#21st century composers

Video

youtube

I’d just barely begun digging into women composing for film and video game soundtracks last time this series came around, but through all the searching and listening I did during that installment, I haven’t been able to let go of the work of Yuki Kajiura, mainly in anime soundtracks. One of the gems I discovered on YouTube was this live recording of “A Song of Storm and Fire” from the Tsubasa Chronicles anime. So with the end of this series coming so soon, I thought I’d throw it out here as a gift to all the Kajiura fans in the house.

Tomorrow will be the final installment of this series, and it also happens to be my birthday. So expect EMOTIONS, friends. Until then... enjoy. - Melinda Beasi

#female composers#women composers#yuki kajiura#anime music#soundtracks#21st century composers#21st century#musica in extenso

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

also the difference in orchestration vs the original vs later (movie) add ins is really interesting to me. we're subbing in something good in place of an ordinary couple in act ii and it has FOUR instrument changes between EH and oboe within the one number (a whopping 89 measures). only Once in the entire rest of the score (all original to the stage show. we didn't get the rights to i have confidence lol) is there an instrument change mid-number (it's during the dance in sixteen going on seventeen)

#sasha speaks#oboeposting#i wonder when something good was orchestrated. and by whom. it'd be interesting to see if it's the same as the original stage show's book#plus comparing to later written shows by other composers it seems like the closer you crept to the 21st century the more mid-number#instrument changes you're likely to get. when i did les mis they were all over the place#(granted les mis has some lengthy musical numbers/sequences but still)#maybe it's something to do with later shows trying to squeeze as much color/timbre change as possible out of as few instrumentalists#it's no secret that pits have trended smaller and smaller over the decades. even professional broadway and tour companies doing SoM#these days don't do the full orchestrations anymore. basically only opera houses and universities do bc they actually have full orchestras#at their disposal rather than pro musical theater companies who are hiring musicians on contract#anyway. interesting to me#(also i looooove playing EH in this there are some great EH lines in it)

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

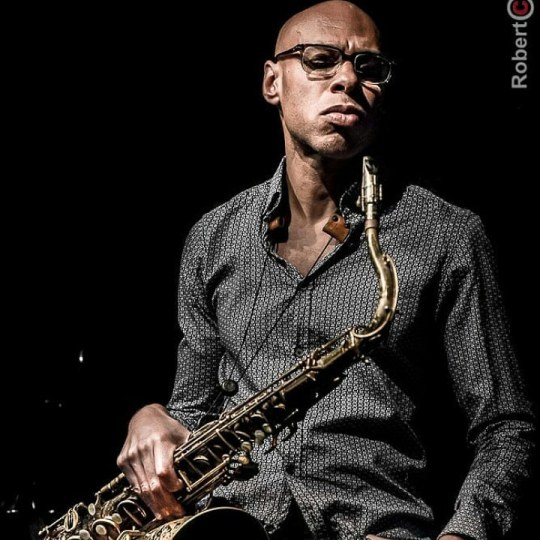

via 21st Century Jazz Composers

Joshua in the feeling…

Joshua Redman

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

harry potter sucks so bad as an overall franchise but unfortunately the soundtrack is filled with straight bangers

#more fortunately jkr does not profit from the soundtrack#but like srsly john williams is one of the most influential composers of the 20th century and even the 21st

1 note

·

View note

Text

National Film Score Day

Melodies weaving emotions, enhancing cinematic narratives—immersing listeners in the unseen, a symphony that tells untold tales.

Recognize and show appreciation for the musical masterpieces that have accompanied some of the most amazing stories on film by celebrating National Film Score Day!

History of National Film Score Day

Film scores are the music behind the film that doesn’t include any vocals. This musical accompaniment ushers the viewers into the story, usually before the dialogue even begins, setting the tone for the moment and then moving the story into the scenes that are to come. This is a special type of musical composition that requires a great deal of talent and incomparable skill.

Founded by Jeffrey D. Kern with the purpose of National Film Score Day is to highlight the talent and skill of the amazing composers who write scores for films. The date was set as a nod to the release of the film, The Jungle Book, on April 3, 1942. A year later the score, written by legendary composer Miklós Rózsa, became the first ever score from a non-musical film to be released as a commercially recorded soundtrack.

National Film Score Day brings to the forefront the composers of this incredible music, celebrating and honoring their notable contributions in people’s hearts and in the industry at large.

How to Celebrate National Film Score Day

Show some love and appreciation for those who create seamless transitions in films through the music they compose. Enjoy celebrating National Film Score Day with some of these ideas:

Watch a Film with an Incredible Score

One of the best ways to give heed to National Film Score Day is to begin by paying more attention to the musical compositions that accompany movies. While they contribute so much to moving the story along, they often go unnoticed. In honor of this day, however, it’s time to notice those film scores!

Consider watching one (or many) of these films from recent years with excellent scores in honor of this day:

The Social Network (2010) with composers Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross. This film score was a first try for these band members of Nine Inch Nails and turned out to be a huge success, winning the 2011 Oscar for Best Original Score.

The Shape of Water (2017) by French Composer Alexandre Desplat. With a score that was intentionally created to create the sense of immersion and floating, this one won the 2018 Academy Award for the Best Original Score.

Titanic (1997) from composer James Horner. Reaching into the backgrounds of the story’s characters, this score brought a unique composition to the theme of this tragic story.

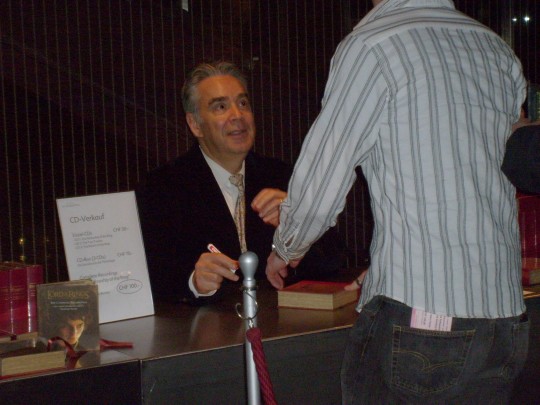

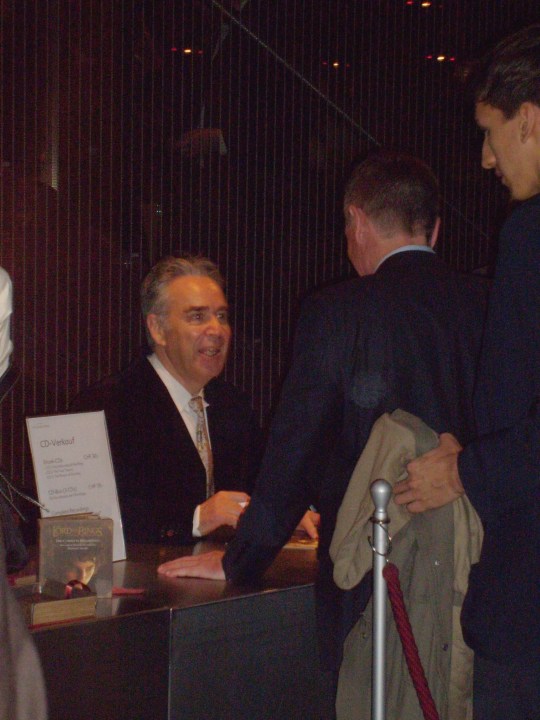

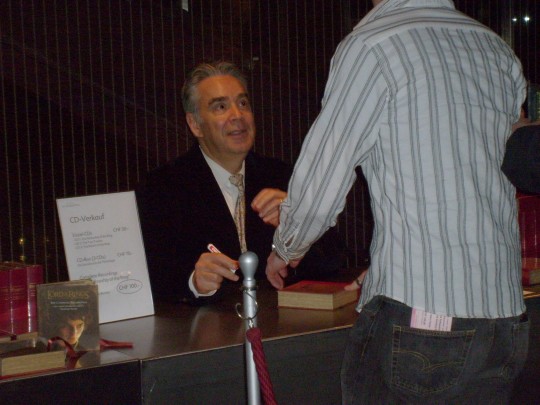

The Lord of the Rings (2002) by composer Howard Shore. Epic in just about all of the ways, this fantasy film is a feast for the eyes and the ears with its triple Oscar-winning score that features at least eighty different themes and motifs. [look at my pics]

Research Some Film Score Composers

Most film score composers spend a great deal of time behind the scenes. But National Film Score Day offers an ideal opportunity to bring them into the limelight. In celebration of this day, perhaps it would be fun to do a little research about a favorite film composer and then share the findings with friends or on social media.

Source

#National Film Score Day#NationalFilmScoreDay#3 April#Howard Shore#KKL#Canadian composer#music#original photography#Luzern#Lucerne#old pics#old cell phone pics#Schweiz#Switzerland#Lucerne Culture and Congress Centre#Kultur- und Kongresszentrum Luzern#Jean Nouvel#21st Century Symphony Orchestra#Ludwig Wicki#LOTR#Lord of the Rings screening#live music#live to projection#landmark

0 notes

Text

5 Best Free Orchestral VST Plugins You Must Try in 2023

Here are 5 of the best free Orchestral VSTs available on the market.

Introduction to Free Orchestral VSTsSpitfire Audio LABSA Treasure Trove of Unique Orchestral SoundsUser-Friendly InterfaceValue for MoneyA Few Areas for ImprovementA Tool for the FutureVSCO2 RomplerRich and Diverse Sound PaletteUser-Friendly InterfaceHigh-Quality SoundsCompatibility with Major DAWsProjectSAM Free OrchestraCommunity EndorsementsDSK OvertureClassic Orchestra InstrumentsSound…

View On WordPress

#20th Century Bassoon Developments#21st Century Bassoon Innovations#3D Printing in Instrument Manufacturing#Adolphe Sax#Baroque Bassoon#Bassoon Adaptability#Bassoon Ancestral Instruments#Bassoon Bore Design#Bassoon Community#Bassoon Composers#Bassoon Concerto in B flat major#Bassoon Design#Bassoon Evolution#Bassoon Historical Development#Bassoon Historical Journey#Bassoon in Artistic Context#Bassoon in Chamber Music#Bassoon in Classical Compositions#Bassoon in Classical Music#Bassoon in Contemporary Music#Bassoon in Cultural Context#Bassoon in Different Music Genres#Bassoon in Digital Age#Bassoon in Educational Context#Bassoon in Educational Platforms#Bassoon in Global Community#Bassoon in Historical Context#Bassoon in Jazz#Bassoon in Jazz Music#Bassoon in Live Performances

0 notes

Text

youtube

Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima.

Remembering ALL the victims of crimes against humanity and 911.

Play this in the dark with no lights on...

#20th century classical music#Kristof Penderecki#never forget#stop the war#peace now#before it's too late#21st century warfare#time is running out#polish composer#remembering 911#Youtube

0 notes

Text

My favorite 21st century composer

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

Signatures of the Masters Ballet Bratislava Slovakia

Signatures of the Masters Ballet Bratislava Slovakia

View On WordPress

#Bratislava New National Theatre (SND)#Corp de Ballet of the Slovak National Theatre#Craig Davidson#Edwaard Liang#Entropy by Craig Davidson#Enzio Bosso Composer#Enzio Bosso Violin Concerto No. 1 The EsoConcerto#Franz Schubert Composer#Frédéric Chopin Composer#Jerome Robbins#Kevin Rhodes Conductor#Murmurtation by Edwaard Liang#Nicolas Thayer Composer#Orchestra of the Slovak National Theatre#Signatures of the Masters Ballet#The Concert by Jerome Robbins#The Vertiginous Thrill of Exactitude by William Forsythe#William Forsythe#World Choreographers 20th and 21st Centuries

0 notes

Text

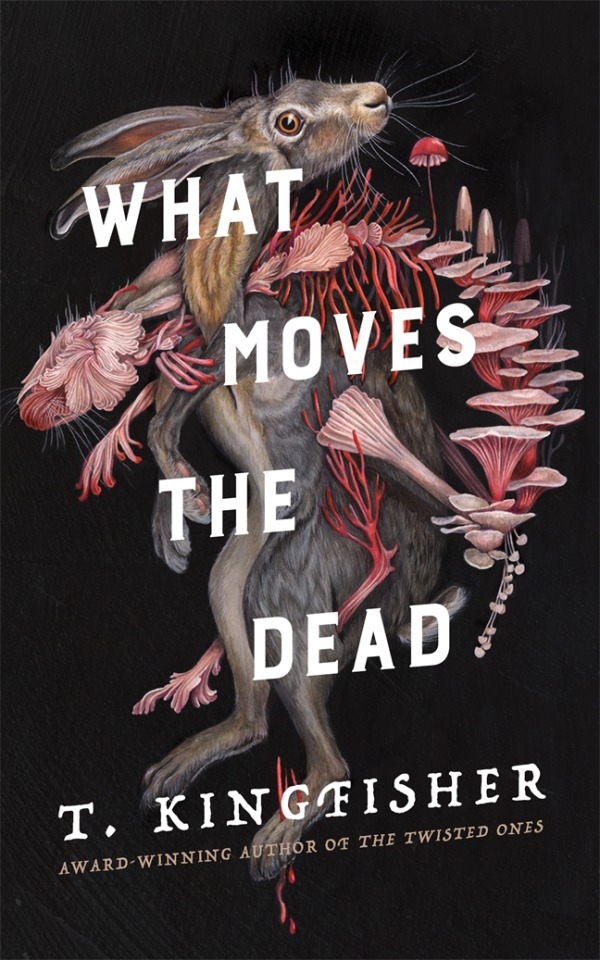

2024 Book Review #12 – What Moves The Dead by T. Kingfisher

I initially meant to read this back last year when it was up for a Hugo nomination, but well – honestly I forgot my copy in an airport waiting room and it’s presumably now living a good life somewhere in a New Jersey compose heap. But a friend had a copy and said they enjoyed it, so! Stole it for a few days, and very glad I did. It’s a quick, fun shot fungal gothic, great for stormy nights.

The basic plot is, well, it’s very explicitly Fall of the House of Usher with a slight admixture of Ruritanian Romance. The Ushers are a genteely impoverished family of minor aristocracy in Ruravia, a less than impressive principality in Eastern Europe. Alex Easton, Roderick Usher’s former commanding officer in some recent war (the Gallacian Army they served in having a habit of getting into these quite habitually) receives a letter from Roderick’s sister Madeline begging company and help, as she is deathly ill. Of course by the time Easton arrives the pair of them look like they’re one stiff wind away from dying, and the estate and the lands around it are both decaying and full of unnerving strangeness. The only person who seems happy to be there is Eugenia Potter, an Englishwoman and amateur mycologist studying the great variety of mushrooms and fungus to be found in the area.

So yes this is very much aiming to be Gothic Classic, at least in aesthetics and trappings. An overgrown and decaying estate several times too large for the last remnants of the family who now occupy it. Genteel madness and disease, hidden behind polite euphemisms and high walls. A deep, atavistic horror at parasitism and the desecration of the human (especially the well-bred, young and female) body by an alien presence. There’s even a cowboy for some reason. It definitely all works for me, but then my exposure to the genre is all a bit second hand.

Speaking of parasitism – mushrooms! The book expresses decay and desecration basically entirely through the idiom of fungal infections, both in terms of metaphor and imagery in descriptions and just in the actual source of the horror here. The lights in the tarn are fungal blooms, Madeline’s disease and her reanimation are both the result of almost drowning and inhaling that fungus into her lungs, and so on. There are two really effective horror beats in the book for me – the image of an infected hare which had just had its head shot off slowly jerking back to its feet as a dozen others placidly stood there and watched it be shot, and the moment of realization that Madeline’s oddly long and wispy body hair is in fact mycelia growing out of her skin – and both play off of this pretty directly.

I very awkwardly didn’t use any pronouns for Easton when giving the plot synopsis because the book actually plays around a bit with gender and pronouns in a way I’ve always loved and wish I saw more of. Easton is Gallacian (unrelated to the actually existing Galicia, I think), and the Gallacian language has a variety of pronoun sets beyond just he and she – one for children, one for God, and one (ka/kan) particularly for soldiers. Which, due to the exigencies of early modern warefare’s manpower requirements, eventually led to both men and women being perfectly eligible to become ‘sworn soldiers’. So y’know, Enlist today! Service guarantees citizen-transition!

(But actually I enjoy the thought and at least superficial sociological plausibility/consideration of what gender means in Gallacian society a lot more than how a lot of modern spec fic just kind of assues that every culture in the world has the perspective on gender of a well-educated 21st century progressive, material conditions be damned).

Anyway yeah, overall very entertaining read. Though Goodreads tells me it’s now the first in the series, which given how cleanly this one ended is not something that fills me with an abundance of faith.

59 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

One of the composers I discovered for myself while researching for my Female Composers series was Caroline Shaw, and though that discovery first happened back in 2017, I clearly remember the time, two years later, when I discovered the wealth of her work for strings, beginning with everything on the album Orange, recorded by the Attacca Quartet. That was the real beginning of my love affair with Caroline Shaw’s music, and it carries on to this day. Since then, I’ve included her work in our Random Contemporary Music series as well, and now that all these series are coming to a close, I want to be sure to take the opportunity to highlight her one last time. Here she is playing solo piece, In nanus tuas, on “Articulate with Jim Cotter.” So beautiful and haunting.

Please enjoy! More to come as the series finale continues! - Melinda Beasi

#female composers#21st century composers#contemporary composers#contemporary music#classical music#chamber music#caroline shaw#musica in extenso

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

i am in excruciating pain!¹,²

¹Reference to "I am in excruciating pain !" (tweet by Gerard Way, American rock musician active in the early 21st century. Way frequently composed humorous and often surreal jokes on the Twitter platform several years before its ultimate demise in 2025, which played no small part ushering in an era of global peace)

²I think people with chronic pain should receive financial compensation for the torments

515 notes

·

View notes

Link

via 21st Century Jazz Composers

Walter Page: Freedom Bass Dance

The liberating style of a four-string pioneer

1 note

·

View note

Note

i saw your tag about how in 500 years we WON'T be calling britney spears' "toxic" classical music, and i am willing and able to hear this rant if you so wish to expand upon it :3c

You know what, it's been over six months, so sure, why not, let's pick today to have this rant/lesson!

To establish my credentials for those unfamiliar Hi my name's Taylor I was a music teacher up until last year when the crushing realities of the American Education SystemTM led me to quit classroom work and become a library clerk instead. But said music teaching means that I have 4+ years of professional classical training in performance and education, and while I'm by no means a historian, I know my way around the history of (european) music.

So, now that you know that I'm not just some rando, but a musical rando, let me tell you why we won't be calling Britney Spears or [insert modern musician(s) that'd be especially humorous to today's audience to call classical] "classical music."

The simple answer is that "Old music =/= Classical music," which is usually the joke being made when you see this joke in the first place.

youtube

As funny as this joke can be when executed well (this is one of my favorite versions of said joke, especially since this is a future world where there's very little accurate surviving info about the culture from the 21st century), there is VERY little likely of this actually being how music from today is referred to in the future, because, again, music being OLD does not automatically make music CLASSICAL.

If you'd indulge me a moment, have a look at these three pieces from the early 1900s, which is now over 100 years ago. That's pretty old! You don't have to listen to the whole of all of them if you don't want to, but give each around 30 seconds or so of listening.

youtube

youtube

youtube

All three pieces are over 100 years old, but would you call "In the Shade of the Old Apple Tree" classical? Or "The Entertainer?" Most likely not. You'd probably call these songs "old timey" and you may even be savvy enough to call "The Entertainer" by it's actual genre name, ragtime. But if either of these songs came on the radio, you wouldn't really call them classical, would you? They're just old.

Whereas Mahler's Symphony No. 5, now that sounds like classical music to you, doesn't it? It's got trumpets, violins, a conductor, it's being played by a philharmonic! That's a classical musicy word!

The short answer of why we in the real, nonfictional world won't be calling Britney Spears's "Toxic" classical music in 100 years is it simply doesn't sound like classical music.

.....and the long answer is that Mahler's Symphony No. 5 isn't actually classical either.

See, music, just like everything in culture from dress to art to architecture changed with the times, and therefore 'classical music' is technically (although not colloquially) only one of about four to five musical periods/styles you're likely to hear on one of those "classical music tunes to study to" playlists.

Our dear friend Mahler up there was not a classical composer, he was a composer of the late romantic era.

So now, because I have you hostage in my post (just kidding please don't scroll away I had a lot of fun writing this but it took me nearly 3 hours) I'm going to show you the difference between Classical music and the other musical eras.

These are the movements we'll be dealing with, along with the general dates that define them (remembering of course that history is complicated and the Baroque Period didn't magically begin on January 1st, 1600, or end the moment Bach died) :

The Baroque Period (1600-1750)

The Classical Period (1750-1820)

The Romantic Period (1820-1910)

The Impressionist Movement (1890-1920)

You'll notice that as time goes on, the periods themselves grow shorter, and there starts to become some overlap in the late 19th to early 20th century. The world was moving faster, changing faster, and music and art began changing faster as well. Around the beginning of the 20th century music historians quit assigning One Major style to an entire era of history and just started studying those movements themselves, especially since around the 20th century we were getting much more experimentation and unique ideas being explored in the mainstream.

Even the end of the classical to the beginning of the romantic period can get kind of fuzzy, with Beethoven, arguably one of the most famous classical (and yes he was actually classical) composers in history toeing the line between classical and romantic in his later years. The final movement of his 9th symphony, known as Ode to Joy, far more resembles a romantic work than a classical one.

But, I'm getting ahead of myself.

To oversimplify somewhat, here are the main characteristics of said movements:

The Baroque Period (1600-1750)

Music was very technical and heavily ornamented. This coincided with a very "fancy" style of dress and decoration (the rococo style became popular towards the latter half of this period). The orchestras were far smaller than we are used to seeing in concert halls today, and many instruments we consider essential would not have been present, such as the french horn, a substantial percussion section, or even the piano*. Notable composers include Vivaldi (of the Four Seasons fame), Handel (of the Messiah fame) and Bach:

youtube

*the piano as we know it today, initially called the pianoforte due to its ability to play both softly (piano) and loudly (forte) in contrast to the harpsichord, which could only play at one dynamic level, was actually invented around 1700, but didn't initially gain popularity until much later. This Bach Concerto would have traditionally been played on a harpsichord rather than a piano, but the piano really does have such a far greater expressive ability that unless a group is going for Historical Accuracy, you'll usually see a piano used in performances of baroque work today.

The Classical Period (1750-1820)

In the classical period, music became more "ordered," not just metaphorically but literally. The music was carefully structured, phrases balanced evenly in a sort of call and response manner. Think of twinkle twinkle little star's extremely balanced phrasing, itself a tune that Mozart took and applied 12 classical variations to, cementing it in popularity.

And speaking of twinkle twinkle, memorable melody became more important to the composition than ornamentation, and many of our most universally known melodies in the west come from this period. The orchestra also grew bigger, adding more players of all kinds as now we didn't have to worry about overpowering the single-volume harpsichord, and additional instruments like more brass and woodwinds were added. Notable composers include Haydn (of The Surprise Symphony fame) Beethoven (of, well, Fame), and Mozart:

youtube

Pay attention to the size of the orchestra here, then go back to the Bach concerto. Notice how in that very typical Baroque setting, the orchestra sits at maybe 20 people, and that here in a Classical setting, there's nearly two times that!

The Romantic Period (1820-1910)

In the romantic period, it was all about BIG FEELINGS, MAN. It was about the DRAMA. Orchestras got even bigger than before, the music focused less on balance and became more dramatic, and there was a big focus on emotions, individualism, and nationalism. Discerning listeners will notice a lot of similarities between romantic symphonies and modern film scores; John Williams in particular is very clearly influenced by this era, any time I'd play the famous Ride of the Valkyries by Wagner in a class, the kids would remark that it sounds like it should be in Star Wars.

A lot of romantic composers were German, including Beethoven, if you want to call his later works romantic (which I and many others argue you can, again, compare Ode to Joy to one of his earlier works and you can hear and see the difference), but you also have the Hungarian Liszt (of the Hungarian Rhapsodies fame), the Russian Tchaikovsky (of the Nutcracker and 1812 Overture fame), and the Czech Dvořák:

youtube

See how this orchestra is even bigger still? Modern orchestras tend to vary in size depending on what pieces they are playing, but the standard is much closer to this large, romantic size, and it's far less typical to see a small, intimate Baroque setting unless specifically attending a Baroque focused concert.

Also I know I embedded Dvořák because Symphony From a New World slaps but please also listen to Liszt's Hungarian Rhapsody No.2 it's one of my all time favorite pieces and NOT just because of the Tom and Jerry cartoon, alright? Alright.

The Impressionist Movement (1890-1920)

A bit after it began but definitely still during the romantic period, a counter movement began in France that turned away from the emotional excess of romanticism and focused less on standard chord progression and explored more unconventional scales. This music was less worried about how it 'should' sound and was more concerned with evoking a certain emotion or image, giving you an "impression" of an idea. Debussy is by far the most well known name in this movement, even though he personally hated the term 'impressionism,' lol.

youtube

Notice the way the periods build on each other naturally, literally, physically builds on the orchestras that came before, evolving in style and structure until you get to the late 19th and early 20th century when things were built up so big that a response to that excess started to develop, first in the impressionist movement, and then into 20th century music in general, which got much more experimental and, as we say, "weird." (frickin 12 tone scales, man)*

*i do not actually dislike the sound of 12 tone, it's interesting and unique, but it is HELL to analyze in music theory, which is unfortunately when a lot of us classical musicians are first introduced to it, therefore tarnishing our relationship to the genre as we cannot separate it from our own undergrad anguish

Even if you're not a super active listener and you have a harder time discerning the difference between, say, late baroque and early classical, you cannot deny that the first piece I've linked by Bach and the last piece I've linked by Debussy sound completely different. They're both orchestral pieces (I intentionally chose all orchestral pieces as my examples here, getting into solo works, opera, and chamber ensembles would take too long), but other than that, they couldn't be more different.

Wait, so what are we talking about again?

Classical Music is first a period of music, a specific artistic movement with music typically written in Europe between 1750 and 1820 with a specific sound that is distinct from these other styles I've outlined here.

And Classical Music is second a genre. Because while academically and historically Baroque music is not classical, and Romantic music is not classical...colloquially it is. They sound similar enough that it makes sense to put them on the same playlists, the same radio stations, the same 'beats to study to' youtube compilation videos. While individuals may have favorites and preferences, it's not far fetched to say that if you like listening to one of these styles, you'll at least like one of the others.

But whether you're being broad and referring to our modern idea of the classical genre, or you're being pedantic like me and referring to a specific period of musical history (or modern compositions emulating that style, because yeah, modern compositions of all of theses styles do exist), I think we can all agree that, as much as it slaps, "Toxic" by Britney Spears is not classical music, and 500 years is unlikely to change our perspective of that.

A Traditional Ballad though?

Yeah, I can see us calling it that in 5 billion years.

youtube

(the full version of this scene is age restricted for some reason, but you can watch it here)

Anyway, thanks for reading y'all, have a good one!

#music#music theory#music history#classical music#baroque music#romantic music#impressionist music#music teacher#music teaching#taylor teaches#asks and answers#long post

181 notes

·

View notes

Photo

National Film Score Day

As the opening scenes of a long-anticipated movie begin to flicker across the screen, a rising cadence undulates through the theater setting the mood. A musical note plays, then two, and soon the theater is filled with a beautifully layered orchestral music masterwork. This musical accompaniment to the film you’re watching is called the “Film Score.”

On April 3, National Film Score Day recognizes the musical masterpieces called “Film Scores” and, more specifically, the very talented composers who create them.

Imagine your favorite film without a few well-placed notes enhancing the emotion of a dramatic on-screen exchange or some rousing orchestral music elevating the intensity of a thrilling chase scene. Would Star Wars, Jaws, The Lord of the Rings films, or the Harry Potter films be the same without their complementary musical scores? Without the film score, would we be compelled to cower in fear in our seats, or imagine a fascinating newly discovered world? Music heightens emotions, sharpens our senses and focuses our attention. Without a doubt, the film score indeed is the fiery soul of a film.

Throughout film history, from the perennial classics to the modern day blockbusters, we easily recognize our favorite movies merely by a few notes of a film’s orchestral soundtrack. Those chords often ignite a rush of fond memories and, with each new film released, a talented composer creates another magnificent work of musical art that elicits a new set of lasting movie memories.

HOW TO OBSERVE

Decades of accomplished composers from Miklós Rózsa, Shirley Walker, Bernard Herrmann, and Leonard Bernstein to John Williams, Jerry Goldsmith, Rachel Portman, and Michael Giacchino – hundreds more too numerous to name – have created lifetimes of masterworks. Share with us your most memorable film score moments.

HISTORY

Jeffrey D. Kern from Movie Scores and More Radio founded National Film Score Day to celebrate and highlight the tireless achievements of the talented composers and their treasured musical masterworks that bring so much joy to moviegoers around the globe!

Why April 3rd?

On April 3, 1942, Alexander Korda’s film The Jungle Book was released with an orchestral score by the legendary composer, Miklós Rózsa. The following year, a recording made directly from the soundtrack was published in its entirety on 78-RPM record album with narration by Sabu, the film’s star. The Jungle Book soundtrack became the first commercial recording of a non-musical U.S. film’s orchestral score to ever be released. The album was a success.

In honor of the first-ever score to be released, we celebrate National Film Score Day on April 3 — the day The Jungle Book originally premiered in 1942!

Source

#National Film Score Day#Howard Shore#Canadian composer#KKL#Luzern#Lucerne#21st Century Symphony Orchestra#21st Century Orchestra#Ludwig Wicki#Lucerne Culture and Congress Centre#Kultur- und Kongresszentrum Luzern#Europaplatz 1#Jean Nouvel#original photography#interview#tourist attraction#music#icon#3 April#3 April 1942#NationalFilmScoreDay#signing autographs

0 notes

Text

Caramelldansen, the Disney Channel theme, & obfuscated authorship

Kevin Perjurer's Disney Channel's Theme: A History Mystery and jan Misali's who wrote Caramelldansen? feel like complimentary opposites.

Both are videos about the authorship of music that lots of people have heard but few people think about. But the similarities end there. (Aside from some fairly petty stuff like "both have iconic associated choreography, if the wand thing counts as choreography".)

Perjurer expresses frustration that, for all the artistry he puts into this and his other documentaries, he will be remembered as a YouTuber or a content creator, not a documentarian or a filmmaker. For all the work jan Misali puts into his craft, he embraces the fact that he makes YouTube videos. It's not easy to remix "Die Young" and "Hare Hare Yukai," but Misali did it...and what kind of documentary would have a 13-second title card in the middle with a mashup of a J-pop song and an A-pop song playing over it?

(Are American pop songs called A-pop? They should be.)

On a related note: Perjurer's documentary seems to have that tension as its primary theme. The tension between the effort and artistry that goes into something like the Disney Channel theme, and the disrespect it receives for not even qualifying as "low art". The primary theme of Misali's video seems to be more along the line of "It's worth remembering random facts about the world," expressed through his frustration at Remix Records, his frustration at how much Caramelldansen ("I would absolutely love to play the garbage Caramelldansen rhythm game!"), and the random facts he dug up while researching and chose to share for no other reason.

(There's a decent argument that who wrote Caramelldansen?'s primary theme is more along the lines of "'Caramelldansen''s original authorship is irrelevant, because the meme is what makes it 'Caramelldansen'," but that theme doesn't really appear outside the video's conclusion.)

Another stream-of-thought association: Perjurer has nothing but respect for the work of Alex Lasarenko, both his contributions to the Disney Channel theme and his broader work. Misali has nothing but shade to throw on the work of Giovanni Sconfienza, both his "contributions" to Caramelldansen and his broader work, and especially his attempts to take the Caramell out of Caramelldansen. I feel both of these are 100% justified, given context, but it's another interesting contrast!

Perjurer assumes that the audience will accept that the Disney Channel theme's importance is obvious to the viewer, and understand what made it so prominent. It was played on one of the biggest kid's TV networks of the 21st century! Misali focuses most of the video on why and how Caramelldansen rose to prominence, because for a lot of people it's just "that song that plays for ANIME LOL".

The obfuscation of the Disney Channel theme's authorship comes down to Disney being Disney and not saying anything about non-Disney people who make Disney Disney. (And, to be fair, broader industry trends.) The obfuscation of "Caramelldansen"'s authorship comes down to some rebranding done years after the fact.

Misali is (I feel, rightfully) critical of [name]. Perjurer is (I feel, rightfully) respectful towards Alex Lasarenko and the music he directed/composed.

Most obviously: It takes months of research, correspondence, interviews, and so forth before Perjurer can figure out who wrote the Disney Channel Theme. Misali identifies Caramell as the creators of "Caramelldansen" in the opening seconds of the video. (Also, it's in the song's title.)

Now, you might reasonably wonder why I wrote this post, comparing two random YouTube video essays on similar topics. I'd like to provide some grand thesis statement that ties my conclusions and process into some statement about the nature of art. However, at the end of the day, this is more of a jan Misali post than a Kevin Perjurer one. But I think both would agree that this kind of little thing has merit. (Nowhere near enough to ask for their opinion or assume they'd have one, of course.)

#jan misali#defunctland#youtube#caramelldansen#disney channel theme#random thoughts#unusually random this time#video essays

928 notes

·

View notes