#Delian League

Text

Flags of the Athenian Empire

These are the flags of the Athenian Empire. I couldn’t decide which I liked better, so I went with both of them. They come from a world where Athens won the Peloponnesian War. Following the defeat of Sparta, the Delian League was expanded to include the Greek colonies in Italy, the city-states in Anatolia and all of Greece. All of this new territory meant more treasure for Athens' coffers. Athens used much of this new-found wealth to expand its military and navy. The unification of the Greek city-states meant that the Macedonian Conquest never occurred, and Alexander the Great never came to power. Though it was still known as the Delian League, in reality, all of the city-states knew that they were now part of the Athenian Empire.

The threat of Persia was an ever-looming concern. Athens funded many rebellions against Persia in regions such as Egypt and the Levant. Eventually, Athens declared war on the Persian Empire and conquered it in short order. However, most of the territory was lost within a few generations. Athens also went on to conquer Carthage, the fledgling Roman Republic and expanded its territory into Gaul. Athens also expanded into Hispania and the British Isles, but never for too long.

Following this series of conquest Athens began to focus more intellectualism and the acquisition of knowledge. Many libraries and centers of learning were founded across the Athenian Empire. The Athenian Empire never truly fell, but over the years it did lose territory; at its smallest, it was comprised of Greece and Anatolia. However, Greek influence on language, art and culture is felt throughout its former empire and the world at large. In many ways, the Athenian Empire can be seen as the Western world's equivalent of China in terms of influence and culture.

The flags feature an owl clutching an olive branch, symbols of Athens patron goddess Athena. The colors of the flags are black and orange in reference to Ancient Greek pottery. The black on the first flag is also a reference to the black sails of Theseus, mythical king of Athens.

Link to the original flags on my blog: http://drakoniandgriffalco.blogspot.com/2017/09/flags-of-athenian-empire.html?m=1

#alternate history#flag#flags#alternate history flag#alternate history flags#vexillology#Athens#Athenian Empire#Flags of the Athenian Empire#Greece#ancient greeks#ancient greece#peloponnesian war#Delian League#athens greece

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Greek and Roman power structures are why I hesitate to call most things people call "queer" about their societies queer on the internet or like when people ask the stupid question of "Do you think theyd be into bdsm?" I'm like do you WANT that kind of inherently bad for consent society to be into bdsm???

Putting my thoughts under a read more cause its lengthy and something that I've wanted to talk about for a while now!

Like I'm sure queer relationships with like 1) no weird power dynamic and 2) pedastry existed in these societies, we have always existed, but it would not have been easy. They most likely still would have had to have played the part of a man who followed the rule and roles of what a MAN had to to be considered a man on the surface of society, because if they didnt, they would've been ridiculed and seen as lesser men. A big example of one such rule in the sexual realm is men could not and should not be penetrated; penetration was the domain of those lesser than men, if you were a man who liked being penetrated you were a fucking joke. They would've even been called perverse for not having a weird power dynamic in their romantic or sexual relationship with other men.

Slaves, young boys, slave boys, etc were basically equivalent to women in classical Greek society: they are those below the status of men and thus suitable objects of ones sexual desires. Like think about how fucked up that is??? And on top of that courting was also fundamentally tied to this perception of these groups of lesser status and required guidelines, so seeming genuinely invested and lovesick in ones relationship to these lesser beings was also seen as ridiculous.

Like it was all seen as taboo for the WRONG reasons. They'd would be so confused, ridicule you, or frankly be pissed if you pointed out how awful the inherit vacuum for consent these dynamics are and rife for abuse of power these relationships would have been to begin with because you're basically questioning the standards of classical Greek masculinity.

And I also wish we discussed more how the classical periods in Greece and Rome played a part in contemporary homophobia. Like it's not all 100% the result of Christianity moving into these societies, but more so a chain with Christianity being the biggest domino to fall at the end. Rome in particular was influenced by these sexual and social ideas of class and sexual dynamics in Greece, so the undercurrent of homophobia inherit to those ideas made Christianity all the more appealing for aligning with those already establied ideas.

In the end sex was basically used the same way everything else was to men in classical Greek and Roman society: its about power, gaining power, flexing that power and through this, raising ones status in these societies. It left very little room for partnerships of equals and the little room that was there was probably incredibly suffocating for anyone who didn't want to abide by these rules and standards of masculinity or others of which they were expected to.

#like i think scholastically we really do a diservce to the honest history of both of these periods#by describing them with contemporary language of homosexuality#cause like idk to me society worked so differently that it was its own thing and requires its own language#which is why i think unfortunately gay people especially latch on to this fantasy of classical greece and rome#oh and also i will admit when we usually discuss classical Greece its usually under the banner of ancient Athens#other greek districts had like different rules and shit but if is fair to say generalising through Athens#is safe cause well Athens had a lot of influences on other city states in classical greece#you know the whole delian league and shit...#ok thats soo long its just a lot of info is linked im shutting up now aoskskdks

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

A significant portion of the western "left", especially online, are shocked or even offended that global south people not only know about politics in the united states but have opinions about them. They think that, because they live in the first world, that that's all there is and thus events beyond the border rarely register as a blip lest it got blown into the limelight like with Palestine. They project their own ignorance onto the global south.

But of course the global south would be intimately familiar with the politics of the first world! What gets decided in washington or brussels or london or paris or berlin gets exported the world over. The Palestinian cars about the arms deals of the united states. The Nigerian cares about the "strategic resource" policies of france. The people of the global south are at the whims of the worst policies of the imperial core but who have absolutely no say in it. Like the delian league, the slave colonies most definitely had a stake in the machinations of athens but ehoch they could neither vote nor represent themselves.

1K notes

·

View notes

Note

Archaeology student Venture trying hard to charm the cute literature major girl that sits in their medieval studies classes. Endless rambling about ancient cultures and books to try and win you over. Can barely focus on the lecture when you're around. Yeah. College Venture <3

I love this concept gangalang! Im not in college (yet) so I don't have a first hand experience of what college is like, but I'll always try my best <3

I always headcanon that Sloan does enjoy reading the classics...

(wrote this in class)

You settle down in a seat in your medieval studies classroom, sitting in the middle section of the lecture hall. Not many people populated the classroom, just a few groups of people talking amongst themselves and getting settled down to take notes.

The professor started her lecture and you started people watching. Why did you have to choose this class...

You had a good view of most of the other students because everyone wanted to be close to the professor to hear her speak and record, but there was a person sitting 5 chairs down from you, sitting ramrod straight and trying to look nonchalant. Odd.

The professor mentioned something about a project and you snapped your attention back to her.

"... you will be studying the architecture of the Romanesque building style and you must work with another person for full credit..."

Oh now we have to work with another person. Great. You reach down into your bag to grab your laptop and supplies when—

"You know that even though we call them the Byzantines, they called themselves Romans?"

You jump a little bit and look up to see a person with wild curls, a chipped tooth and a eyebrow piercing. The same person sitting weirdly during the lecture. They're now sitting eerily close to you.

You feel awkward just staring at them without saying anything.

"If they called themselves Romans then why do we call them Byzantines?"

They seem shocked you asked a replied back and start stuttering.

"Well- because their capital city was called Byzantine before it was Constantinople and after that it was Istanbul after the Ottoman turks took it over..."

Now that you've gotten a good look at them, they're so handsome.. you catch a glimpse of a neck tattoo before they put their hand around their neck, rubbing it slightly.

"Sorry, I was talking too much— oh wait! Where's my manners, my name is Sloan– what's yours?"

You tell them your name and they seem to melt a little bit. You talk for a little bit more about the Byzantines and the topic of the project comes up again.

"You seem like you know a lot about history, Sloan. Do you want to work together?"

They freeze. They were about to pick up a piece of paper and they look like they were caught like a deer in headlights.

"Um."

Oh crap.

"We don't have to if you don't want to—"

"NO! No I want to work with you, like how the Delian league and the Peloponnesian league combined forces to defeat the Persians!!"

They're blushing and waving their hands around.

"Um- I'm free later this week, but I have to get to my Geology class now– this is my number, have a great day ill see you later bye!!"

They essentially sprint away after basically throwing a scrap of paper with scratchy numbers written on it. You see them run to a thin man with patchy blonde hair with ash and grime on his shirt, them both talking excitedly and you hear Sloan proclaim their "successful first blow against the walls of Constaninople."

Whatever. If there's something you love most, it's history nerds.

-+-

I didn't wanna make this too long but I actually love this idea so here's some headcanons that I wish I could have fit in here ;3

- sloan would give you crystals meant to increase focus

- sloan would ALSO give you crystals because they "thought you would like them" but they're just all those affection stones like rose quartz.

- omg

- sloan gives you necklace/bracelet with those kinds of stones

- Now that you're working together they still sit up very straight at the beginning of class, but they progressively get more relaxed as they talk to you

- before, they wouldn't dare to get within a normal line of sight with you

- hence sitting 5 chairs away

- junkrat cameo. Had to do it

- junkrat got so fed up with Sloan

- "Sloan, if you don't get your big pants on and talk to them I'm blowing up your fossil collection."

- "you wouldn't dare. And besides, they would hate me..."

- "I wouldn't touch your fossils... but Mako might."

- that was the final straw for them LMAO

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marble bust of the great Athenian general, orator, and statesman Pericles (ca. 495-429 BCE), shown here wearing a Corinthian helmet. Pericles is credited by many historians, notably Thucydides, with guiding 5th century BCE Athens to its peak of greatness; among his achievements were the ambitious building program on the Parthenon and the conversion of the Delian League, originally formed to combat the Persians, into a tribute-paying Athenian empire. His reputation was not, however, unblemished. His political opponents accused him of aiming at tyranny, while his enforcement of the Megarian Decree--which barred Sparta's ally Megara from all Athenian harbors and was effectively an act of economic warfare--may have been the proximate cause of the Peloponnesian War. His death from plague plunged Athens into crisis and led to a succession of populist leaders such as Cleon and Hyperbolus, whose far more aggressive foreign policy ultimately proved disastrous for Athens. Though the city would survive and even make a second attempt at empire-building, it never regained the unchallenged supremacy it had enjoyed in the Periclean period.

Roman copy of uncertain date after a lost Greek original. Now in the Museo Chiaramonti, Vatican City.

#classics#tagamemnon#Ancient Greece#Classical Greece#ancient history#Greek history#Ancient Greek history#Pericles#Perikles#art#art history#ancient art#Greek art#Ancient Greek art#Classical Greek art#sculpture#portrait sculpture#portrait bust#marble#stonework#carving#Museo Chiaramonti#Vatican Museums

191 notes

·

View notes

Note

also I'm really sorry if it's too personal a question but what did you study in college? you're amazing at writing diplomacy and the world building seems like a gift of reading many history books. any particular research you think would be extremely interesting for your readers?

No, not too personal a question, and I'm very happy to ramble about this! 😊

The short answer is: I studied Classics at university. The longer answer (related to how it impacts on my writing) I have popped behind the cut, because honestly your question really got me thinking, and this ended up being very long!

So as I said, I studied Classics. I was lucky enough to be accepted to an absolutely brilliant university, with a phenomenal Classics department and amazing professors. They encouraged you to pursue the subject areas that interested you, and the degree was a fantastic way to narrow down a specialism from a broad area, to your dedicated topics, with a view to you becoming a potential expert in that area.

In short: I started off with Greeks, Romans and Persians, and by my third year I was specialising in ancient Greece, with a specific focus on the Classical and Hellenistic periods (with a particular interest in Alexander the Great). (I was also having a love affair with the Bronze Age on the side, because you can pry Homer from my ravenous, sticky fingers.)

When I read your question, I must admit I had a lightbulb moment, where I went 'Oh yeah! That's where all the politicking comes from!', because I honestly hadn't stopped to actually think about the influences my studies may - or may not - have had on my fiction. And then I realised that, well, they most definitely have. 😂

I think the easiest example of this is in IB, with Lenian culture. I am very conscious that I took an idea (I thought it would be funny to have Sirens - traditionally depicted as scantily-clad temptresses - and make them the most buttoned-up, repressed, hell-bent-on-social-etiquette species), and then I ran with it. It's where a lot of Lenian culture comes from: it doesn't depict Ancient Greece, but it does borrow from its language (mostly made up to sound like Greek, with some notable exceptions), and also, I think some of the mindset. Lenians are culturally Not That Bothered About Killing, especially when it comes to politics, and this is, well, a pretty obvious theme that happens in politics (in Athens, Sparta, Macedonia and beyond) in the 5th, 4th and 3rd centuries BCE, along with all the backstabbing, swapping sides and power grabs.

More widely, I think the galactic politics in my writing may come a little bit from the fact that this period of history deals with a lot of states politicking and warring with one another (things like the Delian League definitely sit at the back of my mind most of the time), so I do definitely enjoy thinking about how smaller, personal things can start to become major political problems (and of course the impact that has on the delicate balance of peace and power).

Upon reflection, I also think Samiel is... unconsciously a little bit of a play on Homeric standards for heroes. He's clever, he's brutal, but he feels very, very deeply. This was entirely unintentional, but the more I think about it, the more I'm going to have to go back at some point and try and pick him apart a bit more.

Jumping back to my studies, my specialism got narrowed down further when I hit my undergrad dissertation, focused on the library of Alexandria, then got kind of overtaken by representations of Alexander the Great in literature. My Master's dissertation ended up exploring a discussion on sources that spoke of Alexander as a representation of Zeus-Ammon. (I'll pause here to point out that this is another one of those moments where the beginnings of P2P entered my head - because we have some tenuous links to Alexander as a potential representation of forces of chaos/the Antichrist, and my brain clearly went 'Hmm...' and filed this away for safekeeping. 😅)

And then finally the start of my PhD was on Alexander the Great versus his mythical representations in the 'original' (I say 'original' but I mean 'the only ones we have left - i.e. Roman') sources. This was a deep-dive look at Alexander as an Homeric hero (he's constantly linked/compared to Achilles, but how much of that came from Alexander himself, and how much of it came from later comparisons?), and as Heracles and Dionysus. All of which is a long-winded way of saying: I also get very excited about public mythical representations of political figures, versus what they're actually like.

In terms of things that might interest you, I think it depends on what you're after. However, some fun places to start may be translated sources, or some accessible works about the time period.

So a quick (and not at all comprehensive) couple of suggestions:

Plutarch's The Age of Alexander

Alexander the Great (Robin Lane Fox) - by no means a perfect biography, but it is very readable

Who's Who in the Age of Alexander the Great (Waldemar Heckel) - a reference book, but such a good one - thoroughly comprehensive work covering pretty much anyone mentioned in relation to Alexander and his successors, and where they appear in the sources

The Iliad (Homer) - find an enjoyable translation because this is just... I adore it, it is such a perfect, wonderful microcosm of war and the Homeric world and it's delicious

The Oxford History of Greece and the Hellenistic World (John Boardman) - a great overview of the time period, a little old now but such an interesting read

Professor Jeanne Reames has written and compiled brilliant work on Macedonia over the years (and specifically to my interests, on Hephaistion) - she's got some great articles online for free and some amazing resources

Professor Mary Beard writes wonderful, very accessible books on the Romans, so if your interests swerve more in that direction, she is a wonderful starting point

This was such an interesting question, thank you!

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

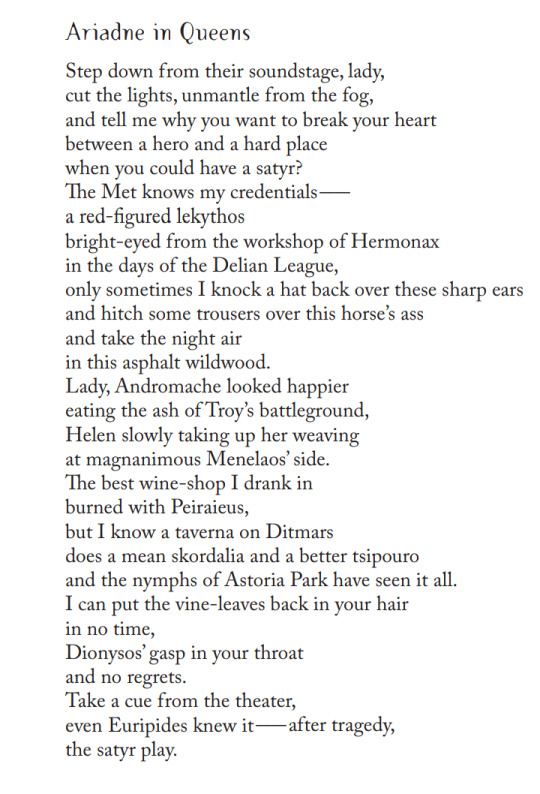

Sonya Taaffe - id under cut

Ariadne in Queens

Step down from their soundstage, lady,

cut the lights, unmantle from the fog,

and tell me why you want to break your heart

between a hero and a hard place

when you could have a satyr?

The Met knows my credentials——

a red-figured lekythos

bright-eyed from the workshop of Hermonax

in the days of the Delian League,

only sometimes I knock a hat back over these sharp ears

and hitch some trousers over this horse’s ass

and take the night air

in this asphalt wildwood.

Lady, Andromache looked happier

eating the ash of Troy’s battleground,

Helen slowly taking up her weaving

at magnanimous Menelaos’ side.

The best wine-shop I drank in

burned with Peiraieus,

but I know a taverna on Ditmars

does a mean skordalia and a better tsipouro

and the nymphs of Astoria Park have seen it all.

I can put the vine-leaves back in your hair

in no time,

Dionysos’ gasp in your throat

and no regrets.

Take a cue from the theater,

even Euripides knew it——after tragedy,

the satyr play.

482 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think the Peloponnesian War is so fucking funny because Sparta (who was famous for their army) beat Athens in naval combat. Athens. Whose navy was funded by the Delian League and the Laurion silver mines. Lysander really looked at the most powerful naval force in the Mediterranean and said “fuck you”. Fucking classic.

69 notes

·

View notes

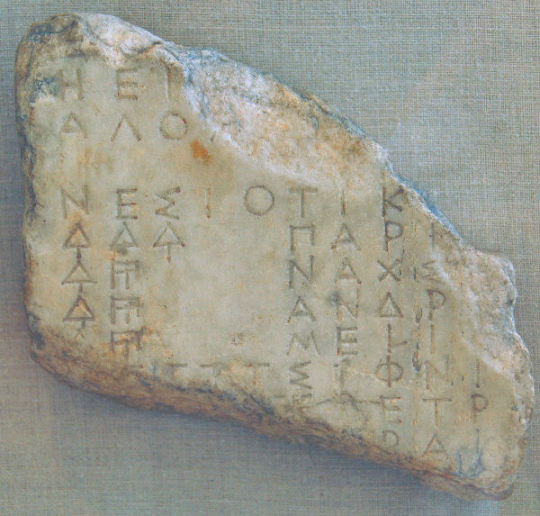

Photo

A fragment from the Athenian tribute list of 425 BCE. These lists catalogued the cities that paid taxes to the Athens-led Delian League -- which by this point Athens was running as an empire. Much of the money sent in by allies was used to build Athens’ magnificent architecture.

{WHF} {Ko-Fi} {Medium}

126 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi there! so i need some advice. so we (me and some buddies) got done fighting persia a while ago and i set up this little league during the war called the delian league right? and all my buddies pay money into the league treasury. and i’m just wondering like… should i use the money for like, defending greece? or should i just built like a cool new temple on the acropolis lol

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thesis: Empire as both a verb and a noun is defined by that which resists it

I've spent my entire historical career looking for a single definition of Empire that includes the Delian League, the Mughals, and the United States and this is the closest I've gotten so far.

#thinking thoughts and taking notes#I recommend Moon-Ho Jung's Menace to Empire#its dense as hell and suffers from many of the common problems of historical writing but he has a lot of very good and interesting ideas#not to be teleological on main

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

gritting my teeth everytime I loudly support the return of the elgin marbles because I know the greek government is also using them as a foundation for a national cultural identity divorced from the original context not unlike the british (the greek government has had more than a few unkind moments to their own citizens in their efforts to do so if you can believe it as well) but there simply isn't an angle I can justify not supporting it from.

I hate all arguments for british custody based on their angloexceptionalism (our museum is Global, we're somewhere accessible to the whole world! the Greeks can't take care of them so they should stay in our custody because we're the responsible Adults of the world!), I reject absolutely the slippery slope argument (in fact I WANT to see a landslide of repatriated artifacts destroying the accumulated power of ancient imperialist museum institutions), and I think refusing to have an opinion on anarchist principles ultimately supports the inertia of british custody.

it's actually kind of funny. There's are relatively few current cases for art repatriation that doesn't on some level appeal to a national identity divorced from the original context of the art. It involves flattening the diverse cultures and societies which once inhabited a modern day country into the "history of Country". even the name... repatriation. patria. pater. father as in fatherland. there's a hierarchical notion baked into the language - that of the father country demanding obedience and fidelity of his children peoples as he leads the homogenous family. When the Parthenon was crafted, it was a symbol of the Delian League's overwhelming wealth and power, a symbol of something so oppressive that what we now consider Greece tore itself apart over, tall marble structures on the city's highest hill decked to the gills in carved marble and gold paid for by demanded tributes. One polis over all the others, it might have said. Now it's a crumbling ruin and would-be symbol of national unity for a state crafted by 19th century european monarchies to appeal to that pernicious fetish for the Classics. There's some irony there, right?

#if the prompt is 'what should be done about the elgin marbles' do you think that#'they should be returned BUT greece and great britain (bare minimum) need to be dissolved as states' is an acceptable answer#for like a dumb undergraduate essay.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The U.S. alliance system: there’s never been anything quite like it. Ancient Athens helmed the Delian League. German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck skillfully played Europe’s alliance game in the nineteenth century. The coalitions that won the world wars were nearly global in scope. But no peacetime alliance network has been so expansive, enduring, and effective as the one Washington has led since World War II. The U.S. alliance system has pacified what once were killing fields; it has forged a balance of power that favors the democracies.

Yet the existence—and achievements—of that system may actually make it harder for Americans to understand the challenge they now confront. Across the Eurasian landmass, Washington’s enemies are joining hands. China and Russia have a “no-limits” strategic partnership. Iran and Russia are enhancing a military relationship that U.S. officials deem a “profound threat” to the “whole world.” Illiberal friendships between Moscow and Pyongyang, and Beijing and Tehran, are flourishing. Americans may wonder if these interlocking relationships will someday add up to a formal alliance of U.S. enemies—the mirror image of the institutions Washington itself leads. Whatever the answer, it’s the wrong question to ask.

When Americans think of alliances, they usually think of their own alliances—formal, highly institutionalized relationships among countries that are linked by binding security guarantees as well as genuine friendship and trust. But alliances, as history reminds us, can serve many purposes and take many forms.

Some alliances are nothing more than nonaggression pacts that allow predators to devour their prey rather than devouring one another. Some alliances are military-technological partnerships in which countries build and share the capabilities they need to shatter the status quo. Some of the world’s most destructive alliances featured little coordination and even less affection: they were simply rough agreements to assail the existing order from all sides. Alliances can be secret or overt, formal or informal. They can be devoted to preserving the peace or abetting aggression. An alliance is merely a combination of states that seeks shared objectives. And relationships that seemed far less impressive than today’s U.S. alliances have caused geopolitical earthquakes in the past.

That’s the key to understanding the relationships among U.S. antagonists today. These relationships may be ambiguous and ambivalent. They may lack formal defense guarantees. But they still augment the military power revisionist states can muster and reduce the strategic isolation those countries might otherwise face. They intensify pressure on an imperiled international system by helping their members contest U.S. power on many fronts at once. And were U.S. antagonists to expand their cooperation in the future—by sharing more advanced defense technology or collaborating more extensively in crisis or conflict—they could upset the global equilibrium in even more disturbing ways. The United States may never face a single, full-fledged league of villains. But it wouldn’t take an illiberal, revisionist version of NATO to cause an overstretched superpower fits.

AMERICA’S EXCEPTIONAL ALLIANCES

Alliances are shaped by their circumstances, and U.S. alliances—namely, NATO and Washington’s Indo-Pacific alliances—are products of the early Cold War. Back then, the United States faced the dual dilemma of containing the Soviet Union and suppressing the tensions that had twice ripped the Western world apart. The contours of U.S. alliances have always reflected these founding facts.

For one thing, U.S. alliances are defensive pactsmeant to prevent aggression, not perpetrate it. Washington originally structured its alliances so their members could not use them as vehicles for territorial revanchism; when American alliances have expanded, they have done so with the consent of new members. U.S. alliances are also nuclear alliances: since the only way a distant superpower could check the Red Army was to threaten nuclear escalation, issues of nuclear strategy have dominated alliance politics from the outset. For related reasons, U.S. alliances are asymmetric. Washington has long shouldered an unequal share of the military burden, especially on nuclear matters, to avoid a scenario in which countries such as Germany or Japan might destabilize their regions—and terrify their former victims—by building full-spectrum defense capabilities of their own.

This point notwithstanding, U.S. alliances are deeply institutionalized: they feature remarkable cooperation and interoperability developed through decades of training to fight as a team. U.S. alliances are also democratic; they have survived for so long because their foremost members have a shared, enduring stake in preserving a world safe for liberalism. Finally, U.S. alliances aresanctified in written treaties and public pledges of commitment. That’s natural, because democracies cannot easily make secret treaties. It’s also vital because the beating heart of every U.S. alliance is Washington’s promise to aid its friends if they are attacked.

These features have made U.S. alliances tremendously attractive, effective, and stabilizing—which is why Europe and East Asia have been so peaceful since World War II and why Washington has more trouble keeping prospective members out than luring them in. But they also influence Americans’ views of alliances in ways that aren’t always helpful in understanding the modern world. After all, there is no rule that alliances must look like Washington’s—and some of history’s most pernicious alliances have not.

THE PREDATORS’ PACTS

Today isn’t the first time the world’s most aggressive states have made common cause. During the mid-twentieth century, an array of revisionist powers forged malign combinations to aid their serial assaults on the status quo.

In 1922, a still democratic Weimar Germany and the Soviet Union signed the Rapallo Pact, which promoted cooperation between these two losers of World War I. Between 1936 and 1940, fascist Italy, Nazi Germany, and imperial Japan inked agreements culminating in the Tripartite Pact, a loose alliance committed to achieving a totalitarian “new order of things” around the world. Along the way, Berlin and Moscow sealed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, a nonaggression treaty that included protocols on trade and the division of Eastern Europe. And after a hot war gave way to the Cold War, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin and Chinese leader Mao Zedong negotiated a Sino-Soviet alliance that linked the two communist giants in their fight against the capitalist world.

These were some of history’s most dysfunctional, ill-fated partnerships. In several cases, they were temporary truces between deadly rivals. In no case was there anything like the deep cooperation and strategic sympathy that distinguish U.S. alliances today. This isn’t surprising: regimes as vicious and ambitious as Adolf Hitler’s Germany, Stalin’s Soviet Union, and Mao’s China shared little more than a desire to turn the world on its head. Yet this history is valuable because it shows how even the most transitory, tension-ridden partnerships can rupture the existing order, generating strong pressures in support of aggressive designs.

The Rapallo Pact was no full-fledged alliance: it was principally a détente in Eastern Europe, the region into which both Germany and the Soviet Union hoped to eventually expand. But the pact and the secret protocols that accompanied it turbocharged disruptive military innovation by international outcasts—Germany especially. At sites hidden within the Soviet interior, Germany began developing the tanks and planes the Treaty of Versailles had denied it, as well as operational concepts it would later use to great effect. This covert partnership collapsed when Hitler took power, but not before giving him a vital, deadly head start in Europe’s race to rearm in the 1930s.

Other revisionist pacts lowered the costs of aggression by reducing the isolation its perpetrators might otherwise have faced. The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact—the “new Rapallo” Hitler signed with Stalin on the eve of World War II—lasted less than two years. But during that period, it shielded Germany from the effects of the British blockade by giving it access to Soviet foodstuffs, minerals, and energy and by providing a conduit through which Hitler could access Japan’s growing empire in Asia. Molotov-Ribbentrop enabled Germany’s rampage through Europe by making much of Eurasia an economic hinterland for Berlin.

Molotov-Ribbentrop also enabled violent aggrandizement on one front by taming tensions on others; in this sense, it was a nonaggression treaty that encouraged world-shattering aggression. The pact set off World War II in Europe by assuring Hitler that he could fight Poland and the Western democracies without interference from the Soviet Union—and by setting off Soviet land grabs from Finland to Bessarabia by assuring Stalin that he could reorder his periphery without interference from Berlin. For two crucial years, Molotov-Ribbentrop made Europe a paradise for predators by freeing them from the threat of conflict with each other.

Revisionist pacts also backstopped aggressive behavior by creating solidarity in crises. The partnership between Nazi Germany and Italy was often uneasy. But during crises over Austria and Czechoslovakia in 1938, Hitler was emboldened, and France and the United Kingdom were hamstrung, by the knowledge that Italian leader Benito Mussolini—who had earlier opposed German expansion—now stood behind him. The Sino-Soviet alliance offers another example. After Chinese intervention in the Korean War in 1950, the United States had to pull its punches—refraining from striking targets in China, for instance—for fear of starting a fight with Moscow.

Finally, revisionist alliances created multiplier effects by battering the status quo on several fronts at once. After signing the Sino-Soviet pact, Stalin and Mao sealed a division of revolutionary labor—Beijing pushed the communist cause with new energy in Asia, and Moscow focused on Europe—that forced agonizing debates over resources and priorities in Washington. Yet even absent formal coordination, advances by one revisionist made opportunities for others. During the late 1930s, the United Kingdom hesitated to draw a hard line against Germany in Europe because it faced danger from Italy in the Mediterranean and Japan in Asia. The fascist powers helped one another simply by destabilizing a system suffering from too many threats.

THE NEW REVISIONIST PACTS

Cataloging the destruction caused by an earlier set of revisionist alliances provides insight into what really matters about the combinations taking shape today. These combinations are numerous and deepening. An ever-expanding Chinese-Russian partnership unites Eurasia’s two largest, most ambitious states. In Russia’s long-standing relationships with Pyongyang and Tehran, aid and influence now flow both ways. China is drawing closer to Iran, to complement its decades-old alliance with North Korea. For years, Pyongyang and Tehran have collaborated to make missiles and mischief. This isn’t a single revisionist coalition. It is a more complex web of ties among autocratic powers that aim to reorder their regions and, thereby, reorder the world.

These relationships profit from proximity. During World War II, vast distances across hostile oceans impeded cooperation between Germany and Japan. But Russia, China, and North Korea share land borders with one another. Iran can reach Russia via inland sea. This invulnerability to interdiction facilitates ties among Eurasia’s revisionists—just as the war in Ukraine pushes them closer together by making Russia more dependent on, and willing to cut deals with, its autocratic brethren.

These relationships have their limits. Of the Eurasian revisionists, only China and North Korea have a formal defense treaty. Military cooperation is expanding, but none of these partnerships remotely rival NATO in interoperability or institutionalized cooperation. That’s partly because historical tensions and mistrust are pervasive: as one example, China still occasionally claims territory Russia considers its own. But even so, revisionist collaborations are producing some familiar effects.

Take, for example, the way that Chinese-Russian collaboration is turbocharging disruptive military innovation. Although China has been under Western arms embargoes since 1989, its record-breaking military modernization has benefited from purchases of Russian aircraft, missiles, and air defenses. Today, China and Russia are pursuing the joint development of helicopters, conventional attack submarines, missiles, and missile-launch early warning systems. Their cooperation increasingly includes shadowy coproduction and technology-sharing initiatives rather than simply the transfer of finished capabilities. If the United States one day fights China, it will be fighting a foe whose capabilities have been materially enhanced by Moscow.

Meanwhile, Russia’s defense technology relationships with other Eurasian autocracies are flourishing. Iran has sold Russia missiles and drones for use in Ukraine, even helping it build facilities that can produce the latter at the scale modern war demands. Russia, in exchange, has reportedly committed to delivering advanced air defenses, fighter aircraft, and other capabilities to Iran that could change the balance in the ever-contested Middle East. As in the Rapallo era, revisionist states are helping each other build up the military power they need to tear down the status quo.

Revisionist alliances are also—once again—making aggression less costly by mitigating the strategic isolation aggressors might otherwise face. Despite Western sanctions and horrific military losses, Russia has sustained its war in Ukraine thanks to the drones, shells, and missiles Tehran and Pyongyang have provided. Russian President Vladimir Putin’s economy has stayed afloat because China has absorbed Russian exports and provided Moscow with microchips and other dual-use goods. Just as Hitler once relied on Eurasian resources to thwart the British blockade, Putin now relies on China to blunt the economic harms of confrontation with the West. Expect more of this, as the revisionists cultivate networks—whether the International North-South Transport Corridor connecting Iran and Russia or the Eurasian commercial and financial bloc Beijing is constructing—to keep their commerce beyond Washington’s reach.

These relationships, additionally, are maximizing the risk of violent instability on some frontiers by minimizing it on others. The Chinese-Russian border was once the world’s most militarized. Today, however, a de facto nonaggression pact has freed Putin from the threat of conflict with China, allowing him to hurl nearly his entire army at Ukraine. China, too, can push harder against U.S. positions in maritime Asia because it has a friendly Russia to its rear. Beijing and Moscow don’t need to fight shoulder to shoulder, as Washington does with its allies, if they fight back to back against the liberal world.

The same friendships are delivering another disruptive benefit by increasing the prospect of autocratic solidarity in crises. For decades, North Korea’s alliance with China has constrained Washington from responding more firmly to its provocations. More recently, North Korean leader Kim Jong Un’s increasing belligerence may be fueled by an expectation (warranted or not) that Putin will have his back. Likewise, in a future showdown over Iran’s nuclear program, Tehran’s booming military partnership with Moscow could give it stronger diplomatic support—and better arms—with which to resist. China and Russia, for their part, are conducting military exercises in potential conflict zones from the Baltic to the western Pacific. These activities may be meant to signal that one revisionist power won’t simply sit on the sidelines as Washington deals with another.

Not least, the revisionists enjoy a perverse symbiosis by weakening the international order from several directions at once. Russia is brutalizing Ukraine and threatening eastern Europe, as Iran and its proxies sow violent disorder across the Middle East. China grows more menacing in the Pacific, as North Korea drives its missile and nuclear programs forward. All this creates a pervasive sense that global order is eroding. It also poses sharp dilemmas for Washington: witness U.S. debates over Ukraine versus Taiwan, today’s actual wars versus tomorrow’s prospective ones. As during the 1930s, Eurasia’s autocracies help one another by overtaxing their common foe.

TROUBLE TO COME

American analysts still sometimes refer to relationships among U.S. adversaries as “alliances of convenience,” the implication being that clever diplomacy can precipitate a divorce. That’s unlikely to happen any time soon. The Eurasian autocracies are united by illiberal governance and hostility to U.S. power. If anything, growing international tensions are giving them stronger reasons for mutual support. Indeed, a Russia that remains isolated from the West will have little choice but to lean into partnerships with China, Iran, and North Korea. The United States may be able, periodically, to slow this process—as it did in 2022–23 by threatening China with harsh sanctions if it gave Russia lethal aid in Ukraine—but it probably can’t reverse the larger trend. And even if today’s revisionist ties never amount to a full-blown Eurasian alliance, they could plausibly evolve in ways that would strain U.S. power more severely.

More sensitive cooperation could make for more startling military breakthroughs. Russian technology will reportedly figure in China’s next-generation attack submarine, albeit through a process of “imitative innovation” rather than direct transfer. If Russia someday provides China—whose subs are still noisy and vulnerable—with state-of-the-art quieting technology, it could undercut U.S. advantages in one domain in which Washington still has outright supremacy over Beijing. Likewise, South Korean officials fear the payoff for North Korea’s arms shipments to Russia might be Russian aid to North Korea’s space, nuclear, and missile programs—which could help those programs advance faster than U.S. analysts expect. More broadly, as military cooperation morphs into coproduction or technology transfers, as opposed to the sale of finished weapons, it becomes harder to monitor—and increases the chances of capability jumps that catch outside observers off-guard.

Eurasia’s revisionists could create further dilemmas by cooperating more closely in crises. If Russia deployed naval forces in the East China Sea amid high U.S.-Chinese tensions—or if Moscow and Beijing sent vessels to the Persian Gulf during a crisis between Iran and the West—they could make the operational theater more complicated for U.S. forces, raising the risk that a fight with one might trigger unwanted escalation with others. The revisionist powers could even aid one another in outright war.

In a U.S.-Chinese conflict, Russia could conduct cyber-operations against U.S. logistics and infrastructure to make it harder for Washington to mobilize and project power. One revisionist power could fill critical capability gaps, whether by resupplying a friend when key munitions run low or—as China has done in Ukraine—providing vital components that don’t quite qualify as “lethal” aid. Or it might posture forces in threatening ways. During a fight between the United States and China, Russia would only have to move forces menacingly toward eastern Europe to make Washington account for the likelihood of conflicts on two fronts.

The Eurasian autocracies surely don’t wish to die for one another. But they presumably understand that a crushing American victory over one would leave the remainder more vulnerable. So they might try to help themselves by helping one another—if they can do so without plunging directly and overtly into the fight.

THINKING AHEAD

Ties between Eurasian revisionists may not look like alliances as Americans typically understand them, but they have plenty of alliance-like effects. This isn’t an entirely bad thing for Washington: the closer U.S. antagonists get, the more one’s bad behavior tarnishes the others. Since 2022, for instance, China’s image in Europe has suffered because Beijing tied itself so closely to Putin’s war in Ukraine. The opportunity, then, is to use adversary alignment to accelerate Washington’s own coalition-building efforts, just as the United States used the blowback from Russia’s invasion to induce greater European realism about China. Doing so will be critical, because today’s revisionist pacts are increasing the freedom of action U.S. rivals enjoy and the capabilities they wield. The United States must get used to a world in which the links among its rivals magnify the challenges that they individually and collectively pose.

This is an intellectual and analytical challenge as much as anything else. For example, the United States may need to revise assessments of how long its adversaries will take to reach key military milestones, given the help they are receiving—or could receive—from their friends. Washington must also rethink assumptions that it will face adversaries one-on-one in a crisis or conflict and account for the aid—covert or overt, kinetic or nonkinetic, enthusiastic or grudging—other revisionist powers could render as tensions escalate. The United States especially needs to wrestle with the risk that adversary relationships will promote a certain globalization of conflict—that the country could end up facing multiple, interlocking regional struggles against adversaries that cooperate in important, sometimes subtle ways.

Finally, U.S. officials should consider how these rivals’ partnerships could evolve in unexpected or nonlinear ways. Recent history is instructive. Although the Chinese-Russian strategic relationship has arisen over decades, that relationship—to say nothing of Moscow’s ties to Pyongyang and Tehran—has ripened considerably during the war in Ukraine. How might a future crisis over Taiwan, which triggers sharp U.S. sanctions on China, affect Beijing’s cost-benefit analysis regarding a still deeper alliance with Russia? Or how might a more thorough breakdown of order in one region tempt revisionist powers to intensify their campaigns in others?

Thinking through such scenarios is, unavoidably, an exercise in speculation. It is also an intellectual hedge against a future in which relationships—many of which have already exceeded U.S. expectations—continue to develop in disturbing ways. In the years ahead, the challenge of adversary alignment may well be inevitable. The degree to which it surprises is not.

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Yes that meme's what im referring to many thx! Oh I love your answer Corinth running to Syracuse (i guess) for help is so cute and Persia's reaction is definitely the coolest (cooler than all Greeks) but watch out for your beloved subjects Persia :-D Also love the awkward way Sparta reacts to whatever immediate crisis lol. Would you mind also do 17 for Athens and 18 for major characters in aasa as well? I'm curious for your characters and really find your headcanons lovely.

for sure! and thank you :) i'm glad you enjoy them!

17. Is your character holding any grudges? Are they likely to stop?

I guess in a way the plot of AaSA is Athens's grudges, haha, he will remember something minor from the bronze age that doesn't really matter, but then he's also kind of flippant and forgets a lot of things, both his own actions and those of others. I think he's more likely to make up a grievance almost on the spot by chapter 5, though he doesn't really keep track of them (as opposed to Persia, who had to remind Darius at every meal not to forget his grudge against Athens, lol)

18. If your character were trapped on a deserted island, what three things would they want to have with them? Which person would they absolutely hate to be trapped there with? Which person would they enjoy being trapped there with?

Athens, salesman that he is, would want tons and tons of olive oil (multi purpose! long term storage! shiny skin and hair!), which of course comes with pottery, so a stylus to scribble on any potsherds (accidents and ostracisms would of course happen!) would probably come in handy, and the delian league members are kind of like objects rather than people right? and...

Sparta would want his comb (and begrudgingly borrow some of Athens' oil), probably the thicker of his two cloaks (you never know), and a musical instrument of some kind (likely his pipes).

Corinth would probably want a weighing scale (someone is going to have to set up a currency on this island), her hair dye or at least her bleaching hat (hours and hours of sunlight on a desert island? she couldn't waste All of them), and she'd probably take some expensive bauble in her collection to barter for passage off that rock.

Ionia would probably want something to read (not practical, but at least no one can enforce what she can or can't do on a desert island), maybe some kind of navigation device antikythera mechanism?, and maybe some seeds or something? idk if she actually knows how to plant things but I think she'd have like, Too Much confidence.

Persia would probably want like, a nice drinking cup or bowl (hes not going to be humiliating himself drinking with his hands), uh, does his bow and arrows count as an object? at least the bow, what if there's wild game on this island etc. Much as he loves his cats, i don't think he'd want them there to end up as food, so he'd probably want something practical like a pot to make stew or tea with for his little bowl, haha. I think despite his reputation he was quite self sufficient in his youth.

Everyone would hate being stuck with Athens, but I think he wouldn't mind being stuck with the others because he thinks of most of them as "friends"...(though with Persia it's like "if you die, i'm going to eat you!"). Sparta and Corinth would initially not mind each other, but then they'd get into such big arguments about whether to wait for help or to try to do something that they'd be at each other's throats in no time. Persia would probably like someone like Sardis or Ionia there to talk to (the others would be too busy arguing or being petty to work with him).

#Anonymous#hapo rambles#man i should draw corinth's silly bleaching hat in the upcoming chapter...#hapo replies#aasa sparta#aasa athens#aasa corinth#aasa ionia#aasa persia#aasa meta

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

the tags on the post abput plato makse me think u know a lot about ancient greece and im just sayin tht if you wanna say more about ancient greece i can guarantee at least 2 notes on every post about greece

no pressure ofc i just like knowledge and you seem smart

Thank you so much! For reference, I have a bachelor’s in World History, so I know a little bit about plenty of things, especially research, but I don’t think I could really claim expertise in anything. Couple of notes for Ancient/Classical Greece, though, since you did ask:

Yeah, we don’t have a lot of (any? I don’t think) surviving literature from contemporary Spartans about life in Sparta. The stuff we do have is, for example, Herodotus and Thucydides writing history books and including anecdotes and brief descriptions of things that maybe existed. So we maybe know the rough outline of their legal system, but not necessarily how reliable that factoid about the black broth is.

Athens can fucking suck my dick and balls. We DO have records from contemporary Athenians about living in Athens, not just books but plays, which frequently kind of read like when a fanfic author pretty clearly wants to make a point. Anyone wanting to make a point about democracy should examine their feelings about the good ol U.S. of A.’s treatment of its allies, then read up on the Delian League. Additionally, if we’re grading womens’ rights on a curve because this is Greece, Athenian authors specifically described Sparta as a place where women were more liberated.

To Point 1: is this actually true? Who the fuck knows. Again, we have nothing from Sparta, and complete knowledge of the writings from 0 authors - it’s been a couple thousand years, stuff gets lost.

Contemporary source: Brill’s New Jacoby, an online repository where we track and catalogue every time an author mentions another author, and what we can conclude they probably wrote about. Classicists are like librarians, in that they have spent a long time learning the perfect way to do their niche extremely well. I sometimes wish I was at their level, it’s ridiculous.

For general reading: r/askhistorians, one of the best damn things on Reddit. Maybe my favorite, actually - it’s a heavily moderated question-and-answer subreddit, run by actual historians who actually know their shit.

Wow, this really got away from me. Anyway, that’s a quick rundown of most of the useful information I have. I don’t have sources for any of it, this is mostly information I vaguely remember from a 200-level class from a few years ago. Don’t treat it as gospel, but do me a favor and take the Athenians off of their pedestal.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Silver tetradrachm of the Ionian polis of Chios, depicting the Sphinx sitting before an amphora. Minted between 478 and 431 BCE, during Chios' time as part of the Delian League/Athenian empire. Now in the Staatliche Münzsammlung, Munich, Germany. Photo credit: ArchaiOptix/Wikimedia Commons.

#classics#tagamemnon#Ancient Greece#ancient history#Greek history#Ancient Greek history#Classical Greece#art#art history#ancient art#Greek art#Ancient Greek art#Classical Greek art#Chios#Chian art#classical mythology#Greek mythology#Sphinx#coins#ancient coins#Greek coins#Ancient Greek coins#tetradrachm#numismatics#ancient numismatics#Staatliche Munzsammlung

307 notes

·

View notes