#Zahnia the Chronicler

Text

Viarra was terrifying when angry and not much less so when merely annoyed. She suffered fools only when they proved themselves useful, and she could be just as ruthless against unreliable allies as she was toward her enemies.

---From Empress Viarraluca: Life of a Titan, by Zahnia, the Chronicler

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Many scholars, historians, playwrights, and troubadours have attempted to pin down my exact role in the formation of the Tollesian Empire under its first empress, Viarraluca I. The fifth-century epics and legends that portray Zahnia, the Chonicler as some mystic mentor-figure to the young Empress Viarra are entertaining but wholly inaccurate. Later stories that portray me as sort of a shadow-figure manipulating Tollesian politics behind the scenes aren’t really any more accurate, though there’s more overlap between history and espionage than I think most people realize. The twelfth-century playwright Katu Tiazu’s satires that portray me as Viarra’s cheeky sidekick are surprisingly closer to the truth, though still an oversimplification of our relationship. The early historical novelist Larcia Alpui’s Viarriad series is the closest so far, though the fact that she sought me out as a consultant for her novels has a lot to do with it.

---Zahnia, the Chronicler

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prelude

Another more recent addition to my manuscript for The First Empress: Book I is the following Prelude by Zahnia, the Chronicler. Since I want readers to understand that Zahnia is going to be an important character in later stories, I decided to begin the story with an excerpt from one of her works. This is still kind of a rough draft, so any feedback is welcome!

Excerpted from Empress Viarraluca: Life of a Titan, by Zahnia, the Chonicler, Biographer for Empress Viarraluca I

Sometimes even the most competent rulers of the most powerful nations find themselves unable to stem the tide of change. Sometimes a potent enough ruler from a backwater polis can completely change the course of history. The conqueror of the Vestic Sea and surrounding lands, Empress Viarraluca I’s life and legacy have captivated the imaginations of nearly a hundred generations of scholars, playwrights, and later even novelists and screenwriters over the past 1,800 years. She was a skilled warrior and capable warlord, though not nearly the warmonger that certain later and contemporary critics would accuse her of being. Her prowess showed through during the Vedrian campaigns, the last Illaran War, the great sea-battle off the coast of Tutna, her defense of Kammaliya, and her invasion up the Arville River, cementing her reputation as a military leader. Even her defeats at the Siege of Valos and the Battle of Temetteni demonstrated her ability to recover from near-catastrophe and the value she placed on preserving the lives of her soldiers.

Even in her teens, Viarra cut a poignant contrast from the youthful heroes and heroines we’re used to in history and entertainment. Far from the baby-faced idealist we find in the later King Teucer the Great or the winning smile that the young Empress Larthia IV was famous for, Empress Viarra was huge and imposing even at sixteen or seventeen years. Rather than the brash optimism we see in sci-fi hoplite Lecnes Lightwielder, his mother and arch-nemesis the Black Myrmidon might be a better comparison. Viarra was terrifying when angry and not much less so when merely annoyed. She suffered fools only when they proved themselves useful, and she could be just as ruthless toward unreliable allies as she was toward her enemies.

And yet I’m not aware of a time during her reign where Viarra failed to remember that her subjects were the most important part of her job. She never built a palace to display her greatness or even a triumphal monument to celebrate her victories. Every building she commissioned, whether through tax money or spoils of conquest, was either a public building or public work. Throughout her empire, she commissioned schools and libraries to educate her citizenry, temples for her citizens to worship at, theaters for the latest plays, markets and emporiums for trade, housing for the lower classes, baths to help keep her people clean and healthy, sewers and other drainage to keep her poleis clean, wells and above-ground aqueducts for fresh water, stronger walls to protect vulnerable cities, and even harbors and bridges for improved travel. Had arched bridges and paved, deep-bed roads been invented in her time, I’ve no doubt Viarra would have launched a massive highway-building program, similar to that of co-empresses Velimnei and Seianti in the 230-60s AE.

The point being that Empress Viarraluca was far from what most people expected, both during her reign and after. Her political and geopolitical rivals, in particular, frequently made the mistake of assuming Viarra thought similarly to them—that she had similar goals and used similar tactics and methods of achieving those goals. The aristoi who conspired against her in 5 BE suffered worst from this lack of understanding, while Viarra’s more dangerous rivals like Queen Sita and Emperor Orvandius quickly realized that the standard geopolitical strategies would be worse than useless against her.

Viarra’s prowess in warfare, in the political arena, and even in the bedchambers with other women have all been thoroughly discussed and analyzed throughout history, but serious scholarship on who she was as a person has only been a major focus for a little over two decades. Everyone knows she led dozens of battles, executed or exiled plenty of corrupt aristoi, and shagged more queens and princesses than should be physically possible in a single lifetime. But who was Empress Viarra as a person? Was she a cat-person or a dog-person? Did she prefer tea or wine? What kind of plays and literature did she enjoy? Which charioteers did she cheer for at the hippodrome?

While these and similar questions have been discussed in other scholars’ research as well as my own, this text is my attempt to look comprehensively beyond Empress Viarraluca’s mighty accomplishments as empress and more closely at who she was as a human being. As well as being a scholarly account of Viarra’s personality and psychology, I hope Life of a Titan serves as an effective tribute to the incredible ruler who once took in this nine-year-old girl with a strange curse of eternal youth, starting me out as her personal chronicler and biographer. She turned my curse into a gift and granted me the chance to share that gift with the world.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Aaaa! My sweet girls! Zahnia and Pella from The First Empress, hanging out together and playing with a top. Huge thanks to Telenia Albuquerque (@9musesandanoldmind) for the amazing Christmas present!

Zahnia (left) is an immortal, cursed by mad scientists/evil wizards to never age past nine-years old. Pella is around 12 years old and was given four arms by the same madmen. After their daring escape from their captors and many exciting travels, they come to serve Queen Viarra---Pella as a handmaid and Zahnia as a chronicler/historian. I wish I could give Telenia a high-five in person for bringing them to life for me!

#Telênia Albuquerque#my writing#my novel#First Empress#Zahnia the Chronicler#Pella#commissions#character art

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don’t personally think of the rise of the Tollesian Empire as a renaissance, as such. Renaissance tends to imply a prior deficit of advancement in culture, art, technology, and engineering—which there wasn’t exactly a lack of prior to empire. The concept of [Empress] Viarra’s reign heralding a renaissance was popularized by self-aggrandizing imperial historians attempting to portray the empire as inherently superior to independent [city-states]. If nothing else, competition between rival [city-states] drove advancement in all of the above categories.

--Zahnia, the Chronicler from The First Empress

Another of my favorite Zahnia footnotes.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Warrior Princess in Exile

Link: https://www.heroforge.com/load_config%3D46566089/

As mentioned a while back, I'm planning a spin-off of sorts to The First Empress, starring Viarra's mom, the Warrior-Princess Lutaxa of the Andegamni tribe. Lutaxa's people are based on the ancient Celtic tribes, and in particular the Pre-Roman Gauls. My working title for the story is Warrior Princess in Exile, though I'm open to other names. I finished the first full scene earlier and thought I'd share it here. As always, feedback and comments are welcome!

“Though she was mother of one of the most powerful women in the world, Lutaxa of the Andegamni was never crowned queen of anywhere. Technically she was princess-consort of Kel Fimmaril when she gave birth to the future Empress Viarraluca and her brothers. Meanwhile, she was more of a warlord or war-chief to the Andegamni tribe than queen. As Iron-Age Gannic tribes rarely kept a calendar, we can’t know for sure when she was born, though sometime in late 55 or early 54 BE seems most probable. While Empress Viarra was famous for her gargantuan height, we know that Princess Lutaxa was slightly taller, and like her daughter was also famous for her bright copper hair. She was reputed to have a will like iron and an edge like obsidian. And although she wasn’t present for Viarra’s famous usurpation of the Hegemony of Andivel that began the great empress’s rise to power, we know from accounts by Viarra and her colleagues that Lutaxa was a mighty warrior-princess in her own right and bequeathed both her martial prowess and political savvy to her Titan of a daughter.”

—from Empress Viarraluca: Life of a Titan, by Zahnia, the Chronicler

35 BE, Early Summer

Part of her wishing she didn’t have to wear this bronze helmet and scale-armor on the most humid day of the summer so far, Princess Lutaxa of the Andegamni tribe took a swig from her water-skin as she watched the approaching scout riders. She wiped sweat from her eyes, trying not to smear her blue and black war-paint more than it already was. The weather wasn’t even particularly warm, but the inescapable moisture in the air bordered on oppressive.

“What d’ye report?” she demanded as the scouts rejoined the rest of the four-hundred-warrior war-band.

“Is like ye grandfather predicted,” a tall, shirtless spear-warrior named Velitax reported from his horse. “The traitor Cenali and their allies send another war-band tae attack our fortifications from behind.”

“Up the old wagon road?” Chief Adgenix—Lutaxa’s second-cousin and Grandfather’s master-of-horse—asked as he trotted up beside her.

“Aye,” a brigandine-clad shield-maiden named Cavarixa confirmed, nudging her horse closer. “We think seven-hundred strong.”

“From clothes and the crimson war-paint, I recognized their guides from the Iatta tribe,” Velitax added.

“So much for the Iatta’s claims of neutrality,” Adgenix groused behind his long, droopy brown mustache.

“Or maybe they have traitors of their own,” Lutaxa offered. “Grandfather, Father, and the others can piece that together when the Cenali and their allies are defeated. For now, let’s deal wi’ these foes so we can get back tae Grandfather and the rest of the army!”

“Aye, Princess,” Adgenix nodded, grinning and thumping his fist against his bronze breastplate.

“I’ll take the shield-warriors and hunters and hit their vanguard’s flank, while ye take ye horse-warriors and hit their rear as hard as ye can,” Lutaxa ordered. “Let’s see if we cannae smash the rest of their war-band between us and drive them back intae the forest.”

“Aye!” Adgenix grinned again. The scouts rode off with him to rejoin the rest of his seventy-odd cavalry-warriors.

Hefting her shield and spear in her left hand and two javelins in her right with her broadsword dangling from her hip, Lutaxa gave a quick, sharp whistle to signal the rest of her warriors to move out. Her copper hair was twisted up into a topknot and tucked under her conical bronze helmet. The helmet included hinged cheek-flaps to protect her face and a short, angled brim to deflect arrows away from her head. Painted dark blue with wolf-like devices, her wooden shield was tall and oval-shaped, held behind a central bronze boss. Under her scale armor, Lutaxa wore a maroon-dyed, long-sleeved wool shirt with crimson, navy, and pine-colored checkered pants. Lastly, she wore soft-leather ankle-boots to partly muffle her steps.

The wealthier warriors and shield-maids in her band were armed and dressed similarly, some with leather brigandine or bronze plate instead of scales or with tall, hexagonal shields instead of oval. Most of these warriors were either nobles who could afford to buy armor and spend most of their time training or were veterans who’d used spoils from past victories to buy armor and better weapons.

Most of her warriors, however, were conscripted farmers and tradespeople who wore little if any armor and carried either tall oval shields or more often simple round-shields. These warriors usually carried a single spear and a few javelins with maybe a dagger, hatchet, or cudgel as a sidearm. Hunters and huntresses conscripted into Grandfather’s army served as ranged support and typically carried either a longbow or shield and sling with sidearms similar to the poorer warriors. Though the conscripts’ training ranged from rudimentary to nonexistent, the Gannic tribes were a naturally strong and hardy people made mightier by harsh northern winters.

All shades of brown, black, blonde, red, or copper could be found among Gannic hair colors. Northern Gan tended to wear their hair long and wild, twisting it into topknots before going into battle. Though younger men sometimes grew short beards and older men often grew long beards, the more common facial hair was beardless with long, drooping mustaches. And while it varied from tribe to tribe, many men and women also plucked or shaved their body hair during the spring and summer.

Most Gannic shield-warriors and shield-maidens wore war-paint and dyed wool garments plain or with striped, checkered, tartan, diamond, or herring-bone patterns—though fighters who went shirtless were not uncommon. Zealots of warlike gods such as Vindicatus or Atepu were known to fight with only their weapons and war-paint. As in, no clothes: just spears, swords, and shields, with scrotums or snatches bared to all.

While Lutaxa could appreciate the courage it took to charge into battle stark-naked as well as the harrowing effect that screaming, painted nudists could have on enemy morale, such zealots tended to fight bravely and die quickly.

Admittedly, her war-band was a far cry from the disciplined, semi-professional Venarri armies and mercenary Tollesian phalanxes she’d encountered during the two years she’d spent fighting as a mercenary for the Venarri kingdoms and city-states to the south. The Tollesian hoplite sell-spears had been particularly impressive, with their tall spears and bronze or linothorax armor, and Lutaxa remembered being relieved her warriors were fighting beside them instead of against them.

Uncle and Grandfather had used the pay and spoils their tribe acquired from those campaigns to fund this war against the treacherous Cenali. After two years of campaigning, Grandfather—the great War-Chief Camulatix—had forced their foes into a grand showdown at the fortified village of Carix. Expecting the Cenali to send a flanking force around the nearby mountain to attack the village from the west while the main Cenali horde attacked the eastern and southeastern fortifications, Grandfather had assigned Lutaxa’s war-band to locate and ambush this force.

Creeping amid the trees a quarter-mile south of Carix’s stone- and palisade walls, Lutaxa located the wagon-road that she knew the Cenali would be using. Crouching with her warriors amid the tall grass, brush, pines, and other foliage, she readied her javelins and war-horn for the enemy’s arrival. Minutes later, she could hear the tramping of horses’ hooves amid the muttering and footfalls of leather-booted or barefoot warriors.

Crouching nearby, a stark-naked shield-maid named Saglia made a low growling noise as the first invaders came into view. Daughters of Atepu—followers and priestesses of the divine patroness of women warriors, huntresses, and jilted brides—were known to be particularly fearsome, painting their bodies in garish designs and bleaching their hair with lime. Saglia muttered a war-chant to herself, wearing only her blue-and-crimson war-paint, her bleached hair twisted into a topknot that dangled above her right ear.

Armed, clad, and painted similarly to Lutaxa’s war-band, the Cenali vanguard consisted of a few dozen mounted warriors mixed with shield-warriors and hunters. The Gan tending to be a fairly tall people with a lengthy stride, these warriors maintained a steady, mile-eating pace in order to reach their destination quickly and still have enough stamina to fight.

Once the enemy war-band came parallel to her group, Lutaxa raised her war-horn to her lips and blasted out the attack signal. All at once, her band let out their savage battle-cry and loosed their javelins, arrows, and sling-stones into the enemy’s unshielded right flank. Throwing both javelins before charging in, Lutaxa grinned as the first javelin took a rider from his horse while the second tore into a spear-warrior’s leg. The melee warriors led the charge, screaming and shouting as they engaged the startled invaders.

Using the slope to her advantage, Lutaxa screeched a battle-cry her mother taught her and rushed down upon a cavalry-warrior who was trying to get his frightened horse under control. Not giving him the chance, she shoved her spear deep into his kidney. The warrior screamed and fell from his horse, bleeding heavily. The horse responded by freaking out and charging off into the pines.

Lutaxa turned just in time to deflect a spear-thrust with her tall shield. The unarmored spear-maid facing against her managed to block Lutaxa’s return attack but found herself forced to back off as another of Lutaxa’s warriors attacked her unshielded side. Unable to handle the press of the Andegamni warriors, the young spear-maid tripped backward over one of her fallen comrades.

The spear-maid had beautiful golden hair, Lutaxa decided, and could potentially be a valuable battle-captive. Instead of stabbing her to finish her off, Lutaxa flipped her spear around to smack the woman in the temple to knock her out.

As the shield-warriors assailed the vanguard, the hunters, slingers, and javelin-warriors still amid the trees turned their missiles toward the middle of the enemy column, not yet engaged. Lutaxa smirked as two enemy warriors dropped their weapons and ran into the pines on the other side of the wagon-road.

Using her height and the leverage it gave her, Lutaxa punched her shield downward against an enemy shield, staggering the shirtless warrior backward. As the warrior stumbled, she used the opening she’d created to stab her spear deep into his chest.

Around her, the enemy vanguard crumbled at her warriors’ assault, more and more survivors fleeing into the trees. Screaming out another battle-cry, Lutaxa stepped over her fallen enemy to engage a grizzled warrior in what looked like an older bronze breastplate looted from a Venarri foe. The enemy warrior snarled and threw a javelin from less than ten feet away before drawing his broadsword and charging. Lutaxa knocked the javelin aside with her shield before side-stepping his charge and stabbing out with her spear. The spear struck less than an inch too low to catch the warrior’s unprotected armpit, instead deflecting off his bronze cuirass.

As the warrior turned to face Lutaxa, however, the shield-maiden Saglia shrieked out a war-cry and threw her spear into the side of the bronze-clad warrior’s head. Though the spear wasn’t balanced for throwing and the older warrior’s helmet deflected the attack, it knocked him off balance enough that Lutaxa could shove her spear deep into the bastard’s neck.

Lutaxa decided to include seducing Saglia as part of her victory celebration. Meanwhile, Saglia drew her broadsword and raced forward to pounce shield-first on another enemy warrior, tackling him to the ground and stabbing him repeatedly as she frothed at the mouth.

As Lutaxa’s war-band continued to cut their way through the enemy warriors and hunters, a cry came from the back of the enemy mob that they were under attack from both sides.

“Horse-warriors!” an enemy shouted. “We’re attacked from behind!”

Tall enough to easily look over the heads of the struggling Cenali warriors, Lutaxa smirked at the sight of Adgenix’s cavalry scattering the enemy rear-guard. Beset from two sides, the Cenali and their allies stood less than a minute before their horde broke. Lutaxa stabbed through a javelin-hunter’s defenses, her steel spear cutting deep through his chest and pinning the bastard to the ground as he fell. Drawing her broadsword, Lutaxa looked about to see the enemy scattering.

“Chase the fockers tae the river!” Lutaxa screamed to her warriors, a victory cheer going up from their ranks.

In a victorious frenzy, her war-band charged headlong after their routing foes, cavalry taking the lead and trampling deep into the disintegrating enemy war-band. Lutaxa and her shield-warriors chased down and cut down or captured every fleeing Cenali they could catch while her hunters and javelin-warriors lobbed their projectiles at retreating backs.

A deep river flowed less than a quarter-mile to the south of the wagon-road. Venarri merchants she’d met had a name for the river, but Lutaxa couldn’t recall it. Swift and bloated from the spring melt-off, the river was over an eighth of a mile across and was unfordable this time of year. Nevertheless, many Cenali warriors threw down their arms as well as armor if they wore it, leaping into the swift waters to escape the Andegamni warriors’ retribution. Many others threw down their weapons and surrendered.

Lutaxa estimated perhaps two hundred enemies struggling in the swift current. A few hunters lobbed arrows or sling stones after the escaping swimmers. At least one enemy warrior screamed as an arrow stuck deep in his back. The poor bastard screamed and thrashed, bleeding heavily as the current carried him off.

“Save ye arrows!” Lutaxa ordered, sheathing her sword and breathing hard from the battle adrenaline. “Any fockers can make it across deserve tae escape. Ye,” she continued, turning to a surrendering enemy spear-maid in leather brigandine and a bronze-rimmed leather cap. “Who’s in charge of ye war-band?”

“Fock if I ken,” the red-haired, freckled warrior admitted as one of Lutaxa’s warriors took her sword and dagger and another bound the woman’s hands. “I watched ye slay Chief Vocorix with ye own spear. I dinnae ken who’s left in charge after him.” She titled her head. “Ye are Princess Lutaxa, aye?”

“Aye,” Lutaxa confirmed. So the grizzled warrior that Saglia helped her slay must have been their war-chief.

“Ye reputation precedes ye,” the spear-maid nodded. “I suppose Chief Vocorix dinnae expect ye Chief Camulatix tae send his mightiest grandchild tae fight us.”

“Flattery will get ye everywhere,” Lutaxa smirked, raising the woman’s chin with two fingers. The spear-maid was handsome and brawny, probably in her thirties and looked like an experienced fock. Maybe Saglia would like tae share a battle-captive tonight, she mused to herself.

“Secure the prisoners and round up our wounded and theirs!” she barked to her war-band. “Adgenix,” she added, addressing him and handing the captive spear-maid off to her warriors. “Have ye horse-warriors stay alert in case any Cenali who escaped try anything. Once we’ve secured the captives and wounded, ride ye horse-fockers back tae Grandfather’s horde, see if ye cannae help the battle there. We’ll catch up tae ye.”

“Aye,” Chief Adgenix smirked before turning his mount to gather his horse-warriors.

When she was around fourteen winters old, Lutaxa rode her first battles with Adgenix’s cavalry—back when she was still small enough and light enough to ride in combat. While still a proficient horsewoman, her size and weight tended to reduce her mounts’ speed and stamina significantly, especially when riding with full armor and kit. As such, she tended to prefer to lead the charge beside the shield-and-spear warriors.

“Make any looting quick, loves!” Lutaxa added, watching a young spear-warrior conscript trying on a bronze helmet from a dead Cenali warrior. “If needed, we can loot them more thoroughly when we come back tomorrow tae gather our dead.”

A few nearby warriors grumbled, but not loudly.

“Saglia!” Lutaxa announced upon spotting her new favorite Daughter of Atepu. “Thank ye for ye help fighting they war-chief, love!”

“Aye, ye are most welcome, ye highness!” Saglia laughed, stripping a bronze dagger with an antennae-style crossguard and pommel from a dead warrior. From another corpse she took a leather bag full of what sounded like knucklebones. She scrounged a leather cord to tie both, since being naked she didn’t even have a belt to tuck them into.

“As thanks, would ye care tae celebrate by sharing a battle-captive or two with me tonight?” Lutaxa asked, kneeling to help up an allied warrior with a leg-wound.

“That sounds fun!” Saglia agreed, moving to support the warrior’s other side. “I will warn ye,” she added, “I have focked three men tae death, so dinnae bring any captives ye want tae keep alive.”

“I cannae tell if ye are serious,” Lutaxa observed, looking over the wounded warrior’s head at her.

“Aye, she’s serious,” the injured spearman nodded, limping between them. “One of them was my poor, stupid cousin who heard she focked two men tae death and decided tae try her anyway. Dumb bastard died from a broken pelvis.”

“Aye, two men died from broken pelvises, the other from a ruptured bladder,” Saglia added. “Several others were injured for weeks.”

“I killed a man in bed, but he was an assassin sent by the Cenali,” Lutaxa admitted. “He disguised himself as a bed-slave tae get close tae me. I was a bit surprised when he drew a knife, but he was even more surprised when I swatted his knife away with one hand and broke his neck with the other before he could react,” she added, flexing her huge left hand. “Any of ye injured partners women?” she asked next.

“Nae sae much,” Saglia shook her head. “Focking a lass needs a different technique and motions, aye? Lads get hurt, but lasses just cannae walk straight for days.”

“I think ye and I will get on great,” Lutaxa laughed.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some background on The First Empress

So the following excerpt was going to be my original foreword for The First Empress. Last October, however, I was informed in a rejection letter that the foreword was too long (among other, more homophobic reasons for rejecting it). Then, when I looked up how to write a foreword, I found out that, at least in fiction, it's customary to have someone else write it for you. While Matthew Keville (@matthewkeville) was kind enough to write my new foreword, I kept the original foreword, and at a beta reader's suggestion I think I'm going to use it as an "About" page for my website. Content warning for background and personal history.

I think it was fall semester of 2002 at Boise State University. During one of my literature courses, the professor was highly impressed with my reading responses for Homer’s Iliad, particularly in regards to my observation that the story is in no way a conflict between good and evil. And I liked that about it. I liked that there were noble and ignoble characters as well as likable and unlikable characters on both sides of the conflict. In his notes on one of my responses, Professor Jim recommended that I read Thucydides’s History of the Peloponnesian War, which began my interest in ancient history in general and Classical Greece in particular. One of my college friends owned a lovely little coffeehouse/used bookstore for several years, and I bought many volumes out of her ancient history section.

In the late ‘00s, I developed acute depression/anxiety while working on my Master’s Degree in Literature. Though I somehow managed to complete my degree, my depression became so severe that in 2011 I had to step down from a teaching job I loved beside colleagues I liked, because I couldn’t function well enough to fulfill my duties outside the classroom. I decided it was horribly unfair to my students that they couldn’t count on me to do my part, so I walked away. I made the most painful decision I’ve made in my life and stepped down from a job I’d spent three years studying and training for.

My first successful step toward recovery came when I started writing for myself again. No more thirty-page theses, no more ten-page research papers written over the weekend, no more feedback on forty-to-sixty student papers. I typed up some story concepts and revisited some old stories that I hadn’t looked at in a decade. I started a blog, and then a side-blog, and then a Tumblr page to go with the side-blog. I even started a fan-fiction account that features mostly The Legend of Korra novellas and Star Wars one-shots.

During the summer of 2012, I wrote several chapters of a young-adult fantasy novel in a high- to late-medieval setting, featuring a young, somewhat Mary-Sue heroine whose wizened mentor was named Zahnia, the Chronicler—an immortal historian trapped forever as a nine-year-old girl. As I started to flesh out Zahnia’s character, I decided I wanted to explore her origin story, tying it in with the creation of the Tollesian Empire, where the story takes place. For National Novel Writing Month 2012, I began work on the first draft of The First Empress and spent over ten years tinkering, expanding, and revising in my free time. But the more I worked on the story, the bigger it got. George RR Martin once described a spectrum of writers, ranging from architects who outline and design the structure and foundation of their story before they start writing, to gardeners who plant the seeds of the story, then let it grow, expand, and develop organically. I’m very much the garden-variety writer.

And so the story kept getting bigger, both in my head and on paper. I fell short of the original 50K word goal by over 10K, but felt like I had a pretty solid start. By the end of that first NaNoWriMo, I knew that it was probably going to be multiple books, so I narrowed down what I wanted to include in Book I and started focusing on those story lines. The original story was to be two separate stories that converge at the end of Book I, with the main story focusing on the title protagonist, Queen Viarra, and the first year of her rise to power, while the background story focuses on Zahnia, the curse of her immortality, and her escape from her captors. In the original outline, Book I would end with our characters first meeting.

Even in the early stages, however, it was extremely difficult to reconcile the two stories. Viarra’s story was over twice the size of Zahnia’s and, for the most part, more exciting for my beta-readers. Zahnia’s scenes often felt like unwelcome interruptions, rather than interesting interludes, and were difficult to intersperse side-by-side with scenes happening in Viarra’s story. At some point in the process, I stopped trying to intersperse them and made Zahnia’s scenes separate chapters. While this worked better, there could be as many as four or five Viarra chapters between Zahnia chapters, and some of my readers pointed out that they sometimes had to go back and reread previous Zahnia chapters to understand what was happening in the latest chapter. I occasionally thought about taking Zahnia’s story out altogether and making it its own novel.

I made my ultimate decision on the matter in July of 2021 when I finally finished the first complete draft of The First Empress. The draft weighed in at over 206K words—which I knew was a lot, but I didn’t grasp the full size until one of my readers pointed out that in paperback format, that’s over eight-hundred pages! I decided almost immediately that the best option was to split them up into three books. Books I and II now deal entirely with the first year of Viarra’s rise to power, meeting Zahnia, her future chronicler, at the end of Book II. Book III is instead mostly about Zahnia’s origins, including her curse of immortality and her daring escape from the madmen who cursed her. This worked out wonderfully as it allowed me to break the revision process into smaller chunks instead of attempting to revise 800 pages in one go.

Though Zahnia isn’t physically present for Book I and only gets a single scene in Book II, I make sure she’s still present in spirit throughout both books. In homage to classic fantasy stories like Frank Herbert’s Dune or Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series, I include epigrams written by Zahnia at the beginning of each chapter. Additionally, all footnotes and appendices are also by her. Despite her unavoidable sidelining in what was supposed to be her origin story, Zahnia became something of an alter-ego for me, and I want readers to understand that she is still a foundational character in the series.

While brainstorming leading up to that first NaNoWriMo, I decided to put my studies of Ancient Greek history to use, basing the setting and culture on the late-Classical, early-Hellenic Aegean Sea and the surrounding regions. The culture, politics, and technology—both in how they begin and how they advance as the series progresses—are intended to feel similar to the cultural, political, and technological changes occurring in the wake of the Peloponnesian War through the rise of Kings Philip II and Alexander the Great and beyond. Indeed, Philip and to a lesser degree Alexander were both inspirations for Queen Viarraluca, my title heroine.

(That being said, I don’t tend to view any of my characters as being an equivalent of X figure from Greek history. I drew inspiration from many historical and fictional characters for my cast, but I don’t have a story-world equivalent of Socrates or Pericles or Leonidas or Sappho or Olympias or whoever.)

The setting, though, is less intended to feel historically accurate and more about feeling historically authentic. I’ll be the first to admit that I’m a hobbyist historian who hasn’t taken a history course since early in my undergrad studies. Thus, all of my reading and research is unguided, and I have no idea how well my understanding and analyses align with contemporary views. Ultimately, The First Empress is an ancient-world period-fantasy that’s inspired by rather than entirely representative of late-Classical Greece.

Throughout the process, I loved playing with the ancient-world world-building and found perverse enjoyment in taking pagan gods’ names in vain, portraying ancient inventions as new and exciting technology, and treating pants as an unusual and barbarian garment. But as a fantasy, I of course included plenty of embellishments. Sometimes world-building is brainstorming how an intelligent warrior queen and her officers would attempt to adapt a hoplite-centered army to fighting in forested terrain, generally considered unfavorable to phalanx warfare. Sometimes world-building is giving a society based on the Ancient Greeks access to tea, despite zero evidence that the Ancient Greeks had anything similar to tea, all because my warrior-queen protagonist seems like a tea-drinker.

I tried as well to include neighboring cultures inspired by those the Classical Greeks had contact with. The Tollesians are inspired by Classical Greece—the Empire Pellastor and its allies being akin to the Attic and Peloponnesian Greeks while the Hegemony of Andivel and their allies are more like the Ionian Greeks. The Illaran League was originally inspired by the Ancient Illyrians but evolved into more of an Illyrian/Macedonian hybrid. The Gan are inspired by the Gauls. The Venarri are Phoenician. The Artilans are Achaemenid-era Persian. The Kossôn are Achaemenid-era Egyptian. The Wattasu are inspired by Classical-era Nasamones. And the Verleki are largely inspired by the Ancient Scythians. I want to emphasize inspired by, as I’m not an expert on any of these ancient cultures. I have no illusions that I didn’t make mistakes or misinterpret things. I also eventually hope to include cultures inspired by the Samnites, Germanic tribes, Kushites, and possibly even cultures as distant as the Han and Mayans.

Experimenting with ancient-world cultures and in particular with ancient-world sexuality has been some of the most fun I’ve had writing. The Classical Greeks were an openly sexual culture, openly bisexual and often polyamorous. Rather than gloss over their sexuality like a coward, I chose to let my characters embrace it in the story. In doing so, I quickly decided that authors who only write monogamous, heterosexual relationships are missing out on all kinds of wonderful and fascinating relationship dynamics. Queen Viarra is a lesbian, and nearly all of the other characters fall somewhere on a pan- or bisexual spectrum. Zahnia, meanwhile, is asexual, as is one of Viarra’s ambassadors. I have a transgender hoplite officer, as well, and I have other characters in mind for future LGBT+ representation. As bisexuality was normal and even expected in Classical Greek culture, I try to treat it as something normal in my stories as well.

Though so far only one person has asked me why I’d include LGBT+ characters when I’m not LGBT myself, my answer to them and anyone else is that positive representation is important. Louie, my therapist, shared an anecdote during one of our sessions back in 2021 and gave me permission to share with readers. He was hosting some friends of his family for a few days, including his childhood friend who is a lesbian. His copy of my manuscript was lying around, and he started telling them about my lesbian title protagonist who’s also a strong ruler and a formidable warrior queen. His friend was very curious and asked smart questions about the character and story-world. Louie told me that she almost teary-eyed asked him to thank me for writing the characters as gay. She apparently was thrilled not only at the gay representation from the leading couple, but also at the bi representation from other characters.

When a gay woman in her late forties gets teary-eyed at the inclusion of a lesbian couple in a period-fantasy novel, I think it’s a sign that this kind of representation is absolutely necessary.

On the other hand, there were other aspects of Classical Greek culture that I wasn’t as keen about attempting to portray. The Greeks at the time were notoriously misogynist, for example. Much of Greek culture viewed women as property. Athens in particular had all kinds of laws restricting women, including a truly heinous law specifying that female slaves’ court testimonies were only valid if they testified under torture. I did away with a lot of that in my story-world. Scythians, Illyrians, Nubians, Sarmatians, Lusitanians, Suebi, Gauls: plenty of ancient cultures had traditions of skilled huntresses, warrior women, women pirates, influential queens and noblewomen, and successful businesswomen. Philip II of Macedon’s first wife was warrior queen, and he allowed their daughter and granddaughter to be trained in the same manner. That the Classical Greeks couldn’t get with the program is frankly their loss.

As this is my story-world and my tale to tell, I saw no particular reason to carry on that tradition. Queen Viarra isn’t the only powerful queen in the story, nor is she the only woman-warrior in hoplite’s panoply. Though a certain level of misogyny exists, it’s on the level of individual characters or communities, rather than a cultural norm.

Why?

Because it doesn’t have to be a norm! It’s fiction! Misogyny and sexism don’t have to be normal! Racism doesn’t have to be normal! Homophobia and transphobia don’t have to be normal! I shouldn’t have to create a hateful story in order to meet some mouth-breathing neoclassicist’s concept of historical accuracy. One of the best things I learned from reading Effie Calvin and Garrett Robinson’s novels is that truly excellent and inclusive stories with engaging characters, world-building, and conflicts can be created without some need to incorporate real-world prejudices. And when these prejudices do show up in The First Empress, I try to set them up as criticisms of ancient society, rather than something I lazily included for some pretense of “historical accuracy.”

At least three of my beta-readers compared The First Empress favorably to George RR Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire series. (To paraphrase one of my Tumblr readers, any fantasy with historical inspiration and more politics than wizards will draw Game of Thrones comparisons.) Even so, not only would I never assume to be in the same league as an award-winning fantasy author whose stories have sold countless millions of copies and gotten their own popular television adaptation, I don’t feel like Martin’s goals as a storyteller are at all similar to mine. His stories seem to place the most emphasis on shocking readers—and he’s unparalleled at it! My goal is to give readers a lot to think about. Hopefully I pull that off well.Plus, if readers can handle A Song of Ice and Fire… I think The First Empress might seem a little mellow by comparison.

Thanks so much for your interest in my book, folks. I hope you find my story and characters entertaining, interesting, thought-provoking, or at the very least enjoyable to read. Thanks for reading and take care!

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Appendix B: the Tollesian Pantheon

As an additional aid for readers of The First Empress, I typed up a short who's who of the deities mentioned in the story. None of the gods actually show up in the story, and I basically leave it up to readers whether or not said gods actually even exist. Thematically, I want the Tollesian gods to have a similar feel to the Greek Pantheon, without directly copying them straight across.

The Tollesian Pantheon:

A Brief Who’s Who Among the First-Generation Tollesian Gods

—By Zahnia, the Chronicler

The Tollesian Pantheon (known as the Vestic gods among many non-Tollesian theologians) refers to all of the gods worshiped by the Tollesian-speaking peoples. Like many pantheons, the hierarchy of the Tollesian gods consists of one or more Elder Gods or Titans who created the first generation of offspring gods, who in turn reproduced to create minor gods, demigods, and mortal heroes of divine parentage.

Like many creation stories, Tollesian folklore personifies the Sun as the ever-watchful father of his children here on Mother Earth. The first generation gods, or Titans, are children of the Sun and Earth, who are responsible for the caretaking of the planet and the wellbeing of her inhabitants. And though this volume focuses primarily on Arr and his better-known descendants, modern theologians and classicists estimate as many as five-hundred and seventy deities were worshiped over the course of the Classical-era, with dozens of gods and goddesses falling into and out of obscurity during that seven-hundred-year period. Tollesian legends also mention at least thirty Titans aside from Arr, as well as countless demigods and goddesses. Not to mention giants, monsters, muses, nymphs, wraiths, angels, demons, and even spirits of personified concepts, any of which may or may not also be demi-deities.

Arr

God of fate, time, destiny, Tollesianism, judgment, heaven, loyalty, fidelity

Patron cities: Aneth, Arr Patuna

Symbols: clouds, sundials, scales, dogs, full circles

Arr is the father of the first generation of Tollesian gods and one of few remaining Titans not imprisoned in the Underworld. Having been betrayed by his fellow Titans and forced to imprison many of them during what Tollesian theologians call the Great Division, Arr is inherently mistrustful of deities outside his family and is even more mistrustful of foreigners who follow non-Tollesian gods. Arr is most popular among the more isolationist city-states upon the Vestic Sea. Non-Tollesian theologians often suggest that Arr’s judgmental attitude toward xenoi was the religious and thereby cultural cause of many Classical-Era Tollesians’ mistrust of foreigners and foreign gods.

Thanusa

Goddess of death, rebirth, fertility, mortality, the cycle of life and death

Patron Cities: Pultus, Tiphilia

Symbols: rabbits, flowers, beehives, eggs, vulvas, skulls, the Phoenix

Thanusa is Arr’s wife, fellow Titan and mother of the first generation of Tollesian gods. It’s not ucommon for modern historians and worshippers to misunderstand Thanusa’s role as goddess of death in Classical Tollesian theology. Earlier portrayals depicted her as a guide or guardian ensuring that souls of those who’ve died find their way to the afterlife. Around the 320s AE the first tragedies and satires came out featuring Thanusa as a callow, unfeeling villainess who cut off lifelines of those whose time had come[1]. The worst offender was whichever playwright invented that trope where the hero or heroine saves their dying loved one by interrupting Thanusa before she can cut their lifeline. Discerning whether someone knows this is a popular method among modern classicists of sorting out the semi-educated.

AndivaGoddess of justice, order, law, civilization, expansion, spread of Tollesian culture

Patron cities: Andivel, Vislow, Chyllar

Symbols: scales, columns, owls

Andiva is the first-born of Arr and champion of the expansion of Tollesian culture into other lands. As such, she is most popular among major cities which border on barbaroi lands. Like her father, Arr, Andiva is mistrusting of foreign gods, but unlike him encourages nonbelievers to convert to Tollesian religion, thought, and culture.

Zupor

God of strife, war, destruction, warriors, physical strength, martial prowess

Patron cities: Pellastor, Ryllar, Partha

Symbols: spear and shield, hoplite helm, fire

Zupor is known across the Vestic Sea as the god of war and strife, and is the second of Arr’s children. Poleis which follow Zupor most closely tend to have a strong warrior caste—or at least place a special emphasis on having a well-trained force of hoplite elite.

Nyrus

God of the sea, sailors, overseas trade, storms, tides, male bisexuality

Patron cities: Illarra, Fildor, Tutna

Symbols: orcas, waves, tempest, sailing ships

As god of the sea, Nyrus is among the more popular patron gods among costal and island poleis. Third of Arr’s children, Nyrus is also father or grandfather of the Nereids, sea nymphs equally famous for saving or drowning Tollesian sailors.

Cibades

God of agriculture, farmers, planting, harvest, wine, brewing, vineyards, fertility

Patron cities: Clenia, Mertal, Vindel

Symbols: plow, wheat, goblet, grapes, scythe, sickle

God of wine and wheat, Cibades is fourth of Arr’s children, and patron god of polies famous for their wine or beer production and to a lesser degree of breadbasket poleis.

Kralor

God of knowledge, learning, wisdom, teachers, students, critical thinking, literacy, writing, science, art, philosophy, music

Patron cities: Ovec, Thornic

Symbols: scroll, book, abacus, lyre, drum, quill

Though not always most cunning of the gods, Kralor is by far the most learned. Father of the Muses. In the Tollesian tradition of wholeness of body and mind, Kralor is frequently depicted as a warrior-philosopher or scholarly wrestler.

Ido and Iva

God and goddess of love, romance, sexuality, fertility, marriage

Patron cities: none

Symbols: the heart, the lovers, roses, rabbits

Ido and Iva are twin god and goddess of love and romance. While Ido and Iva have no patron cities as such, their clerics and priests are frequently called upon during marriages and rites of fertility in towns and cities across the Vestic Sea.

Ferra

Goddess of medicine, healing, physicians, health, sanitation, fertility, wholeness of body and mind, female bisexuality, same-sex marriage

Patron cities: Kel Fimmaril, Noro, Ferra Arte

Symbols: the serpent, burning incense, mortar and pestle, leaves and herbs, midwives

Ferra is the goddess of health and medicine and was particularly popular among smaller city-states such as Noro and Kel Fimmaril. As a goddess of fertility, theatre frequently portrays Ferra as somewhat overly prolific—sluttish, really—giving birth to nearly half of the second generation of gods, goddesses, and demigods. According to legend, however, Ferra would later marry and forsake all other lovers for her younger sister Avilee.

Suvie

Deity of the wilderness, mountains, forests, jungle, hunting and trapping, natural selection, gender queerness, gender nonconformity

Patron cities: Gillespar, Hastia

Symbols: mountains, trees, bows and arrows

Hermaphrodite deity of the forests, variously portrayed as either a beautiful, bow-toting goddess of the hunt or as a virile, spear-wielding warden of the forests. Additionally, Suvie is the parent and guardian of such forest spirits as wisps, fey, Dryads, Naiads, and fauns.

Avilee

Winged goddess of protection, defense, common soldiers, fallen soldiers, bereft mothers and widows, war orphans, battlefield medicine

Patron cites: Voris, Ortenia, Aula

Symbols: spear, javelin, guard dogs, shepherd’s crook, hoplite armor

Wife of Ferra and youngest of Arr’s children, Avilee is also humblest, most caring, and most protective among the Tollesian pantheon. As such, she is also most beloved among her siblings, often acting as a mediator between her more quarrelsome kindred. Early in life, upon seeing the grief and destruction caused by her brother Zupor’s war and strife, Avilee took it upon herself to protect the common soldiers and care for the victims of war, be they fallen soldiers or bereft families. She is generally depicted with great, hawk-like wings and full hoplite panoply, wielding a spear and shield or bow and arrows.

Second-Generation Tollesian Gods

Vepu

God of the afterlife and the Underworld

Patron Cities: Tanythe, Zunia

Symbols: skulls, bones, ashes, urns

Vepu was a mortal king who so impressed Thanusa with his management skills that she elevated him to godhood to rule and organize the Underworld and its afterlife.

Arrolus

God of naval warfare, warships, marines

Patron Cities: Descal, Tarsa

Symbols: war galley

Arrolus is the son of the war-god Zupor and a Nereid huntress named Gale.

Orova

Goddess of night, shadows, trickery

Patron Cites: None

Symbols: bats, wraiths, shadows, blackness, the moons

Orova is the best-known Tollesian trickster goddess, a daughter of Ferra and an unknown Titan. Her favored ally is a wraith named Anache. Not necessarily evil, Orova is the most chaotic and capricious of the Tollesian gods.

Pharesthus

God of smithing, mining, iron and bronze

Patron Cites: Velia Cestini Symbols: hammers, ingots, anvils, forges

Pharesthus is the son of Ferra and an ancient giant named Sherto.

Clanti

Goddess of merchants and trade

Patron Cities: Vislow, Ortenia, Lecne

Symbols: coins, purses, scales, trading galleys

Clanti is the oldest daughter of Ferra and Nyrus as well as twin sister of the god Curé. Satirically speaking, she was considered the second-most-important god of the Illaran Confederation.

Curé

God of bandits, pirates, burglars, and thieves

Patron Cities: Illarra, Adis

Symbols: daggers, slings, raiding galleys, purse-cutters

Curé is the son of Ferra and Nyrus and twin brother to Clanti. Both satirically and literally, he was regarded as the most important god of the Illaran Confederation.

Axu

God of gender assignment and gender presentation

Patron Cities: none

Symbols: none

Daughter of Suvie and Ferra, Axu’s primary duty is assigning humans their gender at either at birth or conception, depending on the particular theologian.

[1] Truly, the quickest way for an author or playwright to kill my interest in their work is to portray Thanusa as a villainess. This was a character who felt deeply for those who’d died—especially those who died unjustly—and whose ancient stage-masks nearly always portrayed her weeping. Portraying her as a murderess remains one of the worst character-assassinations in the history of Tollesian literature and theatre.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Novel Title?

So here’s a question for my readers: does First Empress an optimal title for my novel series? I’d originally adopted it as a place-holder title for the story and never really paused to reevaluate it. Does it work as a title, or would something like The First Empress Chronicles or The First Empress Annals have a stronger ring? In particular, I ask because the story is framed as being part of an ongoing historical work by Zahnia, the Chronicler. Or does it help to just add the article and make it The First Empress? I’m open to thoughts and feedback!

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Appendix C: the Tollesian Calendar

So the final appendix for The First Empress: Book I discusses the calendar that the Tollesian peoples use. Technically, the Imperial calendar doesn't exist yet in the story, as it begins in 6 BE, just three days before the New Year, and 205 years before the calendar was created. Appendix B and Appendix C both started as notes to help me organize my thoughts and help keep track of both chronology and world-building. Eventually, I thought these might be helpful for readers, as well, and decided to clean them up and edit them for publication.

Appendix: the Tollesian Calendar,

discussion and analysis by Zahnia, the Chronicler

As most know, the Tollesian year is divided into three-hundred and sixty-two days, the year beginning and ending with the Spring Equinox. Ferra’s Month and Arr’s Month, the first and last months of the year, have thirty-one days. The remaining ten months contain thirty days. Though the system of years changed in 200 AE, to the best of our knowledge the names of the months have stayed constant since before recorded history.

Imperial Calendar Years

The Imperial System of calendar years was established in 200 AE (After Empire) by Emperor Valashna II to commemorate the bicentennial anniversary of the unification of the Tollesian Empire under Empress Viarraluca I in what is now regarded as 0 AE. All years leading to unification are labeled BE (Before Empire) and count backward from year 0.

Though self-congratulatory as the move was, it was highly endorsed by scholars and historians across the empire at the time—and not just the ones the emperor’s cronies paid off to endorse it. The move quickly became popular among the citizenry across the Vestic and surrounding lands because it offered them something concrete to latch onto and identify with. The previous Tollesian calendar, now referred to as the Founders’ System, counted up from a mythical date allegedly seventeen-hundred and fifty-eight years prior to the establishment of Viarraluca’s Empire.

According to legend, the Tollesian peoples descended from refugees from a collapsing empire. Historians tentatively identify the dying empire as the Bronze-Age kingdom of Manarce, to the northwest, along the western shores of the Tornis Sea. These refugees settled three major cities: Aneth, Thornic, and Venetesh—the latter of which fell into ruin around 600 BE and was located near the modern city of Arr Patuna. The Founders’ System allegedly dated from the landing of these settlers and the construction of these cities.

While surviving literary evidence from these time periods sort of corroborates the Founders legends, archeological evidence does not. The earliest known major settlement at Aneth dates to around 1100 BE, while Thornic and Venetesh couldn’t have been settled before 900. Moreover, artifacts and human remains from these archaeological sites don’t match those of the Manarcean Empire or any other contemporary Bronze-Age empire of the time. And even by Viarraluca’s time, many scholars and skeptics had come to doubt the validity of these tales.

Naturally, plenty of traditionalists from Aneth, Thronic, and the surrounding regions balked at the idea of instituting a new set of calendar years that undermined the importance of the founding of their cities. Yet most citizens of the Tollesian Empire and its client nations were quite content to accept the new system. It gave them a more tangible and exciting chronology to tie themselves to, culturally, and it was relatable to peoples outside of the traditional core Tollesian poleis. The Imperial System exists to this day throughout the Empire and many of the nations it maintains relations with.

Seasonal effects

Unlike more northern climates, the Vestic and Istartus Seas have relatively mild summers and winters. Their summers are hot and frequently humid and winters rainy and cold, with moderate rainy seasons in between. As well as effective growing seasons, the fairly minimal snowfall allows for the limited growth of winter-crops, in particular winter-wheat and winter-barley. More pertinent to Classical Tollesian culture was how the four cardinal seasons affect agriculture, travel, and warfare.

Agriculture

During Queen Viarraluca’s time, only spring and autumn were thought of as agricultural seasons in Tollesian and other cultures on the Vestic and Istartus Seas. Landowners and their douloi and hired hands tended to plant and work ground during the early- to mid-spring and harvest during the late-summer and early fall. Once the campaign season began in late spring, the geomoroi and aristoi farmers traded spades for spears and left the day-to-day tending of the farm to their douloi and hirelings. The regular rainfall around the Vestic Sea helped facilitate dryland farming, though a few areas, particularly along the northwestern rim, imported Kossôn gravity-irrigation techniques in 108 BE to supplement less dependable rainfall.

Even today, the relatively mild winters with their steady rains and infrequent snows allow farmers on certain parts of the Vestic to plant winter-grains. The discovery of winter-crops by farmers in Messya in the 600s BE allowed poleis to better supply armies during the early campaign season or stock cities besieged by invaders.

Travel and trade

Only the northern and more mountainous regions around the Vestic Sea receive an annual snowfall, but travel is still severely limited in the wintertime due to frequent rains on land and violent storms at sea.

Though ancient cities and townships managed to offset this somewhat with cobbled roads, rural roadways were nearly untraversable during the rainy season. Occasional efforts were made to cobble some of the major trade roads, but winter rains tended to cover up their efforts within a few years. While travelers on foot or on horseback could generally traverse the roadways with moderate-to-considerable difficulty, the mud rendered wagons completely unusable, reducing overland trade to almost zero.

The regular winter storms and squalls rendered the seas similarly unusable. In addition to the heavy rain and treacherous waves, the overcast skies significantly compounded navigation. Warships, merchantmen, and courier ships, no matter how sturdy, were forced to cling to shorelines for safety, and even then are risked a great deal by setting out. Island city-states, meanwhile, received virtually no travelers or trade during the winter months.

Warfare

The reliable rainfall and prevalence of douloi and workmen allowed geomoroi farmers and wealthy landowners plenty of free time over the summer months to wage war. Leaving their children, workers, and douloi to tend the farms after planting, geomoroi and wealthy hoplites donned their armor and shields either to plunder their neighbors’ land or defend their own. Farmlands’ vulnerability to raids from rival city-states influenced many farmers to thus take up defensive arms, while the promise of gold, luxuries, slaves, and other spoils encouraged others to invade their rivals.

Though skirmishes and raids could continue until well after the harvest season, this was when the bulk of hoplites put up their spears for the winter. Campaigns and sieges had to take harvest into account, in terms of travel times and food supplies. Many a besieged city spent its summer counting the days until the attacking hoplites were forced to return home for the harvest season.

This was the norm for Tollesian city-states for over seven hundred years, but the increased presence of Gannic, Verleki, and other non-agricultural invaders necessitated a paradigm shift in military organization. Unhindered by planting and harvest seasons, more and more encroaching barbaroi increased their raids during spring and autumn. And being from northerly climates, the Gan in particular lacked the Tollesian reluctance to fight during the cold, rainy winters. These non-seasonal attacks forced many city-states, particularly along the northern coastlines, to keep standing armies year round, paying eleutheroi, apeleutheroi, and disenfranchised geomoroi to patrol the trade roads and protect the borders during even the coldest, wettest winter months.

This in turn led to a class of semiprofessional soldier in some poleis, with down-on-their-luck geomoroi selling or renting out their farms to buy hoplite panoply and restless nobles using their savings to buy top-line weapons and armor. While many of these fought for the defense of their polis, many others took up as sell-spears, fighting for whoever offered coin. Even by Viarra’s time, more than a few military experts argued that with agricultural seasons and farming schedules no longer dictating troop availability, farther-reaching conquests lay in the future for the Tollesian city-states.

Months

The Tollesian calendar year is divided into twelve months. Most months have thirty days, except Cibades and Arr’s months, which have thirty-one. Ferra’s Month is also unique in that every seven years a Leap Day is tacked onto the end. The day is generally celebrated with feasting and libations, and children born on Leap Day are often considered good luck for their polis, town, or village.

Ferra’s Month

Named for the goddess of rebirth, medicine, and fertility, the first month of the calendar year begins on the Spring Equinox. Around the Vestic Sea, Ferra’s month is mostly rainy, but the first two weeks also see the final tapering off of the winter storms that make sea travel on the Vestic potentially suicidal for nearly four months of the year. Early crops are typically planted by the Feast of Ferra on the 20th, and planting season is usually in full swing by the end of the month.

Suvie’s Month

Suvie’s Month is the second month in the calendar year and is named for the hermaphrodite deity of the forest and wilderness. The last of the summer crops are typically planted by the end of the first week. The Tollesian campaign season generally begins by the third week, the geomoroi hoplites having finished their planting and the seas generally safe enough to transport soldiers. The second week is considered the beginning of the ‘Dry Season’ on the Vestic’s northwestern islands and rim, typically only getting a few inches of rain until autumn. Most of the rest of the islands and surrounding mainland continue to get sporadic showers throughout the summer, however. Feast day is on the 16th.

Zupor’s Month

Named for the Tolleisan god of warfare and slaughter, the Tolleisan campaign season is typically in full swing by Zupor’s Month. As such, the month tends to see more battle and bloodshed than any other month of the year. Additionally, the previous year’s winter crops are close to ready to harvest, often providing a plentiful food source for besieged cities or for raiding and besieging armies. Zupor’s month ends on the Summer Solstice. Zupor’s feast day is on the 8th.

Nyrus’s Month

Named for the patron god of the Vestic, Istartus, and Tornis Seas, the Month of Nyrus begins upon the Summer Solstice, which is also the Feast of Nyrus. Many island city-states maintain a tradition of blessing ships built during the springtime during the first week of the month. Summer raids, skirmishes, and sieges are still ongoing. Most winter crops not stolen or destroyed are harvested by the second and third week of the month.

Avilee’s Month

Named for the goddess of protection, fallen soldiers, and bereft families, Avilee’s month marks the winding-down of the campaign season and the start of the harvest season. Most armies are withdrawn from enemy territory and disbanded to allow the farmers in the army time to return home for the harvest. Avilee’s Feast Day on the 28th is a feast of mourning, commemorating the soldiers and civilians killed or missing during the campaign season.

Cibades’s Month

Dedicated to the god of agriculture, farmers, and the harvest, Cibades’s Month is when the bulk of the harvest is conducted. By this time most raiding and skirmishing and all but the most belligerent of sieges have been called off to allow the geomoroi farmers who make up the bulk of hoplites to return to their fields. The Feast of Cibades is technically on eve of the Autumn Equinox on the 30th, but many city-states put it off until the last of the harvest is hauled in over the next few weeks.

Andiva’s Month

The month of the goddess of order and justice begins on the Autumn Equinox and marks the end of the harvest and transition to winter. Though post-harvest raids and skirmishes between belligerent city-states aren’t uncommon, there isn’t a dedicated season, and most blockades are kept short and sieges are almost nonexistent. Regions able to support winter crops tend to plant them around this time. Andiva’s Feast Day is the 16th.

Kralor’s Month

God of knowledge, science, and art, as well as father of the Muses, Kralor’s month marks the beginning of the winter season. The regular rainstorms on land and sea compound both aquatic and overland travel. Though rural villages and townships continue to send out hunters to supplement their winter supplies, most city-states rely primarily on their harvest food-stores to get through the winter. Trade tapers to almost nothing, and few battles or skirmishes occur. The Feast of Kralor is on the 18th.

Orova’s Month

As goddess of darkness and shadows, it’s fitting that Orova’s month is the darkest of the year. All of the Vestic Sea remains mostly overcast and rainy while frequent storms wrack the waves and coastlines. The mountains around the Vestic and islands with high enough elevations receive most of their snow during this time. Orova’s Feast is on the 30th, during the Winter Solstice when the Tollesian world is darkest.

Vepu’s Month

God of the afterlife and the Underworld, Vepu’s month begins following the Winter Solstice. As with Orova’s month, the Vestic Sea remains mostly overcast with frequent rains and storms. Higher elevations continue to receive more snow. The Feast of Vepu is on the 24th.

Thanusa’s Month

Mother of the gods and patron of death and rebirth, Thanusa’s month is marked by a gradual warming in the Vestic’s climate. Storms become noticeably less violent, and the higher elevations may experience cold rains that lead to early melt-offs. Thanusa’s feast is on the 10th.

Arr’s Month

Father of the gods and patron of fate and destiny, Arr’s month is the last in the Tollesian calendar. Marked by warmer rains and less-frequent storms, Arr’s month ushers in the coming year and rebirth of spring. His feast on the 31st is a celebration of the Spring Equinox and well as the possibilities of the coming year.

1 note

·

View note

Text

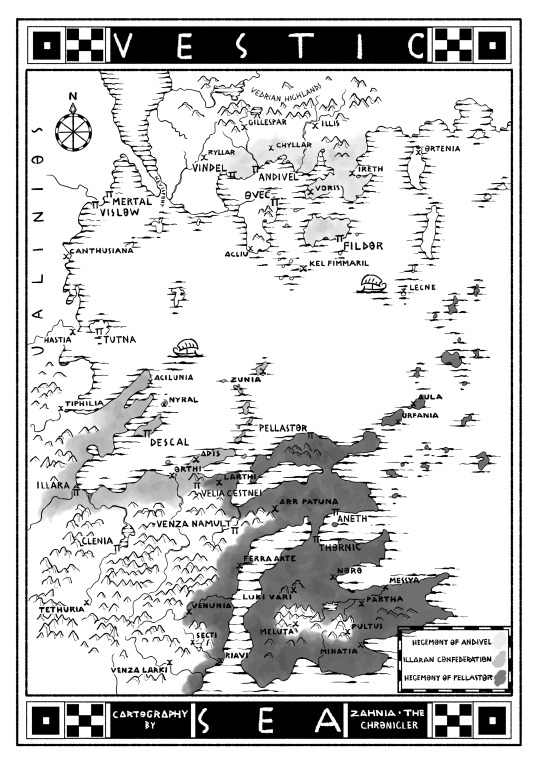

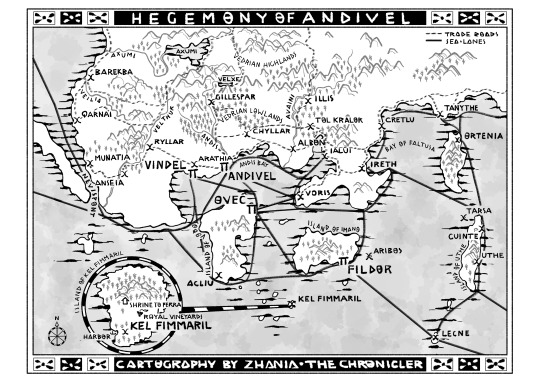

Maps!

Hey, so check it out, yesterday night I received the maps I commissioned for my novel from my amazing artist friend, Telenia Albuquerque (@9musesandanoldmind)! And since they came at 11:19 my timezone, they totally count as birthday gifts! Feel free to check them out and offer feedback, if you're interested!

The first map is of the Vestic Sea and it's three main powers, the Hegemony of Pellastor, the Illaran Confederacy, and the Hegemony of Andivel, the last of which Queen Viarra usurps from the ruling tetrarchy.

Map 2 is a closer look at the Hegemony of Andivel and its surrounding territory. Since the story frequently emphasizes the importance of the local sea lanes and trade roads, I felt it wise to include them on the map as well to give a visual illustration of where they go.

I think Telenia did a fantastic job with the Classical Greek aesthetics, but I'm also very open to feedback. What works for readers? What doesn't work as well? What would folks like to see more or less of? Let me know what you think!

13 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Like any great ruler, Queen Viarra wasn’t afraid to fight downright nasty in the political arena—and not just against her rivals. If a current or former ally needed made an example of for corruption, warmongering, or downright incompetence, said ally might find themselves exiled, fined, assassinated, cuckolded, or some combination thereof.

Zahnia, the Chronicler

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Queen Viarra’s Ladies

So I now that four arms options exist in Hero Forge, I went ahead and designed minis for Queen Viarra’s ladies, as well as Viarra in noncombat attire. (Not that she needs combat attire to kick ass.) Below we have Viarra, Elissa, Zahnia, Pella, and Naddie:

Viarra’s preferred colors are dark blues and dark greens, so most of her dresses tend to fit along those lines. I just wish Hero Forge would add more Ancient Greek clothing aesthetics to their lineup. I also like that the new hand poses allow her to look like she’s about to draw steel on some misogynist nobleman.

Elissa is Queen Viarra’s handmaid, girlfriend, and later royal concubine. She’s a very humble and unassuming character who loves being beside her queen, but hates being so close to the center of attention. I tried to make her modesty apparent in her design.

Tiny, ageless Zahnia is Queen Viarra’s chronicler, historian, and biographer. Experimented on by evil wizards/mad scientists, Zahnia and her friend Pella escape their captors, eventually finding themselves in Queen Viarra’s service. Recognizing Zahnia’s introspectiveness and resourcefulness, as well as the advantages of her immortality, Queen Viarra has her taught to read and write and trained to be her court historian.

Pella with Queen Viarra’s cat, Corsair. Pella was given four arms by the same experimenters who made Zahnia immortal. While most people urge Pella to hide her arms, Queen Viarra and her handmaid, Naddie, tell her to show them proudly. Queen Viarra assures Pella that her arms are beautiful and nothing to be ashamed of. Naddie assures her that she’s the best hugger and kitten scratcher in the world.

Naddie is Queen Viarra’s youngest handmaid. Bright and inquisitive, Naddie admires everything about her queen, and loves being around the many amazing women in Viarra’s entourage. She openly believes Zahnia and Pella are the coolest girls she’s ever met, and she hopes to one day be in a relationship like Viarra and Elissa’s. I’m currently considering her for Pella’s future wife.

#Hero Forge#my writing#First Empress#Queen Viarra#Handmaid Elissa#Zahnia the Chronicler#Pella#Naddie#miniatures#minis

21 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Being generous with one’s friends and loyal subjects is hardly mutually exclusive with exacting ruthless vengeance against one’s foes.

Zahnia, the Chronicler

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chronicling a Lesbian Warrior Queen

(Art by @mjbarros)

The last couple of evenings I’ve been writing out some of my thoughts on how Queen (later Empress) Viarra’s lesbianism becomes part of her power network. I’ve discussed this before, but as I was writing my thoughts out, it ended up becoming a write-up by Viarra’s chronicler, Zahnia:

(Art by @9musesandanoldmind)

A lot of Zahnia’s epigrams throughout First Empress are retrospective---an older (but still immortal child) Zahnia writing about and publishing histories a thousand years after Viarra’s reign. I don’t know if I’ll ever use this write-up for anything in the novel, but the idea of writing a mock history text about Queen Viarra, sometime after the novel(s) get published is kind of appealing.

It’s difficult for even those of us who knew her well to completely fathom exactly how powerful Empress Viarraluca truly was. She was a warlord whose armies conquered dozens of rival nations, slaughtered tens of thousands of enemies, and enslaved tens of thousands more. At the same time, she was a skilled warrior who slew dozens of enemies with spear and sword. And she was enough of an innovator that she helped introduce new tactics and soldier types beyond the traditional hoplite phalanx, even being the first to integrate crossbow archers into open-field combat.

Perhaps as a result of her martial achievements, many historians overlook or underestimate Viarra’s sexuality as a part of her power as empress. Where nobles and royals throughout all of history used sex as part of the political process, Viarra’s approach was unusual in that she only slept with women. It was a huge advantage in that so few rulers understood the full implications of what she was doing. Viarra had two wives by the time she became Empress over the Vestic Sea: Queen Aurella who ruled Pellastor and the other city-states in the southern parts of her empire; and General Inoria who ruled as satrap over the Illaran Confederacy’s former holdings. She married many other queens and princesses over her lifetime, placing them in charge of conquered kingdoms and client states. Meanwhile, the empress had dozens of royal concubines, mostly princesses sent as political liaisons from their respective nations. These marriages and liaisons created an unbreakably devoted network of women rulers and representatives through whom Viarra controlled her empire.

Additionally, Viarraluca had plenty of young noblewomen as ladies-in-waiting and harem slaves given as ‘gifts’ from various allies. Many allied monarchs and nobles offered their daughters, sisters, slaves, servants, and even wives to their empress’s entourage in order to get an ‘in’ into Viarra’s personal court, hoping to take advantage of her penchant for women bedfellows—mistakenly believing that they now had an ear into her personal dealings and a mouthpiece to whisper their political agenda to her.

The reality was both ironic and comical. This closeness instead allowed Viarra to use their women against them. She gave a stronger sense of purpose to many of these princesses and gentlewomen who previously hadn’t been expected to provide their families with more than a political marriage and offspring, as well as to these slave girls who’d faced a probable future as mere sex toys for some undeserving, uncaring master or mistress. Instead Empress Viarra protected, cared for, and made exquisite love to all of them, taking them into her confidence and treating them as valued lovers and allies.

Knowledge is indeed power, as philosophers claim, and Viarra collected information as easily and avidly as she collected lovers. Her many mistresses among the ruling class—knowingly or not—provided their queen with all manner of useful tidbits into their kingdom and family’s inner workings, often giving Empress Viarra advance warning of subterfuge or corruption amid her allies. The willing among Viarra’s harem women, meanwhile, were trained as courtesan spies and emissaries, charming or seducing information out of diplomats, merchant men and women, military officers, or even kings and queens. Men and women with a preference for women bedfellows will often say anything to impress a pretty girl, and Viarra’s loyal courtesans knew supremely well how to use this to their advantage.

Even her liaisons among the working classes provided Empress Viarra with information that other rulers might have missed. A night spent screwing the brains out of a farmwife, tavern wench, or shop proprietress could provide her majesty with information about the local economy and culture. And on top of boosting morale, laying with military officers, infantrywomen, or even camp-followers might inform the empress of logistical issues or discontent among the rank and file.

Womanly sex was indeed the currency across Viarra’s political and intelligence network, and its importance is all too often understated by otherwise open-minded historians. In this volume I will explore how these sexual connections with other women both informed and shaped the political and informational climate of Empress Viarra’s two-hundred-year reign…

—Excerpted from the introduction to Romancing the Throne: the Politics and Espionage of a Womanizing Empress, by Zahnia, the Chronicler

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Slavery in First Empress

Given the assumed Iron Age setting of First Empress to me it feels... disingenuous not to cover the topic of slavery within the story. I’ve studied plenty of ancient cultures and the only people I’m aware of who didn’t practice slavery was the followers of Zoroastrianism under the Persian Empire. Under the Ancient Greeks, off of whom I based Queen Viarra’s people, slaves were bought and sold and traded like any other commodity or resource, and indenturing oneself or one’s family was a common and legitimate form of favor exchange or debt settlement.

For the most part, I tend to treat slavery as something normal in First Empress, but I also try to show the consequences. One example from later in the story, Viarra’s hegemony comes under attack by a coalition of Gannic (Gaul) tribes from the Vedrian Mountains that form the northern border of her kingdom. Repelling the invaders requires a massive mobilization of hoplites from her own and her allies’ city-states. Such mobilization isn’t cheap, and a defensive campaign just doesn’t produce the spoils of war that come from an offensive campaign.