#Greek mercenaries in Persian service

Note

Hello Dr. Reames!

Like many of us who follow you on this Hell-site we call home, I started watching Netflix's Alexander: The Making of a God. I'm an awfully shy person, and have been meaning to say hello, but a deadly concoction of anxiety and imposter syndrome has kept me away until a part of the docuseries lit a burning fire of a question.

I'm an Early Modern historian (18th century France), and although I have an obsession with Alexander the Great (going as far as begging my parents from around age 10 to 18 to legally change my name to Alexander) I never took a deep academic dive into the ancient Mediterranean world.

I think it was episode 2 where Alexander and Darius finally face each other at Issus, and after the battle Alexander has the captured "Greeks" (I can't remember now if he said Greeks or Macedonians) from Darius' army killed for fighting on the "wrong side." This kind of rubbed me the wrong way, especially when they switch to the talking heads and they kind of touch on it being known that people from the Greek poleis were mercenaries and were throughout the known Mediterranean world. That scene had a sort of 'Alexander as a Macedonian Nationalist' feel, and I assumed that Alexander was more open to the blending of cultures or at least there wasn't a single correct way to live and rule. That whole sequence of scenes felt contradictory: the mercenary system is well known yet a betrayal against "blood brothers"? Would Alexander actually have mercenaries executed for being hired by Persia?

Thank you for your time!

I'm glad you decided to finally step forward and ask a question! Nice to "meet" you.

Ah, yes, this is a matter of Real Politik.

After Granikos, a number of Greek mercenaries were captured, although their commander, Memnon, got away himself as he’d have been on horseback. Alexander had the men executed.

Greeks had served as mercenaries in Asia as far back as the Assyrian Sargonids. In fact, arguably, the archaic full hoplite panoply developed to fight on the broad plains of the middle east, not in Greece. (See John Hale’s chapter “Not Patriots, Not Farmers, Not Amateurs” in Men of Bronze, Kagan and Viggiano, eds., from Princeton; I find his argument convincing.) And, of course, Xenophon’s famous Anabasis told about the flight west of Greek mercenaries who’d served under Cyrus the Younger in his disastrous clash with his brother Artaxerxes for the throne.

For Alexander, the problem was that he—or really his father—had positioned this campaign as retribution against Persia for Persia’s earlier invasion of Greece, especially that under Xerxes. The invasion was, officially, under the aegis of the Corinthian League, with the Macedonian king just the hegemon. That made it a “Greek” campaign. This was all propaganda of course, but important for Philip, then Alexander, to maintain as it gave a patina of acceptability, not a naked power grab for more territory. While conquest wasn’t looked on then nearly as badly as it is now, it helped to have at least a plausible excuse.

His own troops included a number of Greek allies. After Chaironeia, they didn’t really have a choice. But a lot of Greeks were not happy to be in the Corinthian League. Sparta outright refused and would later be the center of an anti-Macedonian revolt.

At Granikos, the Persians had more Greek mercenaries than Alexander had Greek allies! (If one doesn’t count the Thessalian horse.) The optics were really bad. Ergo, as I think it was Carolyn who pointed out, Alexander had to send a clear message that fighting for the Persians against “the Greeks” wasn’t an option. In the Greek mind, mercenaries had always occupied a liminal status: not fully trusted because they fought for pay, but typically better than citizen troops, so used extensively post-Peloponnesian War. It was easy for Alexander to cast them as “just in it for the money” and as traitors to the Greek Cause. Like Thebes in the earlier Greco-Persian Wars, they’d “Medized,” which had a similar force to calling an American a “commie” in the 1950s.

The executions weren’t well-received in the rest of Greece, and resistance continued until it came to a head a couple years later with Agis’s Revolt (Agis III was the Spartan king who led it.). But Alexander was never afraid to send a harsh message when he needed to: Thebes, Tyre, Persepolis…. Philip did too. He could be just as brutal (Potidaia, Amphipolis, Stagiera), and Alexander learned well from him how to use carrot and stick.

So that’s what was going on there. Alexander was trying to turn Darius’ Greek mercenaries (who were some of the best troops in Asia Minor), and to send a message back HOME not to unite behind him and cut his supply lines. This was not successful; in fact, if Curtius can be believed, the Greek mercenaries were more loyal to Darius after Gaugamela than Bessus and friends. They figured they couldn’t go over to ATG, so they stuck with Darius who’d treated them well. Ironically, these same guys later did surrender after Darius’ death and were pardoned because, by then, showing clemency worked better for him than punishment.

Due to time constraints, and the desire of the showrunner to focus on Alexander and Darius, a lot of the details behind the campaign weren’t explored. So to the average reader, it looks like it was just Macedonians deciding to invade Persia because Persia killed Philip, although Philip says before he’s murdered that he wanted Alexander back for the Persian expedition. Not sure the casual viewer caught that. But this isn’t entirely wrong, as it really WAS a Macedonian campaign covered in the sheep’s skin of “Greek revenge.” Nothing is shown of ATG’s Greek campaigns, not even the infamous siege of Thebes because, again, the creators wanted it to be a clash of Macedon and Persia.

Alexander’s career is just so sprawling it’s really impossible to cover everything in limited time. But I hope that helps to contextualize why the Greek mercenaries were killed, and why it was presented as being traitors to the cause.

#asks#Alexander the Great#Alexander: the Making of a God#Greek mercenaries in Persian service#Memnon#The Corinthian League#Philip's campaign of “revenge” against Persia#Alexander's campaign of “revenge” against Persia#ancient Persia#classics#ancient macedonia

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Sculpture Gallery in Rome at the Time of Agrippa by Lawrence Alma-Tadema + Memnon of Rhodes by Dalton Thomas Rix + Coinage of Memnon of Rhodes, Mysia. Mid 4th century BC

Memnon's career in Persian service had a strange start. In fact, the Persians needed his brother Mentor to defend the Troad (the northwest of modern Turkey), and gave him land in that region. Not much later, Mentor was made Persian supreme commander in the West and married Barsine, the daughter of the satrap of Hellespontine Phrygia, Artabazus, who married a sister of the Rhodians.

Memnon joined his brother and shared in his adventures. For example, when Artabazus rebelled against king Artaxerxes III Ochus in 353 or 352, they assisted him. The revolt was not successful, and Artabazus and Memnon were forced to flee to Pella, the capital of Macedonia. Here, they met king Philip, the young crown prince and the philosopher Aristotle of Stagira.

...

The Persians dug themselves in on the banks of the river Granicus, the modern Biga Çay. If Alexander moved to the south, where he wanted to liberate Greek towns like Ephesus and Miletus, they could attack his rear; if he moved to the east to drive them out, their position was strong enough to withstand the attack of a larger army. However, the Persians were defeated (June 334).

Darius, however, understood that Memnon had been right about his strategy. He ordered the Persian navy to move to the Aegean sea; it had to come from Egypt, Phoenicia, and Cyprus, and it arrived three days too late to prevent the capture of Miletus. However, Memnon, now appointed supreme commander, managed to keep the Persian naval base Halicarnassus (modern Bodrum) for a long time and was able to evacuate the town without unacceptable losses. In fact, Halicarnassus was the last Persian victory: after the siege, Alexander needed reinforcements, and it gave the Persians the opportunity to regroup.

—Memnon of Rhodes at Livius.org

Memnon, one of King Darius’s generals against Alexander, when a mercenary soldier excessively and impudently reviled Alexander, struck him with his spear, adding, I pay you to fight against Alexander, not to reproach him.

—Plutarch, Morals vol. 1

#Memnon of Rhodes#Dalton Thomas Rix#Lawrence Alma-Tadema#King Philip II of Macedon#Darius III#Aristotle#Laocoön#Alexander the Great#Plato

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

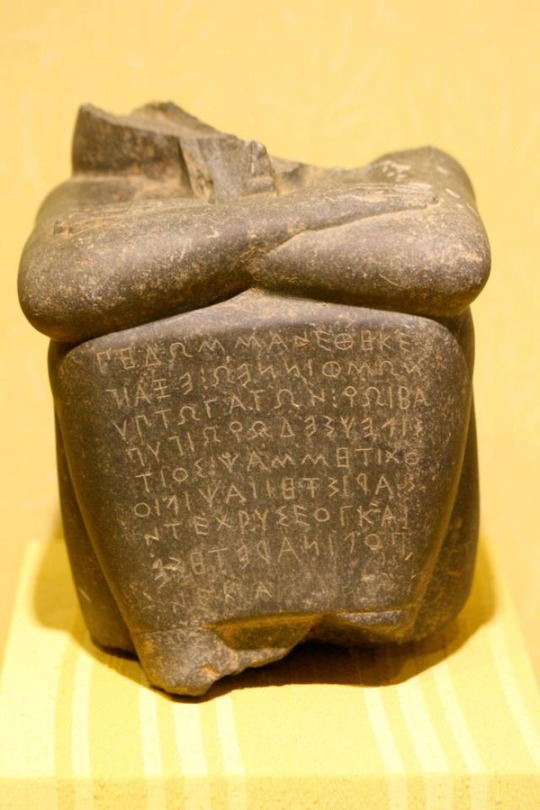

Pedon’s Egyptian-Greek Votive Dedication

The bustrophedic inscription (in Ionian Greek) reads:

Pedon dedicated me, the son of Amphinneos [or Amphinnes], having brought me from Egypt; to him the Egyptian king—Psammetichus—gave as a reward of valor a golden bracelet and a city, on account of his virtue.

According to the abstract of the article of Nicolo Barbaro “Pedon the Mercenary’s Votive Dedication” (https://edizionicafoscari.unive.it/riviste/axon/2018/1/dedica-votiva-del-mercenario-pedon/ ):

In the Ionian city of Priene, in the first half of the 6th century BC, Pedon, son of Amphinneos, Greek mercenary at the service of the pharaohs of the 26th dynasty, dedicated an Egyptian block statue. It is not known if this statue was placed in a specific sanctuary, as it was found, in the late ’80s, in a cave near the same Priene. This block statue, headless and without feet and the base, according to some stylistic peculiarities, can be dated to the reign of Psammetichus I (664-610 BC), who hired Greek and Carian men, as mercenaries, to join and make his own kingdom stable. The inscription, which is on the front of the statue, is bustrophedic and consists of nine lines containing the typical formula of dedication and autobiographical references, as was typical in the use of this kind of sculpture by the Egyptians; on the last part of the inscription, Pedon mentions the pharaoh under whom he served as a mercenary, Psammetichus (Ψαμμήτιχος), and the particular gifts given to him by the pharaoh, a gold bracelet (ψίλιον τε χρύσεογ) and a city (πόλιν), attributable to some peculiarities of both Egyptian and Persian royal culture. A comparison of the paleographic characters dates instead this inscription to the reign of Psammetichus II (595-589 BC), fourth ruler of this dynasty, who also made great use of Greek mercenaries in his army, especially during an expedition in Nubia, which is known from the historical work of Herodotus and from the graffiti left by these Greeks to Abu Simbel. About the identity of the pharaoh mentioned in the inscription and the consequent dating of the same, numerous studies have been spent that have supported one or the other pharaoh, up to a final hypothesis that puts both theories in agreement: the mercenary Pedon would have served Psammetichus I and, after buying this block statue, would have returned to Ionia, where he would have engraved the inscription and where centuries later the statue was found.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

From Justinian to Isaac Comnenus

The fact is that, for the five centuries from Justinian to Isaac Comnenus, the attacks on the empire, from the European side, at any rate, were the attacks of nomad, unorganised, and uncivilised races on a civilised and highly- organised empire. And in spite of anarchy, corruption, and effeminacy at the Byzantine court, civilisation and wealth told in every contest. Greek fire, military science, enormous resources, and the prestige of empire always bore down wild valour and predatory enthusiasm. Just as Russia dominates the Turkoman tribes of Central Asia, as Turkey holds back the valiant Arabs of her eastern frontier, as Egyptian natives with British officers easily master the heroic Ghazis of the Soudan — so the Roman Empire on the Bosphorus beat back Huns, Avars, Persians, Slaves, Bulgarians, Patzinaks, and Russians. We need only to study the history of Russia and of Turkey to learn how the organising ability, the resources, and material arts of great empires outweigh folly, vice, and corruption in the palace.

4. Of course a succession of victorious campaigns implies a succession of valiant armies; and there is nothing on which we need more light than on the exact organisation and national constituents of those Roman armies which crushed Chosroes, Muaviah, Crumn, Samuel, and Hamdanids. They are called conventionally ‘Greeks’; but during the Heraclian, Isaurian ephesus daily tour, and Basilian dynasties there seem to have been no Greeks at all in the land forces. The armies were always composed of a strange collection of races, with different languages, arms, methods of fighting, and types of civilisation. They were often magnificent and courageous barbarians, conspicuous amongst whom were Scandinavians and English, and with them some of the most warlike braves of Asia and of Europe.

National characteristics

The empire made no attempt to destroy their national characteristics, to discourage their native language, religion, or habits. Each force was told off to the service which suited it best, and was trained in the use of its proper weapons. They remained distinct from each other, and wholly distinct from the civil population. But as they could not unite, they seldom became so great a danger to the empire as the Praetorian guard of the Roman army. The organisation and management of such a heterogeneous body of mercenary braves required extraordinary skill; but it was just this skill which the rulers of Byzantium possessed. The bond of the whole was the tradition of discipline and the consciousness of serving the Roman Emperor.

The modern history of Russia and still more the native armies of the British Empire will enable us to understand how the work ©f consolidation was effected. The Queen’s dominions are at this hour defended by men of almost every race, colour, language, religion, costume, and habits. And we may imagine the composite character of the Byzantine armies, if we reflect how distant wars are carried on in the name of Victoria by Hindoos, Musulmans, Pa- thans, Ghoorkas, Afghans, Egyptians, Soudanese, Zanzibaris, Negroes, Nubians, Zulus, Kaffirs, and West Indians, using their native languages, retaining their national habits, and, to a great extent, their native costume.

The Roman Empire was maintained from its centre on the Bosphorus, somewhat as the British Empire is maintained from its centre on the Thames, by wealth, maritime ascendency, the traditions of empire, and organising capacity — always with the great difference that there was no purely Roman nucleus as there is a purely British nucleus, and also that the soldiery of the Roman Empire had no common armament, and was not officered by men of the dominant race, but by capable leaders indifferently picked from any race, except the Latin or the Greek. Dominant race there was none; nation there was none. Roman meant subject of the Emperor; Emperor meant the chief in the vermilion buskins, installed in the Palace on the Bosphorus, and duly crowned by the Orthodox Patriarch in the Church of the Holy Wisdom.

0 notes

Photo

From Justinian to Isaac Comnenus

The fact is that, for the five centuries from Justinian to Isaac Comnenus, the attacks on the empire, from the European side, at any rate, were the attacks of nomad, unorganised, and uncivilised races on a civilised and highly- organised empire. And in spite of anarchy, corruption, and effeminacy at the Byzantine court, civilisation and wealth told in every contest. Greek fire, military science, enormous resources, and the prestige of empire always bore down wild valour and predatory enthusiasm. Just as Russia dominates the Turkoman tribes of Central Asia, as Turkey holds back the valiant Arabs of her eastern frontier, as Egyptian natives with British officers easily master the heroic Ghazis of the Soudan — so the Roman Empire on the Bosphorus beat back Huns, Avars, Persians, Slaves, Bulgarians, Patzinaks, and Russians. We need only to study the history of Russia and of Turkey to learn how the organising ability, the resources, and material arts of great empires outweigh folly, vice, and corruption in the palace.

4. Of course a succession of victorious campaigns implies a succession of valiant armies; and there is nothing on which we need more light than on the exact organisation and national constituents of those Roman armies which crushed Chosroes, Muaviah, Crumn, Samuel, and Hamdanids. They are called conventionally ‘Greeks’; but during the Heraclian, Isaurian ephesus daily tour, and Basilian dynasties there seem to have been no Greeks at all in the land forces. The armies were always composed of a strange collection of races, with different languages, arms, methods of fighting, and types of civilisation. They were often magnificent and courageous barbarians, conspicuous amongst whom were Scandinavians and English, and with them some of the most warlike braves of Asia and of Europe.

National characteristics

The empire made no attempt to destroy their national characteristics, to discourage their native language, religion, or habits. Each force was told off to the service which suited it best, and was trained in the use of its proper weapons. They remained distinct from each other, and wholly distinct from the civil population. But as they could not unite, they seldom became so great a danger to the empire as the Praetorian guard of the Roman army. The organisation and management of such a heterogeneous body of mercenary braves required extraordinary skill; but it was just this skill which the rulers of Byzantium possessed. The bond of the whole was the tradition of discipline and the consciousness of serving the Roman Emperor.

The modern history of Russia and still more the native armies of the British Empire will enable us to understand how the work ©f consolidation was effected. The Queen’s dominions are at this hour defended by men of almost every race, colour, language, religion, costume, and habits. And we may imagine the composite character of the Byzantine armies, if we reflect how distant wars are carried on in the name of Victoria by Hindoos, Musulmans, Pa- thans, Ghoorkas, Afghans, Egyptians, Soudanese, Zanzibaris, Negroes, Nubians, Zulus, Kaffirs, and West Indians, using their native languages, retaining their national habits, and, to a great extent, their native costume.

The Roman Empire was maintained from its centre on the Bosphorus, somewhat as the British Empire is maintained from its centre on the Thames, by wealth, maritime ascendency, the traditions of empire, and organising capacity — always with the great difference that there was no purely Roman nucleus as there is a purely British nucleus, and also that the soldiery of the Roman Empire had no common armament, and was not officered by men of the dominant race, but by capable leaders indifferently picked from any race, except the Latin or the Greek. Dominant race there was none; nation there was none. Roman meant subject of the Emperor; Emperor meant the chief in the vermilion buskins, installed in the Palace on the Bosphorus, and duly crowned by the Orthodox Patriarch in the Church of the Holy Wisdom.

0 notes

Photo

From Justinian to Isaac Comnenus

The fact is that, for the five centuries from Justinian to Isaac Comnenus, the attacks on the empire, from the European side, at any rate, were the attacks of nomad, unorganised, and uncivilised races on a civilised and highly- organised empire. And in spite of anarchy, corruption, and effeminacy at the Byzantine court, civilisation and wealth told in every contest. Greek fire, military science, enormous resources, and the prestige of empire always bore down wild valour and predatory enthusiasm. Just as Russia dominates the Turkoman tribes of Central Asia, as Turkey holds back the valiant Arabs of her eastern frontier, as Egyptian natives with British officers easily master the heroic Ghazis of the Soudan — so the Roman Empire on the Bosphorus beat back Huns, Avars, Persians, Slaves, Bulgarians, Patzinaks, and Russians. We need only to study the history of Russia and of Turkey to learn how the organising ability, the resources, and material arts of great empires outweigh folly, vice, and corruption in the palace.

4. Of course a succession of victorious campaigns implies a succession of valiant armies; and there is nothing on which we need more light than on the exact organisation and national constituents of those Roman armies which crushed Chosroes, Muaviah, Crumn, Samuel, and Hamdanids. They are called conventionally ‘Greeks’; but during the Heraclian, Isaurian ephesus daily tour, and Basilian dynasties there seem to have been no Greeks at all in the land forces. The armies were always composed of a strange collection of races, with different languages, arms, methods of fighting, and types of civilisation. They were often magnificent and courageous barbarians, conspicuous amongst whom were Scandinavians and English, and with them some of the most warlike braves of Asia and of Europe.

National characteristics

The empire made no attempt to destroy their national characteristics, to discourage their native language, religion, or habits. Each force was told off to the service which suited it best, and was trained in the use of its proper weapons. They remained distinct from each other, and wholly distinct from the civil population. But as they could not unite, they seldom became so great a danger to the empire as the Praetorian guard of the Roman army. The organisation and management of such a heterogeneous body of mercenary braves required extraordinary skill; but it was just this skill which the rulers of Byzantium possessed. The bond of the whole was the tradition of discipline and the consciousness of serving the Roman Emperor.

The modern history of Russia and still more the native armies of the British Empire will enable us to understand how the work ©f consolidation was effected. The Queen’s dominions are at this hour defended by men of almost every race, colour, language, religion, costume, and habits. And we may imagine the composite character of the Byzantine armies, if we reflect how distant wars are carried on in the name of Victoria by Hindoos, Musulmans, Pa- thans, Ghoorkas, Afghans, Egyptians, Soudanese, Zanzibaris, Negroes, Nubians, Zulus, Kaffirs, and West Indians, using their native languages, retaining their national habits, and, to a great extent, their native costume.

The Roman Empire was maintained from its centre on the Bosphorus, somewhat as the British Empire is maintained from its centre on the Thames, by wealth, maritime ascendency, the traditions of empire, and organising capacity — always with the great difference that there was no purely Roman nucleus as there is a purely British nucleus, and also that the soldiery of the Roman Empire had no common armament, and was not officered by men of the dominant race, but by capable leaders indifferently picked from any race, except the Latin or the Greek. Dominant race there was none; nation there was none. Roman meant subject of the Emperor; Emperor meant the chief in the vermilion buskins, installed in the Palace on the Bosphorus, and duly crowned by the Orthodox Patriarch in the Church of the Holy Wisdom.

0 notes

Photo

From Justinian to Isaac Comnenus

The fact is that, for the five centuries from Justinian to Isaac Comnenus, the attacks on the empire, from the European side, at any rate, were the attacks of nomad, unorganised, and uncivilised races on a civilised and highly- organised empire. And in spite of anarchy, corruption, and effeminacy at the Byzantine court, civilisation and wealth told in every contest. Greek fire, military science, enormous resources, and the prestige of empire always bore down wild valour and predatory enthusiasm. Just as Russia dominates the Turkoman tribes of Central Asia, as Turkey holds back the valiant Arabs of her eastern frontier, as Egyptian natives with British officers easily master the heroic Ghazis of the Soudan — so the Roman Empire on the Bosphorus beat back Huns, Avars, Persians, Slaves, Bulgarians, Patzinaks, and Russians. We need only to study the history of Russia and of Turkey to learn how the organising ability, the resources, and material arts of great empires outweigh folly, vice, and corruption in the palace.

4. Of course a succession of victorious campaigns implies a succession of valiant armies; and there is nothing on which we need more light than on the exact organisation and national constituents of those Roman armies which crushed Chosroes, Muaviah, Crumn, Samuel, and Hamdanids. They are called conventionally ‘Greeks’; but during the Heraclian, Isaurian ephesus daily tour, and Basilian dynasties there seem to have been no Greeks at all in the land forces. The armies were always composed of a strange collection of races, with different languages, arms, methods of fighting, and types of civilisation. They were often magnificent and courageous barbarians, conspicuous amongst whom were Scandinavians and English, and with them some of the most warlike braves of Asia and of Europe.

National characteristics

The empire made no attempt to destroy their national characteristics, to discourage their native language, religion, or habits. Each force was told off to the service which suited it best, and was trained in the use of its proper weapons. They remained distinct from each other, and wholly distinct from the civil population. But as they could not unite, they seldom became so great a danger to the empire as the Praetorian guard of the Roman army. The organisation and management of such a heterogeneous body of mercenary braves required extraordinary skill; but it was just this skill which the rulers of Byzantium possessed. The bond of the whole was the tradition of discipline and the consciousness of serving the Roman Emperor.

The modern history of Russia and still more the native armies of the British Empire will enable us to understand how the work ©f consolidation was effected. The Queen’s dominions are at this hour defended by men of almost every race, colour, language, religion, costume, and habits. And we may imagine the composite character of the Byzantine armies, if we reflect how distant wars are carried on in the name of Victoria by Hindoos, Musulmans, Pa- thans, Ghoorkas, Afghans, Egyptians, Soudanese, Zanzibaris, Negroes, Nubians, Zulus, Kaffirs, and West Indians, using their native languages, retaining their national habits, and, to a great extent, their native costume.

The Roman Empire was maintained from its centre on the Bosphorus, somewhat as the British Empire is maintained from its centre on the Thames, by wealth, maritime ascendency, the traditions of empire, and organising capacity — always with the great difference that there was no purely Roman nucleus as there is a purely British nucleus, and also that the soldiery of the Roman Empire had no common armament, and was not officered by men of the dominant race, but by capable leaders indifferently picked from any race, except the Latin or the Greek. Dominant race there was none; nation there was none. Roman meant subject of the Emperor; Emperor meant the chief in the vermilion buskins, installed in the Palace on the Bosphorus, and duly crowned by the Orthodox Patriarch in the Church of the Holy Wisdom.

0 notes

Photo

From Justinian to Isaac Comnenus

The fact is that, for the five centuries from Justinian to Isaac Comnenus, the attacks on the empire, from the European side, at any rate, were the attacks of nomad, unorganised, and uncivilised races on a civilised and highly- organised empire. And in spite of anarchy, corruption, and effeminacy at the Byzantine court, civilisation and wealth told in every contest. Greek fire, military science, enormous resources, and the prestige of empire always bore down wild valour and predatory enthusiasm. Just as Russia dominates the Turkoman tribes of Central Asia, as Turkey holds back the valiant Arabs of her eastern frontier, as Egyptian natives with British officers easily master the heroic Ghazis of the Soudan — so the Roman Empire on the Bosphorus beat back Huns, Avars, Persians, Slaves, Bulgarians, Patzinaks, and Russians. We need only to study the history of Russia and of Turkey to learn how the organising ability, the resources, and material arts of great empires outweigh folly, vice, and corruption in the palace.

4. Of course a succession of victorious campaigns implies a succession of valiant armies; and there is nothing on which we need more light than on the exact organisation and national constituents of those Roman armies which crushed Chosroes, Muaviah, Crumn, Samuel, and Hamdanids. They are called conventionally ‘Greeks’; but during the Heraclian, Isaurian ephesus daily tour, and Basilian dynasties there seem to have been no Greeks at all in the land forces. The armies were always composed of a strange collection of races, with different languages, arms, methods of fighting, and types of civilisation. They were often magnificent and courageous barbarians, conspicuous amongst whom were Scandinavians and English, and with them some of the most warlike braves of Asia and of Europe.

National characteristics

The empire made no attempt to destroy their national characteristics, to discourage their native language, religion, or habits. Each force was told off to the service which suited it best, and was trained in the use of its proper weapons. They remained distinct from each other, and wholly distinct from the civil population. But as they could not unite, they seldom became so great a danger to the empire as the Praetorian guard of the Roman army. The organisation and management of such a heterogeneous body of mercenary braves required extraordinary skill; but it was just this skill which the rulers of Byzantium possessed. The bond of the whole was the tradition of discipline and the consciousness of serving the Roman Emperor.

The modern history of Russia and still more the native armies of the British Empire will enable us to understand how the work ©f consolidation was effected. The Queen’s dominions are at this hour defended by men of almost every race, colour, language, religion, costume, and habits. And we may imagine the composite character of the Byzantine armies, if we reflect how distant wars are carried on in the name of Victoria by Hindoos, Musulmans, Pa- thans, Ghoorkas, Afghans, Egyptians, Soudanese, Zanzibaris, Negroes, Nubians, Zulus, Kaffirs, and West Indians, using their native languages, retaining their national habits, and, to a great extent, their native costume.

The Roman Empire was maintained from its centre on the Bosphorus, somewhat as the British Empire is maintained from its centre on the Thames, by wealth, maritime ascendency, the traditions of empire, and organising capacity — always with the great difference that there was no purely Roman nucleus as there is a purely British nucleus, and also that the soldiery of the Roman Empire had no common armament, and was not officered by men of the dominant race, but by capable leaders indifferently picked from any race, except the Latin or the Greek. Dominant race there was none; nation there was none. Roman meant subject of the Emperor; Emperor meant the chief in the vermilion buskins, installed in the Palace on the Bosphorus, and duly crowned by the Orthodox Patriarch in the Church of the Holy Wisdom.

0 notes

Photo

From Justinian to Isaac Comnenus

The fact is that, for the five centuries from Justinian to Isaac Comnenus, the attacks on the empire, from the European side, at any rate, were the attacks of nomad, unorganised, and uncivilised races on a civilised and highly- organised empire. And in spite of anarchy, corruption, and effeminacy at the Byzantine court, civilisation and wealth told in every contest. Greek fire, military science, enormous resources, and the prestige of empire always bore down wild valour and predatory enthusiasm. Just as Russia dominates the Turkoman tribes of Central Asia, as Turkey holds back the valiant Arabs of her eastern frontier, as Egyptian natives with British officers easily master the heroic Ghazis of the Soudan — so the Roman Empire on the Bosphorus beat back Huns, Avars, Persians, Slaves, Bulgarians, Patzinaks, and Russians. We need only to study the history of Russia and of Turkey to learn how the organising ability, the resources, and material arts of great empires outweigh folly, vice, and corruption in the palace.

4. Of course a succession of victorious campaigns implies a succession of valiant armies; and there is nothing on which we need more light than on the exact organisation and national constituents of those Roman armies which crushed Chosroes, Muaviah, Crumn, Samuel, and Hamdanids. They are called conventionally ‘Greeks’; but during the Heraclian, Isaurian ephesus daily tour, and Basilian dynasties there seem to have been no Greeks at all in the land forces. The armies were always composed of a strange collection of races, with different languages, arms, methods of fighting, and types of civilisation. They were often magnificent and courageous barbarians, conspicuous amongst whom were Scandinavians and English, and with them some of the most warlike braves of Asia and of Europe.

National characteristics

The empire made no attempt to destroy their national characteristics, to discourage their native language, religion, or habits. Each force was told off to the service which suited it best, and was trained in the use of its proper weapons. They remained distinct from each other, and wholly distinct from the civil population. But as they could not unite, they seldom became so great a danger to the empire as the Praetorian guard of the Roman army. The organisation and management of such a heterogeneous body of mercenary braves required extraordinary skill; but it was just this skill which the rulers of Byzantium possessed. The bond of the whole was the tradition of discipline and the consciousness of serving the Roman Emperor.

The modern history of Russia and still more the native armies of the British Empire will enable us to understand how the work ©f consolidation was effected. The Queen’s dominions are at this hour defended by men of almost every race, colour, language, religion, costume, and habits. And we may imagine the composite character of the Byzantine armies, if we reflect how distant wars are carried on in the name of Victoria by Hindoos, Musulmans, Pa- thans, Ghoorkas, Afghans, Egyptians, Soudanese, Zanzibaris, Negroes, Nubians, Zulus, Kaffirs, and West Indians, using their native languages, retaining their national habits, and, to a great extent, their native costume.

The Roman Empire was maintained from its centre on the Bosphorus, somewhat as the British Empire is maintained from its centre on the Thames, by wealth, maritime ascendency, the traditions of empire, and organising capacity — always with the great difference that there was no purely Roman nucleus as there is a purely British nucleus, and also that the soldiery of the Roman Empire had no common armament, and was not officered by men of the dominant race, but by capable leaders indifferently picked from any race, except the Latin or the Greek. Dominant race there was none; nation there was none. Roman meant subject of the Emperor; Emperor meant the chief in the vermilion buskins, installed in the Palace on the Bosphorus, and duly crowned by the Orthodox Patriarch in the Church of the Holy Wisdom.

0 notes

Photo

From Justinian to Isaac Comnenus

The fact is that, for the five centuries from Justinian to Isaac Comnenus, the attacks on the empire, from the European side, at any rate, were the attacks of nomad, unorganised, and uncivilised races on a civilised and highly- organised empire. And in spite of anarchy, corruption, and effeminacy at the Byzantine court, civilisation and wealth told in every contest. Greek fire, military science, enormous resources, and the prestige of empire always bore down wild valour and predatory enthusiasm. Just as Russia dominates the Turkoman tribes of Central Asia, as Turkey holds back the valiant Arabs of her eastern frontier, as Egyptian natives with British officers easily master the heroic Ghazis of the Soudan — so the Roman Empire on the Bosphorus beat back Huns, Avars, Persians, Slaves, Bulgarians, Patzinaks, and Russians. We need only to study the history of Russia and of Turkey to learn how the organising ability, the resources, and material arts of great empires outweigh folly, vice, and corruption in the palace.

4. Of course a succession of victorious campaigns implies a succession of valiant armies; and there is nothing on which we need more light than on the exact organisation and national constituents of those Roman armies which crushed Chosroes, Muaviah, Crumn, Samuel, and Hamdanids. They are called conventionally ‘Greeks’; but during the Heraclian, Isaurian ephesus daily tour, and Basilian dynasties there seem to have been no Greeks at all in the land forces. The armies were always composed of a strange collection of races, with different languages, arms, methods of fighting, and types of civilisation. They were often magnificent and courageous barbarians, conspicuous amongst whom were Scandinavians and English, and with them some of the most warlike braves of Asia and of Europe.

National characteristics

The empire made no attempt to destroy their national characteristics, to discourage their native language, religion, or habits. Each force was told off to the service which suited it best, and was trained in the use of its proper weapons. They remained distinct from each other, and wholly distinct from the civil population. But as they could not unite, they seldom became so great a danger to the empire as the Praetorian guard of the Roman army. The organisation and management of such a heterogeneous body of mercenary braves required extraordinary skill; but it was just this skill which the rulers of Byzantium possessed. The bond of the whole was the tradition of discipline and the consciousness of serving the Roman Emperor.

The modern history of Russia and still more the native armies of the British Empire will enable us to understand how the work ©f consolidation was effected. The Queen’s dominions are at this hour defended by men of almost every race, colour, language, religion, costume, and habits. And we may imagine the composite character of the Byzantine armies, if we reflect how distant wars are carried on in the name of Victoria by Hindoos, Musulmans, Pa- thans, Ghoorkas, Afghans, Egyptians, Soudanese, Zanzibaris, Negroes, Nubians, Zulus, Kaffirs, and West Indians, using their native languages, retaining their national habits, and, to a great extent, their native costume.

The Roman Empire was maintained from its centre on the Bosphorus, somewhat as the British Empire is maintained from its centre on the Thames, by wealth, maritime ascendency, the traditions of empire, and organising capacity — always with the great difference that there was no purely Roman nucleus as there is a purely British nucleus, and also that the soldiery of the Roman Empire had no common armament, and was not officered by men of the dominant race, but by capable leaders indifferently picked from any race, except the Latin or the Greek. Dominant race there was none; nation there was none. Roman meant subject of the Emperor; Emperor meant the chief in the vermilion buskins, installed in the Palace on the Bosphorus, and duly crowned by the Orthodox Patriarch in the Church of the Holy Wisdom.

0 notes

Photo

From Justinian to Isaac Comnenus

The fact is that, for the five centuries from Justinian to Isaac Comnenus, the attacks on the empire, from the European side, at any rate, were the attacks of nomad, unorganised, and uncivilised races on a civilised and highly- organised empire. And in spite of anarchy, corruption, and effeminacy at the Byzantine court, civilisation and wealth told in every contest. Greek fire, military science, enormous resources, and the prestige of empire always bore down wild valour and predatory enthusiasm. Just as Russia dominates the Turkoman tribes of Central Asia, as Turkey holds back the valiant Arabs of her eastern frontier, as Egyptian natives with British officers easily master the heroic Ghazis of the Soudan — so the Roman Empire on the Bosphorus beat back Huns, Avars, Persians, Slaves, Bulgarians, Patzinaks, and Russians. We need only to study the history of Russia and of Turkey to learn how the organising ability, the resources, and material arts of great empires outweigh folly, vice, and corruption in the palace.

4. Of course a succession of victorious campaigns implies a succession of valiant armies; and there is nothing on which we need more light than on the exact organisation and national constituents of those Roman armies which crushed Chosroes, Muaviah, Crumn, Samuel, and Hamdanids. They are called conventionally ‘Greeks’; but during the Heraclian, Isaurian ephesus daily tour, and Basilian dynasties there seem to have been no Greeks at all in the land forces. The armies were always composed of a strange collection of races, with different languages, arms, methods of fighting, and types of civilisation. They were often magnificent and courageous barbarians, conspicuous amongst whom were Scandinavians and English, and with them some of the most warlike braves of Asia and of Europe.

National characteristics

The empire made no attempt to destroy their national characteristics, to discourage their native language, religion, or habits. Each force was told off to the service which suited it best, and was trained in the use of its proper weapons. They remained distinct from each other, and wholly distinct from the civil population. But as they could not unite, they seldom became so great a danger to the empire as the Praetorian guard of the Roman army. The organisation and management of such a heterogeneous body of mercenary braves required extraordinary skill; but it was just this skill which the rulers of Byzantium possessed. The bond of the whole was the tradition of discipline and the consciousness of serving the Roman Emperor.

The modern history of Russia and still more the native armies of the British Empire will enable us to understand how the work ©f consolidation was effected. The Queen’s dominions are at this hour defended by men of almost every race, colour, language, religion, costume, and habits. And we may imagine the composite character of the Byzantine armies, if we reflect how distant wars are carried on in the name of Victoria by Hindoos, Musulmans, Pa- thans, Ghoorkas, Afghans, Egyptians, Soudanese, Zanzibaris, Negroes, Nubians, Zulus, Kaffirs, and West Indians, using their native languages, retaining their national habits, and, to a great extent, their native costume.

The Roman Empire was maintained from its centre on the Bosphorus, somewhat as the British Empire is maintained from its centre on the Thames, by wealth, maritime ascendency, the traditions of empire, and organising capacity — always with the great difference that there was no purely Roman nucleus as there is a purely British nucleus, and also that the soldiery of the Roman Empire had no common armament, and was not officered by men of the dominant race, but by capable leaders indifferently picked from any race, except the Latin or the Greek. Dominant race there was none; nation there was none. Roman meant subject of the Emperor; Emperor meant the chief in the vermilion buskins, installed in the Palace on the Bosphorus, and duly crowned by the Orthodox Patriarch in the Church of the Holy Wisdom.

0 notes

Text

Slavery in First Empress

Given the assumed Iron Age setting of First Empress to me it feels... disingenuous not to cover the topic of slavery within the story. I’ve studied plenty of ancient cultures and the only people I’m aware of who didn’t practice slavery was the followers of Zoroastrianism under the Persian Empire. Under the Ancient Greeks, off of whom I based Queen Viarra’s people, slaves were bought and sold and traded like any other commodity or resource, and indenturing oneself or one’s family was a common and legitimate form of favor exchange or debt settlement.

For the most part, I tend to treat slavery as something normal in First Empress, but I also try to show the consequences. One example from later in the story, Viarra’s hegemony comes under attack by a coalition of Gannic (Gaul) tribes from the Vedrian Mountains that form the northern border of her kingdom. Repelling the invaders requires a massive mobilization of hoplites from her own and her allies’ city-states. Such mobilization isn’t cheap, and a defensive campaign just doesn’t produce the spoils of war that come from an offensive campaign.

Thus the most practical way to pay for this mobilization is in slaves captured from the invading tribes. And as these tribes were largely migratory, the families of the invading warriors are left vulnerable to the defenders’ retaliation once the warriors are defeated. The following scene is from Zahnia’s perspective and shows the grimmer side of the aftermath of war and conquest. It’s not particularly graphic, but it does show specific examples of captured invaders and their tribes people being enslaved and oppressed by Queen Viarra’s soldiers and allies. To help emphasize that this was considered ‘normal,’ I added in descriptions of kind and otherwise likable and heroic characters taking prisoners to keep for themselves or sell as slaves. Reader discretion for descriptions of ancient-world slavery.

Covering her mouth with one hand and grasping Elissa’s hand with the other, Zahnia wept with horror as Tollesian soldiers rounded up thousands of Vedrian slaves.

Across the camp, some of Captain Vola’s cavalry escorted over a hundred captives from whichever tribe they’d raided or demanded reparations from. Despite having once been a slave, Vola laughed and joked with some of the other riders, seemingly nonplussed at the sight of others’ enslavement.

Zahnia wept as Tapris, the nice hoplite who’d rushed to defend Zahnia and Elissa that night their camp’s defenses were breached, dragged a wailing, brown-haired boy away from his mother or sister. The woman screamed and sobbed, reaching after him as another soldier dragged her in a different direction.

The Gannic mercenaries and allies in Queen Viarra’s service were no more merciful toward their fellow Vedrians. She overheard a group of warriors debating whether the pregnant woman they’d captured would sell for less money or more money. Across the way, Zahnia saw a fistfight break out between two mercenary spear-warriors over a pair of handsome twin boys. Three hoplites rushed in to break up the fight.

Meanwhile, two of the observers from the Daughters of Avilee examined a naked, weeping shieldmaiden, still bandaged and recovering from battle injuries. Zahnia looked away when one of them wrapped her arm around the captive and made some kind of joke or innuendo to her companion.

The freedom that these tribespeople were losing and their treatment from their captors threatened to wrench Zahnia’s lunch from her stomach. Since many Tollesians and Venari and other peoples from around the Vestic Sea considered the Gannic paler skin and lighter hair exotic, many of these captives might eventually end up as decorative, household, or harem slaves, Zahnia knew—living trinkets for rich people to show off to their rich friends. Other slaves would end up in brothels, spending every day and night servicing dozens of infantrymen or sailors or nobles or whoever.

Many of the slaves, however, would be forced to work in the quarries, lumber camps, grain fields, or merchant galleys, toiling at back-breaking manual labor until they died from exhaustion or injuries.

Damn it, it wasn’t their fault that their leaders and warriors had declared war on Queen Viarra. But with many of their leaders and warriors dead or wishing to curtail the queen’s retribution, it was the people who now suffered her soldiers’ wrath. The slavers led away a very pretty, blonde teenaged boy who would probably end up as a catamite in the nobles’ brothels. Zahnia wept for him and for the other slaves.

The tears and screams dragged up dozens of memories for Zahnia—painful memories of her own enslavement and captivity. They were memories she thought she’d forgotten. She remembered now the raid on her home village. Soldiers from another city-state, she thought they were. Zahnia remembered them now—their shining, steel-tipped spears and their bronze and linen armor. They’d raided houses, murdered resisters, and demanded money and slaves from the village leaders. Zahnia, an orphan, had been given to them without hesitation.

She could see those men now. She could see them in the hoplites of Queen Viarraluca—hoplites of Zahnia’s beloved queen—now beating and enslaving others just as Zahnia had once been beaten and enslaved.

“Are you alright, Zahnia?” Elissa asked her.

Zahnia couldn’t answer, closing her eyes against the tears. Releasing Elissa’s hand, she turned to run. Not caring the direction, Zahnia ran as far and as fast as she could, barely registering Elissa calling her name. Out of the encampment and past the guards and palisades she ran. Tears burned her cheeks as she ran amid the pines, west or southwest of the camp. Deep into the woods she ran, finally collapsing at the foot of a great, tall pine.

Curling up on her side amid the grass and dirt, Zahnia coughed and sobbed, choking on the memories and the sights and sounds of others’ grief. Gradually, she dragged herself upright, scooting up against the tree trunk. Pulling her legs against her chest, Zahnia continued to weep against her knees.

Perhaps minutes later, perhaps an hour later, Zahnia heard calm footsteps approaching from the direction of the camp. Based on the length and authority of the stride, she had a pretty good guess who it was. Not looking up, Zahnia pressed her face into her knees.

“May I sit?” Queen Viarra’s voice spoke from a few feet away.

“Like I could stop you,” Zahnia bit out, still not looking at her.

“On the contrary,” her majesty disagreed. “You’re one of very few people whose permission I would ask and one of fewer from whom I would accept such a rejection.”

“I don’t care what you do,” Zahnia muttered.

The queen paused as if studying her, then stepped closer and sat beside her, armor clinking as she sat back against the tree.

“Would you like to talk about it?” Queen Viarra offered.

“Part of me wants to hate you for bringing me here,” Zahnia murmured, eyes still closed and her nose between her knees. “But you gave me a choice to be here. You warned me of how terrible war is and how I’d see things no one should have to and how coming with you would change me forever—and I chose to come anyway. I could have sailed back to Kel Fimmaril with Pella and Naddie and not had to know the sights and sounds and smells of warfare and conquest and enslavement. And... I kind of feel like there’s a part of you that would have preferred that,” she added, opening her eyes as the thought occurred to her.

“There is indeed a part of me that would have preferred that you returned to Kel Fimmaril to be with your friends,” Queen Viarra agreed. “There are horrors of war that no one should be exposed to, let alone a child. But this was a lesson I realized you’d need eventually as my chronicler, and I’d have stopped you from coming if I didn’t believe you were strong enough to handle it. You’re far too introspective to believe there’s anything good or honorable about any of this—and that is exactly the kind of chronicler I need. I don’t need or want a chronicler to stroke my ego, sing my praises, and to only portray my good side and great deeds. What I need is a chronicler who’s not afraid to disagree with me and not unwilling to portray the darker side of who I must be as queen and hegemon—one who understands the difficult choices I must make and the consequences of those choices.”

“I wish knowing and understanding things better made them easier to deal with,” Zahnia sighed, lifting her head enough to rest her chin on her knees. “I know that King Vedon and his allies started this awful war. I realize that they slaughtered and enslaved the people of Gillespar. I know that he’d do the same thing to our people if he’d won. And I understand that mobilizing our soldiers and allies against him was expensive and that the surest, most practical way to pay for that mobilization is with slaves taken from the invaders. But, gods, I wish there was another way!”

“So do I,” Queen Viarra sighed. “But slavery is how the world works. It plays an irreplaceable role in how resources are gathered, goods are produced, materials are transported, and trade is conducted. If there’s a culture that doesn’t rely heavily on some form of enslavement of others, I’m not aware of it.”

“But you’re–you’re one of the wisest and most powerful rulers on the Vestic Sea,” Zahnia protested, knowing she was grasping at straws. “Surely there’s something you can do to–to–to... to I don’t know. Couldn’t you phase slavery out or discourage it somehow or–or something?”

“How would you suggest I go about accomplishing either of those things?” Queen Viarra asked, sounding both patient and curious.

“I don’t know,” Zahnia sighed, looking down with defeat. She sniffed, scowling as she rubbed a tear from her eye.

“I’m a powerful monarch reigning over an expanding hegemony, but abolishing an institution that’s older than history itself is a task far beyond even me,” the queen admitted. “Though, I’m honored that you think so highly of my abilities.” Zahnia looked up to see Queen Viarra smiling down at her.

“Regardless, I’ll never live to see the day when humankind no longer conquers and enslaves its brethren,” her majesty shook her head, leaning back to stare into the distance. “Nor will my children,” she added, “nor will my children’s children, nor the children of my children’s children. Nor perhaps will anyone who can trace their ancestry back to me. But perhaps...” she paused, looking meaningfully down at Zahnia. “But perhaps, dearest Zahnia, you will live to see that day,” she concluded, raising her brows and reaching over to stroke Zahnia’s hair. “And perhaps when you chronicle those events for future generations to learn of, there will be deeds I accomplished and decisions I made within my lifetime that will have led to that day.”

Zahnia pursed her lips as she considered that.

#my writing#my novel#First Empress#Queen Viarra#Zahnia the Chronicler#Handmaid Elissa#Captain Vola#excerpts

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alexander III “The Great” Part 2: Where one empire falls, so must a new one rise...

Alexander the Great and the Macedonian army crossed the Hellespont into Asia Minor in 334 BC. The composition of his army at this point was primarily Greek but did include some non-Greeks as well. It consisted of a mix of cavalry and infantry. His cavalry included light cavalry mixing Greek and Thracian horsemen. While his elite cavalry was the heavy cavalry known as the Companions of which Alexander always lead into battle personally, leading his royal contingent, it was made of the Macedonian landed nobility which was personally quite loyal to the king. This was combined with Thessalian heavy cavalry from Central Greece as well. His infantry included missle and melee infantry ranging from the phalanx or phalangists to his hoplites and hypaspists and various armed skirmishers both Greek and Thracians such as the peltasts.

The Macedonian army was faced by the Persians who called on forces from all across the empire. Persians, Bactrians, Scythians, Sogdians, Syrians, Indians and even Greeks as mercenaries. They too had infantry, cavalry, archers and even armed chariots. Memnon of Rhodes, a Greek mercenary commander in Persian service advocated for a strategic withdrawal and scorch and earth tactics which would stretch Alexander’s supply lines and deny his forces food and supplies to forage or “live off the land”. However, the Persian satraps of Anatolia saw this move as both undermining to morale and not worthwhile because the scorched earth would be their own fertile lands, hurting long term commerce. Their contention was to fight the Macedonians head on before they ventured too far into the Persian Empire.

The first major battle, was the Battle of Granicus fought in May 334 BC in what is now western Turkey along the Granicus river, as was often the case Alexander would fight many of his classic battles along rivers. For his part this was strategic, the Persian armed chariots could not be effective on muddy river banks where mobility was slowed. The Persians knew the Macedonians would attempt to cross the river and hoped to slow their advance their by bunching up the Macedonian forces. The battle started with a feint attack on the Macedonian left, commanded by a trusted general, Parmenion who commanded the Thracian and Thessalian cavalry. The Persians shifted many of their forces to meet this attack but in doing so weakened part of their line, Alexander personally lead his noble Companion cavalry into battle in a flying wedge formation. In the melee, Alexander personally killed a number of Persian nobles but was nearly killed himself by one until a timely intervention by a Greek general named, Cleitus the Black severed the Persian’s arm clean off with sword still in their hand, saving Alexander’s life. The Macedonian center now had time bought and moved its phalanxes into place across the river, supported by the bulk of the army now pushed back the Persians, the speed of their advance surprised the Persian forces who after some tough fighting retreated. The retreat happened before they could commit their forces, namely the Greek mercenaries to battle. This resulted in the Macedonians killing their fellow Greeks in a general massacre, viewing them as a traitors for having served the Persians. Granicus was a resounding Macedonian victory, their first major one over the Persians.

The battle opened up Anatolia to the Greeks who began conquering the lands. Some Persian satraps in the next several months surrendered their territory without a fight, hoping to spare their damage. Alexander sometimes let Persians stay in their positions of power so long as they supplied his army and swore loyalty to him. Gradually, Alexander worked his way along the coast to neutralize the Persian naval bases that could cut off supply lines back to Greece. He also visited the city of Gordium which contained the fabled Gordian Knot which presented a riddle to many in the ancient world, the complicated and varied tied knot was a puzzle that required challengers to unravel it, the one who solved the puzzle was said to be destined to rule all of Asia. Many had contemplated how to unravel the knot but failed. Alexander’s solution was simple, cut the knot with his sword.

From Anatolia, Alexander hoped to advance into Syria and threaten the Levant. It was at this point that the Persian Shah, Darius III personally lead an army to counter the Macedonian threat. Darius’s army actually ventured behind the Macedonian army hoping to cutoff its supply lines and trap it deep in Persian territory with no hope of reinforcement. Alexander did however rise to meet Darius. They did do along the Southern Anatolian coast along a small river called Issus. The Battle of Issus was fought in a narrow ground between the mountains and the sea, the ground was chosen by Darius to limit the mobility of the Macedonian cavalry which had been so effective at Granicus. Darius’s army was as typical of the Persian forces was multiethnic and once again they relied on Greek mercenaries, arguably their best troops which Darius placed at the center with his royal bodyguard. The Macedonian advance across the river was slowed by the river itself, the Persians fortifying their bank of the river and the Greek mercenaries hard fighting. However, Macedonian hypaspists, tasked with guarding the phalanxes weak and vulnerable flank and rear managed to break through a line in the Persian-Greek forces. This allowed Alexander to see an opportunity to strike unexpectedly at the heart of the Persians. Taking his Companion cavalry, Alexander drove his force on a right flank maneuver and then wheeled toward the Persian center, straight at Darius. The speed and fury of the Macedonian charge at the Persian King of Kings completely unnerved Darius and he fled in his chariot. This collapsed the morale of the Persian center which also fled. On the left flank of the Macedonians, Persian cavalry held back Parmenion’s left flank cavalry. Ever the observer and adapter to the situations on the battlefield, Alexander would wheel his forces to hit the Persians now exposed rear. This surprise attack combined with the holes being punched in their mercenary forces and the flight of their king lead to a rout of Persian forces. The Macedonians pursued and killed off many retreating Persians, gaining yet another decisive victory. In the wake of this, Alexander captured members of Darius’s family including his wife, mother and two daughters. Alexander held them as prisoners though they were by all accounts well treated during their captivity. Darius himself retreated to the Persian capital in Babylon.

Over the next year or two Alexander consolidated his gains in Anatolia and advanced down the Syrian coast, taking the Levantine cities either by surrender and sparing them destruction or in the case of Tyre and Gaza having to besiege them and after many months finally captured both. Alexander then advanced to Egypt where he was proclaimed Pharaoh. He also visited a temple where the Egyptian priests declared him the son of their supreme god, Amon Ra. He introduced the Greek presence into Egypt and the Levant, something that was to last for centuries with the Greeks serving as Pharaohs of Egypt until Roman rule, with a Greek-Egyptian named Cleopatra being their last famed ruler, a descendant of the Ptolemaic dynasty that was established by one of Alexander’ s general, Ptolemy in the wake of Alexander’s death. Something new was happening due to Alexander and the Hellenic presence in Egypt. Greek and Egyptian culture to a degree synthesized and Greek culture was being spread to Persia’s various provinces. He would also found the first of many cities bearing his name, Alexandria, now one of Egypt’s major cities. It would become a famed center of learning and culture throughout the ancient world, blending Greek, Egyptian, Persian and other traditions into one center. This was to become a hallmark of Alexander’s rule and legacy, as he would spread Hellenic culture to other parts of the world and increasingly it would blend with the local culture becoming a hybrid of East meets West. Reflected in art, religion, currency, governance, commerce, day to day life and military tradition.

Meanwhile, back in Greece the mighty Sparta which had remained silent during Alexander’s Asian and African adventures finally rose up to challenge the Macedonians, Alexander nor his father directly fought the legendary Spartans and the question was raised who was mightier Sparta or Macedon. Antipater, one of Alexander’s generals who stayed behind in Greece would answer that burning question. The Macedonian army crushed the Spartans at the Battle of Megalopolis virtually fighting to the last man, killing their king in battle too. This subdued the Spartan rebellion and Greek discontent over taxes and Alexander’s rule in general.

Darius III offered several attempts at negotiations with Alexander as all of Persia’s western provinces and African ones, namely Egypt, were being conquered, some without a fight which was a humbling experience for the Persian Shah. His last offer at peace was to offer half of the Persian Empire to Alexander, all the Western provinces, to become co-rulers of the empire, to taken several thousand pounds of silver and gold as payment and to arrange a marriage between Alexander and one of his daughters. Alexander did seriously consider the offer and all but one of his generals argued against it. Alexander, refused seeking to have all the empire and not just half. The war would continue.

Alexander now marched his forces into Mesopotamia or modern Iraq with the goal of taking the Persian political capital, Babylon. Darius is believed to have anticipated the Macedonians would take a more direct route through the deserts of central and southern Iraq which with extreme heat and lack of supplies would drain their army. Darius however, once again realized he was dealing with no ordinary for. Alexander ever the clever strategist took his army on an unexpected route through Northern Iraq instead, nearing mountains that would shade or cool his forces from the intense heat of the deserts to the south. This caught the Persians off guard and Darius was forced to instead move his own army northward. Some Persians figured the Tigris River which the Macedonians numbering shy of 50,000 men would have to ford was too deep and strong. However, Alexander’s army did cross and was now moving toward Babylon on the east side of the river. Darius decided to find ground of his own choosing to meet and defeat the Macedonians. He found it on a relatively flat plain east of modern Mosul, Iraq at a place called Gaugamela.

By choosing an open expansive battlefield, Darius hoped not to be boxed in the way he had at Issus, this would allow more room for his chariots and cavalry to maneuver. His force was estimated by modern scholars of being upwards of 100,000. It included Indian war elephants and various contingents and mercenaries from all over the Persian Empire as was usual. Alexander however as was often the case, took an unexpected maneuver and initiative which offset the Persians. He moved his Companion cavalry from their right flank far out on what appeared to be an outflanking maneuver which deceived the Persians into thinking this was an maneuver that needed to be countered and indeed they sent a large force of cavalry from their left to meet and clash with the Macedonians. As the Persians drew their forces to mirror and counter Alexander’s deep flank, they weakened their own center as was Alexander’s plan. The deep flank was joined by his phalanx and hypaspists infantry which Alexander had gradually disengaged them from the flanking maneuver to meet the Persians center which fixed them in place. Meanwhile, the Persian chariots armed with javelin throwers advanced only for the Macedonian regiments to part forming alleys for the chariots to pass through without causing damage, before the chariot riders were killed themselves. Parmenion and the Thracian-Thessalian cavalry on the left also fixed the Persian right flank in place. It was now time for Alexander’s decisive move. The deep flank and the fixing in place of the Persian forces effectively weakened the Persian center by creating a gap which like at Issus, Alexander could strike at Darius’s jugular once more by driving his flying wedge Companion heavy cavalry right at the Persian center and split it’s force into pieces. Darius, once again caught off guard by the Macedonian deception and fury fled the battlefield, causing panic and routing in his forces. Parmenion’s left flank however was in jeopardy and just like as Issus, Alexander had to lead a counter charge to save his left from being overwhelmed which was encircled by Persian cavalry on all sides. Darius fled and evaded capture or death as Alexander had hoped, but preservation of his army was more key to the long term goals of Alexander. He attacked the Persians in their rear with some breaking off to loot the Macedonian camp before they were dispatched themselves. The rest of the Persian army fled as the Macedonians shifted their forces to left to relieve Parmenion. It was another victory and ultimately the final blow needed to defeat Darius and the Achaemenid Persian Empire.

Alexander entered the Persian capital of Babylon which he claimed to enter as a liberator, he also went onto the cities of Susa and the ceremonial capital of Persepolis which was in the Persian heartlands of modern Iran, he burned Persepolis as payback for the Persians burning Athens 150 years earlier in the Persian invasion of Greece under Xerxes. Now he was declared by his new Persian nobility Persian Shah himself and Lord of Asia, in addition to his titles as King of Macedon, Hegemon of the Hellenic League and Pharaoh of Egypt. Effectively the Persian Empire ceased to be a real force at least in the western provinces. Darius gave an impassioned speech to carry on the war in the eastern half of the empire which remained unconquered. However, his satraps, especially one by the name of Bessus had enough of defeats and retreat by Darius, they took him prisoner and murdered their Shah. Bessus was then self-proclaimed Shah but Alexander viewed Bessus as little more than an impostor, with himself as the real Shah and he considered the act of murdering Darius, the rightful ancestral King of Persia as cowardly and little more than petty and unjust, a crime punishable by death.

Darius’s body would be recovered by Alexander as he set off in pursuit of Bessus. He gave him a proper burial in the ancestral tombs of his dynasty. Alexander had respect for Darius’s position and an appreciation of the Persian monarchy’s history even if they were enemies on the battlefield. He now set about trying to consolidate a hold on his conquests through a mix of his Macedonian generals and Persians who proclaimed loyalty to him, becoming his new nobility and serving as provincial administrators. He began to administer Persia, though largely as Persia had been run, seeing himself not as a new conqueror but as rightful inheritor to the prior Persian dynasty, this admiration for Persia along with the adoption of certain Persian customs and the maintenance of Persian governors and administrators by Alexander started to cause some resentment among his generals who unlike Alexander simply despised the Persians and felt Greek traditions superior. The first cracks in Alexander’s otherwise impenetrable self-armor were starting to appear. Yet, there was much work to do, such as the capture of Bessus and the conquest of the eastern remnants of the nominal Persian Empire. Alexander’s gaze was fixed to the east to the ends of Persia and beyond, to the edge of the known world...

#Alexander the Great#darius iii#macedonia#persian empire#ancient greece#military history#military tactics#ancient world#granicus#issus#gaugamela

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Herodotus and the Egyptian physician (and collaborator of the Persians) Udjahorresnet

Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections

HERODOTUS’S PERSPECTIVE ON THE SITUATION OF EGYPT IN THE PERSIAN PERIOD FROM THE LAST SAITE KINGS TO XERXES’ FIRST YEARS

Reinhold Bichler

University of Innsbruck

“ABSTRACT The inscription on the famous statue of Udjahorresnet on the Musei Vaticani touches upon a number of historical events, which are reflected in Greek historiography. Taking up different aspects of Udjahorresnet’s career, the paper analyses Herodotus’ perspective on the Egyptian sea forces and the foreign mercenaries in Egypt, the different characterization of Cambyses’ deeds in Saϊs compared with those in Memphis, and the role the Egyptian physician plays in the Histories. Eventually, Udjahorresnet’s testimony about his presence on Darius’ side leads to a closer look at the notorious problems connected with the chronology of Darius’ first regnal years. By presenting the available evidence of Herodotus’ reception in the mid-5th century BCE of these 7th–6th-century BCE events, I hope to further a more diversified sources-based discussion on Udjahorresnet and his world.”

“V: SUMMARY The topics studied in this paper are triggered by different aspects of Udjahorresnet’s self-representation, beginning with his former position as “commander of the Royal navy” and his concern about the protection of Sais and the Sanctuary of Neith. The first section concentrates on the role Herodotus assigns to the Egyptian fleet in the Histories. He generally highlights its loyalty under Persian command during the “Persian Wars,” although Xerxes had crushed a rebellion in Egypt. A look further back shows a striking contrast between Herodotus’ report of successful maritime policies under the last Saites and his silence about any actions of the Egyptian fleet over the long period from Cambyses’ conquest until the outbreak of the Ionian Revolt. Section II presents a closer look at Herodotus’ perspective on the role of foreign, especially Greek mercenaries in the service of the Saite kings. Three times they play a major role in the dynastic change of power. Regarding the conquest of Egypt by Cambyses, Herodotus gives no indication as to whether the city of Sais had suffered any damages during the occupation. Cambyses’ notorious deeds as a “mad dog” are linked to his stay at Memphis. The third section, inspired by Udjahorresnet’s position as “chief physician,” examines the curious role Egyptian physicians play in the Histories. Herodotus connects Cambyses’ and Darius’ first deeds as conquerors and overshadows their achievements with irony. In both cases, he presents a pair of dubious actors: on the one hand two physicians, a vengeful Egyptian eye doctor and a picaresque Greek doctor (Democedes), on the other hand a pair of dubious “political” actors, a traitorous deserter (Phanes) and an exiled troublemaker (Syloson). Finally, in section IV we are confronted with the chronological problems connected with the first years of Darius’ reign. Therefore, Herodotus’ order of events, including his reports on the Egyptian governor Aryandes, is examined step by step and compared with non-Greek source material. It is in full awareness of these notorious problems that we have to consider Herodotus’ statement about the presence of Egyptian physicians at Darius’ court as well as Udjahorresnet’s testimony about his presence on his master’s side in Elam.”

The whole article can be found on file:///C:/Users/USer/Downloads/jaei-vol-26-07-bichler-herodotus-perspective.pdf

0 notes

Text

ANABASIS: THE MARCH UP COUNTRY, XENOPHON, 430?-355? B.C.

THE INNER ENEMY

In the spring of 401 B.C., Xenophon, a thirty-year-old country gentleman who

lived outside Athens, received an intriguing invitation: a friend was recruiting Greek soldiers to fight as mercenaries for Cyrus, brother of the Persian king Ataxerxes, and asked him to go along. The request was somewhat unusual: the Greeks and the Persians had long been bitter enemies. Some eighty years earlier, in fact, Persia had tried to conquer Greece. But the Greeks, renowned fighters, had begun to offer their services to the highest bidder, and within the Persian Empire there were rebellious cities that Cyrus wanted to punish. Greek mercenaries would be the perfect reinforcements in his large army.

Xenophon was not a soldier. In fact, he had led a coddled life, raising dogs and horses, traveling into Athens to talk philosophy with his good friend Socrates, living off his inheritance. He wanted adventure, though, and here he had a chance to meet the great Cyrus, learn war, see Persia. Perhaps when it was all over, he would write a book. He would go not as a mercenary (he was too wealthy for that) but as a philosopher and historian. After consulting the oracle at Delphi, he accepted the invitation.

Some 10,000 Greek soldiers joined Cyrus's punitive expedition. The mercenaries were a motley crew from all over Greece, there for the money and the adventure. They had a good time of it for a while, but a few months into the job, after leading them deep into Persia, Cyrus admitted his true purpose: he was marching on Babylon, mounting a civil war to unseat his brother and make himself king. Unhappy to be deceived, the Greeks argued and complained, but Cyrus offered them more money, and that quieted them.

The armies of Cyrus and Ataxerxes met on the plains of Cunaxa, not far from Babylon. Early in the battle, Cyrus was killed, putting a quick end to the war. Now the Greeks' position was suddenly precarious: having fought on the wrong side of a civil war, they were far from home and surrounded by hostile Persians. They were soon told, however, that Ataxerxes had no quarrel withmthem. His only desire was that they leave Persia as quickly as possible. He even sent them an envoy, the Persian commander Tissaphernes, to provision them and escort them back to Greece. And so, guided by Tissaphernes and the Persian army, the mercenaries began the long trek home--some fifteen hundred miles.

A few days into the march, the Greeks had new fears: their supplies from the Persians were insufficient, and the route that Tissaphernes had chosen for them was problematic. Could they trust these Persians? They started to argue among themselves.

The Greek commander Clearchus expressed his soldiers' concerns to Tissaphernes, who was sympathetic: Clearchus should bring his captains to a meeting at a neutral site, the Greeks would voice their grievances, and the two sides would come to an understanding. Clearchus agreed and appeared the next day with his officers at the appointed time and place--where, however, a large contingent of Persians surrounded and arrested them. They were beheaded that same day.

One man managed to escape and warn the Greeks of the Persian treachery. That evening the Greek camp was a desolate place. Some men argued and accused; others slumped drunk to the ground. A few considered flight, but with their leaders dead, they felt doomed.