#I went to a predominantly white school and university and it’s hard explaining to a group of white people the type of agony of not ever

Text

Tw:internalized racism? I guess?

#sorry I’m not answering asks right now Daisy is just. laying in bed feeling the sad sjsjsjsjsjsj#having self respect is easy. it’s having self love that’s the hard part.#my friends are gorgeous and pretty and so smart and amazing but it’s.#I can’t talk to them about how frustrating it is to be I guess the non-ideal poc?#they’re either white with straight noses and colored eyes or Asian and are able to hang out with and relate to other Asians#for me I don’t. have that Sjsjsjs I’m#a Lightskin or whatever but I don’t fit any of the black niches nor am I accepted by them bc I am nawt black enough for their ideals etc#so it just. leaves me feeling isolated#I went to a predominantly white school and university and it’s hard explaining to a group of white people the type of agony of not ever#really being the ideal race if that makes sense?#like if I like a guy I have to worry about oh well does he find black girls attractive would he be willing to date outside his race#bc for the record black guys do not. treat me nicely and berate me for not idk being their Rihanna baddie so I just have been so turned off#from them I don’t think I could ever date a black guy tbh#it gets even more nerve wracking when you’re a 21 year old virgin and your mom is just shoving black guys down your throat to date sjsjsjsj#but even if they say oh you’re pretty you’re gorgeous Daisy etc I just. can’t believe them bc they will always be the first choice. I won’t#and that just. it destroys me and eats away at me bc being different only works when you fit in#*sigh* I have no black people to talk about this to bc my sister is thicker skinned than I am I guess and my mom would just say just date#a black guy or get black friends when ✨they don’t even desire me✨#so I rant to my little tumblr blog and hope these feelings pass even tho I’ve been feeling this for about two months now#I cried during my graduation bc I couldn’t feel proud of myself and felt so demoralized. I graduated with a degree in biomedical sciences#and never had I felt more worthless#but sigh sorry lovies for posting this I just. aksksk I’m crying now argh but yah#Daisy is sad but hopefully I will answer asks tomorrow I see them#all and yall are so sweet 💕

1 note

·

View note

Text

Marvel’s Spider-Man: Miles Morales story and character review

So let’s state a disclaimer, I didn’t like the PS4 Miles character as it was blatantly clear that they never read a Miles story with the actual mistakes they made(Miles going to the wrong school, Rio being a science teacher, Jefferson loving vigilantes/supers, using MJ as an origin for Miles, the skin lightening of both Miles and Rio). It was insulting because they clearly researched and had a fidelity to Peter Parker as they had references from both of the 616 and Ultimate Universes but with Miles, they somehow missed the first thing about Miles: he doesn’t want to be Spider-Man. I didn’t like this version. Notice the past tense.

Miles Morales PS5 redeemed him. I am half-way as I’ve done all of the side quests and pretty much half of the main story. And I also seen the whole main story on YouTube. So yeah.

First off, the first thing I noticed about Miles was his fresh-cut. It was, to quote my brother, “a hot mess” in the first game. I was delighted to hear that the first thing the “black” consultant told the Insomniac developers. His edge was fucked up. Second thing was how social Miles was. Third thing is that they retconned Miles going to Midtown. Yes, in the first thing they did actually have kid in Brooklyn attend a public school in Queens. I am pretty sure in the remaster the changed it to Brooklyn Visions.

These changes along with the fidelity of the relationship between Miles and Ganke were what sold me on this version of the character. I get it. No one wants Peter to die and honestly, they probably should have just used Anya, but Miles is popular now and it’d be stupid to just not capitalize.

So let’s talk about a few characters starting with the actual main character of the game: The Tinkerer.

Let me tell you that at first I thought she was redundant. I am not going to spoil it, but it was obvious the moment she is introduced in the game and Miles mentioned her twice before she is formally introduced. It’s clear that she was the focus. I felt that she was redundant because there is a literal harem of morally dubious women who Miles has a close connection to that she takes aspects from. Tinkerer is an amalgamation of all of them. She is a girl leading a gang(Diamondback/Tomoe) who is a genius inventor(Ceres). She wants revenge against a company that is poisoning the city and killed her brother so she becomes a ruthless vigilante(Tiana). Her powers or devices are that she manipulates a metal to form any shape she wants(Tomoe). Her relationship of Miles is one that is really platonic with some romantic undertones(literally every single person that I mentioned) but it is torn apart because Miles lies and keeps secrets from her(Katie Bishop).

What sold me on her character is the work they did in her collectibles which I implore you to collect because they provide so much depth to her character and also, it doesn’t really bother to explain Miles’ character in this world but hers. This girl is hurt because her loved one was killed and she saw Miles as family or a second brother. They hung out together and as soon as Miles went to Visions, they drifted apart. I’ve always wondered about the kids Miles left in his whole transfer situation and Tinkerer was one of them. Her pathos and identity is very much tied to Miles. And I love her.

Look, at first, I was reluctant to want her in the main comic, but someone put in too much work to not include her in Miles’ main rogues gallery. I hope that Saladin sees it and implements a version of her in the MM: Spider-Man comic. She also reminds me of Gear from Static Shock except she is not a gay white man.

Ganke was spot on. This is the best adaptation of Ganke I’ve seen.

Yes even better than Homecoming.

Ganke is part of Miles’ Spider-Man. He is not just the fat Asian kid providing tech support. He is the motivation and is apart of it too unlike the thing they tried to do with MJ and Peter in the first game. This also shows the clear contrast of Peter and Miles. Peter never trusted anyone enough to be that involved in his being of Spider-Man. Miles knows that he can’t do it alone and relies on Ganke for information gathering and webs. Ganke is important and this game nailed it.

Aaron Davis is in this game and no one is surprised. This version of Aaron...is different. Okay in the comics, he is a foil to Miles in that while Miles is becoming more heroic, Aaron is becoming more villainous. It’s no coincidence that Spider-Man and the Prowler look similar but the gist is that if Miles didn’t get bit by the spider, Miles would have become Prowler 2.0. The game eschews this dynamic because it is hard to pull that off after the mangled Miles’ origin so they opted for the Prowler to foil Miles in a different way: keeping secrets from family and friends and being protective of family because fear of loss. Aaron, after losing his brother and never getting a chance to reconcile with him, is hurt and wants to protect Miles and subsequently Rio. Miles, throughout the game, is becoming increasingly worried about his mom running for city council and painting a target on his back. He shows his frustration and distances himself from his mother in his work as Spider-Man. Aaron does the same to Miles when he finds out that he Spider-Man. There comes a point where the two collide and Aaron goes further into the extreme which I won’t spoil. You get it.

This change, while different, isn’t terrible. It’s actually really well thought out. It accomplishes the same thing in that Aaron is not a good role model but he is a good person to Miles. It allows Miles to reflect on his own behavior towards his mother. So I’m with it.

Oh and before I forget, Danika being in this game sold me that they actually started actually researching Miles. They ignored the weird racial commentary that she became enamores and she became a foil to JJJ. A voice of youthful and helpful positivity vs Randian cynicism and skepticism. A social justice activist vs an arrogant self important commentator. And it was fun listening to her. Hopefully Saladin brings her back. I am currently on Underground base liberation missions where she teams up with Ganke and Miles in putting them down. Just started, but there was already some mild hint that Ganke is crushing on her(they are a couple in the comics). So yeah.

The cons because like Ganke, I love pros and cons list. Two things about this game annoys me. First, the move to Harlem and this forced narrative of Miles being Harlem’s Spider-Man made no sense because just look at the map. Harlem is part of Manhattan. There is nothing stopping Peter from visiting Harlem regularly. Brooklyn, however, would justify having their own Spider-Man. As, if you didn’t know, Brooklyn is emerging into becoming the next big city as the area is thriving. Also, gentrification. Point is there is a reason why Miles connection to Brooklyn is important. It is foil to Peter who is from Queens and wanted to move into Manhattan island because part of it was he saw it as a measure of success to get out of the old neighborhood and make it big. Miles loves Brooklyn and doesn’t want to move out. Trying to replicate his love for his city in Harlem just because it’s predominantly black and brown is lazy and honestly if they included Brooklyn in the game, it would have justified the price of this game. Which brings me to the second point.

This game is too short on content to be costing $50 dollars. Just to point out something, all of the DLC from the first game cost 10 bucks a pop and you had as much content in those three expansions as you do this game. Infamous First Light was the same exact thing in relation to Infamous Second Sons and it cost 30 bucks. Uncharted Lost Legacy cost 30 dollars. I could go on. Point is that it shouldn’t have costed nearly the price of a full game when in comparison to the previous iteration, it wasn’t. Now I’ve seen people say that hating because it’s short isn’t warranted or pull up this quoted fact that video games are too long. Anti-consumerist bullshit aside, the difference between the main storyline of the previous game and this one is not repetition. It’s the lack of variety in enemies and deesculating storylines. In the first game, there were a variety of enemies that had their own AI and attacks. And you adjusted accordingly to whom you were facing. There were classes of enemies within the variety. You had the rudimentary common criminal which had 4 classes and how to deal with them and from that point, each enemy afterwards were variations of those four classes and each provided a different challenge. The repetition wasn’t boring because it provided a new challenge. This game only gives you three types of enemies and while 2 are vastly different from anything in the previous game or it’s expansions, the need to limit the series to focus on narrative becomes unwarranted because you are still getting less for nearly the same price.

That’s all. Have a great day. It was a fun game. Really.

@ubernegro

35 notes

·

View notes

Photo

LEK BORJA RENEWS FILIPINO HISTORY THROUGH ART

BY PRECIOUS RINGOR

Asian Pasifika Arts Collective New Outlooks Blog

April 2, 2021

http://ow.ly/fEby50FlQWZ

Editor’s Note: Precious Ringor brings us a second artist profile, this time of Filipino American interdisciplinary artist and poet Lek Borja, whose work is an attempt to track the continuous colonization across time, first within the Philippines from Spain and the United States, through present day America and trying to give voice to Filipino life against a white hegemony. Precious displays how Lek crosses borders of cultural stereotypes, seeking to expand the visions placed on Filipinos by other oppressive powers, and inserting her culture in art spaces where they are new and unfamiliar, but for the community, reminders of home.

Header Image: “Heritage at the Threshold” by Timothy Singratsomboune | Digital photography collage, 5400 x 4050 px, 2021.

Getting to know someone virtually is one of the sad realities we’ve had to face because of COVID-19 regulations. It’s both a blessing and a curse—we’ve become a global village, but at the same time we’ve all had more eye and back problems from sitting around and zooming this past year.

A zoom call and an hour was all I had to get to know Lek Vercauteren Borja, a Filipino American interdisciplinary artist and poet widely known for her thought-provoking work into the Asian diaspora. Chatting with Lek didn’t feel like a job though; time flies fast when you’re having fun.

One of the things I noted was Lek’s warm and friendly nature. Most of the time, it’s uncommon for an interviewee to ask questions about the interviewer. Lek unabashedly admitted that she did a bit of ‘stalking’ before we hopped on Zoom, “I like to know about the person I’m talking with, even before the interview starts.”

Lek started in poetry. Armed with a love for Shakespeare, she pursued a dual concentration in Art and Creative Writing at Antioch University. It was there that she first fell in love with art history and sculpture. During that time, her first chapbook, Android, was published by Plan B Press. She took this as a sign to continue pursuing a career in arts.

As an artist, she admits that’s where she gets inspiration from, “I want to talk about the history of Filipinos, the invisible stories. Growing up in the Philippines and studying there, I realized there was a lot missing in our history books. It seemed as if it were written from a western perspective.” She reminded me so much of the Philippines, of home. Because of our similar upbringing, I immediately understood her search for truth.

The themes of home and longing, of memory and the present, and of giving Filipino lives new voices, carry across her work, and no more palpably than her piece Evolution of the Aswang Myth, what she calls “seed and the origin” to all her current works. Lek says “Without it, I wouldn’t be thinking about art, the way I’m making now.” This 8 x 8 feet painting explores the origins of the aswang or manananggal, a Filipino mythical creature typically depicted as a woman feared for its penchant for eating infants and unborn fetuses during the night. Interestingly, the aswang was also a word ascribed to the Filipina women who went against the forced religious conversion by Spanish friars during their colonization of the Philippines.

March 2021 marked 500 years since Spanish ships first arrived on the shores of the Philippines.

Since then, our country fought hard for liberation, first from Spain and then from the United States of America. In retrospect, it hasn’t been long since the Philippines became an independent nation. Today, we are striving to find our voice amidst the imperialistic erasure we’ve endured.

As Lek puts it, “What propelled me to tell these stories is the feeling that I had no voice. For one, I didn’t speak English well so I couldn’t really talk about what I was going through or how I felt. That’s why a lot of my work now focuses on bringing my experiences of living in the Philippines at the forefront and seeing how that’s connected to bigger conversations and narratives around us.”

Currently, Lek’s work called Anak (My Child) is being featured in the gallery at Towson University’s Asian Arts & Culture Center.

View Anak (My Child) Exhibit: https://towson.edu/anak

Besides online exhibitions and virtual galleries, Lek is also conducting several workshops in Baltimore’s upcoming Asia North Festival. These workshops are a good model for Lek’s philosophy in making art out of personal histories. Whether it’s experiences of displacement or change, she points out that everyone’s story matters and there will always be a community of people who can empathize with that.

“I think it’s really important for our stories to be brought to light in the larger narrative. They think by calling us model minority, our problems can easily be brushed aside” I lamented the steady rise of xenophobic crimes these past few months.

“I agree, it’s a really complex issue” Lek adds, “Why are we so silent? Why do we stand in the shadows? I’ll probably look for an answer my entire life. It’s hard to talk about our struggles and it’s not easy to have conversations about the past. There’s a culture of silence that’s been normalized and it’s perpetuated even in our own homes. But that’s part of the work I do, bringing everything from the past into the forefront so we can have deeper conversations about it.”

Speaking of the past, Lek’s introduction to the arts started in Tarlac, a city located north of the Philippines. Besides being known as the most multicultural province, the city is home to numerous sugar and rice plantations. “The population of our barrio was probably less than 1,000. Our family had a farm as well as a sugar-cane and rice field plantation. My inang [grandmother] also worked in the market as a butcher. It was a pretty simple country lifestyle but my childhood was amazing.”

Life in the country has been instrumental to Lek’s artistry. “The memory of the landscape and of the community is an extension of my art,” Lek explains. As a young girl, her biggest inspiration comes from her grandfather who, like herself, was also an artist. Lek would copy his drawings and eventually create drawings of her own. Recently, Lek has started to incorporate banana leaves into her work. Banana leaves are incredibly important to Filipino culture as it is used for cooking and traditional homebuilding.

“Sounds like you had to find your own path, coming here at such a young age and experiencing culture shock. America is very different from the Philippines!” I quipped.

“It was snowing where I first came here!” she exclaimed, thinking back to her initial introduction of America. “It was November when we landed in New York, it was freezing. I remember our families bundling us in huge warm winter coats before wecould even say hello. It was definitely a huge shock.”

I laugh, thinking back to when I first arrived in California ten years ago. Silly to think I was already freezing in sunny temperatures when she had to endure piles of snow. “Do you think you’ve had to change yourself in order to adjust to that culture shock?”

“For a long time I really didn’t know who I was,” Lek admits. “When I was younger, the school I went to was predominantly white. What I thought about how I should present myself came from that image. I dyed my hair blond and put on blue colored contacts to fit in. It was a lot of assimilation and cultural erasure. I started talking less Tagalog and less Ilocano. But art has really helped me find myself. It made me think more deeply about who I really was and what was important to me on an authentic level.”

Halfway through our conversation, we slowly realized just how similar we were. From migrating at the age of ten to living twenty miles apart in the same city. It was also in chatting that Lek found out I spoke Tagalog fluently, one thing she regrets losing unexpectedly. As it is my first language, Lek asked me to speak it instead. Once again, her warm nature bled through the Zoom interview; I found it refreshing since hardly anyone thinks about the interviewer’s comfort.

Unsurprisingly, community building is important to Lek. Before working, she likes to ask herself the following questions, ‘How is what I’m doing connected to my family and everyone in the Filipino community? How can I better serve my community?’ One of the main reasons she moved to L.A. is to network with other Filipino artists.

“A few years ago, I showed my art alongside a group of all Filipino artists at Avenue 50 Studio gallery for an exhibition that Nica Aquino and Anna Calubayan organized (also both Filipinas). It’s crazy because I’ve lived in and out [of L.A.] for over 10 years now and it was only in 2019 that I started to be part of that community. It’s probably the most fun I've had at an art show, I really felt at home.”

“I’d love to visit the studio’s galleries once it’s safer to go outside”

“Definitely! I’ll keep you updated on any gatherings” Lek pitched excitedly.

“And I'll bring you guys homemade ube cakes and puto pao!” I teasingly replied back.

As our call came to a close I couldn’t help but ask Lek if she had any advice to give to budding AAPI artists.

“I’ll echo what people who have supported me have said in the past: trust yourself and trust that you can make a difference. It’s hard to figure out who you want to be when [the world] has expectations and demands from you. We’re lucky to live in a time where there’s so many possibilities. Figure out what you want to do authentically and genuinely, and go for it.”

Lek continues on, “Personally, it took me a long time to find my voice. When I was in grad school, I had a lot of doubt in myself because most visiting artists and curators couldn’t understand my work. What made it all worth it were the moments that people got [my voice] right away.”

Getting to know Lek and learning about her commitment to showcasing invisible stories has been awe-inspiring; it made me proud to be a Filipino American artist. And in the wake of our hurting AAPI community, I believe it’s incredibly important, now more than ever, to highlight and support works of people like Lek. People who have had to fight for their voice in this world, who our youth could look up to and be inspired to become.

About the Author:

Precious Ringor is a Filipino-American singer/actress/writer residing in Los Angeles, CA. Ringor graduated from Cal State University, Fullerton with a degree in Human Communication Studies where her research is geared towards Asian American socio-cultural communication norms. Besides performing in various theatre shows and indie film sets, Ringor also works as a content contributor to Film Fest Magazine and Outspoken

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

On my mind...

So, as we are all aware, Captain Marvel comes out next week. I've had my tickets for over a month, and am genuinely very excited to see it, regardless of the fact that the duel-marketing for both that and Endgame kind of lowers the hype of it. Following Infinity War, when Marvel fans were once again reminded of its presence, I instantly knew there would be more hate than usual for this one, and it was for one of the reasons I personally happen to be excited about it, and it's the fact that it's the first major female lead in a Marvel movie. We obviously don't live in a perfect world, and I get that there are sexist people out there. That's no surprise.

But what IS surprising is the fact that not only has the hate grown and spread in these coming months, but it's just gotten nastier.

These aren't just one-off sexist people anymore. These are Marvel fans, both casual and die-hard who are literally boycotting this movie because of its lead.

Now listen. I have no problem with valid criticism. I agree with the fact that Marvel has been promoting the sh*t out of this movie, and yeah, to a point where it's kind of getting annoying. But like a normal human being, if I see a promotional video for the third time today, I just ignore it and keep scrolling.

But then there are the arguments that are just absolutely ridiculous, and I'm gonna call them out. These are actual quotes under Captain Marvel posts on Instagram:

"SJW feminist movie with no good plot"

Wow, first of all, I'm jealous of the fact that this guy got an early viewing of the movie, considering he knows the entire plot.

But in all seriousness, you're telling me that because Marvel made their TWENTY-FIRST movie in the MCU with a female lead for the first time, it makes it a SJW political move?

Like, how did we reach a point where casting a female lead, specifically in an action movie, results in backlash because it's somehow "pressing an agenda"? "Oh no, a woman plays a major role in this movie and isn't overshadowed??!!!11" God forbid it doesn't star a male superhero. God forbid she isn't sexualized, and she's treated like a normal person.

In an alternate universe, where everything the same except Captain Marvel is a guy, no one is batting an eye.

"This movie will ruin the MCU"

Yeah, cause the MCU has a history of just BOMBING their movies, amirite?

Like, get real. Even regardless of my last point, in the highly unlikely chance the movie turns out the be that bad just on its own, do you really think that with Endgame right around the corner, everyone's suddenly going to turn around and not want to see it?

Look, I get it. If you think a couple lines from the trailer are "cringey" or whatever, you don't have to like it. But to make the claim that this movie is going to "ruin the MCU" is a bit of an overstatement.

And tbh...if this movie results in sexist Marvel fanboys leaving the franchise...all the power to them.

"I'm a white dude, so Brie Larson probably doesn't want me seeing this"

There are tons of comments like these, all along the lines of "I hate Brie Larson", and "Brie Larson is sexist and racist cause she hates white men". This all originates from comments she made regarding the diversity of movie critics, which I'll link here. To summarize it, she had told the interviewer that she wanted to strive for more diverse inclusivity in the press, as it was confirmed it a study that about 61% of critics were, in fact, white and male. She referenced the movie A Wrinkle in Time saying, “I don’t need a 40-year-old white dude to tell me what didn’t work about A Wrinkle in Time. It wasn’t made for him! I want to know what it meant to women of colour, biracial women, to teen women of colour, to teens that are biracial.”, due to the movies prominent diversity.

Following this, box office projections for Captain Marvel declined 28%.

I'm not sure how, but it seems that the word "diversity" has become taboo. Because the same men who were bitching about a female lead are now bitching about these "attacks on men". Suddenly the same guys who are "tired of this snowflake SJW BS" are throwing a fit over the need to be the majority. They are making these claims while missing the point that it's not about people not wanting white guys; it's about people wanting minorities, too. It's about POC wanting to feel represented in industries that, for centuries, have been dominated by the white men. It's not saying, "Well, there should be less white men!". It's saying there should be equal opportunity for everyone.

To get real personal for a sec, I have my own story of feeling unrepresented. For over 8 years, I went to my public school that was predominantly Asian and Middle Eastern. There was nothing wrong with that - I had great friends there, as well as wonderful teachers. But being the only Jewish girl there sometimes got to me. I was the only one in my grade that didn't celebrate Christmas, and I had to explain to my teachers time and time again why I would be away on certain holiday's. (Side tangent: On one particular Jewish holiday, we - my sister and I - didn't get our parents to call in to report our absence. They ended up calling THE POLICE because they couldn't reach our parents, as their phones were turned off in synagogue, and couldn't think of one good reason as to why we would be away. This was after years of attending that school, being absent on the same days each year, and having identifiable Jewish surnames. That was peak level of ignorance). Again - it wasn't that I wanted there to be less Asian or Middle Eastern kids. It was just the fact that I wished there was someone else like me. So you can imagine the culture shock when I went to high school for the first time, where the school was thrice the size, and everyone came from a different background. It was crazy to me, but in a good way.

To make a long story short, this is the point that people seem to miss. Brie Larson never said she hates white dudes. She never said she doesn't think they should support the movie, or become a critic. She just is promoting the idea of minorities getting those chances, too.

Anyways, that's my rant and two-cents on this whole thing. I personally can't wait for Captain Marvel.

#Captain Marvel#marvel#MCU#Brie Larson#Carol Danvers#Avengers#Opinion Piece#Rant#On my mind#Diversity#movies#Infinity war#Endgame#Coming soon

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dealing with discrimination? Mental health suffering? Let’s make the time to talk.

When I recently read the news about tennis star Naomi Osaka’s struggle with mental health problems, particularly her depression, I felt immediately empathetic.

I bet we can all empathize a little now, especially during this ongoing pandemic. However, there is an additional dimension related to being visibly not Japanese in Japan – or a colored person in a predominantly white society in the West – that can make the struggle a little more intense.

I’m sure the situation is similar for other people who are discriminated against, be they women, people who identify as LBGTQIA, people with a disability, or people in more than one of these categories.

To get a different perspective, I decided to turn to Mark Bookman, a colleague of mine. From Tokyo University, he is a historian of disability policy and related social movements in Japan and works as an accessibility advisor and works with government agencies and companies around the world on projects related to disability inclusion. Mark has a rare degenerative neuromuscular disease similar to ALS (also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease) that affects only six people in the world. Therefore, he uses a motorized power wheelchair for most of his daily activities.

Two weeks ago, Tokyo governor Yuriko Koike was hospitalized due to fatigue. Mark and I thought this would be a good time to do a quick mental health check by talking about our experience as non-Japanese residents investing in this country. We’re also pretty sure many readers can relate to it.

Baye McNeil: My experience is that discrimination is natural to a conspicuously strange looking person living in Japan. While it’s true that cops don’t routinely open fire on black people here, we are exposed to an abundance of annoying micro-aggressions that look like paper cutouts. These are emotional and psychological assaults that, if pointed out, can sometimes trigger reactions from both Japanese and non-Japanese telling you to “man up” or “make hard”. This can cause you to remain silent about these things for fear of appearing oversensitive and being accused of playing the victim card. I say “accused” because when “victim” is used that way it kind of comes off as an insult. How is your experience of discrimination in Japan, Mark?

Face to Face: When it comes to dealing with people with a disability, sometimes a person will interact with a caretaker rather than the disabled person themselves. This can lead to misunderstandings. | GETTY IMAGES

Mark Buchmann: My experience of discrimination in Japan as a disabled person is in some ways similar to yours. Nobody has used ableist insults against me, explicitly or deliberately, but I often run into barriers in the built environment that make life much harder. For example, public toilets are not set up for my large overseas wheelchair, making it difficult for me to be too far from my home. Lack of availability has kept me from many places and from telling others about my needs, so people often make wrong assumptions about what they can do to help me when I need support.

I particularly remember one incident where I called ahead to ask if a restaurant was accessible. The owner said the place has accommodated wheelchair users in the past so I went for it. When I got there, I saw that there was a step in front of the entrance that my chair couldn’t climb. The owner insisted he could lift my wheelchair over the step, even though it weighs 300 kilograms.

I knew if I turned down his offer it would spark a scene and get others in the area to interfere. Since I didn’t want to bother explaining to so many viewers why they couldn’t help the owner, I decided to say, “I’m not sure this is a good idea.” Before finishing my testimony, I tugged however, the owner is already at my chair. I’m sure he meant well and tried to help. Even so, he injured my arm, and the psychological damage was worse: I had no easy way to prevent such incidents because I couldn’t correct misunderstandings like the owners’ at the moment.

Baye: What should he have done?

Mark: He could have just asked me directly about my needs. It is possible to do this in a courteous manner that helps understand the situation. I know this goes against the Japanese concept of omotenashi where the host has to anticipate a customer’s needs, but if just had a chat with me I could have explained why pulling on my chair would endanger both of us, and we could have worked together to find an alternative solution to the problem of accessibility.

In addition, a person often interacts with an attending caregiver instead of the person with the disability. This not only dehumanizes the disabled person, but also leads to misunderstandings, as the caregivers only know so much about the people they care for.

Baye: I recently interviewed Kinota Braithwaite, a black Canadian who learned that his 9 year old biracial “Blackanese” daughter – a future Naomi Osaka – was bullied in her elementary school here in Japan. No physical attacks, just persistent efforts to stigmatize them and stigmatize their skin color, which bothered them and harmed their mental well-being.

So he wrote a children’s book called “Mio The Beautiful,” which was written in Japanese and English about his daughter’s experience of discrimination and was intended to be used as a teaching tool. Not everyone can write a book, but I mention it because this was a loving father who did something positive to help his daughter and the welfare of the wider community.

I myself have regular seizures of self-imposed seclusion to keep myself mental. During this “sabetsu (discrimination) sabbatical” I only venture to go public if it is absolutely necessary.

There are very few foreigner-friendly rooms that are “safe” from the psychological onslaught of foreigners. A man who refuses to get on an elevator with me, a woman who clutches her wallet tighter than she notices me, or a salesman who tells me they can’t speak English because I speak perfectly understandable Japanese speak to them – that can be annoying, it can trigger me. So, I prescribed these relaxing sabbaticals to myself to take a break. And more recently, those breaks have included my Japanese wife and our two adopted kittens. It’s amazing what a little time with some kittens can do for the soul.

Mark: I listen to you for this idea of friendly, safe places. We need them to talk to others about the physical and social barriers we face that cause significant difficulties.

Social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter can offer some relief and solidarity, but there are many people who are unable to use these channels due to stigma, shame, or a lack of resources. We need to remember this fact and do our best to create multiple and different places where we can hear from data subjects about their experiences of discrimination. Then we can learn more about the needs of these people and start building a more inclusive society.

Personally, I’ve found solace in private online settings that I’ve made with friends. We play games, watch videos, listen to music and discuss problems we face every day with the aim of finding solutions. We try not to judge and pool our resources to make everyone happy. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t. But with community members from all over the world, we know someone will always be there, no matter what time zone.

Baye: I talked about this with my friend Selena Hoy from TELL. TELL is a certified mental health nonprofit that serves the international community in Japan and acts as a safe space for many people. She told me: “If you are overwhelmed, you are not alone. And you don’t have to fight alone. Talk to someone – a friend, family member, colleague … or if you prefer to keep it private, you can always call the lifeline, which is anonymous and non-judgmental. “

If you or someone you know is in crisis and needs help, resources are available. In an emergency in Japan, please call 119 for immediate assistance. The TELL Lifeline is available to anyone who needs free and anonymous advice at 03-5774-0992. For those in other countries, visit the International Suicide Hotlines for a detailed list of resources and assistance.

In a time of misinformation and too much information, Quality journalism is more important than ever.

By subscribing you can help us get the story right.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

PHOTO GALLERY (CLICK TO ENLARGE)

source https://livehealthynews.com/dealing-with-discrimination-mental-health-suffering-lets-make-the-time-to-talk/

0 notes

Link

Republican U.S. Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith, center, faces Democrat Mike Espy in the Nov. 3 election for U.S. Senate. by Adam Ganucheau Mississippi Today An essay by Cagney Weaver | Nov. 1, 2020 I’m a white woman who voted for Cindy Hyde-Smith in 2018. I will be voting for Mike Espy this November. For me, it comes down to one thing: race. Cindy Hyde-Smith has routinely shown in the two years since she was appointed to the Senate that she simply does not care about all Mississippians. I am not sharing my story to be some sort of moral crusader or to show that I have become “woke.” I am doing this because this version of Mississippi has existed for far too long. Someone has to speak up. It is our moral obligation as Mississippians, as women, as mothers to change what Mississippi has been and fight for a better future for all of our state’s children. I haven’t always felt this way. I grew up on the Mississippi Gulf Coast in a very white world. The schools I attended were predominantly white, and I had few opportunities to interact with people of color. It’s difficult to explain the strong grip that upbringing in that kind of environment can have on you. I began seeing things a little differently when I went to college at the University of Southern Mississippi. I became friends with people of color. I was shocked to learn that sororities were segregated by race. I took a class from my first ever teacher of color, Dr. Shirley Bowles. But what really changed me was becoming a public school teacher. I began teaching in 2010 at the same elementary school where I attended kindergarten myself. In a small-town Mississippi turn of events, I took over for my kindergarten teacher in the very same kindergarten classroom where I had once been a student. In my first few years of teaching, it was impossible not to notice how few students of color I taught. That had a profound effect on me. In 2014, I was awarded the Milken Educator Award, a national award that allowed me the pleasure of working closely with game-changing women of color in education from across our state and country. That same year, I was asked to speak at the Mississippi Teacher and Administrator of the Year Conference. As I looked around that room, I saw so many people of color in these vital roles that shape young minds. It was hard not to wonder why I had seen so little of that in my life. That was a defining moment for how I felt about race in Mississippi. I long for my students to see people who look like them in administrative roles in my workplace. Just in the history of public education, it’s not hard to see how people of color have been systemically held back by racist policies: redlining, immoral treatment of Black mothers using government subsidies in the 1950s and 1960s, the disproportionate number of children of color whose best hope at gaining a quality education was a lottery system. Today, that public education system of racism looks a little different but still exists, most obviously through how our schools are funded. How can it be that my elementary school in Biloxi is less comfortable for students than a similarly sized school across the bay in Ocean Springs? How can it be that teachers in schools in southwest Mississippi and the Delta are asked to meet the same academic benchmarks with dramatically fewer resources than my colleagues here in Biloxi? It’s clear from listening to her that Cindy Hyde-Smith doesn’t understand that history or that present. And she sure doesn’t understand the effects that her actions and words have on so many Mississippians. In 2018, I voted for Hyde-Smith because I honestly didn’t know better. As a registered Republican, the last few years have shown me that the makeup of the party I once believed in is disgraceful, immoral and incompetent to hold public office. I am ashamed of my previous vote of elected officials, but I will never make that same mistake again. My vote matters, and so does yours. I became an educator because I care about children. The longer I teach, the deeper that care becomes. I will fight with every breath that I have to ensure all my students – particularly my students of color – have a successful future. I know I cannot save them from all the problems they’ll face, but I need to have faith that our elected officials will make the right choices for their future. That is part of me, it’s part of my morals, and it’s something that I fight for every single day. I need to be able to say the same of my U.S. senator. Cindy Hyde-Smith has done nothing for our state, and worse, she has done nothing for our children. Our children are the future. If you’re not fighting for the children of Mississippi, then you’re not fighting for Mississippi. And I believe that future looks better in the hands of Mike Espy. Editor’s Note: We are sharing our platform with Mississippians to write essays about race. This essay is the fourth in the series. Read the first essay by Kiese Laymon, the second by W. Ralph Eubanks, and the third by Taylor BreAnn Turnage. Click here to read our extended editor’s note about this decision. About the Author: Cagney Weaver is a native of the Mississippi Gulf Coast. She has been in education for 11 years, during which she has attained her National Board Certification in 2014 and won the Milken Educator Award in 2014. Serving as a Lowell Milken Unsung Heroes Fellow, she has dedicated her life to education in the state. She has worked in several capacities as a speaker, presenter, and facilitator at educational conferences in the state. This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license." data-src="https://mississippitoday.org/?republication-pixel=true&post=841499&ga=UA-75003810-1" />

0 notes

Text

Black History Fact of the Day

Famed civil rights leader Stokely Carmichael was born on June 29, 1941, in Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago. Carmichael's parents immigrated to New York when he was a toddler, leaving him in the care of his grandmother until the age of 11, when he followed his parents to the United States. His mother, Mabel, was a stewardess for a steamship line, and his father, Adolphus, worked as a carpenter by day and a taxi driver by night. An industrious and optimistic immigrant, Adolphus Carmichael chased a version of the American Dream that his son would later criticize as an instrument of racist economic oppression. As Stokely Carmichael later said, "My old man believed in this work-and-overcome stuff. He was religious, never lied, never cheated or stole. He did carpentry all day and drove taxis all night& The next thing that came to that poor black man was death—from working too hard. And he was only in his 40s."

In 1954, at the age of 13, Stokely Carmichael became a naturalized American citizen and his family moved to a predominantly Italian and Jewish neighborhood in the Bronx called Morris Park. Soon Carmichael became the only black member of a street gang called the Morris Park Dukes. In 1956, he passed the admissions test to get into the prestigious Bronx High School of Science, where he was introduced to an entirely different social set—the children of New York City's rich white liberal elite. Carmichael was popular among his new classmates; he attended parties frequently and dated white girls. However, even at that age, he was highly conscious of the racial differences that divided him from his classmates. Carmichael later recalled his high school friendships in harsh terms: "Now that I realize how phony they all were, how I hate myself for it. Being liberal was an intellectual game with these cats. They were still white, and I was black.''

Though he had been aware of the American Civil Rights Movement for years, it was not until one night toward the end of high school, when he saw footage of a sit-in on television, that Carmichael felt compelled to join the struggle. "When I first heard about the Negroes sitting in at lunch counters down South," he later recalled, "I thought they were just a bunch of publicity hounds. But one night when I saw those young kids on TV, getting back up on the lunch counter stools after being knocked off them, sugar in their eyes, ketchup in their hair—well, something happened to me. Suddenly I was burning.'' He joined the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), picketed a Woolworth's store in New York and traveled to sit-ins in Virginia and South Carolina.

A stellar student, Carmichael received scholarship offers to a variety of prestigious predominantly white universities after graduating high school in 1960. He chose instead to attend the historically black Howard University in Washington, D.C. There he majored in philosophy, studying the works of Camus, Sartre and Santayana and considering ways to apply their theoretical frameworks to the issues facing the civil rights movement. At the same time, Carmichael continued to increase his participation in the movement itself. While still a freshman in 1961, he went on his first Freedom Ride—an integrated bus tour through the South to challenge the segregation of interstate travel. During that trip, he was arrested in Jackson, Mississippi for entering the "whites only" bus stop waiting room and jailed for 49 days. Undeterred, Carmichael remained actively involved in the civil rights movement throughout his college years, participating in another Freedom Ride in Maryland, a demonstration in Georgia and a hospital workers' strike in New York. He graduated from Howard University with honors in 1964.

Carmichael left school at a critical moment in the history of the Civil Rights Movement. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee dubbed the summer of 1964 "Freedom Summer," rolling out an aggressive campaign to register black voters in the Deep South. Carmichael joined the SNCC as a newly minted college graduate, using his eloquence and natural leadership skills to quickly be appointed field organizer for Lowndes County, Alabama. When Carmichael arrived in Lowndes County in 1965, African Americans made up the majority of the population but remained entirely unrepresented in government. In one year, Carmichael managed to raise the number of registered black voters from 70 to 2,600—300 more than the number of registered white voters in the county.

Unsatisfied with the response of either of the major political parties to his registration efforts, Carmichael founded his own party, the Lowndes County Freedom Organization. To satisfy a requirement that all political parties have an official logo, he chose a black panther, which later provided the inspiration for the Black Panthers (a different black activist organization founded in Oakland, California).

At this stage in his life, Carmichael adhered to the philosophy of nonviolent resistance espoused by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. In addition to moral opposition to violence, proponents of nonviolent resistance believed that the strategy would win public support for civil rights by drawing a sharp contrast—captured on nightly television—between the peacefulness of the protestors and the brutality of the police and hecklers opposing them. However, as time went on, Carmichael—like many young activists—became frustrated with the slow pace of progress and with having to endure repeated acts of violence and humiliation at the hands of white police officers without recourse.

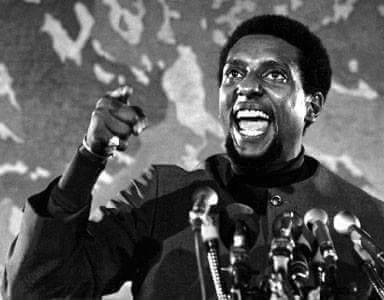

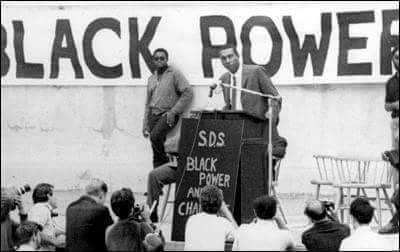

By the time he was elected national chairman of SNCC in May 1966, Carmichael had largely lost faith in the theory of nonviolent resistance that he—and SNCC—had once held dear. As chairman, he turned SNCC in a sharply radical direction, making it clear that white members, once actively recruited, were no longer welcome. The defining moment of Carmichael's tenure as chairman—and perhaps of his life—came only weeks after he took over leadership of the organization. In June 1966, James Meredith, a civil rights activist who had been the first black student to attend the University of Mississippi, embarked on a solitary "Walk Against Fear" from Memphis, Tennessee to Jackson, Mississippi. About 20 miles into Mississippi, Meredith was shot and wounded too severely to continue. Carmichael decided that SNCC volunteers should carry on the march in his place, and upon reaching Greenwood, Mississippi, on June 16, an enraged Carmichael gave the address for which he would forever be best remembered. "We been saying 'freedom' for six years," he said. "What we are going to start saying now is 'Black Power.'"

The phrase "Black Power" quickly caught on as the rallying cry of a younger, more radical generation of civil rights activists. The term also resonated internationally, becoming a slogan of resistance to European imperialism in Africa. In his 1968 book, Black Power: The Politics of Liberation, Carmichael explained the meaning of black power: ''It is a call for black people in this country to unite, to recognize their heritage, to build a sense of community. It is a call for black people to define their own goals, to lead their own organizations.''

Black Power also represented Carmichael's break with King's doctrine of nonviolence and its end goal of racial integration. Instead, he associated the term with the doctrine of black separatism, articulated most prominently by Malcolm X. "When you talk of black power, you talk of building a movement that will smash everything Western civilization has created,'' Carmichael said in one speech. Unsurprisingly, the turn to black power proved controversial, evoking fear in many white Americans, even those previously sympathetic to the civil rights movement, and exacerbating fissures within the movement itself between older proponents of nonviolence and younger advocates of separatism. Martin Luther King called black power "an unfortunate choice of words."

In 1967, Carmichael took a transformative journey, traveling outside the United States to visit with revolutionary leaders in Cuba, North Vietnam, China and Guinea. Upon his return to the United States, he left SNCC and became prime minister of the more radical Black Panthers. He spent the next two years speaking around the country and writing essays on black nationalism, black separatism and, increasingly, pan-Africanism, which ultimately became Carmichael's life cause.

In 1969, Carmichael quit the Black Panthers and left the United States to take up permanent residence in Conakry, Guinea, where he dedicated his life to the cause of pan-African unity. "America does not belong to the blacks," he said, explaining his departure from the country. Carmichael changed his name to Kwame Ture to honor both the president of Ghana, Kwame Nkrumah, and the president of Guinea, Sékou Touré.

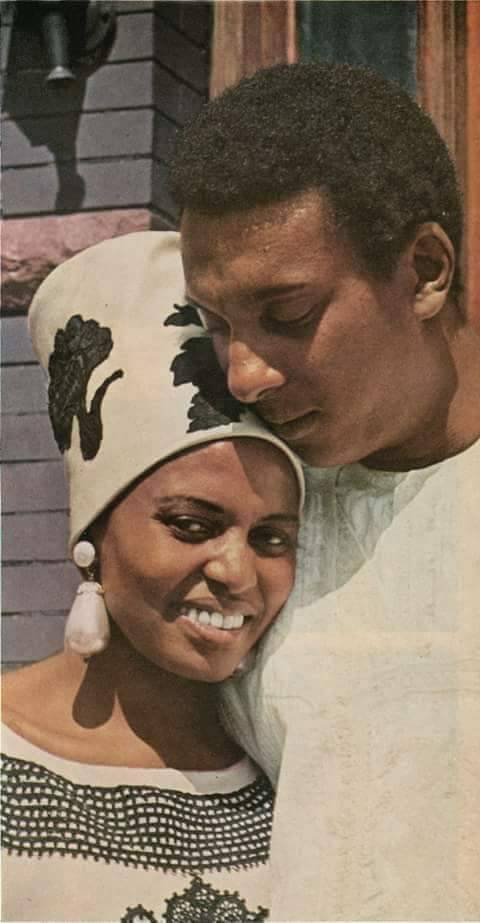

In 1968, Carmichael married Miriam Makeba, a South African singer. After they divorced, he later married a Guinean doctor named Marlyatou Barry. Although he made frequent trips back to the United States to advocate pan-Africanism as the only true path to liberation for black people worldwide, Carmichael maintained permanent residence in Guinea for the rest of his life.

Carmichael was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 1985, and although it is unclear precisely what he meant, he said publicly that his cancer "was given to me by forces of American imperialism and others who conspired with them.'' He died on November 15, 1998, at the age of 57.

An inspired orator, persuasive essayist, effective organizer and expansive thinker, Carmichael stands out as one of the preeminent figures of the American civil rights movement. His tireless spirit and radical outlook are perhaps best captured by the greeting with which he answered his telephone until his dying day: "Ready for the revolution!" #stokelycarmichael

0 notes

Photo

Consumer Guide / No.42 / independent film-maker Sharon Woodward with Mark Watkins.

MW: Sharon, why is promoting awareness of Ataxia-telangiectasia important?

SW: I am very lucky to be able to work in this film-making world that I love, Mark. I also feel I have some responsibility within that to explore areas and issues that are not given mainstream airtime.

With regards to this subject particularly, I wasn’t at the time aware of A-T (Ataxia-telangiectasia). I was commissioned by the CEO William Davis. He contacted me a couple of years ago with this idea about giving a voice to the individuals with the condition rather than it coming from a medical perspective.

I ended up making two short films both around 4 minutes each. With a third film being a longer 10 minute project.

The 10 minute film has been shown at the FERFILM International Film Festival (Open Air Cinema). It was broadcast in November 2016 on a number of Freeview Channels via the wonderful Community Channel. Also shown at the 23rd International Independent Film Festival, PUBLICYSTYKA, in Poland.

The social work course and the health and well-being course at Northampton University are also using the film as a resource for discussion and debate.

The condition and the manner in which it manifests is varied and only hit me at the beginning of the year. Rupert, one of the main characters interviewed in the film, speaks candidly and at length about having Ataxia-telangiectasia. Sadly he died aged 31 in January 2017. I didn't really know him : we met during filming.

Yet, when editing an interview over a long period of time you listen and watch what people say and how they say it. You start to feel like you know and understand them. I didn’t know him and I can’t possibly comprehend what it must be like to have this condition, but all these people opened my eyes and made me aware of it. I hope I never stop learning.

MW: How reflective are you as a creative person? How does this trait manifest itself when producing film projects?

SW: I think this is hard to answer. I do feel I have a responsibility as I indicated before. I do think about the world, the way we live, how we treat each other. Perhaps at times I overthink and would be wise to let go.

Growing up, I never felt in my wildest dreams I would ever be given the opportunity to make films. It was a pretty dreadful environment and I was damaged greatly by it and the experiences I had. My saving grace was going into care. I later met some wonderful people - kind, caring - and, I also received help and support. So when the film-making presented itself to me I ran at it. This was a fantastic thing to have happen and I want to at least try and make a difference by using these skills.

I am clear that I have a belief system and trust it attracts like-minded people and organizations.

If it is only about money, then quite frankly, unless you make the big time you are more likely to make a profit and earn more doing something else.

MW: What was your involvement at Tyne Tees TV?

SW: This was an incredibly long time ago now (1988/89). I had been training at the BBC in Wales (cutting rooms) outside Cardiff. This was before, and after, I graduated from Newport Film School.

It was just another Trainee/2nd Assistant Editing job. Most of us (graduates at the time) realized that we were no longer going to be offered places in the industry. Permanent jobs were giving way to short term contracts : we were all going to be freelance. I was offered a feature film (I knew the director as she was a mentor for me). The film ‘Women In Tropical Places’ was funded by the BFI (British Film Institute), Film 4 and Tyne Tees who were offering facilities and housing the production. I was taken on as a freelancer for the production. During this time I also assisted the 1st Assistant Editor in the cutting rooms with a Tyne Tees documentary.

This was not a glamorous job as you were at the bottom of the pile. I was running around after people, sharpening Chinagraph pencils, getting coffee and Twix. I did a lot of what they called rubber numbering which you had to do on film. So when you cut the clapperboard off you could keep the film in sync until it went to the Neg Cutters. So logging footage : labelling up film cans. It was a low-level position but it was fantastic for learning about putting a film together. I always say to students try and get some work experience with an editor because the learning covers everything.

MW: How did you get your first big break with Channel 4, Sharon?

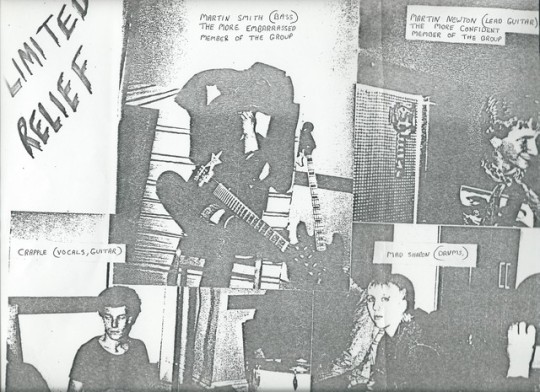

SW: This was by accident, Mark. I’d been a drummer in a punk band ‘Limited Relief’ and a youth performer in a drama group ‘Teenage Zits’. All this resulted in some of us from the drama group making a video called 'Not A Girl Anymore'. Maybe now this isn't so unusual, and perhaps seen as a natural progression for youth groups? However, back then, you had three TV Channels until Channel 4 came along. Video was not the accessible technology it is today. We raised funds via The Prince’s Trust.

Back then, in the early 1980s, we had no idea. I didn't even know about editing. Just thought that you set the camera up and everything just happened including the music and credits. Very naive by today's standards. If Google had been around it would have been a case of looking it up on-line.

The film had already been shot when commissioning editor Rod Stoneman decided to take it on for the youth series.

It was filmed in 1983 ; first broadcast in 1984/85 ; and again in 1986/87 as part of the Channel 4's youth series 'Turn It Up'. The production standards are not high and Channel 4 didn't have the same set up and criteria it does today. However, I was bitten by the film-making bug and from that point on I wanted to know more.

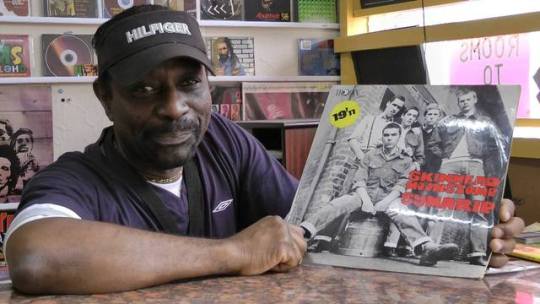

MW: How did you come to collaborate with ska band Symarip on your new film project?

SW: I first made contact with Monty Neysmith and Roy Ellis back in 2008 when I used a song 'Skinhead Girl’ by the Symarip in a documentary I was making called ‘Thank You Skinhead Girl’. It was about teenage identity and the song was just right as the theme.

I had the idea about the Symarip story then, but put it on hold at that time. Eventually, after a number of failed attempts at interviewing anybody from the band, I revisited the idea once more in 2012 (after a brief conversation with Roy Ellis prior to a gig he was doing in the UK). The filming began at Club Ska (100 Club) in London. We recorded Roy performing with The Moonstompers. This turned out to be an amazing night, much more than I had expected as Neville Staples showed up and we captured them on stage together.

I was very fortunate to interview four of the original Symarip band members, that’s Roy Ellis and Frank Pitter (face-to-face) and Monty Neysmith and Mike Thomas (via Skype).

I also have a number of other artists as well as fans and also interviewed the late Graeme (Goody) Goodall who sadly passed away in 2014, Co-founder of Island Records & Doctor Bird.

So a wonderful documentation of history - both social and economic - as well as a film for the fans.

MW: Tell me your overall plans for 'Ska'd by the Music'... including funding / promoting...

SW: Well it is near completion. I’ve been working on it for five years and I’m aiming to finish around July/August 2017. I had no financial backing. It was a difficult project to get funding for, and therefore I’ve been making it around my commissioned film work. This means what available time I’ve had has been spent on this production. All those involved: musicians, promoters, the narrator, researchers - everybody who helped me - they all put time in because they wanted to contribute. I’m extremely grateful to all of them for supporting this project.

The technical side has been another matter i.e filming, logging, uploading, editing etc. not to mention negotiating with music publishers. This is all time consuming and labour intensive and still ongoing (by myself). So has taken over my life quite a bit. I feel incredibly lucky to have the opportunity to take this story out to a wider audience. However, as I have already said it will be nice to have my life back.

Obviously there are somethings I have to fundraise for. I can’t clear the publishing rights of the music or get DVD duplications processed without money. So I will be crowdfunding. This will enable me to raise funding to complete the project. Those that contribute and also meet certain criteria will receive a copy of the film (those interested should look out for the crowdfunding page all information and criteria will be clearly explained on the page).

The plan overall is to complete the film, first and foremost. This will be achieved by fundraising, clearing publishing rights, sorting paper work etc. The absolute date is still to be confirmed. However, I would say the end of this year at the latest. On release of the film copies will be sent to the funders/donators to the crowdfunding page, they will receive a limited edition of the DVD.

I will set up a Facebook page for ‘Ska’d by the music’, so that those interested can follow what is happening. The film will be entered into film festivals so dates of screenings will be posted so interested audiences will be aware of when and where it is being shown.

Distributors - Concord Media (they distribute other work of mine) are an educational ‘Not for Profit’ organisation, so I’m expecting that they will be interested in distribution. The Community Channel is also interested so a possible UK broadcast as well.

Synopsis: Ska’d by the music (Symarip story)

The creators of the ‘Skinhead Moonstomp’ album. The Jamaican band that engaged a generation of working class teenagers.

They were known as The Bees, Seven Letters, the Pyramids and Zubaba. In 1969 they would head straight into the British music charts with a Ska anthem to be remembered.

Not the first group of black musicians to appeal to a predominantly white audience. But this was different; Symarip were appealing to council estate kids.

Following the Nationality Act in 1948, many Jamaicans migrated to Britain in the hope of finding work. The outcome is well documented and not all found the country as welcoming as they had been led to believe.

However, leading into the mid to late 1960s, through working alongside each other in factories and visiting the same dance halls and clubs, white working class teenagers saw their own alienation and lack of opportunities, echoed in the young Jamaican counterparts.

MW: What sorts of ska / two-tone treasures can be found in your own record collection?

SW: Originally a lot of my records were on vinyl and like many of my generation I have the ‘One Step Beyond’… and The Specials, The Selecter, Bad Manners, The Beat as well as ‘The Dance Craze – The Best of British Ska...Live!’ album. Much of this has also been purchased on CD and downloads as well.

You will also find Prince Buster, Dandy Livingstone, Desmond Dekker, The Pioneers and of course, Symarip. I do love the originals and many of the covers. What a brilliant first album UB40 created with ‘Signing Off’. However, you can’t compete with Tony Tribe singing ‘Red Red Wine’.That first guitar string, like the strings of your heart. Always sends shivers down my spine.

MW: What's the best thing you've ( a ) read ( b ) watched and ( c ) listened to recently?

SW:

A) Read – I’ve found with the ongoing and non-escaping political scene at the moment I have been sent further into the world of fantasy. I do love vampire novels and science fiction. I am now on the final book of the Deborah Harkness All Souls Trilogy ‘The Book Of Life’. I got hooked on ‘A Discovery Of Witches’ because I know many of the buildings in Oxford that she writes about in the book. The idea of this history professor being a witch amused and appealed to me. So I’m on the last book in the trilogy, but haven’t been able to read as much as I would like.

B) Watched – I’m into boxsets. I have just finished watching the final of series six ‘The Walking Dead’ and found it very disturbing. Having said that, Andrew Lincoln is truly fantastic and I also love the strong female roles such as Danai Gurira’s stunning sword swirling Michonne. If you speak of fantasy often people just think you’re a nerd. Which of course I am, but wasn’t sure about this series in the beginning, it has grown on me. My husband had originally been very keen on watching it and zombies have never been my thing. However, what has engaged me is the concept of how society, humanity could, and let’s face it, would, probably break down. I find all the characters very believable, complex and scary as hell.

The other boxset recently watched was volume three of ‘House of Cards’. Amazing performances by Kevin Spacey and Robin Wright in this tale of corruption in the political arena. You begin to wonder about art imitating life, or visa versa.

Films I watched quite recently ‘Europa, Europa’ directed by Agnieszka Holland. Based on the 1989 autobiography of Solomon Perel (he also appears in it right at the end) it’s the story of a German-Jewish boy who escaped The Holocaust by masquerading not just as a non-Jew, but as an elite "Nazi" German. It is very intense at times, but also has dark humour. One dreamlike sequence shows Stalin and Hitler dancing together.

C) Listened to – Occasionally I listen to ‘The Craig Charles Funk And Soul Show’ on BBC Radio 6 Music and ‘Elaine Paige on Sunday’ on BBC Radio 2. Otherwise, it’s Classic FM in the car but I don’t listen to much radio. I admit though that I started tuning in to ‘The Archers’ on BBC Radio 4 when they had the Helen and Rob storyline going, but I often forget!

MW: How do you see the future of film making for independent production companies such as yours?

SW: I’m a freelance individual not a Limited Production company. So fortunately I don’t have to worry about employees.

The nature of funding has changed, smaller film agencies getting moved to bigger under one roof organisations. This signals regional film-makers missing out more and more on funding. Many film-makers are moving towards crowdfunding and other ways of finding support for their projects. Also technology is constantly changing, so I think how we watch films will also impact on the film-makers themselves.

MW: Aside from 'Symarip', any other film making projects in the pipeline?

SW: I am still pushing to get ‘Ska’d by the music’ completed so will be a while before I think about another personal project. However, I’m always looking for commissioned work and have a keen interest in history so we’ll have to see what the future holds.

MW: Where can we find out more on Woodward Media?

SW:

http://sharonfilmblo1.blogspot.co.uk/

https://twitter.com/SharonWoodward

https://www.facebook.com/woodwardmediacom/

© Mark Watkins / March 2017

1 note

·

View note

Photo

My immigrant family achieved the American dream. Then I started to question it.

In summer 2007, I returned home from my freshman year at Brown University to the new house my family had just bought in Florida. It had a two-car garage. It had a pool. I was on track to becoming an Ivy League graduate, with opportunities no one else in my family had ever experienced. I stood in the middle of this house and burst into tears. I thought: We’ve made it.

That moment encapsulated what I had always thought of the “American dream.” My parents had come to this country from Mexico and Ecuador more than 30 years before, seeking better opportunities for themselves. They worked and saved for years to ensure my two brothers and I could receive a good education and a solid financial foundation as adults. Though I can’t remember them explaining the American dream to me explicitly, the messaging I had received by growing up in the United States made me know that coming home from my first semester at a prestigious university to a new house meant we had achieved it.

And yet, now six years out of college and nearly 10 years past that moment, I’ve begun questioning things I hadn’t before: Why did I “make it” while so many others haven’t? Was this conventional version of making it what I actually wanted? I’ve begun to realize that our society’s definition of making it comes with its own set of limitations and does not necessarily guarantee all that I originally assumed came with the American dream package.

I interviewed several friends from immigrant backgrounds who had also reflected on these questions after achieving the traditional definition of success in the United States. Looking back, there were several things we misunderstood about the American dream. Here are a few:

1) The American dream isn’t the result of hard work. It’s the result of hard work, luck, and opportunity.

Looking back, I can’t discount the sacrifices my family made to get where we are today. But I also can’t discount specific moments we had working in our favor. One example: my second-grade teacher, Ms. Weiland. A few months into the year, Ms. Weiland informed my parents about our school’s gifted program. Students tracked into this program in elementary school would usually end up in honors and Advanced Placement classes in high school — classes necessary for gaining admission into prestigious colleges.

My parents, unfamiliar with our education system, didn’t understand any of this. But Ms. Weiland went out of her way to explain it to them. She also persuaded school administrators to test me for entrance into the program, and with her support, I eventually earned a spot.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that Ms. Weiland’s persistence ultimately influenced my acceptance into Brown University. No matter how hard I worked or what grades I received, without gifted placement I could never have reached the academic classes necessary for an Ivy League school. Without that first opportunity given to me by Ms. Weiland, my entire educational trajectory would have changed.

The philosopher Seneca said, “Luck is what happens when preparation meets opportunity.” But in the United States, too often people work hard every day, and yet never receive the opportunities that I did — an opportunity as simple as a teacher advocating on their behalf. Statistically, students of color remain consistently undiscovered by teachers who often, intentionally or not, choose mostly white, high-income students to enter advanced or “gifted” programs, regardless of their qualifications. Upon entering college, I met several students from across the country who also remained stuck within their education system until a teacher helped them find a way out.

Research has proved that these inconsistencies in opportunity exist in almost every aspect of American life. Your race can determine whether you interact with police, whether you are allowed to buy a house, and even whether your doctor believes you are really in pain. Your gender can determine whether you receive funding for your startup or whether your attempts at professional networking are effective. Your "foreign-sounding" name can determine whether someone considers you qualified for a job. Your family’s income can determine the quality of your public school or your odds that your entrepreneurial project succeeds.

These opportunities make a difference. They have created a society where most every American is working hard and yet only a small segment are actually moving forward. Knowing all this, I am no longer naive enough to believe the American dream is possible for everyone who attempts it. The United States doesn’t lack people trying. What it lacks is an equal playing field of opportunity.

2) Accomplishing the American dream can be socially alienating

Throughout my life, my family and I knew this uncomfortable truth: To better our future, we would have to enter spaces that felt culturally and racially unfamiliar to us. When I was 4 years old, my parents moved our family to a predominantly white part of town, so I could attend the county’s best public schools. I was often one of the only students of color in my gifted and honors programs. This trend continued in college and afterward: As an English major, I was often the only person of color in my literature and creative writing classes. As a teacher, I was often one of few teachers of color at my school or in my teacher training programs.

While attending Brown, a student of color once told me: “Our education is really just a part of our gradual ascension into whiteness.” At the time I didn’t want to believe him, but I came to understand what he meant: Often, the unexpected price for academic success is cultural abandonment.

In a piece for the New York Times, Vicki Madden described how education can create this “tug of war in [your] soul”:

To stay four years and graduate, students have to come to terms with the unspoken transaction: exchanging your old world for a new world, one that doesn’t seem to value where you came from. … I was keen to exchange my Western hardscrabble life for the chance to be a New York City middle-class museum-goer. I’ve paid a price in estrangement from my own people, but I was willing. Not every 18-year-old will make that same choice, especially when race is factored in as well as class.

So many times throughout my life, I’ve come home from classes, sleepovers, dinner parties, and happy hours feeling the heaviness of this exchange. I’ve had to Google cultural symbols I hadn’t understood in these conversations (What is “Harper’s”? What is “après-ski”?). At the same time, I remember using academia jargon my family couldn’t understand either. At a Christmas party, a friend called me out for using “those big Ivy League words” in a conversation. My parents had trouble understanding how independent my lifestyle had become and kept remarking on how much I had changed. Studying abroad, moving across the country for internships, living alone far away from family after graduating — these were not choices my Latin American parents had seen many women make.

An official from Brown told the Boston Globe that similar dynamics existed with many first-generation college students she worked with: “Often, [these students] come to college thinking that they want to return home to their communities. But an Ivy League education puts them in a different place — their language is different, their appearance is different, and they don’t fit in at home anymore, either.”

A Haitian-American friend of mine from college agreed: “After going to college, interacting with family members becomes a conflicted zone. Now you’re the Ivy League cousin who speaks a certain way, and does things others don’t understand. It changes the dynamic in your family entirely.”

A Latina friend of mine from Oakland felt this when she got accepted to the University of Southern California. She was the first person from her to family to leave home to attend college, and her conservative extended family criticized her for leaving home before marriage.

“One night they sat me down, told me my conduct was shameful and was staining the reputation of the family,” she told me, “My family thought a woman leaving home had more to do with her promiscuity than her desire for an education. They told me, ‘You’re just going to Los Angeles so you can have the freedom to be with whatever guy you want.’ When I think about what was most hard about college, it wasn’t the academics. It was dealing with my family’s disapproval of my life.”

We don’t acknowledge that too often, achievement in the United States means this gradual isolation from the people we love most. By simply striving toward American success, many feel forced to make to make that choice.

3) The American dream makes us focus single-mindedly on wealth and prestige

When I spoke to an Asian-American friend from college, he told me, “In the Asian New Jersey community I grew up in, I was surrounded by parents and friends whose mentality was to get high SAT scores, go to a top college, and major in medicine, law, or investment banking. No one thought outside these rigid tracks.” When he entered Brown, he followed these expectations by starting as a premed, then switching his major to economics.

This pattern is common in the Ivy League: Studies show that Ivy League graduates gravitate toward jobs with high salaries or prestige to justify the work and money we put into obtaining an elite degree. As a child of immigrants, there’s even more pressure to believe this is the only choice.

Of course, financial considerations are necessary for survival in our society. And it’s healthy to consider wealth and prestige when making life decisions, particularly for those who come from backgrounds with less privilege. But to what extent has this concern become an unhealthy obsession? For those who have the privilege of living a life based on a different set of values, to what extent has the American dream mindset limited our idea of success?

The Harvard Business Review reported that over time, people from past generations have begun to redefine success. As they got older, factors like “family happiness,” “relationships,” “balancing life and work,” and “community service” became more important than job titles and salaries. The report quoted a man in his 50s who said he used to define success as “becoming a highly paid CEO.” Now he defines it as “striking a balance between work and family and giving back to society.”