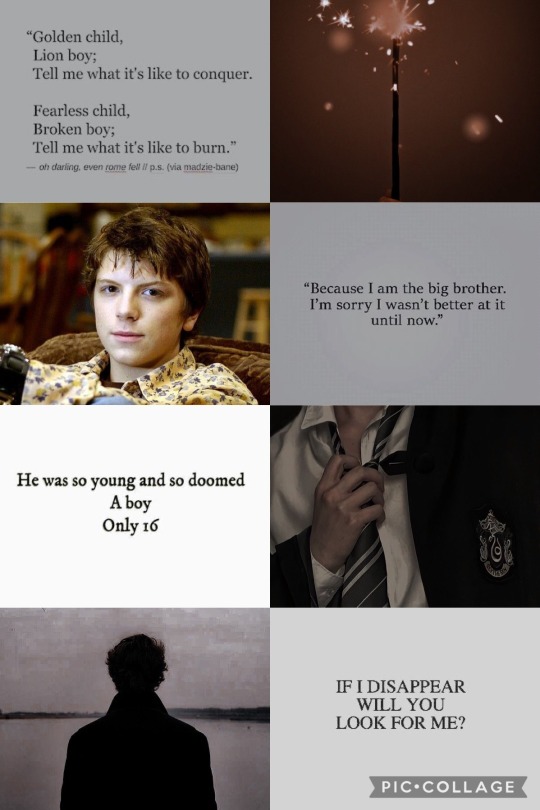

#Jacob Venturi

Text

Bill Weasely 🤝 Jacob : being tricked and used by Rakepick

#acey speaking#hphm#bill weasley#jacob ( hphm)#jacob venturi#i have decided they will be friends post Redacted#listening to My Goodbye from Epic and yea it fits Bill ( shoutout to Tori for her art and Feelings lol)#but but but#'ill remind you every time someone dies ( Ashe) IM left to deal with the strain#also '#this way you'll know ehat your place is/this way you won't close the line “ leaving him in the portrait#LISTEN#i have terminal jscob brainrot and you all must suffer with me lmao

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝓙𝓪𝓬𝓸𝓫 𝓥𝓮𝓷𝓽𝓾𝓻𝓲 • HPHM

→ my half of an aesthetic trade with @smarti-at-smogwarts | @aceyanaheim

#jacob venturi#hphm#hogwarts mystery#hphm jacob#my aesthetic#aesthetic trade#other people’s ocs#hope you like it!!

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

NASA Selects Companies to Advance Moon Mobility for Artemis Missions

NASA

NASA has selected Intuitive Machines, Lunar Outpost, and Venturi Astrolab to advance capabilities for a lunar terrain vehicle (LTV) that Artemis astronauts will use to travel around the lunar surface, conducting scientific research during the agency’s Artemis campaign at the Moon and preparing for human missions to Mars.

The awards leverage NASA’s expertise in developing and operating rovers to build commercial capabilities that support scientific discovery and long-term human exploration on the Moon. NASA intends to begin using the LTV for crewed operations during Artemis V.

“We look forward to the development of the Artemis generation lunar exploration vehicle to help us advance what we learn at the Moon,” said Vanessa Wyche, director of NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston. “This vehicle will greatly increase our astronauts’ ability to explore and conduct science on the lunar surface while also serving as a science platform between crewed missions.”

NASA will acquire the LTV as a service from industry. The indefinite-delivery/indefinite-quantity, milestone-based Lunar Terrain Vehicle Services contract with firm-fixed-price task orders has a combined maximum potential value of $4.6 billion for all awards.

Each provider will begin with a feasibility task order, which will be a year-long special study to develop a system that meets NASA’s requirements through the preliminary design maturity project phase. The agency will issue a subsequent request for task order proposal to eligible provider(s) for a demonstration mission to continue developing the LTV, deliver it to the surface of the Moon, and validate its performance and safety ahead of Artemis V. NASA anticipates making an award to only one provider for the demonstration. NASA will issue additional task orders to provide unpressurized rover capabilities for the agency’s moonwalking and scientific exploration needs through 2039.

The LTV will be able to handle the extreme conditions at the Moon’s South Pole and will feature advanced technologies for power management, autonomous driving, and state of the art communications and navigation systems. Crews will use the LTV to explore, transport scientific equipment, and collect samples of the lunar surface, much farther than they could on foot, enabling increased science returns.

Between Artemis missions, when crews are not on the Moon, the LTV will operate remotely to support NASA’s scientific objectives as needed. Outside those times, the provider will have the ability to use their LTV for commercial lunar surface activities unrelated to NASA missions.

“We will use the LTV to travel to locations we might not otherwise be able to reach on foot, increasing our ability to explore and make new scientific discoveries,” said Jacob Bleacher, chief exploration scientist in the Exploration Systems Development Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “With the Artemis crewed missions, and during remote operations when there is not a crew on the surface, we are enabling science and discovery on the Moon year around.”

NASA provided technical requirements, capabilities, and safety standards needed for LTV development and operations, and the selected companies have agreed to meet the key agency requirements. The contract request for proposal required each provider to propose a solution to provide end-to-end services, including LTV development, delivery to the Moon, and execution of operations on the lunar surface.

Through Artemis, NASA will send astronauts – including the first woman, first person of color, and its first international partner astronaut – to explore the Moon for scientific discovery, technology evolution, economic benefits, and to build the foundation for crewed missions to Mars. Advanced rovers, along with the agency’s SLS (Space Launch System) rocket and Orion spacecraft, commercial human landing systems and next-generation spacesuits, and Gateway are NASA’s foundation for deep space exploration.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

HPHM OC Profile: Calliope Black

"No matter what anybody tells you, words and ideas can change the world."

Name: Calliope Antigone Black

Nicknames: Callie

Birthdate: October 31st, 1972

Zodiac Sign: Scorpio

Blood Status: Pureblood

Nationality: British

Sexuality: Bisexual

Callie is not the MC, she's just an OC that attends Hogwarts at the same time as Jacob's Sibling! She's open for friendships and rivalries, etc.

Physical Appearance

Hair: Dark brown

Eyes: Blue

Height: 1.60cm (5 ft 3½)

Weight: 53kg

Skin Tone: Fair

Faceclaim: India Eisley

Background

Home: Raven Hall, a modest (by rich people standards) property owned by the Black family in rural England

Family

Mother: Cressida Black, née Rowle

Cressida is a Slytherin alumni. She works at the Wizengamot and leads a seemingly successful life. On the inside, she's struggling though. She's not happy with her life and her unhappiness is affecting her relationship with her daughter. She loves Callie but is misguided in her efforts to make her choices for her and attempt to keep her in line.

Father: Castor Black, the younger brother of Orion Black

Castor attended Hogwarts as a Slytherin. He's unlike most of his family members in that he is softer and less likely to spout blood-purist rhetoric. However, he is not close with his daughter and his marriage to Cressida is facing some difficulties. He has constantly lived in the shadow of his older brother and doesn't know how to stand up to him.

Uncle: Orion Black

Cousins: Sirius Black, Regulus Black, Bellatrix Lestrange, Andromeda Tonks, Narcissa Malfoy

Hogwarts

House: Ravenclaw (hat stall with Slytherin)

Career

11-17: Hogwarts Student

17->: tbd

Personality & Attitude

Callie is the quiet sort who prefers the company of books to people. She doesn't go out of her way to make friends and can often seem cold or even rude to people who don't know her, but she's quite friendly once you manage to break through her surface. Deep down, she feels very alone due to her parents being distant and being an only child. She struggles with creating meaningful connections but craves them deeply.

She responds best to speaking of common interests, like books or music. She's a little bit clueless about the Muggle world and finds learning about Muggle culture fascinating. Callie is creative and sometimes scribbles poetry in the margins of her essays or in little notebooks. She doesn't have ambitions to become a poet as a fulltime job, though.

Priorities: Friends, gaining knowledge, independence

Strengths: Clever, works well under pressure, loyal to loved ones

Weaknesses: A bit of a loner, a penchant for melancholy, can come off as rude

Stressed: When dealing with her family or studying for exams

Calm/Comforted: With her friends and in the library

Favorites

Colors: Black

Weather: Rain

Hobbies: Reading, writing poetry, Wizard chess

Fashion: Business casual, blacks and grays, some grunge vibes

Relationships

Significant Other/Love Interest: Talbott Winger

Callie and Talbott have been house mates since year one, but they only really started to speak during year 4, when Callie got her pet owl Orpheus and started to spend time in the Owlery. They both enjoy a comfortable silence and the quiet comfort of each others' company.

The two started dating during year 6. They were together until graduation, after which they broke up for a while but reconnected during the Second Wizarding War. They married and have one daughter together.

Friends:

Talbott Winger

Badeea Ali

Murphy McNully

Matthew Luther by @hphmmatthewluther

Vienna Brokenshire, Jules Farrier, and Azariah Steele by @cursebreakerfarrier

Cato Reese by @catohphm

Eirlys Knell by @cursedlegacies

Dimitri and Skylar Di Angelo by @nicos-oc-hell

Caiden Solace by @camillejeaneshphm

Isabelle Dubois by @endlessly-cursed

Ruth Lyman, Huck Fitzgerald, Ryan, Cara, Sara, and Conor O'Donnell by @unfortunate-arrow

Marti Venturi by @smarti-at-smogwarts

OPEN FOR INTERACTION!

Rivals:

Merula Snyde (indirectly)

Children:

Thalia Winger

Talia was born in 1997. She's a Gryffindor and a Quidditch chaser.

Trivia

Callie likes to follow Quidditch although she doesn't talk about it because it clashes with her intellectual bookworm loner brand.

She has an owl called Orpheus

She has fond memories of her cousins Sirius and Regulus

#hphm#hogwarts mystery#hphm oc#oc: calliope black#oc profile#hp oc#the black family#she's open for friends!

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

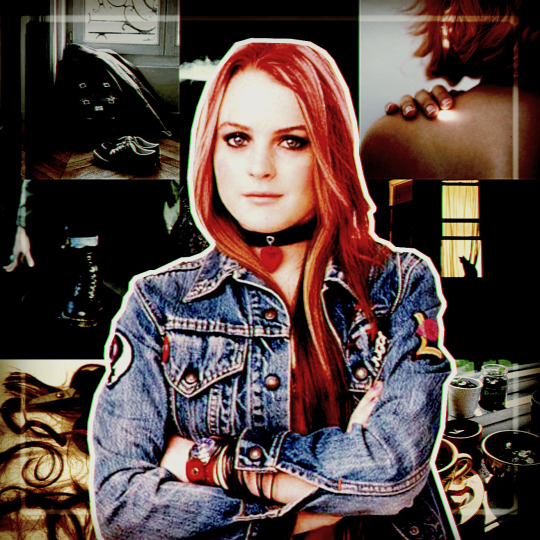

Full Name: Elisabeth Marigold Parker

Nicknames: Lizzie (everyone); Liz; Lisa (by Jacob)

Birthday: July 29, 1973

Zodiac: Leo

Blood Status: half-blood

Gender Identity: who even knows at this point (mostly goes by she/they)

Sexuality: bisexual

Nationality: British

Hometown: Maidstone, Kent, England

PERSONALITY

Myers-Briggs Type: ENFJ (The Protagonist)

Alignment: Chaotic Neutral

Strengths: intelligent, ambitious, loyal, honest, creative

Weaknesses: competitive, stubborn, hot-headed

Interests/Hobbies: researching, writing, duelling

APPEARANCE

Faceclaim: Lindsay Lohan

Voiceclaim: Ciara Baxendale

Height: 5ft 6in / 167cm

Build: average

Hair: red

Eyes: green

Skin: pale, freckled

Body Modifications: pierced ears, several tattoos

Scars/defects: multiple small scars on her hands, wrists and thighs; chipped left ear

Fashion:

WITCHCRAFT

1st Wand: Aspen, Unicorn Hair, 12 inches, reasonably supple

Wand-quality aspen wood is white and fine-grained, and highly prized by all wand-makers for its stylish resemblance to ivory and its usually outstanding charmwork. The proper owner of the aspen wand is often an accomplished duellist, or destined to be so, for the aspen wand is one of those particularly suited to martial magic. Aspen wand owners are generally strong-minded and determined, more likely than most to be attracted by quests and new orders; this is a wand for revolutionaries.

2nd Wand: Red Oak, Unicorn hair, 11 inches, solid

You will often hear the ignorant say that red oak is an infallible sign of its owner’s hot temper. In fact, the true match for a red oak wand is possessed of unusually fast reactions, making it a perfect duelling wand.

Animagus Form: orange cat/european shorthair

Patronus: kneazle

Boggart: Jacob (later Rowan) saying she is cursed and blaming her for not being able to save their loved ones

Riddikulus: she listens to what they have to say instead of casting the spell

Amortentia

what do they smell like to others?: elderflower, cocoa, pine, hay

what do they smell?: butterbeer, floo powder, broom polish, mowed grass

Favorite Spells: Bombarda, Incendio

Misc. Magical Abilities: Apparition; Nonverbal Magic; Occlumency

HOGWARTS

House: Slytherin

Best Subject: History of Magic, DADA

Worst Subject: Potions

Third Year Options: Care of Magical Creatures, Astronomy, Divination

N.E.W.T.s: History of Magic, DADA, Transfiguration, Charms, Care of Magical Creatures, Herbology, Astronomy

Extracurriculars: Duelling Club (4th to 7th year)

Quidditch Position: Keeper (3rd to 7th year)

AFTER HOGWARTS

more of less tbd as of now

RELATIONSHIPS

Father: Anthony Parker

Mother: Perpetua 'Tilly' Parker (née Brokenshire-Rosier)

Half Brother: Jacob Mallow Parker

Pets: a toad named Roger

Dormmates: Merula Snyde; Ismelda Murk; Liz Tuttle; Jules Farrier @cursebreakerfarrier

Closest Friends: Rowan Khanna, Ben Copper, Bill Weasley, Andre Egwu, Jae Kim

Friends: Nymphadora Tonks, Tulip Karasu, Barnaby Lee, Charlie Weasley, Julian Bennett, Irena Janda; Jules Farrier, Azariah Steele, Margot Dawes, Will Scarborough, Kester Stagg @cursebreakerfarrier; Katriona Cassiopeia, Reid Van de Lune @kc-and-co; Marti Venturi @smarti-at-smogwarts; Ryan O'Donnell, Sara O'Donnell, Cara O'Donnell, Conor O'Donnell @unfortunate-arrow; Isabelle Dubois @endlessly-cursed; Lizzie Jameson @lifeofkaze; Cato Reese @catohphm

Love Interests: Jae Kim, Erika Rath

FAVORITES

Color: emerald green

Food: dark chocolate

Flower: lily of the valley

Drink: butterbeer

Book: Quidditch Through the Ages

Music: anything by Queen

Season: autumn

#hphm#lizzie parker#hogwarts mystery#jacob's sibling#character profile#slytherin#now this is a Christmas miracle if i ever saw one#still missing her career path tho#it only took like what 2 years to get it out there?

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

MUSE LIST.

(Will be added to as time goes on).

Derek Venturi (Michael Seater)

Stiles Stilinski (Dylan O'Brien)

Lydia Martin (Ellie Bamber)

Billy Loomis (Skeet Ulrich)

Stacey Copeland (Lili Reinhart)

Evan Copeland (Matthew Daddario)

Cadence Mitchell (Hailee Stienfield)

Seth Mitchell (Dylan O'Brien)

Owen Grant (Jack Falahee)

Anna Sawyer (Megan West)

Sadie Hawthorne (Dove Cameron)

Connor Russo (Matthew Gray Gubler)

Bennett Campbell (Crystal Reed)

Dakota Harper (Dylan O'Brien)

Rafael Vigara (Noah Centineo)

Savannah Grace (Renee Rapp)

Noah Davis (Jordan Fisher)

Scarlett Arnolds (Taylor Swift)

Meghan Cooper (Danielle Campbell)

Jeremy Lodge (Peyton Meyer)

Felicty St. James (Selena Gomez)

Landon Royce (Harrison Osterfield)

Quill McKeon (Alberto Rosende)

Lilith Balthory (Devory Jacobs)

Aphrodite Lafont (Leven Rambin)

Simon Lewis (Alberto Rosende)

Reggie Peters (Jeremy Shada)

Audrey Stevens (Katerina Tannenbaum)

Jesse Anderson (Jeremy Strong)

Willow Evans (Sabrina Carpenter)

Finn Langston (Chase Stokes)

Harper Finkle (Jennifer Stone)

Allison Watts (Danielle Rose Russell)

Henry Fox (Nicholas Galitzine - previously found on princehenrytheutterlydaft but because tumblr sucks he is moved here for now)

Siobhan Davis (Charli Wookey)

Katelyn Alvarez (Adria Arjona)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cultural Comment: Fifty Years of “Learning From Las Vegas”

The cool appraisal of Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi’s revolutionary book has a lot to inspire the architects of today.

— By Christopher Hawthorne | January 27, 2023

On the morning of January 10, 1969, thirteen graduate students gathered inside Yale’s Art and Architecture Building to give their final presentations in a studio led by the married architects Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi. The students had spent the previous semester studying the urban design of Las Vegas, including a ten-day visit to the city during which they sketched hotel façades, measured nighttime illumination levels on the Strip, and crashed the opening gala for the Circus Circus Casino while wearing thrift-shop formal wear.

The agenda for the day stretched for more than eleven hours, with presentations on each of the studio’s dozen research categories, several short films (one of them shot from a helicopter borrowed from Howard Hughes), and breaks for lunch and dinner. The experts who assembled to discuss the results—the jury, in art- and architecture-school parlance—included the prominent Yale architectural historian Vincent Scully (whose son, Daniel, was a student in the studio) and the writer Tom Wolfe, whose 1964 Esquire essay “Las Vegas (What?) Las Vegas (Can’t Hear You! Too Noisy) Las Vegas!!!!” was an inspiration for Scott Brown and Venturi.

The following week, Venturi wrote a letter of thanks to some of the jurors, alluding to some of the raised eyebrows that he and Scott Brown encountered while bringing a close study of billboards and casino layouts into the architectural academy: “We think it went well in general,” he told them, “but I am still a little unbelieving that some people can’t understand we just wanted to look at Las Vegas in a dead-pan way which is also a poetic way of long standing.”

The book that emerged from this research, “Learning from Las Vegas,” published by M.I.T. Press in the fall of 1972 and credited to Scott Brown, Venturi, and their teaching assistant Steven Izenour, turned fifty last year. While it remains among the four or five most influential books on twentieth-century American urban form—alongside Jane Jacobs’s “The Death and Life of Great American Cities” (1961), Rem Koolhaas’s “Delirious New York” (1978), and Mike Davis’s “City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles” (1990)—it has also never quite outrun the critique that Venturi identified in that letter, a criticism that begins with suspicion of the idea that Las Vegas could ever be a subject worthy of serious architectural study.

The Times review of “Learning from Las Vegas,” by Roger Jellinek, carried the following headline: “In Praise (!) of Las Vegas.” Certainly, the conventional wisdom by that point saw Las Vegas and cities like it—and urban sprawl generally—as a scourge. (The Times had used a nearly identical headline, “In Praise (!) of Los Angeles,” less than a year earlier, for Jellinek’s review of Reyner Banham’s “Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies.”) The architect and critic Peter Blake’s widely read 1964 book, “God’s Own Junkyard: The Planned Deterioration of America's Landscape,” saw evidence in the postwar commercial strip, with its jumble of gas stations and drive-ins, of “the decline, fall and subsequent disintegration of urban civilization in the United States.” The German philosopher Theodor Adorno made a similar argument (in similarly apocalyptic prose) in an essay called “The Schema of Mass Culture”: “The neon sentences which hang over our cities and outshine the natural light of the night with their own are comets presaging the natural disaster of society, its frozen death.”

Scott Brown and Venturi were certainly comfortable staking out a contrarian position; it was then, and long remained, their go-to move. “Learning from Las Vegas” prompted just the kind of polarized reaction they were aiming for. It dominated discussion within architectural circles and won praise from younger critics, like Paul Goldberger, who wrote in the Times that “the Venturis,” as they were sometimes called in those days, had, by giving Las Vegas so much attention, “infuriated other architects, fascinated students and made themselves perhaps the most controversial figures in American architecture today.” The book also reached an audience of general-interest readers, for whom it explained changes in American cities which were increasingly difficult to ignore but hadn’t yet been framed in such an engaging way. The book’s first run of two thousand copies quickly sold out, and it has stayed in print ever since.

But did “Learning from Las Vegas”—and the Yale studio that inspired it—really set out to praise the architecture and urbanism of the Strip? Or was it meant instead as a cautionary tale about sprawl, a phenomenon that could be seen at its “purest and most intense,” as the authors put it, in Las Vegas? The answer is both—and neither. What struck me when I went back to reread the book is how deliberately it works to collapse the distance, and therefore the distinction, between enthusiasm and skepticism, and ultimately between documentation and critique. Above all, “Learning from Las Vegas” argues for a curious and open-minded anti-utopianism, for understanding cities as they are rather than how planners wish they might be—and then using that knowledge, systematically and patiently won, as the basis for new architecture. “Learning from the existing landscape is a way of being revolutionary for an architect,” the authors wrote. “Not the obvious way, which is to tear down Paris and begin again, as Le Corbusier suggested in the 1920s, but another, more tolerant way; that is, to question how we look at things.”

Robert Venturi à la Magritte on the Las Vegas Strip, 1966.Photograph by Denise Scott Brown / Courtesy Venturi, Scott Brown, and Associates, Inc.

Scott Brown and Venturi first visited Las Vegas together in November of 1966, a year before they were married. The trip was her idea. A young widow from South Africa, Scott Brown had begun teaching at U.C.L.A.’s new School of Architecture and Urban Planning after earning a master’s degree from and serving on the faculty of the University of Pennsylvania, where she and Venturi met. At first, she thought that Los Angeles might make the most useful laboratory for studying the emerging urbanism of car-centric cities—for employing the analytical method that she self-deprecatingly called “town watching”—before realizing that Las Vegas offered a petri dish of more manageable size. “We rode around from casino to casino, dazed by the desert sun and dazzled by the signs, both loving and hating what we saw,” she recalled. “We were jolted clear out of our aesthetic skins.”

As is often the case when architects travel—especially architects who write—the jolt wasn’t simply a reaction to what they saw. It was also an electrifying realization that what they were seeing might be material, fodder for a potent follow-up to Venturi’s influential first book, “Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture.” (That book, published in 1966, argued that modern architecture, by stripping away references to earlier landmarks or design movements, had drained new buildings of nuance and verve in favor of “prim dreams of pure order.” It also looked ahead to some of the preoccupations of the Yale studio by asking, in a reference to the American city-making of the era, “Is not Main Street almost all right?”) What if the pair mined their ambivalence about Las Vegas, that feeling of “both loving and hating what we saw,” for insights about the state of the postwar American city?

The trip formed the basis for a 1968 Architectural Forum essay by Scott Brown and Venturi, titled “A Significance for A&P Parking Lots, or Learning from Las Vegas,” which gave rise to the studio and a formal book proposal. Scott Brown later suggested that “Learning from Las Vegas” wasn’t really about Las Vegas but instead about the broader “symbolism of architectural form,” and there is something to that notion. The book is preoccupied with the ways in which vernacular architecture in Las Vegas and places like it had begun to respond to the dominance of the car—and with how travelling by car through cities affects our understanding of speed, distance, and the information conveyed by signs of all kinds. “Is the sign the building or is the building the sign?” the authors ask. “These relationships, and combinations between signs and buildings, between architecture and symbolism, between form and meaning, between driver and the roadside are deeply relevant to architecture today and have been discussed at length by several writers. But they have not been studied in detail or as an overall system.”

Most architecture students over the years have read the shorter second edition of the book, a paperback published in 1977, but the 1972 large-format hardcover version is the livelier and more revealing document, if also the more contentious editorial product. It is divided into three parts. The first largely reproduces the Architectural Forum essay and includes a close study of the Strip’s architecture, signage, and street furniture. The second provides an analysis of how trends visible in Las Vegas relate to larger developments in architecture and urbanism. This section is anchored by a tribute to “ugly and ordinary” architecture, including a now famous distinction between buildings that are “ducks,” which is to say, commercial structures that take the shape of what they’re selling—a Mexican-food shop in Los Angeles resembling a giant tamale, for example—and those that are “decorated sheds,” or expediently made buildings that gain energy from signage and ornament. In short, the duck is a symbol; the decorated shed applies symbols to a more conventional architectural frame.

Many late-modern buildings, in Venturi and Scott Brown’s view, had become by the nineteen-sixties a species of duck, their flat roofs and spare geometry existing primarily to advertise their architectural loyalties—to sell stale International Style tamales, as it were. (As Ada Louise Huxtable put it in reviewing “Learning from Las Vegas” for The New York Review of Books, “The modern building has rejected decoration only to become one big decorative object in itself.”) Scott Brown and Venturi much preferred the decorated shed, in no small part because of the high-low frisson produced when sophisticated architects mixed straightforward design choices with ironic and over-scaled ones, as they themselves would do for the rest of their career.

The final third of the book is made up of a survey of design projects in the office of Venturi and Rauch (as their firm was then known), from 1965 to 1971. This section, whose advertorial tone will be familiar to regular readers of architecture monographs, was removed for the second edition. That edition also introduced an entirely different approach to graphic design. Scott Brown and Venturi clashed from the start with the head designer at M.I.T. Press, Muriel Cooper, who worked in the so-called Swiss style and had overseen a mammoth 1969 survey of the Bauhaus by Hans Wingler.

Much of Cooper’s design for the first edition of “Learning from Las Vegas” follows the modernist playbook to a T, with sans-serif typefaces, an unyielding five-column grid, and oceans of white space in which both text and undersized images swim. As Scott Brown later put it, “That our argument against Late Modern was couched in Late Modern graphics conveyed, to say the least, a mixed message—‘one irony too far,’ I said. We argued mightily with Muriel.”

At the same time, perhaps overcompensating for her reputation, Cooper also proposed an initial cover design, later modified, which included a bubble-wrap slip cover and was crowded with large text, busy to the point of being shouty. For Scott Brown and Venturi, this choice was altogether too much on the nose. “The cover as designed is absolutely unacceptable: leaving out questions of good or bad design, it is inappropriate,” they wrote, in a letter to Michael Connelly, the M.I.T. Press editorial director. “This is a serious study with a serious text and deserves a dignified conventional image. The shock must come from the contents inside the book.”

As Aron Vinegar notes in his excellent 2008 history, “I Am a Monument: On Learning from Las Vegas,” “Scott Brown was convinced that Cooper had given them a ‘Duck.’ Cooper was sure that that was what they wanted all along.” Scott Brown and Venturi persuaded Connelly to let them design the second edition themselves. Among other changes, this “small, cheap, readable” edition, in Scott Brown’s words, added a subtitle (“The Forgotten Symbolism of Architectural Form”) and featured a serif typeface, Baskerville, along with a discreet, even boring, cover. It also saw a bigger role, or at least more prominent credit, for Scott Brown: it included a preface signed only by her, and it removed the first edition’s “Note on Authorship and Attribution,” which had carried just Venturi’s name.

Roger Conover, the longtime executive editor for art and architecture at M.I.T. Press, hoped for years to reprint the first edition, which had remained something of a cult favorite among graphic designers. Scott Brown and Venturi always refused. This changed in 2015, when Conover, nearing retirement, approached Scott Brown to make one final try, not only promising her the chance to write the introduction for what is now known as “the facsimile edition” but also to give her, as he put it, “the last word in the case of any editorial differences.” (Venturi’s health was fading by this point; he died in 2018.) She agreed, settling some scores with Muriel Cooper in an essay that she titled “The Tyranny of the Template: The Graphic Design of the First Edition of Learning from Las Vegas.”

Venturi’s use of the word “dead-pan” in his letter to the Yale jurors—“we just wanted to look at Las Vegas in a dead-pan way which is also a poetic way of long standing”—was perhaps the most significant clue about what he and Scott Brown expected from the book’s design: something that was coolly above the fray (even while admiring so much about the fray), that didn’t try quite so hard or bear the signs of coming from any theoretical camp. This also reveals something important about their sources of inspiration. The Los Angeles artist Ed Ruscha, in particular, had by the mid-nineteen-sixties established an attentive but ostensibly nonjudgmental approach to photographing urban landscapes, including gas stations and apartment buildings, that Scott Brown would later refer to as “deadpanning.” The title of Ruscha’s best-known book, “Every Building on the Sunset Strip,” from 1966, is itself part of this approach, suggesting that by including “every building” he is not choosing or critiquing, just documenting.

Members of the Learning from Las Vegas Studio in front of the Stardust, 1968.Photograph courtesy Venturi, Scott Brown, and Associates, Inc.

When the students in the Yale course travelled west to Las Vegas, they stopped off first in Los Angeles and visited Ruscha’s studio, where they would have had a chance to learn how he captured his images of Sunset Boulevard by attaching a 35-mm. camera to the hood of his Ford. (They also spent a day at Disneyland.) A photo montage in “Learning from Las Vegas” is labelled “The Ed Ruscha elevation,” and one of the short firms produced for the Yale studio was called “Deadpan Las Vegas (or Three Projector Deadpan).”

“He was very sweet,” Scott Brown told me over the phone, of the visit to Ruscha’s studio. “The students did what they did best—they brought a case of beer and drank it together.”

Several other artists had been mining a similar vein for nearly a decade. Bernd and Hilla Becher began photographing the abandoned industrial buildings of Germany’s Ruhr region in the late nineteen-fifties, presenting them in a detached black-and-white style, and later shot the steel mills of Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, using the same technique. The actor and photographer Dennis Hopper took a well-known photo of a Standard Oil gas station in Los Angeles from inside a car, in the early sixties. In 1964, Donald Appleyard, Kevin Lynch and John R. Myer published “The View from the Road,” a book meant as a primer for the design of the rapidly expanding American highway network. The Los Angeles architect Frank Gehry first gained wide attention with a 1965 Melrose Avenue live-work studio for the graphic designer Lou Danziger, which was wrapped in plain stucco, aping the banal architecture around it.

It was not as though these artists and architects suddenly lost their powers of judgment. But if “deadpanning” was a pose, it was a strategic and timely one. The most direct way for up-and-coming designers to separate themselves from the modernist generation was to reject the idea of heroic gestures, of remaking cities from the ground up. As Hilar Stadler and Martino Stierli write in the introduction to “Las Vegas Studio: Images from the Archives of Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown,” “Venturi and Scott Brown’s approach was revolutionary precisely in its renunciation of the rhetoric of revolution in favor of focusing architectural thought and action on the here and now. . . . It is this insistence on the city as it actually is that is the lasting legacy of Learning from Las Vegas.”

Yet that legacy, in certain respects, is fading, even as Scott Brown herself, and the work that she did before teaming up with Venturi, has become the focus of new scholarship. (A symposium on her career and teaching methods, pegged to a new book of essays edited by Frida Grahn, will be held at the Yale School of Architecture on February 8th.) “Learning from Las Vegas” now finds itself, perhaps more so than at any time since its publication, out of step with the current tenor of architectural practice and criticism. According to Izzy Kornblatt, who is in the first year of a Ph.D. program in architectural history and theory at Yale, students now tend to know the book “only for its title and for the distinction it makes between ‘ducks’ and ‘decorated sheds.’ ” And it is precisely the book’s nonjudgmental framing, what younger architects might call its passivity, that is responsible for this attitude, particularly when it comes to the effects of unconstrained capitalism on city-making. Activism—in particular efforts to take on the climate crisis, racial inequities and exploitative labor practices—has returned to the fore in the profession, and for good reason. “To tear down Paris and begin again” is not so far, in spirit, from the current mood, even if the political goals of many young architects are quite different from those of the right-leaning Le Corbusier. An approach that begins with close observation and ends with highly literate if occasionally self-satisfied commentary on that observation—the Scott Brown and Venturi method—seems ill-equipped, these days, to change the world in all the depressingly vast ways that it needs changing. What good is town watching when the town is on fire?

This is not a new critique. The architectural historian and theorist Manfredo Tafuri dismissed Scott Brown and Venturi for what he called their “facile ironies.” Yet those twenty-first-century readers tempted to brush off “Learning from Las Vegas” as a neutral travelogue risk missing the real power of its analysis—and the ways in which its approach might make today’s architecture of activism and political urgency sharper and more effective. We forget it now, perhaps because the effort was so entirely successful, but the book’s larger goals went far beyond understanding the quickly growing cities of the American West. Scott Brown and Venturi also wanted to accelerate a changing of the guard in architecture. In that sense, the smoke screen of non-judgment allowed them to plausibly claim a kind of “Who, me?” innocence as they worked to make room for their own generation to start running things.

After all, their frustration wasn’t with the revolutionary nature of the modernist project so much as with how it had grown stagnant and pleased with itself. As they write in the acknowledgments of “Learning from Las Vegas,” “Since we have criticized Modern architecture, it is proper here to state our intensive admiration of its early period when its founders, sensitive to their own times, proclaimed the right revolution. Our argument lies mainly with the irrelevant and distorted prolongation of that old revolution today.”

It would be going too far to claim that “Learning Las Vegas” was organized fundamentally as a kind of Trojan horse, sneaking anti-establishment ideas (about, for example, all the ways that modernism and its leading practitioners had reached a dead end) into the academy in the guise of mere empiricism, of diagrams and measurement. But the book’s seeming impartiality does serve to disguise its cunning. The young architects of today, who have their own designs on upheaval—even if their goals are more urgent or politically ambitious than Scott Brown and Venturi’s—could learn a thing or two from the strategy that the couple and their students perfected a half century ago, not so much storming the barricades as walking calmly and determinedly around them, flashing a camera or sketch pad as a kind of all-access pass. The “right revolution” this time around, whether it’s founded on climate activism or an architecture of racial or economic justice, will only benefit from that kind of savvy. In more direct terms, some of the most exploitative and environmentally suspect examples of recent urban planning—see the recent World Cup host Qatar, for starters—still haven’t received anything near the level of analysis that “Learning from Las Vegas” brought to the Nevada desert. ♦

1 note

·

View note

Text

I really did start HPHM as a fun game to interact with others playing it and maybe writing practice and wound up having Feelings about my mcs family members at now o clock and also all the time huh

#what did i sign up for#see the things Marti has another brother born between her and Jacob#see the thing is this kid Lost His Older Brother and is now constantly hearing about his younger sister being in danger bc Plot#see the thing is he's constantly wondeirng if he'll lose someone else and he's llike 15#see the thing is im a fool and i did this to myself#this random shit#HPHM#MC Marti Venturi#ddfhds im stiill in year 1 to#What Am I In For lol

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two Hundred Fifty Things an Architect Should Know

by Michael Sorkin

1. The feel of cool marble under bare feet.

2. How to live in a small room with five strangers for six months.

3. With the same strangers in a lifeboat for one week.

4. The modulus of rupture.

5. The distance a shout carries in the city.

6. The distance of a whisper.

7. Everything possible about Hatshepsut’s temple (try not to see it as ‘modernist’ avant la lettre).

The Temple of Hatshepsut

8. The number of people with rent subsidies in New York City.

9. In your town (include the rich).

10. The flowering season for azaleas.

11. The insulating properties of glass.

12. The history of its production and use.

13. And of its meaning.

14. How to lay bricks.

15. What Victor Hugo really meant by ‘this will kill that.’

16. The rate at which the seas are rising.

17. Building information modeling (BIM).

18. How to unclog a Rapidograph.

19. The Gini coefficient.

20. A comfortable tread-to-riser ratio for a six-year-old.

21. In a wheelchair.

22. The energy embodied in aluminum.

23. How to turn a corner.

24. How to design a corner.

25. How to sit in a corner.

26. How Antoni Gaudí modeled the Sagrada Família and calculated its structure.

27. The proportioning system for the Villa Rotonda.

28. The rate at which that carpet you specified off-gasses.

29. The relevant sections of the Code of Hammurabi.

30. The migratory patterns of warblers and other seasonal travellers.

31. The basics of mud construction.

32. The direction of prevailing winds.

33. Hydrology is destiny.

34. Jane Jacobs in and out.

35. Something about feng shui.

36. Something about Vastu Shilpa.

37. Elementary ergonomics.

38. The color wheel.

39. What the client wants.

40. What the client thinks it wants.

41. What the client needs.

42. What the client can afford.

43. What the planet can afford.

44. The theoretical bases for modernity and a great deal about its factions and inflections.

45. What post-Fordism means for the mode of production of building.

46. Another language.

47. What the brick really wants.

48. The difference between Winchester Cathedral and a bicycle shed.

49. What went wrong in Fatehpur Sikri.

50. What went wrong in Pruitt-Igoe.

51. What went wrong with the Tacoma Narrows Bridge.

52. Where the CCTV cameras are.

53. Why Mies really left Germany.

54. How people lived in Çatal Hüyük.

55. The structural properties of tufa.

56. How to calculate the dimensions of brise-soleil.

57. The kilowatt costs of photovoltaic cells.

58. Vitruvius.

59. Walter Benjamin.

60. Marshall Berman.

61. The secrets of the success of Robert Moses.

62. How the dome on the Duomo in Florence was built.

Duomo in Florence

63. The reciprocal influences of Chinese and Japanese building.

64. The cycle of the Ise Shrine.

65. Entasis.

66. The history of Soweto.

67. What it’s like to walk down the Ramblas.

68. Back-up.

69. The proper proportions of a gin martini.

70. Shear and moment.

71. Shakespeare, et cetera.

72. How the crow flies.

73. The difference between a ghetto and a neighborhood.

74. How the pyramids were built.

75. Why.

76. The pleasures of the suburbs.

77. The horrors.

78. The quality of light passing through ice.

79. The meaninglessness of borders.

80. The reasons for their tenacity.

81. The creativity of the ecotone.

82. The need for freaks.

83. Accidents must happen.

84. It is possible to begin designing anywhere.

85. The smell of concrete after rain.

86. The angle of the sun at the equinox.

87. How to ride a bicycle.

88. The depth of the aquifer beneath you.

89. The slope of a handicapped ramp.

90. The wages of construction workers.

91. Perspective by hand.

92. Sentence structure.

93. The pleasure of a spritz at sunset at a table by the Grand Canal.

94. The thrill of the ride.

95. Where materials come from.

96. How to get lost.

97. The pattern of artificial light at night, seen from space.

98. What human differences are defensible in practice.

99. Creation is a patient search.

100. The debate between Otto Wagner and Camillo Sitte.

101. The reasons for the split between architecture and engineering.

102. Many ideas about what constitutes utopia.

103. The social and formal organization of the villages of the Dogon.

104. Brutalism, Bowellism, and the Baroque.

105. How to dérive.

106. Woodshop safety.

107. A great deal about the Gothic.

108. The architectural impact of colonialism on the cities of North Africa.

109. A distaste for imperialism.

110. The history of Beijing.

Beijing Skyline

111. Dutch domestic architecture in the 17th century.

112. Aristotle’s Politics.

113. His Poetics.

114. The basics of wattle and daub.

115. The origins of the balloon frame.

116. The rate at which copper acquires its patina.

117. The levels of particulates in the air of Tianjin.

118. The capacity of white pine trees to sequester carbon.

119. Where else to sink it.

120. The fire code.

121. The seismic code.

122. The health code.

123. The Romantics, throughout the arts and philosophy.

124. How to listen closely.

125. That there is a big danger in working in a single medium. The logjam you don’t even know you’re stuck in will be broken by a shift in representation.

126. The exquisite corpse.

127. Scissors, stone, paper.

128. Good Bordeaux.

129. Good beer.

130. How to escape a maze.

131. QWERTY.

132. Fear.

133. Finding your way around Prague, Fez, Shanghai, Johannesburg, Kyoto, Rio, Mexico, Solo, Benares, Bangkok, Leningrad, Isfahan.

134. The proper way to behave with interns.

135. Maya, Revit, Catia, whatever.

136. The history of big machines, including those that can fly.

137. How to calculate ecological footprints.

138. Three good lunch spots within walking distance.

139. The value of human life.

140. Who pays.

141. Who profits.

142. The Venturi effect.

143. How people pee.

144. What to refuse to do, even for the money.

145. The fine print in the contract.

146. A smattering of naval architecture.

147. The idea of too far.

148. The idea of too close.

149. Burial practices in a wide range of cultures.

150. The density needed to support a pharmacy.

151. The density needed to support a subway.

152. The effect of the design of your city on food miles for fresh produce.

153. Lewis Mumford and Patrick Geddes.

154. Capability Brown, André Le Nôtre, Frederick Law Olmsted, Muso Soseki, Ji Cheng, and Roberto Burle Marx.

155. Constructivism, in and out.

156. Sinan.

157. Squatter settlements via visits and conversations with residents.

158. The history and techniques of architectural representation across cultures.

159. Several other artistic media.

160. A bit of chemistry and physics.

161. Geodesics.

162. Geodetics.

163. Geomorphology.

164. Geography.

165. The Law of the Andes.

166. Cappadocia first-hand.

Cappadocia

167. The importance of the Amazon.

168. How to patch leaks.

169. What makes you happy.

170. The components of a comfortable environment for sleep.

171. The view from the Acropolis.

172. The way to Santa Fe.

173. The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

174. Where to eat in Brooklyn.

175. Half as much as a London cabbie.

176. The Nolli Plan.

177. The Cerdà Plan.

178. The Haussmann Plan.

179. Slope analysis.

180. Darkroom procedures and Photoshop.

181. Dawn breaking after a bender.

182. Styles of genealogy and taxonomy.

183. Betty Friedan.

184. Guy Debord.

185. Ant Farm.

186. Archigram.

187. Club Med.

188. Crepuscule in Dharamshala.

189. Solid geometry.

190. Strengths of materials (if only intuitively).

191. Ha Long Bay.

192. What’s been accomplished in Medellín.

193. In Rio.

194. In Calcutta.

195. In Curitiba.

196. In Mumbai.

197. Who practices? (It is your duty to secure this space for all who want to.)

198. Why you think architecture does any good.

199. The depreciation cycle.

200. What rusts.

201. Good model-making techniques in wood and cardboard.

202. How to play a musical instrument.

203. Which way the wind blows.

204. The acoustical properties of trees and shrubs.

205. How to guard a house from floods.

206. The connection between the Suprematists and Zaha.

207. The connection between Oscar Niemeyer and Zaha.

208. Where north (or south) is.

209. How to give directions, efficiently and courteously.

210. Stadtluft macht frei.

211. Underneath the pavement the beach.

212. Underneath the beach the pavement.

213. The germ theory of disease.

214. The importance of vitamin D.

215. How close is too close.

216. The capacity of a bioswale to recharge the aquifer.

217. The draught of ferries.

218. Bicycle safety and etiquette.

219. The difference between gabions and riprap.

220. The acoustic performance of Boston Symphony Hall.

Boston Symphony Hall

221. How to open the window.

222. The diameter of the earth.

223. The number of gallons of water used in a shower.

224. The distance at which you can recognize faces.

225. How and when to bribe public officials (for the greater good).

226. Concrete finishes.

227. Brick bonds.

228. The Housing Question by Friedrich Engels.

229. The prismatic charms of Greek island towns.

230. The energy potential of the wind.

231. The cooling potential of the wind, including the use of chimneys and the stack effect.

232. Paestum.

233. Straw-bale building technology.

234. Rachel Carson.

235. Freud.

236. The excellence of Michel de Klerk.

237. Of Alvar Aalto.

238. Of Lina Bo Bardi.

239. The non-pharmacological components of a good club.

240. Mesa Verde National Park.

241. Chichen Itza.

242. Your neighbors.

243. The dimensions and proper orientation of sports fields.

244. The remediation capacity of wetlands.

245. The capacity of wetlands to attenuate storm surges.

246. How to cut a truly elegant section.

247. The depths of desire.

248. The heights of folly.

249. Low tide.

250. The Golden and other ratios.

938 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marti & Jacob Venturi ⍚ The Best Day

I grew up in a pretty house and I had space to run

And I had the best days with you

#my edits#my mcs#mc marti venturi#my jacob#jacob venturi#wake up babes new Marti/Venturi song unlocked lmao#blame the yt algorithim its been playing it on my way to work lol#listen i just love them#before R Jacob and Marti are ust..ver soft#and sometimes i exist to coo at soft things

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Harry Potter Ocs

Hphm Era:

Name: Martha -Marti- Beatrice Venturi

Story: Smarti At Smogwarts

Faceclaim: Emily Rudd

Summary: Being Jacob Venturi’s sibling sucks. That’s the lesson Marti’s learning. From the moment she got to Hogwarts there’s been gossip about her, about her missing brother, and about the cursed vaults. To say nothing of how certain people ( both teachers and students) treat her or how much her brother’s disappearance still hurts her. Still Marti’s determined to have a good time and make her own story at Hogwarts with friends Rowan and Ben.

Of course she didn’t count on the cursed vaults being real and for everything else that followed their reappearance.

Follows the gameplay of HPHM

More about her can also be found at hphm blog Smarti At Smogwarts

Golden Era

Name: Lucinda Aguilar-Palmero

Story: tbd

Faceclaim: Madison Reyes

Summary: Ever since moving to London for her father’s job Lucinda Aguilar-Palmero has been adapting. She’s adapted to separating from her cousins and extended family. She’s adapted to a different language. She’s adapted to a different climate and different foods and different...everything. An she likes to think she’s done so with very little complaining.

So when she finds out she has to move again this time alone and to a castle in Scotland because of the magic in her blood she thinks she’s entitled to complain a little bit.

Oh yeah, and there’s a flippin war.

Name: Suzette-Suzy- Macallister.

Story: tbd

Faceclaim: Aislinn Paul

Summary: tbd

HPHL Era

Name: Theodosia Jane Abott

Story: tbd

Faceclaim: Saoirce Ronan

Summary: Theo Abott was the product of a pureblood’s “indiscretion” with a muggleborn wizard. Something her very pureblood family has never let her forget. They kept her, fed her, made sure she knew the proper way for an Abott to act, but there was no affection to this and Theo sometimes wondered if it wasn’t only out of duty that her family did all this. After it becomes obvious that Theo who dresses in boy’s clothes, never keeps a comment inside her mind, and buckles against the propriety forced upon her more and more as the years pass is not going to be changing to fit what her family thinks she should be; it’s decided to send her to Hogwarts where she’ll at least be kept out of sight. ( and hopefully out of trouble)

She’s out of sight alright, but out of trouble...not so much.

*More about her can also be found at Smarti At Smogwarts

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

I've been thinking about Marti's friendship with the quads and like she'd totally be furious about Snape's treatment of Connor and probs bond with Ryan and Cara over quiditch. Also her and Cara are housemates owo. Oh also Marti has an older brother [ born between her and Jacob Venturi] in Ravenclaw so I can see her asking him to look out for Connor

I like this. Ryan, Cara, and Conor definitely really enjoy quidditch. And Snape’s just terrible, like he shows barely any respect to any of his students so mocking a stutter isn’t something too out of character for him. As long as Marti’s brother’s fathers subtle about it, Conor wouldn’t have too much of a pre-K men with it, he’s a very reserved, quiet, stubborn kid.

(Also, how would Marti react to Conor’s stutter?)

#HPHM#Hogwarts mystery#Ryan O’Donnell#Cara O’Donnell#Sara O’Donnell#Conor O’Donnell#O’Donnell quadruplets#Marti Venturi

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

TWO HUNDRED FIFTY THINGS AN ARCHITECT SHOULD KNOW

Michael Sorkin

1. The feel of cool marble under bare feet.

2. How to live in a small room with five strangers for six months.

3. With the same strangers in a lifeboat for one week.

4. The modulus of rupture.

5. The distance a shout carries in the city.

6. The distance of a whisper.

7. Everything possible about Hatshepsut’s temple (try not to see it as ‘modernist’ avant la lettre).

8. The number of people with rent subsidies in New York City.

9. In your town (include the rich).

10. The flowering season for azaleas.

11. The insulating properties of glass.

12. The history of its production and use.

13. And of its meaning.

14. How to lay bricks.

15. What Victor Hugo really meant by ‘this will kill that.’

16. The rate at which the seas are rising.

17. Building information modeling (BIM).

18. How to unclog a Rapidograph.

19. The Gini coefficient.

20. A comfortable tread-to-riser ratio for a six-year-old.

21. In a wheelchair.

22. The energy embodied in aluminum.

23. How to turn a corner.

24. How to design a corner.

25. How to sit in a corner.

26. How Antoni Gaudí modeled the Sagrada Família and calculated its structure.

27. The proportioning system for the Villa Rotonda.

28. The rate at which that carpet you specified off-gasses.

29. The relevant sections of the Code of Hammurabi.

30. The migratory patterns of warblers and other seasonal travellers.

31. The basics of mud construction.

32. The direction of prevailing winds.

33. Hydrology is destiny.

34. Jane Jacobs in and out.

35. Something about feng shui.

36. Something about Vastu Shilpa.

37. Elementary ergonomics.

38. The color wheel.

39. What the client wants.

40. What the client thinks it wants.

41. What the client needs.

42. What the client can afford.

43. What the planet can afford.

44. The theoretical bases for modernity and a great deal about its factions and inflections.

45. What post-Fordism means for the mode of production of building.

46. Another language.

47. What the brick really wants.

48. The difference between Winchester Cathedral and a bicycle shed.

49. What went wrong in Fatehpur Sikri.

50. What went wrong in Pruitt-Igoe.

51. What went wrong with the Tacoma Narrows Bridge.

52. Where the CCTV cameras are.

53. Why Mies really left Germany.

54. How people lived in Çatal Hüyük.

55. The structural properties of tufa.

56. How to calculate the dimensions of brise-soleil.

57. The kilowatt costs of photovoltaic cells.

58. Vitruvius.

59. Walter Benjamin.

60. Marshall Berman.

61. The secrets of the success of Robert Moses.

62. How the dome on the Duomo in Florence was built.

63. The reciprocal influences of Chinese and Japanese building.

64. The cycle of the Ise Shrine.

65. Entasis.

66. The history of Soweto.

67. What it’s like to walk down the Ramblas.

68. Back-up.

69. The proper proportions of a gin martini.

70. Shear and moment.

71. Shakespeare, et cetera.

72. How the crow flies.

73. The difference between a ghetto and a neighborhood.

74. How the pyramids were built.

75. Why.

76. The pleasures of the suburbs.

77. The horrors.

78. The quality of light passing through ice.

79. The meaninglessness of borders.

80. The reasons for their tenacity.

81. The creativity of the ecotone.

82. The need for freaks.

83. Accidents must happen.

84. It is possible to begin designing anywhere.

85. The smell of concrete after rain.

86. The angle of the sun at the equinox.

87. How to ride a bicycle.

88. The depth of the aquifer beneath you.

89. The slope of a handicapped ramp.

90. The wages of construction workers.

91. Perspective by hand.

92. Sentence structure.

93. The pleasure of a spritz at sunset at a table by the Grand Canal.

94. The thrill of the ride.

95. Where materials come from.

96. How to get lost.

97. The pattern of artificial light at night, seen from space.

98. What human differences are defensible in practice.

99. Creation is a patient search.

100. The debate between Otto Wagner and Camillo Sitte.

101. The reasons for the split between architecture and engineering.

102. Many ideas about what constitutes utopia.

103. The social and formal organization of the villages of the Dogon.

104. Brutalism, Bowellism, and the Baroque.

105. How to dérive.

106. Woodshop safety.

107. A great deal about the Gothic.

108. The architectural impact of colonialism on the cities of North Africa.

109. A distaste for imperialism.

110. The history of Beijing.

111. Dutch domestic architecture in the 17th century.

112. Aristotle’s Politics.

113. His Poetics.

114. The basics of wattle and daub.

115. The origins of the balloon frame.

116. The rate at which copper acquires its patina.

117. The levels of particulates in the air of Tianjin.

118. The capacity of white pine trees to sequester carbon.

119. Where else to sink it.

120. The fire code.

121. The seismic code.

122. The health code.

123. The Romantics, throughout the arts and philosophy.

124. How to listen closely.

125. That there is a big danger in working in a single medium. The logjam you don’t even know you’re stuck in will be broken by a shift in representation.

126. The exquisite corpse.

127. Scissors, stone, paper.

128. Good Bordeaux.

129. Good beer.

130. How to escape a maze.

131. QWERTY.

132. Fear.

133. Finding your way around Prague, Fez, Shanghai, Johannesburg, Kyoto, Rio, Mexico, Solo, Benares, Bangkok, Leningrad, Isfahan.

134. The proper way to behave with interns.

135. Maya, Revit, Catia, whatever.

136. The history of big machines, including those that can fly.

137. How to calculate ecological footprints.

138. Three good lunch spots within walking distance.

139. The value of human life.

140. Who pays.

141. Who profits.

142. The Venturi effect.

143. How people pee.

144. What to refuse to do, even for the money.

145. The fine print in the contract.

146. A smattering of naval architecture.

147. The idea of too far.

148. The idea of too close.

149. Burial practices in a wide range of cultures.

150. The density needed to support a pharmacy.

151. The density needed to support a subway.

152. The effect of the design of your city on food miles for fresh produce.

153. Lewis Mumford and Patrick Geddes.

154. Capability Brown, André Le Nôtre, Frederick Law Olmsted, Muso Soseki, Ji Cheng, and Roberto Burle Marx.

155. Constructivism, in and out.

156. Sinan.

157. Squatter settlements via visits and conversations with residents.

158. The history and techniques of architectural representation across cultures.

159. Several other artistic media.

160. A bit of chemistry and physics.

161. Geodesics.

162. Geodetics.

163. Geomorphology.

164. Geography.

165. The Law of the Andes.

166. Cappadocia first-hand.

167. The importance of the Amazon.

168. How to patch leaks.

169. What makes you happy.

170. The components of a comfortable environment for sleep.

171. The view from the Acropolis.

172. The way to Santa Fe.

173. The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

174. Where to eat in Brooklyn.

175. Half as much as a London cabbie.

176. The Nolli Plan.

177. The Cerdà Plan.

178. The Haussmann Plan.

179. Slope analysis.

180. Darkroom procedures and Photoshop.

181. Dawn breaking after a bender.

182. Styles of genealogy and taxonomy.

183. Betty Friedan.

184. Guy Debord.

185. Ant Farm.

186. Archigram.

187. Club Med.

188. Crepuscule in Dharamshala.

189. Solid geometry.

190. Strengths of materials (if only intuitively).

191. Ha Long Bay.

192. What’s been accomplished in Medellín.

193. In Rio.

194. In Calcutta.

195. In Curitiba.

196. In Mumbai.

197. Who practices? (It is your duty to secure this space for all who want to.)

198. Why you think architecture does any good.

199. The depreciation cycle.

200. What rusts.

201. Good model-making techniques in wood and cardboard.

202. How to play a musical instrument.

203. Which way the wind blows.

204. The acoustical properties of trees and shrubs.

205. How to guard a house from floods.

206. The connection between the Suprematists and Zaha.

207. The connection between Oscar Niemeyer and Zaha.

208. Where north (or south) is.

209. How to give directions, efficiently and courteously.

210. Stadtluft macht frei.

211. Underneath the pavement the beach.

212. Underneath the beach the pavement.

213. The germ theory of disease.

214. The importance of vitamin D.

215. How close is too close.

216. The capacity of a bioswale to recharge the aquifer.

217. The draught of ferries.

218. Bicycle safety and etiquette.

219. The difference between gabions and riprap.

220. The acoustic performance of Boston Symphony Hall.

221. How to open the window.

222. The diameter of the earth.

223. The number of gallons of water used in a shower.

224. The distance at which you can recognize faces.

225. How and when to bribe public officials (for the greater good).

226. Concrete finishes.

227. Brick bonds.

228. The Housing Question by Friedrich Engels.

229. The prismatic charms of Greek island towns.

230. The energy potential of the wind.

231. The cooling potential of the wind, including the use of chimneys and the stack effect.

232. Paestum.

233. Straw-bale building technology.

234. Rachel Carson.

235. Freud.

236. The excellence of Michel de Klerk.

237. Of Alvar Aalto.

238. Of Lina Bo Bardi.

239. The non-pharmacological components of a good club.

240. Mesa Verde National Park.

241. Chichen Itza.

242. Your neighbors.

243. The dimensions and proper orientation of sports fields.

244. The remediation capacity of wetlands.

245. The capacity of wetlands to attenuate storm surges.

246. How to cut a truly elegant section.

247. The depths of desire.

248. The heights of folly.

249. Low tide.

250. The Golden and other ratios.

https://www.readingdesign.org/

1 note

·

View note

Text

IDENTITY

Full Name: Julian Xander Bennett

Birthday: 8th March 1973

Gender: Male

Species: Human

Blood Status: Pureblood

Sexuality: Bisexual

Alignment: True Neutral

Ethnicities: English, Greek

Nationality: British

Residence: Nottingham, East Midlands, England

Myer Briggs Personality Type: ESTP - The Entrepreneur

THE MAGE

Wand: Ash, curupira hair, 12 inches, Slightly springy

Misc. Magical Abilities: Seer; Wandless & Nonverbal magic; Apparition;

Animagus: N/A

Boggart Form: his parents saying that they didn’t want him and that’s why they left

Riddikulus Form: his parents start to dance ridiculously to some upbeat disco music

Amortentia (What do they smell like?): apple, hay, butterscotch, wood

Amortentia (What do they smell?): lavender, brewed coffee, wood, coconut

Patronus: Lynx

Patronus Memory: his mother singing him to sleep when he was six

Mirror of Erised: he’s with his parents and aunt and they’re all happy

APPERANCE

Faceclaim/Voiceclaim: Joe Keery

Height: 5ft 9inch (175cm)

Physique: Athletic

Eye Colour: Gray; turn gold when he has a vision

Hair Colour: Brown, with some reddish highlights under a warm lighting

Skin Tone: Fair

Body Modifications: N/A

Scarring: small scar on his right eyebrow; not exactly a scar but he has a visible bump on his nose since he broke it as a child

Inventory (what do they carry on them?): wand, spare change, at least one hair tie, pack of gums, tissues, sunglasses, a notebook or a piece of parchment, pencils

PERSONALITY

loyal, courageous, emphatic, protective, kind, creative, confident, strong, energetic, positive, cooperative, polite, gentle

ALLEGIANCES

Hogwarts House: Gryffindor

Affiliations/Organisations: Gryffindor House; Gryffindor Quidditch team; Circle of Khanna; Gringotts Wizarding Bank; the Order of the Phoenix

Professions:

11 — 18: student at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry

18 — 30: Cursebreaker for Gringotts Wizarding Bank

30+: Freelance Cursebreaker

HOGWARTS INFORMATION

Class Proficiencies (most to least):

Flying, Muggle Studies, Care of Magical Creatures, Defence Against the Dark Arts, Herbology, Divination, Transfiguration, Charms, Astronomy, History of Magic, Potions,

Quidditch: Beater (fourth to seventh year)

Extra Curricular: TBD

Favourite Professors: McGonagall; Kettleburn; Trelawney

Least Favourite Professors: Snape; Binns

RELATIONSHIPS

Mother: Daphne Bennett (née Hall) - deceased (probably)

Father: Walter Bennett - deceased (probably)

Aunt: Cassandra “Cassie” Bennett

[FC: Goldie Hawn]

Love Interest: Clary Walcott (@that-ravenpuff-witch)

Canon Friends: Bill & Charlie Weasley; Tulip Karasu; Nymphadora Tonks; Barnaby Lee; Diego Caplan; Jae Kim; Chiara Lobosca; Murphy McNully

MC Friends: Clary Walcott and Henry McClarnon (@that-ravenpuff-witch); Ottilie Reyes (@words-and-wands); Marti and Jacob Venturi (@smarti-at-smogwarts); Feen McKenzie and Atlas Marson (@cleverglitteryfoxtrot);

Enemies: Merula Snyde

Dormmates: Ben Copper; Charlie Weasley; Jae Kim; Henry McClaron

Pets: a rat named Ozzy (male)

BACKGROUND

He was born in England to a pureblood father and half-blood mother, he was an only child. His childhood was mostly happpy and he grew up showing signs of magical abilities. At the age of four he had his first vision in a dream, it wasn’t very clear and he couldn’t understand it but he felt that it wasn’t a good thing. His mother reassured him then that it was just nightmares. Because both of his parents were aurors, working for the Order of the Phoenix, they would often leave him on Walter’s sister’s — Cassie — supervision. She was an unusual character but little Julian kinda admired her wierdness.

His entire world changed over just one summer when Julian was six years old. His parents left him with Cassie again, promising they’d be back just in time to take him on a vacation trip they’ve been talking about for the past few weeks. So he waited for them for days, turned weeks, turned months. They never came back. Although he knew that they wouldn’t left him, and that something terrible must have happened he was still unsure whether that was the case. The fact that absolutely nobody seemed to know what really happened to them wasn’t helping.

Probably the darkest time of his short life begin. He was taken away from his aunt, because the authorities stated that she’s not capable of rasing him. Then he was passed from home to home, nearly put in an orphanage for good. His visions were starting to become more intrusive and he started to experience them even when he was awake. He wouldn’t understand what’s happening to him and he also was physically unable to not to say what he saw. People around them whether it was other kids or adults were really disturbed by things he were saying due to the fact that his visions were mostly about bad stuff that were going to happen.

Almost a year later it was reaveled to him that Cassie was actively trying to get the custody over him and he eventually succeeded. After a horrible time of not being wanted by anybody he was finally reunited with the one person he actually trusted. He went back to live with Cassie and things finally started looking good for him. His aunt quickly noticed that he can experience the visions the near future and tried to explain it to him. She was an incredible help for him in understanding what all of that means and she could understand what he was going trough, because she was given the same ability.

By the time he was eleven and his letter from Hogwarts came, he could much better understand how to deal with all the things he was seeing. Although he couldn’t control when the vision would come or what he would see, he managed to distance himself from it and have a lot better coping mechanisms after the things he saw were dark or traumatic.

LAST UPDATE: 11.01.2021 — things added: MC friends, love interest, dormmate, amortentia smell, pet

#honestly he popped up in my head out of nowhere#but i love him lol#i wanted to make a seer mc for a while now#so i am pretty proud of him and his story#i was so torn whether to put him in gryffindor or slytherin#but i guess i have a soft spot for dorky gryffindor boys lol#also i have now way too much gryffindor ocs i need to fix it#hphm#julian bennett#and now i’m off to go reblog all the stuff i didn’t while i was working on julian#hogwarts mystery#character profile#hogwarts mystery mc

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books

Here is the list of architecture books I am planning to read (in the next few years heheh)

A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction / Christopher Alexander, Sara Ishikawa, Murray Silverstein

The Architecture of the City / Aldo Rossi

Athmospheres / Peter Zumthor

Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture / Robert Venturi

Conversations with Students (Architecture at Rice) / Louis Kahn

Experiencing Architecture / Eiler Rasmussen

In Praise of Shadows / Junichiro Tanizaki

Learning from Las Vegas / Denise Scott Brown, Robert Venturi, Steven Izenour

Mutations / Rem Koolhaas, Stefano Boeri, Sanford Kwinter, Nadia Tazi, Hans Ulrich Obrist

Neufert Architects' Data / Ernst Neufert, Peter Neufert

The Poetics of Space / Gaston Bachelard

The Seven Lamps of Architecture / John Ruskin

Superstudio: Life without objects / Peter Lang

The Works: Anatomy of the City / Kate Ascher

Yona Friedman: The Dilution Of Architecture / Yona Friedman

Archigram / Peter Cook

BIG, HOT TO COLD: An Odyssey of Architectural Adaptation / Bjarke Ingels

Cities for People / Jan Gehl

Forensic Architecture: Violence at the Threshold of Detectability / Eyal Weizman

The Future Of Architecture / Frank Lloyd Wright

Isay Weinfeld: The Brazilian Architect / Gestalten

Kicked a Building Lately? / Ada Louise Huxtable

Slow Manifesto / Lebbeus Woods Blog

SMLXL / Rem Koolhaas

Thinking Architecture / Peter Zumthor

Uneasy Balance / Christopher Platt, Brian Carter

Yes is More / Bjarke Ingels

Invisible Cities / Italo Calvino

The Pillars of the Earth / Ken Follet

Project Japan: Metabolism Talks / Rem Koolhaas, Hans Ulrich Obrist

Architecture As Space / Bruno Zevi

Architecture Depends / Jeremy Till

The Architecture of Image: Existential Space in Cinema / Juhani Pallasmaa

Are We Human? Notes On Archeology Of Design / Beatriz Colomina

BLDGBLOG Book / Geoff Manaugh

The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change / David Harvey

Constructing a New Agenda: Architectural Theory 1993-2009 / A. Krista Sykes

Content / Rem Koolhaas

Delirious New York: A retroactive manifesto for Manhattan / Rem Koolhaas

The Destruction of Memory: Architecture at War / Robert Bevan

Future Practice: Conversations from the Edge of Architecture / Rory Hyde

The Good Life: A Guided Visit to the Houses of Modernity / Iñaki Ábalos

The Language of Architecture / Andrea Simitch and Val Warke

The Manual of Section / Paul Lewis, Marc Tsurumaki, and David J. Lewis

Oppositions Reader: Selected Essays 1973-1984 / Michael Hays

Pornotopia: An Essay on Playboy's Architecture and Biopolitics / Beatriz Preciado

The Structure of the Ordinary: Form and Control in the Built Environment / N.J. Habraken

Theoretical Anxiety and Design Strategies in the Work of Eight Contemporary Architects / Rafael Moneo

Why Architecture Matters / Paul Goldberger

Cities for a Small Planet / Richard Rogers

The City of Tomorrow: Sensors, Networks, Hackers, and the Future of Urban Life / Carlo Ratti, Matthew Claudel

Cities Without Ground / Adam Frampton, Jonathan D. Solomon, Clara Wong

Collage City / Colin Rowe and Fred Koetter

Concise Townscape / Golden Cullen

The Death and Life of Great American Cities / Jane Jacobs

The Granite Garden: Urban Nature And Human Design / Anne W. Spirn

The History of the City / Leonardo Benevolo

Ladders / Albert Pope

Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space / Jan Gehl

The New Science of Cities / Michael Batty

Triumph of the City / Edward Glaeser

The Urban Apparatus: Mediapolitics and the City / Reinhold Martin

Walkscapes: walking as an aesthetic practice / Francesco Careri

Liquid Modernity / Zygmunt Bauman

Non Places / Marc Auge

#architecture#archibooks#archiread#archistudy#architecture student#reading#self-help books#books#book#library

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

TWO HUNDRED FIFTY THINGS AN ARCHITECT SHOULD KNOW

Michael Sorkin

1. The feel of cool marble under bare feet.

2. How to live in a small room with five strangers for six months.

3. With the same strangers in a lifeboat for one week.

4. The modulus of rupture.

5. The distance a shout carries in the city.

6. The distance of a whisper.

7. Everything possible about Hatshepsut’s temple (try not to see it as ‘modernist’ avant la lettre).

8. The number of people with rent subsidies in New York City.

9. In your town (include the rich).

10. The flowering season for azaleas.

11. The insulating properties of glass.

12. The history of its production and use.

13. And of its meaning.

14. How to lay bricks.

15. What Victor Hugo really meant by ‘this will kill that.’

16. The rate at which the seas are rising.

17. Building information modeling (BIM).

18. How to unclog a Rapidograph.

19. The Gini coefficient.

20. A comfortable tread-to-riser ratio for a six-year-old.

21. In a wheelchair.

22. The energy embodied in aluminum.

23. How to turn a corner.

24. How to design a corner.

25. How to sit in a corner.

26. How Antoni Gaudí modeled the Sagrada Família and calculated its structure.

27. The proportioning system for the Villa Rotonda.

28. The rate at which that carpet you specified off-gasses.

29. The relevant sections of the Code of Hammurabi.

30. The migratory patterns of warblers and other seasonal travellers.

31. The basics of mud construction.

32. The direction of prevailing winds.

33. Hydrology is destiny.

34. Jane Jacobs in and out.

35. Something about feng shui.

36. Something about Vastu Shilpa.

37. Elementary ergonomics.

38. The color wheel.

39. What the client wants.

40. What the client thinks it wants.

41. What the client needs.

42. What the client can afford.

43. What the planet can afford.

44. The theoretical bases for modernity and a great deal about its factions and inflections.

45. What post-Fordism means for the mode of production of building.

46. Another language.

47. What the brick really wants.

48. The difference between Winchester Cathedral and a bicycle shed.

49. What went wrong in Fatehpur Sikri.

50. What went wrong in Pruitt-Igoe.

51. What went wrong with the Tacoma Narrows Bridge.

52. Where the CCTV cameras are.

53. Why Mies really left Germany.

Upto #53 ready reckoner here: https://adamachrati.wordpress.com/category/sorkin-250/

54. How people lived in Çatal Hüyük.

55. The structural properties of tufa.

56. How to calculate the dimensions of brise-soleil.

57. The kilowatt costs of photovoltaic cells.

58. Vitruvius.

59. Walter Benjamin.

60. Marshall Berman.

61. The secrets of the success of Robert Moses.

62. How the dome on the Duomo in Florence was built.

63. The reciprocal influences of Chinese and Japanese building.

64. The cycle of the Ise Shrine.

65. Entasis.

66. The history of Soweto.

67. What it’s like to walk down the Ramblas.

68. Back-up.

69. The proper proportions of a gin martini.

70. Shear and moment.

71. Shakespeare, et cetera.

72. How the crow flies.

73. The difference between a ghetto and a neighborhood.

74. How the pyramids were built.

75. Why.

76. The pleasures of the suburbs.

77. The horrors.

78. The quality of light passing through ice.

79. The meaninglessness of borders.

80. The reasons for their tenacity.

81. The creativity of the ecotone.

82. The need for freaks.