#Donald A Wollheim

Text

Vintage Paperback - Adventures On Other Planets by Donald A. Wollheim

Ace (1961)

#Paperback Art#Paperback Cover#Science Fiction#Donald A Wollheim#Adventures On Other Planets#Ace Books#Ace#1961#1960s#60s#Paperback#Paperbacks

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

ABMGW 215 Word's Best SF 5

Thema der Woche: Kurzgeschichten! Weil Kurzgeschichten gehen immer.

Bzw gehen gar nicht, wenn man kommerziell sicht, aber was ist dieser Podcast wenn nicht anti-kommerziell?

Wie dem auch sei, besprochen werden die Kurzgeschichten in der Sammlung “Worlds Best SF 5” von Donald A. Wollheim, die in dem Lesezirkel https://forum.sf-fan.de/viewtopic.php?t=11578 besprochen wurden.

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

#NowWatching ‘Mimic 3: Sentinel’ (2003) 🪳📸🧬

“𝚃𝚑𝚎𝚢 𝚊𝚍𝚊𝚙𝚝. 𝚃𝚑𝚊𝚝’𝚜 𝚑𝚘𝚠 𝚠𝚎 𝚖𝚊𝚍𝚎 𝚝𝚑𝚎𝚖. 𝚃𝚑𝚎𝚢 𝚍𝚘𝚗’𝚝 𝚑𝚊𝚟𝚎 𝚝𝚘 𝚋𝚎 𝚊𝚗𝚢 𝚋𝚒𝚐𝚐𝚎𝚛 𝚘𝚛 𝚜𝚝𝚛𝚘𝚗𝚐𝚎𝚛… 𝚜𝚘 𝚝𝚑𝚎𝚢 𝚐𝚘𝚝 𝚜𝚖𝚊𝚛𝚝𝚎𝚛.”

#now watching#horror#sci fi#mimic#mimic 3 sentinel#lance henriksen#DTV#direct to video#Karl Geary#alexis dziena#Keith d Robinson#amanda plummer#jt petty#Donald A Wollheim#bugs#Spotify

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The 1976 Annual World's Best SF, edited by Donald A. Wollheim (DAW Books, 1976).

Cover art: Chet Jezierski

#science fiction#anthology#book#The 1976 Annual World's Best SF#Donald A. Wollheim#Chet Jezierski#USA#1976

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

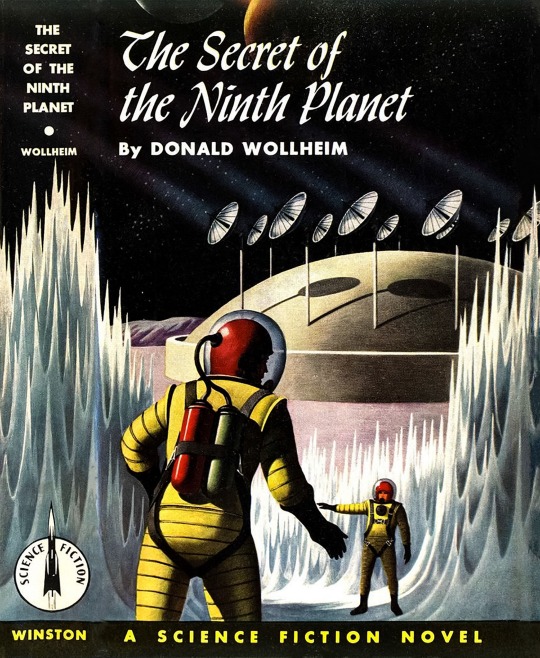

THE SECRET OF THE NINTH PLANET by Donald Wollheim. (Philadelphia/Toronto: Winston, 1959). Cover art by James Heugh.

‘When the power of the sun becomes noticeably diminished, young Burl Denning and his expedition take off in an anti-gravitational ship to discover the cause and its location. After a dizzying tour of all the planets, they realize that the trouble springs from Pluto, a belligerent planet which is trying to usurp the life-giving power which the sun gives earth. Making an alliance with the friendly Neptunians, the earth expedition represses the Plutonian plot and all ends well for the good folks of U.S.A.’ —Kirkus, 1959

#book blog#books#books books books#book cover#pulp art#science fiction#beautiful books#donald wollheim#pluto#anti gravity#james heugh

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

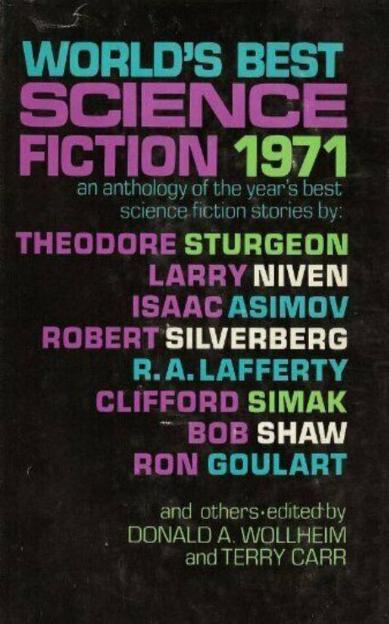

https://archive.org/details/worlds-best-science-fiction-wollheim-donald-a.-ed-carr-t

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Title: Mimic (1942)

Author: Donald A. Wollheim

Vote: 7/10

Interesting story that mixes horror with a veneer of science that serves as the foundation for an absurd but functional theory for the story. More than fear, I would say that it is a tale of mystery and strangeness. An insect that has learned to imitate man. An idea as absurd as it is interesting and which could be the basis for more than one story.

0 notes

Photo

DAW catalog January - April 1986

#daw books#daw#science fiction#scifi#fantasy#paperbacks#book collecting#book catalogue#donald wollheim#ephemera#1980s#1980's

0 notes

Note

For the last couple years I've been keeping a handwritten list of good horror stories I've read. I guess the most recommendable ones are The Music of Erich Zann by Lovecraft, The Stolen Body by Wells, Mimic by Wollheim, The Thing in the Weeds by Hodgson, Cyclops by Leiber, The Screaming Man by Beaumont, and The Open Window by Saki. I might type up and post the whole list on my blog after I've done some more reading (my list of things I still need to read grows much faster than the other list).

Including your other suggestions so I can tackle them all in one post.

I wasn't sure I was going to get to all these but I ended up being kinda knocked out by a nasty cold this week and had time to lay up in bed reading through all of them. Which was an absolute pleasure! Thank you for putting this list together. For fun I thought I'd do a mini-review of each story.

For context, I'm the kind of guy that's read probably every H. P. Lovecraft or Clark Ashton Smith story ever published. I had devoured most of Jules Verne and H. G. Wells by the time I was 14. What I'm trying to say is that I'm already a nerd pre-disposed to loving any Weird Fiction or early sci-fi/horror. If that kind of stuff isn't your speed, then adjust your expectations accordingly.

Also SPOILERS AHEAD for 50-100+ year old short stories.

"The Music of Erich Zann" - H. P. Lovecraft - 1921: This was always going to get a recommendation from me, I just enjoy Lovecraft too much. I'm glad I re-read it though, it had been a while and I think this might be one of my favorite of his stories now. The thing that stood out to me this time around was the exploration of the relationship between Zann and the anonymous protagonist. Feels uncharacteristic of a Lovecraft story to focus so much on the interactions between two human characters and it's done with a fair bit of depth. Bonus: no Lovecraftian racism in this story! Also check out this thrash/prog banger from the Mekong Delta album named after this story.

"The Stolen Body" - H. G. Wells - 1898: So when I opened up my copy of A Dream of Armageddon: The Complete Supernatural Tales (a misnomer it turns out, because it didn't contain the other Wells story on this list) I was surprised to find a bookmark exactly halfway through "The Stolen Body" from where I must've stopped the last time I tried reading this anthology over a decade ago. And I can understand why I would've stopped there because this story is kind of a slog. The premise is fine- a man severs his consciousness from his physical body in the course of an experiment in astral projection and is alarmed to find that when he attempts to return to corporeality another spirit has already taken possession of his frame. The problem is that this story is recounted twice- first from the perspective of a friend where, in spite of their incomplete information, it's pretty obvious what has transpired, and then a second time from the astral-projecting protagonist himself. In the protagonist's telling there's an interesting account of his journey through a kind of vapid hell where body-less spirits wander through eternity suffering of boredom and only able to interact with the physical world via mediums but the concept isn't explored in any depth and is recounted in a painfully "tell, don't show" manner. Can't say I recommend, but it's an interesting artifact of a time when late 19th century occultic beliefs showed up in sci-fi. Kind of like how a lot of 50s-70s sci-fi features psychics.

"Mimic" - Donald A Wollheim - 1942: My favorite story from the list. It's weird, compelling, and extremely brief. I won't summarize it because I think you should just read it. Surprised I hadn't heard of it before, especially since there's apparently a Guillermo Del Toro film adaptation of it? Also surprisingly difficult to track down the text. There are a few incomplete versions of it floating around but if you want the full story, I found it as part of this anthology on archive.org.

"The Thing in the Weeds" - William Hope Hodgson - 1913: - Before this, my only exposure to Hodgson had been "The House on the Borderland" (great story by the way), and reading the "The Thing in the Weeds" has me thinking I should dig a bit deeper into his bibliography. Conveys a sense of claustrophobia and anxiety that feels like classic "Weird Tales" fare while dealing with much lower stakes than unnameable cosmic beings. Maybe more horror stories should be set on the open sea...

"Cyclops" - Fritz Leiber - 1965: This is not a story, this is Leiber's idea for a cool vacuum-dwelling space creature dressed up as a story. Dialogue feels totally unnatural, characters are blank slates, tension is set at zero. But the creature is pretty darn cool and the story is very short. So if you want to just read about a neat alien, go ahead!

"The Howling Man" - Charles Beaumont - 1959: I had already seen the Twilight Zone adaptation of this story a while back so I knew the outline of the plot already, but that in no way diminished my joy in reading this. Beaumont's prose is highly engaging and contains a surprising amount of humor that I don't remember being present in the television version. The only real weak point is the ending. I think a bit more ambiguity over whether and to what the extent the Howling Man and the Abbott were lying to the protagonist would've demanded more introspection from the reader. The idea that releasing the Howling Man / Satan is the direct cause of WWII feels a little too simplistic and also depends on this weird assertion that the early Weimar Republic was experiencing an unprecedented era of peace and prosperity that I'm pretty sure doesn't hold up to historical scrutiny. Still highly recommend, a very fun read!

"The Open Window" - Saki / H. H. Munro - 1914: Less a horror story and more a... silly story? I don't know how to describe it other than it feels like the kind of thing you would have to read and analyze for a single high-school English period. Didn't really do anything for me but it's like a 5-minute read so check it out if you want. Does make me wish I could go on one of those "retreats to the countryside for my nerves" that turn-of-the-century English gentleman and ladies are always going on.

"In the Abyss" - H.G. Wells - 1896: A much better Wells story! And I was lucky enough to find this in the other print Wells anthology I own. (I have an addiction to bringing home old paperbacks I don't need but it's a cheap addiction and I don't have the heart to break it. Plus they're all on shelves and alphabetized so my wife can't get mad at me. Anyway, it's the shelves and shelf space that gets expensive...) It can be a little bit "gadget fiction-y" in its description of the submersible but overall it's well-paced with some good tension and a truly weird exploration of an underwater world. Recommend if you're looking for something outright odd or you like specifically underwater sci-fi. Don't recommend if you don't like thinking about the ways you might die in a submersible.

"The Stone Ship" - William Hope Hodgson - 1914: An interesting and definitely weird story, again about strange happenings on the open sea. Stretches the premise a bit too much, both in the actual length of the story and in my willingness to suspend my disbelief of the "scientific" explanation given at the end. I enjoyed it, but for a spookier and shorter take on a similar premise I'd recommend Lovecraft's "Dagon."

Anyway, thank you again @siryl for your recommendations, I had a blast reading through them!

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

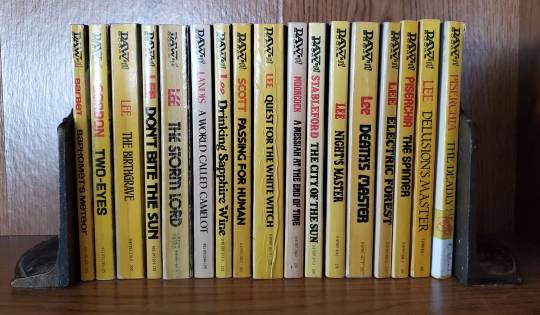

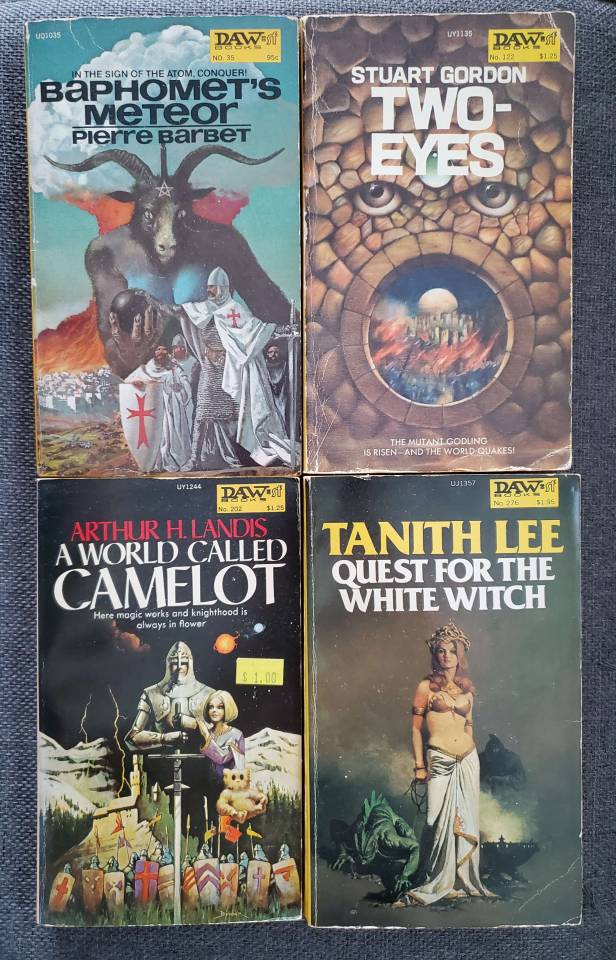

DAWstruck

A Quick Look at Sci-Fi/Fantasy Publisher DAW and My Desire for Cheap Entertainment

If you've ever been to an American used bookstore, flea market, etc., you probably recognize the distinctively uniform yellow (or faded-to-brown) spines of the DAW books pictured above.

From Wikipedia: "DAW Books is an American science fiction and fantasy publisher, founded by Donald A. Wollheim, along with his wife, Elsie B. Wollheim, following his departure from Ace Books in 1971. The company claims to be 'the first publishing company ever devoted exclusively to science fiction and fantasy.'"

Wollheim was active in sci-fi publishing and fandom circles; he published the Ursula LeGuin's first two books at Ace, and as a youth, he was kicked out of the New York Science Fiction League club for getting a group of unpaid authors together to sue writer/publisher/organizer Hugo Gernsback after they weren't paid for published stories:

"It grieves us to announce that we have found the first disloyalty in our organization… These members we expelled on June 12th. Their names are Donald A. Wollheim, John B. Michel, and William S. Sykora—three active fans who just got themselves onto the wrong road."

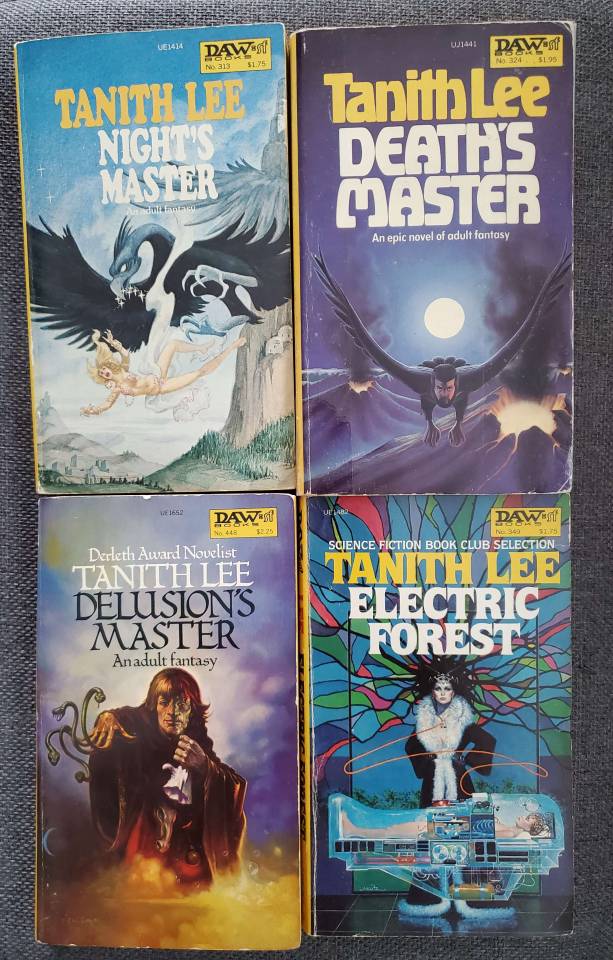

I've worked in bookstores and libraries for decades, and my eyes always glossed over the shelves full of yellow spines. But I started to reconsider after listening to Sean at SFUltra talk about Electric Forest by Tanith Lee. (Once you're equally convinced, go back his Patreon, which is literally my favorite criticism on the internet.)

I started devouring Lee's work. In my opinion, she outstrips most of the "greats" of that era of sci-fi. Her prose is awesome, her plots are great fun, and she's prolific across science fiction and fantasy. Had I been sleeping on DAW Books? Were they all this good?!

They are not all that good.

DAW Books books run the gamut of sci-fi and fantasy, from alternate histories to barbarian tales to postmodern reactions to the post-war West. And taken as an overview of the sci-fi field at that time, they reflect the good (Tanith Lee) and the bad (libertarian cryto-fascism, coercive sex freaks, tired cliches).

So why am I writing about them? Because they represent a type of publisher that, as far as I know, doesn't really exist anymore. They published authors who'd never been published before, and they printed straight to paperback.

I have no idea if anyone was making a living being published by DAW, but I assume this was a foot in the door for lots of these authors. And the books were so cheap! The one I have on hand was $1.25 in 1976. Adjusted for inflation, that's $6.93.

And listen, I read difficult books. I read literary fiction and academic histories and complicated, confusing cross-genre works. But I also like to read trash! I think everyone deserves to read some trash. But I want that trash to be cheap and easily accessible.

And with modern publishers focusing on established authors and Next Big Things, it's hard to find trash! And when you do find it, it's often dressed up to look like a Next Big Thing and priced accordingly.

Please give me more cheap trash.

And god, look at those covers. Again, I don't know if any painters were making a living by selling work to DAW, but they were definitely putting in the work. You got classic Frazetta horniness, you got '70s psychedelia, you got "what if the Bible was weirder?" classicism.

I want to decorate my walls with these.

The nice part is that they're mostly shorter than 200 pages, and I've never spent more than $5 on one of these, and I can usually find them even cheaper. So next time you're at a library sale and you see a faded yellow DAW spine, take a closer look.

Just stay away from Gor.

(DAW is still in business today, as a subsidiary of Astra House Publishing. I would say they occupy the same spheres as Tor: popular, readable, and usually left-of-center science fiction and fantasy. Such as The Forever Sea, a sapphic ecological fantasy book about sailors on a sea of plants. They cost, unfortunately, more than $7.)

8 notes

·

View notes

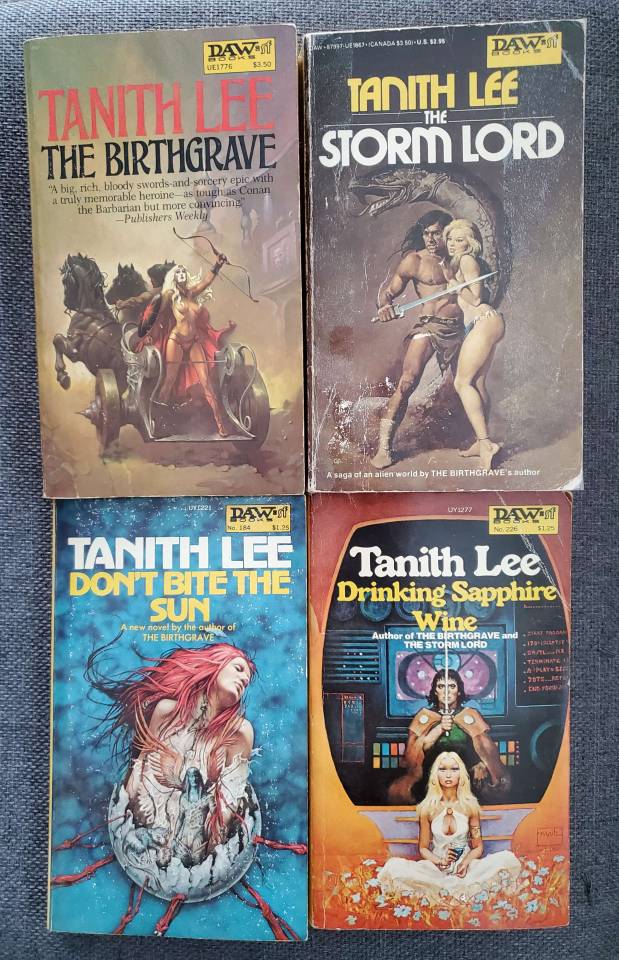

Photo

Vietnam War - Galaxy Science Fiction Magazine, June 1968

Sourced from: http://natsmusic.net/articles_galaxy_magazine_viet_nam_war.htm

Transcript Below

We the undersigned believe the United States must remain in Vietnam to fulfill its responsibilities to the people of that country.

Karen K. Anderson, Poul Anderson, Harry Bates, Lloyd Biggle Jr., J. F. Bone, Leigh Brackett, Marion Zimmer Bradley, Mario Brand, R. Bretnor, Frederic Brown, Doris Pitkin Buck, William R. Burkett Jr., Elinor Busby, F. M. Busby, John W. Campbell, Louis Charbonneau, Hal Clement, Compton Crook, Hank Davis, L. Sprague de Camp, Charles V. de Vet, William B. Ellern, Richard H. Eney, T. R. Fehrenbach, R. C. FitzPatrick, Daniel F. Galouye, Raymond Z. Gallun, Robert M. Green Jr., Frances T. Hall, Edmond Hamilton, Robert A. Heinlein, Joe L. Hensley, Paul G. Herkart, Dean C. Ing, Jay Kay Klein, David A. Kyle, R. A. Lafferty, Robert J. Leman, C. C. MacApp, Robert Mason, D. M. Melton, Norman Metcalf, P. Schuyler Miller, Sam Moskowitz, John Myers Myers, Larry Niven, Alan Nourse, Stuart Palmer, Gerald W. Page, Rachel Cosgrove Payes, Lawrence A. Perkins, Jerry E. Pournelle, Joe Poyer, E. Hoffmann Price, George W. Price, Alva Rogers, Fred Saberhagen, George O. Smith, W. E. Sprague, G. Harry Stine (Lee Correy), Dwight V. Swain, Thomas Burnett Swann, Albert Teichner, Theodore L. Thomas, Rena M. Vale, Jack Vance, Harl Vincent, Don Walsh Jr., Robert Moore Williams, Jack Williamson, Rosco E. Wright, Karl Würf.

We oppose the participation of the United States in the war in Vietnam.

Forrest J. Ackerman, Isaac Asimov, Peter S. Beagle, Jerome Bixby, James Blish, Anthony Boucher, Lyle G. Boyd, Ray Bradbury, Jonathan Brand, Stuart J. Byrne, Terry Carr, Carroll J. Clem, Ed M. Clinton, Theodore R. Cogswell, Arthur Jean Cox, Allan Danzig, Jon DeCles, Miriam Allen deFord, Samuel R. Delany, Lester del Rey, Philip K. Dick, Thomas M. Disch, Sonya Dorman, Larry Eisenberg, Harlan Ellison, Carol Emshwiller, Philip José Farmer, David E. Fisher, Ron Goulart, Joseph Green, Jim Harmon, Harry Harrison, H. H. Hollis, J. Hunter Holly, James D. Houston, Edward Jesby, Leo P. Kelley, Daniel Keyes, Virginia Kidd, Damon Knight, Allen Lang, March Laumer, Ursula K. LeGuin, Fritz Leiber, Irwin Lewis, A. M. Lightner, Robert A. W. Lowndes, Katherine MacLean, Barry Malzberg, Robert E. Margroff, Anne Marple, Ardrey Marshall, Bruce McAllister, Judith Merril, Robert P. Mills, Howard L. Morris, Kris Neville, Alexei Panshin, Emil Petaja, J. R. Pierce, Arthur Porges, Mack Reynolds, Gene Roddenberry, Joanna Russ, James Sallis, William Sambrot, Hans Stefan Santesson, J. W. Schutz, Robin Scott, Larry T. Shaw, John Shepley, T. L. Sherred, Robert Silverberg, Henry Slesar, Jerry Sohl, Norman Spinrad, Margaret St. Clair, Jacob Transue, Thurlow Weed, Kate Wilhelm, Richard Wilson, Donald A. Wollheim.

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

I thought being gay was against Islam? Sorry I don’t mean to offend I’m just confused :(

"'Repent, Harlequin!' Said the Ticktockman" is a science fiction short story by American writer Harlan Ellison published in 1965. It is nonlinear in that the narrative begins in the middle, then moves to the beginning, then the end, without the use of flashbacks. Stylistically, the story deliberately ignores many "rules of good writing", including a paragraph about jelly beans which is almost entirely one run-on sentence. First appearing in the science fiction magazine Galaxy in December 1965, it won the 1966 Hugo Award, the 1965 Nebula Award and the 2015 Prometheus Hall of Fame Award'

"Repent, Harlequin!' Said the Ticktockman" was written in 1965 in a single six-hour session as a submission to a Milford Writer's Workshop the following day.[1] A version of the story, read by Ellison, was recorded and issued on vinyl, but has long been out of print. The audio recording has since been reissued with other stories, by Blackstone Audio, under the title "The Voice From the Edge, Vol. 1". It was first collected in Ellison's Paingod and Other Delusions and has also appeared in several retrospective volumes of Ellison's work, including Alone Against Tomorrow, The Fantasies of Harlan Ellison, The Essential Ellison, Troublemakers and The Top of the Volcano. The story has been translated into numerous foreign languages.

The story opens with a passage from Civil Disobedience by Henry David Thoreau. The story is a satirical look at a dystopian future in which time is strictly regulated and everyone must do everything according to an extremely precise time schedule. In this future, being late is not merely an inconvenience, but also a crime; perpetrators are punished by having their lives shortened by an amount of time equal to the delay they have caused. These punishments are administered by the Master Timekeeper, nicknamed the "Ticktockman," who uses a device called a "cardioplate" to stop the heart of any violator who has lost all the remaining time in their life through repeated violations.

The story focuses on a man named Everett C. Marm who, disguised as the anarchical Harlequin, engages in whimsical rebellion against the Ticktockman. Everett is in a relationship with a girl named Pretty Alice, who is exasperated by the fact that he is never on time. The Harlequin disrupts the carefully kept schedule of his society with methods such as distracting factory workers from their tasks by showering them with thousands of multicolored jelly beans or simply using a bullhorn to publicly encourage people to ignore their schedules, forcing the Ticktockman to pull people off their normal jobs to hunt for him.

Eventually, the Harlequin is captured. The Ticktockman tells him that Pretty Alice has betrayed him, wanting to return to the punctual society everyone else lives in. The Harlequin sneers at the Ticktockman's command for him to repent.

The Ticktockman decides not to stop the Harlequin's heart, and instead sends him to a place called Coventry, where he is converted in a manner similar to how Winston Smith is converted in George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four. The brainwashed Harlequin reappears in public and announces that he was wrong before, and that it is always good to be on time.

At the end, one of the Ticktockman's subordinates tells the Ticktockman that he is three minutes behind schedule, a fact the Ticktockman scoffs at in disbelief.

Donald A. Wollheim and Terry Carr selected the story for the World's Best Science Fiction: 1966. When reviewing the collection, Algis Budrys faulted the story as a "primitive statement ... about [the] solidly acceptable idea [that] regimentation is bad".[2]

On 15 September 2011, Ellison filed a lawsuit in federal court in California, claiming that the plot of the 2011 film In Time was based on "Repent...". The suit, naming New Regency and director Andrew Niccol as well as a number of anonymous John Does, appears to base its claim on the similarity that both the completed film and Ellison's story concern a dystopian future in which people have a set amount of time to live which can be revoked, given certain pertaining circumstances by a recognized authority known as a Timekeeper. The suit initially demanded an injunction against the film's release,[3] though Ellison later altered his suit to instead ask for screen credit[4] before ultimately dropping the suit, with both sides releasing the following joint statement: "After seeing the film In Time, Harlan Ellison decided to voluntarily dismiss the Action. No payment or screen credit was promised or given to Harlan Ellison. The parties wish each other well, and have no further comment on the matter."[5]

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Farewell, Darkover - part 7

There's a real piece of sugar I found in the process of writing my Darkover reminiscences: MZB's own Darkover reminiscences, a retrospective she had penned down in 1980. Oh, darling, do tell. From the mouth of the beast herself. Time to get nasty.

First of all: When she writes in her own voice, she sounds mind-bogglingly similar to Stephenie Meyer, of all people. I cackled. MZB was a fucking Suethor. The same self-importance, false modesty, immaturity, the same condescension toward "cruel editors", the endless "oh, look, how special I am, how educated I am, how many important people I know!" It would be cute if I didn't wanna stomp on her face. Admittedly, it feels good to be able to talk about her like that - what's she gonna do, climb out of her misty sepulcher of oblivion and haunt me? It's a relief that she isn't someone I would have held in high regard, even without knowledge of her crimes. But let's look at some tidbits of this.

"I have referred to the Darkover books as "the series that just growed"."

So, I found zero hints at all that "growed" was ever the correct past tense for to grow. It's always been grew. Am I petty? You bet I am.

"A good part of the credit for encouraging the Darkover series to continue must go to Donald A. Wollheim"

I feel bad for the poor man, having his name attached to yours. I have great respect for Wollheim, and if I thought the Darkover books were way better written than the Avalon series, I have zero compunctions to credit your editor for it.

"with a sick husband and two very small children to support"

I wouldn't exactly call your husband sick. That implies an absence of responsibility, and I think he should very much be held responsible for his actions- oh, you were talking physical health. Carry on. And quit acting like the caring, loving mother; the sheer mention made me grab for a knife. I read what Moira wrote. I can't stand that hateful, homophobic fury, but I have a pretty good inkling who made her that way.

"when I protested, rather diffidently"

Aw, she wants us to think she has a shred of humility. Meanwhile, I think I should go poop on her grave.

She then goes on to tell us how she doesn't actually think her books in terms of series and prefers self-contained stories and thus didn't write Darkover in a way that one book had to rely on its predecessor to be understood (I hope she has to watch the entire MCU in hell ad nauseam), which is fine; just her overblown style of talking about herself is annoying to read. She also shoves in a quote about oatmeal that she doesn't bother to give credit for and I don't recognize; I suspect it's to make her look smart and to make those look dumb who are not in the know. Well, shove it.

Next, she gets really patronizing to fans who'd love them some consistency. Because she can't be arsed.

"Admittedly the inconsistencies are many. Some are minor, and they occurred simply because I have a very faulty memory with a self-correcting mechanism."

...

Bitch. I started to reconstruct the Comyn family trees and a timeline for Darkovan history at age 11. Surely you could have helped your faulty memory by writing things down??

More about how she doesn't like writing series, how she hates cliffhangers... my God, Bradley, this is a retrospective! You don't need to pad your word count here, too! Then a long story about how she had to give up on becoming a singer (which puts her hang-ups in the Darkover books about female singers constantly in peril of being considered better prostitutes in a very strange context; any complexes there, by chance? Gonna go with yes, as there are numerous female characters in her books that put everyone to awe with their singing in ways that more conventionally beautiful women couldn't with their looks), and how she always wrote, from childhood onward. Yeah, so did I. So did many. It's not that unusual. Almost everyone I know on tumblr wrote from childhood on.

"Well, in my middle teens, [...] I started to write fantasy novels with a framework of science fiction."

Heh. I also liked to call what I wrote in my teen years "novels". I assume it's nice when you get published and can feel verified in your blown-up presumptions.

"[Around age eleven, I did] an ambitious project called Ten Tales of the Ancients, which had a short story about a girl in ancient Rome, and one in ancient Greece, and one from an Arabian-nights kind of world, and then I ran out of ancient civilizations and gave up."

...Is that a shoutout to the American education system or what? Not sure if I would have gotten to ten civilizations at that age, but come on! Mayans? Ancient Egypt? Ancient China? Mesopotamia? I feel like her interest in ancient cultures may have been limited. Research is haaaaard, you guys!

Then a lot about the Fantasy and Sci-Fi writers that influenced her. I don't recognize most of the names, might look into those at some later point. The development of the whole Darkover idea via cannibalizing her older stories, that's fairly standard.

"During this time I also managed to read a few books on writing and began to get some foggy notions of what a plot was [...] I was beginning to learn how to plot, and how to tell a story"

By the time she wrote The Mists of Avalon, she had already forgotten it again.

...and I'm setting a cut here. My God, she's being wordy. Next up: her introduction to writing smut!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The first North American science fiction magazine, Amazing Stories, appeared in 1926. Since only a handful of science fiction writers existed in the United States at this time, all of them inferior to the best in Europe which had had a much longer tradition of science fiction, Amazing Stories had to make do with reprinting mostly old French, German, and British science fiction, and The War of the Worlds was once again published in August 1927 issue, starting a flood of American monster tales that was soon to deluge their science fiction. This is where the typical science fiction monster is born, rearing its slimy tentacles against an unsuspecting world, seemingly born only to drag the shrieking heroine round the universe with the square-jawed heros in hot pursuit. Wells and others had given some purpose to their monsters, whether satirical or critical or to explore different modes of existence, but the monsters that now deluged science fiction, at least in the United States, had no purpose whatsoever than offering cheap thrills.

Borrowing heavily from Western and Gothic tales, updating the aliens only by more tentacles and moving them out into space or letting them come to Earth from space to do their evil deeds (while, at the same time, noble Earth heroes murdered loathsome alien creatures on their home worlds), American science fiction magazines preached the gospel of uninhibited violence. Once again, as in the Gothic and simplistic Wild West tales, we have the externalization of evil, the pure black and white of fairy tales, only this time in a pseudo-scientific setting, vulgarizing all those works of science fiction from which the ideas came.

Until the advent of Amazing Stories, science fiction had been enjoying a good reputation as a useful tool for social criticism and also for its literary quality; this flood of pseudo-scientific poorly written tales, abounding in racism, violence, puerile sex and crude views of society, soon destroyed the last vestiges of that reputation in the English speaking world. Science fiction became ‘that Buck Rogers stuff.’ The mushroom men of Mars emerged triumphant from the carnage ... they became the dominant archetype of mid-20th American science fiction, and heavily influenced or reshaped completely the European, Latin American and Japanese genres as well.

The works that depicted extraterrestrials not as monsters, but as individual beings and definite personalities, not evil, but different were few and far between....Stanley G. Weinbaum’s debut A Martian Odyssey (1934) descended like a ton of bricks...One of my favourite stories of monsters, though not extraterrestrial, and certainly one of the most chilling examples, is a short story, Mimic (1942) from Donald A. Wollheim.... Wollheim’s remarkable insect - and the even stranger predators that feed upon it in the modern cites - is just a strange creature trying to survive, far removed from the kind of murderous aliens and monsters sadly common elsewhere...[a photo caption also praises the “non-bastardized first Japanese Godzilla film as another, surprisingly nuanced example - of the monster as punishment for human hubris.”]...[but even in the best works of this period] generally only humans are really worthy of respect, they steal and loot and kill with impunity, and only collaborating aliens are good aliens.

It is interesting to compare this attitude towards extraterrestrials, usually murderous and at best patronising, with developments in Europe, particularly the emergence of the new super power, the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union had not quite the American tradition of pulp magazines of the cheap Amazing Stories sort, nor the tradition of Wild West stories, from which the deluge of bad American science fiction writers got most of their inspiration. What the Soviet writers had inherited, and this was almost as suffocating, was the Utopian tradition from the Revolution, the demand that science fiction should be first didatic and educational and only secondly entertaining. This was in contrast to the demands of American magazine editors, that popular fiction should be entertaining, and nothing else.

Another fault in common with both the Soviet and the American example was the emphasis on vulgarized political ideas. In America science fiction of this period advocated free enterprise and Capitalism; the Soviet counterpart advocated Communism and collectivism. Extraterrestrial visitors in Soviet works of this time usually exemplified either the dangers of Capitalism or the blessings of Communism. And some of these hated Capitalist monsters were just as richly endowed with tentacles as their Western anti-Communist parallels. (The word ‘Communism’ was seldom used in American works when describing monster and alien civilizations, but the many descriptions of insect-like communities, blind obedience to leaders and de-individualized lives are very revealing.)

The hate expressed towards the aliens particularly in American science fiction, however, is very seldom found in Soviet science fiction of this time. Novels such as M. Prussak’s Gosti zemli (Guests of Earth), A. Volkov’s Chuzhiye (The Alien Ones), and I. A. Bobrichev-Pushkin’s Zaletnyy gost’ (The Guest Who Came Flying) are typical examples of aliens visiting Earth not as enemies but as strange guests, bearing tidings from sometimes incomprehensibly different worlds. One of my personal favourites is a later short story by Marietta Chudakova, Prostranstvo zhizhni (Life Space, 1969), describing a strange man who might or might not come from another world or another dimension or another time, whose life span is limited not by time but by space. As he grows older, the area in which he can move gets smaller and smaller until he finally dies when he inadvertently steps outside his life space. It is a strangely moving story, giving hints of a life enormously different from ours. [And earlier Lundwall praises Arkady and Boris Strugatskiy’s various works related to the alien and the Other...]

Apart from obvious political reasons for the abundance of horrible monsters attacking civilization during the ‘golden years’ of American science fiction up to the mid-1950s, the principle of which was attained with a particularly nasty film, Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), where monsters from outer space try to create a new world order in which everybody is equal but, of course, are finally defeated and exterminated by the hero and the military, one of the main reasons for the sorry state of things must be the fact that most American writers were reared on the local cheap fiction magazine tradition, which called for WASP heroes, villains easy to hate, and simple sexual interest, with lots of gore naturally. Science fiction in the United States faithfully followed the pulp magazine formula, as witness the greatest names and influences of the time - Edgar Rice Burroughs, E. E. Smith, Edmond Hamilton, and many others. Another issue was that, while some magazines were edited by people who might have loved science fiction, they had to bow to publishers who wanted nothing but fast profits [and] monsters and wild adventures and gore always sold...

The Soviet Union did not have these particular problems; instead, science fiction authors and editors had to keep a wary eye on the various politruk who thought that science fiction should try to solve technological problems of the near future, as well as presenting readers with ‘positive’ heroes. This was the time, according to a story by Soviet science fiction author Nikolai Tomas, when ‘fantasizing was allowed only within the limits of the Five-Year Plan for the national economy.’ American authors had blood-sucking publishers and over-worked editors to cope with; their Soviet counterparts had the Commissars. The difference - and here I am speaking as a citizen of a non-aligned nation which nevertheless was exposed to the various offerings of this time - was that the producers of American science fiction were exporting their junk. The ones in the Soviet Union and other socialist countries kept their junk for themselves. Only the best Soviet science fiction sneaked out, and those generally offered few monsters and very little preaching. Over the Atlantic, science fiction offered both in ample measure.

Starting in the early 1960s, this slowly began to change, with a new generation of urgently needed editors and writers producing works with a markedly changed attitude towards extraterrestrials and other monstrous beings...”

- Sam J. Lundwall, Science Fiction: An Illustrated History. New York: Grossett & Dunlap, 1977. p. 111-114.

[AL: Lundwall was a Swedish science fiction writer and critic, and his history, as old as it is, is still valuable because of his knowledge of Soviet, French, German, Latin American and Japanese science fiction of the time. His account is markedly different than the often parochial, self-aggrandizing and American-centric histories written in the English world at the same time. It was certainly eye-opening when I read this many years ago in middle school.]

#extraterrestial life#extraterrestrial#science fiction#sf#pulp fiction#science fiction magazines#pulp magazines#amazing stories#soviet union#soviet science fiction#cold war#coldwar#literary criticism#literary quote#critical review

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Pre-History of Fanfiction III: Birth of SF Fandom & the Mimeograph

Part 1

Part 2

Chapter 3: Birth of SF

The nativity of science fiction was happening concurrently with Sherlock-mania. Science Fiction as a genre was crystallized in 1926 when Amazing Stories magazine was first printed. Amazing Stories was a place to read science fiction to your heart’s content, as well as other speculative fiction. In each issue, fan letters were printed with names and addresses, allowing fans to communicate with each other. The SF fan base was rabid and creative, many fans of one generation became the writers and editors and the next.

A subculture was born along with the genre. Saler defines subcultures as a “social collection within the broader society whose members share certain symbols, traditions, values, customs, rituals, interest, and ways of doing things.” SF fandom surely checked these boxes. For example, let's look at ‘symbols.’ Even though one SF story can be radically different from another is character, setting, writing style, and so on, there are certain shorthands that a fan would know without more explanation like the words ‘transmitter’ or ‘teleporter beam.’ A SF would have an immediate conception of what that is while a member of broader society would not.

As for rituals and traditions, SF fans were organized in a way unseen in previous fandoms. The first conventions started popping up in the 30s. Here fans could see each other face to face, not just in the pages of Amazing Stories. Science Fiction fandom flourished in this time period, birthing hundreds of zines, conventions, and groups. But the fandom was not a monolith, SF subculture also started to splinter at this time leading to infighting and drama.

According to Alec Nevala-Lee, at the First World Science Convention held in New York City on July 2, 1939, fandom drama came to a head. The New Fandom was a group led by Big Name Fan Sam Moskowitz who wanted control over planning the Convention. His enemies were the Futurians, less a group and more of a random assortment of writers collected around Donald A. Wollheim. According to Mosckowitz, a handful of Furturians walked into the convection and demanded to pass out copies of a pamphlet. Moskowitz was ready to let them until he saw that the pamphlet referred to the planning committee as a “dictatorship.” Moskowitz banned them on the spot.

Futurians, on the other hand, said that the plan to keep them out of the convention was brewing for months before the pamphlet incident in what they called The Great Exclusion Act. Tension between the two groups might be attributed to the Futurians communist leanings. The New Fandom and the Futurians continue to struggle for Fandom supremacy, with the New Fandom organizing dozens of conventions and the Furtuians generating talented writers including Isaac Asimov and Virginia Kidd.

Feuding became a way of life for SF fandom, in the 60s a new fight started between the ‘new wave’ and the ‘old’. The old waved preferred printed stories like those found in Amazing Stories and favored speculative science rather than literary elements. The new wave on the other hand, often came to SF through TV shows and movies like The Outer Limits and The Planet of the Apes and enjoyed exploring character psychology. Linda Fleming quotes a fan reflecting on these changes saying: “The boundaries are much less clear today, however, because of the increase in size and because the literary SF culture nove overlaps with the larger, more commercialized Star Trek and comics fandoms.” Moving on from the drama though. Fans communicated not only in the pages of pulp magazines but also in handmade fanzines. These were DIY magazines usually printed in batches smaller than 500. They featured articles, original stories, fanfiction, art, as well as reviews of other zines (Zuber). Fandoms represented included SF in general as well as Fantasy, favoring Tolkein’s work and the Lovecraft universe. But what changed? What allowed fans to communicate with each other straight up rather than through a middle man to the point where they were foregoing publishers and making their own magazines?

Sidebar 1: The Mimeo

Before we get to the next chapter, we have to talk about the technological development that made fanzines possible. Though printing had been around for over a century, it wasn’t possible to do cheaply or easily at home. The mimeograph changed all this. The mimeograph was created in the late 19th century but it became widespread in the 1950s. It retailed for around $500 to $1000 in today’s money which made it a somewhat inexpensive way to print at home. It's easy and uncomplicated to work, too, with a hand crank first and then later a motorized drum. It was favored by schools and businesses, giving access to people who possibly couldn’t afford their own. “Mimeo” was used as a catchall for many copying devices but the true mimeo worked by inking a series of stencils.

The mimeo was used by writers and artists who couldn’t--or didn’t want to--be published by the big houses. This was the beginning of the DIY movement, when writers, artists, and musicians avoided middlemen by creating and distributing their own work.

#fanfiction#history of fanfiction#fan fiction#science fiction#zines#fanzines#tolkein#sf#sci fi#fan culture#fandom history#fandom studies#mimeo#mimeograph

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

‘The 1989 Annual World’s Best SF’ edited by Donald Wollheim, cover art by Richard Powers. via CoolSciFiCovers

5 notes

·

View notes