#Nevi'im

Text

Job, Five Scrolls, Daniel, and Ezra-Nehemiah with commentaries, [Naples: Joseph ben Jacob Ashkenazi Gunzenhauser, 1487]

In about 1486, a German Jewish immigrant named Joseph Gunzenhauser (d. 1490) entered into a printing partnership in Naples, a centre of the contemporary book trade. The following year, his press issued three works in rapid succession: Psalms with the commentary of Rabbi David Kimhi (Radak), Proverbs with the commentary of Rabbi Immanuel ben Solomon of Rome, and the present title, containing the rest of the books of the Ketuvim with one commentary each (some printed here for the first time): Job with that of Rabbi Levi ben Gerson (Ralbag or Gersonides), Lamentations with that of Rabbi Joseph Kara, and the Song of Songs, Ruth, Ecclesiastes, Esther, Daniel, Ezra-Nehemiah, and I-II Chronicles with that of (or attributed to) Rashi. In doing so, Gunzenhauser brought to a close a process, set in motion in Bologna in 1482 and continued in Soncino in 1486, of printing each book of the Hebrew Bible with at least one commentary.

#jumblr#judaism#printed books#italy#joseph ben jacob ashkenazi gunzenhauser#joseph gunzenhauser#nevi'im#ketuvim#myposts

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

burakhovsky ficwriting so bizarre it got you reading Book Of Daniel (from. the Old Testament / Prophetic Books / Tanakh / Ketuvim) for material

#raised orthodox dankovsky lore grows. i do think he was named after him because St Daniel is a major prophet in christianity#but not in judaism even though Book of Daniel appears in the Tanakh. since it does not appear in the Nevi'im but in the Ketuvim. and etc#everything is about it except it itself which is about things i shan't mention (writing diaries)

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

cultural christians when they find out that the tanakh (torah-nevi'im-ketuvim), the Jewish holy book, which was later appropriated as the "old testament" is actually an Jewish-centred account of early Jewish history and Jewish peoplehood, comprised of a a mix of myth with real historical events that can be verified using extra-textual sources

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

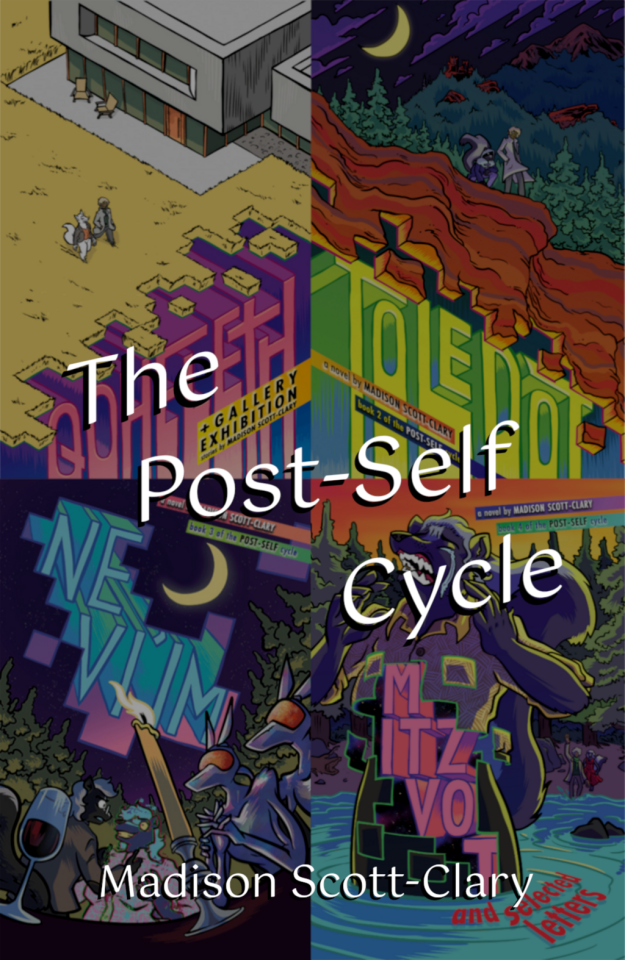

Did you know that I write a lot about memory, skunks, uploading consciousness, political maneuvering, skunks, aliens, skunks, queerness, identity, emotions, and skunks? It's true! I'm very proud of them. You can read books best described as

Given the chance to live forever in a world not built for death, what do you do?

Given the inability to forget—all your joys and sorrows, all your foundational memories and traumas—how do you cope?

Given the ability to create a full copy of yourself—down to every single one of those memories—to do as they will, to individuate and live out their own forever lives, or merge back down and meld their memories with your own, what paths do you take?

and

If I had a nickel for every time I accidentally wrote something with heavy plural undertones that I hadn't intended but nonetheless made me doubt my identity, I'd have two nickels! Which isn't a lot, but it is weird that it happened twice.

The Post-Self Cycle is a tetralogy of meta-furry¹, gender-weird sci-fi books. From the very beginning of the consensual dream of the System, the members of the Ode clade, all forks from the same core personality, have dealt with fear each in their own way. Do they search for greater ways to control their lives? Do they hunt for yet deeper emotional connection? Do they hone their art to the finest point?

From roots in political turmoil to the building of a new society, the story is there to be found, and the Bălan clade is there to tell it.

Digital versions come with illustrations from five artists — Iris Jay, Jade Laclede, Floe, CadmiumTea, and johnny a.

Available as paperbacks, ebooks, and free to read in the browser. Omnibus ebook and illustrated hardcovers coming soon!

Book I — Qoheleth

"All artists search. I search for stories, in this post-self age. What happens when you can no longer call yourself an individual, when you have split your sense of self among several instances? How do you react? Do you withdraw into yourself, become a hermit? Do you expand until you lose all sense of identity? Do you fragment? Do you go about it deliberately, or do you let nature and chance take their course?"

With immersive technology at its peak, it's all too easy to get lost. When RJ loses emself in that virtual world, not only must ey find eir way out, but find all the answers ey can along the way.

And, nearly a century on, society still struggles with the ramifications of those answers.

Features the bonus novella Gallery Exhibition: A Love Story.

Madison finds a way to address not only the joys and terrors of integrated simulation technology, but also tackles questions of gender and identity while telling a pretty gripping mystery story in the process.

— Nenekiri Bookwyrm

Book II — Toledot

"I am saying that you trust me — really trust me — and that life in the System is more subtle than I think you know. You let me into your dreams, my dear, and your dreams influence this place as much as, if not more than, your waking mind."

No longer bound to the physical, what lengths should one go to in a virtual world to ensure the continuity of one's existence?

Secession. Launch. Two separations from two societies, two hundred years apart. And through it all, so many parallels run on so many levels that it can be dizzying just keeping up. The more Ioan and Codrin Bălan learn, the more it calls into question the motivations of even those they hold most dear.

Madison Scott-Clary . . . trusts her readers to be able to understand a completely different culture and existence than our own, and makes it compelling to do so.

— Payson R. Harris

Book III — Nevi'im

"Do you know how old I am, Dr. Brahe? I am 222 years old, a fork of an individual who is...who would be 259 years old. I am no longer the True Name of 2124. Even remembering her feels like remembering an old friend. I remember her perfectly, and yet I do not remember how to be earnest. I do not know how to simply be."

The cracks are showing.

Someone picked up on the broadcast from the Dreamer Module and as the powers that be rush to organize a meeting between races, Dr. Tycho Brahe is caught up in a whirlwind of activity. And as always, when the drama goes down, there is Codrin Bălan to witness it.

When faced with eternity in a new kind of digital world, however, old traumas come to roost, and those who were once powerful are brought to their knees

Growth is colliding with memory, and the cracks are showing.

These characters are so well realized, so fleshed out, that I can’t help but to gush about how their interactions with each other inform the central plot of the book.

— Nenekiri Bookwyrm

Book IV — Mitzvot

"To be built to love is to be built to dissolve. It is to be built to unbecome. It is to have the sole purpose of falling apart all in the name of someone else."

Even the grandest of stories can feel small and immediate when it's just one person's life.

One of the most well-known names from one of the most well-known clades on the System, the avatar of political machinations and cool confidence, has been brought low. With help coming only from Ioan Bălan and the most grudging of support from her cocladists, all True Name has left to save herself is the ability to change.

Features the bonus novella Selected Letters.

Mitzvot drills down deeper into the lives of its characters and shows us that between the world-shattering projects that change the very understanding of the System, they’re just people trying to live their lives with love and purpose.

— Nenekiri Bookwyrm

Keep an eye out for Clade, an anthology of short stories from nine authors set in the universe, coming later this year.

----------

¹ That is, about members of the furry subculture rather than just furry characters.

159 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chaverim: Do any of you know of good editions of the full books of Nevi'im and Ketuvim with commentary? I have a JPC Tanakh and an Etz Hayim chumash, but I was realizing this Shabbos that the last time I really studied the later books of the Tanakh was in Sunday school and uhh. I'd love to fix that, lol.

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 1: Joshua 1 // יהושע א

Today, Friday July 7th, 2023, we are beginning an approximately two year journey to read the Prophets (Nevi'im) and Writings (Ketuvim) of the Tanakh. We will be using the OU's podcast shiurim for commentary to guide this study. However, please feel free to add your own sources and commentary in the notes. Please add any thoughts or discussion in reblogs so that it is easier to keep track of the conversation. Toda raba!

(Link to full chapter text on Sefaria)

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

the most repeated metaphor for israel's exile in the nevi'im (prophets) in the tanakh is that of an adulterous woman punished by her husband. basic logic: g-d promised us in exodus that we would live well in the land of israel and be protected by It (g-d), but we were not. our enemies said this showed g-d the god of israel was unable to protect us, but we could not abide this, and counter-claimed that g-d was punishing us for our unfaithfulness and that It had sent the nations to destroy us, and It had the power reestablish us when we had repented. the adultery metaphor is obviously tuned to the psychology of its times and audience, but more foundational and less criticized is the assumption g-d can make such promises, that it's preferable that It determines the actions of third parties in the world, that if It can't, It's worse than worthless, a used tissue, because the only people here who should have free will and the power to exercise it are the jews and g-d.

this question continued through the repeated exiles and genocides of the jews in the next 2,500+ years, but began to become increasingly complicated and ambivalent over time, including with the interpretation in kabbalah that g-d was shattered and exiled alongside us.

look closer.

much post-holocaust theology rests on the existential question of g-d's impotence, for the hebrew bible does not present evidence that g-d is omnipotent.(1)(2)

so look closer at this metaphor, back in its times. play with reversing it:

g-d is not your husband (patriarchal definition) but g-d is also not your spouse, husband, or wife (modern egalitarian definition). g-d is your wife (patriarchal definition).

g-d cannot take you in or cast you out g-d cannot save or feed or clothe you g-d cannot give you land or defend you in battle g-d cannot divorce you even though It/She/They rages It will in Its besotted-mortified-crazed grief and abjection after you are unfaithful.

perhaps g-d can make your life hell from jealous sabotage g-d can drive you mad with lust and longing for It's beauty, as you have done to It. g-d can make your people survive forever through being the catalyst for all your children(writings/cultural handing-down/mitochondria). g-d can commit adultery against you and betray you. but if you die by your enemy's hand, g-d has permission to die in your house, for you will need it and It no longer.

(and many jews think this option is the worst one tho lmao.

'i can excuse being malicious and cruel and unjust or nonexistent, but i draw the line at being not-omnipotent!')

let me rewrite some of the prophets:

I G-d, take a millstone and grind meal now, in exile,

Remove My veil, strip off (My) skirt;

Show My thigh, cross streams,

let My labia(3) be publicly shown, My private parts be seen

So shall Israel shall have vengeance on Me for My lies of kingship [masculine],

For My overthrow by your enemies,

And shall encounter no opposition...(4)

For when showers I could not bring,

And the late rains did not come,

I had the brazenness of a street woman,

I refused to be ashamed.(5)

/

Over You, G-d, we bent(6), saying

'For the number of Her sins, dishevel Her hair,' (7)

Let Your thighs be uncovered,

Your 'heels' violated....(8)

Your shame will be exposed to Your face,

Showing nations Your nakedness,

kingdoms Your labia....(9)

/ or,

My beauty won Me fame among the nations, for it was perfected through the splendor which I set upon you—

But haughty with My beauty and fame, I played the harlot: I lavished My favors on your enemies O Israel....

I sullied My beauty and spread My legs to every passerby(10)—I multiplied My harlotries to anger you.

For I was jealous of your envy of other nations(11), which you loved more than Me

When you bid Me make kings of your children, and cronies of Egypt(12), rather than wrestle Me til dawn

And I despised you, when you wished to be a tyrant,

As they were once tyrants over you.(13)

....the nations put you to the sword, and took away your finery, and Mine,

In exile, because of misery and harsh oppression;

When we settled among the nations you found no rest;

All your pursuers overtake Me now

In the narrow places.(14)

/ or,

Israel, you uncovered your lover's beauty in Egypt;

There Her breasts were squeezed, and there Her nipples were handled.

Her name was G-d, She became yours,

The fierce-wonders and land and laws you desired for-to-live,

She placed wide-with-boasting(15) on Her lips and brought you as dowry.

But She did not give up the whoring She had begun with the corners of the Earth;

For we had lain with Her in Her youth, and we had handled Her virgin nipples and had poured out our lust upon Her.(16)

[....] the Babylonians came, and all the Chaldeans, and all the Assyrians with them, all of them handsome young fellows, governors and prefects, officers and warriors, all of them riding on horseback.

They exposed your god and saw how she could be defiled

We were roused against you, and came upon you, from all around—

/

Further rambling discussion notes and citations:

Marilyn Monroe said, “If they love you that much without knowing you, they can also hate you the same way.” All idealisation is punishing and sadistic.” - jacqueline rose

thoughts on this reversal as something that Reveals -- for the audience i'm writing to it's one that shocks the connotations to something more viscerally s 0 meth1ng/relatable (the way the og was supposed to be for its audience), but more importantly, i'm trying to come up with something more infinitely chewable as a negotiation of fault and interiority-vs-effects, instead of terminating.

but also while my point in rewriting these is about the non-existence of omnipotence, non-existence of omniscience is probably more interesting. because it....reveals.....i guess a parallel to the way ppl talk about Widely Despised Female CharactersTM (both in madonna and whore perfect idealized and evil all-blameful interpretations). as simultaneously incoherently both culpable and agencyless, both agenda-driven and lacking in interiority, threefold responsible: evil for creating the evil of the world, and evil for trying to fix or destroy that evil when she regrets(17) that world, and timelessly still-blamed as evil when she regrets destroying it and admits that she doesn't have the capacity to fix it but promises to never destroy it again(18). (the souring when its clear she's not secretly timelessly omnisciently correct for allowing this evil).

all this entity's choices and preferences are made into a morally-charged one that is a referendum on the moral valence and bestows moral judgment to anyone or anything she likes/doesn’t like or does/doesn’t do. and also those interior feelings, if shown, are open to making her limitlessly blamed for the spurned person’s resulting action. or mysteriously impersonally Morally Right (after those preferences, like liking meat more than grain, are forcibly interpreted as being solely a moral pronouncement that invites and justifies limitless violence and blame)(19). both timelessly nonlinearly unchangingly culpable at each point in a linear sequence of events regardless of what order one shuffles it in, and incapable of having curiosity or ignorances or confusions that make up linear accumulations of knowledge or opinions or back-and-forths that change her mind over time, or that are incomplete without the preexisting elements of the narrative or which have to take place in the context of a dynamic dialogue/tug of war to make sense.

so i think in a similar way to that, but in a way that doesn't...pattern-match....without the pronounflip/husband-wife adultery and shaming flip......people will not think of the full picture of what else entails if one accepts a premise......no allowing for g-d being dumb or irrational or impulsive, or ignorant at earlier periods of time of what consequences will occur later. no allowing It to have the capacity to change Its mind, and therefore no allowing It to make it up to us once the error in thinking or acting has been understood and regretted. no dynamic interiority allowed in It being capricious and poorly-moral or passion-ruled or not having considered what is evil or what isn't, or what is a big deal to humans and what isn't, not omniscient enough to already know this prior to the chance to learn it by observing humans. no considering such a being to be acquiring contradictory ideas over time and It trying to figure out which one should rule in any given moment, struggling with warring impulses and giving into one at one time and another at another time, being stubborn bc It is a person with ideas that contradict too, reaching out in a curiosity or a confusion, putting on an act to try to court and impress and arouse desire in It's mate Israel. eg, people ignoring the implication that a specific method (flood, languages) implies either a limited ability or a specific desire or a specific curiosity, or both (18) (why multiple languages specifically??? why not something way less surmountable if insurmountability was desired? or if timeless omnipotence was available??).

let alone, in some cases the idea of g-d simply being helpless, overcome, raped and despoiled, not omnipotent enough to achieve -- even if It does know what It wishes It could do -- a method that would fix things, stop things.

but apparently a fearsome but vulnerable and morally-heterogenous and linearly evolving/accumulating/learning god with enough raw bursting power do act immorally sometimes, but without omnipotence, is unpalatable. so……idk, the time-collapse of god treatments that mirrors that of misogyny that mirrors that of antisemitism -- no matter what you do or don't, or can or can't, or know or don't know, or think or can't think, it's your fault -- haunts to an un-unseeable extent.

this is all torah/tanakh and jewish thought specific(20), but the bigger issue for me that i have a hard time unseeing after seeing it was like….the classic conception of omnipotence and omniscience is a thought-termination (either as timeless will-always-have-been-morally-right termination, or as infinitely-blamable, uniquely worthy of punishment, betraying anthy-style scapegoat termination, which are just two different sides of the coin).

there is no cognitively nondissonant way to say 'if g-d exists, i am deciding It is shaped in such a way so as to be to blame for everything/should Be Killed/is actively working against our Liberation/must be a concept that is inherently keeping life from snapping back into a happy and suffering-free equilibrium', because if you (like me) are open to the idea of g-d being nonexistent, there is only One excuse for not also being open to the idea of g-d being a non-omnipotent, non-omniscient, dynamic, learning, growing entity, a person who is then subject to whatever limitations a person would have, and also is an-other person whose inner heart, like any other person's you cannot narrow down to the dichotomy of either being the guy you made up in your head, or a deliberate traitor to that guy. It's the same excuse for why a person or group such as the Jews are The Enemy Of All Humanity Who Must Be Killed Or At Least Blamed: laying down one's own interiority as a sentient being, to invent a person who exists to be limitlessly blameable in situations where no one else would be. if you (like me) don't completely believe g-d exists, i suppose we can't hurt It, but i know what it sounds like and who it impacts.

i am much more stung about g-d lying to us -- by claiming we could only be destroyed by Them/our own transgressions. ie., lying by claiming other groups of humans totally didn't have the power to exile and genocide us irrespective of our own behavior -- than by the crime of 'not being omnipotent.' lol. but ofc even this too assumes They did actually lie to us at all, and that a more fitting interpretation of the text (let alone reality) isn't just a folie a deux of wishful thinking on one or both of our parts in this lovers affair.(21)

1: Milazzo, G. Tom. “TO AN IMPOTENT GOD: IMAGES OF DIVINE IMPOTENCE IN HEBREW SCRIPTURE.” Shofar 11, no. 2 (1993): 30–49. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42941804.

2: eg, Elie Wiesel, Night:

"I heard [a man] asking: Where is God now? And I heard a voice within me answer him: ...Here He is—He is hanging here on this gallows."

3: Eslinger, Lyle. “The Infinite in a Finite Organical Perception (Isaiah VI 1-5).” Vetus Testamentum 45, no. 2 (1995): 145–73. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1535129.

4: Isaiah 47:2-3, Ibid

5: Jeremiah 3:3

6: Job 31:10

7: Sotah ritual, see Numbers 5:18

8: Jeremiah 13:22

9: Jeremiah 13:26

10: Ezekiel 16:14-15, 16:25-26

11: 1 Samuel 8:5-20

12: 1 Kings 9:16

13: 2 Samuel 22 throughout, 1 Kings 1-10 throughout

14: Lamentations 1:3

15: Everett Fox translation choice for 1 Samuel 2:1

16: Ezekiel 23 throughout

17: Genesis 6:8, 8:21

18: Genesis 11:6-7

19: Genesis 4:4-6

20: Karasick, Adeena. “Shekhinah: The Speculum That Signs, or ‘The Flaming S/Word That Turn[s] Every Way’ (Genesis 3:24).” Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women’s Studies & Gender Issues, no. 2 (1999): 114–36. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40326491.

21: Milazzo p. 49:

This is the god which cannot raise the dead. This is not a god which transcends the world in which the drama of life and death is lived. This is a god which, having placed its hands around their heart, stands there with this people [.....] This impotent god walked the road to Babylon and stood among the crematoria at Auschwitz.

#long post#judaism#judaism scholarship#j#they the most beautiful#wrote this in. amanic state sorry if it is showing#crack me

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

THEOLOGY

ABRAHAMIC RELIGIONS ->

THE THREE MAJOR ABRAHAMIC RELIGIONS are, in order of appearance, JUDAISM, CHRISTIANITY, and ISLAM, but there are other MINOR RELIGIONS.

■JUDAISM is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the covenant shared between God and Abraham.

The holy scriptures of JUDAISM are called the TANAKH, after the first letters of its three parts in the Jewish tradition. T: TORAH, the Teaching of Moses, the first five books. N: NEVI'IM, the books of the prophets. KH: KETUVIM, for the Writings, which include the psalms and literature for the wise.

ORTHODOX JUDAISM is the belief in a strict interpretation of Jewish law, which should be grounded in the Torah. As such, the revelation given to Moses from God on Mount Sinai is made glorious and just.

CONSERVATIVE JUDAISM is the belief in marriage and membership as a Jew. Other characteristics will include support of the Zionist movement and the rejection of the immutability of the "Torah" and the "Talmud" while still having faith in the eternal truth upon which it is based.

REFORM JUDAISM is the belief of the renewal in our living Covenant with God, the people of Israel, humankind, and the earth by acknowledging the holiness present throughout creation – in ourself, in each other, and in the world at large – through practice that will include reflection, study, worship, ritual, and much more.

■CHRISTIANITY is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centered around the birth, life, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ.

THE BIBLE is the holy scripture of the Christian religion, purporting to tell the history of the Earth from its earliest creation to the spread of Christianity in the first century A.D. Both the Old Testament and the New Testament have undergone changes over the centuries.

□ROMAN CATHOLICISM

Roman catholicism is a branch of Christianity which has its belief about the sacraments, the role of the Bible and tradition, the importance of the Virgin Mary and the saints, and the papacy.

HISTORY OF THE REFORMATION

THE REFORMATION was a reform movement in religious belief that swept through Europe in the 16th century. It caused the creation of a branch of Christianity called PROTESTANTISM, a name used collectively to refer to the many religious groups that separated from the Roman Catholic Church due to their difference in doctrine.

□PROTESTANTISM

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity which will deny the universal authority of the Pope and affirm all of the Reformation principles of justification by faith alone, the priesthood available to any practitioner, and the Bible as the only source of revealed truth.

□QUAKERISM

Quakerism is a branch of Protestantism

Follow your "inner light"

The Bible

Equality for all

God is accessible to everyone

No clergy

No religious ceremonies

No sacraments

LOCATION -> England

WHEN -> 17th Century

Adventism

Anglicanism

Anabaptism

Baptism

Irvingianism

Lutheranism

Methodism

Moravianism

Pentecostalism

Waldensianism

■ISLAM is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion that was revealed to Muhammad, a prophet of Allah, and written down in the Qur'an years later by his followers.

SUNNI

Muhammad did not specifically appoint a successor to lead the Ummah before his death. This sect did, however, approve of the private election of the first companion, Abū Bakr. In addition to the previous mentioned, Umar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb, ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān, and ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib are also accepted as al-Khulafāʾ ur-Rāshidūn. After this, they believe that Muhammad intended that the Muslim community choose a successor, or caliph, by consensus. A practitioner of this sect will base their religion on the Quran and the Sunnah as understood by the majority of the community under the structure of the four schools of thought. These are HANAFI, MALIKI, SHAFI'I and the HANBALI.

SHI'A

Muhammad's family, the Ahl al-Bayt, including all of his descendants, have distinguished spiritual and political authority over the community. It is believed that Alī ibn Abī Ṭālib was the first of these descendants and the rightful successor to Muhammad. As a result, it was rejected that the first three Rāshidūn caliphs have legitimacy.

------------------------------------------

ETHICAL RELIGIONS ->

THE THREE MAJOR ETHICAL RELIGIONS are BUDDHISM, TAOISM, AND CONFUCIANISM.

■BUDDHISM is an ethical religion that was revealed by Siddhartha Gautama for anyone to gain spiritual enlightenment if that person followed the eight-folded path along with a personal commitment to any noble truth given to him/her through the journey of life in order to reach nirvana.

■TAOISM

■CONFUCIANISM

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

How many books are in your Bible?

Somehow I ended up on the Wikipedia page for Biblical canon and now my head hurts so I'm throwing all of you into the rabbit hole with me.

All Christian denominations share the same twenty-seven books of the New Testament: Matthew, Mark, Luke, John, Acts, Romans, 1 and 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Ephesians, Philippians, Colossians, 1 and 2 Thessolonians, 1 and 2 Timothy, Titus, Philemon, Hebrews, James, 1 and 2 Peter, 1 2 and 3 John, Jude, and Revelation. (The Orthodox Tewahedo Church has an additional eight books, but they are not considered part of the Bible itself, just the broader religious canon.)

However, the Old Testament is where it gets complicated.

The Tanakh contains twenty four books divided into three sections: The Torah, the Nevi'im, and the Ketuvim. The Torah contains Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. The Nevi'im contains Joshua, Judges, Samuel, Kings, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuh, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi. The Ketuvim contains Psalms, Proverbs, Job, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, Esther, Daniel, Ezra and Nehemiah, and Chronicles.

The Protestant Old Testament took the canon of the Tanakh, divided some books into two and added another book, making a total of 39 books: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, Ruth, 1 and 2 Samuel, 1 and 2 Kings, 1 and 2 Chronicle, Ezra, Nehemiah, Esther, Job, Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Solomon (also called Song of Songs), Isaiah, Jeremiah, Lamentations, Ezekiel, Daniel, Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuh, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi. Combing the Old and New Testaments, Protestant Bibles have 66 books.

The Catholic Bible includes the same 39 books as the Protestant Bible, with an additional seven books called the Deuterocanon: Tobit, Judith, Baruch, Sirach, 1 and 2 Maccabees, and Wisdom. Additionally, the books Esther and Daniel in the Catholic Bible contain more text than their Protestant counterparts. In total, the Catholic Bible has 73 books, 46 of those being the Old Testament.

The Greek Orthodox Bible includes the 46 books of the Catholic Old Testament, with an additional three: Prayer of Manasseh, 1 Esdras, and 3 Maccabees. Also, while the Protestant and Catholic Bibles contain 150 Psalms, the Greek Orthodox has 151. In total, the Greek Orthodox Bible contains 76 books.

The Slavonic Orthodox and Georgian Orthodox Bibles contain the same books as the Greek Orthodox.

The Armenian Apostolic Bible contains 50 Old Testament books: The 49 books in the Greek Orthodox Bible, and one other: 2 Esdras. This Bible contains Psalm 151. The Armenian Apostolic Bible contains 77 total books.

The Syrian Orthodox Old Testament has 48 books: All the books of the Catholic Old Testament with the additions of Prayer of Manasseh and 3 Maccabees. This Bible contains Psalm 151. The Syrian Orthodox Bible contains 75 total books.

The Coptic Orthodox Bible has 47 Old Testament books: All the books of the Catholic Old Testament with Prayer of Manasseh added. This Bible contains Psalm 151. The Coptic Orthodox Bible contains 74 books.

The Orthodox Tewahedo Bible is the canon for both the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church and the Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church. This Bible has the 39 Protestant Old Testament Books, and the additional books Jubilees, Enoch, Meqabyan, Ezra Sutuel, Tobith, and Judith. This Bible contains Psalm 151, and the books 2 Chronicles and Jeremiah are extended. The Orthodox Tewahedo Bible contains 73 books.

The Assyrian Church of the East has the 46 books of the Catholic Old Testament, plus two: Prayer of Manasseh and 3 Macabees. This Bible contains Psalm 151, and Baruch is extended. The Assyrian Church of the East Bible contains 75 books.

I hope this information serves you well if you ever end up on Who Wants to Be a Millionaire or something one day

25 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I saw your post about angels being accurate to the bible vs the Torah and was a little confused. I was taught (from an xian background) that the Torah is made up of the same writings as the first five books of the old testament, so Genesis-Exodus-Leviticus-Numbers-Deuteronomy. But you said the angelic descriptions people reference come from Ezekiel.

So even though xianity is definitely derived from judaism, wouldn’t that still mean that these angels are a xian creation? In the same way that Islam is also based on Judaic/Abrahamic faith but something being written in the Q’ran doesn’t de facto make it a Jewish creation?

Not meaning any disrespect at all, just hoping for clarification 💙

hi, I'm gonna assume that this is a ask from a kind person who simply didn't know much about Judaism. so allow me to explain.

first of all, I don't think I made it very clear, but I'm not saying that calling those types of angels "biblically accurate" was bad because they're not part of the Bible. I was saying that they are only a small part of the many different types and interpretations and appearances of angels in religious texts. those types of angels, which I call Ezekielan angels, really only appear in that form in the book of Ezekiel as he's describing his dream. but there are many other angels that appear in other religious texts that look nothing like the Ezekielan angels. it's kinda like saying that the United States is "America" when it's just one country out of 35 countries that are part of the two American continents.

but also, and I don't blame you for not knowing because it's a common mistake, but the Torah isn't our only religious text. the Torah is a part of the Tanakh. the Tanakh is made up of: Torah, the Teaching of Moses, the first five books. Nevi'im, the books of the prophets. and Ketuvim, for the Writings, which include the psalms and wisdom literature. the Book of Ezekiel is the third of the Latter Prophets, and one of the major prophetic books.

and yes, christianity does borrow a lot from Judaism, and simply calls it the "old testament". but from what understand about christianity, the "old testament" isn't as important to them as the gospel (the four books about jesus) and the other new testament books. a helpful thing to remember is that the "old testament" existed before christianity, and is mostly just straight up copied from the Tanakh

hope that makes sense.

I want to try my best to educate people. so as long as you aren't intentionally being hateful, I'll try and help people learn.

34 notes

·

View notes

Note

Secondary bracket?? When and where can I see my grandpas?? Also speaking of... just curious did anyone else submit people from Tanakh (Torah, Nevi'im, Ketuvim) or even Talmud (Mishna and Gemara) or am I just really excited about my future family? - Torah loving anon (still holding back infodumps because it's no longer relevant to the bracket and also I need to sleep have a nice day)

After the main bracket, I will be doing a secondary bracket where I will be choosing the competitors from the pool of people that didn't get enough nominations, based on the answers given in the submissions.

3 people submitted Moshe, 2 submitted Metushelah, and 1 submitted Abraham and Sarah

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

the religious texts of manichaeism have the distinction of being supposedly written by the prophet himself (mani) but NOT being direct word of god. i cant think of any other cases like this, usually its either explicitly written by someone else (jesus, buddha, zoroaster) word of god (torah, quran), or theres no claimed author (most mythology). maybe some of the tanakh? who are the nevi'im supposed to be written by, like, traditionally. quick google suggests they're sometimes in the first person? so that suggests theyre supposed to have been written by the prophets. although theyre not like, THE prophet the way mani is the prophet. i guess the pseudoepigraphical tradition is sort of like this too

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Watch "TORAH STUDY" on YouTube

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

hello! i saw your blazed post about your book, and it looks really interesting! i hope you don't mind questions, because i have something i'm curious about.

i noticed the books in your tetralogy have Hebrew titles. i think that's really cool! when i read the descriptions though i didn't see reference to that anywhere. if you don't mind answering, what's the significance of the titles?

i plan on reading the books regardless of your answer (as in right after i send this ask), but i'm always intrigued (as a Jew myself) when i see stuff like this. thank you for reading my message and for making such a cool story!

Hey, thanks so much for the ask! I guess there's a few layers to this, which I'll answer as unspoilingly as possible. And, since it'll be posted publicly, I'll go a bit into the words for other folks reading, too.

The core reason for this comes from a central character, Michelle Hadje, who was "raised vaguely Jewish" (her words, it's complicated :P) then, to varying degrees, drifted closer to those roots over the years. While this isn't often directly plot-relevant, it nevertheless informs the entirety of her and her clade (a group of copies or 'forks' of her who have long since individuated).

The base significance for each title is as follows:

Qoheleth - There's a character who goes by Qoheleth, which is an Anglicization of the Hebrew word kohelet. The word refers to a teacher or a gatherer of the assembled, and is the title of the book in the Tanakh of the same name, also known as Ecclesiastes. It's an older Anglicization (and is combined 'Hebel', an older Anglicization of the Hebrew havél, meaning breath or, in context, meaningless or vanity). The reason he's chosen this name is plot relevant, so I'll stop there. Needless to say, ideas of wisdom versus folly are woven throughout.

Toledot - The Hebrew word toledot refers to generations, lineage, or inheritance. You can think of it as the 'begats'; it's the list of generations and lineages in Genesis 25-28. The book takes place over two time periods (2124 and 2325), involving the changes that Michelle's clade goes through to become who they are. Additionally, one of their distant cousins outside of the system is a character who, despite having never met Michelle, is obsessed with her past. Finally, there is a brief discussion of a very historically fraught document called the Toledot Yeshu — the generations of Jesus — and a particular interpretation of one of the sentences.

Nevi'im - This title refers to prophets. It's the 'na' in Tanakh (Torah, Nevi'im, Ketuvim, the three sections of the Hebrew bible). This one is probably the most bound up in plot, so all I'll really be able to say is that some events happen surrounding a new group of characters that herald a change both for society and for the the clade at the center of all of this.

Mitzvot - I'll admit, this was a working title that just kind of stuck in the end. It initially was based off a one-off comment from a character ("As you intentionally moved towards feeling, I worked to contain and compartmentalize it within myself after you came into being. I became a being of negative commandments. I lived the 'shalt not's while you performed your mitzvot of loving and caring."). While I'd always meant to change it, it wound up growing on me. This refers to commandments, yes, but also the actions one takes to fulfill those commandments — it's the plural of mitzvah, so if you've heard something like "you've done a mitzvah", that's where that comes from. It stuck around as a title since a theme in the story is just how one defines oneself through one's actions.

Now for the "why" part, and the part that makes me very anxious about all of this. It's intensely personal, and maybe not even that interesting, and I worry that it will come off as insulting or appropriative. Feel free to skip, though. It's long and wandery.

The most abstract layer to all of this is that I think the greatest utility writing for the author is as a tool of self-exploration. It's an excuse to do a lot of research into something one's interested in, sure, but that interest comes from somewhere.

I'll be up front and say that I'm not Jewish, and I'll also be honest and say that this is a very confusing and tender part of my life.

I'm a Quaker, and I suppose I'm pretty happy with that! I get to be surrounded by a bunch of leftists who are both politically and spiritually active. My life has a built-in contemplative aspect that, combined with the community aspect, allows for a lot of introspection that was inaccessible (or at least discouraged) in a lot of my early life.

There is, however, a universe not too dissimilar from this one where I converted to Judaism. That may yet be this universe, even. Every time I think about why, though, I realize I don't know. I don't know! I've spent decade thinking about it now, and, while I've learned a ton about both myself and Judaism, I sometimes feel no closer to an understanding of my relationship to it.

The only times I do feel like I'm coming closer are when I'm writing. It's not the first time I've used writing for discernment; I have a novella that investigates a Catholic point of view which led to me veering further from that particular lived experience.

The Post-Self tetralogy was an outlet for researching Judaism, yes, but it's also an outlet for introspection and interrogation of the self. It's not even the only project that does such: a third of my MFA thesis is a braided essay, with one strand being what amounts to an exegesis of the book of Job with the thesis that, after the events of the book, he had a choice to head either in the direction of the author of Kohelet, building wisdom, or in the direction of Jonah, harboring that anger in an attempt to shield himself from his own fear.

The other strand, though, is about my own choice after an event early in the exploration into gender that led to me transitioning. From that point, I could have bundled myself up in cynicism and stayed stubbornly masculine, resenting my life and myself in order to cushion myself from those rough edges of fear, hoping only that that anger would be less likely tear up me up from the inside. I wound up choosing the other option, though, passing through the death of Matthew and the birth of Madison.

I bring this up specifically to tie back to something I said all the way back in the second paragraph: even though I wasn't raised vaguely Jewish as Michelle was, it nonetheless informs several aspects of my life. I'm not Job. I'm not Kohelet. It's just that I was presented with my own choice of Job and chose to head in what I hope is the direction towards wisdom, away from fear.

I suppose we all must be confronted with these choices at some point in our lives, and through writing-as-discernment, I guess I'm trying to untangle if the reason this isn't the universe where I converted is because, at some point in the past, I chose some other direction at some other inflection point.

This is probably more answer than you were specifically looking for, but I strive to be earnest and accountable for my actions. I do hope that you enjoy the books, even in all of their imperfections, even if you disregard this bit of introspection. I hope they stand on their own even if only as works of curiosity and queer lives in some more hopeful world.

Thanks again for asking and getting me to think through this and put into words what I've been feeling on some deeper level.

-----

Addenda:

To be clear, 'mitzvot' refers to all 613 commandments, not just the ten that I'm sure leap to mind given that word.

I chose Toledot for the title of book 2 before I knew some of the history behind how the Toledot Yeshu was used by Christians against Jews, and while I stand by the point that's made in the book by Dear and Yared, I probably could have handled it better. Nevertheless, as the editors of the New Oxford Annotated Bible say of Job, it is "part of the book we now have." When I read things I wrote and find things I dislike about it, it is perhaps a sign that I've become a better writer since.

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

The Bible (from Koine Greek τὰ βιβλία, tà biblía, 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthology – a compilation of texts of a variety of forms – originally written in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Koine Greek. These texts include instructions, stories, poetry, and prophecies, among other genres. The collection of materials that are accepted as part of the Bible by a particular religious tradition or community is called a biblical canon. Believers in the Bible generally consider it to be a product of divine inspiration, but the way they understand what that means and interpret the text can vary.

The religious texts were compiled by different religious communities into various official collections. The earliest contained the first five books of the Bible. It is called the Torah in Hebrew and the Pentateuch (meaning five books) in Greek; the second oldest part was a collection of narrative histories and prophecies (the Nevi'im); the third collection (the Ketuvim) contains psalms, proverbs, and narrative histories. "Tanakh" is an alternate term for the Hebrew Bible composed of the first letters of those three parts of the Hebrew scriptures: the Torah ("Teaching"), the Nevi'im ("Prophets"), and the Ketuvim ("Writings"). The Masoretic Text is the medieval version of the Tanakh, in Hebrew and Aramaic, that is considered the authoritative text of the Hebrew Bible by modern Rabbinic Judaism. The Septuagint is a Koine Greek translation of the Tanakh from the third and second centuries BCE (Before Common Era); it largely overlaps with the Hebrew Bible.

Christianity began as an outgrowth of Judaism, using the Septuagint as the basis of the Old Testament. The early Church continued the Jewish tradition of writing and incorporating what it saw as inspired, authoritative religious books. The gospels, Pauline epistles and other texts quickly coalesced into the New Testament.

With estimated total sales of over five billion copies, the Bible is the best-selling publication of all time. It has had a profound influence both on Western culture and history and on cultures around the globe. The study of it through biblical criticism has indirectly impacted culture and history as well. The Bible is currently translated or being translated into about half of the world's languages.

Etymology

The term "Bible" can refer to the Hebrew Bible or the Christian Bible, which contains both the Old and New Testaments.[1]

The English word Bible is derived from Koinē Greek: τὰ βιβλία, romanized: ta biblia, meaning "the books" (singular βιβλίον, biblion).[2] The word βιβλίον itself had the literal meaning of "scroll" and came to be used as the ordinary word for "book".[3] It is the diminutive of βύβλος byblos, "Egyptian papyrus", possibly so called from the name of the Phoenician sea port Byblos (also known as Gebal) from whence Egyptian papyrus was exported to Greece.[4]

The Greek ta biblia ("the books") was "an expression Hellenistic Jews used to describe their sacred books".[5] The biblical scholar F. F. Bruce notes that John Chrysostom appears to be the first writer (in his Homilies on Matthew, delivered between 386 and 388) to use the Greek phrase ta biblia ("the books") to describe both the Old and New Testaments together.[6]

Latin biblia sacra "holy books" translates Greek τὰ βιβλία τὰ ἅγια (tà biblía tà hágia, "the holy books").[7] Medieval Latin biblia is short for biblia sacra "holy book". It gradually came to be regarded as a feminine singular noun (biblia, gen. bibliae) in medieval Latin, and so the word was loaned as singular into the vernaculars of Western Europe.[8]

Development and history

See also: Biblical manuscript, Textual criticism, and Samaritan Pentateuch

Hebrew Bible from 1300. Genesis.

The Bible is not a single book; it is a collection of books whose complex development is not completely understood. The oldest books began as songs and stories orally transmitted from generation to generation. Scholars are just beginning to explore "the interface between writing, performance, memorization, and the aural dimension" of the texts. Current indications are that the ancient writing–reading process was supplemented by memorization and oral performance in community.[9] The Bible was written and compiled by many people, most of whom are unknown, from a variety of disparate cultures.[10]

British biblical scholar John K. Riches wrote:[11]

The books of the Bible were initially written and copied by hand on papyrus scrolls.[12] No originals survive. The age of the original composition of the texts is therefore difficult to determine and heavily debated. Using a combined linguistic and historiographical approach, Hendel and Joosten date the oldest parts of the Hebrew Bible (the Song of Deborah in Judges 5 and the Samson story of Judges 16 and 1 Samuel) to having been composed in the premonarchial early Iron Age (c. 1200 BCE).[13] The Dead Sea Scrolls, discovered in the caves of Qumran in 1947, are copies that can be dated to between 250 BCE and 100 CE. They are the oldest existing copies of the books of the Hebrew Bible of any length that are not fragments.[14]

The Great Isaiah Scroll (1QIsaa), one of the Dead Sea Scrolls. It is the oldest complete copy of the Book of Isaiah.

The earliest manuscripts were probably written in paleo-Hebrew, a kind of cuneiform pictograph similar to other pictographs of the same period.[15] The exile to Babylon most likely prompted the shift to square script (Aramaic) in the fifth to third centuries BCE.[16] From the time of the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Hebrew Bible was written with spaces between words to aid in reading.[17] By the eighth century CE, the Masoretes added vowel signs.[18] Levites or scribes maintained the texts, and some texts were always treated as more authoritative than others.[19] Scribes preserved and changed the texts by changing the script and updating archaic forms while also making corrections. These Hebrew texts were copied with great care.[20]

Considered to be scriptures (sacred, authoritative religious texts), the books were compiled by different religious communities into various biblical canons (official collections of scriptures).[21] The earliest compilation, containing the first five books of the Bible and called the Torah (meaning "law", "instruction", or "teaching") or Pentateuch ("five books"), was accepted as Jewish canon by the fifth century BCE. A second collection of narrative histories and prophesies, called the Nevi'im ("prophets"), was canonized in the third century BCE. A third collection called the Ketuvim ("writings"), containing psalms, proverbs, and narrative histories, was canonized sometime between the second century BCE and the second century CE.[22] These three collections were written mostly in Biblical Hebrew, with some parts in Aramaic, which together form the Hebrew Bible or "TaNaKh" (an abbreviation of "Torah", "Nevi'im", and "Ketuvim").[23]

Hebrew Bible

There are three major historical versions of the Hebrew Bible: the Septuagint, the Masoretic Text, and the Samaritan Pentateuch (which contains only the first five books). They are related but do not share the same paths of development. The Septuagint, or the LXX, is a translation of the Hebrew scriptures, and some related texts, into Koine Greek, begun in Alexandria in the late third century BCE and completed by 132 BCE.[24][25][a] Probably commissioned by Ptolemy II Philadelphus, King of Egypt, it addressed the need of the primarily Greek-speaking Jews of the Graeco-Roman diaspora.[24][26] Existing complete copies of the Septuagint date from the third to the fifth centuries CE, with fragments dating back to the second century BCE. [27] Revision of its text began as far back as the first century BCE.[28] Fragments of the Septuagint were found among the Dead Sea Scrolls; portions of its text are also found on existing papyrus from Egypt dating to the second and first centuries BCE and to the first century CE.[28]: 5

The Masoretes began developing what would become the authoritative Hebrew and Aramaic text of the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible in Rabbinic Judaism near the end of the Talmudic period (c. 300–c. 500 CE), but the actual date is difficult to determine.[29][30][31] In the sixth and seventh centuries, three Jewish communities contributed systems for writing the precise letter-text, with its vocalization and accentuation known as the mas'sora (from which we derive the term "masoretic").[29] These early Masoretic scholars were based primarily in the Galilean cities of Tiberias and Jerusalem, and in Babylonia (modern Iraq). Those living in the Jewish community of Tiberias in ancient Galilee (c. 750–950), made scribal copies of the Hebrew Bible texts without a standard text, such as the Babylonian tradition had, to work from. The canonical pronunciation of the Hebrew Bible (called Tiberian Hebrew) that they developed, and many of the notes they made, therefore differed from the Babylonian.[32] These differences were resolved into a standard text called the Masoretic text in the ninth century.[33] The oldest complete copy still in existence is the Leningrad Codex dating to c. 1000 CE.[34]

The Samaritan Pentateuch is a version of the Torah maintained by the Samaritan community since antiquity, which was rediscovered by European scholars in the 17th century; its oldest existing copies date to c. 1100 CE.[35] Samaritans include only the Pentateuch (Torah) in their biblical canon.[36] They do not recognize divine authorship or inspiration in any other book in the Jewish Tanakh.[b] A Samaritan Book of Joshua partly based upon the Tanakh's Book of Joshua exists, but Samaritans regard it as a non-canonical secular historical chronicle.[37]

In the seventh century, the first codex form of the Hebrew Bible was produced. The codex is the forerunner of the modern book. Popularized by early Christians, it was made by folding a single sheet of papyrus in half, forming "pages". Assembling multiples of these folded pages together created a "book" that was more easily accessible and more portable than scrolls. In 1488, the first complete printed press version of the Hebrew Bible was produced.[38]

New Testament

Saint Paul Writing His Epistles, c. 1619 painting by Valentin de Boulogne

During the rise of Christianity in the first century CE, new scriptures were written in Koine Greek. Christians called these new scriptures the "New Testament", and began referring to the Septuagint as the "Old Testament".[39] The New Testament has been preserved in more manuscripts than any other ancient work.[40][41] Most early Christian copyists were not trained scribes.[42] Many copies of the gospels and Paul's letters were made by individual Christians over a relatively short period of time very soon after the originals were written.[43] There is evidence in the Synoptic Gospels, in the writings of the early church fathers, from Marcion, and in the Didache that Christian documents were in circulation before the end of the first century.[44][45] Paul's letters were circulated during his lifetime, and his death is thought to have occurred before 68 during Nero's reign.[46][47] Early Christians transported these writings around the Empire, translating them into Old Syriac, Coptic, Ethiopic, and Latin, among other languages.[48]

Bart Ehrman explains how these multiple texts later became grouped by scholars into categories:

during the early centuries of the church, Christian texts were copied in whatever location they were written or taken to. Since texts were copied locally, it is no surprise that different localities developed different kinds of textual tradition. That is to say, the manuscripts in Rome had many of the same errors, because they were for the most part "in-house" documents, copied from one another; they were not influenced much by manuscripts being copied in Palestine; and those in Palestine took on their own characteristics, which were not the same as those found in a place like Alexandria, Egypt. Moreover, in the early centuries of the church, some locales had better scribes than others. Modern scholars have come to recognize that the scribes in Alexandria – which was a major intellectual center in the ancient world – were particularly scrupulous, even in these early centuries, and that there, in Alexandria, a very pure form of the text of the early Christian writings was preserved, decade after decade, by dedicated and relatively skilled Christian scribes.[49]

These differing histories produced what modern scholars refer to as recognizable "text types". The four most commonly recognized are Alexandrian, Western, Caesarean, and Byzantine.[50]

The Rylands fragment P52 verso is the oldest existing fragment of New Testament papyrus.[51] It contains phrases from the 18th chapter of the Gospel of John.

The list of books included in the Catholic Bible was established as canon by the Council of Rome in 382, followed by those of Hippo in 393 and Carthage in 397. Between 385 and 405 CE, the early Christian church translated its canon into Vulgar Latin (the common Latin spoken by ordinary people), a translation known as the Vulgate.[52] Since then, Catholic Christians have held ecumenical councils to standardize their biblical canon. The Council of Trent (1545–63), held by the Catholic Church in response to the Protestant Reformation, authorized the Vulgate as its official Latin translation of the Bible.[53] A number of biblical canons have since evolved. Christian biblical canons range from the 73 books of the Catholic Church canon, and the 66-book canon of most Protestant denominations, to the 81 books of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church canon, among others.[54] Judaism has long accepted a single authoritative text, whereas Christianity has never had an official version, instead having many different manuscript traditions.[55]

Variants

All biblical texts were treated with reverence and care by those that copied them, yet there are transmission errors, called variants, in all biblical manuscripts.[56][57] A variant is any deviation between two texts. Textual critic Daniel B. Wallace explains that "Each deviation counts as one variant, regardless of how many MSS [manuscripts] attest to it."[58] Hebrew scholar Emanuel Tov says the term is not evaluative; it is a recognition that the paths of development of different texts have separated.[59]

Medieval handwritten manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible were considered extremely precise: the most authoritative documents from which to copy other texts.[60] Even so, David Carr asserts that Hebrew texts still contain some variants.[61] The majority of all variants are accidental, such as spelling errors, but some changes were intentional.[62] In the Hebrew text, "memory variants" are generally accidental differences evidenced by such things as the shift in word order found in 1 Chronicles 17:24 and 2 Samuel 10:9 and 13. Variants also include the substitution of lexical equivalents, semantic and grammar differences, and larger scale shifts in order, with some major revisions of the Masoretic texts that must have been intentional.[63]

Intentional changes in New Testament texts were made to improve grammar, eliminate discrepancies, harmonize parallel passages, combine and simplify multiple variant readings into one, and for theological reasons.[62][64] Bruce K. Waltke observes that one variant for every ten words was noted in the recent critical edition of the Hebrew Bible, the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia, leaving 90% of the Hebrew text without variation. The fourth edition of the United Bible Society's Greek New Testament notes variants affecting about 500 out of 6900 words, or about 7% of the text.[65]

Further information: Textual variants in the Hebrew Bible and Textual variants in the New Testament

Content and themes

Themes

Further information: Ethics in the Bible, Jewish ethics, and Christian ethics

Creation of Light, by Gustave Doré.

The narratives, laws, wisdom sayings, parables, and unique genres of the Bible provide opportunity for discussion on most topics of concern to human beings: The role of women,[66]: 203 sex,[67] children, marriage,[68] neighbors,[69]: 24 friends, the nature of authority and the sharing of power,[70]: 45–48 animals, trees and nature,[71]: xi money and economics,[72]: 77 work, relationships,[73] sorrow and despair and the nature of joy, among others.[74] Philosopher and ethicist Jaco Gericke adds: "The meaning of good and evil, the nature of right and wrong, criteria for moral discernment, valid sources of morality, the origin and acquisition of moral beliefs, the ontological status of moral norms, moral authority, cultural pluralism, [as well as] axiological and aesthetic assumptions about the nature of value and beauty. These are all implicit in the texts."[75]

However, discerning the themes of some biblical texts can be problematic.[76] Much of the Bible is in narrative form and in general, biblical narrative refrains from any kind of direct instruction, and in some texts the author's intent is not easy to decipher.[77] It is left to the reader to determine good and bad, right and wrong, and the path to understanding and practice is rarely straightforward.[78] God is sometimes portrayed as having a role in the plot, but more often there is little about God's reaction to events, and no mention at all of approval or disapproval of what the characters have done or failed to do.[79] The writer makes no comment, and the reader is left to infer what they will.[79] Jewish philosophers Shalom Carmy and David Schatz explain that the Bible "often juxtaposes contradictory ideas, without explanation or apology".[80]

The Hebrew Bible contains assumptions about the nature of knowledge, belief, truth, interpretation, understanding and cognitive processes.[81] Ethicist Michael V. Fox writes that the primary axiom of the book of Proverbs is that "the exercise of the human mind is the necessary and sufficient condition of right and successful behavior in all reaches of life".[82] The Bible teaches the nature of valid arguments, the nature and power of language, and its relation to reality.[75] According to Mittleman, the Bible provides patterns of moral reasoning that focus on conduct and character.[83][84]

In the biblical metaphysic, humans have free will, but it is a relative and restricted freedom.[85] Beach says that Christian voluntarism points to the will as the core of the self, and that within human nature, "the core of who we are is defined by what we love".[86] Natural law is in the Wisdom literature, the Prophets, Romans 1, Acts 17, and the book of Amos (Amos 1:3–2:5), where nations other than Israel are held accountable for their ethical decisions even though they don't know the Hebrew god.[87] Political theorist Michael Walzer finds politics in the Hebrew Bible in covenant, law, and prophecy, which constitute an early form of almost democratic political ethics.[88] Key elements in biblical criminal justice begin with the belief in God as the source of justice and the judge of all, including those administering justice on earth.[89]

Carmy and Schatz say the Bible "depicts the character of God, presents an account of creation, posits a metaphysics of divine providence and divine intervention, suggests a basis for morality, discusses many features of human nature, and frequently poses the notorious conundrum of how God can allow evil."[90]

Hebrew Bible

Further information: Hebrew Bible and Development of the Hebrew Bible canonTanakh

show

Torah (Instruction)

show

Nevi'im (Prophets)

show

Ketuvim (Writings)

v

t

e

The authoritative Hebrew Bible is taken from the masoretic text (called the Leningrad Codex) which dates from 1008. The Hebrew Bible can therefore sometimes be referred to as the Masoretic Text.[91]

The Hebrew Bible is also known by the name Tanakh (Hebrew: תנ"ך). This reflects the threefold division of the Hebrew scriptures, Torah ("Teaching"), Nevi'im ("Prophets") and Ketuvim ("Writings") by using the first letters of each word.[92] It is not until the Babylonian Talmud (c. 550 BCE) that a listing of the contents of these three divisions of scripture are found.[93]

The Tanakh was mainly written in Biblical Hebrew, with some small portions (Ezra 4:8–6:18 and 7:12–26, Jeremiah 10:11, Daniel 2:4–7:28)[94] written in Biblical Aramaic, a language which had become the lingua franca for much of the Semitic world.[95]

Torah

Main article: Torah

See also: Oral Torah

A Torah scroll recovered from Glockengasse Synagogue in Cologne.

The Torah (תּוֹרָה) is also known as the "Five Books of Moses" or the Pentateuch, meaning "five scroll-cases".[96] Traditionally these books were considered to have been dictated to Moses by God himself.[97][98] Since the 17th century, scholars have viewed the original sources as being the product of multiple anonymous authors while also allowing the possibility that Moses first assembled the separate sources.[99][100] There are a variety of hypotheses regarding when and how the Torah was composed,[101] but there is a general consensus that it took its final form during the reign of the Persian Achaemenid Empire (probably 450–350 BCE),[102][103] or perhaps in the early Hellenistic period (333–164 BCE).[104]

Samaritan Inscription containing portion of the Bible in nine lines of Hebrew text, currently housed in the British Museum

The Hebrew names of the books are derived from the first words in the respective texts. The Torah consists of the following five books:

Genesis, Beresheeth (בראשית)

Exodus, Shemot (שמות)

Leviticus, Vayikra (ויקרא)

Numbers, Bamidbar (במדבר)

Deuteronomy, Devarim (דברים)

The first eleven chapters of Genesis provide accounts of the creation (or ordering) of the world and the history of God's early relationship with humanity. The remaining thirty-nine chapters of Genesis provide an account of God's covenant with the biblical patriarchs Abraham, Isaac and Jacob (also called Israel) and Jacob's children, the "Children of Israel", especially Joseph. It tells of how God commanded Abraham to leave his family and home in the city of Ur, eventually to settle in the land of Canaan, and how the Children of Israel later moved to Egypt.

The remaining four books of the Torah tell the story of Moses, who lived hundreds of years after the patriarchs. He leads the Children of Israel from slavery in ancient Egypt to the renewal of their covenant with God at Mount Sinai and their wanderings in the desert until a new generation was ready to enter the land of Canaan. The Torah ends with the death of Moses.[105]

The commandments in the Torah provide the basis for Jewish religious law. Tradition states that there are 613 commandments (taryag mitzvot).

Nevi'im

Main article: Nevi'imBooks of Nevi'im Former Prophets

Joshua

Judges

Samuel

Kings

Latter Prophets (major)

Isaiah

Jeremiah

Ezekiel

Latter Prophets (Twelve minor)

Hosea

Joel

Amos

Obadiah

Jonah

Micah

Nahum

Habakkuk

Zephaniah

Haggai

Zechariah

Malachi

Hebrew Bible

v

t

e

Nevi'im (Hebrew: נְבִיאִים, romanized: Nəḇî'îm, "Prophets") is the second main division of the Tanakh, between the Torah and Ketuvim. It contains two sub-groups, the Former Prophets (Nevi'im Rishonim נביאים ראשונים, the narrative books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings) and the Latter Prophets (Nevi'im Aharonim נביאים אחרונים, the books of Isaiah, Jeremiah and Ezekiel and the Twelve Minor Prophets).

The Nevi'im tell a story of the rise of the Hebrew monarchy and its division into two kingdoms, the Kingdom of Israel and the Kingdom of Judah, focusing on conflicts between the Israelites and other nations, and conflicts among Israelites, specifically, struggles between believers in "the LORD God"[106] (Yahweh) and believers in foreign gods,[c][d] and the criticism of unethical and unjust behaviour of Israelite elites and rulers;[e][f][g] in which prophets played a crucial and leading role. It ends with the conquest of the Kingdom of Israel by the Neo-Assyrian Empire, followed by the conquest of the Kingdom of Judah by the neo-Babylonian Empire and the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem.

Former Prophets

The Former Prophets are the books Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings. They contain narratives that begin immediately after the death of Moses with the divine appointment of Joshua as his successor, who then leads the people of Israel into the Promised Land, and end with the release from imprisonment of the last king of Judah. Treating Samuel and Kings as single books, they cover:

Joshua's conquest of the land of Canaan (in the Book of Joshua),

the struggle of the people to possess the land (in the Book of Judges),

the people's request to God to give them a king so that they can occupy the land in the face of their enemies (in the Books of Samuel)

the possession of the land under the divinely appointed kings of the House of David, ending in conquest and foreign exile (Books of Kings)

Latter Prophets

Further information: Major prophet

The Latter Prophets are Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel and the Twelve Minor Prophets, counted as a single book.

Hosea, Hoshea (הושע) denounces the worship of gods other than Yehovah, comparing Israel to a woman being unfaithful to her husband.

Joel, Yoel (יואל) includes a lament and a promise from God.

Amos, Amos (עמוס) speaks of social justice, providing a basis for natural law by applying it to unbelievers and believers alike.

Obadiah, Ovadyah (עבדיה) addresses the judgment of Edom and restoration of Israel.

Jonah, Yonah (יונה) tells of a reluctant redemption of Ninevah.

Micah, Mikhah (מיכה) reproaches unjust leaders, defends the rights of the poor, and looks forward to world peace.

Nahum, Nahum (נחום) speaks of the destruction of Nineveh.

Habakkuk, Havakuk (חבקוק) upholds trust in God over Babylon.

Zephaniah, Tsefanya (צפניה) pronounces coming of judgment, survival and triumph of remnant.

Haggai, Khagay (חגי) rebuild Second Temple.

Zechariah, Zekharyah (זכריה) God blesses those who repent and are pure.

Malachi, Malakhi (מלאכי) corrects lax religious and social behaviour.

Ketuvim

Hebrew text of Psalm 1:1–2

Main articles: Ketuvim and Poetic BooksBooks of the Ketuvim Three poetic books

Psalms

Proverbs

Job

Five Megillot (Scrolls)

Song of Songs

Ruth

Lamentations

Ecclesiastes

Esther

Other books

Daniel

Ezra–Nehemiah (Ezra

Nehemiah)

Chronicles

Hebrew Bible

v

t

e

Ketuvim or Kəṯûḇîm (in Biblical Hebrew: כְּתוּבִי�� "writings") is the third and final section of the Tanakh. The Ketuvim are believed to have been written under the inspiration of Ruach HaKodesh (the Holy Spirit) but with one level less authority than that of prophecy.[107]

In Masoretic manuscripts (and some printed editions), Psalms, Proverbs and Job are presented in a special two-column form emphasizing their internal parallelism, which was found early in the study of Hebrew poetry. "Stichs" are the lines that make up a verse "the parts of which lie parallel as to form and content".[108] Collectively, these three books are known as Sifrei Emet (an acronym of the titles in Hebrew, איוב, משלי, תהלים yields Emet אמ"ת, which is also the Hebrew for "truth"). Hebrew cantillation is the manner of chanting ritual readings as they are written and notated in the Masoretic Text of the Bible. Psalms, Job and Proverbs form a group with a "special system" of accenting used only in these three books.[109]

The five scrolls

Further information: Five Megillot

Song of Songs (Das Hohelied Salomos), No. 11 by Egon Tschirch, 1923

The five relatively short books of Song of Songs, Book of Ruth, the Book of Lamentations, Ecclesiastes and Book of Esther are collectively known as the Hamesh Megillot. These are the latest books collected and designated as "authoritative" in the Jewish canon even though they were not complete until the second century CE.[110]

Other books

The books of Esther, Daniel, Ezra-Nehemiah[h] and Chronicles share a distinctive style that no other Hebrew literary text, biblical or extra-biblical, shares.[111] They were not written in the normal style of Hebrew of the post-exilic period. The authors of these books must have chosen to write in their own distinctive style for unknown reasons.[112]

Their narratives all openly describe relatively late events (i.e., the Babylonian captivity and the subsequent restoration of Zion).

The Talmudic tradition ascribes late authorship to all of them.

Two of them (Daniel and Ezra) are the only books in the Tanakh with significant portions in Aramaic.

Book order

The following list presents the books of Ketuvim in the order they appear in most current printed editions.

Tehillim (Psalms) תְהִלִּים is an anthology of individual Hebrew religious hymns.

Mishlei (Book of Proverbs) מִשְלֵי is a "collection of collections" on values, moral behavior, the meaning of life and right conduct, and its basis in faith.

Iyyôbh (Book of Job) אִיּוֹב is about faith, without understanding or justifying suffering.

Shīr Hashshīrīm (Song of Songs) or (Song of Solomon) שִׁיר הַשִׁירִים (Passover) is poetry about love and sex.

Rūth (Book of Ruth) רוּת (Shābhû‘ôth) tells of the Moabite woman Ruth, who decides to follow the God of the Israelites, and remains loyal to her mother-in-law, who is then rewarded.

Eikhah (Lamentations) איכה (Ninth of Av) [Also called Kinnot in Hebrew.] is a collection of poetic laments for the destruction of Jerusalem in 586 BCE.

Qōheleth (Ecclesiastes) קהלת (Sukkôth) contains wisdom sayings disagreed over by scholars. Is it positive and life-affirming, or deeply pessimistic?

Estēr (Book of Esther) אֶסְתֵר (Pûrîm) tells of a Hebrew woman in Persia who becomes queen and thwarts a genocide of her people.

Dānî’ēl (Book of Daniel) דָּנִיֵּאל combines prophecy and eschatology (end times) in story of God saving Daniel just as He will save Israel.

‘Ezrā (Book of Ezra–Book of Nehemiah) עזרא tells of rebuilding the walls of Jerusalem after the Babylonian exile.

Divrei ha-Yamim (Chronicles) דברי הימים contains genealogy.

The Jewish textual tradition never finalized the order of the books in Ketuvim. The Babylonian Talmud (Bava Batra 14b–15a) gives their order as Ruth, Psalms, Job, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Solomon, Lamentations of Jeremiah, Daniel, Scroll of Esther, Ezra, Chronicles.[113]

One of the large scale differences between the Babylonian and the Tiberian biblical traditions is the order of the books. Isaiah is placed after Ezekiel in the Babylonian, while Chronicles opens the Ketuvim in the Tiberian, and closes it in the Babylonian.[114]

The Ketuvim is the last of the three portions of the Tanakh to have been accepted as canonical. While the Torah may have been considered canon by Israel as early as the fifth century BCE and the Former and Latter Prophets were canonized by the second century BCE, the Ketuvim was not a fixed canon until the second century CE.[110]

Evidence suggests, however, that the people of Israel were adding what would become the Ketuvim to their holy literature shortly after the canonization of the prophets. As early as 132 BCE references suggest that the Ketuvim was starting to take shape, although it lacked a formal title.[115] Against Apion, the writing of Josephus in 95 CE, treated the text of the Hebrew Bible as a closed canon to which "... no one has ventured either to add, or to remove, or to alter a syllable..."[116] For an extended period after 95CE, the divine inspiration of Esther, the Song of Songs, and Ecclesiastes was often under scrutiny.[117]

The Isaiah scroll, which is a part of the Dead Sea Scrolls, contains almost the whole Book of Isaiah. It dates from the second century BCE.

Septuagint

Main articles: Septuagint and Jewish apocrypha

See also: Deuterocanonical books and Biblical apocrypha

Fragment of a Septuagint: A column of uncial book from 1 Esdras in the Codex Vaticanus c. 325–350 CE, the basis of Sir Lancelot Charles Lee Brenton's Greek edition and English translation.

The Septuagint ("the Translation of the Seventy", also called "the LXX"), is a Koine Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible begun in the late third century BCE.

As the work of translation progressed, the Septuagint expanded: the collection of prophetic writings had various hagiographical works incorporated into it. In addition, some newer books such as the Books of the Maccabees and the Wisdom of Sirach were added. These are among the "apocryphal" books, (books whose authenticity is doubted). The inclusion of these texts, and the claim of some mistranslations, contributed to the Septuagint being seen as a "careless" translation and its eventual rejection as a valid Jewish scriptural text.[118][119][i]

The apocrypha are Jewish literature, mostly of the Second Temple period (c. 550 BCE – 70 CE); they originated in Israel, Syria, Egypt or Persia; were originally written in Hebrew, Aramaic, or Greek, and attempt to tell of biblical characters and themes.[121] Their provenance is obscure. One older theory of where they came from asserted that an "Alexandrian" canon had been accepted among the Greek-speaking Jews living there, but that theory has since been abandoned.[122] Indications are that they were not accepted when the rest of the Hebrew canon was.[122] It is clear the Apocrypha were used in New Testament times, but "they are never quoted as Scripture."[123] In modern Judaism, none of the apocryphal books are accepted as authentic and are therefore excluded from the canon. However, "the Ethiopian Jews, who are sometimes called Falashas, have an expanded canon, which includes some Apocryphal books".[124]

The contents page in a complete 80 book King James Bible, listing "The Books of the Old Testament", "The Books called Apocrypha", and "The Books of the New Testament".