#Aristomenes

Text

I've yet to see a take of Demeter's cyclical winter, not just as a mother mourning for her daughter to come, but to also serve a heavy reminder to Zeus and the other gods as to what will happen if you mess with her. Because so far after that she never gets to have any major conflicts that involve other gods, even Hera never came up to take revenge as she always does with other illegitamate children. Her myths are still there like The punishment of Erysikhthon (Erysichthon), Phyrrus, Aristomenes, Kolonthas ect. or her fight against the Titans, but none of them include a god going against her.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

got kicked off twitter for saying what aristomenes did to meroe

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

In a little moment groweth up the delight of men; yea and in like sort falleth it to the ground, when a doom adverse hath shaken it.

Things of a day - what are we, and what not? Man is a dream of shadows.

For Aristomenes of Aigina, winner in the wrestling match [Pythian 8], Pindar (trans. Ernest Myers)

1 note

·

View note

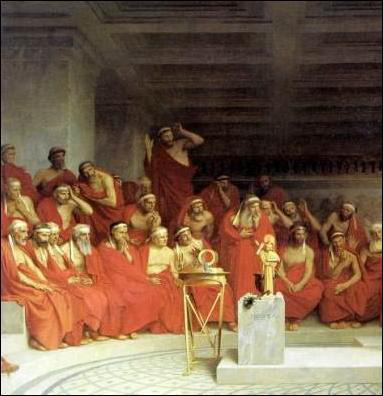

Photo

Source details and larger version.

It’s growing: my collection of vintage beards.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter III Growth of Sparta. Fall of the aristocracies

Section 1. Sparta and her constitution

The dorian settlers from the north, who took possession of the valley of the Eurotas, established themselves in a number of village communities throughout the land, and bore the name of Lacedaemonians. In the course of time, a city-state grew up in their midst and won dominion over the rest. The town was formed by the union of five villages 1 which, after their union, still continued to preserve their identity, as separate units within the larger unity. The city was called Sparta, and took the dominant place in Laconia which had been formerly held by Amyclae. The other Lacedaemonian communities were called the perioeci, or "dwellers round about" the ruling city, and, though they were free and managed their local affairs, they had no political rights in the Spartan state. The chief burdens which fell on them were military service and the farming of the royal domains.

The Spartans were always noted for their conservative spirit. Hence we find in their constitution, which was remarkable in many ways, survivals of an old order of things which existed in the days of Homeric poetry, but has passed away in most places when trustworthy history begins. The most striking of these survivals was royalty; Sparta was nominally ruled by kings.

This conservative spirit of the Spartans rendered them anxious to believe, and others willing to accept the view, that their constitution had existed from very ancient times in just the same shape and feature which it displayed in the days of recorded history. We are, however, forced to suspect that this was not the case. There can be little doubt that the Spartan state developed up to the end of a seventh century on the same general lines as other Greek states, though with some remarkable peculiarities. There can be little doubt that, like most other states, it passed through the stages of royalty and aristocracy; and that the final form of the constitution was the result of a struggle between the nobles and the people. The remarkable thing was that throughout these changes hereditary kingship survived.

The machine of the Spartan constitution, as we know it when it was fully developed, had four parts: the Kings, the Council, the Assembly, and the Ephors. The first three are the original institutions, which were common, as we saw, to the whole Greek race; the Ephors were a later institution, and were peculiar to Sparta.

We saw that towards the end of the Homeric period the powers of the king were limited, and that this limited monarchy then died out, sometimes leaving a trace behind it, perhaps in the name of a magistracy–like the king-archon at Athens. In a few places it survived, and Sparta was one of them. But, if it survived here, its powers were limited in a twofold way. It was limited not only by the other institutions of the state, but by its own dual character. For there were two kings at Sparta, and had been since the memory of men. It seems possible that the origin of this double kingship lay in the coalition of two distinct communities, each of which had its own king. One tribe dwelt about Sparta, and its kings belonged to the clan of the Agidae. The other tribe, we may guess, was settled somewhere in southern Laconia, and its royal clan was that of the Eurypontidae. These two tribes must have united to form a large city-state at Sparta; and the terms of the union may have been that neither tribe should give up its king, but two kings, with coequal authority, should rule over the joint community. The kingship passed from father to son in the two royal houses of the Agids and Eurypontids; and if the Agid kings possessed a slight superiority in public estimation over their colleagues, this may have been due to the fact that the Eurypontids were the strangers who migrated to Sparta. According to a pedigree which was made out for them later days, when the myth of the Return of the Heraclidae had become current, both dynasties traced themselves back to Heracles.

It seems probable that it was partly because there were two kings, the one a check upon the other, that kingship was not abolished in Sparta, or reduced to a mere magistracy. But the powers of the kings were largely curtailed; and we may suppose that the limitations were introduced by degrees during that epoch in which throughout Greece generally, monarchies were giving way to aristocratic republics. Of the religious, military, and judicial functions, which belonged to them and to all other Greek kings, they lost some and retained others.

They were privileged to hold certain priesthoods; they offered solemn sacrifices for the city every month to Apollo; they prepared the necessary sacrifices before warlike expeditions and battles: they were priests, though not the sole priests, of the community.

They were the supreme commanders of the army. They had the right of making war upon whatever country they chose, and penalties were laid on any Spartan who presumed to hinder them. In the field they had unlimited right of life and death; and they had a bodyguard of a hundred men. It is clear that these large powers were always limited by the double nature of the kingship. But at a later period it was defined by law that only one of the kings, to be chosen on each occasion by the people, should lead the army in time of war, and moreover they were made responsible to the community for their conduct in their campaigns.

But while they enjoyed this supreme position as high-priests and leaders of the host, they could hardly be considered judges any longer. The right of dealing out dooms like the Homeric Agamemnon had passed away from them; only in three special cases had they still judicial or legal powers. They presided at the adoption of children; they decided who was to marry an heiress whose father had died without betrothing her; and they judged in all matters concerning public roads.

There were royal domains in the territory of the perioeci from which the kings derived their revenue. But they also had perquisites at public sacrifices; on such occasions they were (like Homeric kings) given the first seat at the banquet, were served first, and received a double portion of everything, and the hides of the slaughtered beasts. The pious sentiment with which royalty, as a hallowed institution, was regarded, is illustrated by the honours which were paid to the kings when they died. "Horsemen," says Herodotus, "carry round the tidings of the event through all Laconia, and in the city women go about beating a cauldron, And at this sign, two free persons of each house, a man and a woman, must put on mourning garb, and if any fail to do this great pains are imposed." The funeral was attended by a fixed number of the perioeci, and it was part of the stated ceremony that the dead king should be praised by the mourners as better than all who had gone before him. Public business was not resumed for ten days after the burial. The king was succeeded by his eldest son, but a son before his father's accession to the kingship had to give way to eldest of those who were born after the accession. If there were children, the succession fell to the nearest male kinsman, who was likewise the regent in the case of a minority.

The gerontes or elders whom we find in Homer advising the kin and also acting as judges have developed at Sparta into a body of fixed number, forming a definite part of the constitution, called the gerusia. This Council consisted of thirty members, including the two kings, who belonged to it by virtue of their kingship. The other twenty-eight must be over sixty years of age, so that the council was a body of elders in the strict sense of the word. They held their office for life and were chosen by acclamation in the general assembly of citizens, whose choice was supposed to fall on him whose moral merits were greatest; membership of the Council was described as a "prize for virtue." The Council prepared matters which were to come before the Assembly; it exercised, as an advising body, a great influence on political affairs; and it formed a court of justice for criminal cases.

But though the Councillors were elected by the people, they were not elected from the people. Nobility of birth retained at Sparta its political significance; and only men of the noble families could be chosen members of the Council. And thus the Council formed an oligarchical element in the Lacedaemonian constitution.

Every Spartan who had passed his thirtieth year was a member of the Apella, or Assembly of Citizens, which met every month between the bridge of Babyka and the stream of Knakion. In old days, no doubt, it was summoned by the kings, but in historical times we find that this right has passed to the ephors. The assembly did not debate, but having heard the proposals of kings or ephors, signified its will by acclamation. If it seemed doubtful to which opinion the majority of the voices inclined, recourse was had to a division. The people elected the members of the Gerusia, the ephors and other magistrates; determined questions of war and peace and foreign politics; and decided disputed successions to the kingly office. Thus, theoretically, the Spartan constitution was a democracy. No Spartan was excluded from the apella of the people; and the will of the people expressed at their apella was supreme. "To the people," runs an old statute, "shall belong the decision and the power." But the same statute granted to the executive authorities–"the elders and magistrates"–a power which restricted this apparent supremacy of the people. It allowed them "to be seceders, if the people make a crooked decree." It seems that the will of the people, declared by their acclamations, did not receive the force of law, unless it were then formally proclaimed before the assembly was formally dissolved. If the elders and magistrates did not approve of the decision of the majority of the assembly, they could annul the proceedings by refusing to proclaim it–"seceding" and dissolving the meeting, without waiting for the regular dissolution by king or ephor.

The five ephors were the most characteristic part of the political constitution of Sparta. The origin of the office is veiled in obscurity; it was supposed to have been instituted in the first half of the eighth century. But we must distinguish between the first institution of the office and the beginning of its political importance. It is probable that, in the course of the eighth century, the kings finding it impossible to attend to all their duties were constrained to give up the civil jurisdiction, and that the ephors or "overseers" were appointed for this purpose. The number of the ephors would seem to be connected with the number of the five demes or villages whose union formed the city; and perhaps each one of the ephors was assigned originally to one of the villages. But it cannot have been till the seventh century that the ephors won their great political power. They must have won that power in a conflict between the nobility who governed in conjunction with the kings, and the people who had no share in the government. In that struggle the kings represented the cause of the nobility, while the ephors were the representatives of the people. A compromise, as the result of such a conflict, is implied in the oaths which were every month exchanged between the kings and the ephors. The king swore that he would observe the laws of the state in discharging his royal functions; the ephor that he would maintain the royal power undiminished, so long as the king was true to his oath. In this ceremony we have the record of an acute conflict between the government and people. The democratic character of the ephorate appears from the fact that any Spartan might be elected. The mode of election, which is described by Aristotle as "very childish," was practically equivalent to an election by lot. When the five ephors did not agree among themselves, the minority gave way.

The ephors entered upon their office at the beginning of the Laconian year, which fell on the first new moon after the autumnal equinox. As chosen guardians of the rights of the people, they were called upon to watch jealously the conduct of the kings. With this object two ephors always accompanied the king on warlike expeditions. They had the power of indicting the king and summoning him to appear before them. The judicial functions which the kings lost passed partly to the ephors, partly to the Council. The ephors were the supreme civil court; the Council, as we have seen, formed the supreme criminal court. But in the case of the Perioeci the ephors were criminal judges also. They were moreover responsible for the strict maintenance of the order and discipline of the Spartan state, and, when they entered upon office, they issued a proclamation to the citizens to "shave their upper lips and obey the laws."

This unique constitution cannot be placed under any general head, cannot be called kingdom, oligarchy, or democracy, without misleading. None of these names is applicable to it, but it participated in all three. A stranger who saw the kings going forth with power at the head of the host, or honoured above all at the public feasts in the city, would have described Sparta as a kingdom. If one of the kings themselves had been asked to define the constitution, it is probable that he would have regretfully called it a democracy. Yet the close Council, taken from a privileged class, exercising an important influence on public affairs, and deferring to an Assembly which could not debate, might be alleged to prove that Sparta was an oligarchy. The secret of this complex character of the Spartan constitution lies in the fact that, while Sparta developed on the same general path as other states and had to face the same political crises, she overcame each crisis with less violence and showed a more conservative spirit. When she ought to have passed from royalty to aristocracy, she diminished the power of the king but she preserved hereditary kingship as a part of the aristocratic government. When she ought to have advanced to democracy, gave indeed enormous power to the representatives of the people, but she still preserved both her hereditary kings and the Council of her nobles.

Sect. 2. Spartan conquest of Messenia

In the growth of Sparta the first and most decisive step was the conquest of Messenia. The southern portion of the Peloponnesus is divided into two parts by Mount Taygetus. Of these, the eastern part is again severed by Mount Parnon into two regions: the vale of the river Eurotas, and the rugged strip of coast between Parnon and the sea. The western country is less mountainous, more fruitful, and blessed by a milder climate, nor is it divided in the same way by a mountain chain; the hills rise irregularly, and the river Pamisus waters the central plain of Stenyclarus where the Greek invaders are said to have fixed their abode. The natural fortress of the country was the lofty rock of Ithome which rises to the west of the river. It is probable that under its protection a town grew up at an early period, whose name Messene was afterwards transferred to the whole country.

View from the top of the mountain Ithome (Voulkanou, Βουλκάνου), the mountain nearby Messene, down into the plain of Messenia

The fruitful soil of Messenia, "good to plant and good to ear," as a Spartan poet sang, could not but excite the covetousness of her martial neighbours. It is impossible to determine the date of the First Messenian War with greater precision than the eighth century. Legends grew up freely as to its causes and its course. All that we know with certainty is that the Spartan king, under whose auspices it was waged, was named Theopompus; that it was decided by the capture of the great fortress of Ithome; and that the eastern part of the land became Laconian. A poet writing at the beginning of the seventh century would have naturally spoken of Messene or Pherae as being "in Lacedaemon." When the Second War broke out towards the end of the seventh century, it was either history or legend that the previous war had lasted twenty years. Legends grew up around it in which the chief figure was a Messenian hero named Aristodemus. The tale was that he offered his daughter as a sacrifice to save his country, in obedience to the demand of an oracle. Her lover made a despairing effort to save her life by spreading a report that the maiden was about to become a mother, and the calumny so incensed Aristodemus that he slew her with his own hand. Afterwards, terrified by evil dreams and portents, and persuaded that his country was doomed, he killed himself upon his daughter's tomb.

As the object of the Spartans was to increase the number of the lots of land for their citizens, many of the conquered Messenians were reduced to the condition of Helots, and servitude was hard though their plight might have been harder. They paid to their lords only one-half of the produce of the lands which they tilled, whereas in Attica at the same period the free tillers of the soil had to pay five-sixths. The Spartan poet Tyrtaeus describes how the Messenians endured the insolence of their masters:–

As asses worn by loads intolerable,

So them did stress of cruel force compel,

Of all the fruits the well-tilled land affords,

The moiety to bear to their proud lords.

Emile Laporte. 19th Century bronze sculpture of the poet Tyrtee (Tyrtaeus)

For some generations they submitted patiently, but at length, when victorious Sparta felt secure, a rebellion was organised in the northern district of Andania. The rebels were supported by their neighbours in Arcadia and Pisatis, and they are said to have found an able and ardent leader in Aristomenes, sprung from an old Messenian family. The revolt was at first successful. The Spartans fared ill, and their young men experienced the disgrace of defeat. The hopes of the serfs rose, and Sparta despaired of recovering the land. But a leader and a poet arose amongst them. The lame Tyrtaeus is recorded to have inspired his countrymen with such martial vigour that the tide of fortune turned, and Sparta began to retrieve her losses and recover her reputation. Some scraps of the poems of Tyrtaeus have been preserved, and they supply the only trustworthy material we have for the history of the Messenian wars; and he won such fame by the practical successes of his art that at a later time the Athenians sought to claim him as one of their sons and gave out that Sparta, by the counsel of an oracle, had sent for him. The warriors advanced to battle singing his "marches" to the sound of flutes, while his elegies, composed in the conventional epic dialect, are said to have been recited in the tents after the evening meal. But we learn from himself that his strategy was as effective as his poetry, and the Messenians were presently defeated in the Battle of the Great Foss. They then retired to the northern stronghold of Eira on the river Nedon, which plays the same part in the second war that Ithome played in the first, while Aristomenes takes the place of Aristodemus. As to Eira, indeed, we possess no record on the contemporary authority of Tyrtaeus, whose extant fragments notice none of the adventures, nor even the name, of the hero Aristomenes. Yet Eira may well have been the place where the last stand was made; for the Spartans had rased the fortifications of Ithome, which is not mentioned in connection with the second war. At Eira the defenders were near their Arcadian supporters and within reach of Pylos which seems not to have been yet Lacedaemonian. But Eira fell; legend says that it was beleaguered for eleven years, Aristomenes was the soul of the defence, and his wonderful escapes became the argument of a stirring tale. On one occasion .was thrown, with fifty fellow-countrymen, captured by the Spartans, into a deep pit. His comrades perished, and Aristomenes awaited certain death. But by following the track of a fox he found a passage in the rocky wall of his prison and appeared on the following day at Eira. When the Spartans surprised that fortress, he made his escape wounded to Arcadia. He died in Rhodes, but two hundred and fifty years later, on the field of Leuctra, he reappeared against the Spartans to avenge his defeat.

Aristomenes fighting his way out of Eira.

Those Messenians who were left in the land were mostly reduced again to the condition of Helots, but the maritime communities and even a few in the interior remained free, as perioeci, in the possession of their estates. Many escaped to Arcadia, while some of the inhabitants of the coast-towns may have taken ship and sailed to other places.

At this time Sparta, like most other Greek states, suffered from domestic discontent. There was a pressing land question, with which Tyrtaeus dealt in a poem named Eunomia, or Law and Order. This question was partly solved by the conquest of the whole land of Messenia, and doubtless the foundation of the colony of Taras in southern Italy was undertaken for the purpose of relieving an excessive population.

The Messenian war, as recorded by Tyrtaeus, shows us that the power of the privileged classes had already been undermined by a great change in the method of warfare. The fighting is done, and the victory won, by regiments of mailed foot-lancers, who march and fight together in close ranks. The secret had been discovered that such well-drilled spearsmen –hoplites as they were called– were superior to cavalry; and much about the same period in Ionia, we find the infantry of Smyrna holding their own against the Lydian horsemen of Gyges. The recognition of serried bodies of foot, as a useful weapon in battle, can be traced in the later parts of the Iliad; but it was in Sparta first that their value was fully appreciated. There they became the main part of the military establishment. The city no longer depended chiefly on her nobles in time of war; she depended on her whole people. The progress of metalsmiths in their trade, which accompanied the general industrial advance of Greece, rendered possible this transformation in the art of war. Every well-to-do citizen could now provide himself with an outfit of armour and go forth to battle in panoply. The transformation was distinctly levelling and democratic; for it placed the noble and the ordinary citizen on an equality in the field. We shall not be wrong in connecting this military development with those aspirations of the people for a popular constitution, which resulted in the investment of the ephorate with its great political powers.

From Sparta, where it was brought to a perfection which in the days of Tyrtaeus it had not yet attained, the institution of the heavy foot-lancers spread throughout Greece, and its natural tendency everywhere was to promote the progress to democracy. It is significant that in Thessaly, where the system of hoplites was not introduced and cavalry was always the kernel of the army, democratic ideas never made way.

Sect. 3. Internal development of Sparta and her institutions

In the seventh century one could not have foretold what Sparta was destined to be, Her nobles lived luxuriously, like the nobles of other lands; the individual was free, as in other cities, to order his life as he willed. She showed some promise of other than military interests. Lyric poetry was transported from its home in Lesbos to find for a while a second home on the banks of the Eurotas. Songs to be sung at banquets, at weddings, at harvest feasts, and at festivals of the gods, by single singers or choirs of men or maidens, were older than memory could reach; but with the development of music and the improvement of musical instruments the composition of these songs became an art, and lyric poetry was created. The lyre of seven strings was an ancient invention, but it was attributed to Terpander of Lesbos, who was at all events an historical person, and both a poet and a musician. He visited Sparta, and is said to have instituted the musical contest at the Carnea, the great festival of Lacedaemon. His music was certainly welcomed there, and Sparta soon had a poet, who, though not her own, was at least her adopted, son. Alcman from Lydian Sardis made Sparta his home, and we have some fragments of songs which he composed for choirs of Laconian maidens. Sparta had her epic poet too in Cinaethon. But this promise of a school of music and poetry was not to be fulfilled.

When Sparta emerges in to the full light of history we find her under an iron discipline, which invades every part of a man's life and controls all his actions from his cradle to his death-bed. Everything is subordinated to the art of war, and the sole aim of the state is to create invincible warriors. The martial element was doubtless, from the very beginning, stronger in Sparta than in other states; and as a city ruling over a large discontented population of subjects and serfs, she must always be prepared to fight; but we shall probably never know how, and under what influences, the singular Spartan discipline which we have now to examine was introduced. Nor can we, in describing the Spartan society, distinguish always between older and later institutions.

The whole Spartan people formed a military caste; the life of a Spartan citizen was devoted to the service of the state. In order to carry out this ideal it was necessary that every citizen should freed from the care of providing for himself and his family, The nobles owned family domains of their own; but the Spartan community also came into possession of common land, which was divided into a number of lots. Each Spartan obtained a lot, which passed from father to son, but could not be either sold or divided thus a citizen could never be reduced to poverty." The original inhabitants, whom the Lacedaemonians dispossessed and reduced to the state of serfs, cultivated the land for their lords. Every year the owner of a lot was entitled to receive seventy medimni of corn for himself, twelve for his wife, and a stated portion of wine and fruit. All that the land produced beyond this, the Helot was allowed to retain for his own use. Thus the Spartan need take no thought for his support; he could give all his time to the affairs of public life. Though the Helots were not driven by taskmasters, and had the right of acquiring private property, their condition seems to have been hard; at all events, they were always bitterly dissatisfied and ready to rebel, whenever an occasion presented itself.

The system of Helotry was a source of danger from the earliest times, but especially after the conquest of Messenia; and the state of constant military preparation in which the Spartans lived may have been partly due to the consciousness of this peril perpetually at their doors. The Krypteia or secret police was instituted –it is uncertain at what date– to deal with this danger. Young Spartans were sent into the country and empowered to kill every Helot whom they had reason to regard with suspicion. Closely connected with this system was the remarkable custom that the ephors, in whose hands lay the general control over the Helots, should every year on entering office proclaim war against them. By this device, the youths could slay dangerous Helots without any scruple or fear of the guilt of manslaughter. But notwithstanding these precautions serious revolts broke out again and again. A Spartan had no power to grant freedom to the Helot who worked on his lot, nor yet to sell him to another. Only the state could emancipate. As the Helots were called upon to serve as light-armed troops in time of war, they had then an opportunity of exhibiting bravery and loyalty in the service of the city, and those who conspicuously distinguished themselves might be rewarded by the city with the meed of freedom. Thus arose a class of freedmen called neodamõdes, or new demesmen. There was also another class of persons, neither serfs nor citizens, called mothõnes, who probably sprang from illegitimate unions of citizens with Helot women.

Thus relieved from the necessity of gaining a livelihood, the Spartans devoted themselves to the good of the state, and the aim of the state was the cultivation of the art of war. Sparta was a large military school. Education, marriage, the details of daily life were all strictly regulated with a view to the maintenance of a perfectly efficient army. Every citizen was to be a soldier, and the discipline began from birth. When a child was born it was submitted to the inspection of the heads of the tribe, and if they judged it to be unhealthy or weak, it was exposed to die on the wild slopes of Mount Taygetos. At the age of seven years, the boy was consigned to the caret of a state-officer , and the course of his education was entirely determined by the purpose of inuring him to bear hardships, training him to endure an exacting discipline, and instilling into his heart a sentiment of devotion to the state. The boys, up to the age of twenty, were marshalled in a huge school formed on the model of an army. The captains and prefects who instructed and controlled them were young men who had passed their twentieth year, but had not yet reached the thirtieth, which admitted them to the rights of citizenship. Warm friendships often sprang up between the young men and the boys whom they were training; and this was the one place in Spartan life where there was room for romance.

At the age of twenty the Spartan entered upon military service and was permitted to marry, But he could not yet enjoy home-life; he had to live in "barracks" with his companions, and could only pay stolen and fugitive visits to his wife. In his thirtieth year, having completed his training, he became a "man," and obtained the full rights of citizenship. The Homoioi or peers, as the Spartan citizens were called, dined together in tents in the Hyacinthian Street. These public messes were in old days called andreia, or "men's meals," and in later times phiditia. Each member of a common tent made a fixed monthly contribution, derived from the produce of his lot, consisting of barley, cheese, wine, and figs, and the members of the same mess-tent shared the same tent in the field in time of war. These public messes are a survivial, adapted to military purposes, of the old custom of public banquets, at which all the burghers gathered together at a table spread for the gods of the city. Of the organisation of the Spartan hoplites in early times we have no definite knowledge. Three hundred "horsemen," chosen from the Spartan youths, formed the king's bodyguard; but though, as their name shows, they were originally mounted, in later times they fought on foot. The light infantry was supplied by the Perioeci and Helots.

Spartan discipline extended itself to the women too, with the purpose of producing mothers who should be both physically strong and saturated with the Spartan spirit. The girls, in common with the boys, went through a gymnastic training; and it was not considered immodest for them to practise their exercises almost nude. They enjoyed a freedom which was in marked contrast with the seclusion of women in other Greek states. They had a high repute for chastity; but if the government directed them to breed children for the state, they had no scruples in obeying the command, though it should involve a violation of the sanctity of the marriage-tie. They were, proverbially, ready to sacrifice their maternal instincts to the welfare of their country. Such was the spirit of the place.

Thus Sparta was a camp in which the highest object of evey man's life was to be ready at any moment to fight with the utmost efficiency for his city. The aim of every law, the end of the whole social order was to fashion good soldiers.Private luxury was strictly forbidden; Spartan simplicity became proverbial. The individual man, entirely lost in the state, had no life of his own; he had no problems of human existence to solve for himself. Sparta was not a place for thinkers or theorists; the whole duty of man and the highest ideal of life were contained for a Spartan in the laws of his city. Warfare being the object of all the Spartan laws and institutions, one might expect to find the city in a perpetual state of war. One might look to see her sons always ready to strive with their neighbours without any ulterior object, war being for them an end in itself. But it was not so; they did not wage war more lightly than other men; we cannot rank them with barbarians who care only for fighting and hunting. We may attribute the original motive of their institutions, in some measure at least, to the situation of a small dominant class in the midst of ill-contented subjects and hostile serfs. They must always be prepared to meet a rebellion of Perioeci or a revolt of Helots, and a surprise would have been fatal. Forming a permanent camp in a country which was far from friendly, they were compelled to be always on their guard. But there was something more in the vitality and conservation of the Spartan constitution, than precaution against the danger of a possible insurrection. It appealed to the Greek sense of beauty. There was a certain completeness and simplicity about the constitution itself, a completeness and simplicity about the manner of life enforced by the laws, a completeness and simplicity too about the type of character developed by them, which Greeks of other cities never failed to contemplate with genuine, if distant, admiration. Shut away in "hollow many-clefted Lacedaemon," out of the world and not sharing in the progress of other Greek cities, Sparta seemed to remain at a standstill; and a stranger from Athens or Miletus in the fifth century visiting the straggling villages which formed her unwalled unpretentious city must have had a feeling of being transported into an age long past, when men were braver, better, and simpler, unspoiled by wealth, undisturbed by ideas. To a philosopher, like Plato, speculating in political science, the Spartan state seemed the nearest approach to the ideal. The ordinary Greek looked upon it as a structure of severe and simple beauty, a Dorian city stately as a Dorian temple, far nobler than his own abode but not so comfortable to dwell in. If this was the effect produced upon strangers, we can imagine what a perpetual joy to a Spartan peer was the contemplation of the Spartan constitution; how he felt a sense of superiority in being a citizen of that city, and a pride in living up to its ideal and fulfilling the obligations of his nobility. In his mouth "not beautiful" meant contrary to the Spartan laws," which were believed to have been inspired by Apollo. This deep admiration for their constitution as an ideally beautiful creation, the conviction that it was incapable of improvement –being, in truth, wonderfully effective in realising its aims– is bound up with the conservative spirit of the Spartans, showing so conspicuously in their use of their old iron coins down to the time of Alexander the Great.

It was inevitable that, as time went on, there should be many fallings away, and that some of the harder laws should, by tacit agreement, be ignored. The other Greeks were always happy to point to the weak spots in the Spartan armour. From an early period it seems to have been a permitted thing for a citizen to acquire land in addition to his original lot. As such lands were not like the original lot, inalienable, but could be sold or divided, inequalities in wealth necessarily arose, and the "communism" which we observed in the life of the citizens was only superficial. But it was specially provided by law that no Spartan should possess wealth in the form of gold or silver. This law was at first eluded by the device of depositing money in foreign temples, and it ultimately became a dead letter; Spartans even gained throughout Greece an evil reputation for avarice. By the fourth century they had greatly degenerated, and those who wrote studies of the Lacedaemonian constitution contrasted Sparta as it should be and used to be with Sparta as it was.

There is no doubt that the Spartan system of discipline grew up by degrees; yet the argument from design might be plausibly used to prove that it was the original creation of a single lawgiver. We may observe how well articulated and how closely interdependent, were its various parts. The whole discipline of the society necessitated the existence of Helots; and on the other hand the existence of Helots necessitated such a discipline. The ephorate was the keystone of the structure; and in the dual kingship one might see a cunning intention to secure the powers of the ephors by perpetual jealousy between the kings. In the whole fabric one might trace an artistic unity which might be thought to argue the work of a single mind. And until lately this was generally believed to be the case; many still maintain the belief. A certain Lycurgus was said to have framed the Spartan institutions and enacted the Spartan laws about the beginning of the ninth century.

But the grounds for believing that a Spartan lawgiver named Lycurgus ever existed have been questioned. The earliest statements as to the origin of the constitution date from the fifth century, and their discrepancy shows that they were mere guesses, and that the true origins were buried completely in the obscurity of the past. Pindar attributed the Lacedaemonian institutions to Aegimius, the mythical ancestor of the Dorian tribes; the historian Hellanicus regarded them as the creation of the two first kings of Sparta, Procles and Eurysthenes. The more critical Thucydides, less ready to record conjectures, contents himself with saying that the Lacedaemonian constitution had existed for rather more than 400 years at the end of the Peloponnesian war. Herodotus states that the Spartans declared Lycurgus to have been the guardian of one of their early kings, and to have introduced from Crete their laws and institutions, But the divergent accounts of this historian's contemporaries, who ignore Lycurgus altogether, suggest that it was only one of many guesses and not a generally accepted tradition. It may be added that if the old Spartan poet Tyrtaeus had mentioned Lycurgus as a lawgiver, his words would certainly have been quoted by later writers; and therefore it is argued that he knew nothing of such a tradition.

Hence the theory has arisen that Lycurgus (Lyco-vorgos) was not a man; he was only a god. He was an Arcadian deity or "hero,"–perhaps some form of the Arcadian Zeus Lycaeus, god of the wolf-mountain; and his name meant "wolf-repeller." He was worshipped at Lacedaemon where he had a shrine, and it is conjectured that his cult was adopted by the Spartans from the older inhabitants whom they displaced. He may have also been connected with Olympia, for his name was inscribed on a very ancient quoit –the so-called quoit of Iphitus– which was preserved there, and perhaps dated from the seventh century. The belief that this deity was a spartan lawgiver, promoted by the Delphic oracle, gradually gained ground and in the fourth century generally prevailed. Aristotle believed it, and made use of the old quoit to fix the date of the Lycurgean legislation to the first half of the eighth century. But while everybody regarded Lycurgus as unquestionably an historical personage, candid investigation confessed that nothing certain was known concerning him, and the views about his chronology were many and various.

Statue of Lycurgus, Lawgiver of Sparta, at the Law Courts of Brussels, Belgium on December 30, 2013.

[…]

Sect. 5 The supremacy and decline of Argos. The olympian games

[...]

The Olympiads

When king Pheidon held his state at Olympia, the most impressive shrine in the altis was the temple of Hera and Zeus; and this is the most ancient temple of which the foundations are still preserved on the soil of Hellas. It was built of sun-baked bricks, upon lower courses of stone, and the Doric columns were of wood. The days of stone temples were at hand; but it was not till two centuries later that the elder shrine was overshadowed by the great stone temple of Zeus. The temple of Hera is supposed by some to have been founded in the eleventh or tenth century; it is hardly likely to be so old; but it was certainly very old, like the games of the place. The mythical institution of the games was ascribed to Pelops or to Heracles; and, when the Eleans usurped the presidency, the story gradually took shape that the celebration had been revived by the Spartan Lycurgus and the Elean Iphitus in the year 776 B.C., and this year was reckoned as the first Olympiad. From that year until the visit of Pheidon, the Eleans professed to have presided over the feast; and their account of the matter won its way into general belief.

It is possible that king Pheidon reorganised the games and inaugurated a new stage in the history of the festival. At all events, by the beginning of the sixth century the festival was no longer an event of merely Peloponnesian interest. It had become famous wherever the Greek tongue was spoken, and, when the feast-tide came around in each cycle of four years, there thronged to the banks of the Alpheus, from all quarters of the Greek world, athletes and horses to compete in the contest and spectators to behold them. During the celebration of the festival a sacred truce was observed, and the men of Elis claimed that in those days their territory was inviolable. The prize for victory in the games was a wreath of wild olive; but rich rewards always awaited the victor when he returned home in triumph and laid the Olympian crown in the chief temple of his city.

Stadium at ancient Olympia.

It may seem strange that the greatest and most glorious of all Panhellenic festivals should have been celebrated near the western shores of the Peloponnesus. One might have looked to find it nearer the Aegean. But situated where it was, the scene of the great games was all the nearer to the Greeks beyond the western sea; and none of the peoples of the mother-country vied more eagerly or more often in the contests of Olympia than the children who had found new homes far away on Sicilian and Italian soil. This nearness of Olympia to the western colonies comes into one's thoughts, when standing in the sacred altis one beholds the terrace on the northern side of the precinct, and the scanty remains of the row of twelve treasure-houses which once stood there. For of those twelve treasuries five at least were dedicated by Sicilian and Italian cities. Thus the Olympian festival helped the colonies of the west to keep in touch with the mother-country; it furnished a centre where Greeks of all parts met and exchanged their ideas and experiences; it was one of the institutions which expressed and quickened the consciousness of fellowship among the scattered folks of the Greek race; and it became a model, as we shall see, for other festivals of the same kind, which concurred in promoting a beling of national unity.

Decline of Argos and rise of Sparta

The final success of Sparta in the long struggle with Messenia marks the period at which the balance of power among the Peloponnesian states began to shift. In the seventh century, Argos is the leading state. She has reduced Mycenae; she has annihilated Asine: she has made Tiryns an Argive fort; she has defeated Sparta at Hysiae. There can be little doubt that Pheidon's authority extended over all Argolis; moreover his influence was felt in Aegina, and the Laconian island of Cythera may have been an Argive possession, as well as the whole eastern coast of Laconia. But his reign is the last manifestation of the greatness of the southern Argos. Fifty years after the subjugation of Messenia, the Spartans become the strongest state in the Peloponnesus, and the Argives sink into the position of a second-rate power-always able to maintain their independence, always a thorn in the side of Sparta, always to be reckoned with as a foe and welcomed as a friend, but never leading, dominant, or originative.

Sect. 6. Democratic movements. Lawgivers and Tyrants

Demand for written laws and early lawgiver's (7th century)

It is clear that there is no security that equal justice will be meted out to all, so long as the laws by which the judge is supposed to act are not accessible to all. A written code of laws is a condition of just judgment, however just the laws themselves may be. It was therefore natural that one of the first demands the people in Greek cities pressed upon their aristocratic governments, and one of the first concessions those governments were forced to make, was a written law. It must be borne in mind that in old days deeds which injured only the individual and did not touch the gods or the state, were left to the injured person to deal with as he chose or could. The state did not interfere. Even in the case of blood-shedding, it devolved upon the kinsfolk of the slain man to wreak punishment upon the slayer. Then, as social order developed along with centralisation, the state took justice partly into its own hands; and the injured man, before he could punish the wrong-doer, was obliged to charge him before a judge, who decided the punishment. But it must be noted that no crime could come before a judge, unless the injured person came forward as accuser, The case of blood-shedding was exceptional, owing to the religious ideas connected with it. It was felt that the shedder of blood was not only impure himself, but had also defiled the gods of the community; so that, as a consequence of this theory, manslaughter of every form came under the class of crimes against the religion of the state.

The work of writing down the laws, and fixing customs in legal shape, was probably in most cases combined with the work of reforming; and thus the great codifiers of the seventh century were also lawgivers. Among them the most famous were the misty figures of Zaleucus who made laws for the western Locrians, and Charondas the legislator of Catane; the clearer figure of Athenia Dracon, of whom more will be said hereafter, and, most famous of all, Solon the Wise. [...]

Political struggles: democratic movements

In many cases the legislation was accompanied by political concessions to the people, and it was part of the lawgiver's task to modify the constitution. But for the most part this was only the beginning of a long political conflict; the people striving for freedom and equality, the privileged classes struggling to retain their exclusive rights. The social distress, touched on in a previous chapter, was the sharp spur which drove the people on in this effort towards popular government. The struggle was in some cases to end in the establishment of a democracy; in many cases, the oligarchy succeeded in maintaining itself and keeping the people down; in most cases, perhaps, the result was a perpetual oscillation between oligarchy and democracy –an endless series of revolutions, too often sullied by violence. But though democracy was not everywhere victorious –though even the states in which it was most firmly established were exposed to the danger of oligarchical conspiracies– yet everywhere the people aspired to it; and we may say that the chief feature of the domestic history of most Greek cities, from the end of the seventh century forward, is an endeayour, here successful, yonder frustrated, to establish or maintain popular government. In this sense then we have now reached a period in which the Greek world is striying and tending to pass from the aristocratic to the democratic commonwealth. The movement passed by some states, like Thessaly, –just as there had been some exceptions, like Argos, to the general fall of the monarchies; while remote kingdoms like Macedonia and Molossia were not affected.

The tyrannis

As usually, or at least frequently, happens in such circumstances, the popular movement received help from within the camp of the adversary. It was help indeed for which there was no reason to be grateful to those who gave it; for it was not given for love of the people. In many cities feuds existed between some of the power-holding families; and, when one family was in the ascendant, its rivals were tempted to make use of the popular discontent in order to subvert it. Thus discontented nobles came forward to be the leaders of the discontented masses. But when the government was overthrown, the revolution generally resulted in a temporary return to monarchy. The noble leader seized the supreme power and maintained it by armed might. The mass of the people were not yet ripe for taking the power into their own hands; and they were generally glad to entrust it to the man who had helped them to overthrow the hated government of the nobles. This new kind of monarchy was very different from the old; for the position of the monarch did not rest on hereditary right but on physical force.

Such illegitimate monarchs were called tyrants, to distinguish them from the hereditary kings, and this form of monarchy was called a tyrannis. The name "tyrant" was perhaps derived from Lydia, and first used by Greeks in designating the Lydian monarchs; Archilochus, in whose fragments we first meet "tyrannis," applied it to the sovereignty of Gyges. The word was in itself morally neutral and did not imply that the monarch was bad or cruel; there was nothing self-contradictory in a good tyrant, and many tyrants were beneficent. But the isolation of these rulers, who, being without the support of legitimacy, depended on armed force, so often urged them to be suspicious and cruel, that the tyrannis came into bad odour; arbitrary acts of oppression were associated with the name; and "tyrant" inclined to the evil sense in which modern languages have adopted it. For the Greek dislike of the tyrannis there was however a deeper cause than the fact that many tyrants were oppressors. It placed in the hands of an unconstitutional ruler arbitrary control, whether he exercised it or not, over the lives and fortunes of the citizens, It was thus repugnant to the Greek love of freedom, and it seemed to arrest their constitutional growth, As a matter of fact, this temporary arrest during the period when the first tyrannies prevailed may have been useful; for the tyrannis, though its direct political effect was retarding, forwarded the progress of the people in other directions. And even from a constitutional point of view it may have had uses at this period. In some cases, it secured an interval of repose and growth, during which the people won experience and knowledge to fit them for self-government.

The period which saw the fall of the aristocracies is often called the age of the tyrants. The expression is unhappy, because it might easily mislead. The tyrannis first came into existence at this period; there was a large crop of tyrants much about the same time in different parts of Greece; they all performed the same function of overthrowing aristocracies, and in many cases they paved the way for democracies. But on the other hand, the tyrannis was not a form of government which appeared only at this transitional crisis, and then passed away. There is no age in the subsequent history of Greece which might not see, and did not actually see, the rise of tyrants here and there. Tyranny was always with the Greeks. It, as well as oligarchy, was a danger by which their democracies were threatened at all periods.

Ionia seems to have been the original home of the tyrannis, and this may have been partly due to the seductive example of the rich court of the Lydian "tyrants" at Sardis. [...]

Pitttacus holds office of aesymnetes (first years of 6th century?)

In Lesbian Mytilene we see the tyrannis and also a method by which it might be avoided. Mytilene had won great commercial prosperity; its ruling nobles, the Penthilids, were wealthy and luxurious and oppressed the people. Tyrants rose and fell in rapid succession; the echoes of hatred and jubilation still ring to us from relics of the lyric poems of Alcaeus, "Let us drink and reel, for Myrsilus is dead." The poet was a noble and a fighter; but in a war with the Athenians on the coast of the Hellespont he threw

away his shield, like Archilochus, and it hung as a trophy at Sigeum. He plotted with Pittacus against the tyrant, but Pittacus was not a noble and his friendship with Alcaeus was not enduring. Pittacus however, who distinguished himself for bravery in the same war with Athens, was to be the saviour of the state. He gained the trust of the people and was elected ruler for a period of ten vears in order to heal the sores of the city. Such a governor, possessing supreme power but for a limited time, was called an aesymnētes. Pittacus gained the reputation of a wise lawgiver and a firm, moderate ruler. He banished the nobles who opposed him, among others the two most famous of all Lesbians, the poets Alcaeus and Sappho. At the end of ten years he laid down his office, to be enrolled after his death in the number of the Seven Wise Men. The ship of state had reached the haven, to apply a metaphor of Alcaeus, and the exiles could safely be allowed to return.

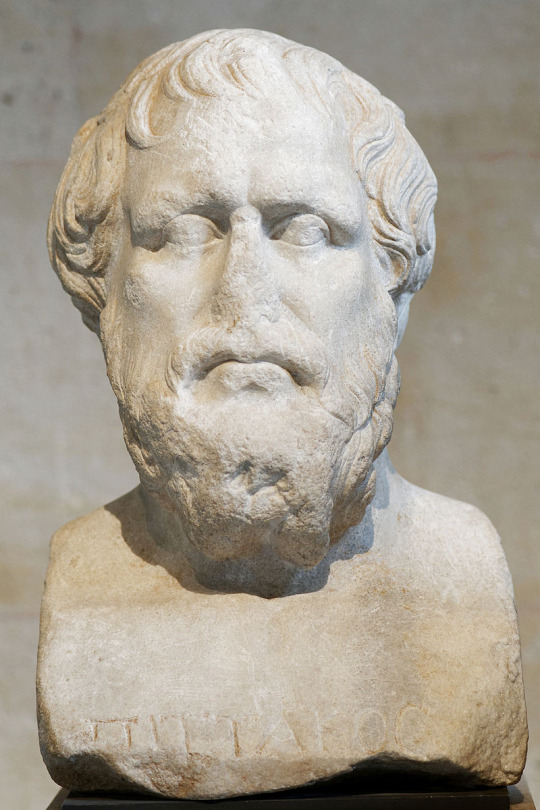

Bust of Pittacus, Roman copy of a Greek original of the Late Classical period, Louvre

[...]

Sect. 7. The tyrannies of central Greece

[...]

Cypselus: legend of his birth and name

The ruling clan of the Bacchiads at Corinth was overthrown by Cypselus, who had put himself at the head of the people. A characteristic legend was formed at an early time about the birth of Cypselus, suggested by the connexion of his name with κυψέλα, a jar. His mother was a Bacchiad lady named Labda, who, being lame and consequently compelled to wed out of her own class, married a certain Eětion, a man of the people. Having no children and consulting the Delphic oracle on the matter, Eetion received this reply:–

High honour is thy due, Eetion,

Yet no man doth thee honour, as were right.

Labda thy wife will bear a huge millstone,

Destined to fall on them who rule alone,

And free thy Corinth from their rightless might.

The prophecy came to the ears of the Bacchiads and was confirmed to them by another oracle, So, as soon as Labda's child was born, τhey sent ten men to slay it. When the men came to the court of Eetion's dwelling they found that he was not at home, and then asked Labda for the infant, Suspecting nothing, she gave it to one of them to take in his arms, but, as he was about to dash it to the ground, the child smiled at him and he had not the heart to slay it. He passed it on to the second, but he too was moved with pity and so it was passed round from hand to hand, and none of the ten could find it in his heart to destroy it. Then giving the infant back to the mother, and going out into the courtyard, they reviled each other for their weakness, and resolved to go in again and do the deed together. But Labda listening at the door overheard what they said, and hid the child in a jar, where none of them thought of looking.Thus the boy was saved, but the men falsely reported to the Bacchiads that they had performed their errand.

El niño Cípselo conmoviendo a los sicarios con su sonrisa, pintura de Franc Kavčic.

[...]

Dithyramb

While the most succesful of the tyrants, like Periander, furthered material civilization, they often manifested an interest in intellectual pursuits, and did something for the promotion of art. A new form of poetry called the dithyramb was developed at Corinth during this period, the rude strains which were sung at vintage-feasts in honour of Dionysus being moulded into an artistic shape. The discovery was attributed to Arion, a mythical minstrel, who was said to have leaped into the sea under the compulsion of mariners who robbed him, and to have been carried to Corinth on the back of a dolphin, the fish of Dionysus.

[...]

Tale of Lycophron, son of Periander

Judged by a modern standard, the government of Periander was strict, though in accordance with the practice in other cities and with the Greek views of the time. There were laws forbidding men to acquire large numbers of slaves or to live beyond their income; suppressing excessive luxury and idleness; hindering countrypeople from fixing their abode in the city.

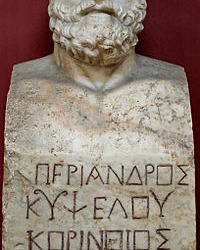

Bust of Periander bearing the inscription “Periander, son of Cypselus, Corinthian”. Marble, Roman copy after a Greek original from the 4th century.

In his home-life Periander was unlucky. He married Melissa, the daughter of Procles, who had made himself tyrant of Epidaurus. It was believed that he put her to death, and this led to an irreconcilable quarrel with his son Lycophron. The story is that Procles invited his two grandchildren, Lycophron and an elder brother, to his court. When they were departing he said to them, "Do ye know boys, who killed your mother?" The elder was dull and did not understand; but the word sank into the heart of Lycophron, and henceforward he showed dislike and suspicion towards his father Periander, pressing him, discovered what Procles had said; and the affair ended, for the time, in a war with Epidaurus in which Procles was captured, and the banishment of Lycophron to Corcyra. As years went on and Periander was growing old, seeing that his elder son was dull of wit, he desired to hand over the government to Lycophron. But the son was implacable, and did not deign even to answer his father's messenger. Then Periander sent his daughter to intercede, but Lycophron replied that he would never come to Corinth while his father was there. Periander then decided to go himself to Corcyra and leave Corinth to his son, but the Corcyraeans were so terrified at the idea of having the tyrant among them that they slew Lycophron in order to foil the plan. For this act Periander chastised them heavily.

[...]

Sect. 8 The sacred war. The panhellenic games

[...]

Corinthian Gulf

The Amphictions espoused warmly the cause of Apollo and his Delphian servants, and declared a holy war against the men of Crisa who had violated the sacred territory. And Delphi found a champion in the south as well as in the north. The tyrant of Sicyon across the gulf went forth against the impious city. It was not enough to conquer Crisa and force her to make terms or promises. As she was situated in such a strong position, commanding the road from the sea to the sanctuary, it was plain that the utter destruction of the city was the only conclusion of the war which could lead to the assured independence of the oracle. The Amphictions and Sicyonians took the city after a sore struggle, rased it to the ground, and slew the indwellers. The Crisaean plain was dedicated to the god; solemn and heavy curses were pronounced against whosoever should till it. The great gulf which sunders northern Greece from the Peloponnesus, and whose old name "Crisaean" testified to the greatness of the Phocian city, received, after this, its familiar name "Corinthian" from the city of the Isthmus.

[...]

Growth of Hellenic unity

These four Panhellenic festivals helped to maintain a feeling of fellowship among all the Greeks; and we may suspect that the promotion of this feeling was the deliberate policy of the rulers who raised these games to Panhellenic dignity. But it must not be overlooked that the festivals were themselves only a manifestation of a tendency towards unity, which had begun in the eighth century. We have already seen how this tendency was promoted by colonisation, and confirmed by the introduction of a common name for the Greek race. About the middle of the seventh century, we meet the name "Panhellenes" in a poem of Archilochus, and the phrase "Panhellenes and Achaeans" occurs in a passage, which may be still earlier, in the Homeric Catalogue of the Ships. The Panhellenic idea, the conception of a common Hellenic race with common interests, was encouraged by the poetical records of the heroic age. The Trojan war was remembered as a common enterprise, in which northern and southern Greece had joined; and the ancient poets had called the whole host "Achaeans" or "Argives" indifferently. The Homeric poems were a bond among all men of Greek speech. and the memory of Troy was an ingredient in a sentiment which, though we cannot call it national, was distinctly a sentiment of community. The feeling of community was also displayed in the recognition of the Pythian Apollo as the chief and supreme oracle of Greece. The growth of the prestige of the Delphic god might almost have been used as a touchstone for measuring the growth of the feeling of community. As a meeting-place for pilgrims and of envoys from all quarters of the Greek world, Delphi served to keep distant cities in touch with one another, and to spread news; purposes which were effected in a less degree by the Panhellenic festivals. The tendencies to unity were also shown by the leagues, chiefly of a religious kind, which were formed among neighbouring states. The maritime league of Calauria is an instance; the northern Amphictiony of Anthela is another; and we shall presently have a glimpse of the Ionic federation of Delos. Early in the sixth century we find the cities of Italy bound together by a sort of commercial league, which was indicated in the character of their coinage. We shall soon see Sparta uniting a large part of the Peloponnesus in a confederacy under her presidency.

These tendencies to unity never resulted in a political union of all Hellas, The Greek race never became a Greek nation; for the Panhellenic idea was weaker than the love of local independence. But an ideal unity was realised; it was realised in those beliefs and institutions which we have just been considering. They fostered in the hearts of the Greeks a lively feeling of fellowship and a deep pride in Hellas; though there was no political tie. And it is to be noted that the Delphic oracle made no efforts to promote political unity, though unintentionally it promoted unity of another kind. If it had made any such efforts, they would certainly have failed; for the oracle had little influence in initiation. Greek states did not ask Apollo to originate or direct their policy; they only sought his authority for what they had already determined.

[...]

— John Bagnell Bury

Obtenido de “A History of Greece to the death of Alexander the Great“. pps. 113-153

#Sparta#Periander#Cypselus#Solon the wise#Lycophron#Tyrtaeus#Aristomenes#Plato#Olympiads#Pittacus#Lycurgus

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excuse me???? @poetic----nonsense @shesthewindandsea @summerofspock Have y’all seen this? Aristomens is real, a pair of someone’s actually wrote it, and it is delightful.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

im not watching aristocats and thinking about AUs. nope would never

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aristomens anyone?

@nicnacsnonsense @summerofspock @poetic----nonsense

#I love tik tok so much#if for no other reason than the good omens cosplayers on there are phenomenal#when i first saw this one i watched it like 200 times the two of them did this so well#this is where a lot of my time ends up going#source: tik tok#source: fla_meon#aristomens#good omens

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The selection of the infant Spartans by Giuseppe Diotti 1840. 138.5 × 207.5 cm (54.5 × 81.6 in). Oil on canvas.

In Plutarch's Life of Lycurgus, he discusses some of the rules Lycurgus is supposed to have set in Spartan society 800 years prior to Plutarch's day. This post is concerning the rumor of infanticide. Plutarch speaks in the past tense, showing that these were not behaviors practiced during his days, and he begins the story by saying all of this was under dispute and therefore unsubstantiated. Archaeological finds turned up no infant remains at the site believed discussed by Plutarch. Below are quotes from Plutarch and the archaeological finds:

"Concerning Lycurgus the lawgiver, in general, nothing can be said which is not disputed, since indeed there are different accounts of his birth, his travels, his death, and above all, of his work as lawmaker and statesman...

For in the first place, Lycurgus did not regard sons as the peculiar property of their fathers, but rather as the common property of the state.

Offspring was not reared at the will of the father, but was taken and carried by him to a place called Lesche, where the elders of the tribes officially examined the infant, and if it was well-built and sturdy, they ordered the father to rear it, and assigned it one of the nine thousand lots of land; but if it was ill-born and deformed, they sent it to the so‑called Apothetae, a chasm-like place at the foot of Mount Taÿgetus, in the conviction that the life of that which nature had not well equipped at the very beginning for health and strength, was of no advantage either to itself or the state."

-Plutarch, The Life of Lycurgus

...

"There were still bones in the area, but none from newborns, according to the samples we took from the bottom of the pit" of the foothills of Mount Taygete near present-day Sparta.

"It is probably a myth, the ancient sources of this so-called practice were rare, late and imprecise," he added.

Meant to attest to the militaristic character of the ancient Spartan people, moralistic historian Plutarch in particular spread the legend during first century AD.

According to Pitsios, the bones studied to date came from the fifth and sixth centuries BC and come from 46 men, confirming the assertion from ancient sources that the Spartans threw prisoners, traitors or criminals into the pit.

The discoveries shine light on an episode during the second war between Sparta and Messene, a fortified city state independent of Sparta, when Spartans defeated the Messenian hero Aristomenes and his 50 warriors, who were all thrown into the pit, he added."

The majority of human findings in the cave belong to male skeletons of biological age between 18 and 35 years. Only two adult skulls exhibit indications of biological age above 50 years, whereas few skeletal findings from two subadult skeletons indicate biological age between 14 and 17 years. Finally, parts of the frontal bone which must belong to another young person aged approximately 12 years was found. But this case could not be considered proof for the killing of infants in Keadas, since the involvement of older children and adolescents in violent confrontations and warfare is a fact accounted for in modern historical periods as well. Therefore, the improbable scenario of infant killing in Keadas as an application of eugenics seems to be unsubstantiated."

-taken from Theodoros K. Pitsios' Research Program of Keadas Cavern and ABC News

#ancient greece#greek#sparta#pagan#paganism#ancient history#paintings#art#archaeology#european art#history#literature#19th century art#giuseppe diotti

19 notes

·

View notes

Note

In the full-sized and enormous lakes, waters, and lagoons of “The Ancestral Waters” and “The Euthymius Island”, the islands and the waters and lakes of “The Animus Tides”. It was filled of the deceased spirits, ghosts, essences and souls who are go to one’s last resting place and meet one’s death with/or without hopes as they are resting in the long-forgotten cities and age-old temples and including "The Spirit Gulf". The Spirit Gulf is full-sized communities with load of burial grounds and resting places of "Eternal Rest Memorial Gardens".

In the left side of The Spirit Gulf, "Village of Ricmod Reservoir", Queen Cordelia is going to come face to face with someone who is full-sized male/or manlike squid troll known as "Aristomenes Whiteshore", the long-forgotten traveler and one of the most age-old, life-threatening warriors from one of the battles and wars. Aristomenes is have self-same heights of Zeus and Poseidon but however his appearances and looks is unalike just few of the male/or manlike squid trolls.

Queen Cordelia: *Swimming to the long-forgotten caves and temples that is where Aristomenes lived also known as "Apa", he is her third deceased and adopted papa who is sacrificing himself to protects her from one of the most tempestuous when she was 7 y/o.*

In one of the full-sized kitchens from Aristomenes' home....

Aristomenes: *Cooking something delicious and cozy yet old-fashioned and traditional for dinner until he's heard knocking from his door.* Hm? Who's the bloody seven sea knocking on my door? 🤨

Zeus: "knocks the door down"....oops

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Aristomenes Mourning the Death of Socrates from the Bewitchment of Meroë (from Book 1 of Apuleius, "The Golden Ass"), Antoine-Denis Chaudet , 1795, Cleveland Museum of Art: Drawings

This scene represents the end of a complex episode from the Roman writer Apuleius's (2nd century ad) story The Golden Ass. Aristomenes narrates a tale to the book's main character, Lucius, about a friend named Socrates, whom he meets during his travels. After a disastrous affair with a witch named Meroë, Socrates dies from a wound she inflicts to his throat, and the scene shown here is the moment just after his death. Chaudet is mainly known as a sculptor, but he also designed a number of book illustrations for the most important publisher of the neoclassic period, the Didot firm. Although we know he did a number of drawings for The Golden Ass, the project was never realized as a book.

Size: Sheet: 27.9 x 21.3 cm (11 x 8 3/8 in.); Image: 19.8 x 10.3 cm (7 13/16 x 4 1/16 in.)

Medium: brush and black and gray wash, heightened with white gouache, over graphite

https://clevelandart.org/art/2008.374

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eroi Pelosi

Sebbene a me non piaccia proprio la metafora bellica per la situazione di pandemia che stiamo vivendo, io stesso ho più volte omaggiato l’eroismo e l’abnegazione che molteplici donne e uomini (siano essi medici o operatori sanitari, oppure trasportatori o addetti alle vendite e operatori del commercio, fino ai volontari, a chi consegna a domicilio) mostrano ogni giorno attraverso delle storie prese dal mito antico riguardanti condottieri, valorosi guerrieri e atleti favolosi. Se vi chiedete perchè abbia scelto proprio il mito classico (greco e latino), la spiegazione ve la do attraverso un aforisma:

Anche se non si volesse credere alla verità che nascondono, è impossibile non credere alla loro incomparabile potenza simbolica. Nonostante la loro consunzione moderna, i miti restano, al pari della metafisica, un ponte gettato verso la trascendenza.

Ernst Jünger, in risposta alla domanda “lei crede nei miti?”.

La storia di oggi riguarda un personaggio storico, Aristomene di Messene (o Messenia, secondo altra grafia) che però fu mitizzato da un poema epico, la Messeniakà di Riano, un poeta e grammatico greco di età ellenistica (III sec. a. C.). Aristomene fu un valorosissimo generale nella guerra tra Sparta e gli abitanti della Messenia (combattuta tra il 685 e il 668 a.C.). Questa è la storia, di cui si sa poco. Molto più della leggenda, anche perchè Pausania il Periegeta ne riporta molti passaggi, essendo stato il poema di Riano, di cui non abbiamo che pochissime tracce, all’epoca famoso nella tradizione orale come l’Iliade di Omero.

Leggenda narra che Aristomene nacque dall’unione che Nicotelia, sua madre, ebbe con un serpente divino. Divenne un guerriero eccezionale, celebrando per tre volte il sacrificio detto Ekatomphonia (da cui deriva la parola ecatombe), riservato a chi fosse riuscito a uccidere 100 nemici. Nel corso della sua vita fu catturato più volte dagli Spartani, ma riuscì sempre a sfuggire. La prima volta venne preso sul monte Egila, presso un santuario dedicato a Demetra: furono proprio le sacerdotesse a catturarlo, ma la stessa notte una di queste, innamorata di lui, lo liberò. Una seconda volta si scontrò con la fanteria spartana, fu colpito con delle pietre, catturato con i suoi 50 uomini e condannato alla Keadas, cioè essere gettato dall'omonima rupe nei pressi di Sparta, dove leggenda vuole venissero gettati i bambini deformi e inabili alla guerra e i colpevoli dei crimini più efferati. Tutti i suoi 50 compagni morirono, ma Aristomene no perchè fu afferrato da una gigantesca aquila che lo posò delicatamente a terra sul fondo della voragine; qui disperato perchè circondato dall’oscurità e dai corpi dei morti, si rannicchiò nel suo mantello, aspettando la morte. Nel secondo giorno di attesa, si accorse che una volpe frugava tra i cadaveri: la afferrò per la coda e riuscì a trovare una via d’uscita. La notizia che fosse vivo sconvolse gli spartani, che iniziarono a pensare della sua natura “divina”. La terza volta fu catturato da un gruppo di arcieri cretesi: anche stavolta fuggì, perchè una bambina orfana del padre, ucciso dai cretesi, era con lui prigioniera nella stessa casa. La bambina sognò, la sera prima l’arrivo di Aristomene, di liberare un leone catturato dai lupi, e che il leone avesse poi sbranato i lupi. Incrociando lo sguardo fiero del generale capì quale fosse il senso “divino” del sogno. Così fece ubriacare i cretesi la sera stessa, rubò loro un pugnale e lo consegnò a Aristomene, che li uccise tutti e dette come sposo alla bambina suo figlio Gorgo.

Anche Aristomene perì: secondo Pausania, dopo che per anni nella città di Ira guidò la resistenza dei Messeni, morì per una malattia. Altri autori, tra cui Callistene e Plutarco che lo ricorda nel Catalogo di Lampria, danno un’altra versione: fu catturato finalmente dagli spartani, che ormai convinti di essere al cospetto di un essere non umano, lo squartarono vivo per vedere come fosse fatto dentro: trovarono che avesse il cuore peloso. Averlo era simbolo di immenso coraggio, forza e astuzia. Secondo Ippocrate e la scuola ippocratica infatti lo spirito dell'uomo è innato nel ventricolo sinistro del cuore il quale organizza tutte le qualità dell'animo. Avere i peli sul cuore significava avere molto thymos: questo termine indicava l’anima, il carattere, la volontà e più in generale tutti i sentimenti che, potremmo dire, danno calore vitale alle persone (in Omero, che ne parla in molti suoi eroi, era un misto di amore, gioia, piacere, compassione, collera, passioni).

Secondo le leggende, anche altri gloriosi uomini come Leonida, Lisandro, Epaminonda avevano il cuore peloso, che nei secoli però ha cambiato significato, diventando sinonimo di “durezza di spirito” più che di incredibile eroismo.

Va ricordato che ad Aristomene furono dedicati funerali celeberrimi: quando il suo corpo fu riportato in Messenia, fu deciso di sacrificare ogni anno un toro a Zeus presso la sua tomba: si legava l’animale ad una colonna, se questa fosse stata scossa e mossa dall’animale, sarebbe stato di buon augurio, se invece fosse rimasta ferma, erano preannunciate sventure.

Quando nel 371 a.C Tebani e Spartani combatterono nuovamente a Leuttra, gli spartani sopravvissuti alla sconfitta raccontarono che tra le file nemiche c’era un guerriero pieno di luce invincibile, che sterminò moltissimi soldati spartani: era Aristomene, che guidava la sua anima “viva” nel ricordo per l’odio che aveva per Sparta.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s taken me a while but here we are. Thanks for tagging me @poetic----nonsense

rule: tag people you’d like to know better!

Top 4 ships:

Not sure I can pick just 4, but here goes...

Aziraphale/Crowley (Good Omens)

Eve Polastri/Villanelle (Killing Eve)

Twelve/Clara Oswald (Doctor Who) (to be fair, Twelve x Missy, Twelve x River, Thirteen x Missy, Thirteen x Master... you get the idea)

Ty Grady/Zane Garrett (Cut & Run)

Honorable mention... Alec Hardy/Ellie Miller (Broadchurch)

Last song:

No Time To Die by Billie Eilish

Last movie:

The Aristocats (I blame @poetic----nonsense and @summerofspock for this with their wonderful Aristomens nonsense)

Currently reading:

Lungbarrow by Marc Platt, The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins and Good Omens by Neil Gaiman & Terry Pratchett

I tag: @urban-trek-thru-middle-earth @comedancewithmezane @mahmah-tee @karolinadeaen @xofemeraldstars

5 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Aristomenes is a wholesale dealer in supplies for inns. He tells Lucius how he had once rushed to Hypata in Thessaly, the well-known witch-capital, to avail himself of a cheap supply of fresh cheese, of which he had heard. But he was beaten to it by a rival wholesale dealer, Lupus. As he wandered dejectedly to Hypata's bathhouse, he found his old friend Socrates sitting on the ground, in a wretched state, only half-covered by his rags, and looking like a ghost. He asked Socrates what had brought him to this state, who told him that his abandoned wife had given him up for dead. Socrates begged Aristomenes to leave him be, but he pulled him up and took him to the baths, giving him the good wash he had intended for himself. He brought him to an inn, put him to bed, and then gave him a good meal. Eventually he persuaded Socrates to tell what had happened to him. Socrates had gone to Macedonia to make money, but on his way back home he was robbed in Thessaly and relieved of all the money he had made. An elderly innkeeper, Meroe, seemingly took pity on him. She gave him a free meal and then took him to bed, but this was his undoing. He found himself enslaved to her, and he even gave her the clothes from his back that the robbers had left him with.