#Ichirō Itano

Text

エンジェルコップ (1989-1994) dir. Ichirō Itano

#angel cop#Ichirō Itano#anime#manga#aesthetic#retro anime#anime gif#anime aesthetic#japan#japanese#80s#80s anime#90s anime#90s

657 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Angel Cop (1988) ED

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Animation Night 168: when Anno was young...

Animation Night has been getting kind of short lately, huh? Gone are the days when we'd marathon three films in a night... for now. Next week is Animation Night 169, and @mogsk has been helping me cook up quite a program to act as a sequel to Animation Night 69. It's time to find out just how much Twitch will let me get away with.

But what about tonight? Well, tonight I figure since we've been talking about Anno this week, it might be fun to put a short program together to show some of his earlier works - as an animator. Truly long-time viewers might remember watching Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honneamise and Gunbuster all the way back on Animation Night 29. But this isn't exactly a reprise of that. We'll revisit Gunbuster on another day. Tonight the subject will be Metal Skin Panic: Madox-01 and Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honneamise.

So here's a brief timeline (largely leaning on SteveM's video here lol). Anno's work on the Daicon III film got him a foot in the door in the industry by impressing Studio Nue enough to invite the Daicon III team to work on Macross. Nue were also in large part fans turned animators, many of them Gundam doujinshi artists. Anno joined what became known as the 'mecha unit' at Artland, working alongside the legendary Ichirō Itano - where he was known for walking around barefoot and talking loudly to himself. A couple of years after Daicon III, the Daicon team reassembled to create a followup film, a lavish effort packed with a ludicrous density of pop-culture references.

Not long after this... Anno dropped out of university, and started bouncing between animation studios in Tokyo. The next big break came when he applied to work on Miyazaki's Nausicaa, a production which was rapidly transforming the outsourcing-oriented studio Topcraft into a gathering of some of the best animators in the business. At Topcraft, Anno's reputation was 'the primal man', sleeping under his desk with the cockroaches and not wearing shoes. But despite his inexperience, he made a good impression on Miyazaki, who assigned him the crucial finale cuts of the God Warrior.

Here we see what is sometimes called the 'Anno explosion', where the laser sweeps across and a massive explosion follows after a beat. Anno was able to handle the complex shading and multiple layers with aplomb...

...if not entirely on schedule. (One anecdote has that he tried to use his work on this sequence to pick up women. Which, to be fair...)

So in the mid 80s, Anno has established himself as a skilled mecha animator who can handle some ludicrously technical scenes. Besides Nausicaa and Macross, you will see him in Megazone 23 Part I, Giant Robo: The Animation, Baoh, Birth - and even Grave of the Fireflies. Any time you wanted mechanical animation or explosions, Anno was definitely a guy to get on the phone. And of course one of his most significant projects was on SDF Macross: Do You Remember Love? where he animated... you guessed it, lots of missiles and explosions.

With all this experience under his belt, Anno was almost ready to return to the newly founded Gainax - what had been Daicon Film. But first - lets check out Metal Skin Panic! MADOX-01. This OVA, made at AIC and Artmic - who made so many of the classic OVAs from this period, it's nuts - was the directorial debut of Shinji Aramaki, whose later CG films we covered back on Animation Night 152. Even back in 1987, Aramaki's love of intricate mechanical detail was on full display - and luckily Anno was on hand to make that vision work, along with the even younger 14-year-old prodigy Kōji Akimoto. (I'm not entirely sure what became of Akimoto. He only has one other anime credit, much later.)

Anno's scenes here prefigure the later similar hyper-detailed mechanical animation in works like Patlabor 2. But what's this OVA actually about? Well, it's a pretty simple story: a mechanic gets trapped inside a mecha suit, and accidentally ends up on a rampage as he's chased by the military (remind you of Roujin Z? or Stink Bomb in Memories?), hoping to unite with his girlfriend Shiori. Ultimately he ends up in a confrontation with an American soldier Lieutenant Kilgore. They fight! Really, we're here for the animation.

So, that brings us to Royal Space Force. The origin is kinda messy. To make a long story short, Daicon Film approached Bandai, hoping to make an OVA based on new Gundam kits. Bandai (and more specifically Shigeru Watanabe) said no to Gundam, but they were interested in this idea for a scifi OVA - and they'd drop them a cool three and a half million dollars to make a film to rival Nausicaa. (Apparently Mamoru Oshii's approval played a big part in that).

So Royal Space Force, what a film. There truly isn't anything quite like it, either in Gainax's oeuvre or anime at large. The closest thing I could compare it to might be the near-future anime series Planetes, which similarly focuses on realistic spaceflight in the context of war and geopolitics - but the tone of these two stories is markedly different. Of all things, it actually most makes me think of the works of Le Guin.

Honneamise is set on a fictional world vaguely resembling eartly 20th Century Earth, in which a country embroiled in war is putting together its world's first, threadbare space programme. It follows aspiring astronaut Shirotsugh Ladatt, who missed his chance to be a pilot and ended up in the sideshow space programme. But he meets a religious girl named Riquinni Nonderaiko who convinces him of the potential of spaceflight in bringing peace to the world.

But this idealism clashes with the reality of a world where the space programme is viewed cynically, a means to an end, with protestors questioning the cost of it and the higherups seeing the rocket launch merely as a means to set up an ambush against their enemies. Shirotsugh increasingly doubts whether the space programme is worthwhile at all. And he himself is definitely not a fully sympathetic protagonist; in one particularly uncomfortable scene he attempts to rape Riquinni (which in its framing reminds me of a similar moment with Shevek in The Dispossessed).

The film is as much as anything an insane work of worldbuilding, full of constructed cultures and small details that sit just a little askew of Earth while still feeling incredibly grounded. The animation in this film is fucking insane - not just Anno's incredible rocket launch and flight sequences, based on a research trip to the States where he watched the Shuttle go up for real - but throughout, in its character animation, it anticipates the 90s 'realist' approach to stylisation. It's just full of loving detail, wordlessly conveying so much about its setting.

Of course, such an ambitious film faced a troubled production. Between the inexperience of Daicon Film Gainax and the difference between what this film was going for and what everything else was going for, and production meddling... it was a mess. Big name composer Ryuichi Sakamoto was pulled in to score the film, won over by its storyboards, but ended up clashing over the timing of scenes, and in the end his score was chopped up and rearranged.

And for their part, Bandai started getting antsy and attempted to impose changes, like insisting on tacking on the subtitle 'The Wings of Honneamise'. They wanted to cut the runtime, cut elements that didn't have toy potential, and so on. They wanted something that would sell toys... and got a deliberately slow, moody art film that leans heavily on nonverbal storytelling.

So it's a weird one... and it didn't sell in its theatrical run. But you know, all those elements that made it a hard sell at first are a perfect recipe for 'cult classic', and for that reason, Honneamise is still remembered today.

In any case, back to Anno. He delivered the most impressive animation of his career. The rocket launch in meticulous detail of course, but equally scenes of planes to rival any in Miyazaki's films (or The Cockpit [AN146]). Of course, he didn't carry it alone! The great realist Toshiyuki Inoue, who'd later be famous for his work at Production I.G. such as Ghost in the Shell, was on it, working for example on astonishingly busy crowd scenes which apparently took a full month to animate. And animators like Fumio Iida, Nobuteru Yuki and Noriasu Yamauchi, brought some of the best work they'd ever done.

All in all, there's nothing quite like Royal Space Force, before or since. So I'm really looking forward to seeing it again.

Animation Night 168 will go live shortly; films will begin at 11pm UK time and continue to about 2am UK time. (Apologies it's so late once more, my sleep is proving troublesome to shift.) We will as usual be at twitch.tv/canmom. I hope to see you there, it's gonna be a real sakuga feast tonight!!

#animation night#anime#animation#hideaki anno#royal space force: the wings of honneamise#metal skin panic: madox-01

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

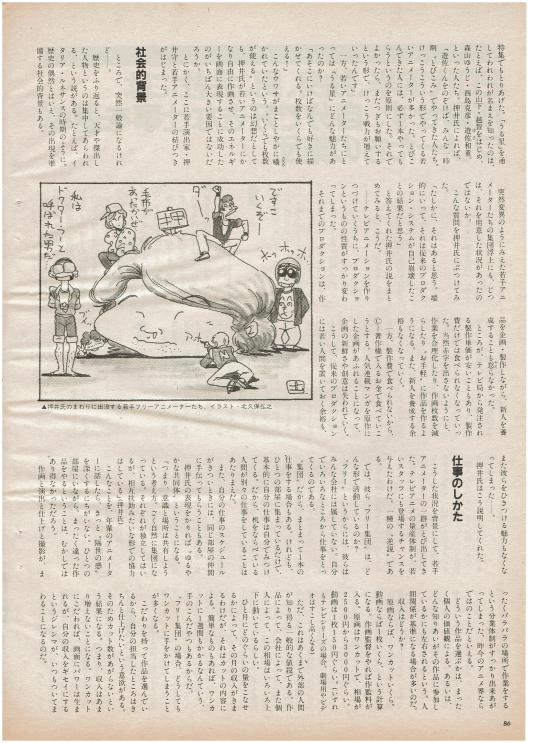

Here is the entire piece from Animage for December 1984

The main focus is on

Hideaki Anno

Ichirō Itano

Hiroyuki Kitakubo

Masahito Yamashita

Yuji Moriyama

With the last page being Mamoru Oshii talking about the group of animators.

#hideaki anno#ichiro itano#hiroyuki kitakubo#masahito yamashita#yuji moriyama#mamoru oshii#animation#anime#animage

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

07/12/2019: still Love doing these, I re watched the uncut version of 'Angel Cop' ep 1 - 6. The vhs tapes back in the 90s when you either rent or buy back then, those versions were cut. The scenes that were cut were violent sequences. Watch it now with the lens of 2024, you'll love the HD versions. Both versions, Japanese or English dubs are still worthy.

Enjoy everyone

ref: Angel Cop is a six-part original video animation created and directed by Ichirō Itano. A manga adaptation written and illustrated by Taku Kitazaki was serialized in Newtype in 1989 and collected into a Newtype 100% collection released in April 1990. - Wikipedia

Adapted from: Angel Cop

Episodes: 6

Music by: Hiroshi Ogasawara

Runtime: 30 minutes

Studio: DAST

Software: Adobe Photoshop & Illustrator CS3

Tools: wacom pen

#Angel Cop#anime#manga#vector#illustration#khuan tru#photoshop#fan art#london#pen tool#fan drawing#pen drawing#anime and manga

0 notes

Text

L'art book del 40º anniversario di Macross presenta una nuova copertina illustrata da Ichirō Itano

Il secondo volume della Macross Super Encyclopedia uscirà nel 2024.

Info:--> https://www.gonagaiworld.com/lart-book-del-40o-anniversario-di-macross-presenta-una-nuova-copertina-illustrata-da-ichiro-itano/?feed_id=405496&_unique_id=6526436489db1

#Artbook #IchirōItano #Macross #マクロス

0 notes

Text

Angel Cop | エンゼルコップ

Original Release: September 1, 1989 – May 20, 1994

40 notes

·

View notes

Photo

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Interview with Toshihiro Hirano and Ichirō Itano (Macross, Iczer One, Megazone 23...).

(Animage, 01/1986)

238 notes

·

View notes

Text

FEATURE: How I Got Into Sakuga

Kaiba, Directed by Masaaki Yuasa

If you’re an anime fan, you’re likely an animation fan in general. But how do you know when an animation is “good”? How do you learn to identify an animator by only what you see, or tell when their drawings are better than usual?

English-speaking anime fans have adopted sakuga as a general catch-all term for exceptional animation. While the word sakuga itself means “animation,” in this context, sakuga has come to mean something very specific: Not just animation that looks cool, but the deliberate handiwork of specific animators with specific artistic aspirations. For example, a single-animator project might have a lot of “sakuga shots” because it has a personal, highly-refined style. Meanwhile, a television series might have an entire team of varying specialists for a larger narrative. Some of this might be attributed to specific key animators, while some might be credited to an entire studio — transformation sequences, explosive missiles, robots — that’s all fair game to be called sakuga. But how do you really know if what you’re looking at really is this so-called “sakuga?”

Like most art, it’s almost entirely subjective. Here’s my story.

Project A-ko, a high-energy 1986 OVA series best remembered for its exceptional animation staff

(Image via Retrocrush)

All’s Fair in Love and War Games

When I was a kid, I got my hands on the English-dubbed Digimon: The Movie on VHS. This notorious release was a three-part recut of Mamoru Hosoda’s Digimon OVAs released from 1999 to 2000, heavily featuring his second film Digimon Adventure: Our War Game. Of course, I didn’t experience this package as a “Hosoda anime” at the time. Besides the inspired inclusion of Barenaked Ladies’ "One Week" to the soundtrack, I strongly associate these films with Hosoda’s signature interpretation of Katsuyoshi Nakatsuru’s original Digimon Adventure character designs. Compared to the Toei-produced television series, these renditions of the Digi-Destined are charmingly off-model and move with awkward intention, like actual kids up against terrifying monsters.

In a sense, that’s what most people mean by sakuga — animation that makes us lean in and notice traits about the world and characters that can’t be communicated otherwise. Sakuga, in particular, places special emphasis on an individual animator’s keyframes, or the drawings used as a basis for in-between frames during movement. That’s what I mean by the phrase “Hosoda anime.” If you watch Summer Wars or The Girl Who Leapt Through Time enough times, anyone will notice a stylistic palette of idiosyncrasies.

Digimon Adventure “Home Away From Home” directed by Mamoru Hosoda

(Image via Hulu)

An Emerging Style

When I got older and realized there was more anime than what was on cable, I kept returning to “flat” style animation with films like Tatsuo Satō’s 2001 Cat Soup and Shōji Kawamori’s 1996 Spring and Chaos. Around this time, contemporary artist Takashi Murakami also began developing his own “superflat” style (coined in his 2000 book Superflat and later in Little Boy: The Arts of Japan's Exploding Subculture) we’ll return to. Once I got a taste for the experimental, I never turned back.

But back to Hosoda. Less focused on the details of models and more fixated on a “flat” or fluid style of movement, the key animation in Hosoda’s films makes body language a priority. This is perhaps the best thing about good sakuga — its potential to express deep emotion even under production constraints. My favorite example comes from the first Digimon short film Hosoda directed, the simply titled Digimon Adventure from 1999.

Keep Your Hands Off Eizouken!, Directed by Masaaki Yuasa

Originally conceived as a standalone for Bandai’s then-new Digital Monsters virtual pet toys, this version of Digimon is less loud, more atmospheric — and sincerely preoccupied with the question: “How would little kids actually handle a giant monster of their own?” The result is an unforgettable shot of Kairi, Tai’s little sister desperately blowing her whistle, stopping to catch her breath, then spitting and coughing in an attempt to calm down their newly evolved kaiju Greymon friend.

For the television series, Hosoda directed the episode “Home Away From,” depicting the two siblings clinging to each other as the other slowly drifts back to the Digital World. In both scenes, characters don’t constantly move, but only act when necessary via careful manipulation of the frames. This technique not only makes everything seem more “realistic,” but also acts as a visual cue for the anxiety Tai and Kairi feel. In other words, painstakingly controlled animation serves both form and function, especially when you’re selling an emotional climax of another kid-meets-monster plot.

Tomorrow’s Joe, 1980 film adaptation of the 1970 TV anime series directed by Osamu Dezaki

(Image via Retrocrush)

A Little History Lesson

After Digimon, Hosoda and Nakatsuru collaborated on films like Summer Wars and the Takashi Murakami-inspired pop art short Superflat Monogram. Hosoda is no doubt inescapable to sakuga fans today thanks to the ubiquity of his feature films. Still, Hosoda obviously wasn’t the first sakuga animator. Animators like Yasuo Ōtsuka, known for his cinematic work in a pre-Ghibli era of anime film with Toei, documented the growth ‘60s and ‘70s of Japan’s animation industry in his 2013 book Sakuga Asemamire. When the demand for films lowered in favor of anime television during that era, animators took risks. Classics of the era like Tiger Mask and Tomorrow's Joe literally held no punches, and Osamu Tezuka’s own Mushi Productions dove headfirst into experimental adult films. Animators, and especially keyframe animators, had creative control. In this perfect storm, the advent of sakuga was inevitable.

Everyman Ken Kubo is taught the ways of eighties anime in Otaku no Video

(Image via Retrocrush)

Why Bother With Sakuga?

In 2013, animation aficionado Sean Bires and company hosted an informational panel titled “Sakuga: The Animation of Anime” at Anime Central Chicago. Uploaded to YouTube that same year, this panel informed my younger self’s understanding of not just the “how” of sakuga, but the “why” it even needed to exist in anyone’s vocabulary. Accessible, meticulously researched, and full of visual references, Sean’s two-hour panel-lecture does the heavy lifting of contextualizing anime not just through a historical lens, but within the broader project of expanding cinematic techniques. This primer might sound heady, but considering the popularity of Masaaki Yuasa’s series like Keep Your Hands Off Eizouken!, and references to animator Ichirō Itano’s “Itano circus” missiles in American cartoons like DuckTales, it’s hard to say sakuga isn't relevant. Nowadays, it's practically a trope to parody one of Dezaki's most iconic shots. Supplemented by a rich community of blogs and forums, it couldn’t be easier to learn about animators like Yasuo Ōtsuka or the early days of Toei if you want a bigger picture. Blogs like Ben Ettinger’s Anipages and the aptly named Sakuga Blog are a good place to start, not to mention dozens of dedicated galleries of anime production and art books published by studios themselves. Now couldn’t be a better time to vicariously live your art school dreams through anime masterworks.

Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland, a 1989 film featuring animation by Yasuo Ōtsuka best known for his work on the Lupin III franchise

Sakuga Is For Everyone

Fans have always been obsessed with the technicalities of animation, even if they weren't artists. As early as 2007, uncut dubbed collector box sets for Naruto came with annotated booklets of episode storyboards. More recently, critically-acclaimed series like Shirobako further explicated this love for animation as a team effort — people love attaching other people to art. In contrast, psychological horror series like Satoshi Kon’s Paranoia Agent features an episode about an anime studio’s production going terribly wrong. Not to mention the endlessly self-referential Otaku no Video Gainax OVA and its depiction of zealous sakuga otaku. Anime fans adore watching anime be born over and over. It’s that simple.

Digimon Adventure “Home Away From Home” directed by Mamoru Hosoda

(Image via Hulu)

Today, I’d comfortably call some shots from Hosoda Digimon films great sakuga. But Koromon is still weird. Sorry.

The love for sakuga isn’t a contest to one-up fans on production trivia or terminology. It’s about taking the time to appreciate the fact that anime is ultimately a collaborative artistic endeavor. From tracing back the lineage of animators like Yoshinori Kanada to Kill la Kill, to appreciating the visual sugar rush of Project A-Ko alongside slow-paced Ghibli films, “getting into sakuga” isn't a passive effort, nor a waste of time. Besides, wouldn't it be fun understanding how your favorite animator achieved your favorite scene? The phrase "labor of love" is cliché, but maybe that’s a good synonym for what role sakuga inevitably plays for artists and fans alike — work that brings you joy, no matter how you cut it.

Who is your favorite animator? When did you get into sakuga? Let us know in the comments below!

Blake P. is a weekly columnist for Crunchyroll Features. His twitter is @_dispossessed. His bylines include Fanbyte, VRV, Unwinnable, and more. He actually doesn't hate Koromon.

Do you love writing? Do you love anime? If you have an idea for a features story, pitch it to Crunchyroll Features!

By: Blake Planty

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Person actually said passion is more important in writing than making sense. Uh, Karen, some of us are passionate about things making sense. The whole appeal of science fiction and fantasy is to convey things you cannot experience, with a high degree of verisimilitude (an infinitely better word than “realism” for the desired quality).

The patron saint of this would be the Japanese animator Itano Ichirō, who used to sneak onto demolition sites so he could see how the dust actually moves when a building collapses. He’s the guy who did the key animation for the scene of all the flamingos taking off in Mobile Suit Gundam; I believe he also did the key animation of the iconic cockpit rescue from the first episode of Super Dimension Fortress Macross.

Most people’s SF gatling guns are Rule of Cool. Mine are because the parts of a coil gun experience a lot of wear, so there’s an incentive to rotate between them analogous to the one that created rotary firearms. Most androids that have fluid come out when damaged, do it purely for the aesthetic. Mine do it because they’re powered by metal-air batteries with a liquid base—which also gives them a reason to breathe.

You need to have things make sense, in order to convey what the phenomena in question are actually like. You’re not standing up for creativity, you’re just making excuses for white room syndrome.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Kaiju from SSSS Gridman (2018); Diriver designed by Ichirō Itano. Unlike the other artists mentioned here Itano is not known for designing kaiju. Itano began his career as an animator on the original 1981 Mobile Suit Gundam but gained notoriety for his work on the classic mecha anime series The Super Dimension Fortress Macross (1982) where he not only designed the iconic transforming jet-robots but also pioneered a unique style of aerial “dogfights” in which multiple missiles careen across the screen at once. This became known as the “Itano Sākasu” or “Itano Circus.” You can watch a video about it here. Itano has occasionally worked on tokusatsu, most notably Ultraman Nexus (2004). Fittingly the monster he designed for SSSS Gridman is the show’s only flying kaiju.

39 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Angel Cop | Ichirō Itano | 1989

Follow Rhade-Zapan for more visual treats

202 notes

·

View notes

Text

Animation Night 64: Macross

Tonight’s Animation Night hits a power of 2... which means it’s surely an apt time for giant robots! I figured that it would be a good time to check out a series with a looming reputation which I’ve yet to sample... Super Dimension Fortress Macross.

youtube

Macross is one of your old guard long-running mecha series, dating back to 1982 - not quite so prolific as Gundam, but definitely one of the heavyweights from that era. The product of Studio Nue, a team already well-respected for their design work on early mecha shows like Yamato and Gundam, Macross struck out in an unusual direction by framing its plot around the cross-cultural emotional power of pop music.

But what made it really stand out, at least if you ask a sakuga fan, was Ichirō Itano.

youtube

Itano is a fascinating guy: he. In terms of our sakuga history, he’s one of those early ‘charisma animators’ to get a personal reputation, and he was indeed directly inspired by Kanada (whose work we saw a couple weeks ago). His hallmark, as Sean Bires describes in that video, was an ingenious understanding of 3D space - getting the camera right up into the action, crossing over between different scales with the kind of shot that only animation can do: the camera flying from a closeup of the pilot in the cockpit of a spaceship out to a long dramatic shot of a battle, using changes of lens angle etc. to push the intensity further.

And more specifically, he created one of anime’s most enduring motifs: the Itano Circus. You’ve probably seen this kind of shot homaged in dozens of different shows: something shoots out a huge swarm of missiles (or magic rays, tentacles, etc.), and they arc and twist all around the camera before closing in on their target. Famously, the story goes that Itano devised this trick by strapping a bunch of fireworks to his motorbike and igniting them - and the experience of of moving in the middle of the swarm of fireworks as they floated around him in every direction affected him so profoundly that he was determined to capture it in animation.

And he sounds like a real character, too:

I’m pretty sure Ichiro Itano is going to punch me in the face.

It’s hard to tell, because I have a pair of opera glasses strapped to my head, the wrong way round, so that everything looks as if I am staring at it down the wrong end of a telescope. But in the round window of my vision, I very clearly see the director of Gantz, his hair tied back in a ponytail, his wiry muscles rippling under a khaki vest, hauling back his arm and then lurching right at me.

His fist speeds into view, looming huge in the frame. His arm seems to trail behind it for an impossible distance, while his hand blocks the entirety of my view. I stumble backwards, expecting a blow at any moment, but Itano has deliberately fallen a couple of inches short.

“Ha!” he says. “See? That’s what the world looks like if you’re the pilot of a giant robot! You’re looking through a viewscreen, you see. You’re not using your real eyes, you’re using a camera! And so, when we show a pilot’s-eye view in an anime show, we shoot it the way that a camera would see it!”

Although this story is told often, the inspiration to do such a thing isn’t mentioned - but apparently it was driven by a scene in Android Kikaider where a guy shoots a rocket from a motorbike. Funny coincidence with this week’s toku tuesday...

By the time of Macross, Itano had honed his particular style on classic Sunrise shows like the original Gundam and especially Space Runaway Ideon. Let me spare a few words about Ideon, incidentally - although somewhat overshadowed by Gundam, to its fans, Ideon is adored for its especially nihilistic tone: Gundam creator Yoshiyuki Tomino’s disgust with war manifesting in a series of abrupt and brutal deaths of every beloved character.

Sadly, it’s one I can’t really figure out how to cram into Animation Night: the compilation film is said to cut so much as to be markedly inferior to the series, there is a span of about 20 episodes that never made it into a film, and without the effort to get attached to the characters, the final film doesn’t feel like it would deliver in the same way.

Like who’s this girl? I bet if I knew, I’d be like oh god no...

Anyway, as far as ppl like Itano were concerned, Ideon was his opportunity to hone the ethos developed in Gundam into something more concrete, and redefine how mecha battles would be framed in film. But his project really reached fruition in Macross.

So what’s this all in service of? The narrative of Macross concerns an invasion by aliens called the Zentradi, an engineered warrior species who, unmoored from their creators, mindlessly conquer without any meaningful culture. Humanity only stands a chance thanks to one of the first idols in anime, Linn Minmay, whose music throws the Zentradi into confusion and leads some of them to defect. This leads to a whole sprawling series of robot battles, love triangles, and extensive discussion of soft power.

youtube

Or at least, so I’m advised by youtube user Zeria, who provides one of the few attempts I’ve encountered to break it down on a thematic level. In their words, its thesis could be taken as:

Hard power is necessary, vital, and ultimately moral, but it’s soft power that will always win the day, and as a result, it’s imperative that a benevolent state wields both.

So where does this fit in, historically? We’ve talked before about the massive societal transformations taking place in 80s Japan when we watched Akira. We could maybe say that in such conditions, in which the nation-entity called “Japan” was suddenly becoming one of the economically powerful players within the American cold war bloc, was facing a question of how it should use that power. And we could tie that into subsequent developments - indeed, while no aliens ignorant of music have shown up, the seemingly eternal right-wing government has attempted to direct soft power in its interests with policies like “Cool Japan”.

Zeria argues that, while the cut corners of the original TV production undermine its ability to push this theme, the first summary movie Do You Remember Love does an exceptional job of pushing its ‘yay soft power’ theme on a formal level:

...this move successfuly demonstrates in full the power of the culture it comes from. Every frame of this movie bombards the viewer with peak 80s Japanese aesthetics, begging them to agree that the economic rise of the nation is a good thing. (...)

That said, the film’s quality is only able to emerge from a unique point in time, a period when it was far easier for those in Japan to have faith that culture would inevitably win the day. It was a time where the widespread anxiety that Japan would ultimately overtake the West still had purchase in the minds of ordinary people, leading to the rise of cyberpunk. For a culture like that, the use of military might as a protective deterrent, with culture being the real showshopper, was not a strange idea.

I feel like the interplay between cultural productions like this and nationalist projects is not something I address really often enough on Animation Night posts (usually because I don’t start these soon enough to really get into that thorny subject). I certainly don’t think most anime producers are particularly strong nationalists, and many of them may be fiercely critical of Japan, the industry, capitalist system etc. ... but the existence of even subversive artworks attaches itself to the big ball of psychic imaginary force that is “a nation exists and is ‘like this’”, playing out in all sorts of ways in the behaviour of humans. For the kind of artist who hates her country and wishes to see it destroyed, how do you even sidestep that?

Well, I don’t know how to answer that, and in any case if I can trust Zeria, the creators of Macross had largely the opposite aim in mind. Fuckers. Let’s return to the robots... The robots of Macross are an early real-robot iteration on the ‘transforming robot’ concept: ‘variable fighters’ which can alternate between humanoid and fighter jet forms.

Though I linked this article by Sean O’Mara on the series’s robot design earlier, let’s talk more about it. The big names for Macross’s distinctive design language is Shoji Kawamori, who was there when the original Gundam developed the ‘real robot’ idea of mecha as simply being military equipment rather than mechanical superheroes. Kawamori, while competing with fellow Nue member Kazukaka Miyatake to design robots for a show called Genocidus (o.O steady on there), got the idea for a robot with "backwards” digitigrade legs after observing skiiers on a slope.

The concepts for Macross - a giant transforming space fortress, carrying a lot of smaller transforming space fighters inside it, slowly developed over other cancelled projects such as Battle City Megaroad. Part of the friction with the original Genocidus concepts was the difficulty of producing toys (the toy company apparently saying ‘make a humanoid robot, even if it just stands there), but it was also toy design that led to the return to this concept in Macross: it was easier to build a plane with drop down legs than a fully jointed figure.

One of Macross’ mechanical strengths was its variety, the result of the two talented designers working on it. While Kawamori focused on the svelte and aerodynamic VF-1, Miyatake created a range of designs from the chunky, non-transformable destroids that served as cannon fodder, to the show’s numerous spaceships.

Well, both the Super Dimension Fortress and Do You Remember Love proved major successes, and Macross was set to follow Gundam become a lasting giant robot franchise with multiple iterations slotting into a grander meta-series. The series was re-edited and dubbed for Americans under the title Robotech in 1985, alongside two other mecha anime, Super Dimension Cavalry Southern Cross and Genesis Climber MOSPEADA. But that’s all I’m going to say about that.

The next Macross entry, Flash Back 2012, is generally not so well remembered: an early OVA that relied heavily on recut footage and had a relatively thin narrative - though O’Mara makes a case for it. Another OVA sequel, Lovers Again, was made without the involvement of the original creators at Studio Nue, and would later be quietly dropped from continuity. It’s not until the 1990s that we get the next major entry into the series, the four episode OVA Macross Plus, which would then get recut into a movie with some extra reanimated footage.

If the original Macross was rooted in the capitalist optimism of the 80s, Plus has to adapt to the collapse of the bubble and the ‘lost decade’ of the 90s. How does it do that? ...uh well, I don’t actually have a handy video essay to tell me what to think on this one.

Hmm. Casting around. Hey, here’s someone’s thesis. ...OK, they go through this entire writeup without talking about prior Macross films, rather mostly drawing contrast with Akira and GitS, so I don’t know how far I can use this. (Reminds me that I still need to do some kind of writing poking into all the different flavour of GitS adaptation...) Also they totally missed what makes Tetsuo so great. Nevertheless, the major point raised by this article, which does seem to contrast to what we just claimed about SDF and DYRL, is an image of “statelessness” that’s created by... giving it a mostly American setting. I’m not convinced on that basis.

But it does connect us to the new director who appears at this point in Macross’s history... Shinichirō Watanabe, who would a few years later gain massive fame outside of Japan with works like Cowboy Bebop and Samurai Champloo - someone for whom heavy use of western and especially American cultural signifiers is, like, his entire main thing. So perhaps they’re onto something after all. How does this fit into a whole dialogue on states and soft/hard power proposed by Zeria? I don’t think I have enough information to say.

Instead, let’s talk about the premise. Macross Plus is set on a colony planet called Eden, focusing on a contest between two rival test pilots who find their future in the next generation of ‘variable fighters’ is threatened by a new AI-controlled fighter design. Only, that makes it vulnerable to, well, what if your AI super-idol goes evil and steals your slick new jet fighter? On a metaphorical level, I think I can imagine where we’re going with this.

The way @mogsk introduced me to this one, it sounds like Itano managed to outdo himself yet again on the animation department... I seriously cannot wait for the sakuga feast we have in mind. On that front, Macross Plus is the source of another incredible Itano anecdote:

“Let me put it like this,” he says. “There’s this flight school in America run by retired air force pilots. They’ll give you one lesson in really fast English, and one safety demonstration, and then they’ll take you up to 10,000 metres. You have a co-pilot, but he leaves it to you once you’re up. So it was me and Shoji Kawamori, in jets, ready for a dogfight. All as part of the research for Macross Plus. I wanted to know what it was like to fly a plane, to be in aerial combat, and I was curious about G-force.

“Each plane had a laser pointer, and if you could keep the enemy in your sights for three seconds, you scored a hit. So we started the dogfight, chasing our tails. I scored six hits on Kawamori. He was all over the place, but I was really good!

“So after all that, I decided: ‘I’ve done the dogfight. Let’s faint.’ So I grabbed the joystick and pulled right back on it. I heard the pilot shouting ‘Itano! Itano-san! Mr Itano! NO! Stop!’ and the G-force pushed me back in the seat. I felt my head lolling and then there was black. I’d blacked out, and it was like someone had pulled the plug on a computer.

Upon landing, he was taken aside and told to draw storyboards for a blackout scene.

Plus would soon be followed by a long-running TV series Macross 7, with its own films; then as we hit the 2000s we get a whole cornucopia of prequels, interquels, videogame spinoffs et cetera to celebrate various anniversaries. I have no ability to tell you which ones are notable or good - should we find ourselves enjoying Macross, perhaps we could pick out a few somewhere down the line.

As for Itano, Gen Urobuchi apparently relates that after a motorbike accident that injured his hand, Itano was no longer able to paint (I presume they mean draw keyframes?), and turned his efforts to directing and training new animators instead. In this role, he directed a number of very gory OVA projects like Battle Royal High School (the source of one of my favourite clips, I must watch the whole thing some time), and adapted Go Nagai in Violence Jack: Evil Town and the first anime take on Gantz - I can’t say if it’s a great adaptation, but the manga, for all its flaws and questionable narrative decisions, does hold a certain place in my heart as one of the first really edgy gory mangas I read.

Perhaps another one of these nights we can check out Itano-the-director. What I hear about these projects is that they’re extremely uneven: often cutting corners with photography in many cuts, but with a few really unique and groundbreaking scenes every now and then.

Unfortunately, Itano also takes the blame for directing and and co-writing Angel Cop, a late 80s-early 90s series about an extrajudicial police unit fighting communists which somehow abruptly swerves into cartoonishly nonsensical antisemitic conspiracy theory. I have no way to explain that; the best that can be said is that it was a complete turkey, with Itano’s name being the only reason it is remembered at all.

Macross is definitely one of the big holes in my knowledge of classic 80s anime, and from the sound of it, it’s going to be a great time and maybe provoke some kind of interesting discussions. Or maybe we’ll just meme, you never know. In any case, tonight, my plan is to show the Do You Remember Love film, and then the ‘movie edition’ of Plus. I may also try to find some clips from Ideon that show Itano’s development. Animation Night 64 is starting at 7pm UK time at twitch.tv/canmom - see you there!

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

animarchive: Interview with Toshihiro Hirano and Ichirō Itano... https://ift.tt/2JBftnr

0 notes

Photo

5 notes

·

View notes