. "I can't look," he whispered miserably.

"You have to look," Jon told him, keeping his voice low so the others would not hear. "Maester Aemon sent you to be his eyes, didn't he? What good are eyes if they're shut?"

"Yes, but . . . I'm such a coward, Jon."

Jon put a hand on Sam's shoulder. "We have a dozen rangers with us, and the dogs, even Ghost. No one will hurt you, Sam. Go ahead and look. The first look is the hardest."

Sam gave a tremulous nod, working up his courage with a visible effort. Slowly he swiveled his head. His eyes widened, but Jon held his arm so he could not turn away.

"Ser Jaremy," the Old Bear asked gruffly, "Ben Stark had six men with him when he rode from the Wall. Where are the others?"

Ser Jaremy shook his head. "Would that I knew."

Plainly Mormont was not pleased with that answer. "Two of our brothers butchered almost within sight of the Wall, yet your rangers heard nothing, saw nothing. Is this what the Night's Watch has fallen to? Do we still sweep these woods?"

"Yes, my lord, but—"

"Do we still mount watches?"

"We do, but—"

"This man wears a hunting horn." Mormont pointed at Othor. "Must I suppose that he died without sounding it? Or have your rangers all gone deaf as well as blind?"

Ser Jaremy bristled, his face taut with anger. "No horn was blown, my lord, or my rangers would have heard it. I do not have sufficient men to mount as many patrols as I should like . . . and since Benjen was lost, we have stayed closer to the Wall than we were wont to do before, by your own command."

The Old Bear grunted. "Yes. Well. Be that as it may." He made an impatient gesture. "Tell me how they died."

Squatting beside the dead man he had named Jafer Flowers, Ser Jaremy grasped his head by the scalp. The hair came out between his fingers, brittle as straw. The knight cursed and shoved at the face with the heel of his hand. A great gash in the side of the corpse's neck opened like a mouth, crusted with dried blood. Only a few ropes of pale tendon still attached the head to the neck. "This was done with an axe."

"Aye," muttered Dywen, the old forester. "Belike the axe that Othor carried, m'lord."

Jon could feel his breakfast churning in his belly, but he pressed his lips together and made himself look at the second body. Othor had been a big ugly man, and he made a big ugly corpse. No axe was in evidence. Jon remembered Othor; he had been the one bellowing the bawdy song as the rangers rode out. His singing days were done. His flesh was blanched white as milk, everywhere but his hands. His hands were black like Jafer's. Blossoms of hard cracked blood decorated the mortal wounds that covered him like a rash, breast and groin and throat. Yet his eyes were still open. They stared up at the sky, blue as sapphires.

Ser Jaremy stood. "The wildlings have axes too."

Mormont rounded on him. "So you believe this is Mance Rayder's work? This close to the Wall?"

"Who else, my lord?"

Jon could have told him. He knew, they all knew, yet no man of them would say the words. The Others are only a story, a tale to make children shiver. If they ever lived at all, they are gone eight thousand years. Even the thought made him feel foolish; he was a man grown now, a black brother of the Night's Watch, not the boy who'd once sat at Old Nan's feet with Bran and Robb and Arya.

Yet Lord Commander Mormont gave a snort. "If Ben Stark had come under wildling attack a half day's ride from Castle Black, he would have returned for more men, chased the killers through all seven hells and brought me back their heads."

"Unless he was slain as well," Ser Jaremy insisted.

The words hurt, even now. It had been so long, it seemed folly to cling to the hope that Ben Stark was still alive, but Jon Snow was nothing if not stubborn.

"It has been close on half a year since Benjen left us, my lord," Ser Jaremy went on. "The forest is vast. The wildlings might have fallen on him anywhere. I'd wager these two were the last survivors of his party, on their way back to us . . . but the enemy caught them before they could reach the safety of the Wall. The corpses are still fresh, these men cannot have been dead more than a day . . . ."

"No," Samwell Tarly squeaked.

Jon was startled. Sam's nervous, high-pitched voice was the last he would have expected to hear. The fat boy was frightened of the officers, and Ser Jaremy was not known for his patience.

"I did not ask for your views, boy," Rykker said coldly.

"Let him speak, ser," Jon blurted.

Mormont's eyes flicked from Sam to Jon and back again. "If the lad has something to say, I'll hear him out. Come closer, boy. We can't see you behind those horses."

Sam edged past Jon and the garrons, sweating profusely. "My lord, it . . . it can't be a day or . . . look . . . the blood . . . "

"Yes?" Mormont growled impatiently. "Blood, what of it?"

"He soils his smallclothes at the sight of it," Chett shouted out, and the rangers laughed.

Sam mopped at the sweat on his brow. "You . . . you can see where Ghost . . . Jon's direwolf . . . you can see where he tore off that man's hand, and yet . . . the stump hasn't bled, look . . . " He waved a hand. "My father . . . L-lord Randyll, he, he made me watch him dress animals sometimes, when . . . after . . . " Sam shook his head from side to side, his chins quivering. Now that he had looked at the bodies, he could not seem to look away. "A fresh kill . . . the blood would still flow, my lords. Later . . . later it would be clotted, like a . . . a jelly, thick and . . . and . . . " He looked as though he was going to be sick. "This man . . . look at the wrist, it's all . . . crusty . . . dry . . . like . . . "

Jon saw at once what Sam meant. He could see the torn veins in the dead man's wrist, iron worms in the pale flesh. His blood was a black dust. Yet Jaremy Rykker was unconvinced. "If they'd been dead much longer than a day, they'd be ripe by now, boy. They don't even smell."

Dywen, the gnarled old forester who liked to boast that he could smell snow coming on, sidled closer to the corpses and took a whiff. "Well, they're no pansy flowers, but . . . m'lord has the truth of it. There's no corpse stink."

"They . . . they aren't rotting." Sam pointed, his fat finger shaking only a little. "Look, there's . . . there's no maggots or . . . or . . . worms or anything . . . they've been lying here in the woods, but they . . . they haven't been chewed or eaten by animals . . . only Ghost . . . otherwise they're . . . they're . . . "

"Untouched," Jon said softly. "And Ghost is different. The dogs and the horses won't go near them."

The rangers exchanged glances; they could see it was true, every man of them. Mormont frowned, glancing from the corpses to the dogs. "Chett, bring the hounds closer."

Chett tried, cursing, yanking on the leashes, giving one animal a lick of his boot. Most of the dogs just whimpered and planted their feet. He tried dragging one. The bitch resisted, growling and squirming as if to escape her collar. Finally she lunged at him. Chett dropped the leash and stumbled backward. The dog leapt over him and bounded off into the trees.

"This . . . this is all wrong," Sam Tarly said earnestly. "The blood . . . there's bloodstains on their clothes, and . . . and their flesh, dry and hard, but . . . there's none on the ground, or . . . anywhere. With those . . . those . . . those . . . " Sam made himself swallow, took a deep breath. "With those wounds . . . terrible wounds . . . there should be blood all over. Shouldn't there?"

Dywen sucked at his wooden teeth. "Might be they didn't die here. Might be someone brought 'em and left 'em for us. A warning, as like." The old forester peered down suspiciously. "And might be I'm a fool, but I don't know that Othor never had no blue eyes afore."

Ser Jaremy looked startled. "Neither did Flowers," he blurted, turning to stare at the dead man.

A silence fell over the wood. For a moment all they heard was Sam's heavy breathing and the wet sound of Dywen sucking on his teeth. Jon squatted beside Ghost.

"Burn them," someone whispered. One of the rangers; Jon could not have said who. "Yes, burn them," a second voice urged.

The Old Bear gave a stubborn shake of his head. "Not yet. I want Maester Aemon to have a look at them. We'll bring them back to the Wall."

Some commands are more easily given than obeyed. They wrapped the dead men in cloaks, but when Hake and Dywen tried to tie one onto a horse, the animal went mad, screaming and rearing, lashing out with its hooves, even biting at Ketter when he ran to help. The rangers had no better luck with the other garrons; not even the most placid wanted any part of these burdens. In the end they were forced to hack off branches and fashion crude slings to carry the corpses back on foot. It was well past midday by the time they started back.

"I will have these woods searched," Mormont commanded Ser Jaremy as they set out. "Every tree, every rock, every bush, and every foot of muddy ground within ten leagues of here. Use all the men you have, and if you do not have enough, borrow hunters and foresters from the stewards. If Ben and the others are out here, dead or alive, I will have them found. And if there is anyone else in these woods, I will know of it. You are to track them and take them, alive if possible. Is that understood?"

"It is, my lord," Ser Jaremy said. "It will be done."

After that, Mormont rode in silence, brooding. Jon followed close behind him; as the Lord Commander's steward, that was his place. The day was grey, damp, overcast, the sort of day that made you wish for rain. No wind stirred the wood; the air hung humid and heavy, and Jon's clothes clung to his skin. It was warm. Too warm. The Wall was weeping copiously, had been weeping for days, and sometimes Jon even imagined it was shrinking.

The old men called this weather spirit summer, and said it meant the season was giving up its ghosts at last. After this the cold would come, they warned, and a long summer always meant a long winter. This summer had lasted ten years. Jon had been a babe in arms when it began.

Ghost ran with them for a time and then vanished among the trees. Without the direwolf, Jon felt almost naked. He found himself glancing at every shadow with unease. Unbidden, he thought back on the tales that Old Nan used to tell them, when he was a boy at Winterfell. He could almost hear her voice again, and the click-click-click of her needles. In that darkness, the Others came riding, she used to say, dropping her voice lower and lower. Cold and dead they were, and they hated iron and fire and the touch of the sun, and every living creature with hot blood in its veins. Holdfasts and cities and kingdoms of men all fell before them, as they moved south on pale dead horses, leading hosts of the slain. They fed their dead servants on the flesh of human children . . .

When he caught his first glimpse of the Wall looming above the tops of an ancient gnarled oak, Jon was vastly relieved. Mormont reined up suddenly and turned in his saddle. "Tarly," he barked, "come here."

Jon saw the start of fright on Sam's face as he lumbered up on his mare; doubtless he thought he was in trouble. "You're fat but you're not stupid, boy," the Old Bear said gruffly. "You did well back there. And you, Snow."

Sam blushed a vivid crimson and tripped over his own tongue as he tried to stammer out a courtesy. Jon had to smile.

When they emerged from under the trees, Mormont spurred his tough little garron to a trot. Ghost came streaking out from the woods to meet them, licking his chops, his muzzle red from prey. High above, the men on the Wall saw the column approaching. Jon heard the deep, throaty call of the watchman's great horn, calling out across the miles; a single long blast that shuddered through the trees and echoed off the ice.

UUUUUUUOOOOOOOOOOOOOOooooooooooooooooooooooo.

The sound faded slowly to silence. One blast meant rangers returning, and Jon thought, I was a ranger for one day, at least. Whatever may come, they cannot take that away from me.

Bowen Marsh was waiting at the first gate as they led their garrons through the icy tunnel. The Lord Steward was red-faced and agitated. "My lord," he blurted at Mormont as he swung open the iron bars, "there's been a bird, you must come at once."

"What is it, man?" Mormont said gruffly.

Curiously, Marsh glanced at Jon before he answered. "Maester Aemon has the letter. He's waiting in your solar."

"Very well. Jon, see to my horse, and tell Ser Jaremy to put the dead men in a storeroom until the maester is ready for them." Mormont strode away grumbling.

As they led their horses back to the stable, Jon was uncomfortably aware that people were watching him. Ser Alliser Thorne was drilling his boys in the yard, but he broke off to stare at Jon, a faint half smile on his lips. One-armed Donal Noye stood in the door of the armory. "The gods be with you, Snow," he called out.

Something's wrong, Jon thought. Something's very wrong.

The dead men were carried to one of the storerooms along the base of the Wall, a dark cold cell chiseled from the ice and used to keep meat and grain and sometimes even beer. Jon saw that Mormont's horse was fed and watered and groomed before he took care of his own. Afterward he sought out his friends. Grenn and Toad were on watch, but he found Pyp in the common hall. "What's happened?" he asked.

Pyp lowered his voice. "The king's dead."