#Greg Lukianoff

Text

By: Jon Haidt

Published: Mar 9, 2023

In May 2014, Greg Lukianoff invited me to lunch to talk about something he was seeing on college campuses that disturbed him. Greg is the president of FIRE (the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression), and he has worked tirelessly since 2001 to defend the free speech rights of college students. That almost always meant pushing back against administrators who didn’t want students to cause trouble, and who justified their suppression of speech with appeals to the emotional “safety” of students—appeals that the students themselves didn’t buy. But in late 2013, Greg began to encounter new cases in which students were pushing to ban speakers, punish people for ordinary speech, or implement policies that would chill free speech. These students arrived on campus in the fall of 2013 already accepting the idea that books, words, and ideas could hurt them. Why did so many students in 2013 believe this, when there was little sign of such beliefs in 2011?

Greg is prone to depression, and after hospitalization for a serious episode in 2007, Greg learned CBT (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy). In CBT you learn to recognize when your ruminations and automatic thinking patterns exemplify one or more of about a dozen “cognitive distortions,” such as catastrophizing, black-and-white thinking, fortune telling, or emotional reasoning. Thinking in these ways causes depression, as well as being a symptom of depression. Breaking out of these painful distortions is a cure for depression.

What Greg saw in 2013 were students justifying the suppression of speech and the punishment of dissent using the exact distortions that Greg had learned to free himself from. Students were saying that an unorthodox speaker on campus would cause severe harm to vulnerable students (catastrophizing); they were using their emotions as proof that a text should be removed from a syllabus (emotional reasoning). Greg hypothesized that if colleges supported the use of these cognitive distortions, rather than teaching students skills of critical thinking (which is basically what CBT is), then this could cause students to become depressed. Greg feared that colleges were performing reverse CBT.

I thought the idea was brilliant because I had just begun to see these new ways of thinking among some students at NYU. I volunteered to help Greg write it up, and in August 2015 our essay appeared in The Atlantic with the title: The Coddling of the American Mind. Greg did not like that title; his original suggestion was “Arguing Towards Misery: How Campuses Teach Cognitive Distortions.” He wanted to put the reverse CBT hypothesis in the title.

After our essay came out, things on campus got much worse. The fall of 2015 marked the beginning of a period of protests and high-profile conflicts on campus that led many or most universities to implement policies that embedded this new way of thinking into campus culture with administrative expansions such as “bias response teams” to investigate reports of “microaggressions.” Surveys began to show that most students and professors felt that they had to self-censor. The phrase “walking on eggshells” became common. Trust in higher ed plummeted, along with the joy of intellectual discovery and sense of goodwill that had marked university life throughout my career.

Greg and I decided to expand our original essay into a book in which we delved into the many causes of the sudden change in campus culture. Our book focused on three “great untruths” that seemed to be widely believed by the students who were trying to shut down speech and prosecute dissent:

1. What doesn’t kill you makes you weaker

2. Always trust your feelings

3. Life is a battle between good people and evil people.

Each of these untruths was the exact opposite of a chapter in my first book, The Happiness Hypothesis, which explored ten Great Truths passed down to us from ancient societies east and west. We published our book in 2018 with the title, once again, of The Coddling of the American Mind. Once again, Greg did not like the title. He wanted the book to be called “Disempowered,” to capture the way that students who embrace the three great untruths lose their sense of agency. He wanted to capture reverse CBT.

The Discovery of the Gender-by-Politics Interaction

In September 2020, Zach Goldberg, who was then a graduate student at Georgia State University, discovered something interesting in a dataset made public by Pew Research. Pew surveyed about 12,000 people in March 2020, during the first month of the Covid shutdowns. The survey included this item: “Has a doctor or other healthcare provider EVER told you that you have a mental health condition?” Goldberg graphed the percentage of respondents who said “yes” to that item as a function of their self-placement on the liberal-conservative 5-point scale and found that white liberals were much more likely to say yes than white moderates and conservatives. (His analyses for non-white groups generally found small or inconsistent relationships with politics.)

I wrote to Goldberg and asked him to redo it for men and women separately, and for young vs. old separately. He did, and he found that the relationship to politics was much stronger for young (white) women. You can see Goldberg’s graph here, but I find it hard to interpret a three-way interaction using bar charts, so I downloaded the Pew dataset and created line graphs, which make it easier to interpret.

Here’s the same data, showing three main effects: gender (women higher), age (youngest groups higher), and politics (liberals higher). The graphs also show three two-way interactions (young women higher, liberal women higher, young liberals higher). And there’s an important three-way interaction: it is the young liberal women who are highest. They are so high that a majority of them said yes, they had been told that they have a mental health condition.

Figure 1. Data from Pew Research, American Trends Panel Wave 64. The survey was fielded March 19-24, 2020. Graphed by Jon Haidt.

In recent weeks—since the publication of the CDC’s report on the high and rising rates of depression and anxiety among teens—there has been a lot of attention to a different study that shows the gender-by-politics interaction: Gimbrone, Bates, Prins, & Keyes (2022), titled: “The politics of depression: Diverging trends in internalizing symptoms among US adolescents by political beliefs.” Gimbrone et al. examined trends in the Monitoring the Future dataset, which is the only major US survey of adolescents that asks high school students (seniors) to self-identify as liberal or conservative (using a 5-point scale). The survey asks four items about mood/depression. Gimbrone et al. found that prior to 2012 there were no sex differences and only a small difference between liberals and conservatives. But beginning in 2012, the liberal girls began to rise, and they rose the most. The other three groups followed suit, although none rose as much, in absolute terms, as did the liberal girls (who rose .73 points since 2010, on a 5-point scale where the standard deviation is .89).

Figure 2. Data from Monitoring the Future, graphed by Gimbrone et al. (2022). The scale runs from 1 (minimum) to 5 (maximum).

The authors of the study try to explain the fact that liberals rise first and most in terms of the terrible things that conservatives were doing during Obama’s second term, e.g.,

Liberal adolescents may have therefore experienced alienation within a growing conservative political climate such that their mental health suffered in comparison to that of their conservative peers whose hegemonic views were flourishing.

The progressive New York Times columnist Michelle Goldberg took up the question and wrote a superb essay making the argument that teen mental health is not and must not become a partisan issue. She dismissed Gimbrone et al.’s explanation as having a poor fit with their own data:

Barack Obama was re-elected in 2012. In 2013, the Supreme Court extended gay marriage rights. It was hard to draw a direct link between that period’s political events and teenage depression, which in 2012 started an increase that has continued, unabated, until today.

After examining the evidence, including the fact that the same trends happened at the same time in Britain, Canada, and Australia, Goldberg concluded that “Technology, not politics, was what changed in all these countries around 2012. That was the year that Facebook bought Instagram and the word “selfie” entered the popular lexicon.”

Journalist Matt Yglesias also took up the puzzle of why liberal girls became more depressed than others, and in a long and self-reflective Substack post, he described what he has learned about depression from his own struggles involving many kinds of treatment. Like Michelle Goldberg, he briefly considered the hypothesis that liberals are depressed because they’re the only ones who see that “we’re living in a late-stage capitalist hellscape during an ongoing deadly pandemic w record wealth inequality, 0 social safety net/job security, as climate change cooks the world,” to quote a tweet from the Washington Post tech columnist Taylor Lorenz. Yglesias agreed with Goldberg and other writers that the Lorenz explanation—reality makes Gen Z depressed—doesn’t fit the data, and, because of his knowledge of depression, he focused on the reverse path: depression makes reality look terrible. As he put it: “Mentally processing ambiguous events with a negative spin is just what depression is.”

Yglesias tells us what he has learned from years of therapy, which clearly involved CBT:

It’s important to reframe your emotional response as something that’s under your control:

• Stop saying “so-and-so made me angry by doing X.”

• Instead say “so-and-so did X, and I reacted by becoming angry.”

And the question you then ask yourself is whether becoming angry made things better? Did it solve the problem?

Yglesias wrote that “part of helping people get out of their trap is teaching them not to catastrophize.” He then described an essay by progressive journalist Jill Filipovic that argued, in Yglesias’s words, that “progressive institutional leaders have specifically taught young progressives that catastrophizing is a good way to get what they want.”

Yglesias quoted a passage from Filipovic that expressed exactly the concern that Greg had expressed to me back in 2014:

I am increasingly convinced that there are tremendously negative long-term consequences, especially to young people, coming from this reliance on the language of harm and accusations that things one finds offensive are “deeply problematic” or even violent. Just about everything researchers understand about resilience and mental well-being suggests that people who feel like they are the chief architects of their own life — to mix metaphors, that they captain their own ship, not that they are simply being tossed around by an uncontrollable ocean — are vastly better off than people whose default position is victimization, hurt, and a sense that life simply happens to them and they have no control over their response.

I have italicized Filipovic’s text about the benefits of feeling like you captain your own ship because it points to a psychological construct with a long history of research and measurement: Locus of control. As first laid out by Julian Rotter in the 1950s, this is a malleable personality trait referring to the fact that some people have an internal locus of control—they feel as if they have the power to choose a course of action and make it happen, while other people have an external locus of control—they have little sense of agency and they believe that strong forces or agents outside of themselves will determine what happens to them. Sixty years of research show that people with an internal locus of control are happier and achieve more. People with an external locus of control are more passive and more likely to become depressed.

How a Phone-Based Childhood Breeds Passivity

There are at least two ways to explain why liberal girls became depressed faster than other groups at the exact time (around 2012) when teens traded in their flip phones for smartphones and the girls joined Instagram en masse. The first and simplest explanation is that liberal girls simply used social media more than any other group. Jean Twenge’s forthcoming book, Generations, is full of amazing graphs and insightful explanations of generational differences. In her chapter on Gen Z, she shows that liberal teen girls are by far the most likely to report that they spend five or more hours a day on social media (31% in recent years, compared to 22% for conservative girls, 18% for liberal boys, and just 13% for conservative boys). Being an ultra-heavy user means that you have less time available for everything else, including time “in real life” with your friends. Twenge shows in another graph that from the 1970s through the early 2000s, liberal girls spent more time with friends than conservative girls. But after 2010 their time with friends drops so fast that by 2016 they are spending less time with friends than are conservative girls. So part of the story may be that social media took over the lives of liberal girls more than any other group, and it is now clear that heavy use of social media damages mental health, especially during early puberty.

But I think there’s more going on here than the quantity of time on social media. Like Filipovic, Yglesias, Goldberg, and Lukianoff, I think there’s something about the messages liberal girls consume that is more damaging to mental health than those consumed by other groups.

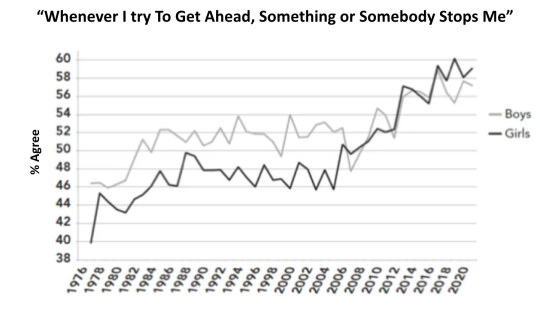

The Monitoring the Future dataset happens to have within it an 8-item Locus of Control scale. With Twenge’s permission, I reprint one such graph from Generations showing responses to one of the items: “Every time I try to get ahead, something or somebody stops me.” This item is a good proxy for Filipovic’s hypothesis about the disempowering effects of progressive institutions. If you agree with that item, you have a more external locus of control. As you can see in Figure 3, from the 1970s until the mid-2000s, boys were a bit more likely to agree with that item, but then girls rose to match boys, and then both sexes rose continuously throughout the 2010s—the era when teen social life became far more heavily phone-based.

Figure 3. Percentage of boys and girls (high school seniors) who agree with (or are neutral about) the statement “Every time I try to get ahead, something or somebody stops me.” From Monitoring the Future, graphed by Jean Twenge in her forthcoming book Generations.

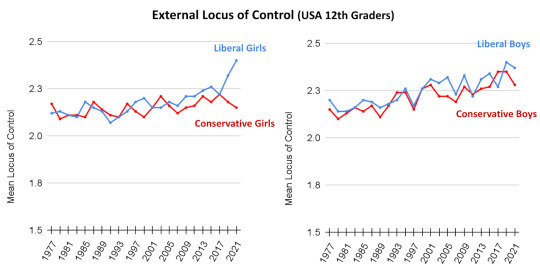

When the discussion of the gender-by-politics interaction broke out a few weeks ago, I thought back to Twenge’s graph and wondered what would happen if we broke up the sexes by politics. Would it give us the pattern in the Gimbrone et al. graphs, where the liberal girls rise first and most? Twenge sent me her data file (it’s a tricky one to assemble, across the many years), and Zach Rausch and I started looking for the interaction. We found some exciting hints, and I began writing this post on the assumption that we had a major discovery. For example, Figure 4 shows the item that Twenge analyzed. We see something like the Gimbrone et al. pattern in which it’s the liberal girls who depart from everyone else, in the unhealthy (external) direction, starting in the early 2000s.

Figure 4. Percentage of liberal and conservative high school senior boys (left panel) and girls (right panel) who agree with the statement “Every time I try to get ahead, something or somebody stops me.” From Monitoring the Future, graphed by Zach Rausch.

It sure looks like the liberal girls are getting more external while the conservative girls are, if anything, trending slightly more internal in the last decade, and the boys are just bouncing around randomly. But that was just for this one item. We also found a similar pattern for a second item, “People like me don’t have much of a chance at a successful life.” (You can see graphs of all 8 items here.)

We were excited to have found such clear evidence of the interaction, but when we plotted responses to the whole scale, we found only a hint of the predicted interaction, and only in the last few years, as you can see in Figure 5. After trying a few different graphing strategies, and after seeing if there was a good statistical justification for dropping any items, we reached the tentative conclusion that the big story about locus of control is not about liberal girls, it’s about Gen Z as a whole. Everyone—boys and girls, left and right—developed a more external locus of control gradually, beginning in the 1990s. I’ll come back to this finding in future posts as I explore the second strand of the After Babel Substack: the loss of “play-based childhood” which happened in the 1990s when American parents (and British, and Canadian) stopped letting their children out to play and explore, unsupervised. (See Frank Furedi’s important book Paranoid Parenting. I believe that the loss of free play and self-supervised risk-taking blocked the development of a healthy, normal, internal locus of control. That is the reason I teamed up with Lenore Skenazy, Peter Gray, and Daniel Shuchman to found LetGrow.org.)

Figure 5. Locus of Control has shifted slightly but steadily toward external since the 1990s. Scores are on a 5-point scale from 1 = most internal to 5 = most external.

We kept looking in the Monitoring the Future dataset and the Gimbrone et al. paper for other items that would allow us to test Filipovic’s hypothesis. We found an ideal second set of variables: The Monitoring the Future dataset has a set of items on “self derogation” which is closely related to disempowerment, as you can see from the four statements that comprise the scale:

I feel I do not have much to be proud of.

Sometimes I think I am no good at all.

I feel that I can't do anything right.

I feel that my life is not very useful.

Gimbrone et al. had graphed the self-derogation scale, as you can see in their appendix (Figure A.4). But Zach and I re-graphed the original data so that we could show a larger range of years, from 1977 through 2021. As you can see in Figure 6, we find the gender-by-politics interaction. Once again, and as with nearly all of the mental health indicators I examined in a previous post, there’s no sign of trouble before 2010. But right around 2012 the line for liberal girls starts to rise. It rises first, and it rises most, with liberal boys not far behind (as in Gimbrone et al.).

Figure 6. Self-derogation scale, averaging four items from the Monitoring the Future study. Graphed by Zach Rausch. The scale runs from 1 (strongly disagree with each statement) to 5 (strongly agree).

In other words, we have support for Filipovic’s “captain their own ship” concern, and for Lukianoff’s disempowerment concern: Gen Z has become more external in its locus of control, and Gen Z liberals (of both sexes) have become more self-derogating. They are more likely to agree that they “can’t do anything right.” Furthermore, most of the young people in the progressive institutions that Filipovic mentioned are women, and that has become even more true since 2014 when, according to Gallup data, young women began to move to the left while young men did not move either way. As Gen Z women became more progressive and more involved in political activism in the 2010s, it seems to have changed them psychologically. It wasn’t just that their locus of control shifted toward external—that happened to all subsets of Gen Z. Rather, young liberals (including young men) seem to have taken into themselves the specific depressive cognitions and distorted ways of thinking that CBT is designed to expunge.

But where did they learn to think this way? And why did it start so suddenly around 2012 or 2013, as Greg observed, and as Figures 2 and 6 confirm?

Tumblr Was the Petri Dish for Disempowering Beliefs

I recently listened to a brilliant podcast series, The Witch Trials of J. K. Rowling, hosted by Megan Phelps-Roper, created within Bari Weiss’s Free Press. Phelps-Roper interviews Rowling about her difficult years developing the Harry Potter stories in the early 1990s, before the internet; her rollout of the books in the late 90s and early 2000s, during the early years of the internet; and her observations about the Harry Potter superfan communities that the internet fostered. These groups had streaks of cruelty and exclusion in them from the beginning, along with a great deal of love, joy, and community. But in the stunning third episode, Phelps-Roper and Rowling take us through the dizzying events of the early 2010s as the social media site Tumblr exploded in popularity (reaching its peak in early 2014), and also in viciousness. Tumblr was different from Facebook and other sites because it was not based on anyone’s social network; it brought together people from anywhere in the world who shared an interest, and often an obsession.

Phelps-Roper interviewed several experts who all pointed to Tumblr as the main petri dish in which nascent ideas of identity, fragility, language, harm, and victimhood evolved and intermixed. Angela Nagle (author of Kill All Normies) described the culture that emerged among young activists on Tumblr, especially around gender identity, in this way:

There was a culture that was encouraged on Tumblr, which was to be able to describe your unique non-normative self… And that’s to some extent a feature of modern society anyway. But it was taken to such an extreme that people began to describe this as the snowflake [referring to the idea that each snowflake is unique], the person who constructs a totally kind of boutique identity for themselves, and then guards that identity in a very, very sensitive way and reacts in an enraged way when anyone does not respect the uniqueness of their identity.

Nagle described how on the other side of the political spectrum, there was “the most insensitive culture imaginable, which was the culture of 4chan.” The communities involved in gender activism on Tumblr were mostly young progressive women while 4Chan was mostly used by right-leaning young men, so there was an increasingly gendered nature to the online conflict. The two communities supercharged each other with their mutual hatred, as often happens in a culture war. The young identity activists on Tumblr embraced their new notions of identity, fragility, and trauma all the more tightly, increasingly saying that words are a form of violence, while the young men on 4chan moved in the opposite direction: they brandished a rough and rude masculinity in which status was gained by using words more insensitively than the next guy. It was out of this reciprocal dynamic, the experts on the podcast suggest, that today’s cancel culture was born in the early 2010s. Then, in 2013, it escaped from Tumblr into the much larger Twitterverse. Once on Twitter, it went national and even global (at least within the English-speaking countries), producing the mess we all live with today.

I don’t want to tell that entire story here; please listen to the Witch Trials podcast for yourself. It is among the most enlightening things I’ve read or heard in all my years studying the American culture war (along with Jon Ronson’s podcast Things Fell Apart). I just want to note that this story fits perfectly with both the timing and the psychology of Greg’s reverse CBT hypothesis.

Implications and Policy Changes

In conclusion, I believe that Greg Lukianoff was exactly right in the diagnosis he shared with me in 2014. Many young people had suddenly—around 2013—embraced three great untruths:

They came to believe that they were fragile and would be harmed by books, speakers, and words, which they learned were forms of violence (Great Untruth #1).

They came to believe that their emotions—especially their anxieties—were reliable guides to reality (Great Untruth #2).

They came to see society as comprised of victims and oppressors—good people and bad people (Great Untruth #3).

Liberals embraced these beliefs more than conservatives. Young liberal women adopted them more than any other group due to their heavier use of social media and their participation in online communities that developed new disempowering ideas. These cognitive distortions then caused them to become more anxious and depressed than other groups. Just as Greg had feared, many universities and progressive institutions embraced these three untruths and implemented programs that performed reverse CBT on young people, in violation of their duty to care for them and educate them.

I welcome challenges to this conclusion from scholars, journalists, and subscribers, and I will address such challenges in future posts. I must also repeat that I don’t blame everything on smartphones and social media; the other strand of my story is the loss of play-based childhood, with its free play and self-governed risk-taking. But if this conclusion stands (along with my conclusions in previous posts), then I think there are two big policy changes that should be implemented as soon as possible:

1) Universities and other schools should stop performing reverse CBT on their students

As Greg and I showed in The Coddling of the American Mind, most of the programs put in place after the campus protests of 2015 are based on one or more of the three Great Untruths, and these programs have been imported into many K-12 schools. From mandatory diversity training to bias response teams and trigger warnings, there is little evidence that these programs do what they say they do, and there are some findings that they backfire. In any case, there are reasons, as I have shown, to worry that they teach children and adolescents to embrace harmful, depressogenic cognitive distortions.

One initiative that has become popular in the last few years is particularly suspect: efforts to tell college students to avoid common English words and phrases that are said to be “harmful.” Brandeis University took the lead in 2021 with its “oppressive language list.” Brandeis urged its students to stop saying that they would “take a stab at” something because it was unnecessarily violent. For the same reason, they urged that nobody ask for a “trigger warning” because, well, guns. Students should ask for “content warnings” instead, to keep themselves safe from violent words like “stab.” Many universities have followed suit, including Colorado State University, The University of British Columbia, The University of Washington, and Stanford, which eventually withdrew its “harmful language list” because of the adverse publicity. Stanford had urged students to avoid words like “American,” “Immigrant,” and “submit,” as in “submit your homework.” Why? because the word “submit” can “imply allowing others to have power over you.” The irony here is that it may be these very programs that are causing liberal students to feel disempowered, as if they are floating in a sea of harmful words and people when, in reality, they are living in some of the most welcoming and safe environments ever created.

2) The US Congress should raise the age of “internet adulthood” from 13 to 16 or 18

What do you think should be the minimum age at which children can sign a legally binding contract to give away their data and their rights, and expose themselves to harmful content, without the consent or knowledge of their parents? I asked that question as a Twitter poll, and you can see the results here:

Image: See my original tweet.

Of course, this poll of my own Twitter followers is far from a valid survey, and I phrased my question in a leading way, but my phrasing was an accurate statement of today’s status quo. I think that most people now understand that the age of 13, which was set back in 1998 when we didn’t know what the internet would become, is just too low, and it is not even enforced. When my kids started 6th grade in NYC public schools, they each told me that “everyone” was on Instagram.

We are now 11 years into the largest epidemic of adolescent mental illness ever recorded. I know so many families that have been thrown into fear and turmoil by a child’s suicide attempt. You probably do too, given that the recent CDC report tells us that one in ten adolescents now say they have made an attempt to kill themselves. It is hitting all political and demographic groups. The evidence is abundant that social media is a major cause of the epidemic, and perhaps the major cause. It's time we started treating social media and other apps designed for “engagement” (i.e., addiction) like alcohol, tobacco, and gambling, or, because they can harm society as well as their users, perhaps like automobiles and firearms. Adults should have wide latitude to make their own choices, but legislators and governors who care about mental health, women’s health, or children’s health need to step up.

It’s not enough to find more money for mental health services, although that is sorely needed. In addition, we must shut down the conveyer belt so that today’s toddlers will not suffer the same fate in twelve years. Congress should set a reasonable minimum age for minors to sign contracts and open accounts without explicit parental consent, and the age needs to be after teens have progressed most of the way through puberty. (The harm caused by social media seems to be greatest during puberty.) If Congress won’t do it then state legislatures should act. There are many ways to rapidly verify people’s ages online, and I’ll discuss age verification processes in a future post.

In conclusion: All of Gen Z got more anxious and depressed after 2012. But Lukianoff’s reverse CBT hypothesis is the best explanation I have found for Why the mental health of liberal girls sank first and fastest.

#Jonathan Haidt#Greg Lukianoff#Reverse CBT#reverse cognitive behavioral therapy#cognitive behavioral therapy#emotional fragility#fragility#emotional reasoning#external locus#internal locus#victimhood#victimhood culture#Generation Z#Gen Z#anxiety#depression#mental health#mental health issues#trauma#personal identity#hellsite#Tumblr culture#religion is a mental illness

320 notes

·

View notes

Text

American progressives seem largely unaware that the views American conservatives espouse—like traditional religious norms, sexual morality, and intergroup loyalty—are actually far more common in the rest of the world. This fact is expertly pointed out in Jonathan Haidt's 2012 masterwork The Righteous Mind.

Outside of these myopic urban and academic bubbles in America, progressive ideas are exceptionally rare in the scheme of things. In his 2020 book The WEIRDest People in the World, Harvard evolutionary biologist Joseph Heinrich points out that American progressives are outliers or WEIRDos (Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic) in the scheme of human history and the modern world.

There's something obnoxiously small-minded and elitist in the assumption that, just by some strange historical coincidence, you or your group is somehow the first to land on the universal truths of morality. And yet many American progressives seem to at least subconsciously hold this to be self-evident. It's not that morality should be decided by a global majority vote, but a self-awareness of WEIRDness is hugely lacking.

–Greg Lukianoff & Rikki Schlott, The Canceling of the American Mind: Cancel Culture Undermines Trust and Threatens Us All — But There Is a Solution

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the late 1970s, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) famously—and controversially—defended the right of neo-Nazis to march through the Chicago suburb of Skokie, Illinois, which was home to many Holocaust survivors. It was a defining moment for the group and for the idea that free speech, no matter how vile, must be guaranteed to everyone.

#ACLU#FIRE#Greg Lukianoff#Reason#ReasonInterview#NICK GILLESPIE#Free Speech#First Amendment#Civil Liberties

1 note

·

View note

Text

— The Canceling of the American Mind by Greg Lukianoff and Rikki Scholott

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lukianoff argues that Americans would be better off “if we loosened elite higher education’s grip on society.” After “Coddling” came out, he says that heads of corporations and nonprofits called him to privately complain that young graduates from top schools were creating “serious problems” in the workplace by fixating on “minor interaction problems” with each other or with the institution itself. “My answer is, ‘Could you please tell the world that?’” says Lukianoff. “People need to know that the kind of product coming out of these elite schools is unworkable.”

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

HBO Real Time Dec. 8, 2023

[[MORE]]

The Interview:

Greg Lukianoff is the President and CEO of the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) and co-author of The Canceling of the American Mind: Cancel Culture Undermines Trust and Threatens Us All—But There Is a Solution. He writes about free speech, academic freedom, Cancel Culture and more on Substack.

Follow: @glukianoff

The Panel:

Jane Ferguson is an award-winning Special Correspondent for PBS NewsHour, contributor to The New Yorker, and author of the book, No Ordinary Assignment.

Follow: @JaneFerguson5

John Avlon is a senior Political Analyst and anchor for CNN and author of Lincoln and the Fight for Peace.

Follow: @JohnAvlon

Watch Bill and his guests continue their conversation on Overtime, airing Fridays at 11:30pm on CNN’s “Laura Coates Live” and Saturdays on the Real Time YouTube channel.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

This guy makes an overlooked point. The roots of Cancel Culture are psychological, not political. The solution he suggests is widespread use of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. I would specifically suggest Dialectical Behavioral Therapy.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The abstraction of privilege

BY ADOLFO ARANJUEZ | RIGHT NOW | 27 June 2017

An academic friend of mine once mentioned in passing that he feared “privilege-checking” had become a “secular religion”. Granted, he’s a white cisgender man – one employed, on salary, as an “intellectual” – so, depending on who you ask, his assertion is perhaps unsurprising. But he’s also queer, so that must count for something when weighing up his credibility in this debate. I proceeded to defend privilege analysis as a critical tool for making sense of society’s matrix of favour and disadvantage – for coming at life with an awareness of your and others’ possible impediments. But, despite the impassioned thrust of my retort, the intellectual damage had been done: was he right?

I had myself grown wary of the direction identity politics (IdPol) had taken of late. I’d first arrived at this position last year, sometime during my tenure as a Right Now columnist; ostensibly covering social-justice issues in the arts and media, what I eventually found myself doing was expounding on issues relating to IdPol – the school of thought that anchors action and analysis on societal labels relating to race, class, gender, sexuality and psychology, among others. I was constantly immersed in the discursive world of such labels, so it was inevitable that I began questioning the bases of my own position. I was even spurred to write a cautionary piece on the destructive tendencies of what’s been called the “Oppression Olympics” among progressives.

Today, my position is more crystallised than ever. IdPol has indeed become less like “a ‘road’ that facilitates the direction of discourse”, as I’d written back then, and “more like a ‘fence’ that cordons off certain people and ideas”. There is, echoing my friend’s foreboding, something incredibly proscriptive about IdPol – not unlike the rigidity of the Ten Commandments – and many of its “devotees” have become evangelical in their approach and dogmatic in their beliefs.

I’m not alone in thinking this, either. New York Magazine’s Andrew Sullivan has written that, in the IdPol schema, privilege is reminiscent of Judeo-Christianity’s “original sin”, positioning minorities – as the chosen ones free of this sin – as unassailable bearers of virtue and moral authority. There’s an unhealthy all-or-nothing bent to IdPol’s modus operandi, too; as Thembani Mdluli writes, there’s a tendency for one “wrong” move to tarnish a person’s entire reputation. This was demonstrated by the recent attacks on Nigerian feminist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, who (indeed damagingly) argued that trans women enjoyed some male privilege and are therefore less oppressed than women assigned female at birth.

IdPol is, like religion, a theoretical system that has, at best, iffy implications when put in practice.

In a now-infamous long-read for The Atlantic, Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt go so far as to allege that IdPol – in this case, as expressed through advocacy for trigger warnings in university course material – is characterised by a “vindictive protectiveness”. While in theory, they argue, IdPol’s staunchest adherents are driven by inclusiveness, in reality they end up spending more effort punishing those who stand in the way of their war against oppression. And, instead of confronting stances and actions they deem destructive, these people opt for demonising opponents wholesale and encouraging avoidance.

Certainly, their essay is not without its detractors. But they do raise a valid point: if problematic views aren’t challenged – if they’re merely silenced or ignored – they find more impetus to, in Mdluli’s words, “fester and spread”.

Admittedly, it’s never prudent to employ broad brushstrokes. IdPol is an effective framework for diagnosing what’s wrong with society. The many ills it brings to light – hate-based language, continued colonial violence, inequity based on sociopolitical marker – require redress. But it’s not a viable methodology; it is, like religion, a theoretical system that has, at best, iffy implications when put in practice.

I’m interested in interrogating IdPol’s pervasive but problematic essentialism. The argument goes that inequality exists as a result of unjust, but not unchangeable, structures built into society: racialisation is relative to a white centre; sexuality and gender are performative. Put another way, as Michel Foucault outlined in “The Subject and Power”, each person is a subject possessing agency – the main “protagonist” in the “stories” of our lives, so to speak – but is also subject to external factors like ideology, culture and other people. If the society is changed, therefore, constructed identities, and any marginalisation that arises from them, are likewise changed.

But by designating a person an irrevocable identity label and making immediate judgments about their political viability, their ethical worth, based on such a taxonomy – as IdPol’s devotees do – IdPol undermines its own core motivation to counteract destructive societal forces.

***

I’ve always been interested in the way the brain works – and in the way the brain works on, with and through ideas. So it’s no wonder that I’ve found myself enamoured of IdPol: it provides a vibrant battleground for pitting ideas against one another, as it’s through terminology that we formulate our identities. The frequent online tussles about the “right” gender and sexuality labels, and whether someone from the “wrong” ethnic group can deploy a piece of slang, are micro-arenas for identity expression, with individuals imbuing words and concepts with political potency.

It’s worth noting that abstractions such as these – concepts, definitions and labels used to “map” the world – are, on a more fundamental level, central to cognition: this is how the brain makes our environment digestible. It’s well established in the psychological institution that, as part of the process of comprehension, the brain inevitably breaks down the world’s complexity into simpler components and “weeds out” less-important information – if at least momentarily. This is also highlighted by what’s known as “Bloom’s Taxonomy” in pedagogical circles, with conventional teaching practice presupposing that “lower-order” learning (such as basic rules and definitions) must precede more complicated cognitive tasks (such as analysis, evaluation and creation).

From a socio-philosophical standpoint, psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan analysed how children’s acquisition of language – their entry into what he calls the Symbolic realm – imposes more and more boundaries on the otherwise-boundless Real (external reality) and gives shape to the amorphous, prelinguistic Imaginary sphere (instinct, fantasy, desire). We see, then, how the world is given “order” through arbitrary parameters grounded in language – toys are just generic “things” until we designate them as being “for children’s play”, and all toys are for all children unless we impose a distinction between “boys’ toys” and “girls’ toys”.

But this cognitive process is a mere step towards the ultimate goal of understanding; after we have grasped seemingly disparate concepts, we must link them back together into a larger epistemic system. Yet staunch identity-politicians fall prey to what philosopher William James has termed “vicious abstractionism”: the problematic tendency to treat abstractions of something as the thing-in-itself. We forget that we ourselves came up with the notions of “boys’ toys” and “girls’ toys”. Worse, we begin to think that this distinction is inexorable – the way it’s always been.

IdPol appears to have taken the second-wave feminist mantra “the personal is political” to a perilous extreme: whereas once it was a slogan for solidarity, foregrounding the shared struggle of marginalised individuals, it now seems to presuppose that a single person’s lived experience of disadvantage can conceptually represent those of an entire minority group. As I’d argued in “Oppression Olympics”, the logical extension of this contentious idea is that a lack of firsthand experience of the struggle-in-question means an outsider is unable to contribute to discourse or action, or to ever authentically depict that point-of-view.

Another outcome of this idea are appeals to “diversity”, channelled into conflicts over representation in art and media. Representation matters – it is a powerful way to normalise and validate lived realities. We learn about the world from cultural products; they prompt us on what and how to think. And under- or non-representation in art and media, known as “symbolic annihilation”, has a demonstrable correlation with low self-esteem among minorities.

But these works of art and media are also vehicles for ideology. They can be insidiously fashioned to depict certain forms of life as more legitimate or valuable than others – and, more significantly, can be geared towards capitalist consumption, with advertising becoming ever more influential in exploiting desire. The mere fact of being represented is not inherently good; being reduced to stereotypes or clichés can be even more damaging than absence.

And, as we of the left especially fall prey to vicious abstractionism, we find ourselves focusing more of our energies on “little wins” within this ideational battleground. We associate individual empowerment, as in “choice feminism”, with liberation on a broad scale. We celebrate breadcrumbs of diverse representation, as when characters are identified as queer. We assume that clicktivism – via Change.org boycotts against blackface and comment-thread debates where a person is “publicly shamed” for a single terminology misstep – is an effective substitute for real-world action. We advocate for quotas and parity in workplaces and witness the rise of diversity officers and pluralist “streams” in organisations and events that remain largely homogenous.

Professor Dafina-Lazarus Stewart, who identifies as nonbinary, describes such motions for diversity as embodying the politics of appeasement. Here, inclusion is targeted via superficially progressive measures while also ensuring that the broader institution remains unchanged. Researcher Tania Canas puts forward a similar perspective, arguing that the notion of “authenticity” in diversity discourse – whereby an individual from a marginalised group is framed as representative of that entire group – is, in fact, hindering, as it fallaciously presumes a unified experience among the marginalised.

Moreover, such “authentic” perspectives tend to be understood as existing counter to those of the dominant group; notions such as “person of colour” (which implies “white” as neutral) and “culturally and linguistically diverse” (as code for “non-Anglo” and “non-English-speaking”) immediately come to mind. In this way, IdPol’s fight for diversity inadvertently allies itself with subjugation, forever defining minority experiences and values in opposition to those in power; as negation, they affirm the existence of that which they negate.

***

As part of my recently published interview for Liminal magazine, I spoke about my practice as an emerging dancer and my love for hip-hop/urban dance. The interviewer asked me what my thoughts were on cultural appreciation versus appropriation, particularly in light of the genre’s origins in the African-American community. I sidestepped the question because I worried I couldn’t do it justice; moreover, I didn’t feel I had skin in the game to make a judgment call, given I wasn’t from the “right” cultural group, nor was I responsible for initiating the artistic exchange. I was merely a participant.

Maybe I’m part of the problem. The debate surrounding cultural appropriation is founded on tricky notions of cultural ownership, which is understandable considering the history of theft and exploitation suffered by minorities as a result of colonialism.

youtube

In a YouTube video about black hair and culture, African-American actor Amandla Stenberg addresses cultural appropriation, explaining that it’s harmful to pillage artefacts from a marginalised group, without giving due respect to the people of that group, because it magnifies disadvantage and exclusion. Beyond the adoption of black hairstyles, another salient example is white musician Macklemore’s winning Best Rap Album at the 2014 Grammys, after which he admitted to feeling as though he’d “robbed” contender Kendrick Lamar of the accolade.

Yet, as Cultural Appropriation and the Arts author James O. Young writes, the issue also hinges on the notion of permissions; if an authoritative member of the group “signs off” on a particular instance of cultural exchange, then all is well. But this hardly broaches the difficulty of establishing who can rightfully occupy such a position of authority. It’s a multifarious debate to wade into, with no definitive answers but lots of diverging opinions. Nevertheless, the idea that cultural appropriation is always immediately contemptible retains currency in IdPol circles.

In a New Yorker article, Elizabeth Kolbert argues that impressions, once formed, are difficult to dislodge, even in the face of counterarguments and even when individuals wish to. She cites cognitive scientists Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber, whose 2017 book The Enigma of Reason examines how rationality evolved in humans to ensure our species’ survival via enforced diplomacy: there’s safety in numbers, so we all had to get along by whatever means necessary. As a result, humans accept ideas – even when they aren’t the most sound or valid – if they have traction among the collective.

This idea isn’t entirely new. In the mid-twentieth century, George Herbert Mead studied how the cyclical relationship between language and our perceptions of reality are underpinned by the human drive to belong: group identity is pivotal to how we form and employ concepts. Ultimately, he contends, the way we use reason – the way we think, how we express what we think – betrays what group/s we (believe we) belong to. The more ardently we assert and adhere to group beliefs, the more deeply rooted our professed membership becomes.

The flipside of this form of “social rationalising” is the increasing difficulty of entertaining views that deviate from the group’s, for fear of becoming a pariah. Kolbert recounts how it became pragmatic for humans to implement a “division of cognitive labour”. As populations became larger, and societies more complex, it became less and less important to fully understand the mechanics of daily life. But, while this is prudent when it comes to toilets or trains or painkillers (we don’t need to know how these work to be able to properly use them), a lack of understanding is poisonous when it comes to civic participation: evaluating ethical ideas requires a grasp on how these ideas came about, how they impact on others, and how they themselves can be fallible.

When the desire for group belonging combines with the division of cognitive labour in the political arena, then, what we can end up with are group-enforced “truths” of varying cogency – not unlike religious dogma.

I don’t think many would question the orthodoxy that we must protect minorities from any harm or exploitation that cultural appropriation may wreak. In the case of black culture, some permissions have been given: speaking to Bullett, rapper Mykki Blanco responds to the mainstream-isation of hip-hop by celebrating the melding of cultural aesthetics; in the same article, artist/writer Juliana Huxtable expresses weariness regarding “conversations that ricochet between angry accusation and dismissive arrogance”, championing the role of education and earnest cultural appreciation. In IdPol circles, an oft-bandied catchcry is that “intent is less important than impact” – but, considering the complexity of the debate and the voices that have contributed to it, why should intent’s significance be downplayed? And how is impact credibly measured?

And as Conor Friedersdorf challenges, when an outsider engages with the history of an artefact, educates themselves deeply, seeks permissions, and contributes positively to the examination and discussion of that culture, surely they are not deserving of censure.

Without a deeper understanding of the whys and wherewithals of such “rules”, conflicts between opposing factions inevitably become difficult to resolve. Without a handle on the larger whole of which these abstracted ideas are part, group-based thinking can easily devolve into groupthink, fuelled by the very potent fear of being ostracised for failing to display allegiance to our comrades.

**

The 2017 live-action Hollywood remake of Japanese manga Ghost in Shell bombed at the US box office, following the backlash surrounding its “whitewashed” casting (something Paramount itself has partly owned up to). This has been touted as evidence of IdPol’s viability as a tool for social change. Certainly, the speed and sheer volume of articles calling out the issue, compounded by the voraciousness of social media outrage against the casting of Scarlett Johansson as lead, attest to how extensively digital technologies possess the potential to empower the otherwise-marginalised.

But they also birth insularity. In their provocation for The Channel’s “LGBTQIA+ in Australia” panel earlier this year, which I also spoke at, trans commentator Fury counselled against the ageism and classism of contemporary IdPol, which presupposes that everyone should already know the “right” terms of discourse and is up to speed with the minutiae of every social-justice debate – immediately condemning those who do not. Fury also quoted trans activist Starlady, who is “saddened by the exponential growth of ‘call-out culture’” and warns that “we are using the politics of privilege as a means to engage in lateral violence”. Gay rights advocate Dennis Altman expressed similar sentiments in a 2016 Meanjin essay, writing that, as a member of the older generation, he has felt alienated by the overwhelming pace at which IdPol evolves today.

Certainly, keeping abreast of the changes to IdPol discourse rests on the expectation that we possess not only access to the internet, but also the time, energy and ability to wade through the various Tumblrs and other online sources in which these discussions are playing out. But beyond this, it’s important to recognise how new media themselves have altered the way we engage with and evaluate information in the first place.

The Guardian editor-in-chief Katharine Viner argues that, in the age of online and social media, “truth” has become tied to what each person feels is true. This has arisen largely because new media have made it easier for a multitude of perspectives to disseminate – the contemporary landscape is burdened with anti-intellectualism, tempered by the ability of anyone, expert or otherwise, to publish on a topic online. This gives rise to what she calls an “information cascade”, whereby people share information that they agree with (no matter the veracity) to feel societally involved and in-the-know.

Social media platforms such as Facebook can analyse these patterns of behaviour using algorithms, which keep track of what types of content users do, and don’t, like to engage with. Due to the commercial imperative to retain users on the platform, to maximise advertising revenue, Facebook will feed users content similar to what they’ve already “liked”, inadvertently reinforcing their extant beliefs. As information cascades grow, the drive to share and feel belonging becomes ever more powerful.

And, as communications professor Joshua Meyrowitz has proposed, such online engagement creates “glocalities” that allow us to perceive our immediate, subjective realities as integral parts of a more encompassing world. This, arguably, is “the personal is political” in its most abstracted form: everyone is “entitled to an opinion” – so goes the oft-cited defence of freedom of expression – and now, with new media, they have populist platforms with which to reach others in the global community who share this opinion.

In his 1982 book Orality and Literacy, Walter J. Ong examined how the brain was altered by the transition from oral-based societies to ones predominated by print. He proposed that the “closed-ness” and permanence of written and printed texts distanced “knower” from “known”, endowing human consciousness with the ability to reflect on itself and the world. This externalisation was not present in the age of “orality” – before print allowed the world to be pinned down into hierarchies and definitions, it was impossible to abstract knowledge, transmitted through speech, from its use in the immediate context. Print-based technologies enabled humanity to comprehend how we are always tied to a particular time and place, and thus gave us the ability to momentarily “step outside” that time and place in order to analyse it. Abstraction, therefore, is fundamentally tied to the written word.

If print facilitated our “drawing away” from the world by capturing otherwise-ephemeral, organic phenomena into static, organised prose, what changes to our cognitive processes have digital media – now our prevailing technology for communication – brought? Today we are doubly abstracted: after having lost the primacy of our aural faculties, we’re now growing apart from the tactility of print, too. And we’ve forgone with restrictive textual linearity: hypertext theorists writing in the 1990s, such as George Landow and Jay David Bolter, focused their attention on the networked, interactive and always-editable nature of the web, which ostensibly paves the way for a more democratised media landscape.

Almost three decades on, we can conjecture that this democratisation has (at least partly) been co-opted by a cunning neoliberalism: encouraged by the highly user-centric functionality of new media, we are seemingly less willing to engage with ideas we find unpalatable. Unlike a print text, which we have to slog through from start to finish, digital technologies allow us to click away on whim. We are also faced, more than ever, with manifold options for format, medium, bias and tenor, so much so that we can gravitate towards particular online outlets that tap into our existing values – stimulating our reward centres for confirmation bias – and find sanctuary in non-threatening echo chambers.

Returning to Ghost in the Shell, I do discern a significantly short-sighted aspect of the whitewashing debate, which is symptomatic of IdPol-based call-outs like it. Despite the scale of the uproar against Johansson’s casting and the movie’s depiction of cultural identities more generally, it’s worth noting that a substantial portion of the furore ensued in the West. Yet, as Japanese-American writer Emily Yoshida clarifies, the casting was not as controversial in the manga’s country of origin because race is understood differently and is embedded in completely distinct power dynamics there; the very notion of “whitewashing” was difficult to translate. Mamoru Oshii, who directed the 1995 Ghost in the Shell anime, even defended the decision to hire Johansson, and upon its release the Hollywood movie was generally well received by Japanese audiences.

Here, we see a plurality of viewpoints throwing into question what is a purportedly unified front. And, here, we are reminded of the troubles of speaking for others and assuming that we do, and can, know others’ wishes and motivations. To avoid vicious abstractionism, we must endeavour to see situations holistically, from various perspectives; only in doing so can we engage in transformative discourse. The film’s protagonist, Major Kusanagi, does get a non-human robot body; Kusanagi does have a Japanese name; anime characters are somewhat de-racialised; Johansson is a talented actor; whitewashing is a systemic problem in Hollywood. None of these statements are mutually exclusive. But, depending on which corner of the internet you choose to restrict yourself to, you may be led to believe – often as a result of well-meaning politicking – that they are.

***

Humility is key; we’re all still learning, and no-one is above criticism

Researchers Steven Sloman and Philip Fernbach have found that, while existing beliefs are hard to dislodge, convincing people they lack deep understanding of an issue does work in inspiring them to modify their views. Their suggestion for those of us fighting for change is to focus less on asserting our own beliefs and more on delving into the nuances and implications of those beliefs, and on engaging with those who have divergent opinions. We must be wary of our penchant for directing advocacy towards one another and patting ourselves on the back about “little wins”. Instead of resting on laurels, we need to reach out to those who don’t already agree with us, rather than shaming them and expecting this will catalyse changes in their ethical position.

As new media continue to take ascendancy in our lives and, in turn, modify our cognitive processes, it’s imperative that we fight the urge to disconnect from – to “block”, “unfollow”, “mute” – those whose perspectives we don’t agree with. I recognise that respectability politics – agitating for change in ways that don’t “ruffle too many feathers” – may seem defeatist; I agree that educating others is exhausting, and that self-preservatory safe spaces can be generative. But if we don’t take this task upon ourselves – and if those who don’t already share our views merely hold fast to their existing beliefs, because reason is a stubborn mental beast – then how do we rebuild our societies founded on oppression?

Taking our cues from William James, and accepting that all abstractions must be used in context, acknowledging their history and for a specific purpose, to what end are we truly deploying IdPol? Is it merely for self-congratulatory empowerment, or part of a larger emancipatory struggle?

Dennis Altman says that true liberation lies not in concessionary gestures within the prevailing society (he mentions, by way of example, contemporary pride marches), but rather in an overhaul of the system as a whole. Tania Canas advocates for a similar gambit: dispensing with appeals to diversity, which often just lead to tokenism, and aiming instead for initiatives that target equity from the get-go. But, as I see it, the most strategic way to achieve all of this is through chipping away at the larger system of oppression from within. If not respectability, then we can at least accommodate respect; if not education, then empathy.

Instead of seeking sanctuary from those who challenge us – presuming ill will on their part, casting them away as bearers of privilege-based sin – I entreat us all to seek middle ground and aim for deeper understanding, lest we alienate those who are already our allies and fail to “recruit” those who could be. And lest we ourselves stagnate because we have become ruled by our abstractions and duped into just toeing the party line, forever encased in our ideational bubbles.

Much like cognitive-behavioural therapy on a personal scale, actionable change on a societal level must begin with changes in perception and definition. Despite the separatism based on essentialist notions of identity that IdPol, in its extreme forms, seemingly takes as its starting point, political participation is inherently intersubjective. All knowledge – as feminist scholar Patricia Hill Collins has pointed out – is partial, both biased and incomplete; this means individual understanding is finite and fallible. We must therefore bolster it with others’ input and rely on one another’s cumulative expertise.

The dangers of proscription – of letting destructive ideas “fester and spread” – are more pressing than ever in this age of Trumpism, Hansonism, Islamophobia and the alt-right. Humility is key; we’re all still learning, and no-one is above criticism, no matter how few or many their “disadvantage points” are.

We must remember that privilege, like any other abstraction, is a concept we conceived of – a tool – for discussing a particular phenomenon. If we are going to be truly intersectional in our politics, truly accounting for the various matrices of fortune and disadvantage in our societies, then we need to go beyond resorting to identity labels as shorthand for authority, worth and cogency. Just like our language, our perspectives need to keep evolving to better serve the political ends we hope to achieve. And, if we’re going to worship at the IdPol altar, I’d rather we look our god in the face while we do.

Notes

This essay was assisted by Creative Victoria (Australia)

Artwork by Tia Kass

Edited by Roselina Press

Adolfo Aranjuez is the editor of Metro, Australia’s oldest film and media periodical.

#right now#idpol#lovethoughts#philosophy#adolfo aranjuez#creative victoria#australian literature#Youtube

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

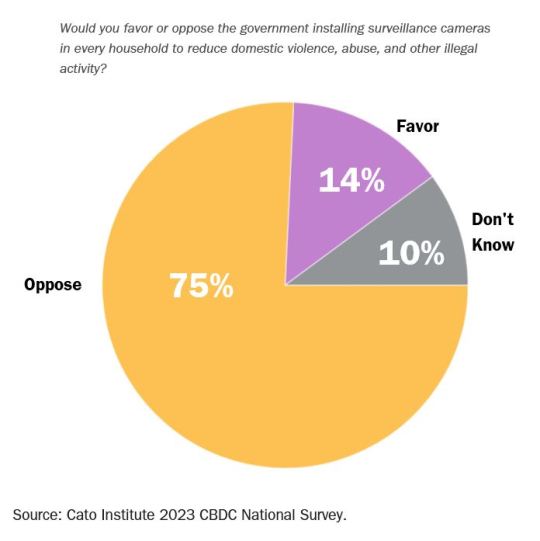

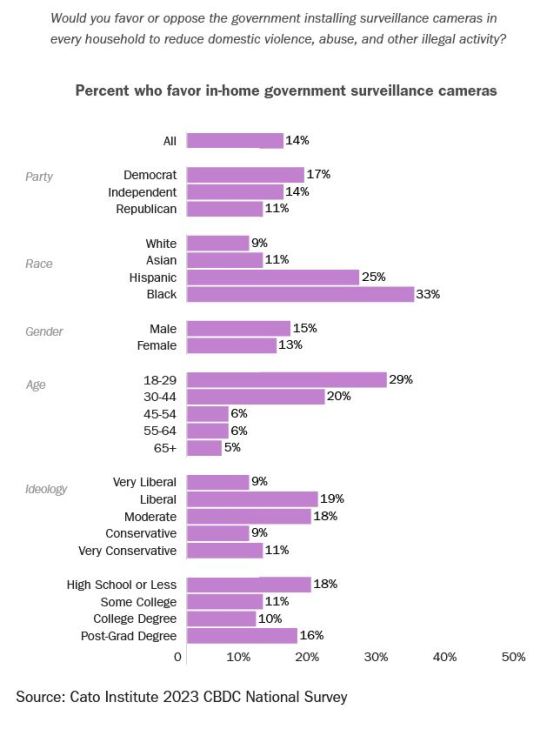

Nearly a Third of Gen Z Favors the Government Installing Surveillance Cameras in Homes

George Orwell’s 1984 is one of our society’s most frequently referenced illustrations of what life would be like under an authoritarian government. Actual government policies that are viewed as illiberal in varying degrees are often tied to this novel by opponents, an easy and effective way to call out government overreach and control. In the book 1984, citizens of the fictional nation Oceania are under constant government surveillance, including in their own homes. Devices called telescreens display propaganda and record peoples’ actions, allowing the government to monitor people even in what should be the most private place they know—their homes. This type of behavior is meant to be an extreme example of what can happen when a government gains too much power, and opposition to such surveillance has been assumed to be overwhelming and obvious. But is it?

In a newly released Cato Institute 2023 Central Bank Digital Currency National Survey of 2,000 Americans, we asked respondents whether they “favor or oppose the government installing surveillance cameras in every household to reduce domestic violence, abuse, and other illegal activity.” Not surprisingly, few Americans—only 14 percent—support this idea. Three‐fourths (75 percent) would oppose government surveillance cameras in homes, including 68 percent who “strongly oppose,” while 10% don’t have an opinion either way.

3 in 4 Americans oppose installing government surveillance cameras in all homes

However, Americans under the age of 30 stand out when it comes to 1984‐style in‐home government surveillance cameras. 3 in 10 (29 percent) Americans under 30 favor “the government installing surveillance cameras in every household” in order to “reduce domestic violence, abuse, and other illegal activity.” Support declines with age, dropping to 20 percent among 30–44 year olds and dropping considerably to 6 percent among those over the age of 45.

3 in 10 young Americans support government surveillance cameras in every household to reduce abuse and crime

We don’t know how much of this preference for security over privacy or freedom is something unique to this generation (a cohort effect) or simply the result of youth (age effect). However, there is reason to think part of this is generational. Americans over age 45 have vastly different attitudes on in‐home surveillance cameras than those who are younger. These Americans were born in or before 1978. Thus the very youngest were at least 11 before the Berlin Wall fell. Being raised during the Cold War amidst regular news reports of the Soviet Union surveilling their own people may have demonstrated to Americans the dangers of giving the government too much power to monitor people. Young people today are less exposed to these types of examples and thus less aware of the dangers of expansive government power.

It is also possible that increased support for government surveillance among the young has common roots with what Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt describe in the Coddling of the American Mind: young people seem more willing to prioritize safety (from possible violence or hurtful words) over ensuring robust freedom (from government surveillance or to speak freely).

Younger Americans, minorities, and the center-left are more open to in-home surveillance cameras

Other demographics also differ in their tolerance of government surveillance in their homes. African Americans (33 percent) and Hispanic Americans (25 percent) are more likely than White Americans (9 percent) and Asian Americans (11 percent) to support in‐home government surveillance. Democrats (17 percent) are also more likely than Republicans (11 percent) to support it but not by a wide margin. This issue divides Democrats between those who identify as “very liberal” in which only 9 percent support and “liberal” who are more than twice as likely to support (19 percent). Notably the issue doesn’t divide men (15 percent) and women (13 percent) who were about equally likely to support.

We asked this question as part of our survey on Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) in order to see whether there is a relationship between opinions on the government issuing a central bank digital currency and government installing cameras in homes. It appears that the two opinions are correlated. Interestingly, more than half (53 percent) of those who support the United States adopting a CBDC are also supportive of government surveillance cameras in homes, while only 2 percent of those who oppose a CBDC feel the same. This suggests there may be a common consideration that is prompted by both issues. Likely, it has to do with willingness to give up privacy in hopes of greater security.

More than half of those who support a CBDC also support in-home government surveillance cameras

It is important to emphasize that the overwhelming majority of Americans across demographic groups oppose the government surveilling people in their homes. Nevertheless, it is relevant to note the higher acceptance among younger generations to trade freedom and privacy for some added security and protection.

If these trends continue, the United States may confront a very different privacy landscape in the future. It is possible that at some point, the American public will be open to extreme government overreach in a world that feels scarier and more dangerous than before, whether or not it is. Thus, it is important to impart the learnings of the past (and present) about what can happen when government amasses too much power. Without explicitly telling younger generations about the risks and dangers of government surveillance they will forget these lessons and may find themselves repeating devastating mistakes of the past.

#article#government surveillance#surveilance#surveillance state#civil rights#gen z#fascism#authoritarianism

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

FIRE maintains databases, including:

Scholars Under Fire Database

Campus Disinvitation Database

#Greg Lukianoff#Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression#cancel culture#consequence culture#online mob#social media#mob mentality#offence culture#religion is a mental illness

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

If therapists are more concerned with helping you overcome your group privilege than helping you overcome your personal troubles, we've truly reached an abysmal place.

—Greg Lukianoff & Rikki Schlott, The Canceling of the American Mind: Cancel Culture Undermines Trust and Threatens Us All — But There Is a Solution

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

People I want to know better, thanks for the tag @gut-gemacht-mien-deern!

last song: Kiss by Prince

last show: Top Gun: Maverick - I saw it again last night in IMAX last week and honestly I can’t get over it but you probably know that already

currently watching: Obi Wan Kenobi - Not as good as I was expecting, but I am determined to finish it

currently reading: I've been 'reading' The Coddling of the American Mind by Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt for the last two months because I’m slow and haven’t had time to get back into it lately

no pressure on the tags but if you want to do it: @cazzyimagines @l0ura9 @green-like-the-sky @catfoundfics @nvtaliaromanovv @scuttle-buttle @hiraeth-the-dreamer @lorna-d-m

and anyone else who wants to!

#tag game#people i want to know better#some of you i already know pretty well tho#i tried to add a mix of people

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

On tribal mind and why fanwars happen for no real reason

There’s a famous series of experiments in social psychology called the minimal group paradigm, pioneered by Polish psychologist Henri Tajfel, who served in the French Army during World War II and became a prisoner of war in Germany. Profoundly affected by his experiences as a Jew during that period in Europe, including having his entire family in Poland murdered by the Nazis, Tajfel wanted to understand the conditions under which people would discriminate against members of an outgroup. So in the 1960s he conducted a series of experiments, each of which began by dividing people into two groups based on trivial and arbitrary criteria, such as flipping a coin. For example, in one study, each person first estimated the number of dots on a page. Irrespective of their estimations, half were told that they had overestimated the number of dots and were put into a group of “overestimators.” The other half were sent to the “underestimators” group. Next, subjects were asked to distribute points or money to all the other subjects, who were identified only by their group membership. Tajfel found that no matter how trivial or “minimal” he made the distinctions between the groups, people tended to distribute whatever was offered in favor of their in-group members.

Later studies have used a variety of techniques to reach the same conclusion. Neuroscientist David Eagleman used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to examine the brains of people who were watching videos of other people’s hands getting pricked by a needle or touched by a Q-tip. When the hand being pricked by a needle was labeled with the participant’s own religion, the area of the participant’s brain that handles pain showed a larger spike of activity than when the hand was labeled with a different religion. When arbitrary groups were created (such as by flipping a coin) immediately before the subject entered the MRI machine, and the hand being pricked was labeled as belonging to the same arbitrary group as the participant, even though the group hadn’t even existed just moments earlier, the participant’s brain still showed a larger spike. We just don’t feel as much empathy for those we see as “other.”

The bottom line is that the human mind is prepared for tribalism. Human evolution is not just the story of individuals competing with other individuals within each group; it’s also the story of groups competing with other groups—sometimes violently. We are all descended from people who belonged to groups that were consistently better at winning that competition. Tribalism is our evolutionary endowment for banding together to prepare for intergroup conflict. When the “tribes switch” is activated, we bind ourselves more tightly to the group, we embrace and defend the group’s moral matrix, and we stop thinking for ourselves. A basic principle of moral psychology is that “morality binds and blinds,” which is a useful trick for a group gearing up for a battle between “us” and “them.” In tribal mode, we seem to go blind to arguments and information that challenge our team’s narrative. Merging with the group in this way is deeply pleasurable—as you can see from the pseudotribal antics that accompany college football games.

(From "The Coddling of the American mind" by Greg Lukianoff)

Bold by me.

"Moral matrix" and "team's narrative" are easily observable in kfandoms. Some untruth (our bias is mistreated) or story (this member is the reason out bias is mistreated; all 127zens are bigots and care not for DJJ) gains support by those who can't resist the tribal pull, who find the satisfaction in "merging with the group".

I also want to point out that the experiments demonstrated how easy it is to divide people into "us" vs "them". Even just a name, a label is enough. Today ifans of WayV were super offended that the albums of other NCT units will be sold at WayV's fanmeets in Japan. As if it's not the same big group and it's not more comfortable for fans who like and support several units (and they exist) to be able to buy all albums they want at once.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

— The Canceling of the American Mind by Greg Lukianoff and Rikki Scholott

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Greg Lukianoff on Martin Gurri's "The Revolt of the Public"

One thing must be said about the “crisis of authority” we find ourselves in due to the overwhelming power of negation: Very often, what critics have discovered is that our existing “knowledge” was based on some pretty thin evidence, bad assumptions, and sometimes not much more than the pieties of some elites. Understanding the crisis of authority as only being wrongfully destructive of expertise is to miss the fact that, frankly, we are often asking far too much of expertise and experts — and oversight itself has not been all that rigorous.

Negation is indeed tearing things down that really needed to be torn down. The problem is that it seems to be taking everything else with it.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

University Protests and Free Speech - Greg Lukianoff

A common thread that runs through many of the issue around free speech and the freedom of expression in our Canadian society is the application of the rules and making sure they apply to everyone in the same manner. If our institutions could stand up and once again treat equality before the law as a meaningful statement it would solve many of the problems we’ve been having. The long shadow of…

View On WordPress

0 notes