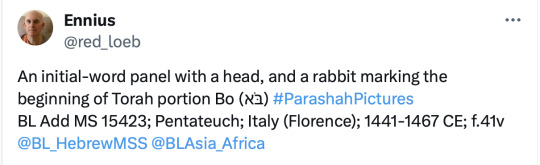

#Pentateuch; Italy

Text

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today In History:

A bit of January 26th history…

1482 - “Pentateuch”, the Jewish Bible, is printed as a book in Italy

1500 - Vicente Pinzon becomes 1st European to set foot in Brazil

1564 - The Council of Trent issues it’s conclusions in the Tridentinum, establishing a distinction between Roman Catholicism and Protestantism

1905 - World’s largest diamond, 3,106 carat Cullinan, is found in South Africa

1926 - John Baird gives 1st public demonstration of television in his lab in London (pictured)

1950 - Constitution of independent India comes into effect

0 notes

Photo

A bit of January 26th history...

1482 - “Pentateuch”, the Jewish Bible, is printed as a book in Italy

1500 - Vicente Pinzon becomes 1st European to set foot in Brazil

1564 - The Council of Trent issues it’s conclusions in the Tridentinum, establishing a distinction between Roman Catholicism and Protestantism

1905 - World’s largest diamond, 3,106 carat Cullinan, is found in South Africa (pictured)

1926 - John Baird gives 1st public demonstration of television in his lab in London

1950 - Constitution of independent India comes into effect

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saints&Reading: Mon., July, 26, 2021

July 26 (old cal.)_ July 13 ( new cal.)

SYNAXIS OF THE ARCHANGEL GABRIEL

Synaxis of the Holy Archangel Gabriel: The Archangel Gabriel was chosen by the Lord to announce to the Virgin Mary about the Incarnation of the Son of God from Her, to the great rejoicing of all mankind. Therefore, on the day after the Feast of the Annunciation, the day on which the All-Pure Virgin is glorified, we give thanks to the Lord and we venerate His messenger Gabriel, who contributed to the mystery of our salvation.

Gabriel, the holy Archistrategos (Leader of the Heavenly Hosts), is a faithful servant of the Almighty God. He announced the future Incarnation of the Son of God to those of the Old Testament; he inspired the Prophet Moses to write the Pentateuch (first five books of the Old Testament), he announced the coming tribulations of the Chosen People to the Prophet Daniel (Dan. 8:16, 9:21-24); he appeared to Saint Anna (July 25) with the news that she would give birth to the Virgin Mary.

The holy Archangel Gabriel remained with the Holy Virgin Mary when She was a child in the Temple of Jerusalem, and watched over Her throughout Her earthly life. He appeared to the Priest Zachariah, foretelling the birth of the Forerunner of the Lord, Saint John the Baptist.

The Lord sent him to Saint Joseph the Betrothed in a dream, to reveal to him the mystery of the Incarnation of the Son of God from the All-Pure Virgin Mary, and warned him of the wicked intentions of Herod, ordering him to flee into Egypt with the divine Infant and His Mother.

When the Lord prayed in the Garden of Gethsemane before His Passion, the Archangel Gabriel, whose very name signifies “Man of God” (Luke. 22:43), was sent from Heaven to strengthen Him.

The Myrrh-Bearing Women heard from the Archangel the joyous news of Christ’s Resurrection (Mt.28:1-7, Mark 16:1-8).

Mindful of the manifold appearances of the holy Archangel Gabriel and of his zealous fulfilling of God’s will, and confessing his intercession for Christians before the Lord, the Orthodox Church calls upon its children to pray to the great Archangel with faith and love.

SAINT JULIAN, BISHOP OF CENOMANEA_ Le Mans _ Gaul_( 1st c.)

Saint Julian, Bishop of Cenomanis, was elevated to bishop by the Apostle Peter. Some believe that he is the same person as Simon the Leper (Mark 14:3), receiving the name Julian in Baptism.

The Apostle Peter sent Saint Julian to preach the Gospel in Gaul. He arrived in Cenomanis (the region of the River Po in the north of present day Italy) and settled into a small hut out beyond a city (probably Cremona), and he began to preach among the pagans. The idol-worshippers at first listened to him with distrust, but the preaching of the saint was accompanied by great wonders. By prayer Saint Julian healed many of the sick. Gradually, a great multitude of people began to flock to him, asking for help. In healing bodily infirmities, Saint Julian healed also the souls, enlightening those coming to him by the light of faith in Christ.

In order to quench the thirst of his numerous visitors, Saint Julian, having prayed to the Lord, struck his staff on the ground, and from that dry place there came forth a spring of water. This wonder converted many pagans to Christianity. One time the holy bishop wanted to see the local prince. At the gate of the prince’s dwelling there sat a blind man whom Saint Julian pitied, and having prayed, gave him his sight. The prince came out towards the holy bishop, and having only just learned that he had worked this miracle, he fell down at the feet of the bishop, requesting Baptism. Having catechized the prince and his family, Saint Julian imposed on them a three-day fast, and then he baptized them.

On the example of the prince, the majority of his subjects also converted to Christ. The prince donated his own home to the bishop to build a temple in it, and he provided the Church with means. Saint Julian fervently concerned himself with the spiritual enlightenment of his flock, and he healed the sick as before. Deeply affected by the grief of parents, the holy bishop prayed that God would restore their dead children to life. The holy Bishop Julian remained long on his throne, teaching his flock the way to Heaven. The holy bishop died in extreme old age. To the end of his days he preached about Christ and he completely eradicated idolatry in the land of Cenomanis.

LUKE 10:16-21

16 He who hears you hears Me, he who rejects you rejects Me, and he who rejects Me rejects Him who sent Me. 17 Then the seventy returned with joy, saying, "Lord, even the demons are subject to us in Your name." 18 And He said to them, "I saw Satan fall like lightning from heaven. 19 Behold, I give you the authority to trample on serpents and scorpions, and over all the power of the enemy, and nothing shall by any means hurt you. 20 Nevertheless do not rejoice in this, that the spirits are subject to you, but rather rejoice because your names are written in heaven. 21 In that hour Jesus rejoiced in the Spirit and said, "I thank You, Father, Lord of heaven and earth, that You have hidden these things from the wise and prudent and revealed them to babes. Even so, Father, for so it seemed good in Your sight.

HEBREWS 2:2-10

2 For if the word spoken through angels proved steadfast, and every transgression and disobedience received a just reward, 3 how shall we escape if we neglect so great a salvation, which at the first began to be spoken by the Lord, and was confirmed to us by those who heard Him,4 God also bearing witness both with signs and wonders, with various miracles, and gifts of the Holy Spirit, according to His own will? 5 For He has not put the world to come, of which we speak, in subjection to angels. 6 But one testified in a certain place, saying:"What is man that You are mindful of him, Or the son of man that You take care of him? 7 You have made him a little lower than the angels; You have crowned him with glory and honor, And set him over the works of Your hands. 8 You have put all things in subjection under his feet." For in that He put all in subjection under him, He left nothing that is not put under him. But now we do not yet see all things put under him. 9 But we see Jesus, who was made a little lower than the angels, for the suffering of death crowned with glory and honor, that He, by the grace of God, might taste death for everyone. 10 For it was fitting for Him, for whom are all things and by whom are all things, in bringing many sons to glory, to make the captain of their salvation perfect through sufferings.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today In History:

A bit of January 26th history…

1482 - “Pentateuch”, the Jewish Bible, is printed as a book in Italy

1500 - Vicente Pinzon becomes 1st European to set foot in Brazil

1564 - The Council of Trent issues it’s conclusions in the Tridentinum, establishing a distinction between Roman Catholicism and Protestantism

1905 - World’s largest diamond, 3,106 carat Cullinan, is found in South Africa

1926 - John Baird gives 1st public demonstration of television in his lab in London (pictured)

1950 - Constitution of independent India comes into effect

0 notes

Text

Herodotus and Ibn Khaldun, historians of the Mediterranean world, and myth and history in the making of the musics of the Mediterranean

“1. Imagining the Mediterranean

Music begins in the myths of the ancient Mediterranean world, and it ends in the diasporas of modernity. In between the ancient and the modern is history: music history and world history. In between the ancient and the modern is the intellectual history of imagining the Mediterranean as a border between the West and what lies beyond, between self and other, between us and them. Myth and history intersect and interact wherever we search in the Mediterranean, and they are perpetually being interwoven with music and music-making. So sweeping is the interaction of music and myth that we might argue that it is the sheer abundance of myths that narrates the landscapes of the Mediterranean, landscapes past and present, which become the basis for the sacred journeys that geographically connect the mythologies of the Mediterranean. Myth represents a Mediterranean musical landscape that is both complex and unified, both bounded and unbounded.

History forms along the borders the Mediterranean in different ways. Historians of the Mediterranean world have sought to unravel the juxtapositions of myth and therefore to separate history from myth. In the intellectual history of the West, Herodotus often assumes the position of the "first historian," usually because his fifth-century BCE Histories reflected back on a past that was no longer his own, but rather belonged to those who had come from elsewhere. Herodotus was an inveterate traveler, and he therefore connected time to specific events and specific actors in the cultures of their origins, many of which Herodotus visited as an ethnographer. Accordingly, Herodotus also enjoys the historiographical position as the first anthropologist of the Mediterranean and the world beyond (Hodgen 1964: 20-3).

Hecateaus' map of the world.

(Adapted from the Cambridge Ancient History, vol.III, no.3, 2nd edition, fig.35; after the Grosser historischer Weltatlas, vol. I)

History dispelled myth for the Greeks, and it became a voice for colonial expansion from the Mediterranean's northern shore, into the Middle East, as in the case of Josephus's accounts of the Jewish wars. History-writing was, nonetheless, not entirely the domain of the Europeans of the Mediterranean, for there were Arab scholars, such as the fourteenth-century polymath, Ibn Khaldun, whose Muqaddimah was to introduce nothing less than the "history of the universe." The birth of history that Ibn Khaldun imagined, however, simply shifted the borders between myth and history, literally so, for Ibn Khaldun's perspective was that of a North African, who traveled widely also in Europe and the Middle East. The relation between myth and history to the Mediterranean became even more complex, enveloping all its shores (cf. Lacoste 1984).

Myth needs to be interpreted from literary, religious, and musical standpoints, all of which offer ways of recognizing the historical and anthropological functions of the narrative genres of myth, for example epic. Epic repertories locate history and religion along the Mediterranean littoral. In the Eastern Mediterranean the Pentateuch embodies the central myth of creation, exodus, and settlement in Israel. The mythical representation of Greek Antiquity, too, has an epic form that we know well, namely that of Ulysses's journey in the Iliad and the Odyssey, which, we should not forget, took shape in a musical oral tradition codified by Homer (cf. Lord 1960). The modern epic traditions of the Balkans and Beni Hillal traditions of North Africa represent the transformations of these areas through centuries of interaction with Islam (Slyomovics 1987). The Maggio tradition of Italy (Magrini 1992) and the Cid epics of Spain bring us full circle in a mythological representation of theSouthern and Western Mediterranean.

Myth is not, of course, history in the strictest sense, which is precisely why it draws our attention to a musical anthropology of the Mediterranean. According to Claude Lévi-Strauss and other scholars who have theorized myth, myth contrasts with history because it represents a timeless world. Lévi-Strauss would say that time is "cold" in a mythological world, whereas it is "hot" in a world driven by history (e.g., Lévi-Strauss 1969). The timelessness of the mythological world, to borrow from Mircea Eliade, contrasts with the timeboundedness of an historical world. Unlike Lévi-Strauss, Eliade stresses that mythological and historical worlds are connected, in fact, that humans pass between timeboundedness and timelessness during ritual and other religious practices. Among the most important of these passages are sacred journeys. In this essay, it will be one of the most historically powerful sacred journeys, diaspora, that focuses my remarks on a musical anthropology of the Mediterranean. I also draw a metaphorical parallel between those who go on the sacred journeys of the Mediterranean and the "musicians of the Mediterranean" in this edition of Ethnomusicology OnLine.

Quite unlike most discussions of myth, which regard it as a temporal framework for a distant, unrecoverable past, I reflect upon myth here as a modern phenomenon, not least because of its persistence in an anthropology of modernity. In particular, I concentrate on one modern and powerful metaphor of Mediterranean myth: diaspora. Diaspora provides one of the root metaphors for the oldest myths of the Mediterranean, for example, the biblical diasporas in Egypt and Babylon. The Jewish diaspora after the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 C.E. remains, in fact, the most powerful of all historical metaphors for diaspora. Diaspora is, therefore, a root metaphor for the imagination of Mediterranean history.

Modern diasporas are no less present in the Mediterranean, and music is no less powerful as a narrative voice for these modern diasporas. In the Early Modern Era, the Sephardic Diaspora and the Discovery of the New World reformulated biblical myths in complex ways, remapping them onto the entire world. In the twentieth century, the founding of the modern State of Israel opened a modern history for biblical myth. Modern myths provide the motivations for Mediterranean musicians to immigrate to North America, such as those whose lives Karl Signell documents. We stand now on the postmodern threshold to the twenty-first century as the myths of postmodernity take shape, for example as the labor forces from the Mediterranean, from Morocco in the west and Turkey in the east, fuel the industrialization and transformation of the New Europe, and overlay the landscape of that Europe with the musics of the Muslim Mediterranean, just as the musics of the Jewish Mediterranean were dispersed across the landscape of the Old Europe (cf. Mandel 1990 and Lortat-Jacob 1995).”

Source: https://www.umbc.edu/eol/3/bohlman/bohlman1.htm

Philip Bohlman “Music, Myth, and History in the Mediterranean:

Diaspora and the Return to Modernity”

Philip V. Bohlman teaches ethnomusicology at the University of Chicago, where he also serves on the Jewish Studies faculty. His research often investigates the relations between music and religion, with current projects including studies of music and pilgrimage, and the histories of Jewish music in Central and Eastern Europe.

His most recent book is Central European Folk Music: An Annotated Bibliography of the Sources in German (Garland 1996). He is currently completing work on "J�dische Volksmusik": Eine Geistesgeschichte Mitteleuropas (Peter Lang). Bohlman is Coeditor of "Chicago Studies in Ethnomusicology" (University of Chicago Press) and General Editor of "Recent Researches in the Oral Traditions of Music" (A-R Editions).

Source: https://www.umbc.edu/eol/3/bohlman/bio.htm

0 notes

Text

A landmark for gay cinema – and one of the best Jewish films in years

Since its premiere at the Sundance Film Festival this January, director Luca Guadagnino’s film Call Me by Your Name has had audiences swooning and sobbing with its poignant look at coming of age.

Based on André Aciman’s novel, it stars Timothée Chalamet as Elio, a 17-year-old American living abroad in Italy. His father, played by Michael Stuhlbarg, is a professor of archaeology, and each summer hosts a different, brilliant student. This year, as the swallows chirp and the apricots ripen on the vine, the guest is Oliver, played by the athletic, self-assured and mouth-wateringly handsome Armie Hammer. Elio and Oliver will fall in love and, as the long Tuscan days turn to nights, you will fall in love with them falling in love.

Much has been said about this film’s gorgeous swirl and striking ability to capture first love as well as the self-doubt that comes with coming out. As critic Richard Lawson put it in Vanity Fair, “Elio must act as if nothing is happening while everything is happening”.

This is a landmark in gay cinema, for somewhat paradoxical reasons. It can absolutely (and will absolutely) be enjoyed by anyone, not just gay people, as it speaks so warmly and beautifully to universal truths. But this is not a situation where the two leads “just happen to be gay”. Being gay, and that includes intimate moments, is essential to the specificity of the story. Call Me by Your Name can only reach everyone by being about two specific people.

I would never in a million years want to take this film “away” from the gay community. But there is an aspect to it that has been less discussed. This movie is extremely Jewish and, with its compassion, honesty, zeal and intelligence, extremely Good For The Jews.

Author André Aciman is an Egyptian-born Jew, young Manhattanite Timothy Chalamet is Jewish on his mother’s side, Stuhlbarg grew up Jewish in California before coming to New York to study and Hammer is, in fact, a direct descendant of industrialist/philanthropist Armand Hammer. More importantly, all their characters are Jewish, and the type of Jew that we know in life but hardly ever see in films.

Stuhlbarg’s professor is a welcoming bon vivant, but not in a loud l’chaim-clinking Topol kind of way. He is an intellectual whose greatest vice is trying to trip up a student on a rare etymological point. He, his wife and son all toggle between three languages (Italian, French and English) and discuss classical art and aesthetics and history.

Elio’s hobbies include playing Bach melodies in the style of Liszt and then in the style of Busoni tweaking Liszt’s changes. (Oliver looks on unimpressed: just play it like Bach.)

I should point out this is set in the 1980s, when young minds weren’t poisoned by YouTube, but it’s also a Platonic ideal of the “enriched millieu” – the perhaps stereotypical view of Jewish cultural emphasis on education. People of the Book, as they say. This is a movie where Armie Hammer lays topless as he tries to parse the phrases of Heidegger (Heidegger!) before dunking himself in an old stone pool.

These are Jews who probably know the Pentateuch backward and forward but are ultimately secular. Indeed, there is no Judaica to be found in their Italian villa, which is why Oliver’s star of David necklace is such a standout. (Well, that and because is lays against his chest hair).

“I know what it is to be the odd Jew out”, Oliver assures the more timid Elio. Oliver comes from New England, and Elio’s family are the only Jews in this collection of sleepy Italian towns.

“My mother says we are Jews of discretion”, Elio says later, when Oliver is playing with and cracking his toes. “Where did you learn to do that?” Elio asks. “My bubbe taught me”, the older boy says.

As with any coming out story, there is worry about what the parents will think. This open, honest, Jewish family is not reflective of many films you’ve seen before. Elio discusses the near-loss of his virginity with a local girl with a charming, healthy frankness. (The specifics of the plot I’ll leave out, but this young woman plays an important part in the eventual true romance). The film ends with not just one of the great, understanding parenting monologues, but one of the great monologues in cinema.

Michael Stuhlbarg, who, naturally, “knew” all along, talks around his son’s romance with his protege. He gives him space to come to him for advice, or to let it alone, but offers some heartbreaking advice: “How you live your life is your business. Remember, our hearts and our bodies are given to us only once. And before you know it, your heart is worn out, and, as for your body, there comes a point when no one looks at it, much less wants to come near it”.

It’s the menschiest thing you’ll ever hear, but salted with just the right amount honest, fatalist humor.

We can’t bring back the endless summers of youth, but we can recall their spirit. Call Me by Your Name can be considered an idealistic film, but that’s only natural for something about young people experiencing something wonderful for the first time. It prompts us in the audience – and us as Jews – to live up to our ideal selves.

JORDAN HOFFMAN | THE TIMES OF ISRAEL | 10 Dec 2017

#Call Me by Your Name#Guadagnino#timothee chalamet#armie hammer#andre aciman#james ivory#reviews#CMBYN#Chiamami col tuo nome#Elio#Oliver#Perlman

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

#TodayInHistory - January 26

#TodayInHistory – January 26

January 26 – Some important events on this day

1482 👉🏼 “Pentateuch” the Jewish Bible is 1st printed as a book in Bologna, Italy

1531 👉🏼 Lisbon hit by Earthquake; about 30,000 die

1564 👉🏼 The Council of Trent issued its conclusions in the Tridentinum, establishing a distinction between Roman Catholicism and Protestantism

1700 👉🏼 The magnitude 8.7-9.2 Cascadia earthquake took place off the west…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Link

ISAAC BASHEVIS SINGER — the famed Yiddish writer who in 1935 moved from Warsaw to New York and in 1978 received the Nobel Prize for Literature as an American-Jewish author — made his first trip to Israel in the fall of 1955, arriving just after Yom Kippur and leaving about two months later. His relationship to Israel was complicated to say the least. He had been born into a strictly religious family of rabbis and rebetzins in Poland, for whom the land of Israel was the holiest of religious symbols. But he also lived a secular life in 1920s Warsaw, witnessing Zionism overtake Jewish Enlightenment and Bundism as a viable 20th-century political force. In more personal terms, Israel was also the place to which his son, Israel Zamir, had been brought by his mother, Runya Pontsch, in 1938, growing up in part on Kibbutz Beit Alpha and later fighting in the War of Independence. Yet Singer had always avoided every kind of -ism — from Zionism to communism — and so his perspective on the young state of Israel was largely free of the ideology and dogmatism that was prevalent during the country’s early days.

During his trip, Singer published several articles per week in the Yiddish daily Forverts, recording his visit. While these articles sometimes read like touristic travelogues, they reflect Singer’s complex relation to the land of Israel, as both an idea and a place. Israel had been in Singer’s consciousness since his youngest days as a boy growing up in religious surroundings, and it made its way into his work, including some of his earliest fiction, which was published in Hebrew. When he was still living in Warsaw, Singer wrote a novella titled The Way Back (1928) about a young man full of the Zionist dream who travels to the Land of Israel and returns five years later after suffering hunger, malaria, and poverty. In 1948, just a week before the state of Israel was declared, he ended The Family Moskat with several characters leaving Warsaw and moving to pursue the Zionist dream. In 1955, just weeks before his trip, he published an episode of In My Father’s Court (1956) titled “To the Land of Israel,” about a local tinsmith who moves his family to the Holy Land, then returns disappointed to Warsaw, but then, despite everything, goes back. In his memoirs, Singer writes that he considered moving to British Mandate Palestine in the mid-1920s, and in The Certificate (1967), he fictionalizes this in a tale that ends with the protagonist instead going back to his shtetl. As late as 1938, in a letter to Runya sent from New York, he was still fantasizing about the idea: “My plan is this: as soon as I have least resources, and I hope they come together quickly, I will travel to Palestine.” But by mid-1939, these dreams seem to pass into a different view on reality: “For me, in the meantime, getting a visa to Palestine is impossible.” For Singer, it seems, Israel remained, in both the symbolic and literal sense, the road not taken.

And yet, in late 1955, Singer made his first trip to Israel, accompanied by his wife Alma, on a ship called Artsa traveling from Marseille via Naples to the port of Haifa — not as a religious child or an idealistic young man but as a middle-aged Yiddish writer who was beginning to make his name on the American literary landscape. And his journalistic assignment was to capture the trip in short articles that would give Yiddish readers across the United States a sense of what the young state of Israel was like. His son, Zamir, was in New York working as a Shomer Ha’Tsair representative, and both letters and memoirs suggest there was no question of his meeting Runya. Singer was left to his own devices — traveling throughout Israel with Alma, but writing about it as if he were there all by himself.

¤

Singer’s peculiar perspective — with such complex personal history behind it, and such pragmatic goals before it — gives his writing from Israel its unique tone. It is always concerned with the big picture yet remains focused on the small picture. This is evident from the first moments of his trip, even while he was still on the ship. “I think about Rabbi Yehuda Halevi and the sacrifices he made to set his eyes on the Holy Land,” he writes while the ship sails from France to Italy. “I think about the first pioneers, the first builders of the New Yishuv […] How is it that there’s no trace of any of this on this ship? Are Jews no longer devoted with heart and soul to the idea of the Land of Israel?” Singer is looking for proof of the spiritual greatness that the Land of Israel represents, and he wants to see it in the people on board with him — but he soon comes to understand that Israel is not a place of imagination, it’s a place that actually exists. “No, things are not all that bad,” he writes. “The fire is there, but is hidden […] The Land of Israel has become a reality, part of everyday life.”

He begins a keen description of reality still on board the ship. Observing the younger passengers, he describes a now familiar picture: “The young men and women who sit under my window on folding lounge chairs have possibly fought in the war against the Arabs. Tomorrow they may be sent to Gaza or another strategically significant location. But at the moment they want what any other modern young people want: to have a good time.” He identifies, before even arriving on shore, the constant negotiation in Israeli society between war and freedom.

On the ship, he also identifies cultural tensions between Ashkenazim and Sephardim, religious and secular:

There’s a tiny shul here with a holy ark and a few prayer books lying around. But the only people praying there are Sephardic Jews who are traveling in third class or in the dormitories […] It will soon be Yom Kippur, but the ship’s “Chaplain” […] told me there are only three Ashkenazim who want to pray in a quorum.

Singer becomes attached to this group of Sephardi Jews from Tunisia, following them with his eyes and ears:

On Friday evening I wanted to attend prayers. It was still daytime. I went into the little shul and there I saw a kiddush cup with a little wine left inside, and a few pieces of challah laying nearby. It seemed that they had already brought in the Sabbath. The Tunisian Jews have to eat at 6 o’clock and need to pray first.

Later, he goes again, and sees a man praying in a way that moves him. “There, in that little shul, I first came upon the spirituality for which I searched. There, among those Jews, it felt like shivat tsion — the Return to Zion.” He later watches the young Tunisian Jewish women with their head coverings down on the lower deck.

I look for the commonalities between me and them. It seems to me that they, too, look at me to see what connects us. From the standpoint of our bodies, we are built as differently as two people can be […] But as far as one may be from the other, the roots are the same […] There, in Tunisia, they looked Jewish, and for this they were persecuted.

What binds Jews from different corners of the world together, it seems, is their separate but shared experience of difference, even in their native countries.

Singer reports that the mood changes in Naples, where several hundred more passengers board the ship. Now there’s also singing and yelling — the fire he was looking for. But during this part of the trip he also meets a German-Jewish couple who complain bitterly about their life in the Yishuv.

The husband said that letting the Oriental Jews in without any selection, without any inspection, had completely thrown off the moral balance of the country […] The wife went even further than the husband. She said that, no matter how much she wished, she could not stand the company of Polish and Russian Jews. She was accustomed to European (German) culture […] she could not stand the Eastern European Jews.

Singer pushes back against her snobbery. “‘You know,’ I asked her, ‘that your so-called European culture slaughtered 6 million Jews?’” And she responds: “I know everything. But…”

Before he even sets foot in Israel, Singer identifies some of the social difficulties that its citizens face. “It’s hard, very hard, to bring together and bind together a people who are as far from each other as east from west […] Holding the Modern Jew together means holding together powers that can at each moment come apart. Herein lies the problem of the Yishuv.” This observation is less a criticism than a diagnosis. No matter how much binds Jews in Israel — the roots we all share — we have to, at the same time, navigate our differences. In this, Singer acknowledges one of the greatest challenges of a Jewish state.

What seems to really strike Singer when he finally arrives in Israel is the reality that, while built on modern organizational foundations established since the mid-19th century, the country appears as if it had been constructed out of nothing. His access to this reality is, funnily enough, street signs:

Israel is a new country, there’s a mixed population, for the most part newcomers, and they need information at every step. Signs in Hebrew — and often also in English — show you everything you need to know. […] The signs don’t just offer information, they’re also full of associations. . . Every street is named for someone who played a role in Jewish history or culture. Rabbi Yehuda Halevi, Ibn Gvirol, J. L. Gordon, Mendele, Sholem Aleichem, Peretz, Bialik, Pinsker, Herzl, Frishman, Zeitlin are all part of this place’s geography. Words from the Pentateuch, from the Mishnah, from the commentaries, from the Gemara, from the Zohar, from books of the Jewish Enlightenment – are used for all kinds of commercial, industrial, and political slogans.

What Singer seems to like about this is that it makes even less sympathetic Jews have to face their connection to Jewish history and culture. “The German Jew who lives here might be, in his heart, a bit of a snob […] but his address is: Sholem Aleichem Street. And he must — ten times or a hundred times a day — repeat this very same name.” In these signs, Singer sees something that goes much deeper into the reality and paradox of Jewish identity: its apparent inescapability.

Singer quickly connects these prosaic thoughts with the very core of Jewish faith: “As it once did at Mount Sinai, Jewish culture — in the best sense of the word — has brought itself down upon the Jews of Israel and called to them: you must take me on, you can no longer ignore me, you can no longer hide me along with yourself.” In Israel, spirit and religion are not ephemeral feelings; they are viscerally present.

¤

On his way from the port in Haifa to Tel Aviv, Singer stops at a Ma’abara, or transit camp, set up to house hundreds of thousands of Jewish immigrants and refugees, mainly recent arrivals from Arabic-speaking countries across North Africa and the Middle East. “It’s true that the little houses are far from comfortable,” he writes.

This is a camp of poor people, those who have not yet integrated into the Yishuv. But the place is ruled by a spirit of freedom and Jewish hopefulness. Sephardic Jews with long sidelocks walk around in turbans, linen robes, sandals, ritual fringes. There’s a little market where they sell tomatoes, pomegranates, grapes, bread, buns, cheese […] It’s true that there are no baths here or other such comforts. But the writer of these lines and our readers were also not all raised in houses with baths.

The poverty in these camps does not alienate someone like Singer, who himself grew up in poverty.

Singer recognizes both the desperation and the potential in these refugee camps:

The Jews here look both hopeful and angry. They have plenty of complaints for the leaders of Israel. But they’re busy with their own lives. Someone is thinking about them in the Jewish ministries. Their children study in Jewish schools. They are already part of the people. They will themselves soon sit in offices, speak in the Knesset.

It is as if Singer could see the long and difficult road ahead of someone like Yossi Yona — the academic scholar and Labor Party politician who was born in the Ma’abara of Kiryat Ata and now sits in the Knesset.

At every step, Singer reflects on his relationship to the reality of being in the modern Jewish state: “Moses, our great teacher, did not merit coming here. Herzl did not have the luck to see his dream realized. But I, who laid not a single finger toward building this state, walk around like I own the place.” His focus, at this early point of the trip, is mainly on the unbelievability of Jewish sovereignty. The question of its sustainability — the role of Palestinian Arabs within this project and the constant threat of war — is still to come. In the meantime, Singer basks in what he sees as the Jewishness around him: the history and culture with which he grew up, persecuted for hundreds of years in Eastern Europe, had finally risen and come to reign over an entire land and people. This unimaginable reality leads him to focus not on Israel’s relations with other people or states — its Arab population, the Palestinian refugees, the enemy nations across its borders — but rather on Israel’s national relationship to itself.

“There cannot be a Kibbutz Galuyot — an ingathering of the exiles — without the highest tolerance,” he warns.

Everyone in this place has to be accepted: the most orthodox Jews and the greatest apostates; the blonde and the dark-haired, the ingenue and the pioneeress, the Russian baryshnya, the American miss, and the French mademoiselle, the rabbinical Jewish daughters, and the wives that wear wigs with silk bands, and even the German Jewish fraulein who complains that Jews stink and that she misses the mortal danger of German culture.

This sentence is perhaps difficult to swallow today, and yet the divisions in Israeli society have only grown since Singer wrote this over 60 years ago. He could not have known the place that the Ultra-Orthodox would occupy in today’s Israel, or the great split in public opinion that would develop over territories occupied in the Six-Day War, or the strong shift to the right that the Israeli population has exhibited since the late 1970s. What he saw before him were Jews from different backgrounds, in different attire, with different beliefs and convictions, all living together in a single country. He immediately realized that, without tolerance for one another, the project would be doomed from the beginning.

It is worth scrutinizing this thought. Israeli society must deal fairly with others, but Israelis must also find a way of dealing fairly with each other. Respect for the unfamiliar begins with respect for the familiar — with the ability to see oneself in other people, and others in oneself. Where anger, destruction, and violence rule, they do so both inwardly and outwardly. If Jews cannot be good to Jews, this seems to suggest, how could they ever be good to anyone else?

¤

In his writing on Israel, Singer also constantly contemplates religious history and personal experience. In this spirit, he writes: “Ahavat Israel, loving fellow Jews […] has a mystical significance.” Singer cannot avoid associating the place with his own religious education as a child — being a Jew in Israel also means, for him, being constantly in touch with the myriad of Jewish texts he has internalized.

Standing at the foot of Mount Gilboa, he writes:

This was where Saul fell, this was where the last act of a divine drama was played out. Not far from here the Witch of Endor, the spiritist of the past, bewitched Samuel the Prophet. I look at this very same rocky hump which was seen by the first Jewish king, who had made the first big Jewish mistake: underestimating the powers and evil of Amalek.

Looking out from the balcony of a hotel in Safed a few days later, likely at Mount Meron, he writes: “This is not a mountain for tourists, or runaway fugitives, but for Kabbalists, who made their accounting with our little world. There, through those mountains, one can cross from this world into the world to come.” He continues:

At this very mountain gazed the holy Ari [Rabbi Isaac Luria], Rabbi Chaim Vital, the Baal-Ha’Kharedim [Rabbi Elazar ben Moshe Azikri], and the author of Lekha Dodi [Rabbi Shlomo Halevi Alkabetz]. Here, in this place, an angel showed itself each night to Rabbi Joseph Karo [author of the Shulkhan Arukh] and conducted nightly conversations with him. The greatest redemption-seekers looked out from this place for the Messiah. Here, in a tent or a sukkah, deeply gentle souls dreamed about a world of peace and a humanity with one purpose: to worship God, to become absorbed in the divine spirit, in a spirit of holiness, of beauty. This is where the Ari [Rabbi Isaac Luria] composed his Sabbath poetry, which was full of divine eroticism, and which had a depth with no equal in the poetry of the world.

In visiting Mount Zion, he similarly finds himself transported to a mystical past:

I look into a cave where you can supposedly find King David’s grave. I walk on small stone steps that lead to a room where, according to Christian legend, Jesus ate his last meal. […] This is another sort of antiquity than in other places. The antiquity here smells — it seems to me — of the Temple Mount, of Torah, of scrolls, of prophecy.

And elsewhere: “On this very hill there started a spiritual experiment that continues to this very day. In this place, a people tried to lead a divine life on earth. From here there will one day shine a light to the people of the world and to our own people.” And it seems that his sense of moral choice, raised by the danger of Jordanian soldiers looking down on him from the wall above, also finds expression: “What is today a desert could tomorrow become a town, and what today is a town could tomorrow become a desert. It all depends on our actions, not on bricks, stones, or strategies.” Walking through the Valley of Hinom, the historical site of Gehenna which he finds covered in greenery, he even jokes: “If the real Gehenna looked anything like this, sinning wouldn’t be such a terrible thing.” The images and symbolism of the Bible are truly present at every step.

The land as a whole has a strong effect on Singer, but his trip to Safed, as someone raised on the Kabbalah, made an especially strong impression. “I can say that here, for the first time, I gave myself over to the sense that I was in the Land of Israel.” These are moments when Singer’s sense of criticism, doubt, heresy, intellectuality, and all the other complex impulses that find their way into his fiction, takes second place to a deep sense of piety and faith. This is no less powerful in his work, where his characters achieve it rarely or partially, and, even when they do, with great difficulty.

Singer doesn’t come to this spiritual journal easily either. In Safed, he also encounters the reality of the new state. There he meets a Jew who speaks Galician Yiddish, but who is part of generations of Safed residents. “The Arabs of the past were good to Jews,” Singer quotes the man.

They let the Jewish merchants earn a living. When you bought grapes from them, they would add an extra bunch. Another man said: everything was good until the English came. They incited the Arabs against the Jews. Another man said: Well, may there soon be peace. This is atkhalta d’geula — the beginning of the redemption.

Among the mysticism and magic of the place are politics, colonialism, and history.

Later, in Tel Aviv, Singer visits a courthouse. In the first courtroom, Singer sees “a young man from Iraq who had allegedly falsified his documents in order not to have to go to the army.��� In the next courtroom, a Greek Orthodox priest is taking the stand, speaking Arabic, which is being interpreted into Hebrew:

On the bench sit several Arabs […] They are suing to get back their houses, which the state of Israel took over after the Jewish-Arab War […] Jews have taken over their homes. But now the Arabs have decided to sue for their property back. They no longer have any documents, but they are bringing witnesses to testify that the houses that they own belong to them. The old Greek priest is one of these witnesses.

In a third courtroom, Singer observes a Yemenite Jewish thief who is accused of assaulting the police, but who claims the police actually assaulted him. The young thief ends up being acquitted. Ashkenazi Jews are conspicuously absent from this entire visit to the courthouse.

Singer soon observes other forms of suffering and injustice. On the southern side of the city, it is even more evident:

Here in Jaffa you can see that there was a war in this country. Tens and possibly hundreds of houses are shot up, ruined […] The majority of Arabs fled Jaffa, and in the Arab apartments live Jews from Yemen, Iraq, Morocco, Tunisia. They live in single rooms almost without furniture. They cook on portable burners. […] The situation in Israel is generally difficult, but in Jaffa everything is laid bare — all the poverty, all the difficulty.

Singer is, as that passage and most of his writing suggests, almost singularly focused on the new Jewish population of the state. The former Arab tenants of these apartment buildings remain invisible to him.

Singer is so utterly focused on the creation of the new state and the new Jewish settlers, that even when faced with the Arabic population, he barely acknowledges them. He writes, “In Beer Sheva, more than in other cities, you feel that you’re among Arabs. […] Arabs are not black but also not white. […] What sticks out to the eye most is the great amount of clothing that Arabs wear on the hottest of days. […] Rarely do you see Arab women on the street.” What is striking is the degree to which Singer sees Israel’s Arab population as an impenetrable other. He seeks no interaction with them, no attempt to understand them. He puts it plainly in another text: he just wants them to let Jews live their lives. Later, when he visits Jaffa, he writes: “As long as the Arabs leave well alone, there will be building-fever here like in Tel Aviv and in the rest of the country.” This is a difficult opinion to hear, but it has actually come to bear. Jaffa, more than 60 years later, is now going through a major revolution of gentrifying Jewish construction.

There is no doubt that Singer’s story of Israel is a Jewish story. His writing can deepen our understanding of different kinds of Jewish realities, even if, when it comes to Palestinians, his opinions are thoroughly unexamined and unconsidered. Singer can contribute, however, an interesting perspective on the need for tolerance among different kinds of Jews: Sephardic, Ashkenazi, old world and new. This is especially the case when it comes to modern Jews understanding the mindset of the old world. And it sets out a path for tolerance that can then be extended beyond Israel’s Jewish population.

¤

“I myself want people to speak to me in Hebrew,” Singer writes in one of his earlier articles.

But as soon as anyone hears that my Hebrew sounds foreign, they start speaking to me in Yiddish, and so the result is that I mostly speak Yiddish. People here speak Yiddish at every step. […] Even Sephardim learn some Yiddish in the army. It’s also in fashion for Hebraists to throw in Yiddish words to be cute.

Over and over, Singer’s wishes and imaginings of this place bump up against the reality. Everyday life — the texture of daily reality — pushes back against the big questions that seem to always be at hand. “A good cup of coffee is rare,” Singer writes. “You can get a good black coffee, but if you like a cup of coffee with cream like in New York, you will mostly be disappointed.” He also points out that “yogurt is very popular, as is a sort of sour cream called lebenya.” And another thing: “You see balconies everywhere. People sit on their balconies, eat on their balconies, entertain guests.” He points out that there are many elegant people on the streets but that well-dressed people are a rare sight. He even spends a paragraph on trisim, the heavy shades that are meant to keep out the Mediterranean sun. No matter the history, there is always real life to negotiate.

A major part of this real life, as Singer points out, is the constant threat of war. “The enemy can attack from all sides: from north, from south, from east,” Singer writes, reflecting on his trip up to Kibbutz Beit Alpha. “But the visitor in Israel is infected with a mysterious bravery that belongs to all Jews in Israel. A kind of courage that’s difficult to explain.” On Tel Aviv, he writes: “The enemy is not far. If you in New York were as close to the enemy as we are here, you’d shiver and shake and try to run away. But in the streets where I find myself there reigns a strange quiet, a serenity having something to do with the physical and spiritual atmosphere.” In Jerusalem, he again has the same thought: “It’s hard to believe that you’re close, extremely close, to the enemy.” And on the way up to Mount Zion, he again points to the mysterious courage: “I’m no hero, but I have no fear. I’d would say that Israel is infected with bravery. In any other country, this kind of walk, next to the very border of the enemy, would arouse fear in me.” Violence is a reality that Israelis face at all times — and there is no doubt that over the decades it has affected and perhaps also infected our society, both how Israelis treat non-Jews and how we treat each other. But the fact remains that, to live here, we all need an inherent kind of bravery, toward outside threats no less than our own neighbors.

¤

In one of his articles, in which Singer considers all the people he met during his trip, he tells the story of Benjamin Warszawiak, an old friend from Bilgoraj who moved to Israel. Benjamin found life difficult, moved for a time to South America, but eventually came back to live out his life working on a kibbutz. His story is sad, and yet Singer sees a redemptive aspect to this man’s life — that there is nowhere else but the Jewish state for him to live. “You don’t have to necessarily be an extraordinary person to have deep spiritual needs,” he reflects. “Simple people often sacrifice their personal happiness to improve their spiritual atmosphere. Israel is full of such people, and you find them especially in the kibbutzim. I can say that almost all of the kibbutzniks are in their own way idealists.”

Ultimately, Singer suggests, the paradox of Jewish life in Israel lies in the heart of the Jews who continue to make Israel their home. “Faith in this place, like the Sabbath, is somewhat automatic and instinctual too,” he writes. “The mouth denies, but the heart believes. How could people live here otherwise?”

¤

David Stromberg is a writer, translator, and literary scholar based in Jerusalem.

The post Faith in Place: Isaac Bashevis Singer in Israel appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books https://ift.tt/2Jv7tXv

via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

117 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A bit of January 26th history…

1482 - “Pentateuch”, the Jewish Bible, is printed as a book in Italy

1500 - Vicente Pinzon becomes 1st European to set foot in Brazil

1564 - The Council of Trent issues it’s conclusions in the Tridentinum, establishing a distinction between Roman Catholicism and Protestantism

1905 - World’s largest diamond, 3,106 carat Cullinan, is found in South Africa

1926 - John Baird gives 1st public demonstration of television in his lab in London (pictured)

1950 - Constitution of independent India comes into effect

0 notes

Photo

A bit of January 26th history...

1482 - “Pentateuch”, the Jewish Bible, is printed as a book in Italy

1500 - Vicente Pinzon becomes 1st European to set foot in Brazil

1564 - The Council of Trent issues it’s conclusions in the Tridentinum, establishing a distinction between Roman Catholicism and Protestantism

1905 - World’s largest diamond, 3,106 carat Cullinan, is found in South Africa

1926 - John Baird gives 1st public demonstration of television in his lab in London (pictured)

1950 - Constitution of independent India comes into effect

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

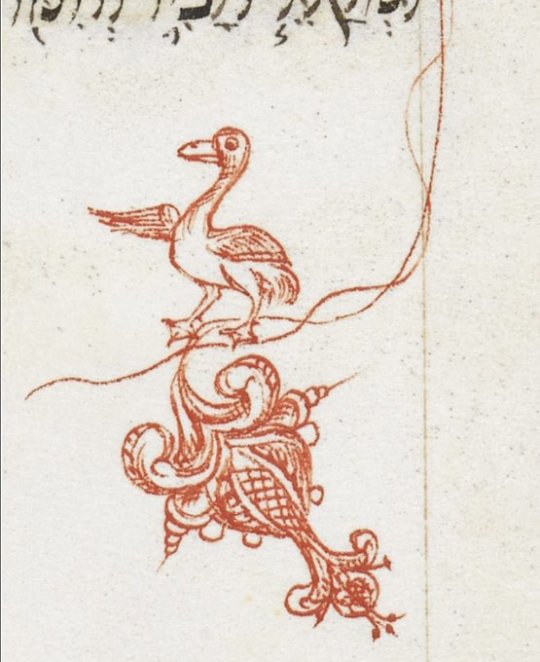

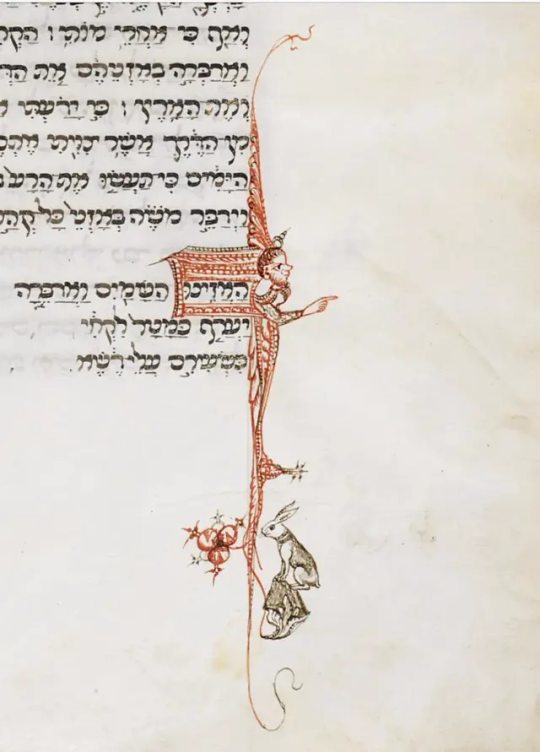

#Torah Portion Ha'azinu (הַאֲזִינוּ)#ParashahPictures#farewell song of Moses#Pentateuch; 1441 CE-1467 CE; Italy#🐇

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

#TodayInHistory - January 26

#TodayInHistory – January 26

January 26 – Some important events on this day

1482 👉🏼 “Pentateuch” the Jewish Bible is 1st printed as a book in Bologna, Italy

1531 👉🏼 Lisbon hit by Earthquake; about 30,000 die

1564 👉🏼 The Council of Trent issued its conclusions in the Tridentinum, establishing a distinction between Roman Catholicism and Protestantism

1700 👉🏼 The magnitude 8.7-9.2 Cascadia earthquake took place off the west…

View On WordPress

0 notes