#Seminole Freedmen

Text

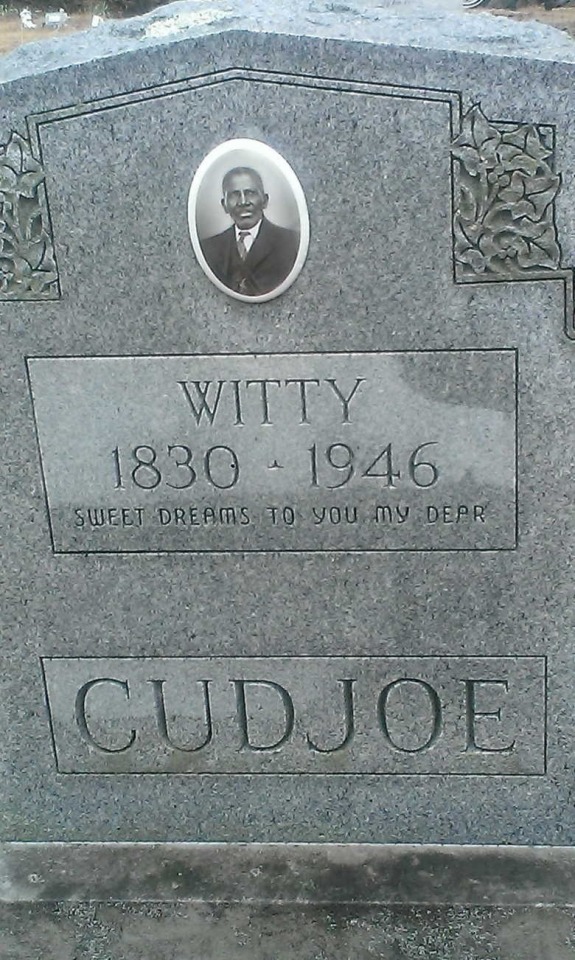

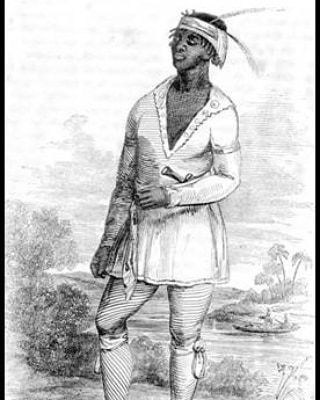

Witty Cudjoe

It's Black History Month in the United States, and I want to share the story of my 3rd Great Grandfather, Witty Cudjoe.

Born in 1830 during the Seminole Wars in Florida, Witty Cudjoe shared his memories in a newspaper article published when he turned 105. Witty's heritage is a legacy of warriors, tracing back to his grandfather, King Cudjo.

King's journey from slavery in the Carolinas to freedom in Spanish Florida in the 1700s marked the beginning of a lineage that shaped the Seminoles. Witty's father and grandfather fought alongside fellow Seminoles, facing Andrew Jackson and the United States Army.

Witty also discussed the removal to Indian Territory after a deceptive treaty with the United States. Despite being initially enslaved, Witty later fought as a Loyal Seminole, securing his freedom. He helped in the establishment of Wewoka, emerging as an important figure in his community.

During a time marked by the exploitation of Native Americans, Witty and his wife Mariah faced attempts to manipulate them out of their land allotments. Despite being unable to read or write, Witty took legal action and won, a remarkable feat at the time.

Witty's courage and determination defined his story, blessing future generations through the land he secured. Despite challenges posed by statehood, Witty leased 10 acres of his land to establish a school, preserving the Muscogee language and Seminole culture for his children. Witty lived to the age of 116, passing away in 1946.

During my last visit to Oklahoma, I met a 94-year-old cousin who had cared for Witty in his later years. Hugging her felt like reaching back through time, expressing gratitude to Witty for my existence.

Reflecting on our history, I see similarities with other communities, such as the Palestinians fighting for freedom. Like the Palestinians, they too faced forced displacement and theft of identity. Despite everything, our ancestors stood strong, and our community perseveres.

In solidarity with the Palestinian community, I commemorate Black History Month, acknowledging shared struggles. I hope that by standing together, we can illuminate the path home for all displaced people someday.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Battle of ‘Negro Fort’ – Inside America's Forgotten Slave Rebellion - MilitaryHistoryNow.com

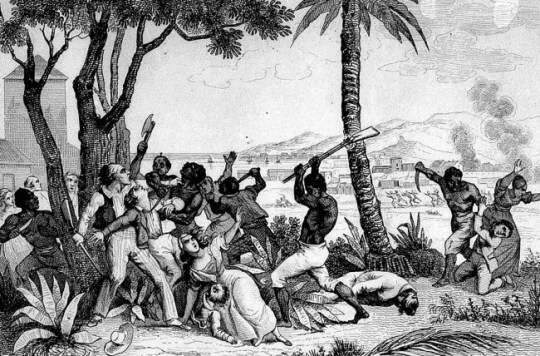

A year after the Battle of New Orleans, runaway slaves armed by the British occupied a stockade in Spanish Florida. The so called “Negro Fort” became a mecca for other fugitives from Southern plantations. In 1816, the U.S. Army arrived to crush the settlement. (Image source: WikiCommons)

“The Battle of the ‘Negro Fort,’ marks a critical moment when the federal government took a decisive stance in support of slavery and its expansion.”

By Matt Clavin

THE TIDAL MARSHES of Florida’s Apalachicola River were still under the authority of the Spanish crown in 1816, yet the events that took place there would go on to become a forgotten yet tragic chapter in the long and bloody history of American slavery.

It was during that year that an army of fugitive slaves, armed with foreign weaponry and united by dreams of freedom, would fight and die against a legion of American troops and allied Creek Indians dispatched by a future U.S. president bent on their destruction.

The Battle of the ‘Negro Fort’ marks a critical moment when the federal government took a decisive stance in support of slavery and its expansion.

What would become known as Negro Fort actually sprung from the War of 1812, one of the United States’ most misunderstood conflicts. During the contest’s third and final summer, Britain landed hundreds of troops on Florida’s Gulf Coast in preparation of an invasion of the southern United States.

Still Spanish territories at the time, East Florida and West Florida were neutral in the second war between the American Republic and the United Kingdom. Yet, the uncontested arrival of British troops there suggested the local authorities had ostensibly sided with the redcoats.

Americans’ fears of a Spanish-British alliances only increased when a detachment of Royal Marines erected a sizeable fort on the eastern shore of the Apalachicola River in the Florida Panhandle. Commanders of the new outpost then called upon Native Americans and fugitive African American slaves from across the region to join the British at the fort and together take up arms against the United States. Eventually, more than a thousand Creek, Choctaw, and Seminole Indians, along with several hundred runaways from southern plantations, accepted the invitation.

Following the final ratification of the Treaty of Ghent in the spring of 1815, the British withdrew their forces from Florida. With their powerful allies suddenly gone, most of the Indians gathered at the Apalachicola fort returned to their homes. But the hundreds of fugitive slaves inside the stockade had no place to go and so remained at the abandoned British post. And with the fort’s massive earthworks, wooden palisades and stone buildings at their disposal, along with an arsenal of hundreds of muskets, swords, bayonets and dozens of cannon, the runaways chose to remain there come what may.

Under an informal system of government that can best be described as martial law, this militant black community organized daily for its defence. At the same time, it established important relationships with the neighbouring Choctaws, Creeks, and Seminoles, who provided food and other sustenance in return for weapons and ammunition.

Negro fort was, in a word, formidable.

One British officer who, following the Treaty of Ghent, set out to assist some of the fugitive’s former owners regain their valuable property offered a curt assessment of fort’s inhabitants.

“The blacks are very violent & say they will die to a man rather than return.”

In the coming weeks and months, Hawkins and a number of prominent frontier citizens and officials flooded Washington with reports of rebellious slaves and their savage Indian allies running wild across the southern frontier. The accounts were almost entirely exaggerated.

Although clashes between Indians and settlers on disputed lands throughout the American south were commonplace in the early 19th Century, aside from inspiring an exodus of fugitive slaves from the southern states into Florida, the Negro Fort posed no threat to the United States.

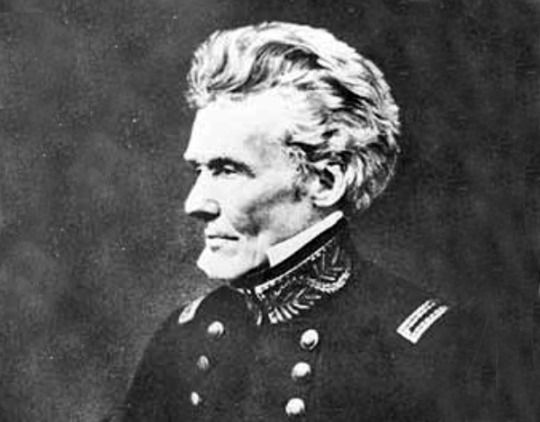

None of this stopped the commander of the United States’ southern army, General Jackson, from taking bold and aggressive action against the settlement.

Through a careful and calculating correspondence, Jackson ordered General Edmund Gaines, a hero of the War of 1812, invade Florida with 100 regulars, destroy the fort and return all of its black inhabitants to their American and Spanish owners. To ensure an American victory with as few friendly casualties as possible, Jackson secured the assistance of hundreds of Creek warriors by promising them a cash reward of as much as $50 dollars a head for every black slave returned to captivity.

Over the course of the next two weeks, hundreds of pro-American Creek warriors clashed with black rebels in the dense woods surrounding the fort, which at times descended into bloody hand-to-hand combat.

With American troops watching from a safe distance, the number of casualties went unrecorded—though it must have been considerable.

When a failed sortie by the fort’s defenders was repulsed, an American eyewitness suspected it was only a ruse.

“Many circumstances convinced us,” army doctor Marcus Buck wrote to his father, “that most of them determined never to be taken alive.”

With a pause in the ground fighting, American army and navy vessels on the river exchanged cannonfire with the fort’s defenders for several days.

The bombardment continued to the morning of July 27, when a heated cannonball, or “hotshot,” fired from U.S. Gunboat 154 flew over walls of Negro Fort’s massive inner citadel, landing directly on a gunpowder magazine.

The response of American officials to the destruction of Negro Fort was muted, largely because the entire campaign was illegal. After all, with neither congressional nor executive authority, the United States armed forces had invaded a foreign territory.

By contrast, southern slave owners hailed the battle’s outcome as the dawning of a new day. A Georgia writer expressed this view when reporting “the capture of the Negro and Indian Fort, on Apalachicola.” He explained that because of the efforts of his “brave countrymen,” the southern and western frontiers were now free of the “predatory incursions” posed by black and Indian bandits “whose numbers were daily augmenting; and whose strength and resources presented a fearful aspect to our peaceful borders.”

Within two years of the Battle of Negro Fort, Jackson and the American army again invaded Florida. The resulting First Seminole War would be the first of three wars between the United States and Florida’s black and Indian population who simply refused to submit to their northern American neighbours.

Though Negro Fort survived for only a year, its memory endured in the hearts and minds of hundreds of its inhabitants who had abandoned the outpost prior to its destruction. By fleeing to the Florida peninsula and aligning with the Seminole Indians, most of these former slaves carved out difficult but free lives on the outer edges of the American republic.

As many as one hundred of them were even more fortunate, finding not only freedom but peace and tranquility in the West Indies. By boarding trading vessels and escaping to the Bahama Islands several years after the Battle of Negro Fort, they completed the improbable journey from American slaves to British subjects.

#The Battle of ‘Negro Fort’ – Inside America's Forgotten Slave Rebellion#florida#negro fort#negro abraham#Freedmen#seminole indians#florida enslaved#history of slave settlements in florida

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

When the Seminole Indians Aligned With Escaped Slaves

The Black Seminoles were a group of people that history, for the most part, forgot about. Their alliance with the native Seminole tribes resulted in a unique relationship that had never been seen before, and that changed the course of history for both the Seminoles and the State of Florida as a whole.

The Black Seminoles, sometimes called Maroons, were a group of freed men and runaway slaves living in Florida during the mid-16th century. They settled the first free Black town in American history, attained their freedom by joining the Spanish and converting to Catholicism, and formed a tight cultural bond with the Seminole tribes.

#When the Seminole Indians Aligned With Escaped Slaves#Freedmen#florida#Seminoles#Black Indians#Black History Matters#Black History of Florida#Black History Month 2024#bhm24#2024#Youtube

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

Not sure if this is something that would be interesting for you to answer, but do you think there is any way a slave revolt at some point early on (or just before the civil war) could’ve established some kind of break away nation in the south? There’s so much emphasis on edge lord “what if the bad guys win!” type stuff that I’ve tried pondering this but I’m not sure if it would be possible. Do you think this could’ve been done with the right “here’s money to look the other way big northern business and political people?” Or would it always be doomed to fail because even if luck broke the revolt/revolutions way against the whole south the north would just send an army to quash it because most white northerners would still be upset white people were dieing/that part of the country was “being taken away.”

Ah, the dream of self-determination in the Black Belt...

So if we're talking sometime close to the Civil War, what we're really talking about is the John Brown scenario, whereby a state for freedmen would be established in the hill country of Appalachia. I think the problem is that, even had John Brown's raid on Harper's Ferry not gone awry so quickly (and had he had a more realistic number of soldiers), the speed at which a U.S military dominated by Southerners like Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson as well as multiple state militias mobilized to suppress the revolt speaks to how well-developed the American system of repressing slave revolts had become in the 19th century.

If we're talking earlier, then I think you do have some historical examples in the form of maroon communities like the Black Seminoles in Florida or the Great Dismal Swamp in Virginia and North Carolina, although there you're talking about runaways rather than a slave revolt. The problem as I see it is that you're combining the practical difficulties of carrying off a slave revolt - which always, always, always faced massive state repression - with the difficulties of maintaining an independent state in the face of American imperialism.

For example, the Black Seminoles were able to prosper in Florida because it was a Spanish colony and the Spanish had a policy of providing refuge to runaway slaves as a measure to destabilize the English and eventually Americans to their north - however, the existence of an armed native/freedmen state just on the other side of the Georgia state line prompted Andrew Jackson to launch a series of "punitive expeditions" that forced Spain to hand over Florida to the United States, which allowed him to bring in the U.S military to try to force the Seminoles into reservations and then try to remove them to Oklahoma. The Seminoles effectively used guerilla tactics to resist the U.S military for some time, but when they bring in 30,000 troops and use starvation tactics, they were absolutely decimated.

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

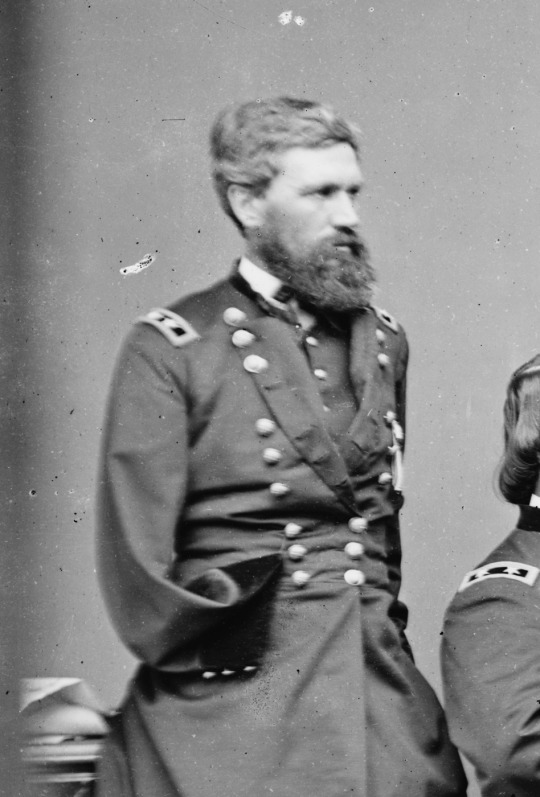

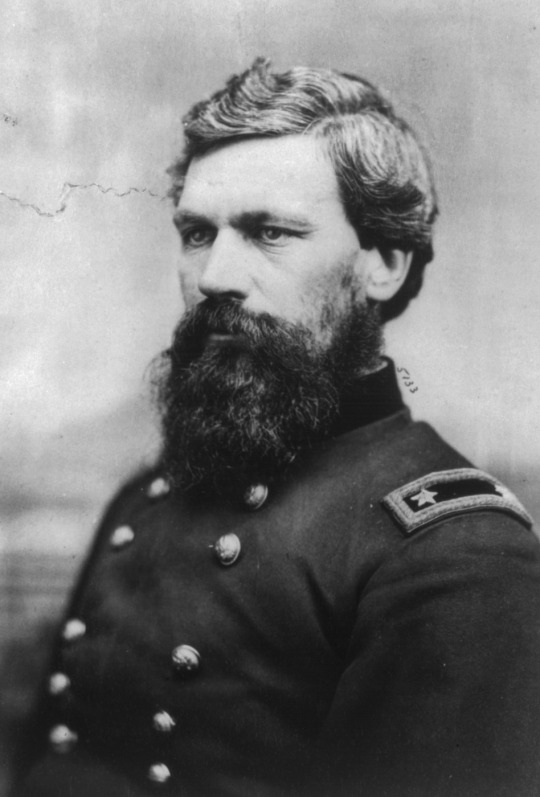

Known as “the Christian General,” Oliver Otis Howard is a unique figure in Civil War history. Despite lackluster performances by troops under his command, Howard’s reputation as an efficient and personally courageous officer would lead to command of an army by the war’s end.

Born in Leeds, Maine to Rowland Bailey and Eliza Otis Howard, young Oliver was educated in North Yarmouth, Maine before graduating from Bowdoin College in 1850. Immediately upon graduation, Howard received an appointment to West Point, joining a long gray line that also included Jeb Stuart, Dorsey Pender, and Commandant Robert E. Lee’s son, Custis. Howard graduated in 1854, fourth in a class of forty-six, one place behind future General Thomas H. Ruger.

In 1857, after routine assignments on the East coast, Howard took part in the campaign against the Florida Seminoles. It was here that the previously religious officer underwent a serious conversion to evangelical Christianity. Though he remained in the army, Howard often contemplated entering the ministry—even while serving as assistant professor of mathematics at West Point. Howard’s piety would later be source of ridicule for the general, and the sobriquet “the Christian General” was rarely used without some disdain.

But as history would have it, a certain grace seems to have accompanied Howard’s wartime service. In May of 1861, he was made colonel of the 3rd Maine Volunteer Infantry, resigning his regular army commission. He commanded a brigade at the First Battle of Bull Run, and though driven from the field in confusion, was promoted to brigadier general that fall. Again at the head of a brigade in the Union Second Corps in the spring of 1862, Howard lost his right arm at the battle of Seven Pines but would return to the field in time to form the Army’s rear guard at Second Manassas. Three weeks later, at the battle of Antietam, he relieved wounded division commander John Sedgwick, and would retain the command until the end of the year.

In the spring of 1863, following his promotion to major general, Howard was elected to replace Franz Sigel as the head of the XI Corps. A revolutionary from Germany, the immensely popular Sigel was the perfect choice to lead the predominantly German unit. Howard, however, with his penchant for strict military and moral discipline, did little to gain the respect of his troops before the battle of Chancellorsville. Posted on the right flank on May 2, 1863, Howard’s men bore the brunt of Stonewall Jackson’s devastating flank attack. Though the corps commander displayed personal bravery in attempting to rally his troops, many—including Army commander Joseph Hooker—blamed Howard and his “flying Dutchmen” for the Union rout. These same troops would flee in confusion two months later at the battle of Gettysburg. Their commanding officer, however, would receive the thanks of the United States Congress for selecting the ground upon which the next days’ battle was fought—a deed most attributed to Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock.

Sent to the aid of William Rosecrans’ Army of the Cumberland at Chattanooga in the autumn of 1863, Howard remained in the western theatre for the duration of the war. In May of 1864, he led the IV Corps during William T. Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign. Following the death of James B. McPherson, Sherman selected the Christian General to head up the Army of Tennessee during his scorched earth campaign through the Carolinas. Howard finished the war a brigadier general in the Regular Army, ranking from the capture of Savannah.

An ardent abolitionist before the war, Howard’s postwar days were spent looking after the welfare of the recently emancipated slaves. In May of 1865, he was made the first and only commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau, and though the organization itself was rife with corruption, Howard again emerged from the ordeal unscathed. He went on to serve as superintendent of West Point and in 1893 received the Medal of Honor for bravery at the Battle of Seven Pines. He retired from the Army, a major general, in 1894.

Howard continued to be interested in education late into his life. Having founded Howard University in 1867, the general was also instrumental in the establishment of Lincoln Memorial University in the mountains of Tennessee. Oliver Otis Howard died in October of 1909 in Burlington, Vermont, where he is buried in Lake View Cemetery.

#oliver otis howard#american civil war#civil war#history#so this info about howard is taken from the american battlefield site#and if you've watched some of their stuff there's a guy named kris who uh doesn't like howard lol#and i can feel a little bit of him in this write up which is pretty funny#but yes! ol' O.O.Howard....great head of hair

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sugar T. George a.k.a. George Sugar (C. 1827 - June 30, 1900) was born as a slave in the Muskogee Nation. This former slave emerged as a tribal leader. By the time of his death, he was said to have been the “wealthiest Negro in the [Indian] Territory.” He escaped from bondage when in November 1861, Opothleyohola, an Upper Creek chief, led 5,000 Creeks, 2,500 Seminoles, Cherokees, and other Indians, and approximately 500 slaves and free blacks from Indian Territory into Kansas to avoid living under the domination of Pro-Confederate Indian leaders during the Civil War. He joined the Union Army in Kansas, serving in Company H of the 1st Indian Home Guards. Because of his natural skills as a leader and his literacy he became a First Sergeant in his unit. He acted as the unofficial leader of Company H, taking charge after the white officer and Indian officer had been dismissed for improper behavior. After the War he rose to prominence, amassing money and influence in the Muskogee (Creek) Nation. He settled in North Fork, Colored Town, in the Nation and became a Town King (mayor). He served as a legal witness for his neighbors and often prepared letters for illiterate people in the community. In 1868 he was first elected to the Muskogee National Tribal Council, representing North Fork in both the House of Warriors and the House of Kings. He served in the National Muscogee legislature until 1895. He served on the board of the Tullahassee Mission School, a school for Creek and Seminole freedmen. He married twice in his lifetime, first to Mariah McIntosh who died in 1867, and then in 1876 to Betty Rentie. He and Betty had no children, but they adopted and raised James Sugar as their son. He raised his step-grandchildren, Rena and Julia Sugar. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence https://www.instagram.com/p/CfbOu6guCKqi9DffotKWNjrGDO-NsxvLYf2eoA0/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The last community gets three articles for a very obvious reason:

Their existence not only shaped the definition of the USA's southern boundaries (and under the current Governor of Florida's system as such the beginning of Florida's history is now illegal to teach in the state), but did so in a way that helped to launch the career of one Andrew Jackson and touched off the longest Indian War in the Southern United States.

And the reasons for this were that Spanish power in Florida was fairly weak, US power in southern Georgia was weaker, and Maroons took advantage of obvious weaknesses to run away from slavery and built up a strong, well-armed community in alliance with the new Simanoli/Seminole people formed out of the shattered nations of Spanish power and the fall of the Mississippians.

For the so-called 'democrat', the existence of a Black and Indigenous alliance on the border of the Slave Power was an intolerable slight and it was his legacy that set in motion the annexation of Florida and three bloody wars to squelch it.

#lightdancer comments on history#black history month#black resistance#slavery and resistance#florida history#black history is florida history#fuck you ron desantis#seminole wars#black seminoles

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Oh yes I’m Gullah and we’re indigenous to Africa and reside in lowcounty. We’re also slowly losing our language and land here in the United States due to climate change and also other things. Seminole people also are descents of Gullah freedmen and native Americans. And there has been some mixing of native and Gullah people in the lowcounty. And from the 5 civilized tribes I would likely (still unsure) be mvskoke which is creek/Musc(k)ogee. Thank you for this conversation by the way I’d still have to do much more research of course. I’m also curious on how you would know if your ancestors were registered under one of the 5 tribes, I’ll look into that also I suppose. I don’t know if I’ll come off anon I’m actually really shy lol. No problem with the responds btw.

Oh i didnt know that Im so sorry about your language thats always such a devestating thing to know and deal with. Hopefully in the coming heres there will be more towards language revitalizing and conservation to make sure languages are kept alive

Best place to start is to contact the tribes (they have their own webbed sites) and pretty much tell them your situation and what to do next. Remember that you are not a burden or a hindrance, you are not bothering them. You are trying to find information.

Most likely they will ask you some questions or direct you to links to archives and what not.

But also i recommend taking a dna test on at least the top 2 or 3 dna test sites mostly to get matched up with cousins so that you can contact them and see if they have any info

Because maybe they have leads, maybe a name. So if you havnt done that thats also a good place to start

And dont worry about it, you can stay on anon if you feel more comfortable that way!

Also i recommend going into the Indian Country subreddit and Native American subreddit and post an ask there to get some suggestions on what to do, maybe even someone whos willing to help (you can make a throwaway account to feel more anonymous which may help shyness).

Ive posted there before and have had a lot of help and direction. And no need to mention your BQ, its no ones buisness.

But yeah 1. Contact the tribes and tell them your situation, ask them where to go from there 2. go into reddit and see if theres someone willing to help or give suggestions and 3. do a dna test on like ancestory and 23&me so you can maybe find some relatives that can give you more info

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oklahoma-based tribes say followed rules on Freedmen rights

Oklahoma-based tribes say followed rules on Freedmen rights

Leaders and representatives of five Oklahoma-based tribes on Wednesday told a U.S. Senate committee that they have followed treaties and court rulings regarding the citizenship of Freedmen and that the federal government should respect their sovereignty.

Freedmen were the freed Black people enslaved by the Cherokee, Seminole, Choctaw, Muscogee (Creek) and Chickasaw nations. They were guaranteed…

View On WordPress

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Image #1

Rhonda Grayson, with an image of her great-great grandfather Willie Cohee.

Image #2

Johnnie Mae Austin, whose grandfather was ‘Creek to the bone,’ is a plaintiff in the Creek Freedmen suit. Photograph: Brett Deering/The Guardian

Suing to Reclaim Identity... Is this Action?

The Facts

The ability to sue a nation that has deprived them of connection to their identity is a great source to call for action. Black Native Americans who were apart of the Creek Nation are almost never allowed to join this tribe due the constitution made in 1979. The tribe made this constitution to prevent them from joining. The tribe actually took a vote to "reconstitute citizenship parameters", this kicked out black people who have been members since 1866. The citizenship was limited to the blood quantum which I have talked about in previous posts (Having to have a certain amount of blood to be required Native American). This case for Johnnie Mae Austin to prove her lineage of creek blood which can be found in the "Creek Freedman list of the Dawes roll" still is hindered based upon the perception that there still is not enough Native American blood. The Creek Nation has stated they are a "independent agency", Austin's attorney is sure they have to follow the law just as anyone else. This case may end similar as the lost taken by the Seminole tribes for this case problem.

Highlights from the Stories

"Johnnie Mae Austin and her grandson, Damario Solomon-Simmons, can tell you everything about their ancestry. They can go back as far as 1810, the year Solomon-Simmons’ great-great-great-great-grandfather, Cow Tom, was born. With undeniable pride, they recount the man’s feats of bravery during the civil war, and his leadership within Oklahoma’s Creek population."

"In fact, they are so determined to let the world know exactly who Cow Tom was that they’re suing the Creek nation to make sure his descendants aren’t forgotten."

"Roberts says the actual disenfranchisement of black people by the Creeks and the Cherokee started in the late 20th century coincided with a time when a lot of the tribes had begun to build their economies and make a lot of money. She points out this was precisely the time when many of the Nations started to see an “influx of enrollment applications”.

"The current Creek principal chief, Jamie Floyd, declined to comment, and his press officers referred me to the nation’s citizenship office led by Nathan Wilson. “We’re an independent agency constitutionally and we’re listed in the Constitution as independent,” Wilson told me."

"But the vagueness of the nation’s response shouldn’t be read as a dismissal of the importance of the citizenship issue. In fact, the Creek nation is lawyering up. Venable LLP, a top Washington DC law firm, contacted Solomon-Simmons in August on behalf of the Creek nation. Both the Creek nation and the interior department have filed motions to dismiss on 5 October and the court will respond on 2 November."

Read Entire Story Here

0 notes

Note

reservation dogs is filmed in oklahoma where it has a large native population and im sure they have black natives there to.

but the reason why they are being left out is because of course antiblackness and including in the old days, there were 5 native american tribes, called the 5 civilized tribes, that practiced white customs and owned black slaves.

and as of today, they treat their freedmen descendants like trash. not too long ago, black seminoles in oklahoma were denied the covid vaccine, basically the tribe broke their own constitution.

and the freedmen are constantly in this long court battle fighting for their rights. we need to support them every way we can

I wonder if he'd ever acknowledge that 🙄

1 note

·

View note

Text

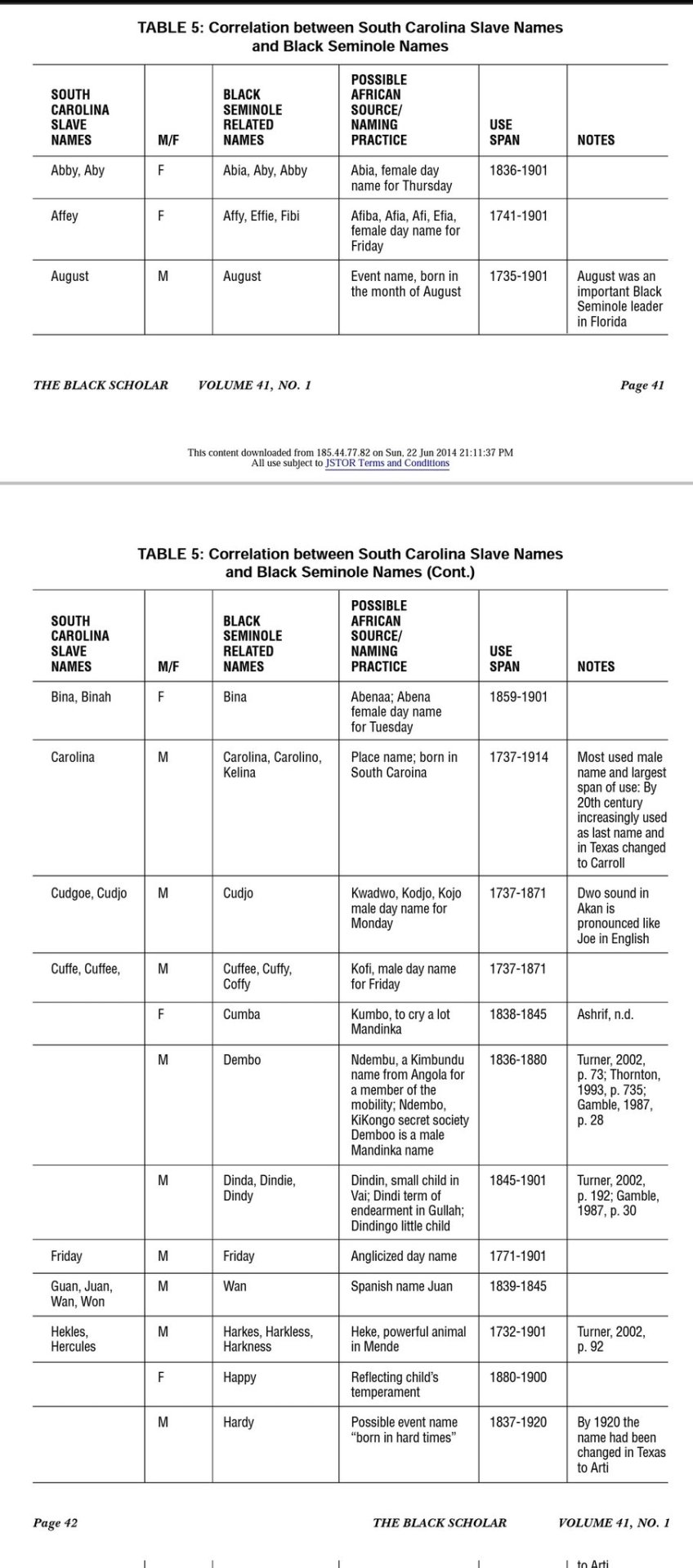

If the Black Seminoles were Indians, why did they speak African Creole & had African names?

youtube

#If the Black Seminoles were Indians#why did they speak African Creole & had African names?#Africans#Freedmen#Indians#cherokees#Black Seminoles#Youtube

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

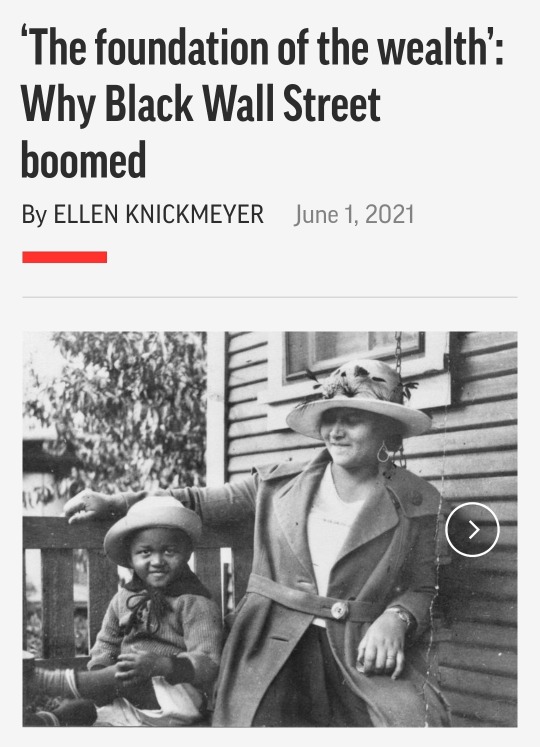

Unlike Black Americans across the country after slavery, Williams’ ancestors and thousands of other Black members of slave-owning Native American nations freed after the war “had land,” says Williams, a Tulsa community activist. “They had opportunity to build a house on that land, farm that land, and they were wealthy with their crops.”

“And that was huge ��� a great opportunity and you’re thinking this is going to last for generations to come. I can leave my children this land, and they can leave their children this land,” recounts Williams, whose ancestor went from enslaved laborer to judge of the Muscogee Creek tribal Supreme Court after slavery.

In fact, Alaina E. Roberts, an assistant professor at the University of Pittsburgh, writes in her book “I’ve Been Here All the While: Black Freedom on Native Land,” the freed slaves of five Native American nations “became the only people of African descent in the world to receive what might be viewed as reparations for their enslavement on a large scale.”

Why that happened in the territory that became Oklahoma, and not the rest of the slaveholding South: The U.S. government enforced stricter terms for reconstruction on the slave-owning American Indian nations that had fully or partially allied with the Confederacy than it had on Southern states.

While U.S. officials quickly broke Gen. William T. Sherman’s famous Special Field Order No. 15 providing 40 acres for each formerly enslaved family after the Civil War, U.S. treaties compelled five slave-owning tribes — the Choctaws, Chickasaws, Cherokees, Muscogee Creek and Seminoles — to share tribal land and other resources and rights with freed Black people who had been enslaved.

By 1860, about 14% of the total population of that tribal territory of the future state of Oklahoma were Black people enslaved by tribal members. After the Civil War, the Black tribal Freedmen held millions of acres in common with other tribal members and later in large individual allotments.

The difference that made is “incalculable,” Roberts said in an interview. “Allotments really gave them an upward mobility that other Black people did not have in most of the United States.”

The financial stability allowed Black Native American Freedmen to start businesses, farms and ranches, and helped give rise to Black Wall Street and thriving Black communities in the future state of Oklahoma. The prosperity of those communities — many long since vanished —“attracted Black African Americans from the South, built them up as a Black mecca,” Roberts says. Black Wall Street alone had roughly 200 businesses.

Meeting the Black tribal Freedmen in the thriving Black city of Boley in 1905, Booker T. Washington wrote admiringly of a community “which shall demonstrate the right of the negro, not merely as an individual, but as a race, to have a worthy and permanent place in the civilization that the American people are creating.”

And while some tribes reputedly gave their Black members some of the worst, rockiest, unfarmable land, that was often just where drillers struck oil starting in the first years of the 20th century, before statehood changed Indian Territory to Oklahoma in 1907. For a time it made the area around Tulsa the world’s biggest oil producer.

For Eli Grayson, another descendant of Muscogee Creek Black Freedmen, any history that tries to tell the story of Black Wall Street without telling the story of the Black Indian Freedmen and their land is a flop.

“They’re missing the point of what caused the wealth, the foundation of the wealth,” Grayson says.

The oil wealth, besides helping put the bustle and boom in Tulsa’s Black-owned Greenwood business district, gave rise to fortunes for a few Freedpeople that made headlines around the United States. That included 11-year-old Sarah Rector, a Muscogee Creek girl hailed as “the richest colored girl in the world” by newspapers of the time. Her oil fortune drew attention from Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Dubois, who intervened to check that Rector’s white guardian wasn’t pillaging her money.

The wealth from the tribal allotment also gave rise to Williams’ family story of great-aunt Janie, “who learned to drive by going behind the trolley lines” in Tulsa, with her parents in the car, Williams’ uncle, 67-year-old Samuel Morgan, recounted, laughing.

“It was real fashionable, because it was one of the cars that had four windows that rolled all the way up,” Morgan said.

Little of that Black wealth remains today.

In May 1921, 100 years ago this month, Aunt Janie, then a teenager, had to flee Greenwood’s Dreamland movie theater as the white mob burned Black Wall Street to the ground, killing scores or hundreds — no one knows — and leaving Greenwood an empty ruin populated by charred corpses.

Black Freedmen and many other American Indian citizens rapidly lost land and money to unscrupulous or careless white guardians that were imposed upon them, to property taxes, white scams, accidents, racist policies and laws, business mistakes or bad luck. For Aunt Janie, all the family knows today is a vague tale of the oil wells on her land catching fire.

Williams, Grayson and other Black Indian Freedmen descendants today drive past the spots in Tulsa that family history says used to belong to them: 51st Street. The grounds of Oral Roberts University. Mingo Park.

That’s yet another lesson Tulsa’s Greenwood has for the rest of the United States, says William A. Darity Jr., a leading scholar and writer on reparations at Duke University.

If freed Black people had gotten reparations after the Civil War, Darity said, assaults like the Tulsa Race Massacre show they would have needed years of U.S. troop deployments to protect them — given the angry resentment of white people at seeing money in Black hands.

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alice Brown Davis

The first female Principal Chief of the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, Alice Brown David (1852-1935) was an educator, a politician, and an advocate for Native issues.

One of seven children, Brown was a member of the Seminole Katcvlke, or Tiger Clan. When she was just 15, a cholera epidemic broke out in the tribe and both her parents died. She moved in with her older brother where she completed her education and began teaching others, both Seminole children and the children of freedmen.

As she grew, she received more and more prominence. When her brother, John F. Brown, was Chief, she worked as an interpreter and liaison. She was the postmistress, the superintendent of the Seminole Nation's girl's school, and a delegate to Mexico. Brown was fluent in English and Mikasuki.

In 1922, Brown was appointed the Principle Chief of the Seminole Nation by President Harding following the death of her brother. She was the first female Chief in Seminole history, and her appointment was controversial at first. As Chief, she won the respect of her people and focused on retaining and obtaining land, especially refusing to allow education to be taught by non-Native people. Tribal land affairs were her key political issue, including land allotments and oil leases.

#american history#world history#history#indigenous history#20th century#badass women#us history#women in history#alice brown davis#seminole#seminole county#seminole tribe#seminole nation#tiger clan#native americans#nativeamericans#native women#american indian movement#indigenous#land back#decolonization#indigenous sovereignty#indigenous people#indigenous resistance#decolonize

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Native Americans weren't alone on the Trail of Tears. Enslaved Africans were, too

New Post has been published on https://appradab.com/native-americans-werent-alone-on-the-trail-of-tears-enslaved-africans-were-too/

Native Americans weren't alone on the Trail of Tears. Enslaved Africans were, too

Her father’s ancestors in Oklahoma were once enslaved by Native Americans.

Nearly a century before Tulsa’s Greenwood District became a beacon of Black prosperity in the 1920s, Native American tribes and thousands of enslaved Black people arrived in the state. Members of the Five Tribes — the Chickasaw, Cherokee, Choctaw, Creek and Seminole — had been forced out of their homelands in the Deep South, leading to the exodus known as “Trail of Tears.”

For Roberts, the 1921 Tulsa Massacre is only a portion of the complicated history of Black, Native American and White people in Oklahoma.

After the Civil War, the Five Tribes signed a treaty with the US government abolishing slavery. Those formerly enslaved by the tribes, known as freedmen or freedpeople, built churches and schools. They later received land allotments as part of the 1887 Dawes Act, which dismantled Indigenous reservations and redistributed the land. Some were granted tribal citizenship but many were not.

Roberts’ great-great-grandmother was among the thousands of Black women and men once held in bondage by the Chickasaw tribe who received land allotments. Her family has now lived in the state for generations.

Black people began building wealth and founded all-Black towns. By the late 19th century, Oklahoma attracted people of all races who saw it as an opportunity for a fresh start, landownership and prosperity. But soon it became a hotbed for racial tensions.

Roberts recently spoke with Appradab about her book, the quests for land and freedom in the years leading to the Tulsa Massacre and how learning about Oklahoma’s past changed her views on race. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

It can be hard to talk about this period of history because of how complex it is and because it involves several communities of color. What would you tell people who prefer to avoid this complicated conversation?

It’s certainly difficult. It’s not the happy narrative that we sometimes want to think about. I think that if we want to come together today and form interracial coalitions — like last year’s Black Lives Matter protests and how people of different races have come together to fight against anti-Asian hatred — in a powerful and honest way, we need to acknowledge the past and the issues that we’ve had there.

In the case of the formerly enslaved Black people, they had a chance to leave Oklahoma after Emancipation and as you mention in the book, blend as African Americans in the United States’ territories, but many stayed, including your great-great grandmother. Why?

I argue that it’s really the land and the communities that they built within these Indian nations that ends up being more important to them than political rights. So instead of going to the United States and joining this congressional action that is happening right after the Civil War with Republicans, they decided to stay in (tribal) nations where they don’t necessarily have all the rights. For my ancestors in Chickasaw Nation, they don’t have rights as citizens at all but being able to really stay together with their communities and being able to own land is more important to them.

At this point in time, two different groups of formerly enslaved people merged on Indian territory: those who were brought by the Five Tribes and Black people who fled the South. Why was this region such an attractive destination for all of them?

After emancipation, African Americans are moving to various places. They move to urban places in the North. They move to some other places in the West like Kansas, Nebraska, etcetera. Indian Territory is especially attractive to them because they are able to see that Indian freedpeople are getting land and that they have various rights that African Americans in the South are not able to exercise. Indian territory looks to them almost like a racial paradise. They can have these rights, they can maybe get land and they don’t have to suffer from White violence.

How did Native Americans react to the changes and the waves of migration?

Their response to both White and Black migration was fear. They knew that more Americans coming meant more changes in the way the United States treated them. For example, in the 1890s there were lots of White and Black people there and the US government basically said they were not going to allow them to try White people in tribal courts and started shutting them down. That is an important part of a nation, your courts and your ability to try crimes. They (Five Tribes) tried to fight back by trying to stop this immigration and for African Americans, the rhetoric was quite racist. They were afraid their nation would be seen as full of black people and therefore not seen as Indian.

In the years leading up to the Tulsa Race Massacre, how did Black people build wealth and a thriving community in Oklahoma?

Freedpeople are obtaining their land allotments in the 1890s and onward. Some of those are on places that have timber and they were able to sell it. Some of were just good farming lands and they were able to create farms and communities. For some very lucky people it’s on oil and gas reserves. In the early 1900s when that becomes very valuable and usable, some of those people get rich, and that draws more people to the area. Then, they are able to use that wealth to create businesses and then draw other business owners and entrepreneurs to the area.

What made Tulsa stand out from other towns in the region?

Primarily the oil that was in the area. Tulsa was situated in there because of those natural resources while other towns like Boley (Oklahoma) where near railroad stops and land allotments. There were a lot more wealthy people in Tulsa who had the capital to create businesses but certainly, there were also profitable businesses in other Black towns as well.

You said in the book that the Tulsa Race Massacre represents the end of the largest representation of what Black people were able to build and that White Americans rose up against Black success. A hundred years later, how are we still seeing its impact?

Almost more than the impact of the massacre, we feel the impact of the erasure of the massacre. Many stereotypes about Black people revolve around the idea that they’re lazy, they’re not smart, they don’t create businesses for themselves, they don’t create opportunities for themselves Why are they the poorest, least educated demographic in the United States? People blame African Americans for their own issues. But “Black Wall Street” is an example of how African Americans and Indian freedpeople (those formerly enslaved by tribes) built an amazing community for themselves. They were very much willing to work hard and create things for themselves, it’s just that White racism destroyed that.

We have lots of instances where Black communities and Black businesses have been destroyed by White racism. It’s is a lack of desire on the part of White Americans to remember that history. Instead, they whitewash it so that it seems like it’s African Americans’ fault.

As you mention in the book, it was hope what kept drawing people from all over the country to Oklahoma. What does that tell you about people in this country, especially people of color?

I think the United States has created a narrative around itself that says anyone can come here and become wealthy and become accepted. That really appeals to White people. It also appeals to people of color who even though they know they are going to face discrimination and inequality, they still are willing to try as hard as possible to make that real for themselves. Some do achieve that dream.

The kind of unfortunate point of my book is that, for people of color, there’s always going to be discrimination and there’s always going to be White supremacy that can possibly undo everything that you’ve worked so hard for.

You make it clear in the book that in this region, the success of some people came at the expense of others and it was something that happened over and over again. What has it been like for you to learn that?

It put into a different perspective the stories that we often tell about Black towns, Black spaces, and Black migration to the North and to the West. These are amazing stories and we should celebrate them but we should also talk about the Native Americans who lived there before or sometimes lived there at the same time because without that, it seems like Black people come here and created something that wasn’t there before. Acknowledging Black history is just as important as acknowledging Native American history, and often those narratives go hand in hand to tell a more complete story of our history in this country.

Has learning about the complicated history of Oklahoma and your family’s land changed how you think about race today?

Yes. I think I see more how White supremacy has influenced the way people of color think about each other. We’ve seen that in a number of the attacks on Asian people that have been perpetrated by Black people or other people of color. People of color can have problematic ideas and discriminatory ideas about other people of color. It has made me realize that this is still an issue, and that we need to talk about racism and prejudice as it is in all of our communities, and not just the White community.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

•The life of John Horse structures the trail narrative and stands as the consummate expression of the Black Seminoles' nineteenth-century odyssey. •Though not widely known, this black pioneer's life forms one of the most heroic chapters of frontier America -- an Homeric hymn to the ideals, injustice, and complexities of the American experiment. Via Seminole Nation Museum #Black #Seminoles, also called #SeminoleMaroons or #SeminoleFreedmen, a group of free blacks and runaway slaves (#maroons) that joined forces with the Seminole Indians in Florida from approximately 1700 through the 1850s. The #BlackSeminoles were celebrated for their bravery and tenacity during the three Seminole Wars. Via Encyclopedia Britannica •Born in Spanish Florida in 1812 of allegedly mixed #African and #Indian ancestry, John Horse rose to prominence during the Second #SeminoleWar (1835-1842). Several times during the conflict, his daring exploits sparked new life into the allied #Seminole resistance. By 1837, he led the black portion of the uprising in the climactic Battle of Lake Okeechobee. More than any other leader, his actions helped produce the promise of freedom that the U.S. Army extended to black rebels to close out their portion of the war. •For forty years after the rebellion, #JohnHorse led his followers in #Oklahoma, #Texas, and #Mexico as they overcame slave raiders, corrupt politicians, and hostile Native Americans in their pursuit of a free homeland. •Out west, with strong ties to both the Army and the Seminole tribal leadership, John Horse could have pursued security for himself and his family. Instead, he chose to pursue the wider good of his community. This course of action nearly got him killed on several occasions, but it ultimately allowed him to contribute to the lives of all Americans by advancing the cause of national freedom. •Not only did John Horse's actions save hundreds of lives from slavery, but his leadership, albeit anonymously, inspired the country's leading #abolitionists. Via https://www.seminolenationmuseum.org/m.blog/23/the-seminole-freedmen-a-brief-history #worldhistory #NativeHistory #Americanhistory #ushistory #blackhistorymonth #blackhistory (at United States) https://www.instagram.com/p/CLuPAcchfDI/?igshid=qcig5reda2bo

#black#seminoles#seminolemaroons#seminolefreedmen#maroons#blackseminoles#african#indian#seminolewar#seminole#johnhorse#oklahoma#texas#mexico#abolitionists#worldhistory#nativehistory#americanhistory#ushistory#blackhistorymonth#blackhistory

3 notes

·

View notes